After a brief interlude, in which you analyzed a Michelin-starred restaurant fighting for relevance during that awkward period of “middle age,” you now take aim at another concept that has comfortably reached maturity. Yes, after North Pond (opened in 1998) and Boka (opened in 2003), Sepia (opened in 2007) shines as another member of the old guard: one of those perennial Bibendum favorites (only four other restaurants have held stars in every single edition of the Chicago Guide) that forms the venue for many a consumer’s first tango with fine dining.

These old stalwarts are certainly worthy of respect, for you do not reach 15, 20, or 25 years of serving inventive (read: expensive) cuisine in this city without doing something right. And, in the case of Boka (with the wider BRG empire) and Sepia (with Proxi), success has even fueled expansion.

Of course, you know by now that the overarching financial health of a restaurant group does not necessarily ensure the lasting quality of its mothership. Ideally, other openings would help preserve and empower the creative processes that have built the brand’s reputation. However, just as easily, new properties sap the group’s resources and attention. Thus, the crown jewel adopts a defensive posture and becomes frozen in time. It plays it safe and plays the hits—over and over—to make the most of the popularity it has cultivated.

Sure, there is nothing wrong with giving the public what they want. But what of the wasted potential—the opportunity to continue pushing and growing your patrons’ appreciation of gastronomy? Why not, by wholeheartedly pursuing some singular vision and enriching the dining scene in your wake, affirm that Chicagoans deserve the best, most forward-thinking concepts in the country rather than what simply sells well today?

North Pond, you think has succeeded by staying true to an identity that was barely legible (let alone popular) when the restaurant launched. It has arguably even doubled down on that vision by bringing in a new chef who combines the same values with a quiver full of cutting-edge techniques. Boka, by your measure, has gone the opposite route: simplifying and streamlining its cuisine while ratcheting up the pricing on beverages. As BRG focuses on projects in other markets, its mothership acts merely as a promotional tool (allowing the company to invoke its “Michelin-starred” credentials) and a cash cow. It seems content to milk its existing audience for as long as possible while offering nothing to snare a new generation of diners.

Where does Sepia fall within this dichotomy? Well, having been nominated alongside four other restaurants for “Outstanding Hospitality” at the 2023 James Beard Awards (ultimately losing out to The Quarry in Monson, Maine), the concept would appear to be performing at its peak. That being said, the JBF—in the wake of some serious soul-searching (or was it capitulation?)—cannot be relied upon as a neutral arbiter of quality. And even Bibendum, to be fair, is not really inclined to ever take away stars unless something catastrophic happens.

Yes, having earned its status as an institution, Sepia is entitled to coast on that reputation. The restaurant has its longstanding fans—very much like Boka does—who regularly return to invoke the warm memories they have made for over a decade. And, no doubt, there must be a trickle of newcomers who, attracted by the value proposition, decide to take the plunge.

“What drives them?” you wonder, for Sepia does not routinely command the attention of the local food media or “foodie” influencer complex. It falls, like Boka, North Pond, and Temporis, within that impenetrable “contemporary American” genre and lacks the easy differentiation that being the namesake of a larger restaurant group, boasting an incomparable natural setting, or wielding Grace-inspired molecular techniques respectively provide. By offering “seasonal menus…rooted in tradition, melding rustic sensibility with contemporary flair,” the restaurant even seems to be proudly retrograde.

Today, Sepia stands as an ode to the past in a neighborhood that is now defined by burgeoning growth. Of course, Randolph Restaurant Row had already taken shape long before the place opened: with the street’s transformation into a hospitality destination being dated to the opening of Jerry Kleiner’s Vivo in 1991. Even Blackbird, once located less than a block away, took flight in 1997—a full decade before Sepia came into existence.

Blackbird’s closure in 2020 was a bitter pill to swallow: it being another one of those restaurants that had earned one or more Michelin stars in every edition of the Chicago Guide. The concept’s cuisine, under Ryan Pfeiffer, was decidedly modern but still playful with bold bursts of eclectic influence. It was, air quotes aside, contemporary American cooking of a national caliber. How did it bode for Sepia that its equally awarded neighbor—crafting more experimental dishes imbued with greater viral appeal—could not survive? The pandemic, no doubt, had a part to play. Blackbird’s sleek interior design was rather cramped while Sepia benefitted both from a larger space and a private events business. Yet, are changing tastes also to blame?

With each successive high-rise, Randolph Restaurant Row fulfills its promise as a dense, indefatigable entertainment district. However, Bellemore, too, was forced to close across the street from Sepia, with BRG substituting its “bold, bright, and beautiful” American cuisine for Alla Vita’s thoughtless menu of pizza and pasta. The latter concept joins Bar Siena, Fioretta, Formento’s, Gino & Marty’s, Gioia, Macello, Monteverde, Riccardo Osteria, and Rose Mary as one of many options within this broader genre that you can find in the surrounding area. Even Next, with its Tuscany menu, has gotten in on the act: their latest theme ranking among the weakest ever (and further cementing a precipitous decline that started, in truth, the second Dave Beran left).

Elsewhere, across West Loop, you find Japanese (Gaijin, Mako, Momotaro, Nobu, Omakase Yume), Mediterranean (Aba, avec, Cira), Mexican (La Josie, Leña Brava, Texan Taco Bar) and steakhouse (BLVD, El Che, Swift & Sons) concepts all well represented along with the odd Chinese, Indian, Peruvian, and Spanish joint.

American fare features at a litany of places: Au Cheval, Bandit, Beatrix, Eleven | Eleven, Fulton Market Kitchen, Girl & the Goat, The Oakville, The Publican, Trivoli Tavern, and Wishbone among others. Nonetheless, while some of these properties are a bit contemporary in their approach (reflecting a global influence) or embody particular inflections (Californian, Cajun), none really aspire to fine dining. Rather, they are broadly come-as-you-are places equipped to sate Randolph’s meandering consumers with shared small plates, burgers, fried chicken, and the occasional steak washed down with cocktails and beer. This is a bit of an oversimplification—and, to be clear, you enjoy a couple of these establishments—but they speak to a casual, unfussy approach to the country’s foodways compared to what Blackbird or even Bellemore were doing.

Now, to be fair, Randolph Restaurant Row and its surrounding avenues are home to a few “contemporary American” heavy hitters: Ever, Oriole, and Smyth. However, these concepts are more defined by particular techniques (molecular gastronomy, fermentation) and aesthetic properties (the cavernous Lawton Stanley design, the album covers spanning the ceiling of the kitchen) than any decidedly domestic bent. Instead, they combine ingredients from near and far with a wide range of influences (France and Japan often being represented) in a manner that speaks to their star chef’s personality. Ultimately, these establishments are singular “uber brands” that have built a kind of prestige that separates them from the rest of the market. Ever, Oriole, and Smyth are not thought of as three options among countless “contemporary American” restaurants but as pinnacle experiences that can only, at best, be compared to each other (and one or two other places in town).

Sepia might be best judged relative to Elske, Roister, and Valhalla: Michelin-starred, formerly Michelin-starred, and likely soon-to-be Michelin-starred concepts respectively that roughly fit the “contemporary American” mold. Elske, of course, shows a distinguishing Danish influence that just about places the restaurant in its own category. Roister, likewise, is known as the more casual, approachable wood-fired counterpart to the infamous Alinea and Next (even though it has begun offering a $115 tasting menu of its own). Only Valhalla, perhaps, remains a bit undefined in the mind of the consumer. Yet, its food hall location and $188 price tag are certainly enough to make an impression upon being discovered.

Yes, looking at the neighborhood that has developed around it over the course of 16 years, Sepia now almost seems defined by its plainness. Now serving a $95 four-course menu, the concept may even seem paltry in an era when meals are being offered for quintuple that price. For, a new generation of Americans—entering the world of fine dining for the first time—is naturally attracted to what they perceive to be “the best.” Michelin stars signify luxury after all, and, should you be unable or unwilling to secure a rarefied table, then a sense of novelty would be the next best thing.

Why pay $95, the sort of sum that buys a nice time at a steakhouse, for American food “rooted in tradition, melding rustic sensibility with contemporary flair”? Why not pay $115 for Roister’s relation to the hallowed Alinea, $125 for Elske’s Danish delights, or $188 to sit in Valhalla’s “dynamic, high energy location”? Why not pay for a whole range of other Michelin-starred experiences in the Filipino, Mexican, Middle Eastern, or omakase genres?

Sepia—on the surface—only seems to shine as the safe choice for backwards palates, the value play for those who want a tiny taste of what exactly the Guide and its ratings are all about. “Outstanding Hospitality” aside, just what does the restaurant, in this era of increasing premiumization and self-definition, offer the discerning consumer? How high can “contemporary American” cuisine free of any obvious embellishment really fly?

These questions will inform your analysis of this next, great member of Chicago’s old guard. Yet, before digging in, it may be instructive to get a sense of how the concept has made its way to maturity.

The story of Sepia undoubtedly starts with Emmanuel Nony, who grew up “in Le Touquet, in the northern part of France near Boulogne and Calais” spending “a lot of time at the local farmers market” and “fishing tiny shrimps with…[his] brothers and sisters.” His parents “were true bon vivants” who inspired a “love of good food and entertaining” in their son, and he naturally found his way to culinary school upon coming of age.

Nony, nonetheless, discovered he was destined to work in the front of house and transitioned “to the service side from the kitchen” for the rest of his career. In the 1980s, he moved to Orlando and took his first major job at EPCOT’s France Pavilion. There, Disney had opened Les Chefs de France—a “family-friendly brasserie” serving nouvelle cuisine—in collaboration with Paul Bocuse, Gaston Lenôtre, and Roger Vergé. Nony spent “several years moving up the ranks” at the restaurant under Mickey’s watchful eye before taking a position with Hyatt International.

Across 16 years working for the group, he managed food and beverage operations for hotels in New York, Hong Kong, Seoul, and Fukuoka. Nony also, notably, managed the program at the Park Hyatt Tokyo (of Lost in Translation fame). In 2000, he moved to Chicago to open the “newly rebuilt” Park Hyatt at 800 N Michigan Avenue. There, Nony would help NoMI, the hotel’s 120-seat restaurant on the seventh floor, earn three stars from the Chicago Tribune with a “straightforward, approachable” French-International menu from JBF “Rising Star Chef of the Year” nominee Sandro Gamba.

In June of 2005, Nony’s peripatetic journey with Hyatt would come to an end. He had “fallen in love with the Windy City” and “decided to put down roots here” by opening his own restaurant. About a year later, the former NoMI man had signed a lease for an old “1890 print shop in the West Loop” and installed himself in an apartment “just down the street.” In February of 2007, the new “contemporary American” restaurant revealed its name: Sepia. In July of that same year, the 90-seat concept would open promising a “contemporary-yet-traditional American dining experience likely to appeal to West Loop hipsters.”

Nony had tapped Kendal Duque, Gamba’s sous chef at NoMI, to lead the kitchen, whose cuisine was alternatively described as “part Chicago” and “[part] Italian.” However, much of Duque’s prior experience was—like his boss—decidedly French.

Born in Quito, Ecuador, the chef earned “a biochemistry degree from UPenn and a literature MFA from UC Berkeley” before planning to pursue a PhD at Harvard. Nonetheless, Duque had grown up in “a family with a strong food culture” (his grandmother being “considered one of the city’s best cooks”), and he found himself sucked into “Berkeley cooking culture.” That led to Peter Kump’s Cooking School (now known as ICE) in New York and two years working for Spanish chef Julian Serrano at Masa’s (in San Francisco) and Picasso (in Las Vegas).

