Despite standing as one of Chicago’s finest restaurants for nearly six years, Oriole has thus far failed to arouse that familiar compulsion to submerge yourself in some in-depth study of the restaurant. That is no slight, for plenty of superlative establishments resist your analysis by virtue of their ironclad quality.

For example:

- You have long cherished Elizabeth and, after tasting Ian Jones’s first menu as executive chef, think the concept is poised to enter its most exciting era yet. The wine program, now under the care of sommelier Ali Martin, remains eccentric but, often, astounding.

- Elske, having emerged from its pandemic slumber, has immediately reasserted itself as possessing one of the city’s most technically adept kitchens. Its menus challenge and please guests’ palates in equal measure while the wine list remains one of the most thoughtfully curated in town.

- Goosefoot, after more than a decade, still offers the most earnest, charming devotion to its customers. Chris and Nina Nugent preserve one of Chicago’s last havens of classically inflected fine dining, crafting dishes of intensity that reward your best BYOB selections.

- Topolobampo, as you have written before, serves as a shining example of just how good a “celebrity chef” restaurateur can really be. The institution houses some of the best hospitality professionals you have ever met along with a mouthwatering cellar. Its tasting menus, season after season and year after year, shine with their creativity and quality.

You cannot imagine Chicago without these restaurants, but what can you say that hasn’t already graced the pages of the Tribune, the wannabee “reviews” of Yelp, or the annals of Instagram? Digging through your archive, what story would years of photos of years of menus really tell? Yes, the tale may be one of growth and change; however, it would be moderated by years of consistent quality within a well-distinguished style. Your own extended enjoyment of the concepts would amount to little more than a heaping of praise bound to be drowned out by the larger sea of hyperbole that characterizes contemporary restaurant criticism.

Compare that to writing about Alinea, Ever, Smyth, or Kyōten, places that do not only share a high degree of dynamism, but some essential element of mystery as to what exactly will be served on a given evening. Any attempt to define such a restaurant, whether on the basis of one, ten, fifty, or one hundred visits, is a fool’s errand. For any snapshot, however high in definition, will be woefully out of date by the time some dear reader finds themself dining there.

Nonetheless, with enough time and care, you might unravel some larger stylistic pattern—some cohesive current of thought—that shapes the guest experience in perpetuity. That key, if you do your job well, may unlock a deeper appreciation for the establishment whether the reader is an experienced or amateur gastronome. In other cases, calling attention to a lack of cohesion or intention across multiple visits assuages first-time diners who feel they didn’t “get it” but lack confidence in their sense of taste. No matter the case, digging more deeply into such a restaurant’s identity as it is sensed (and not simply marketed) empowers consumers to better match themselves to their ideal meal. By penetrating the luxury branding paradigm (but retaining some sense of the “magic”), you work to ensure the aspiring fine diner’s first high-priced tasting menu is not doomed to be their last.

Writing about Italian concepts, for example, inverts that same logic. Crowded genres filled with myriad chefs wielding the same (or similar, price-stratified) ingredients might seemingly offer less room for in-depth criticism. Faux-journalistic content creators, surely, are more than happy to tout one example of the form after another so long as they keep the clicks coming. But these many variations of the same theme, should you apply some overarching critical framework, can actually provide a window into the essence of their chosen cuisine. Out from the morass of similarity shines exceptional technique, creative interpretation, and unerring consistency. Thus, once more, your dear reader can intelligently decide which business to patronize, and the most thoughtful concepts (rather than those with the most money to burn on marketing) are given some greater chance to succeed.

Yes, it is in the middle ground between the misunderstood, Michelin-caliber restaurants and the shiny new entrants into crowd-pleasing genres that you struggle. At best, writing about stalwarts like Blackbird or Everest a couple years ago would have meant emphasizing the sustained quality of a Chicago institution. At worst, it might have meant pushing the concepts towards an even earlier grave.

Now, bittersweetly, you regret not championing Ryan Pfeiffer’s extended tasting menus at Blackbird during their time. For you met far too many “bucket list” diners who visited the restaurant for an affordable “Michelin-starred” lunch, left underwhelmed, and never bothered to pay the cuisine a second look. Blinded by the most superficial prestige and a flawed desire to “catch ‘em all,” so to speak, this population completely missed the fact that Pfeiffer was crafting some of the city’s most eccentric, delicious food after dark. Had the cuisine been transferred to new digs and pursued without any lingering responsibility to please Blackbird’s longstanding prix fixe and à la carte crowd, the chef easily would have merited two Michelin stars.

On the other hand, Jean Joho’s temple of Alsatian cuisine had little chance of snaring the next generation of “foodies.” What was once the shining crown jewel of the LEYE empire had faded, with the democratization of fine dining, into a plastic-wrapped throwback from grandma’s house. The stature of—and nostalgia for—one of Chicago’s O.G. celebrity chefs was doomed to dwindle as generations passed and tastes shifted. But, over more than three decades of operation, Everest never betrayed its identity. Until the end, it formed a benchmark of refinement and an ode to the harmony between wine and food. During your final few visits to the restaurant, there were hardly any other parties in the dining room. Joho, nonetheless, made his appearance. The chef laughed, flattered, and toasted with guests. He made each table feel special through the glowing warmth of an undying pride in his establishment. Chicago’s subsequent generation of professionals would do well to remember whose shoes they are filling.

This is all to say, it’s hard to know the stakes of choosing this or that place to feature until it’s too late. By untethering yourself from the demands of the clickbait news cycle, you can better resist the flagrantly unprofessional conceit of reviewing a restaurant on the basis of a solitary visit. No critic’s perception is that blessed (to say nothing of latent biases that can only be controlled for by way of repeat experiences).

Instead, you only write about places that grab you for some reason or another. Oriole, despite paying something like a dozen visits to the restaurant before its renovation, never fit that bill. During that time, you made many fond memories and ate plenty of delicious food. But you did not feel like there was anything to uncover by way of further analysis. Its excellence was apparent and widely appreciated. The menu always sought to please, and, thus, saw fewer changes and less of a constant creative process to note at your level of detail. Yet dining at Oriole guaranteed, time and again, a great experience for just about anybody. You held the restaurant in high esteem but never felt it possessed that extra entropic dimension in which to sink your critical teeth.

Much of that has to do with the novelty effect. Oriole’s dishes were always expertly engineered but doomed to fade with repeat exposure. However, the vast majority of diners would taste them with the full force of their first, glorious visit. Any cracks that began to show on account of your familiarity with the compositions would likely read as nitpicking. And the prospect of criticizing Oriole for maintaining a consistent array of “perfected,” highly pleasing dishes from month to month never sat well with you. Chicago is not so blessed that you can penalize a chef who looks to guarantee you’ll receive his best ever work—rather than the fruits of an uncertain (if highly engaging) process—on any given evening.

Why pick apart the same courses that certainly blew you away the first time? Why labor to condense a wide array of experiences that impressed you most with their reliability? Bavette’s and Elina’s certainly excel on the basis of their consistency, but tasting menus are a creative enterprise. Oriole has always been one of Chicago’s very best restaurants, but there was nothing a fifth, sixth, or seventh visit revealed that was not apparent from your second trip.

In truth, as you look back across five menus from 2018 (January, April, June, August, November) and six from 2019 (January, May, June, August, September, November), the tweaks to the meal are impossible to ignore. Squab replaced Berkshire pork, Hokkaido replaced Santa Barbara uni, Malpeque replaced Beausoleil oyster, black bass replaced loup de mer, seabream replaced Spanish mackerel, halibut replaced black bass, sablefish replaced halibut, and langoustine, lobster, prawn, and king crab all played musical chairs from month to month. This is admittedly a bit reductive, yes, and it reduces Oriole down to its headlining ingredients rather than each dish’s constituent parts.

It should also be noted that the restaurant’s A5 wagyu, an absolute mainstay of the menu, has been paired with golden cordyceps, lemon thyme, and beef reduction; chestnut royale, lemon thyme, and dried matsutake reduction; grilled little gem, shiso, and puffed rice; cobalt carrot, furikake, and seaweed hollandaise; Nichol’s Farm asparagus, porcini, and Madeira; chanterelle, little gem, and Madeira; as well as beech mushroom, cipollini, and bone marrow butterscotch, just to name a handful of accompaniments.

Noah Sandoval’s cooking was as close to a guarantee as Chicagoans could get. He wielded totemic luxury ingredients expertly and thoughtfully, clarifying just why aspiring fine diners should pay a premium for such things. In doing so, the chef drew on a dependable cast of characters like green garlic, brown butter, black walnut, yeast, koji butter, king crab emulsion, lemongrass sabayon, prawn head caramel, parmesan rind, langoustine caramel, smoked soy, truffle honey, braised ramp, and beurre monté to make his plates sing. They might be complemented by other elements like sea grape, borage, ras el hanout, shio kombu, masago arare, ice plant, amazake, Argumato olive oil, Belper Knolle cheese, and Urfa Biber pepper that you, personally, had little familiarity with until served to you at Oriole.

