Kasama first opened its doors on July 29th, 2020, serving casual Filipino-American fare and baked goods for takeout and delivery. The restaurant debuted just one day after Ever, then the great white hope of Chicago dining.

While the city’s “critics” and influencers rushed to gush about Curtis Duffy’s comeback, Kasama quietly won the hearts of its neighbors. Tim Flores prepared housemade sausage, ribs, braised brisket, pork belly, chicken adobo, and fried spring rolls while Genie Kwon displayed her mastery of lamination via inventive croissants and danishes. Some early customers grumbled about the pricing, but those who came away impressed insisted that “you get what you pay for.”

Ever, meanwhile, spurred few complaints from a revolving door of “one and done” diners cowed by the fancy dining room, overengineered food, and parting tour of the kitchen. Delivering the semblance of luxury, in that innocent period between lockdowns, mattered more than achieving its reality. For the narrative of a fine dining establishment birthed in the throes of a pandemic was too good to resist. The restaurant’s superficial aesthetic appeal, photographed and perpetuated for those still cowering at home to see, delivered the social status early patrons sought. Dazzled by totemic luxury ingredients and unequipped to critique the cuisine’s rootless abstraction, the media (and social media) elite christened Ever one of Chicago’s best.

Nobody could confuse Kasama’s fortress-like abode with a Lawton Stanley design. The restaurant would not even open for indoor dining until more than a year later! But Flores and Kwon continued to build momentum by crafting crowd-pleasers like Thanksgiving pies, cookie decorating kits, NYE caviar packages, and Super Bowl pizza/wing combos. Their Serrano ham and Raclette cheese danish was titled Chicago’s “best new bite,” spawning salmon confit and foie gras versions alongside a double-decker danish sandwich. The apple/cheese and chocolate croissants were joined by a decadent Délice de Bourgogne and black truffle rendition.

Kasama debuted their reverent take on an Italian beef combo during a collaboration with Big Kids, and the item would go on to become a menu mainstay. It would soon be joined by a popular “Boston crème” brioche and a range of breakfast sandwiches (plus hash brown) that put Ronald to shame.

Flores and Kwon built their business with the utmost care during its first year, and, despite the lingering effects of the pandemic, succeeded wildly at realizing their concept. Every time the chefs flexed their creative muscles, they seemed to strike gold. Kasama’s estimable opening menu would grow to encompass more than a dozen other definitive items. Lines of patrons routinely stretched out from the building as the restaurant transcended its neighborhood to become a beloved Chicago institution. It was worthy of a drive from the suburbs or even a flight from further afield.

That national and international audience was sure to grow as No Place Like Kasama, a short documentary following the restaurant’s opening, had yet to even premiere. With their personal story presented in a digital video format, the chefs could look forward to a perpetual stream of visitors drawn from its viewership.

Chicago, certainly, has benefited from this kind of storytelling before. Yet, while 2015’s For Grace engrossed its audience with the culmination of Duffy’s life as viewed through his fine dining concept, No Place Like Kasama would tell a story of transition (from “Michelin-starred fine dining” to “a neighborhood spot”) and survival (in the wake of the pandemic). The former documentary could lean somewhat on the wizardry of molecular gastronomy to impress the viewer while the latter would be anchored more firmly in the personalities of its subjects and their fulfillment of a personal, culturally rooted dream.

You, personally, had no need for any such narrative. Flores and Kwon had been Noah Sandoval’s chef de cuisine and pastry chef respectively at Oriole “1.0” during its first two years of operation. They were cornerstones of a kitchen that won two Michelin stars just eight months after the restaurant opened in 2016, and, even then, the organization had already titled the group (including Cara Sandoval and Aaron McManus) a “dream team.” Now, looking back on that time after the wild success of Oriole “2.0” and Kasama, it is safe to say that they formed one of the most talented partnerships that Chicago dining has ever seen.

Of course, it is hard to appreciate a golden age while you are living through it. Flores and Kwon’s departure from Oriole was consequential enough to be reported on at the time, but, from your perspective, the tasting menu’s stunning croissants and take-home treats just suddenly ceased. Sandoval would charge forward with the help of Mariya Russell (later of Kikko) and pastry sous-chef Courtney Kenyon (who, stepping into Kwon’s shoes, would soon go on to craft one of the restaurant’s totemic desserts: the Délice de Bourgogne soufflé). Yet, even from the blissfully unaware vantage point of the dining room, it was clear that Oriole had lost some aspect of its spirit.

When Flores and Kwon left in March of 2018, their next steps were unclear: “we have some ideas that are in conceptual development right now,” the latter said, “but we’re open to other projects if they seem right for us.” The pair, it should be noted, got married that year. However, they shared little else about their long-term plans.

In March of 2019, as you visited and critiqued the newly opened Mako, you swore you spotted Flores working in the kitchen. While B.K. Park (or, more likely, his apprentice or apprentice’s apprentice) cobbled gummy bites of nigiri together at center stage, the ex-Oriole man stayed in the shadows. He would punctuate the omakase’s meager flights of limp sushi with wondrous plates of chawanmushi, poached sea bass, and roast duck that redeemed the meal.

You noted in your review of Mako that the cooked plates make guests “wonder if they’ve been transported to another restaurant. Such is the difference in execution between the sea bass, the duck, and everything else.” That sea bass “could have very well been the best dish…on the [restaurant’s] opening menu,” but you asked why it was “coming from an unknown cook in a hidden kitchen” while Park took all the plaudits. In your final analysis, you declared Mako’s omakase a “sushi ‘side show’” that is “put on while the real work occurs in the hidden kitchen where the man behind the curtain creates food people do want to eat.”

Though few knew it at the time, Flores was the absolute best thing Mako had going for it. Yet, despite his renown, the chef humbly pleased the restaurant’s guests without being given any sort of credit. He was never mentioned on Mako’s menu, its website, or in any media reports (though some would later note his time there when covering Kasama). Chicago’s “critics” were happy to let Park play pretend and take his bow despite relying solely on Flores to salvage a subpar experience. They heaped honors onto the wannabee itamae while the real talent at hand, one they would cheerlead to a deafening degree just a couple years later, totally eluded their perception.

Flores’s time at Mako would come full circle in August of 2019 during a “one-night only collaborative dinner” for the Chicago Tribune Food Bowl. The event highlighted “Park’s pristine omakase creations, Flores’ contemporary Filipino dishes and Kwan’s [sic] outstanding desserts.” You were in attendance that evening, and it was heartening to see the chef finally receive some recognition at a restaurant he had helped shape. Park’s assembly line sushi was as lamentable as ever, but Flores and Kwon showcased some ideas that would later appear on Kasama’s menus. This included early renditions of the danishes, a version of “pancit en su tinta” (squid-ink noodles with ham) later seen on the tasting menu, a halo-halo, and a take-home Basque cake.

Though the Food Bowl event suggested that Flores and Kwon were close to fulfilling their creative vision, all was quiet for nearly half a year. In February of 2020, the husband and wife expressed interest in The Winchester’s former space at a community association meeting. They lived in the neighborhood and wanted “to open a neighborhood spot” in a building they had “always admired.” The concept was labelled a “Filipino restaurant and pastry counter” with the savory dishes drawn from family recipes and the sweets rooted in the “French American” genre.

For Flores, it would be the culmination of a family story that began in 1975, when his parents emigrated from the Philippines to Chicago. Before the two met, his father lived in Humboldt Park and his mother in Ukrainian Village. So a restaurant in East Ukrainian Village serving food the chef “grew up eating” could not be better placed.

Momentum continued to build that month as Flores and Kwon revealed more details regarding their project. The restaurant would be called Kasama, a word meaning “together” in Tagalog. It would be a “loose and informal” place “where locals can afford to eat meals a few times a week” and customers could “embrace wine with Filipino food.” There were no “plans for a tasting menu,” but Flores would have an outdoor space with a grill “for street meat skewers” or “a traditional Filipino pig roast.” Kwon would focus on her laminated pastries while collaborating on savory dishes via items like paratha, “a thin, flaky flatbread served in South India that shares similarities with laminated pastries.” Flores was driven by the opportunity to make “people…see Filipino food in a different light,” and Kasama was then set for “a late spring opening.”

That timetable, of course, would prove impossible. Dreams were deferred due to pandemic lockdowns, and the best laid plans had to be thoroughly adapted for the new world that would emerge from a period of fear and isolation. In late July of 2020, about one month after Chicago reinstituted indoor dining, the time finally seemed right to open.

While Ever, back then, prompted national media coverage as a towering symbol of resurgent luxury and consumer optimism, Kasama seemed grateful simply to open its doors. While Duffy and Muser doggedly sought to affirm their three Michelin star credentials, Flores and Kwon held firmly to a vision of an accessible, hospitable neighborhood haunt.

