After a brief interlude (during which you explored Christian Hunter’s exciting work at Atelier), the time is ripe to return to the art of omakase. The growth of Chicago’s sushi scene (whose longer history you may find discussed at the start of this article) has not let up. In fact, with the opening of Lettuce Entertain You’s Miru in late May, the genre may be approaching a critical mass.

Yes, openings like Japonais, Juno, Momotaro, and Nobu were consequential in certain neighborhoods during certain eras. They inched the appreciation of raw fish and rice (adulterated to varying degrees) toward the Midwestern mainstream. But placing a 460-seat (inside and outside combined) “all-day Japanese restaurant” at the heart of Jeanne Gang’s newly completed St. Regis Chicago (the 11th tallest building in the United States and the tallest in the world designed by a woman) signals something more. The $39 “Deluxe California Roll” (with caviar, king crab, avocado, and cucumber) slung from the 11th-floor dining room reflects a target population that has not bid farewell to old favorites but is now prepared to pay for their premiumization. The “San – 36 Pieces” ($190) selection of nigiri, sashimi, and hosomaki announces that you no longer need to venture into the bowels of Sushi-san to get LEYE’s take on an omakase. In fact, you can enjoy the culinary equivalent—sans the performance—tableside while looking out at Navy Pier.

According to the staff (and no doubt in keeping with the St. Regis’s luxurious brand image), Miru is not looking to attract foot traffic from the tourists that flow up and down Michigan Avenue just a couple blocks to the west. That would lead you to believe that the concept is conceived as something of a haven for the hotel’s guests (who, unless they are willing to make a trek to River North, find themselves rather starved of quality dining options in the immediate area). But you must also consider The Residences at The St. Regis Chicago: “Chicago’s Best Address. Luxurious on every level. Meticulous in every detail.” Yes, people actually live here (and within the larger master-planned Lakeshore East community). They possess some of the priciest real estate in the city and, by all accounts, have already warmed to the idea of having fine sake and sashimi right within reach.

Of course, this is not a Miru review, and there will likely never be one (though your first experience there totally surpassed expectations across just about every dimension). Rather, LEYE’s newest opening—soon to be followed by Evan Funke’s “Tuscan steakhouse” Tre Dita—affirms that high-end Japanese dining has a home outside of the West Loop. The concept’s menu, while not exclusively made up of sushi, makes fish and rice (in all their various guises) the centerpiece. Here, as is already true elsewhere, it firmly establishes them as pillars of New Luxury, the kind of comestibles that the city’s well-heeled travelers and residents are happy to engorge themselves on day and night. Thus, there is no longer any pretense involved, no undercurrent of exoticism that marks the form as a particularly trendy kind of novelty. Sushi is now simply a natural fit. It is the kind of cuisine patrons of Chicago’s most luxurious new rooftop are expected to like—and that all those who look to ape their perceived status will have to learn to appreciate too.

Miru extricates the “Nobu scene” from that brand’s absurd West Loop hotel and places it snugly on the Chicago River. Knowing that prime views and a feeling of exclusivity are like catnip to conspicuous consumers, the restaurant need only bide its time. The crowds that perpetually pack the Aba rooftop and jostle for spots on RPM Seafood’s balcony are sure to come and make themselves at home. Attracted by the space (and each other), they will then—through osmosis—find themselves acclimating to a higher caliber of sushi. They will learn to expect (and maybe even seek) more in terms of ingredient quality and finesse. In this manner, Miru is poised to inject Japanese luxury into the mainstream of the city’s dining culture with that gentle LEYE touch. It may very well form the capstone, after many decades and misstarts surrounding the craft, that heralds how sushi has found a permanent home here. Perhaps not as the food of the masses, but of a cultural elite that operates (and appeals to those) outside the ”foodie” influencer paradigm. In terms of mimetic power, this is the only audience that matters.

As Miru constructs and expands a higher appreciation of sushi within its sprawling setting, the restaurant’s rivals (other large concepts offering rolls and vibes) seem set to suffer from “death in the middle.” They lack the fancy Studio Gang setting, the pristine views, the all-day appeal, and that magic LEYE touch of hospitality and value. They quickly become—especially since your average consumer is not equipped to judge small differences in technique and ingredient quality—inferior substitutions for the place everyone is clamoring to get into. They thus fade into their neighborhood niches but will never quite recover their original buzz.

Yet, in the shadow of Miru, the dedicated omakase is set to thrive. Intimate and chef-driven, personal in a way that is antithetical to the St. Regis’s grand social scene, these concepts will shine more brightly at the opposite pole of the sushi marketplace. They are not poor substitutions pursuing the same broad appeal, but singular experiences awaiting those who get a taste of the craft and sincerely want to indulge in it at a higher level. LEYE may not exactly be building a direct pipeline from Miru to places like Kyōten, Mako, or Yume when you consider how hard it is to outdo the riverside setting. However, by fostering sushi’s perception as a rarefied luxury good associated with beautiful views and beautiful people, the group creates an environment where some of the money reserved for classic expressions of fine dining may be directed toward omakases that promise an even more refined take on something that is now familiar. In this manner, Miru’s success could very well mark a new frontier for sushi connoisseurship in Chicago.

Such a reality—and the influx of new omakase aficionados it might spell—prompts a need for some richer analysis regarding what all the various chefs at the city’s many counters have to offer. Chicago’s “professional critics,” surely, cannot be trusted to admit that nearly all these establishments are fundamentally selling their customers short by crafting nigiri in an assembly-line style (rather than shaping and serving pieces one by one). That leads you, after putting Mako, Kyōten, The Omakase Room, and Sushi by Scratch Restaurants through their paces, to take aim at another notable establishment. It is one, in truth, that has surprised you with the distinctiveness of its approach and the charm of its setting.

Yes, you must first freely admit that you typically show little interest in pop-ups. Honestly, at this point, your feelings toward them actually approach disdain. Some rare few, surely, go all the way: CLAUDIA, Elizabeth, and (the now infamous) 42 Grams successfully parlayed limited engagements into Michelin stars. And other craftspeople, especially in this post-pandemic era, have used them to sidestep traditional barriers of entry in creating businesses that sustain themselves and fuel their passions. Pop-ups, no doubt, form the vanguard of the democratization of fine dining and the very redefinition of what kind of dining should even qualify as “fine.” You certainly respect the manner in which they enrich a city’s gustatory landscape—and you freely reap the rewards when (or if) they come of age—but you are tired of beta testing other people’s dreams.

This disdain, perhaps, is directed more at pop-up tasting menus and “experiences” than the humble cooks sharing their take on barbecue—or, say, superb Vietnamese-Guatemalan fare—from temporary homes without the slightest bit of pretense. Slinging some singular form of comfort food at a bar or event space represents a clear victory for consumer choice and education. It brings something new and exciting to a place that might otherwise hold little appeal. But shoehorning tweezer food into some unequipped, understaffed place and invoking the whole idea of “chef as artist” really rubs you the wrong way, for it so often represents a clear compromise on what makes fine dining special.

You are not talking about superfluous bells and whistles like candlelight, white tablecloths, or fine crystal. Rather, a pop-up’s inherent impermanence often excuses an overarching lack of ambiance. It precludes the cultivation of an experienced front-of-house team that has learned how to make patrons feel at home. And it almost certainly denies the presence of any robust beverage program. Pop-ups reduce the tasting menu form to a carefully choreographed set of recipes when, at its best, this structure operates only as a vehicle for a larger, dynamic creative process that permeates every inch of a restaurant. These fleeting flashes of culinary talent—BYOB affairs enjoyed communally alongside the most detestable “foodies” imaginable—may hold some novelty appeal. Yet they totally miss the sense of depth and discovery that characterizes establishments that have laid down roots and really come to embody the local terroir. Pop-ups reliably fail to deliver the kind of transcendent emotion, drawn from the deep human connections that form during a perfectly curated evening, that makes hospitality life-affirming.

So, commensurate with the kind of writing you do, pop-ups just don’t make the cut. You crave fully-fledged concepts that you can swallow whole and approach holistically. You devote your time to restaurants that engage the mainstream consumer with something more than mere food. And, thus, you ignore places—places like Jinsei Motto—even when they are firmly located in your backyard.

An omakase situated inside of a distillery, assumedly paired with what was being made on-site, always sounded like a headache waiting to happen. Delicate pieces of fish and rice had seemingly nothing to do with high-ABV beverages. Gleaming metal stills sounded diametrically opposed to subdued wooden tones of a sushi counter. But Jinsei Motto not only survived in the space but persisted. And when Julia Momose (of Kumiko) gave the restaurant her stamp of approval, it felt like time to pay attention.

Jinsei Motto’s story rests with co-owners Patrick Bouaphanh and Andrew Choi, who met at Sushi Dokku (which just celebrated its 10th anniversary on Randolph Restaurant Row this year) in 2015. Choi had just moved to Chicago from Maryland and took his first job in the industry (having previously earned a degree in kinesiology) bussing tables and doing to-go orders before quickly becoming a bartender there. Bouaphanh was working as a nigiri chef at the restaurant after having left his office job to pursue a dream of entering the sushi industry and having cut his teeth—for about a year—practicing the craft at supermarket chain Mariano’s. In those roles, the two men worked side by side and became fast friends.

