After spending a bit of time exploring two of Chicago’s more longstanding fine dining concepts, you now shift your focus to a restaurant that has successfully reached middle age. That, at least, is how you might conceive of a place that will soon be approaching its seventh birthday, under the command of its third executive chef, after weathering a pandemic and never deviating from the tasting menu form.

Yes, while Boka and North Pond made their names (at least in part) slinging à la carte fare for their communities, Temporis has always been a gastronomic outpost. The restaurant, then and now, sits quietly off of one of West Town’s main conduits in what is technically Noble Square. Its neighboring Pappanino’s, with those extra-large stadium pies, is now gone, but cult confectioner SUGOi Sweets has made a home for itself just one door down. Otherwise, the block is defined by a high school, a dentist, some salons, and a vintage musical instrument store.

No doubt, it’s a busy street (medians and all)—albeit as more of a thoroughfare. From a dining perspective, Temporis stands totally removed from the sprawl of taquerías, bars, and Thai spots that line Chicago Avenue. Just the same, you won’t see customers lined up around the block as they do at Kasama, located just a few blocks away and similarly isolated along its stretch of Augusta Boulevard.

Of course, not many tasting menus can count on that kind of daytime operation to act as a solid foundation while perpetually provoking interest from passersby. They, like Temporis, must hide in plain sight: a Bibendum-recommended destination that nobody would notice unless they had checked the Guide (followed by the recent Yelp reviews) and decided to take the plunge. The restaurant, flying that impenetrable “progressive American cuisine” banner, does not benefit from being pigeonholed as the Michelin-starred exemplar of this or that ethnic cuisine. Nor does itidentify itself explicitly—like Esmé or Ever or Schwa—with that much-derided (but thematically illustrative) “molecular gastronomy” moniker.

Temporis does not boast the kind of palatial (or natural) setting one might wish to show off on a special occasion. And, while the plates are pretty and both chef and restaurant are active on social media, the concept cannot claim much viral traction. You do not mean to imply that is a bad thing, for no kitchen—at this level—should cook in accordance with what conspicuous consumptive “foodies” and terminal scrollers wish to see. But, with only 20 seats to speak of and bookings spread over five nights a week, any positive impressions (should a guest be inclined to share them) are necessarily diluted by the great mass of online food content.

“Middle age,” to you, means that the concept has been the “hot new opening,” pleased the local critics, earned Bibendum’s endorsement, and done everything to get over the initial hump of being judged a success. In changing chefs, the restaurant even earned a second positive review from the Tribune while retaining that Michelin star all the while. However, as new openings continue to churn and the dining scene is defined by emerging trends and outside forces, Temporis finds itself in a fight for relevancy.

Where exactly does the place—that’s neither old nor new, that falls within an opaque genre, that may be cutting edge but has nobody to champion it for being so—fit? Once the local “critics” have had their say, they cannot very well afford to keep dining there even if the quality of food merits it. Duty calls them to talk about what’s new and colorful even (or especially) when it does not seem destined to last. So, somewhere like Temporis may occasionally pop up on an end-of-year “best of” list or be branded as some self-important contributor’s hidden fine dining gem. But it tends to escape attention, or even knowledge of its very existence, beyond those innocently scanning the Michelin Guide in search of a good time.

The restaurant sees the exact nature of its growth, over a period of months and years and countless dishes, obscured. Never mind that it has already established itself as one of the city’s finest establishments. Lacking the right audience, who communicates their experiences in the most far-reaching way, Temporis gets lumped in with every other tasting menu in town. It becomes wholly defined by its star rating and entered into a series of comparisons—driven by value, aesthetics, branding, and biases of all stripes—that deny all that makes the concept unique. For the most intricate, flavorful cuisine often has no means of announcing itself as such while the loudest voices in the room, more often than not, rely on panache to make up for creative bankruptcy.

In truth, you may be getting ahead of yourself a bit. Experienced diners come to learn that, once a restaurant earns its Michelin star(s), Bibendum is generally inclined to let them hold onto the rating. Enterprising establishments may endeavor to nab that second or third coveted symbol, renovating and investing in lowering their staff-to-guest ratio to do so, but concepts that have carved out a niche need only really maintain it. Thus, the tasting menu spot with wine pairings and suited, deferential service will continue to look and feel the part so long as standards do not drop precipitously. Cuisine matters, but it need not grow or improve beyond what first earned the star(s). The food can even regress a bit—with any claim it has done so shrouded by the essential subjectivity of taste—so long as the kitchen is not putting out demonstrably flawed plates.

In changing chefs, Temporis has already granted Bibendum a golden opportunity to sanctify or condemn any major changes to the style of the tasting menu. The restaurant has seemingly passed the test, but how much of this still might be inertia? Does substituting one chef’s vision of a $150-$200 meal, with all the same totemic luxury bells and whistles, for another’s amount to that much of a change when the overall “experience” has been preserved? First-time customers who are new to fine dining will find themselves charmed by the novelty and trappings of luxury all the same. Only patrons who are equipped to compare the restaurant’s value proposition to its competitors, who may even have eaten at Temporis in its previous era, can get at the truth: is this a “Michelin-starred restaurant” in its prime or one that merely continues to wear that skin?

With every major closure (particularly ones like Blackbird, Brass Heart, and CLAUDIA), Chicago reveals just how much it struggles to sustain the “contemporary American” genre. This seems to hold true whether a restaurant is a member of the old guard, primely positioned in a fashionable neighborhood, or a young runt, bringing some higher expression of gastronomy to a more isolated community. Temporis, in its middle age, occupies a key liminal place between these poles that is ripe for analysis. Such a review will not only cast light on where the restaurant, nearly seven years on, stands. It may help to reveal how a “progressive American” concept successfully expresses an identity that is not obvious or even salient from afar. At the very least, it will aid in a greater understanding of how chefs can sustain themselves within this permissive but amorphous genre without needing to utilize smoke and mirrors or moonlight as a social media provocateur.

Nonetheless, before putting Temporis through it paces and grappling with these more overarching questions, it may be instructive to take a look at how the restaurant has gotten where it is today.

The story starts back in 2015, when chef-partner Sam Plotnick hosted a series of “pop-up dinners in his apartment” with “another chef friend.” Plotnick had cultivated a love of cooking while studying economics at SUNY (via “a single electric crock-pot in his college dorm room” and a “hydroponic herb garden growing in his closet”) and, following graduation, began a summer internship at Les Nomades. There, he would help open Goosefoot with Chris Nugent before rising to the rank of chef de tournant in Roland Liccioni’s kitchen. In that role, Plotnick worked under sous chef Evan Fullerton (who cut his teeth at Roland Passot’s La Folie in San Francisco) while at Les Nomades before the latter moved on to become the executive chef of 1913 Restaurant + Bar in Roselle.

The pair stayed in touch as Plotnick began hosting those pop-ups and wondering wonder how he could recreate the “personal feel of going into someone’s own dining room” he so enjoyed in a restaurant setting. The chef-partner mulled over “the simplest business model and operation” he could use to capture that feeling and cook the same sort of food, settling on the idea of opening a 20-seat—rather than an “80-seat”—concept. Soon after, Plotnick found the former Moku Sushi Bar space (at 933 N Ashland) and called up his former boss Fullerton to come aboard as co-chef.

The two men had been “writing down ideas” for their “own food” over the years, and Plotnick hoped to foster an open creative dialogue at the forthcoming restaurant he likened to “the feel of a writer’s room,” where “you can say whatever you want and you don’t leave the room until you’ve created something exciting.” The chef-partner, despite initially forming the vision for the project, characterized himself as “not nearly experienced enough to want to be yelling at everyone else” in the kitchen. Fullerton, in turn, had “a lot of great experience,” and his ideas would be embraced so that they “could make the best food that…[they] could make.”

Stylistically, the cuisine was “not going to be French” like Les Nomades but “contemporary American,” using “local ingredients” and “any techniques” the chefs wanted. Plotnick would characterize his and Fullerton’s approach as liking “to focus on balancing flavors and textures” while “exploring” their “favorite ingredients in-season.” He would also classify that “contemporary American” label as being “about breaking from the traditional pairings of ingredients and being extremely local.” The two chefs, likewise, “have a bunch of heritages” and wanted “to let go of a single heritage and blend them all with an open mind.”

Elsewhere, Plotnick would describe the restaurant’s “model” as a “hyperlocal menu” focused to “the beginning, middle and end of a season” in order to create “a full ten-course tasting.” The chefs would not “change all the courses over at the beginning of a season” (because it would represent “a huge undertaking for the kitchen”) but, rather, “as things slowly come into season, and things slowly go out,” they would replace individual dishes. To that point, the restaurant would be “buying from Local Foods and from the farmers markets” without “an overly strong thing” where they’d “have to support local farmers over, say, California farmers.”

Instead, Plotnick would contend that “there’s nothing more local than growing all of your herbs and much of your greens in your own restaurant” and reveal the concept would make use of “a hydroponic garden in the basement.” Through this, the chefs could “somewhat challenge the idea of what a seasonal restaurant is” by cultivating ingredients “twenty feet from the diner” and combining them “with things in season that would never go together.” Plotnick gave the example of pairing “a perfect summer strawberry with a perfect winter parsnip” and decried those who might resist this bending of nature’s rhythms as wanting “to stick with the traditions and the social norms.”

This sensibility—of hydroponic gardening and the manipulation of conventional “seasonality”—would find its expression in the restaurant’s chosen name: Temporis, which means “time” or, in the chefs’ own words, “the passage of time.” It would also come to define the concept’s design too. Plotnick would admit “there’s not much nature around” the restaurant. However, the dining room’s lighting would be “all LED, completely color controlled and temperature controlled” individually “for each table.” This would allow for “more subtle changes, more gradual changes” to the mood of the space during the course of the meal (that might end, for example, “with a warm amber color”). The tables would also feature wooden panels at their center that could be lifted out “to reveal a small well,” which would allow the chefs to showcase “the herbs that are used in a dish” growing right before guests’ eyes. Alternatively, the indentation might be used to house “a little zen garden with hot rocks” used to sear “pieces of meat or raw fish.”

Plotnick and Fullerton, speaking during the summer of 2016, aimed to open Temporis that same fall. In the meantime, the chefs hosted a series of pop-up previews at Local Foods throughout August. These meals, along with all the media coverage, offered them the chance to give some sense of what might be on the opening menu.

