After spending time with two concepts that tickled the national press in 2023, you turn your attention to a restaurant that—having opened at the tail end of last year—seems poised to do the same in 2024.

In Akahoshi Ramen, you discern some of the same narrative threads that so distinguished Daisies “2.0” and Thattu. Namely, you find a chef-owner driven by obsession (not with farm-to-table pasta or Keralan cuisine but with those titular noodles in broth) to leave the corporate world behind and try his hand at running a kitchen. Along the way, collaborations and pop-ups were conducted to fuel the fire of that passion. And, upon opening, you also see another instance of the “20% service charge in lieu of a tip” model that, in the wake of the One Fair Wage ordinance (and corresponding phase out of subminimum wage for tipped workers), positions these concepts as standard-bearers for a new approach to labor compensation.

While noting these shared details—the kind that make for easy marketing fodder and friendly press coverage—may be instructive, Akahoshi Ramen cannot be reduced to any simple blueprint. The restaurant embodies a singular story the likes of which you have never quite encountered in Chicago dining. You have seen celebrity chefs and owners before, as well as first-time proprietors and cooks who trace a circuitous path toward realizing their dreams. You have witnessed the most flamboyant of gimmicks and the quietest expressions of craft compete for consumers’ attention. Opening a ramen shop as a second career is, by comparison, in no way beyond the pale. But, in Akahoshi, you find a vision of the future.

The concept’s popularity is not undergirded by clever branding or a CV that touts Michelin stars and appearances on cooking competition shows. There is no sense of diversity, the exotic, or legitimate cultural exchange to fetishize here. Rather, this restaurant represents the realization of a decade of internet fame—of recipes cultivated and shared via online forums and the construction of “expertise” by participation in (and moderation of) an amorphous community of connoisseurs.

Typically, the line between chefs and their “foodie” admirers is not so blurred. The former group runs its kitchens while the latter group shows up, spends its money, and raves (or whines) about the experience online. Likewise, while the most prolific posters of recipes and other content creators may sling sponsors’ products, they tend not to cross the boundary into professional cooking. The demands of running a restaurant, assumedly, would inhibit interacting with their digital community and invite scorn from customers who are now actually tasting what they previously only read or watched you make.

Nonetheless, the risk of transitioning into ownership for this kind of influencer also carries its own rewards: to live the dream of being the kind of craftsperson you have so long admired and sharing your passion with the public. It means walking the walk in reality—not just hyperreality—and earning the respect of an industry that, from their positions behind the stove, may be inclined to view social media mavens as mere gadflies. It means, in the best case, consolidating that internet fame and transforming it into real culinary esteem on the back of a loyal population of aficionados—many influencers in their own right—who are ready to support and advocate for the fruits of so many years of content.

Though this may seem like an unconventional path on the surface, you think Akahoshi Ramen represents an emerging strategy for at-home specialists to turn their “foodie” identity (one defined by its conspicuousness and the assertion of “expert” knowledge over others) into a real livelihood. Doing so, they may sidestep the hard knocks to be taken and dues to be paid in favor of a personal, granular approach that wins future customers from the comfort of their own kitchen. Then, when it comes time to launch, these influencer-chefs can skip straight to opening their dream restaurant atop a readymade reputation. The existing fans then help deliver the initial buzz, which is translated to more traditional media coverage and—before you know it—real eminence within the chosen genre. This is all fine and dandy (and, dare you say, deserved) when the end product matches expectations and competes in good faith with concepts that do not benefit from such a built-in audience.

Evaluating Akahoshi in relation to Chicago’s existing ramen scene will form the core of this article, for it does not matter whom you are or how you came to the industry if you deliver the goods. Just the same, subverting the “apprentice/chef” model that has defined this and other culinary crafts invites its own criticism. What is gained—and what is lost—by the emergence of a new breed of restaurateur that masters digital marketing rather than take lumps from an actual master? Does such a shortcut realty supercharge creativity or simply work to secure the kind of consistent patronage that, right or wrong, ultimately determines success in this fickle industry? Does it matter if everyone leaves full and happy?

You will address these questions later on, but, first, it may be instructive to trace the story of the little ramen shop with a big online presence.

Akahoshi Ramen is the creation of Mike Satinover, an Oak Park native who was first exposed to the dish (if you “don’t count the 99-cent noodle packets”) when visiting Mitsuwa Marketplace (in Arlington Heights) as a kid. There, at a food court stall named Hokkaido Ramen Santouka, he would order the miso because “it was the only flavor…[he] recognized.” It tasted familiar “but leagues better” with “depth, nuance, viscosity, [and] punch—traits…[he] never knew were possible in Japanese cuisine.”

Cooking would become “an on and off career possibility” for him, with Satinover working as an “unpaid stage” at an “upscale Italian spot for around a year” during high school. Putting in “20-40 hours a week,” he “kinda fell out of grace.” However, many years later, Satinover would blame a “negative workplace culture” that compelled him to “circumvent any toxicity associated with restaurant kitchens.”

(For what it’s worth, a later stage at “a pretty well known ramen restaurant here in Chicago” in 2013 also “didn’t really work out.” Despite being just 24 at the time, Satinover claimed he was “a bit too old and untalented” to succeed there despite his “passion” for the dish.)

While studying business at the University of Wisconsin-Madison, Satinover specialized in marketing, international business, and Japanese. That led him to participate in a short-term exchange program at Hokkaido University from 2009-2010. There, in Sapporo (a place he now calls his “3rd home”), Satinover had his “first true exposure” to the kind of miso ramen that won his heart. Terming himself “a miso ramen fiend,” the exchange student began eating the stuff “several times a week, easily” at the “2,000 shops” in the city “slinging noodles.” He “bought multiple guidebooks,” “tried one,” “tried the next,” “tried the one after that,” and then “started going to multiple shops a day.”

Satinover earned a reputation on campus as “that guy who is always going out to eat ramen” and eventually “launched an independent study” through his program. For his research, he went “interviewing cooks, looking at restaurant practices, seeing methods, [and] discussing the history and culture” of the dish. By the time Satinover returned to Madison, he had “tried more than 100 different ramen shops.”

Back at school, “there was like one ramen restaurant, and it was awful.” Across America, the dish’s popularity “was starting to pick up,” but the “David Chang-ian interpretations” weren’t anything like he had seen in Sapporo: the menus were “expansive—as if trying to please every customer,” the ramen “took forever to make,” and “diners took even longer to eat it” (“slowly chewing…until the bowls turned cold and lifeless”). Satinover “had gone from eating this food that…[he] loved…to not having it ever,” and “this desperation led him to try cooking ramen at home.” Despite being “a pretty decent home cook” and feeling “pretty confident,” Satinover “abysmally” failed. The results were “utter trash, horrible concoctions” that took “years” before really starting to “click.”

He blames a lack of “many ramen recipes online” (either in English or Japanese) along with the fact that “ramen chefs are notoriously secretive about their techniques” for those early struggles. However, the challenge “was enticing—really enticing” and represented the “first thing” he felt he “didn’t understand.” This “addictive” process meant “a lot of room to fail and a lot of room to learn.” Soon enough, Satinover began “hosting small groups…including a number of friends who had also lived in Japan and missed the ubiquity of good ramen” to share in his recipes. In 2014, after four years of experimentation, he was ready to start posting his bowls “on the internet to see what people thought.”

Satinover did so through a blog titled “The Ramen Journal,” which was devoted to “exploring the possibilities and techniques of this wonderful” and developing “methods to make the dish at home.” He also hoped “to tackle the astounding amount of misinformation in the US” surrounding the form. The site was active for about half a year, during which Satinover discussed his first ramen attempts, broke down his failures, described how he prepared the dish for six of his friends at a time, defined certain styles, and offered recipes alongside a collection of pictures.

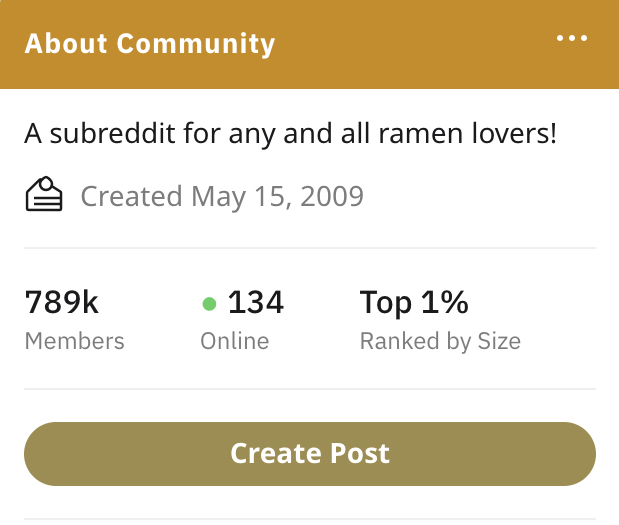

In truth, “The Ramen Journal” was really an extension of Satinover’s posts on Reddit’s /r/ramen subreddit. There, under the username “Ramen_Lord,” he had been “well received” since joining the community in 2013. In fact, he quickly became one of its moderators and a friendly presence who both shared his own bowls and helped to troubleshoot others’ recipes. This extended all the way to helping with ingredient sourcing, offering historical context, and providing excruciating technical detail. The separate blog was intended to be a home for “all of the information” he wanted to share that might not fit in the context of a Reddit post. However, as it happens, engagement on “The Ramen Journal” was rather low, and /r/ramen—where “everybody else was interested” in what Satinover was doing (something he termed “inspiring”)—would prove his permanent home.