In 1998, Duque moved to Chicago and worked for Jean Joho at Everest, where he wanted to get his “butt kicked” by the “tough” and “very old-style French” chef. A year later, the former biochemist would open Tru as sous chef under co-owners Rick Tramonto and Gale Gand. Leaving Chicago, Duque “spent a summer staging at Michelin-starred restaurants in Paris” before returning to New York. There, he worked for Rocco DiSpirito at Union Pacific—a “fine-dining temple” that earned three stars from The New York Times. Returning to Chicago, Duque took the job at NoMI and, subsequently, spent time as chef de cuisine of the Union League Club before reuniting with Nony for Sepia.

At the time of the concept’s opening, Duque sounded “happy to be breaking free of his French fine-dining background,” one he noted “really takes you to the extreme and rips you apart to your core.” His menu, in contrast, would feature “trendy/cozy creations” of “no more than four components” like “grilled quail with mustard greens” and “warm pig trotters vinaigrette” alongside “comfort food” desserts from pastry chef Kim Schwenke (who came to Chicago by way of North Carolina). Elsewhere, the style of the food would be described as speaking “mostly of the ingredients, but with a chef’s touch, a restaurateur’s hand.”

While it is hard to find examples of the “opening hype” that surrounded Sepia, early reviews seem convinced by Duque and Nony’s work. The Chicago Reader, writing in August of 2007 (after about a month of operation), praised the “visually interesting” renovation of the 1890 print shop “in shades of black and sepia with sage and burgundy accents.” The servers, likewise, seemed “savvy” and “happy to be there.” Fare like “moist rabbit paired with delicate ricotta dumplings in a Riesling reduction,” “ultratender charred octopus piled on a toasted baguette slice in tomato sauce,” “slow-baked veal breast on wide, lightly minted noodles,” and a “thick Berkshire pork chop complemented by crunchy pickled wild onions” drew praise. Flatbreads, “which head the menu,” and a “dry flourless chocolate cake” were disappointments, but an “eclectic, affordable wine list” helped make for “an enjoyable experience” overall.

Phil Vettel, writing for the Chicago Tribune in September of 2007, would award Sepia three stars (“excellent”) and proclaim that the restaurant “lives up to the hype with creative, oftentimes stunning contemporary cooking” and “attentive, professional service that borders on the nurturing.” By that point, the concept was already “hot”—not “lines-out-the-door hot or two-hours-at-the-bar hot,” but “you’d better call at least two weeks ahead for a weekend reservation.” The crowd, likewise, was a mix of “older, well-dressed…fans from Nony’s Park Hyatt days and Duque’s work at Union League Club” blended with “younger, often scandalously dressed” diners “enroute to Carnivale, Fulton Lounge or Ghost Bar.”

The critic was particularly enthralled by “a super-tall, model-thin woman” in “4-inch heels and vivid-yellow, Spandex micro-mini dress” one evening: “I give her credit for matching the restaurant’s color scheme; actually, I give her credit for a great many things, but this is a family newspaper.” However, he still found time to praise “eye-opening” flatbreads topped with combinations like “peaches, blue cheese and bacon” or “corn niblets and white anchovy.” The preparations of rabbit, octopus, and veal breast were all celebrated once more. So, too, were “lamb sirloin…placed over a ragout of Great Northern beans, roasted garlic and other bits of lamb [offal],” “skate wing…with a raisin-caper sauce,” “juicy free-range chicken…with pea shoots and surprisingly tasty wax beans,” and “duck breast…[with] sweet corn and swiss chard.” Only a “nearly spartan steak tartare” drew mild grumbles in a review that declared the “small, intimate and food-focused Sepia” lived up to standard set by its neighbors “Blackbird, Avec and Meiji—the culinary cognoscenti of the Randolph Street restaurant corridor.”

Laura Bianchi, writing for Crain’s Chicago Business in November of 2007, would take a slightly more negative tack. She praised Sepia’s “refined, friendly hospitality,” “rustic and elegant” décor, and “seasonal menus…prepared with organic, local or sustainable ingredients” but found “the food is still a work in progress.” In particular, the pork rillettes lacked flavor, the “duck-fat potatoes served alongside [the steak tartare] were pale and tasted ordinary,” and “trendy braised short ribs” were “too basic.” A “chocolate pear tart,” likewise, was “rubbery and harsh tasting” while “chocolate crêpes…were dry.” Still, the review praised dishes like “chilled tomato soup…with avocado and blue crab,” the rabbit, the octopus, a “grilled elk chop…[with] deeply browned potato and carrot cubes,” and a “flawless” apple dumping filled with “tender fruit, raisins and walnuts beside cinnamon ice cream and caramel sauce.” If anything, the chef just took “simplicity too far in a couple of cases.”

Still, this minor criticism aside, Sepia could claim a rather successful opening. The restaurant “paid out its first dividend to the investors within the first year” despite the 2007-2008 financial crisis, and Duque himself collected a couple awards: being recognized as Chicago magazine’s 2008 “Best New Chef” and named a semifinalist for the James Beard Foundation’s “Best Chef: Great Lakes” title that same year. Sepia, likewise, would be named a “Best New Restaurant” in 2008 by both Chicago and Time Out while Robert Louey Design would win the JBF’s 2008 “Outstanding Restaurant Graphics” award with its work for the concept.

Some representative dishes from this era, available thanks to internet archiving, are as follows:

- “Jonah Crab, Potato and Almond Pesto Flat Bread”

- “Lamb Shoulder, Caramelized Onion and Olive Flat Bread”

- “Sweet Corn Gazpacho with Bell Pepper Cream and Cornbread Crouton”

- “Watermelon and Shaved Fennel Salad with Goat Milk Yogurt Dressing”

- “Sea Scallops with Pork Belly, Knob Onions and Sugar Snap Peas”

- “Red Kuri Squash with Ham, Arugula, Walnuts and Parmigiano Reggiano”

- “Veal Sweetbreads with Celery Root Remoulade and Black Truffle Vinaigrette”

- “Whole Wheat Pasta with Smoked Duck Breast in Carbonara Style”

- “Amish Chicken with Acorn Squash and Serrano Ham”

- “Porcelet Rib Chop and Leg with Lentils and Brussels Sprouts”

- “Walleye Pike with Black Trumpets, Salsify and Cashew Vinaigrette”

- “Cod with Spaghetti Squash, Wild Board Sausage and Paprika Sauce”

- “Braised Veal Short Ribs with Mint Noodles and Truffle Butter”

- “Sweet Potato Spice Cake Bread Pudding and Caramel Thyme Ice Cream”

- “Malted Milk Chocolate Mousse on Peanut Butter Crunch with Maple Peanut Sauce and Pretzel Bark”

- “Pistachio Ice Cream and Pistachio Financier with Dark Chocolate Sauce”

These were complemented by nearly a dozen cocktails (like the “Strawberry Old Fashioned,” “Sepia Mule,” and “Honeycomb Margarita”) from head bartender Josh Pearson alongside a range of wines (identified by “the predominant grape in each bottle, a thoughtful touch for those less-familiar with European” bottles) from sommelier (and future Master Sommelier) Scott Tyree.

2008 would also see opening pastry chef Kim Schwenke depart. She was replaced by Cindy Schuman, who had spent more than six years at “Kevin Shikami’s inventive, Asian-inflected restaurant” Kevin in River North making desserts like “chamomile rice pudding” and “milk chocolate mousse.”

2009, nonetheless, would bring with it an even more dramatic change. After 18 months leading the kitchen, Duque himself would leave Sepia. No further reasoning was given at the time—though, suggesting an amicable split, the chef put on an elaborate “Last Dinner” at the restaurant for his final service toward the end of March. Duque would eventually open The Chicago Firehouse in 2010 and City Tavern in 2012 (both with Mainstay Hospitality) before moving to American Junkie in 2013, Brass Monkey in 2014, and ultimately finding his way to Austin, where he is still opening concepts to this day, in 2018.

Back at Sepia, Nony recruited Andrew Zimmerman—then the chef de cuisine of NoMI—to lead his kitchen. Surely, his shared Park Hyatt experience was an important selling point (Zimmerman, like Duque, had worked under Sandro Gamba). However, he hardly represented a trite like-for-like replacement.

Growing up in Buffalo during the 1980s, Zimmerman harbored a “life-long dream” to become a rock star. An English major in college (having dropped his original choice of music), he nonetheless became a professional guitarist in his twenties—“I could play at a club and beg my friends to come”—while supporting himself “by working in restaurants in New York City.” (“I really worked in kitchens so I could make enough money to buy guitar strings or get a new amp.”) Though he once played for 10,000 people at the 1989 World College Pop Festival in Japan, Zimmerman “was ultimately more successful in cooking than making music” and, moreover, realized “that the kitchen was his true calling.”

As a kid, he was already described as “a precocious budding gourmand with a hankering for peculiar ingredients” who grilled his parents about their “business dinners at classic Manhattan gastronomic palaces.” As a teen, “sick of eating bland food” geared toward the taste of a younger brother “who was an extraordinarily difficult eater,” he cooked his first dish: shrimp étouffée adapted from the crawfish étouffée recipe in Chef Paul Prudhomme’s Louisiana Kitchen.

Thus, the rocker left the “fried fish and mediocre prime rib joints” he was working at behind and dedicated himself fully to the craft of cuisine. That entailed working “as sous chef for three years under Renato Sommella,” whom he cites as “one of his strongest culinary mentors” and the one that taught him to “trust…[his] instincts.” At 2Cenza in Red Bank, New Jersey (a restaurant “with room for only two cooks behind the hot line”), Zimmerman “got to stand next to this guy from Italy who was cooking his food, the food that he grew up with, that he really cared a lot about, and it was as good as being at the source in Italy.” There, Sommella guided him “through classic preparation of risottos, pastas” and “less classic non-Italian food items like foie gras and brioche.”

Leaving 2Senza, Zimmerman enrolled at The French Culinary Institute in New York City and graduated first in his class in 2000. From there, he took “a not particularly clever sous chef job” for a couple years opening a restaurant in his hometown. (“It probably would have been better if I had taken a line cook job for somebody super-serious and toughed it out a couple more years.”) Being drawn to Chicago’s “abundance of world-class restaurants” (as well as the fact that it is “his wife Lindsey’s hometown”), he accepted a position in the banquet department at the Park Hyatt in 2003. Somewhere along the way, he also staged for Patrick O’Connell at The Inn at Little Washington and for Grant Achatz at Trio.

By 2004, Zimmerman met Terry Alexander (of One Off Hospitality) and was invited to take over from Susannah Walker as chef of MOD. There, he served “creative contemporary American cuisine” in a “colorful and fun” setting. When Alexander reconcepted MOD into modern tapas restaurant Del Toro in December of 2005, Zimmerman was retained as chef. The latter went on “a four-day eating tour in Barcelona, dining out four or five times a day” in preparation so that he’d “have some taste memory of what I was shooting for.” And, in March of 2006, the Chicago Tribune would award Del Toro two stars (“very good”) in a review that “enjoyed just about every dish” but only grumbled that many “are perilously close to being oversalted.”