Dishes included “mini cones made from fennel tuile…stuff[ed] with king crab, parsnip-smoked trout roe and fennel;” “fermented sunchoke puree with salsify, dandelion greens, frisée and a chamomile gelée;” “tandoori-spiced rabbit loin, a tiny roasted rack of rabbit, and braised rabbit leg with carrot purée, rattlesnake beans, and mustard greens;” and “foie gras ice cream with pork-poached cherries.”

One dish in particular, a hamachi tartare, would be particularly instructive as to how the chefs think. In Fullerton’s words, it would combine the “traditionally French” tartare form with “yuzu juice” and “a little bit of the molecular gastronomy” without making the latter “the focus of the dish.” The preparation, which was also said to include “dehydrated hazelnut oil and an ‘almost puréed’ ginger sugar cookie,” ultimately combined “Asian ingredients” with “French technique and a little bit of New Age science.”

Plotnick, discussing the state of fine dining more broadly, would note that “it seems like every dish on a tasting menu has to have one thing you’ve never heard of.” In contrast, Temporis would look to offer food that is “a touch more precise, and familiar, and comforting” with the goal of ensuring each preparation has an element that is “going to make someone crave it” and “want to come back.” Whether that demands the chefs “think out of the box” or lean on “something classic,” they would do whatever they can to make each dish “delicious.”

Otherwise, Plotnick expected that he and Fullerton “can run the kitchen by ourselves with the help of just a part-time dishwasher.” Rent would not be “incredibly high in Noble Square” and they wouldn’t “have much food waste.” The chef-partner, nonetheless, hoped to “make some wine sales” via optional wine pairings and an à la carte list. To do so, he brought on Donald Coen (who worked on the wine team at Alinea before becoming a captain “within the wine program” at Les Nomades) as beverage director. Coen would retain his position at the latter restaurant while crafting a list filled with both “classics” and “esoteric varietals that don’t receive as much attention as they should.” He highlighted, in particular, “wines from the Savoie and Jura regions” as being among the “rare” selections that would set Temporis apart.

Despite having a team and a location in place, Temporis’s fall opening would—as so often happens—be delayed. The restaurant did not welcome diners in 2016 (a year that saw juggernauts like Elske, Oriole, and Smyth enter the fray) but began serving guests the first week of 2017.

The opening menu ($110), accessible thanks to internet archiving, featured dishes like “King Crab” (with parsnip, salmon roe, and dill pollen), “Wild Mushroom Consommé” (with pickled cipollini and scallion), “Socca Chip” (with rabbit rillette and pear), “Venison Shank” (with coffee stout, granola, and pomegranate), and “Aged Cheddar” (with an ibérico gougère and quince) alongside aforementioned ideas like the “Hamachi,” “Sunflower in Five Forms,” and “Rabbit” (three ways). Wine pairings (five pours spread across the 11 courses for $95) included producers like René Geoffroy, Château de Puligny-Montrachet, Jean-Louis Chave, and Domaine des Baumard.

Time Out would be the first to offer a review of Temporis in March of 2017, describing it as “a textbook fine dining choice for romantic dinners” with “some culinary curveballs in store.” The restaurant, earning three out of five stars, would be criticized for “inconsistent” portion sizing “from plate to plate” but earn praise for the “hidden cubbyhole” of microgreens used to garnish a cast iron skillet filled with “meaty hunks of [rabbit] loin, a tender leg and a flavorful little rack of ribs.” Ultimately, the concept was judged “a surprising and intriguing option in an intimate setting—perfect for a fancy and fascinating night out.”

The Chicago Reader would chime in at the end of March, describing the restaurant as “nothing if not restrained” with a “museumlike quality” to both the food and ambiance. The “King Crab” and “Sunflower in Five Forms” drew praise while the “Hamachi’s” ginger sugar cookie element seemed like an “odd addition” that “didn’t leave” the critic “wanting more.” The “umami bomb” serving of “Wild Mushroom Consommé” was also noteworthy, and both the “Rabbit” (despite “a somewhat dry boneless leg”) and “Venison Shank” were termed “well prepared.” The “last three [dessert] courses were, as a whole, the best of the evening.” However, despite finding that “almost all the food had been memorably excellent” and “the service was impeccable,” the author left “still hungry.”

All in all, this does not seem like a bad start for a restaurant—just two to three months old—from a couple of young chefs. Yelp reviews from the same period are generally positive too, with the lowest ratings (three out of five stars) again citing small portion sizes as their main issue.

Despite (or is it because of?) that, Temporis would undergo a major change in May of 2017. Fullerton departed from his position as co-chef and returned to 1913 Restaurant + Bar as executive chef. Don Young would be his replacement, admitting that “it kind of came push to shove, the last chef wasn’t working out, and it made sense for me to jump on board.” Young himself was a graduate of Kendall College who interned at Simon Scott’s Michelin-starred Bistrot Saveurs in Southern France before rising to the role of chef de cuisine at Les Nomades. He was also, as luck would have it, that “other chef friend” Plotnick had been doing his pop-ups with in 2015.

Young, who was “couch-surfing” at Plotnick’s apartment during that time, thus formed a key part of Temporis’s genesis. Joining the restaurant only a handful of months into its opening (though, before then, he would “stop by…when possible to help in any way he could”), the former would eventually become the concept’s lone executive chef as the latter transitioned to a front-of-house role. However, more immediately, Young and Plotnick would bring a fresh perspective to the cuisine. By all accounts, the partnership was successful.

In June of 2017, the Chicago Tribune would award Temporis three stars (“excellent”) out of four and praise the “considerable rewards” that lie in wait for those who visit the “tiny fine-dining room in Noble Square.” The price of the menu, by then, had risen from $110 to $125. But the article praised dishes like a “sweet sashimi scallop” with “nettle puree, sea beans and a coriander tuile” and a “robata-grilled octopus tentacle” with “miso-glazed eggplant, marinated shiitakes and strawberry,” That being said, the “heavier dishes” are said to be the “most impressive.” This included both the “Rabbit” from before and a new “painterly presentation” of lamb loin with “red-wine lamb sauce and herbes de provence pudding.” Desserts (including a new “deconstructed peach pie”) were termed “nifty”—and service “smooth and unobtrusive”—in a glowing review that hoped “more people will come to appreciate this restaurant.”

Despite the praise, Temporis would not catch Bibendum’s eye when Michelin released its 2018 Guide in the fall(a year that saw Smyth earn its second star and Elske and Entente clinch their first). Nevertheless, Plotnick and Young would be nominated for “Rising Chef of the Year” at the 2018 Jean Banchet Awards (alongside Diana Dávila and Brian Fisher), eventually losing to Nick Dostal.

Still, all things considered, the restaurant had handled its launch and a difficult chef transition with aplomb (even if its 20 seats were only “about a third full” when the Tribune made its two visits). The end of 2017 and dawn of a new year would offer Plotnick and Young the chance to articulate an even fuller vision as Temporis passed its first birthday.

2018 would see the concept introduce a $165 reserve pairing but maintain its $125 menu price. Representative dishes from this year include:

- “Escargot” (with brioche, kombu, and dill)

- “Donut” (with Mangalica ham, kombu, and dill)

- “Salmon” (with uni, cordyceps, and turnip)

- “Langoustine” (with anchovy, avocado, and radish)

- “Turbot” (with uni, eggplant, and vermouth)

- “Capellini” (with beech mushrooms and gooseberries)

- “White Asparagus” (with morels, Mangalica ham, and sheep’s milk)

- “Blue Corn Grits” (with Mangalica ham, hoja santa, and coca nibs)

- “Scallop” (with soy, XO sauce, and pineapple)

- “Portobello” (with rye, sunchoke, and fines herbes)

- “Squab” (with chanterelle, Swiss chard, and corn)

- “Rabbit” (with corn, potato, and sauce chasseur)

- “Iberico” (with guajillo, peach, and various greens)

- “Comté” (with tomato, balsamic, and Thai basil)

- “Wagyu” (with celery root, apple, and red wine)

- “Elysian Fields Lamb” (with ramp, squash, and curry)

- “Sofia Goat Cheese” (with strawberry, beet, balsamic)

- “Blueberry” (with maple, pancake, and tangerine lace)

- “Meyer Lemon” (with poppy, gin, and buckwheat)

- “Foie” (in the style of “PB&J”)

- “Foie Gras” (with cherry, black sesame, and madeleine)

- “Peach” (with Marcona almond, granola, and flowers)

- “Chocolate” (with passion fruit, coconut, and lemon basil)

Served with wines from producers like Paolo Bea, Bond, Calon-Ségur, Bruno Clair, Bruno Colin, Ulysse Collin, La Conseillante, Dagueneau, Dönnhoff, Eisele Vineyard, Bruno Giacosa, Kongsgaard, Krug, Labet (Jura), Littorai, R. López de Heredia, Benjamin Leroux, Lynch-Bages, Massolino, Mongeard-Mugneret, Bernard Moreau, Pol Roger, Joh. Jos. Prüm, Giuseppe Quintarelli, Jean-Michel Stéphan, and Taittinger.

For this work, Young—who cemented his position as lone executive chef during the course of the year—would, in the fall of 2018, catch Bibendum’s attention. Awarding Temporis a star in the tire company’s 2019 Guide, Michelin’s chief inspector would praise the experience as “consistently impressive” with a “really distinct personality” and “a mastery of technique.” He would even classify it “as a restaurant that was setting a global standard.”

In truth, Plotnick and Young had been “anticipating” the award (because “Michelin sent the restaurant an email to confirm the correct phone number”) even though the latter admitted Temporis was “barely making it by” before then. The restaurant would close “most Tuesdays” due to a lack of reservations and, on other weekdays, “would be lucky to serve eight to 12 dinners” (though, admittedly, it benefitted from “a supportive investor”).

Earning the honor, nonetheless, led to “a huge influx in business” in the months that immediately followed (from “a total of zero reservations booked for the next day” to “362 reservations in 12 hours”), allowing the team to begin hiring “more staff and more experienced staff in the kitchen” while “overhauling the menu” and “shooting” for a second star.

As an added bonus, Temporis would be nominated that same fall for “Best Service” at the 2019 Jean Banchet Awards and, on this occasion, beat out Daisies, NoMI, and Shanghai Terrace to take home the prize just after its second birthday in January.