You do not mean to cast Sandoval’s cooking as particularly modular. It was seasonal without being as hyper-seasonal as, say, Smyth or Kyōten. The techniques were refined and surprising without going off the deep end like Alinea (or Ever). As best as you could describe it, Oriole served worldly, luxurious fare with just enough restraint to ensure everyone went home happy. By tempering experimentation (or, perhaps, keeping that process behind the scenes until a new dish could make its full debut), the restaurant batted a higher average than any other tasting menu in town. In exchange, Oriole struck upon those true “home run” dishes a bit less often than Kyōten or Smyth, whose devotion to process yielded higher highs and lower lows.

Thus, when you consider the peak-end rule, it is easy to understand why Oriole failed to arouse your critical interest. On each subsequent visit, the peak of the previous meal would, due to the novelty effect, seem a little less towering. It would then be up to one or two new dishes to scale the heights of everything that came before (a tall order given the quality of Sandoval’s classic, enduring creations). Lacking that, the experience would amount to a very good meal but not the sort you felt the urge to highlight. There was no ill-gotten hype to puncture nor any particularly captivating push-pull of stylistic development to note. Oriole’s identity was open-ended enough to scuttle any easy sort of definition, so you resolved to simply enjoy your time there.

Oriole took its time reopening after Chicago first halted indoor dining during the spring of 2020. The restaurant finally welcomed guests, once more, in late September of that year only to close its doors on account of a second shutdown less than a month later. It seemed to be a staggering blow to an establishment that had done everything right. However, in one of the great gastronomic silver linings of the entire pandemic, Oriole charged forward with an expansion and renovation.

The restaurant reopened, once more, in July of 2021 with all the promise of a new experience in an improved space. Though already ensconced among Chicago’s most elite chefs, Sandoval chose to pursue—and fulfill—a grander expression of his vision. The chef unveiled Oriole “2.0,” and you think that moment provides the perfect opportunity to finally engage more deeply with his work.

This development does not only offer the occasion to note the concept’s growth from “1.0” to “2.0,” but to consider the restaurant—six years on and with a shiny new coat of paint—as something of an institution. You think Oriole is destined to be only the fourth Chicago restaurant to earn three Michelin stars. It will, rightfully, represent the city on a national and international level, and that seems like fertile ground for some deeper analysis.

You have visited Oriole “2.0” nine times since its reopening in 2021, spanning a period of seven months. As is typical, you will condense the sum of your experiences into once cohesive narrative.

Let us begin.

The eastmost block of Walnut Street looks like little more than a glorified alleyway. The loading dock, dumpsters, and ever-present parked cars certainly hammer that impression home. Walnut does not lead anywhere either. It jumps over the highway, encircles a storage facility, and then disappears for nine blocks (rearing its head again just west of Union Park). This phantom street, tucked across from one of West Loop’s ugliest, Brutalist buildings (215 N. Des Plaines) and a corner auto repair shop, could hardly be home to one of Chicago’s most luxurious dining experiences. But that is so much of Oriole’s charm.

The restaurant sits at the threshold of Fulton Market and Randolph Restaurant Row while resisting inclusion into either sprawl. Yes, Mako sits just on the other side of the expressway. Grace, once upon a time, could be found a block and a half south. But Oriole forms its own outpost on its own quiet street that seems worlds away from the hubbub of Chicago’s famed dining corridors.

Kumiko, the restaurant’s associated Japanese dining bar (and, by your measure, the best drinking establishment in the city), enlivened the area a bit more when it opened on New Year’s Eve of 2018. The veritable Moneygun, located just on the other side of Oriole’s building, has been pleasing patrons since it opened contemporaneously with the restaurant in March of 2016. Yet, facing Lake Street, the bars still feel like part of the urban bustle.

Turning onto Walnut, whether you come from Des Plaines or pass by the pumping station on Union Avenue, gives you tunnel vision. The city—as you comprehend it during your day to day life—recedes into the background. The Jewel-Osco from which you buy your weekly groceries and the Kinzie Cleaners where you drop off your wine-stained shirts seem miles away. They stand apart in some workaday world that ceases to exist as you saunter down that street. Catwalks—and the occasional set of headlights—guide you deeper down the way. The glow of the projector out from some adjacent warehouse space prompts a moment of pause.

There’s no restaurant here, you think, but a lone streetlamp beckons you a bit further. Just before you reach the trees and all the commotion of I-90, a clearing appears. A fence of smooth, dark wood surrounds an outdoor sitting area. The material contrasts with the weathered brick and rusted metal that lined your path there. Onto that outer barrier is affixed a gleaming metal placard: “o r i o l e (661 W. WALNUT ST.).”

The understated font could not be more apropos. For the restaurant does not blanket social media with posts promising “an experience of a lifetime,” but retains an all-essential mystique. Expectations, despite years of exemplary testimonials, are brilliantly managed. Guests are left dangling until the very moment they enter Oriole’s world. They’re put on the back foot—pricked with just a wee bit of skepticism—so that the full breadth of the restaurant’s experience can stagger them.

Such a feeling strikes once you enter Alinea, but the valet parking posted outside dilutes the effect. Ever, too, despite having crafted a captivating environment, sits at the ground floor of a hulking new development. Smyth does a better job of hiding in plain sight, juxtaposing the warmth of its hospitality with the congestion of Ada Street. And Kyōten, now more than ever, forms an oasis that stands apart from the screeching trains (and excellent burgers) that characterize its stretch of Armitage. But Oriole does it best.

You climb a few steps and finally enter the restaurant proper. The front door, so to speak, has gone from being north-facing (towards Walnut) to west-facing (towards Union). Its positioning, from Oriole “1.0” to “2.0,” differs only by a few feet, yet it completely transforms how you perceive the space’s orientation.

