Having just completed a series of articles on three of Chicago’s most enduring fine dining establishments, you now return to another specimen that has reached middle age. Yes, Daisies—like Temporis—first opened in 2017, and that means the restaurant has passed the all-important five-year mark (to say nothing of traversing a pandemic).

It also, you think, falls somewhat into that “contemporary American” genre you have been trying to untangle across so much of your work. At the very least, Daisies prompts a conversation about how a particular cultural inspiration interacts with native ingredients and tastes to form a unique identity that is untethered to tradition (but more on that later).

However, whereas Temporis fights for relevance in the pricey ($215) Michelin-starred tasting menu category, Daisies operates as an à la carte neighborhood joint. In that role, the latter restaurant has not been free from controversy, yet it remains decidedly accessible. Moreover, while Temporis has been defined by chef changes and a corresponding evolution in style, Daisies has stayed true to one man’s vision. Doing so, the concept has expanded its mission beyond mere lunch or dinner and, subsequently, outgrown its original space.

Rather than limping through middle age—warily eyeing each hot new opening as a threat to its dominion—Daisies is undeniably at the peak of its power. The restaurant has not only transferred its success to a bigger building (more than three times the previous square footage) with a renovated kitchen and all sorts of other new features. Located just a couple blocks away from its first home, it not only remains a beloved part of the same neighborhood. But, in an era when many Chicago stalwarts have been lucky to survive (only to slowly, if ever, recover their former glory), Daisies can brand itself using that coveted “2.0” moniker: signaling a clean break, a true upgrade, a new iteration that is (at least) twice as good as what came before.

You have analyzed Alinea “2.0” and “3.0” before. Likewise, you have noted when Kyōten and Oriole each made their respective jumps to the “2.0” version. This nomenclature, sometimes embraced by the establishments or simply applied to them by journalists, is really just a form of shorthand. It does not reflect a change in the chef (as consequential as that may be) so much as a shift in the fundamental nature of the experience. Renovations have changed how Alinea, Kyōten, and Oriole conduct their meals at a spatial level, so service and cuisine have reflexively evolved to best exploit the new environment. Of course, these restaurants likely had some idea of what a downstairs “gallery,” a reconfigured sushi counter, or a sweeping lounge would empower them to do before breaking ground. Yet, it is hard not to think of a new-and-improved “2.0” or “3.0” property in visual terms.

Consumers cannot easily conceive of what a refurbished kitchen, filled with top-of-the-line equipment, might now allow the same craftspeople to do. (Again, it is notable that a change in chef is not typically viewed as an “upgrade” befitting that “2.0” or “3.0” label.) They may taste the difference somewhere down the line. However, the glitz and glamor of those novel accents and fresh materials do the most to promise everything you once loved about a place is still there—only better.

That being said, an evolution from “1.0” to “2.0” or “2.0” to “3.0” does not necessarily attract the attention of Chicago’s “critics.” Often, they—or their publication—has reviewed the property once already and cannot justify committing the resources required to make another visit. Years later, they may eventually have their say, but the story of the restaurant’s growth goes untold as consumers are left to contend with a new iteration of a hallowed concept on their own. Nonetheless, the chef’s reputation and the trust (or awards) they have already earned tend to carry the day: the restaurant is accepted as a clear improvement, and its status among the restaurant-going public grows even as those self-appointed “experts” chase the latest flash in the pan.

This is all to say, Daisies “2.0” found itself in an especially privileged position this year. Perhaps (relative to Alinea, Kyōten, and Oriole) that had something to do with the fact that it did not just renovate (or expand) an existing space but, rather, actually moved locations. Daisies “2.0” did not simply offer a grander version of the same essential concept but dreamt up something more for the neighborhood. The result being that the restaurant was met by an eager media apparatus for whom the launch of a new iteration—not worth closely examining when it occurs at the city’s most influential properties—was suddenly a pressing story.

They scurried over to Milwaukee Avenue and, less than two months after reopening (an abdication of professional standards alongside their inability to visit at least three times), awarded Daisies three-and-a-half stars (“outstanding to excellent”) while also anointing it “the best restaurant in Chicago.” Following in lockstep, The New York Times would name the restaurant one of only two in the city worthy of its “50 places in the United States that we’re most excited about right now” list for 2023. Even Bibendum would get in on the act by awarding Daisies (on top of its longstanding Bib Gourmand) a Green Star.

As you already noted, it is not unheard of for the reboot of an already successful restaurant to earn even higher praise. Plus, considering the concept’s approachable pricing, Daisies makes particularly easy fodder for cash-strapped “critics” looking to direct the masses without engaging in the harder work of cultivating their taste. However, the fact that praise was lavished so eagerly—then echoed nationally in the most patronizing way (more on that later)—can only arouse suspicion.

Either Daisies really is that good, or it has simply positioned itself as the perfect piece of critic bait: a golden opportunity to socially engineer the uncouth public toward appreciating the kind of food journalists think they should be eating. When terms like “the best restaurant in Chicago” have been rendered meaningless by cynical content creators disguised as commentators, and the shades of gray that separate “good,” “very good,” “excellent,” and “outstanding” restaurants are totally obscured, consumers are easily duped by concepts that look good on paper. They are made into patsies for thought leaders who, being so tickled by the thought of championing a place that ticks all the sociocultural boxes at a given moment, have neglected to do their due diligence.

If your posture seems a bit rabid, that’s the point. Chicago’s caliber of “critic” arbitrarily decides when to pan a new restaurant, rush to sing its praises, or put it on the back burner until they can write the review they originally wanted to (but couldn’t justify at the time). Privileging a personal vision of “equity,” rather than articulating a subjective but explicit and consistent standard for discerning quality, they are free to put their fingers on the scale as they please. No matter how clever as the concept looked from afar, as high as your expectations were upon first visiting, in Daisies you sense the traces of those resulting fingerprints.

But you get ahead of yourself.

Daisies is the brainchild of chef-owner Joe Frillman, who grew up in the northern suburb of Prairie View. His great-grandmother “owned two bars in Chicago” (Pauline’s Inn and Spring Mill Inn), and her daughter Daisy (the namesake of his restaurant) “was the person who made sure that food was the focal point of getting everybody together.”

Frillman has noted that Daisy’s influence led him to becoming a chef,” “his cousin to opening a restaurant,” and “many of his other cousins to pursuing careers in food.” Though his grandmother passed away when he was 11, he “got really interested in watching Julia Child” and shows like Yan Can Cook. Frillman paid attention to what his mother did in the kitchen and was also particularly struck by a “great grilled cheese sandwich” his father made him at age seven: “for the first time there was [sic] tomatoes on it,” and he realized “you can take the same thing, kind of, and get a different outcome just by adding certain ingredients.”

Though his parents recommended he attend culinary school, Frillman chose to pursue architectural engineering at North Michigan University and “hated it.” Returning home, the future chef “started working valet” and also helped open Rita Pia’s, a “friend’s pizzeria in Mundelein.” By then, he had already worked in restaurants as a food runner at The Cubby Bear and “as a bar back, as a bus boy, as a dishwasher, you name it.” However, at Rita Pia’s, he ”did everything” and finally decided to attend the Illinois Institute of Art, earning a degree in culinary arts.

While still attending culinary school, Frillman “looked everywhere for a job” but could not get hired due to a lack of kitchen experience. Eventually, he landed at Rick Tramonto’s Osteria di Tramonto in Wheeling’s Westin North Shore hotel. The restaurant was part of a range of concepts that included a “steak house, an osteria, a sushi lounge, [and] Gale Gand’s pastry place.” The staff there, having been “robbed” from Tru, was “just unbelievably talented” and included corporate executive chef Chris Pandel.

Halfway through his time at Osteria di Tramonto, Frillman “sent a letter to The Fat Duck” (then the number one restaurant in the world according to William Reed) looking to “come stage.” Working there taught him “a lot about discipline,” “attention to detail,” “knife skills,” techniques like sous vide, and “what it takes to get to that level.” Returning to Wheeling, Frillman started “tugging on Pandel’s sleeve” and learning things like “butchering salmon,” “breaking down lobsters,” “cooking mushrooms,” and making charcuterie.

When Pandel left to open The Bristol in 2008, Frillman joined him as a chef tournant. The latter would describe the experience—“no prep cooks…[just] four cooks”—as “boot camp and a half.” The cuisine there was “very intricate” but “rustically plated” with a “meat-centric, pork-centric” focus in the beginning. The team took a nose-to-tail approach that involved “a lot of charcuterie, a lot of pickling, [and] preserving” applied to whole pigs, goats, and lamb. Frillman also learned to work “hand in hand” with purveyors Mick Klug Farm and Spence Farm.

Though The Bristol opened with only one pasta on the menu, that expanded to six (all handmade) within a year. The restaurant “didn’t have a pasta cooker,” “extruders,” or any “nice equipment at all.” Pandel would push Frillman “on a daily basis, every single day” to “figure out how to get it done” and “to go, and run, and make the best of the bullshit you’re handed.” But The Bristol was where his career “kind of took off.” Pandel would nominate him as one of Time Out’s “20 Chefs to Watch” in 2011, proclaiming “Joe is still very young but has the potential to do great things in the Chicago culinary world.”

Representative dishes from Frillman’s time at The Bristol include:

- “Fried Shishito, Bonito Flake, Togarashi, Lemon”

- “Roasted Beets, Smoked Mozzarella, Pine Nuts, Pickled Cherry”

- “Head On Prawns, A La Plancha, Anchovy Butter, Tarragon”

- “Raviolo, Ricotta, Egg Yolk, Brown Butter”

- “Fazzoletti, Roasted Cauliflower, Marcona Almond, Saffron”

- “Pappardelle, Stewed Chicken, Sweet Peppers”

- “Pappardelle, Bacon, Chicken Liver, Porcini Butter”

- “Goat Liver Sausage, Rhubarb Mustard, Zucchini, Almond”

- “Cold Smoked King Salmon, Bacon/Dill Dumplings”

- “Pan Roasted Halibut, Parisian Gnocchi, Snap Peas, Cracklin’”

- “Roast Half Chicken, Mustard Spatzle, Crunchy Salad”

- “Goat Merguez, Spicy Rapini, Romesco”

- “Dry Aged Strip Steak, Confit Onion, Roasted Potato, Olives”

Looking back, Frillman would characterize The Bristol as “new American” in theory but “one of the most French-Italian restaurants…[he’d] ever seen” in practice. Departing from the concept in 2011, he spent three months abroad in France, Spain, and Italy. More particularly, in Abruzzo, Frillman “worked on a sheep farm and creamery” where he “spent time cooking, cheesemaking and learning about the simplicity of Italian food and the importance of sourcing ingredients locally.”

Returning to Chicago, Frillman joined Perennial Vivant as a chef tournant. He would describe Paul Virant as “one of the most Italian-cooking individuals” in his own right due to a focus on what’s “in season, around him, what’s available” and on the “simplicity” of serving “three things on a plate.” There, Frillman learned “how to treat people” and “manage people better.” He also learned about “pickling, preserving, [and] jams.”