The ex-Grace guys, secure in the scope, scale, and finery of a space that screamed “fine dining,” were all confidence. The ex-Oriole duo, meanwhile, admitted feeling a mixture of “guilt, excitement, [and] fear” as it felt “tone deaf” to market themselves in the wake of the pandemic’s countless restaurant closures.

Ever welcomed a who’s who of conspicuous consumptive “foodies” and media promoters into its cavernous quarters, delivering on the expectations of a crowd that cared more for the appearance of luxury than its taste after months spent cloistered away. Kasama, despite a lack of relative fanfare and a total reliance on pick-up orders, sold out of food its opening day.

Of course, both restaurants would see some of their early momentum sapped by the second suspension of indoor dining from October 2020 to January 2021. Duffy and Muser would pivot towards their Rêve Burger concept. However, Kasama’s counter service, takeout, and delivery model weathered what for others was a crippling blow. (Flores and Kwon had only offered patio seating up until the suspension and transitioned the space into a heated tent during the fall).

Kasama, thus, built upon its early esteem and cemented its reputation by serving legions of Chicagoans who had heard the buzz and now found themselves, once more, stuck at home. Flores and Kwon made their cooking a part of the city’s holiday celebrations, catered virtual wine dinners/cocktail hours, raised money for charity, and thoughtfully collaborated with other local rising stars.

By deftly navigating the pandemic’s lingering uncertainty, Kasama hit the ground running in 2021 and would go on to accumulate honors from Michelin, StarChefs, The New York Times, Eater, and Esquire. 2022, so far, has added a Chicago Tribune “Critics’ Choice Award” and a James Beard Foundation finalist nomination for “Best New Restaurant” onto the pile.

Ever ultimately earned two Michelin Stars in April of 2021 despite seeing its inspired opening hobbled by the second indoor dining suspension. Duffy and Muser certainly would have preferred inclusion in Bibendum’s subsequent guide, along with a rating based on several months of uninterrupted operation. That way, their restaurant could have retained its insider clout of being “three stars in waiting” rather than being placed in a clear peer group with Moody Tongue, Smyth, and Oriole. Judged against that kind of company, Duffy’s cuisine can only be called austere. Visiting Ever has become a post-pandemic rite of passage for Chicago diners seeking an aesthetic experience (“the meal is first and foremost a visual thrill”), but the restaurant falls well short of achieving any memorable gastronomic expression.

Kasama, in that same guide, was blessed with Michelin’s Bib Gourmand award, a designation for “good quality, good value restaurants” where “customers could spend around $40 for two courses, plus a glass of wine or dessert.” The tire company termed the menu, “albeit brief,” “wow-inducing” with “spectacular sweets.” (Not a bad evaluation for a place still only doing takeout!) All the goodwill Flores and Kwon had earned by humbly serving their community was now endorsed by gastronomy’s “governing body,” who acknowledged the chefs’ “dream…has finally taken shape.”

Kasama, in less than a year, had reached a summit. Not the summit, not the pinnacle of its potential, but a comfortable crest as a beloved neighborhood restaurant and bakery whose appeal had resonated across the city and country. Those braving the lengthening lines were still treated to an intimate experience in which the chefs’ warmth and passion shone out from the kitchen. They greeted guests, packed boxes full of pastries, and saw patrons off with the most sincere gratitude. Flores and Kwon, you can recall, were always quick to offer a cup of coffee to those (yourself included) waiting for pick-up orders. Such was the generous, outright intoxicating spirit with which they approached their proprietorship. That personal touch, combined with superlative fare, made a believer out of anyone who came through that door.

But, in August of 2021, Kasama was ready to write a new chapter. The restaurant, more than a year after opening, began offering indoor service for breakfast and lunch. Dinner, offering Flores’s modern Filipino dishes à la carte, was set to follow. However, staffing issues drawn from a battered labor market forced the husband and wife to retool their concept yet again.

While breakfast and lunch would continue to showcase the fare that had endeared itself to Chicagoans, dinner would comprise a “10- to 12-course tasting menu” that would be “easier to portion” and limit interactions between customers and servers. As exciting as an extended expression of Flores’s cuisine sounded on paper, he and Kwon acknowledged it would be a “departure” from their “accessible” vision for the restaurant. The decision would channel the couple’s fine dining expertise more concertedly towards advancing Filipino food at a cost, perhaps, to the restaurant’s everyday neighborhood appeal.

In November of 2021, dinner reservations would go live and Kasama’s tasting menu would debut offering 13 courses at a $185 price point with seating for 18 to 24 guests. Despite early misgivings regarding the shift towards “fancy plating and coursed-out” fare, Flores and Kwon sounded optimistic. They had created a “distinctively separate concept” from the popular daytime offerings whose higher price would help them pay their staff more. The format, for what it lacked in accessibility, would now offer Flores a bigger stage “to cook the foods his mother, Lolita, would make for his family.”

Stylistically, however, the chefs sought to avoid the snare of “authenticity.” Kwon had labelled the cuisine “Tim- and Filipino-forward” while the reservation page itself calls it “an elevated Filipino inspired tasting menu.” Flores shared that he “feels a responsibility to inspire other Pinoy chefs,” so, beyond satisfying “diners familiar with Filipino cooking,” he “also wants to challenge their perceptions.”

That might mean embracing Spanish scallop conservas for one of his dishes and reveling in the decolonial irony: “I’m going to take what I want if you’re going [to] take what you want.” With regard to lumpia, Flores said he’s “prepared” for critics who will say it’s “a humble street food and has no business on a tasting menu.” “We’re always going to fight that battle,” the chef affirmed. “People are so upset that it is expensive, but nobody questions a meat ravioli. What’s the difference? They’re both wrapped-up things.”

Kwon, who planned on serving a dessert of “croissants with black truffle,” “doesn’t need to be reminded” that they “aren’t Filipino.” But the French pastry would be buttressed by the “iconic Filipino dessert” halo-halo.

Overall, Kasama’s tasting menu looked to offer its chefs ample room to explore their personal creative proclivities under a permeable Filipino banner. Yet there was no sign of anything too offbeat or indulgent. The task remained “to get people to look at Filipino food in a different way,” and the chefs girded their mission against “self-important Internet trolls disguised as critics telling…[them] they should have just stuck to pastries and longanisa.”

You find that defensive posture and sense of something to prove, even after a year of wild success, endearing. Flores and Kwon took nothing for granted. They even, it seems, were prepared to weather any eventual haters.

From your perspective, American food culture is not naturally opposed to the idea of “Filipino fine dining.” Rather, it simply lacks mainstream reference points that would help entice the populace to pay for a premium experience. The cuisine, perhaps, suffers from a larger disengagement with Southeast Asia across the board. The entire region, despite a history of American intervention, forms a blind spot in the cultural consciousness. It has certainly not been associated with “luxury” before, and a high price point applied to something unfamiliar might be enough to spur a kneejerk kind of disgust. However, such a reaction has more to do with a latent fear of the unknown rather than any concerted criticism of Filipino cookery.

Considering the demise of French and Italian fine dining concepts in Chicago over the past decade, gastronomy’s historic association with European forms hardly exists in practice. The city’s most renowned restaurants are chef-driven and rooted in distinct technical styles that are applied towards diverse ingredients to create dishes that reference a world of cuisines. “Contemporary American,” as the genre is often called, has almost become a meaningless term. Nonetheless, you will concede that it may sound more comforting to a first-time fine diner than a modern take on what might be, to them, a totally unknown tradition.

Kasama, undoubtedly, is chef-driven too. It is imbued with the reputation Flores and Kwon earned at Oriole. The tasting menu is built upon a year of ribs, wings, pizzas, beef combos, breakfast sandwiches, pies, cookies, croissants, and danishes that conquered mainstream tastes. You can see why the restaurant’s original intention was to expand its comforting à la carte fare for indoor dinner service. It would offer a natural extension of a winning style free of any undue expectations.

The fateful, compassionately grounded decision to offer a tasting menu would transform Kasama into a symbol whether the chefs liked it or not. The restaurant had already become a “pilgrimage” site for “the Fil-Am community” and was framed relative to a “select few” other Filipino set menu spots like “Bad Saint in D.C. and Archipelago in Seattle.” It could be, for the Midwest, a cultural beacon. It would provide easy fodder for coastal tastemakers desperate to deliver Middle America from its backwards tastes. The narrative all but wrote itself. Really, it could have come tied in a bow.

But you cannot blame the chefs for empowering media machinations that cheerlead identity in a marketplace always searching to further segment consumers. Some part of their audience, in accordance with a certain set of characteristics, would naturally value the chance to try a novel interpretation of an underrepresented cuisine. A high rating, for this population, would only sanctify that implicit urge to sample what’s new and exciting.