As moderator for some 11 years, Satinover saw the subreddit grow from 15,000 to a total of 789,000 subscribers today. Some of this, no doubt, is the product of ramen’s burgeoning popularity during the course of the decade. When he started, Satinover felt that ramen “still kiiiiind of has a stigma as ‘that college instant food you buy when you’re broke’” and wasn’t sure “appreciation…has grown to a sustainable level in the US.” Later, he would also ask “is ramen in the US here to stay? Or has it become the ‘next big thing’ like cupcakes or cronuts?” There was a worry that the dish’s popularity was “a fad we’re experiencing” and that “the level of appreciation for it will die off in a few years” rather than becoming “an actual staple” like “sushi or pasta.”

Nonetheless, it is also hard to understate Satinover’s influence on the community (both the subreddit itself and the wider digital world of ramen lovers). Looking back, he didn’t really know why he started posting his bowls online. Satinover was “just a kid who wanted to bask in the glory of noodle soups,” one who “maybe” was “stressed out” because he “was unemployed and needed an outlet for creative projects” or just “homesick for Sapporo.” Ramen was “a bit more emotional” for him than he’d “like to admit,” yet engaging more deeply with the craft alongside other users who “just like good, cheap, but properly executed food” would ultimately lead to the creation of his own shop.

As moderator, Satinover would continue being an invaluable resource and content creator for his forum. However, he would also work to define and protect the subreddit’s culture (and, by extension, that of the online ramen community). This involved bridging the divide between users seeking “interesting, creative ways of using instant noodle”” and those “more interested in the authentic dish that has captivated Japanese (and foodies around the world) for almost a century.” These two camps “bashing the other side” was said to cause a fear of making new contributions to the community, with Satinover asserting “it takes courage to post in a subreddit and that courage is worthy of respect.”

Along those same lines, he would take a stand against “exceptionally rude posts,” “toxic” comments, “low effort memes,” “shitpost[s],” and simply “being a jerk” in order to “foster an atmosphere that cultivates quality content” (i.e., that which “encourages making ramen, because that’s how you expand knowledge about the dish”). The overall philosophy was: “it’s just food; if you don’t like the content, downvote and move on. No need to be so belligerent.”

In these early stages, the future Akahoshi owner would be careful to clarify he is “not a cook, just a home cook obsessed with ramen.” (Also, despite the detailed recipes and technical explanations, “I have no scientific background. I’m just a nerd.”) Satinover was “not really in this to make money,” and the most he “thought about ever selling ramen” was through “something like a popup” in his “dinky apartment.” When “shamelessly” plugging his recipes, he would declare “100%, I am a shill lol” while clarifying “if I were a good shill, I’d probably make some money on this. But I only post for the love of noodles.” This would inform a moderation policy where “generally we don’t like folks using Reddit to drive traffic to their own website (that’s self promotion and not really what Reddit is for).”

That being said, Satinover was never afraid to opine about Chicago’s ramen scene. When High Five Ramen was getting ready to launch, the moderator admitted he was a “tad scared” given Hogsalt founder Brendan Sodikoff only “studied ramen in Japan for a whopping ‘two weeks.’” However, when Zagat posted an article on “7 New Bowls of Ramen to Try This Winter” in Chicago, Satinover admitted High Five was “hands down the best in the immediate city” (though could be “disgustingly hot” in an “unenjoyable, bad way”). Still, he found the list “mildly infuriating” with “almost none of these places” coming close to “the level of the ramen shops found in LA or NYC.” A Thrillist list of the “Best Ramen in Chicago” (updated since its original publication in 2014) also had Satinover feeling “lukewarm to say the least.” He felt “many of the shops here are legitimately poor quality” and, more particularly, that “no one on this list makes a solid bowl of miso.” Overall, most ramen in Chicago could be described as “tonkotsu heavy, thick lard bombs with lots of gelatin,” with his “favorite place” being “my house.”

Satinover reserved the harshest scorn for Furious Spoon, which he claimed he “really enjoyed…back when they opened.” He even “supported their kick starter.” However, their tsukemen was labelled “absolute trash” with broth that was “tepid, a mess” with “no complexity or overt flavor to speak of,” “nothing to please the palate,” and an “extremely off-putting” character that was “borderline gross.” The noodles “only further destroyed any semblance of flavor,” and the moderator called the dish “a travesty” that “sets ramen back.” He even asked the restaurant, “how did you fuck up so bad?” Years later, Satinover would continue to tell users “avoid Furious Spoon if at all possible” even if, at that point, he tried “not to bash any places in the city too harshly” given he was then “semi-involved in the ramen business via running an occasional popup.”

The moderator would even take aim at Eater host Nick Solares (somewhat ironically given the fawning coverage the publication would later grant him) for a video titled “World Class Ramen At The Click of a Button in Osaka, Japan.” Satinover said Solares “is full of pretentious over the top garbage” and that he finds “videos with him to be abrasive.” Something about him “just feels try-hard,” and that quality prompted a general admission that he sometimes feels like “foodies are bogus.” Instead, one should remember “food is subjective; enjoy what you like, that’s key. Don’t over analyze it.”

As Satinover continued to post his ramen, troubleshoot other users’ recipes, guide discussion, and moderate content over the years (and, correspondingly, as /r/ramen grew), he really began to settle into the “Ramen_Lord” identity. Satinover originally “wanted to be Ramen_God,” but the username “was taken.” Thus, the “Lord” moniker was born, a title he admits was “presumptuous” from the start. Still, on the subreddit, the moderator was not against playing up his self-proclaimed majesty when called upon to render a judgment: “I have been summoned apparently, lol,” “I have been summoned lol,” and “lol, guess I’ve been summoned” regularly prefaced such posts. Satinover also began referring to himself in the third person: “alright, I’m going to write a typical “Ramen_Lord talking forever about ramen” post.”

To be fair, the subreddit’s users were happy to fuel the fire with a bit of roleplaying: “He has touched us with his noodley appendage. We are blessed,” one wrote, while another declared “We’re not worthy! We’re not worthy!!!*kneels and bows down deep kowtowing with outstretched arms.*” Though this kind of humor is thought to be cringeworthy by some within the wider Reddit community, it forms one of the website’s long-running codes of interaction and a path toward earning the upvotes, social standing, and power some prolific users desire.

When someone like Satinover—through consistent engagement with his subreddit and an acknowledged ramen expertise across several subreddits—cultivates this status, an ingrained internet fame is formed (and is maintained so long as he keeps his account and its accompanying karma). That attention might naturally lead to a sort of parasocial relationship forming in users who see the “Ramen_Lord” persona as a helpful, knowable, steadfast “celebrity” friend. By interacting with Satinover in the fawning manner seen above, they reflect some of his fame back onto themselves while being rewarded (via upvotes) by the onlooking community. This cycle serves to condition mimetic behavior in others (if they seek the same rewards) while perpetuating the power user’s fame and cementing the loyalty of their fans.

All of these factors—Satinover’s progression as a cook, a growing appreciation for ramen across the United States, the growth of the /r/ramen subreddit, and the rising internet fame of the “Ramen_Lord” persona—came together in 2017. At that point, the future Akahoshi owner’s reputation began to be transplanted from social media into the mainstream. First, in January, Serious Eats published “Obsessed: We Talk to Reddit’s /u/Ramen_Lord.” Therein, Satinover was profiled for creating “one of the best English-language resources for good ramen recipes” and given a chance to expound on his personal history and culinary philosophy while offering some technical tips. Saying “sorry for the shameless self promotion,” the moderator also shared the piece on /r/ramen and noted, though the article was “borderline embarrassing” for him, that he “owe[s] so much to this subreddit.”

In October of 2017, Satinover would be featured by the Chicago Tribune in a piece titled “Here’s the best ramen in Chicago — and you’ll probably never try it.” This time, he was ranked as the master of the form relative to the “17 ramen joints in Chicagoland” the author had sampled in the hope of “uncovering some hidden gem that would triumphantly put the Midwest on the map.” Satinover was again profiled—both personally and for his work under the “Ramen_Lord” persona—while being positioned as an expert “earnestly addressing issues with ramen that most people on Earth have never considered.” The author also recounts attending “three of his ramen nights” over “the course of the six months” that he’s known him, affairs that are described as “mostly informal” where “no money changes hands” as bowls are put together two at a time. Ultimately, the article wonders “shouldn’t the rest of Chicago get to try the best ramen in the city?” But Satinover is said to be “actively against opening a restaurant” because, despite “calculating how many bowls he’d have to sell to make a profit,” he ”doesn’t think it would work.”