Entering the new year, Plotnick and Young could count on some exciting developments. Don Coen, who had been “overseeing the beverage program while still full-time at Les Nomades,” came aboard as the full-time “beverage director and sommelier.” In addition to “building out a larger kitchen,” the team would also “double the size of the hydroponic garden, allowing for more experimentation with microgreens and other produce they’re growing.” This would allow each diner to be given “a tiny ‘living salad’ of microgreens, served straight from soil to table” with the dream of eventually cultivating “individual strawberry plants, complete with fresh strawberries, in the middle of winter.”

Young would also, at the time, note his “deep interest in fermentation, preservation, [and] pushing the traditions of classical French cuisine.” This would be articulated through a new dish he teased to the press: a “seared scallop mille-feuille” layered with “cranberry, pickled pineapple, black walnuts and red kuri squash,” topped with “candied pumpkin seeds, crispy Brussels sprouts and crispy chicken skin” then finished with “a tableside pour of Young’s take on XO sauce” (“newly fermented soy sauce” enriched with “duck and scallops”). The restaurant would also, looking ahead, promise “more interactive elements incorporated into the experience” through the “custom-designed tables and serving vessels.”

In truth, many of the dishes (like the “Donut,” “Capellini,” “Portobello,” “Rabbit,” “Comté,” and “Meyer Lemon”) served at the end of 2018 would remain on Temporis’s menu through May of 2019. However, there were indeed a handful of new preparations like:

- “Salmon” (with uni, eggplant, and vermouth)

- “Scallop” (with carrot, raisin, and cumin)

- “A5 Miyazaki Wagyu” (with white asparagus, red wine, and nasturtium)

- “Foie Gras” (with rhubarb, maple, and lemon balm)

- “Birthday Cake” (“tropical,” with “blown out candle”)

Of course, it is worth mentioning that just because certain dish titles (and their constituent ingredients) did not change during this period does not mean they were not refined. The presentation and garnishing of these recipes, especially as it relates to the hydroponic garden, could easily have changed. Likewise, a growing kitchen may have allowed for greater intricacy in how certain central components (like the rabbit) were expressed.

That being said, a much bigger change was afoot. Citing “managerial and creative differences,” Young would leave Temporis in June of 2019. No other details on the split with Plotnick were offered, with the executive chef simply stating he “put a lot of heart into the restaurant” and wanted it “to prosper.” In response to the news that Troy Jorge would take over the kitchen, Young would also say “Temporis is in good hands now.” He went on to become the executive chef of WoodWind and, later, Venteux (where he prepared the best French toast you have ever tasted). Currently, Young conducts seven- and 15-course pop-up experiences under his brand Duck Sel.

Back at Temporis, Troy Jorge, stepping into the executive chef position, would represent a clear break from the Les Nomades lineage that had thus far characterized the concept. He, a “self-proclaimed former punk kid” was born and raised in New Bedford, Massachusetts and originally “wanted to be a fashion designer” but “got kicked out of…sewing class freshman year of high school.” Nevertheless, a home economics class during junior year helped him discover a passion for cooking, which led him to enroll in culinary school.

From there, Jorge went to Boston, working at The Ritz-Carlton and Ken Oringer’s Clio (now UNI) before joining Jamie Mammano’s Columbus Hospitality Group. There, he rose to become sous chef of Ostra, a “contemporary Mediterranean seafood restaurant,” and chef de cuisine of Mooo…., a “modern steakhouse.”

After five years in Boston, Jorge “felt he had gained enough knowledge and experience to understand where he truly wanted to be.” That meant chasing the “dream” of working with Curtis Duffy at Grace, where he held the position of chef de partie from May of 2016 until the restaurant’s closure. Jorge would describe his time there as “incredibly intense,” “the most amazing and efficient kitchen…[he] had ever worked in,” “the cleanest kitchen” he had “ever seen,” and “everything…[he] had hoped it would be and more.”

After Grace, he worked at two-Michelin-star Acadia for a short period as sous chef then, later, consulted “for a restaurant and art gallery in the West Loop” before taking the Temporis job. Jorge described his new home as “a special place” with “an incredible level of talent and passion” he was “excited to be part of.” Wyl Lima, a colleague from Grace and Acadia, would come aboard as sous chef while, stylistically, he would describe his approach to the tasting menu as “driven by colors, contrasts and layers of flavor.” Elsewhere, more specifically, Jorge would note “abstract art” as “a big source of inspiration” in making “ingredient driven,” “playful” cuisine that seeks to be “as delicious” and “as beautiful” as possible. Still, the executive chef would prize a “natural look” that does not seem “intentionally placed” or “forced” but, rather, seems more like ingredients such as “herbs or flowers…fell from the sky.”

Taking the reins in July, Jorge would immediately put his stamp on Temporis’s tasting menu by debuting an entirely new range of dishes:

- “Squash Blossom” (mushroom, foie gras, Sauternes)

- “Fluke” (strawberry, lime, tangerine lace)

- “Crab” (avocado, grapefruit, pumpernickel)

- “Artichoke” (barigoule, parsley, lemon)

- “Tomato” (cucumber, basil, cantaloupe)

- “Lobster” (vanilla pasta, truffle, tarragon)

- “Sunchoke” (parmesan, gooseberry, sunflower)

- “A5 Miyazaki Wagyu” (broccoli, orange, cashew)

- “Mojito” (Key lime, pineapple, boba)

- “Watermelon” (feta, mint, BLiS Elixer)

- “Pistachio” (white chocolate, cherry, lemon balm)

Only one component (“tangerine lace”) from one of the preparations (“Fluke”) seems to offer a clear connection to the kind of work Young was doing. However, certain elements—like that trusty A5 Miyazaki wagyu and a range of herbs from the hydroponic garden—speak to a more overarching “contemporary American” Temporis identity that has remained consistent.

By the end of September, Jorge had begun to introduce other new dishes with the help of Jacquelyn Paternico, a pastry chef (the restaurant’s first) who joined from Michelin-starred Band of Bohemia:

- “Dumpling” (wagyu, scallion, ginger)

- “Kampachi” (fennel, macadamia, blood orange)

- “Corn” (summer truffle, espelette, coriander)

- “Pork Belly” (tamarind, quince, red cabbage)

- “Tosaka” (cranberry, coconut, burnet)

- “Lemongrass” (masago arare, yuzu, shiso)

- “Chocolate” (apple, miso, caramel)

These preparations do not only reflect a greater emphasis on Asian and Southeast Asian ingredients and forms. More importantly, they demonstrate a degree of dynamism that was missing from the restaurant during the earlier half of 2019. (Remember, only five additions were made from the end of 2018 through May while Jorge and Paternico were able to make seven in the span of just a couple months.)

When Michelin announced its 2020 awards at the end of September, Temporis—despite the change in chef—retained its star. Bibendum would term the restaurant “the epitome of serenity, sophistication and subtlety” with a kitchen of “supreme talent and collaboration” displaying “passion, vision, and a…highly intellectualized approach to cooking.” The Guide would also highlight dishes like “escargot with a fermented sour cherry tomato,” “salmon in an uni broth,” “capellini with lobster morsels,” “a paper-thin biscuit with cured Mangalitsa pork,” “decadent foie gras ice cream,” and a “chocolate tart” solidified around a “passion fruit-filled globe.”

These all appear to be dishes that Young added to the menu, and it is worth questioning if Michelin actually bothered to visit Temporis after Jorge (and Paternico) took over before bestowing its star. Just the same, it may be that the honor intended to celebrate the work that was being done at the restaurant for the majority of 2019 (up until that point) while placing trust in the continuity that the same ownership, despite the change in chef, would provide. Whatever the reasoning, Bibendum would eventually update its listing in order to praise preparations like “dark butter-brushed corn, dotted with an espelette pepper-corn purée and finished tableside with summer truffle” and “vanilla pasta with lobster, tarragon, black truffle sauce, and Satsuma powder” that more clearly reflect Jorge’s actual work.

Nonetheless, Jorge and Paternico would indeed merit a closer investigation of their creative efforts when the Tribune rereviewed both Temporis and George Trois in October of 2019. Therein, the critic noted that the restaurant’s new executive chef was “not the fermentation devotee that Young was,” serving dishes that “have more restraint in their use of sour and acidic flavors.” However, Jorge was said to be “doing outstanding work” with highlights including the “extraordinarily balance[d]” “Tomato” and “Crab,” the “umami-focused” “Corn,” the “spectacular” “Lobster,” and the “playful” “A5 Miyazaki Wagyu” styled after beef and broccoli. Paternico’s work, in turn, was said to “match” her counterpart’s “in complexity and artistry.” Temporis would ultimately be rated three stars (“excellent”) as it had been in June of 2017—something of an affirmation that standards had not fallen despite the chef shuffle—but was said to be “awfully close” to that fourth star (“outstanding”).

Jorge and Paternico would craft an array of new dishes (many designed for a special black and white truffle dinner at the end of December) to see out the rest of the year:

- “Pot de Crème” (cherry, tarragon, black truffle)

- “Okinawa Sweet Potato” (bourbon, lime, anise hyssop)

- “Bay Scallop” (Meyer lemon, black sesame, passion fruit)

- “Anson Mills White Grits” (duck egg yolk jam, red wine purée, chicken skin, white truffle)

- “Yukon Gold Tortelloni” (lemon marmalade, parmesan velouté, parsley jam, black truffle)

- “Pheasant” (Humboldt Fog, soubise, watercress)

- “Short Rib Rossini” (celeriac dauphinois, Sauce Périgueux, white truffle)

- “Crépe Cake” (chocolate, sudachi, hazelnut, black truffle)

And Jorge’s “A5 Miyazaki Wagyu,” the aforementioned “whimsical, upscale take on a Chinese-menu staple,” would feature on the Tribune’s list of “The 24 Best Things We Ate and Drank in Chicago Restaurants in 2019.”

With all of this momentum, 2020 promised to be a banner year for Temporis under the command of its new chefs. The restaurant celebrated its third birthday but, not long after, had to contend with the COVID-19 pandemic. Michelin would feature the team’s efforts as part of a May 2020 article on three Chicago concepts, revealing that Temporis was “operating with nine people, including Jorge, which is a close approximation to the original staff size.” The chef “had to come up with a totally different menu that was still the highest quality and something that people are going to want to eat every night,” so the restaurant served items like Faroe Island salmon (with truffled lobster mac and cheese), braised short ribs (with cheddar grits), an A5 wagyu burger, an A5 wagyu footlong hot dog, waffle fries (with black truffle aioli), and brownies over two periods of closure.