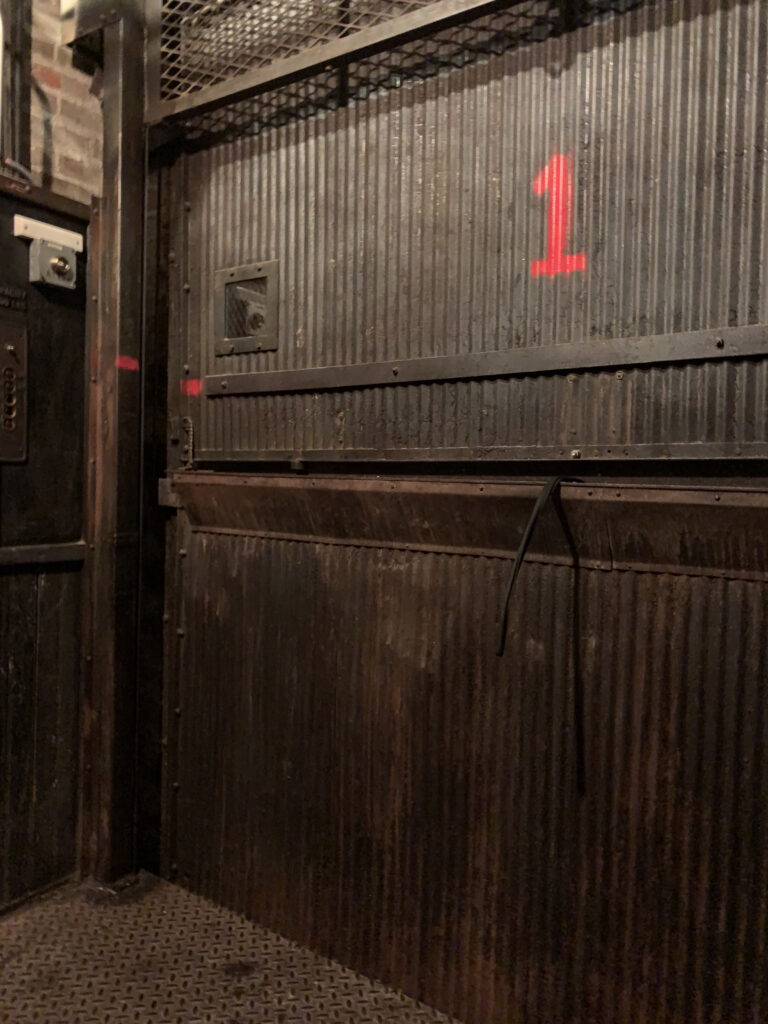

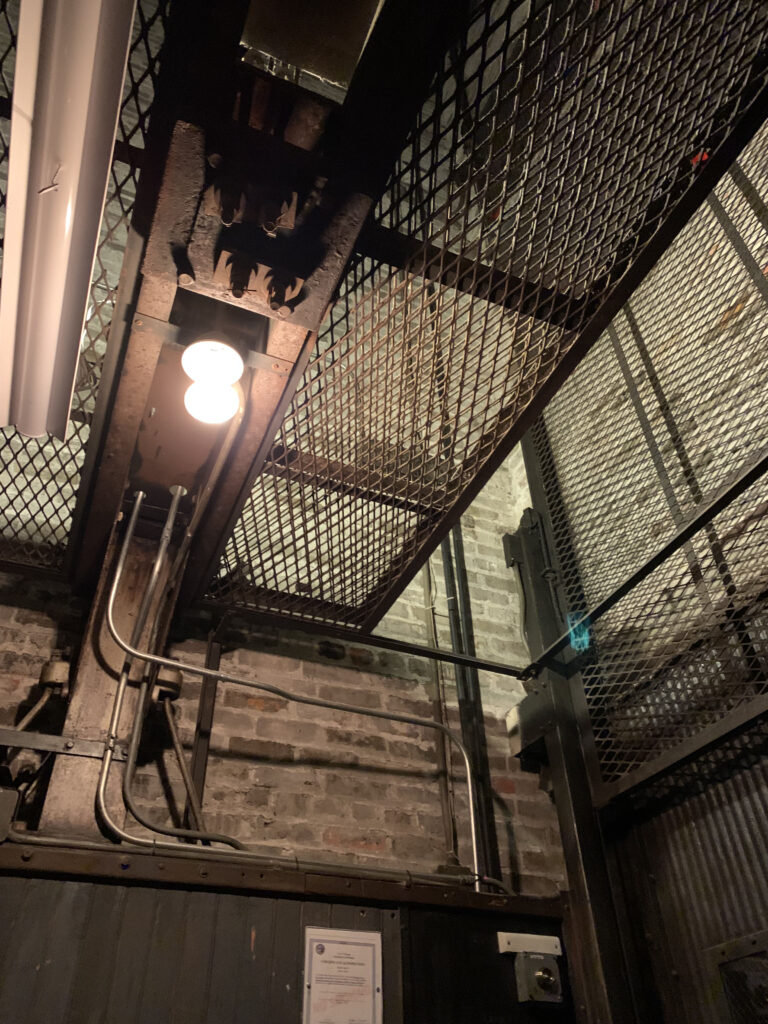

Stepping inside, you find yourself in a shadowy, industrial chamber. The well-appointed outdoor space and its signage might have confirmed your arrival, but it feels as though you’re back in the alley. This isn’t the “Starship Enterprise” of fine dining. No sign of TURF Design, stone, glass, or $6,000 PPE holder here. Oriole signals that you’ve found the right place only to cast you back into the darkness. What do corrugated and diamond plate metals, faded bricks, floor lanterns, rusted radiators, and exposed piping have to do with luxury? Where does that freight elevator, with its emergency intercom and myriad buttons, lead?

It all seems a bit Tower of Terror, but you’re not given the chance to linger over it. The host meets your eye immediately. They man a handsome stand straight across from the entrance while the freight elevator and its mystery sit off to the side. You are relieved of your belongings and offered a tea—hot or cold depending on the time of year—made from herbs and flowers grown on-site in that outdoor space. The host instructs the party to wait just a moment. You step onto the elevator, which buckles ever so slightly, and take a seat on the bench that lines its wall. The delay spans less than a minute. You’re back up on your feet in just the time it takes to slurp down the cuppa tea. The host hops into the elevator and moves towards its buttons. You brace yourself for a sudden drop, but they instead tug at a dangling strap and pull the rear door open with one sweeping movement.

Like the lids of an eye, the top and bottom sections part to reveal Oriole’s glory—though, at first, just a glimpse. The photo of a rabbit that had adorned one wall of “1.0’s” dining room greets you head-on, as does your captain. A wall now separates you from the original space, and they guide you to the side. The harsh materials of the alley outside give way to shining wood and clean, neutral-toned wallpaper. You pass by a new wine cellar accented by a small painting but dominated by floor to ceiling racks that span the circumference of the room. DRC, Roumier, and Hundred Acre labels wink at you.

A couple of steps lead you up and into the restaurant’s new bar area. Leather seats, plush couches, shining metal planters, and patterned rugs are offset by concrete floors and the familiar, worn brick that characterized the block. Paintings, one of which is inlaid beautifully into the wall, are formed of white canvas that has been marked with wild, curved brushstrokes in black or red. Sections here and there are plastered over with a white coating that fades the color but preserves the sense of movement from top to bottom of each piece. The slapdash nature of the paintings calls to mind graffiti. They underscore Oriole’s liminal status somewhere between urban decay and the height of luxury. It all amounts, from the moment you set foot onto Walnut until you cozy up to the bar, to an unmistakable sense of place.

The design confidently shifts guests’ focus onto the substance of the experience—the warmth of hospitality and pleasure derived from the food and drink—rather than contrived abstraction and fancy baubles. Oriole did, indeed, contract “a strategy and design consultancy for those who use food as a beacon for community and change” to “refresh and expand their visual identity.” Nauseating language aside, you admire the renovation’s relatively light touch. The space has been further realized with respect to its latent character. It stands within—not apart from—its larger neighborhood setting while achieving a unique sense of refinement.

Past the bar lies a private dining room with curtains, white tablecloth, rug, planters, paintings, candlesticks, and a sleek fireplace as its focal point. Still, the brick walls and muntin bars on the factory-style windows prevent it from feeling too precious.

Between the private dining room and the threshold of the kitchen lies a hallway with several single-occupancy bathrooms. You rarely discuss restaurant washrooms, save for the whimsical wallpaper and enchanting menus hung at Smyth or the sonorous tones of Matthew McConaughey that play at Ever. But Oriole’s are both calming and well-stocked with any type of toiletry a stained, sick, or otherwise embarrassed guest might need to return to the table feeling at ease. In that sense, they form a fitting backstage area that anticipates diners’ needs and empowers a wholehearted enjoyment of the meal even under adverse conditions.

You mention the bathrooms, too, because you conducted a little test. It’s uncharacteristic of you to do so and, in some way, feels a bit unfair. But, you think, it is better that you test the limits of a local establishment’s attention to detail than leave it up to some national or international critic for whom the stakes are much higher. For it affirms that Chicagoans’ own discernment is of the utmost caliber, and it guards the city’s shining lights against attacks made in bad faith from those predisposed to denigrating the city’s dining scene.

It is written in gastronomic lore that certain critics, during the course of their duties, test the attentiveness of a restaurant’s staff by placing some marker on the floor early on in the meal and seeing if it gets removed in due time. Dropping a utensil or napkin on the floor of a fine dining restaurant, in today’s day and age, surely provokes an immediate response. A cork, perhaps, could be deposited subtly enough. Yet, on occasions that the staff has noticed you holding onto such keepsakes, they have kindly offered to hold onto them until your departure.

Typically, the tougher test will occur further away from the action. Naturally, a fine dining establishment will have plenty of eyes on guests within the dining room, but it is constantly resetting those backstage areas that forces the staff to prove their mettle. The feeling of luxury conjured across a grand space must ring true within the intimate confines of a washroom, where every element is open to minute inspection. Obviously, an overlooked bathroom holds massive potential to trigger a disgust reaction that can poison any enjoyment of the meal. Bitterly, this can be held against the restaurant even if the blame, in truth, lies with some other, uncivilized diners. However, it’s just this kind of rigorous crisis aversion that characterizes the perfected hospitality of the finest institutions.

So, classically, the best way to judge this capacity is to toss a hand towel somewhere on the floor of one of the bathrooms and see if it is removed by the next time you return. Oriole’s single-occupancy washrooms complicate this procedure—how to ensure you can get back to the same one? Likewise, they facilitate the process of refreshing the rooms by allowing the staff to take one offline at a time while guiding guests towards the several other pristine rooms.

Thus, you got a bit sneaky and—emboldened by more than a few glasses of wine—devised something slightly more challenging. Rather than taking the perspective of someone checking the washroom from the outside, you cast your eyes towards the door from the inside. Rather than focusing on the floor, you looked upwards. The emergency light fixture, hung over the door, seemed like a positively evil place to hide the towel. Taking care not to obscure the LED in any way (you’re not that evil), you stood on tip toes and rested the hand towel on top of the box. It was placed there in October of 2021 and remains in that spot at the time of publication.

For what it’s worth, you conducted the same test at Smyth, and, though the towel was not immediately noticed, it was removed within one month.

Regardless, entering Oriole’s lounge for the first time leaves no room to bother with such trifles. As your eyes strain to capture all the new details, the captain leads your party over to the bar that rests against the rear wall. She helps you each situate yourselves in one of the raised chairs while the barkeep looks over and offers his own warm greeting. He mans the counter, which may house two or three groups of diners at time, with real gravitas. His effusive demeanor, partnered with graceful movements and an all-seeing eye, sets the tone for the service experience. It distills the same energy you felt from the start—drinking tea by the elevator—and puts it into practice within a carefully staged space.

The bar brings you face to face, once more, with the glorified alleyway called Walnut, but a set of curtains now often obscures the view outside. Instead, you fixate on the brown wood, brown brick, and the pair of hanging speakers (actually vintage or retrofitted?) that bookend the bottles arranged on a simple three-tiered rack. The collection comprises Ardberg, El Dorado, and Kentucky Owl (to name but a few characterful choices). There are candles, myriad shapes of gleaming glassware, and an assortment of greenery in stout pots. A sous vide setup whirs away in one of the corners while a member of the kitchen staff, clad in whites, keeps busy in the background.

Yet, aesthetics aside, Oriole’s bar forms the perfect place to set the meal in motion. The captain takes your wine bag and makes the sommelier aware of the intended corkage. The bartender does not only note which type of water you prefer, but is well-positioned to observe the handedness with which you wield your utensils. These preferences are communicated and adapted for, in perpetuity, long before guests reach their table. Moments later, the sommelier arrives in search of further instruction. Would you like to begin enjoying your bottle right now at the bar? Should the other be decanted ahead of time? Or perhaps you would prefer to take a quick taste and then decide?

On other occasions, sitting at the bar offers a convenient chance to signal your desired participation in one of the restaurant’s wine pairings. Or, perhaps, that time allows you to browse the list, make a couple bottle selections, and empower the sommelier to orchestrate their service—with regard to temperature and aeration—during those crucial moments before you are formally seated.