Del Toro would close in March of 2007, with the same critic declaring its “consistently interesting menu and arresting décor…will be missed.” The restaurant, for what it’s worth, remained “packed” to the very end. The closing “wasn’t about fickle customers,” but rather “a problem with a past partner.” Alexander would praise Zimmerman’s “insatiable quest for knowledge–knowledge of the origin of the dish, history of a vegetable, background of a leading chef” as distinguishing him from “a large majority” of the other chefs he’d worked with. Still, as Del Toro made way for The Violet Hour, the latter would need to find something new.

Or, as it happens, something old. Zimmerman returned to the Park Hyatt and became chef de cuisine of NoMI under chef Christophe David. In 2008, he was first introduced to Nony and, a year later, found himself perfectly positioned to take Duque’s spot at Sepia in March of 2009.

Stepping into the new role, Zimmerman would note that “the basic sentiment” of the concept “is still the same.” Sepia would still be “an American restaurant that uses a lot of local farm ingredients” with “an inflection of the Mediterranean.” He would simply interpret that idea differently, with Duque’s approach being “a little more rustic” and his successor’s “a little more refined in technique and approach.”

Looking back a few years later, Zimmerman would term the food Sepia opened with as “a lot simpler,” in line with “being a very very casual neighborhood restaurant.” He also “felt like some of the standards for the restaurant didn’t quite meet the restaurant that…[he’d] read about.” The goal wasn’t to make the restaurant “stuffy, or aim for Michelin stars” but to develop food and service that was “as sharp as the place looks.” It would take “almost the first full year” for the chef to make “a significant enough change” and really assert his style of cuisine.

By May of 2009, some of Zimmerman’s additions to the restaurant’s menu could start to be noted (alongside new desserts from Schuman, who remained as pastry chef):

- “Chestnut Soup with Braised Oxtail”

- “Seared Sea Scallops with Cabbage, Gnocchi and Whole Grain Mustard Sauce”

- “Whole Wheat Pasta Carbonara, Pecans, Pumpkin and Guanciale”

- “Sturgeon with Lentils and Root Vegetables”

- “Free-Range Veal Chop with Watercress and Celery Root Remoulade”

- “Skate Wing with Briased Collard Greens and Grape-Pine Nut Sauce”

- “Braised Beef Short Ribs with Taro Root Puree, Carrots and Turnips”

- “Freeform Pecan Honey Phyllo Tart with Honey Orange Ice Cream and Brandied Orange”

- “Cornmeal Cookie with Sweet Goat Cheese Cream, Blueberry Compote and Coconut Sorbet”

- “Citrus Cake and Ginger Custard with Carrot Sorbet and Apricot Crème Anglaise”

- “Pan Brownie with Chai Ice Cream, Almond Toffee and Griottines with Chocolate Caramel Sauce”

And, in June of that same year, the Chicago Reader would render its verdict, declaring that “Sepia couldn’t have found a better replacement for Kendal Duque than Andrew Zimmerman.” More particularly, the publication praised an “appetizer of a gently poached and crisply fried duck egg, the essence of spring on a bed of sauteed asparagus, ramps, and morels,” a “charcuterie combo” of “rich country-style duck paté, fine-textured rabbit rillettes, and a house-made pistachio-studded mortadella,” and a “Gunthorp Farms pork porterhouse” with “bourbon, a salad of greens and cherries on top, and smooth cheese grits underneath.” Schuman’s desserts, likewise, were termed “first-rate.”

Phil Vettel, writing for the Chicago Tribune in December of 2009, would echo the same sentiments. Once more awarding Sepia three stars (“excellent”), the critic termed Zimmerman “an ideal replacement” for Duque whose “modern look is tempered by deep traditional roots and frequent homages to rusticity.” More specifically, he praised a “wonderful piece of walleye…served with pieces of guanciale and wilted Brussels sprouts,” a “sensational” pot-au-feu of “poached chicken breasts wrapped in forcemeat and Swiss chard in a shallow pool of rich broth,” and a “comfort-food classic” of short ribs “braised in Belgian ale…[and] placed alongside spaetzle flavored with spice-bread seasonings.” Schuman’s work was again complimented as “stellar” while the beverage program was termed “exciting” both for its “well-crafted cocktails” and “globe-trotting wine list.” Service also remained “effortlessly professional” (even if the managers ultimately “sussed out” the critic’s identity).

With Zimmerman firmly at the helm, 2010 would prove to be a banner year for Sepia. In February, two members of the restaurant’s team would take home honors at the Jean Banchet Awards: Schuman for “Best Celebrity Pastry Chef” and Tyree for “Best Sommelier.” That same month, Crain’s Chicago Business would name Sepia one of five “Best Restaurants for Business”—not the most prestigious title, but one that affirmed the concept’s enduring quality under the new chef. Likewise, in March, Michael Nagrant—writing for Newcity—would name Sepia one of “Chicago’s essential restaurants of 2010” while highlighting “Zimmerman’s charcuterie” and “one of the best cocktail programs in the city.”

In June, Arthur Hon, who had been at the restaurant since opening, took the mantle from Tyree and became Sepia’s wine director. Over the course of seven years (in this particular role), Hon’s work would secure five semifinalist spots for the JBF’s “Outstanding Wine Program” award and one nomination. Sepia would be named one of “America’s 100 Best Wine Restaurants” by Wine Enthusiast four times, and the wine director himself would be named “Best Sommelier” by the Jean Banchet Awards (in 2014), “Best New Sommelier” by Wine & Spirits (in 2015), and “Sommelier of the Year” by Food & Wine (in 2017).

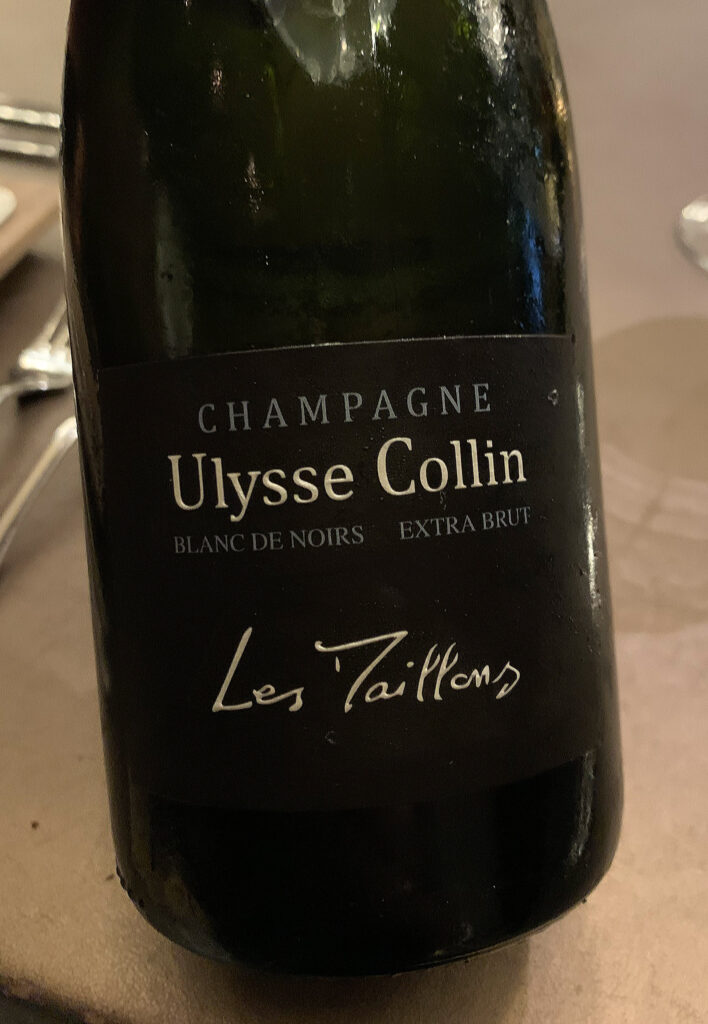

While a lack of archival sources makes it hard to fully appreciate Hon’s work, one surviving wine list from 2015 features producers like Bérèche, Cédric Bouchard, Dr. Bürklin-Wolf, Cavallotto, Chartogne-Taillet, Bruno Clair, Ulysse Collin, Corison, Dagueneau, Vincent Dancer, A. et P. de Villaine, Schlossgut Diel, Dönnhoff, Egly-Ouriet, Gravner, Guiberteau, Jamet, Weingut Keller, Krug, Labet (Jura), Domaine des Comtes Lafon, Maison Leroy, Matthiasson, Marguet, Méo-Camuzet, Château Palmer, Ponsot, Domaine de la Pousse d’Or, Joh. Jos. Prüm, Ökonomierat Rebholz, Ridge, Roagna, Salon, Willi Schaefer, Tempier, Terlan, Tissot, and Vietti.

In short, Hon presided over an embarrassment of riches that—especially considering the low markups—has only very rarely been equaled by other contemporary Chicago wine lists.

July of 2010 would mark the passage of Sepia’s third birthday, and it would also come with the announcement that Ron Howard “decided to film several scenes for an upcoming movie” at the restaurant “after eating there and falling in love with its vintage design and cuisine.”

It would also offer an opportunity to check in on the state of Zimmerman’s menu after more than a year leading the kitchen, with the following dishes being featured:

- “Watercress Soup, Frog’s Legs Beignet, Crème Fraiche”

- “Sea Scallops, Celery Root Purée, Tangerine, Herb Salad, Black Pudding”

- “Bone Marrow ‘Crème Caramel,’ Mushroom Jam, Brioche”

- “Confit Baby Octopus, Fresh Chickpea Hummus, Black Olive Honey”

- “Shooting Star Greens, Feta, Sunchoke, Pickled Ramp Vinaigrette”

- “English Pea and Marscapone [sic] Ravioli, Pea Shoots, Thyme Butter”

- “Confit Duck Leg, Spinach and White Beans, Duck Heart, Rhubarb Gastrique”

- “Arctic Char, Sauerkraut, Rye Gnocchi, Pickled Mustard Seed”

- “Stinging Nettle Dumplings, Mushroom-Black Garlic Puree, Bulgur Wheat”

- “Flat Iron Steak, Sunchoke, Maitake, Coffee, Béarnaise”

- “Halibut, Artichokes, Littleneck Clams, Ramp Green Cavatelli”

- “Bacon Wrapped Trout, Red Bliss Potato, Watercress, Rosemary Vinaigrette”

Later, in September, Crain’s Chicago Business would come out with a more detailed appraisal of Zimmerman’s work, declaring the chef is “hitting all his marks” and maintaining “Sepia’s sensibility of contemporary but rustic, seasonal American fare while bringing his own exacting preparation to almost every element on the plate.” Though the review, once more focusing on business lunching, found that “noise can still be an issue,” it found that “knowledgeable yet unfussy service” and “proud hospitality that practically radiates from owner Emmanuel Nony” carried the day.

In November, all the momentum of 2010 would culminate in the announcement that Sepia was one of 18 restaurants to earn a star in the inaugural Michelin Guide Chicago (and one of 23 to earn stars in total). In a full-page feature, Bibendum would term the concept’s vibe “raw, urban, and sexy in a very current, rustic-industrial sort of way.” The entry would go on to praise Zimmerman’s “wide use of local and seasonal products, spinning them into such simple, elegant fare” that “manages to appeal to all types: young, old, artsy, corporate, dates, and groups of friends.” More specifically, “delicious flatbreads,” “golden sea scallops served over soft pillows of gnocchi,” and “a juicy, perfectly grilled Berkshire pork chop wrapped in crispy bacon” were all highlighted.