Frillman left Perennial Vivant after about a year to reunite with Pandel for the opening of Balena (a collaboration between The Bristol’s team and Boka Restaurant Group) in February of 2012. As executive sous chef, he would help the concept earn one of 50 spots on Bon Appétit’s list of “Best New Restaurant” nominees along with a Bib Gourmand from Michelin that same year. Frillman himself would also be named to Zagat’s inaugural “Chicago 30 Under 30” in 2012 (alongside chefs like Matthew Kirkley and David Posey) while, in early 2013, Balena was named a semifinalist for the James Beard Foundation’s “Best New Restaurant” award (alongside Grace).

Described in its own words as “Italian inspired. Honest cooking,” Balena would earn a three-star (“excellent”) review from Phil Vettel declaring “pizzas, pastas, pastries make…[it] a whale of a restaurant.” The Tribune critic would also note that “pizza-and-pasta restaurants are not places one goes in search of imagination, but Balena is the delirious exception.”

Rising to the position of chef de cuisine, Frillman would stay at Balena until 2015 before taking “a couple of years off” to get married and spend time with an “older brother diagnosed with cancer.” This period, in which the chef recognized “there are more important things than food,” would eventually lead to Daisies’s genesis. However, it is worth dwelling on the kind of work Frillman was doing from 2012-2015.

Representative dishes from this era of Balena’s history include:

- “Frillman Farms Arugula Salad, Pine Nuts, Dante Cheese”

- “Coal Roasted Beets, Walnut Pesto, Pickled Candy Onions, Bottarga”

- “Smoked Mackerel, Aioli, Pangrattato, Soft Cooked Egg”

- “Octopus and Farro Verde, Black Olive, Nardello Peppers, Fireball Vinaigrette”

- “Tripe Alla Parmigiana, Grilled Bread, Soft Herbs”

- “Porchetta Di Testa, Lemon, Olive Oil”

- “Spicy Grilled ‘Korean Cut’ Short Ribs, Charred Orange, Basil”

- “Spaghetti Cacio e Pepe”

- “Tagliolini Nero, Crab, Sea Urchin, Chile”

- “Hen Egg Tajarin, Sage, Brown Butter”

- “Orecchiette, Lemon, Kale, Bread Crumbs, Chili”

- “Chitarra, Snail Bolognese, Herbs, Bread Crumbs”

- “Sardinian Style Gnocchi, Chicken Sugo, Burnt Escarole, Preserved Lemon”

- “Rigatoni, Pork Ragu, Porcini Mushrooms”

- “Strozzapreti, Rabbit Sugo, Rosemary, Olives”

- “Pappardelle, Lamb Sugo, Castelveltrano [sic], Orange, Pecorino di Fossa”

- “Paccheri, Lamb Pancetta, Smoked Potatoes, Collards, Pecorino di Parco”

- “Pumpkin Tortelli, Lamb Pancetta, Pecorino di Parco, Amaretti Cookie”

- “Potato Gnocchi, Beef Heart Bolognese, Pecorino Romano”

- “Grilled Prawns, Garlic Aioli, Fried Prawn Heads, Campari Vinaigrette”

- “Wood Roasted Great Lakes Trout, Beluga Lentils, Cilantro Salsa Verde”

- “Cornish Game Hen, Pinenut Dressing, Braised Greens”

- “Gunthorp Farms Salt & Pepper Chicken Thighs, Spicy Romanesco, Anchovy”

- “Catalpa Grove Rotisserie Pork Chop, Long of Naples [Squash], Mustard Greens”

- “Spicy Flap Steak Rotolo, Cranberry Beans, Grilled Green Beans, Pickled Wax Beans”

Served alongside wines from producers like Allegrini, Azelia, Paolo Bea, Ca’ del Bosco, Cavallotto, Ceretto, COS, Dominus, Gaja, Giacomo Conterno, Foradori, Bruno Giacosa, Bibi Graetz, Le Macchiole, Miani, Montevertine, Occhipinti, Ornellaia, Passopisciaro, Quintarelli, Roagna, Sassicaia, Shafer, La Spinetta, Terlano, Tua Rita, Elena Walch, G.D. Vajra, Venica & Venica, Vietti, and Roberto Voerzio.

While these dishes are decidedly (and deliciously) “Italian-Italian,” you appreciate the menu’s dizzying array of pasta shapes, playful bursts of creativity (Fireball vinaigrette, Campari vinaigrette), worldly inflections (Korean-cut short ribs, snail bolognese), and local sourcing (Gunthorp Farms, Catalpa Grove Farm). On that latter point, you cannot help but notice the “Frillman Farms Arugula Salad.”

Incorporated by Joe’s younger brother Tim in 2011, Frillman Farms represents the revival of the family’s “farming roots [that] date back to the 1800s in Buffalo Grove, Illinois.” Its “eight-acre Prairie View plot” had been “leased out to neighboring farmers for the past few generations.” However, Tim retook control of the land and began cultivating heirloom, GMO-free crops (like beets, herbs, lettuces, onions, and radishes) along with more than a dozen varieties of pepper and more than 25 varieties of tomato. He also harvested eggs from more than 200 “roaming laying hens” and produced honey from six beehives before expanding his operation by purchasing Leaning Shed Farm and relocating to Berrien Springs, Michigan (while retaining the original Prairie View property).

Ultimately, Frillman Farms’s produce would play a decisive role in shaping Daisies’s identity: “part of the reason” Frillman started the restaurant was so he “could use…[Tim’s] great stuff” after Balena, once the chef left, “didn’t buy as much of it.”

But, back in January of 2017, the restaurant was still only in its earliest stages of planning. Coming back from his couple years off, Frillman would announce—via the Tribune—that he was bringing a concept “focused on vegetables grown in the Midwest and pasta” to Logan Square. He would be taking over the former space of “beloved…cocktail bar and Cajun restaurant” Analogue at 2523 N Milwaukee Avenue. Otherwise, it would only be revealed that the chef would be sourcing ingredients from brother Tim’s farm, which had just won a 2016 Frontera Farmer Foundation Grant to aid in “construction of a modest washhouse for vegetable preparation and packaging.”

By May of 2017, Frillman could announce that Daisies would be opening in June; however, details still remained sparse. Nonetheless, speaking to Michael Gebert that following July, the chef-proprietor would provide more context regarding the development of restaurant. Frillman originally wanted to open a barbecue place but was wary of profiting from “the environmental impacts of all that” (though he still eats it). Still, he sought to get back into the kind of food he “wanted to do” and that he “might not have had the free rein to do.”

More specifically, Frillman had grown to miss the “connection with the diner” and “connection with your employee” that characterized The Bristol—as compared to Balena, where his staff numbered 50 and included prep cooks that only worked in the daytime. The chef “wanted to open a place where the same people are here all day” and to “create opportunities for them.” He wanted the team “to have a good time” because “this industry sucks.”

At Daisies, Frillman would have “two cooks,” and they would look to bring the kind of food he likes to eat to an area that had “something missing.” Still, he would be running a “neighborhood restaurant, first and foremost,” with a “walk-in only” patio and bar. They would also consciously cater to families, not through a “dedicated kids’ menu” but simply by preparing “whatever your kid wants to eat.” The chef’s logic was that he would rather have them “come here and eat vegetables out of a farm that’s sustainably grown 30 miles away” than “going into the refrigerator eating fruit snacks or chicken nuggets.”

For the adults, Frillman would be taking inspiration from places like SPQR and Flour + Water in San Francisco. The menu would feature “10 or 12 starters” drawn “primarily out of what we can get from the local farms.” His brother’s “eight-acre garden” would “inspire the menu exponentially,” but other purveyors like Green Acres and Mick Klug could help to fill in any gaps. Complementing the starters would, “ideally,” be “10 or 12 pastas” along with a plan to take “all the things that go into trash” at the restaurant “and turn them into vinegars, kombuchas, you name it.”

When Daisies launched on June 7th, Frillman would reveal his inspiration came from a pithy hypothetical question: “if the Midwest was a region of Italy, what would the food look like?” While the chef-proprietor didn’t “want to label this as an Italian restaurant,” he acknowledged “everyone associates pasta with Italy.” Instead, the menu would reflect “who he is and where he’s been”—like a beet-infused “Agnolotti” previously served at Balena or a “Spring Onion Dip” (with ridged potato chips) referencing the chips and dip he enjoyed “at family gatherings growing up.” Additionally, despite the “emphasis on vegetables,” dishes would “not necessarily” be vegetarian. Rather, Frillman would not be “shying away from fats” or “shying away from meats” as a complement to fresh produce.

As a “family restaurant,” Daisies had “four or five highchairs at the ready.” However, Frillman would also close on Mondays and Tuesdays “so his staff can spend time with their families.” This same sense of kinship was not only expressed through the restaurant’s name and its sourcing from brother Tim’s farm. Frillman’s sister Carrie also painted “large and arresting watercolors of vegetables hanging in the dining room” (“slated to change with the seasons and what’s growing in the fields”) and his mother Nancy “helped set up” the 70-seat space.

In July of 2017, the Chicago Reader would be the first to weigh in on the restaurant’s actual quality. Mike Sula praised dishes like “tempura-battered mushrooms and cheese curds with a tangy green goddess dressing” (something “Frillman’s future regulars will never allow him to take off the menu”), “singular” whole wheat tagliatelle with fava bean leaf pesto, “toothy pappardelle in a chunky mushroom sauce,” “pillowy, browned” pierogi, and an “extraordinarily satisfying” tajarin with crumbled fried chicken skin. The critic also liked the “user-friendly wine list” with a “two-tier price-point format” of $39 or $59 for all bottles (that are also offered by the glass).

In contrast, Sula derided three “disturbing” dishes: a “sweet, soft carrot mass” cooked in duck fat, a “plate of glistening blood-red agnolotti” (“like something a surgeon might remove from the lower thorax”), and “planks of fried, dry” cornflake chicken. He also disliked the “small, close, and claustrophobic” front dining room (that also gets “clammy” on warm evenings) and dessert that seems “an afterthought.” Still, “apart from a few dishes that ought to be rethought,” the critic found Frillman to be “a chef of enough original talent” to transcend any lingering bitterness over Analogue’s closure and get people to talk about Daisies “wholly on its own terms.”

Michael Nagrant, writing for RedEye in August of 2017, would award the restaurant two-and-a-half stars (between “very good” and “excellent”) while praising the “fantastic and interesting bottles” on the wine list, “pillow” pierogi, stracci with “perfectly toothsome peas,” “tajarin…tossed with butter and Parmesan,” and cornflake chicken that was like “a superior and epic chicken nugget.” Alternatively, he noted “missteps” like “overcooked” and “mushy” zucchini, leeks that “could have used a touch more salt,” and a Kahlua cake that “yearned for a touch more coffee essence.” Still the critic judged that “Frillman has succeeded in creating simple, satisfying fare from local produce” and, additionally, “is making some of the best fresh pasta in Chicago right now.”

Time Out would have its say later that same month, with Maggie Hennessy awarding Daisies four out of five stars. She praised fried shiitakes and cheese curds that “oozed just enough inside,” a “pillowy burrata starter,” “toothy pappardelle ribbons…with just enough sweet mushroom ragu,” “supple yet textural, light yet indulgent” tajarin, and a “hearteningly crispy skinned” sturgeon entrée. Duck fat-cooked carrot rillettes were “almost too subtle” relative to their “bold companions” and desserts were “less intriguing” than the savory fare. However, the concept impressed as “an easygoing spot with can’t-miss pasta.”

