You have minced few words regarding Boka Restaurant Group over the years, particularly when it came to the demise of Bellemore and that restaurant’s replacement by the decidedly tepid Alla Vita. Back then, BRG founders Kevin Boehm and Rob Katz were still fresh off the back of their 2019 James Beard Award for Outstanding Restaurateur(s), having beaten Hugh Acheson, JoAnn Clevenger, Ken Oringer, Alex Raij, Eder Montero, and Ellen Yin to take home the prize on their fourth attempt. But, rather than channeling that national affirmation toward developing the finest concepts Chicago had ever seen, the Boka honchos seemed set to ease up and cash out.

Sure, there was a pandemic to contend with somewhere along the way: decisions—hard ones—were made and the BRG portfolio of properties suffered the same exodus of talent that touched groups of greater size and restaurants of greater acclaim alike. Crown jewels like Girl & the Goat, formerly the kind of concept that defined the city’s dining scene, came back floundering. Izard’s eatery, as proclaimed by Adrian Kane (in what amounts to an all-too-rare critical reevaluation of Chicago’s sacred cows), was “no longer a must-visit.” Yet, from this decrepit state (perceivable long before the article in question), Boehm and Katz went ahead with a Los Angeles edition of the concept in 2021. The opening drew an even harsher review from one of Kane’s colleagues, and you wondered whether Izard and her backers would tank the Windy City’s gastronomic reputation out West.

Nonetheless, your favorite aggregators would reveal that the great mass of mainstream consumers find Girl & the Goat Los Angeles positively charming and that the Chicago branch (while perhaps not quite the impossible reservation it once was) still manages to please the majority of its patrons. As always, a few voices pierce the veil: referencing a lapse in standards that could only be perceived by those who had eaten Izard’s cuisine—and felt the hospitality culture she had conjured—at its peak. Yet those diners are destined to move on, and their seats, primely positioned in some of their respective cities’ most popular neighborhoods, are destined to be taken by a new generation of novelty-seekers that does not know any better.

It may seem like you are nitpicking: complaining how the restaurant that was once “excellent” is now only “good.” However, this is the insidious, slow-burning fashion in which brands begin to sell out. Trading on a hard-won reputation, efficiency slowly displaces consistency until expectations are effectively lowered and more money can be made while offering an inferior product.

This reminds you a bit of Bellemore, a restaurant that began with relative promise but became shackled to a disappointing (but viral) “Oyster Pie” and a “bright, bold, [and] beautiful” kind of cookery that seemed to consciously reject the more hedonistic style of cuisine on which chef Jimmy Papadopoulos made his name. The concept, with its Studio K design, sure looked pretty but lacked any cohesive identity. The fussy plates contended that Bellemore was a serious™ dining establishment. They looked the part for BRG’s loyal coterie of conspicuous consumers. But textures, flavors, and the accompanying wine program fell far short of (dearly departed) Blackbird down the street. And the family meals Papadopoulos served during the pandemic—soulful, shareable creations that far surpassed his usual menu—never found a permanent place.

Bellemore would close, and BRG would give the property a cut-rate Kehoe Designs facelift and a murky “neighborhood Italian eatery” reimagining in 2021 courtesy of executive chef Lee Wolen. At a time when several new openings sought to engage with this cuisine, Alla Vita struck you as by far the weakest. Its pizzas, admittedly, impressed, but the food offered no clear perspective on the genre it had chosen. Service was perfunctory, wine (as always) offered nothing of note, dessert (particularly a version of tiramisu) was deeply flawed, and the restaurant just seemed concocted to rescue the profitability of a direly underperforming space. Relative to Bellemore, there was little risk—little need to sell the city on something (however vapid) that could at least be challenging. Now, with a burgeoning new office building across the street and lunch being served Monday-Friday, Alla Vita will have no trouble accomplishing its goal (though recent Yelp reviews suggest customers aren’t as undiscerning as they seem). You would just never confuse such a nakedly opportunistic, utterly shallow property as the product of hospitality luminaries.

Yes, that James Beard Award was meant to honor “creativity in entrepreneurship and integrity in restaurant operations,” but it presaged a descent into hackery. Los Angeles would be graced with a rehash of Cabra in 2022—part of a national partnership with The Hoxton. And, later that year, Boka Restaurant Group would sell a minority stake in its company to Levy: a group that once operated the legendary Spiaggia but, today, is defined by properties like the American Girl Café and a litany of lucrative concepts in Walt Disney World, convention centers, concert venues, and “arenas for all major sports leagues.”

BRG, in its own right, had already been expanding into stadium (and stadium-adjacent) dining via concepts like Dutch & Doc’s (later to become Swift & Sons Tavern). Izard, likewise, had already taken her This Little Goat brand to the United Center (partnering, as it happens, with Levy) via a taqueria. So, just as hotels had proven to be fitting venues for extensions of the BRG stable of chef-personalities (going back at least as far as Somerset), the Levy deal seemed like a sensible way to shoehorn the group’s intellectual property (diluted to whatever degree necessary) into other spaces with captive audiences. Considering the low standard of stadium food, this still probably makes for a net positive. However, it seems unlikely they’ll be opening their version of The Modern or In Situ any time soon.

To be fair, Boehm and Katz have seen notable success in New York City, a market in which The Alinea Group failed miserably and which, so far, only Brendan Sodikoff has seemed able to crack. (Though it should be remembered, at least as far as chefs go, that César Ramirez cut his teeth in Chicago at restaurants like Tru before meeting David Bouley and moving out East.) BRG’s Laser Wolf—a collaboration with Michael Solomonov and the Williamsburg branch of The Hoxton—earned a two-star review from Pete Wells and was alternatively titled “the restaurant of the summer.” Tables there book “months in advance,” and the concept has since been joined by K’Far (an all-day affair in the same hotel) and, even more recently, by Jaffa Cocktail + Raw Bar.

Back in Chicago, BRG’s biggest opening this year has been a trio of concepts within one historic building in Southport Corridor: GG’s Chicken Shop (from Boka’s Lee Wolen), Itoko (from Momotaro’s Gene Kato), and a relocated Little Goat Diner (from Izard). Such a roster seems rather formidable as far as Lakeview dining goes, but what appeal do such properties hold for the majority of Chicago diners? They each represent downscaled versions of their respective originals, brand extensions without much added depth, savvy means by which BRG continues to tap the local market without dreaming too big (or taking on too much risk). It’s the Alla Vita strategy writ large.

For a so-called “group of renowned culinary leaders who oversee a growing collection of acclaimed restaurants,” this seems like a natural next step. But it seems hard to ignore that New York City is home to BRG’s novel, more noteworthy restaurants as of late while Chicago and Los Angeles are stuck with the leftovers. And, with the group planning to start construction in Nashville next year and “keep expanding from there,” when will the Windy City ever see Boehm and Katz’s best work again?

Le Select, surely, was meant to throw a bone to Chicagoans—to affirm that BRG was not only partnering with glitzy chefs like Michael Solomonov in New York, but that the group’s founders could bring talent of a national caliber back home with them. That man was Daniel Rose, who had made his name crafting “market-driven” food at his 16-seat restaurant Spring in Paris’s Ninth Arrondissement (later reopened as a 28-seat restaurant in the First Arrondissement complete with a downstairs wine bar). Spring closed in 2017 after a little more than 10 years, but, by then, the American-born chef was also running La Bourse et La Vie (opened in 2015), a classic French bistro termed a “runaway success” by Michelin, in the Second Arrondissement.

He had also, in 2016, partnered with Stephen Starr to open Le Coucou in New York’s SoHo neighborhood. The restaurant, which you visited several times during its first few months of operation, was an immediate success. It was billed as a homecoming for Rose and a “gracious modern nod to fine European gastronomy.” It delivered one of the most romantic, delectable celebrations of classic French cuisine that you have ever encountered stateside, almost singlehandedly reviving the genre as something (though it never needs to be) fashionable. Le Coucou would earn the James Beard Award for Best New Restaurant in 2017 and help propel Starr to the Outstanding Restaurateur honor that same year. The concept would also earn a Michelin star in Bibendum’s 2019 edition of the Guide, an honor which it holds to this day.