Seven years later, Zimmerman would reveal that he was “on the way to the dentist” when he received the tire company’s call. The team “had some Champagne at the restaurant” but, ultimately, realized they “had to get right back to work to meet—and hopefully exceed—the new expectations that…guests would have.” Sepia took the star “as a challenge and an opportunity to raise the bar at the restaurant in some small ways,” like adding “a nightly tasting menu” and reassessing “the sequence of service and the service standards.” Nonetheless, the chef admitted they “haven’t pursued an additional star” because the changes necessary to achieve it “would change the fundamental character of the restaurant in a way that might alienate…[its] core following.” Instead, they “are happy to work at being a really great one star restaurant.”

To that end, Nony and Zimmerman would open Private Events by Sepia across the alley from their flagship in 2011: a “2,200 square-foot space” accommodating “50 to 70 people for sit-down dinners and upwards of 175 for cocktail receptions.” The concept would allow the team, who could not “handles parties larger than 20 in the dining room,” to better manage the “hundreds of requests for large groups” they had received since opening. Nony noted that they had “stepped up in general with the food and service and…business has been consistent and strong” in the aftermath of the Michelin star. So, “why start a second restaurant when you have so many people who want to come to Sepia and you can’t accommodate them?”

A ”brand new concept” was indeed “on the docket,” but Nony and Zimmerman were “in no hurry.” Instead, they also unveiled an “expanded 16-seat sidewalk patio” that year.

2012 would see Zimmerman named a finalist (alongside Michael Carlson, Stephanie Izard, Anne Kearney, and Bruce Sherman) for the “Best Chef: Great Lakes” honor at the James Beard Awards. (He would also, subsequently, be named a finalist in 2013, 2014, 2015, and 2016 though never winning.) Nonetheless, the chef would fare better on Iron Chef America in “Battle: Cream Cheese” against Marc Forgione. Zimmerman and sous chefs Adam Zosack and Sam Henderson bested their competition by two points with a menu that included “cream cheese lobster rangoon served…with handmade sauce packets” and “salt cod brandade-filled pierogies topped with Australian winter black truffles.”

2013 would kick off with Zimmerman losing out on the “Chef of the Year” honor at the Jean Banchet Awards (also having been nominated in 2011 and 2012), but Sepia itself would secure the “Best Restaurant” title. In April, Josh Pearson (himself a Jean Banchet “Best Mixologist” winner in 2012) announced he would be leaving the concept, later being replaced that May by Griffin Elliott (of Boka and Scofflaw). July would also see Zimmerman and his team journey to Nony’s old stomping grounds—the Park Hyatt Tokyo—for a five-day residency at its New York Grill. There, the chef combined some of his classic preparations with fresh Japanese ingredients and a selection of Californian wines.

2014 started off with Crain’s Chicago Business once more celebrating Sepia’s good work, with Laura Bianchi (who offered the most critical of the concept’s opening reviews) terming the restaurant a “treasured spot” and “still a winner” after seven years. More particularly, she praised a “mortadella flatbread” (with house-made sausage, pesto, and Grana Padano), “chitarra pasta” (with pecorino cream sauce), “wagyu meatloaf” (with beef cheek pastrami, barbecue sauce, pickled carrots, and a housemade potato bun), and “buttermilk-and-cornmeal crusted trout” (with candied bacon and black-eyed peas).

2015 would see Time Out get in on the act, with Amy Cavanaugh awarding Sepia four out of five stars while praising “crisp-skinned trout,” “chicken with sausage bread pudding,” and “creamy foie gras capped with sour cherry gelee” alongside “well-balanced drinks” and a wine list that is “among the city’s best.”

This year would also yield one of the more amusing glimpses into Zimmerman’s personality via a “Ten Things I Hate” interview with Food Republic. In it, the chef would reveal he “hate[s] oysters,” “hate[s]…being asked to define…[his] cooking in two words or less” (“we’re not an Italian restaurant or French and what is ‘American’ exactly?”), and “hate[s] when guests confuse…[him] with Andrew Zimmern.” On that latter point (a case of mistaken identity that persists to this day), Zimmerman describes how guests wanting to “meet the chef” end up staring blankly at him “a look that says ‘you’re not who we wanted to meet.’” Graciously, he jokes that “sometimes I’ll just stand there at their table chewing on a bull’s testicle or crunching on fried grubs, but you can tell it just isn’t the same.”

Internet archiving, though somewhat irregular in its capturing of Sepia’s website, offers a rather complete look at 2015’s menus. The following are representative dishes from across the year:

- “Fluke Crudo, Green Apple, Avocado, Chilled Jicama Consommé”

- “Potato Gnocchi, Pork and Oxtail Sugo, Grana Padano, Rosemary”

- “Sweet Potato Tortoloni, Matsutake Mushrooms, Dashi, Spruce”

- “Buckwheat Agnolotti, Chevre, Kale, Watercress, Marcona Almonds”

- “Pasta alla Chitarra, Lobster, Saffron, Capers, San Marzano Tomato”

- “Soft Shell Crab, Dandelion Greens, Cucumbers, Smoked Date Molasses”

- “Arancini, Carnaroli Rice, Truffle, Salsify, Celery Root, Black Trumpets”

- “Duck Breast, Pumpkin, Fig Molasses, Fennel, Sunflower Seeds”

- “Strip Steak, Beef Shank Pave, Sunchoke, Cheddar, Coffee, Burnt Cinnamon Jus”

- “Berkshire Pork Collar, Apple, Saguinaccio, Parsnip, Black Vinegar”

- “Cod, Shrimp, Orange, Black Radish, Pumpkin Seed Broth”

- “Halibut, English Peas, Jowl Bacon, Razor Clams, Herb Jus”

2016 would be defined by the first rumblings regarding Nony and Zimmerman’s second restaurant: Proxi. For the sake of brevity, you will not dwell too much on this concept (especially now, with Jennifer Kim’s introduction as chef de cuisine, that it could merit its own closer look). However, its announcement would offer some further insight into Sepia as it approached its 10th birthday.

Proxi, with its embrace of Indian, Japanese, Malaysian, Mexican, Spanish, Thai, Vietnamese, cuisines, would be about “big direct flavors” and a “direct cooking style” relative to the more “harmonious and subtle” food at Sepia. Zimmerman, additionally, would get to cook over live fire at the new property (“something we can’t do at Sepia”) and explore facets of his “culinary personality” he hadn’t expressed before while “expand[ing] the audience” of his food. Elsewhere, Proxi would be described as “a lot more like eating at home” and more “boisterous” than its Michelin-starred neighbor.

Back at Sepia, the year would see Griffin Elliott depart as head bartender—being replaced by Keith Meicher (a fellow “Scofflaw vet”). This would be followed in 2017 by the departures of Shuman, being replaced as pastry chef by Sarah Mispagel (formerly of Nightwood), and Hon, being replaced as wine director by Jennifer Wagoner (formerly of StripSteak by Michael Mina in Miami Beach).

Despite such a series of consequential changes, Sepia would—in 2018—earn three stars (“excellent”) for the third time from the Chicago Tribune. Making three visits to the restaurant (something that has disgracefully fallen out of practice at the paper), Vettel would praise dishes like “scallops…over a creamy blend of peaches, pancetta and porcini…with cremini mushrooms,” “crab-ricotta-filled agnolotti with English and snap peas,” “brioche-crusted halibut with morels, white asparagus and spring onions,” and “roasted rabbit slices” with “nuggets of garlicky rabbit sausage in their centers…black garlic gnocchi…[and] a thickened sauce of rabbit jus, white port and cognac…mounted with foie gras instead of butter.” Zimmerman, in turn, would heap praise on chef de cuisine Adam Zoscsak when asked how he was able to manage “such a high level” of cooking both at Sepia and Proxi. (Mispagel, it should be mentioned, also received praise for her “strawberry crostata,” “deconstructed Meyer lemon torte,” and a “a tempered chocolate mousse dome, surrounded by sarsaparilla ice cream, cherries, smoked vanilla cream, chocolate meringue and cocoa nibs.”) That year, Sepia would also be named a semifinalist for the “Outstanding Service” honor at the James Beard Awards.

2019 was a quiet year by all accounts—with Sepia perhaps only notably being named the 38th best restaurant in the city on Vettel’s “semi-regular” Phil’s 50 list. The dawn of 2020 saw Mispagel leave as pastry chef, being replaced by Lauren Terrill (formerly of Swift & Sons). Zoscsak would also leave as chef de cuisine, with Kyle Cottle (who worked alongside Ryan Pfeiffer at Blackbird for five years) taking his place.

But the year would undeniably be colored by the pandemic and its associated lockdowns. Zimmerman took some time to formulate a plan, recognizing that “Michelin-star food doesn’t go in a box very well” and that it would be a challenge to channel his team’s energy “into making food that’s going to travel well and that’s still built around the same core values of quality, attention to detail, and deliciousness that we would put on a plate.”

In May, the chef would launch Sepia’s to-go operation, with all food being offered “cold with reheating instructions…so dishes don’t linger ‘in the temperature danger zone’ and make someone sick.” He would also only offer pickup in order to “avoid third-party delivery companies that aren’t necessarily invested in the integrity of the dish en-route” and that charge fees described as “criminal.”

Zimmerman ultimately approached this difficult period as an “opportunity to do dishes that otherwise wouldn’t really make sense in the restaurant’s usual form.” Offerings included “Whipped French Onion Dip” (with potato chips and caviar), “Salmon Coulibiac,” “Lasagna Bolognese,” “Poulet Roti Grand-Mère” (with Parker House rolls), “Roast Rack of Berkshire Pork,” “Honey-Glazed Duck Breast,” a “Smash Burger” (with onion rings), “Belgian Ale Braised Beef Short Ribs” (that classic recipe from 2009), and “Grilled Rack of Lamb” alongside desserts like “Tiramisu,” Champagne Cake,” and “Chocolate Fondant Cake.”

It would be a long road to a full reopening in 2021, and that year would see still more changes: Wagoner would depart as wine director, being replaced by Alex Ring (formerly of Oriole, Spiaggia, and Lazy Bear) and Terrill would depart as pastry chef, being replaced by Erin Kobler (formerly of Swift & Sons and Bellemore).

Nonetheless, this very team—Nony, Zimmerman, Meicher, Cottle, Ring, and Kobler—would remain in place through Sepia’s 15th anniversary (in 2022) and its JBF “Outstanding Hospitality” nomination earlier this year.