A day later, writing for Chicago, Jeff Ruby praised dishes like “soft and modest” burrata he would order “every time,” “gentle, earthy” leeks served with “puckery mustard hollandaise,” carrot rillettes (“just vegetables, treated right”), and pastas that are “among Chicago’s best.” More particularly, the critic liked the “buttery stracci,” and “toothy, mint-kissed Piemontese tajarin” as well as the “flaky Lake Superior whitefish.” In contrast, the cornflake chicken (“having been pounded into bland submission”) again “disappointed” while desserts were “limited.” Regardless, Ruby found himself “besotted” with Daisies and concluded that it charms “with a straightforward menu and homey atmosphere.”

On the back of all this positive local press, the restaurant would end its opening year on a triumphant note. Time Out would name Daisies one of 10 “best new Chicago restaurants and bars of 2017,” citing the “homey, understated space” and housemade pastas “dressed up with thoughtful ingredients.” Vogue would honor the concept as one of “6 Chicago Restaurants You Should Know About Now,” noting its “locavore-meets-Abruzzo point of view” where “vegetables are the true stars.” Forbes would get in on the fun by naming Daisies as one of eight establishments on its list of “Chicago’s Best New Restaurants,” praising pasta that is “just as good if not better” than what Frillman was “making at Balena previously.” Finally, in January of 2018, the concept would clinch the “Best Neighborhood Restaurant” award (beating out Le Bouchon, Old Irving Brewing Co., and Osteria Langhe) at that year’s Jean Banchet Awards.

The remainder of 2018 would be defined by a few key developments. In March, Daisies would begin serving Sunday brunch, with unique dishes like “Tajarin Carbonara,” “Sweet Fried Pierogi,” and “Scrambled Egg Bruschetta” joining the menu. In September, the restaurant would earn a Bib Gourmand as part of Michelin’s forthcoming 2019 Guide, with inspectors citing “fantastic pastas” alongside “execution, hospitality and creativity” that make the concept feel “like a true neighborhood spot, down to the regional wines.”

December would see Daisies featured, alongside Fat Rice, as one of several “restaurants…adding a new surcharge to your bill to cover the costs of employee health insurance.” In truth, Frillman had been engaging in this practice for “about a year” before CBS came calling. However, in the article, the chef-proprietor revealed he “didn’t go to the dentist for seven years” earlier in his career and, upon finally going, “the bill ended up being 3,500 bucks” due to a lack of insurance. He “didn’t want his staff to go through that” and “wanted to make sure they’re taken care of” while also viewing the decision as a way to “attract and retain talented workers in short supply.” At Daisies, “about a dozen employees pitch in about $100 per month,” with the employer paying “the rest” via the surcharge. Frillman suspected “larger restaurants may be doing the same,” but by “just increasing the cost of food without the consumer knowing were the extra money’s going.” Thus, transparency surrounding the practice was a way to ensure it didn’t seem like the added sum is “going into the owner’s pockets.”

At the time, the exact language used on the restaurant’s menu to note the surcharge was as follows:

“A 2% charge is applied to all bills to help us offer health insurance to all of our Daisies family.

The majority of the cost is covered by the business, and our team themselves, like any employee-provided health insurance plan. This surcharge allows a small, family-owned business to offer such benefits. We hope that in so doing we can encourage this practice to take hold in more restaurants across the city and the country. We are doing what we can to make the hospitality industry a healthier place.

Please inform management if you would not like to contribute. We will remove the charge.”

The dawn of 2019 would again see Daisies nominated at the Jean Banchet Awards, this time for “Best Service” (losing out to Temporis). The restaurant would also retain its Bib Gourmand, this time being praised for “its tiny but earnest and hardworking kitchen, clean, mid-century modern design and decidedly affordable prices.” Michelin even went so far as to say “this local charmer can do no wrong” while highlighting the “house onion dip,” “fried mushrooms with cheese curds,” “tajarin carbonara,” and “mezzaluna stuffed with fermented squash and lamb.” The very beginning of 2020 would also see Thomas Leonard (former chef de cuisine of Acanto and Walton Street Kitchen) come aboard as Daisies’s culinary director—a position in which he soon found himself being forced to totally adapt.

Representative dishes from Daisies’s pre-pandemic era include:

- “Radicchio and Peach Salad” (Prosciutto/Blue Cheese/Onion Vinaigrette)

- “Cauliflower & Broccoli” (Calabrian Chiles/Parmesan/Pine Nuts)

- “Sweet Corn” (Blueberry/Bacon/Mint)

- “Zucchini a la Plancha” (Calabrian Chili Oil/Goat Feta/Cashews)

- “Polenta Waffle w/Red Kuri Squash” (Roasted Iroquois Corn Meal/Pork Lardo/Balsamic)

- “Fried Polenta” (Spring Pea Medley/Strawberry/Beef Bottarga)

- “Chicken Fried Rutabaga” (Pork Sausage Gravy/Fermented Peppers)

- “Roasted Cabbage” (Braised Beef/Caraway/Ramps/Tinned Clams)

- “Celery & Cherries” (Smoked Sturgeon/White Beans/Pine Nuts)

- “Overpriced Tomato” (Heirloom Tomato/Bone Marrow/Cheap Balsamic)

- “Tortellini” (Lentils/Collard Greens/Pork Sausage)

- “Linguine” (Ramps/Pickled Pears/Bacon/Egg Yolk)

- “Fazzoletti” (Lamb Sugo/Heirloom Peppers/Pecorino)

- “Tajarin” (Turnips/Horseradish/Chicken Cracklin’)

- “Pierogi” (Potato/Mussels/Beer You Cook With)

- “Stracci” (Lamb Sugo/Broccoli/Pecorino)

- “Ravioli” (Celery Root/Black Truffle/Hazelnuts)

- “Triangoli” (Broccoli/Ricotta/Fontina/Almonds)

- “Tagliatelle” (Fava Leaf/Carrot/Sarvecchio/Pistachio)

- “Gnocchi” (Sunchokes/Sunflower Seed Pesto)

- “Gnocchi” (Morels/Caraway/Aged Parmesan)

- “Raviolo (BIG ONE) w/ Truffle Cheese” (Nettles/Egg Yolk/Brown Butter)

- “Cavatelli” (Zucchini/Mint/Feta/Bottarga)

- “Manti” (Fermented Squash/Smoked Onions/Neonata)

- “Chitarra” (Guanciale/Green Garlic/Rhubarb)

- “Lake Trout” (Almond/Confit Potatoes/Preserved Peppers/Oregano Salsa Verde)

- “Chicken” (Roast Chicken/Chicken Brat/Watercress/Pickled Red Onion)

Alongside wines from producers like Bonny Doon, Brooks, Hermann Wiemer, Illinois Sparkling Co., Left Foot Charley, Liquid Farm, Lo-Fi, Ovum, Schramsberg, Tablas Creek, and Wyncroft.

As the COVID-19 pandemic took hold in March of 2020, Daisies, like many restaurants, organized a fundraiser for its employees before shifting to carry out and delivery (including pasta kits) just a few days after ceasing indoor service.

Frillman would note that the restaurant was “finally in a place where…[they] had the best staff…[they’ve] ever had.” It took “a lot of time to get a group of people who work very well together,” and shutdown meant it all “came crashing down.” The chef-proprietor “had to let twenty-six people out of thirty-two go,” people he was used to seeing more than his “actual family.” Still, there were rays of hope: the local community came out to support the restaurant with well wishes and tips of “fifty to a hundred percent” on delivery orders. Likewise, Frillman’s greatest hope was that “an industrywide change in the way employees receive benefits” would come out of this period.

Though there was a “great response” to the restaurant’s pickup and delivery options, Frillman “decided to shut down the restaurant April 1” and “take a step back.” Daisies was “almost too busy,” the staff was “tired,” and he “wanted to see how things would play out.” In early May, the chef-proprietor looked ahead to “long-term changes” by partnering with his brother to offer “market boxes of produce” (alongside housemade pasta by the pound and more pasta kits) for pickup throughout the city. Frillman also envisioned “continuing produce sales even once Daisies reopens” by reconfiguring “its back room into a market, which would sell produce from the farm and items made in the Daisies kitchen.”

By the middle of May, the restaurant’s “next chapter as a restaurant-market ‘hybrid’” was ready to launch. Daisies opened its virtual market and began selling items pasta, pasta sauce, ramp butter, and jellies online alongside products from purveyors like Mick Klug Farm, Preserved States, and Green Circle (chicken). The restaurant also began hosting “small in-person markets” with “a few local food purveyors every Sunday” to help make up for lost revenue due to the closure of the Green City Market and Logan Square Farmers Market. These offerings would be joined by the resumption of pickup/delivery service and the sale of wine, beer, and “Bloody Mary kits.”

With the arrival of June, Daisies began offering patio service while continuing its virtual market and in-person Sunday shop. For its efforts, the concept would be named one of the “best outdoor restaurants in Chicago” by Time Out in July. In August, Frillman took things one step further by transforming his “back dining room into a grab-and-go market that’s stocked with fresh produce, everyday cooking essentials and locally sourced treats” for sale every day. Doing so, they would partner with even more local purveyors like Catalpa Grove, Beautiful Rind, and Publican Quality Bread. The chef-proprietor had “wanted to do this” before Daisies opened, but they “didn’t have the resources or time in the beginning.”

Concurrent with this more permanent market, the restaurant would continue offering takeout and delivery while also operating dine-in service. Guests eating at Daisies could browse the market at the end of their meal, “with servers packaging up any food items they might wish to take home” and cooks offering “tips for how to use certain ingredients.” Frillman was “able to bring back about 50 percent of his staff” through these ventures and even achieved another “pipe dream for the restaurant.” Daisies launched lunch service: originally planned as a “casual sit-down experience” but substituted for “a grab-and-go deli concept aimed at fueling remote workers who live in the area.” This would include “pints of cold salads (potato, pasta and broccoli)” as well as “specialty sandwiches like the Turkey Rachel, with fried shallots, thousand island dressing and purple coleslaw.”

Though there were still a few more bumps in the road to navigate, Frillman, in December of 2020, could begin to look beyond the pandemic toward the future. Asked which of his “innovations will remain in place,” the chef-proprietor responded “all of them.” That meant the “indoors farmers market is going to stay,” lunch service would be extrapolated “to a brick-and-mortar setup,” and delivery would remain an option for “slow night[s]” and “huge snowstorm[s]” to still sell their food.

By March of 2021, indoor dining at Daisies was back on track five nights a week. At that time, the restaurant also welcomed Katherine Sturgill as its wine and beverage director. Later, in April, the concept would retain its Bib Gourmand. And, that same month, Frillman would appear on CNN advocating for independent restaurants’ share of COVID-19 relief funds.

With lunch, brunch, the market, and dinner service all running at full steam, Daisies marked its fourth birthday in June of 2021, retained its Bib Gourmand (once more) in April of 2022, and in the middle of that same year (at the time of its fifth birthday) announced that “version 2.0 of the Daisies experience” would arrive in 2023.

