When you last left Stephen Gillanders, the chef found himself at the center of a maelstrom involving a service miscue, a concocted aggrievance, and a downright cowardly awards ceremony. While hardly the kind of headache any craftsman expects to endure, he stood admirably behind his besieged sommelier and revealed just how morally bankrupt those who purport to represent (let alone honor) the industry truly are.

The ”controversy,” many news cycles later, now just seems silly. Any hollow victory those terminally online activists won—lobbing death threats as their weapon of choice—has only damaged the credibility of the Jean Banchet Awards and its controlling Cystic Fibrosis Foundation. Why should an organization trade on the work of a community it has no intention of defending (or, at the very least, respecting enough to grant it some manner of due process)? Why should a community gather to celebrate itself when it shows no solidarity to those who, in the act of service, find themselves scapegoated? There is certainly no shortage of “benefactors” who wish to sink their promotional hooks into chefs, and you do not think it wrong—no matter the charitable trappings—to question what those who do so really stand for.

But Gillanders, certainly, has not missed a beat. Though others may contort themselves to tear people down—and organizations may care for nothing more than covering their ass—the chef has continued to create. He lavishes praise on the teams at S.K.Y. and Apolonia, showcasing each of their new dishes with obvious pride. But Valhalla has formed his new favorite child, and Gillanders has enthusiastically (and candidly) shared the details of his research and development for the concept. You do not just mean retrospectively describing what has made it onto the opening menu, but rather emphasizing the active growth of particular dishes and sharing his excitement about what is coming down the pike.

Gillanders’s voice, via this content, is distinctive, and the joy he feels for his work is infectious. These aren’t quite like Grant Achatz’s posts nostalgically revisiting creations from Alinea’s past. They do not embrace the nonchalance and naturalness that characterize John Shields and Noah Sandoval’s digital engagement. There’s certainly none of Otto Phan’s bluster or Erick Williams’s unique joviality. Yet Gillanders invites viewers into his process with an honesty and intimacy that transcends the glossy food styling typically used to get asses in seats. Certainly, the restaurant’s food offers that kind of visual appeal, but the dishes are—even through this early period—hardly frozen in time. Rather, you get a clear sense of the chef’s dynamism, and there’s not quite any other quality that induces return visits quite so effectively.

(You think only Michael Lachowicz, in his own inimitable way, comes close to offering the same peek behind the curtain—though one that centers rather touchingly on the emotional underpinnings of his approach to craft.)

However, Valhalla very much represents the culmination—at least for now—of a distinguished career, and it might be helpful to contextualize how the chef came to occupy Time Out Market’s cozy second-floor space.

Gillanders was born and raised in Los Angeles, where he “spent much of his childhood in the kitchen alongside his Filipino grandmother” and helped to prepare “authentic home dishes like lumpia.” After attending (at the suggestion of his mother) a summer program at the city’s Culinary Arts Institute, he knew—at the tender age of 15—he was meant to be a chef. After receiving his formal training in Los Angeles, Gillanders earned a B.S. in Culinary Arts Management at the University of Nevada, Las Vegas.

While there, the 21-year-old competed in S.Pellegrino’s 2004 Almost Famous Chef Competition, comprising student participants from “leading culinary schools in the U.S. and Canada” who are judged on “creativity, presentation, personality and their ability to perform under pressure.” Gillanders, preparing a dish of “Crispy Skin Cured Salmon with Parmesan Spinach Cakes, Yukon Gold Potato Puree, Mushroom Ragout, Smoked Salmon Rillette, and Port Beurre Rouge,” beat five of his UNLV peers to represent his region at the national finals. On that occasion, the same preparation would win him the “People’s Choice” and “Signature Dish” competitions, securing him first place overall along with the top prize: a trip to the Italian Culinary Institute for Foreigners and an appearance on The Today Show.

Gillanders would call the competition “a great experience” that helped him to learn about his “own capabilities under incredible pressure” as well as the nature of the field—“that it’s really all about satisfying people.” One of his lecturers, Dr. Jean Hertzman, would term him “a great chef and also a young man of exceptional character,” noting that “he brings a rare combination of talent and true personal enjoyment to his work that is the hallmark of a great chef.” Such a statement does not only speak to the young chef’s prodigious skill, but—you think—the very same enthusiasm that can be recognized in his social media content (to say nothing of tableside manner) to this very day.

On the back of this win and his subsequent graduation from UNLV, Gillanders took a position locally with Jean-Georges Vongerichten as a sous chef at PRIME Steakhouse in the Bellagio. That led, not long after, to an executive sous chef position at ARIA’s Jean-Georges Steakhouse. And, after proving himself at these luxe, high-volume venues, Gillanders would—after traveling “extensively throughout Asia and Europe to broaden his culinary repertoire”—get the call to come to New York City and start as the corporate executive chef of Jean-Georges Management in 2011. This more overarching role would charge him with overseeing “seven New York City restaurants” for the Alsatian master.

You are not sure if this included the (at the time) three-Michelin-star Jean-Georges restaurant in Columbus Circle (that you surmise is headed by its own dedicated executive chef). However, it is safe to assume that those high standards inform the work of the entire group and that Gillanders was exposed to the stylistic foundations that guide its work at the highest level. Besides, it should not be discounted how (surprisingly?) good concepts like ABC Cocina, ABC Kitchen, JoJo, and Perry St. can be (alongside a range of serviceable hotel restaurants like The Mark and The Mercer Kitchen that, at the very least, represent one of the industry’s most lucrative niches). The Alsatian even operated Spice Market—its menu “centered…around Southeast Asian street food”—back then (and through 2016).

You think it is fair to say that the Jean-Georges brand has suffered a bit with the expansion of its empire, with the flagship losing its third star in 2017 and those trendy hotel restaurants facing heightened scrutiny around the same time. However, the group was close to the peak of its powers in 2011, and Gillanders could count on engaging with a diverse array of crowd-pleasing spots within one of the world’s fiercest markets. He would also, across the various establishments, be inducted into Vongerichten’s particular sensibility: one that has combined the finesse of fine French technique with locally sourced ingredients and the chef’s particular flair for the cuisines of Asia.

More importantly, Gillanders’s role in New York would go beyond being a mere custodian of what his boss had already built. As corporate executive chef, he would open “nine restaurants, foreign and domestic” (including, not least of which, Vongerichten’s iteration of The Pump Room in Chicago’s Ambassador East Hotel). Stewarding a concept from the planning phase through its realization clearly comprises a whole different education when compared to the part one may play in well-established venues. Such experiences would not only provide Gillanders with greater ownership over his culinary work from start to finish, but also touch on the entrepreneurial and design aspects of the business. It is unclear exactly which restaurants Jean-Georges Management opened during this period (you count JG Tokyo as one), but, when accounting for the chef’s travels before arriving in NYC, he had been “from China to Japan to Vietnam, Thailand, South Korea, and the Philippines” when all was said and done.

After five years under Vongerichten in that corporate executive chef role, Gillanders was finally ready to strike out on his own. However, he did so savvily. Perhaps inspired by his time at The Pump Room (formerly and latterly a Lettuce Entertain You property), the Los Angeles native spread his wings in Chicago as Rich Melman’s fourth “rotating up-and-coming chef-in-residence” at Intro. In late 2015, he would follow in the footsteps of CJ Jacobson (of Aba and Ema), Erik Anderson (recently of COI), and Aaron Martinez (formerly of Addison, Quince, and Elizabeth, now a chef-partner in St. Louis) respectively, presiding over the former three-Michelin-star L2O kitchen (now a “school for entrepreneurs” as the LEYE honcho titled it).

The benefits of partnering with an established hospitality group—vis-à-vis staffing, promotion, and other overhead—for a first solo project are obvious. And Melman, quite the living legend as far as restaurateurs are concerned, promised “full creative license” to “implement the food concept as well as ambiance, service style, and more” with the “support and backing” of his whole organization. Gillanders, to his credit, would put the LEYE founder’s words to the test by breaking with the tasting menu format offered by the preceding trio of chefs. His à la carte selection would be “a little more approachable, a little more convivial” and make use of “ingredients not normally associated with fine dining” that, nonetheless, would be treated with “high-end techniques with the hope of producing big flavors.”

The menu, which also retained a five-course tasting menu drawn from the various options, featured dishes like “Crab Fritters” (with pickled ginger remoulade), “Kampachi Sashimi” (with black sesame ponzu), “Tuna Tataki” (with shallot cracklings), “Potato Soup” (with black truffle croquettes), “Baby Artichoke Risotto” (with Nishiki rice), “Wilted Kale Salad” (with roasted pepitas), “Sea Scallops” (with brown butter dashi), “Black Truffle Salmon” (with cauliflower variations), “Berkshire Pork Chop” (with collards), “Flatiron Steak” (beef & broccoli style), and “Parmesan Chicken” (with orzotto).

To your eye, this selection of items still reads rather well some seven years later. It would anticipate the blending of global cuisines that has now become more commonplace in Chicago while resisting that much-maligned “fusion” label. Instead, Gillanders showcased a worldly, ingredient-driven style defined—in your opinion—by the creativity of the second-, third-, and fourth-billed ingredients in each given preparation. Rather than representing needless exoticism, these elements naturally speak to what the chef had learned from his travels and the manner in which he is able to harmonize bits and pieces from different cultures in a cohesive, legible (to LEYE’s Lincoln Park demographic) way. You also think there’s little chance—looking at the comforting qualities of the entrées—of diners leaving hungry: a testament to the lesson learned from the Almost Famous Competition (“it’s really all about satisfying people”).

At the time of unveiling, it would be noted that Gillanders’s Intro menu would “almost” serve as a preview for his “own restaurant, S.K.Y. (it stands for his wife’s initials, and isn’t pronounced as the world)” that was “slated to open sometime next year [2016] in Los Angeles. However, the chef’s three-month chef-in-residence position grew into a “permanent role as chef/partner” that saw him provide continuity through the restaurant’s subsequent collaborations (like former Manresa chef de cuisine and James Beard Foundation “Rising Star Chef of the Year” awardee Jessica Largey).

This decision, while very much attuned to the spirit of camaraderie that fueled Intro from the start, would effectively spell the end of the rotating chef concept as originally envisioned. Rather than drastically changing tasting menus every few months, the à la carte format that Gillanders ushered in would provide—along with the chef/partner himself—a stable foundation for subsequent visitors to work with. For Lettuce Entertain You, this sense of stability would help the restaurant draw consistent business from the Belden Stratford’s residents and those in the surrounding neighborhood. Naoki Sushi, when it opened within L2O’s former private dining room, would further add to that appeal.