That, at last, brings you to the present day; however, it may be worth dwelling on a handful of representative dishes from 2021-2022 just to get a sense of what the kitchen has been up to after the pandemic:

- “Golden Kaluga Caviar, Smoked Halibut, Grilled Spinach, Shiro Dashi Butter”

- “Foie Gras Tart, Rose Gelée, Peach Jam, Aged Balsamic”

- “Sweet Corn Velouté, Parisienne Gnocchi, Pickled Blueberry”

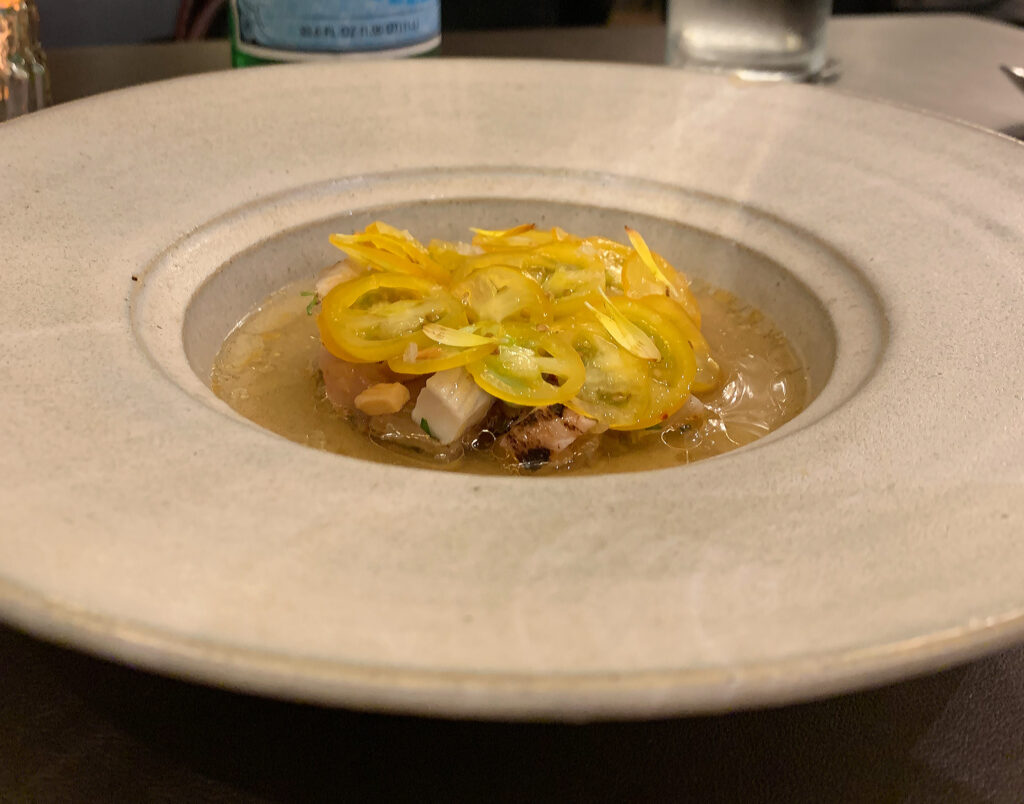

- “Hiramasa Crudo, Baby Tomato, Almond, Tikka Masala Consommé”

- “King Crab Chawanmushi, Sauce Nantua, Hon Shimeji Mushroom”

- “Foie Gras Chawanmushi, Sauce Périgord, Porcini Mushroom”

- “Roasted Crab Rice, Old Bay Crispies, Sungold Tomato”

- “Sourdough Cavatelli, Parmesan, Pine Nut, Summer Squash”

- “Miso Roasted Scallop, Carolina BBQ Butter, Snap Pea”

- “Tempura Eggplant, Peach, Coconut, Jerk Spice”

- “Venison Shabu-Shabu, Chestnut, Barley, Huckleberry, Matsutake Mushroom”

- “Country Fried Truffled Chicken, Sweet Potato, Sauce Albufera”

- “Berkshire Pork Confit, Cherry Barbeque, Peanut, Five Spice”

- “Grilled Beef Striploin, Sweet Corn, Bone Marrow Chimichurri, White Cheddar Churro”

- “Hay Grilled Striploin, Smoked Bone Marrow Hollandaise, Broccoli, Tempura Crispies”

- “Steelhead Trout en Croute, Buttermilk, Cucumber, Dill”

- “Roasted Duck Breast, Cherry Duck Jam Donut, Turnip, Root Beer Jus”

- “Rohan Duck Breast, Honeycrisp Apple-Hoisin, Charred Cabbage, Sesame Buckwheat Corndog”

- “Ricotta Agnolotti, Morel Mushroom, English Pea, Parmesan”

- “Wood Roasted Ratatouille Lasagna, Parmesan, Preserved Tomato Sauce, Olive”

- “Alpine Cheese & Brown Butter Biscuit, Pleasant Ridge Reserve, Honey, Pickled Onion Jam, Radish”

- “Miso Butterscotch Pudding, Puffed Grain Krispy Treat, Candy Cap Mushroom Ice Cream”

- “Jivara Chocolate Cannoli, Peanut Butter & Roasted Coco [sic] Nib Ice Cream, Tamarind”

- “Dark Chocolate Brownie, Caramelized Banana, Peanut, Toasted Marshmallow”

- “Goat Cotton Cheesecake, Chamomile Strawberry Sorbet, Cajeta”

- “Crispy Sage French Toast, Honeycrisp Apple, Sweet Potato Ice Cream, Popcorn”

Stylistically, it is easy to see the common thread that connects this work to that of Zimmerman in the 2010 and 2015 menus previous listed. You find that same Italian influence (via the restaurant’s perennial pastas, a crudo, and a playful take on cannoli) along with glimpses of French technique (velouté, trout en croute, ratatouille, various sauces). Woven within these preparations are various familiar seasonal Midwestern ingredients: apple, corn, mushroom, sweet potato. Proteins like pork, steak, and duck also remain prominent, forming friendly anchors of satiation for customers who might otherwise feel averse to fine dining’s daintiness.

While Japanese elements like dashi and miso did indeed feature on the chef’s earlier menus, Sepia has trended toward featuring more and more of these techniques: shiro dashi butter, chawanmushi, miso roasted scallop, tempura eggplant, venison shabu-shabu, tempura crispies, miso butterscotch pudding, cotton cheesecake. This development not only speaks to an increasing mastery of the cuisine in the wake of Proxi’s opening (Zimmerman, to be fair, shared a chawanmushi recipe as early as 2016), but to the widening of the “contemporary American” umbrella over time. Changing tastes have also, in the same manner, seen Chinese (five spice, hoisin), Indian (tikka masala), Jamaican (jerk), and Mexican (cajeta, churro) influences come to the fore.

This broadening of Sepia’s culinary horizons might seem to threaten its relationship with Proxi on the surface. Just what is the difference between the two concepts—other than quotidian concerns of pricing and scale—if the former property embraces the same worldly bent? Yet, Sepia retains an undercurrent of Americana: nostalgic flourishes like Old Bay crispies, Carolina barbecue butter, country fried chicken, a cherry duck jam donut, root beer jus, a sesame buckwheat corndog, a biscuit, a “Krispy Treat,” toasted marshmallow, and French toast. Zimmerman’s cuisine has displayed this dimension before—you note the “Frog’s Legs Beignet” from his 2010 menu (though one can argue this is not strictly “American”)—but it seems especially prominent now.

In other words, as Sepia’s range of influences has expanded, the restaurant has also plunged deeper into the comforting, somewhat irreverent side of the national cuisine. Each side of this equation works to ground the other, with the resulting menu being definable neither as markedly “global” nor as some kind of “fine dining junk food” concept. Instead, Zimmerman, Cottle, and Kobler’s work embraces all the tensions and contradictions trying to define “contemporary American” today entails.

Thus, while Boka has remained surprisingly static in its culinary vision—and North Pond, under César Murillo, has combined Bruce Sherman’s philosophy with a bit more of that molecular gastronomy bent—Sepia has reflexively grown over time to embody a rather eclectic perspective. It will be worth exploring just how coherent and enjoyable the results of this singular approach are in practice.

You have visited Sepia now and then over the past decade but, for the purposes of this article, will focus on a series of three meals conducted from September through October of this year. This period has allowed you to get a sense of the menu’s dynamism while dining on different days of the week in different sized parties, likewise, has offered a chance to note differences in the restaurant’s pacing and consistency.

With all that said, let us begin.

That familiar corner of Randolph and Jefferson, located in the narrow neighborhood partition known as “West Loop Gate,” has already caught your eye a few times over the years. First, it was with the demise of Bellemore: fatally mismanaged by Boka Restaurant Group before being unceremoniously replaced by a safe, crowd-pleasing Italian concept. Later, Alla Vita (as the resulting restaurant would nonsensically be titled) would feature as part of a trilogy of reviews—confirming that Boehm, Katz, and their favorite Michelin-starred henchman Lee Wolen no longer lead Chicago’s dining scene but, rather, are content to milk consumers with lowest-common-denominator fare.

More recently, as part of a separate series examining Chicago’s up-and-coming omakase genre, you took a look a bit further down the street at CH Distillery. There, despite lingering bitterness regarding Malört’s manufactured “popularity,” you found Jinsei Motto: an uplifting story of two chefs who turned a pandemic pivot into a full-fledged business offering a flavorful, personable expression of sushi (that, perhaps, is only missing a bit more technical mastery).

Along the way, construction was completed at 609 Randolph—the 15-story boutique office building located (adjacent to avec) on the opposite corner—and leases were signed. Alla Vita and Jinsei Motto now both benefit from surging lunch crowds, and pizza, pasta, or the occasional makizushi must seem heaven-sent to those working on the block.

This was once the land of the business lunch after all, with West Loop Gate offering those working in the Loop itself an array of options just over the river but short of the highway (and the couple extra blocks of walking it entails). Of course, office occupancy rates have taken time to rebound in the wake of the pandemic, and the neighborhood must compete with all that lies to the north: venerable steakhouses and LEYE concepts as far as the eye can see. However, those following Wacker to its western limit will find a Beatnik, a Beatrix, and Bar Mar. Trekking a bit further, you reach Gibsons Italia and, a couple blocks after that, the aforementioned Alla Vita, avec, and Jinsei Motto.

Nonetheless, West Loop, today, can now call itself home to a burgeoning tech industry while, at the same time, having welcomed more longstanding companies looking to downsize and modernize their headquarters. The neighborhood is no longer a frontier of fine dining for the rest of the city but exists as its own ecosystem in which residential and office towers spring up in concert. Who really wants to walk east, over the highway, in search of just a few more lunch options amid a sea of eateries in Fulton Market and throughout the prime stretch of Randolph Restaurant Row?

Yes, Sepia sees itself competing with myriad concepts to the west, each more primely positioned to snare customers working in the same, densely populated area. Meanwhile, the pool of patrons located to the east—where the restaurant retains some natural advantage—remains more shallow than before. And those who remain, too, can choose from pizza, steak, and sushi (to say nothing of delivery) before the thought of taking in a refined “contemporary American” meal even comes to mind.

Perhaps that is why Sepia, after more than a decade topping “best business lunches” lists, has bowed out of offering any afternoon service since reopening in the wake of the pandemic. Proxi, for what it’s worth, has not resumed offering lunch or brunch either. Maybe this will all change as conditions do, but you cannot blame Nony and Zimmerman for moving slowly and not overextending themselves.

Instead, Proxi and Sepia compete solely in the evening: Bib Gourmand and Michelin-starred properties (respectively) whose high status justifies further travel. These restaurants no longer debase themselves—via sandwiches and salads—to lure in those faceless, fickle swarms of office workers. They stand, proudly, as spots worthy of a real dinner. At the very least, they invite you inside to enjoy a dignified happy hour (and maybe find yourself lingering a while longer after that).