Plotnick was able to keep his team together, and Jorge and Paternico could yet again flex their creative muscles as Temporis once more offered its tasting menu (now priced at $155) during the summer and through the early stages of fall:

- “Parsnip” (fennel, pink lemon, licorice)

- “Peas & Carrots” (custard, chips, cocoa nibs)

- “Octopus” (‘nduja, celery root, Vidalia)

- “Pistachio” (peach, gorgonzola, nutmeg)

- “A5 Wagyu Ribeye” (tamarind, jackfruit, Thai basil)

- “Lamb” (ratatouille, buddha’s hand, mint)

- “Veal Cheek” (chocolate, white pumpkin, yuzu)

- “Verjus” (buttermilk, strawberry)

- “Prickly Pear” (lime, shiso)

- “Apricot” (sunflower, lemon, olive oil)

- “Cherry Blossom” (cherry, tonka, white chocolate)

- “Chocolate” (golden beet, hibiscus)

While the dawn of 2021—and the passing of Temporis’s fourth birthday—would not yet offer a fresh start, the year would still be fruitful. In April, the restaurant once again retained its Michelin star in what must have represented a particular distinction for Jorge and Paternico, recognizing work imprinting their own style on the kitchen while stewarding the concept through such a difficult period.

2021 would also allow the chefs to further develop their cuisine through dishes like:

- “Canapés” (wagyu, hibiscus, osetra)

- “Wagyu” (soy, ginger, fresno)

- “Foie Gras” (strawberry, elderflower, mint)

- “Tomato” (cucumber, brioche, basil)

- “Holland White Asparagus” (rhubarb, brioche, oxalis)

- “Cauliflower” (truffle, curry, parsley)

- “Uni” (lobster, parmesan, lemon)

- “Red Mullet” (lobster, leek, lemon)

- “Duck” (cherry, green bamboo rice, tarragon)

- “Squab” (blueberry, polenta, fennel)

- “Venison” (fiddlehead, blackberry, cocoa)

- “A5 Wagyu Ribeye” (coffee, orange, bacon)

- “Yuzu” (ginger, black cardamom)

- “Huckleberry” (lemon verbena, goat’s milk, earl grey)

- “Chocolate” (tahini, red wine)

- “Mignardises” (black currant & lavender pâte de fruit, pineapple doenjang bonbon)

2022—and the passage of the restaurant’s fifth birthday—would tell a similar story: Temporis retained its Michelin star in April while being nominated for “Best Pastry Program” (alongside Adorn, Aya Pastry, George Trois/Aboyer, and Kasama) at the Jean Banchet Awards that following May. Paternico, whom the nomination really (given the small size of the concept) honored, lost out to Kasama—nothing to be ashamed of given the year they had. And Jorge, more specifically, also earned a nomination for “Rising Star Chef” (alongside James Martin, Zubair Mohajir, Ian Rusnak, and Eric Safin), ultimately losing to Ethan Lim. The price of the tasting menu, like so many others throughout Chicago, would continue to creep up in price (to $175). However, the year would offer the kitchen a chance to continue growing without the same fear of lockdowns and pandemic pivots.

Dishes from 2022 include:

- “Canapés” (wagyu, osetra, passion fruit)

- “Golden Kaluga” (parsnip, buddha’s hand, sumac)

- “Foie Gras” (blueberry, granola, pink lemon)

- “Beet” (pistachio, goat cheese, persimmon)

- “Holland White Asparagus” (rhubarb, brioche, egg yolk)

- “White Pumpkin” (maple, apple, pumpkin seed)

- “Octopus” (potato, fennel, lemon)

- “Peas & Carrots” (cocoa, custard, marigold)

- “Caviar” (banana, coconut, miso)

- “Lobster” (uni, parmesan, seacress)

- “Black Cod” (lime, coconut, lemongrass)

- “Turbot” (piquillo pepper, artichoke, parsley)

- “Black Cod” (piquillo pepper, artichoke, parsley)

- “Pork Belly” (lime, coconut, lemongrass)

- “Lamb” (black garlic, sumac, sour orange)

- “Squab” (strawberry, elderflower, sorrel)

- “Australian Wagyu Cheek” (apple, date, yuzu)

- “Westholme Wagyu Ribeye” (morel, hibiscus, sea buckthorn)

- “Pomegranate” (spruce tip, sudachi)

- “Omija” (kumquat, coconut, lime)

- “Kabosu” (guava, white chocolate, matcha)

- “Cantaloupe” (lime leaf, goat’s milk)

- “Nori” (cucumber, yuzu, white chocolate)

- “Truffle Opera Cake” (buckwheat, cassis, caramélia)

- “Basil” (Meyer lemon, dark chocolate, black mint)

- “Mignardises” (pear & fennel pollen pâte de fruit, cinnamon roll bonbon)

- “Mignardises” (calamansi gummy, mojito bonbon)

- “Mignardises” (strawberry & spruce tip pâte de fruit, chai bonbon)

When you consider this range of preparations, it is finally possible to see some of the ingredients and ideas that have defined Jorge and Paternico’s work over the past few years. For the former, you may note an enduring love of foie gras, white asparagus, octopus, lobster, pork belly, and wagyu. “Peas & Carrots” seems like a particularly canonical recipe (being brought back from 2020) while favored ingredient combinations like “lime, coconut, lemongrass” and “piquillo pepper, artichoke, parsley” have been utilized across different proteins. Herbs from the hydroponic garden still seem to appear but are no longer featured as prominently as fruit like apple, banana, blueberry, date, passion fruit, pink lemon, sour orange, strawberry, and yuzu throughout the savory fare. This also holds true for Paternico’s pastry work, which retains a marked Asian influence (“Omija,” “Kabosu,” “Nori”) while highlighting herbs, fruit, and various styles of chocolate. Of course, the pâte de fruit and bonbon forms are clear favorites too (with the mojito version of the latter calling back to Jorge’s very first menu).

Today, in 2023, Temporis has passed its sixth birthday and is rapidly approaching its seventh. Bibendum has reverted to releasing his stars in the fall, so you have not yet received the annual confirmation that the restaurant has maintained—or maybe even surpassed—its usual high standard. And Jorge’s tasting menu, it should be said, has now climbed to $215 per person.

Temporis is now quietly in that period of middle age you previously spoke of, pleasing the majority of its customers (with a bit of occasional dissent) while escaping any larger attention. In truth, it is rather difficult to compete with new openings, first-time Michelin honorees, and those two- and three-star establishments that cast their shadows over Chicago’s dining scene when it comes to attracting eyeballs. Really, does anyone but Bibendum hold the power to say “look,” nearly seven years on, “this place really deserves diners’ attention” (even if it does not fit neatly into a fashionable market category)? Yet, at what point does that star and alphabetical position in the Guide just become a listing your eye familiarly skips over in search of a newer, shinier restaurant?

By your measure, Jorge, Paternico, and Plotnick have achieved a rare degree of permanence and stability that, when combined with a small 20-seat concept, excite you. Temporis is past the point of needing to please the food media or the lemmings that follow their recommendations. The kitchen, perhaps with one eye watching out for Michelin’s inspectors, can simply cook, and it can do so within a “contemporary American” genre that offers untold possibilities.

This is a restaurant—three executive chefs in—without a well-defined brand or an obvious story to tell. In some sense, it is a throwback (despite not really being that old) to an era when fine, modern cuisine could stand as an attraction without leaning on a particular ethnic identity, a photogenic ambiance, or visual gimmicks to get customers through the door. There’s a sense of freedom here—an aspect of the undefined and undefinable—that actually reminds you of a top new opening like Valhalla (without the associated baggage). However, Jorge and Paternico have had far more time to explore and refine their ideas, and the resulting work only demands that someone see Temporis not as a one-and-done, Michelin-starred experience but a dynamic restaurant worthy of serious, continued attention.

You have visited Temporis a handful of times over the years (including several meals during Young’s tenure) but will restrict the scope of this article to a series of three dinners conducted from July through September of 2023. This more narrow focus will enable you to sidestep the narrative of the changing chefs and highlight exactly how the restaurant’s experience, today, ranks among its peers. It also allows you to track just how quickly Jorge’s menu changes during a key point between seasons.

With that said, let us begin.

The stretch of Ashland Avenue bounded by Chicago Avenue (to the south) and Augusta Boulevard (to the north) is, as you have already mentioned, rather subdued. Unless something brings you to the high school, the dentist, or one of the salons on the block, you’d buzz by its assembled businesses with nary a thought. Even real estate agents (always desperate to trumpet this or that distinguishing factor) term Noble Square (where Temporis technically lies) a “blink and you’ll miss it” neighborhood. Others claim the area’s identity may be altogether “disappearing” as its north and south sections get subsumed into Wicker Park and West Town respectively.

Yes, Temporis feels isolated in this liminal part of the city, reflecting not only the passage of time but the transformation of space as a relatively unknown community gets slowly swallowed up by its more fashionable neighbors. But is this not just a matter of definition? The residents of Noble Square still enjoy their quiet nook just west of the highway, and they surely enjoy having access to places like All Together Now, Boeufhaus, KAI ZAN, Parson’s, Provaré, Split-Rail, Tortello, and Wazwan well within reach. Even the riches of Logan Square and West Loop, truth be told, are not all that far away.

This is an area defined by access to a bevy of the city’s best restaurants as much as it is by what is on your particular block, and those who crave fine dining can easily find their way to Elske, Ever, Oriole, or Smyth in as little as five minutes. Nonetheless, the immediate area is defined more by Kasama (with its daytime operation and $255 nighttime tasting menu) and Porto (with à la carte fare and a $120 set menu of its own). These Michelin-starred concepts are among the most recent in Chicago to receive one of Bibendum’s high honors. They each put forth a very particular kind of cuisine (“Filipino-inspired” and Galician/Portuguese respectively) that engages a clear sense of novelty.