The opposite contingent, averse to deviating from eating what is most familiar and comfortable, must be cajoled by hyperbole and a critical mass of media coverage to take the leap. Kasama, surely, has no trouble filling its seats night after night, but, once the opening wave of gushing coverage fades and reservations can be more easily secured, will that more obstinate segment of consumers still be interested? Maybe such a population, if they show no interest in expanding their tastes, does not really matter. Yet “getting people to look at Filipino food in a different way,” by your measure, demands convincing the gastronomic dregs of society rather than feeding the furor of “foodies” and an influencer class that always stand ready to prostrate themselves before the next big thing.

Kasama, thus, must be appraised independently of any symbolic cultural value and judged as a fine dining experience relative to all others. For the purest expression of artistry only arrives when a work transcends, rather than merely satisfies, the expectations attributed to a distinct identity. At that point, when only the indelible aspects of identity remain, does individual craftsmanship cross ethnic boundaries and truly stir the soul.

You have sampled Kasama’s tasting menu on five occasions and, as is standard, will condense the sum of your experiences into one cohesive narrative.

With all that said, let us begin.

In the glow of the evening light, the black brick building at Augusta and Winchester looks positively foreboding. The curtained windows and subtle relief of its frieze feel as if they are only missing turrets to complete the fortification. The front door, set flush with the outermost wall, waits to be breached. No stoop, not one step, juts out onto the slender stretch of sidewalk that runs along the façade. 1001 cuts a different figure from the brownstones and condo buildings it has for neighbors, and it might just go on to make the block famous. (Well, more so than the Shit Fountain that lies to the east).

Kasama is beautifully isolated despite being sandwiched between two sprawls of restaurants on Chicago and Division. When the patio is buzzing and customers line the street waiting to raid the pastry case, the restaurant fulfills that image of the inviting “neighborhood spot.” Under cover of darkness, however, the building encloses itself. Save for the signage subtly affixed to the brick and some menus posted on the inside of the door, you could be forgiven for wondering if this is really the home of the city’s hottest new tasting menu.

That, you think, provides the perfect tonic for all the hype. As influencers of all stripes fall over themselves to hitch their wagons to dining’s latest shooting star, the visceral experience of visiting Kasama remains subdued. You park and trace a path down the quiet street anxiously awaiting your entry into another world. Yes, perhaps you have contended with the daytime crowds here before, but this occasion is singular, a bit mysterious, and leavened by the stratospheric expectations formed from a shrieking press.

You enter off the street, climb a couple steps in the vestibule, and open one more door that leads into the restaurant proper. Warm lighting drawn from flickering candles and overhead globes greets you. Set against the white brick, tiles, and curtains, the pale wooden surfaces, and the ample greenery, the gentle radiance feels serene.

Your greeting, which is promptly offered by the general manager, is every bit as ebullient. She relieves the party of its belongings and shepherds you towards one of two dining areas. To the right, a set of five tables line a banquette that faces the kitchen. To the left, a set of five tables line a banquette that faces the bar. While the former area offers guests a view of the action, the latter feels more tranquil and benefits from a greater degree of decoration. The latter space can also more easily accommodate larger parties (up to six); however, having always seated yourself facing the wall, you find the dining experience on both sides to be equivalent.

Kasama’s furniture was chosen with more casual operation in mind, and it still suits the tasting menu format well with the benefit of low lighting. The banquettes, of course, offer a more comfortable accommodation for half the party. The armless wooden chairs placed opposite them are serviceable but could be improved upon. They are just robust enough to avoid distracting from the meal, but the wooden armchairs and armless metal chairs that once featured in the space look like they would have better helped guests recline and savor their time at the table. Nonetheless, that’s a small gripe, and the chosen chairs do satisfy the aesthetic and practical demands of a restaurant serving crowds at breakfast and lunch.

The interior, more broadly, succeeds in establishing a sense of intimacy. The space feels lovingly curated while the number and spacing of tables establish an exclusivity that channels attention solely towards the cuisine. For the price, you get an artisanal experience crafted by a kitchen that stands within eyesight. There are few of the superfluous bells and whistles that prefabricated fine dining concepts lean on to conjure a sense of “luxury.” Rather, Kasama, in the evening, feels like a genuine extension of its daytime identity. It’s the “neighborhood spot” dressed up for a special occasion without any added pretense or plumage.

Once the excitement surrounding your inaugural visit faded, subsequent dinners have left you feeling thoroughly at ease in the space. Of course, it sounds silly to imply that an expensive tasting menu could provoke a sense of discomfort. However, Chicago is home to several “renowned” establishments that persist in offering stilted, solemn hospitality even after years of patronage. Mere mechanical precision can never replace the cultivation of team spirit, for it is the latter element that empowers the authentic expression of individual personalities and undergirds the emotional connection between server and served. Kasama’s staff is both technically sharp and a pleasure to interact with. They make you feel at home.

Additionally, you conducted the same sort of “towel test” described in your Oriole “2.0” article. The cloth, in this case, was placed in a devious spot opposite the bathroom door and just out of reach. Though only the faintest bit of fabric was visible hanging over the edge of an upper cabinet, the towel was removed by the time you returned two weeks later.

Upon taking your seat, the server arrives and offers a warm greeting. They note your preference of water and offer further beverages. While a non-alcoholic option ($65) exists, most customers will be led towards the standard pairing ($115). Being “created by Oriole sommelier Aaron McManus,” it is no surprise that the selection delivers quality and value.

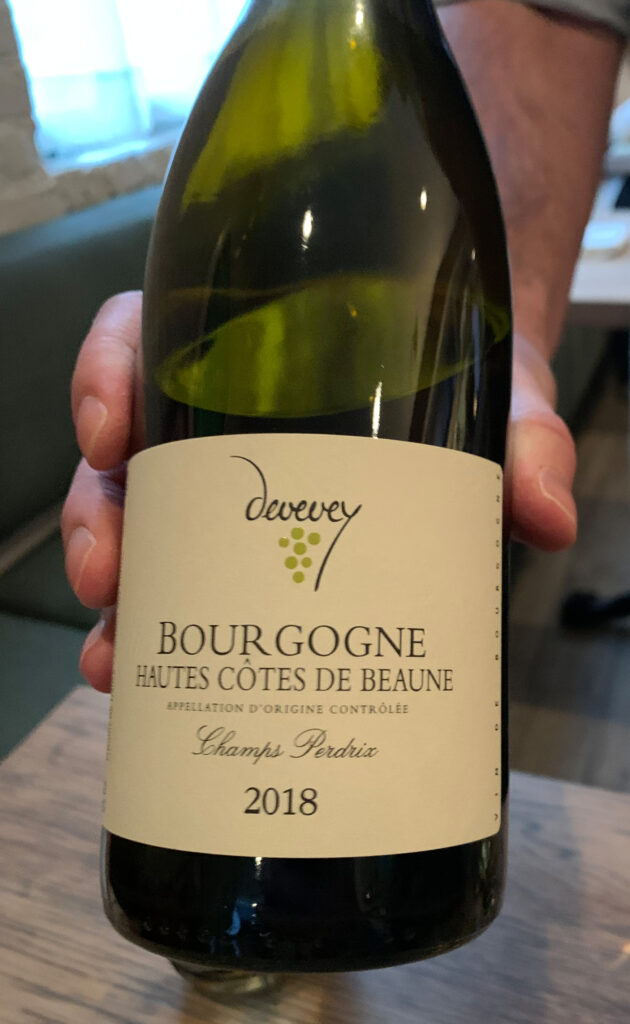

Chosen wines have included Champagne from Charles Heidsieck and Collet, Grüner Veltliner from Weingut Loimer, white Burgundy from Jean-Yves Devevey, and Mencía from Raúl Pérez. Vouvray, Barbaresco, Montagne-Saint-Émilion (a Bordeaux-style blend prominently featuring Merlot), and Sauternes from lesser-known producers have also featured on the pairing alongside Junmai Ginjo Genshu sake and a kalabasa (squash) cocktail made with Suntory Toki whisky. Overall, it’s a diverse, engaging selection of drinks that is easy to enjoy and reflects some of the top QPRs across its categories. $115 for nine different (generous) pours is, by your measure, a friendly price. It succeeds in fulfilling Flores’s mission of wanting “customers to embrace wine with Filipino food.”

