After some time spent plumbing the depths of more casual fare, it feels good to get back to the meat of the matter: a fine dining concept looking to offer something Chicagoans have never yet experienced with all the trappings of luxury you so love (to pick apart). At long last, the local dining scene appears to once more be gaining steam—not simply because you find more tasting menus on the horizon but, rather, that these “serious” restaurants signal favorable conditions for chefs (and, yes, their investors) to yet again dream. Reconciling those dreams with reality is, of course, the tricky part; however, it is heartening to see new frontiers being sought after a long period of stagnation.

With Bon Yeon, there is good reason to be optimistic. Chef-owner Sangtae Park and wife/co-owner Kate Park launched the city’s first Michelin-starred omakase in 2018. Two years later, they expanded carefully with a neighboring gastropub. Now, more than five years after first making their mark on Chicago, the Parks have put together their most daring concept yet: one that is bigger and more expensive than their flagship sushi counter. It, too, is located on the same corner of the same block—a third restaurant, a modest empire, in a quiet corridor of West Loop Gate. And the team that taught the city to appreciate raw fish and rice is trying its hand at something more decidedly mainstream: beef.

Chicago can claim a proud tradition of Korean barbecue dating back more than four decades, but this is different. The Parks are taking inspiration from Korea’s native Hanwoo beef (likened to Japanese wagyu) and restaurants like Born and Bred in Seoul, a 45-year-old, Michelin-starred concept serving up a $285 “beef omakase” sourced from the prized cow. You may also note (though it is unclear if Bon Yeon’s owners consciously looked to them as influences) Michelin-starred properties like COTE, with its $125 (now $225) “steak omakase” launched in 2018, and bōm, a new $275 tasting counter staged on custom built-in grills, in NYC.

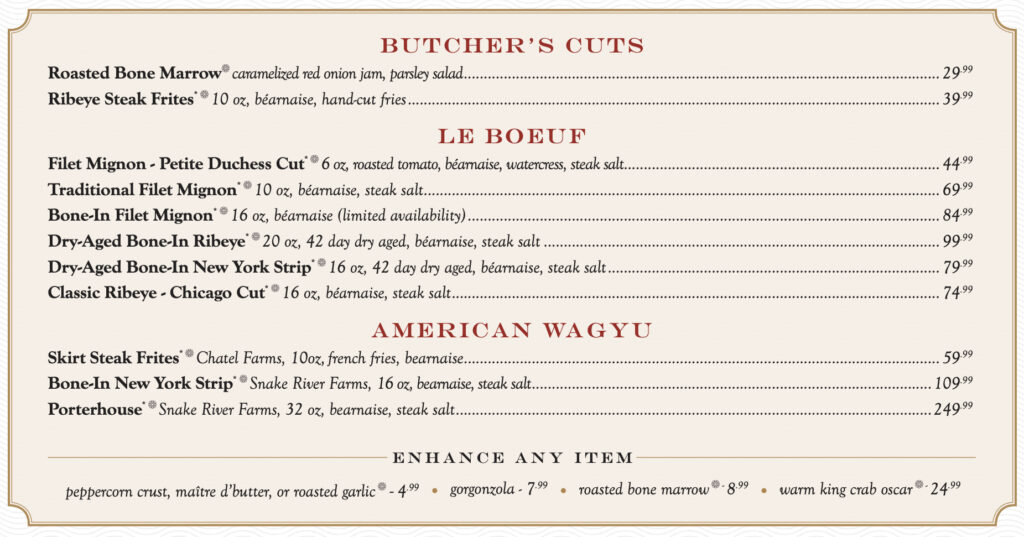

What is “new” to Chicago may not actually be novel by any stretch of the imagination, but that is not the point. The Parks have mined their cultural heritage and retrieved an idea that, while rarefied, is in no way contrived. The “beef omakase” is a valid form, one that has demonstrated lasting appeal in Korea and a broader appeal out east. It seems tailormade for a team that has already served high-end sushi to great success, that has branched out into casual all-day fare, and that now looks to flex their creative muscles through something the city loves most. There is an element of risk—the phrase “selling ice to Eskimos” comes to mind—but just how many Chicago steakhouses have taken to slinging pricey wagyu? You count Bazaar Meat, Maple & Ash, and the RPMs among the prime culprits while even your beloved Bavette’s has, in its own right, given in.

So, this is all to say that Bon Yeon represents a particularly tempting morsel for your critical apparatus and, in the same manner, a chance to get to know the Parks. After all, Yume was the leading force of Chicago’s “omakase boom” and your runaway favorite until a certain Otto Phan came to town. The counter has not quite justified a review of its own (though you have mentioned it in passing elsewhere), so its sister concept presents a golden opportunity to better understand the work of the city’s omakase (now both beef and sushi) luminaries.

The story starts with Sangtae Park, who was born in Korea’s populous port city (the sixth-busiest in the world) of Busan. There, he “grew up on the ocean” and fostered a love of fishing “since junior high school.” At home, Park was “already eating raw fish all the time” (hirame, or flounder, wrapped in kimchi was a specialty of his mother) when, at age 19, he went to work in a Japanese kitchen. However, the “stubborn head chef wouldn’t let him touch any seafood”—“only onions.” So, after finishing work, the budding cook “would buy a lot of fish” then “go home and practice” based on what he learned by watching the chefs. Park “built up his skills” in this manner, eventually enrolling in The Culinary School of Japanese Cuisine for two years and, later, becoming certified as both a Korean and Japanese chef.

For a period of seven years (concurrent with culinary school and those certifications), Park “worked in various [sushi chef and chef] positions over four different fine Japanese restaurants in South Korea.” In 1995, he was finally ready to strike out on his own as proprietor and “master sushi chef” of Biwon, a Japanese restaurant in Busan. After nearly five years there (and a total of 12 cooking Japanese cuisine), Park set his sights abroad.

The chef moved to Chicago and, in 2000, began working as sous chef at Mirai alongside head chef (and future owner of fellow Michelin-starred omakase Mako) B.K. Park. In 2003, his role expanded to include duties at Japonais, where he trained and managed a team of sushi chefs along with helping to create the menu. These restaurants were titans of Japanese cuisine in their era, with both earning three stars (“excellent”) from the Chicago Tribune and the latter being praised for “excellent [Japanese-French] fusion” by The New York Times Magazine.

In 2004, Park entered into the first of several suburban engagements. He spent close to two years as head chef of Hana Japan in Highland Park before, in 2006, working as the head chef of Nikko Sushi in Arlington Heights for about a year. Ultimately, the former city would come to be a more permanent home. Park opened Sushi Badaya in Highland Park near the end of 2006, replacing an existing Japanese restaurant (Maru) and winning acclaim from locals. Using higher quality ingredients, the chef “increase[d] revenue by 200%” (compared to the previous establishment) in his “first year of ownership.” Park would spend more than four years at Badaya before selling it, meeting Kate Kim (originally from Seoul), and marrying her somewhere along the way.

In 2011, the Parks would open Izakaya Yume in Niles. The restaurant would be featured by Mike Sula in the Chicago Reader, where it garnered praise for its “33 different bottles of sake,” “teriyaki and tempura dinners,” takoyaki, dumplings, agedashi tofu, and Korean pajeon—a “thin and crispy” savory pancake “packed with greens.” However, this more “casual spot” also empowered the chef to begin serving “omakase kaiseki, which is seasonal small dishes, sushi, soup, and rice” and “sushi omakase.” That being said, “people didn’t really request” the latter item because “they didn’t know what it was.” Still, Park “had a lot of regular customers” and eventually decided “to serve them omakase anyway.” Diners learned to desire the set menu of nigiri (with the “popularity of the 2011 documentary Jiro Dreams of Sushi” also playing a part), and they “began asking for more upscale selections.”

Park was “happy to oblige,” but, soon, Izakaya Yume “couldn’t keep up with the requests for those special items.” The chef had “always [been] thinking and dreaming that he wanted to open a very intimate sushi omakase restaurant,” and the form’s growing popularity among his customers finally convinced him to take the leap. In 2017, Izakaya Yume would transform into a food stall within the Niles location of H Mart. The following year, the Parks would open another location in the supermarket chain’s new Chicago location. All the while, they had started planning Omakase Yume (“yume” meaning “dream” in Japanese) with Calvin Pipping, a former customer of their izakaya turned business partner.

A Vancouver native, Pipping thought that Park “was doing something very, very special for where he was” and befriended the couple. He “convinced them that Chicago’s food scene was missing this” and that a full-fledged omakase could “fill a void.” Yume would not be a “fancy restaurant” but, rather, would be “meant for people to come and try new varieties of fish and seafood, like simply prepared uni and bonito” alongside “Korean flavors from time to time.” Just the same, the Parks wouldn’t “serve rolls” and scorned the “something for everyone” menu philosophy employed by Chicago’s sushi restaurants. Their experience would be “unapologetically about the fish,” flown in from “near where…[Sangtae] grew up” and utilized across “15 to 17 courses daily” (along with a selection of “extra pieces”). (Eventually, sourcing would comprise “some ingredients” from Spain, “a few” sourced locally, and “most”—including fish, “very high-end rice,” and garnishes—“from Japan.”) Additionally, the team had decided on an “intimate” eight-seat space so that the end product—“only fish and rice”—wouldn’t “have to wait in the time it could take a waiter to deliver an item to a table.”

Omakase Yume debuted on July 11th of 2018, and the immediate response was enthusiastic. Mike Sula, writing for the Chicago Reader that August, declared the restaurant “sets a new bar for Chicago” while praising “extraordinary moments in an extraordinary experience” comprising bites like fluke, a trio of tuna, golden-eye snapper, Ōra King salmon, bonito, and a range of supplements. Kate Park, in turn, was celebrated for “warmly” attending to the needs of the guests “on the opposite side of the bar.”