Before engaging with what this reboot entailed, it is worth dwelling on some representative dishes from 2021-2022:

- “Cabbage” (Apricot Saor/Bagna Cauda/Pistachio/Dill)

- “Peach Panzanella” (Cherry Tomato/Goat Cheese Curds/Ciabatta)

- “Pear Salad” (Kale/Kohlrabi/Almonds/Pleasant Ridge Reserve)

- “Leek Tart” (Marsala Onions/Pecorino Fonduta/Pickled Ramps)

- “Asapargus” (Pickled Fennel/Cured Egg/Fontina Fonduta)

- “Fried Green Tomatoes” (Sour Corn/Dill Yogurt/Harissa)

- “Sunchokes” (Grapefruit/Fennel/Goat Cheese)

- “Brussels Sprouts” (Smokey Blue Cheese/Walnuts/Bacon Vinaigrette)

- “Green Beans” (Surryano Ham/Hard Cooked Egg/Croutons/Grain Mustard)

- “Shishito Peppers” (Smoked Sturgeon/Preserved Lemon/Espelette)

- “Fennel” (Marinated Mussels/’Nduja/Green Garbanzo/Kumquat)

- “Sweet Potato” (Salsa Verde/Fresh Chevre/Pecans/Calabrian Chili)

- “Rutabaga Latke” (Pickled Ramps/Rutabaga Pastrami/Apple Butter)

- “Spring Onions” (Bone Marrow Bagna Cauda/Lavender/Cheese Toast)

- “Turkey Liver Mousse” (Smoked Turkey Heart/Pear/Schmaltz Tart)

- “Ravioli” (Truffle Ricotta/Brussels Sprouts/Pancetta/Roasted Grapes)

- “Ravioli” (Truffle Ricotta/Sweet Corn/Jalapeno/Basil)

- “Tagliatelle” (Pumpkin Bolognese/Green Olives/Peptitas)

- “Potato Gnocchi” (Confit Chicken Thigh/Whey/Parsnip/Breadcrumb)

- “Gnocchi” (Pickled Cherries/Burnt Cabbage/Pistachio/Fontina)

- “Gnocchi” (Morels/Spruce Tips/Parmesan)

- “Cassarecce” (Clams/Green Garlic/Spring Onion/Breadcrumbs)

- “Risotto” (Asparagus/Preserved Lemon/Sorrel)

- “Risotto” (Summer Squash/Pine Nuts/Neonata)

- “Risotto” (Radicchio/Hen Of The Woods/Balsamic)

- “Manti” (Winter Squash/Pancetta/Neonata/Amaretti)

Alongside wines from producers like A Tribute to Grace, Au Bon Climat, Cruse Wine Co., Failla, Jolie Laide, Martha Stoumen, Matthiasson, Minimus, Presqu’ile, Ridge, Ruth Lewandowski, Sandhi, and Stolpman.

Looking back, these years reflect a meaningful degree of growth from the pre-pandemic era, with a range of new produce-forward starters, new pasta shapes, and ingredient combinations to dress those pastas (both new and old) on display. Favorites like the “Onion Dip,” “Fritto Misto,” “Tajarin,” “Agnolotti,” and “Pierogi” did indeed remain while proteins like the “Cornflake Chicken” were totally eschewed (a safe choice given their reception and the broader circumstances of the era). Sturgill’s work with the wine program, you must admit, also deserves praise. Though no longer sticking to the $39 or $59 format for bottles (the focus being more on selections under $100 at this point), she added a smart smattering of top-value producers to rejuvenate a list that, before the sommelier’s arrival, you can only term middling.

In October of 2022, Frillman would share more details about the Daisies reboot. The story was not so much about building a “2.0” restaurant, but transforming the old address into a “permanent market, café, and bar.” Frillman noted that demand for what amounts to a “grocery store” in the neighborhood was “clear,” with local customers showing up “multiple times a week now” instead of “just once in a while for dinner.” Committing fully to the market concept would allow him to “give his staff new experiences and opportunities” while also starting a community-supported agriculture program and “expand[ing] the restaurant’s fermentation program into a line of retail products.” He would continue serving lunch in addition to offering “cocktails and other drinks in the evening so people can gather.” That sense of creating “a neighborhood place where you see the same people, their families” and the resulting “community building” would also prove to be one of Frillman’s biggest inspirations. For what it’s worth, the “original restaurant” would be “moving to a much larger space nearby” too.

A month later, the chef-proprietor would admit the original Daisies space “was never meant to be a restaurant” and “wasn’t efficient” for the amount of volume they were doing. With seven years left on their lease and “200 condos across the street, with no food for these people outside of a Target,” it made “all the sense in the world” to make the market a fixture. Frillman had expanded his staff from 25 people (pre-pandemic) to 38, and staff tenure had “never been longer.” He credited that in part to providing “health benefits, a 401K retirement match, and…paid time off” for his employees.

The development of these of these other revenue streams (the market, meal kits, retail products) would help “maximize” the business so it was “sustainable for the staff.” That even extended to “using the all-day functionality of the restaurants” to give people “different schedules entirely” and better support work-life balance (especially those raising families). Ultimately, growing Daisies would grow opportunities for this long-term staff and eventually allow the restaurant’s culture to propagate itself.

On the culinary side, Frillman envisioned the market as a place where “you’ll be able to walk up, order a sandwich, get your produce for the week, a pound of turkey, and a bottle of wine…pick up your CSA box, also order a pound of pasta sauce, maybe a sous vide steak for dinner.” The building’s back patio would be enclosed to become year-round, and the space would be used, along with the bar, to offer a dinner service. Frillman described the menu as “casual in the sense that while people can go there and eat an entire meal, it’ll be a lot of craveable, shareable snacks.” The chef-proprietor would look to take “whatever doesn’t sell” and “use [it] for the menu,” meaning the food will “naturally be vegetable-forward.” He would also admit he was “really excited for the grocery dinner concept,” taking additional inspiration from the salumeria and restaurant Roscioli in Rome (where he was “nonchalantly” served some of the best food he’s “ever had”).

By December of 2022, Daisies was set to open the “2.0” version of its restaurant at 2375 N Milwaukee Avenue (about 500 yards from its original home/the forthcoming market) in February of the following year. At the time, Frillman also revealed that he had an ace up his sleeve. He had brought on Leigh Omilinsky, an old colleague from his time working for Tramonto in Wheeling and most recently the executive pastry chef for Boka Restaurant Group, as head pastry chef and partner of what Frillman would title Radicle Food Group. Omilinsky would look to “revamp the menu with eight desserts” that fit the restaurant’s “Italian meets…Midwestern” ethos while also filling the pastry case for a “morning café component.” She was described by her new partner as “probably one of the best pastry chefs in the city” and a “huge asset” for the group’s growth.

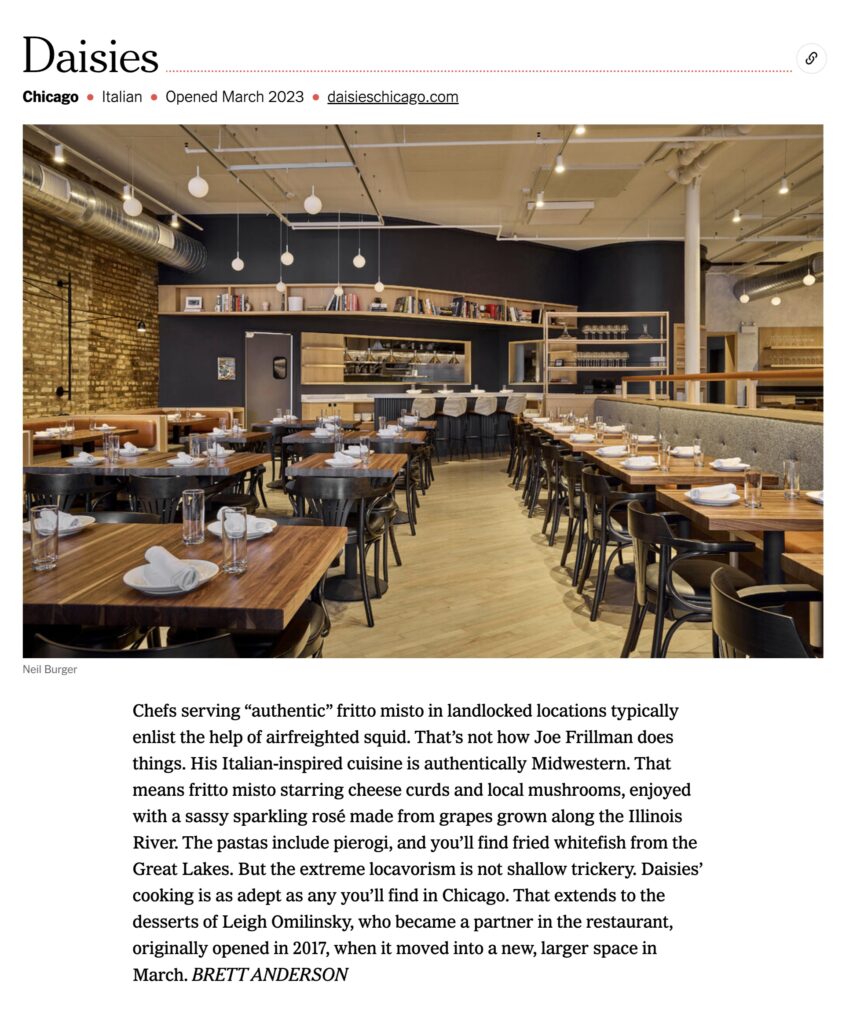

In truth, Daisies “1.0” would not complete its final service until March 5th of 2023. Such delays are to be expected, especially considering that Frillman “gutted” his new 5,500-square-foot location, formerly home to “German beer hall the Radler,” and “added an espresso bar, pastry counter, grab-and-go area, and 30-seat private dining room.” There would even be a “pasta and pastry production room” that could host classes, book signings, or a “quieter” dinner. Finally, on March 29th, Daisies “2.0” was ready to welcome guests into the 110-seat space: first, only in the evenings but quickly followed by morning café service in April.

On May 15th, the revamped concept received its first major piece of praise, earning three-and-a-half stars (“outstanding to excellent”) from the Chicago Tribune and being termed “one of the best new restaurants in Chicago.” The article would admit you “can go to Italy and find wonderful things” but “can’t go anywhere except Daisies to find its particular and sometimes peculiar collection of dishes.”

Of these, a “jumbo ramp raviolo,” which “only graces the menu for about three weeks,” was labelled the “must-order dish of the moment” and complimented for its “beautiful balance” of fattiness and bright sweetness. A daytime “asparagus and burrata brioche cream bun” was titled “some of the best brioche” the critic has had while “potted carrots,” a holdover from the original menu, “skyrocket[ed]” from “starter to stellar” with the addition of “housemade gnocco fritto.” The pierogi, another holdover, were “impossibly delicate,” and the pork tenderloin “thick yet transcendently tender.” Only salmon collars “seemed off” due to a “sulfurous note,” but the item was ultimately taken off the check (with the critic resolving to ask for them “well done” next time). Other highlights included an “earthy yet tart nonalcoholic take on the mushroom margarita,” a creation offered on the Daisies menu “since 2019” when Frillman took a trip to Blue Hill at Stone Barns and came home asking “what is a margarita in the Midwest?” Of Omilinsky’s work, a parsnip gelato was “ethereal” and various “treat-sized” desserts were termed “perfect.”