For the majority of diners, posting up at the bar is merely a fun detour. However, for the most neurotic of hosts, it allows them to dot the i’s and cross the t’s of the evening’s meal. Indeed, beverage service can be easily arranged ahead of time, to whatever excruciating degree of detail demanded, via e-mail. But conditions (or consumer knowledge) do not always allow this to happen. Thus, oenophiles are afforded a free period to submerge themselves in all the options without ignoring guests across the table. They gain valuable time to get everything in order before the menu hits its stride, making the marriage of fine food and drink seem effortless to the uninitiated. The serious, nerdy conversations related to wine appreciation can be conducted slyly, off to the side of this casual setting, without infringing on the larger drama of the meal. Rather, the host—having been relieved of their last responsibility—can now confidently and wholeheartedly engage their guests for the rest of evening.

But Oriole’s bar is far more than just a waiting area. It plays home to the tasting menu’s opening salvo and offers, in your opinion, the most consistently superlative series of bites served anywhere in Chicago.

First, appropriately, the bartender serves you a drink, but he’s careful not to overwhelm your palate. His cocktails are built upon a base of verjus, a non-alcoholic juice—often used like a vinegar—made by pressing unripened grapes. Sweet, tart, and highly acidic, the ingredient also brings a sense of weight and body to whatever it is blended with. Thus, when paired with complicating notes like snap pea, corn husk, yuzu, or black pepper, the verjus makes a dead ringer for a real apéritif. Recent blends have included herbal teas made from a Malabar spice blend or even gai lan (Chinese broccoli). The latter, paired with ginger and a verjus rouge, was bright, spicy, bitter, with a surprisingly luscious mouthfeel.

Each of the drinks hearken back to the non-alcoholic pairings that the restaurant has offered since the early days of “1.0.” Back then, and especially in Chicago, zero proof programs formed little more than a token gesture, a nicety paid towards non-imbibers who found themselves in a fine dining setting. At Oriole, Julia Momose crafted non-alcoholic pairings that were equal (and, sometimes, superior) to the typical pour of wine or sake. They were the first examples of the sort that turned the heads of dedicated winos such as yourself. These pairings formed a real feather in the restaurant’s cap and, thankfully, still persist to this day.

Despite Kumiko’s well-earned success, Momose continues to apply her talent to the N.A. program, along with a unique assortment of cocktails that can also be ordered from Oriole’s bar. But that welcome drink, served to any and all diners as they prepare to take their first few bites, forms a fitting showcase for an artisan whose work will forever be intertwined with the restaurant. In truth, you have never really noticed that the “cocktails” lacked alcohol, just that they always tasted delicious and disappeared far too easily. Such artistry provides guests with a memorable opening toast while, at the same time, safeguarding their perception of the refined flavors to come. It inverts the pre-meal apéritif’s purpose, retains a sense of pleasure, and honors Sandoval’s cuisine.

Shortly after the drink is poured, the menu’s first morsels appear.

During your first “2.0” experience during the summer of 2021, a snap pea and verjus cocktail was paired simply with a Nichol’s Farm tomato that had been accented by bay leaf and kabosu (a tart-sweet citrus fruit that is slightly less sour than yuzu). By September of that year, the snap pea element of the drink had been substituted for fresh corn husk, and the tomato was now sourced from Wild Trillium Farm in Richmond, IL. That bite was also joined by two more: one made from ocean trout (with nasturtium and yuzu koshō) and another from trout skin (formed into “soba” with galangal root and enoki mushrooms). Sandoval’s expansion of the bar bites from a soloist to a trio was most welcome, better cementing your positive association with the space. But the chef was just getting started.

Sometime during the fall, he struck upon a sequence of opening small plates that you can only describe as offering the ultimate decadence.

First arrived the one-two punch of Norwegian king crab and Maine sea urchin. At first glance, the two coveted shellfish were seemingly stacked atop a piece of maki. However, the base of the bite is something more like a thin, crisp pastry shell. It possesses the strength and stability to hold the composition together with a hollow center, filled with Koshihikari rice, that helps the constituent parts meld into a cohesive package. A bit of yuzu koshō, dusted across the top of the crab, completes the presentation. It imparts a fresh, zesty, and only slightly spicy flavor that unleashes the latent sweetness of the uni and crab.

The whole bite, once it enters the mouth, collapses cleanly. The fine grain of the pastry shell and its rice filling is moistened by the sappy, saline sea urchin that stretches across the palate and forms a perfect cushion for the buttery flakes of crab tinged with that hint of the yuzu-chili condiment. Over time (and in season), Sandoval has come to adorn the creation with fine strands of shaved white Alba truffle. More recently, he’s found a way to position large shavings of Périgord truffle on top of the piece so that they form a crowning peak. This latter variant has seen the uni now placed atop the crab, but the bite retains its essential appeal. That kiss of earthy Tuber only gilds the lily of what has always been perfectly engineered, generous expression of totemic shellfish.

Second came the lobster dumpling, a gorgeous morsel that is given its own small bowl. Along with the artfully wrapped crustacean, it contains a broth made from galangal (a sharper, spicier relative to ginger) and red kuri squash (a full-flavored, sweet variety related to kabocha). A few floating flower petals form a simple but striking garnish, which most recently has also come to include a tableside grating of dried blue banana squash.

Oriole’s dumpling originally featured Maine lobster but has now made use of spiny lobster for some time. The difference, having mostly to do with claw size, is slight. Spiny lobsters possess a more subtle sweetness than their Maine counterparts, but they are also more commonly used in China (where they are paired with sauces not unlike the accompanying broth). No matter the filling, the texture of the dumpling is consistently superb. The thin wrapper yields to a firm yet tender chunk of lobster that further distinguishes itself through the chew of its outer layer. The crustacean’s mild sweetness is extended and enhanced by sweet, spicy, and nutty broth, whose lingering warming effect serves only to underscore the savor.

You have enjoyed the lobster bite each and every time it has been served; however, you must applaud the recent decision to extricate the dumpling from its broth. Now, guests can appreciate the delicacy of the wrapper to its fullest while the flavorful broth sits in an accompanying vessel. This extra element of control widens the window of enjoyment by better distinguishing (and, thus, celebrating) each of the components.

Third, in fulfillment of the totemic shellfish trinity, arrived New Zealand langoustine. While the crab-uni and lobster bites were originally served sequentially after the tomato, the langoustine would come to replace the tomato at the top of the batting order. Eventually, the dish would settle into the middle of the progression—a testament to how finely tuned Sandoval’s bar sequence has become.

While the lobster is put under wraps, Oriole’s langoustine takes a more pristine form. It swims at the bottom of a misshapen bowl with chunks of young coconut and an eye-catching dressing made from the juice of Asian pears dotted with globules made of yuzu. Pearls of finger lime are interspersed throughout, lending the dish a concentric sheen that matches the translucence of the langoustine itself.

The crustacean is thinly sliced and served raw. It glides across the palate and offers only the faintest resistance upon being chewed. That forms the perfect foil for the bursting orbs of finger lime and the soft, smooth pieces of young coconut that, in turn, further accentuate the langoustine’s texture. The flavor, too, is superb. Its natural sweetness does not demand as much help as the lobster. Rather, the langoustine requires nothing more than the dish’s assortment of complementary sweet, tart, and sour notes to shine. Despite all the citrus, a moderate acidity, importantly, prevents the crustacean from being overshadowed. The bite delivers a pure expression of the ingredient with a pleasing fullness and length.

The fourth and most recent bite—having replaced the langoustine and gone to the front of the order—is a tartare of A5 Miyazaki beef. It is dressed with a wagyu fat aioli and sandwiched between two crisped leaves of shiso. The combination is garnished with a few sprigs of microgreens that jut out from the top, but it’s ultimately a well-packaged morsel in the same vein as the uni-crab composition.

While not as intensely flavored as the langoustine dish once was, the beef bite forms a fitting transition into the uni and crab. You admire the rigidity of the shiso, which forms something like a bright, herbaceous cracker against which the softness of the tartare can shine. The aioli, too, helps ensure that the wagyu’s flavor resonates long after it melts on your tongue. Despite comprising no more than a few chunks of meat, the Miyazaki displays impressive weight on the palate. Though the umami mouthfeel lasts but a few seconds, the tease will undoubtedly see itself fulfilled later on. For Sandoval has made the A5 steak a hallmark of his tasting menu, and offering a small preview of what’s to come imbues the meal with a satisfying sense of cohesion.

The relatively new wagyu item makes clear that Oriole will continue to pursue an evolving series of luxurious bar bites to preface dinner. While your longstanding reservations regarding these totemic ingredients remain, Sandoval subverts their status by immediately placing them front and center. He goes straight for guests’ jugulars and scales towering heights of pleasure as an appetizer, freeing the chef to approach the menu proper without any lingering “luxury dining” expectations. You must admit that it’s a savvy move, especially given the restaurant’s status as a consistent (if a bit static) guarantor of satisfaction. This staggering start to the meal does not only erase any lingering skepticism that regards fine dining as meager “tweezer food,” but has the added benefit of empowering greater creativity later on.

The three bites come and go in short order, amounting to an interlude that lasts a little more than ten minutes. The bartender bids you adieu, and your captain returns to collect the party for the next stop on its tour. They lead you across the lounge, passing the private dining space and bathrooms, through the threshold that marks the kitchen itself.