Temporis, by comparison, is a relative institution: the “progressive American” place around the corner promising a straightlaced fine dining experience with no smoke, no mirrors, no pigeonholing into a set theme. Sitting in the restaurant’s dining room and looking through the curtain out onto the street, you note just how many passersby (often towing dogs) stop to peer into the space. “Why are the lights so dim and the tables set so far apart in there,” they no doubt ask themselves (unable to discern much more than the outline of wine glasses and plates). Visually, the building’s façade, unlike its brick-clad brethren on the block, is rendered in matte black stone with columns on the corners. The door, in contrast, is done in a rich shade of brown while each of the windows is set with uneven segments of white wood that, forming right angles, give the impression of patchwork. That name—“Temporis”—reveals little but evokes a Latinate formality. Turning to Google, such a passerby may learn the place offers “creative New American” tasting menus and wine pairings at a premium price point.

This sense of mystery (combined with the relative friendliness that “American” cuisine signals) could, maybe, be enough to get some percentage of the looky-loos through the door. Of those people who are willing to spend $215 per person on dinner, surely some are inclined to try the place next door whose popularity (depending on the proportion of those 20 seats that are filled) has been affirmed firsthand. However, it seems more likely that prospective diners have scanned the Michelin Guide and settled on Temporis as the best of countless options (or at least the one, right now, that allows them to say they have tried them all).

That $215 ticket price (exclusive of a 20% “service charge”) ranks higher than Galit ($88), Sepia ($95), Elske ($125), North Pond ($125), Kyōten Next Door ($159), Atelier ($165-$195), Schwa ($165-$195), Topolobampo ($165), Boka ($175), Goosefoot ($175), Next ($175-$195), EL Ideas ($185), Valhalla ($188), and Mako ($195) at the one-Michelin-star level but lower than Omakase Yume ($225) and Esmé ($235-$265). It even costs more than Smyth’s truncated “Classic” menu ($175), but it is worth considering that Temporis has started to offer its own “abridged” menu ($135) every other Wednesday.

This is all to say: the restaurant is among the most expensive in its category and even knocks on the door of two-Michelin-starred concepts like Moody Tongue ($285), Smyth ($285), Oriole ($295), and Ever ($325). “Why not spend $75-$110 more to ascend to what Bibendum has ‘objectively’ declared to better?” some consumers may ask. These places are also “contemporary American” in style and, assuming a lack of price sensitivity when it comes to planning that special occasion, promise a fine dining experience that is just a little more “fine.”

Yet, other consumers may perceive that second or third Michelin star as reflecting a certain stuffiness, and they may see value in selecting one of the pricier, more elongated tasting menus out of the one-Michelin-star “contemporary American” bunch (Sepia, North Pond, Atelier, Schwa, Boka, Goosefoot, EL Ideas, Valhalla). None of these concepts are wedded all too strictly to a particular theme, and it follows that Temporis—costing more—will deliver more (vis-à-vis portion sizing and luxury ingredients). Such logic calls a car lot to mind: is it better to get a fully-loaded entry-level model or squeeze your way into the stock version of a more premium machine? When you consider the incidence of supplemental courses and the near necessity of purchasing beverages, those two- and three-Michelin-star properties can quickly balloon in price. Just the same, the $75-$110 per person difference to get you in the door represents just about what it takes to secure a wine pairing at Temporis.

Whatever the logic that brings you there, expectations will necessarily run high as you approach 933 North Ashland. This is one of Chicago’s most expensive dining experiences, and Temporis reveals very little of its substance until you see, smell, and taste it for yourself.

The restaurant’s building, once you have chosen to seek it out, feels more or less fitting. The setting is certainly not picturesque like North Pond, but it compares favorably to other establishments by occupying its own corner and standing proudly—but unostentatiously—there. The tones of black and white woodworking, likewise, satisfy the “contemporary” aesthetic while the warmer tone of the door, in turn, serves as a subtle welcome. This is not a palace—not a place to see and be seen—but an intimate, self-possessed space for the celebration of culinary artistry.

Stepping through the portal, you prepare to be transported. After traversing a short vestibule, you find yourself there: a sleek, minimalist restaurant that is more or less encapsulated in one single room.

Immediately before you stands a pony wall rendered in a cool, gray gradient. A full-sized wall, centered behind it, is painted white and features irregular grooves that call the patterns in the windows to mind. A few larger cubbyholes contain vases and plant life bathed in yellow light while, off to one side, red Michelin plaques hang as a reminder of Temporis’s pedigree.

Otherwise, this pony wall, which wraps around along the other side, doubles as a host stand and a service station. Wine bottles are strategically positioned at one end of the service while a trio of ice buckets are ergonomically tucked in an alcove facing the diners. Beyond the rear wall, a passageway leads to the kitchen: a tight but tranquil work area that you only get the slightest glimpse of.

Before you can dwell much longer at the entrance, you are warmly greeted by longtime captain Laura Bonetti—a former opera singer, corporate trainer, and now “mother hen” of Temporis. She receives your party with the confidence and charm that can only come with anticipation, recognizing your reservation (there are only 20 seats spread across five timeslots after all) before you even need to provide a name. Compared to some fine dining host stands, two or three cold, suited employees deep, that make you feel like you are facing a firing squad, entering here feels effortless and immediately comforting.

Taking just a few steps sideways, you find yourself in the middle of the dining room: a set of three freestanding two-tops running along the vestibule and kitchen walls with a pair of banquettes (seating eight and six in various configurations) opposite them. The color palette mixes whites (the walls, chairs, ceiling, and curtains), grays (the banquettes and carpeting), browns (the tables and a dividing wall that doubles as glassware storage), and black (some of the other walls) with bursts of polished metal and warm lighting from wall-mounted lanterns. Otherwise, some additional right-angled grooves continue to extend the pattern seen in the windows while a couple pieces of abstract art—painted in blocks of bluish-green—form a thoughtful contrasting element.

To the rear of the dining room, past a curtain, you find a set of bathrooms designed with the same grayscale tones and stocked with Temporis-embroidered towels, an LED-embedded mirror, a grided mirror wall fixture, a stock of toiletries, and a solitary pot of flowers.

Though the restaurant failed your “towel test” (a challenge that, in truth, demands a level of staffing and attention to detail that you would not expect from such an intimate concept) these backstage areas feel impressively luxe and totally pristine. If there’s a prototypical “Michelin-starred bathroom,” it would be very close to this.

And, overall, you find Temporis’s ambiance to be attractively cohesive and understated. Nothing here quite screams “luxury,” but there is a consistent layering of motifs and materials that sets a refined, curated tone. It feels comfortable—not quieting—to sit in the space, and the details (particularly the plant life and use of wood) articulate how the restaurant marries contemporary, minimalist design with an enduring sense of nature. Ultimately, this amounts to a visual representation of the restaurant’s culinary identity: “the passage of time” and the transcension of seasonality through the use of the hydroponic garden, which controls nature much in the manner those various vases are embedded throughout the cool, modern space. It also reminds you a bit of Ever (the hanging raw ingredients juxtaposed by the foreboding Lawton Stanley space) on a smaller, more humble scale. That seems serendipitous given Jorge’s experience working under Duffy, and it helps situate Temporis as part of a kindred “contemporary American” school.

Upon leading you to your seats, the captain inquires about water preferences and returns, in short order, to fill the glasses. Your server—one of three other front-of-house figures working the floor—also introduces themself around this time. Given that Temporis serves one solitary tasting menu, there is not too much ground to cover. They stoke your excitement for the 11 courses to come, double check any dietary restrictions, and offer any applicable supplements (which have included caviar and wagyu in the past but not during your particular visits). They also broach the prospect of beverage pairings, a key part of the restaurant’s identity since opening that today exists in a surprisingly elaborated form.

When booking dinner through Tock, Temporis prompts you to choose one of four pairing options but also assures “guests are welcome to chose [sic] upon arrival.” Of course, there are wines by the glass and by the bottle to consider too. Yet, many consumers (especially those for whom this kind of dining is still entirely novel) will be drawn toward a turnkey solution: select and pay for everything now then simply sit back and relax when it comes time for dinner. You can see the logic there, and you even understand why certain experiences (like Smyth’s Chef’s Table) demand that you commit to one of two higher priced pairings.

Encouraging (or enforcing) these choices ensures a certain minimum spend while empowering a restaurant to strategically open and pour expensive bottles with as little wastage as possible. For that reason, you sometimes assume that committing to a premium pairing in advance will help secure a superior selection. The restaurant, in this manner, need not scramble during service to open bottles that fit the bill but can carefully curate an assortment of wines over a longer period of time (using a Coravin or other preservation systems) that puts its program’s best foot forward.

You thought this might be the case with Temporis’s “Grand Reserve Pairing” ($325), which is priced beyond Oriole’s top “Reserve” pairing ($285) and only surpassed by Smyth’s “Super Mega” ($355) and Alinea’s “The Alinea Pairing” ($395) options within Chicago. This is quite glitzy company to be in, and you naturally wondered how frequently a 20-seat restaurant with only one Michelin star was actually pouring such a superlative splurge. Prior committal, thus, seemed like the polite thing to do, and you eagerly awaited the vinous delights Temporis would have in store. However, not only did the “Grand Reserve Pairing” ultimately disappoint you (more on that in a bit), but you came to learn that the restaurant offers a printed comparison of each of the options if you delay making your choice until the night of the reservation. They even allow diners to split pairings by ordering a half-pour version! So, in truth, there is little reason to commit on Tock when you can make a more informed decision in person.

