Having tangled with the novel “beef omakase” form, you return to the comforting embrace of a traditional tasting menu. You also find your way back to a genre—Mexican (and, in this case, more broadly “Latin”) cuisine—that you haven’t engaged with since 2019.

Back then, Tzuco impressed you. It represented a homecoming for Carol Gaytán, the first Mexican-born chef to earn a Michelin star through his French-inflected fare at Mexique, and one in which he could leave some of that “hybrid” style behind to more wholeheartedly embrace the flavors of his homeland. The restaurant, at the time, was not perfect, but it was bold in its vision and unafraid to push Chicago’s appreciation of its chosen cuisine (translated through a more refined style) forward.

You reserved a great deal of your enthusiasm for Tales of Carlos Gaytán, a 12-seat tasting menu concept that would be tucked inside Tzuco. There, the chef hoped “to redefine the standard for Mexican cuisine served across the U.S.,” mixing “artistic invention with a fun, interactive element” intended to be “even more refined” than what was going on next door. The flavors, nonetheless, would be “really related to home”: like ant larvae with epazote, avocado, and blue corn tortillas; venison tartare with Huitzuco cheese, pickled black trumpet mushrooms, and huitlacoche crostini; and pork belly with chicharrón, roasted sweet plantains, and Yucatán salsa. Two sold-out preview dinners (priced at $225 per person) were staged in the space during February of 2020. It appears that another was conducted in November of 2021; however, the restaurant has remained in purgatory (with social media still active but no sign of opening) ever since.

That leaves Rick Bayless’s Topolobampo, celebrating its 35th anniversary this very year, as Chicago’s lone exemplar of the Mexican tasting menu form (though you do not forget Stephen Sandoval’s Entre Sueños, which is poised to return this year). There is little you can say about this restaurant—holder of a Michelin star throughout every edition of the Chicago Guide and winner of the James Beard Foundation’s “Outstanding Restaurant” award in 2017—that has not already been said. The establishment’s lasting quality, across all dimensions of the dining experience, stands as an immense achievement for a “celebrity chef” one may be tempted to count out. Topolobampo, undoubtedly, belongs in the pantheon of the city’s greatest restaurants of all time. Just the same, it operates with a degree of mainstream appeal—through which the concept has so effectively enchanted a wide demographic of diners—that leaves room (as Gaytán seemed set to provide) for something more.

After all, Mexican foodways have been a part of Chicago culture for more than a century. Today, they are absolutely foundational to how the city eats. Appreciation for the traditional has burgeoned alongside the proliferation of a new wave practicing a deeper exploration of regionality, a broader incorporation of outside influences, and the embrace of modernist technique. This movement, which enriches consumers’ understanding of the craft at the more approachable end of the market, naturally sets the table for something more: experiential dining and storytelling at the premium, luxury level. That is, the kind of restaurant other chefs have hinted at but, now, has been formally realized in Cariño.

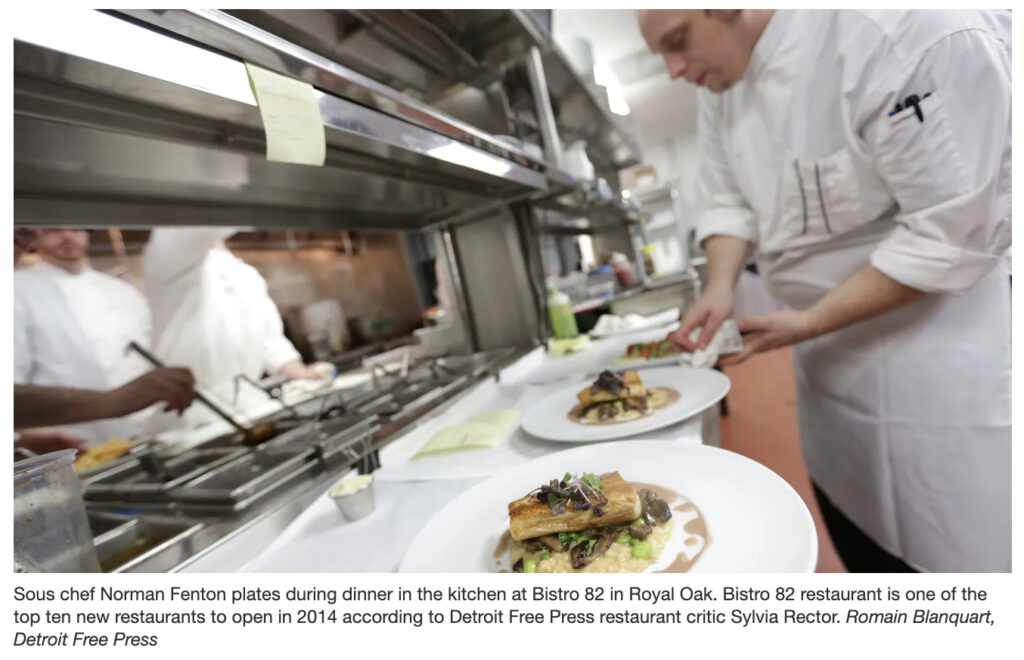

The story centers on Norman Fenton, a Detroit native whose “passion for food began at the age of 15” when he “obtained his first job in a kitchen” and was “introduced to new ingredients and cooking techniques.” (A trip to Nicaragua at age 16 with his aunt, who was “part of FEMA’s National Veterinary Response Teams,” also “changed his life.” It inspired him to make a “sea-salt caramel with cilantro” that was unlike what “anyone was doing” back home.) These experiences led Fenton to enroll in the Culinary Arts program at The Art Institute of Michigan, graduating in 2012, and to a four-year period working in Royal Oak, one of the Motor City’s inner-ring suburbs.

After rising to the position of chef de cuisine at Andiamo, an Italian trattoria, Fenton was hired by executive chef Derik Watson (who worked for Takashi Yagihashi at Tribute and later helped open Takashi in Chicago) as sous-chef of Bistro 82. The “contemporary French-inspired restaurant” proved “an early critical success,” earning the People’s Choice Award for “Best New Restaurant” from the Detroit Free Press and the “Restaurant of the Year” honor from Hour Detroit. During his time at Bistro 82, Fenton would become the executive sous-chef (also subbing “as head chef for several months”) in a kitchen guided by ideas like “what are we going to do to not be stagnant?” and “everything we’re doing we try to do it better, then the next day we either try to change it or do it better.”

In 2015, Fenton took his first executive chef position at dual concepts Tom’s Oyster Bar and Ale Mary’s Beer Hall. At the former property, he reinvented the menu with dishes like “Crispy Fresh Sardine” (with almond-caesar, panko, chive pesto, cured tomato, and radish), “Goat Cheese Panna Cotta” (with honeycomb crumble, apricots, and basil), “Sea Scallops” (with curried carrots, golden raisins, cauliflower, peas, lemon oil, and cardamom-spiced walnuts), and “Loup de Mer” (oven-roasted with tomato-olive compote, crispy capers, and pickled wax beans). However, after a little more than half a year, Fenton was ready for a new challenge.

The chef admitted at the time that he knew where his level of skill was at, knew where he wanted it to be, and, to get there, he’d have to “take a step back, learn from talented chefs, and then move forward.” Fenton noted that he’d “enjoyed being a big fish in a small pond,” but that “Metro Detroit’s dining scene is still a long ways off from reaching the kind of caliber found in cities like Chicago, New York, or San Francisco.”

As it happens, Fenton would be taking a chef de partie job at The Aviary—revealing, elsewhere, how he had an “eye-opening experience” when visiting the cocktail lounge and noting, “compared to Metro Detroit’s somewhat transient restaurant market,” how “everybody who was in the kitchen wanted to be there and they would do whatever they could to stay there and work and everybody worked just as hard as the person next to them.” Moving from executive chef to a lesser role was “one of those experiences where you’ve got to take a step back to take a leap forward.” He “couldn’t pass up an opportunity to work in a high-caliber restaurant in a larger market.”

Nonetheless, when speaking to Fooditor a couple years later, Fenton acknowledged he originally “set his eyes on working at Alinea.” Unfortunately, the three-Michelin-star restaurant “was closed at the time for a month-long sojourn in Madrid,” but he “needed to get out.” The Aviary “was definitely different,” yet his plan was to work his way up, somewhere, and “work for a couple years, and then go back.” However, making food at the cocktail lounge quickly felt unsatisfying: “You’re not really cooking, you’re assembling. Which…is true of most kitchens like that.”

After a few months, Fenton was “ready to move back” and “took a job working on an opening in Detroit.” He also staged at a seafood restaurant that “offered him a job three hours in,” but “it was very entry level” and would “be like an office job” for the chef. However, right as Fenton was getting set to depart, he learned that one of his colleagues at The Aviary “had just come from Schwa.” The restaurant, it was revealed, needed a cook, and Fenton was already intimately familiar with its work. Schwa was “one of the first places…[he] ever ate at” in Chicago during the two weeks immediately following his move. He went there by himself, they got him “pretty drunk,” and he “enjoyed it.” Now, that kitchen could offer a last chance to stay in the Windy City.

Fenton applied for the job under chef de cuisine Wilson Bauer—bane of influencers, destroyer of Steve Dolinsky, slayer of Ashok Selvam—and then “didn’t hear anything…for a week.” He actually “took the job in Detroit” before, “the next morning,” being offered the cook position at Schwa in August of 2016. Working “his way around the kitchen,” Fenton was eventually promoted to the role of sous chef. He was “also working a lot in the front of house, which was new for him.” This aspect of “interacting with people and it being so intimate and actually having a personality” appealed to him. So did “the fun behind it [the concept]” and the “rap music,” with Fenton describing himself at the time as “a pirate.”

Just the same, he lavished praise on chef-proprietor Michael Carlson, describing him as someone who “really gives you a nice outlet to express yourself—to, overall, be happy as a human being.” Fenton would note Carlson’s “generosity,” “his kind of father figure mentality,” “how kind he is,” and “how humble he is” as being what kept him (as sous chef) there. It would also keep him there when Bauer left in late 2017, allowing the Detroit native to step into the chef de cuisine role.

Fenton felt he was “set up for success” in this new position but told Carlson he would “need you with me.” The latter, for what it’s worth, “wanted to change Bauer’s menu quickly” and “put the stamp of the new collaboration on it.” The former chef de cuisine’s “best-known dish, a play on pork and beans” would be on the chopping block first. Its replacement would be a foie gras preparation inspired by the “flavor profile of Ferrero Rocher pralines,” incorporating Carlson’s signature cocoa nib brittle and—somehow—langoustine. Fenton was “intimidated” by the project but received “a lot of coaching” and “would just have to put it together.”