As much as you love the new wine cellar, bar, and lounge, Oriole “2.0’s” most consequential renovation is undoubtedly here. Rather than being couped up at the rear of one solitary dining room, Sandoval and his team now occupy the very nucleus of the entire restaurant. Of course, those opting for one of two Kitchen Table experiences (at a $40 premium per person) will be treated to front-row seats. But guests who find themselves in the dining room still feel a sense of connection with the back of house. Some seats maintain sightlines with the kitchen while any trip to the restroom, necessarily, brings customers back the way they came (and, thus, in close proximity to all the action). Even those who book the “Oriole Nightcap” experience (staged solely within the lounge) will most likely get a peek at the goings-on.

However, in terms of action, there isn’t much to note. The kitchen is so spacious and the team so well trained that the cooks quietly and confidently labor for the duration of the evening. Even from the vantage point of one of the kitchen tables, no part of the culinary action really grabs your attention.

By comparison, the closer confines of Alinea’s back of house—combined with the intricacy of the techniques on display—lend a palpable sense of energy to proceedings. Whether brought there for a quick drink and a bite or ensconced at the lone kitchen table, you feel there is something worth observing in every direction. The sense of “show” that Alinea conjures (at the cost of creating delicious food) is lent credibility upon witnessing the flurry of activity backstage. In fact, the effect is so great that it muffles diners’ misgivings about what they’ve been served. Surely, they think, so many toques earnestly engaged in their craft must produce something amazing. They, the first-time diner, must simply lack the refinement to properly appreciate it!

Likewise, Smyth’s kitchen space is about half the size of Oriole’s now. It is just as sleek and orderly but strikes you with a greater sense of coordination. The cooks maneuver around each other and place saucepots to and fro with perfect synchronization. They huddle up in groups of three or four for plating on both sides of a central pass located just feet away from the first row of tables. Meanwhile, a hearth blazes in the corner, and guests may notice its flames quite literally being fanned from time to time. But none of that ever stops Smyth’s back of house from clapping along to the chorus of Hall & Oates’s “Private Eyes.” They keep busy but are always thoroughly present. Diners get the “show” along with a great deal of charm.

Even Ever’s kitchen, it must be said, benefits from feeling a bit cloistered. Hidden behind frosted glass, a sense of mystery prevails. However, when guests are granted a post-meal audience, they find a well-oiled machine. Quiet, exacting labor (of the same sort seen at Alinea) quash any lingering fear that they have just been served a bunch of gobbledygook. Ever even livestreams service from a stationary point inside of the kitchen, enticing would-be guests with some sense of the effort being expended in deliverance of their future experience.

Of course, the appearance or sound of activity does not ever guarantee that work of any quality is being done. Rather, the frantic energy fulfills the fantasy aspiring fine diners carry with them into the kitchen. They may never see the intensity of Gordon Ramsay’s larger-than-life persona realized in a professional setting, but the price paid for artisanal cooking is, in part, justified through some visceral sense of the effort being expended.

Oriole’s subdued workflow within a sprawling setting better reflects what “luxury” looks like from the perspective of a cook. The kitchen’s quiet pursuit of excellence with all the space and tools to do so reminds you of the setups at Meadowood or The French Laundry (post-renovation). This design privileges comfort over theatrics and affirms that the restaurant’s focus remains squarely on how to best execute its food.

Nonetheless, Sandoval does not overlook the importance of forging a connection between the diner and the kitchen. Your captain guides the party over from the bar to the central pass of the kitchen. Behind it, off to both sides, are two additional surfaces that stretch towards the backwall. Opposite those (and neatly tucked behind slivers of wall), are the ranges, hoods, and other tools that make the magic happen.

As interesting as that all sounds, guests’ eyes are naturally attracted upwards towards the collage of vintage concert posters that bedecks the ceiling. Depending on where exactly one stands upon being led to the pass, there always seems to be some new artist, some new album to note. This design element is beautifully illuminated by a glowing border of light. Track lighting, along with a chandelier, are subtly incorporated so as not the spoil the whole effect. Instead, a few scattered bulbs placed on the wall far back behind the center pass naturally lead your eyes upwards.

Thus, while the cooking process at Oriole might offer little to fixate on, the ceiling ensures guests feel captivated. Plus, when standing at the pass, you’re not given much time to pause anyway. The sommelier comes over and offers the assembled diners a drink. That might mean Champagne, Tasmanian sparkling rosé, vermouth, or Txakoli poured from a porrón. With the guest having just been treated to a welcome “cocktail” at the bar, the offering of wine feels doubly generous. Clutching your stemware under the shining lights of the kitchen while occupying pride of place within the entire restaurant feels positively glamorous. For those who privilege ambiance and a sense of occasion as much (or more than) the food itself, the moment is a real money shot.

But the pass plays home to more than just a drink. In front of each guest, the cooks deposit wooden stands holding gold-tinted plates topped with yet another luxury totemic flourish. At this moment, Sandoval himself comes over to describe the dish and formally conduct the toast. It’s a beautiful welcoming gesture that ensures every diner gets to rub shoulders with the chef. At the same time, there’s a consistency, simplicity, and high degree of control to how it’s executed, for visiting tables as they sit in the dining room is fraught with peril and prone to stoke self-defeating jealousies if not done carefully. Instead, everyone meets Sandoval within his natural habitat, timed with an effortless rhythm, during a period of the meal already marked by wonder. In this manner, Oriole “2.0” has found a way to guarantee that guests cement an all-important personal connection to the chef-artist whose mere presence elevates the perception of cuisine.

That being said, the dish served at the pass needs no such help. It comprises a slice of toasted brioche atop which has been placed a thick, creamy coating of Hudson Valley foie gras. The liver is then topped with fruit. Originally, that meant blueberry, but the restaurant changed it for huckleberry and, most recently, has opted for French fig. A few peppercorns (either pink or black) and some microgreens (either oxalis or anise hyssop) serve as garnishes. But the real finishing touch comes from a dusting of gold leaf, whose tiny, shining particles trickle across the leaves and down onto the fruit, foie, and bread.

Of the four opening bites that preface guests’ arrival at the table, Sandoval’s foie gras dish has remained the most consistent. It forms the “closer” within a sequence of unsurpassed luxury, placing the misunderstood duck liver up against more fashionable fare like crab, sea urchin, truffle, and wagyu beef. Yes, you enjoyed those bites at the bar, but, with his guests before him at the pass, Sandoval swings for the fences. The chef’s foie gras dish, throughout each of its small tweaks, has always been a stunner.

The liver itself is unerringly smooth and powerfully rich. Placed up against the toasted brioche, it forms the fattiest, meatiest kind of “butter” imaginable. But then strikes the tart-sweet fruit, its jammy consistency enveloping the other ingredients and unleashing, by its contrast, an even greater savory dimension from the foie gras. The subtle heat of the peppercorns and sour, floral character of the microgreens serve the same purpose: engineering the most intense and pleasing expression of liver possible. The dish, which leaves delightful traces of gold powder on your hands as you eat it, stands as the apotheosis of an ingredient that risks falling out of favor in this democratized era of fine dining. In Sandoval’s hands, foie gras reminds you why it has been prized for millennia.

At last, it comes time to take your seat. The realization that the meal, as such, has not yet begun is intoxicating. You’ve already derived more pleasure from those opening few morsels than many Michelin-starred establishments deliver over the course of an entire evening. Just what is Oriole capable of once you reach the table? Or, rather, can anything hereon plated and served live up to the preceding parade of luxury totems?

Whether or not Sandoval’s opening salvo forms the early crescendo of the meal, the gravity of the sequence remains the same. According to the peak-end rule, a peak is a peak and will retain the highest salience in judging the experience no matter when it occurs. Moving from the sleek bar to the glowing kitchen pass, sharing a couple drinks, toasting with the chef, all while enjoying a selection of superlative bites that sound like a laundry list of coveted ingredients is, no doubt, a shining experiential peak. It’s a hallmark of Oriole “2.0” that measures up to the excitement of Alinea’s “table dessert” while resonating more deeply at both a gastronomic and human level.

Of your nine meals at Oriole “2.0,” eight of them have occurred at one of the two kitchen tables. Your lone experience in the dining room itself was also your very first visit (post-renovation).

In your haste to secure a reservation after the restaurant announced its reopening, you overlooked the “Kitchen Table” category on Tock altogether. That irked you to no end, for you assumed that the premium seating comprised some extended expression of the tasting menu. At core, it may be a nasty, jealous instinct, but it’s hard to appreciate even the most rarefied luxury if you get the gnawing feeling that other guests are receiving something finer on the other side of the wall. Alinea malevolently channels this latent insecurity into a three-tiered pricing scale (The Salon, The Gallery, and The Kitchen Table) while Daniel, in NYC, saw itself downgraded on account of the special treatment afforded to notable patrons. (Oriole, smartly, sidesteps this issue, but more on that in a bit).

You were peeved that your inaugural meal would be in the dining room (instead of the shiny new kitchen), but something Aaron McManus said put things in the right perspective. The longtime Oriole beverage director noted how nice it was to host you again in the restaurant’s original space, to rekindle the memories made within those confines after so many months of pain and uncertainty. His words struck upon the fundamental beauty of Oriole “2.0’s” dining room: it honors what came before.