During the course of this evolution, Intro would—in February of 2016—be named a semifinalist for the James Beard Foundation’s “Best New Restaurant” award. Largey would end her residence in May, and it wasn’t quite clear whom LEYE had planned next. As best as you can tell, Gillanders debuted a new Korean menu (including “fluke sashimi, foie gras bibimbop, charred hangar [sic] steak with fermented red chili butter, and more”) in July to keep the concept fresh. By August, the restaurant could announce that Jonah Reider—who ran supper club Pith from his dorm room at Columbia University—would be cooking there for a month starting in September. He would be followed by Hisanobu Osaka (formerly of Japonais by Morimoto and then involved with Naoki Sushi) in November.

Somewhere in between, Gillanders would launch a “family-style dim sum menu” within Intro featuring “made to order” (and some non-traditional) items like “Peking Duck Steamed Buns,” “Imperial Tuna Poke,” “Longevity Noodles,” “8 Treasure Broccoli Salad,” “Thai Chicken Soup,” and “Mongolian Ribeye Steak” for an all-in price of $72. In January of 2017, this idea would be expanded upon as he teamed up with former chefs-in-residence CJ Jacobson and Aaron Martinez (who had stayed under the LEYE umbrella) to launch a full “modern dim sum” menu that would last “at least four months.” Intro, clearly, was starting to run out of steam as there just wasn’t enough new blood to keep the “incubator” concept fresh and exciting. LEYE could be credited for looking to embrace new cuisines in a bid to sustain the space’s dynamism, but the “modern dim sum” menu—ultimately—was subject to scathing criticism.

In April of 2017, Gillanders would announce his looming departure from Intro, yet he would not be saying goodbye to Chicago as originally intended. The chef and wife Seon Kyung Yuk were won over by the Windy City and, thus, altered their original plan of opening S.K.Y. in Los Angeles. At the time, Gillanders admitted his stay in Chicago “was supposed to be a brief one” but earning the trust of Rich Melman proved decisive. The chef counts the LEYE founder as one of his two mentors (alongside Jeon-Georges Vongerichten) and revealed that he “received Melman’s full blessing” in leaving Intro to go out on his own. (The former L2O space would transform into a virtual restaurant titled Lucky Dumpling in June before making way for a private event space that same July.)

S.K.Y., as described at the time of its chef’s departure from Intro, would focus on “elevated and globally-influenced fare” comprising “influences from Mexico, Italy, and Korea.” Gillanders would not term his cuisine “modern American” (because “that doesn’t mean anything”) and made clear his hatred for “the ‘f-word’” (or fusion). Rather, the restaurant’s menu would be in the same vein as “his first menu at Intro” with a level of technique that would “impress the Chicago restaurant industry” while also being “accessible so his parents can enjoy a meal.” Wine, nonetheless, would “star” when it comes to the beverage program—with the chef feeling that his chosen neighborhood already benefits from “enough cocktails and beer” served at other establishments.

The neighborhood in question, of course, would be Pilsen, with Gillanders choosing a 2,800-square-foot former medical clinic along 18th Street as home to his concept. S.K.Y. would be right across the street from Thalia Hall (refurbished in 2013) and its accompanying Dusek’s Tavern (opened the same year). (Dusek’s awarding of a Michelin star will always strike you as one of Bibendum’s more puzzling decisions, but one that you chalk up to the tire company’s desire to drive traffic to the wider surrounding community.) S.K.Y. would also be located just a few blocks west of HaiSous, the Vietnamese restaurant from Thai and Danielle Dang (opened in June of 2017).

In your mind, HaiSous—fueled by sympathy for Embeya’s untimely demise and the mistreatment of the Dangs at the hands of their business partners—heralded Pilsen’s development into a citywide destination for cuisine. You do not say that to in any way disparage the neighborhood’s longstanding Mexican heritage but, instead, merely to acknowledge that a novel Vietnamese concept from a chef with a proven track record formed an effective lure that brought outsiders onto the block and spurred a broader appreciation of the street’s bars, bakeries, tattoo parlors, art galleries, record stores, and vintage clothing shops. Of course, it cannot be taken for granted that any given community actually desires this sort of ingress, and the Dangs were savvy enough to hire locally (“30 of their 32 employees” at opening living in Pilsen) and consciously sooth “long-time locals” who feel “they’re being squeezed out of their homes unfairly.”

In October of 2017 (approximately one month before S.K.Y.’s opening), Gillanders would get a taste of this anti-gentrification agitation as his general manager was accosted by protestors. They questioned the restaurant’s “right to be in Pilsen” with some shouting “profanities” and claiming “literally, our lives are in danger because you are here.” Though the medical clinic that previously occupied the lot “had been vacant for three years,” the protesters claimed “S.K.Y. will attract white outsiders and raise rents and eventually displace current residents” while also dismissing “Gillanders’s Filipino heritage.”

You agree that concerns over displacement, particularly as it relates to older residents within gentrifying communities, are valid. However, the activists—at face value—sound bigoted and borderline racist. They myopically discount Pilsen’s centuries of shifting demographics (from working class Irish and German to Czech and, finally, Mexican) in order to make some special claim over a barren property. They cynically look to shut the door on an independent business owner, himself the “son of an immigrant,” in a bid to fortify their xenophobic, separatist conception of big city life. And, though the protestors accomplished nothing (other than denigrating the reputation of the very “community” they purport to represent), it is unsurprising that they reared their head some five years later as part of the digital lynch mob targeting S.K.Y.’s sommelier.

Gillanders pressed onward and, in November of 2017, fulfilled his dream. S.K.Y. opened with a menu featuring dishes like “Cornbread Madeleines,” “Black Truffle Croquettes,” “Local Burrata Cheese,” “Maine Lobster Dumplings,” “Organic Fried Chicken,” “Caramelized Diver Scallops,” “Foie Gras Bibimbap,” and “Prime Beef Short Rib”—many of which persist until this very day. The restaurant also offered a $49 “Autumn Tasting Menu” with accompanying $38 wine pairing; however, it maintained a BYOB policy for several months while still waiting on its liquor license (and, to its credit, has continued to abide by a rather generous approach to corkage).

The reaction from the larger Chicago gastronomic community (if not the Pilsen locals themselves) was overwhelmingly positive from the start. Despite being open for little more than a month, S.K.Y. ranked as one of Fooditor’s ten best newcomers of 2017. In January, the Chicago Reader praised the restaurant for “frequently” pushing “the right buttons” with its “vaguely pan-Asian” fare. In March, Time Out awarded S.K.Y. five stars for “craveable, Asian-inflected dishes” in a “handsome” space “that pulsates with warmth and generosity.” That same month, Chicago named Gillanders’s spot its “Best New Restaurant” of 2018 (beating out Bellemore and HaiSous). The Chicago Tribune, too, when awarding S.K.Y. three stars, would term it a “strong contender for the year’s best restaurant.” And Michael Nagrant, as well, would heap praise on the place for, among other things, offering prices that remind him “more of the 1990s than 2018.” Even Michelin’s chief inspector would admit, in September, that S.K.Y. ranked as a restaurant that was “considered for stars but didn’t quite make it.”