The Chicago Tribune would not have its say until February, with Phil Vettel awarding Yume two stars (“very good”) relative to Takeya’s one star (“good”) and Kyōten’s three (“excellent”) in an article evaluating three new omakase restaurants fueling the city’s “sushi boom.” The critic praised an “opening appetizer of octopus, monkfish liver and pickled vegetables,” “bold nigiri,” and “overdone” items that, nonetheless, are saved by “execution and flavor.” Compared to Kyōten, Yume offered “quality, complexity and innovation” for “almost half the price”—a formula, despite increases at both properties, that remains true today.

Nevertheless, the Parks earned their biggest honor in September of 2019, when Michelin announced Yume had earned a star in its forthcoming 2020 Guide. Bibendum praised the “small and clean dining enclave,” “graceful servers,” and dishes headlined by “top ingredients that are both smartly paired and well executed.” Overall, the meal was said to reflect “a thorough study in product sourcing, fresh flavors, and delectable textures,” and the restaurant would go on to retain that Michelin star is every subsequent edition of the Guide.

You visited Yume seven times during that opening year and found this praise to be well-deserved. At the time of opening, the Parks could undoubtedly claim the omakase crown with a space totally dedicated to the craft, charming service, a wide array of fish, and rotating extras. Kyōten’s opening complicated that argument as Otto Phan began to offer sushi of a singular style that never ceased evolving (though, admittedly, sacrificing elements of hospitality and comfort). This gulf widened over time as Kyōten looked to distinguish itself through more expensive ingredients (and a corresponding leap in price) while Yume (raising the cost of its menu at a lesser rate) remained a friendlier, more accessible, and more self-directed experience.

Thinking of the wider dining scene, you might also throw The Omakase Room at Sushi-san, with its high production value, and Jinsei Motto, with its more boisterous and boundary-pushing style, into the mix. There are also places like Mako and Sushi by Scratch Restaurants, both the products of absentee chefs, to consider. Ultimately, you find that every omakase in Chicago that does not have Kyōten in its title bastardizes one key element of the craft: their chefs make multiple pieces of nigiri at a time to the detriment of the rice’s texture and the fish’s temperature. It has always been hard for you to understand why they would devote themselves to a genre but compromise so fundamentally on quality—not in terms of ingredients (where one must choose which tier of pricing to occupy) but of technique.

Putting that aside, Yume ranks very favorably as one of the top two, top three, or top four omakases in Chicago depending on what aspects of the experience a guest most prizes. Though The Omakase Room may seem more luxurious on the surface, it also suffers a bit from that familiar LEYE sheen—one that, admittedly, serves to welcome diners who may never otherwise give this genre a chance. Yume, instead, shines on account of the chef’s earnestness and the close attention provided by his wife, a winning combination that imbues their counter with a great deal of heart. In this manner, Parks have built a place that largely feels true to tradition without being bound by it, a place that may still form the most effective entry point into omakase for the uninitiated.

With a Michelin star in tow, the Parks entered 2020 with an aim toward expansion. That February, news broke that the Yume team was planning a “casual izakaya-style tapas bar” next door to their omakase venue. However, compared to the eight-seat counter, the space would seat 65 with a focus on “small sharing plates and creating a very casual place to meet.” Just the same, the two restaurants would “operate as separate businesses” with Sangtae “helping to create the menu” but operating as “more of a consulting chef” so that he could continue to focus on his sushi. To that point, TenGoku—the name of the new venture (translating to “heaven”)—would emphasize “dishes cooked on a grill” with the “clean, high-heat coal” known as binchō-tan alongside salads, pickles, sashimi, and “Korean-style ramen.”

By the time TenGoku debuted in July of 2020 (about two years after Yume’s launch), the concept had appended the word “Aburiya” (translating to “grill”) to the end of its name. TenGoku Aburiya also entered a dining scene that, after the first flush of the pandemic, looked a great deal different. That “Korean-style ramen,” for example, had been excised in favor of a “heft, wheat-flour noodle” called udon. The restaurant was “expecting to do a lot more takeout in terms of lunch service,” and the former item wouldn’t “hold up well” since it was prone to getting soggy. Overall, the afternoon menu was characterized as “speed-focused,” yet dinner would retain its focus on grilled items like black cod misoyaki (a signature from the omakase), shishito peppers, chicken meatballs, pork belly, Korean-style short ribs, and beef tongue. Drinks would feature “sake, beer, wine, and cocktails such as Japanese highballs,” but the space would only be seating about 30 customers (due to city restrictions) at launch.

Though the restaurant’s opening was, due to the circumstances, a fairly quiet one, the Parks’ new concept was rather warmly received. You note a majority of positive impressions citing a “relaxing” environment, “very friendly” service, and “delicious” food. However, a smaller sect of negative reviews noted rushed pacing, small portions, sold out items, raw skewers, and a lack of flavor from the grilled fare. For what it’s worth, Adrian Kane—writing for The Infatuation’s “The Best Things We Ate This Week” feature in November of 2020—praised TenGoku for its “six-piece sashimi set” that was “not only delicious, but also under $20.”

As with Yume, the concept’s biggest piece of praise came from Bibendum. In April of 2021, Michelin awarded TenGoku its (now-defunct) “Plate” honor signifying “restaurants where the inspectors have discovered quality food.” More specifically, the tire company cited “evocative details” like “paper chandeliers” and “white noren hangings” that “instantly transport you back East.” Additionally, they noted “delicious and carefully prepared food” with “something for everyone,” including “octopus fritters with unagi-teriyaki sauce,” “assorted maki,” “heartwarming udon,” and “maze soba with ground pork, fish flakes, and egg.” Bibendum even featured TenGoku on its list of places “redefining Japanese cuisine in the Windy City” at the time though, at present, the concept has been removed from the Guide altogether.

Still, the Parks’ izakaya has proven its resilience over time. In February of 2022, Chicago magazine’s dining critic argued that while Omakase Yume is a “nice destination for a splurge,” the “under-the-radar spot” TenGoku actually represents the Parks’ “real gift to the dining scene.” Also praising head chef Keisuke Ito, the piece noted the restaurant’s “Japanese comfort food at lunch” and “a big menu with skewers” at dinner alongside an “extensive lineup of small plates” and “seriously good drinks.” The “perfect order” there was said to comprise a “fantastic kale-miso salad,” “Korean lollipop chicken wings,” batter-fried tofu in broth with fish flakes and mozzarella, a “face-steaming” seafood hot pot, and the “Platonic ideal of a vodka soda.”

In May of that same year, Crain’s Chicago Business would name TenGoku one of six “hot new restaurants” that are “perfect for a business lunch.” This time, a “delicate and flavorful” beef-and-vegetable gyoza earned acclaim along with “seven impeccable pieces of nigiri” (that were “fresh and satisfying”) and the “highlight”: a “luscious bowl” of “mixed noodles with ground pork, fish flakes, seaweed and green onion.” Online reviews, too, have generally stabilized: being pretty uniformly positive apart from a peppering of low ratings on the basis of service miscues and small portions. Your own experiences at the restaurant—a mere one or two visits separated by a long stretch of time—have been good if not quite memorable.

2023 would see the Parks form H I S hospitality—the name standing for “Happiness Is Success”—with Sangtae as co-founder/executive chef and Kate as co-founder/CEO. The company would serve as an umbrella for Izakaya Yume, Omakase Yume, and TenGoku Aburiya while fueling the team’s “passion for creating unique and unforgettable dining experiences” and penchant for “constantly pushing the boundaries of what is possible in the world of food.” You also like the framing that, “in a city where cutting edge molecular gastronomy has been at the forefront of the city’s food scene,” H I S is focused on “respecting…traditional cuisine and philosophy” with a bit of influence from the chef’s “Korean heritage” mixed in. Ultimately, the hospitality group seems to have primarily been formed in anticipation of opening a “new venture”: Bon Yeon, “the first beef omakase in Chicago.”