The Tribune piece was posted on /r/ramen (this time by another user and not a “shameless” plug from the “Lord” himself), and the “overwhelming reception” prompted Satinover to plan a subreddit meetup. Toward the end of November, he would also pop up for a week at Ramen Lab by Sun Noodle in New York City. Satinover recounted 15 of the lessons he learned from the experience, which included: “Nothing can prepare you for the workload,” “We learned a lot about the health code and had to adjust our menu to comply with standards,” “Prep as much in advance as you can,” “Keeping the broth piping hot is actually challenging,” “Tickets and expediting orders are tricky for newbs,” and “Ramen Lab was probably the hardest thing I’ve ever done, and I hate that it’s over already. I want more.”

To that point, 2018 would see Satinover host a series of nine pop-ups at Paulie Gee’s Logan Square during the course of the year, 60-70 seat ticketed affairs that sold out in as little as 10 seconds. These not only allowed him to share his craft more widely than the intimate home setting previously allowed but to debut new, experimental recipes for ramen. They also marked the unveiling of the “Akahoshi” brand name: a word that translates to “red star” and references the symbol’s shared appearance on the flags of Chicago and Hokkaido (the two places that have shaped the concept). 2018 would also see Satinover host one of these pop-ups at Momotaro while returning to Ramen Lab for another weeklong engagement as well.

Additionally, the year saw him return to Japan “for the first time in 8 years,” during which he “ate 22 bowls of ramen in 6 days” (sharing thoughts on the experience with his followers). Satinover also began contributing a series of articles for The Takeout (each focused on a particular element in the creation of ramen) that he, once again, “shamelessly” promoted on the subreddit.

2019 would see more pop-ups at Paulie Gee’s throughout the year. However, Satinover would also bring his ramen to Atlanta (at Brush Sushi), Chicago’s Baconfest, the Let’s Make Ramen cookbook release party (a book in which he also features), Nashville (at The Green Pheasant), Split Rail, and New York (at Shuya Cafe de Ramen, which the “Lord” also “shamelessly” promoted on his subreddit).

2020 would see Satinover kick off a series of collaborations with Flat & Point—beginning, in February, with his very first “Tonkotsu bash.” However, with the dawn of the pandemic, he quickly pivoted toward selling $20 “Akahoshi Miso Ramen Kits” at the restaurant for customers to prepare at home. Satinover sold this same item at the Cookies & Carnitas Social Distance Market that summer before finishing out the year by offering a few additional styles of kit (i.e., “Jiro,” “Fall Shoyu,” and “Akayu”) every month or two back at Flat & Point. September of that year was also notable for a “Secret Kit” series of four experimental bowls like “Homemade Miso,” “Roasted Bone Tonkotsu,” and “Cement Ramen.”

All that said, 2020 was most distinguished by the release of The Ramen_Lord Book of Ramen in July. A collaboration between Satinover and his twin brother Scott, the work “isn’t a cookbook, per se” but something “meant to break apart ramen into its five components and explain them thoroughly, to help amateurs and cooks understand the components of the dish and to make more thoughtful composed bowls.” There were, indeed, recipes to follow—a summation of the work Satinover had been doing for 10 years—yet they were characterized as “by no means the be-all-end-all of ramen.” Rather, the authors would hope to update the cookbook over time and continue “to give it away for free”: “Why hoard the info right?”

To you, the most interesting portion of the book arrives under the “Beyond Salt and Flavor: Adding Umami Concepts” section. After discussing natural sources of glutamic acid in ramen like “soy sauce, kombu, and miso,” Satinover advocates for the usage of a “certain infamous ingredient” called monosodium glutamate (or MSG).

In truth, the author has recommended this food additive on Reddit and in his recipes for more than a decade. He has little hesitation about doing so. For, as a passage labelled “A Personal Notes on MSG” explains: “I have no problem with MSG. I love MSG actually. In small amounts, it greatly increases the savory characteristics of dishes, amplifies flavors, and makes ramen taste more cohesive. It also can help balance off-flavors, which is why most Tonkotsu shops in Kyushu rely heavily on MSG in their ramen.”

Satinover even preempts some of the common criticism levied against MSG, noting that fear of health risks is “rooted in a controversial history associated with slander against Chinese restaurants” while arguing “glutamate is a naturally occurring amino acid we make and use in our bodies.” The author finds “there is nothing remarkable about the glutamate in MSG, and certainly sodium isn’t dangerous” so “using a little MSG here and there” does not pose “any significant problems.” Ultimately, “MSG helps make food delicious,” and Satinover’s goal is always “first and foremost to make delicious ramen.”

Now, you recall that Satinover admits he has “no scientific background,” and his intentions are probably in the right place. The defense of MSG has been spurred by a larger defense of Chinese cuisine against perceived racism, with supporters of this argument rightfully asking why one genre of cooking is singled out for scorn while the additive is pervasive across many beloved American processed foods (e.g., condiments, chips, frozen meals, deli meats, and cookies). Satinover is also right to note that “the science behind the health scare is bad”: MSG has not been found to cause headaches or other “Chinese restaurant syndrome” symptoms (except when ingested in large amounts in the absence of food).

MSG’s effect is actually more insidious. This form of glutamic acid is, indeed, naturally occurring, and “humans have evolved a very sophisticated detection system in our mouths for these molecules because they signify easily digestible protein—not the protein of raw meat, but the protein of perfectly aged, cooked meat” along with things like “breastmilk, seaweed, tomatoes, scallops, anchovies, cheese, soy sauce, cured ham and many more foods.” However, extracting MSG from its whole-food context and transforming it into a powdered additive subverts this process.

Additive MSG sends “a signal to your brain telling you this is nutritious,” but “when you digest it there is nothing there—so you keep eating.” Satinover asks “why do we think it’s ok to adjust salt and sweet flavors in a dish, but not adjust umami similarly?” However, “processed culinary ingredients” (like “oils, lard, butter, sugar, salt, vinegar, honey, [and] starches”) are categorized (by the Nova classification system) as “traditional foods that might well be prepared using industrial technologies.” MSG—and its “savoury umami flavours”—may exist (as a whole food) in this context. But the powdered substance Satinover is advocating for fits under the category of “ultra-processed food” (UPF): “formulations of ingredients, mostly of exclusive industrial use, made by a series of industrial processes, many requiring sophisticated equipment and technology.” These “processes” include “the fractioning of whole foods into substances” and “chemical modifications of these substances,” which aligns with the neutralization, decolorization, filtration, and crystallization procedure outlined by MSG’s manufacturer.

UPFs are products of industrial processes that rid the compounds of their supporting nutrition—that which humans evolved to recognize and to prize in the first place. Such additives, stripped of “thousands of chemicals [that] bring health benefits” then used for flavor enhancement, “hijack…taste interactions” that signal you should eat this food without providing the expected benefits. The rewired “circuitry of desire” overrides feelings of “physical fullness,” inducing consumers to eat endlessly—and addictively—in search of a nutritional density that is not actually there. This sequence “disrupts our multi-million-year-old network of regulatory neurons and hormones” and is abused by companies looking to sell a steady supply of increasingly hyperpalatable products. UPF “isn’t harmful simply because it’s fatty, salty and sugary”: “it is the ultra-processing, not the nutritional content, that’s the problem,” and UPF has been associated with an increased risk of death, obesity, cardiovascular disease, cancers, type 2 diabetes, high blood pressure, fatty liver disease, inflammatory bowel disease, depression, and dementia.

Used in small amounts to flavor a ramen that is otherwise made from whole foods, MSG powder poses no direct health risk. Satinover says the additive “is basically mandatory for balance” in some recipes, and that shops only “brag about not using it” because of “how rare a lack of MSG actually is.” He even says “if you’ve eaten ramen in Japan, you’ve probably had MSG.” However, Satinover himself stresses that ramen is “too young to have a culture” and “doesn’t have a lot of rules, unlike more traditional foods from Japan.” Thus, despite the convention of Japanese chefs adding MSG to their ramen, this is a practice that deserves scrutiny. It does not reflect any real history or heritage or “authentic” expression of culture that demands respect (if not total fidelity to the same methods). Rather, the usage of MSG is a contemporary, commercial phenomenon meant only to make the preparation of hyperpalatable food more convenient.

MSG producer Ajinomoto touts the product’s “safety” and “role in the diet,” particularly that it has “2/3 less sodium than table salt” and “can be used in the place of some salt in certain dishes to reduce the sodium by up to 61% without compromising flavor.” However, “it’s perfectly possible for someone to eat a high-UPF diet that is actually relatively low in fat, salt and sugar.” And it is by fixating on discrete nutritional benefits (like the need for less salt) that these companies distort the larger picture: additive MSG causes you to eat more of food that is nutritionally depleted (relative to the amount of glutamate being signaled to the brain) and to keep eating until there is nothing left.

In the manner, Japan, like the United States, has been victimized by the industrialization of its food system over the past century. Although “the prevalence of overweight and obesity in Japanese adults is rather low in international comparisons,” their rate of obesity has more than sextupled in men and more than doubled in women since 1976. The prevalence of overweight in adult males has also doubled over the same period.