Dokku, looking back at the year and a half they spent there, is where the future Jinsei Motto honchos developed their respective skillsets and first encountered the kind of familial restaurant culture they would later look to establish at their own business. However, as it happens, both Bouaphanh and Choi were fired from the establishment after being caught drinking on the job (a decision they, now restaurant owners in their own right, do not feel bitter about).

Bouaphanh would make his way to Union Sushi + Barbecue Bar in River North while Choi ended up at Bohemian House. The latter found his experience “awful” and joined his friend at Union as a server after less than half a year. Nonetheless, Choi felt unfulfilled by the industry, admitting it was “sucking all the life” out of him, and left to work in a different field. These feelings of satisfaction persisted and reached a nadir with the death of Kobe Bryant (an important source of personal inspiration) in January of 2020. Choi found the inner strength he needed to move forward and took a bartending job at Galit. However, after only two weeks there, the pandemic struck.

Bouaphanh, in his own right, had made his way from Union to Sushi-san during that time and stayed on through the start of the pandemic. When the lockdown happened, the chef hosted Choi at his house in Pilsen. They got to know Bouaphanh’s neighbor, Tony Frausto, over the course of the summer: a longtime bar manager at Girl & the Goat and head trainer for Boka Restaurant Group who had just taken the director of operations role at CH Distillery (in March of 2020) after a sojourn in Colorado.

Choi came to learn that LEYE was cutting salaries and overworking its employees during the pandemic (despite record profits) and urged Bouaphanh to leave Sushi-san so that they could start their own thing. Inspired by Tony Robbins and the thought of there being opportunity in adversity, the two friends figured that they had a singular chance—while restaurants are closing and diners are looking for new things—to grab people’s attention.

They started Jinsei Motto (“more life”) as a “delivery-only operation” working out of ghost kitchens. Frausto, Bouaphanh’s neighbor, caught wind of the venture and invited them to do a pop-up at CH Distillery in October of 2020. With the establishment’s usual kitchen operations closed that evening, the duo served hand rolls and made the acquaintance of Tremaine Atkinson, who co-founded CH in 2013. He liked Jinsei Motto’s food and the attitude of its owners. With urging from Frausto, Bouaphanh and Choi reached out to Atkinson and inquired about partnering on a more consistent basis. The distillery was not using its back room (operations having been moved to a separate warehouse though the equipment remains), nor was it renting the space out for private parties or events. As long as Bouaphanh and Choi got along with Frausto, the opportunity was theirs, and Jinsei Motto—then lacking any capital for a brick and mortar—fell into the “goldmine” of a dedicated home that required minimal overhead.

Operations began in earnest with Bouaphanh and Choi primarily focusing on to-go orders (of which 15% of sales were given to CH). The Jinsei Motto owners admit that the distillery “coddled” them at first through periods of low sales, with the establishment’s existing kitchen continuing to serve its own menu. That included, in its time, bar fare like “Pretzel Bites,” “Nachos,” “Grilled Cheese,” “Steak Tacos,” a burger, and a selection of cheese and charcuterie. Reconciling these two visions was tricky at first, as Bouaphanh and Choi not only had to teach their coworkers about Japanese terms and ingredients but build an efficient space for their operation within the building. However, by the middle of 2021, Jinsei Motto’s sushi had totally displaced CH’s original bar menu. According to the owners, that was never the goal. But people increasingly came for their food, and the distillery struggled to find a chef to execute the other fare (with Frausto often having to go on the line to cook burgers).

Bouaphanh and Choi had been given total freedom to execute their vision from the start, but they had also prepared to take this next step. The latter would direct the restaurant’s front of house, and the former would run the back of house while Frausto would handle all beverage and the overall operation of the front bar/distillery area. Though Jinsei Motto operates as its own entity (being in charge of its own ingredient ordering for example), the co-owners say there is really no difference between the CH and Jinsei Motto brands at this point. The nature of their profit-sharing has changed from that original 15%, but they do not pay rent. Likewise, Bouaphanh has installed a ”handpicked” team for the back of house (while the distillery does the hiring for the front).

Over time, CH’s clientele would develop from “people who wanted good bar food and a couple drinks” to “people who really wanted an experience and to eat.” The menu, likewise, expanded to include “Starters” (like miso soup, crispy tuna bites, shishito peppers), “Nigiri/Sashimi,” “Classic Maki,” “JM Maki,” and “Dessert” (mochi ice cream) alongside “Setto” (sets of nigiri and sashimi) and a 14-course “Table Side Omakase” for $130. Thus, the distillery became a “destination spot” with—thanks to the surroundings—a degree of “fearful expectation” that “really wows people.” Bouaphanh and Choi would bring on executive chef Eric Blank to help manage the menu during this time. And, in November of 2021, Jinsei Motto would announce the construction of a dedicated omakase bar at the distillery in fulfilment of the concept’s original vision. The co-owners, now thoroughly at home within CH, would term it “a legitimate platform to showcase our food.”

In March of 2022, the counter would open, and Jinsei Motto would be named “our new favorite sushi bar” by Chicago in a feature that would also see the restaurant named the fifth best new restaurant of 2022 (behind Sochi Saigonese Kitchen, Dear Margaret, Ever, and Kasama). The piece would praise “an approach we wish more locals would emulate: Buy great fish at the source, cut it with care, season it with delicacy, and serve it at the right temperature vis-à-vis the rice. No truffle-oil funny business on the nigiri.” Bouaphanh’s travels to Japan would also be noted.

Later in March, Jinsei Motto would be named one of Michelin’s 23 “New Discoveries” in Chicago. This designation, in truth, only really serves to expand Bibendum’s brand and bolster its relevance without the Guide necessarily having to commit to handing out any actual awards. Some of these “new discoveries” would go to receive actual honors, but Jinsei Motto would not receive a Michelin Plate, a Bib Gourmand, or any stars that year. Still, especially with how close this listing was to the opening of the sushi counter, this should not be read as an indictment of the restaurant’s quality. Rather, it demonstrates that Bouaphanh and Choi (less than two years after their first pop-up) are on Bibendum’s radar, and the Guide would go on to praise Jinsei Motto as a “lovely little jewel” serving “one delicious bite after another.”

In August of 2022, as part of its “Chicago’s Sushi New Wave” feature, Chicago would again praise Jinsei Motto. The restaurant would be named one of “5 Omakase Spots You Need to Know Now” (being listed after Kyōten, Yume, and Mako but before Sushi Suite 202), garnering praise for “the best luxuries, such as otoro, wagyu, and sparkling fresh uni” and “unusual” bites like “sweet, firm white-fleshed beltfish.” Bouaphanh and Choi would also be featured in a “Know Your Sushi Chef” article (as “The Up-and-Comers”) alongside Otto Phan (“The Sushi Showboat”) and Shigeru Kitano and Kaze Chan (“The Sushi Masters”). There, it was noted that the duo “have traveled to Korea and Japan together” and that they want customers “to be relaxed, but still get the top tier” when dining with them.

Things would remain quiet through the rest of the year, and, in March of 2023, Jinsei Motto would announce the beginning of lunch service. Surely, being able to sustain these additional hours of operation signaled that the restaurant’s popularity continued to grow. However, buried in the same article were a couple more interesting tidbits. First, that Bouaphanh and Choi “source Japanese fish from Toyosu Market…twice weekly” (something that had likely been going on for a while but was not quite stated explicitly). Second, and more importantly, that the restaurant had “set up a new fish aging refrigerator in the dining room—one of the first in Chicago.”

This particular system, known by the brand name DRYAGER, can cost from $10,000-$15,000 per unit and may typically be seen holding beef and pork at places like Publican Quality Meats. However, its application to sushi by chefs like Liwei Liao has uncovered a new frontier of flavor. The general idea of aging fish—typically signified by the edomae label—is nothing new, but it is known as “an extremely laborious process: carefully applying preservative ingredients to the fish such as salt and vinegar, meticulously controlling moisture and temperature of the environment, relentlessly checking the conditions for the right timing to stop aging, which widely varies depending on the type of fish and each catch.” By comparison, the DRYAGER offers impeccable hygiene and a degree of control that allows chefs to push this process to extremes of texture and flavor that were never before possible on such a large scale. Kyōten, though guests would never know it, has been using this technology for well over a year. With its own adoption of the DRYAGER (and, according to the staff, additional fridges to come), Jinsei Motto has shown a willingness to invest even more in their craft. Even after years of success without it, this aged fish now represents one of the most distinguishing features of the restaurant (and one that will prove highly salient throughout your review).

In April of 2023, Jinsei Motto would be named runner-up in the “Best New Restaurant” category of the Chicago Tribune’s “Readers’ Choice Food Awards” (behind Flippin Flavors). In May, the restaurant would feature in a Crain’s Chicago Business article titled “We visited 8 of the hottest new restaurants in Chicago. Here’s the verdict on each.” There, it would be praised for its “excellent” lunch, the “six-day[-aged] kampachi and a seven-day[-aged] sawada,” and a “How did you know about this place?” factor “even for Chicago-based guests.”