Le Coucou was Rose’s first time cooking professionally in the United States, and, with the help of a (soon-to-be) Outstanding Restaurateur recipient, the chef knocked it out of the park. Why couldn’t Boehm and Katz, fresh off of winning the very same award, replicate some degree of the same success? Rose was born and raised in Wilmette after all, leaving for France shortly after his high school graduation. Le Select would represent the perfect homecoming, the capture of a big-name chef for the Chicago market, and a key piece of empire-building for both parties involved.

Of course, Los Angeles came first. BRG, in partnership with Rose, opened Café Basque in December of 2022 on the ground floor of The Hoxton. It marked a complement to the rooftop Cabra Los Angeles concept (much in the same way Cira does in Chicago) and received a similar (if somewhat lukewarm) reception: a 7.3 (versus 7.6 for Cabra) rating and a four-star Yelp average. This seems serviceable enough for a “hotel restaurant” (though it should be mentioned that Le Coucou, in its own right, anchors the 11 Howard boutique hotel). Besides, Le Select would occupy its own building, stand as its own complete concept, and promise a scale and scope of French dining BRG and Rose had never pursued before.

Speaking of his partners, Rose would say that “Boka survived the pandemic in a way that was very admirable,” and “that sets them up for a very strong future.” Boehm and Katz would bring in frequent collaborator AvroKO to remodel the 12,000-square-foot, 200-plus seat space (formerly home to SushiSamba and Bottled Blonde). They would assemble a team that included chef Audrey Renninger (from La Bourse et La Vie), chef de cuisine Jason Heiman (a Chicago local), and service director Cara Sandoval (co-founder and former general manager of Oriole) to help execute Rose’s vision. And they would even—despite all the glitz and glamour surrounding such a sprawling new opening—look to manage expectations at what would ultimately be termed a humble brasserie: “Le Select isn’t going after awards, but aiming for a French definition of perfection…. Diners are going to find dishes they’ll crave, which will lead to repeat business.”

The restaurant’s opening in late January of this year elicited all the usual pomp. BRG’s diehard coterie of socialites, influencers, and captains of industry turned out to christen the newest jewel in Boehm and Katz’s crown. A pretty setting and free-flowing Champagne did enough, as far as people with more money than taste go, to make a positive impression. Everyone, at the very least, got their photo op at Chicago’s hottest new restaurant. Rose made an admirable effort to connect with each of his tables, and it was heartening to see Boehm leading proceedings on the hospitality side (while Katz, in classic fashion, reared his head to dim the lights just the right amount).

You visited Le Select during its opening weekend and, again, about a week after that. As always, you kept an open mind despite misgivings about BRG’s recent business decisions. Plus, having enjoyed Le Coucou so much, there was no reason not to welcome its chef back home to Chicago with open arms. Though some have likened the AvroKO design to a Paris Métro station, you much enjoyed the scale of the room. One can feel the pulsating energy of the crowd and people-watch without attracting too much attention. That kind of anonymity, married with the sense that you are hobnobbing with important people, strikes at the core of the brasserie’s (as exemplified by places like Balthazar) charm. Likewise, while Le Select’s wine list is grossly overpriced, it does represent one of BRG’s finest offerings in some time (with producers like Bruyère-Houillon, Chandon de Briailles, and Coche-Dury featuring among close to 400 different bottles).

Even service, while something of a sticking point for many diners, proved more than adequate. (Though, admittedly, you qualified for the Boka Black Card program many years ago and enjoy an extra degree of attention on account of your wine buying patterns—an essential means of differentiation, for better or worse, when trying to stand out in such a large dining room.)

Yes, Le Select clearly aspired to much more than Alla Vita ever did and, thus, possessed the right foundation on which to succeed. However, shockingly, Rose proved to be the weak link. His food was not only executed poorly (a forgivable-enough sin at the time of opening especially given the loss of his original chef de cuisine), but the menu itself seemed to lack joy—almost as if the chef actively felt disdain for French cuisine. Based on Rose’s other work, you know that not to be the case, yet it was sad to see him plying tables with bottles of rum at dessert while Chris Pandel and Lee Wolen tried to salvage the actual operation of the kitchen. (In one particularly grueling episode—perhaps the most uncomfortable one you have ever experienced during a meal—the chef sang all three minutes of Benny Bell’s 1946 novelty song “Shaving Cream” to your stunned table.) Shills like Steve Dolinsky did their best to gloss over these flaws, but mentioning Le Select in the same breath as Obélix strikes you as downright criminal.

Why did Boehm and Katz fail in their partnership with Rose while Starr had wildly succeeded? Issues with adapting to such a larger scale of operation, adequately staffing/training/leading the kitchen, and perhaps a lack of recipe testing seem easy to pinpoint in hindsight. Or, quite simply, BRG had misjudged their partner’s potential to adapt his more refined style of cookery for the mainstream consumer altogether.

The collaboration certainly sounded good on paper, and Boehm and Katz deserve credit for bravely making a change when the situation—burdened by a slew of negative reviews—proved unsalvageable. In May, a little less than four months after Le Select’s opening, BRG parted ways with Rose in a decision that also affected Café Basque. A direct e-mail to Boka Black Card members titled “Culinary Updates Le Select” signed by the group’s founders revealed that, moving forward, the “culinary team will be led by Executive Chef Chris Pandel, Consulting Chef in Residence Lee Wolen, and Chef de Cuisine Pat Sheerin.” Rather politely, they added that, “as a result of this change, Daniel Rose is no longer part of the Le Select team.”

Turning the page, the e-mail announced that Pandel and his team “will be introducing a completely refreshed dinner menu” with the goal of offering “delicious and approachable French cuisine made for everyday dining”–a concept that “resonated” with the BRG honchos “from the start.” New items like a “Le Select Plateau” (seafood tower), “Spring Asparagus Toast,” “Escargot,” “Escargot Bolognese,” “Artichoke Ravioli ‘Nicoise,’” “Le Burger Americain,” “Trout Almandine,” and an expanded selection of steaks (along with a refurbished assortment of sides) affirmed that BRG was ready to coddle—rather than clunkily challenge—the palates of the mainstream consumer. You might term this a reversion to the “Alla Vita” strategy (even if Pandel’s menu, to its credit, remains a bit more ambitious than Wolen’s pizza, pasta, and chicken parm). However, when Boka invited its Black Card members back to Le Select in early June—offering a one-time 50% discount off the total bill through the end of the month as a kind of “extended Friends & Family”—it appeared that the group was willing to swallow its pride (and sacrifice some bit of lucre) to make things right.

Le Select, no doubt, marks an embarrassing chapter in Boehm and Katz’s hospitality careers (but one, admittedly, that they reacted to with decisiveness and class). You do not think the restaurant’s “reimagined menu of French classics inspired by Midwest methods and ingredients” is truly “brimming with creativity and innovation.” In fact, you will state once more that Le Select cannot hold a candle to its compatriot Obélix located just a handful of blocks away. But the concept is now certainly poised to become a fixture in its neighborhood by marrying its attractive ambiance and beverage program with more competent, approachable fare. It will, in time, banish any lingering memory of its poor opening and fade into being a stylish, if unremarkable brasserie.

Yes, while rivals like Lettuce Entertain You and Hogsalt charge forward with novel concepts, BRG floundered when bringing its newest chef into the family. Discounting the successful collaboration with Michael Solomonov out East, Boehm and Katz seem comfortable with mediocrity back home. The two founders have pursued their own personal projects (BIÂN and The Pearl Club respectively) while partnering with Levy and setting their sights on further expansion afar without the sense that they any longer look to enrich Chicago’s dining scene. The balance sheet might look good, but the concepts themselves—reboots, spin-offs, and cash grabs—are totally uninspiring.