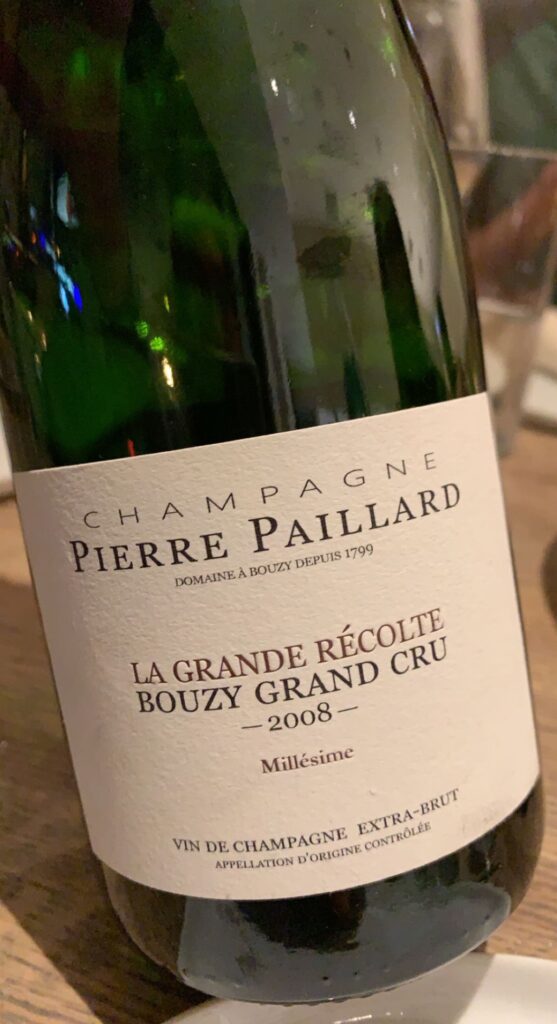

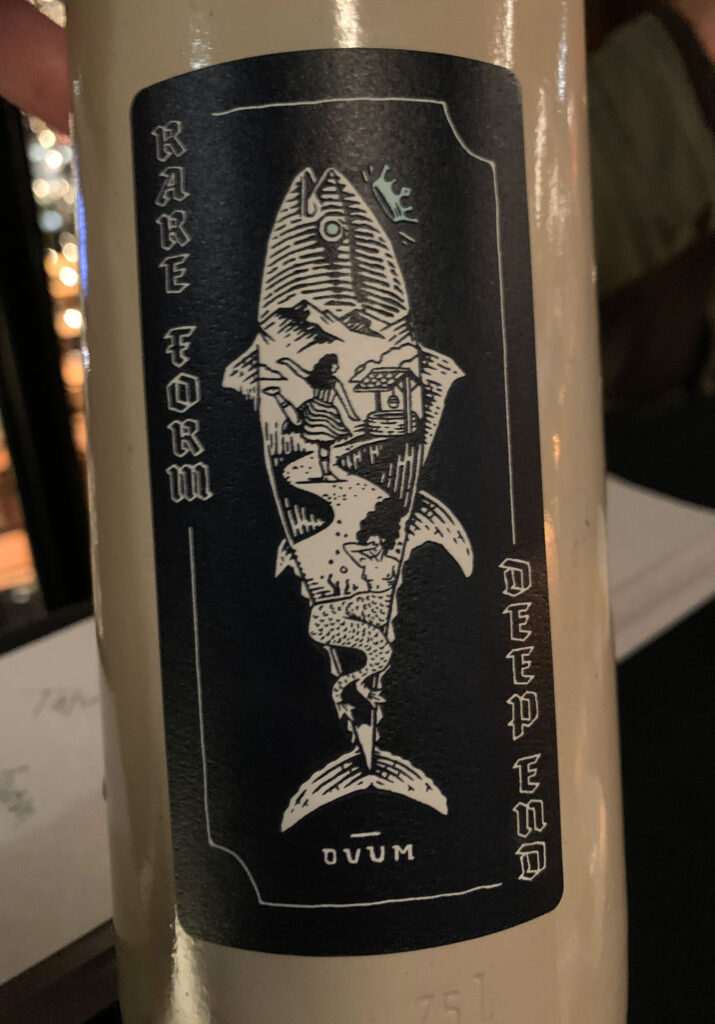

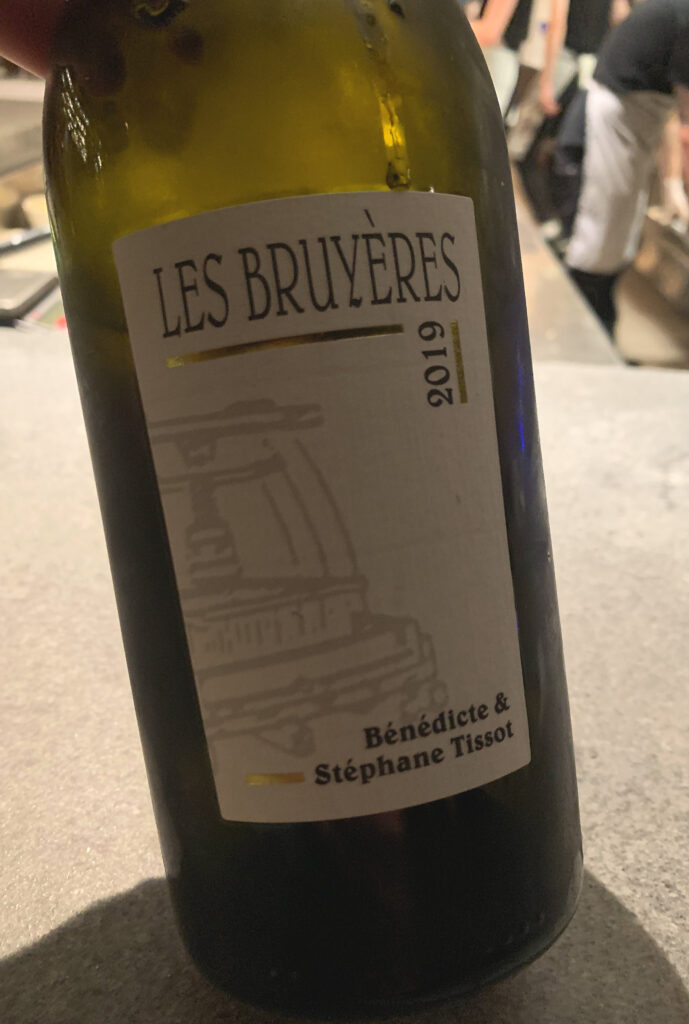

Personally, though you have only visited S.K.Y. a handful of times over the years, you think the restaurant has remained a steadfast paragon of quality and value. It always startled you just how generously portioned and technically refined Gillanders’s dishes were for the price. The space itself, while consciously sparse, felt comfortable and was enlivened by the staff (unerring in their sincere warmth) and throngs of other customers alike. Even the wine program—the kind of detail you would not fault, given the degree of value seen elsewhere, for being executed in a modest manner—impressed from the start. Gillanders, as it happens, was serious about making fermented grape juice the “star,” pouring no less than 32 selections by the glass (a staggering amount) and stocking another three dozen bottles from high-QPR producers (like Chartogne-Taillet, Christophe Mignon, Marie-Courtin, Pierre Paillard, Suenen, Guiberteau, Matthiasson, Radikon, Tissot, Paolo Scavino, Heitz Cellars, and Whitcraft). This all amounts—along with a stellar brunch menu—to a restaurant imbued with that most transfixing of qualities: depth.

Though Gillanders and his general manager “anticipated the worstcase [sic] scenario—no business, no walk-ins,” S.K.Y. had achieved the “best-case scenario” of widespread adulation (and, at least as far as Pilsen’s activist set was concerned, some kind of ceasefire). The restaurant formed “the first time in Chef’s life where he’s not handcuffed to a structure that requires levels of approval for every dish,” and, thus, “the gloves are off for him.” Gillanders, in March of 2018, would laugh off “the ideas of opening another place or going for a Michelin star.” Rather, he wanted only to get his hands on “the new season’s produce” and “to have a successful restaurant that we’re proud to go to, where we’re able to do exactly what we want and have people appreciate that.”

By January of 2020, Gillanders could look back at S.K.Y.’s menu and admit that, despite his intention to serve “more of a global menu,” the customers “tell you what your signature dishes are, they pick those—you don’t get to pick them.” In this case, “they picked the Asian dishes” (with “Chinese- and Korean-influenced dishes like lobster dumplings and bibimbop” becoming hallmarks of the restaurant). The chef was savvy enough to give the people what they want via “new Asian dishes” but also felt “sold short.” He contended: “if that’s what you guys want, that’s what we’ll give you. But moving forward, I don’t want to be known as the ‘Asian Food Guy.’ There’s nothing wrong with that, in my experience, but we can do more.”

“More,” in this case, would signify Gillanders’s second Chicago restaurant, named “Apolonia” after his Filipino grandmother (the very same one who first taught him to cook). The concept would allow the chef to focus on the “European-Mediterranean cuisine” that had been excised as S.K.Y.’s global style yielded to more Asian dishes over time. The restaurant would not be in Pilsen but occupy 5,200 square feet (nearly twice that of his first spot) on the ground floor of a Hilton just one block west from McCormick Place and Wintrust Arena in the South Loop. It would distinguish itself from the city’s other examples of the genre (like Galit and Aba) by spurning hummus and pita to focus more on “the European side of the Mediterranean,” the “Spanish, Italian, France” part that Gillanders is “completely in love with.”

The chef, in his own words, was ready to “double down on Chicago” and reward the city for its support. He’d be taking aim at a neighborhood that had never really formed a dining destination (save for the ignominious Acadia) but, instead, benefitted more opportunistically from the tastes of the transient convention crowd. However, by 2019, the South Loop was undergoing an “apartment boom” (following on the back of a first wave of gentrification in the 2000s) that would yield an even greater permanent population of diners to draw on (without, at least when it comes to the commercialized stretch Apolonia sits on, the same controversies surrounding displacement). Even Erick Williams—of Virtue fame—would eventually open his take-out focused Mustard Seed Kitchen just a block west of Gillanders’s new spot.

Nonetheless, all of that would prove a little way off, as Apolonia’s original estimated fall 2020 opening saw itself delayed by the pandemic (that, itself, decimated any convention business the chef might have hoped to benefit from). In April of 2021 (some 15 months after the restaurant’s original announcement), Gillanders was frank in stating that they “wouldn’t have been able to open” without grants from the American Rescue Plan. But open he did—that very month—with confidence that locals would form the concept’s “bread and butter” while the return of convention business (whenever that day may come) would be more like the “icing on the cake.”

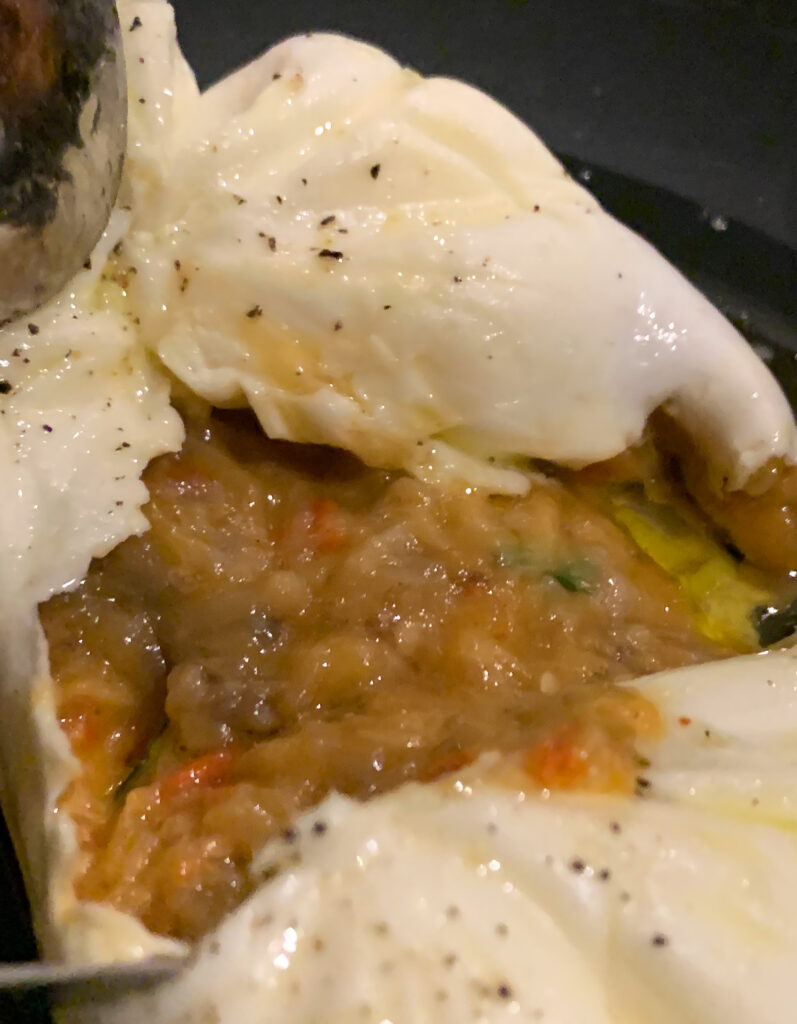

The restaurant itself, now realized, would boast a “monochromatic main dining room” with bright white walls and plenty of natural lighting that feels very much the inverse of S.K.Y.’s interior. However, the two venues would share the same sleek, sparse furnishings—understandably so since Seon Kyung Yuk (the latter restaurant’s namesake and Gillanders’s wife) led the design of both concepts. This sense of visual divergence (and subtle convergence) smartly fits the chef’s larger aesthetic goals: “we would love for a guest to come to Apolonia one night, and then go to S.K.Y. two days later [and] have no idea that they’re affiliated at all.” At the level of cuisine, this contrast would be derived from “many dishes cooked on a grill or wood-burning oven.” Desserts, from executive pastry chef (and long-time collaborator) Tatum Sinclair, would make use of ingredients like Turkish coffee, burrata, and Sicilian “emerald” pistachio. And, on the beverage side, the restaurant would offer “a custom-blended…vermouth” alongside “takes on classic old-world cocktails” and “wines from the Mediterranean coast” by sommelier Jelena Prodan.