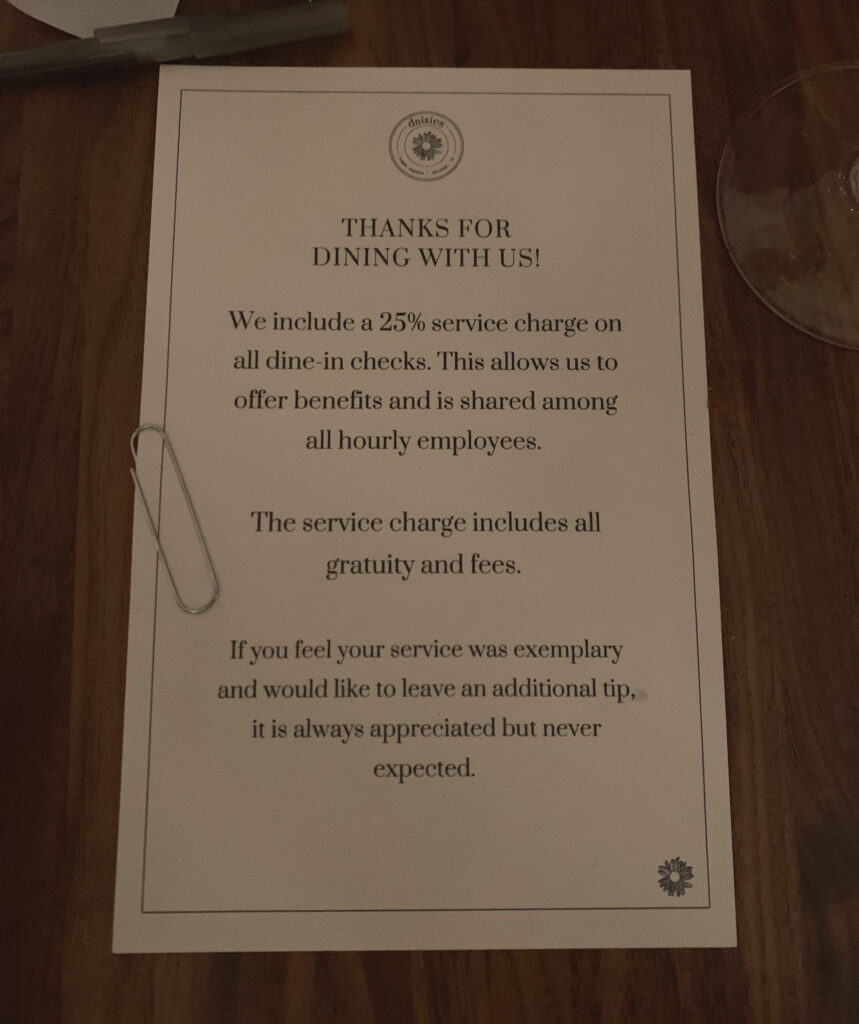

To hear the Tribune tell it, Daisies did not do a single thing wrong during the course of one dinner and a subsequent visit to the café (a rather dubious set of experiences on which to issue a permanent star rating). The critic, as you mentioned, even found a way to contort the lackluster, “sulfurous” salmon collars as indicative of a mere difference in personal preference. This all starts to make sense as the article reveals how they are “most” impressed by the restaurant’s “radical decision” to apply a 25% service charge to “dine-in checks to benefit all of the staff” (something Daisies “began implementing in June 2020”). Citing their firsthand experience with “the racism and sexism of tipping,” the critic looks to defuse “online outrage” regarding the practice by affirming the 25% surcharge is “seamless and clearly explained” with “no pushback” from the tables around them “on a busy Friday night.” For what it’s worth, the article assures readers that servers “do not expect a tip on top of that” and reveals that, “if service gets overwhelmed, the restaurant will remove the service charge.” But, in responding to “people who say to just build it into the price” (by answering—without drawing on any evidence—that it “rarely, if ever, works”), the critic makes clear they are rewarding the restaurant for practices they personally approve of rather than what is simply “on the plate.”

On May 26th, Michael Nagrant—who you might remember awarded Daisies two-and-a-half stars when writing for RedEye—went one step further. The “2.0” version was not “one of the best new restaurants” but “the best restaurant in Chicago.” Doing so, the critic framed the concept as the “only one” he’s “positive recent immigrants, Logan Square hipsters, tech billionaires, and heartland farmers will love with similar fervor.” He also predicted “Michelin will probably reward Daisies one star” and even alleged other writers are “not allowed to award the true numerical greatness of Daisies” or give it four stars “because you been made to believe that rating is only reserved for certain kinds of restaurants and chefs.”

More particularly, Nagrant praised the same “jumbo ramp raviolo” as reflecting how Frillman has “taken the best traits” of his mentors while adding “his own Midwestern sensibility” and “regard for traditional European foodways” to “create a style that is greater than the sum of all its inspiring parts.” With pickled Mick Klug ramps providing “a confetti of lifting acidity to cut through the richness of the pasta,” he tasted “Midwestern spring, Italian winter” and felt “the souls of Pandel, Virant, [and] Michael Carlson (Schwa)” in the dish. The critic also “died over” a rigatoni with the “salty beyond beef richness” of ‘nduja and “the fizz of fermented tomato” while gnocchi were described as “pure potato clouds with barely a whisper of gluten to keep them square.”

Moving beyond pasta, a preparation of beef tongue was termed “smoky and delicate like the love child of a flavorful ribeye and tender filet mignon.” The mushroom, artichoke, and cheese curd fritto misto, beloved from Daisies “1.0,” boasts nothing “a blindfolded red stater wouldn’t absolutely rave about on his barbeque-joint-review YouTube channel the next morning.” This kind of customer (“bubba”) would also love a “mahogany-dark” fish fry “swimming in the tastiest of tartar sauces.” Turning toward dessert, Omilinsky drew praise for a rhubarb-larded “crostata masterpiece,” “oven-warm” oatmeal cream pies, and a “genius,” “hospitality-forward offering” of seven different $4 mignardises. Additionally, Sturgill’s selection of “affordable natural food-friendly whites and reds” is called “superlative” while bar manager Seth Marquez’s cocktails also draw compliments.

Nagrant also enjoyed the “warm and inviting” nature of the setting and a style of service that “embraces children not only with their food, but also in its hospitality.” With regard to the 25% surcharge, the critic admits he “fully support[s]” and “believe[s] in” the practice but also notes the associated signs and notes and waiver introduce “a layer of friction and momentary pause” into the experience. He contends that he prefers folding “the service charge into the menu price” and eliminating “a tip line on the final check” (as Thattu does), but Daisies is “extraordinarily and well differentiated” in a way that “they can get the revenue however they wish with little to no negative outcome.” Frillman, to that point, is praised for his “smart vertical integration” and having “the best interest of every one in mind.” Ultimately, Daisies is a place to “be in the moment, be human, be inspired, be fed, and be alive.”

When The New York Times included Daisies on its list of “50 places in the United States that we’re most excited about right now,” the Gray Lady would confine itself to a mere blurb. The restaurant earned praise for its pierogi, “fried whitefish from the Great Lakes,” Omilinsky’s desserts, and wines like a “sassy sparkling rosé made from grapes grown along the Illinois River.” Additionally, the “Italian-inspired cuisine” was termed “authentically Midwestern” with a current of “extreme locavorism” that “is not shallow trickery” but backed by cooking “as adept as any you’ll find Chicago.”

However, the blurb’s biggest highlight is the “fritto misto starring cheese curds and local mushrooms,” which is used to draw a contrast between “how Joe Frillman does things” and how chefs “serving ‘authentic’ fritto misto in landlocked locations typically enlist the help of airfreighted squid.” This calls what Nagrant said about the “blindfolded red stater” to mind, and it also harmonizes with what The Infatuation had to say about the dish: “Daisies turns something that belongs at the State Fair into a delicate appetizer.”

These statements, though disparate, seem to get at the same idea. Doing so, they just about give the game away: Daisies is portrayed as the antidote to the kind of backwards cooking that goes on in the “flyover” Midwest. Frillman impresses both by transcending the worst habits of the region (“airfreighted squid”) and by subverting expectations through the transformation of slummy state fair fare into something “delicate.” Thus, he not only pleases his Logan Square regulars but stands to convince red-state rednecks as to the virtues of “extreme locavorism” as well.

There is nothing wrong with this argument in theory. Great chefs are great in part because they effectively communicate their ideas and expand appreciation for their work beyond those who form its conventional audience. However, in the writing of The Hunger, The New York Times, and The Infatuation you detect traces of shame. You sense a smidge of that patronizing, social engineering mindset that says: “even the most regressive of my hick neighbors will eat this shit up.”

Onion dip, fritto misto, and pasta, then, form something like trojan horses for the propagation of the writers’ pet causes: equitable pay for front and back of house, the abolition of the “racism and sexism of tipping,” the privileging of local sourcing, and the corresponding development of a hyperseasonal Midwestern (through an Italian lens) cuisine. You cannot disagree that these are noble aims. Rather, you simply doubt the validity of two local critical accounts that found nary a thing to criticize at Daisies. Knowing the authors’ sympathy for (or even defense of) the causes the restaurant fights for, you can also understand the temptation to cheerlead the concept so hyperbolically.

However, adopting a less charitable and more rigorous approach, it seems right to ask: do Daisies’s front- and back-of-house staff deserve, in terms of the quality and consistency of their work, what amounts to a 25% forced gratuity? This seems like the right way to judge whether that added fee would be better off baked into the menu prices (with expectations being shifted more toward the overall value proposition of the establishment rather than individual employees). Likewise, does Daisies’s cuisine (and, in particular, the produce sourced from Frillman Farm) measure up to the sterling quality that has been asserted? The collaboration between brothers sure sounds good on paper but quickly begins to stink if it becomes at all unclear what you are paying a premium for.

Asking these questions will help prompt a careful evaluation of the work Daisies is doing without being led astray by the chance to opine on the restaurant’s feel-good practices (let alone rushing less than two months after opening to celebrate them). Flying such a banner may allow food writers to feel relevant, but, the second that activism leads to an abdication of their critical duties, it is the consumer who has been betrayed. This is all to say that, in your mind, Daisies will live or die on the foundations of the experience offered without any partiality as to how—at a philosophical level—they choose to execute it.

For what it’s worth, Michelin has recently struck its own balance: keeping Daisies at the Bib Gourmand level (“good quality, good value cooking”) while awarding the restaurant a Green Star on the basis of its ingredient sourcing, “dedicated fermentation program,” and “compost program.” Perhaps this is the right approach, for it allows Bibendum to praise certain environmental practices without feeling pressured to undeservingly boost readers’ perception of the concept’s service and cuisine. (It is also interesting to see Michelin categorize the restaurant, rather simply, as “Italian.”)

With so much context and subtext to keep track of, the best approach—as always—is to dive viscerally into the dining experience and see where the proverbial chips (and onion dip) fall.

You have visited Daisies “2.0” a total of four times, comprising a period from September through November of 2023. As usual, you will condense the sum of your experiences into one cohesive narrative.

With that said, let us begin.

Daisies “2.0,” you must admit, is primely positioned in a part of the city that has come to rival West Loop and Fulton Market as of late. You are not speaking about the sheer density of dining options offered, of course, but of a sneaky assemblage of superlative concepts.