This all leads you to ask: what about the Boka mothership, the crown jewel, the Michelin-starred original upon which the group’s fine dining credentials are based? Rather than put Le Select “2.0” through its paces—a trite story of improvement and compromise, no doubt—why not take aim at the citadel? You smell blood in the water, and, after all, Boka is celebrating its 20th anniversary this year. Does the restaurant, today, represent an enduring legend or reflect, in line with other recent missteps, BRG’s downfall? Whatever the answer, asking the question presents an opportunity to immortalize an establishment that, despite any misgivings you may feel today, has cemented its place in Chicago’s gastronomic history. It offers a chance to engage with a living, breathing piece of the city’s hospitality heritage and see just what standard—two decades on—has been set.

Boka opened its doors in October of 2003, then representing the culmination of Boehm and Katz’s budding—but undeniably successful—careers in hospitality. The former man had opened two restaurants in Florida, one in Springfield (his hometown), and another in Nashville by the age of 30. The latter, originally from Vancouver, moved to Chicago to be an options trader but fell into helping out at his roommate’s bar and would go on to open four of his own by the time he also hit that three-decade mark. By 2001, both felt ready to take the next step into more serious restaurant ownership, and Boehm and Katz were introduced to each other by friends that same year. That “15-minute cup of coffee” turned into a “four-hour discussion” and kicked off a “year and a half of location scouting” that led to the development of Boka.

Being “afraid of the downtown rents,” Boehm and Katz settled on 1729 N Halsted—formerly home to Mexican restaurant Don Juan (and, before that, Blue Mesa)—near the Steppenwolf Theatre in Lincoln Park. Boka was characterized as “a departure from the neighborhood joints popping up” in the area back then. Boehm would even characterize it as a “hip counterpart” to the aforementioned theatre at the time. However, looking back on the occasion of the restaurant’s 15th birthday, the founders would reveal a greater degree of intention: “the plan was to open a non-stuffy, contemporary American concept that fit somewhere between the city’s white tablecloth spots, like Charlie Trotter’s” and “the countless lower-end, casual haunts.” Put another way, there was a “whole lot of ultra fine dining” and a “whole lot of ultra casual” with little in between.

More specifically, Boka was consciously inspired by Danny Meyer’s Gramercy Tavern, a restaurant that had opened in 1994 and, in 2003, whose kitchen was still being run by co-founder and chef Tom Colicchio. The “contemporary American” concept was (and is) known for its dual dining spaces (a front tavern room and a more formal dining room) serving à la carte items and seasonal tasting menus featuring “the best products of the market, masterfully prepared in creative combinations” (as Michelin would write in 2005). Gramercy Tavern was ranked the “#1 Most Popular Restaurant” as part of Zagat’s NYC survey in 2003 (and would hold the first or second spot every single year through 2016). It had earned the Best Chef: New York City award (in 2000) and Outstanding Wine Service award (in 2002) from the James Beard Foundation. And the restaurant would go on to win the Outstanding Restaurant, Best Chef: New York City (for Colicchio’s replacement), and Outstanding Chef awards in the future along with holding a Michelin star in every edition of the NYC Guide since its launch in 2005. In short, Boehm and Katz could hardly have picked a better model from which to build their own legendary establishment.

But the owners had “zero chef relationships in Chicago” and, thus, “put an ad in the Chicago Reader.” Giuseppe Scurato, who had worked as a sous chef for Wolfgang Puck in San Francisco before opening Spago Chicago (as chef de cuisine) and joining Michael Kornick’s mk, made the cut along with pastry chef Leticia Zenteno. His food, at the time of Boka’s opening, was labelled “ambitious but tastefully restrained” with items like “grilled bobwhite quail with braised greens, applewood-smoked bacon and black mission figs,” “lobster risotto,” and “a double-cut pork chop with rosemary-cider reduction and blue cheese potato gratin” appearing on the menu. Also of note was a “Battle of the Sexes” wine list featuring “60-plus bottles” sorted by style “with two options per category-—one by a male and one by a female winemaker.” A “scorecard” kept “a running tally” of which producers were chosen, with the men leading with “54 percent of bottles and glasses sold” when the restaurant was featured by the Tribune in November of 2003.

Scurato’s tenure at Boka would last a little more than three-and-a-half years, a period that saw notable dishes like:

- “Japanese yellow tail crudo, radish salad, cucumbers, shiso, and soy-mustard”

- “Corn crusted maine scallops, chanterelle mushrooms, baby leeks, popcorn, lavender cream”

- “Pan seared hudson valley foie gras with duck confit, parsnip puree, pistachios, bing cherries, apricots, and a [sic] Armagnac-plum sauce”

- “Arborio rice risotto with roasted corn, oven dried tomatoes, shrimp, basil”

- “Potato gnocchi with duck confit, carmelized [sic] onions, sage, brown butter and pecorino cheese”

- “Homemade fettuccine, with morel mushrooms, english peas, sage butter, parmigiano-reggiano broth”

- “Pan roasted frog legs with herb butter, gribiche [sic] sauce and microgreen salad”

- “Rare-seared yellowfin tuna, daikon tamari ponzu, baby bok choy, soy beans, tempura vegetables”

- “Roasted monkfish ‘ossobuco,’ caramelized cohlrabi [sic], baby carrots, brussel sprouts, potatoes, bagna-cauda”

- “One half grilled maine lobster, warmed black trumpet mushroom, corn and frisee salad, neuski [sic] bacon vinaigrette”

- “Grilled calves liver, crispy neuski [sic] bacon, fried onions, 12 year aged balsamic, and parsley oil”

- “Maple syrup cabernet braised pork shank, swiss chard, glazed baby carrots and pattypan squash, garlic chips”

- “Pan roasted maple leaf duck breast, wild mushroom ragout with black truffles and espresso, brandy sauce”

- “Braised short ribs, red wine orange daube, celery root puree, salad of watercress, radish, and orange segments”

- “Hardwood grilled ribeye, potato-salsify gratin, slow roasted dutch shallots, black trumpet mushrooms, pink peppercorn sauce”

appear on the menu, along with wines from producers like Bryant Family, Chartogne-Taillet, Claude Dugat, Guigal, Hanzell, J.J. Prüm, Ken Wright, Kistler, Krug, Comte Lafon, Leflaive, Mongeard-Mugneret, Patricia Green, Pol Roger, Etienne Sauzet, Selbach-Oster, Laurent Tribut, and Quilceda Creek.

After “six month[s] of negotiations,” Boka’s “pivotal moment”—as described by Boehm and Katz—arrived in March of 2007. The restaurant succeeded in luring Giuseppe Tentori, who had spent a decade at Charlie Trotter’s and risen to the position of chef de cuisine, over to be its executive chef. He was joined by Elizabeth Dahl (formerly of Naha and Trotter’s) as pastry chef.

In August of 2007, Tentori’s “simple” and “dazzling” “Mediterranean-influenced, contemporary American cuisine” earned a three-star review (“excellent”) from Phil Vettel at the Chicago Tribune. Therein, the chef was noted for making “menu changes every two weeks or so” (though certain favorites remain “permanent fixture[s]”). In April of 2008, national media would come calling when Food & Wine—back in those glory days of print—named Tentori one of 10 “Best New Chefs in America.” The editors would praise his “innovative menu revolving around seasonal ingredients” and “eclectic, multi-layered dishes.”

For their part, Boehm and Katz would admit that Tentori’s “standard was…so much higher than anyone…[they] had ever worked with before, and he had an expectation level for everyone.” The new chef forced the owners to “continually elevated” their “game” just to keep up, which—along with the Food & Wine accolade—“legitimize[d]” the restaurant. Tentori notably introduced the “six or eight course” tasting menu to Boka in 2008 and marked a transition from “classic American food to progressive American food” in stylistic terms. That would see him named a semifinalist for the James Beard Foundation’s “Best Chef: Great Lakes” award in 2008, 2009, 2010, and 2013.