This amounts to all the media attention Jinsei Motto has received in its short ride toward the top of Chicago’s omakase scene. Nonetheless, considering the restaurant’s counter has only been open for a little more than a year and the DRYAGER has only been in place for a few months, now seems like the right time to really evaluate Bouaphanh and Choi’s work. Few sushi chefs, other than Otto Phan himself (who, you might remember, started off in a trailer), have undergone such stratospheric growth. And, from these more unorthodox paths to success, you often find the most singular and rewarding perspectives on a craft that more established professionals—benefitting from far greater investment—approach without the slightest bit of imagination.

You have visited Jinsei Motto’s omakase a total of three times, spanning a period from March to May of 2023. As always, you will condense the sum of your experiences into one cohesive narrative.

With that said, let us begin.

CH Distillery sits in a subdued section of West Loop that is technically called “West Loop Gate.” However, you like to think of it as part of an extended Randolph Restaurant Row that, in line with your rather generous interpretation of its boundaries, begins just east of the river with Bar Mar/Bazaar Meat and Beatnik. (You would extend this definition even further, past the Thompson Center and toward Millennium Park, but for a lack of restaurant density.) Yes, over the Randolph Street Bridge, under Ogilvie, and past the French Market, CH Distillery is the first to welcome you into a wonderland of restaurants.

The establishment is on the ground floor of a building that is also home to the elaborate awnings and greenery of Alla Vita. Proxi can be found across the street (with big brother and fine dining stalwart Sepia behind it). A bit further west, you encounter avec and the dearly departed Blackbird. Should you continue over I-90, the options are nearly endless until you reach the Row’s terminus all the way down on Elske’s block. But, walking just north of the distillery, you may also find hallowed places such as Oriole and Kumiko.

Most consequentially, CH Distillery rests only a few blocks away from Chicago’s only Michelin-starred sushi concepts: Omakase Yume and Mako. Should you venture even further north, you might come across Sushi by Scratch Restaurants. And who can forget behemoths like Momotaro and Nobu that are also down the way? Jinsei Motto, unquestionably, is in the belly of the beast. Bouaphanh and Choi do not benefit from being the only good source of raw fish and rice in their neighborhood (like Kyōten and its new next-door counterpart or, perhaps, the aforementioned Miru). Rather, they are competing with many of the city’s finest examples of the genre and, more generally, with many of its most popular restaurants altogether.

Of course, it helps to have a patron like CH to rely on, and that is what would-be customers are destined to notice first. The distillery’s signage is rendered in sleek tones of silver and blue (mimicking, with its axis design, the look of the brand’s product packaging). That former color, likewise, matches the shining metal of the various stills and tanks—now out of use, as you have already mentioned, but eminently visible through one front window and a half dozen that run down an alley along the side of the building. During patio season, customers may spy umbrellas boasting the Jeppson’s Malört logo, a product the rights to which CH acquired from Patricia Gabelick (who had been producing the liqueur in Florida). They may also, when the weather is right, peer through a long horizontal window that opens up to transmit some of the energy from the distillery’s bar. A sandwich board, for good measure, touts happy hour deals while, affixed to the side of the door, Jinsei Motto’s presence is signaled in a modest font.

Above that, to be fair, a neon sign advertises “SUSHI. OMAKASE. SAKE.” Yet it is hard, at first, to reconcile exactly what is going on here. Dodging throngs of after-work imbibers (some of which flock to the distillery in groups numbering as many as a dozen), you maneuver your way across the sidewalk, past the patio, and through the single door marked CH. A brief pause in the vestibule offers you a perfect chance to ogle the stills. But, without much of a delay, you press onward—beyond another door—and find yourself face to face with the host stand at the front of the bar proper. A member of the staff stands ready with a cheery greeting and a tablet.

While, as a neighborhood distillery, CH always welcomes walk-ins at its barstools and outside, the remainder of the space is portioned out via the reservation system. Guests may choose to book within the “CH Cocktail Lounge,” a collection of high-top tables and low-top banquettes situated surrounding the bartop within this front room. Or, they may select the “Jinsei Motto Backroom,” a comparably isolated area that functions a bit more as a dedicated “dining room.” When booking at 5:30 PM or 7:45 PM, you are also given the choice of the “Omakase Bar” counter seating that is also located within the back room. This option corresponds with Jinsei Motto’s “19-Course Omakase” offering (also accessible under the “Experiences” heading) and demands a $100 per person deposit. However, in practice, customers may be invited to dine at the counter should the seats not totally sell out or, later in the evening, when the prescheduled meals have ceased.

You announce that you are here for the omakase (as just mentioning Jinsei Motto may signify that you are joining them for à la carte) and provide your name. The host checks it against the tablet and invites you to have a seat at the bar while he goes to inquire if the chefs are ready to host you back at the counter. Typically, even if you arrive right before the omakase’s scheduled start time, CH provides you with enough of a reprieve to order a drink. However, while this may seem like a fringe benefit for the distillery, the bartenders are happy pouring nothing more than water once they hear you are only waiting there a moment before the start of your meal.

This gives you a chance to soak in a bit of the cocktail lounge setting: a cavelike space framed by concrete pillars with tiling and upholstery rendered in dark tones of gray. It sounds (and looks) a bit plain, but the wood paneling along the ceiling injects a bit of warmth (this choice of material referencing, perhaps, the barrel aging undergone by some spirits). Down from the surface, countless LED pendants hang, three to a row, along the perimeter of the bar. They shine so brightly that the countertop seems to glow, illuminating the text on the underside of the lounge’s menu.

Behind the bar, a couple of employees cater to the first ripple of thirsty patrons (that will grow into something more like a wave by the end of happy hour). They draw from shelves stocked with the entire CH family of products alongside some notable selections from Suntory and a token amount of beer and wine. Otherwise, the stainless-steel appliances that make up the back bar are bedecked with a seemingly endless amount of glassware. Both materials shine in the light, matching the glow of the bartop and drawing your eyes upward. They meet the sets of windows that run along the entirety of the wall and provide a prime view of the retired distillery. Later at night, the equipment may be bathed in blue light—a touch that lends the space an interesting aquarium-like feeling.

Following the bar toward the back wall, the segment devoted to beverage service yields to a small sushi-making area. There, a couple of cooks armed with knives, rice cookers, and cutting boards help prepare rolls and other small bites for customers. This is not the main counter (where guests can sit), and it is not the full kitchen (where some of the heavier lifting is done). However, it ensures that patrons dining in the cocktail lounge still feel some connection to the craft being practiced (an essential dimension of the experience, you think, when trusting someone with raw fish). All the way down, along the back wall itself, you find a sweeping illustration that showcases the distillation process (driving the point home for those who may have missed all the hulking metal equipment next door).

Overall, you do not think CH ever set out to win people over with its interior design. Rather, the cocktail lounge retains somewhat of a functional feeling (in line with the distillery equipment that still surrounds it) while remaining spacious and comfortable enough to confidently host guests. In a neighborhood that boasts such a high degree of investment from established hospitality players, this seeming lack of luxury actually reads positively as a sign of authenticity. CH is not a corporate concocted gastropub, but a real industrial space turned toward pouring drinks. It looks like a place you can happen across and feel pleasantly surprised by (a bit like how The Drop In plays host to Sushi by Scratch Restaurants) without promising the world when it comes to spatial cues or exclusivity. This ensures that Jinsei Motto’s presence still feels a bit surprising, but, just the same, it may actually help the cuisine reach Chicagoans who would otherwise never seek it out.

While waiting for your omakase on other occasions, you might—indeed—take the chance to enjoy a tipple and get to the heart of what makes this CH operation tick. That may include one of a dozen cocktails ($16 each) made using the distillery’s own peppercorn vodka, Key lime-infused gin, or coffee liqueur. You are partial to the bright and refreshing “Chi Tai” made with No Masters Rum, CH Rum, orgeat, orange liqueur, and a Malört float. Flights featuring different expressions of the distillery’s bourbon ($25), liqueurs ($20), limited edition ($23), and Malört ($20) offerings are also available.

Choi has clarified that CH’s prized Jeppson’s Malört is “not for the omakase” because he’s “not trying to ruin experiences,” yet the Jinsei Motto team will sometimes offer shots after the meal in order to show “love and appreciation for guests who are having fun and being genuine.” Still, when you are seated at the bar and the first piece of nigiri still seems (many) minutes away, it can be hard to resist. What better than a lightning strike of bitter grapefruit to invigorate your stomach ahead of a fish and rice feast?

You opt for the “Chicago Handshake” ($8), which juxtaposes the Malört with a can of Old Style—not quite an authentic Chicago beer, but one whose signs survive throughout the city as a “relic of 1970s industry.” Dwelling on the shot for a moment, the high/low contrast (ahead of that $175 sushi meal) is delicious. Oh, how smugly could any influencer use this moment to bolster their credentials before posting another banal assemblage of sushi. How coyly they could present themselves as appreciating the “everyman’s” conception of taste before conspicuously consuming the exact kind of meal such a person would (rightfully or wrongfully) detest. But that would be cultural slumming, and you fear that most of Malört’s cult appeal is drawn from a misplaced sense of pride.