Additive MSG, especially in the context of ultra-processed food, is best thought of as a mildly addictive substance—one that encourages overeating—rather than a harmless seasoning. It is “a cheat” (despite Satinover claiming otherwise) because it chemically alters a dish that is presented as being entirely “made in the restaurant” (i.e., homemade, wholesome in perception) for the sake of making it hyperpalatable and more intensely craveable. It represents nothing but a cheap shortcut to attaining a fleeting umami that perverts the very purpose (vis-à-vis the brain) of the flavor to begin with: signaling nutritional density.

This may seem like nitpicking, but Satinover spent more than a decade working as a marketing research consultant for Kantar, a company that celebrates its work for clients like Kraft Heinz, Nestlé, PepsiCo, and Unilever. These corporations are notorious purveyors of UPF and have cultivated “extensive relationships” with organizations like the Academy of Nutrition and Dietetics in order to undermine national food policy that might harm their business interests. These brands also fund and partner with non-governmental organizations as a form of “healthwashing” that yields good publicity for “weak promises and delaying tactics as they fight for ‘voluntary’ measures to challenge what they do.” When you consider that ultra-processing also involves “more indirect processes” like “deceptive marketing” Kantar seems to facilitate not only the proliferation but, in a sense, the very production of UPF.

Ultimately, this tangent means little in the context of Akahoshi Ramen. You have no window into the nature of Satinover’s work for Kantar or his complicity in promoting commerciogenic obesity. You just know he shills for MSG in the same manner the powder’s manufacturer does (i.e., conflating naturally occurring glutamates found in whole foods with a concentrated industrial product, focusing only on metabolic effects rather than those related to addictiveness and public health). Satinover simply recommends its use to his followers (calling it “basically mandatory” from his position of authority) and puts it in the bowls he serves at his restaurant. He acknowledges that, in Japan, “new wave shoyu” has opted “for technique over variety and quality ingredients over chemical seasonings or MSG.” However, while “charging a premium” and advertising that “we make everything in the restaurant” (while “most shops don’t”) with “real ingredients,” Satinover still chooses to use MSG. He even makes use of a mirin alternative called Honteri, substituting traditional rice wine for a UPF containing glucose syrup. Satinover willingly puts out an ultra-processed product—one that may help him sell more bowls at a “healthy margin”—while claiming, much like the multinationals, that he only wants to “make food delicious.”

Satinover says he gets “a little weirded out when a place has ‘secrets,’” believing any restaurant that does so “has something to hide.” In fairness, he has been honest about his MSG use from the beginning (though you suppose that is easy when cloaking yourself in the same “scientific” arguments utilized by UPF producers) and accommodating (though not always) of substitutions to his recipes in line with personal preference. You do not doubt that other ramen shops in town are using MSG without a second thought. So, taking this all into account, Akahoshi must simply be judged relative to its overall value proposition: what is being advertised (explicitly or implicitly) and what is being delivered? If the best ramen you’ve ever tasted benefits from a dusting of MSG, who could really complain? If the most hyped ramen you’ve ever sampled proves itself to be nothing special, just why might it be laced with that “infamous ingredient”?

Returning to the story, 2021 would see Satinover continue hosting pop-ups at Flat & Point, with ramens like “Duck and Negi Shoyu,” “Jiro Inspired,” “Soupless Mazemen,” “Mazesoba,” and “Tonkotsu” on offer throughout the year. In November, he also partnered with the Chicago Reader and Maa Maa Dei for a “Monday Night Foodball” pop-up at The Kedzie Inn. Finally, in November, the “Lord” would travel to Boston for a three-hour engagement at Yume Wo Katare that he noted, “perhaps,” would be the “start of another…world tour.”

That being said, 2022 would proceed in a similar fashion. Satinover started the year off with yet another collaboration at Flat & Point, serving “hits” like “Shoyu” and “Soupless Tantanmen.” However, April would see him bring the “New Wave Shoyu” style of ramen to Kumiko. There, a long line “created some serious hype” (the kind Satinover admitted it would be “disingenuous” to say he “didn’t like” while admitting detractors were free to give him “the middle finger” and call him “a clout goblin”). July would see another “Monday Night Foodball” collaboration with the Chicago Reader, but August would be marked by Satinover’s first pop-up at Perilla. There, alongside Umamicue, he served a “’Junk’ Style Mazesoba” with smoked brisket that was later followed, in October, by a collaboration with YouTuber Alex Aïnouz on two French/Korean/Japanese “Mega Mash Up” bowls. Finally, in December, Satinover would partner with SuperHai to bring “Junky Mazesoba” and “Chicken Paitan” to Ludlow Liquors.

2023 would prove to be a banner year, with Satinover—on the occasion of his birthday—declaring “34 will be the best year of my life. The most important year of my life. A completely life-changing year.” For once, he was “looking forward to…[his] life path” and to being “a part of the glory of this city [Chicago],” which he characterized as “a brash, imperfect, towering monolith of horror and delight, never taken seriously by anyone until it’s too late.”

To start the year off, Satinover would host his final pop-up at Dorothy’s (the concept that replaced Flat & Point) in January, serving “Akahoshi Miso” and “Soupless Tantanmen.” However, by the midpoint of February, he had a larger announcement to make. Satinover would be opening a restaurant under the Akahoshi name serving “a handful of ramen bowls, rice bowls, and beverages” (and “not much else”). His goal would be to “heavily fixate on quality with a small but exceptionally executed menu,” and he could also share that “the lease is signed, the designs are planned, [and] we are well on our way.”

You might remember that Satinover was “adamant he didn’t want to open a restaurant.” It was explained at the time of Akahoshi’s announcement that his “apprehension had to do with the restaurant culture he experienced as a teenager,” where he “didn’t feel comfortable” and “felt like, fundamentally, the culture wasn’t good” for him. However, hosting pop-ups taught Satinover that “not all kitchens operated the same way,” “you don’t have to make it brutal or messed up,” and you can “decide the kitchen culture…[you] want.”

In truth, Satinover had softened on the idea of opening a restaurant as far back as 2018, when he responded to a user’s question (regarding a permanent location) by asking, “Y’all got $350k? If so I’m definitely down to open a spot. Restaurants are expensive!” Elsewhere, he noted that he had actually planned Akahoshi “for years and years” and was “very meticulous about the right location, space design, and business model.” The spot he had chosen offered “good rent” and a “pre-existing space with the right square footage and infrastructure in place.” Being self-funded, he “saved a solid 300k with the location,” which—being “very close to the California blue line”—would cater to the people from “the north/northwest side” who predominantly came to the pop-ups.

That February, Satinover could already reveal that his shop would be located at 2340 N California Avenue, joining “a burgeoning ramen scene in Logan Square” with “Monster Ramen, Ramen Wasabi and Furious Spoon [his favorite whipping boy] all nearby.” Rather than directly competing, the goal would be “to increase the appreciation of ramen” and “to increase the discussion” in order to help realize the genre’s potential (“so much more” than currently exists) in Chicago. Elsewhere, on the topic of competition (in the wake of Slurping Turtle’s closure due to the effects “competition” in 2019), Satinover would contend, “we’re talking one ramen shop next door. Is that all it takes? Be better than your competition.”