Kasama’s by-the-glass selection is generally drawn from the same bottles seen on the pairing; however, the addition of a Marlborough Pinot Noir ($18) is a savvy move catering to imbibers who find Mencía, Merlot, or Nebbiolo to be too robust. The restaurant offers quintets of beer ($7 each), cocktails ($15 each), and non-alcoholic creations ($13) as well. You have tried the “boracay boulevard” (rhum, amaro, and sarsi syrup) and enjoyed how its spirit-forward attack is moderated by pleasing tones of sarsaparilla. The “ube gin fizz” (Botanist Gin, ube, egg white, and cream), by comparison, is a frothy dreamboat of a beverage that goes down like water.

Kasama’s full by-the-bottle list, you must say, has been a wonderful surprise. It not only reflects a desire to encourage wine appreciation through low markups, but features a laundry list of top values from some of the finest producers in their price categories. For Champagne, that comprises a non-vintage premier cru offering from Roger Coulon ($150), whose wine also features prominently on Kyōten’s list. White wines include a 2019 Albariño from Do Ferreiro ($52), a 2019 Kabinett from Dönnhoff ($60), a 2019 Sancerre from Lucien Crochet ($70), a 2017 Vouvray from François Pinon ($75), Massican’s 2020 “Annia” blend ($78), and a 2015 premier cru Saint Aubin by Philippe Colin ($140). Reds include a 2020 COS Frappato ($60), a 2019 Anthill Farms Pinot Noir ($78), a 2018 premier cru Savigny-lès-Beaune from Pierre Guillemot ($115), Ar.Pe.Pe.’s 2015 Valtellina Superiore ($120), Snowden Vineyards’s “The Ranch” Cabernet ($135), Littorai’s 2018 “The Haven” ($180), and Taupenot-Merme’s 2017 Gevrey-Chambertin ($185).

Wine service itself is confidently conducted with servers sure to ask if you prefer a white wine glass for your Champagne and quick to offer decanting should it be needed.

Though you have never inquired about corkage, allowing customers to bring their own wine in could be the cherry on top of Kasama’s beverage program. Nonetheless, the generous pricing of the restaurant’s pairing and its bottle list could necessitate a higher fee. Corkage should not encourage undue cost-cutting by customers, so something in the $30-$50 range could ensure that the restaurant is made whole. At the same time, such an amount is only a trivial surcharge relative to the price, sans restaurant markup, of the kind of fine or rare wine such a policy intends to accommodate. The goal should be to encourage the enjoyment of truly top-tier wines that would further honor Flores’s cuisine but whose presence on the restaurant’s own list would hardly make sense.

Overall, Kasama’s beverage program is hugely successful for such a new restaurant. Few openings in Chicago have the capability to stock back vintages, yet the selections here show how you can make the most of what’s on the market by securing the right producers.

With the drinks settled, the tasting menu begins.

The opening dish, titled “kinilaw,” arrives hidden under a cloche in a stemmed dessert bowl. The name, which literally means “eaten raw” in Tagalog, refers to a preparation of marinated raw fish that is “indigenous to the Philippines” and can be thought of as an “ancient Filipino ceviche.” The basic recipe, which is thought to be more than one thousand years old, is typically served as a pulutan or finger food. Fish like tuna or mackerel often feature, being cubed and combined with ingredients like chilis or tomatoes. Classically, coconut vinegar forms the marinade with an additional amount of coconut milk sometimes incorporated.

With this bit of background in mind, Flores’s take on kinilaw is decidedly refined. A cloud of smoke reveals a scoop of Golden Kaluga caviar and a quenelle of hamachi tartare flanked by a healthy dollop of coconut cream. The dish has also featured unidentified, pale-colored flavor pearls before, but they have been omitted from more recent renditions. That, you think, is a wise decision, for it concentrates the textural experience by avoiding something that replicate’s the caviar’s subtle mouthfeel.

Kasama’s kinilaw transcends the recipe’s cubed fish form by processing the amberjack into something more like a fine paste. The hamachi glides across the palate, its naturally buttery texture serving to cushion the orbs of roe. That ensures the Kaluga can really stand out; however, the coconut cream should not be discounted. Its airy, enveloping consistency helps distinguish the tartare’s veins of flesh and fat while further enhancing the caviar’s impression on the tongue. (The spoon that accompanies the dish, it should be mentioned, features a clever set of dimples on its underside that, itself, winks towards the texture of the roe).

With regard to flavor, the dish astutely lets the Golden Kaluga take center stage. The rich yet mild hamachi is buttressed by the sweetness of the coconut and a sour tinge of vinegar. That combination is pleasing yet moderate and allows the butter, brine, and nuttiness of the caviar to come through clearly. Personally, you might like for the roe’s accompanying flavors to be just a bit more pronounced so that the preparation really distances itself from other combinations of yellowtail with caviar. Nonetheless, you like the degree of decadence Flores achieves vis a sense of restraint. Served with a glass of Champagne, the dish makes for an elegant start to the meal.

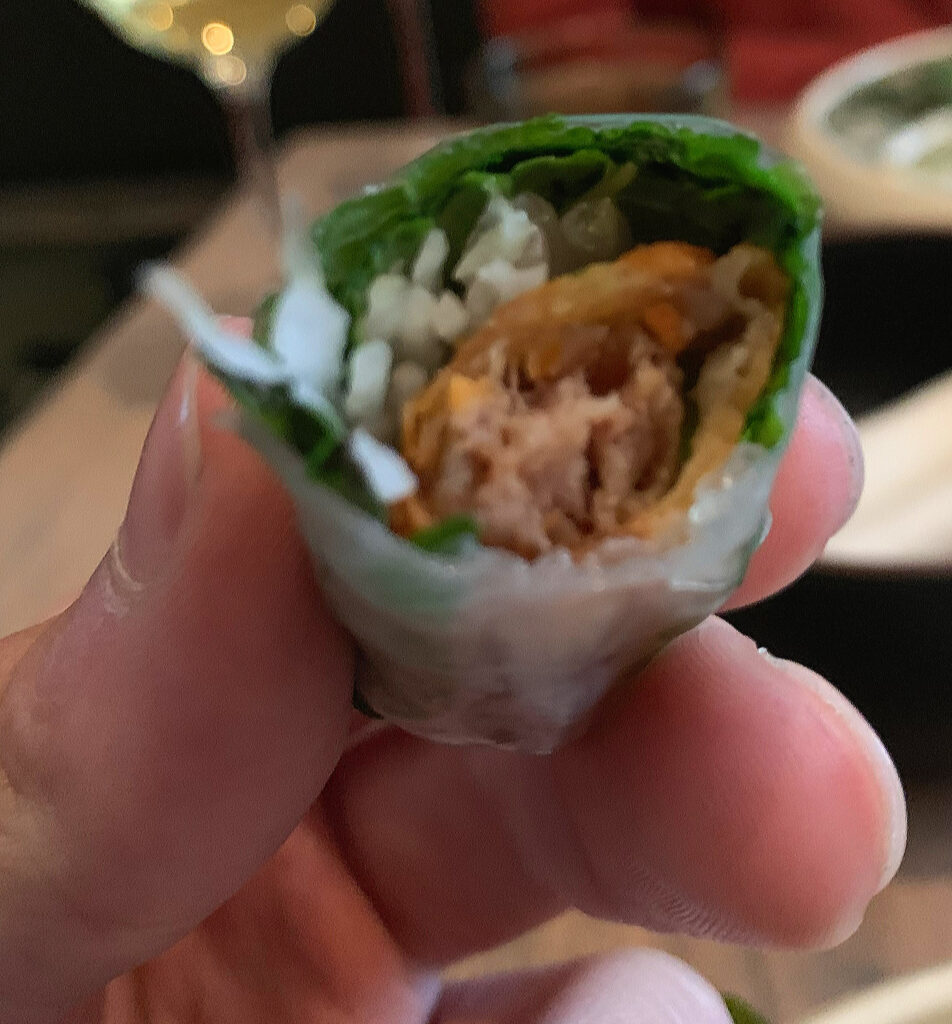

Next arrives a one-two punch of small bites that comprise two distinct courses on Kasama’s written menu. First, there’s lumpia, the “humble street food” that Flores has endeavored to prove can have a place on a tasting menu. It is placed opposite “talaba,” the Tagalog word for oyster. Though, in practice, you feel compelled to reach for the bivalve first, the chronology drawn from the dish’s verbal presentation and documentation should be respected.

Lumpia has been described as “the gateway to Filipino food for many,” and Kasama’s tasting menu originally planned to offer “two versions: a Shanghai version that’s fried and a fresh version served with an oyster (talaba) that uses Vietnamese spring roll wrappers.” Those who have visited the restaurant during the day have likely familiarized themselves with Flores’s “lumpia shanghai.” So, at some point, the decision was made to combine the “fried” and “fresh” versions into one composite dish. (Or, perhaps, Eater Chicago’s shoddy reporting simply misinterpreted what was being described).