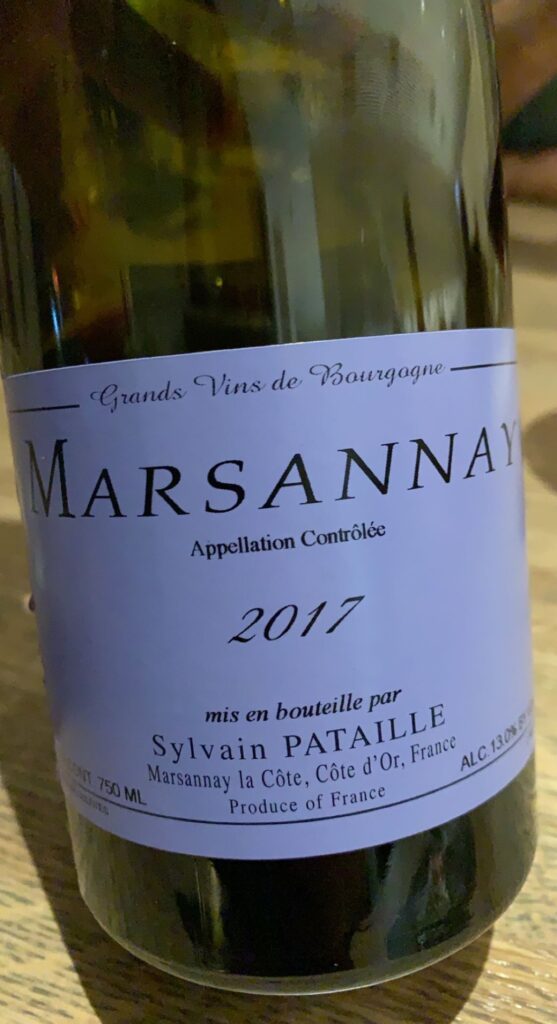

Personally, you visited Apolonia on opening night—as well as a couple of times in the years that followed—and found it to be a worthy successor to S.K.Y. That staggering sense of value—vis-à-vis the portion sizing—remains. Dishes like the “Toothpick Lamb,” both in level of engagement and deliciousness, were utterly genius. Sinclair’s “Black Truffle Puff Bread,” by your measure, is what Alla Vita’s “Wood Fired Table Bread” dreams of being. And Gillanders’s approach to pasta—preserving the traditional essence of the form while thoughtfully elaborating upon it—stands as an example that many of Chicago’s neo-Italian restaurants would do well to follow. Prodan’s wine program at Apolonia would follow in S.K.Y.’s footsteps with more than thirty by-the-glass selections (that’s more than many of the city’s dedicated “wine bars.”) She would add to these options with well-priced bottles from producers like Clos Cibonne, Marcel Deiss, Pierre Gerbais, Pierre Morey, Raúl Perez, Sylvain Pataille, Vietti, and Vocoret.

In June of 2021 (a little over two months after the restaurant’s opening), Apolonia would receive a lukewarm—and rather myopic—review from the Chicago Tribune that saw it earn two stars (relative to S.K.Y.’s three). Any other formal reviews are hard to find. Rather, the restaurant became known for its “viral Instagram dish,” the “Black Truffle Puff Bread.” Sinclair would admit to Chicago that she made “72 different versions” of the recipe before settling on the final iteration. And the magazine, while not ultimately reviewing Apolonia, thought enough of the concept to host one of its (ethically murky) “Secret Suppers” there in 2022. Ultimately, Gillanders’s new spot would receive its most notable praise from Michelin, who awarded it a Bib Gourmand (“good quality, good value cooking”) in March of 2022 citing a “cool and chic” space with “straightforward, exemplary” cooking “poised for sharing” alongside “delightful treats” for dessert.

In the period between Apolonia’s announcement and its eventual opening, Gillanders would involve himself in yet one more project. Drawing, perhaps, on his extensive experience with Vongerichten’s own hotel restaurants across New York City and around the world, the chef would replace Boka Restaurant Group as the operator of the Viceroy Hotel’s two Gold Coast concepts: Somerset and Devereaux.

Going in, Gillanders made it clear that he did not want to “canibalize [sic]” any of his work from S.K.Y. or Apolonia but, rather, execute a “simple and seasonal” approach that does not “manipulate ingredients.” Sinclair would tag along as a consultant and “package deal” with the chef. The duo would bring some interesting ideas to the table (especially given the character of the surrounding neighborhood) with items like “Spicy Crab on Crispy Rice,” a “Crunchy Lobster Spring Roll,” “Housemade Breads,” “Broccolini Pesto Tagliatelle,” “Beet Agnolotti,” “Chicken Schnitzel,” “Beef Wellington,” a “Daily Selection of Ice Creams and Sorbets,” and a “Cheesecake Brûlée.”

Personally, despite your persistent criticism of BRG (and of Lee Wolen in particular) for their stale, cynical concepts, you were a longstanding fan of their Somerset brunch (even if it meant having to witness the Boka chef strut around, rather unprofessionally, in his running shorts). Gillanders’s take on the concept, the one time you sampled it, left you wanting. However, that occasion was rather close to the time of transition, and you will admit that later menus seem much more interesting and faithful to the standard set at his other restaurants.

At the time of Apolonia’s announcement in January of 2020, Gillanders would note that he “doesn’t aspire to morph into a large restaurant group.” The chef “may open more spots, but he wants to concentrate on a few and make them exceptional, carrying the same fun atmosphere throughout.” In other words, “we just want to be a couple people who own a couple of restaurants and work in them.” Nonetheless, in a little over a year, Gillanders would go from one solitary spot in Pilsen to a trio of concepts scattered around the city. And 2022, seemingly out of nowhere, would deliver him with the most exciting opportunity yet.

First, however, it is worth taking a little detour.

Time Out, the publication that awarded S.K.Y. five stars in 2018, diversified its business in 2014 by trading on its expertise to curate the first Time Out Market in Lisbon. That would be followed, in 2019, with locations in Miami, New York, Boston, Montréal, and Chicago (in that order). At face value, a publication embarking on commercial relationships with a select stratum of vendors within a dining scene that it covers seems like a clear conflict of interest. The organization, no doubt, would assert its “editorial independence” in response to such a claim. But, frankly, mass media must be held to the highest scrutiny, and honest criticism—axiomatically—must not be connected to any financial incentive (even, in a perfect world, advertisers). You do not think contemporary journalists have earned the public’s trust, and, free of total transparency in their process (an absolute impossibility as it pertains to such subjective writing), it must be assumed that they will always naturally privilege those who butter their bread.

That being said, nobody would confuse Time Out for a serious source of food criticism. It, like all legacy media, merely serves as a promotional apparatus for public relations firms and the editors’ own pet ideologies. Omission, as always, forms the most insidious weapon of those who wish to shape reality, yet how nice it would also be if readers could ever really get a sense—internally—of why this place (and not that place) merits a cover story. This process, from the outside, seems arbitrary at best. At worst, it churns out consumptive propaganda attuned to unconscious (or all-too-conscious) biases.

So why not simply treat Time Out as something more like a marketing brochure masquerading as a magazine? Why should the publication even worry about impartiality when it can sate (and profit from) the very same desires it spurs via its coverage? At least Time Out, through its markets, is brave enough to take the mask off and reveal that food writing was never about consumer advocacy but, rather, putting one’s finger on the scale in line with personal predilection. The tautological “authority” this breed of journalist concocts (by mere virtue of being published under a recognizable banner) simply takes advantage of humans’ desire for heuristics and channels it toward personal enrichment.

When it comes to the Time Out Markets, the publication has finally put some skin in the game and resolved to stand alongside the vendors they praise in print. In their own words “the Chicago outpost follows a simple rule when it comes to curation: If it’s good, it goes in the magazine; if it’s great, it goes in the market.” This sort of structuring—in which the publication’s vendor-partners implicitly embody the editors’ highest comestible recommendations—does feel oddly transparent.

For Time Out is no longer only profiting on content creation (and its associated advertising lucre), but rather answers directly to the consumers who place their trust in the staff’s curation. Bad criticism is no longer obscured by the essential degree of separation between the journalist and the business about which they write. The diner, upon enduring an awful meal, can no longer be assuaged by the claim that the restaurant was just having a ”bad night.” They will no longer just forget who—through sloppy evaluative technique or total hackery—led them astray. They will no longer just move on to the next splashy feature and make the same mistake all over again. Time Out must, via the markets, live and die by its editorial “taste” and accept that any flawed selection or hiccup in operation poisons its own brand.

This, to you, feels like ownership. It feels like honesty. It strips away those last vestiges of “journalistic integrity” and acknowledges that any claim to ethical behavior was always but a farce. Food writers only feature people they like, people who fit prefabricated demographic categories, and those who toe the line of their boss’s worldview. Criticism comes second to curation; in fact, criticism forms the rubber stamp with which to reward one’s friends and the cudgel with which to punish one’s enemies. The human mind can contort itself to justify any opinion, and an article of only several hundred words—though aiming to tell a restaurant’s story—will always leave more unsaid than said.

So why bother with the song and dance? Why even try to untangle the many layers of subjectivity that make “objective” food criticism an oxymoron? Why not simply say: “we liked it so much we went into business together”? Now that is praise, and it ensures fewer rubes are left thinking that any given journalist actually advocates for the public’s interest.