Heading down Armitage, that familiar avenue, you come upon Kyōten, Kyōten Next Door, Table, Donkey, and Stick, Osteria Langhe, Gretel, Bungalow by Middle Brow, Giant, and Ørkenoy in fairly quick succession. Heading east, past Redhot Ranch, and northwest up Milwaukee the hits are a bit more scattered. There’s plenty of sushi and ramen and coffee and cocktails. However, you also find places like Beautiful Rind, Paulie Gee’s, Testaccio, Mi Tocaya Antojería, Big Kids, Longman & Eagle, Loaf Lounge, and the legendary Lula Cafe. (You might also mention Andros Taverna, though it was home to your worst meal of 2021.)

Daisies sits somewhere in the middle of it all, and this is not quite an area you would classify as a pasta desert. That being said, the restaurant’s competitors are quite differentiated: Osteria Langhe focuses on the food of Piedmont, Testaccio on Rome, Table, Donkey, and Stick on the Alps, and Lula Cafe on its own vision of farm-to-table cooking (with only two or three noodles appearing on its menu at a time).

Yes, Frillman has forged a concept that is quite unique in its devotion to pasta, offering as many as 11 or 12 preparations at a given time compared to five or six—maximum—from the most enterprising of his neighbors. And you cannot forget the vegetables. Though often prepared with an eye toward decadence, they promise a degree of healthfulness that is unique for a neighborhood where convenience often reigns. When you add in the daytime café—that “third place” with its pastries and outlets and Wi-Fi—you are left with an imposing, multifaceted concept that is not easily equaled anywhere else in the city.

Nonetheless, at ground level, Daisies looks quite welcoming. The Radler’s old home, a two-story fortress of brown brick, gray stone, and black accents, is rendered more friendly thanks to signage featuring the restaurant’s namesake flower and a neon sign that glows a deep tone of yellow out from the other side of the vestibule. These accents look especially polished when compared to the surrounding businesses on the street: a bank with an expansive parking lot, a cannabis dispensary secured behind blue grating, an unassuming ketamine clinic, a Latin grocery, a tattoo shop, a body piercing shop, another one of those “barcades,” and a longtime coffee roaster in a timeworn structure. Easy Does It, a breezy wine bar that opened in 2020, might be Daisies’s closest counterpart (at an aesthetic level) on the block. But it, too, is hidden behind a drabby façade.

This all means that Frillman’s restaurant, just barely removed from the bustle of Fullerton Avenue (and from more banks, gas stations, schools, and churches), stands as an uncommonly homey hub. It stands tall, bright, and spacious and ready to host its community (not to mention their families) in a manner that is rather unseen in this immediate area.

Stepping through Daisies’s entrance, you traverse the vestibule and open one additional door that deposits you in front of the coffee shop/pastry counter. Even under the cover of darkness, the white marbled surface, bright mosaic tiling, and light tones of wood give the impression of a sleek, modern café. You spy branded gear (hats, shirts, mugs), a fridge filled with canned La Colombe lattes, a deluxe espresso machine, some grinders, and a double-spouted coffee maker. A letterboard—white block characters on a black background—displays the various options and their pricing with a measured dose of nostalgia.

However, venturing forth from the vestibule, you have little time to dwell. The hosts manning the counter meet your eye immediately and check your name off their tablet before one of them comes, with menus in tow, to lead you to the table. While this process is rather effortless when dinner service starts, you have seen this reception area become packed with as many as a dozen people during peak hours. This is not an indictment of the staff’s ability to seat patrons but, rather, a testament to the concept’s popularity. The assembled lingerers look to be waiting for seats at the bar to open up or for their table to be cleared. They only form a minor nuisance as you later dodge their sullen frames on your way out the door.

Being led into the dining room (something that merely entails walking a couple steps to your left), you begin to get your bearings. Owing to the fact that The Radler was a beer hall, Daisies “2.0” is almost entirely made up of one single, sprawling. Down the middle, you find a double-sided banquette rendered in gray and brown tones with white structural beams and pipework interspersed. To your left, along the western wall, lie a series of C-shaped booths set against exposed brick. They seat up to five (though somewhat uncomfortably based on your observations) and come crowned with paintings (presumably by Frillman’s sister Carrie) depicting produce like carrots and peppers. The canvases do not actually hang on the wall but lean against it from the top of the booths, meaning the images become partially obscured once guests are seated.

Between the banquettes and the booths, you find the main floor with rows of three two-top tables that can be adjusted to accommodate different party sizes. On the other side of the banquette (that is, roughly straight ahead if you are standing at the café counter), you do not find the same style of seating. Instead, a solitary row of high-tops runs along the floor. This is due to the fact that, along the eastern wall, you encounter the restaurant’s bar: 11 seats positioned in front of a counter (and on top of tile) that mimics the design of the café. This area—reserved, like the high-tops, for walk-in guests—is defined by three tiers of shelving stocked with wine, liquor, and glassware. At the very center of the bar, you note a draft system with 16 taps and, above that, a photorealistic image of an orange slice cannonballing into a glass of water.

At the rear of the dining room, you find the kitchen, which is set into a bluish-gray, irregularly curved wall. A set of open windows provide a peek at all the action while, in front of the pass, you find a chef’s table with four stools. Framing the kitchen from above is a curved shelf containing artfully scattered cookbooks and other bric-a-brac. You note American Sfoglino, The Art of Fermentation, Flour + Water, Koji Alchemy, SPQR, and Wine Simple among the titles.

Should you follow the bend of the kitchen toward the dining room’s corner (straight past the bar), you encounter the bathrooms. Going further, you come upon the “pasta and pastry production room” that offers additional, “quieter” seating for dinner. This space, too, is perpetually filled and can also be observed by peering through the building’s rear windows that look out onto Fullerton.

Overall, unless you are facing the bar or the kitchen, the Daisies’s design feels a bit bare (the paintings on the western wall should really be hung). The furniture, you must also admit, is more functional than it is comfortable. However, the range of colors and materials chosen for the restaurant is undoubtedly pleasing to the eye. Lighting is well managed (bright enough to see, dark enough to feel sexy), and the place is always packed (without seeming particularly noisy). Thus, you enjoy being in the dining room even if it lacks a little charm or personality. Moreover, the space effectively transmits the surrounding community’s energy—broadening that sense of a “neighborhood place” beyond what “1.0” was capable of—in a way that privileges what diners bring to the table more than any heavy-handed flourishes.

Upon taking your seats, a busser quickly appears to provide water. (Should anyone request sparkling, you are brought an individual glass that has already been filled somewhere out of sight. In practice, you have found that you must sometimes keep requesting subsequent glasses rather than the need for a refill being anticipated—not exactly the kind of service you would typically tip 25% for.)

While waiting to be greeted by your server (something that usually only takes a couple minutes—but more on that later), you have a chance to browse the beverages. Cocktails and non-alcoholic creations now fall under the purview of beverage director Alan Bradshaw (formerly of Estela in New York City and Gwen is Los Angeles). The libations are described by the staff as “leaning on the vegetal side,” and that makes sense when you consider the restaurant utilizes “repurposed kitchen scraps to produce housemade syrups, shrubs, and infusions.”

Of the seven or eight cocktails offered on Daisies’s menu at any given time (all priced from $14-$16), you have sampled four (two of which you have tried multiple times).

The “Mushroom Margarita” (Milagro Silver, fermented mushroom, lime, carbonated) has been described by Frillman as “purposefully there to push boundaries.” This drink, you might remember, was inspired by the chef-proprietor’s experience with a “mind-blowing” mushroom cocktail at Blue Hill at Stone Barns. The “body” and “umami” of that libation caused him to ask, “what is a margarita in the Midwest?” And that led to the idea of infusing tequila with mushrooms, straining them out, pressing and fermenting the pulp, dehydrating it, and turning it into a powder used to rim the glass. (As of late, it appears this powder is no longer utilized.)

Across two visits, you have found the “Mushroom Margarita” to offer a mild degree of umami that is, indeed, interesting. However, it lacks the sharp, tangy acidity you desire from such a drink and displays only a light carbonation (that, in larger amounts, may have also made for a more uplifting sensation). You also find yourself missing a bit more sweetness or a zesty touch of triple sec. Sure, these might serve to mute the “boundary-pushing” notes of mushroom; however, in truth, the fungi’s influence is forgettable and only used to justify creating a drink that is unbalanced. It is also worth noting that Blue Hill’s mycology program (both in terms of foraging and cultivation) is far more advanced than whatever Daisies has access to. Thus, replicating one of Stone Barns’s recipes (even at the most basic conceptual level) is more easily said than done.

Of the other cocktails, the “Daiquiri Strikes Back” (three types of rum, lime, sugar, bitters) has proven much more successful across two instances. It offers a rounded, mellow take on the drink with a salted grapefruit quality that tastes like a more layered take on the Hemingway special. Well done. The “Scarpetta” (whiskey, mirto, cherry, lemon, egg white) sounds like a frothy, refreshing beverage and, in fact, does offer a mixture of jammy fruit and bright acidity. However, the blend is marred by a coarse, bitter, and somewhat vitamin-like flavor. Lastly, the “Sleeping Dragon” (mezcal, clairin, peppers, lime, Sicilian oregano) draws (like the margarita) upon flavors of fresh produce. However, in this case, the peppers are incorporated decently with the smoky flavors of agave, with a certain savory quality and notes of spice providing additional complexity. This has been your second favorite of the bunch (though not something you would necessarily order again).

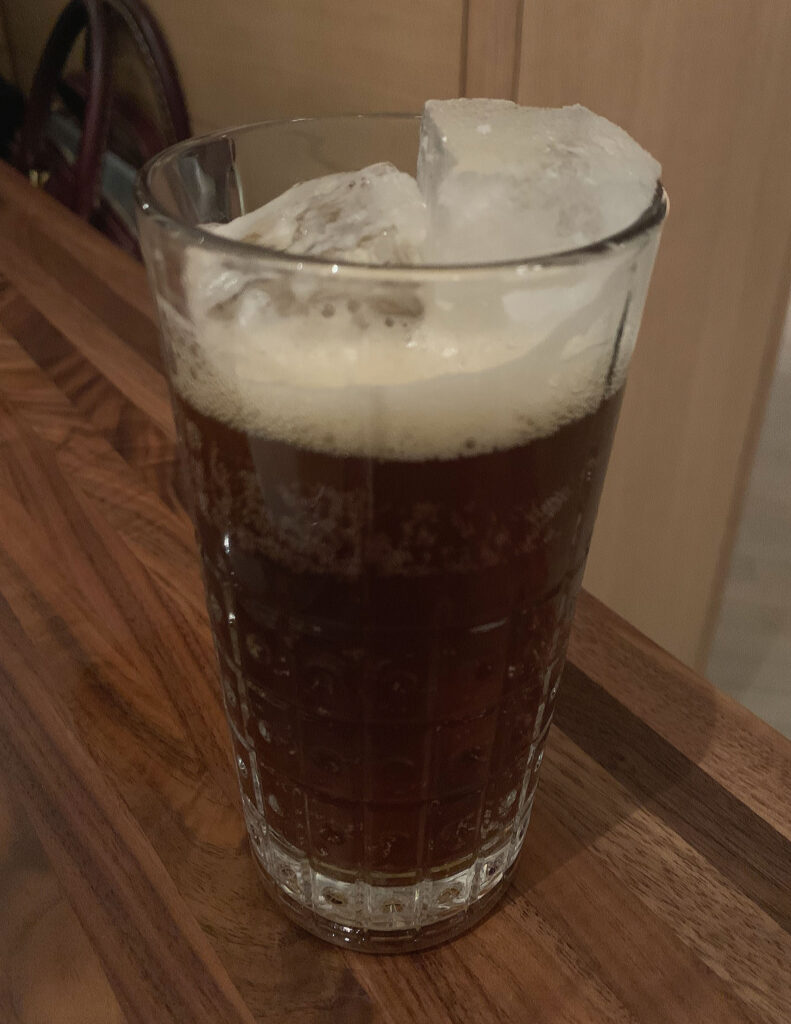

In contrast, you have found that Daisies’s non-alcoholic options far surpass what the bar is doing with a liquor. A “Seasonal Kombucha” ($6), inspired by applejack brandy (and flavored with green apple and chamomile), displays a brilliant roundness and depth of sweet fruit flavor balanced by a tart, fizzy finish. Meanwhile, a housemade “Root Beer” ($6) is a stunning example of the form that strikes you with its complex, caramel/malty/sassafras character but no trace of sticky, sickly excess. You would very happily order either of these again.