The chef de cuisine honed in on an idea of transitioning from the foie gras to a kind of soup, with those ideas forming “the two bookends” of the composition. Over a period of “weeks,” the kitchen “worked it out” through “a bunch of trials and tribulations.” The end result, labelled “the most interesting dish in Chicago” at the time by Fooditor, “started as a bowl of foie,” “slid from hot to cold” with the addition of yeasted ice cream, and finally, through the addition of a “langoustine ball” and some “steaming broth,” became a “bowl of soup” with a continuously changing flavor.

In the same article, Fenton would describe the movement of the dish in his own words: “You’re eating the foie and you’re getting fattiness, and you’re getting acidic notes from the mango and the little bit of vinegar that we use to glaze the trumpet mushrooms, and you get the nuttiness. But what you don’t get is the full-bodied richness. You just get fattiness, and it coats the side of your tongue and the tip of your tongue, but it doesn’t coat your entire mouth. So when you add the yeasted ice cream, everything starts coating your mouth and you’re able to pick up that excess foie fat that helps cut the richness to create a whole mouth experience, and also it takes you from hot to cold, in your mind and your mouth. And then you drop the langoustine ball.”

Doing so, he continues, enables “tying all the ingredients together as we go down the line.” For example, “the ball had the royal trumpet mushroom conserva, which there were trumpet mushrooms in the original bowl, and then there’s a mango slice, and you had mango gel in the bowl. And then the langoustine was also cured in the same cure as the foie and is set up in the same liquid as the foie is poached in.”

Asked how his food differs from Bauer’s, Fenton would note their “plating styles are different” and that there was “a little more masculinity” to the former’s food. Still, the latter wasn’t consciously “doing anything different.” His reign as chef de cuisine “was just about progressing” and ensuring that whatever he replaced was “going to be better”—not even in his eyes, “because it really doesn’t fucking matter what I think, but what the people who dine here think, and what Chef thinks.”

From Fooditor’s perspective, “Bauer’s food was notable today for its lack of Asian influence, but there seemed Asian notes to many of Fenton’s dishes, especially a mackerel course which could have come straight from Japan.” The latter chef didn’t know where those notes came from but would credit them to “strolling Joong Boo Market” and living near Chinatown, where he spent his first three months in Chicago dining everywhere and finding “a favorite dim sum place, a favorite duck place, a favorite egg roll.”

Ultimately, Fenton characterized the “progression of Schwa” during his tenure as one in which the concept was “trying to just become more refined” while “still keeping the character of what Schwa is, who Michael Carlson is.” Carlson asked him if he wants “to be the next chef de cuisine who just gets one star,” and a push was made “to go for two stars” by “creating a different atmosphere” based on the same shared passion. The restaurant would not, during that time, convince Bibendum to bestow it with a higher honor. However, Fenton succeeded in “keep[ing] Schwa relevant” and continuing to “push the envelope” some 13 years after its founding.

In 2019, Fenton left Schwa to take a “nine-month road trip from Chicago to Mexico,” immersing himself “in the local and innovative food scene” while “finding inspiration from Mexico City, Chiapas, Oaxaca, Michoacan and Monterrey” before “finally settling for a period in Tulum.” There, in October, he would host a set of Día de Muertos pop-up dinners “combining international cuisine and Mexican flavours” at a restaurant called WILD. Following these events, a “friendship and passion project was born.” Fenton met Karen Young, WILD’s owner, and was invited by the musical festival producer, humanitarian, and activist to become the concept’s executive chef. In that role (one he maintains to this day), he guides the culinary direction of the restaurant with the same focus on “international dishes with local ingredients and a Mexican twist.”

Fenton’s travels through Mexico would, it seems, provide an escape from the worst effects of the pandemic. (For what it’s worth, Young was successful in “raising thousands of dollars and distributing food packages to thousands of families in need” through NGOs in Tulum.) However, the chef—despite leading the kitchen at WILD—would not stay away from Chicago for long.

In August of 2020, Fenton replaced Matt Kerney (a Schwa alumnus and Michelin star holder at Longman & Eagle) as executive chef of Brass Heart in Uptown. The 20-seat tasting menu restaurant had opened exactly two years prior in what was once the 42 Grams space. It distinguished itself by offering both vegan ($145) and omnivore ($185), but early reviews were mixed.

In December of 2018, Chicago magazine would award Brass Heart one star (out of three). The piece praised dishes like “Ham and Eggs” (“a hunk of sausage made from acorn-fed pata negra pigs and served alongside a bulging poached quail egg on an island of toast in a jamón Ibérico consommé”) and “a cloud-soft fillet of halibut…poached in duck fat, topped with a pine nut tuile and matsutake mushrooms, and half immersed in thick celery root cream.” It argued that “no one in Chicago has ever served more ambitious vegan food.” However, “cappelletti chewier than bubblegum,” “shockingly bland seared lamb loin,” and “relaxed bordering on somnolent” pacing led the publication to declare that the restaurant “isn’t quite ready to compete.”

Writing for the Tribune in April of 2019, Phil Vettel would strike a more upbeat note. The critic “visited Brass Heart shortly after its August opening,” finding that the meal was “very good, but shy of transformational.” A “second trip toward the end of the year found a much tighter, brighter experience.” Finally, a third visit revealed “Kerney is starting to hit his stride”: the meal “wasn’t flawless, but it was impressive with eight hits and one ‘meh’ miss.” (Oh, how refreshing it is to read of a Chicago dining critic judging a restaurant on the basis of three experiences—though one must always question how, and why, certain concepts are given half a year to grow.)

Vettel praised dishes like “golden osetra caviar on a quenelle of potato chip ice cream,” “saffron bomba rice and judion beans…with garlicky chorizo and paprika gravy,” and Kerney’s “culinary signature” of “wagyu beef…topped with butter-poached mushrooms…and an airy pommes souffle” spritzed with “mushroom-infused Chinese black vinegar—an effect not unlike A.1. sauce.” Only a “take on fried chicken, presented as a brioche package with chicken, chicken skin, crunchy chicken bits and cream sauce” failed due to “gumminess.” By this point, Brass Heart was offering vegan and omnivore menu in both 9- and 12-course formats (with the former accounting for “almost 40 percent of sales”). Awarding the restaurant three (“excellent”) out of four stars, Vettel would close by saying “it would be tragic if more people didn’t get a chance to eat here.”

When Michelin released its 2020 edition of the Chicago Guide in September of 2019, Brass Heart would miss out on any stars, instead being named as one of “more than 100 restaurants with the Plate symbol, a designation given to restaurants that inspectors recommend to travellers [sic] and locals for a good meal with fresh ingredients and capable preparation.”

More specifically, the tire company would praise the “serious yet intimate” setting with a “playful spirit” (“as seen in the black-and-white portraits of Lollapalooza alumni that line the walls”). Further, Kerney’s food was praised as displaying “a tongue-in-cheek wit” as evidence by “potato-chip ice cream, which mysteriously evokes a classic bag of Lay’s with added zing from bursts of Osetra caviar.” Michelin also noted a “pristine spring pea soup…[with] sausage-stuffed rabbit loin and coins of pickled carrots” alongside “luscious scallops in beurre blanc.” Ultimately, Brass Heart was termed a “cool, clever twist on contemporary fare.”

Though it is certainly nice to be noticed by Bibendum in any form, this result must have been disappointing for a small concept of such aspiration. The pandemic presented Kerney with an opportunity to move to California, and his departure cleared the way for Fenton to arrive and “carve out a new identity for the restaurant.”

Though extensive records on the chef’s work at Brass Heart do not exist—a period, you might add, that would include the second major wave of the pandemic—you can survey some of his creations through social media posts and archival menus shared on review sites.

Fenton, from the start, tipped his hat to nostalgia—like a play on the “Chicago Fizz” made with savory rum custard, fizzy rocks, port wine reduction, and tart lemon meringue or a “Dippin Dots” constructed from shiso ice cream, lavender sorbet, and pink lemonade sorbet. However, the fruits of his time spent in Mexico also immediately came to the fore: a caviar course featuring huitlacoche (“the truffle of Mexico”), a “special course” of sautéed huitlacoche with black garlic emulsion, and an ode to Chiapas comprising chocolate ganache, blueberry purée, cinnamon meringue, and palo santo ice cream.

Nonetheless, some of the most exciting dishes transcended any easy categorization. This included sweet pea ravioli (with koji beurre monté, Oaxacan crème fraîche, pickled ramps, and uni bubbles), a “taco flight” (featuring one bite inspired by takoyaki), tomatoes (with tomato dashi gelee, sourdough crumble, ice wine-marinated currant tomatoes, tomato pâte de fruit, and osetra caviar), and a crunchy buñuelo (filled with guava purée, Délice de Bourgogne, and freeze-dried PX sherry).

Other notable dishes during Fenton’s tenure include:

- “Cocktail” (Tequila Sunrise)

- “Aguachile” (Ora King Salmon, Cucumber, Yuzu)

- “Aguachile” (Ora King Salmon, Cucumber, Hibiscus)

- “Agnolotti” (Huitlacoche, Sweet Corn, Truffle)

- “Tacos Dorados” (Chicken Liver, Adobo, Petite Lettuce)

- “Tetelas” (Huitlacoche, Green Olive, Black Garlic)

- “Tetelas” (Duck Confit, Gooseberry, Chipotle)

- “Foie Gras” (Mole Poblano, Cacao, Raisin)

- “Caviar” (Malt Vinegar, Onion, Potato)

- “Kanpachi” (Celery, Green Apple, Horseradish)

- “Striped Bass” (Celery, Green Apple, Horseradish)

- “Oyster” (Passion Fruit Coconut, Trout Roe)

- “Wagyu” (Parsnip, Banana, Cordycep)

- “Wagyu” (Tamarind, Mint, Alliums)

- “Coffee & Concha” (Wagyu Fat, Pasilla Chile, Consommé)

- “Pop Rocks” (Strawberry, Guanábana, Jicama)

- “Tascalate” (Achiote, Maize, Canela)

- “Coconut” (Mango, Passion Fruit, Marigold)

Though certain forms and combinations of ingredients were clearly favored throughout this period, it should be noted that you only have access to menus from February of 2021 and from January to December of 2022. Likewise, while Brass Heart was not formally rereviewed during Fenton’s time there, you can get a small sense of how patrons felt by looking at aggregator sites.

Searching from the summer of 2020 through the restaurant’s closure, Brass Heart received two four-star and 22 five-star reviews on Yelp (making for an average rating of 4.92 compared to 4.6 overall). On Google, the same timeframe yields 54 five-star reviews (making for an average rating of 5.00 compared to 4.8 overall). Though you must always keep in mind that the users motivated to engage with these sites only represent a small segment of the larger dining demographic, it is impressive to see such overwhelming positivity (when a dissenting review, from someone so inclined, would be equally incentivized).