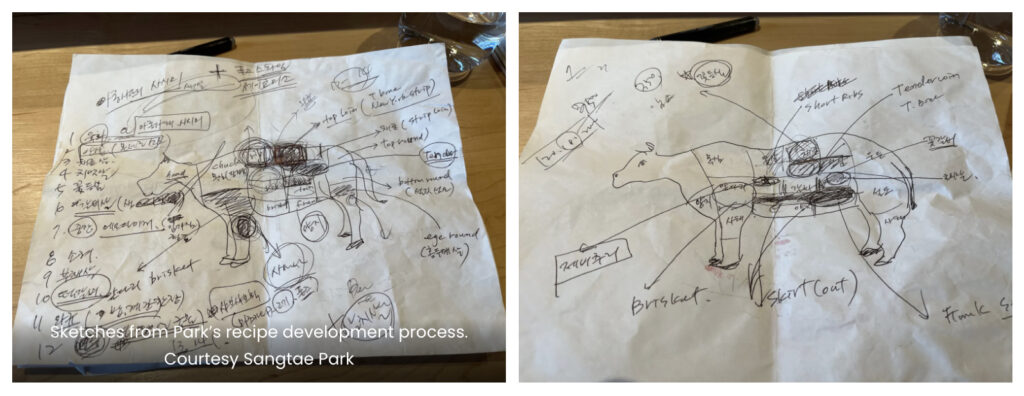

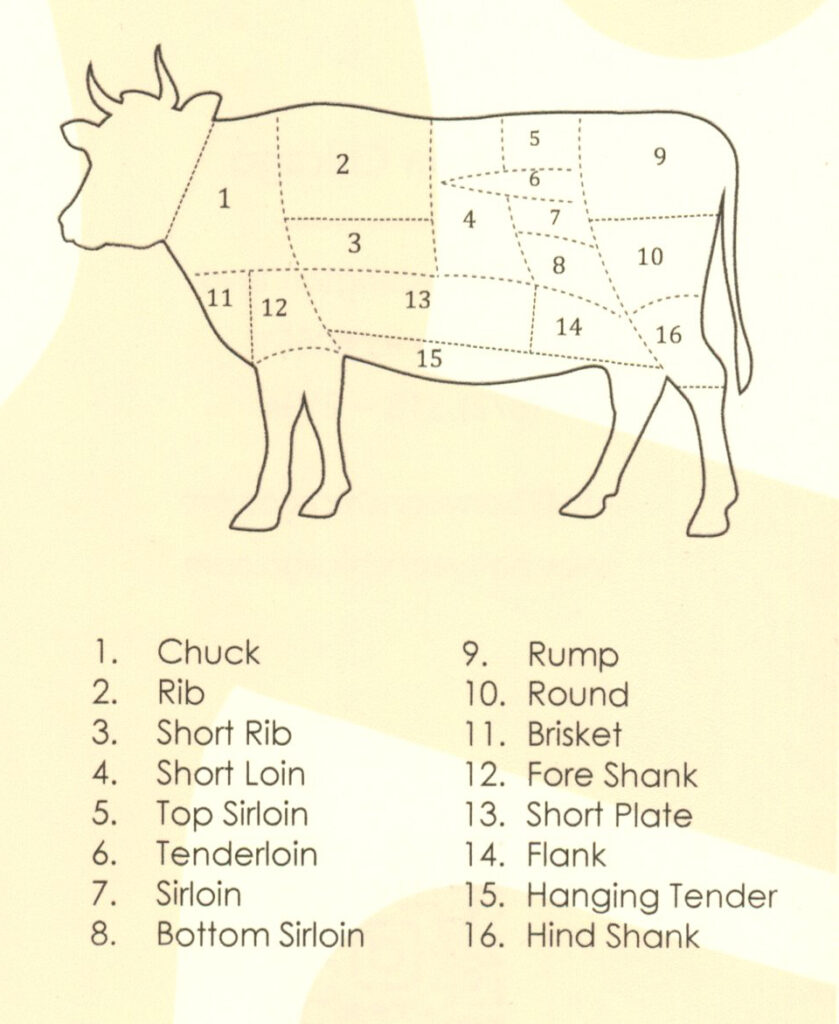

The first real details were shared by the Chicago Reader this past November via an evocatively titled piece: “At the upcoming Bonyeon, chef Sangtae Park will have a hundred tastes in his head.” This headline references a “centuries-old Korean expression of unknown authorship”—“one head with a hundred tastes”—that celebrates the “myriad ways to cut up and eat a cow.” This concept “also acts as the guiding principle behind Bonyeon [later rendered as Bon Yeon],” which would serve “a 12-course, all-beef omakase that combines a particularly Korean snout-to-tail aesthetic with Japanese technique.”

Speaking with Mike Sula, Kate would explain that Bon Yeon means “original, or root, or natural state”—maybe even being more close to the term “aboriginal.” To that point, just as Sangtae has sought to keep “the original flavor” of each fish utilized in his nigiri, he would look to accentuate the unique quality of “each cut” of beef served at his new restaurant. In fact, the chef had been “plotting to open a beef omakase almost as long as he’d been dreaming of Omakase Yume.” Despite “beef prices continuing to rise,” they decided to go ahead when a “space freed up with favorable terms from the landlord” at a location “right around the corner” from their other two concepts.

Nonetheless, the Hanwoo beef native to Korea—the kind you earlier likened to Japanese wagyu and that drives the beef omakase at Seoul’s Born and Bred—could not be sourced from the Parks’ purveyors: “it’s so extraordinarily expensive and rare that very little of it is exported.” Thus, Bon Yeon would make use of “American Wagyu, Japanese Kobe, and prime-grade Black Angus beef” while invoking a Korean tradition, developed when “all beef was uncommon and expensive,” of using “every last bit of the animal” from “obscured isolated muscles to bits of offal to skin and bones.”

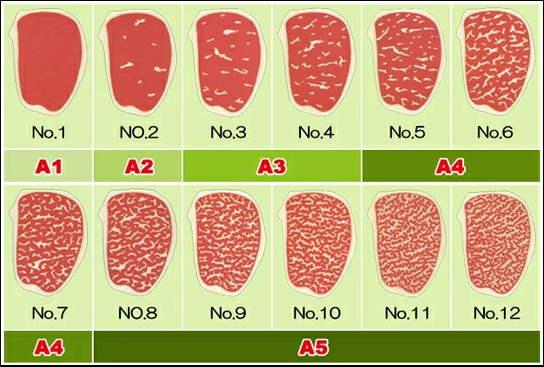

All the action would occur at a 12-seat “quartz bar inset with gas-powered grills blazing beneath Mount Fuji lava stones,” where diners “will sit across from Park and his cooks.” More specifically, guests could expect servings of “primal cuts…age[d] for up to 45 days in the dry-aging case set in the back of the dining room,” “Korean tartare minced from ribeye,” and “jerky made from pressed, fermented, and dried top round.” These would then be followed by “thin slices of beef from various breeds”—like “American Wagyu short rib,” “A5 Wagyu sirloin from Hokkaido,” and “A5 Wagyu ribeye cap from Kagoshima”—minimally seasoned so as to allow guests to “taste…the differences” between them.

Still, Park revealed he’d already “sketched out dozens of ideas for future courses” that would “introduce more obscure cuts and off bits that might be more challenging or unfamiliar to American diners” over time. These would include “omasum” (“the cow’s third compartment forestomach”), “neuggansal” (or “rib finger”), “pyeonyuk,” (“a sort of headcheese, pressed from thinly sliced top round, shank, knee cartilage, and tendon”), and a combination of “sous vide beef tongue with abalone.”

After a period of “friends and family seatings,” Bon Yeon would look to launch in early December with a price of “around $255 for the tasting” and “about $155 for the pairing,” which would include “sparkling, white, and red wines, along with sake, Japanese whiskey, and Hana Makgeolli [rice wine].”

(Of this piece, you only take issue with the claim that Bon Yeon is the “first dedicated all-beef tasting menu in the U.S.” You have already mentioned the “steak omakase” at COTE, which comes with items like “caviar-topped scallops,” “cold noodles,” and “puffy egg souffles,” and bōm, where beef plays a starring role but is joined by things like tuna, foie gras, caviar, scallop, king crab, and abalone. Though Bon Yeon’s menu may not have been finalized at the time the article was written, it does, in fact, include courses dedicated to ingredients like oyster, golden-eye snapper, amberjack, king crab, and scallop. So, it follows that none of these three concepts are “dedicated all-beef tasting menu[s]” or, otherwise, that COTE did it first and consumers must accept that these menus will typically contain non-meat courses. To be fair, merely being the first meal of its kind in Chicago is nothing to sneeze at!)

The Parks would formally open Bon Yeon on December 7th of 2023—right on time, impressively, though it was revealed then that the concept had actually “been in the works for a year and a half.” Now fully realized, the restaurant’s space was described by Kate as “slick” and “a little bit more fun” than Omakase Yume, with “upbeat music, a black and gold color palette, and an L-shaped counter where patrons can watch and chat with three chefs as they work.” Beef, likewise, was being sourced “domestically from small Midwestern farms” with the aforementioned Kobe becoming something they “would like to bring in” in the future. Still, the team would hope to “complement the distinctive qualities of each course with sides that bring out their best” but “never” cover them up—like “a little bit of sour pickle with salt and wasabi” used to accentuate “a fatty cut.”

The concept’s early online reviews have been overwhelmingly positive: “amazing,” “as good or even better than beef omakase we have tried back in Korea,” “[a] great place to celebrate a special occasion,” “absolutely delicious,” “the perfect place for a great experience,” “tasteful luxury,” “a true game changer,” and “an unparalleled gastronomic adventure that will linger in your memory.” In terms of dissent, you only note two diners who expressed that dietary restrictions were not remembered, two that found the meal overpriced, and one—dining on opening night—that criticized a lack of “engagement from the chef” and an “inability to do basic grilling of meats.”

On the professional front, Bon Yeon was the subject of Chicago magazine critic John Kessler’s “Kessler on Dining” column in early January. This “web-only” outlet forms a clever way for the writer, one you respect for his outsider perspective, to opine on restaurants without submitting to the rigors that a “proper” review and star rating demand. Therein, he note he would share his “perplexed impression of the restaurant” but with the “caveat[s]” that he’s “only been once,” the place “had been open not quite a month,” and that “the format may change a bit as feedback comes in.”

After praising the chefs’ “lively, friendly banter,” Kessler recalled the sensations of the meal as “all soft and gauzy,” expressed through “plush bites of beef punctuated by the briny slap of a Black Point oyster” or a “marinated Hokkaido scallop of excellent quality but served so cold it was robbed of flavor.” The critic “best liked a serving of ribeye topped with aromatic slices of black winter truffle and set over a sauce made from…fermented bean paste” along with “grill-kissed A5 Japanese Wagyu set over a quail egg yolk nesting in rice” and “cubes of short rib…paired simply with coarse smoked salt.” However, he did not find “any flavor differential between the various cuts of beef” and, barring that, would have liked “to get a sense of the relationship between meat and bone.” The wines served “in the $40 per glass range” also proved to be a bit of a sticking point, and, while the critic “didn’t feel overstuffed or assaulted by too much salt,” the meal left him “lacking.”