Yes, the liqueur traces its history to the 1920s, when Carl Jeppson’s traditional Swedish-style bitters maintained its medicinal status thanks to a taste that convinced Prohibition authorities “nobody” would drink it “recreationally.” The product’s logo, likewise, stresses its connection to the Chicago of yesteryear by showcasing the “three-star” flag design utilized from 1933-1939. However, the brand freely admits that Malört did not transform “from a lesser-known spirit to a popular Chicago icon” until 2011, when Sam Mechling (with “no official connection” to the business) began promoting it “via comedic Twitter and Facebook posts.” Mechling, who today describes himself as “an experienced and intuitive brand architect,” would—as Director of Marketing—ultimately broker the sale of Carl Jeppson Company to CH and oversee a 1,200% growth in sales (through 2019).

Mechling would even design the “Chicago Handshake” itself. And, letting the combination wash over you, the effect is really not that bad. The Malört simply tastes like a poorly made amaro while the Old Style, once the shot’s opening burst of bitterness subsides, helps to round out the liqueur’s lackluster finish. Why, you must ask though, has the Windy City—one of the birthplaces of contemporary American wine appreciation—allowed itself to be defined by such a lackluster product? Malört, like most people say, certainly does not taste good, but it also does not taste nearly bad enough to form a rite of passage. No, the mythology surrounding the drink is totally contrived, and the ritualization of its appreciation obscures a nefarious subtext.

The thought that taking a shot of Malört inducts you into Chicago and its culture represents a total bastardization of the process through which community forms. Rather than laying down roots, assimilating, striking some singular balance between customs old and new, and then sharing those traditions with neighbors whose respect you have had to earn, the shot of Malört promises that anyone with a working gullet can feel a sense of belonging. But the bitter beverage, especially when paired with an Old Style, trades on the city’s working-class heritage while caricaturizing it. Malört paints the Chicago palates of yore as particularly unrefined, reducing alcohol consumption into a frivolous kind of dare that only celebrates one’s tolerance for disgust. Yes, it characterizes the broad-shouldered city as being made up of unapologetic drunkards who care nothing for taste—who even revel in their ability to negate the notion of “taste” altogether—so long as they get their fix. Glorifying this barfly sensibility is not only irresponsible, but it reflects a particularly deluded, inherently rather privileged kind of cultural slumming.

The empty kind of alcohol abuse that Malört symbolizes (and, through its ritualization, arguably encourages) somehow escapes attention. The brand has been embraced as a marker of Chicago identity even by those whom you would expect to beat the drum against such a naked fabrication of history for capitalistic purposes. Perhaps, in fact, that is its genius. The shot of Malört denies that you need to put in work to be a part of this community. It glosses over a history rooted in ethnic enclaves and slow, generational change. It invokes the spirit of the working-class melting pot only to dance on its grave. Knocking back a shot of Malört ignores the difficult—but essential—work required to learn to live together. Its fleeting bitterness puts forth the fantasy that one need only consume as the locals do to become accepted as one.

Yet it is nothing more than a false rite of passage for a rootless society that only knows how to identify with each other as consumers. It represents a sinister attempt to detach the notion of belonging from anything permanent, longstanding, or—to be honest—not immediately welcoming to an outsider. Under the guise of “tradition,” Malört prostitutes the city’s reputation and allows its flag to be flown by anyone. Some might paint this wide-ranging tolerance as a virtue, but tolerance is not acceptance. Acceptance cannot be bought for $5 a shot, and Chicagoans should rue that the city’s hard-fought character is being diluted by a brand whose famed product amounts to little more than a practical joke. Local pride comes from the preservation and perpetual improvement of native crafts, not the concoction of a brand narrative meant to turn some noxious beverage’s weakness into a strength. And just what is ethical about using “guerilla marketing” to target consumers with an alcohol they are destined not to savor?

Bitterness (gustatory and otherwise) subsiding, one of the servers arrives to retrieve your party. You close the tab (though the bartenders, unable to transfer the bill, are at least good about anticipating your departure), and they move any unfinished drinks onto a tray. The server leads you into a passageway situated opposite the bar, and the gray and metal tones of the cocktail lounge quickly fade away. The bathrooms, as it happens, are located here. But you are fixated more on the black wallpaper—painted with flowing waves of water, Japanese script, and an oni mask—cast in red neon light. The design beckons you forth down a hallway that feels increasingly like a back alley with each step. This is the liminal space where the cool blue of the distillery yields to the warmth of the forthcoming meal. At its end, under an emergency exit sign, an open doorway is obscured by a hanging piece of fabric (noren) with the Jinsei Motto logo. The server holds the cloth to the side and welcomes you to cross the threshold.

You find yourself, on the other side, still sequestered in a hallway. With just a few more paces and a turn around the corner, the passage opens up to reveal the full scope of the room that is situated behind the rear wall of the cocktail lounge. However, before catching that first sight of the restaurant proper, your eyes become fixated on what lies immediately ahead. Aligned dead center with the doorway, the DRYAGER unit glows in the distance. As you approach the end of the corridor, you get a good look: a half dozen fish carcasses strung down from the top rack with a few carefully wrapped fillets situated on separate trays. The scene is a bit bloody, and the empty stares of the seafood leave you feeling a touch of guilt. But oh, these fish look so pristine and plump. They have been sitting there, biding their time, and concentrating their flavors for the omakase to come. Observing this touchstone of the Jinsei Motto style firsthand is striking and highly rewarding.

With that, you turn the corner and finally enter the dining room. It is defined, at first glance, by many of the same details as the lounge: tones of gray and wood married with the shine of stainless steel. But, here, you find actual stacks of barrels alongside pipes, circuit breakers, knobs, dials, and blinking buttons. The vats and stills, bathed in blue light, are no longer ensconced behind windows but actually in the room with you. One particular vessel, situated closest to the seating area, displays dozens of colorful stickers. Yes, you are now in the heart of the (former) distillery, but it also feels like home. The two- and four-top tables are illuminated not by cold, industrial light but by the kind of stringed bulbs you’d find in someone’s backyard. The painted Japanese motifs that began back in the hallway reappear courtesy of a scene, rendered on a concrete beam, of a fisherman and his prey swept up in a whirlpool.

The room’s main fixture, nonetheless, stands just on the other side of the hallway from which you entered. Completed in March of 2022, Jinsei Motto’s counter lacks some of the production value you might find at Kyōten, Mako, The Omakase Room, or even Sushi by Scratch Restaurants. It is fashioned out wood that retains a bit of that unfinished DIY feel but is securely fitted to the wall and snugly fills its dedicated space. The portion of the counter that guests eat on, it should be said, possesses a nice lacquered coating. Likewise, apart from the aforementioned string bulbs running along the ceiling, the structure does support close to a dozen wooden light fixtures that stretch around the sushi bar’s perimeter and illuminate it like a stage.

Taking one of seven seats at the counter, you are greeted by personalized menus and a beverage list alongside tools of the trade like chopsticks and a platform onto which the chef places nigiri. There may be one or two figures behind the bar when you arrive, but they tend to keep busy for a bit and only offer a mild greeting. Meanwhile, your server introduces themself and goes about retrieving your preference of water. This gives you a chance, free from any other interaction, to look around a bit. Technically speaking, there is little to note: fridges, rice cookers, cutting boards, knives, blowtorches, wasabi graters, brushes, and an array of garnishes make up the usual weapons of war.

Yet, just a bit above eye level, the counter’s backdrop is defined by several sets of shelving. These ledges blend into the wall and house an overflowing assortment of greenery interspersed with the odd Air Jordan sneaker. The lower level holds bottles of Japanese whisky, cookbooks, a Mega Man figurine, and eclectic mixture of art—often referencing basketball with a particular focus on the Bulls and the Lakers (though one piece prominently features the text “Chicago Born and Raised”). Importantly, this shelving continues past the threshold of the counter and over some of the distillery equipment at the outer boundary of the dining room. Potted plants mingle with the string bulbs, high voltage signs, pipework, and vintage photos to craft a somewhat cobbled together—but ultimately captivating—aesthetic.

Yes, taken in sum, Jinsei Motto’s ambiance might lack some polish (you are reminded, perhaps, of Kyōten “1.0”), but the restaurant succeeds in conveying a distinct sense of personality. The easiest point of comparison may be Sushi by Scratch and its speakeasy design. There, Phillip Frankland Lee turned The Drop In’s unused basement space into a combined lounge and counter combo that looked tailormade for the building. The overall effect was successful, but it was really just a new iteration of the same aesthetic seen at the chain’s other locations. The details had little to do with Lee himself, who decamped after putting in two months behind the bar and seems unlikely to ever return. Thus, while pleasant on the surface, the restaurant really offered little depth at a visual level.

By comparison, Jinsei Motto benefits from having organically inserted itself into the CH space. The venture was not approached with Lee’s diabolical need to expand into every possible market, but it formed naturally as Bouaphanh, Choi, and Frausto’s partnership grew and came to put its stamp on the distillery. The concept, even with the construction of the counter, still benefits from the sense that it is hidden, or “popping up,” within an “authentic” Chicago distillery. However, the DRYAGER and the solidity of the sushi bar’s construction signal a certain permanence. Moreover, the bric-à-brac that lines the backdrop really distinguishes what the Jinsei Motto guys like: streetwear, street art, basketball, gaming, and their city. This might not improve your perception of the food per se, but—given the personal connection that lies at the heart of omakase—it provides a foundation from which an appreciation of shared interests may flow. At the very least, it marks Bouaphanh and Choi as owners with a distinct sense of self within a genre where many chefs do their best to express as little as possible.