More importantly, when Michelin released its first Chicago guide in 2010, Boka would earn a star. Bibendum termed the restaurant a “pretention-free oasis” focused on “contemporary American cuisine showing Mediterranean influences, and dusted with an emphasis on ingredient sourcing.” It would also praise “avant-garde culinary choices,” “sensational twists,” and a degree of “composition and presentation” that equal the “exquisite dishes.” Boka has held this Michelin star every year since.

Tentori’s tenure would last through the end of 2013, upon which he would embark on his own projects with BRG: the aptly named GT Fish & Oyster and, later, GT Prime Steakhouse. Notable dishes during the chef’s time at Boka included:

- “Marinated big eye tuna, grapefruit, wilted mizuna, pickled onion and caper”

- “Stuffed squid, baby spinach, spicy pineapple, black tapioca”

- “Ash baked eggplant, white polenta, leek, laura chenel goat cheese”

- “Poached hen egg, salsa verde, fried masa cakes, black bean chip, housemade queso fresco, jicama-nopales salad”

- “Seared sonoma valley foie gras, grilled banana, brioche duet, toasted pine nuts, baking spice gastrique”

- “Grilled hamachi with broccoflower, kalamata olive, pickled garlic and shrimp dumpling”

- “Grilled baby octopus, eel terrine, potato & horseradish salad, candied bacon, arugula puree”

- “Maine diver scallop, korean short ribs, forbidden black rice, cumin dusted lotus root, roasted zucchini puree”

- “Barramundi, green tea soba noodles, tofu beignet, hijiki, pomelo, saffron & shellfish froth”

- “Short rib agnolotti, poached lobster, confit kohlrabi, black garlic, five spice oil, broccoli sauce, soy vinegar”

- “Chili dusted sweetbread, collard greens, okra, chicharrons, poached egg, ham broth”

- “Crispy chicken thigh, apple & chestnut risotto, pickled turnip, wild mushroom sauce”

- “Coriander crusted pheasant breast with parsley yukon gold whipped potatoes, cipollini onion and brussel sprout leaves”

- “Braised veal cheek, crispy sweetbreads, moroccan ratatouille, creamy grits, collard green puree”

- “Rabbit leg roulade, roasted rabbit loin, stinging nettle, pancetta, bee pollen gnocchi, onion chamomile sauce”

- “Sweet & spicy pork belly, steamed bao, white trumpet royale, asian slaw, fermented black beans, scallion puree”

- “Beef tenderloin, yorkshire pudding, boudin noir, salsify, savoy cabbage, cipollini onions”

- “Muscovy duck breast, foie gras raviolo, braised red cabbage, pickled duck tongue, caramelized cauliflower sauce”

- “Bison strip loin, stinging nettle soubise, bee pollen spaetzle, artichoke, pickled wild spring garlic”

Along with wines from producers like Aubert, Beaucastel, Bollinger, Georg Breuer, Robert Chevillon, Pierre-Yves Colin-Morey, Dagueneau, Dalla Valle, Vincent Dancer, Dönnhoff, David Duband, Dujac, Egly-Ouriet, Benoit Ente, Gaja, Henri Giraud, Anne Gros, Haut-Brion, Hundred Acre, Kongsgaard, Nicolas Joly, Keller, Benjamin Leroux, Latour, Leroy, Littorai, Lokoya, La Mission Haut-Brion, Markus Molitor, Peter Michael, Opus One, Palmer, Domaine du Pegau, Pierre Peters, Philipponnat, Puffeney, Quintarelli, Rayas, Mouton Rothschild, Ridge, Salon, Screaming Eagle, Shafer, Sine Qua Non, Tempier, Vacheron, G.D. Vajra, Vega Sicilia, Vietti, Williams Selyem, and Wyncroft.

In November of 2013, on the occasion of Boka’s 10th anniversary, Boehm and Katz announced a “pretty dramatic” change to the restaurant’s “look and food.” Tentori was set to leave and would be replaced by Lee Wolen, whose experience included one year as sous chef of Moto, an eight-month stage at elBulli, three years as sous chef of Eleven Madison Park, and two years as chef de cuisine of The Lobby at The Peninsula Chicago. In that latter role, he helped earn the restaurant a Michelin star in Bibendum’s 2014 Guide (the only in the concept’s history). Wolen would be joined by pastry chef Genie Kwon (herself an EMP alumna) and would be replacing the previous tasting menus with “approachable, clean flavors” solely “in an appetizer-salad-entree format.”

Seemingly, BRG did not like that its flagship had become a “special occasion restaurant,” and the new chef did not want to “tell people how to eat.” Rather, they wanted it to feel like more of a “anytime you have time spot” that would enable the team’s “sincere desire to see everyone more often.” Boka would be remodeled at the end of 2013 to ensure a “symmetry” between Wolen’s new take on the menu “and the feel of the restaurant.” The concept would reopen in February of 2014 with the perspective that it was a “brand-new restaurant” but would look to maintain the same “integrity.”

Speaking of the progression from Scurato to Tentori to Wolen, Boehm and Katz would explain that the “tie that binds [the chefs] is American cooking.” They would even, in 2018, go so far as to claim that “Wolen might be the most technically sound chef in all of Chicago.” Just as Tentori “legitimized” Boka via the recognition he earned upon taking over, his successor has amassed an even more impressive trophy cabinet through the present day.

Beyond maintaining that Michelin star each and every year, Wolen was immediately crowned “Chef of the Year” for 2014 by the Chicago Tribune, which noted that “his menus tend to be low on exotic ingredients,” but his “execution is unfailingly stunning.” Boka, likewise, would be named “Restaurant of the Year” at the Jean Banchet Awards on the back of its reopening. Nationally, Wolen would be nominated for the James Beard Foundation’s “Best Chef: Great Lakes” award in 2016, 2017, 2018, 2019, and 2020. Meg Galus, who would replace Genie Kwon in 2015, would be nominated for “Outstanding Pastry Chef” in 2016, 2017, 2018, and 2019. Boka itself would be named a semifinalist for “Outstanding Service” in 2017, would be nominated for the same award in 2018, and would be named a semifinalist for “Outstanding Restaurant” in 2020. Finally, who can forget Boehm and Katz’s nominations for “Outstanding Restaurateur[s]” from 2015-2019, which—while not exclusively attributable to mothership Boka—certainly drew on the concept’s success as their lynchpin.

Wolen’s tenure, which included stewarding the restaurant through the pandemic and persists to this day, has seen the following notable dishes appear on his menu:

- “Marinated Hamachi (yuzu kosho, plum, almonds, fennel)”

- “Bay Scallop Crudo (cauliflower, almond, citrus)”

- “Shima Aji (tomato, lemon verbena, buckwheat, radish)”

- “Cured Foie Gras Salad (peach, hazelnut, baby lettuce, buttermilk)”

- “Marinated Spring Artichokes (burnt sunflower, endive, quince vinegar)”

- “Heirloom Tomatoes (watermelon, sunflower seeds, lemon balm)”

- “Marinated Prawns (sheep’s milk yogurt, smoked dates, hazelnuts, horseradish)”

- “Broccoli Agnolotti (goat gouda, lemon, black truffle)”

- “Kabocha Agnolotti (chanterelle, toasted yeast, smoked scallop)”

- “Salt Cod Ravioli (fava beans, artichokes, arugula, lemon)”

- “Ricotta Gnudi (arugula, hazelnuts, morcilla)”

- “Ricotta Dumplings (broccoli, goat gouda, fried garlic)”

- “Tajarin (black truffle, parmesan)”

- “Roasted Veal Sweetbreads (grilled bitter greens, peach, turnip)”

- “Charcoal Grilled Beets (buckwheat, sheep’s milk yogurt, licorice)”

- “Pekin Duck Breast (fennel, peaches, sheep’s milk feta)”

- “Rabbit Loin & Sausage (confit leg, pickled ramps, apricot, pistachios)”

- “Wild Striped Bass (french white asparagus, razor clams, green garlic)”

- “Grilled Maine Lobster (matsutake, potato, seaweed)”