Fenton’s time leading the kitchen at Brass Heart would improve on the work of his predecessor; however, it would not convince Bibendum. Michelin granted stars to Porto, Moody Tongue, and Ever in 2021 and awarded them to Claudia, Esmé, Galit, and Kasama in 2022. Somewhere along the way, the organization retired the Plate designation that Brass Heart had, indeed, previously earned. Thus, the restaurant was left to anguish in relative obscurity, unable to survive until the latest batch of stars was revealed in November of 2023.

In June of that year, Fenton announced Brass Heart’s closure with thanks “for all the guests that came to support” the concept and appreciation for “every single person that gave their helping hands throughout this tenure.” The chef noted that he wished “more people came and took the chance on sharing the experience with us” and affirmed the team “had a fantastic product but just not enough people.” That included “members of the media and social media influencers” who neglected “to see how he had reinvented the restaurant.” Still, Fenton revealed at the time that “Chicago hasn’t seen the last of him,” “the story is to be continued,” and “there are some things in the works.” Until then, he’d be “going to spend some time in Mexico” with his wife (whom he married in 2021) and children.

Just three months later, the first news broke on Cariño (address to be determined), Fenton’s forthcoming “16-course tasting menu restaurant centering around Latin cuisine using traditional and modern techniques.” There’d be a “wine pairing (featuring Latin American wines),” “cocktails made with agave spirits,” “spirit-free drinks,” and “agua frescas” on offer alongside a “progressive eight-course late-night taco omakase.” Even more impressively, the chef was “shooting for a November opening.”

When that month arrived, opening would be pushed back until December. Nonetheless, other details had fallen into place: Fenton would be “both executive chef and co-owner,” serving a menu of “12 to 16 courses with influences from Central and South American,” with a “noticeable Mexican influence,” and a price point of “about $190 per person.” He was taking over the former Brass Heart space at 4662 N Broadway with the help of WILD’s Karen Young, an “expert on design and marketing” thanks to her “experience on the festival circuit.” Fenton praised “their chemistry and their attention to detail in shaping a unique experience for the diners,” noting that “he’s had plenty of time to figure out [a] way to improve the space.” However, the chef made clear that the restaurant “goes beyond [an investment]”; rather, it represents “a passion” and his “family’s future.”

Cariño, after all, not only “refers to a feeling of fondness or love that a person has for someone or something” but “sounds fairly similar” to Fenton’s wife’s name: Karina. He described his time spent in Mexico as having “changed the course of…[his] life” and hoped that he could show his “deep love and gratitude to its people…through food.”

Otherwise, the chef would look to express himself through the restaurant’s music, which would “play a large role with Reggaeton, Latin hip-hop…[and] contemporary flamenco” on its playlists. Latin American whisky and pox—described as “the moonshine of Chiapas”—would appear as part of the beverage selection. And, with reference to the late-night omakase, Fenton declared (in his inimitable style) that “we’re just going to food fuck you with tacos.”

Cariño would open on December 28th with an aim to be “completely different than any other concept in Chicago.” Fenton would expound that the restaurant is “not Schwa or Brass Heart at all really,” but “it’s about still having fun with the guest experience and your staff.” To that point, the team would be looking to balance “bringing a much bigger personality and energy to the space itself” while “still providing a more cozy, comfortable feeling” and not “sacrificing a high-caliber dining experience.” They hoped to “raise the bar” for the chosen style of cuisine and “help to put the appropriate value on Latin American dining since it has been less commonly represented in the fine dining scene.”

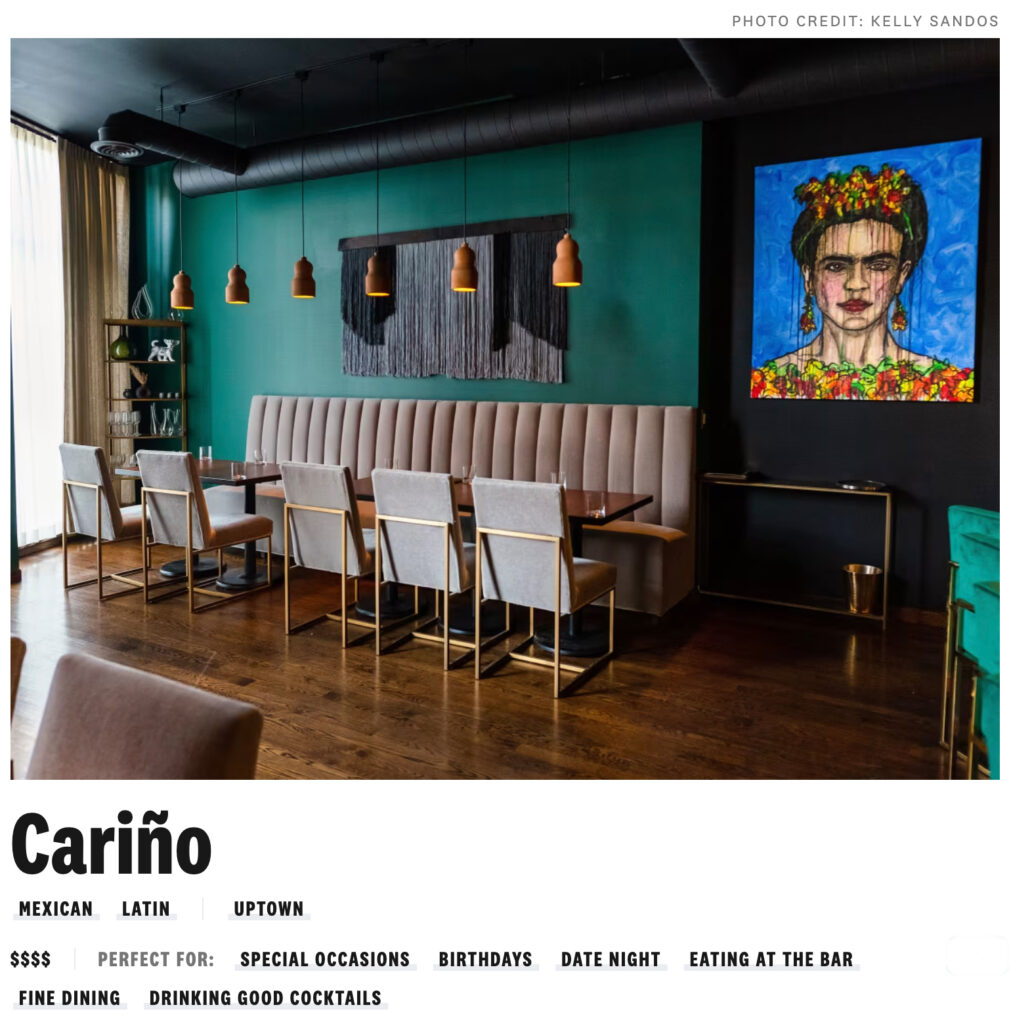

To accomplish that, Young transformed the space with “jewel-toned turquoise walls, textured terracotta pendant light fixtures, and art including textile wall hangings and a window pane mural from the Mochoacán.” Importantly, she restored the open kitchen and counter that had been a part of 42 Grams but were removed for Brass Heart. Fenton described himself as being “in a cage in that [latter] kitchen.” He “couldn’t see the customers,” and that was his “favorite thing about the industry”—being able “to interact with the guests.”

Young and Fenton brought on talent like sommelier Richie Ribando (of Next, Elizabeth, and Smyth) and bartender Denisse Soto (of Osito’s Tap) on the beverage side, which looked to “present one of the Midwest’s most extensive and thoughtful collections of Latin wines.” They also would “employ a 25% service charge on all bills in place of traditional gratuity to subsidize the salaried income of all its hourly employees, 5% of which will be split equally amongst the staff as a weekly bonus.”

This sense of compassion would even extend beyond the employees, with the restaurant selecting “one Latin-serving charity per year to share a portion of their profits with.” For 2024, the chosen organization is Latinos Progresando, “the largest Latin-led nonprofit organization in Chicago providing resources and legal counseling on immigration laws and policy.” This cause was described as being “close to Fenton’s heart,” as “he’s been engaged in the years-long process of obtaining U.S. citizenship for his wife and children in Mexico.”

At time of opening, Cariño offered a 12-14 course tasting menu for $190 (as promised) and an extended 14-16 course “Chef’s Counter” experience for $210. Dishes that were teased included an “Aguachile” (with Ora King salmon, kanpachi, jalapeño, and serrano chili vapor), “Ravioli” (with huitlacoche and crispy fried corn silk), and an homage to his “Mexican in-laws’ tradition of after-dinner coffee and cookies” via fried churros and a brew made with a “custom blend of Latin American beans.”

The taco omakase would not launch until the end of January, but the restaurant could claim to be “one of few restaurants in the city to grind their own masa on-premises” with “tortillas hand-shaped and cooked over a traditional comal for each course.” When the late-night offering (priced at $125 per person, inclusive of two drinks) did start, Fenton characterized it as a way to avoid the “fairly wasteful” side of fine dining by utilizing the scraps of the “great product in his kitchen” (like the remnants of salmon being processed into “tiny perfect cubes”). He was also “importing single-source corn” and “using an expensive machine with volcanic stones” to grind “ingredients like shrimp shells and black truffles into the masa” to “add unique flavors to their tortillas.”

The structure of the 10-course meal would comprise an oyster, a “variety of other masa-based dishes,” and a series of “four to five different tacos each night” including “a seafood taco, an A-5 wagyu taco, and always, a classic taco” (classic “meaning no modern twists, just the very best version of a Mexican staple that Fenton can make”). Ultimately, the taco omakase was “not an outlet to make a lot of money,” but one for the cooks to express themselves and “explore other ways to bring diners into the space.”

About a month after opening, some first impressions of Cariño began to trickle in. The Infatuation, though not assigning the restaurant a rating, noted that the courses are “playful and fun to eat” while the space “never feels stuffy or overly formal.” Michael Nagrant, never to be outdone, declared that Cariño “might be the best Mexican restaurant in America right now” in a preview of the (paywalled) review on his site, The Hunger.

In late February, David Hammond recounted being “hosted as media guests for dinner Cariño” in Newcity. He noted that the restaurant convinced him that “there’s still a lot of cool stuff that can be done” with molecular gastronomy and that, with this dinner, he “re-experienced the excitement of…[his] first dinner at Alinea sometime in the early aughts.” Hammond also contrasted Rick Bayless’s approach, “which is based in the chef’s anthropological understanding of Mexican culinary heritage,” with Fenton’s method of taking the food “a step further by creating entirely new dishes that leverage age-old techniques and ingredients.” Ultimately, Cariño’s food was “entertaining in its novelty and inventiveness, but more importantly, it tasted really good.”

Finally, at the beginning of March, Brenda Storch would feature Cariño’s “Taco Omakase” (alongside a similar offering from Taqueria Chingón) in a piece for Eater Chicago. She described stepping into the restaurant as like “being whisked away to a hidden hot spot in Mexico City” with “low lights, meaningful art, and an intimate setting…[making] you feel as if you’re in for something special.” Sizzling masa formed “the star of the show,” being expressed through dishes like a “blue corn tetela with duck confit,” a “truffle quesadilla with seasonal mushrooms,” and a “delightfully crispy and juicy taco de suadero.” In the article, Fenton also explained that the “taco omakase is curated based on what we as a concept feel like projecting that night” and is “subject to change based on ingredients and mood.”