When Time Out Market says that it offers “the city’s most delicious dishes, cooked by some of the most decorated chefs in the Midwest,” consumers know they are listening to an infomercial. When the venue touts “a hand-selected array of everything you could want to eat, drink and see in Chicago, all under one roof,” no gastrotourist really thinks they are going to substitute a trip to Alinea, Oriole, or Smyth with something served out of a stall. Placing financial interest front and center while abandoning any pretense of ethical purity ironically reads as trustworthy. You do not mind being sold to, but you do rue those who—while posturing as independent voices—subtly manipulate your taste in line with their own, unstated vision of social engineering. There’s something shameless about what Time Out is doing, yet it remains a thousand times more palatable than what its peers—draping themselves in the banner of the Fourth Estate—perpetuate.

Time Out Market Chicago’s opening roster, in November of 2019, comprised stalls from Band of Bohemia (which closed in 2020 under a dark cloud), Brian Fisher (whose restaurant Entente you still miss), John Manion (of El Che Steakhouse), Bill Kim (who closed his longstanding Randolph Row concepts in 2018), Thai Dang (whose HaiSous forms one of S.K.Y.’s Pilsen neighbors), The Purple Pig (from hotheaded 2014 James Beard “Rising Star Chef” Jimmy Bannos Jr.), Kevin Hickey (representing both The Duck Inn and Decent Beef), Abe Conlon (of the subsequently embattled Fat Rice), Split-Rail, Mini Mott, The Art of Pizza, Pretty Cool Ice Cream, Lost Larson, FARE (a “clean food” concept), Arami, Dos Urban Cantina, and Sugar Cube (from the ignominious Jason Chan). Tortello and Erick Williams (of Virtue) would be involved in programming for the market’s second-floor demonstration kitchen while Paul McGee and Shelby Allison (of now-imploded Lost Lake) would run a hidden speakeasy there too.

The goal of bringing so much talent together, in the CEO’s own words was “making fine dining casual, and casual extraordinary.” He even spoke of “democratizing fine dining” (a favorite phrase of yours). This rogues’ gallery of “the city’s best culinary talents” (alternatively referred to by their own names or by those of their businesses) came about when “the Time Out Chicago editorial team trawled the city in search of the best chefs and restaurants, and then invited the very best to join Time Out Market’s all-star lineup.” Though you will admit that the publication put together a rather impressive lineup of collaborators, you would only term them notable (and not the “best” in any of their respective genres). A case could, perhaps, be made for Thai Dang, Abe Conlon, Lost Larson, and Paul McGee representing peak expressions of their particular crafts, yet Time Out is clearly taking some liberties (while, to its credit, offering guests the convenience of many great—though not the “best”—names under one roof). Fair enough, you say.

Unfortunately, Time Out Market Chicago’s opening momentum would be sapped—like so many hospitality projects—by the pandemic. The venue would close in March of 2020 (ahead of the state’s formal suspension of dine-in service) and reopen later that year in August. Only Arami, Bill Kim, Brian Fisher, Dos Urban Cantina, Kevin Hickey (but not his Decent Beef concept), Lost Larson, Mini Mott, and Pretty Cool Ice Cream remained as Time Out, to its credit, gave other vendors “the option to end their one-year agreement early.” The market’s promise of “international opportunities” and “additional exposure” for its curated chefs had quickly devolved into an outright battle for the venture’s survival in an era without the “West Loop and Fulton Market workers” that would typically crowd its corridors. And, when indoor dining was once more forbidden in October of 2020, you wondered if the dilapidated market had been dealt its death blow.

In late January of 2021, limited dine-in service would return; however, Time Out Market Chicago would wait until June of that year (concurrent with the lifting of all restrictions) to reopen. At that point, only Arami, Bill Kim, Brian Fisher, Dos Urban Cantina, and Mini Mott would remain from the original lineup. However, they would now be joined by Candlelite (tavern-style pizza), Cleo’s Southern Cuisine, Pisolino, Shawn Michelle’s Ice Cream, and Soul & Smoke. Three of these stalls (Cleo’s, Shawn Michelle’s, and Soul & Smoke) would be black-owned in a seeming response to criticism over the “glaring omission” of such businesses at the time of the venture’s original opening. Between the time of that announcement and the market’s return to operation, it would also add Polombia (a Colombian-Polish “mashup”) and Bittersweet Pastry to the assortment of stalls.

In October of 2021, Bar Goa—from the owners of West Loop’s ROOH—would enter the mix as Time Out “was determined to add diversity to its vendor lineup.” That month would also mark the first time, since before the pandemic, that the market would be open for seven days a week. In Janaury of 2022, Lil Amaru (an offshoot of Rodolfo Cuadros’s Amaru) joined the lineup. Then, in February of 2022, Luella’s Southern Kitchen (from James Beard Award “Best Chef: Great Lakes” semifinalist Darnell Reed) would open a pop-up stall during Mardi Gras that would subsequently transform into a permanent fixture. Early March would see Evette’s (a third location of the Lebanese-Mexican mashup) enter the fray while Avli (the fifth location of the Greek chain) and Big Kids (the second location from Ryan Pfeiffer and Mason Hereford), too, joined later in the month. Somewhere along the way, Gemma Foods, JoJo’s ShakeBAR, and Lono Poke would enter the mix (while Brian Fisher, Candlelite, Dos Urban Cantina, Mini Mott, Cleo’s Southern Cuisine, Pisolino, and Shawn Michelle’s Ice Cream would close their stalls).

Today, Time Out Market Chicago boasts seventeen unique stalls that, after a couple difficult years, measures up to the number of options the publication pulled together at the time of the venture’s debut. Once more, you think a case can possibly be made that stalls like Bar Goa, Soul & Smoke, Big Kids, Luella’s Southern Kitchen, Evette’s, and Polombia represent “the best of the city” within their particular niches. However, you do not think such a case is all that convincing, and Time Out has now opted to describe the concept as an “expansive, curated experience” featuring “the highest-rated local restaurants and Chicago’s most-revered chefs.”

This verbiage, in your opinion, continues to stretch the truth. For it seems clear that—post-pandemic—the market was forced to scramble to fill its stalls with anyone who carried a bit of name recognition, anyone who looked to expand on the name recognition of their brand, or anyone who could be relied upon to successfully, consistently operate within the space. When you add a conscious concern for “adding diversity” into the equation, you end up with a selection that cares less about featuring “the best of the city” and more for catering to the lowest common denominator via a superficial “variety” that implicitly discounts Chicago’s strength in some genres and weakness in others. Rather than offering the greatest depth in the city’s essential gustatory forms or celebrating different manifestations of the most beloved techniques, Time Out Market has increasingly used hyphenated “mashup” (just another name for “fusion”) cuisines to seem appealing. It has increasingly leaned on chains like Avli and JoJo’s that have already reached the point of market saturation. You have nothing against these concepts personally. No, you just think they reveal that Time Out is working backward to make the market a “success” (in a focus-grouped, market research kind of way) instead of truly asserting some vision of (and successfully collaborating with) “the best of the city.”

It is with this context—of a faltering Time Out Market looking to live up to its publication’s own hyperbolic expectations—that you now return to Gillanders’s story. The prodigious chef, counting S.K.Y., Apolonia, and Somerset all under his belt, would—on relatively short notice—embrace his greatest challenge yet. It would mean turning his back, somewhat, on the accessible global fare that had endeared him to Windy City diners. It would mean engaging with his fine dining chops and his adoration of wine at the highest level, delivering the kind of menu that would put all his experience with Jean-Georges (always invoked as a mark of where he’s been rather than where he’s going) to its harshest test. Gillanders had made his mark at Intro by subverting the example set by the restaurant’s opening trio of chefs to offer an à la carte selection. Now, nearly seven years later, he would finally commit to the tasting menu form and to a level of indulgence he had thus far restrained himself from pursuing.

Time Out, who clearly did not find April’s activist tantrum disqualifying, announced in early September of 2022 that Gillanders “will lead Time Out Market Chicago’s first standalone restaurant.” He would be “moving behind the confines of a brick-and-mortar restaurant” to open Valhalla, “an original fine dining concept” named for “the great hall of eternity in Norse mythology,” on the market’s second floor. There would, indeed, be à la carte options, yet the focus would undoubtedly be “an intimate chef’s counter tasting experience guiding guests through a 11-course menu” that the chef says “is equal parts decadent, globe-trotting and personal.” Gillanders would go so far as to say that “this is going to be the best food I can make right now” with “a story for every dish” that, in effect, “summarizes the entire evolution” of his career.

(Gillanders, it is worth saying, “wasn’t looking to open another restaurant” when he was approached by Time Out. However, just the same, he “wanted to branch into fine dining for several years.”)

Concurrent with the publication’s announcement, Gillanders had “divested from his other two restaurants as well as a position as chef at Somerset” to focus uninterruptedly on “creating an upscale experience that melds into the Market’s energetic atmosphere.” While admittedly “unconventional,” this nesting of a rarefied expression of craft within a more broadly popular setting actually represents, according to the chef, “a tradition…on the cutting edge of global fine dining.” He cites the fact that “Geranium, the best restaurant in the world, isn’t just in Copenhagen—it’s in the soccer stadium in Copenhagen.” Further, “Brooklyn Fare is in a food market, and they have three Michelin stars.” The reference to Norse mythology, thus, winks at “the restaurant’s location overlooking the main floor of the Market” and the notion of “transcending the [downstairs] experience as a whole.”

Valhalla would accommodate “66 diners, including the 14-seat chef’s counter” in a “partitioned space” on the eastern end of the venue’s second floor. There’d be a proper host at a proper stand waiting to greet diners while Gillanders, likewise, “will be based at the restaurant full-time and plans to interact with guests personally throughout their meals.” (Tatum Sinclair and Jelena Prodan would be offering their expertise firsthand as well).