Kyōten “2.0,” which combines luxurious finishes with bursts of Otto Phan’s own personality, still sets a high bar. Yet Jinsei Motto provides a refreshing counterpoint to places like Mako and The Omakase Room that reflect a high degree of planning and investment but very little soul. Yume, you think, benefits from the energy of its husband-and-wife dynamic even if it is not all that impressive aesthetically. However, B.K. Park and Kaze Chan preside over counters that ultimately communicate nothing. This starkness, when you are truly in the presence of a master chef, can be quite captivating. At Mako and The Omakase Room, it merely feels like a means to play things safe by offering a bland vision of “luxury” that demands little of those working the bar so long as other creature comforts are in place. This is all to say, Jinsei Motto feels singularly and irreplaceably like itself. Mako and The Omakase Room mimic a more “serious” sushi restaurant you might find in New York but fall short of the standard set there. They do not represent Chicago—its people and its own unique understanding of luxury—nearly as well as Bouaphanh, Choi, and Frausto do with a disarming sense of sincerity.

Settled into your spot at the counter, you now turn your attention to the beverage selection. While the aforementioned Jeppson’s products, Japanese whiskies, cocktails, and flights are still offered in the Jinsei Motto space, the restaurant’s program is defined by a surprisingly extensive selection of beer, sake, and wine. This represents, as far as CH is concerned, some real dedication to providing a great sushi experience beyond just supporting the needs of the distillery and its own product line. Plus, with Frausto guiding the selection, the list still offers an opportunity to assert the brand’s know-how with all things potable.

It is also worth noting that Jinsei Motto does not explicitly offer pairings like many of its competitors. There is, you suppose, a “Sake” flight ($26) customers can choose, but its constituents are unknown. Instead, the restaurant seems to encourage a conversational style of ordering rather than providing a turnkey solution. The staff will happily put together a series of four or five glasses of sake upon request, but approaching beverage curation in this fully bespoke manner should be applauded. It ensures that guests will only drink (and pay for) exactly what they want rather than being urged toward a one-size-fits-all approach that may offer dubious value.

At the entry level, you find a half dozen beers:

- Old Style, Lager ($5)

- Asahi, Japanese Lager ($7)

- Moody Tongue, Lychee IPA ($9)

- Hitachino Nest, White Ale ($12)

- Pipeworks, “Unicorns Aren’t Real,” IPA ($9)

- Montucky Cold Snack, Lager ($7)

Three cans of sake:

- Maki Sake, Junmai ($10)

- Heiwa Shuzou, “KID,” Junmai ($16)

- Bushido, “Way of the Warrior,” Ginjo Genshu ($18)

10 glasses of sake:

- Toko, “Divine Droplets,” Junmai Daiginjo ($24)

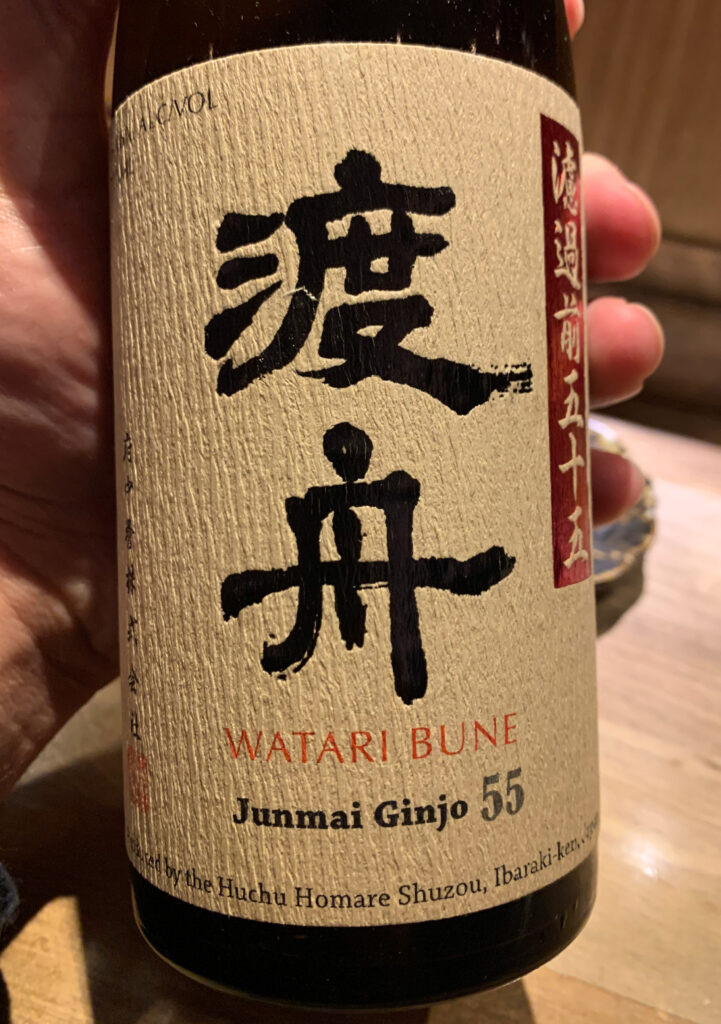

- Toko, “Ultraluxe,” Junmai Daiginjo Fukurotsuri ($39)

- Yuki No Bosha, “Cabin in the Snow,” Junmai Ginjo ($14)

- Tsukinowa Yoi-no-Tsuki, “Midnight Moon,” Daiginjo ($18)

- Fukucho, “Moon on the Water,” Junmai Ginjo ($19)

- Amabuki, “Gin no Kurenai,” Junmai ($22)

- Yuri Masamune, “Beautiful Lily,” Futsushu ($10)

- Yamada, “Everlasting Roots,” Tokubetsu Junmai ($15)

- Kanbara, “Bride of the Fox,” Junmai Ginjo ($17)

- Dassai, “45,” Junmai Daiginjo Nigori ($18)

And 12 glasses of wine to choose from:

- Poema, Cava Brut Rose ($11)

- Château Moncontour, Vouvray Brut ($12)

- Canard-Duchêne, Champagne Brut ($23)

- Casal Garcia, Vinho Verde ($10)

- Colomé Estate, Torrontés ($11)

- Barnard Griffin, Chardonnay ($12)

- Domaine du Fief Aux Dames, Muscadet Sèvre et Maine “Sur Lie” ($14)

- Barnard Griffin, Rosé of Sangiovese ($14)

- Jacques Dumont, Sauvignon Blanc ($16)

- Château Pey la Tour, Bordeaux ($12)

- Vignerons des Monts de Bourgogne, Bourgogne ($13)

- Bodega Norton, “1895 Coleccion,” Malbec ($16)

The name of the game, across each of these categories, is value and consumer choice. To start, Frausto has combined emblematic Japanese beers like Asahi and Hitachino Nest alongside local offerings from Moody Tongue and Pipeworks that, while proudly bitter, bring a harmonizing dose of citrus to the table. Likewise, while offering canned sake alongside such an extensive by-the-glass selection may seem like overkill, the “KID” and “Way of the Warrior” are both approachable, enjoyable choices that widen the overall number of options (and perhaps offer some capability to enjoy a drink with your takeout).

More principally, the full list of sakes is organized under helpful headings like “Crisp, Aromatic, Light” and “Dry, Umami, Bold” with an additional feature on four bottles from the Kojimaya Family: “One of the oldest active breweries in Japan. Located in the Yonezawa region of Yamagata, a city known for its warrior legacy.” Even more impressively, all of the selections are annotated with a set of three terms like “pineapple, violet, fennel,” “hibiscus, juniper, raspberry,” or “chestnut, sweet rice, melon.” Those who have read your article on these kinds of annotations will recognize that Jinsei Motto is following the best practice of solely pairing descriptive words together while avoiding expository and non-sequitur remarks. This information, along with those more general headers, are a clever way to help customers untangle the somewhat arcane nomenclature applied to various styles of sake. It provides, alongside conversing with the staff, a great avenue to educating oneself on the beverage by sampling several glasses and meditating on the provided tasting notes.

The wines offered by the glass, you must admit, are not all that distinguished in terms of producer. Nonetheless, they succeed in offering variety and value through a range of sparkling, white, and red options (almost all priced at $16 or lower) that tick all the boxes: Cava, Champagne, Chardonnay, Sauvignon Blanc, rosé, Pinot Noir, and even Bordeaux.