Looking at Cariño on the review aggregate sites, you find the same sort of unanimous praise that characterized the chef’s work at Brass Heart. The restaurant, at time of writing, maintains a five-star rating on Yelp (based on four reviews) and a five-star rating on Google (based on 24 reviews). Users—some of whom have also eaten at WILD—describe “gorgeously presented, innovative, divine dishes that seemed too beautiful to eat at times” along with “deep appreciation for the breadth of Mexican cuisine and an ability to lighten the solemnity of the tasting menu proceedings with whimsy and creativity.”

It should be noted that some of these testimonials are based on a $65, five-course tasting menu that ran from January 24th through February 4th. However, Cariño should be applauded for making its food more approachable, and you note praise being applied equally to all the menus (i.e., “Chef’s Counter,” “Taco Omakase”) on offer.

That brings you to the present day and to a concept, about three months in, that has already hit some degree of stride. Diners “feel they will get Michelin stars very soon,” warn to “try it while you can still get a reservation,” and (perhaps even outdoing Nagrant) exclaim “this restaurant is the best in Chicago!” Fenton, whatever you ultimately think of his food, deserves credit for stomaching the demise of Brass Heart and coming back stronger. His answer, with the help of the right partners, has been to craft a restaurant that is even more intimate, more personal, more singular than before. A son of Detroit with a wife and kids in Cancún, he has wholeheartedly believed in Chicago and what can be accomplished here despite knowing firsthand how precarious the fine dining scene has become. That, alone, is worthy of admiration, and Fenton has created something—even just on paper—that stands as one of the city’s most exciting openings in quite some time.

You have experienced Cariño’s “Chef’s Counter” menu a total of three times, visiting in early January, early February, and early March. This period allows you to effectively track both the consistency and growth of the restaurant since opening. You have also sampled Cariño’s “Taco Omakase” twice but will address this offering in less detail. As usual, you will condense the sum of your experiences into one cohesive narrative.

With that said, let us begin.

It has been years since you’ve come to dine in this part of town: nine years (to be exact) since a series of meals at 42 Grams. That restaurant, one of only 15 to ever cross the two-Michelin-star threshold in Chicago, today inspires a feeling of dread as much as it does any wistful nostalgia. Yet, the circumstances of its closure aside, the concept—its shadow—stands as a testament to what can be accomplished here.

Here being the Uptown Square Historic District, stretching up Broadway and across Lawrence Avenue, known as “Chicago’s largest commercial and entertainment hub away from downtown in the early twentieth century.” Charlie Chaplin produced films here at the old Essanay Film Manufacturing Company (now home to St. Augustine College) from 1915-1916. The studio’s performers would patronize Green Mill Gardens (opened in 1914 on the site of an 1897 roadhouse), a venue partially owned by one of Capone’s capos during Prohibition and predecessor of the present Green Mill (reopened in 1935). The Riviera Theatre (built in 1918) and Aragon Ballroom (built in 1926) also remain in operation while the Uptown Theatre (first opened in 1925) awaits a long-discussed renovation after more than four decades of disuse.

Fine dining has not exactly featured as part of this neighborhood’s proud history, but that does not mean its denizens want for enticing things to eat. Demera, Ragadan (another Nagrant recommendation), Milly’s Pizza in the Pan, and the second location of Birrieria Zaragoza distinguish this neck of the woods. Of course, you cannot forget the West Argyle Street Historic District (nicknamed “Asia on Argyle”) with its array of Vietnamese, Chinese, and Thai restaurants. Overall, this part of Uptown has been shaped by migration—Appalachian coal miners in the 1950s, Native Americans in the 1960s, then Korean, Cambodian, Cuban, African, and Middle Eastern refugees in the 1970s and 1980s—and by the practice of craft without undue embellishment.

That makes 42 Grams, which grew organically from “underground” dinners in the chef’s “standard apartment kitchen,” seem like something of a kindred spirit. The original concept, titled Sous Rising, cultivated customers through Yelp, through people “looking for what’s the best dinner in Uptown, what’s Michelin-starred in Uptown,” and finding nothing but a mysterious “five star [restaurant] in this area.”

Brass Heart, the product of restaurateurs who “met…while working at the Board of Trade” and were “also investors in Schwa,” was more consciously constructed as a destination. Kerney “happened to walk in the door” the day that 42 Grams co-owner Alexa Welsh “scheduled something of a fire sale to dispose of the tiny restaurant’s equipment.” They took “everything” and launched at a $185 price point that “instantly enter[ed] the ranks of Chicago’s priciest prix fixe menus” but, as symbolized by the removal of the former concept’s chef’s counter, lacked the same local, personal dimension.

In Cariño, you find a sense of redemption and transformation that lands somewhere in the middle. Fenton toiled at 4662 N Broadway and faced the pain of having to close up shop. Yet he has now reemerged as a co-owner and doubled down on the same neighborhood. Could the chef be attached to confines and a kitchen he already knows well? Sure. However, in Young, he has found a partner that is “sensitive to community needs, not wanting to just open a business and profit off locals.” Fenton has restored the chef’s counter, sought to express his personality, and to “put the appropriate value on Latin American dining” at a price point ($65 during Restaurant Week, $125 for the “Taco Omakase”) that could conceivably be embraced by the neighborhood. He also taps into an existing market for Mexican cuisine that goes well beyond the new Birrieria Zaragoza to include Carmela’s Taqueria, Fiesta Mexicana, Kie-Gol-Lanee, Mr. Salsa, and Taqueria Diamante all in close proximity.

However, in practice, Cariño is quite inconspicuous. The restaurant is sandwiched in the middle of a three-story brick building with a hair salon on one side, an empty storefront on the other, and apartments spanning the two floors above it. A train overpass runs perilously close to the structure, casting its shadow over the surrounding segment of North Broadway and further obstructing the view. As you search for parking, you note the various neighbors: a hardware store, a recording studio, a community college, a Buddhist temple, a bike shop, a rock climbing gym, a forthcoming grocery co-op, and other eateries serving up pizza, sushi, donuts, Thai, and Chinese fare.

Taken together, the neighborhood sounds surprisingly trendy—if you discount the two cemeteries—despite many of the edifices looking so timeworn. Judging by the spurts of development occurring up, down, and across the block, refurbishment—or outright demolition—will one day reach them too. But, for now, the area already enjoys a good bit of foot traffic drawn from the entertainment venues along Lawrence Avenue and the more quotidian concerns of those living in the surrounding three- and four-flats.

Approaching Cariño, you could be forgiven for wondering just where the restaurant is. 4662, its street number, is posted only on an adjacent door (4660-62) that leads to those aforementioned apartments. There is no signage—understandable when considering that all the menu being offered demand prepaid tickets. Yet GPS, as always, is your friend. It points you to a rather understated part of the building’s façade: a set of three floor-to-ceiling windows obscured by white curtains and joined by an inconspicuous black vestibule. From afar, you can just about make out a chandelier and some sense of the warmly-lit space within. Prying open the door, you find confirmation—4662—and catch your first sight of the chef’s counter that waits to host you.

Stepping through the entryway, your party is promptly greeted, relieved of any unwanted belongings, and guided those fleeting few steps to the six seats set facing the kitchen. It’s almost a shame to have chosen this more premium perch, for it robs you of the chance to appreciate the dining room.

Save for the banquettes, the chairs, and the wooden flooring, the space has been totally transformed from Brass Heart’s museum-like aesthetic. White wallpaper has yielded to a comforting teal tone matched by the plush cushioning of the stools along the counter. The gilded lamps, once set into the walls to illuminate series of black-and-white photos, have also been traded for earthen looking fixtures that hang over the tables from the ceiling. This makes way for a set of ornate mirrors, a sculpture made from cords of textile, and two distinctive canvases to define the wall space without seeming so consciously “on display.” Rather, the works’ assorted textures and colors remain somewhat confined to the shadows. They are not focal points, but details to be discovered during the course of a performance whose spotlight remains trained on the kitchen.

From one of those six places at the chef’s counter, the nature of this “stage” comes into focus. You find the white tiling you remember from 42 Grams along with the same range, hood, shelving, and sea of stainless steel. Fenton, for what it’s worth, has more toys on hand: totems of molecular gastronomy, purpose-built tools, and traditional Mexican cookware alike. Countless carefully labelled containers, filled with this or that ingredient, are also strewn throughout the space. However, you mostly note that the counter has, itself, been altered so that guests are served on a wooden surface that rises above the level of the kitchen. The ceiling above the pass has, too, been fitted with a trio of sizable heat lamps whose glow, when utilized, sets the entire restaurant alight.

Of course, Fenton has also made the workspace feel more like his own via a small collection of cookbooks (Noma 2.0 towering above the rest), one tome dedicated to fútbol, and a Lionel Messi Funko Pop! figurine dated to those dark Paris Saint-Germain days. The pass is also aligned perfectly with the dining room’s two most prominent pieces of art: a portrait of Frida Kahlo by local artist Joey Africa and a window pane mural the chef sourced in Michoacán five years ago (that formerly hung in his home). These works, vividly rendered in tones of blue, green, yellow, and red, give the restaurant a much-needed dose of color. Just the same, in the shadowy environment, they amount to little more than a wink—a love of tradition that does not descend into caricature but, instead, acts as a jumping-off point for something novel.

Along these lines, you must also mention the staggered shelving, whose rows showcase more than 50 bottles of tequila and mezcal, that is arranged between the two canvases. Impressive in its own right, the collection communicates an appreciation for craft and for a sense of terroir that agave, compared to most other distilled beverages, uniquely translates. It also, once you witness how eagerly Fenton shares shots with his guests, testifies to the kind of freewheeling hospitality the restaurant likes to practice.

With three cooks and one chef ceaselessly toiling behind the counter, the kitchen you described in terms of organization and equipment totally comes alive during service. Though always kept immaculate, the space is clearly functional: more “mad scientist” than quiet, cloistered laboratory. However, therein lies the charm, for you can appreciate the coordination of the four bodies working around each other, the fire (of the stove) and ice (of molecular gastronomy) that punctuate the action, those four sets of hands coming back together to plate the food, and the magic through which this inexhaustible arsenal of ingredients and techniques comes together to create a single dish—over and over again.

Add to this Cariño’s soundtrack, whose selections may be instantly recognizable to some guests and imperceivably eclectic to others, and you are left with a performance that flows almost effortlessly on any given evening. It helps that the playlist proceeds in the same order on each occasion, with ebbs and flows and irreverent interludes sprinkled throughout. The team is fueled by this music—they bob their heads and bounce and even clap at times—in such a way that it really feels like the score for the evening’s action. In this manner, the soundtrack transcends the role of background noise to form an engrossing emotional core of the experience that communicates Fenton’s taste and his shared bond with the staff.