The most consequential detail regarding the restaurant’s renovation was that it “increased seating capacity by only three.” You think that discounts the bar, lounge, and private dining space, which lend the establishment some added flexibility, but the point remains the same. As much as Oriole “2.0” is characterized by physical expansion, it also, actually, represents a refinement of the “1.0” experience. Nowhere is this more apparent than in the dining room.

The wood-paneled ceilings and brick walls remain. So do the block glass windows, but they are now hidden behind shades. The wooden beams that separated four- and two-tops throughout the original space now serve primarily as guideposts. These bones, which still boast the same colored finish as before, are highly nostalgic. They help orient you to what has, indeed, changed.

The banquettes are gone, as well as the rectangular tables altogether. The armchairs and white tablecloths remain, being now positioned around circular tables (seating two to six guests) that line the circumference of the room. Each setting is illuminated by its own hanging fixture that casts bright, white light over the surface while striking diners with a softer glow. The space separating each of the tables is more shadowy. That, along with the darker staining of the wood flooring, lends each party a feeling of privacy. Moreover, it makes each of the tables feel like its own small stage.

At the very center of the dining room now stands a service station. It is complemented by additional shelving affixed to the wall that holds glassware. Other shelves, as well as the windowsills, are accented by tiny plants and glass ornaments. You particularly enjoy the small rabbit sculpture that adorns one of them (a subtle wink to the photo that once graced one of the walls).

Overall, Oriole “2.0’s” dining room feels more spacious, dramatic, and luxurious without denying its heritage. It maintains a sense of place, concomitant with its location on Walnut Street, that makes for a timeless design. The restaurant’s identity has not been changed so much as further fulfilled, and there remains a sense of restraint that channels guests’ focus onto Sandoval’s food.

The two kitchen tables are cut from the same cloth. They are positioned behind the central pass in the corners bordering the short set of stairs that leads down into the dining room. Their vantage point is even more distant than that during the foie gras bite and welcome toast, so there’s really not much to note when it comes to the cooking going on. Rather, you are primarily paying for the comfort of a plush booth and the privacy being at the fringes of a separate space entails. That seems counterintuitive, given that each party is brought by the pass on their way to the dining room. However, enough distance is maintained between the flow of diners—as well as the other kitchen table across from you—that you never feel yourself ogled.

Plus, as much as you might not get to observe Oriole’s cooks in action, you do get to interact with them more. Typically, they’ll venture into the dining room to sauce certain plates tableside. However, at the kitchen table, you’ll see them deliver and describe many more dishes. This stokes the flame of that human connection the opening toast first forges. You feel more connected, even at the periphery, to the execution of craft that goes on underneath that transfixing ceiling.

Nonetheless, the ability of a restaurant’s back of house to captivatingly present dishes is not something to take for granted. They might, naturally, possess a more intimate relationship with the finished product by playing a part in its creation. However, knowledge of technique and process does not always translate into a successful tableside spiel. In fact, between the mechanics of finishing a dish tableside and the mental burden of describing it perfectly, the presenter may lack the bandwidth to exhibit any dimension of their personality beyond that of the anonymous kitchen drone.

In this respect, your early kitchen table meals at Oriole “2.0” were largely defined by competence. The cooks hit their marks, bridging the gap between back and front of house, affirming the special status of those two booths, but never enchanting you with that special sense of individual artisanship. Apart from Sandoval and his pastry chef, the rest of the kitchen staff felt amorphous and interchangeable. They operated as honed instruments of the larger enterprise rather than distinct, actualized expressions of themselves. (And that is nothing to feel bad about, for the restaurant’s front of house staff is uniformly charming and better-situated to deliver a reflexive, own-rooted expression of hospitality).

A few months after Oriole’s reopening, during one dinner at the kitchen table, you had caught wind that the restaurant was conscious of the fact that you were evaluating them. (Never mind all the visits paid during the “1.0” days). Little seemed out of the ordinary—as best as you could tell—and the meal proceeded in a similar fashion to your other “2.0” experiences.

However, part way through, one of the cooks tasked with delivering some elements of a course to the table arrived with trembling hands. With bated breath, you watched him maneuver a small serving vessel within a maze of stemware, his shakes magnifying as he reached the intended destination. Politely, your party continued its conversation, but you could not look away. Finally, the vessel had just about reached the surface of the table when it was released with a sudden jerk that clinked a neighboring glass. Though nothing shifted or was spilled, the resounding note called attention to the cook’s departure. It broke the spell of technical perfection that Oriole generally operates with (even if the virtuosity often goes unnoticed) and called attention to the vulnerability of the kitchen table format.

You see, Oriole “1.0’s” service, led by general manager Cara Sandoval, had always been of the highest caliber. Polished movements, artful descriptions, and attentiveness merely formed the foundation upon which a genuine sense of warmth revealed itself and a singular guest relationship was forged. The opening of “2.0” tasked the restaurant’s front of house staff with executing a whole new performance within a novel space. The script—and its blocking—had to be learned and executed until it, once more, became second nature. Only then, from that position of supreme confidence, could transcendent hospitality once more occur.

The kitchen table experience not only demands the same process of acclimation from the front of house staff but conscripts a larger contingent of the back of house to get in on the act. For the cooks might typically display their sauce work in the dining room but, now, must titillate guests with dish descriptions that do the dedicated captains justice. The back of house must, essentially, live up to the expert tableside manner of their colleagues while then, maybe, heaping on a bit of individual charm to boot. Even Sandoval himself, though he has engineered the ideal moment to connect with his guests, must fulfill the impossible standard his wife has set now that he stands front and center in that shiny new kitchen.

Your first few meals at Oriole “2.0” had their service missteps, yet all were immediately corrected and permanently remedied. The trembling scene at the kitchen table—which, in truth, did nothing to upset your meal—represented a nadir in terms of attitude rather than offense called. Why, even if a certain table is alleged to contain a critic, allow a sense of fear to infect the practice of service? Trying too hard, even if it entails special treatment, is bound to erase the sense of ease and naturalness that forms the sine qua non of superlative hospitality. At worst, such an instinct becomes self-defeating and, by perpetuating anxiety, stands in the way of satisfying even the usual standard of service.

Nonetheless, the nervous clinking of glassware that evening did not form a nail in the restaurant’s coffin. Rather, it now stands as a testament to the team’s growth. Over the past seven months, the back of house has grown adept at serving the kitchen tables. That not only means mastering the mechanical process of presentation, but doing so with eloquence and elegance. The team now possesses at least a couple cooks with a real knack for communicating their passion to the guests. They measure up to the standard set by the front of house while still retaining that “behind the scenes” authenticity patrons at the kitchen table are paying for.

The front of house, too, has found its footing serving a new menu throughout a new space. Their technical excellence, which was never in question, has become second nature and led to a pleasant softening of interaction. Frantic energy, channeled towards the pursuit of perfection, has faded into the calm confidence derived from months of operation. Ease, warmth, humor, and charm flow naturally. “Server” and “served” feel more like friends as the team’s sense of duty towards diners is subsumed into a larger, deeper expression of self.

Operating at this level, no detail is missed and every request is made to feel possible. You, the guest, are treated like an individual rather than one of countless, interchangeable customers. The restaurant humbly prostrates itself before your singular proclivities rather than expecting you to take a number, stand in line, and worship at the altar of “luxury dining” in accordance with the same fine print and implicit restrictions as everyone else.

Oriole “2.0,” you are happy to report, has achieved the same delightful tone and tenor of service as “1.0.” The attractive new digs do not overshadow the old design’s sense of intimacy but, rather, allow that warmth to fill an even greater space. In doing so, the restaurant’s hospitality distinguishes itself as belonging to that rarest, truest type. Oriole is a place you can sincerely feel at home (no wonder there’s a rumored bed and breakfast upstairs), and that feeling comes from the very top.

Cara Sandoval deserves credit for fostering a team so thoroughly present that the depth and details of service never cease to grow. She, herself, when you are lucky enough to cross paths, forms a shining exemplar of the craft. And that same spirit is felt elsewhere across each interaction with the full range of professionals that give life to the restaurant. Even the chef, it must be said, has taken great strides towards fulfilling the role of host. It’s not a duty that many of Chicago’s culinary luminaries embrace, but one that Noah has approached with playfulness and sincerity. With post-renovation plaudits sure to soon arrive, you cannot think of two better representatives for the city at a national (or international) level.

At last, you take your seat within one of the kitchen table booths. Though, typically, you prefer to make your beverage selections while still seated at the bar (if not before), many guests will only now be met with a choice. Considering parties have already been plied with a few drinks during the meal’s preface, it’s not a hard choice to make. Oriole makes its pairings—“Spiritfree” ($105), “Standard” ($145), and “Reserve” ($275)—seem like a natural part of the experience. It’s all too easy to keep things rolling smoothly by assenting to one of the three curated options, and you think diners are well served by doing so.

While Oriole’s “Standard” pairing matches the prices set by Smyth and Alinea ($145), McManus’s “Reserve” pairing lands north of Ever’s sole pairing option ($185) as well as the reserve selections offered at Smyth ($215) and Alinea ($235). At the same time, it costs significantly less than the “Smyth Super Mega” ($355) and “The Alinea Pairing” ($395) options.