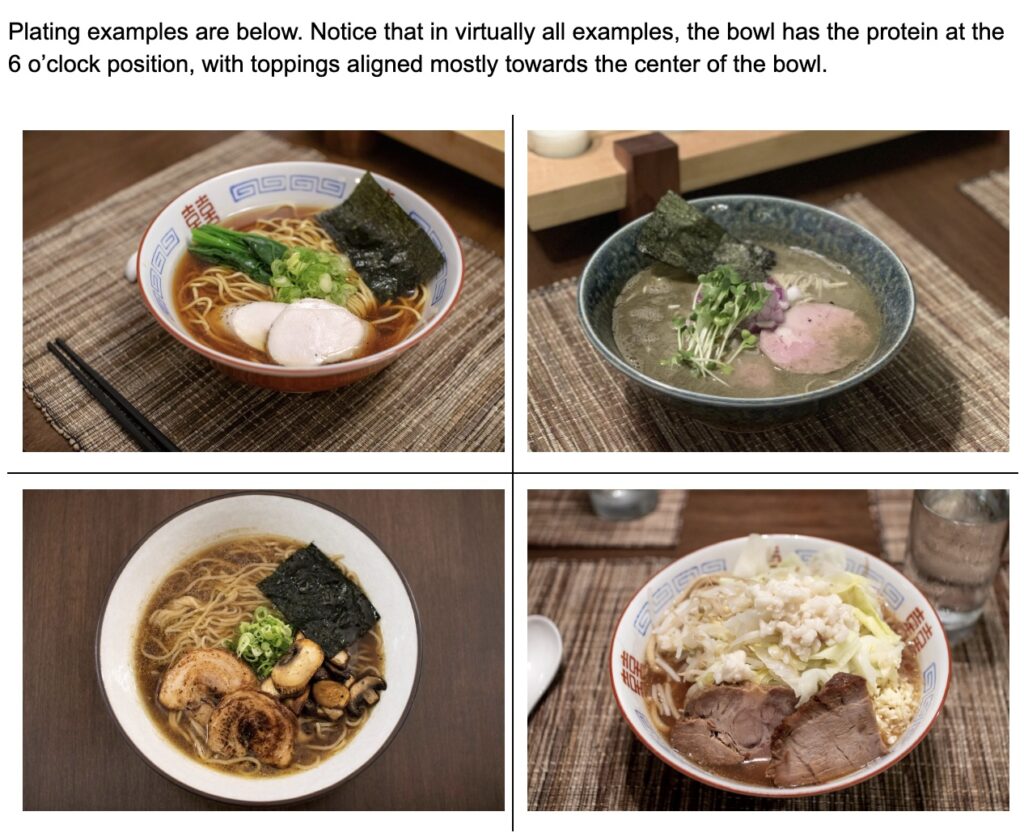

Further details provided at the time revealed that Akahoshi Ramen had tapped Siren Betty—whose credits include Claudia, Evette’s, Pistores, and Tortello—to design its space. Satinover “initially wanted to emulate the extremely close quarters seen at ramen shops throughout Japan,” but “Chicago’s building regulations would have required expensive construction” to make it happen. Instead, the room would seat “about 50,” with a six-seat counter facing an open kitchen, a few large booths and a massive communal table that can fit almost 20.” The menu, more specifically, would include miso ramen (“the miso ramen will exist forever”) and “probably” a shoyu and a tonkotsu. There would also likely be “two soupless styles of ramen” because “Chicago doesn’t know how great those can be” alongside rice dishes like chashu don (“featuring fatty pork”) and ikura don (“topped with salmon roe”).

Satinover would look to keep the menu “focused and brief” because he wanted “to make sure the ramen is the star” (unlike other ramen spots where “people write that they like the pork belly buns”). This would help him to “put out a consistent product” and, again, “focus on the quality.” “To be honest,” he would reveal, “I don’t have a lot going for me except for quality—that’s what people know about me. It has to deliver because if it’s not awesome, the business is not going to work.” To that point, Akahoshi “won’t serve the cheapest ramen,” but each component would be made “from scratch”: “the noodles, soup, tare, toppings and everything in between.” To do so, the shop would draw on “specialized equipment” like a “$40,000 noodle-making machine” that was “currently resting in his living room.”

Elsewhere, Satinover would confide that he doesn’t “want to put on this air” like he “know[s] so much.” Ultimately, he’s “a white guy making ramen, that is the dynamic of the situation” and he would “lean into that.” This could principally be seen when Satinover shared further details on Akahoshi’s design in July.

Noting that the ramen shop is “effectively” going to be his “home for the next 10-20 years,” the owner stated a desire for the space to be “mature yet approachable,” something he “would be proud of,” and a “deep representation” of himself. As opposed to other places that “can look junky” and “parsed together from scraps and ideas over the course of its life,” Satinover, knowing himself well, “wanted to go all in” on Akahoshi.

At the same time, he admitted he was “VERY aware” that there is a “target” on his back. Rather than liking to pretend that “everyone and anyone” will love him, Satinover was prepared for the “intense levels of scrutiny” opening himself up to the public would entail. In that regard, “decor is any easy place to target” given he is not Japanese. Still, the design would look to “pay respect to certain Japanese aesthetics” while retaining a level of “American-ness.” Satinover “did not want this to be a stereotype,” and Siren Betty’s work would be “fundamental to encapsulating this.”

The “meticulous and thorough” design process took “around 6 months” and came to center on three pillars: “Simple and Fun,” “Culinary Excellence,” and “Refined Imperfection.” These were billed as “symbols” of Satinover’s work, and they were translated through “lighting and atmosphere meant to highlight food and experience,” “distressed finishes to give the space approachability,” and a “buzzy and fun” space with “a big communal table, open to the kitchen, to show everyone exactly what they’re eating.”

Akahoshi’s construction would be completed in October, and Satinover began hiring ahead of a prospected late October/early November opening date. The owner wouldn’t be able to offer healthcare, but employees would be able to eat for free while earning “competitive” pay: $20-$24 per hour for cooks and $15 per hour for front of house (along with a proportion of the assessed service charge). Once again, he reiterated the desire “to make the absolute best ramen possible for…guests” with “from-scratch cooking” and “high levels of hospitality.”

Inspections would delay the restaurant’s launch until the end of November, when, after a short period of soft opening, Akahoshi formally opened its doors to the public on the 28th. Satinover would mark the occasion, just a few days later, by honoring the many people—designers, contractors, landlords, parents, chef-mentors, fellow Midwestern ramen makers, and his staff—who got him there. He also shared a quote from Grant Achatz on how the Alinea chef “seasoned food with ‘emotion.’” Satinover “used to find that bewildering” but finally got it: “Every bowl we put out here is a reflection of so much work from so many people trying to do the best they can, a reflection of memory, a reflection of ideal. The best cooking is always layered with this.”

Akahoshi’s reception was warm—if not feverish—from the start. By November 29th, Eater Chicago was ready to declare the ramen shop “Chicago’s Toughest Reservation” (with bookings, at the time, totally filled through December 29th). The article cites former Chicago Tribune food writer Nick Kindelsperger’s evaluation at the time of soft opening: “I’m not a food critic anymore, but this is the best ramen I’ve had in Chicago.” This testimonial, which Satinover termed “pretty wild,” was well timed with the journalist’s departure from the publication, for you might remember that Kindelsperger visited the Akahoshi owner’s home for “ramen nights” at least three times. No money changed hands, and it would be flagrantly unethical for a journalist to promote someone who repeatedly hosted them for free—even if Satinover shrugged off the idea of opening a restaurant at the time—were they still a member of the profession.

Elsewhere, it was revealed that, despite reservations selling out, Akahoshi was “serving up to 60 walk-in patrons per day.” Satinover was also praised for the “extreme transparency” he had shown in documenting the concept’s fruitions, including both “triumphs and trials” (like “failed pre-opening inspections”). On that topic, the owner termed himself “an over-sharer by design” and stressed that he’s “not a seasoned professional” and he’s “going to do some stuff” without knowing what he’s doing. Being straightforward, thus, would set “appropriate expectations.” The restaurant was “not going to be perfect” but “just needs to be done earnestly, honestly, and compassionately” to succeed.

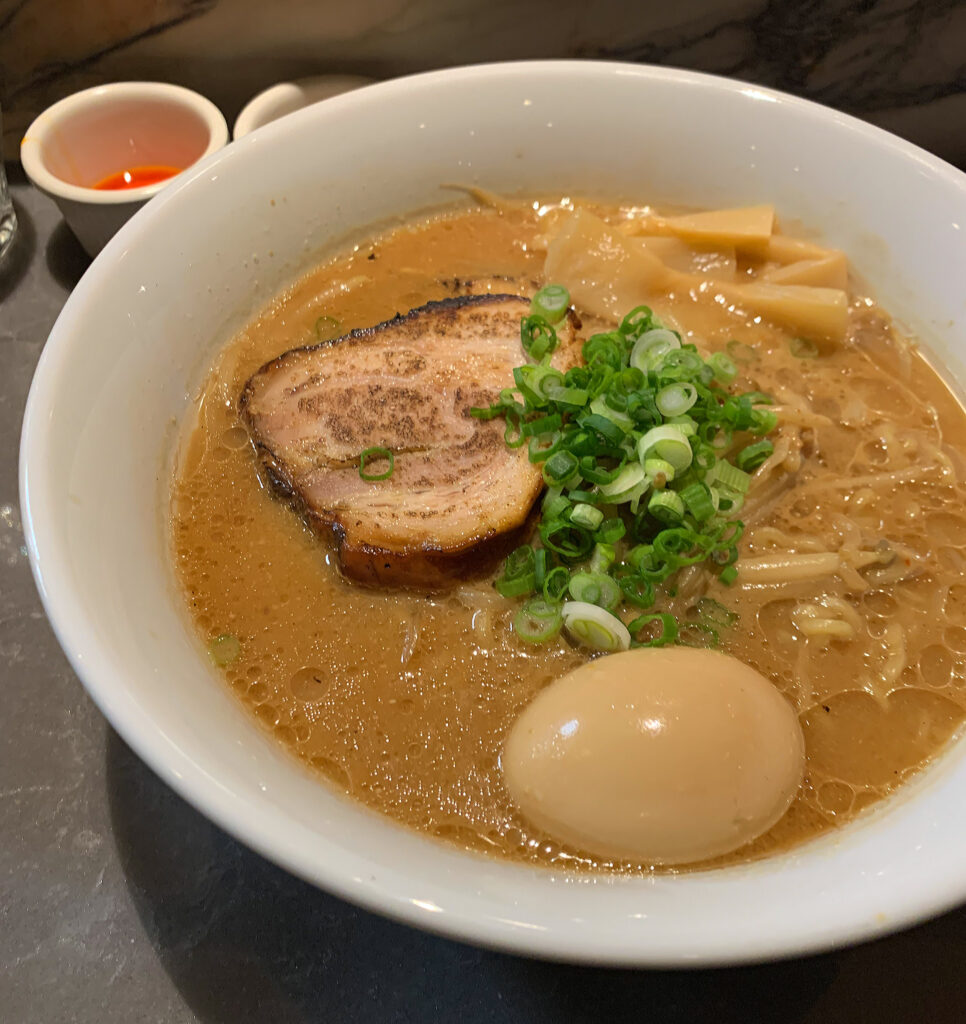

The start of December would also see Michael Nagrant term Akahoshi “Chicago’s Best Ramen” while The Infatuation (though not yet formally rating the establishment placed the concept at the top of its “The Best Ramen in Chicago” list. The latter publication noted at the time that “a line forms outside 30 minutes before” the restaurant opens and praised the fact that “each of their four bowls is distinct, with only a handful of toppings, giving every ingredient room to showcase its flavor.” More particularly, the namesake “Akahoshi Miso” was praised for “tasty wok-fried bean sprouts, pork chashu…springy housemade noodles” and a “rich garlicky broth.”