- “Roasted Pork Loin (crispy belly, spring onion, sorrel, sour cherry)”

- “Roasted St Canut Porcelet & Crispy Belly (nectarine, sunchoke, gem lettuce, chanterelles)”

- “Grilled Beef Short Rib (baby gem lettuce, hen of the woods, corned tongue)”

- “Juniper Rubbed Venison Loin (blood sausage, smoked chewy beets, grilled cabbage)”

- “Whole Roasted Dry Aged Duck for two (foie gras sausage, spring onion, rhubarb)”

Along with wines from producers like Allemand, Antica Terra, Araujo, Comte Armand, Ar.Pe.Pe., Bérêche, Simon Bize, Bonneau du Martray, Cédric Bouchard, Chave, Bruno Clair, Clape, Domaine du Collier, Ulysse Collin, Corison, Cotat, Domaine de la Côte, Diamond Creek, Evening Land, Fichet, Fourrier, Thierry Germain, Giacosa, Guiberteau, Jamet, Emmerich Knoll, Koehler-Ruprecht, Lafarge, Laroche, Peter Lauer, Georges Laval, Marguet, Méo-Camuzet, Le Moine, De Moor, Denis Mortet, Mugneret-Gibourg, Nanclares, Jérôme Prévost, Radikon, Rhys, Domaine de la Romanée-Conti , Rouget, Roulot, Roumier, Sandhi, Savart, Trump Winery, and de Vogüé (among many of the other producers already listed).

It is worth noting that Boka’s tasting menu returned around the midpoint of 2015 and has, as it was in Tentori’s time, remained a fixture ever since. Unfortunately, the details of these meals are not preserved in the same manner as the à la carte offerings (even if there is typically some degree of overlap between the two). Nonetheless, the mere fact that these tastings returned signals how the new “anytime you have time” identity—launched in 2014—has had to ultimately reconcile itself with the restaurant’s preexisting “special occasion” status. Boka has a Michelin star after all, and many Chicagoans have come to expect some form of set menu—a turnkey gastronomic experience that precludes making the “wrong choice”—when visiting establishments of that status. In truth, the overall approachability of the concept (with its traditional à la carte options) may better encourage skeptical diners to wholly trust the chef (relative to more imposing restaurants at the two- or three-star level whose menus are entirely shrouded in mystery).

To that point, looking back over 20 years and three different chefs (from an admittedly blurry, rather removed standpoint), Scurato and Wolen seem to have more in common with each other than either has with Tentori. The latter, flexing his Charlie Trotter’s credentials, crafted menus filled with eclectic flourishes: “brioche duet,” “baking spice gastrique,” “eel terrine,” “green tea soba noodles,” “tofu beignet,” “shellfish froth,” “steamed bao,” “yorkshire pudding,” “stinging nettle soubise.” Meanwhile, the former two—reflecting more of a straightlaced Spago- and EMP-derived contemporary American influence—created dishes that spoke of a simpler, ingredient-driven vision: “lavender cream,” “bacon vinaigrette,” “parsley oil,” “parsnip puree,” “quince vinegar,” “grilled bitter greens,” “pickled ramps,” “smoked chewy beets,” “corned tongue.”

It should be considered that changes in the naming conventions for Boka’s dishes between eras may account for Scurato and (especially) Wolen’s food seeming less complex. However, it also seems clear that Tentori was brought in to elevate the cuisine in line with what was the most influential restaurant of its era. Doing so, he won a Michelin star and laid the groundwork for Wolen to maintain that standard while taking inspiration from his own experience at what was subsequently one of the most influential restaurants of its own era (EMP). Sacrificing some of Charlie Trotter’s penchant for French and Japanese technique meant gravitating back toward a style that matched Boka’s original inspiration: Gramercy Tavern. The same goes for omitting (temporarily) any tasting menu: something that is, indeed, offered at Gramercy Tavern but not compulsory as it would be at Charlie Trotter’s or EMP.

That being said, across some 20 visits to Eleven Madison Park in the period directly following Wolen’s departure from the restaurant (a period that saw the restaurant christened “The World’s Best Restaurant” by William Reed’s self-important jury), you never felt particularly impressed by the food. Yes, it was made with finesse and beautifully presented but never struck you with the same hedonistic power as Brooklyn Fare or the same paradigm-shifting approach to ingredient sourcing as Blue Hill at Stone Barns. Rather, EMP’s food was broadly pleasing and memorably presented without ever pursuing extremes of flavor or texture. In short, it was aesthetically refined but fairly safe cooking that was buoyed by an absolutely top-class hospitality and beverage program (port tongs and all) that made for a singular experience. These latter factors, you think, really worked to secure the restaurant its accolades, for boundary-breaking cuisine is often too polarizing to please the lowest common denominator. Instead, Daniel Humm developed a style of cookery that everyone could enjoy at a basic gustatory level while empowering the front-of-house team to weave their magic tableside. However, stripped of its service-based bells and whistles, EMP’s food was not all that different from the NoMad or Davies and Brook: Michelin-starred concepts with fussy, restrained seasonal fare that did little to stir the soul. Given the touting of Wolen’s time working under Humm, it may be worth probing just how valuable that influence—beyond all the glitz—really is.

Today, Wolen remains at the helm of Boka and has just, in fact, celebrated his tenth anniversary there (with the late June date revealing just how far in advance Boehm and Katz brought him on ahead of the 2014 renovation). The executive chef, though he has partnered with BRG on other projects over the years, is almost synonymous with the group’s crown jewel restaurant at this point. Such longevity can cut both ways in terms of motivation, but post-pandemic staff shuffles have kept things interesting: namely, Meg Galus’s departure and replacement by Kim Mok as pastry chef.

Boka at 20, Wolen at 10, and BRG (with Levy) going national—could the stakes be higher? Or is it lower? For no small snapshot can adequately reflect a dining institution’s ultimate legacy, but it may help to reveal how Chicago’s dining scene (and, perhaps, you yourself) has changed over two decades.

You have visited Boka as long as you have been dining in Chicago but, for the purposes of this review, will focus on a series of three visits (on different days of the week and comprising different party sizes) conducted throughout June of 2023. This timeframe, while abbreviated, will help to track the menu’s current degree of dynamism (remember Tentori saying he makes changes “every two weeks or so”) and the staff’s response to serial patronage. It also allows, as far as dishes that you have tasted multiple times, for a more precise evaluation of consistency: a particularly salient metric for a restaurant of this age and stature.

With that said, let us begin.

From the outside, 1729 N Halsted, that old Don Juan and Blue Mesa space, has not changed all that much over the past couple decades. Yes, the front patio’s blue brick accents are long gone, along with the matching blue “Boka Restaurant + Bar” text on the streetside awning. In their place, you find black brick, columns, window frames, railings, and light fixtures that match the building’s worn cornice while working to contrast the faded reddish-brownish brick wrapping around the rest of the structure. Taken in from afar, the restaurant’s exterior fits perfectly with the designs of its closest neighbors. The entrance, as always, is marked by overflowing greenery, but the Michelin-starred concept remains inconspicuous. Its name appears over the front door, which is set—across that aforementioned patio—a good ways back from the sidewalk. Otherwise, guests may only spy a shining metal planter with the Boka logo (a later addition) closer to the curb. Even later, a crossed fork and key symbol (one of the restaurant’s newer motifs) was added atop the text—perhaps to help assure passersby that there is, indeed, an eatery back there.

Yes, as BRG pursues ever-larger and more glamorous openings in boutique hotels and bowling alleys, its mothership remains beautifully understated: all the better to fit in on a block that lacks the same concentration of competition as the group’s River North and West Loop properties. Alinea remains two doors down as a particularly illustrious neighbor (its own edifice being as inscrutable as ever). Likewise, a longstanding trio of casual Italian concepts—Trattoria Gianni, Vinci, and Pizza Capri—help to absorb the Steppenwolf crowds.