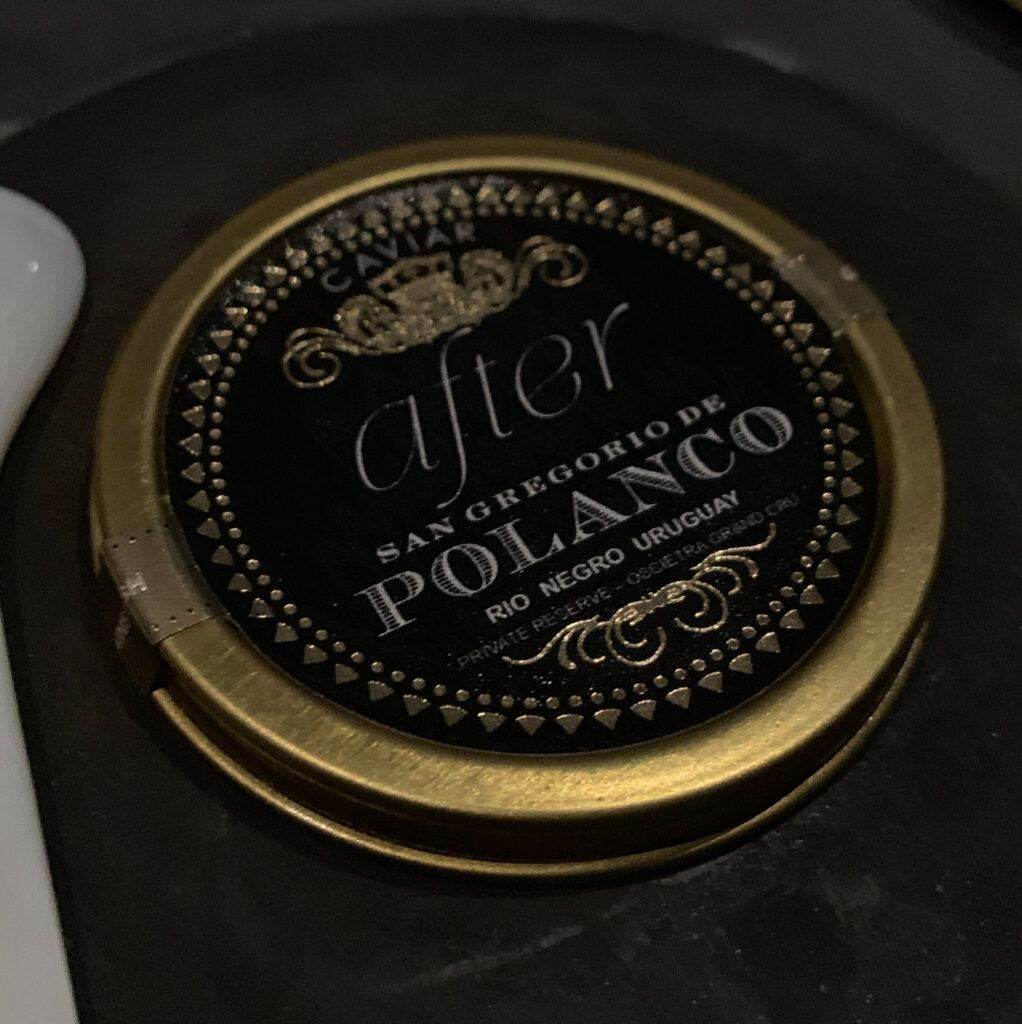

The menu, going into more detail, would be inspired by the chef’s “time working for Vongerichten as well as his travels around the world,” yielding a selection of dishes labelled “approachable and rad, but not overly stuffy or fancy.” One preparation, a “pumped-up homage” to “crab arroz caldo” (a “traditional Filipino porridge”) would represent Gillanders’s embrace of his mother and grandmother’s heritage (“a venture he once regarded as intimidating”). Patrons could also expect to see ingredients like caviar, sea urchin, quail egg, Japanese scallops, and dry-aged lamb utilized, with the chef hoping guests will “lean into the novelty” of eating such totemic luxury ingredients “in an unorthodox space.”

Ultimately, the most convincing testimonial regarding the new concept would be one of attitude: “we will never say that we can’t do this because we’re in a food hall. On the contrary—we’re going to say we should do this because we’re in a food hall. I think there’s going to be the expectation for us to make things a little lesser, and that’s where we’re going to double down.”

Valhalla would open on September 21st, less than two weeks after the restaurant’s announcement, and that is right about where your journey will begin.

You have visited Valhalla a total of four times, comprising visits in late September, October, November, and December. As usual, you will condense the sum of your experiences into one cohesive narrative.

With that said, let us begin.

Trekking to the Time Out Market, you have found, means returning to that familiar corner of Fulton & Sangamon. Joe Flamm’s Rose Mary, of course, is located right there—as it has been since April of 2021. Vital Proteins, with its atrocious street level billboards (that not even Jennifer Aniston’s visage can save), has occupied its own corner since the beginning of 2019. And Time Out, you may recall, made its entrance onto the block at the very end of the same year.

The publication’s market, you might say, totally dominates the intersection. For the Vital Proteins building, despite its offensive impression curbside, cuts a subdued figure. Rose Mary, while contending with lines of would-be guests at opening, does well to manage their inflow and—during the warmer months—maintains only a modest patio. The southeast corner, meanwhile, sits undeveloped (for now). An 11-story office building at 919 West Fulton is on the way with a 25,000-square-foot Dom’s Kitchen & Market signed on as its anchor tenant (complete with a rumored “large café” from Hogsalt’s Brendan Sodikoff). Even Gibsons Restaurant Group has gotten in on the act, agreeing to lease an additional 15,000 square feet within the property.

But, for now, Time Out Market bustles with a singular energy. The building—along with its ample patio—stretches across half the block. Its neighbor to the east, the former Nealey Foods meat wholesaler, lies dormant—waiting to be transformed into a nine-story “boutique office building” for the right bidder. LÝRA forms something more of a neighbor, but DineAmic’s sprawling Greek spot can hardly be called a destination restaurant. No, by your measure, Time Out Market forms the perfect sink for all the action flowing westward from Duck Duck Goat, Beatrix, The Publican, and Aba. It even, perhaps, draws patrons northward from The Hoxton and Nobu hotels (to say nothing of Randolph Restaurant Row itself).

The importance of a bright, clean place to simply linger cannot be overstated. That “third place,” usually the domain of coffee shops, is sorely lacking in the neighborhood. Good Ambler, Sawada, La Colombe, and—yes—even Starbucks have their charms, but the spaces are perpetually packed with the most stereotypical, territorial kind of loafers. Soho House, though offering a perfect solution for the rootless, wannabe “creative” class, holds little appeal for those who do not share in the delusion. And, while McDonald’s has formed a longstanding “third place” in its own right, you do not know many people who wish to hang out at Hamburger University.

Yes, the genius of Time Out Market—before you even get into the gustatory offerings—is wholly structural: it is a neutral space in which one can feel anonymous. It is a place, from 8 AM – 10 PM, you can enjoy warmth, WiFi, water fountains, and washrooms. It is an establishment where you can meet up, spend nothing, and plan your next move. Time Out, though not a charity, is smart enough to know how consequential this foot-in-the-door effect is. Its market really does double as a neighborhood gathering hall, especially for large groups. The positive brand impression that entails—long before anyone is tempted to visit one of the stalls—is incredibly valuable.

However, in practice, 916 W Fulton is almost unassuming. The reddish, brownish brick—offset by black doors and window frames—gels perfectly with the area’s other new developments. “Time Out Market” is emblazoned over the building’s prominent awning, as well as on the signposts that dangle beneath it, but this is executed in relatively small type. The concept’s greatest testimonials, instead, are the throngs of customers that line the patio and congregate on the other side of the glass. You could be forgiven for thinking the place was a bona fide public space—perhaps until you encounter that bit of marketing copy plastered onto the central windows: “the best of the city under one roof.”

Stepping inside, you first encounter the banks of bars—clad with stone countertops and blue tiled bases—that service the main floor. Pressing onward, you slide through the flow of bodies that defines the market’s perimeter (that is to say, the avenue through which patrons access each of the stalls) and approach its center. Seven pairs of sturdy communal tables, matched (save for the two capstone sections) with counter-height chairs, define the space. The floor is rendered simply in concrete while, above, a sloping glass roof ensures ample natural light. After dark, that yields to an array of smaller lamps and hanging bulbs affixed to the ceiling. Their effect is soft, warm, and welcoming.

Depending on the time of your reservation (Valhalla is open from 5 PM – 10 PM), the market’s main tables may range from 50-80% occupancy. While that matters little for those set to go upstairs, this degree of patronage works to define the ambiance. The ground floor bustles with energy—but not to the extent that you must shove your way past people to make it toward the stairs. Rather, it is quite easy for you to imbibe a pre-meal libation or even indulge in a snack (knowing how tasting menus can sometimes be) before visiting Valhalla. It is easy to find a little space at one of the tables—that are admirably and proactively bussed by the Time Out staff—to stop and soak everything in for a moment. That is a credit to the market’s design and its aspiration (in terms of size). However, with each new West Loop high-rise, the odds of enjoying this kind of unencumbered experience—at least during peak hours—will surely slim.

What matters most is that the first floor is orderly and navigable. There certainly are some chokepoints—primarily near the corner areas in which the perimeter path intersects the doorways or stairs—but any congestion can (as always) be blamed on self-centered and oblivious people. When finding a spot for yourself at the communal tables, the other visitors are polite enough. The market’s seating is managed in such a way that nobody breathes down your neck. Protecting one’s personal space, for many, remains particularly salient. Yet you cannot help but feel this kind of compartmentalization detracts from the romance of the market as a sort of community gathering hall.

In its bid for “representative” curation, Time Out has sidestepped the harder task of defining the space—of constructing any kind of collective culture that bonds its denizens. No doubt, the company has constructed an efficient, intuitive commercial space. But does it have character? Does it have soul? Does it advocate any particular vision of what Chicago food culture stands for? The answer, no doubt, is written in the stalls: those that once featured the city’s most totemic foods but have now become a hodgepodge of cuisines. This kind of breadth—rather than depth—will always privilege a lowest common denominator conception of taste. It will only reflect—rather than remedy—the atomized society in which Americans today live. The result is a ”collective” space that feels more like many groups of anonymous strangers consuming side by side. That makes for nothing more than a Disneyfied take on the world’s great markets—a suburban mall food court on steroids—that, by prizing superficial diversity, actively destroys native culture. (But hey, it makes money.)