Overall, Cariño’s environment represents a clear improvement on what was done at Brass Heart. In that respect, opening up the kitchen has obviously had a decisive effect. However, it seems like the previous concept had a sense of refinement in mind when first closing it off: creating a black-and-white, jewel box of a dining room served from somewhere out of sight. Yet, despite that intention, the space turned out to be too small, stuffy, and a bit anonymous (as design within the “contemporary American” genre can often seem).

It may be true that Fenton’s clear focus on Latin American cuisine helps to moderate expectations: Cariño need only look good in comparison to Topolobampo, Tzuco, and a range of relatively humble eateries throughout Chicago. However, Young and Fenton’s vision really does stand on its own. 4662 N Broadway has never looked better (even when it could claim two Michelin stars), and it achieves a more convincing sense of luxury than its predecessor through a careful blending of color and texture in a cohesive, approachable package. There is no sense of intimidation or separation upon stepping into the restaurant. Rather, you are absorbed fully by the totality of the operation—service, touch, smell, sound—immediately and graciously welcomed to meet its rhythm, its movements, as you naturally are. You acclimate to everyone and everything, teasing out the room’s finer details, as the action begins. By the time you take your first taste of the food, you have already been primed for a personal connection with Fenton’s work.

You cannot speak to what it feels like to be seated in the dining room (though, by all accounts, these guests still benefit from plenty of chef interaction even if they miss out on the same number of dishes or privileged view of the action). Nonetheless, you must declare that Cariño’s chef’s counter—a self-described “immersive” and “interactive” experience—ranks favorably against any similar offering in town. You speak of the kitchen tables at Alinea and Oriole along with the chef’s table at Smyth, premium seatings that may come with extra courses (in the first and last case) and more personal attention from the staff but lack the same visceral feeling of being right up against the action alongside the concept’s esteemed chef. You might also mention Valhalla, which provided a bit of this intimacy but operated at a scale (and within a setting) that did not feel quite so singular.

Yes, you can only compare the closeness and level of access Fenton grants his diners to the omakase form (though Joe Flamm, for a short period, hosted one of the city’s best chef’s counters at Rose Mary). And, within that genre, you can only compare Cariño to chef-owner concepts—ones where the restaurant does not open without its star craftsperson—like Kyōten, The Omakase Room, and Yume.

Fenton, in his boisterousness, clearly comes closer to Otto Phan than Kaze Chan or Sangtae Park, yet even that comparison denies his singular tableside manner: that of a playful, unapologetic stoner who knows how to lighten the mood but—at core—is deeply, earnestly engaged in his work and totally obsessed with his chosen cuisine. Despite putting on this show for a few months now, there is nothing contrived or scripted about the Detroit native. Consequently, any roughness around the edges has an innocent, disarming quality to it that makes you appreciate his approach all the more. This, in truth, is the only “authenticity” that matters: to oneself. And Fenton, with Young’s backing, has created a place where he can really shine: redefining the nature of chef interaction—of connection with the artisan—in an exceedingly modern manner and to a degree that only a couple Chicago restaurants have ever aspired to.

In this task, the chef is undoubtedly helped by his team: two members of the front of house and three members of the back of house that jointly share the stage. The former duo, donning slick black suits, orchestrate proceedings much as the staff at an omakase would. They are friendly when greeting you, patient when guiding you through the beverage options, but, once the “show” begins, these servers meld seamlessly into the background. Operating behind you, they stand ready to clear plates, replace utensils, and refill water at a moment’s notice. Should you require another drink, they make the menu reappear out from thin air.

Compared to the kind of service you recently praised at Bon Yeon, whose craft of hospitality benefitted from a numerical advantage and some top-drawer training drawn from a New York pro, Cariño’s front of house is missing some of the same frills: you speak of embellished pouring, faultless deference, and the kind of whispered diction that triggers ASMR. Just the same, Fenton’s team (serving a menu that costs $45 less per person) is as good-humored and attentive as you could want. They have not completely mastered tracking the handedness of each guest (failing to notice, neglecting to remember on future visits, and sometimes even overcorrecting by subsequently misplacing the utensils of adjacent diners), but this is a minor lapse. What’s important is that the servers faithfully support the kitchen’s performance and feel like an extension of the chef’s own manner of hosting. This shared attitude—buffered a bit by the front of house’s requisite professionalism—ensures the experience feels cohesive and complete.

The back of house, being tasked with helping Fenton create the meal, plays a more nuanced role. These three cooks are as much on display as anyone, occupying various stations throughout the kitchen and maneuvering alongside the chef when it comes time to plate. The technical demands of the food, some small degree of turnover (normal for a young concept), and the presence of stages mean that the team is being educated, corrected, and even lightly chastised at times by their boss. This is where Fenton’s capacity for leadership comes to the fore, and he reveals himself to be a benevolent—if demanding—craftsman who expects the best from his brigade but is never afraid to get his hands dirty showing how this or that should be done. At the same time, it only takes hearing the chef praise his cooks and seeing their reaction (usually a beaming smile) to know the respect and admiration the kitchen shares.

However, when it comes to the chef’s counter “performance,” the back of house really helps to define the quieter moments. Of course, Fenton’s brashness commands most of the attention, but he is often rushing from one place to another until there’s a natural pause and he can, for a moment or two, engage the guests. So, you may often find yourself seated in front of a cook who is going about some more menial task. You can engage them—or, if sensing it won’t interrupt your conversation, they may interject—and chat about the meal, the music, where you’re from, and what Chicago is like. The cooks may generously offer to take a picture if they see your party struggling with a selfie. Stay really late (that is, after the “Taco Omakase”), and you may even get to share a toke.

The level of English proficiency can vary a bit between these shy, hardworking souls, yet this makes the resulting connection feel all the more rewarding. (Spanish speakers, in turn, will find themselves joyously received with a corresponding barrage of chatter.) Fenton draws on this dynamic to great effect when asking the cooks to step to the center of the counter and introduce certain dishes, a task that may very well result in the chosen speaker sheepishly scurrying back to their station without even a word.

You hesitate to say that this slight language barrier makes the experience feel more “authentic.” Rather, it serves as a reminder that the cooks’ work—the care they put into the food being presented—transcends what can be communicated explicitly. Additionally, their close attention to the diners’ experience, even if exact words prove slippery, confirms that hospitality is felt far more than it is spoken. The back of house plays its role with total comfort and sincerity, adding meaningful depth to the counter’s interactive element and paving the way for greater self-expression from the guest. Once more, you perceive that you are being welcomed into the totality of the space by the totality of the staff. Thus, the performance Fenton and his team put on feels not only entertaining but, undeniably, heartfelt.

Taking your seat at the counter, you get your bearings. Demographically, you have observed a crowd that is predominantly white and middle-aged. Some note that they come from the surrounding neighborhood. Walking by the building, these locals noticed rumblings of activity behind those white curtains and, upon investigating further, sought to give the concept a try. Others simply run the Chicago fine dining circuit, eagerly sampling one of the city’s newest, most ambitious tasting menus whether or not they experienced Fenton’s work at Brass Heart.

Though, in effect, Cariño is a reimagination of its predecessor—comprising some of the same dishes, from the same chef, at the same (albeit transformed) address—the restaurant benefits from its own proper promotional cycle. Fenton is not, like last time, sliding into an existing property: one whose name the dining public may have heard of but, with the pain of the pandemic and a lack of that precious Michelin star, ultimately faded into obscurity. Instead, with Young’s support, he has gotten to actualize and assert his own vision from the start. Cariño offers a new beginning with a clear theme and barrage of media attention (echoed, in late January, by the launch of the “Taco Omakase”) that ensures a steady enough flow of early customers.

While the seats in the dining room have, across your visits, largely gone unfilled, the counter—that is, the most photogenic and memorable facet of the restaurant—more reliably sells out on the most popular days. It attracts the locals and the “foodies,” who equip the restaurant with shareable content that helps drive its viral appeal. However, Cariño has also attracted a small contingent of Latin American diners, ones who may also belong to those broad categories but, also, are primed for a more personal connection to the food. Fenton and the cooks clearly revel in hosting these guests. They have access to some of the shared nostalgia other patrons may not, and they may even be invited to describe certain dishes or ingredients for the rest of the counter.

You think attracting this demographic, the kind Tzuco (but maybe not Topolobampo) effectively taps into, may play a decisive part in the restaurant’s success. Young’s work with “Mexican charities in helping the needy” and desire “to do the same in Chicago,” along with Fenton’s efforts to make his food accessible at different price points, lends credence to such a strategy. Considering the chef’s stated desire to “put the appropriate value” on “less commonly represented” Latin American dining, these gestures also provide a sense of legitimacy to their endeavor. They, along with the art and the music, signal Cariño is not Disneyfied for the sake of the culture’s outsiders but, rather, unifying in its depth. Bringing these diners together is a task that Fenton, due to the nature of his life experiences, is well-suited to perform. And it could very well cultivate a Latin American fanbase that, frankly, you observe in disproportionately low amounts when dining at tasting menu concepts around town.

Settled in, you only have one decision to make tonight: what to drink. The first set of options come courtesy of Denisse Soto, who has designed five cocktails for Cariño that are priced between $15 and $18.

The most expensive of the bunch, the “Mi Campo Margarita” ($18), totally subverts what you might expect from this famous libation. It combines Bosscal Mezcal with flavors of kiwi, nopal (i.e., cactus), and green apple, making for a striking green on green on green color that is capped off with a chiseled orb of Chartreuse ice and a bit of salt on the rim. Though the use of mezcal imbues the drink with a certain amount of smoke, the fruity, tart, and herbaceous notes at hand ensure the blend tastes bright and layered.

Guests desiring a tequila-based margarita will find that the team can make it after some prodding. (The “Mi Campo Margarita” is made in batches, so a straight substitution or repurposing of the components isn’t possible.) The results are not as inspiring, and having more flexibility in order to meet these customer requests could be valuable (also considering the breadth of agave spirits on offer). On the other hand, diners visiting for the first time should, you agree, be pushed to try cocktails that are the unique expression of a craftsperson, drinks that look to transcend mere deliciousness and challenge how classic recipes and ingredients are perceived.

On that note, you have also sampled the “Sueños” ($15), which combines blanco tequila with maraschino liqueur, Crème de Fleur (a floral/botanical liqueur), pineapple juice, and absinthe. Again, Soto resists the temptation of providing easy pleasure in favor of something more cerebral. However, the uplifting fruit maintains a sense of refreshment as the tequila, mixed in this fashion, expresses a complex vegetal quality. The Morada Sour ($16), made from Barsol pisco, Trä-Kál (a Patagonian spirit), Peruvian purple corn, tamarind, baking spices, and orange, may look bold on paper. However, it is rich, round, and replete with notes of spiced citrus and berry fruit that makes it, for your palate, the most mellow and enjoyable of the bunch.