While, perhaps, a little lukewarm, Kessler’s capsule review did not prevent Bon Yeon from earning the third spot on Chicago magazine’s list of the “10 Hottest Restaurants in Chicago Right Now” at the end of January.

Which brings you to the present day and that all-important two-month mark: that magic moment when unrealized potential must meet the crushing weight of actuality. Do consumers, here and now, encounter a restaurant that really satisfies their carnivorous spirit—to say nothing of the intellectual or educational dimensions of the experience that were hinted at—or, after spending “$306 inclusive of service” but (“not factoring in tax or beverage”) per person, are they left, like that critic, running home to a bowl of rice?

You have visited Bon Yeon a total of three times, comprising meals in early December, early January, and early February. This span allows you to effectively track the restaurant’s growth since opening and, hopefully, to get sense of its long-term prospects. As usual, you will condense the sum of your experiences into one cohesive narrative.

With that said, let us begin.

After a stretch of time spent further afield, it feels heartening to be back in your neck of the woods. Of course, West Loop, with its steady stream of new high-rises, increasingly lacks the intimate, knowable quality that lends neighborhoods their charm. Randolph’s “Restaurant Row,” likewise, has welcomed bigger, more crowd-pleasing concepts. It has welcomed chains—not just restaurants, but clothing and cosmetic retailers—and a couple dispensaries for good measure too.

Though this all makes for a certain suffocating sameness when walking down one of the more commercialized blocks, the area is now better equipped to please a burgeoning population. It is ready to host visitors as something more than a trendy dining district. And, surely, the most precious of Chicago’s gastronomic gems can still be found among the clutter. In fact, an outsized portion of the culinary scene’s creative firepower is located on a solitary stretch of Ada Street (that is, the one south of Lake).

Faced with the temptation to declare that the West Loop is now “over”—that the renegade spirit that made it a destination has migrated northward or southward—you feel surprisingly untroubled. Yes, the thrill of tasting a novel, nimble menu from a chef unburdened by the pressures of large-scale investment leads you to venture elsewhere. But the heavy hitters, along with a couple classics in the making, remain. The establishments worthy of the most special occasions shine just as brightly. There has always been plenty of comparable crap to wade through in order to find them. Plus, any place you can walk to (or is it stumble home from?) will always benefit from that uniquely cozy sensation of seeming “right around the corner.”

Bon Yeon enters this maturing market with the assurance that a “beef omakase” will prove a tempting draw amid a sea of steakhouses. You find El Che, Gibsons Italia, Nisos Prime, BLVD, Fioretta, and Swift & Sons all in the vicinity along with places like Formento’s, The Publican, The Oakville, Trivoli Tavern, and many more that put out at least one cut of beef capable of sating a carnivorous craving. To be fair, nothing stops this demographic from going over to Bavette’s, Bazaar Meat, the RPMs, or Rush Street’s famed bovine sanctums should the mood strike to seek out the very “best.” So, it follows that the Parks are not slinging steak on their own isolated block so much as they are selling the kind of sizzle that makes meat eaters travel. Yume, after all, has always applied the same approach to raw fish and rice while TenGoku Aburiya, in turn, forms the place you can walk into for a casual lunch or dinner.

These two concepts, now joined by Bon Yeon, form what Kessler called “Sangtae and Kate Park’s West Loop complex.” The trio of restaurants, you must agree, occupy a world of their own within a larger property titled Washington Square, which transformed the former Hooker Paint Company factory into a six-story loft building. The Parks have built their empire at ground level in the shorter, original structure that borders Desplaines Street. The floor above them acts as a parking garage for office tenants (located in the larger connected space) that include Otis Elevator Company. Yume abuts this driveway on one side with TenGoku Aburiya, located on the other, wrapping around the corner and Bon Yeon situated just one door down.

Technically located in that West Loop Gate corridor, the Parks’ complex is primely located within a block or two of “Restaurant Row” (depending on where exactly you place its starting point) and another two of Ogilvie. Still, the restaurants’ immediate surroundings almost seem desolate: a parking lot, a freeway, a hulking apartment building (with a dental implant anchor), an electrical substation, and the monolithic Harold Washington Social Security Center. If you’re lucky, you may catch the McLaren dealership unloading its cars up the street. Otherwise, it can be easy to forget that Sepia, avec, Kumiko, and Au Cheval are only a few hundred yards away.

As it happens, that suits Bon Yeon—as it did Yume—just fine. In this understated environment, framed by columns of stone and brick that are set between glass inserts, you find a black awning. It announces the name of the restaurant but reveals little more. Windows, though smartly trimmed with wood, are mirrored and, thus, totally opaque. They reflect the pervading sparseness back at you, and the awning, if you didn’t know any better, could lead anywhere: a luxe spa, a design firm, a fancy clothier, a spiritual center, or an art gallery. (Perhaps this has something to do with Bon Yeon’s slick, concentric logo, whose symbols seem to reference the hanja used to write the word in Korean.)

Stepping through the threshold, you meet another door that, with one final tug, leads into the restaurant. Immediately, the coldness of the surrounding block fades as you adjust to the omakase’s comfortable confines. The palette is, undeniably, still cool: comprising tones of black, gray, and blue with textures of dark wood and metal. Yet the lighting is soothingly warm—moody (that is, astutely shadowed) in just the right spots—and trained on all the key details: two velvet armchairs, a white marbled side table, bright red flowers, and art.

Yes, the Parks have commissioned Detroit-based visual artist Mike Han, born to Korean immigrants and a proud member of “a noble Korean family (yangban) with royal ancestry,” to add character throughout the space. In the front room, that takes the form of one painting (perched over the armchairs) and a set of two circular engravings hung, above a black dresser, on a different wall. The former features squiggly black brushstrokes on a white, misshapen canvas. The latter comprise a smaller (more textured) and a larger (more smooth) pair of pieces with the same kind of squiggles rendered on (or in) gold. These works reflect what Han describes as “Modern Vandalism”: “the mindful act of destroying materials, objects, and/or space in an effort to create value.” To you, they seem like a jagged, less intricate take on Keith Haring. Nonetheless, the pieces do prevent the room from seeming too slick or soulless. They also speak to a fundamental degree of craft that surpasses what you have seen covering the walls of other restaurants as of late.

Of the details in this receiving area, you also like a set of wine fridges—temptingly displaying the assortment of labels selected to pair with the beef—and a neighboring cubby used to hang guests’ coats. Curtains, too, serve to separate the space from the dining room. They communicate luxury, mystery, and some sense of the showmanship to come. Taken in total, the combined elements make for an attractive, engrossing entrance that reflects a clear evolution—and refinement—of what the Parks have offered at their neighboring properties.

More importantly, the welcome you receive, upon setting foot through the door, imbues the striking setting (the sort that can, as always, simply be bought) with a leavening warmth. Sangtae and Kate have now returned to Yume, meaning that the latter’s deference and watchful eye—on full display during Bon Yeon’s opening period—no longer drives service firsthand. Luckily, the Parks have brought in a ringer to help manage things in their stead. He comes by way of New York City’s HAND Hospitality, progenitor of concepts like Atoboy, Atomix, Jua, and Lysée. And he reminds you, immediately, what that market (even compared to Chicago’s high standard) delivers in spades: precision, poise, and powers of anticipation that make you feel perfectly cared for.

Guided by this kind of leadership, the rest of the front-of-house team clearly excels. Interactions with them show the same smoothness and are further enriched, during the meal, by the staff’s coordination. Each movement—like pouring a drink or placing a utensil—benefits from the confident little frills of practiced motion. Facing the counter, service whirs quietly behind you, always ready to pounce but only ever announcing itself with the most pleasing of whispers. Quite simply, the hospitality offered is grade A, close to faultless, and only compromises (in that key emotional dimension) due to the fact that the servers act more as supreme stagehands than intimate guides. To that point, it should be noted that the back of house, in its own right, may actually do more to shape the guest experience (more on that later) and that the manager you so highly praise is destined to return out east after the restaurant’s opening period concludes—upon which, the staff’s training will really be put to the test.

Having been kindly greeted and relieved of your belongings, you are led into the nerve center of the operation: the open kitchen / counter setup that actualizes the “beef omakase” concept. There, you note a certain aesthetic continuity exemplified by the black wallpaper, gray flooring, and blue velvet. A set of dry-aging cabinets, installed on the back wall, seem to mirror the gleaming metal of the wine fridges. Four gilded grills, positioned at a various points along the counter, also call Han’s hanging golden engravings to mind. Of course, the artist can also take pride in another, more monumental canvas hanging in one of the corners. In an inversion of the painting near the entrance, the work features white squiggles (smooth, in this case, with less texture from the brush) on a solid black background. Cast in warm lighting, it also seems to glow a golden hue.

Still, insofar as the dining room is enriched by these synergistic elements, it really shines by elaborating what can only be faintly sensed when you first enter the restaurant. You think of the bi-level counter itself: a light gray, almost bluish tone of quartz enlivened by veins of white, brown, and gold that totally subvert the cold, dead wood that so often signifies the omakase form. Yes, more rarefied bars made of Japanese cypress—perhaps even one single, solid piece—do exist. Also, the prospect of molten fat sputtering from the grill and soaking into a porous surface probably did something to guide the choice of material.