Truth be told, while you enjoy sampling these ultra premium selections, you are unsure if they drive more casual consumers to “compromise” by choosing the middle option (reserve) or drive them back towards the comfort and familiarity of a traditional pairing altogether. Are diners that are looking to splurge satisfied by some middle expression of luxury, or would they sooner spend that money on a bottle off the list or something else (menu supplements, drinks at the bar) during the course of their evening?

Few restaurants in Chicago can boast a cellar filled with mature wines, so that extra $140-$160 (from reserve to super) often secures you one or more youthful bottles from absolutely top-tier producers that, nonetheless, are far from prime drinking. A great sommelier, such as Smyth has, will ensure your money is channeled towards the best accompaniments for a given menu. They will work hard to bring the coveted bottles towards their fullest expression possible in the time allotted (no small task should you order such a pairing upon being seated). But, at their worst (read: Alinea), such top-tier pairings are little more than a parade of labels lacking any distinct character or hedonistic appeal. They guild the lily but do little to prove how the finest wines work to elevate incredible cuisine.

Oriole, smartly, sidesteps this entire conundrum by forming a simple dichotomy: “Standard” is “heavily wine focused but may often include a sake, cider, or cocktail” while “Reserve” focuses “on higher end wines….with a little more age” that represent “some of the best wines available to the restaurant.” To the aspiring fine diner looking for a fun night out, the former option—due to its broader range of beverages—seems like no compromise. For wine-loving patrons, the latter says just what you want to hear (with no question of some other, ultimate option priced even higher).

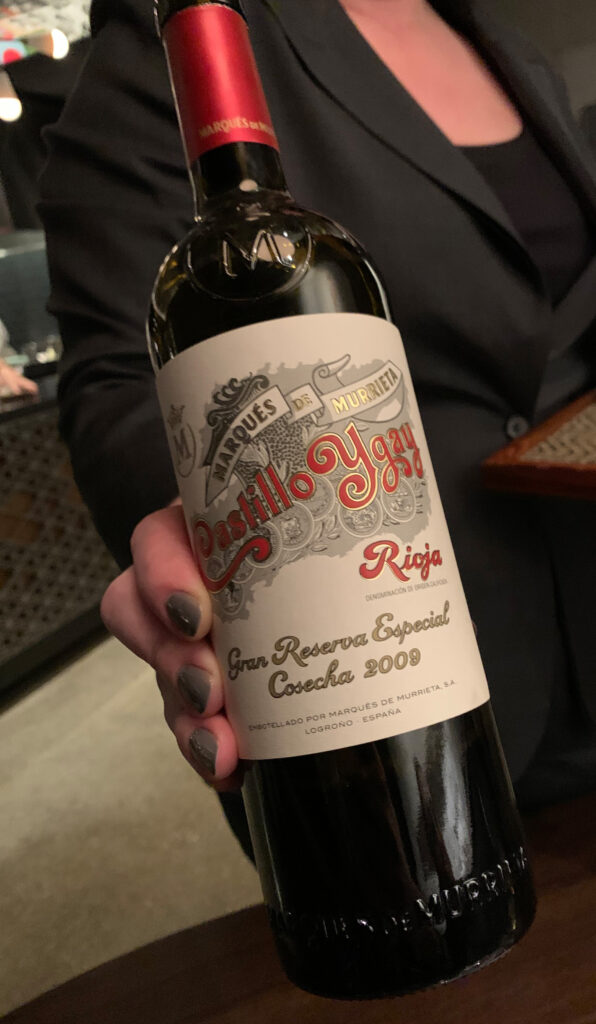

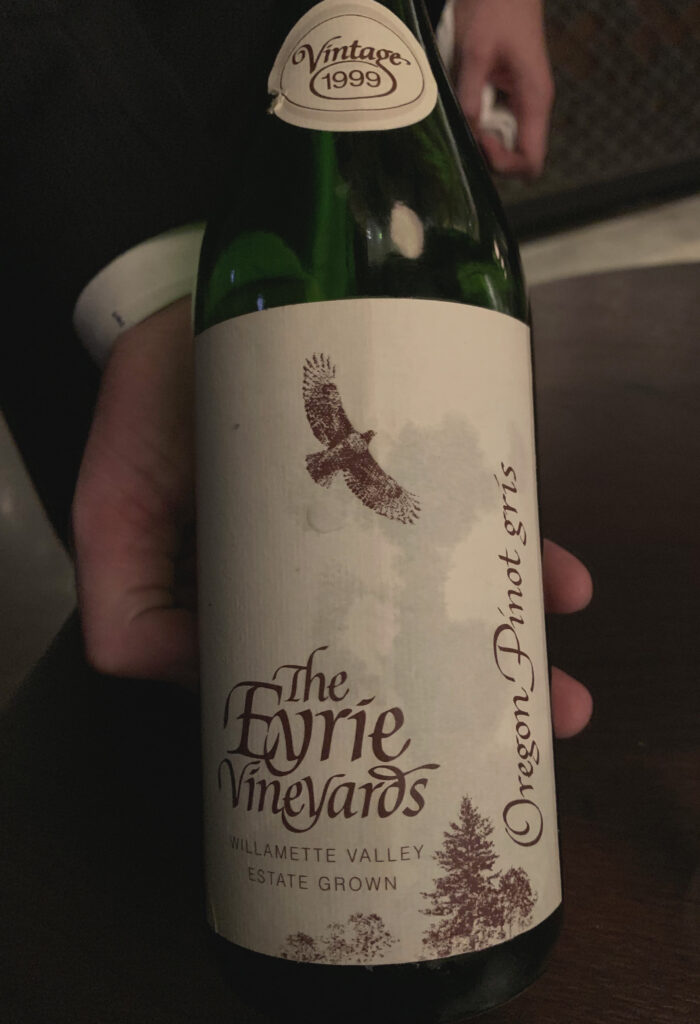

McManus’s “Reserve” selection has included wines like Laurent-Perrier’s Grand Siècle, Trimbach’s 2011 “Cuvée Frédéric Emile,” R. López de Heredia’s 2008 “Viña Tondonia” Blanco, F.X. Pichler’s 2012 Grüner Veltliner “M,” Domaine Parent’s 2015 Corton Blanc, and François Carillon’s 2013 Puligny-Montrachet “La Truffière.” Reds have included a 2005 Gruaud-Larose, a 1996 Grand-Puy-Lacoste, and a 2007 Clos des Papes while dessert has featured a 2007 Sauternes from Suduiraut and a 1988 from La Tour Blanche. Saint-Chamant’s Cuvée de Chardonnay Champagne and Eric Bordelet’s “Granit” pear cider are also prone to appear later on in the meal, providing bursts of refreshment following the heavier fare.

While decidedly classic, these bottles are thoughtfully chosen. They encompass good and very good producers while avoiding the kind of cult names that would totally destroy the pairing’s value proposition. Instead, McManus is able to offer an assortment of wines each possessing a bit (or a lot) of age and, thus, a higher degree of character. They are expressive and representative to a degree that encourages customer education. At the same time, the selection indulges in timeless combinations like white Burgundy and fish or Bordeaux and beefsteak that, when constructed from Sandoval’s cuisine, deliver wholehearted pleasure. Oriole’s sommelier honors the chef’s menu by avoiding needless obscurity and, instead, delivering top quality-to-price-ratio bottles within the regions every diner is sure to love.

The quality and accessibility of McManus’s premium pairing only grows in stature upon reading his bottle list. It forms the counterpoint through which oenophiles can treat themselves to hidden gems and top-tier producers that would provide diminished returns if offered as part of the “Reserve” selection. Befitting its gorgeous new cellar, Oriole’s list features wines from such illustrious names as Pierre Peters, Cédric Bouchard, Ulysse Collin, Jacques Selosse, Guiberteau, Roulot, Benoît Ente, Bernard Moreau, Dauvissat, Pierre Girardin, Comte Lafon, Leflaive, Ramonet, Antoine Jobard, PYCM, Ganevat, Clos Rougeard, Sylvain Cathiard, DRC, Roumier, Mugnier, Méo-Camuzet, Lafite, Mouton, Gaja, Conterno, Montevertine, and Vega-Sicilia.

Despite this laundry list of top producers, McManus’s selection is hardly a mausoleum of expensive labels. The restaurant’s mark-up remains one of the lowest in town, putting most other fine dining establishments to shame. A bottle of Krug “Grand Cuvée” ($375) or 2008 Billecart-Salmon “Cuvée Elizabeth” ($405) at Oriole would cost $515 and $575 respectively at Boka. The 2010 Dom Pérignon ($375) costs a whopping $615 at Ever while the 2015 Gaja ($325) would cost $515 at Maple & Ash. At the more affordable end of the spectrum, a 2020 Keller “Von der Fels” ($105) costs $120 at Monteverde, and a 2016 Dauvissat Chablis ($125) costs $194 at RPM Seafood. These comparisons across restaurants might not automatically come to mind for most diners, but they will undoubtedly be struck by the friendliness of Oriole’s pricing.

There is truly value from top to bottom, spanning everything from a $30 bottle of Spanish Palomino Fino to a $2,050 bottle of 2016 Roumier Bonnes-Mares (whose current global average price, it must be said, is already $2,453). Any diner, no matter how much money they are spending, will find that it goes far on the restaurant’s list. Personally, you think supplementing one of the wine pairings with an additional bottle chosen in accordance with one’s taste is a wise strategy. It enables the guest to explore the harmony of wine with Sandoval’s food while also appreciating a singular selection from McManus’s cellar during the course of the evening.