Alongside the cocktails and non-alcoholic offerings, you find nearly a dozen beers in varying styles from local producers (like Is/Was, Lagunitas, Maplewood, Marz, Moody Tongue, Penrose, and Pipeworks) alongside a solitary cider. Also, on this page (opposite the food), are listed the wines by the glass. As it happens, wine director Katherine Sturgill left Daisies just before the first of your visits. She has yet to be formally succeeded in that role (one that also involves doubling as a general manager), so it is best to view the program as still principally reflecting her influence.

As stated on the introduction page that once preceded the bottle list, Sturgill’s focus was on “both Italian and domestic wines made from environmentally and socially responsible wineries, many of which are small and family-owned.” Additionally, each selection was made due to its “unique beauty” and “flavors that are complimentary [sic]” to the “dinner menu.”

Over the course of your meals, the by-the-glass selection has included:

Sparkling

- NV Borgoluce “Lampo” Prosecco di Treviso Brut ($14)

- 2019 Illinois Sparkling Co. “Ombre” Rosé Illinois ($14)

- 2021 Carafoli “La Divina” Lambrusco di Sorbara ($12)

White Wines

- 2021 Marco de Bartoli “Vignaverde” Terre Siciliane [100% Grillo] ($16)

- 2022 La Marea “Kristy Vineyard” Albariño Monterey County ($18)

- 2020 Colterenzio Pinot Grigio Alto-Adige ($14)

- 2021 Sfera “Bianco” Colli Orientali del Friuli [100% Ribolla Gialla] ($15)

- 2021 Sandhi Chardonnay Central Coast ($15)

- 2021 Brea Wine Co. Chardonnay Santa Lucia Highlands ($15)

- 2022 Cantine Barbera “Tivitti” Mefi [100% Inzolia] ($12)

Orange/Rosé

- 2022 Modales “Contact” Fennville [Rkatsiteli/Pinot Blanc] ($13)

- 2021 Mari Vineyards “Bestiary Ramato” Pinot Grigio Old Mission Peninsula ($16)

- 2021 Forlorn Hope Rosé California ($15)

- 2021 Day Wines “Babycheeks” Rosé Rogue Valley ($14)

- 2021 Nicosia “Lenza di Munti” Etna Rosato ($15)

Red Wines

- 2020 Portelli Vittoria Frappato ($14)

- 2022 Martha Stoumen “Post Flirtation” California [Zinfandel blend] ($19)

- 2021 Presqu’ile Pinot Noir Santa Barbara County ($15)

- 2019 G.D. Vajra “Able” Barolo [Coravin] ($30)

- 2022 Paolo Scavino Barbera d’Alba ($15)

- 2022 Jolie Laide “Glou d’Etat” California [38% Valdiguié/33% Mourvèdre/17% Grenache] ($16)

- 2022 Stolpman “La Cuadrilla” Ballard Canyon [60% Syrah/30% Grenache] ($16)

- 2019 Movia Cabernet Sauvignon Goriška Brda ($15)

Immediately, you must note that Daisies “2.0” has seen the wine program, formerly focused solely on domestic bottles (with a value-driven, “natural” bent), expand to include Italian offerings. This is a smart strategy, for the restaurant now likely has more cellar space to work with and can draw on many more options to choose from when filling it. You also think the wines of Italy form an interesting complement to Frillman’s food, revealing how classic pairings morph in accordance with his decidedly Midwestern take on the country’s recipes and forms. Fermented grape juice, in this manner, forms a lens through which the nuances of culture and flavor are better understood: how do the products of different (yet spiritually connected) terroirs compare and contrast?

To that point, it is nice to see bottles from Illinois and Michigan featured by the glass. While the latter state is represented by two esoteric orange wines, the former represents an attractive value in the popular sparkling category. This means, courtesy of the Illinois Sparkling Co., diners get the rare thrill of drinking wine made in their own state.

Elsewhere, you appreciate that the by-the-glass selection stays mostly within the $12-$16 range (something that accords with Daisies’s peers), with an $18 domestic Albariño, a $19 Zinfandel blend, and a worthwhile $30 Barolo being the exceptions. Further, while the popular Sauvignon Blanc variety is missing, the options run the gamut from Pinot Grigio, Chardonnay, and California rosé, to Pinot Noir, Rhône-style blends, and Cabernet Sauvignon.

While two of the Italian white wines featured, made from the Grillo and Inzolia grapes, are fairly obscure, they may help to prompt a conversation with the staff regarding their characteristics. Otherwise, the Prosecco, Lambrusco, Ribolla Gialla, Etna Rosato, Frappato, Barbera, and aforementioned Barolo are all representative and approachable. Otherwise, when it comes to domestic, the Sandhi Chardonnay, Martha Stoumen “Post Flirtation,” Presqu’ile Pinot Noir, Jolie Laide “Glou d’Etat,” and Stolpman “La Cuadrilla” comprise some of the best values available in the country. These are vibrant, drinkable, largely “natural” (though not in the polarizing way) wines you would be more than happy to have in your glass. Overall, this is a very smart by-the-glass assortment from Sturgill.

However, as always, it is the bottle list that really catches your attention. The following are representative selections drawn from the period of your visits:

Sparkling

- 2022 Illinois Sparkling Co. “Illnatic” Extra Brut Rosé Illinois ($50)

- Mari Vineyards “Simplicissimus” Michigan ($58)

- NV Ca’ Del Bosco “Cuvée Prestige” Franciacorta ($95)

- NV Fergettina Franciacorta Brut Rosé ($100)

White

- 2021 Alois Lageder Pinot Grigio Alto-Adige [375mL] ($25)

- 2021 Hermann J. Wiemer Riesling Seneca Lake ($52)

- 2021 Marland Sauvignon Blanc & Sémillon Lake Michigan Shore ($52)

- 2021 Brooks Riesling Willamette Valley ($56)

- 2020 Lieu Dit Chenin Blanc Santa Ynez Valley ($58)

- 2021 Elena Walch “Castel Ringberg” Sauvignon Blanc Alto-Adige ($68)

- 2021 Benanti Etna Bianco ($74)

- 2021 Venica & Venica “Ronco del Cerò” Sauvignon Blanc Collio ($75)

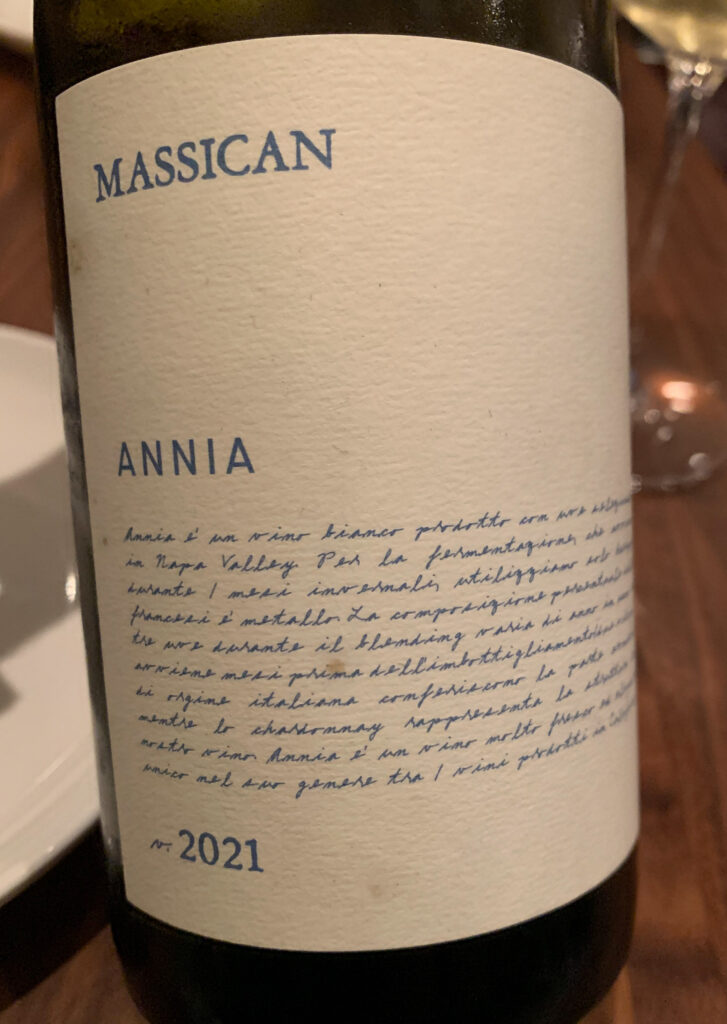

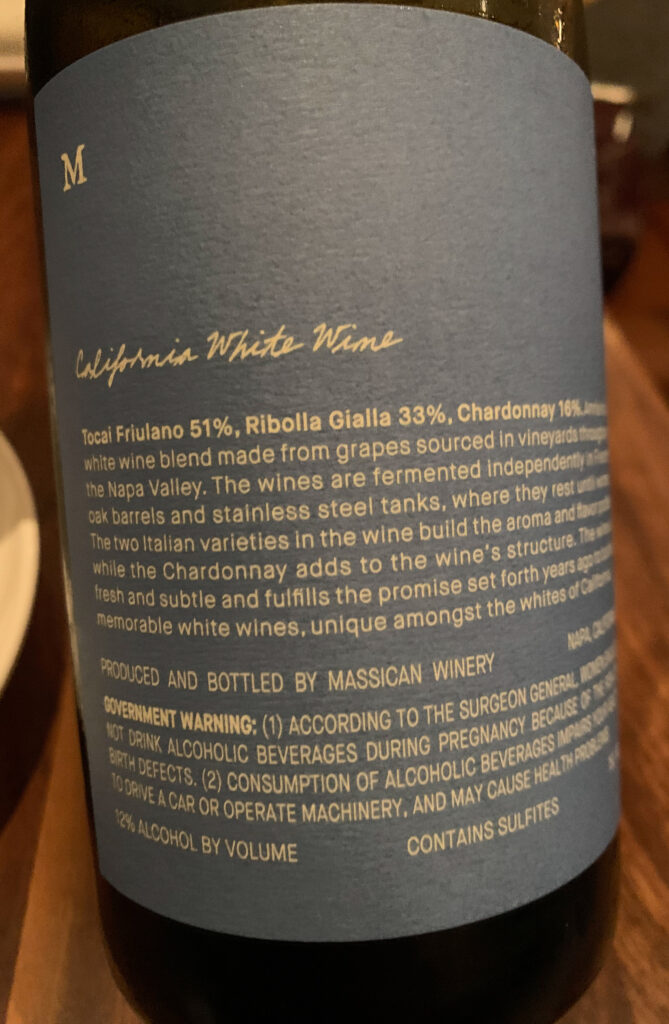

- 2021 Massican “Annia” Napa Valley [51% Tocai Friulano/33% Ribolla Gialla/16% Chardonnay] ($89)