But Bon Yeon’s counter, accented by cutting boards, bowls, trays, trinkets, flowers, and an arsenal of tools, feels like a proper stage. It is not the sort, within the sushi genre, that demands quiet prostration before a stoic master. Rather, the surface frames a more contemporary expression of craft: every bit as focused but also friendly, familiar, and more fitting with what a Western audience may think of as refined. The lighting, as in the front room, has a decisive influence. It ensures all the workings of the counter—and that tantalizing gradient of red meat, white fat, and browned crust—can be seen in high definition without seeming sterile. Darkened appropriately, the lighting also masterfully illuminates the open kitchen: the aforementioned dry-aging cabinets, several rows of whisky bottles, and a central staging area containing plates, pans, and a separate konro grill. This is the “backstage,” so to speak, and it allows for a holistic view of the action without ever taking away from the main event.

When you factor in other details like the glassware (and coasters), chopsticks (and holders), napkins, purse hooks, and menus (also designed by Han), Bon Yeon’s design is a rousing success. The Parks have built a space that, with its grills, fulfills the practical requirements of a “beef omakase.” However, they have not leaned solely on this element’s novelty appeal. Rather, they have wrapped function with a beautiful, shining sense of form—materials, lighting, comfort, and glimpses of personality—that you think rivals any other kind of counter in the city. No doubt, signaling “luxury” can act as something of a bait-and-switch, but you sense restraint (rather than gaudiness) here. Arguably, the restaurant looks sleeker and more cohesive than what LEYE built at The Omakase Room—quite a compliment when you consider the resources that behemoth of a hospitality group has at its disposal. And the environment even gives NYC’s Michelin-starred bōm, which you have mentioned several times as something of a kindred concept, a run for its money.

Taking your place at the counter, a server provides you with a warm hand towel and asks about preference of water. Getting your bearings, you make a quick scan of the room: four cooks in the kitchen, three members of the front-of-house team buzzing behind you, and a fairly diverse cadre of other diners. You note two older white couples—men dressed in suits, one clutching a fancy camera—on a double date. You have also been joined by a share of 20- and 30-something black, white, and Asian couples, more casually dressed, across your visits. After all, most everyone enjoys beef and may see, in this intimate style of dining, a shining romantic occasion. (You think of certain picky partners who might never touch a piece of sushi but, with this example of omakase, can finally get excited about the form.) Just the same, you have observed mother-daughter groupings and businessmen having a great time here too.

In short order, the server returns clutching that most precious of books—the beverage list—and places it before you. They do not simply leave you to uncover its wares but, with a palpable degree of panache, celebrate the sparkling, white, red, Old World, New World, and sake options that await you. Though not substituting for being guided to a particular choice (something you think the staff is capable of and will, moreso, be able to do once hiring a dedicated sommelier), this introduction is whimsical. It works to calm the fear that being faced with such a menu can sometimes entail while, at the same time, ensuring the mood in the dining room remains light and a little theatric.

To be fair, there is really no need to take in all the options if you go for one of two turnkey solutions: the “Standard” ($155) and “Reserve” ($200) wine pairings that headline the list. Of these, you sampled the latter, which comprised the following eight pours:

- NV Bollinger “Special Cuvée” Brut Champagne

- Kojimaya “Untitled” Cedar Barrel Aged Sake

- 2021 Lonesome Rock “The Estate” Pinot Noir Willamette Valley

- 2021 Sigalas Assyrtiko Santorini

- 2019 E. Guigal “Saintes Pierres de Nalys” Châteauneuf-du-Pape

- 2008 Chateau Montelena “Estate” Cabernet Sauvignon Calistoga

- Mantensei “Kinoko” Junmai Ginjo

- 2022 Vietti Moscato d’Asti

Spread across a total of 13 courses (some of which comprise two distinct dishes), many of these wines and sakes pull double duty. However, the pours are generous enough to get a couple good sips in with each respective plate, and you have found that the staff will top your glass off if you inadvertently finish a pairing before receiving all its corresponding bites. (You note one customer review claiming they were charged for extra servings and can only speak to having a single glass partially refilled.)

The chosen bottles boast name recognition—Bollinger, Guigal, Montelena—and span popular categories like domestic Pinot Noir, Rhône, and Napa Cab—the kind that come to mind when tucking into a piece of meat. There are certainly some value choices like the Assyrtiko (served with a duo of seafood) and the Moscato d’Asti (served with dessert). And the sakes, one cedar barrel aged and the other aged in tank for three years, are quite characterful too. Though Bon Yeon, you have already mentioned, does not yet have a dedicated sommelier, the servers do a good job of sharing a bit of background information on the pairings even if the technical explanations do not quite rise to the level of being educational.

Overall, you think guests prepared to spend $310 or $400 on pairings (ordering two of either option) would be better served putting that money toward one or even two bottles of their choice from the full list. A single diner or lone member of a party looking for variety above all else may, nonetheless, find some utility here. It is true that the Chateau Montelena is not offered on the bottle list (where it would represent the most aged selection), but you do not think the interplay between any one course and its chosen pour is particularly memorable. Rather, the pairings are simply pleasant, and anyone who really knows what they like would benefit by going straight for it.

You feel the same way about the by-the-glass selection:

- NV Bollinger “Special Cuvée” Brut Champagne ($43)

- 2018 J. Moreau & Fils Chablis “Vaillons” 1er Cru ($40)

- 2021 Sigalas Assyrtiko Santorini ($48)

- 2021 Ponzi “Laurelwood District” Pinot Noir Willamette Valley ($30)

- 2019 E. Guigal “Saintes Pierres de Nalys” Châteauneuf-du-Pape ($45)

- 2014 Margaux du Château Margaux ($58)

Several of these selections are drawn from the “Reserve” pairing (and you wonder which of the remainder might have appeared on the “Standard”). There is nothing inherently wrong with that. However, charging $48 for a glass of Assyrtiko that costs $47.99 a bottle at retail is hard to stomach if you know the score. The same goes for a $30 glass of Pinot Noir that retails for $39.99. You do see some appeal in maybe getting a lone glass of Champagne or, say, a pour of that third wine from a legendary Bordeaux First Growth. However, anyone who finds themselves desiring two glasses of wine from this list should really just bite the bullet and spend a little more on an actual bottle.

The pricing here (as Kessler noted in his column) is just a bit too shameless in trying to squeeze those customers who want to drink a bit more modestly—the kind of customer who would have no problem resorting to beer or something non-alcoholic if need be (where you are sure a certain healthy margin remains but is just less obvious or painful). Even as someone inclined to purchase bottles, you do not like the message this sends. A good beverage program presents wine as something to be shared and celebrated. It should not be reduced to a pricey bauble one feels compelled to order out of a fear they won’t be able to fully appreciate the beef. There must be a better middle ground that can be reached here: one where the restaurant still minimizes wastage but, simultaneously, offer a degree of value that makes ordering two or three of these glasses more justifiable. Doing so, you think, would enrich the social dimension of the omakase as well.

Beyond the pairings and the by-the-glass, you find a range of some half-dozen Japanese beers (three from a Gunma-based brewer named Kawaba, three from a Yamanashi-based brewer named Far Yeast) spanning a range of styles. Two from the latter producer (titled “Kagua Blanc” and “Kagua Rouge”) are, interestingly enough, made in Belgium but utilize yuzu and sansho as flavoring respectively. Priced at $21 (for 330 mL), they may form an interesting substitute for those not inclined toward wine.

The same may be said of the sake, which in no way should be judged as inferior to pleasures of the vine. Rather, four of these six bottles are priced under $100 (as opposed to just eight of 36 wines on offer), and the comparable paucity of choice may seem more palatable to those who find parsing a sea of appellations, grapes, and vintages nauseating. Admittedly, the team “tasted a TON” of sakes in order to pick the half-dozen offered. They mostly comprise bottles made in the clean, bright Junmai Ginjo style (rice polished down to at least 60% without the addition of any distilled alcohol). However, you also find two options in the richer, alcohol-added Tokubetsu Junmai style (one that is easy to imagine paired with beef) and one—albeit mislabeled—in the elegant Junmai Daiginjo style (where rice is polished down to at least 50%, with no alcohol added).

When it comes to pricing the sake (a category where consumers, due to inexperience, can easily be led astray), Bon Yeon maintains markups that range from 128% of the retail price to 184% of the retail price. When you consider the average markup is 153%, this seems rather fair!

Moving on, you find the non-alcoholic options. These include the ever-popular sparkling juices from Kimino, available in all four flavors: yuzu, mikan (a mandarin-pomelo hybrid), ringo (a kind of Fuji apple), and ume (or plum). There is also sparkling water (from Saratoga) and a trio of green teas on offer: one plain, one spiked with yuzu, and one—that is shade-grown—displaying a heightened degree of umami. You sampled the latter ($15 for two steepings) and found it to be both smartly presented and well matched to the food.

Next, you come to the whiskeys, a category you might instead refer to as “whiskies” considering the Korean, Japanese, and Scotch selections are incorrectly headed with the “key” rather than “ky” spelling. (The Irish tipples, as American ones would be if they were featured, are correctly categorized as “whiskey.”) The three Korean pours, each under the Ki One label, are made in the single malt style and come from the Three Societies Distillery in Namyangju. A half-dozen Japanese options come from esteemed producers like Chichibu, Mars, Nikka, and Yamazaki. The three bottles of Scotch come from the Speyside (fruity, unpeated), Highland (full, smoky), and Islay (pungently peaty) regions—a representative assortment. Finally, the two Irish picks come from Teeling (a single malt) and Redbreast. Pricing, compared to steakhouses in the area like Bavette’s and Gibsons Italia, is rather fair (being a bit higher in some cases, a bit lower in others, but generally in the same ballpark). Thus, this category represents a good value for those brave souls who like a bit of liquor with their beef.