Later that month, Eater Chicago would again feature Akahoshi as “a top contender bringing fresh energy into the city’s chain-dominated ramen scene.” Therein, Satinover would admit he “doesn’t know” hot he feels “about being dubbed ‘the best.’” To him, “’best’ is a subjective thing” and his “’best’ ramen is not someone else’s best ramen.” Rather, the owner simply thinks he has “a lot to offer the Chicago ramen scene.”

(In 2018, Satinover sounded a less diplomatic note, stating: he “honestly” thinks he “dominate[s]” the Chicago ramen scene. He thought the stuff he puts out “completely trounces any restaurant in Chicago” and declared he “will accept nothing less than being number one.” To that point, the Akahoshi owner asked himself if he wants “to be the best among the average” or actually “stand with giants.” That is what would drive “intense improvement,” and you must keep in mind that this was more than 5 years before the restaurant opened its doors!)

Toward the end of December, Akahoshi would be named one of “Chicago’s 11 best new restaurants of 2023” by a panel of three “dining experts,” with Mike Sula praising Satinover’s “decade methodically learning how to make ramen” and “self described control freak” character without any further comment on the food. (You might remember that Sula collaborated with Satinover—twice—on the former’s “Monday Night Foodball” pop-ups. Praising the restaurant without acknowledging that seems like a clear ethical lapse.)

Finally, most recently, Satinover would reflect on the opening of his restaurant in an “Ask Me Anything” on Reddit’s /r/chicagofood subreddit. There, in early January, the Akahoshi owner shared some details on how the business was doing and the philosophy that was guiding its operation.

He revealed that he was “doing 160-190 bowls of ramen a day” and “literally could not make more ramen if…[he] wanted to.” Satinover liked where his business was at, and producing more would cost an amount of money he doesn’t “want to spend” and require “relinquishing more control of production, which could impact quality.” Pricing the food, he admitted, was “a very delicate game.” During the soft launch, “tickets were $25” and the restaurant got “SO many complaints about the price, and in turn the food ‘not being worth it.’” Settling on a range of $18-$19 for the bowls, they “get far fewer comments, mostly that it is ‘expensive but worth it.’” Ultimately, Satinover believes “you should charge as much as you can get away with,” but certain concessions were made. He offers reservations because he’s “willing to take a hit on revenue to make customers happy” and “some people hate waiting.” However, “candidly,” if the owner wanted the restaurant to be more profitable, “the easiest way would be to remove reservations entirely.”

To that point, Satinover acknowledged the “true value of wait times and scarcity, which is “that scarcity creates a perception of value and quality that leads to long-term revenue opportunity.” The owner noted that “Hogsalt knows this, clearly,” and “it’s why literally every restaurant they open has wait times to get in” (even if he questions “if those wait times are real or not”). Satinover didn’t just want Akahoshi to be “busy now” but to “STAY…busy in 6 months,” which would affirm the concept “must be pretty good.” Ultimately, he reverts to his marketing background and cites the “sense of unattainability” that “drives demand” for products from companies like “Hermes, Nike, [and] Gucci.” The same “is true in restaurants” even if, in the short term, it seems a place like Akahoshi “should charge even more or make more product.” But “good marketers and businessmen know that scarcity breeds demand,” and that is why he runs the shop in his chosen manner.

More practically, Satinover noted that he doesn’t “’make’ much ramen as a restaurant owner now.” He “make[s] noodles, yes, but almost nothing else” and spends most of his time doing “payroll and inventory and finances and cleaning” along with “staffing and HR,” “contracts and supplier management,” and “marketing and menu planning.” In sum, “owning a restaurant is like 10% cooking,” but he was enjoying the other “90%” and even “the headaches,” like “when your dishwasher goes down and you have to call Ecolab at 8 pm on Friday” or “when a server gets sick and can’t come to work, but you have 100 reservations and a line out the door.” Satinover even divulged that “seeing folks eat the food…doesn’t register” due to his fixation on “what ISN’T good with the ramen.” He had also “definitely” become “less involved” on the /r/ramen subreddit, saying “you should see the complaints” over his “general lack of moderation.”

Still, creatively, there was much to look forward to. Satinover noted Akahoshi was “definitely doing and open to doing collabs,” especially “for a good cause.” The owner also revealed a new ramen would be debuting “as a special for the rest of January” and that he has “a long running list of specials,” “maybe 25 dishes deep,” that he’d “like to try.” To that end, Satinover would specify that he thinks “by definition” he is making “American Ramen” at the restaurant given his own nationality and how “tricky” it is to label the dish. Sometimes the ramen “feels very Japanese”—and sometimes it’s inspired by “other genres of food”—but it really centers on making what he loves.

At last, you come to the present day and the chance to taste the fruits of 14 years of obsession (10 of which were shared exhaustively online). Yes, while you are used to extensively tracing chefs’ careers (those movements from kitchen to kitchen and the moments that shape a personal culinary style), this feels different. It even stands distinct from a rare breed like Phillip Frankland Lee, who leveraged Top Chef infamy and self-funded concepts into earning a Michelin star.

Compared to professionals whose stories are brokered by journalists (and, perhaps, a small amount of social media engagement), Satinover’s growth as a home cook and internet personality has been laid painfully bare. His maturation from ramen-craving college student—unafraid to be a “snob” or put Chicago’s purveyors of the dish in their place—into magnanimous business owner has, too, been made apparent. But do people really change from whom they were when they were younger, or do they just grow more adept at concealing their flaws and channeling their virtues into an identity they can hope to sustain?

Looking back, Satinover was clearly the beneficiary of a digital ecosystem he built for himself. No doubt, growing /r/ramen took work and hinged most of all on being a friendly resource—the friendly resource—for all things noodles and broth. Yet “oversharing,” as he calls it, also offered a clear path to adoration (via upvotes) and authority. It offered a path toward the kind of “expertise” that is usually only attained by working in kitchens or climbing up the rungs of traditional media. It allowed him to sidestep that “toxic” restaurant culture from high school and keep the comparably cushy marketing consultant job to boot.

The 1% rule observes that “only 1% of the users of a website [that is, an internet community] actively create new content, while the other 99% of the participants only lurk.” Likewise, the 1–9–90 rule states that, in a collaborative website, “90% of the participants of a community only consume content, 9% of the participants change or update content, and 1% of the participants add content.”

Satinover is a shining member of this 1%—compulsively so. Remember, the genesis of his obsession with ramen was “essentially random” (or, at least, circumstantial given he was “a broke college kid” in a “mega ramen town”). “Posting bowls of ramen on Reddit” was, likewise, something he didn’t really know why he did: attributing it to being “unemployed” and needing “an outlet for creative projects,” thinking it “was cool” there was a receptive community, or maybe being “homesick for Sapporo.” Whatever the reasoning, he trained for four years before taking the plunge, ensuring the “Ramen_Lord” account would start off on the right foot and tap into the website’s natural reward system (i.e., upvotes). That quickly led to esteem, power (essential for someone who admittedly doesn’t “have very thick skin”), and the ability to lead internet discourse surrounding his favorite dish.

While stressing he was only posting “for the love of noodles” (rather than looking to “make some money on this”), Satinover took aim at High Five, Furious Spoon, Slurping Turtle, and chefs like David Chang. He termed Nick Solares “full of pretentious over the top garbage” and told errant users to “please read up on the history of ramen” and “understand that your fetishization of soft boiled eggs is an American affectation more than anything.” Still, Satinover was a benevolent ruler, generating boatloads of content (the same pictures of food that any garden variety “influencer” might post) and giving recipes out for free even as he unilaterally decided how—and about what—the ramen community would converse. Eventually, the “Lord” came to be summoned by users all too happy to play along with his self-chosen title in a bid to get a brief audience with the Reddit “celebrity” and secure their share of the upvotes. He would bashfully respond to the honorifics but still flexed his authority, consolidating the reputation that made him an online institution.

In 2017, Serious Eats and the Chicago Tribune provided Satinover with a crossover of traditional media legitimacy. At the time, he had “thought about” opening a restaurant (“even down to calculating how many bowls he’d save to sell to make a profit”) but was “actively against” doing so. Instead, he would continue to feed journalists and other industry figures for free at intimate home gatherings. Nonetheless, the end of the year saw him host his first pop-up in New York, the first of dozens of these events staged until Akahoshi’s opening. The moderator gleefully violated his subreddit’s rule against “self-promotion” to share news regarding many of the engagements. After all, this was his community, he was their “Lord,” and there could be no perceived hypocrisy from someone who had given users so much for free—never mind that Satinover “always” made profit from the events (“usually around 50% operating profit”). He was making “arguably the best ramen in Chicago” (in his own words) after all, “completely” trouncing “any restaurant” in the city.