The pairings offered during the course of your visits have included:

Spirit Free Pairing ($75)

- “Chamoy” (peach, mango, bay leaf)

- “Basil” (elderflower, lemon, parsley)

- “Lapsang” (orange, star anise, cinnamon)

- “Guajillo” (verjus rouge, cherry bitters)

- “Coffee” (rosemary, orange)

Standard Pairing ($115)

- R.H. Coutier Blanc de Blancs Grand Cru Brut Champagne

- 2021 Luis Pato Vinhas Velhas Branco

- 2021 Guy Breton “Cuvée Marylou” Beaujolais-Villages

- 2018 Clos Figueras “Font de la Figuera” Priorat

- 2020 Domaine de la Bergerie “Le Clos de la Bergerie” Coteaux du Layon

Reserve Pairing ($175)

- André Heucq “Héritage” Blanc de Meunier Brut Nature Champagne

- 2017 Bernard Moreau et Fils Saint-Aubin “Sur Gamay” Premier Cru

- 2018 Bruno Clair Fixin “Champ-Perdrix”

- 2017 Il Colle Brunello di Montalcino

- 2021 Weingut Keller Rieslaner Auslese

Grand Reserve Pairing ($325)

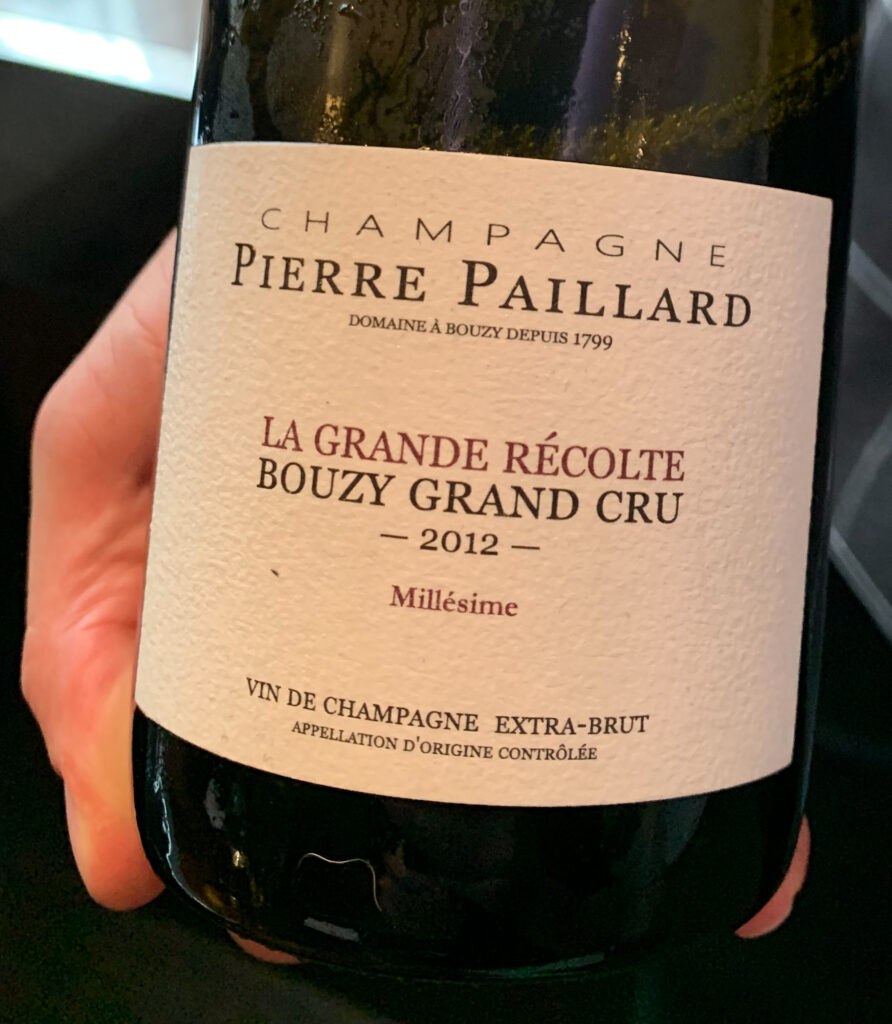

- 2012 Pierre Paillard “La Grande Récolte” Grand Cru Extra Brut Champagne

- 2009 Malat “Gottschelle” 1ÖTW Grüner Veltliner

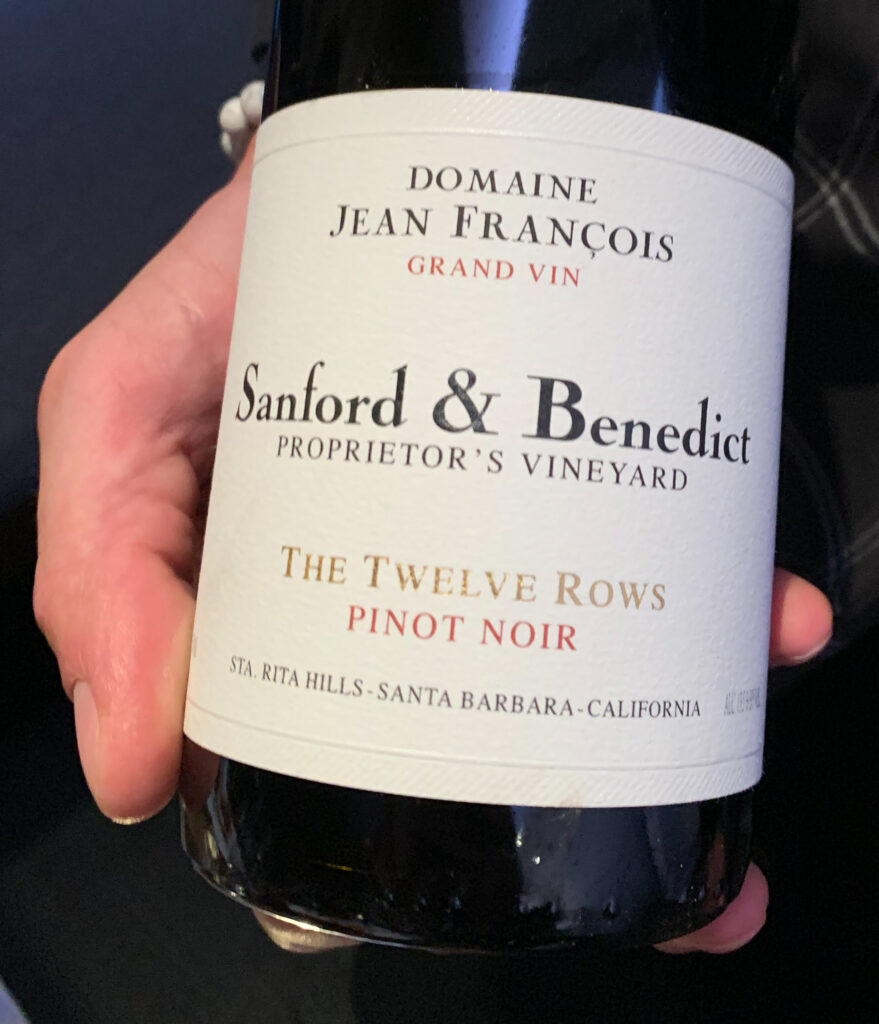

- 2019 Domaine Jean Francois Sanford & Benedict “The Twelve Rows” Pinot Noir

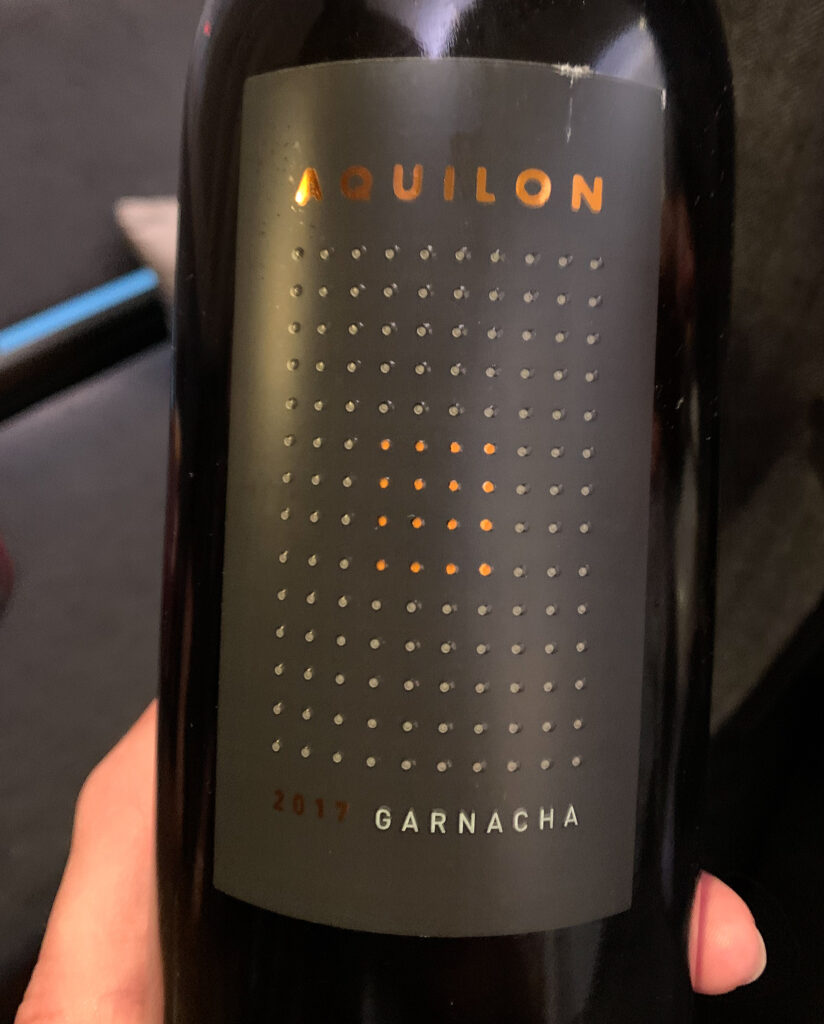

- 2017 Alto Moncayo “Aquilon” Campo de Borja Garnacha

- 2013 Kracher “No. 1 Nouvelle Vague” Rosenmuskateller Trockenbeerenauslese

Now, having tried the “Spirit Free Pairing,” you would say that the drinks are competently executed and worth the money (for those avoiding alcohol) if not quite rising to the level of places like Ever or Oriole. Most of them make use of Seedlip products as a base but harmonize nicely with their chosen dishes (e.g., basil with a tomato-focused dish or star anise with a Pernod-spiked preparation of lobster). While the “Chamoy” tastes a bit muddled to you, the “Guajillo” is the best of the bunch with full, only faintly sweet Kool-Aid flavor to match the headlining preparations of meat. The closing “Coffee,” made with decaf Sparrow beans, offers a play on an espresso martini that looks every bit the part. It cannot quite replace the real thing but will likely delight teetotalers who are otherwise unable to enjoy such a trendy cocktail.