When it comes to bottles, eight sakes are offered exclusively in a larger format:

- Toko, “Sun Rise,” Junmai Ginjo ($105)

- Kojimaya, “Untitled,” Cedar Barrel Aged ($190)

- Kawatsuru, “Olive,” Junmai Ginjo ($90)

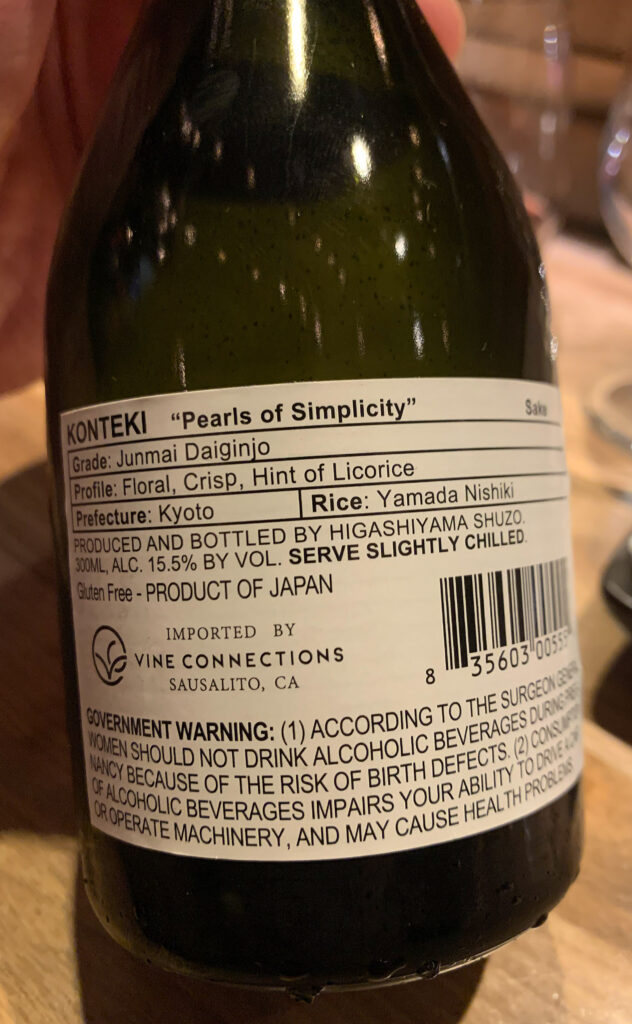

- Watari Bune, “Ferry Boat 55,” Junmai Ginjo ($105)

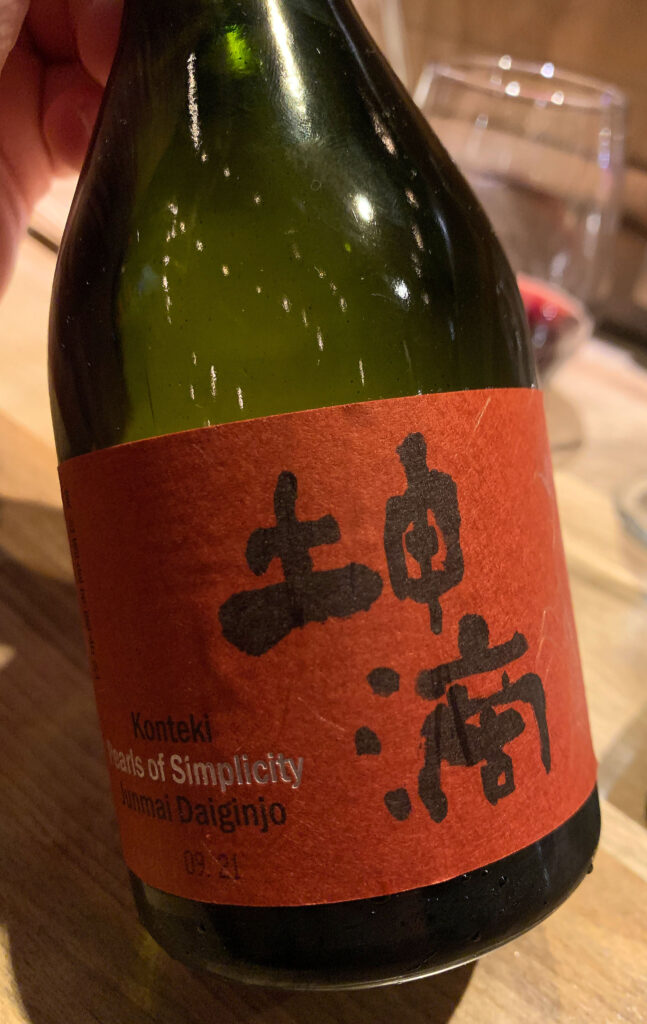

- Konteki, “Pearls of Simplicity,” Junmai Daiginjo ($130)

- Amabuki, “Strawberry,” Junmai Ginjo Nama ($87)

- Narutotai, “Drunken Snapper,” Ginjo Nama Genshu ($94)

- Mana 1751, “True Vision,” Yamahai Tokubetsu Jumai Muroka Genshu ($112)

Along with three wines:

- Charles Heidsieck, Champagne Brut Réserve ($120)

- Ken Wright Cellars, Willamette Valley Pinot Noir ($88)

- Argiano, Brunello di Montalcino ($185)

Most of the sakes offered by the bottle do not quite surpass the price of those offered by the glass (but still available in a larger size) by any crazy amount. Rather, the decision to restrict these selections to a larger format likely has to do with rarity, especially relative to styles that are already represented by the other choices. Once more, annotations like “banana peel, pineapple, melon” and “maple, black cherry, remarkably intense & concentrated” form an effective guide for consumers. And markups, it should be noted, tend to be about 2.5 times the bottle’s retail price across the board: a degree that feels high at first glance but accords with places like Yume (2.4 to 3 times retail price), Mako (1.5 to 2.3 times retail price), and The Omakase Room (1.5 to 2.4 times retail price).

The wine offered by the bottle, just like that offered by the glass, is not all that striking (especially when you consider that vintages are not even listed). Markups, too, range from 2 times retail price (for the Charles Heidsieck) to 3 times retail price (for the Ken Wright). But these are okay options for those demanding fermented grape juice despite the clear focus on sake. More importantly, you praise Jinsei Motto for allowing guests to bring their own wine without charging a corkage fee but with the understanding that you will support the CH beverage program in some capacity. This, for an oenophile, is as good as it gets and allows you to view the selection’s sense of variety and value as a good thing (for the entry-level customer) without feeling like connoisseurs are being forgotten (or, worse, punished).

In practice, you have enjoyed—depending on the size of your party—ordering one or two bottles of sake from Jinsei Motto while bringing one or two bottles of your own wine. The restaurant may lack some of the hyper-premium selections ($250-$895) seen at Mako or The Omakase Room, but the audience for such extravagant examples of the craft is rather small (and not exactly befitting the more casual distillery environment). Instead, you are happy to sample different sakes around the $100 as a complement to wines that match your exact tastes in a manner that few Chicago restaurants could ever hope to accomplish. Just the same, the beers and bevy of by-the-glass options offer a very friendly route to go for customers who are mainly there for the ride and just looking to enjoy the experience without being pushed to spend a sizeable sum on drinks.

With regard to beverage service, Frausto and his team do an admirable job of ensuring you get your money’s worth. Bottles are chilled and glasses are refilled without the slightest delay. Repeat customers, likewise, will find themselves welcomed back with a pour of this or that. There is not, given the lack of a formal pairing, quite as much of an opportunity to rhapsodize regarding particular bottles of sake. But Jinsei Motto (a bit like the Sushi by Scratch Restaurants “speakeasy” aesthetic) does not really encourage that kind of extended geeking out, and the menu itself (as already mentioned) provides enough fodder for newcomers to get some sense of the various styles.

Wine service suffers just a bit on account of the stemless glassware, so those planning to bring any particularly special vintage should consider transporting their own. Nonetheless, being used to serve sake of an appreciable price, the glasses certainly do not feel plasticky or cheap. They do a fine job expressing any good Champagne or Burgundy you might wish to enjoy from the cellar (still quite a nice treat considering the generous corkage policy) but should not be expected to reveal the full aromatic complexity of a truly fine wine. It is also worth mentioning that, on one occasion, the server handling the bottle of sparkling you brought left it in a chiller with the cage removed. Not fifteen seconds after walking away, the cork shot up toward the roof with a thunderous pop. Everyone in the room—chefs and other diners included—was rightfully a bit shocked, but the situation was recovered fairly gracefully. No one was blinded (and, more importantly, no Champagne was spilled), but this error is worth noting because you have observed it across the city and it is one of the few aspects of basic wine training that really works to prevent a totally needless tragedy.

Still, and with no hard feelings toward what only amounted to a bit of premeal fireworks, the service at Jinsei Motto is commendable. And that encompasses everything that goes on in the front of house (which, due to the presence of the chefs on the other side of the counter, mostly has to do with beverage but not exclusively). It also, necessarily, involves CH Distillery given that Frausto is in charge of staffing for the property. Nonetheless, the warm relations he maintains with Bouaphanh and Choi are evident as the two brands operate with total synergy. Each space, each bar (cocktails and sushi) is there to support the other without even a friendly sense of rivalry. Rather, Choi’s dream of building the kind of restaurant family he and Bouaphanh shared at Sushi Dokku has largely come true (even if the CH employees are technically stepsiblings).

This takes the form, from the moment you enter, of a pervading sense of ease. The distillery does not try to be something that it’s not, so the staff need not do so either. They welcome you in a subdued, sincere fashion that invites you to cozy up to the bar and stay a while. When it is revealed that you will be enjoying the omakase, the team’s excitement is palpable but in no way put on. Making your way to the Jinsei Motto counter, one member of the front of house introduces you to another, whom they say will be taking care of you. Settling into your seat in front of the chefs feels every bit as comfortable as posting up in the lounge. You are given more focused attention, perhaps, but with every bit of the same effortlessness and charm. There is no suffocating sense of seriousness—no forced, worshipful manner of appreciation—that you feel. Instead, the industrial setting, juxtaposed by the wooden counter and invigorated by the team, suggests a shared celebration craft—whatever form it takes—without any shred of pretension.