Though formerly “not really in this to make money,” 2023 finally proved to be the right time to cash in. The same “journalist” he hosted in his home (at least) three times was ready to trumpet that Akahoshi Ramen would be “coming soon from Chicago’s favorite ramen obsessive.” Satinover had finally, miraculously realized “not all kitchens operated the same [toxic] way.” Of course, he wasn’t looking to compete with any of the restaurants he had disparaged for years but only to “increase the appreciation of ramen” and “increase the discussion.” How gracious! Plus, after hammily playing the part of “Ramen_Lord” for a decade, he also now didn’t “want to put on this air like” he knows “so much.” He wanted diners “to understand that he’s an enthusiast, not an expert” (and not to judge him with the same venom he so readily flung toward those other chefs). Satinover was also suddenly not comfortable “being dubbed ‘the best’” (after happily celebrating himself as such). He’s just “a white guy making ramen” after all!

Upon launching Akahoshi with a cutthroat business model based on scarcity and perpetual hype, Satinover was—at last—warmly received by the members of his subreddit, the journalists he’d hosted (and collaborated with), and an assortment of other industry figures he had fêted and reflected a bit of his digital fame back onto. That is, back in the day when he was never, ever going to open a restaurant of course.

You admit you are interpreting Satinover’s story rather cynically, and, likewise, you hope you have not delved too deeply into armchair psychology. This defensive posture is justified by the fact that Akahoshi is reflective of an emerging, almost hereto unseen, strategy for restaurant development. Satinover ingratiated himself with an online community, commandeered it, consolidated power as an “expert,” talked ill of Chicago restaurants and other chefs, promoted pop-ups against his own subreddit’s rules, and suddenly reinvented himself as a kind of ersatz kumbaya proprietor upon finally reaching a critical mass of support.

Surely, you are skipping over a lot of time and energy spent helping people better understand ramen and cook the dish at home. But what does being a terminally online Reddit moderator have to do with running a restaurant? And why should Satinover, uncritically, be allowed to take over a Chicago ramen scene he happily denigrated with the excuse that he was not (once upon a time) looking to make money from his passion? Shall the city just take him at his word? For, the fans he gained through this unethical behavior are the same ones that will make his scarcity model work, and the media figures who celebrated the shop’s opening would not (you hope) have implicated themselves had they known the real score.

Ultimately, just as some diners will naturally be drawn to Satinover’s story (or, if they have followed him on Reddit, his status), you must put forth a counterargument: “Ramen_Lord” was an adaptive marketing strategy almost from the start, a bad-faith effort to try and guarantee success in an unforgiving industry from someone who never had the mettle to actually pay his dues under a master. One bad experience in high school led Satinover to brand all restaurant culture as “toxic,” to retreat online, to sink into his compulsion, to become seduced by power, and to use the dark arts learned during his decade as a consultant to make an end run around the usual barriers to success.

This all might be worthwhile if Satinover really has subverted the industry’s nastiest tendencies to offer Chicagoans something superlative—if he really has forged a path for kindred, tender souls to successfully transmit their passion to the masses without being chewed up and spit out. Just the same, is the city being taken on one big ego trip by someone who quite simply learned how to play online sycophancy to his advantage? The answer, as always, can only be determined by evaluating those stalwart dimensions of quality, consistency, and value (free from any bowing to hype or conscious revulsion thereof) that guide each of your reviews.

You have visited Akahoshi Ramen a total of seven times, comprising a period from mid-December of 2023 to late January of 2024. As usual, you will condense the sum of your experiences into one cohesive narrative.

With that said, let us begin.

Visiting Akahoshi Ramen brings you to an eerily familiar area: a stretch of California Avenue just north of Milwaukee and south of Fullerton. Daisies “2.0,” the thought of which still makes your stomach churn, lies just around the corner. And you find across the surrounding blocks all sorts of familiar names: places like Andros Taverna, Bungalow by Middle Brow, Easy Does It, Kyōten, Lardon, Longman & Eagle, Lula Cafe, Mi Tocaya Antojería, Paulie Gee’s (the site for some of Satinover’s pop-ups), Pretty Cool Ice Cream, Spilt Milk, Superkhana International (the site for another pop-up), and Taqueria Chingón. Most interestingly, you find the range of other ramen shops that was mentioned at the time of Akahoshi’s announcement: Furious Spoon (Satinover’s nemesis), Monster Ramen, and Ramen Wasabi. Looking further down Milwaukee, you may even include Kizuki or Oiistar; however, it is hard to say that the area is totally saturated in noodles and broth.

Rather, this part of Logan Square—and perhaps extending into Wicker Park—is defined by a panoply of casual fare sprinkled with the occasional big-ticket item (like a $65 “Prawns de Jonghe” or, say, a $490 omakase). You do not mean that with the slightest disrespect. For, while West Loop remains king when it comes to fully-fledged gastronomic concepts, this composite neighborhood can boast one or more examples of Chicago’s best beers, burgers, charcuterie, cheeses, cocktails, fried chicken, ice cream, pastries, pizza, and tacos. This is to say nothing of the legendary farm-to-table fare or—dare you say—ramen to be found there.

These are places you can conceivably walk into or, at the very least, put your name down and wander around for a bit with a real hope of being seated in the foreseeable future. This is an area where you can fixate on a handful of recipes or techniques and execute them at volume, on your own little street, with some hope of success. Ironically, it is those concepts that try to do too much (e.g., Andros Taverna and Daisies) that you have found fall flat.

This is all to say, Satinover has chosen well when it comes to Akahoshi’s location. There were savings of “a solid 300K” involved, as well as a certain strategizing (in terms of the demographic that patronized the pop-ups), but the place fundamentally fits the scarcity model with plenty of surrounding foot traffic and myriad options to whittle down the wait. Just the same, Akahoshi’s particular block of California Avenue is quiet enough: you only note a bank, a salon, a tire shop, a pet store, a post office, a gas station, a smattering of residential buildings, the aforementioned Pretty Cool Ice Cream, and Noca Blu—the very apartment building in which the restaurant sits (alongside a small grocery store).

Though it can be hard to park here come dinnertime, most of the other businesses feel completely dormant. That means Akahoshi’s line can form and grow (and grow) without really impeding passersby (though many exhibit a quizzical look). Indeed, what proves most challenging is the condition of the sidewalks, which you have found on multiple occasions during the Chicago winter to be covered in a wet, slippery slush. Whether the responsibility of salting these surfaces falls on Satinover or his “great landlords” at Noca Blu is unclear; however, the state of the cement is both hazardous and a bit disrespectful toward those willing to wait out in the cold to support a business.

When you arrive at Akahoshi just a few minutes before your 5 PM reservation, the line of would-be patrons numbers somewhere between 20 and 30 people. (On Saturdays, that can balloon up to 50 or 60.) Given the restaurant sometimes opens its doors three to five minutes late, you have learned that it is often best to wait in your car (if possible) until closer to 5:10 PM. In truth, it is probably even better simply to book your seats at 5:30 PM or any time later in the evening to begin with. Otherwise, you will still be subject to all the chaos surrounding the opening rush.

To be fair, the process—when you have chosen to join the scrum—is pretty well managed. There is no avenue for those who have reserved seats to skip to the front of the queue (even considering the one-hour limit parties of two have to dine), a choice that may admittedly help to avoid any undue confrontation. For, especially during the first few weeks of service, the excitement shared by those waiting in line is palpable. Party by party, inch by inch, these poor souls wonder if they will have made the cut to be seated right away. Eventually, from the other side of the glass, you see the communal tables reach their limit. Instead of smiling, those who reach the host stand start to furrow their brows. They think for a moment, put down name and number, then retrace their steps—out into the cold—looking one of several shades of disappointed.

By the time you finally find your way inside, the walk-ins in front of you are being quoted wait times of 25, 45, or maybe even up to 90 minutes (depending on the day). In the latter case, they hem and haw a bit until finally, like all the others, submitting to the wait and getting out of the way. (On Saturdays, all the walk-in seats for the entire evening may be claimed as early as 5:11 PM.)

Finally, it is 5:12 PM and the opening line has all but dissolved. You approach the host—a burly, bearded man no doubt chosen to intimidate restive guests—and see his lips purse, ready to dispense with more bad news. But you say that magic word, “reservation,” and he marks your name off his tablet without giving any grief regarding your unavoidable late arrival. It may be the fifth time you’ve seen the host this month, the second time you’ve checked in at the restaurant in 24 hours, but there’s no form of recognition or “welcome back” (even if OpenTable serves him with that very information). Instead, almost as if shrugging, he leads you to your spots, halfheartedly mentions the QR code, and maybe—but not always—brings a carafe of water by before returning to his post.