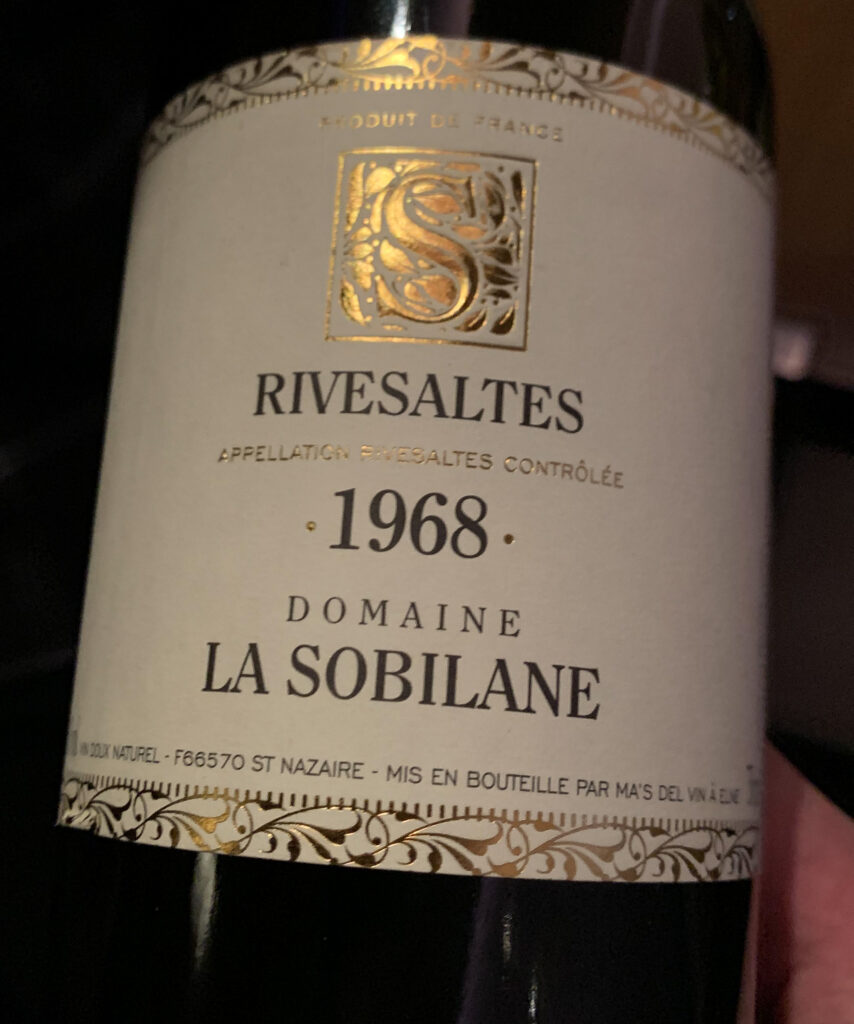

Turning toward the alcoholic options, it should be kept in mind that Temporis offers healthy pours of these five wines so that they may stretch over multiple courses. And, when you consider that seven of the 11 dishes on any given night are savory, that means you get one sparkling, one white, and two reds to carry you through the heart of the meal. Such a format may make for a pairing that is less varied and engrossing at the end of the day; however, theoretically, it should also help to ensure a higher overall quality of product while limiting the number of bottles that could potentially spoil due to a lack of adequate interest.

On paper, you actually find both the “Standard” and “Reserve” pairings to be quite strong. They balance top-value producers (Coutier, Heucq, Pato, Breton) with name recognition (Moreau, Clair, Keller) while ticking all the traditional boxes: Champagne, Chardonnay (or something like it), Pinot Noir (or something like it), a heavier red, and something to go with dessert. Truthfully, when you consider the expressiveness of the Blanc de Meunier style of Champagne and the relative age of its two Burgundies (2017 and 2018), the “Reserve Pairing” represents a rare sweet spot in the lineup. While still being priced at less than the cost of the tasting menu itself (and backed up by a “Standard” option that is by no means an afterthought), it may even rank among the best of these premium offerings in all of Chicago.

By virtue of its price, the “Grand Reserve Pairing” should have delivered an even greater degree of pleasure than its more approachable brethren. However, its selections left you feeling cold in the moment and positively gipped with further reflection. Yes, you actually found yourself coveting the 2021 Weingut Keller Riesling you saw being poured (at the time) for other patrons as part of their “Reserve Pairing.” And, later seeing the breakdown of each flight side by side, you feel that Temporis is a bit guilty of needless premiumization.

For example, while the 2012 Pierre Paillard Champagne shines as a vintage-dated offering (relative to the non-vintage Coutier and Heucq), it has recently been released onto the market ($169.99) and does not really reflect any special degree of maturity. The same goes for the 2019 Jean Francois and 2017 “Aquilon,” wines that are still widely available at retail (for $114.96 and $179.99 respectively). While the 2009 Malat Grüner Veltliner does offer the kind of age and rarity you are after—at least as a distinguishing factor—the wine is from a fairly unknown producer and typically retails for around $45. The Kracher, instead, is from a well-known producer and can claim a bit of age. However, it is not quite unique and is not capable of carrying such an expensive pairing by itself.

Surely, your personal wine preferences may play a part in shaping your perception here. And, to be fair, those two Burgundies you like from the “Reserve Pairing” are available locally at retail (for $74.96 and $59.00 respectively). Yet, with the “Grand Reserve Pairing,” you get the sense that the restaurant has simply sought to offer more expensive bottles for the sake of doing so. Whether that is intended to sneakily divert consumers toward the middle category (which now seems like a relative deal) via anchoring or to simply allow certain “special occasion diners” to feel extra special (with a guaranteed 20% service charge sprinkled on top) is uncertain.

Really, the “Grand Reserve Pairing” is not deceptive in any way so much as it is uninspiring. It lacks the sense you are being poured a pleasant surprise—and, thus, receiving good value—that the other selections maintain. Thus, rather than searching for current release wines that retroactively satisfy “splurge” pricing, Temporis would do better by drawing more on the aged bottles in its cellar or excising this option altogether. For, any diner willing to invest in such a premium pairing is not the kind of customer a restaurant can stand to disappoint (no matter the short-term gain). At this price, any misgivings may even run the risk of spoiling any positive impression of Temporis’s food.

Nonetheless, the restaurant’s à la carte beverage options offer oenophiles—at least those who want to go beyond the “Standard” and “Reserve” pairings—some relief. The selection begins with a range of classic cocktails (like a “Negroni,” a “Manhattan,” and an “Old Fashioned”) and the more colorful “Chicago Franken Spritz” (Prosecco, grapefruit liqueur, Malört, lemon, soda). There is also a small assortment of beers (predominantly sourced from Chicago and the wider Midwest) along with a couple premium ciders.

The range of wines offered by the glass do not seem like much to write home about on the surface:

Champagne

- 2014 Gramona “Imperial” Brut Cava ($23)

- André Heucq “Héritage” Blanc de Meunier Brut Nature Champagne ($37)

White

- 2019 Martin Woods “Hyland Vineyard” McMinnville Riesling ($21)

- 2019 Emile Beyer “Tradition” Alsace Pinot Gris ($15)

- 2021 Pax Mahle “Lyman Ranch” Amador Chenin Blanc ($23)

- 2019 Mount Eden Vineyards “Wolff Vineyard” Edna Valley Chardonnay ($20)

- 2020 Vincent Gaudry “Le Tournebride” Sancerre ($25)

Rosé

- 2022 Domaine de Fontsainte “Gris de Gris” Corbières ($15)

Red

- 2021 Guy Breton “Cuvée Marylou” Beaujolais-Villages ($16)

- 2018 Russian River Vineyards Sonoma County Pinot Noir ($20)

- 2015 Terre Rouge “Les Côtes de l’Ouest” California Syrah ($14)

- 2020 Tyler Happy Canyon of Santa Barbara Cabernet Sauvignon ($31)

Dessert

- Château de Laubade Floc de Gascogne ($8)

- Jean Bourdy “Galant des Abbesses” ($19)

- David Ramnoux Pineau des Charentes ($12)

However, even when you consider that a couple of these bottles appear as part of the pairings, this is actually a smart selection. It is representative of all the major grape varieties (including a few eclectic sweets) while offering pours with a bit of age from notable producers and regions. None of these wines will necessarily send nerds’ tongues wagging, but you also don’t see them being served all over town. With the feeling that you are drinking something that is at least a little bit unique, you can get a decent Chardonnay or Pinot Noir for $20. Thus, imbibing few of these glasses may present an attractive value for diners who do not want to spend $115 on the “Standard Pairing” (or even spend $57.50 on half-pours).

That being said, the bottle list is where lovers of wine will find themselves richly rewarded. The following represent some of the collection’s highlights:

Sparkling

Jean-Luc Mouillard Crémant du Jura ($90)

R.H. Coutier Grand Cru Rosé Champagne ($140)

Lacourte-Godbillon “Mi-Pentes” Premier Cru Champagne ($150)

Vilmart & Cie “Grande Réserve” Premier Cru Champagne ($150)

Billecart-Salmon Brut Rosé Champagne ($185)

2009 Jacquart Blanc de Blancs Champagne ($185)

Pierre Moncuit Blanc de Blancs Grand Cru Champagne ($185)

2014 Paul Bara Grand Cru “Millésime” ($200)

Egly-Ouriet “Les Vignes de Vrigny” Premier Cru Champagne ($215)

2002 Thiénot “Cuvée Alain Thiénot” Champagne ($245)

2007 Philipponnat “Clos des Goisses” Champagne ($350)

Krug “Grande Cuvée” Champagne ($420)