Yes, The Omakase Room has an admirable staff-to-guest ratio with all the bells and whistles a luxe LEYE property entails, but such a corporate culture always strikes you as being just a bit stiff. Mako and Yume even moreso (and without the same effusive kind of interactions undergirding every moment). Sushi by Scratch Restaurants does a better job of setting a festive mood, but the “performance” there begins to fall apart with subsequent visits (and especially with the founding chef’s departure from the “master of ceremonies” role). So only Kyōten, relying on its front-of-house jack-of-all-trades Jose, really strikes you as maintaining the right balance between attentiveness and earnestness. And Jinsei Motto, you think, is cut from the same cloth: good service executed in a relaxed manner that allows the guests to sit back, be themselves, and forge some meaningful connections with each other. Some might desire a tad more precision (and the same, to be fair, can be said about Kyōten in some moments), but, considering the (still nascent) level at which omakase is practiced in Chicago, you think focusing more on mechanics would provide diminishing returns.

This is all to say nothing of the chefs themselves—the real lifeblood of this kind of experience. However, you should mention that you never saw Bouaphanh or Choi during your first two visits to Jinsei Motto and only saw the former, fleetingly, near the end of your third. Typically, the lack of any chef-partner behind the counter (as is typical at Mako and Sushi by Scratch Restaurants) provokes a strong reaction from you. Given the fine degrees of technique that define top quality sushi—the subtleties of rice shaping and fish scoring that distinguish the best from the rest—not having your top craftsperson on the frontline seems like a betrayal. This rings especially true in a market like Chicago, where omakases rank as some of the city’s most expensive meals, but mainstream consumers lack the discernment to know what structural elements form the foundations of quality. No matter the concept, advertising the mastery of a chef-“artist” who is not actually in the kitchen feels like a bait and switch. When it comes to sushi, such a maneuver feels like an outright scam.

Nonetheless, Jinsei Motto’s social media and website design does not really put Bouaphanh or Choi at the forefront as the concept’s star attractions. Rather, the brand operates more as a singular entity and with reference to its partnership with CH. Thus, not knowing anything about the restaurant’s founders when you made those first two visits, you accepted that the chefs behind the counter were in charge. This ultimately helped you to evaluate their tableside manner and technique without the perception (subconscious or otherwise) that you were dealing with second-stringers.

On any given night at Jinsei Motto, your omakase may be served by chef Timmy Chen (who conducted your first meal meal) or Jamel Jones (who took charge of your subsequent two). The former chef cut his teeth making sushi at Mariano’s and, after that, spent close to five years at Sushi Dokku—experiences that mimic Bouaphanh’s own career quite well and mark him as part of the same restaurant family Choi praises so highly. Following that, Chen would also work at Nobu Chicago for two-and-a-half years before joining Jinsei Motto in November of 2022. The details of Jones’s career, by comparison, are less certain. However, it seems he has been making sushi for close to a decade (having worked for a crowd-pleasing concept in Cincinnati back in 2014).

Like Bouaphanh himself, Chen and Jones rank among the youngest itamae in town. Befitting that, their movements behind the counter are not as studied as some of the city’s more timeworn sushi chefs. That might be a good or a bad thing depending on the kind of performance you seek. Old masters, maneuvering each digit with the ultimate degree of intention, are a treat to watch. These motions, juxtaposed by a stoic and silent demeanor, can even be hypnotic. They invite a careful, worshipful appreciation of omakase that connects the diner to the craft’s rich history. Really, they work to remove you from time and channel all of your senses toward that crucial moment where fish and rice pass from the chef’s hands into yours and onto the palate. This sense of anticipation—an excruciating buildup to a single bite of pleasure repeated a dozen times or more—imbues the meal with a greater sense of value. You are not spending hundreds of dollars on a series of morsels but a “one man show” of traditional, artisanal production.

Yume and Mako fit this mold, and Chicagoans benefit from having a reference point for this more serious manner of presentation. However, Sangtae and B.K. Park did not train under recognized masters (as Otto Phan did with Masa Takayama). Thus, their approach to the craft does not fit into any particular lineage and does not reflect any of the added charm that comes from being a living disciple of a long, grand tradition. Both Parks also mass produce their nigiri in an assembly-line fashion, severing that essential dimension of the meal in which each piece—over and over—is made just for you. Once you come to recognize these flaws, the seriousness of Yume and Mako starts to seem a bit silly. The chefs have pleasure to give, but their work is really not worth watching closely or worshipfully because it compromises on the craft so clearly while lacking any historical connection to top practitioners.

With this in mind, LEYE has directed its chefs at The Omakase Room to put on a bit more of a show: toasting, jokes, physical comedy, and an upbeat soundtrack ensure the performance does not seem too serious. Sushi Suite 202 and Sushi by Scratch Restaurants go one step further by downplaying the ritualistic aspect of the craft altogether and treating the meal as something more of a party. Jinsei Motto’s style of performance can be placed somewhere in this realm, and the restaurant might just benefit from having the most talented cast.

Of the two chefs, Chen is quieter. Nonetheless, he benefits from being able to treat patrons to a sake toast (sometimes even several during the course of the meal) and having the DRYAGER to discuss. He’s also—as you have already mentioned—on the younger side, making him naturally seem affable and approachable to those who might want to learn more. Perhaps it’s his body language, which signals precision and focus but does not amount to the kind of blinders that work to forbid any disturbance. Otherwise, the energy of the distillery takes hold and allows you to watch the chef prepare the various pieces while talking to the rest of your party and running no risk of interrupting the “show.”

Jones, in contrast, is quite personable and charming. He has an easy smile and palpable enthusiasm for his work that does not preclude a depth of technical knowledge either. Frankly, other than when Phillip Frankland Lee was actually working at Chicago’s Sushi by Scratch Restaurants location, you cannot think of a more charismatic chef who has graced the omakase genre here. Yes, you have made your admiration for Otto Phan clear, but his “act” is just a brash kind of authenticity backed by great talent and appealing because of its raw, somewhat vulnerable nature. Jones, working Bouaphanh and Choi’s counter, is competing more with all the other chefs making nigiri four, five, or six pieces at a time. He is going toe to toe with all the other craftspeople who have—for whatever reason—compromised on the essential quality of the rice and has surpassed them as an entertainer.

Yes, there’s more to it than that: fundamental techniques regarding the slicing and scoring and topping of fish. Nonetheless, as pleasing as it is to watch a stoic sushi master handle a hulking fillet of tuna, you cease to care once it is revealed that they compromise on the rice. The spell is simply broken, and any lack of showmanship from the chef can no longer be painted as a virtue. They are not so devoted to their craft—so dedicated to tradition—that they cannot speak. No, they have sold out any true sense of artisanship in pursuit of efficiency and profit. It galls you to see them carry themselves as if they are showing Chicagoans anything of worth because they are actually using the “sushi master” role as a disguise for a lack of tableside manner. It feels, once you notice it, completely false. It is totally inauthentic and rather patronizing to expect a worshipful response for such a sacrilegious approach to the craft.

Jones transcends this paradigm by breaking down the usual barrier that separates the sushi chef from the customer. He does this not through the same contrived theatrics seen at The Omakase Room or Sushi by Scratch Restaurants but by simply being a kind and witty guy. Engaging the guests, it should be mentioned, is not used to distract from a subpar approach to the craft. Rather, both Chen and Jones put out menus of consistent quality. The former man presents it in a somewhat typical (but still notably friendlier) style while the latter really goes the extra mile to make his patrons feel at home. Call if the gift of gab or just an overflowing degree of positive energy, but Jones is incredibly talented at the oft-ignored social dimension of his job. This was made particularly apparent on one occasion when you found yourself to be the only party seated at the counter. The chef—with just a bit of banter—transformed what could have been a stilted, self-conscious occasion into something effortless and fun. His personality really marks the Jinsei Motto experience as unique, and he really helps to make the restaurant a destination in a way that not many other professionals in Chicago are capable of.

With your choice of beverage set and the chef’s introduction having been made, the omakase is set to begin. Thus, before getting to the food, this seems like a good moment to meditate on the meal’s price.

Jinsei Motto advertises its counter seating as a “19-Course Omakase” priced at $175 with a gratuity of 20% added to the final bill. A deposit of $100 per person, as previously mentioned, is due upon booking, with cancellations fewer than 24 hours before the reservation time possibly provoking a full punitive charge. This is all fairly standard, but you appreciate the use of the term “gratuity” rather than a weasel word like “service fee” that can sometimes make patrons feel pressured to leave an additional tip.

Looking across the city, Bouaphanh and Choi’s omakase clocks in just north of Kyōten Next Door ($159, exclusive of 18% service charge) and Sushi by Scratch Restaurants ($165, exclusive of 20% service fee) and just south of Mako ($185, exclusive of 20% service fee). Meanwhile, Jinsei Motto falls a bit short of places like Omakase Yume ($225, exclusive of discretionary gratuity) and The Omakase Room ($250, exclusive of 20% service fee) while falling far short of Kyōten ($440-$490, inclusive of service).