Yet, as you walk along Randolph and make the turn onto Jefferson, you find yourself suddenly feeling isolated. All of the Restaurant Row’s pulsating energy, which slowly builds from the other side of the river before bursting to life past the highway, is dissipated by a one-way street that is home to an antique store, an understated Hilton hotel, and a 102-year-old print shop. The parade of post-work imbibers—lured into the all-day establishments on the other side of the intersection or seeking their pleasure further afield—does not trickle this way. Even those entering Proxi do so from the building’s north-facing side.

Searching for Sepia, thus, entails separating yourself from the stream of merry consumers ready to celebrate the end of another shift. The restaurant’s signage, award-winning (along with other graphics) at the time of opening, looks now as though it could belong to any other storefront: an offshoot of the printer or a rival to the antiquarian perhaps. Unlike so many of Randolph’s other outlets further west—streets like Green, Peoria, and Morgan that lead you straight to additional bars and eateries—this block of Jefferson feels every bit a dead end: a return to the city’s cold, commercial side rather than a hospitable escape.

Knowing, nonetheless, where you are going—searching, expectantly, for that Michelin star at the end of the tunnel—you trace your way to the middle of the block and the familiar brick building at 123 N Jefferson.

Sepia’s façade, when you gaze upon it, cuts a subdued figure. Sets of dark metallic window frames rise four stories high, being matched by a slender fire escape that stretches over the ground floor and climbis up along the left side of the structure onto the roof. The front door is rendered in dark paneled wood, with additional surrounding planks serving to frame the entrance in line with the towering glass to its side.

Those bricks, when you inspect them more closely, boast a rich reddish tone. They are broken up by small segments of stone—some distinguished with pinwheel engravings—and culminate in a neat, squared cornice with a range of rectangular indentations. If you turn the corner into the alley that separates Sepia from Proxi, you may note the browner, more faded brick that is still emblazoned with the remnants of a previous tenant: Clifford Peterson Tool Company. Even the numbers signifying the street address, though they’ve changed places over the years, look original to the building.

The overall effect matches many of the other structures throughout the neighborhood: sturdy old warehouses awaiting redevelopment in the manner of more floors, more glass and steel. Yet, if the restaurant looks a bit worn, it never seems dingy. It displays the pleasant patina of age—of timelessness—that is reflected in Sepia’s signage, an image of “Old Chicago” which glows in the concept’s namesake tone at night.

The building, framed by carefully manicured planters (perhaps the one giveaway as to just how curated this façade actually is), speaks to the kind of aesthetic Hogsalt has grown so adept at fabricating. However, here (as at North Pond) the history is real. It amounts to a self-assured, permanent quality that connects the cuisine’s “contemporary American” ethos to something already—deeply–known.

Stepping through Sepia’s entrance, you find a vestibule done up in more brick, more wood, and bathed in warm lighting. Climbing a few steps, you make your way to another door—this time with a window at the center—that deposits you directly in front of the host stand. The counter is weighty and rendered in wood. Immediately behind it sits a cabinet—also in wood—containing glass jars and decanters that call an old-timey apothecary to mind. Though the staff checks customers in and shuffles them along at an admirable pace, the temporary scrum allows you a look around.

To your right, you find a sweeping U-shaped bar composed of a white marbled countertop with a wooden trim. Seven stools lie before it—bookended by hourglass-shaped crystal lamps—while three tiers of bottles are set within more cabinetry located behind. Opposite the bar, separated by a slender column and a pony wall, you come to the restaurant’s lounge. The space is defined by velvety gray banquettes, white marbled café tables, wood paneled walls, hanging lamps (fitted with Edison bulbs of course), and those windows looking back out onto Jefferson. One deliciously thematic element is an antique folding camera, which sits in the corner closest to the entrance and is matched by vintage black-and-white photos hanging on the lounge’s north and south walls.

Returning to the host stand, you are met with a cheery greeting, your name is checked off, and a member of the team—menus in tow—leads the party beyond the bar. The hostess makes idle small talk, a touch that should never be taken for granted, as she traces a path into the dining room. The space, as you approach it, revolves around a slender central column. Four crystal chandeliers, sheathed by cylinders of glass, are positioned equidistantly at 45º angles from this point. The floor is lined with four-top tables while wood-clad walls (forming the other side of the bar and running along the opposite end of the room) contain two-top banquettes. Those walls are also set with distressed mirrors, which serve to expand your perception of the space.

Other notable details, running along the dining room’s outer walls, include floor-to-ceiling wine racks (wood set onto brick), a set of hulking metal doors (an old warehouse elevator?), and hanging planters. Vintage photographs (as seen in the lounge) hang in certain corners while hexagonal tiling and thick, brown curtains run throughout the entire restaurant. Only a couple semi-private rooms, with seating for up to eight in dramatic, cavernous quarters, hide just barely out of sight toward the rear and the kitchen/bathrooms.

Ultimately, especially when you consider how spaciously the tables are arranged, Sepia’s dining room is more about function than grandeur. You think this is echoed throughout the entire restaurant, which is really only enriched by elements like the folding camera and certain ornate pieces of glassware, and it certainly harmonizes with the building’s worn but dignified façade. The overall effect is that the restaurant, despite its Michelin star, feels conventional and recognizable. It feels like a place that could exist back in your hometown. It feels classic.

Depending on the expectations a given guest brings to the table, they may be a bit skeptical of this aesthetic. Despite a shared sense of history, Sepia cannot trade so much on its surrounding environment like North Pond. Instead, it exists in a neighborhood where Kehoe Designs can concoct an “Instagrammable moment” using nothing more than some trellises and cheap hanging fabric. Consumers drawn to fine dining today care almost as much about how they look (and how they are recorded) enjoying the experience as they do the ultimate quality of the service or food. And Sepia, unless you happen to be a large party dining in one of its semi-private spaces, does not offer that kind of signature snapshot.

Just the same, the restaurant is comfortable in its skin. You think of Boka—with its hodgepodge of tacky celebrity portraits and anthropomorphic animals—as a place that, at maturity, is trying too hard to seem hip. But patrons, no doubt, enjoying posing in front of these details. Novelty and a sense of irreverence certainly form an antidote to fine dining’s stereotypical snobbery. Yet Sepia, you have already seen, weaves that attitude into the actual cuisine while Boka continues serving a poor facsimile of what Eleven Madison Park was doing a decade ago.

At best, Nony has curated a space that now seems a bit plain. You hesitate to use the word “dated,” for many a new concept would love to draw on the history of the old brick and metal accents. And maybe, instead of irreverence, there is something comfortable about sitting in a dining room that feels familiar. At the very least, it offers a blank canvas for you to define your own evening and to allow the other aspects of the experience to really take hold, which may be a good or a bad thing depending on their actual quality.

Upon reaching the table, you take your seat and, after indicating your preference of water to the oncoming busser, turn your attention to the menus before you. Sidestepping the leatherbound wine tome for now, you find an assortment of libations on the side opposite the food.

Head bartender Keith Meicher’s work comprises 10 different cocktails at present, each priced between $14 and $18 (a range that generally accords with the neighborhood and with other concepts at this level). Admirably, he also avoids the temptation of offering “premium” or “reserve” drinks that, while sometimes interesting, represent a form of premiumization that pressures consumers to spend more money so as not to feel they are imbibing something “lesser.” (Of course, it’s never hard to substitute one liquor for another from the top shelf should you so desire.)

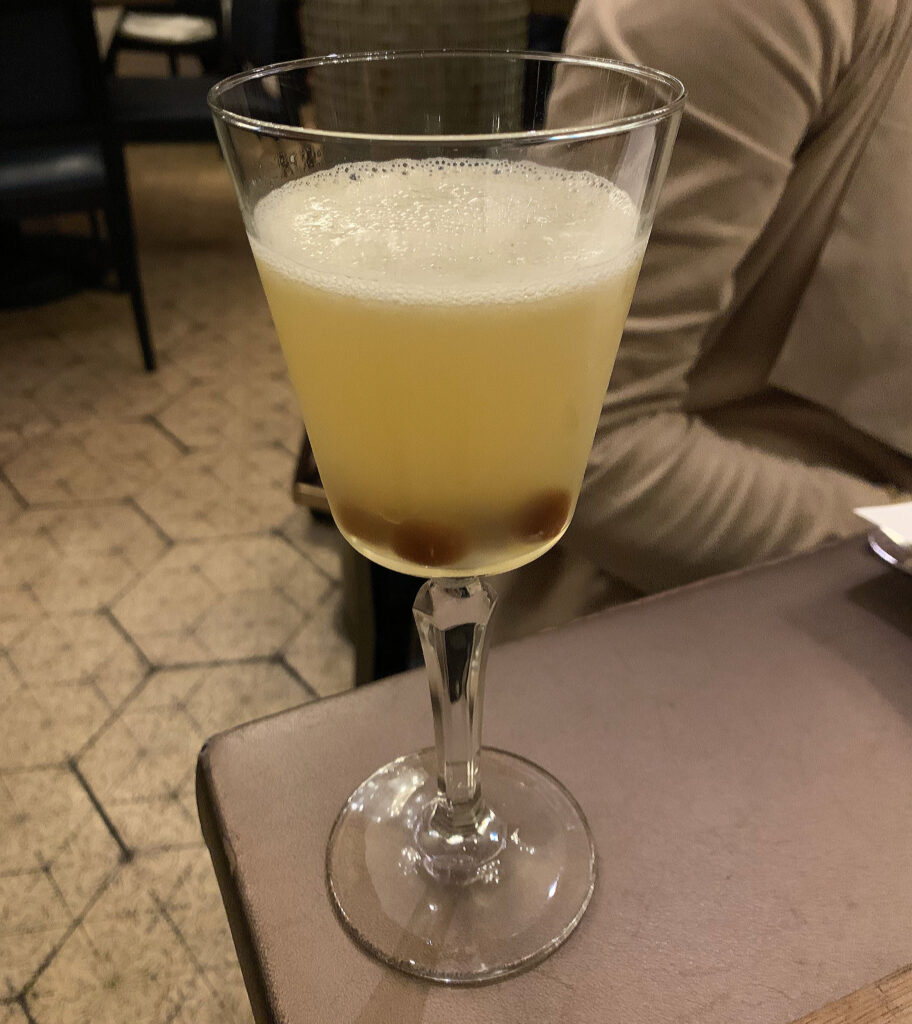

Of the current selection, you have sampled four cocktails. The “Pulaski at Night” (Pisco, Bruto Americano, rhubarb, lime, ginger, Chinese five spice, egg white) is pleasantly bracing and herbaceous but just a little medicinal to your palate. The “New Romantic” (Tito’s Vodka, lemon, plum-cinnamon jam) is a pristine play on a “Gin & Jam” that goes down dangerously easy. The “Single Barrel Old Fashioned” (Koval Single Barrel Bourbon, Angostura, demerara, saffron ice) is perfectly balanced with a kiss of wood, a bit of sweetness, a hint of tang, and absolutely no heat on the finish. Lastly (and best of all), the “Savoir Faire” (Thai basil-infused rum, smoked pineapple, chrysanthemum, boba) is beautifully executed with a layered, resonant sweetness and a well-judged undercurrent of florality. Overall, three of the four cocktails really impress, and you think Meicher is doing great work.