Otherwise, with Charlie Trotter’s (once located about a block to the north) and L2O long gone, the neighborhood is a rather dire place to eat. To the west, you find a sprawling retail park that—however convenient its various wares—houses chains like Burrito Beach, Buffalo Wild Wings, Chipotle, Epic Burger, Roti, Subway, sweetgreen, Taco Bell Cantina, and Uncle Julio’s (along with, if you dare, a second location of Fatso’s Last Stand). To the north, the options are a bit better, with LEYE concepts like Summer House, Ramen-san, and Café Ba-Ba-Reeba! leading the charge alongside Blue Door Farm Stand and Mediterranean spots like Cedar Palace, MEDI, and Athenian Room. Further afield, you may find notable spots like Armitage Alehouse, Bocadillo Market, Esmé, Evette’s, and even Galit interspersed with classics like Geja’s, Pat’s, Pequod’s, Wiener’s Circle, and the like. But Boka, undoubtedly, is one of few gastronomic options in a neighborhood where the other Michelin-starred options tend to misfire.

With Alinea being the sort of place to laugh would-be walk-ins out the door, Boka positively bosses its respective block and monopolizes its premium theatre dining. Plus, being at the very south end of Lincoln Park, the restaurant also does not feel quite so far from all the dining options immediately surrounding Downtown Chicago and flowing up into the Gold Coast. Its venue, 20 years on, is highly accessible without having fallen victim to any surrounding overdevelopment. Thus, the concept need not shout its presence on the block but remains pleasantly subdued, serene, and a bit cloistered. You cannot even really look through the building’s blackened windows, and the restaurant’s front door, even if it is left open to welcome guests in from time to time, is far enough way to preclude any view into the dining room. This ensures that entering Boka, even if it lacks the shock and awe of Alinea, Ever, or Oriole, retains some sense of that romantic, transporting effect. It suggests, as you make your way across that singular patio, that this grande dame of Chicago dining still holds some secrets and may very well deliver something special.

Passing through the restaurant’s front door, you immediately encounter the host stand. Chances are, one of the two or three women that are always posted there has been waiting, watching, and perfectly anticipating your arrival. Their greeting is immediate and cheery as you finally enter range and lock eyes. The youngest of the hostesses still looks to be in high school. Opposite her more experienced counterparts, she lends the welcome a trace of earnestness that catches you somewhat off guard. This is not a sleek, suited, serious Michelin-starred concept that contrives to make you doubt that you really belong. Rather, Boka’s staff is disarming from the very first moment of interaction. They instill the sense that this is a warm, family-friendly environment that just happens to craft superlative food. Effortlessly, they put you at ease and prepare the ground for your server to maintain the same mood upon reaching the table.

20 years on, when a restaurant may easily operate as if it’s seen and done it all, the charm of such an exemplary welcome cannot be understated. So many of Chicago’s finest restaurants (especially those that merely purport themselves to be) exhibit a palpable degree of tension when first encountering guests. Perhaps the staff has studied their notes a bit too much or, otherwise, is simply driven too hard by their managers. But this overwhelming degree of anticipation leads to interactions that seem stiff, overly rehearsed, and—yes—uncanny. For some, all this fuss feels like luxury. However, in an experience economy that increasingly prizes authenticity, it increasingly comes across as hollow.

Boka sets the tone of being a “neighborhood restaurant” brilliantly, and the restaurant is clearly rewarded for doing so. You do see some of the usual tourists and transient star-chasers throughout the dining room. But what strikes you more is the older couple, complete with a foldable walker, that you see helped into their seats. Or, perhaps, it is the family whose young daughters feel comfortable enough (and are allowed, for better or worse) to dine here in jean shorts and flip-fops. You must also mention the young father trying to foist an oversized stroller—strewn with every manner of bag and bauble—through the door.

Such moments may raise eyebrows at other establishments, but Boka responds with perfect deference. The restaurant accepts these parties as they are rather than asking them to fit the mold of what “fine dining” demands. In doing so, it has truly endeared itself to the community and come to transcend what that Michelin star signals from the outside. Better yet, once a first-timer has been brought into the fold (and assuming they do not get perturbed by things like a lack of dress code), the restaurant opens its arms as if you are a regular. Boka is the delightfully refined but never stuffy space that all ages—necessitating any kind of accommodation—can enjoy. This mood might not be the right fit for every expression of gastronomy, yet, here, it harkens back to a kind of Disneyfied hospitality that you find rather nice. Much of that is reflected, too, in the restaurant’s interior design.

Boka’s original aesthetic was crafted by New York-based Bogdanow Partners, whose founder Larry Bogdanow had notably designed Danny Meyer’s Union Square Café to be “easy, comfortable and timeless” as if “no architect had ever been there.” His work for Boehm and Katz included “interesting elements” (in the restaurant’s own words) like “a cell phone booth, a stainless steel water trough that illuminates the entrance wall, fabric sculptures in the main dining room, and striking colors that range from marigold to cranberry.” That sounds—and, based on a surviving image, looks—like a lot, but these warm, vivid tones must have seemed quite fashionable in the early aughts. Plus, they (and the rest of the listed novelties) clearly did not stop Bibendum from awarding the concept a star in 2010.

Nonetheless, Tentori’s reign would see Boka receive its first facelift around the start of 2012. These changes were described as “fairly minor,” having taken place “while the restaurant was still open,” but led to a result that was “much more modern and sexy.” Specifically, the color scheme lost much of its vividness and transitioned to “various shades of silver and gray, with accents of white and cream.” Likewise, “leopard print patterned” chairs were reupholstered with “white snake skin” and “regal purple” banquettes were redone with a “cream, gray and green pattern.” An “intimate lounge area,” too, was added across from the bar. Few photos of this particular period, which ended up being rather short, survive. However, this was the version of Boka that you first visited, and, while the “fabric sculptures” still strike you as a bit strange, the dining room felt understated, contemporary, and refined without being stifling.

Concurrent with Wolen’s acceptance of the executive chef job, Boka would close at the end of 2013 and unveil a more elaborate redesign in February of 2014. These changes, which persist to this day, were billed as part of the restaurant’s 10th anniversary “refresh” and included a conceptual pivot away from Tentori’s tasting menus (at least temporarily) toward the “anytime you have time spot” that could “see everyone more often.” On paper, features like “dark woods, black leather, a living wall, and antique artwork” formed “a stark contrast to the light color scheme and airy linens” that characterized the 2012 aesthetic. However, words alone fail to capture the sense of whimsy that permeates the space. It is one that really does connect to—and maybe even enhances—the tenor and tone of hospitality that is set from the first moment of interaction.

The interior, composed by Chicago-based Simeone Deary Design Group, catches your eye from the moment you enter. Just behind the host stand, the entire wall (including a hidden door) is rendered in bronze- and silver-toned strips of antique door hardware. This element seems to reference the crossed fork and key symbol Boka uses on its menus and the signage outside, but it also evokes a burnished, timeworn quality that signals the restaurant has been here a while and is comfortable embracing some sense of “history.”

That being said, the rest of the space is in no way musty. The patinaed hardware is immediately contrasted by bright, ikat-patterned concrete tile that lends the entrance more of an eclectic, bohemian feel. Making your way toward the table, you enter hallway with black, finely speckled wallpaper and an antique-looking portrait of Bill Murray in old-timely military regalia. A kindred piece, located across from the bar, depicts Dave Grohl in a similar manner (and Wolen himself, on the occasion of the chef’s 10-year anniversary with the restaurant, was gifted his own resemblance in the same style). With these details, the feeling that you might be in a preserved, plastic-on-the-furniture “timeless” setting fades and something more nuanced takes hold. The paintings of Murray and Grohl (no doubt unexpected and hilarious in early 2014) are the sort you now see hawked via Instagram ads, but they still signal how Boka embraces a particular kind of vintage identity. It is one that is a good bit playful, one that connects to contemporary (if a bit older) pop culture icons, and one that—in doing so—forms a timeless expression of a very particular moment in time.