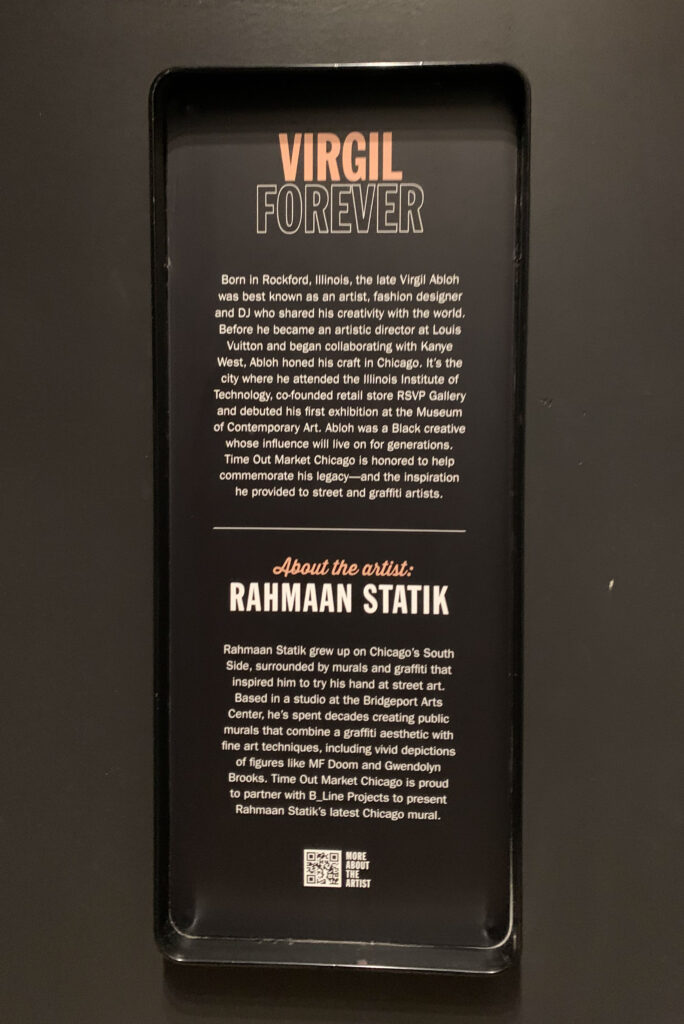

Once you are ready, you make your way to the rear of the market’s main floor and to one of two staircases that bookend the back wall. Climbing the first flight, you find yourself face to face with one of two art installations. The first of these, located on the west side of the building, comprises a mural of the late Virgil Abloh painted by Rahmaan Statik. The work was unveiled in February of 2022 and, despite Time Out having no obvious connection to the Rockford-born, IIT-educated designer (making the gesture seem a bit contrived), the market was smart enough to donate $1 of every “Virgil Forever” (gin-and-tonic-inspired) cocktail that month to the Virgil Abloh™ “POST-MODERN” Scholarship Fund. You suppose there are worse ways to ingratiate yourself to a city, but some firmer—more longstanding—commitment to the man’s legacy might make this manner of trading on his image sit better.

Climbing up the eastern stairwell, you encounter an altogether different installation made of historic Time Out covers arranged into a grid. Nine rows (of six magazines each) span half-decade periods running from 1975-1980 all the way to 2015-2019. Though the publication did not launch in New York until 1995 (nor in Chicago until 2005), this display endeavors to root the market in a broader counterculture heritage with main coverlines like “John Lennon 1940-1980,” “Porn,” “Who Killed JFK?,” and “Drugs” being prominently featured. While this association is, of course, a bit laughable for a family-friend commercial space, the cover designs are striking and engaging in their plentitude.

Passing from the market’s first to second floor, thus, prompts a moment of pause. The Time Out brand, which is subtly integrated into the workings of the assembled stalls, is brought more to the fore. The darker, plainer tones that define the building’s walls and surfaces are—here—invigorated by bursts of color. The themes associated with the art installations are ham-fistedly invoked. They have little to do with good eating or establishing the brand’s credentials as a curator of quality. But they help to demarcate a transition from the swirling, “mass” space below into something more intimate and distinctive.

First, however, you must sidestep the bathrooms that greet you upon scaling the second flight of stairs. That brings you to the slender walkway that defines this upper level. Against the north wall (and opposite the market’s entrance), you find an additional bar planted next to a section of tiered bench seating. The walls of this area are totally rendered in red, making it feel like something of jewel box that—despite its vantage point (and corresponding exposure) above the fray of the first floor—stands apart from the rest of the venue. This zone, taken both from afar and firsthand, underscores that the second level is a calmer, more dignified counterpart to the bustle below. From its tiered seating, you can just about make out Valhalla—though the restaurant is partially obscured (perhaps seasonally) by sets of dangling lights.

Along the western end of this upper level, you find the “Demo Kitchen” that “plays host to cooking workshops, cocktail classes, and intimate dining experiences from the best culinary talent in Chicago.” Time Out mentions “a rotating schedule from up-and-coming culinary stars, as well as acclaimed guest chefs and bartenders” that makes for “an experience you won’t forget.” However, as of now, the market’s only planned events comprise DJ sets (on the rooftop) and children’s “Character Storytimes” (located on the first floor). In practice, the “Demo Kitchen” (which is observable from Valhalla’s seating) plays host to private (corporate) events and, more frequently, acts as overflow seating for those looking to transport their comestibles upstairs.

Working your way to the eastern side of the second floor, you finally reach your destination. Valhalla, as such, centers around an open kitchen bounded by a C-shaped counter that stretches nearly thrice the length of the stalls that lay below. This “pop-up area,” at the time of the market’s opening, was set to house a three-month residency from Funkenhausen; however, the concept would ultimately back out and be replaced by Arami (in its first iteration before moving downstairs). The space was also set to host “events like a harvest festival for families, a holiday market, live art, local artisans, music performances, and DJs,” but you think these plans were scuttled by the pandemic. Nonetheless, this is all to say that Gillanders occupies an area that was designed with a certain impermanence (at least conceptually) in mind. (The fact that a series of three-month residencies might have originally defined the counter’s offerings sounds eerily similar to Intro!)

Valhalla has been touted as a partnership that—certainly with regard to its aspiration—is in it for the long haul. Yet, approaching the restaurant, it hardly feels like you are leaving the wider market in search of a particularly luxe experience. A solid-looking host stand and wall of shrubbery serves to shield your view of the tables that run parallel to the counter and that make up the rear dining room. (This is particularly important given that the east stairway deposits market-goers—many, no doubt, searching for the bathroom—with a direct sightline of Valhalla’s guests.) Otherwise, the counter is rendered in the same grayish stone used for the bartops downstairs. The kitchen is lined with stainless steel surfaces and appliances. And the tables are clad in black tablecloths that ensure a certain symmetry with the darker tones of the building’s beams, railings, walls, and ceiling.

The restaurant’s seating, nonetheless, is a welcome departure from what you find on the first floor. Both the counter-level chairs and those situated at the tables feel far more robust than anything found in the communal part of the market. Importantly, the furniture boasts arms—not quite a necessity when it comes to securing a Michelin star, but a source of comfort that undoubtedly enriches your experience of the meal.

Aesthetically, there is not too much else to note. Valhalla, along the top of its counter, displays the same kind of signage affixed to the stalls below. However, this is balanced by a larger, more stylized phonetic rendition of the name planted on the kitchen’s wall (closest to the entrance). Candles, it should also be mentioned, line the tables and make for a moody, romantic effect when set against the black cloth and wallpaper. (This stands as a small but classy flourish that adds a bit of grandeur to the table settings even if the ambiance is—otherwise—a bit stripped down.)

Apart from the 14 chairs that run down and around the counter, the restaurant offers a series of four-tops located across from the kitchen along with a larger collection of two-tops (you count half a dozen) and a few more four-tops in the dining room that lies at the rear of the space. (This latter area, which runs along the south side of the building, is effectively split with the “Demo Kitchen” and separated by a wall of shelving lined with more greenery. In practice, you barely sense that the adjacent area is even there, yet you wonder if that would hold true when it hosts a private event.) Parties larger than four can be booked for à la carte dining; however, while Tock seemingly offers the tasting menu for up to six guests, selecting a size of five or more yields no availability. Ultimately, you have found Valhalla to be highly responsive and gracious about serving these larger groups when contacted. But why not fix the Tock page to more clearly enable (or totally forbid) this size of seating in line with the kitchen’s preference? (This has since been remedied.)

While Valhalla’s particular environment—when dissected piecemeal—hardly transcends that of the wider Time Out Market, your visceral experience of the space feels successful. Upon approaching the restaurant, the hostess greets you with a warmth and enthusiasm that immediately distinguishes itself from the more anonymous interactions that characterize the multitude of public-facing stalls below. As she leads your party to its seats, the kitchen team—including Gillanders himself—turns to welcome you from the other side of the counter.

This degree of intimate engagement, even if the concept’s trappings aren’t all that distinctive, surpasses many of Chicago’s Michelin-starred venues. The chef is not cloistered away and called upon only for a fleeting table touch. No, you get the feeling that he is hosting and orchestrating every moment of your evening—putting on a performance that, even when compared to the open kitchens at Smyth and Oriole, shines on account of its relatively smaller “stage.” (You think only Rose Mary’s chef’s counter, due to its even greater intimacy, and the city’s various omakases improve on this same effect. Elizabeth, in its time, certainly conjured such a feeling too.)

To that end, you think most patrons would favor booking Valhalla’s tasting menu at “The Chef’s Counter.” Due to the modest amount of seating available by the kitchen, going the à la carte route necessitates being seated in the dining room. However, those looking to enjoy the tasting menu at a table are actually given a bit of a choice. They can choose the “Intimate Setting,” which “allows for a conversation driven meal,” or the “Interactive Experience,” which feeds “off of Time Out Market’s energy” by seating guests “in a lively part of the restaurant” and “allowing for a unique and animated dining experience.”

This, quite frankly, is kind of genius, and it connects to the way that Gillanders has branded Valhalla since its inception. The restaurant’s staging within a relatively open environment that is subject to all the noise and action of the first floor is, by your measure, something that detracts from the experience. For, as romanticized as the idea of a city market may be, Time Out’s creation has no culture or heritage to draw on. It does not offer a scene of humanity that distinctly represents Chicago or that is all that interesting to observe. (Once more, it is more like gawking at a suburban mall’s food court than enriching yourself with any real sense of place.)