Finally, you reach the bottles of wine: seven Champagnes, six whites, and 23 reds (split across “France,” “Rest of the World,” and “California” headings). Prices range from $75 (for a Cypriot Cabernet Franc) to $637 (for a Cult Cab made from a vineyard recently sold to Realm), with an average price of $218.50 and a median of $152.

Of the selections, these stand out:

Champagne

- NV Canard-Duchêne “Cuvée Léonie” Brut ($116)

- NV Michel-Arnould “Réserve” Grand Cru Brut ($123)

- NV André Clouet “No.3” Grand Cru Brut Rosé ($140)

- NV Drappier “Carte d’Or” Brut ($161)

- NV Pierre Peters “Cuvée de Reserve” Grand Cru Brut ($175)

- 2013 Dom Pérignon Brut ($480)

White

- 2022 Massican “Annia” California ($81)

- 2021 Sequoia Grove Chardonnay Napa Valley ($84)

- 2022 Alphonse Mellot Sancerre “La Moussière” ($105)

- 2021 Vincent Pinard Sancerre “Florès” ($130)

- 2021 Samuel Billaud Chablis ($137)

Red

- 2020 Joseph Drouhin Côte de Beaune-Villages ($91)

- 2017 Rhys Pinot Noir Santa Cruz Mountains ($95)

- 2011 Château Canon Chaigneau, Lalande-de-Pomerol ($98)

- 2020 Domaine Raspail-Ay Gigondas ($116)

- 2019 Château du Glana “Pavillon du Glana” Saint-Julien ($123)

- 2019 Château le Puy “Emilien” ($145)

- 2017 Parusso, Barolo “Perarmando” ($159)

- 2019 Allegrini Amarone della Valpolicella Classico ($200)

- 2017 Quilt “Reserve” Cabernet Sauvignon Napa Valley ($210)

- 2017 Domaine Follin-Arbelet, Aloxe-Corton “Clos du Chapitre” 1er Cru ($263)

- 2020 Duckhorn Vineyards “Three Palms Vineyard” Merlot Napa Valley ($305)

- 2013 Dana Estates “VASO” Cabernet Sauvignon Napa Valley ($350)

- 2014 Dana Estates “VASO” Cabernet Sauvignon Napa Valley ($350)

- 2015 Dana Estates “VASO” Cabernet Sauvignon Napa Valley ($350)

- 2019 Beaulieu Vineyard “Georges de Latour Private Reserve” Napa Valley ($385)

- 2011 Ramey Cabernet Sauvignon Napa Valley ($490)

- 2014 Ramey, Cabernet Sauvignon Napa Valley ($490)

Starting with the Champagne, you find the options presented to be rather approachable. Yes, you might not find sparklers from other regions that land below the $100 mark. However, Canard-Duchêne and Michel Arnould form respectable entry points while André Clouet, Drappier, and Pierre Peters are all worth the associated gradations in price. Of course, Dom Pérignon is also standing by for those who really wish to splurge.

The whites, likewise, are short and just as sweet. Massican’s “Annia” (a blend of Ribolla Gialla, Friulano, and Chardonnay) is a reliable value play while Sequoia Grove’s Chardonnay is sure to please those who enjoy a riper, New World style of the grape. The focus on Sancerre seems strange until you reflect on the region’s popularity and Sauvignon Blanc’s ability (due to a combination of acid, fruit, and aromatic complexity) to hold up to grilled meat—especially the smaller, more refined preparations on offer here. If anything, you might like the white Burgundy category to expand beyond crisp, cleansing Chablis to include richer, oakier styles that somewhat imitate the Sequoia Grove but demonstrate greater depth and finesse. White Rhône blends, though a bit more obscure, could also match oilier, fattier cuts. Likewise, orange wines and more premium examples of rosé could offer guests a bit of tannin without requiring them to go all the way into an actual red.

On that point, the red wines you have listed in the $91-$159 range are quite nice: comprising entry-level Burgundy, entry-level domestic Pinot Noir, entry-level Bordeaux, entry-level Rhône and some nice, approachable bottles from Château le Puy and Parusso that justify the price. Some of these options even benefit from a bit of age, which is a very nice surprise. Heading into (and beyond) the $200 range, you find a big, benchmark Amarone and a more premium red Burgundy that, having tried it, you found fairly expressive. It also had the stuffing to match meat, which naturally explains Bon Yeon’s focus on the wines of Napa Valley. Names like Quilt, Duckhorn, Beaulieu, and Ramey will be familiar to many drinkers. It is also nice to see the latter offered with a bit of age. Dana Estates might not be quite as well-known; however, their “VASO” offers a friendlier way to experience the brand (whose single-vineyard offerings can cost anywhere from $500-$1,000 at retail). In a nod to the Parks’ heritage, the boutique winery was also founded by Hi Sang Lee, a South Korean businessman, in 2005.

Though you do sense obvious value in some of the more affordable bottles being offered, it may be instructive to take a look at the markups being applied across the board:

- 2022 Massican “Annia” California ($81 on the list; $34 national retail average)

- NV Canard-Duchêne “Cuvée Léonie” Brut ($116 on the list; $44.99 at local retail)

- 2021 Vincent Pinard Sancerre “Florès” ($130 on the list; $41.99 at local retail)

- 2021 Samuel Billaud Chablis ($137 on the list; $41.99 at national retail)

- 2019 Château le Puy “Emilien” ($145 on the list; $56 national retail average)

- 2017 Parusso, Barolo “Perarmando” ($159 on the list; $58 national retail average)

- NV Drappier “Carte d’Or” Brut ($161 on the list; $43.95 at local retail)

- NV Pierre Peters “Cuvée de Reserve” Grand Cru Brut ($175 on the list; $59.96 at local retail)

- 2019 Allegrini Amarone della Valpolicella Classico ($200 on the list; $79.99 at local retail)

- 2017 Quilt “Reserve” Cabernet Sauvignon Napa Valley ($210 on the list; $106 national retail average)

- 2017 Domaine Follin-Arbelet, Aloxe-Corton “Clos du Chapitre” 1er Cru ($263 on the list; $101 national retail average)

- 2020 Duckhorn Vineyards “Three Palms Vineyard” Merlot Napa Valley ($305 on the list; $114 at local retail)

- 2013 Dana Estates “VASO” Cabernet Sauvignon Napa Valley ($350 on the list; $95 national retail average)

- 2019 Beaulieu Vineyard “Georges de Latour Private Reserve” Napa Valley ($385 on the list; $147.99 at local retail)

- 2013 Dom Pérignon Brut ($480 on the list; $229.99 at local retail)

- 2011 Ramey Cabernet Sauvignon Napa Valley ($490 on the list; $79.99 at national retail)

Based on this selection (one that is meant to represent a range of price points drawn from the producers you most readily recognize), the markups on Bon Yeon’s bottle list range from a mere 98% (for the Quilt) to a staggering 513% (for the Ramey). You also note lower markups for the Dom Pérignon (109%), Massican (138%), and Allegrini (150%) while the Dana Estates (268%), Drappier (266%), and Samuel Billaud (226%) also rank on the higher end. Overall, the bottles you have sampled show an average markup of 175% with a median of 164%.

While slightly higher than the average you calculated for the sake (153%), this number is not beyond the pale. Rather, it is the kind of premium you expect to pay at restaurants that do not consciously pride themselves on delivering value to oenophiles, and that is totally fair. This “beef omakase” may ultimately be a one-time splurge for many customers, and it makes strategic sense to have them pay a bit more for the bottle they really want. Selling it to them at a more appealing price may, to be fair, cultivate some degree of loyalty. However, compared to dining at a conventional steakhouse concept (with all its repeatability), is it likely that such a guest would come running back to an entire “experience” if they are really the sort who just wants food and low-markup wine?

The answer is no, for Bon Yeon is just not the kind of place you can drop into. The Parks are selling the kind of meal you hear about, dream about, schedule, and eventually come to check out firsthand. With a price barrier of $255 per person, the steak will either blow you away—and make you want to come back at some point—or be good, fair, fine (and forgettable) regardless of whether you saved 50% on wine.

This system may help explain why the restaurant’s verticals of aged Napa Cab—the 2013/2014/2015 Dana Estates “VASO” and 2011/2014 Ramey—are offered at such high markups. Sourcing might have something to do with it (assuming these are library releases), but it would be strange for both domaines to price the bottles so exorbitantly. Rather, possessing some degree of age, these wines represent the crown jewels of the list. They stand as the ultimate splurges for that truly exceptional one-time diner who will only drink the best with their omakase of beef. And Bon Yeon, relying on this logic, knows it is worth keeping the bottles on the list at this higher pricing (even if they stay there for quite a while) because someone, at some point, will bite.

You shudder at the thought of spending $350 or $490 for those wines but cannot fault the maneuver. Especially since, in bottles like the Massican, le Puy, Parusso, Pierre Peters, and Follin-Arbelet, you do find an acceptable degree of value. They may, at times, approach triple their retail pricing but, just the same, offer a level of quality that helps you stomach the exchange.

What you do have trouble accepting is Bon Yeon’s quoted corkage fee of $90. This is not quite the highest of its kind in Chicago, as Smyth now charges $100 (one bottle per every two guests) for the pleasure. However, Louis Fabbrini’s pairings and list at the three-Michelin-star concept demonstrate exceptional creativity and value. The restaurant should (or at least has earned the right to), in good faith, nudge diners toward choosing something he has curated—transforming the corkage fee from an avenue a customer may use solely to save money into the kind of tax that ensures only true “collectibles” make the cut.