Making your way out of the hallway, you find yourself between the bar and the main dining room. The former, to your left, is defined by a dark brown counter with sleek, matching stools that seat up to 12. Behind the bar, two hanging rows of shelving glisten with coveted bottles while another three rows, arranged stepwise, line the base. On the opposite wall, you find two so-called “high-top” tables that actually each comprise a raised banquette that seats up to three. Combining the energy of the bar with an unmatched level of seclusion, this particular area stands as one of the great hidden gems of Chicago fine dining.

Moving past the bar to the end of the room, the grided wooden flooring (itself pleasantly worn) transitions to black and white hexagonal tiles that are scattered seemingly at random. This space, which abuts the windows looking out onto Halsted, is its own little haven. It contains two sets of two four-top banquettes that are set snugly beneath wooden arches that frame the building’s original brick walls. Sconces replicating human hands—two closed fists clutching candles and one open palm holding a jar—are affixed to each surface. A circular five-top, illuminated by a trio of beaded chandeliers, sits in the very middle of the floor. Finally, a pair of two-tops sit directly against the windows. This area makes up Boka’s lounge, which—while reserved for walk-ins—is so nicely appointed and intimate that you would hardly feel you are missing out by not being in the dining room proper.

Turning back toward the bar, you pass an alcove that leads to a staircase that leads down to the bathrooms. This area, no doubt, is where the building shows some of its age. However, some striking black-and-white wallpaper—rendered in a pattern of squares and concentric perpendicular lines—and matching black tile lend the space a refreshing Art Deco feel. These particular elements seem to be new additions that appeared some time after the major 2014 renovation, for the stairwell back then matched the rest of the restaurant’s design but still seemed rather plain. The visual effect goes a long way, especially paired with a couple plush armchairs, to make the subterranean space feel more like an extension of the luxury seen upstairs. Reaching the bottom, you may take a moment to appreciate the ungodly number of James Beard Award certificates and Michelin star plaques that line the walls. Otherwise, the lavatories themselves feel a bit humid and cramped. You even had trouble getting one toilet seat to stay in place. But these are small nitpicks that just about escape attention when the rest of the experience is going swimmingly.

Returning upstairs, you pass the bar and continue on through the dividers that frame the dining room. A service station, equipped with drawers, ice buckets, trays, all manner of wine bottles, and one or two flourishes of greenery, forms the focal point of the space. Above it, a grid of antique molding (quite possibly original to the building) attracts your eye. Its texture accentuates the subtle grided pattern of the wooden flooring and the ribbed wooden beams that stretch down from the ceiling and form arches along one of the walls. As in the lounge, these arches house a series of banquettes that each seat up to six guests spread across detachable two- and four-tops. Opposite them, you find rounded booths (corresponding somewhat to those “high-top” tables) that can also seat a half dozen guests in more snug, intimate confines. A couple more of them line the back wall while the remainder of the floor space is made up of a few standing four-tops.

The wallpaper, leather seating, and tabletops throughout this dining room are all done in dark brown. Most of the chairs, too, feature dark wooden accents that surround off-white cushions. However, those located in the middle of the floor possess white wooden frames with darker colored cushions. This accentuates the white marble of the service station, the white wallpaper (and crystalline light fixtures) set in the arches between the banquettes, and the white frames surrounding the doors that lead into the adjacent dining space.

It is easy to say that, without those “fabric sculptures” and “marigold” tones of yesteryear, Boka’s dining room seems more serious and conventional than ever. The restaurant has certainly abandoned the more contemporary design that characterized the space for close to a decade. However, invoking something of a plain or subdued feeling in this principal room feels smart, for it asserts that—despite the zany tilling and artwork that distinguishes other rooms—there lies at the core of the concept a trusty, understated eating house. Ultimately, this dining room does not try to be much more than a warm, convivial space with plenty of room between parties and careful attunement to the practice of good service. In that respect, it does feel timeless, and it works—importantly—to ground some of the bolder aesthetic choices (seen elsewhere) that do run the risk of feeling dated.

Nowhere does that question come more to the fore than in the secondary dining room that is located just beyond Boka’s host stand (visible through a set of double doors) but primarily accessed by walking through the main dining room and accessing a separate entrance. While comprising a fully closed structure, you think of this space as something of a greenhouse design given the largely windowed ceiling and sizable rear doors that lead out onto the restaurant’s back patio. The design scheme here more closely matches Boka’s entrance than the other dining room, featuring the same ikat-patterned concrete tile and a fanciful “living wall.” The portraits interspersed across the surface of that latter element are not of celebrities but of various animals—different species of birds and big cats—anthropomorphized in their own military regalia. Other details of note include the same beaded chandeliers seen in the lounge, the same booths seen in the main dining room, and a range of plush leather armchairs (also used in the lounge). The building’s original brick wall is also incorporated into the design—onto which is scrawled the (misattributed) Oscar Wilde quote (actually found to originate with advertising for the Menards chain of hardware stores), “Be Yourself. Everyone Else Is Already Taken.”

Finally, should you make your way out onto that back patio, you will find a small, fenced-in area that is about the size of the lounge. Still, it looks better than it sounds. A quartet of four-top tables with sturdy (yet comfortable) all-weather chairs make up the space. They are surrounded by trees, bushes, planters, and an array of hanging flowerpots with just enough outdoor lighting interspersed between them to make the entire scene grow beautifully in the twilight. This patio is so isolated and so intimately arranged that you could easily mistake it for a residential backyard, which makes for a rather intoxicating effect at this level of dining.

Overall, Boka’s ambiance is impressive at a structural level. While seeming a bit subdued from the outside, the restaurant immediately greets you with a dose of its personality upon walking through the door. The door hardware, concrete tiling, and pop culture references join with the attitude of the staff to ensure you are not at that cold, stiff kind of Michelin-starred establishment. As you make your way further inside, you find several delineated zones in which to dine: the bustling bar (with its two lovely high-tops), the front lounge (with its windows), the main dining room (with its classic, subdued mood), the “greenhouse” dining room (echoing the zaniness of the entrance), and the back patio (a garden oasis). You may even include the front patio that, while not always utilized, offers the chance to absorb some of the neighborhood’s energy from a streetside perch.

Each of these areas work well enough with each other, though there is a clear thread that connects the restaurant’s entrance, its lounge, the staircase heading to the bathrooms, and the “greenhouse” dining room. These are the accent spaces (whereas the bar, the main dining room, and both patios are more conventional). This contrast helps prevent Boka from seeming like a theme restaurant or, worse, a Bonhomme property. It empowers certain playful touches to catch your eye and feel special without adding to any larger sensory overload.

Sure, you think that the Murray and Grohl portraits, the hand-shaped sconces, the “Oscar Wilde” quote, the living wall, and its anthropomorphized animals come across as a bit tacky nearly a decade later. You think that all of these elements—save for the living wall—could be removed and that the restaurant would benefit from a greater degree of restraint. Such a change would allow simple differences in the color and texture of the various materials, as well as structural differences in the rooms themselves, to better distinguish the various spaces without such a heavy-handed resort to eye-catching baubles. However, once the sun goes down and Boka is bathed in warm lighting and the din of diners’ revelry, these colorful details become something more like Easter eggs. They are there to be discovered—not to take center stage—and cannot be faulted too harshly for seeming frozen in time. If misfiring, pretentious concepts like Alinea and Ever have taught you anything, it is that more personality is always better than less (and you don’t mean Thomas Masters or Matthew McConaughey).

Arriving at the table, you take your seat and are greeted, in short order, by the server. They welcome (and welcome back) your party before taking its water preferences and leaving you to decide on any further beverages.