Likewise, it is worth considering that the omakase’s $175 price point place it in the neighborhood of fine dining tasting menus like Topolobampo ($145-$165), The Coach House by Wazwan ($150-$175), Boka ($165), Goosefoot ($175), Smyth’s entry-level “Classic” menu ($175), Next ($155-$195), Schwa ($165-$195), Brass Heart ($185), Valhalla ($185), Atelier ($190), and Temporis ($195).

Clearly, Jinsei Motto is competing with establishments that already hold Michelin stars or, at least, are trying hard to get them. It has also situated itself firmly in the upper echelon of Chicago omakase experiences. At the same time (and this reminds you a bit of Valhalla), Bouaphanh and Choi’s restaurant still maintains a bit of a pop-up feel due to its larger setting. CH Distillery has its charms—its sense of character and “backroom speakeasy” authenticity—but can such an ambiance, adopted rather than designed from the ground up for the concept, really be called memorable? Can it engage each of your senses and hit the same emotional peaks as the more glamorous, exclusive counters fashioned by the city’s major hospitality players? That depends not only on the chefs’ tableside manner, but whether the quality of the sushi punches above its weight to such a degree that it makes their competitors’ comparatively luxurious dining rooms seem like more of a distraction. This may be worth keeping in mind as you engage in your analysis.

Jinsei Motto’s omakase starts, as many tasting menus do, with that most pristine presentation of shellfish: the solitary “Oyster.” Rather than serving the bivalve on the half shell, the chefs extricate the meat and some of its juices to be served in a small sake cup that comes nestled over rocks on an earthenware plate. A touch of vinegar, some minced shallots, and a wee bit of scallion complete the presentation.

The oyster itself is a Pink Moon from Prince Edward Island, one of the northernmost varieties harvested on the continent. When it reaches the palate, its meat displays a pleasantly creamy texture with so sense of chew. The bivalve melts and imparts a mildly salty sensation that is enlivened by the vinegar and sharp allium elements before closing with a faintly minerally finish. This is nice—if not life-changing—bite that strikes you as a bit smoother and fresher than the oyster served in Sushi by Scratch Restaurants’s lounge. Likewise, the sake glass “shot” format offers diners the opportunity to toast each other at the start of the menu: a communal ritual they may come to find is repeated, with actual alcohol, throughout the meal’s duration.

The first proper piece of nigiri arrives right after: “Madai,” or sea bream, sourced from Japan. This fish, which displays a coppery-red tone to its flesh, is briefly scalded in hot water before being iced and sliced to be formed onto the rice. A bit of Buddha’s hand (also known as the fingered citron) zest provides the finishing touch.

Grasping the bite in your hand, the rice seems solid enough (that is, no risk of breaking apart) without being totally petrified. The grains crumble cleanly without drawing much attention to themselves and yield to the madai’s pleasantly firm but ultimately tender texture. As you chew, the sea bream’s mild sweetness and umami—free from any overtly fishy notes—comes to the fore. The Buddha’s hand, in turn, distinguishes the nigiri with a tangy, slightly floral finish. This all makes for a good start, one that impresses you with its restraint but does not lack flavor.

Alternatively, Chen and Jones have served “Hirame” as the first piece of nigiri on subsequent occasions. This style of flounder is sourced from Korea, and the chefs utilize the engawa (or striped “veranda-shaped” muscle used to move the fins) from the fish. It is topped, rather like the “Madai,” with a dose of citrus courtesy of some lemon juice. However, the engawa of the hirame displays a faintly crunchy, then fatty mouthfeel that is less straightforward than the sea bream. Nonetheless, it displays a similar clean, sweet flavor as before backed by a sour finish. This is also good—if just a little less refined than the “Madai.”

Moving on, Jinsei Motto has served pieces like “Isaki” (threeline grunt) and “Aka Isaki” (red grunt), both sourced from Japan, in the early stages of the meal. These fish are known for their pale pink flesh (distinguished here with small strips of skin) and for being among the fattiest of the “white-fleshed” varieties that appear throughout the spring and summer. The resulting slices, appropriately, cascade over their clumps of rice and display a glossy, tantalizing sheen with small reservoirs of soy sauce tucked into their grooves.

With the “Isaki” and “Aka Isaki,” the quality of the chefs’ knifework comes more to the fore. It is not the most intricate in town (like, say, the countless latticed lacerations used to provide length and definition to some Kyōten’s fish); however, it is serviceable. When the threeline and red grunt pieces reach your palate, their three or four divided segments of plump, shining flesh can be distinguished. This helps you break the (still somewhat firm) fish apart and mix it with the rice without being overwhelmed by the topper’s size. As this happens, the grunts’ latent fattiness begins to permeate the grains and impart a delectably rich, sweet flavor that remains totally pristine. Again, this is nice but not quite amazing—missing, perhaps, a bit more textural intricacy and depth.

Nonetheless, with the arrival of the “Kinmedai,” things start to get more serious. The golden eye snapper (also known as splendid alfonsino) is revealed to have been aged between three and five days (depending on the exact timing of your visit). This marks the first real invocation of the DRYAGER that you can recall, and it carries with it the expectation that you will—after some more delicate opening bites—encounter a superlative degree of flavor. It also, across your three meals, marks one of Jinsei Motto’s most varied uses of toppings: the fish being garnished with yuzu koshō, shiso salt, and what look like very thin strands of ginger on different occasions.

The kinmedai is recognizable thanks to the long, interrupted strip of skin (often, as in this case, lightly torched) that runs along its side. Its flesh, typically on the opaque, pinkish side, also takes on a slightly deeper hue thanks to the dry-aging process. On the palate, the golden eye snapper’s buttery texture benefits from being slightly moderated. The time in the DRYAGER serves to tighten the flesh just a bit, allowing it to show the slightest resistance against your teeth before unleashing its inner fat. On one occasion, the mouthfeel—in this fashion—was a bit too chewy, but it has generally made for a beautiful contrast with the fish’s tenderness. The kinmedai’s flavor, too, sees itself concentrated due to the dry-aging. It exhibits a mild, clean character that, nonetheless, resonates with deep layers of umami that stand up to the range of salty, tangy garnishes. This all amounts to a wonderful intensity that makes for one of the omakase’s best early pieces.

That being said, the best of all Jinsei Motto’s opening nigiri has, in your experience, been the “Ishidai.” Also known as the striped beakfish, this small, shallow water specimen is sourced exclusively from Japan, where it utilizes its namesake beak (and strong jaw) to feed on shellfish like sea urchin. This piece is one of the rarer ones you will find stateside, and the chefs—rather than treating it with kid gloves—swing for the fences with a garnish made of fermented black bean.

In practice, the beans have been processed into something more like a fine powder, ensuring that the ishidai remains the star. On the palate, the fish displays one of the chewiest mouthfeels you have yet encountered that, with further mastication, yields to a resounding softness. This serves to enhance the piece’s presence on your tongue and provide a greater sense of satiation. In terms of flavor, the striped beakfish—like so many of these early bites—is predominantly mild and sweet. However, corresponding to the bite’s more lasting texture, the fermented black bean element offers refined salty and funky notes that last through the finish without obscuring the main ingredient. This amounts to a dimension of savory power that, combined with that chewy-soft interplay, is incredibly appealing. Overall, a hedonistic treat.

The “Ishigaki Dai,” or spotted knifejaw, has replaced the “Ishidai” on subsequent occasions and stands as something of a kindred piece (with the striped beakfish also being termed a “barred knifejaw” at times). The fish, like its predecessor, also feeds on shellfish but boasts a blackish-brownish “stone wall” (the literal meaning of ishigaki) pattern on its skin instead of stripes. The chefs wrap the spotted knifejaw in seaweed and age it for just two hours before slicing it generously, forming it to the rice, and topping the bite with shiso salt.

On the palate, the ishigaki dai offers much of the same chewiness as the ishidai but on a larger scale. The thicker slice corresponds to greater initial resistance against your teeth with a broader—but still creamy—interior as it breaks apart. This overall sensation is not tough by any means, yet it still seems a bit clunky when compared to the more concentrated textural experience of the striped beakfish. Nonetheless, the spotted knifejaw provides some of the same clean sweetness as its predecessor with, once you have chewed through it, a bit more richness. This works well enough with the faintly floral shiso salt, but you ultimately prefer the more savory, slightly earthy notes provided by the fermented black beans. Overall, the ”Ishigaki Dai” is certainly less successful than the “Ishidai” but remains interesting as a point of comparison.

At this point in the meal, you may begin to cleanse your palate via the pickled ginger provided on a small dish. These are not the large chunks seen at The Omakase Room or the mixed bag (cucumbers, mushrooms, and all) served at Sushi by Scratch Restaurants, but, rather, a more conventional offering made of wide, thinly-sliced segments of the root. Texturally, the ginger shows a moderate crunch that is married with a subdued intensity. This is a good enough example of the form but not all that impressive when compared to a top example like Kyōten, where the slices are thinner, crunchier, and still more intense.