You cannot blame them for assuming that the two styles of lumpia could not possibly coexist in one package. On paper, it sounds like a pipe dream or, at best, a stoner creation. But Flores has, in fact, found a way to artfully envelop his excellent fried spring rolls with a layer of herbs (Thai basil you believe) and an additional fresh rice flour wrapper. The innermost filling, within the fried shell, is made up of shredded radish and pork. The moment, upon taking a bite, that each of these layers collapse into each other, you know the dish is a textural triumph.

The subtle chew of the fresh outer wrapper yields to the leafy crispness of the herbs, the shattering crunch of the fried shell, and the more watery, subdued crunch of the radish with accompanying, juicy pork meat. The four layers work to embolden each other while the temperature contrast between the outer two and inner two further enhances the contrasting elements. An accompanying sweet chili sauce crowns the lumpia with a burst of hedonistic flavor that enlivens the more subdued character of the wrappers, radish, and herbs. Flores has achieved a rousing victory in his battle to elevate the beloved Filipino form. The tasting menu version of his lumpia possesses an intricacy and intensity that are the equal of any other fancy “wrapped-up thing” out there.

For his oyster, the chef has utilized the Kusshi and the Fanny Bay (both from British Columbia) on separate occasions. The bivalve is dressed with a sauce made from mezcal then topped with slivers of green mango, a green mango mignonette, and a spool of crispy onions. The whole package slides cleanly out of the shell, across the tongue, and down your gullet. Texturally, the plump meat yields to the soft crunch of the fruit and the shatter texture of the allium in a manner reminiscent of the lumpia’s own textural interplay.

Though the Kusshi is known for its clean flavor, the oyster’s mildly sweet and fruity notes meld nicely with the mango. Likewise, its hint of brine marries well with the onion and the mignonette. The Fanny Bay is similar in character though it displays a greater sense of minerality. That works nicely with the mezcal, which, though unorthodox, imparts a dose of smokiness that avoids detracting from the nuance of the shellfish. Overall, it’s a beautifully engineered bite that distinguishes itself among a litany of similarly composed items seen at fine dining restaurants across the city.

While presenting the raw oyster after the cooked lumpia seems disjointed a first glance, you think the ordering fits a larger continuity across the opening courses. Guests begin with the caviar (cool), then go on to the lumpia (warm), then slurp the oyster (cool), and finally move on to a more substantial warm dish. The rest of the menu, up until the closing halo-halo, is also warm. However, the opening dichotomy of hot and cold bites forms a free-flowing, tantalizing start to the meal that avoids the kind of abrupt transition typically seen in fine dining. There’s a real “wow factor” to Flores’s first three creations, and their staging ensures they each make a big impression.

The next dish, titled “nilaga” (or “boiled” in Tagalog), refers to a range of traditional Filipino meat stews made with beef or pork, vegetables, and white rice. The “most basic” vegetable used in the recipe, alongside potato, is cabbage, which Flores has made the focus of his preparation.

In essence, the chef has deconstructed the stew by separating it into two principle components. In a small bowl, guests receive a serving of shredded and braised cabbage that obscures a couple slices of A5 wagyu beef and a bottom layer of short-grain rice. An accompanying ceramic cup contains a seasoned beef broth that is meant to be sipped between bites.

In early renditions of the dish, the cabbage has possessed a lighter tone and done less to disguise the other components. Over time, however, Flores has adorned the leaves with a charred crust while stretching them more carefully across the surface of the bowl. This change has made for a greater sense of discovery as you penetrate through the top layer of vegetable to reveal the morsels of wagyu and pleasing reservoir of rice at the bottom. That char, of course, lends the dish a slightly bitter tone that accentuates the sweet, buttery flavor of the braised cabbage. It also plays well against the luscious, though only subtly beefy, wagyu.

The soft crunch of the charred cabbage leaves, melting quality of the steak, and absorptive nature of the rice achieve a stick to your ribs sensation that is, indeed, reminiscent of stew. The accompanying cup of broth is flavored deeply with beef and spice, delivering a soothing sensation that, drank in turn, helps complete the illusion. Principally, it helps deliver an added intensity of flavor that you think the bowl of (comparably) dry components demands. In that respect, the two elements that make up the deconstructed nilaga do, indeed, complete each other.

But you would like for the bowl of cabbage, wagyu, and rice to contain one or two more accompanying flavors from the pantheon of ingredients that may feature in the recipe. For, by still relying on the broth to deliver the principle savor of the stew, you question what is gained by separating the components in the first place. As it stands, the flavor of the cabbage is pleasing but not exceptional. The preparation leans on the luxury totemic status of the wagyu to distinguish itself when a more humble cut of beef could demonstrate greater character and technical skill. Nilaga should not rely on such an omnipresent interloper to assert its greatness, for that sells the recipe’s own heritage short.

However, the most recent rendition of the dish has smartly emphasized the presence of bone marrow more than the wagyu. In doing so, Flores references the manner in which his father would skim the marrow that rose to the top of the nilaga and mix it into his rice. This familial reference is not only charming, but it better serves to connect the deconstructed bowl of cabbage to its broth. The process of transferring the marrow over from the soup and into the rice forms a jumping off point for separating the other ingredients too. Of course, the wagyu is still present, but it forms more of a welcome surprise rather than the “star.” It benefits from the addition of some finishing salt that helps the combination of cabbage, rice, and beef stand on its own without the broth. The preparation, thus, is now more firmly anchored in a particular bit of nostalgia rather than an effort to refine the recipe via luxury ingredients.

The next course on Kasama’s tasting menu is titled “siomai,” the Tagalog spelling of the Chinese shumai, a “popular dumping which has made its way to the heart of the Philippines as evidenced by the hundreds of stalls, eateries, and restaurants who serve them.” Shumai are classically filled with ingredients like pork, shrimp, or mushroom and steamed.

In terms of composition, Flores’s siomai is wide, flat, and folded only once rather than formed into a tight pouch. For the dumpling’s filling, the chef opts to use duck. The protein seems to be a fitting choice since mallards are native to the Philippines and used, among other things, to make balut, a popular street food made from the bird’s fertilized eggs. The duck’s flesh is paired with its liver and tucked into the siomai, which is placed at the bottom of a shallow bowl along with a few pickled mushrooms. A sauce made, you think, with calamansi juice and a smidge of chili garlic paste complete the presentation.

Attacking the dish, the dumpling strikes the palate somewhat like a noodle. You chew through the thin ends of the wrapper that are coated in sauce before striking the dumpling’s duck and foie gras nucleus. There, the siomai unleashes its most intricate texture as the tender meat, oozing liver, double layered wrapper, and chunky chili paste combine. One of the slices of pickled mushroom, the thinnest of which closely matches the mouthfeel of the wrapper, might find its way into the mix. Or, perhaps, your tongue will latch onto one of the tiny fungi caps for a subtle, contrasting crunch.

The whole experience feels wet and slippery with juices that run down your chin. The flavors are deeply savory with supporting notes of heat and sourness. All in all, it’s a comforting dish built on a nostalgic form. It allows the menu to tell a story of Chinese influence in Filipino cooking. Yet it falls short of being an exemplary dumpling of the sort that would shine in a contemporary Chinese or broadly contemporary American meal. That is to say, the siomai is an enjoyable interlude that serves the tasting’s overall structure but fails to make a lasting impression. The foie gras, while it lends the tender duck meat an added degree of richness, seems appended to the dish arbitrarily (as opposed to the beef liver spreads that feature in the cuisine). It, like the wagyu beef in the nilaga, embraces luxury from without rather than generating that sense from somewhere within the culture.

However, also like the nilaga, you have witnessed a degree of growth to the siomai over time. The most recent preparation has trimmed the dumpling’s elongated wrapper and offered a smaller, more cohesive package that draws greater attention to its filling. That makes the duck and foie gras elements feel more substantial, and you have found there is now also a greater undercurrent of sweetness that makes the sour notes at hand absolutely transfixing. That sweet-sour combination serves, really, to unlock a deeper flavor to the liver that you felt had been missing (and that justifies its presence in the recipe). With continued refinement of the form, you think this dish can soon fulfill its potential!

Flores’s next course showcases the “unofficial national dish in the Philippines,” adobo. The term itself is drawn from the Spanish word adobar (“marinade,” “sauce,” or “seasoning”) and refers to a cooking process in which meat, seafood, or vegetables are marinated in a blend of vinegar (often from palm sap or sugarcane), soy sauce, garlic, bay leaves, and black peppercorns before being browned and simmered in the same mixture. Filipino adobo distinguishes itself from Spanish and Latin American versions by omitting ingredients like chilis, paprika, oregano, and tomatoes. Still, the Philippines possesses an array of regional variants that incorporate additional elements like coconut milk, turmeric, or annatto.