The chef, nonetheless, has preempted these concerns and shaped a narrative—invoking other great restaurants situated in “unorthodox” settings—that turns this vice into a virtue. He has painted the lack of a traditional “fine dining” environment (pretty much an essential condition of forging the partnership with Time Out and taking over the space) as expressing a sort of “new luxury” that stands opposed to pretension. It is one thing, of course, to put forth this idea in print. However, segmenting the table seating into the “Intimate Setting” and “Interactive Experience” categories helps patrons feel in control. They do not feel punished if they end up close to the railings with greater exposure to the ground floor’s goings-on. In fact, you think the description makes such tables seem like the more coveted of the bunch (and, in the sense that some of them are located closer to the counter, that may be true). In either case, Gillanders deserves credit for turning a potential weakness into a strength and encouraging his guests to see the positive side of the setting rather than coming in blind and grasping at (as patrons paying for premium meals are apt to do) something to get mad about from the start.

But, now taking your seat, any hang-up regarding the ambiance (or lack thereof) is remedied by the continued engagement of the staff. This feature, though you do not fault the effort to prime your perception of restaurant’s setting, is Valhalla’s real blessing (for Chicago is not short on pretty dining rooms that lack the slightest bit of soul).

Given that the concept revolves around an open kitchen and chef’s counter, it is no surprise that the back of house does their part. Gillanders and Tatum Sinclair typically appear at least once during the course of the evening—should you be seated in the rear dining room—or even more often when you are situated closer by. They display all the warmth, charm, and polish you would expect from executive chefs working such an intimate space. And, likewise, it is rewarding to see them transition from executing intense technical work or orchestrating the rest of the kitchen to appearing tableside in order to apply some enrapturing flourish. (Gillanders confided, during your first meal, that he is not used to being so constantly “exposed” to his guests during service. However, he weathered a bit of criticism you offered on that occasion—regarding a certain dish—gracefully, and you think his enthusiasm for the food—regularly on display via social media—rings true.)

While this manner of leading from the front is a hallmark of any great restaurant, the real test—when it comes to service—must measure whether the same attitude pervades the rest of the staff. (For it is all too easy for those who command the spotlight to shine at a cost to all those who toil away unseen.) Thankfully, you have found Valhalla’s team to be kind, conscientious, and knowledgeable across all your interactions. The other cooks, taking Gillanders and Sinclair’s lead, present dishes with a naturalness and clarity that speaks to their ownership of the work. What’s more, they radiate with the kind of sincere smiles (some confident, others touchingly sheepish) that mark an empowering, accepting work environment.

The front of house, by comparison, has its work cut out for them. For Valhalla—very much in the “pop-up” mold—privileges having more hands in the kitchen than out on the floor. This allows Gillanders and his team to execute more intricate food (especially when it comes to plating and the preparation of items à la minute) but demands more of those tasked with watching over the dining room. This comprises an expeditor, a server, and one or two food runners that handle everything from filling water, placing utensils, delivering dishes, and clearing the table to listing specials, taking your order, answering any clarifying questions, and describing any given course with the same degree of insight that the back of house offers.

These duties all might sound a bit routine, yet the ratio of three or four members of the front of house to thirty or forty guests demands near-ceaseless activity. While the kitchen team is able to chip in when it comes to caring for those seated at the counter, the dining room really relies on but one or two people to keep the evening on track. Valhalla’s front of house, faced with this challenge, operates sharply and efficiently to ensure you are never left in the lurch. Yes, there may be an occasional misstep—a dropped set of utensils or failure to notice a patron’s handedness—but the team expends a great effort while maintaining the right attitude.

Your server, despite so much to stay on top of, does not rush away from the table or preclude forging some kind of connection with their party. They maintain an upbeat mood and genuine curiosity regarding your experience that makes them seem more like an extension of the kitchen—with its ownership over what is being served—than a mere agent of it. They are equipped to tell the story of the menu while richly describing more esoteric ingredients in a way that feels flowing and organic. This, beyond the example Gillanders sets during service, speaks highly to the chef’s ability to train and motivate the rest of the staff. His team is a pleasure to interact with from top to bottom (and that is something you have felt since your very first visit to S.K.Y.).

Jelena Prodan, it should be noted, serves as both the service and wine director at Valhalla. This places her in the thick of everything that occurs around the counter and across the dining room—a valuable resource to draw upon for any of the mechanics of service, as well as an assurance that those ordering pairings or bottles feel they have gotten their money’s worth. This dual role, in the same way that the kitchen delivers and describes its own dishes, allows the restaurant to maximize the utility of those on the floor. But it no way discounts the quality of a beverage program that, despite being nested in a market that profusely sells cocktails across all three of its floors, surpasses those of much larger, comparably “luxe” concepts.

Upon settling in at the table, you take hold of the food menu—its front attractively emblazoned with the handwritten signatures of the staff—and, after browsing the comestibles (more on those later), find your way onto the back. To the right, you find a selection of five “House Cocktails.” These comprise “The Frozen Martini” (“caviar filled olive | vodka | vermouth | shaved caviar”) for $35; the “Triple Rose of Sharon” (“valhalla rosé champagne | raspberry-rose sorbet | rose salt”) for $22; the “Sakura Old Fashioned” (“japanese whiskey [sic] | okinawa kokuto | kumquat perfume”) for $25; the “Honey I’m Hometown” (”honey brandy | xaymaca rum | chamomile”) for $22; and “The Shapeshifter” (“12-year aged scotch | cold pressed carrot juice | caramelized ginger”) also for $22.

When it comes to pricing, these drinks land well north of the $12 “Signature Cocktails” offered at Time Out Market’s various public-facing bars. Yet it is worth noting that S.K.Y.’s own offerings are in the $13-$16 range and that Apolonia’s fall within a more narrow range of $15-$16. (Kumiko, just to bring in an example from a particularly renowned venue, charges as little as $10 and as much as $50 for its drinks. Nonetheless, the average price for one of Julia Momose’s creations, taking into account the entire menu, amounts to $20.20.)

Given that Valhalla’s tasting menu ($185) costs nearly three times more than the one currently offered at S.K.Y. ($68), you think it is acceptable for Gillanders to charge about 50% more for a cocktail at the former concept. Also, relative to the kind of mass market experience provided on the first floor (where patrons, mind you, can drink as much as they please before heading upstairs), you think it is fine for a comparably exclusive tasting menu “pop-up” to defend its brand positioning with pricier offerings. Nonetheless, should the “Honey I’m Hometown” (made with $25.99 Plantation Xaymaca Special Dry Rum) really cost $10 more than the market’s “The Evil Dojo” (made with $32.99 Plantation Stiggins’ Fancy Pineapple Rum)? Yes, the former recipe also makes use of a “honey brandy” (that likely explains some of the price difference), but it is not quite obvious that you are paying for any kind of premium spirits.

You are also not quite paying for the ambiance and cultural experience that defines a place like Kumiko and situates its products within a pinnacle expression of craft. However, in the case of “The Frozen Martini,” there is certainly some delving into the kind of molecular gastronomy cocktailing The Aviary is known for (and that works, along with the use of caviar, to explain the price). Ultimately, you have sampled both the “Sakura Old Fashioned” and “The Shapeshifter,” finding the two drinks to possess an attractively crisp, clean, and refreshing character with some nice depth of flavor. The latter drink even benefitted from a sweet, crispy wonton chip on top.

You, thus, did not feel hard done by the $22 premium, but you also do not see yourself savoring multiple cocktails throughout the course of a meal at Valhalla. Rather, these options serve as luxurious apértifs that avoid detracting from the wine program (along with a modest beer selection) meant to really pair with the cuisine. You many even say that the pricing scheme represents a conscious effort to push consumers toward these other categories (for, as you recall, Gillanders has especially prized both by-the-glass and bottle offerings at his other concepts).

When it comes to the first of these two selections, Prodan has opted for a set of seven wines that are offered—“subject to availability”—by the glass. These comprise a Charles Heidsieck Brut Réserve Champagne ($27), a 2019 Stolpman Vineyards Roussanne-based blend ($21), a 2021 Erste + Neue Gewürztraminer from Alto Adige ($15), a 2021 Selvagrossa “ICA” rosé of Ciliegiolo ($16), a 2020 Kiki & Juan “Orange” wine made predominantly with Macabeo ($18), a 2019 Paul Blanck Pinot Noir from Alsace ($16), and a 2019 Ridge “Three Valleys” Zinfandel-based blend ($22).

While you find that Charles Heidsieck is a bit oversaturated in the Chicago market, the brand forms a reliable option—with some degree of name recognition (and, thus, grandeur)—in the sparkling category. Beyond that, you must applaud Prodan’s offerings for their boldness. The wine director has spurned popular varieties like Chardonnay, Pinot Grigio, Riesling, Sauvignon Blanc, and Cabernet Sauvignon in favor of more characterful bottles that scratch some of the same itches but offer far greater value propositions.

The 2019 Stolpman, for example, is made from 88% Roussanne and 12% Chardonnay, yielding a full-bodied wine with notes of toasty oak sure to please those who love Californian expressions of the latter grape. The 2021 Italian Gewürztraminer, likewise, offers a light, crisp, and aromatic drinking experience replete with ripe tropical fruits that may remind imbibers of their favorite Pinot Grigio or Sauvignon Blanc. When it comes to rosé, the 2021 “ICA”—made from “cherry-like” destemmed grapes fermented in stainless steel—delivers a refreshing, fruity style of blush without commanding the same premium as brands like Miraval. And the Valencian “Orange” wine, while always forming something of an oddball category for wine novices, actually benefits from 10% of Sauvignon Blanc. This, alongside the 90% of Macabeo, makes for a blend of rich texture, medium body, and pronounced apricot flavors adaptable enough to carry through the entirety of the meal.

Prodan’s red selections are a bit more conventional but still rather smart. As Burgundy prices have continued to soar, Alsace presents an attractive alternative for those seeking “Old World” Pinot Noir. Examples from this region may lack the same depth found elsewhere (let alone the excitement of renditions from the Jura), but Paul Blanck provides the bright acid, light cherry tones, and rustic personality one typically wants when seeking a French expression of the grape. Similarly, though the thought of drinking Zinfandel may repulse Cult Cab devotees, Ridge’s polished rendition of the grape offers all the power, concentration, and outright hedonism one might expect from a fancy label of that more popular variety. Unsurprisingly, the “Three Valleys” comes from one of the legends of American winemaking and stands as the kind of wine that can expand the palate of even the most stubborn red wine drinker.