At Bon Yeon, the thinking must be the same: the restaurant would definitely prefer guests order a pairing, a bottle of wine, or a pricey by-the-glass pour. In turn, corkage, at $90 (right around the cost of the cheapest bottles), can only be justified for something special. However, guests looking to save money can easily divert their spending toward beer, juice, or tea. And, while the bottle list has some decent choices, a wine lover would likely raise their eyebrow at much of what they see. Frankly, after ordering the Pierre Peters and Follin-Arbelet on your first visit and sampling the “Reserve” pairing on your third, the remaining options hold little appeal. Thus, a $90 corkage now means paying a premium to bring any wine you’d actually want to drink rather than protecting the restaurant—and an appealing, acceptably priced list—from cheapskates. A lack of any dedicated sommelier (that is, a friendly face verbalizing the philosophy behind the list) only complicates this further.

You would like to see Bon Yeon change the corkage fee to $50: a number that still feels high but makes the prospect of bringing two bottles to dinner feel more conceivable. At this point, even $75 would seem like a compromise, for that $90 figure only really communicates the degree to which the restaurant expects to profit off of a fairly immature beverage program. It sends that message to a demographic of consumers (i.e., winos) who will notice and resent the lack of value they find upon browsing the in-house options. Biting the bullet, these diners will demand more from the pairing than it may be able to deliver and, likewise, expect perfection from the food.

Surmounting this pressure is not an impossible task. It may represent the exact trade-off that the team is comfortable with (and that funds, for example, a certain level of staffing). However, the beverage program at Bon Yeon is not a clear strength. Instead, it is something you must tangle with—study just a bit—in order to discern what form of overpaying (or abstention) is most worth it. By demanding a degree of sacrifice rather than really fueling celebration, this approach, once again, tarnishes the social dimension that makes omakase dining so unique.

With your drink order settled, all that’s left is for the show to begin. This moment is heralded gently enough, with one of the two grill chefs (Dennis or Josh) stepping out from the shadows to welcome the assembled diners. There, they had been quietly toiling away alongside two cooks (who, for the duration of the meal, play more of a supporting role in the rear of kitchen). Now, they prepare to take center stage as the servers, so personable up until this point, recede into the background: orchestrating, anticipating, but never interrupting or imposing themselves on a performance that clearly has only two stars.

In truth, the chefs’ introduction is a bit truncated. It amounts to something like the “coming attractions”—a small preview, a formality, before the feature film. Dinner actually begins with an opening movement of raw (and cured) morsels, and the real magic—the hiss of the grill, the sizzle of succulent beef—is still a couple courses away. That portion of the menu, the heart of the omakase (and the restaurant’s raison d’être), receives its own tantalizing spiel when the time comes. For now, instead, you are left with little more than a fleeting greeting.

In gustatory terms, that takes the form of the menu’s first offering: “Yukhue + Yukpo.” The former word translates to “raw meat” but, colloquially, refers to a tartare made from marinated cuts of lean beef. At Bon Yeon, it comprises a neat cylinder of finely chopped flesh perched on a golden spoon with a crowning dollop of caviar and a sprinkle of gold leaf. Positioned, just behind the “Yukhue,” on the same bed of pebbles, you find the “Yukpo.” This latter word means “dried meat or fish” but is also understood as referring to beef (i.e., the “default meat” in Korean cuisine). In practice, the dish is essentially a kind of jerky and takes the form of a shining, well-marbled strip.

On entry, the “Yukhue” caresses the palate, its fine cubes of beef unravel on the tongue, and the slick coating of meat quickly melts. Despite this prevailing tenderness, you have trouble sensing the presence (or pop) of the caviar. The gold leaf, too, only represents a visual conceit. However, you find the tartare offers a mild degree of umami balanced by a pleasing sweetness. The flavor of the sturgeon roe, like its texture, is missing. Some greater trace of those nutty, briny notes might provide more intrigue. But the “Yukhue” is a good—albeit simple—opening bite that sets the tone for the omakase, signaling the quality of the meat and kind of refined preparations that await guests.

The ”Yukpo,” by comparison, is decidedly more rustic. Rather than melting, it chews—like any jerky should—but sometimes just a bit too much. At its best, the dried meat is satisfyingly bouncy and only faintly beefy with some of that same appealing sweetness you noted in the tartare. Nonetheless, you have encountered examples that are cut too thick and totally lacking in flavor: a clear fit for that dreaded “shoe leather” descriptor. Certainly, the “Yukpo” is executed competently more often than not. However, it suffers in comparison to the tender “Yukhue” and really needs to offer more depth and concentration of beef flavor in order to justify the inclusion of the form.

Following this first flush of meat, you come to the second opening course: a cleansing interlude composed of seafood. That comprises a solitary oyster, sourced from New Zealand’s Coromandel Peninsula, served alongside two slices of sashimi.

You will start with the bivalve, which arrives dressed simply enough. The oyster is layered with ponzu, chives, yuzu pearls, and an edible flower. It feels meaty and amply moistened on the tongue but, on two occasions, has been blemished by fragments of shell. In terms of flavor, the dish is bland at best and tastes strangely fishy—almost dirty—in the worst instances. Given that Yume has, to your knowledge, served oysters before, it is hard to know what is going on here. One can easily blame a lapse in technique for the bits of shell (given that Park himself is not handling the product), but you would also argue that no bivalve worth serving needs to be obscured by so many garnishes. They signal an ingredient that cannot stand alone, an idea that stands diametrically opposed to the oyster’s pure, idealized image. Ironically enough, the Coromandel was not even helped all that much by its dressing, so, perhaps, sourcing is to blame?

Thankfully, the oyster’s accompanying serving of sashimi has, on all three occasions, represented a clear success. The restaurant has continually showcased two pieces—kinmedai (golden-eye snapper) and kanpachi (greater amberjack)—that both fall into the white-fleshed fish category. As much as you would love a cut of fatty tuna from next door, the selection makes sense: the idea here is not to compete with the beef to come but, rather, to prime the palate for escalating degrees of umami. In that task, the fish perform admirably. Dabbed with fresh wasabi and dipped in an accompanying saucer of soy sauce, the golden-eye snapper is firm, with good presence on the tongue, yet quickly proves tender with a mild flavor accented by a strip of seared skin. The amberjack, in turn, is a bit smoother and sweeter. Both slices leave you licking your lips in delight, appreciative that Bon Yeon can draw on this small taste of Yume (both the product and the technique used to prepare it) to please its guests. This dish may even serve as a gateway in getting hesitant diners, drawn to the “beef omakase,” to try the sushi version of the form.

With the first movement of tartare, jerky, oyster, and sashimi out of the way, the two chefs step into the spotlight. Brandishing wooden boxes, they walk you through an assortment of the cuts to come: tenderloin, ribeye, rib cap (or hanger steak), short rib, and skirt steak all neatly arranged in stacks with mushrooms, flowers, and herbs interspersed to make the scene seem a bit less grimly carnal. This presentation does not exhaustively display the rest of the menu (there are about five savory courses missing) but only comprises what will be thrown directly on the grill. On cue, the chefs turn a couple knobs in order to begin heating the hallowed grate. Slathering the metal with a block of fat, they take care to explain that the substance is made of tallow—glorious tallow—and not your everyday “vegetable oil.”

The presentation of the meats—and the introduction it represents for the “beef omakase” proper—also allows the chefs to expound on that all-important question of sourcing. On the occasion of your first visit, the meat on offer came solely from Vander Farmers in Sturgis, Michigan. There, the VanderHulst family raises cattle that are a crossbreed of the Japanese Black (one of four wagyu breeds) and Holstein varieties. They do so using “tracking device[s] paired with advanced algorithms” and “sustainable farming practices” (like feeding the livestock “healthy by products to reduce waste”), celebrating the fact that their meat only takes “about 24 months” (compared to 30 months for pureblood wagyu cattle) to become ready for consumption.

By the time of your second visit, the chefs were excited to announce that, in addition to the Vander Farmers beef, they had sourced a bit of A5 Kagoshima short rib. This meat is cultivated in the southernmost of nine wagyu-producing prefectures in Japan, one that is adjacent to the more pervasive Miyazaki but quite far from the Hyōgo Prefecture (whose prized Kobe beef has long cast its shadow over the entire category). Still, according to one prominent purveyor, “a considerable amount of Japan’s total Wagyu production comes from Kagoshima,” and that A5 rating ensures a consistent degree of marbling even if “each prefecture’s sense of place” differs. When you asked about the restaurant’s dry-aging cabinets on this occasion, the chef responded that they were experimenting with the practice but would not be able to serve any such meat for a few more months. Instead, the focus would remain on continuing to source more Japanese beef.

When it came to your third visit, Bon Yeon had moved away from both Vander Farmers and from the Kagoshima. That night, the chefs announced they had sourced American wagyu (from a different origin you did not catch) and Australian wagyu from Westholme. The latter brand cultivates cattle from Kedaka, Fujioshi, and Tajima bulls crossed with Mitchell cows, allowing them to graze for two years before moving them to a “spacious” feedlot where they are fed a “proprietary grain mix” for “at least 330 days.”

Ostensibly, you would expect meat sourcing to be the primary concern for a concept of this type. Thus, witnessing the restaurant’s choice of purveyors change from month to month might signal that the right partnerships were not formed from the start. To be fair, the Parks disclosed they could not (nor can anyone else) get a hold of the Hanwoo beef on which the Korean examples of this genre are based. So, some evolution in the products they are using is to be applauded: it demonstrates the chefs are learning, growing, and getting a sense of what—out of the ingredients that are attainable—works best. Just the same, you must ask if the beef being served at every point in this process is really worthy of a $255 ticket price (for why must paying customers act as guinea pigs?). Admittedly, you have found the results to be rather consistent across each of your meals.