Kasama’s take on adobo chooses mushroom as its star. The dish centers on the maitake species of fungus native to China and also known by the name hen-of-the-woods or, literally, “dancing mushroom.” The ingredient is prized as a delicacy for its deeply earthy and peppery flavor with an intricate texture drawn from a tight structure of slender caps and stems.

Flores’s maitake is given the adobo treatment and arrives at the table boasting a browned stem with nicely charred tips. The mushroom sits in a shallow pool of its marinade, which also lends the flesh of the fungus an attractive sheen. The dish is finished with a frothy mussel emulsion made using an iSi siphon, the kind of technique that hearkens back to the chef’s time at Oriole.

The presentation is beautifully simple, celebrating the adobo technique at its most refined. The use of the mussel emulsion, too, is an elegant way of doubling up on the form, for the bivalves feature in their own popular preparation titled adobong tahong. The maitake cuts and eats cleanly while retaining a faint bit of crispness that helps accentuate its fluted structure. The mushroom’s earthiness is accented by the mussels’ own subtle undertones of fungal flavor, which then yield to a faintly sweet finish.

The flavor combination is intelligent, but it does not captivate you. Instinctually, you expect such a concentrated adobo form to deliver a melt-your-face-off level of umami. (Actually, you expect any such simple presentation of mushroom to regale you with a sense of intensity). Flores, instead, has opted to show restraint. The dish is mild-mannered and respectable. It is fit to sit at the table of grande cuisine. Other diners who possess a deeper nostalgia for adobo will have to decide if they think the dish does the technique justice. However, knowing that the chef could have chosen something other than mushroom to be the star, you question whom he is cooking for.

As it stands, the course feels like critic bait, a conceit made towards guests who find adobo’s usual intensity, its ample meatiness, to be uncouth. Whenever fine dining opts to refine something familiar, that recipe must also display a corresponding concentration of its essential flavors. The chef has designed a striking plate built on a thoughtful blend of flavors but that fails to erupt with pleasure. You are left with a feeling of sparseness, rather than joy, upon encountering such a signature of Filipino cuisine.

Nonetheless (and you have found this to be a recurring theme with the dishes you have critiqued), the most recent version of Kasama’s adobo has satisfied the sort of powerful umami you longed for. Such a difference could be due to some slight variation in the mushrooms themselves, but it felt as though both the marinade and mussel emulsion had fundamentally been dialed up. They imparted a lip-smacking quality that, for once, helped you overlook the recipe’s lack of meat.

Kasama’s next dish, titled “sinigang,” is one of your favorites. It delivers just the sort of decadence you are after and does so while embracing an even more dramatic deconstruction than seen in the nilaga. Sinigang literally means “stewed [dish]” in Tagalog and refers to a sour and savory Filipino stew characterized primarily by a tamarind base. Variations of the recipe are distinguished by the ingredients that substitute for this base (like guava, unripe mango, calamansi, or watermelon). However, modern Sinigang typically comprises meat or seafood that is stewed with tamarind, tomatoes, garlic, and onions.

Flores’s version, for all intents and purposes, is a salmon dish. It comprises a poached fillet of the fish that is dressed with a tamarind beurre blanc and topped with its smoked roe. Salmon skin chicharrónes, perched on crumpled paper in an accompanying bowl, complete the presentation.

Relative to the nilaga, in which the dry and wet components of the stew were separated, the deconstructed sinigang still amounts to a single, cohesive dish. Relative to the adobo, in which intensity of flavor was dialed back for the sake of refinement, the salmon marries elegance with a powerful sense of savor. The fish possesses a rich, buttery texture that breaks into glistening flakes that glide across the tongue. Its orange orbs of roe come along for the ride and pop themselves against your palate. The enveloping tamarind beurre blanc coats the fillet well without ever seeming heavy. It unleashes a sweet, tangy flavor with milky and caramel undertones that combine with the smoky-briny roe to achieve a sublime savory sensation.

Some may find the sauce to be too decadent in the same way Oriole “2.0’s” sablefish preparation can be perceived as such. However, for you the dish strikes a wonderful balance that asserts how the essence of sinigang can be used to imbue a larger piece of protein with a transfixing array of supporting flavors. Flores concentrates the best parts of the beloved stew and succeeds in showcasing them within a refined form. The crisp chips of salmon skin, while texturally sound, have sometimes lacked that same “wow” factor. However, a dusting of tamarind has recently helped enliven the chicharrónes and connect them to rest of the preparation. Now they form a pleasant diversion from the luscious mouthfeel of the salmon and serve to underline what is a superb preparation.

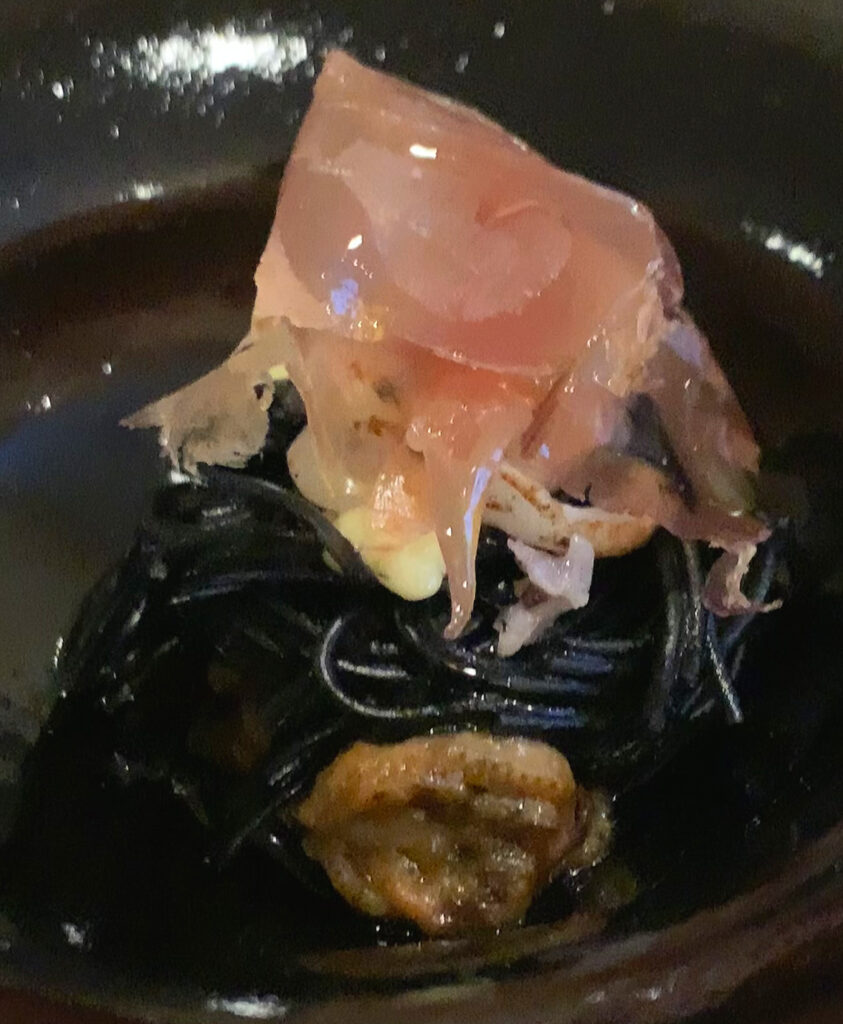

Kasama’s next course, “pancit en su tinta,” takes its name from a Chavacano (Spanish-based creole language) term for a dish from Cavite titled pancit choca en su tinta. Choca is the Chavacano word for squid while pancit refers to a range of traditional noodle dishes in Filipino cuisine. Thus, pancit chocoa en su tinta means “noodle with squid in its own ink.”

Though the recipe classically utilizes rice vermicelli, glass (or cellophane) noodles are a common variant. Flores chooses the former, which are fittingly stained black by way of squid ink. They are joined in a bowl by rings of sautéed squid, preserved scallops, and a slice of serrano ham (which substitutes for the crushed chicharrón that typically tops the dish). Readers may remember that the chef framed his use of the scallop conserva as a decolonial gesture. Both it and the serrano reflect Spanish luxury items that are being claimed, in an ironic yet spirited turnabout, to elevate a traditional dish from the colonized native Merdicas people.

Structurally, the pancit en su tinta starts with the thin slice of ham, which somewhat obscures the other ingredients. Upon being moved, the serrano reveals the glistening white rings of squid that sit atop the spool of black noodles (that blend perfectly into the dark bowl). The scallops, colored by the tomato and paprika sauce they are canned in, peek out from the very bottom.