2013 Pol Roger “Sir Winston Churchill” Champagne ($580)

White

2014 Reichsgraf von Kesselstatt Riesling Kabinett ($85)

2020 Antoine Jobard Aligoté ($90)

2021 Massican “Annia” White Blend ($90)

2010 Joh. Jos. Prüm Graacher Himmelreich Riesling Spätlese ($100)

2021 Weingut Keller Riesling Trocken ($105)

2021 Weingut Keller “Limestone” Riesling Kabinett ($115)

2016 Domaine Huet Vouvray “Le Mont” Demi-Sec ($130)

2018 Maximin Grünhaus “Abtsberg” GG Riesling ($135)

2021 Weingut Keller “Von der Fels” Riesling ($135)

2020 Nicolas Jay “Affinités” Chardonnay ($140)

2018 Dönnhoff Niederhäuser Hermannshöhle Riesling Spätlese ($150)

2017 François Carillon Puligny-Montrachet ($185)

2014 Peter Michael “Mon Plaisir” Chardonnay ($195)

2020 Aubert “Larry Hyde & Sons” Chardonnay ($215)

2015 Kongsgaard Chardonnay ($230)

2016 Nicolas Joly Clos de la Coulée de Serrant Chenin Blanc ($240)

2020 Antoine Jobard Saint-Aubin “Sur le Sentier du Clou” Premier Cru ($265)

2018 Didier Dagueneau Pouilly-Fumé “Silex” ($270)

2019 François Raveneau Chablis ($285)

2018 Vincent Dauvissat Chablis “Les Preuses” Grand Cru ($320)

2020 Antoine Jobard Meursault Blagny Premier Cru ($420)

2013 Trimbach Clos Ste. Hune Riesling ($515)

2020 Weingut Keller “Westhofen Kirchspiel” GG Riesling ($520)

2020 Weingut Keller “Abts E®” GG Riesling ($520)

2015 Jean-Marc Roulot Meursault “Les Vireuils” ($560)

Red

2020 Grégoire Hoppenot Morgon “Corcelette” ($100)

2011 Domaine du Collier Saumur “La Charpenterie” ($165)

2016 Jean-Marc Morey Beaune “Les Grèves” Premier Cru ($175)

2017 The Eyrie Vineyards “Daphne Vineyard” Pinot Noir ($175)

2019 Weingut Keller “Reserve” Spätburgunder ($185)

2019 Nicolas Jay “Own-Rooted” Pinot Noir ($195)

2015 Paolo Bea Montefalco “Pipparello” Riserva ($195)

2018 Chappellet Cabernet Franc ($210)

2018 Bruno Clair Chambolle Musigny “Les Veroilles” ($240)

2015 Paolo Bea Montefalco “Pagliaro” ($240)

2016 Auguste Clape Cornas “Renaissance” ($250)

2009 Marqués de Murrieta Rioja “Castillo Ygay” Gran Reserva Especial ($250)

2006 Château de Beaucastel Châteauneuf-du-Pape ($260)

2009 Jean-Claude Boisset Chambolle Musigny “Les Chardannes” ($260)

2012 Marchesi di Grésy Barbaresco “Camp Gros” Riserva ($270)

2009 Maison Bertrand Ambroise Clos Vougeot Grand Cru ($310)

2014 Sea Smoke “Ten” Pinot Noir ($310)

2013 Continuum Cabernet Sauvignon ($390)

2017 Elena Walch “Aton” Riserva Pinot Noir ($390)

2018 Thierry Allemand Cornas “Reynard” ($560)

2015 Sine Qua Non “Le Chemin Vers L’Hérésie” Grenache ($570)

2018 Opus One ($575)

2007 Giuseppe Quintarelli Amarone della Valpolicella Classico ($600)

1985 Château Cos d’Estournel ($750)

2018 Poggio di Sotto Brunello di Montalcino ($750)

1989 Château Montrose ($800)

2013 Hundred Acre “Ark Vineyard” Cabernet Sauvignon ($850)

1990 Château La Conseillante ($1,000)

2006 Château Margaux ($1,200)

1990 Château La Mission Haut-Brion ($2,000)

1990 Château Haut-Brion ($2,500)

By your measure, the sparkling wines may amount to the weakest part of the selection. Nonetheless, bottles like the Vilmart “Grande Réserve” ($150 on the list, $70 Wine-Searcher average), Egly-Ouriet “Les Vignes de Vrigny” ($215 on the list, $109.99 retail price), Philipponnat “Clos des Goisses” ($350 on the list, $253 Wine-Searcher average) and Pol Roger “Sir Winston Churchill” ($580 on the list, $348 Wine-Searcher average) appeal to a range of price points while maintaining markups that are right around 100% or sometimes even as low as 60%-70%. While the restaurant’s 20% service charge should be kept in mind, this restrained approach to pricing—especially when you consider the special premium Champagne usually commands—is commendable.

Turning toward the whites, you find even more to get excited about. Yes, all those bottles of 2020 Antoine Jobard and 2021 Keller are more or less current release, but these allocations form a nice foundation for the list and are generally offered around that 100% markup (if not less). (The “Limestone” Kabinett, which costs $115 and retailed for $42 in Chicago, and the “Von der Fels,” which costs $135 and retailed for $54 in Chicago being notable exceptions.)

But it is aged selections like the 2010 Prüm Spätlese ($100 on the list, $61 at auction), 2017 François Carillon Puligny-Montrachet ($185 on the list, $127 Wine-Searcher average), 2014 Peter Michael “Mon Plaisir” ($195 on the list, $139.97 at retail), 2015 Kongsgaard ($230 on the list, $195 Wine-Searcher average), and 2019 Raveneau Chablis ($285 on the list, $249.99 at retail) that impress you most.

Even the most expensive bottles—like the 2018 Dauvissat Chablis “Les Preuses” ($320 on the list, $365 Wine-Searcher average), 2013 Trimbach Clos Ste. Hune ($515 on the list, $341 Wine-Searcher average), 2020 Keller “Abts E®” ($520 on the list, $454 Wine-Searcher average), and 2015 Roulot “Les Vireuils” ($560 on the list, $428 Wine-Searcher average)—offer great value. You must consider that retail and auction prices for these wines have continually risen due to currents of scarcity and speculation. However, Temporis deserves credit for not revising its markups but, rather, patiently cellaring these bottles until the right customer comes along.

This same trend can be noted among the red wines, with bottles like the 2011 Domaine du Collier ($165 on the list, $179 Wine-Searcher average), 2018 Bruno Clair “Les Veroilles” ($240 on the list, $166 Wine-Searcher average), 2018 Allemand “Reynard” ($560 on the list, $413 Wine-Searcher average), 2018 Opus One ($575 on the list, $394 Wine-Searcher average), 2007 Quintarelli Amarone Classico ($600 on the list, $550 Wine-Searcher average), and 2013 Hundred Acre “Ark Vineyard” ($850 on the list, $813 Wine-Searcher average) falling a sweet spot where they would almost cost the same outside of the restaurant.

Those legendary aged Bordeaux—like the 1989 Montrose ($800 on the list, $710 Wine-Searcher average), 1990 La Conseillante ($1,000 on the list, $499 Wine-Searcher average), 2006 Margaux ($1,200 on the list $738 Wine-Searcher average), 1990 La Mission Haut-Brion ($2,000 on the list, $1,126 Wine-Searcher average), and 1990 Haut-Brion ($2,500 on the list, $1,283 Wine-Searcher average)—also fall at (or well under) that 100% markup despite enjoying greater price stability.

While there is also a sprinkling of more approachable Pinots from Jean-Marc Morey, The Eyrie Vineyards, and Nicolas Jay that reflect the same minimal markups, Temporis’s wine list is—at the end of the day—tailormade for connoisseurs. That is not by any means a bad thing. Frankly, it delights you. For, considering that the restaurant’s notable bottles start in the $100-$150 range, entry-level consumers will be easily drawn toward the “Standard Pairing” ($125) or “Reserve Pairing” ($175) as a turnkey solution rather than contend with picking one or two wines on their own. Oenophiles, who have typically learned to distrust pairings through painful experience, can—in contrast—use that $125, $175, or even $325 (for the “Grand Reserve”) to secure one or two attractive aged selections of their own choosing.

The math tends to work out so long as you commit to spending a couple or a few hundred dollars on a bottle, at which point some of the very lowest (relative) markups come into effect. However, even customers choosing to order something à la carte close to $100 can be assured they are not being grossly upcharged. This pervading sense of value, whether ordering a pairing or delving into the bottle list yourself, is where Temporis’s beverage program shows its real strength. After getting you in the door, the restaurant does not squeeze you for a little extra lucre but, rather, affirms wine’s role as a friendly, engaging companion through which to celebrate fine food.

Of course, you have already mentioned your issues with the “Grand Reserve Pairing,” and oenophiles should not have to spend a comparable amount à la carte in order to feel that they have beaten the market by picking the best cherries off of the list. Some of Temporis’s aged wines have been offered since the restaurant’s opening, and stocking full cases in this manner—letting them slowly develop without increasing pricing—is the right way to run a program. Just the same, holding onto this much inventory can be difficult for a small place where only an even smaller proportion of guests are going to be purchasing bottles. For this reason, you would once more like to see Temporis draw on its more mature stock to create the “Grand Reserve Pairing” (at least when it comes to $150-$250 wines that are not likely to improve dramatically).

Such a move would really stand to impress patrons who opt for the most premium set of pours (rather than leaving them disappointed as in your case). It would also empower a bit more turnover of the bottle list and allow the restaurant to do more buying. Save for Riesling and a small amount of Chardonnay, you find the $100-$200 range in each of the sections to be a bit depleted. You would love to see more Grower Champagne on offer along with wines from the Jura, the Loire, and the Savoie. Even when it comes to Burgundy and domestic offerings, you think there is room for top-quality village-level offerings and producers who reflect a more expressive biodynamic or “natural” style of winemaking. These bottles would pair brilliantly with Jorge’s food and would allow the restaurant to continue offering superlative value (as the price of these products, in turn, comes to appreciate in time).

Still, this all just amounts to a wish list and does nothing to take away from the great work Coen has done with this program. Should you avoid the pitfall of the “Grand Reserve,” you are left with a by-the-glass selection, pairings (including a decent spirit-free option), and bottle list that rank favorably against any restaurant in town. While you did not personally confirm the possibility of corkage (listed online as $35 with no limit on the number of bottles), this seems like a fair sum given the value to be had with Temporis’s own offerings.

It should be mentioned, nevertheless, that Coen acts as a beverage director and, as such, is not seen working the floor. This, again, is understandable given the 20-seat format and the need to prioritize the everyday mechanics of service. However, it also means that the servers—in addition to filling water, running food, and conducting the general flow of your evening—are tasked with telling the stories of the chosen wines.

As far as the “Grand Reserve Pairing” goes, information of any enduring value was scarce. The descriptions provided for the wines deferred to general details like country of origin, vintage, grape variety, and vineyard designation (erste lagen, grand cru). Sometimes they highlighted a particular synergy with the food (Grüner with an herbaceous preparation of tomato, Grenache with a plate of wagyu). Most of these spiels—accompanied by knowing nods and smiles—failed to go beyond what an intermediate wino would consider self-evident: things that are written on the label and that form the fundamentals of classification and appreciation. You think a restaurant can get away with this when it comes to the $125 or even $175 pairings, but charging $325 demands a greater expression of expertise.