The ”La Guacamaya” ($15), a combination of Uruapan Charanda Añejo rum, mamey (a kind of tropical fruit), coconut syrup, lemon, and Angostura bitters. Those expecting a cocktail in the daiquiri mold will be surprised to find a far more serious expression of the spirit. Namely, that is drawn from the mamey, whose flavor is compared to a honeyed sweet potato or pumpkin. This fruit’s earthiness really emphasizes the molasses notes of the rum, which even displays some whiskey character drawn from aging in bourbon barrels. With the coconut, lemon, and bitters added in, it all makes for an intriguing blend (so long as you know what you’re getting into). Finally, there is the “Oaxaca Old Fashioned” ($16), made with Wahaka mezcal, piloncillo (a raw form of pure cane sugar), and bitters, that you have not tried.

Overall, Soto has swung for the fences with a selection of drinks that are thought-provoking without being unapologetically challenging. Rather, they are carefully and creatively crafted, urging the drinker to meditate on ingredients they might know through the discovery of—and their combination with—ones they might not. The drinks also aesthetically pleasing (through the use of color), texturally interesting (through salt, foams, and toppings), and appropriately priced. As mentioned earlier, a bit more flexibility in being able to satisfy customer requests could be the cherry on top. Nevertheless, for a restaurant with Michelin star ambitions, this is an impressive lineup.

The beverage selection also comprises non-alcoholic options like Coca-Cola, Sprite, Mundet (an apple-flavored soft drink produced by Coca-Cola) and a “Refresco del Día” (a rotating selection that has included Mexican Fanta), each for $5. There’s the “House Made Agua Fresca,” which Fenton and his team make from the kitchen’s waste product. You have sampled soursop/lime, huckleberry, and pineapple/red beet flavors during the course of your visits finding them all to be fairly enjoyable (if not totally mindblowing). On one occasion, when ordering the agua fresca at the beginning of the meal, the restaurant had run out. Given the creativity and sense of personality (not to mention sustainability) this offering brings to the non-alcoholic section, that should not happen. Otherwise, you also find coffee and tea.

Those so inclined can also count on an assortment of five beers from Casa Humilde Cervecería, a West Town-based brewery from Mexican-American brothers Javier and Jose Lopez. Born in Hermosa, they launched the brand by “home brewing on the second floor of their parents’ home” with the “humble” goal of “bridging modern craft beer and Chicago’s Mexican and Mexican-American communities, which largely remain loyal to the classic Mexican brands.”

Cariño serves Casa Humilde’s “Maizal” (“brewed with just the right amount of corn for a pleasant touch of sweetness”), “Alba” (“pleasantly toasty”), “Media Naranja” (“brewed with Mosaic & Citra hops along with orange peel”), and “Viva La Frida” (a hibiscus and lime lager made in collaboration with the National Museum of Mexican Art and the Beer Culture Center) bottlings for $7 a piece. The “Piñata” (made with BRU-1 and Citra hops then flavored with pineapple) costs $8. These are joined by a rotating “Cerveza del Día” ($5) in the same fashion as the aforementioned “Refresco del Día” (though, in this case, you cannot speak to what has been offered).

Of course, wine always forms the main event for you, and, with Richie Ribando, Fenton can count of the expertise of a sommelier with a real pedigree. You were a fan of his work at Smyth, which you felt smartly anticipated the boom in German Riesling while also balancing the selection with well-chosen bottles from Burgundy, the Loire, and Italy. Here, at Cariño, Ribando has been faced with the challenge of building “a uniquely extensive selection of Latin wines”—and that means (in the chef’s own words) “if it’s not from Latin America, you can’t get it here.”

When purchasing tickets for the tasting menu, guests are invited to select one of two turnkey options if so desired: a “Standard Pairing” ($95) and a “Reserve Wine Pairing” ($165). The value proposition provided by these set pours, a hallmark of fine dining, has recently been interrogated by Chicago magazine dining critic John Kessler. You generally agree with his argument, for few restaurants in the city can claim the kind of deep cellar filled with aged (but not prohibitively expensive) bottles or allocated (but also not overpriced) releases from which an interesting medley can be made. Further, few establishments empower their wine professionals to supplement their lists with small parcels of wine sourced from the gray market, a process that can provide the sort of cherries that really make purchasing a pairing worthwhile.

(In Chicago, The Alinea Group is probably the worst abuser of pairings as a cynical source of revenue while Louis Fabbrini of Smyth, Jelena Prodan of Valhalla, and Emily Rosenfeld of Oriole are among the very best at crafting pairings that combine variety and value with a real sense of surprise. Fabbrini, in particular, has distinguished himself by reserving the restaurant’s most coveted wines solely for the pairings—a maneuver that turns the traditional consumer calculus on its head by richly rewarding oenophiles who may otherwise almost always prefer spend an equivalent amount of money on one or two full bottles.)

At Cariño, Ribando is designing pairings for an audience that may have little experience with Latin American cuisine, Latin American wines, or—especially—a synergy of the two in an intimate, experiential format. With bottles ranging in price from $52 to $260 (and encompassing some perplexing grape varieties and appellations), the prospect of paying $95 to sit back, relax, and simply enjoy the meal is alluring.

Having sampled the “Standard Pairing” (though neglecting to record exactly what it comprised), you feel it is a good option for diners who desire variety and a little extra engagement with the overall theme. The seven pours provided are generous (some needing to last through multiple courses), approachable, and span sparkling, white, red, and dessert options. You must admit that only one of the pairings really enhanced your perception of its associated dish—the rest merely forming pleasant companions to the food—but this is almost always the case at any restaurant. Choosing this option (as opposed to ordering cocktails, beer, soda, or agua fresca à la carte) really has more to do with wanting to try a few different things and learn about Latin American wine. Ultimately, it serves that purpose well.

The “Reserve Wine Pairing,” which you also sampled, comprises these particular bottles:

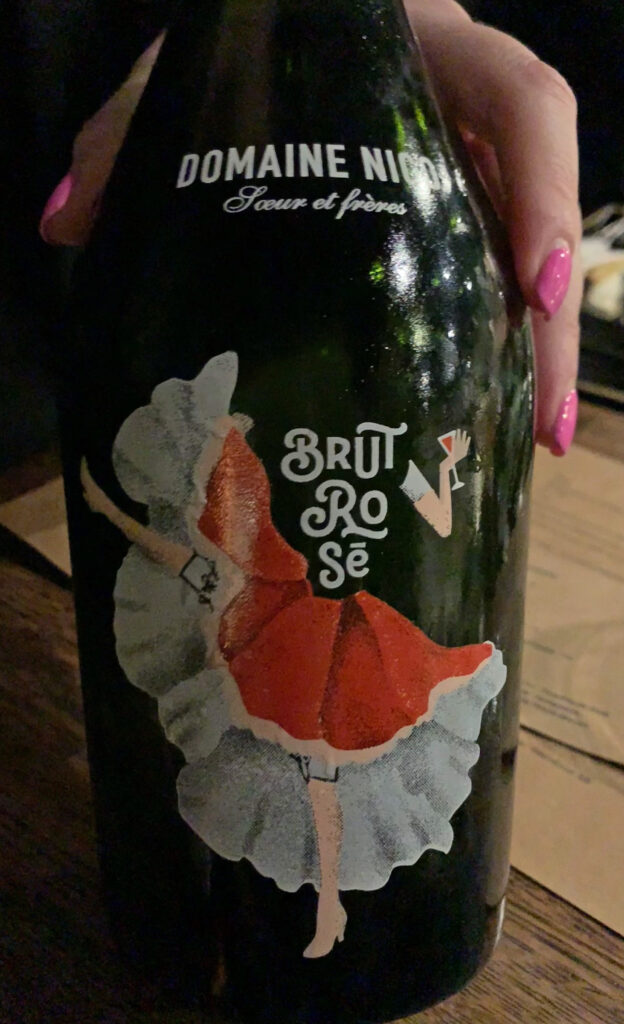

- NV Domaine Nico Brut Rosé Uco Valley

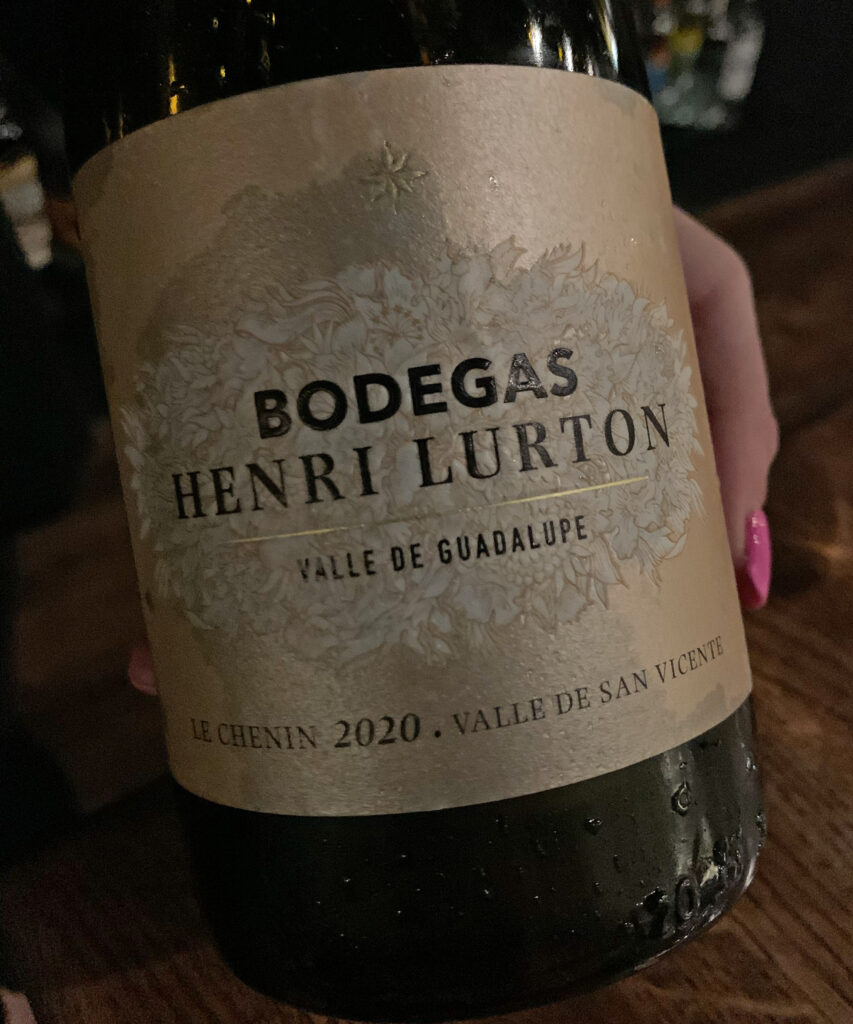

- 2020 Bodegas Henri Lurton “Le Chenin” Valle de Guadalupe

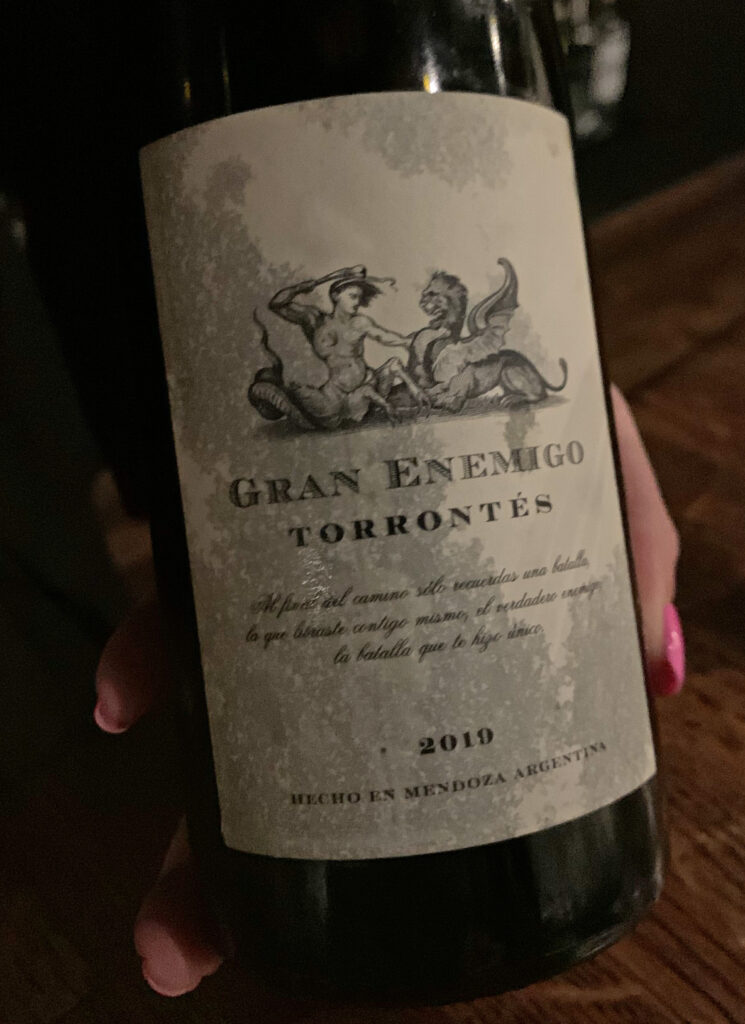

- 2019 El Enemigo “Gran Enemigo” Torrontés Mendoza

- 2021 Bodega Chacra “Chacra” Chardonnay Patagonia

- 2020 Pedro Parra y Familia “Trane” Cinsault Itata Valley

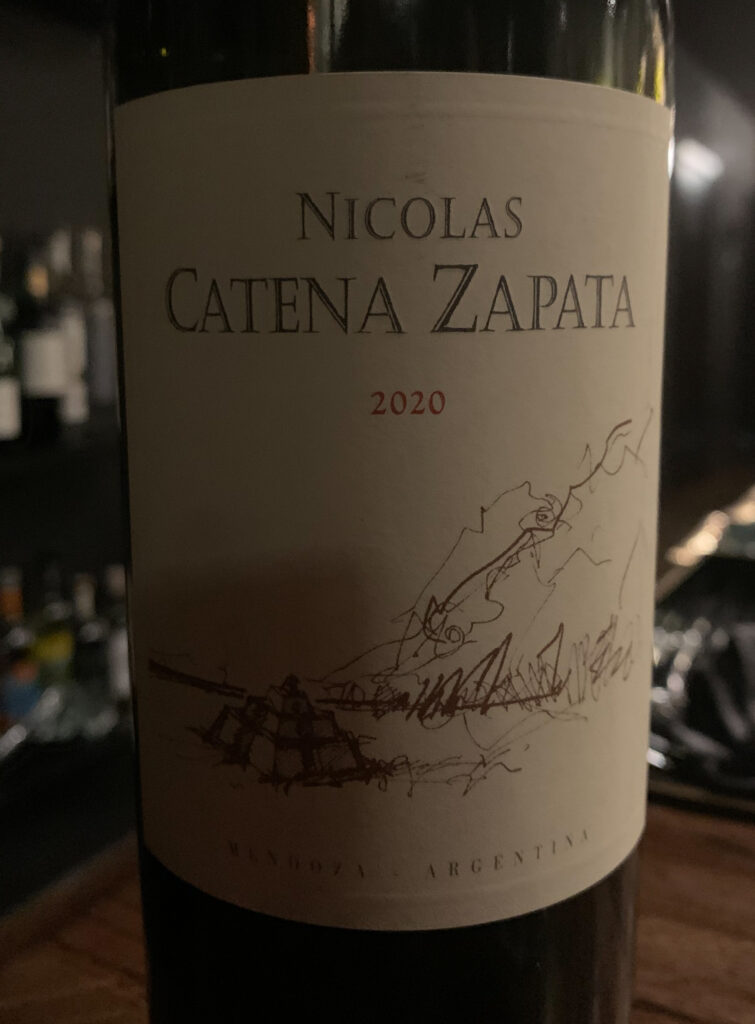

- 2020 Bodega Catena Zapata “Nicolas” Mendoza [54% Cabernet Sauvignon / 25% Cabernet Franc / 21% Merlot]

- 2020 Bodega Fallabrino “Alcyone” Atlántida [100% Tannat]

Here, a sense of variety and education still exists alongside a bit more star power drawn from producers like Chacra and Catena Zapata. However, at $165, the value proposition becomes a bit hazier. The wines, indeed, are better (reflecting retail prices that range from $27-$120 with an average price of $69.85) but, due to the youth of the concept, lack age or any particular rarity. Certainly, you enjoyed how they tasted: the Chardonnay/Pinot Noir blend sparkler, Mexican Chenin Blanc, Riesling-like Torrontés, Burgundian Chardonnay, whole-cluster/oak-aged Cinsault, Bordeaux blend, and Chinato/Marsala-inspired dessert wine touch on so many styles that a lover of the Old World would recognize. However, most guests would be served just as well by the entry-level novelty of the “Standard Pairing” unless they really, really want to splurge. To that point, one does get to taste the two most expensive bottles on the restaurant’s list (i.e., the “Chacra” and the “Nicolas”), but, personally, you would be happier spending $70 less (than the cost of two “Reserve” pairings) on a full bottle of the former. Perhaps single diners can get a bit more utility out of paying the premium?

It should also be noted that Ribando is working more as a consultant than a floor somm here, and, as a consequence, you have not seen him at the restaurant. There is nothing wrong with this in theory (especially if it means that restaurants have access to superior curation without the same expenditure on labor), yet it means that the descriptions of the pairings fall on the server. In thit task, they do a good job of hitting the essential points. You cannot say you’ve really probed their knowledge beyond that. But, when it comes to learning about Latin American wine, a server that has been trained and scripted by a consultant (with myriad other tasks on their mind) will always provide a fundamentally different experience than a certified sommelier. You agree that it makes little sense for Cariño to employ the latter right now. Nonetheless, at a time when other restaurants are touting extensive South American wine lists with dedicated professionals on-site, presenting a similar thematic list (without the requisite accompanying expertise) loses some of its luster.

Moving beyond the pairings, you encounter five by-the-glass options embedded within the full bottle list:

- NV Bodega Tapiz Torrontés Extra Brut Luján de Cuyo ($13)

- 2019 Vinaltura Chenin Blanc Valle de Colón ($20)

- 2020 Pablo Fallabrino “Estival” Atlántida [60% Gewürztraminer / 30% Chardonnay / 10% Moscato Bianco] ($14)

- 2020 Pedro Parra y Familia “Soulpit” Itata [100% País] ($20)

- 2020 Aresti “Trisquel” Grand Reserva Carménère Curicó Valley ($15)

While these producers or grape varieties may not be immediately recognizable to most diners, the pricing feels fair: ranging from $13-$20 for a healthy pour (and harmonizing well with the cocktails priced from $15-$18 and beers priced from $7-$8). In this manner, drinkers of any predilection can imbibe their favorite beverage and get out the door without paying more than $20, $30, or $40 for a couple of drinks. Relative to a $190 or $210 menu price, in such an intimate space, that’s not a bad deal.

Plus, stylistically, the by-the-glass selections actually fit into popular categories: a crisp, dry sparkling; a clean, bright white; a lush, aromatic white; a precise, cherry-driven red; and a darker, more robust red (in that order). You trust the restaurant, despite not having a dedicated sommelier on the floor, can easily guide guests to the right choice for their palate given these rather pronounced differences in character. Doing so, the servers can still subtly educate diners without the same high stakes provided by the pricier pairings.

Nonetheless, when it comes to fine dining, you will always maintain that the bottle list reigns supreme. It signals the most about a restaurant’s ambitions and the role it wants wine—the king of all beverages—to play alongside its food. Superlative selections (married with fair pricing) showcase the sommelier’s talent and titillate knowledgeable consumers. Not only that, they honor the chef by placing their work in conversation with a kindred craft, practiced vintage after vintage at the total mercy of nature, looking to balance technique with the faithful representation of terroir.