The dish, in essence, is all about texture: the gossamer, melting ham, the bounce of the squid rings, the al dente quality of the thin noodles, and the soft, smooth preserved scallops. Between the serrano and the conserva, there’s a good deal of salt (which on one occasion proved too much). However, you do not generally find the preparation overseasoned. Rather, you simply struggle to portion each of the elements to make a cohesive bite. It’s easy to get the entire piece of ham in one go, leaving a few pieces of squid to compete with the denser, more flavorful scallops as they get tangled in the noodles. There are a couple pockets of a creamy sauce that, based on the dish’s traditional accompaniments, you will guess is made from calamansi (a small citrus fruit whose flavor is likened to a combination of mandarin orange and lime). But, perhaps due to the fact that you do not mix the components thoroughly (or arrange them carefully into bites), the composition ultimately feels like a hodgepodge.

No doubt, the “noodle with squid in its own ink” element is done well. You simply do not find that the scallop and serrano add as much to the dish as one would expect. Yes, they make a valuable statement regarding the shifting tides of luxury and how Filipino cuisine can symbolically transcend the country’s colonial past. But the textural contrast classically provided by crushed chicharrón seems like it would make for a more engaging experience than the limp ham, and you do not find conservas to always be the gourmet products they are built up to be. (The canned seafood has slowly established a pervasive presence across Chicago restaurants, and you have started to question its luxury status altogether).

Cleverness aside, the squid and noodles should form the basis of a dish that aims more intently for cohesiveness and pleasure. You think ridding the dish of any Spanish influence for the sake of attaining some higher deliciousness sends a stronger, if more nuanced, message.

The next course, nonetheless, is one of Kasama’s strongest, and that is hardly surprising once you hear that Kwon has collaborated with Flores on one of its elements. The composition is titled “kare-kare,” a Filipino stew whose name derives from “curry.” Though the exact origin of the dish is uncertain, it is characterized by a “thick savory peanut sauce” (from the addition of ground roasted peanuts or peanut butter) and is traditionally made from a base of “stewed oxtail, beef tripe, pork hocks, calves feet, pig’s feet, various cuts of pork, beef stew meat, and occasionally offal” with vegetables. It is said that “any Filipino fiesta is not complete without kare-kare,” and you find the degree of savory flavor the ingredients suggest to be mouthwatering.

As with the sinigang, Flores deconstructs the stew by centering his preparation around a piece of protein. The chef picks lamb belly, a highly appealing choice. Guests receive a good portion of the meat, which boasts a beautifully crisped skin, perfectly rendered fat, and succulent flesh. (That element of gushing fat seems particularly clever given that kare-kare develops a gelatinous quality as its meat cooks). The lamb receives a thick coating of a sauce that replicates the “peanut curry” before being topped with small chunks of radish and leaves of mint. An XO sauce made from bagoóng (a Filipino fermented shrimp condiment) and a dollop of eggplant purée serve to further dress the meat. The dish’s crowning touch comes by way of a warm laminated flatbread made by Kwon.

You think this course really fulfills the potential of Kasama’s tasting menu form. It refines a classic Filipino preparation while pulling few punches as to its essential flavor and maintaining a sense of generosity. It marries the main plate with a custom creation from the restaurant’s baker extraordinaire, and it even features that cocktail pairing you mentioned earlier (“kalabasa,” made with Suntory Toki, carrot juice, pumpkin seed orgeat, and guyabano).

The lamb’s texture, as you have already noted, is sublime. The meat’s rich, gamy flavor is met by a peanut sauce that lives up to its immense umami potential. The XO sauce and sweet-earthy eggplant spread only enhance the savory explosion, yet the level of salt is expertly kept in balance. The flatbreadexhibits a stunning degree of flakiness that, as it is used as a vessel for the lamb and its sauces, imparts an endless degree of textural intrigue. It crunches and cracks and combines with each of the elements to form a cohesive, highly pleasing package. The cocktail, imbued with sweet, sour, and nutty notes, cleanses the palate with a full, milky texture while striking some of the dish’s undertones with its finish.

Kasama’s kare-kare should form a model for the kind of technical, nostalgic, and multidimensional course that realizes the restaurant’s vision. The dish presents a singular, confident vision of Filipino cuisine that owes nothing to international luxury. It delivers the kind of deliciousness destined to make a believer of any diner that encounters it. What a great accomplishment.

The final savory preparation of the meal comprises that totemic luxury ingredient par excellence, A5 wagyu. Flores titles the course “bistek,” in reference to bistek Tagalog, a Filipino dish made from strips of tenderized, salted, and peppered sirloin that are slowly cooked in a mixture of beef jus and calamansi juice then topped with raw (or slightly softened) onions. The chef embraces the natural kinship between that recipe and a litany of “steak and onion” combinations seen across myriad cultures. It’s a unifying form that highlights how human foodways converge on and come to value the same fundamental combinations.

By harnessing wagyu beef, the dish is decidedly simple. A chunk of the prized steak sits towards the center of a shallow bowl. It is garnished with a few flakes of salt and dressed with the soy sauce and calamansi juice that feature in bistek Tagalog. The onions, rather than being raw, are caramelized to an extreme degree.

The wagyu is cooked to a glistening medium rare and displays a melting quality on the palate as its bursting ribbons of marbling gush. The salt, along with just a touch of outer char, is effectively applied to draw out the beef’s delicate flavor and emphasize its umami. The beef jus plays a similar role while the intensely tart, subtly floral calamansi serves to heighten the pleasure through contrast. The onions, however, are truly the star. Their deep savory sweetness strikes right at your heart, stoking a sense of nostalgia that Flores is right to prize.

Though you often decry wagyu beef as a crutch, Kasama, in a manner reminiscent of Oriole, knows how to emphasize the ingredient’s decadence. The juxtaposition of an expensive steak being flavored in the humble bistek Tagalog style represents an effective subversion of its luxury status. But, perhaps, you would still rather see such interloping elements done away with altogether. Apart from the calamansi and onions, the “salted,” “peppered,” and “tenderized” elements of the traditional recipe are what intrigue you. Such techniques, of course, were meant to heighten the appeal of more humble cuts of meat. Yet they also lent the dish’s flavors and textures a particular character that should not necessarily be traded away for a more fashionable product. You would love to see the wagyu make room for some other type and cut of beef that could encourage a more involved, distinct preparation rooted even more firmly in Filipino cuisine.

The first of Kasama’s desserts showcases one of Kwon’s classic forms: the croissant. You recall tasting one rendition during the pastry chef’s time at Oriole that featured a filling of Ashbrook (a sweet and creamy raw cow milk cheese) with rosemary apple butter. Her present version, titled “truffle croissant,” is filled with Délice de Bourgogne (a mushroomy triple-cream cheese) and honey. The top of the pastry is lightly glazed and speckled with rocks of Belgian pearl sugar. Kwon then completes the presentation with shaved or microplaned truffle tableside.

It’s a great moment, since Flores naturally has the chance to greet each table as he delivers savory food, and the restaurant’s devotees are sure to want to say hi to his better half too. Kwon marks the meal’s denouement with a personal touch and pleasing flourish that frame a phenomenal bite. Indeed, you find there are real peaks to the savory portion of the menu, but this croissant is the kind of guarantor of pleasure that fine dining so rarely achieves. (You are reminded of Ever’s milk or dark chocolate donut, which, nonetheless, is clearly inferior. Only Smyth’s mushroom custard with sauce royale and Oriole’s own Délice de Bourgogne soufflé are as consistently sublime).

Visually, it is easy to see how much Kwon has continued to refine her lamination technique since even a few years ago. The smooth segments of the earlier croissants have now been replaced by craggy ribbons that run from head to toe. The shell of the pastry shatters cleanly, revealing the interior filling of creamy, tangy cheese and honey. As you chew, that rich coating envelops the croissant’s delicate layers. They yield to the tiny strands of truffle (the microplaned style is always superior), which can impressively be perceived clearly on the palate. The bits of pearl sugar, when they finally reach the tongue, offer a valuable contrasting texture and burst of sweetness that amplifies the filling.

Structurally, the pastry is perfectly engineered to offer a crisp, gooey, savory-sweet sensation of stunning length. It will make a believer out of customers who might otherwise not touch a soft-ripened cheese with a ten-foot pole. The truffle croissant makes for a delightful, thoroughly crowd-pleasing portion of the meal that is made even better by the accompanying coffee service. Kasama deserves credit for loosening its thematic fidelity for the sake of honoring such an ultimate expression of pastry technique. It reminds you that delivering deliciousness, first and foremost, remains the goal.