Along with a short list of five “Seasonal Beers” (predominantly sourced from Chicago along with one from Maine and one from Cleveland), you also find the “Wines by the Glass” on the opposite side of the food menu. This is wine director Alex Ring’s province, and the selection merits being considered in its totality:

Champagne + Sparkling

- NV Borgoluce “Lampo”Prosecco di Treviso ($14)

- NV Raventós i Blanc “de Nit” Rosado Cataluyna ($17)

- 2021 Carboniste “Gomes Vineyard” Albariño ($19)

- 2016 Ferrari “Perlé” Trento ($20)

- NV J. Lassalle “Cuvée Préférence”Champagne 1er Cru ($31)

White

- 2020 Adega de Demo “Bitoku”Ribeiro ($16)

- 2022 Weingut Keller “Weissburgunder & Chardonnay” Rheinhessen ($21)

- 2020 Comte Henry d’Assay Sauvignon Blanc Touraine ($18)

- 2010 C.H. Berres “Urziger Würzgarten” Riesling Kabinett Mosel ($20)

- 2016 Didier Dagueneau “Jardins de Babylone” Sec Juraçon ($24)

- 2020 Dominique Cornin “Les Serreuxdières” Mâcon-Chaintré ($19)

Rosé & Orange

- 2022 Couly-Dutheil “René Couly” Chinon Rosé ($16)

- 2021 Enderle & Moll “Weiss & Grau” Baden ($15)

Red

- 2019 Noa “Noah of Areni” Vayots Dzor ($18)

- 2021 Marcel Lapierre Morgon ($24)

- 2021 Deovlet Pinot Noir Santa Barbara County ($22)

- 2017 Aperture Cellars Red Blend Alexander Valley ($28)

- 2016 La Rioja Alta “Viña Aradnza” Rioja Reserva ($25)

Starting with the sparkling, you find a range of value-driven options under $20 like a Prosecco, a Spanish rosé, an a domestic Albariño. Of these, the latter two are produced using the méthode traditionnelle (with secondary fermentation occurring in bottle), a process that replicates Champagne. However, with the jump up to $20, you can get the “Perlé,” a vintage-dated sparkler that is also made in the traditional method but has the added benefit of utilizing 100% organic Chardonnay grapes. Thus, this option (while still a representing a good value) comes even closer to a blanc de blancs bubbly from France. However, those who will not settle for anything but the real thing, will find that $31 secures them a great representation of the appellation: a Pinot Meunier-dominant, non-vintage blend made from premier cru vineyards that offers both approachability and depth.

With the whites, you see a pronounced Old World focus; however, the selection ticks two major boxes: Sauvignon Blanc (from the Loire) and a fuller-bodied Chardonnay (from the Mâcon region of Burgundy). These are mainstream choices that are sure to please guests who favor popular examples of the varieties from Sancerre, New Zealand, or California. Beyond that, you find a round and refreshing Ribeiro (representing the value pick), a bright blend of Pinot Blanc and Chardonnay (from the esteemed producer Keller), and an off-dry Riesling with an impressive 13 years of age (how many restaurants can offer that by the glass?). The Dagueneau Juraçon is a bit of an oddball in the top-priced spot, yet it offers the kind of richness and concentration (along with a famous name) those spending more might want.

The rosé and orange category is short but sweet—and, frankly, you are excited to see it featured in general. Coming from a notable Loire producer, the Couly-Dutheil is fresh, fruity, and drinkable. The “Weiss & Grau,” by comparison, is clean and silky with a pleasant tannic bite. It’s a perfect introduction to the orange category from a cult biodynamic estate.

Lastly, with the reds, you once more find a crowd-pleasing spread. First, in the value position, Ring pours a surprising Armenian wine with concentrated cherry notes and a robust texture that, nonetheless, fulfill what guests expect from a baseline option. Moving toward the more premium selections, lovers of Old World wines will find—in the Morgon and Rioja—two classic, characterful pours (from top producers) to choose from. Those who favor domestic, likewise, find themselves rewarded with a rich Pinot Noir and an even richer Malbec/Merlot blend. While something Italian might be worth considering, Ring covers all his bases with aplomb.

Overall, you must praise this by-the-glass list for the way it balances geekiness and broad appeal. The chosen wines, moreover, are not the same ones you see being poured everywhere else in the city (where some distributors have all but cornered the market in certain categories). Rather, this selection facilitates education (grape varieties being listed in parentheses is a nice touch) and conversation (with the servers or sommelier) for newcomers and oenophiles alike. It encourages a sense of never-ending discovery that gets at the core of what makes fermented grape juice such a fulfilling hobby while, simultaneously, offering a taste of true icons. Yes, you must admit there are at least two choices under each heading that, even as someone that typically opts for bottles, you would not hesitate to order—a high compliment.

All that being said, it is Sepia’s bottle list that shines the brightest. The following are representative selections from throughout the year:

Half Bottles

- MV Champagne Brice “Heritage” ($77)

- 2020 Seehoff “Kirschspiel” Riesling Trocken Rheinhessen ($58)

- 2018 Merry Edwards Sauvignon Blanc Russian River Valley ($60)

- 2020 Weiser-Künstler “Enkircher Ellergrub”Riesling Auslese Mosel ($79)

- 2020 Jean-Philippe Fichet Meursault ($129)

- 2019 Ridge “Lytton Springs” Sonoma County ($62)

- 1996 Château Musar Beqaa Valley ($148)

Magnums

- MV Pierre Paillard “Les Parcelles”Champagne Grand Cru ($239)

- MV Veuve Fourny et Fils “Grande Réserve”Champagne 1er Cru ($265)

- 2016 Robert Weil Riesling Kabinett Rheingau ($125)

- 2015 Duplessis “Vaillons”Chablis 1er Cru ($245)

- 2015 Gut Oggau “Josephine” Burgenland ($270)

- 2007 Oddero “Brunate”Barolo ($445)

- 2011 Clos des Papes Châteauneuf-du-Pape ($495)

- 2011 Ridge “Monte Bello”Santa Cruz Mountains ($945)

Sparkling

- MV Casa de Piedra “Espuma de Piedra”Blanc de Blancs Valle de Guadalupe ($72)

- 2018 Peter Lauer Riesling Sekt Saar ($76)

- MV Schloss Gobelsburg “Brut Reserve” Kamptal ($98)

- MV Marguet “Shaman” Champagne Grand Cru ($129)

- MV Bérèche “Réserve” Champagne ($139)

- MV Pehu Simonet “Face Nord” Champagne Grand Cru ($139)

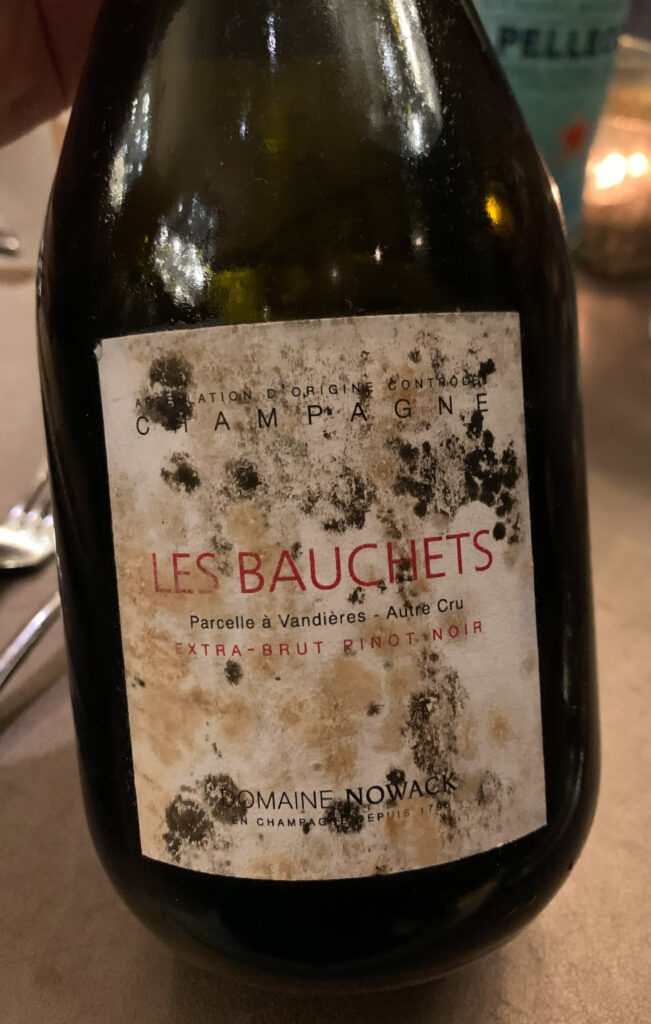

- MV Nowack “Les Bauchets” Blanc de Noirs Champagne ($144)

- MV Pierre Péters “Cuvée de Réserve”Blanc de Blancs Champagne Grand Cru ($159)

- MV Georges Laval “Garennes”Champagne ($164)

- 2018 Thomas Perseval “Tradition”Champagne 1er Cru ($164)

- 2016 Marie-Courtin “Eloquence” Blanc de Blancs Champagne ($168)

- MV Egly-Ouriet “Les Premices”Champagne ($195)

- MV Georges Laval “Cumières”Champagne 1er Cru ($224)

- MV Henri Billiot “Cuvée Laetitia”Champagne Grand Cru ($235)

- 2017 Ulysse Collin “Les Maillons”Blanc de Noirs Champagne ($239)

- NV Egly-Ouriet “Les Vignes de Bisseuil” Champagne ($255)

- 2018 Roses de Jeanne “Haute-Lemblée”Blanc de Blancs Champagne ($276)

- NV Benoit Dehu “Cuvee de l’Orme”Champagne ($285)

- NV Jérôme Prévost / La Closerie “Les Beguines”Champagne ($288)

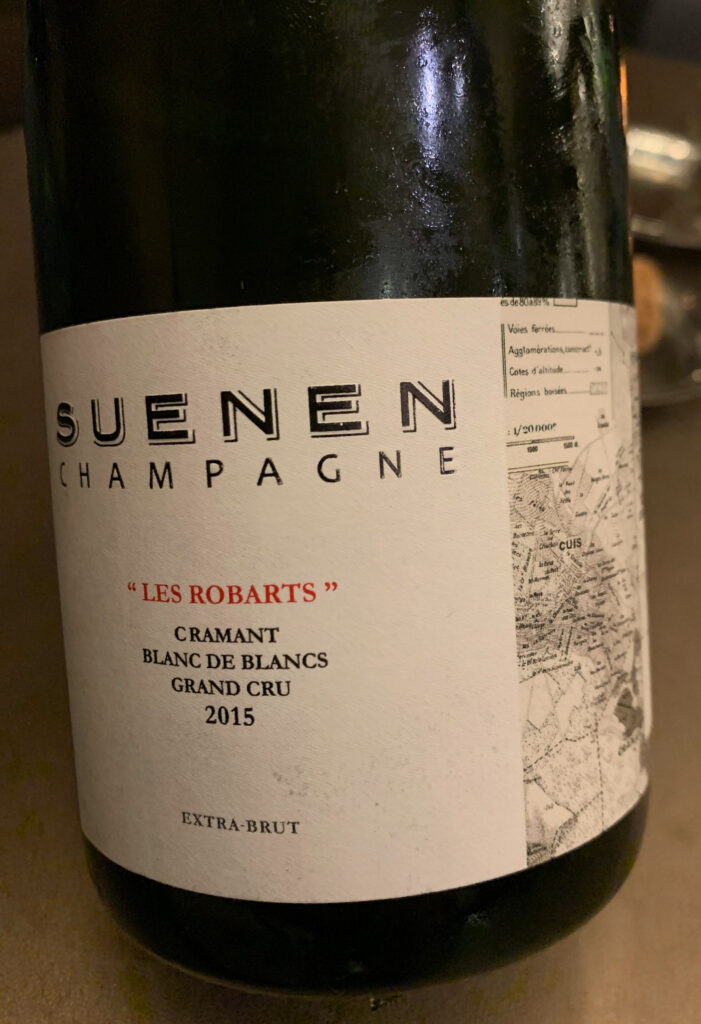

- 2015 Suenen “Les Robarts”Blanc de Blancs Champagne Grand Cru ($325)