Though you have already noted that the dishes on Oriole’s menu do not change as frequently as some of your most beloved restaurants, such an excellent wine program works to bridge that gap. Sandoval’s cuisine, by consistently delivering intensity and depth of flavor within recognizable forms, forms a beautiful canvas for a wide variety of grapes. While McManus’s classically styled pairings accentuate traditional similarities and contrasts for a wide audience, his ever-evolving list ensures oenophiles will always find a compelling pairing of their own to make. You might arrive at the restaurant with a hankering for some particular fish preparation from last time and wonder how it might play off of a Grosses Gewächs Riesling this time. Maybe the chef’s trademark wagyu calls out, tonight, for aged Champagne or Napa Cab. The wine, in these instances, breathes new life into the experience and turns the relative stability of the menu into a virtue.

A rather fair corkage policy ($50 per bottle, maximum of two per reservation) rounds out the equation. Guests do not face any dearth of choices between the pairings and the lists, but such a policy—compared to the strict embargos maintained by Alinea and Ever—ensures collectors and celebrators of special occasions can bring their very best wines to the table when they so desire. Most recently, Oriole has even added a “Large Format” category to its book. By offering magnums at the same attractive prices as normal-sized bottles, the restaurant stokes a sense of merriment and generosity that lends the environment an infectious energy. You get the impression, overall, that the establishment respects and honors what wine might lend to a great meal. That sounds rather elementary, but it has increasingly been forgotten (and by some of the city’s biggest names too).

No matter what beverage selection guests make, they are treated to the same sense of precision, personality, and charm that pervades all service encounters throughout the restaurant. McManus and his equally-talented counterpart are experts at making fine wine seem engaging and fun without ever infantilizing its presentation. At the same time, they capture the sense of wonder and romance that characterizes famed regions without descending into geekery or snobbery. The feeling, instead, is always one of generosity—that the riches of the restaurant’s cellar are only waiting to be imbibed. This sense of balance, channeled through a natural and deferential demeanor, equips the wine team to impress drinkers no matter their level of experience. At the same time, should you task them with opening a fifty-year-old Trockenbeerenauslese you brought along, they rise to the challenge without a moment’s pause.

Oriole’s wine program is of the very highest caliber. You can only count a couple other Chicago restaurants that measure up to such a standard. Even then, Oriole just might be the best.

With your beverage order settled, the meal recommences. On the back of the crab, uni, langoustine, lobster, wagyu tartare, and foie gras bites served at the bar and kitchen pass, Sandoval aims straight for yet another luxury totem. The chef features Golden Kaluga caviar, a firm, clean, and buttery roe cultivated from a crossbreed of sustainably farmed sturgeon. Originally, he paired it with asparagus, razor clams, and beurre blanc; however, subsequent preparations have substituted spinach for the asparagus and smoked butter for the beurre blanc. The razor clams, likewise, were exchanged for geoduck and Hudson Canyon scallop at various points. Nonetheless, those slender bivalves have consistently reappeared as part of the recipe (including your most recent meal).

No matter the exact composition, the dish has always aimed for the same balance of flavors and textures. The caviar is loosely shaped into a quenelle and placed just off the center of a slightly concave, very shallow plate (most recently replaced by a deep bowl). Curls of spinach nestle up against the roe, obscuring the deposit of shellfish located underneath. A healthy drizzle of the smoked butter drips across the leaves and forms a halo around each of the ingredients. The presentation is completed by an assortment of tiny white flowers, whose color pops against the assembled green and golden tones.

Attacking the dish, you aim first for the caviar. Tasted alone, the Golden Kaluga emits a pleasing pop. It displays notes of butter with a hint of earth that melds beautifully with the smoky character of the accompanying butter “sauce.” The spinach, which has only barely been wilted, envelops the roe and further accentuates its texture. The greens underscore the mild earthy flavors but also lend the plate a bit of sweetness. That matches up beautifully with the hidden layer of bivalves. The razor clam, geoduck, and scallop—no matter which appears in a particular preparation—lend the dish a second salvo of sweetness, butter, and brine backed by a succulent, meaty quality. The small pieces of shellfish sneak onto the palate almost imperceptibly, ensuring the caviar itself is not overshadowed. Presenting this course in a bowl, as has recently been done, helps guests form more cohesive bites laced with a greater volume of the smoked butter.

Overall, the dish strikes you with its savory power. The many sources of buttery flavor are moderated by smoke, earth, sweetness, and brine so that they develop a layered, multidimensional character. Still, there’s a weight to the combination of caviar, spinach, and clam on the palate that matches all the intensity. This combination forms a dream pairing with a ripe, round, and nutty multi-vintage Champagne (like the Laurent-Perrier Grand Siècle that McManus has chosen).

However, you think the dish sacrifices a bit of finesse in its bid to blow guests away. The intensity of flavor is sure to convince caviar skeptics (who have come to view the roe as little more than a bland, solely textural bauble), and it will impress just about every diner the first time they taste it. Yet, with repeat exposure, the character of the Golden Kaluga recedes as the butter and salt come to dominate your impression of the composition. What is pleasingly rich suddenly seems plodding, and, surely, this is not a problem that most diners will ever encounter. But it speaks to how a certain balance of flavor, a novel engineering of ingredients, may fade. The caviar is complemented by its accompaniments but does not deliver the kind of complexity that makes you want to come back over and over.

The next dish centers around hiramasa, a farmed “true” yellowtail amberjack (also known as a yellowtail kingfish) from the Southern Ocean. This piece of seafood is a cousin to the highly-prized Japanese amberjack (also called hamachi when farmed or buri when wild) but remains highly regarded in its own right.

Though the hiramasa’s serving vessel has changed over time, the preparation has remained consistent. The fish is cured in sake, sliced sashimi style, and twirled around the center of a bowl. It is surrounded on both sides by overlapping slices of radish that form clever faux scales. The vortex is garnished with strands of shio kombu (kelp simmered in a soy sauce mixture then dried), pearls of finger lime, and sesame seeds. It sits in a light dressing made from Fuji apple (identified on one menu as the Senshu variety) and dotted with blobs of olive oil.

Using chopsticks, you pull a piece of the hiramasa and its double-sided slices of radish out from the dish’s central structure. Along with them come some bits of the shio kombu and small flecks of the other garnishes. You dunk it all in the apple liquid then slide it onto your tongue. With each chew, the crisp crunch of the radish yields to the firm flake of the yellowtail. The finer crunch of the dried seaweed, finger lime, and sesame comes through towards the end, serving to contrast the smoother textures at the forefront.

The dish is really defined by the apple element, which invigorates the other ingredients with a burst of acidity and sugar. This fruit component enhances the latent sweetness of the hiramasa, whose clean (but rich) character is free from any jarring fishy notes. The apple also melds well with the moderating notes drawn from the tart finger lime and cleansing radish. The yellowtail’s natural umami is complemented by the shio kombu and sesame, but it ultimately takes a backseat to the aforementioned sweetness. Given the intense savory notes of the preceding caviar dish, that might be a good thing. Surely, the predominant apple notes form a stellar foil for a glass of Riesling (McManus’s favored pairing). You’ve even gone out of your way to bring your own bottle (via corkage) to appreciate alongside this dish.

But, in a manner reminiscent of the caviar preparation, your perception of the dish ultimately becomes defined by the apple rather than the nuance of the hiramasa. Of course, once more, the preparation stuns with its intensity the first time you taste it. Once more, it’s a surefire crowd-pleaser. However, with repeat exposure, the fruit’s encompassing sweetness slowly shuts the other flavors out. It lacks a concomitant umami quality to stand up to the apple and assert the fish’s flavor. Thus, the preparation starts to feel more like a fruity palate cleanser, a vehicle for Riesling, than a striking expression of sashimi.

Moving on, it should be noted that the langoustine dish you described as part of Oriole’s opening bar bites once appeared, at this point, as part of the sequence of courses served upon reaching the table. Given you have already described the item, you will not retread the same ground. However, it is worth pointing out that the Asian pear component took the place of a similar dressing once made from Korean melon. Otherwise, the version of the langoustine dish served at the bar really has represented its finest form. Porting the crustacean to the beginning of the meal has allowed it to shine. At the same time, the move emphasizes that the opening snacks are not really frivolous “bites” so much as full expressions of the kitchen’s know-how worthy of being served atop the dining room’s white tablecloths.

The next dish has held its place on the menu across all of your visits but has also shown some slight variation. Nonetheless, it has always steered the meal back towards decadence after the more cleansing tones of the apple-charged hiramasa.

The preparation revolves around a mushroom custard made, originally, with the coveted matsutake but, more recently, using the similarly prized lion’s mane variety. The dish has also always featured black truffle (Périgords when in season), which, in the time before the Tuber featured as part of the bar bites, ensured that the luxury totem was represented on the menu. On the first couple occasions, the two ingredients were joined by ribbons of zucchini and leaves of tarragon. The latter element would remain in a reduced form, but the former would see itself stricken in favor of foie gras. It’s a change that, apart from standing in the shadow of that excellent duck liver bite at the pass, has tilted the dish decidedly towards the rich, luxurious side.