The next dessert, titled “banana-cue,” returns to the menu’s Filipino influence. The course is inspired by the popular street food of the same name, in which Saba bananas (a rich, sweet variety whose flavor is compared to sweet potato when cooked) are deep fried and coated in caramelized brown sugar. For Kwon’s version of the recipe, she simply caramelizes the fruit and pairs it with a brown sugar diplomat cream. Well, you shouldn’t say “simply,” for her banana is an image of perfection. It displays an impossibly deep brown color with a stunning lacquered finish. It seems every bit equal to Flores’s caramelized onions: an extreme application of technique that yields unparalleled flavor.

Tucking into the banana-cue, you are struck by how easily it cuts. The caramelization is not hardened nor overly chewy; rather, the fruit retains an appealing warmth and softness. On the palate, it displays the kind of dense and earthy sweetness that suggests the sweet potato comparison is sound. The intensity of flavor is marvelous and benefits from the added kiss of sweetness and lingering mouthfeel of the sugar crust. The diplomat cream surrounds the banana’s own rich texture with a cleansing, fluffy cloud of dairy. Nonetheless, the molasses tone of the brown sugar resonates with the caramelized finish. Kasama’s banana-cue is simple, delicious, and reflects a graceful refinement of a rather fun snack from within the cuisine.

The last course of the tasting menu tackles that “iconic Filipino dessert” called halo-halo (Tagalog for mixed), a cold dessert made with shaved ice in the Japanese kakigōri style. Traditionally, the recipe is flavored with evaporated or coconut milk and topped with ingredients like ube jam, sweetened beans, coconut strips, cheese, toasted rice, tapioca pearls, jackfruit, taro, sweet potato, flan, and ice cream. Regional variations abound, giving Kwon a wide berth with which to design her own version.

The pastry chef, once more, opts for simplicity. She centers her halo-halo on an Asian pear granita that is topped with pandan ice cream, freeze-dried segments of orange, blueberries, and bits of toasted brown rice. The bottom of the bowl hides a serving of “Tita Lolly’s leche flan,” a family recipe for the popular caramel custard whose presence in the recipe is utterly charming. It tastes good too.

You typically find shaved ice desserts to be unappealing due to a lack, in some part of the dish, of adequate flavoring. However, by basing the dessert on a sweet-tart granita, Kwon ensures every bite is appealing. The Asian pear ice, which texturally forms an appealing slush, melds well with the nutty and coconut flavors of the creamier ice cream. The bits of toasted rice and crunchy chunks of orange shatter a bit more coarsely than the granita, forming an engaging textural experience. The same goes for the blueberries, whose bursting juices also serve to flavor the ice. Ultimately, Tita Lolly’s flan anchors everything with a rich, mouth-filling expression of caramel that ensures the meal ends on a note of decadence.

By your measure, Kwon scored a hat trick with her desserts! And that includes, notably, the ube and huckleberry Basque cake guests are given to take home. (Kwon’s parting sweets, when she worked at Oriole, were the very best of their kind you had ever encountered. It is heartening to see that Kasama carries on the tradition by providing the kind of goody that returns guests, whether later that night or the next morning, to the same state of bliss they felt during the meal).

Thoroughly satisfied, you pay, collect your belongings, and ride a tide of warm wishes out of the building and back onto Augusta. The stern edifice that greeted you looks even more imposing under the cover of darkness. Now, however, you know its secret. The fortress structure shields a glowing expression of hospitality that would set the block alight if not carefully contained. Kasama’s creative expression must be met intimately in those cloistered confines, for it is only there, passing through a solemn threshold into another world, that the heart and soul that drive the enterprise can truly strike. The place that everyone in Chicago so desperately, passionately loves is the real deal. When it finally comes time for you to visit, all the buzzing seems to stop and the staff, the chefs disarm you with just how earnestly they ply their trade.

The sort of rampant media hype Kasama possesses typically motivates you to look closer and find what fly-by-night “critics” are destined to miss. At the same time, you endeavor not to take a contrarian position for the mere sake of standing out from the crowd.

When the average consumer lacks confidence in their own perceptions, as is the case in fine dining, a carefully constructed narrative can make a pretty good meal seem close to perfection. The emotional underpinnings of a chef’s story and creative vision do, indeed, affect the perceiver’s critical posture. Most diners, by the simple act of spending hundreds of dollars, want to believe. They want the experience to fulfill all that they’ve heard and read. They show up ready to play their part, and the food, whether it’s “good,” “great,” or truly “superlative,” can devolve into so much window dressing. Cuisine, in such a case, serves an occasion that transcends the cold study of gastronomic achievement. It forms the backdrop of a fashionable cultural touchstone that need only please and not amaze so long as the right people can post pictures of their enjoyment.

At a structural level, Kasama’s ambiance is pleasant. Though you commented on the chairs, they are, indeed, serviceable. Plateware, glassware, and utensils show fine quality (like Misen knives) with a wink of creativity (like the dimpled caviar spoon). The beverage program, from wine pairing to bottle list, is beautifully curated and offers top value. Service demonstrates an effortless warmth and nearly faultless technique. The presentation of each course has grown in fluidity and detail over time (a key pillar of the experience as it relates to the restaurant’s educational goals). Small errors, like forgetting the correct handedness for place settings, are eventually remedied. They are also quickly forgotten by way of attentive refills and top offs to your pairings.

The kitchen’s pacing, likewise, is expertly managed. Across all five of your visits, the thirteen courses have been consistently served in just under two hours and thirty minutes. You have never felt you were consciously waiting for the next dish to arrive; rather, its appearance always maintained a sense of unexpected delight.

With regard to Kasama’s cuisine, you must first state that you believe Flores is supremely talented at balancing flavors. On first encounter, you found his tasting menu to be uniformly delicious and totally dialed in to the exact level of seasoning that suits your palate.

Of course, once the novelty effect diminishes, it becomes easier to find fault. Courses like the kinilaw, lumpia, talaba, sinigang, kare-kare, and each of Kwon’s desserts remained ironclad in their quality across visits. However, the nilaga (though always enthusiastically received by your dining companions), siomai, adobo, and pancit en su tinta began to stand out as needing a bit more work to reach the same heights as the rest of the meal.

Flores admits that he directs his attention towards improving the menu’s weakest dish at any given time. For the nilaga, you found that framing the dish as one of bone marrow and rice made more sense. The chef tightened the technique used to form his siomai and found a way to draw a deeper flavor from the mushroom adobo. When everything else looks and sounds the same, it is easy to wonder just how much the recipe really has changed (as opposed to your perception of it). But for the supposedly “weak” dishes to make such a big impression on your final visit suggests some meaningful tinkering had been conducted. At the very least, the nilaga, siomai, and adobo felt equal to the other preparations you have long favored.

The pancit en su tinta remains a step behind the other courses, yet you must admit that you continue to enjoy scarfing the noodles down. It is the presence of the serrano ham and scallop conserva that perplexes (though the ingredients’ symbolic value is clear). Likewise, the pride of place given to A5 wagyu in the bistek preparation, however delicious, was bound to provoke you. The power ascribed to certain luxury ingredients is, in some sense, an extension of cultural imperialism. While commandeering them for a noble purpose (the celebration of native Filipino forms and flavors) can be celebrated, you find such products constrict expression more than they free it.

Viewing modern Filipino cookery through a familiar, Michelin-tinted lens will always mean denying the culture’s power to redefine notions of “luxury” and “fine dining” altogether. That extends to all the totems: caviar, foie gras, wagyu, and even fine wine.

There exists some population of diners, perhaps, for whom the presence of such luxurious ingredients on a Filipino-inspired tasting menu signals that the cuisine has finally arrived, that it is finally worthy of their time and respect. These narrow, backwards palates are not worth wasting one’s talent on. They do not, in their pigheadedness, deserve access to all the hidden treasures of the cuisine. For they can only force it into an existing mold of tacky expectations rather than go, in good faith, to meet it.

Yet Flores and Kwon deserve to earn their star and cement years of hard work. You cannot fault them for serving some of the same “guarantees” that Chicago chefs in far more comfortable positions have clutched onto for years. Kasama, there is no doubt about it, has succeeded in crafting an opening tasting menu that honors its culture, the personalities of its chefs, and the tastes of its city.

The restaurant is already symbol that is well on the way to becoming a legend. The current roster of dishes are worthy of being served to any and every customer that follows all the hype to its door. But, you wonder, will succeeding by European-derived fine dining standards impart a pressure to keep playing the same game in perpetuity? Or will that sanction, once it is earned, open the door to a deeper, more unapologetic indulgence in Filipino forms and flavors that push customers and the cuisine into totally new territory?

Cultivating that latter kind of creativity and successfully serving it to your audience, even if it means getting rid of the luxury totemic “guardrails,” is the true domain of a “best in the world” restaurant. It remains to be seen when and if Kasama will write that chapter, but there can be no question that it is one of Chicago’s finest restaurants.