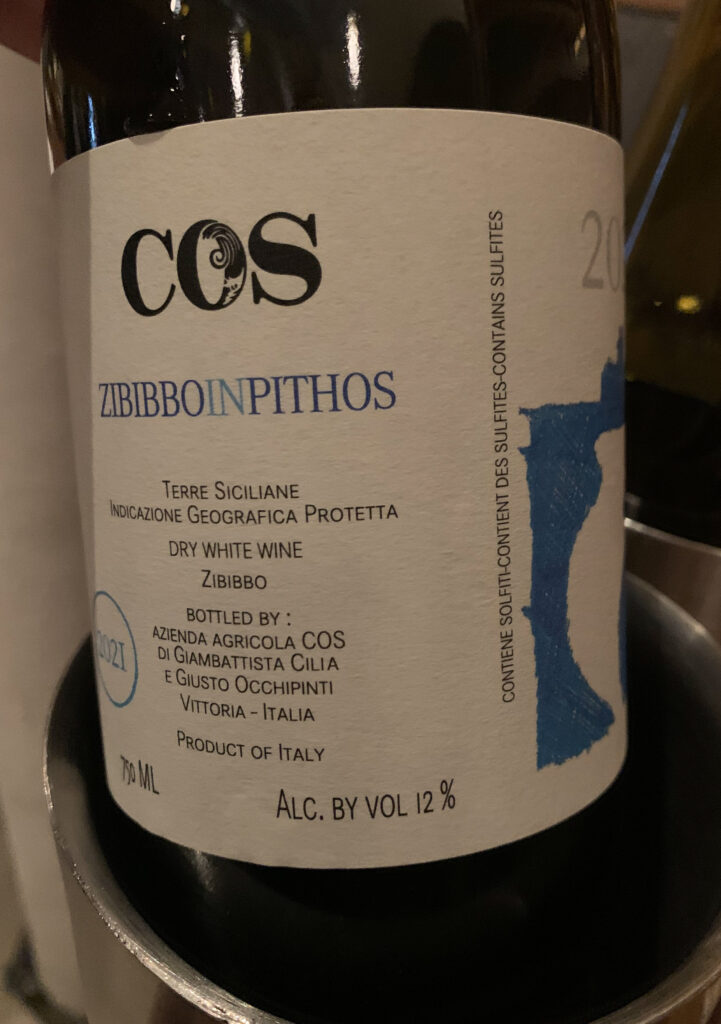

- 2021 COS “Zibibbo in Pithos” Terre Siciliane ($100)

- 2021 Matthiasson “Linda Vista Vineyard” Chardonnay Napa Valley ($105)

Orange

- 2021 Union Sacré “l’Orangerie” Arroyo Seco ($57)

- 2021 Ca’ del Prete “Bianco a Metà” Piemonte ($65)

- 2017 Maradei “Danfora” Calabria ($74)

Rosé

- 2021 Sergio Drago “Rosa” Terre Siciliane ($54)

- 2022 A Tribute to Grace Rosé of Grenache ($65)

Red

- 2021 G.D. Vajra Langhe Nebbiolo ($46)

- 2019 Tomassi Ripasso della Valpolicella Superiore ($58)

- 2021 Bow & Arrow Gamay Willamette Valley ($62)

- 2020 Guido Porro “Camilu” Langhe Nebbiolo ($68)

- 2021 Tenute Silvio Nardi Rosso di Montalcino ($68)

- 2021 Railsback Frères “Cuvée Spéciale Le Carignan” Santa Ynez Valley ($70)

- 2016 Westrey Pinot Noir Willamette Valley ($70)

- 2021 Podere Grattamacco Bolgheri Rosso ($72)

- 2019 Frog’s Leap Cabernet Sauvignon Napa Valley [375mL] ($78)

- 2018 Felsina “Berardenga” Chinati Classico ($85)

- 2021 Lo-Fi Pinot Noir/Trousseau Santa Barbara County ($92)

- 2017 Rhys “Alesia” Pinot Noir Santa Cruz Mountains ($92)

- 2016 Monte Zovo Amarone della Valpolicella ($95)

- 2018 Produttori del Barbaresco Barbaresco ($115)

- 2018 Andrea Oberto Barolo ($120)

- 2018 Miner Family Vineyards “Emily’s” Cabernet Sauvignon Napa Valley ($120)

- 2019 Piedrasassi “Rim Rock” Syrah Arroyo Grande Valley ($120)

- 2019 Figgins “Figlia” Walla Walla Valley [Merlot/Petit Verdot] ($150)

- 2015 Nicolas-Jay Pinot Noir Willamette Valley ($150)

- 2016 Prà “Morandina” Amarone della Valpolicella ($170)

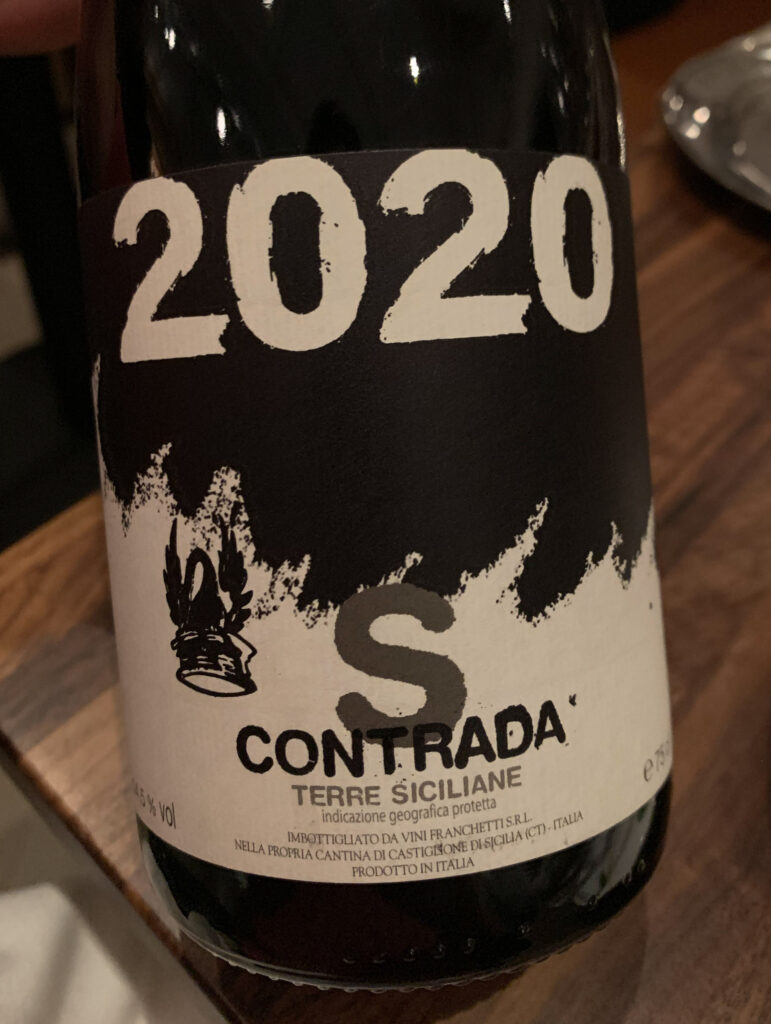

- 2019 Passopisciaro “Contrada G” Terre Siciliane ($180)

- 2017 Sassetti Brunello di Montalcino ($190)

- 2016 Sesti Brunello di Montalcino ($230)

- 2017 Paolo Bea “Pagliaro” Sagrantino di Montefalco ($260)

This list is certainly a far cry from the $39 or $59 format Daisies “1.0” maintained at launch, and that is not a bad thing. There is still quite a range of options under $60, with some like the Brooks Riesling, Lieu Dit Chenin Blanc, and G.D. Vajra Langhe Nebbiolo being quite nice. Likewise, the majority of bottles still land under $100, with wines like the Benanti Etna Bianco, Venica & Venica Sauvignon Blanc, Massican “Annia,” Lo-Fi Pinot Noir/Trousseau, and Rhys “Alesia” all being well worth the money.

North of $100, you find some appealing choices: the COS “Zibibbo in Pithos,” Matthiasson “Linda Vista Vineyard,” Produttori del Barbaresco, Piedrasassi “Rim Rock,” Figgins “Figlia,” and Nicolas-Jay Pinot Noir. However, of the very most expensive options, you think only the Passopisciaro really makes sense. For, while the two Brunellos may be at the threshold of being drinkable (with some decanting), the Amarone and Sagrantino are particularly burly styles of wine that demand extended aging. They also, quite frankly, display a level of concentration that you are not sure matches Frillman’s food—which, over the course of your visits, offered a “Grilled ½ Chicken” and “Pork Collar” as its most substantial entrées.

Surely, you think fans of the (relatively more affordable) Cabernet Sauvignon-, Grenache-, and Syrah-, and Zinfandel-based wines on offer may not particularly care about some theoretical pairing so long as they can drink what they like. However, Amarone and Sagrantino are niche categories, and you think the list’s most expensive bottles should be sparkling, white, aged reds, or entry-level reds from top producers. These would represent more sensible splurges for those looking to drink the restaurant’s best.

Otherwise, you must praise Sturgill’s continued work in showcasing wines from Illinois, Michigan, and New York alongside more popular regions like California and Oregon. You think Daisies’s corkage policy ($15 per 750mL, $30 per magnum with no bottle limit that you know of) is also quite fair. Additionally, diners benefit from annotations being provided for all the wines in the full list (this includes the by-the-glass options but not, due to space limitations, on the backside of the dinner menu). Savvily, the restaurant had adopted the best practice of using two or three descriptors for each selection: like “rich, lychee, orange blossom” or “black pepper, savory smoked meats, plum.”

In terms of value, Daisies’s markups range from 70%-150% on top of retail pricing:

- 2021 G.D. Vajra Langhe Nebbiolo ($46 on the list; $26 Wine-Searcher average)

- 2021 Brooks Riesling Willamette Valley ($56 on the list, $24 from the winery)

- 2021 Benanti Etna Bianco ($74 on the list; $33.99 at national retail)

- 2017 Rhys “Alesia” Pinot Noir Santa Cruz Mountains ($92 on the list; $49 from the winery)

- NV Ca’ Del Bosco “Cuvée Prestige” Franciacorta ($95 on the list; $42.99 at national retail)

- 2018 Produttori del Barbaresco Barbaresco ($115 on the list; $48.99 at local retail)

- 2019 Piedrasassi “Rim Rock” Syrah Arroyo Grande Valley ($120 on the list; $55 from the winery)

- 2019 Figgins “Figlia” Walla Walla Valley [Merlot/Petit Verdot] ($150 on the list; $59.99 at local retail)

- 2017 Sassetti Brunello di Montalcino ($190 on the list; $79.99 at national retail)

- 2017 Paolo Bea “Pagliaro” Sagrantino di Montefalco ($260 on the list; $119.99 at national retail)