- MV Jacques Selosse “Initial” Grand Cru Blanc de Blancs Champagne ($485)

- 1990 Veuve Clicquot “Cave Privée”Rosé Champagne ($496)

- 2004 Louis Roederer “Cristal”Champagne($600)

White

- 2021 Weiser Künstler Feinherb Riesling Mosel ($59)

- 2020 Maison des Ardoisières “Silice”Savoie ($66)

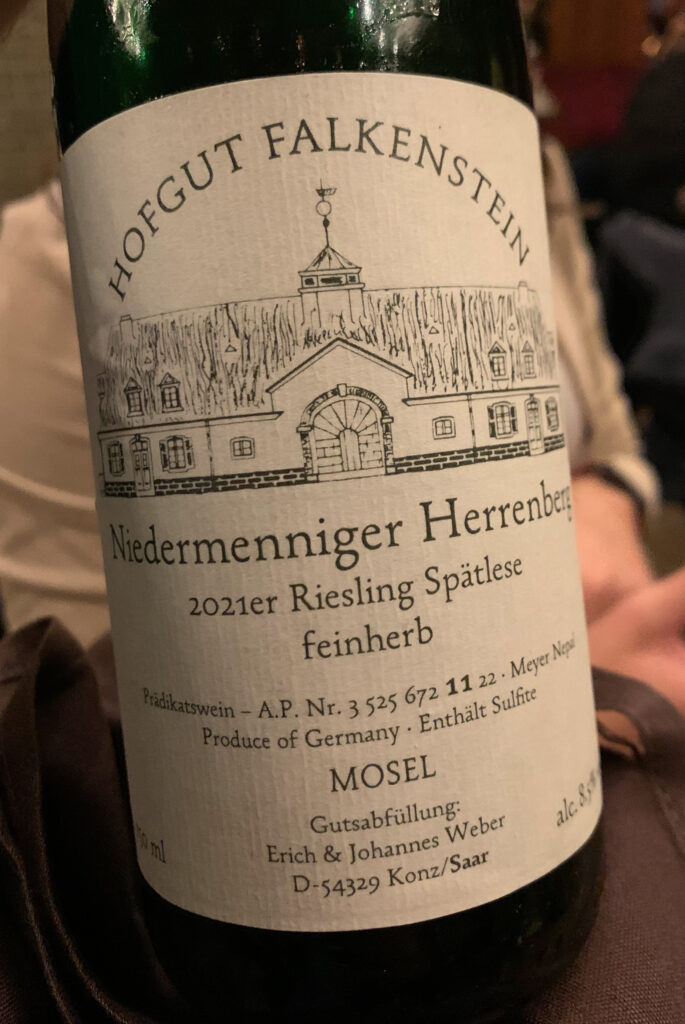

- 2021 Hofgut Falkenstein “Niedermenniger Herrenberg”Riesling Kabinett Trocken Mosel ($74)

- 2017 Venica “Ronco delle Cime”Friulano Collio ($74)

- 2020 Weingut Keller Riesling Trocken Rheinhessen ($75)

- 2013 Forstmeister Geltz Zilliken “Saarburger Rausch”Riesling Kabinett Saar ($79)

- 2019 Lingua Franca “Avni” Chardonnay Willamette Valley ($89)

- 2020 Thibaud Boudignon Anjou Blanc ($89)

- 2007 Robert Weil “Kiedrich Gräfenberg”Riesling Spätlese Rheingau ($99)

- 2021 Nanclares y Prieto “Paraje Mina”Rias Baixas ($111)

- 2019 Passopisciaro “Passobianco” Sicilia ($111)

- 2020 Cantina Terlan “Terlaner”Südtirol-Alto Adige ($113)

- 2018 J.J. Prüm “Wehlener Sonnenuhr”Riesling Spätlese Mosel ($118)

- 2015 Lail “Blueprint” Sauvignon Blanc Napa Valley ($120)

- 2018 Domaine du Collier Saumur Blanc ($124)

- 2005 Schlossgut Diel “Dorsheimer Burgberg”Riesling Auslese Nahe ($125)

- 2020 Kumeu River “Hunting Hill”Chardonnay Auckland ($131)

- 2021 Walter Scott “Cuvée Anne”Chardonnay Willamette Valley ($131)

- 2017 Domaine Rougeot “Sous la Velle”Meursault ($135)

- 2016 A & JF Ganevat “Fortbeau”Côtes de Jura ($139)

- 2008 Dönnhoff “Schlossbockelheimer Kupfergrübe”Riesling Spãtlese Nahe ($139)

- 2020 Domaine du Pélican “Grand Curoulet”Savagnin Ouillé Arbois ($155)

- 2020 Morey-Coffinet “Climat du Val”Auxey-Duresses 1er Cru ($158)

- 2017 Bindi “Kosta’s Rind”Chardonnay Macedon Ranges ($162)

- 2015 Cantina Terlan “Novadomus”Südtirol-Alto Adige ($162)

- 2008 Trimbach “Cuvée FrédéricEmile”Riesling Alsace ($162)

- 2016 Gut Oggau “Weiss” Burgenland ($163)

- 2017 Domaine Méo-Camuzet “Clos Saint-Philibert”Hautes-Côtes de Nuits ($164)

- 2007 Weingut Keller “Westhofener Kirchspiel”Riesling Auslese Rheinhessen ($170)

- 2018 Domaine Guiberteau “Brézé”Saumur ($176)

- 2019 Tiberio “Fonte Canale”Trebbiano d’Abruzzo ($178)

- 2018 Domaine Didier Dagueneau “Blanc Fumé de Pouilly”($179)

- 2009 Domaine Marcel Deiss Altenbergde BergheimAlsace Grand Cru ($188)

- 2018 Domaine Michel Lafarge “Vendages Seleccionées”Meursault ($192)

- 2015 Emidio Pepe Pecorino d’Abruzzo ($195)

- 2008 Gravner Ribolla Gialla Friuli-Venezia Giulia ($198)

- 2016 Schäfer-Fröhlich “Bockenauer Felseneck”Riesling Trocken GG Nahe ($198)

- 2016 Domaine Guiberteau “Clos des Carmes”Saumur ($206)

- 2020 Jean-Marc Pillot “Les Masures”Chassagne-Montrachet ($215)

- 2012 Catena Zapata “White Bones”Chardonnay Mendoza ($225)

- 2015 Domaine Didier Dagueneau “Buisson Renard”Pouilly Fumé ($264)

- 2016 Domaine Bernard Moreau “La Maltroie”Chassagne Montrachet 1er Cru ($398)

- 2020 Weingut Keller “Hubacker”Riesling GG Rheinhessen ($495)

- 2012 Domaine Vincent & Sophie Morey Bâtard-Montrachet Grand Cru ($695)

- 2017 Domaine des Comtes Lafon “Poruzots” Meursault1er Cru ($788)

Red

- 2021 Anne Sophie Dubois “l’Alchemiste”Fleurie ($77)

- 2020 Chacra “Barda”Pinot Noir Patagonia ($78)

- 2013 Clendenen Family Nebbiolo Santa Maria Valley ($94)

- 2020 Alain Graillot Crozes-Hermitage ($98)

- 2019 Enderle & Moll “Liaison” Pinot Noir Baden ($98)

- 2017 Roagna Langhe Rosso ($116)

- 2010 R. Lopez de Heredia “Viña Tondonia”Rioja Reserva ($124)

- 2017 Mas de Daumas Gassac Languedoc ($136)

- 2018 Trediberri Barolo ($140)

- 2014 Elvio Cogno “Pre-Phylloxera”Barbera d’Alba ($155)

- 2019 Auguste Clape “Les Vins des Amis”VdF ($161)

- 2017 Domaine Jean Grivot “Les Charmois”Nuits-Saint-Georges ($162)

- 2018 Heitz Cabernet Sauvignon Napa Valley ($181)

- 2019 Matthiasson Cabernet Sauvignon Oak Knoll District ($186)

- 2017 Domaine Méo-Camuzet Marsannay ($187)

- 2006 Château Gloria St. Julien ($194)

- 2018 Snowden “Brothers Vineyard”Cabernet Sauvignon Napa Valley ($224)

- 2012 Domaine Henri Boillot Volnay ($268)

- 2001 R. Lopez de Heredia “Viña Tondonia”Rioja Gran Reserva ($278)

- 2000 Château Sociando-Mallet Haut-Mèdoc ($288)

- 2019 Anne Gros “La Combe d’Orveau”Chambolle-Musigny ($290)

- 2016 Roagna “Faset”Barbaresco ($295)

- 2017 Domaine Confuron-Gindre “Les Chaumes”Vosne-Romanée ($298)

- 2004 Azelia “Bricco Fiasco”Barolo ($314)

- 2012 Fontodi “Flaccianello” Tuscany ($333)

- 2001 Dalla Valle Cabernet Sauvignon Napa Valley ($344)

- 2012 Araujo Estate “Altagracia” Napa Valley ($364)

- 2014 Vietti “Lazzarito”Barolo ($385)

- 2016 Domaine Marquis d’Angerville “Fremiets”Volnay 1er Cru ($392)

- 2018 Pierre Gonon Saint-Joseph ($418)

- 2015 Benjamin Leroux “Caillerets” Volnay 1er Cru ($421)

- 2017 Bartolo Mascarello Barolo ($444)

- 2006 Château Pape Clément Pessac-Leognan Grand Cru ($458)

- 2013 Cerbaiona Brunello di Montalcino ($475)

- 2014 Clos Rougeard “Les Clos” Saumur-Champigny ($488)

- 2014 Ghislaine Barthod “Aux Beaux Bruns”Chambolle-Musigny 1er Cru ($518)

- 2016 Corison “Kronos Vineyard”Cabernet Sauvignon St. Helena ($529)

- 2010 Château Smith Haut Lafitte Pessac-Léognan Grand Cru ($545)

- 2015 Domaine Jamet Côte Rotie ($574)

- 1998 Château Canon-La-Gaffalière Saint-Èmilion Grand Cru Classé ($625)

- 2015 Tenuta dell’Ornellaia “Ornellaia” Tuscany ($698)

- 2016 Opus One Napa Valley ($725)

- 2011 Château de Fonsalette Côtes-du-Rhône ($842)

Taking all this in, it is impossible to deny that Sepia boasts one of the best—if not the best (at least at the one-Michelin-star level)—wine selections in the city. Sure, in the steakhouse stratum, somewhere like Maple & Ash offers an incredible collection (though, when you consider what the bottles go for, not exactly priced to move). Likewise, Les Nomades, 45 years on, offers quite a deep assortment of Champagne, Burgundy, Bordeaux, and Rhône with a mix of deals and (understandable) markups awaiting those who visit this gastronomic grande dame.