At this point, it is also worth noting that, for the remainder of the meal, the chefs continue to act as dual masters of ceremonies. Naturally, the experience centers on the grilling process. However, they also lead the assembled diners through some other courses prepared by the cooks in the back. During the time in which the meat cooks, they make small talk with their respective sides of the counter and try to draw out a personal connection. In this task, both Dennis and Josh seem quite comfortable, sincere, and charming. Bolstered by the unerring precision of the servers, they are able to amply juggle their cooking tasks (basting, flipping, and cutting meats) with constant—though not overbearing—engagement.

When it comes time to plate and present, each chef drizzles sauces in a singular manner offers their own variation on a basic spiel (even to the point that, on rare occasions, they provide different instructions on how to best appreciate a particular dish). Early on, they had the tendency to talk over each other, but that has since been remedied. Instead, the pacing of the two grills can now actually vary by a minute or two depending on the eating speed of the particular parties. This is not a bad thing, for it makes the meal feel more focused and bespoke. But, again, it makes the differences in performance more recognizable and stark. It is hard to decide whether this is a sign of a disjointed script or of two professionals who, appropriately, have been given some leeway to make the act their own.

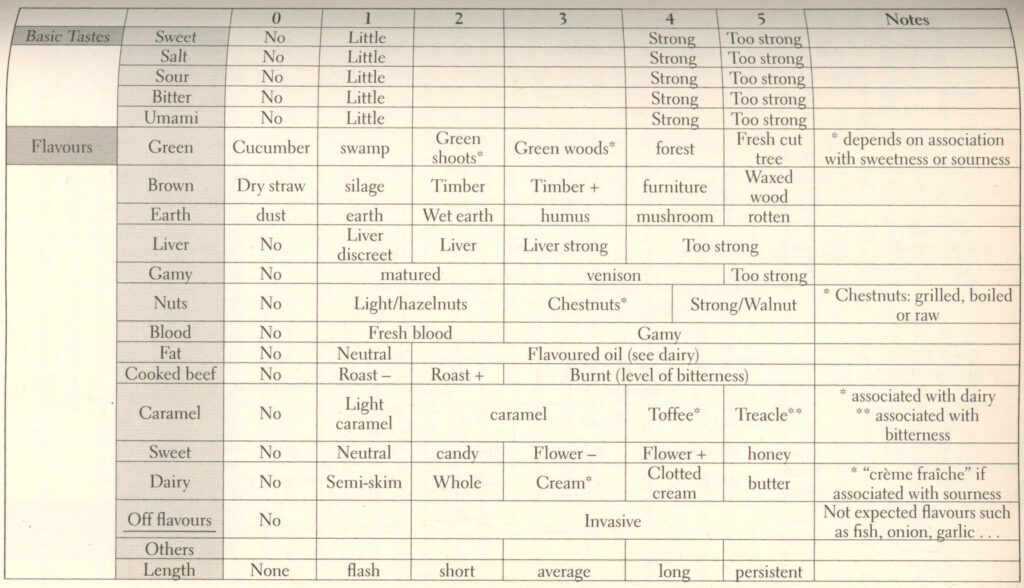

In practice, you have found little difference between the two chefs beyond the details already mentioned. This is to say, they distinguish themselves in terms of style but not so much in terms of substance. Neither one is exactly a compendium of bovine knowledge—explaining the nuances of cultivation, anatomy, and preparation (at a muscular level) like a butcher might—but the two men set the mood and let the beef (along with the seasonings Park has chosen for each cut) speak for itself. On paper, the lack of any rigorous educational aspect to the experience seems like a missed opportunity. You are sympathetic to that view, yet it is also worth asking to what degree the mainstream diner wants to feel lectured to. Surely, there is some balance between informative and fun that can be struck. Likewise, do the chefs need to carry such a burden if the cuts make their respective personalities apparent?

The opening bites of “Tenderloin” suggest that might be the case. This duo of morsels arrives with a nice crosshatched pattern across its exterior. This is matched by a good level of browning—the Maillard reaction—in the pockets of flesh between the intersecting lines, as well as an attractive color gradient—a small layer of gray giving way to intensifying degrees of pink—through the middle. Owing to the cut’s dearth of intramuscular fat (something that affects the perception of succulence even if the meat, being unworked, is rather soft), the tenderloin is paired with a bone marrow miso. This substance, which comes tucked into a cleaned piece of femur, used to arrive as something of a dripping mess. More recently, it arrives in a more browned, congealed package that, though you must caution the bone can be a bit hot, allows for easy extrication onto the beef.

Plucked with your chopsticks and deposited onto your palate, the tenderloin displays its namesake quality. The meat offers the faintest resistance before totally yielding to your teeth. With further mastication, the bone marrow infuses itself into the collapsed fibers of meat. The lean flesh attains a rich, slippery quality as the flavors build. The amount to a sensation that is sweet, caramelized, and lip-licking in its umami. You do not taste much “beefiness” (of the grassy, gamy, earthy, or nutty kind) but would not expect to. To that point, the center of the tenderloin sometimes comes off as a bit bland (this could be user error in neglecting to apply the bone marrow miso to all sides), and you have also noted some slight graininess/sinew on certain pieces (suggesting imperfect butchering). Nonetheless, this is a delightful, hedonistic set of pieces that immediately testifies to the pleasure on offer in this “beef omakase” form. Well done!

Next, you come to the “Ribeye”—a cut that many Chicagoans have come to particularly prize. Once more, the meat arrives as a pair of morsels. They possess the crosshatched pattern, the Maillard crust, and a shorter gradient of gray and pink speckled with streaks of fat. As a topper, each piece of beef is crowned with a large, thick slice of Périgord black truffle. They are joined on the plate by a smear of ssamjang (a spicy fermented soybean paste) purée and juxtaposed by a piece of pickled chayote or, more recently, by a thin slice of raw mountain yam.

Upon reaching your tongue, the ribeye exhibits a rich, moist mouthfeel and, once it meets your teeth, provides a heartier chew than the tenderloin. On one occasion, the beef offered a bit too much resistance (compounded by a slice that, fundamentally, was a bit too big). However, even when delivering the expected degree of tenderness, the meat is missing any real burst of flavor. The truffles, despite looking so pretty, offer only the slightest musky aroma and contribute nothing when it comes to taste (they should really also be warmed, for the raw texture at this thickness of slice is unpleasantly chalky). The ssamjang purée, to its credit, is only mildly spicy with some salty, savory notes. The pickled chayote and mountain yam, too, are cleansing in their own ways. But, as much as you might appreciate its crust and fat in theory, the ribeye just does not deliver any intensity of beef. It only differs from the tenderloin in terms of chew and saucing. Ultimately, this makes for an average—and, given the quality of steaks in this city, underwhelming—example of the cut.

The “Rib Cap”—also known as the spinalis dorsi (and considered by some to be the “crown jewel” of the cow)—promises a better experience. It is said to combine the fat and flavor of a ribeye with the soft texture of a tenderloin, so this placement in the omakase sequence makes sense. The two slices you receive are thinner and more irregular than those that come before. They display crosshatching but possess less of a Maillard crust, and you only note a faint hue of pink peeking out from the side. When it comes to accompaniments, the chefs opt, in this case, for a sprinkle of black sea salt (to be applied by the guest) and a side of pickled shimeji mushrooms.

Compared to the ribeye itself, the rib cap still possesses a pretty noticeable chew. You would still describe it as “hearty,” and, on one occasion, you even got a trace of that dreaded sinew. Still, at its best, the cut offers an appropriate amount of resistance relative to its thickness. In this case, you sense a mildly beefy (i.e., roasted, earthy) character backed by a bit of richness from the marbling. Nonetheless, the bulk of the flavor derives (should you apply it) from the smoke and minerality of the black salt. The mushrooms, in their own right, are sweet, sour, and mildly nutty. These accompaniments bring a lot to the table, yet you still wish the rib cap—especially considering the cut’s status—had more to say. Beyond the salt and the mushrooms and the difference in thickness, it is barely distinguishable from the preceding ribeye.

Likewise, a “Hanger Steak” that has been served, in the same fashion, as a substitute for the “Rib Cap” feels about the same. These slices of meat possess the same irregular shape as their predecessor while being imbued with a bit less fat. They also benefit from a proper exterior crust—in fact, the first appearance of some actual char. Ultimately, the hanger steak chews nicely and displays an appreciable savory quality drawn from bitter, burnt notes in combination with the smoky salt. The meat compares favorably with the “Rib Cap,” which, you suppose, is actually impressive given the difference in status between the two cuts. That being said, you are still looking for a greater sense of “beef.”

The ”Short Rib” provides you with another reason to get your hopes up, for the cut forms one of the most classic grilled dishes in Korean cuisine. This piece also provides you with a prime opportunity to compare the quality of domestic wagyu (served during your first and third visits) with the A5 Kagoshima (served during your second). The former variety has arrived as two long, slender strips with pronounced crosshatching and a good deal of browning. The latter, possessing more of a squared shape, only displays faint crosshatching, very light browning, and a shiny surface of milky-white fat. Accompaniments invert those used for the “Rib Cap” and “Hanger Steak”: the mountain yam being used in the first two instances before being replaced by the pickled chayote. However, instead of black sea salt, applewood smoked salt has been invariably used throughout each of the preparations.