The following are representative selections from Cariño’s bottle list:

Sparkling

- NV El Bajio Sparkling Brut Rosé Valle de Bernal ($80)

- NV Domaine Nico Brut Rosé Uco Valley ($99)

- NV Viña Aquitania “Sol de Sol” Brut Nature Malleco Valley ($170)

White

- 2021 Bodega Del Fin del Mundo Sauvignon Blanc Reserva Neuquén ($52)

- 2021 Gilmore Vermentino del Maule Loncomilla Valley ($52)

- 2020 Emevé “Isabella” Valle de Guadalupe [70% Chardonnay / 20% Sauvignon Blanc / 10% Viognier] ($68)

- 2023 Bodega Catena Zapata “White Clay” Luján de Cuyo [60% Semillón / 40% Chenin Blanc] ($77)

- 2020 El Enemigo Chardonnay Mendoza ($90)

- 2021 Viña Cobos “Viniculum” Chardonnay Mendoza ($110)

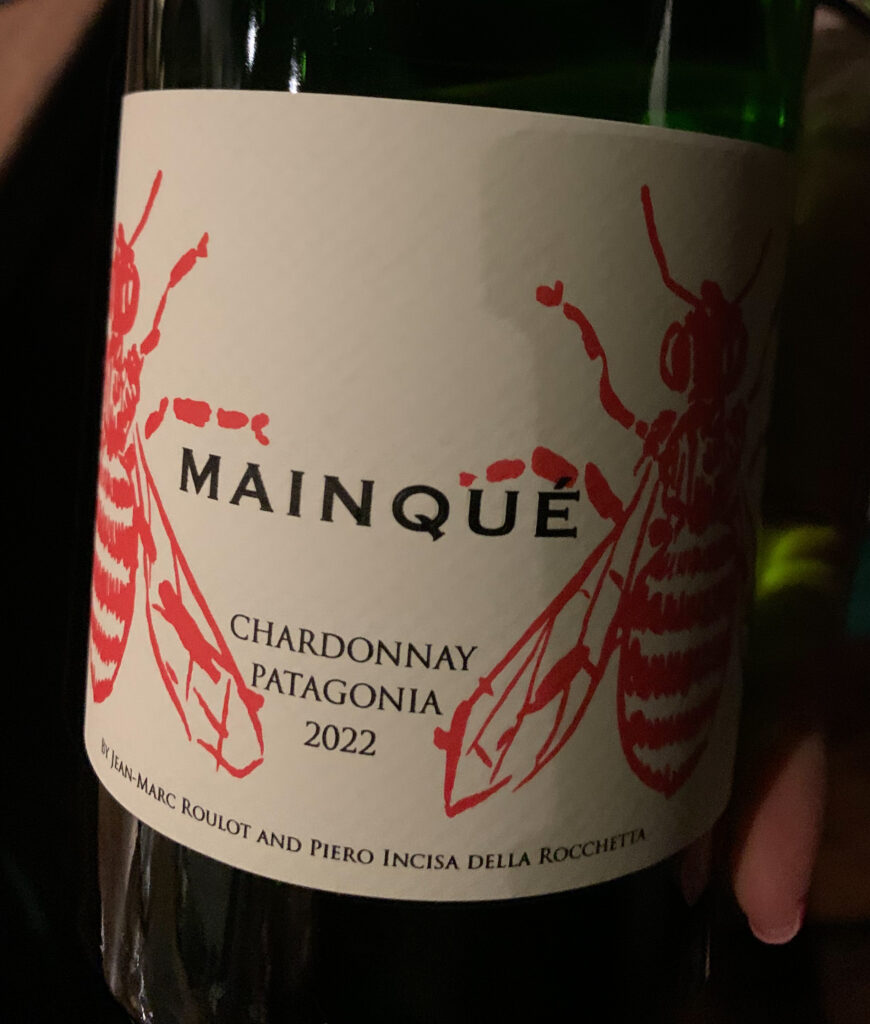

- 2022 Bodega Chacra “Mainqué” Chardonnay Patagonia ($134)

- 2019 El Enemigo “Gran Enemigo” Torrontés Mendoza ($155)

- 2021 Bodega Chacra “Chacra” Chardonnay Patagonia ($260)

Rosé

- 2022 La Casa Vieja Rosado Valle de Guadalupe ($72)

Red

- 2021 Domaine Nico “Grand Père” Pinot Noir Uco Valley ($72)

- 2022 Bichi “La Santa” San Lorenzo [100% Rosa del Perú] ($79)

- 2022 Bichi “Rosa” Valle de La Grulla [100% Mission] ($81)

- 2021 Pedro Parra y Familia “Trane” Cinsault Itata ($87)

- 2019 Altocedro Gran Reserva Malbec Mendoza ($99)

- NV Valle de Tintos Cabernet Sauvignon + Merlot Ensenada ($110)

- 2015 Viñas del Sol “Santos Brujos” Tempranillo Valle de Guadalupe ($118)

- 2021 Viña Cobos “Bramare” Malbec Luján de Cuyo ($130)

- 2013 Bodega Tapiz “Las Notas de Jean-Cluade” Uco Valley [95% Merlot / 2.5% Cabernet Franc / 2% Cabernet Sauvignon / 0.5% Petit Verdot] ($145)

- 2021 Pedro Parra y Familia “Miles” Cinsault Itata ($156)

- 2020 Bodega Catena Zapata “Nicolas” Mendoza ($220)

Starting with sparkling, you find two options (priced lower and higher than the método italiano Domaine Nico from the “Reserve” pairing) made using the méthode champenoise (that is, with secondary fermentation occurring in the bottle rather than in large tanks). Though more expensive than the Bodega Tapiz Extra Brut offered by the glass, the El Bajio Brut Rosé (made from a blend of Syrah and Macabeo in Mexico) and the “Sol de Sol” Brut Nature (made from a blend of Pinot Noir and Chardonnay in Chile) offer more of the yeasty, autolytic character some drinkers have come to expect from premium bubbly. Otherwise, the Tapiz and Nico remain good options for those seeking clean, fruity fizz.

The selection of whites, in turn, centers mostly on Chardonnay, that most popular of grapes, with a Sauvignon Blanc, a Vermentino, and two white blends for good measure. Argentina certainly dominates this category (with a couple options from Mexico and one from Chile providing variety), yet Mexico makes a stronger showing in the rosé / red section. There, the wines of Baja command the spotlight through biodynamic producers like Bichi, who work with more obscure varieties, and others (Valle de Tintos / Viñas del Sol) responsibly farming international favorites like Cabernet Sauvignon, Merlot, and Tempranillo. That being said, Pinot Noir (from Argentina), Cinsault (from Chile), Malbec (from Argentina), and Bordeaux blends (from Argentina) ensures all tastes are catered to. There are even a couple selections with some age!

Priced from $52 to $260 (with an average of $113.17 and a median of $99), this range of bottles is—in sum—pretty accessible in line with that “Standard Pairing” ($95) option. One can choose from seven smaller pours or five full glasses of a single wine for about an equivalent price, allowing a preference for variety or for a particular (grape) variety to guide the way. However, this equation is also influenced by the markups on the bottles (as best as the average customer can recognize them) and the corresponding value they, in isolation, may represent.

For example:

- 2021 Gilmore Vermentino del Maule Loncomilla Valley ($52 on the list, $15.99 at national retail)

- 2021 Domaine Nico “Grand Père” Pinot Noir Uco Valley ($72 on the list, $33.99 at national retail)

- 2023 Bodega Catena Zapata “White Clay” ($77 on the list, $24 at local retail)

- 2021 Pedro Parra y Familia “Trane” Cinsault Itata ($87 on the list, $42 at national retail)

- 2020 El Enemigo Chardonnay Mendoza ($90 on the list, $22.99 at local retail)

- 2021 Viña Cobos “Viniculum” Chardonnay Mendoza ($110 on the list, $46.99 at national retail)

- 2021 Viña Cobos “Bramare” Malbec Luján de Cuyo ($130 on the list, $44.95 at local retail)

- 2022 Bodega Chacra “Mainqué” Chardonnay Patagonia ($134 on the list, $59.95 at local retail)

- 2021 Pedro Parra y Familia “Miles” Cinsault Itata ($156 on the list, $75 at national retail)

- 2021 Bodega Chacra “Chacra” Chardonnay Patagonia ($260 on the list, $99 at local retail)

- 2020 Bodega Catena Zapata “Nicolas” Mendoza ($220 on the list, $119.99 at national retail)

On Cariño’s bottle list, the markups range from a mere 83% of the retail price (the Catena Zapata “Nicolas”) to 292% of the retail price (the El Enemigo Chardonnay). Certainly, the latter case—in which you are asked to spend close to four times what the wine is worth (to say nothing of the restaurant’s wholesale discount)—is worrying, yet the average markup is 160% with a median of 134% for this sample size. Further, though the cheaper wines do happen to be the ones on which the restaurant profits most, this is not exclusively the case (suggesting that the limited distribution of certain brands in certain markets may have something to do with the variation).

Overall, the list’s pricing seems rather fair despite the fact that the restaurant, possessing an information advantage over the customer, could (as Galit does) squeeze drinkers for more. When you consider the range of grape varieties offered (both popular and obscure) and number of wines coming in below $100 (or even $75), this makes for a particularly friendly selection in the rarefied world of fine dining.

More critically, you do note a litany of misspellings and missing accent marks (e.g., Atlántida, Bramare, Curicó, Emevé, Estival, Lurton, Neuquén, Querétaro, Torrontés, Valle de Colón, Viñas) throughout the document along with missing producer and appellation information in some cases as well. Of course, these are nitpicks—but also the kind of details Cariño should get right if they wish to foster respect for Latin American wine.

You also will admit that you would prefer (as at Topolobampo) that these New World wines were intermingled with thoughtful selections from the Old World. However, you can accept the fact that this would complicate the list (thematically) and unnecessarily sap the restaurant’s resources for the sake of appealing to a clientele that might not (yet) exist. To be fair, the Chacra and Catena Zapata offerings do look to satisfy customers with that kind of hankering. Plus, Fenton has stated that corkage is allowed for a fee in the $25-$35 range (you cannot confirm the final decision) with the common courtesy of waiving the amount for those purchasing bottles or pairings. This allowance, which is again fairly priced for fine dining, very easily allows oenophiles to enjoy exactly what they’d like.

In the final analysis, Cariño (with the help of Soto and Ribando) can claim a beverage program of great boldness, depth, and value. The restaurant has—impressively enough—done so from the very moment of opening, treating its customers to a generous array of options that suit all kinds of palates and pocketbooks. To you, a cocktail or agua fresca followed by a bottle of wine or pairing (plus, should the mood strike, corkage) makes for a pretty great evening. The degree of flexibility (when it comes to cocktails) and education (when it comes to Latin American wine) does show some room for growth, but this is a great start. It forms a stellar foundation on which Fenton’s menu (to say nothing of the chef’s personality) can shine, and you look forward to seeing the program’s development as the concept comes into its own.

Finally, with your drink order settled, the show begins.

To welcome guests in, Fenton strikes a playful note, serving a sizable strip of “Chicharrón” as a tactile, snackable starter. Chicagoans are no strangers to luxurious examples of these fried, puffed pork skins: The Aviary had their “Crispy Pork Skin” (with salt and vinegar, spiced corn) on the menu for quite some time, and Bazaar Meat offered a “Super-Giant Pork-Skin Chicharrón” (with Greek yogurt, za’atar spices) for a moment too. With these examples now gone, Cariño’s version—every bit as towering as its predecessors—solely benefits from its novelty value (while, more fundamentally, tapping into diners’ core nostalgia for the humble rinds).

The chef proudly describes his process for preparing the skin, which involves drying the ingredient overnight and carefully trimming it of all fat. Upon being fried, the chicharrón is rigid and airy with a delicate, uniform crunch that ranks—texturally—among the very best examples of the form. (You recall The Aviary’s iteration, pumped out in such large numbers, could be prone to curling in on itself and displaying an unpleasant, overly hardened quality in certain spots.) Presented, rather rustically (as it was at Brass Heart), on a tree branch at first (later substituted for a wooden cylinder that more effectively catches the crumbs), the crisp pork skin is primarily defined by its accompaniments.