Along the way, you have a chance to get the lay of the land. That begins outside, with a high-top counter (reserved for walk-ins) that abuts the windows running along California Avenue. There is also, on the other side of the front door, a small alcove containing Satinover’s fancy noodle-making machine. Stepping through the entrance, you find to your right the area occupied by Akahoshi’s back of house. This includes a small bar, some bins containing flour, a commercial mixer, the expansive open kitchen, and a rear dishwashing area that is only barely visible. To the left (in front of the high-top counter), you find a small open space where up to 10 patrons may try to huddle together while awaiting their tables. This is probably not encouraged by the establishment, for it makes forging a path to the exit somewhat tricky at times.

Parallel to the host stand—and situated right at the threshold that separates the open kitchen from the dining room—you find the ramen counter: seven low seats set before upper and lower tabletops with views of all the action. Gaps located on either side of this surface provide access to the staff when it comes time to retrieve customers’ food or return dirty dishes to be cleaned. Behind the ramen counter, running along the very center of the dining room, you find two communal tables separated by a support beam. The first of these, closest to the entrances, offers room for 14 guests in various configurations. The second of these, snugly shielded by that structural element, only seats four to six and actually feels more or less like a private table depending on your party size. Finally, along the wall opposite the kitchen, you find a series of six booths suitable for two (very comfortably) or four (comfortably enough) guests. A service station and a pair of bathrooms can be found at the very rear of the room.

Looking more closely at its details, Akahoshi’s interior design is defined by light tones of wood (seen across the various tabletops, as well as some of the booths’ surrounding trim) blended with off-white (the wallpaper, the framing of the kitchen), white marble (the host stand, ramen counter), faded red (sections of the ceiling, the kitchen flooring), gray (the dining room flooring, wallpaper, tiled walls/beams), stainless steel (the kitchen’s appliances), and black (the chairs). Many of these elements are complemented by real (or supposed) expressions of texture: the grain of the flooring, some errant brushstrokes (in white or black paint) applied to the wallpaper, and the subtle ridging of certain tiling.

The biggest bursts of personality come from a handful of flourishes like the embroidered cushions on the booths (done in a grid-like pattern), burnished mirrors and sconces (set above each booth), and an array of plant life (on the walls, some of the shelving, and certain surfaces). The framing of the kitchen, which you mentioned above, is also worth dwelling on. Extending down from the ceiling, it comprises a thick wooden base (the underside of which holds track lighting that illuminates the ramen bar) with a shorter, thinner section of wood set above it. Between the two layers, you find a kind of paneling dividing small windows draped with sheer curtains. The overall effect of this woodworking calls Japanese architecture to mind—though only subtly—and it is worth considering that only those patrons seated some distance from the kitchen will really be able to notice this element. You might also mention the design of the bathrooms, which feature two patterned wallpapers (one grid-like and set with concentric circles, the other reminiscent of sketched spools of noodles) separated by recessed LED lighting that glows red.

Overall, Akahoshi’s interior design is clean, modern, and bathed in warm, soft lighting. Though the details you noted provide some visual intrigue when taken in isolation, their effect—in practice—is rather subdued. The shop has seen little natural lighting (during service hours) since opening, and the constant crowds mean that it is hard to really meditate in the space or hone in on any of its textures. Rather, subconsciously, you get the sense that you are sitting among an overworked hodgepodge of ideas, a “throw everything at the wall and see what sticks” approach that somehow, perplexingly, expresses nothing. It’s as if Satinover and Siren Betty looked through a bunch of catalogues and wove a bunch of products together—with some amount of cohesion, you must admit—without any larger sense of personal narrative or profound inspiration.

To be fair, the owner does express a bit of his personality (presumably) through the new wave-inflected soundtrack that, while sometimes a little loud (depending on the energy level of the assembled crowd), imbues the space with a more upbeat feeling. Nonetheless, it is hard to describe Akahoshi’s design as anything more than competent: the product of playing it safe, paying a lot of attention to what technically makes sense, but never engaging emotion or conjuring the kind of transportive effect that characterizes a place like High Five. Really, at an aesthetic level, Akahoshi does not distinguish itself from neighbors like Monster Ramen and Ramen Wasabi (the latter of which can at least tout an extensive Japanese whisky collection on display) while falling quite a bit short of the mood at the much-maligned Furious Spoon.

You can appreciate that Satinover did not want his shop “to be a stereotype,” that he wanted to “pay respect to certain Japanese aesthetics” while retaining “a level of ‘American-ness.’” However, this fear of “having a target on his back” and décor being “an easy place to target” has proven paralyzing. The owner didn’t want Akahoshi to “look junky, parsed together from scraps and ideas over the course of its life,” but does that not signify an evolving, reflexive kind of design that allows the restaurant to grow and reflect the experiences of its proprietor? Satinover affirmed that “he knows who he is” and that the shop would be a “deep representation” of him, “specifically.” Yet how can that be expressed purely through materials, subdued colors, and the strange, quasi-Japanese framing of the kitchen? Where is the passion for ramen, for other ramen shops, for the many people the owner has collaborated with, for Sapporo, or even for Chicago? Hell, you would even take design elements inspired by Satinover’s Reddit career at this point. For, as it stands, Akahoshi feels plain, functional, and largely soulless. The restaurant reflects the cold, calculated taste of a businessman more than it expresses obsession—or love—for its chosen product. And the owner certainly cannot claim he is anything but satisfied with the space’s “impeccable design.”

Returning to that word—functional—it may be instructive to dwell a bit on the various seating options. You can really only speak to two of them directly (i.e., the ramen counter and the booths), but it stands to reason that the high-top counter (the one abutting the windows looking out on the street) is serviceable for walk-in parties and, especially, for single diners. The communal tables, you have already mentioned, are well-suited to larger groups. These spots can be reserved online, but they’ll force smaller parties into closer confines with other guests while not providing any real advantage (given the poor sightlines offered toward anything of note). Still, at this early stage, who can be unhappy about having any seat aside?

The booths, by your measure, offer the best accommodations. Though described by the restaurant as “cozy,” they feel downright luxurious for a party of two: offering space (for plenty of bowls), privacy (for polite conversation), and an out-of-the-way perch from which to watch the stream of customers and overall operation of the shop. It is from this spot—especially the rearmost booth (closest to the bathroom)—that you can really ruminate on how plain the place’s interior design is. Just the same, there’s a fundamental comfort to these tables that compares favorably to any seats at any ramen place in town—provided you know how to entertain yourself while waiting for the food.

The ramen counter, touted as “facing the kitchen,” would ostensibly offer the most coveted chairs: a kind of chef’s table from which you can watch one of the country’s ramen luminaries ply his trade. But really, you’re just squeezed next to other guests and forced to reckon with how underwhelming the workings of the kitchen are. Maybe that’s not a bad thing—for there are plenty of waiting customers to feed. Yet all you really notice is one cook aggressively flaming bean sprouts in a wok, Satinover gingerly moving noodles from bin to boiling to bowl, and a third cook helping to construct the finished product in between torching slices of pork. Sure, in terms of synchronization and that tranquil (non-“toxic”) working environment the owner so prizes, this coordination is impressive to observe. However, you are not sure the ramen counter experience satisfies any of the action, romance, or even a baseline of interaction that a devoted fan might dream of. The cooks are utterly anonymous—focused on the job no doubt—and do not even bring you your bowls personally despite being mere feet away.

Instead, seated at the counter, you really get a sense of the fanboys and fangirls that Satinover has cultivated: 20- and 30-something nerds, predominantly white and Asian, often bearded or bespectacled, and unabashedly glued to their phones until forced to stammer out an order and then, when the meal is done, ready to erupt in hyperbolic praise. Robbed of an audience with their “Lord,” this loyal following is sure to tell the hapless servers something like “that egg is a work of art.” Others may focus more on carefully intoning the Japanese words sprinkled throughout the menu, lending their appraisal and air of faux sophistication.

You are being a bit mean you admit, and there is certainly some diversity to note: parents with baby and stroller, an older woman and her teenage son, a smattering of younger black couples, and the odd groupings of 40-something white folks. Nonetheless, amid a sea of tie-dye, hoodies, backpacks, and beanies, you find a restaurant in which patrons are largely siloed off—here to seek sustenance in their own little worlds without any pervading, unifying sense of hospitality or community. (You can, at least, attest to one interaction with a neighboring table where you were asked how you managed to get a reservation.) The overall feeling reminds you of dining in a college town; that is, this is a business where eating is a practical, somewhat self-isolating consideration rather than a pilgrimage site defined by a shared, reverent appreciation of craft. Is that a bad thing? A fundamental problem with the Chicago audience? A case of misplaced expectations?

This sensation extends to the front-of-house staff and a series of interactions that begin with the burly host. To his credit, dishing out disappointment to those who have just waited out in the cold for a bowl of hot broth is likely no easy task. Reddit fame naturally attracts manchildren and womanchildren, and the prospect of waiting for hours—or maybe not getting in that night at all—is perturbing for those used to instant gratification (to say nothing of that oppressive fear of missing out). Plus, at least once, the host has bid you goodbye as you’ve walked out the door—signifying that he is trying to be hospitable even if warmth does not quite come naturally.