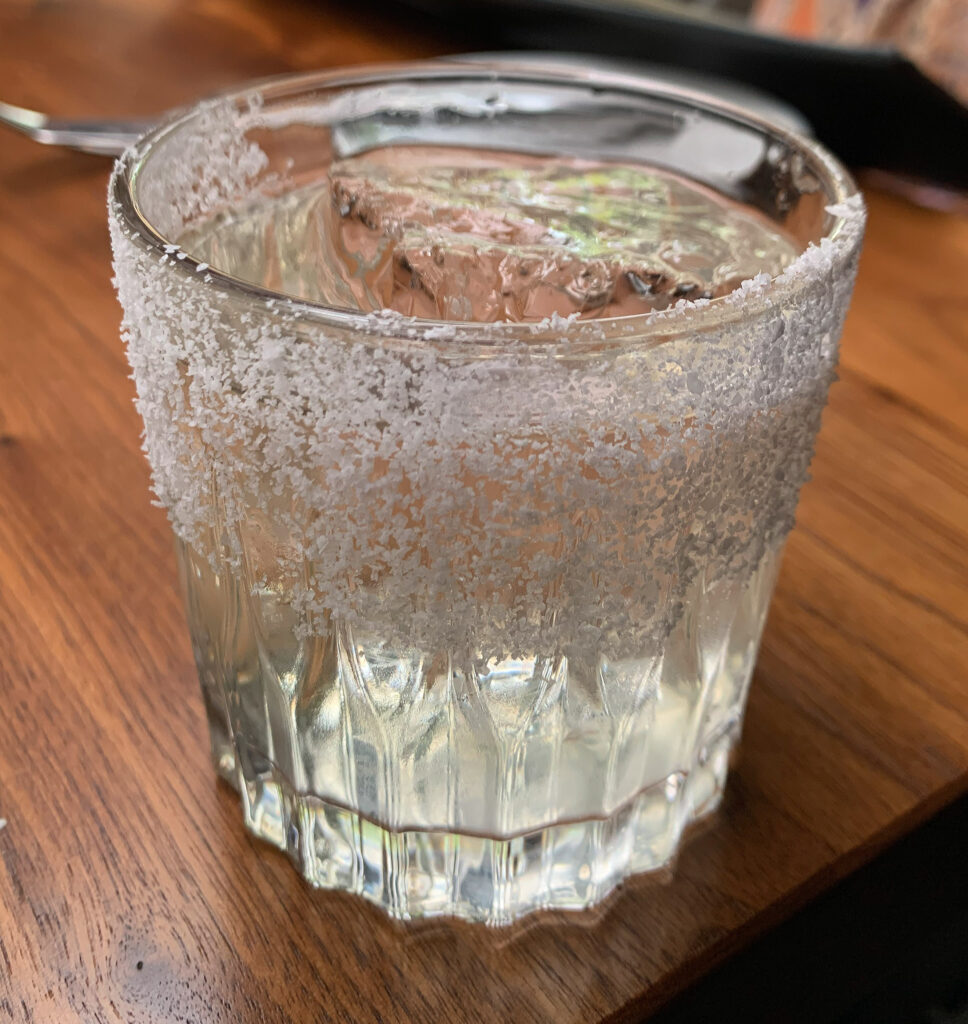

That begins with cocktails—courtesy of bar manager Anna Thorn, who started as a bartender at Boka in 2018. Her selection, at present, includes eight standard creations (priced from $18-$20) and six under the “Reserve” heading (priced from $29-$36). (There was also, in honor of the restaurant’s 20th anniversary, a “Blue Boka” offered throughout June that reimagined one of the “beloved” original drinks from the concept’s opening menu.)

Having sampled a couple of the cocktails (and several of those ordered by others in your party), you find Thorn’s work to be impressive across the board. The drinks that make up her standard selection are filled with notes of passion fruit, orange, pineapple, grapefruit, and lime that are perfect for warmer weather. Of these, the “Goodbye Butterfly” (Espolón Reposado tequila, El Güel mezcal, red miso, black cardamom) and aforementioned “Blue Boka” special have been particular impressive, offering fine degrees of depth without ever seeming boozy or detracting from an overall sense of refreshment. You would also like to add that, despite not trying them, the “A Moveable Feast” (El Dorado 3-Year rum, William Hinton rum, Thai lime, pineapple) and “Tropical Itch” (Evan Williams bourbon, Smith & Cross rum, passion fruit) strike you as highly appealing.

Moreover, at a time when “reserve” cocktails have proliferated across every kind of restaurant to encourage greater spending, Thorn’s approach to the category is laudable. The drinks only cost about 50% more than those in the standard selection (making use of premium—but not altogether rare—ingredients), and both the “Margarita” (Comisario tequila, Grand Marnier, lime) and “Negroni” (Monkey 47 gin, Cappellano Barolo Chinato, Contratto Bitter) are simply excellent. These creations are a bit more spirit-forward than those you have previously mentioned, but they still avoid any perceivable alcohol and, rather, have impressed you with their superb balance and length (though the “Margarita” could use just a bit more citrus). Of course, classic cocktails can always be mixed, on request, using more quotidian spirits. Yet these reserve options, in your experience, are well worth splurging on to get an even fuller sense of the bar manager’s talent.

Even spirit-free options like a “Smoothie King” (Lyre’s Italian Orange, passion fruit, lemon) or a range of housemade sodas (ginger, Thai lime, pineapple, grapefruit, passion fruit) strike you as going above and beyond the norm (even at a Michelin-starred caliber). You sampled the pineapple soda and found its combination of sweetness, tartness, acidity, and fizz to be far superior than the Crush or Fanta versions of the flavor (no mean feat when it comes to pure hedonism).

The remainder of the beverage program comprises beers from local breweries like Middle Brow, Pollyanna, and Big Drop joined by a couple from South Carolina (Westbrook Brewing) and Indiana (Upland Brewing Co.) and a cider from Vermont’s Shacksbury. There is also an extensive spirits list featuring estimable producers like Caol Ila, Chichibu, Elijah Craig, Michter’s, Old Fitzgerald, Springbank, Willett, and Yamazaki. Finally, you find a selection of four “After Dinner Cocktails” (the La Colombe-based “Iced Irish Coffee” and “Espresso Martini” being the most familiar) alongside a wide range of amari and a particularly special feature: Domaine Roulot’s excellent “le Citron” lemon liqueur—quite a rarity!

Overall, Thorn’s work with Boka’s beverage program is highly commendable. There is plenty to discover—technically perfect but always approachable—to such an extent that even you cannot help imbibing. That is particularly impressive given just how much there is to digest with regard to your principal love: fermented grape juice.

Wine director Thibaut Idenn is currently in charge of Boka’s program, having now been in the role for a little more than a year and, before that, working as the restaurant’s general manager for a year too. Prior to joining BRG (where he also oversees Alla Vita), he spent close to three years as beverage manager (later director) of The Langham and a year at the Sofitel Chicago. Originally from Champagne, Idenn holds an MSc in International Hospitality Management from Lyon’s EMLYON Business School (in partnership with Institut Paul Bocuse) with a specialization in International Wine and Beverage Management. He also worked, among a range of experiences in France, at the three-Michelin-star Alain Ducasse au Plaza Athénée. On paper, Idenn seems like one of the most pedigreed hospitality professionals, and, in practice, that definitely holds true.

Boka’s by-the-glass selection, during his tenure, has included wines like:

Sparkling

- La Gioiosa Prosecco di Valdobbiadene Superiore Brut ($15)

- Laurent Perrier “Cuvée Rosé” Champagne ($39)

- Etienne Calsac “L’échappée Belle” Blanc de Blancs Champagne ($30)

- 2014 Michel Gonet Blanc de Blancs Champagne Grand Cru ($35)

White

- 2022 Coralie & Damien Delecheneau “Trinqu’âmes” Sauvignon Blanc ($18)

- 2020 Malat “Ried Höhlgraben” Grüner Veltliner ($18)

- 2016 Gallica “Rorick Heritage Vineyard” Albariño ($21)

- 2021 Ferrando “La Torrazza” Erbaluce ($19)

- 2021 Ovum “Old Love” Riesling Blend ($16)

- 2021 Keller “Limestone” Riesling ($21)

- 2017 Charles Hours “Cuvée Marie” Gros Manseng ($19)

- 2020 Marielle Michot “M” Pouilly-Fumé ($18)

- 2020 Les Héritiers du Comte Lafon Mâcon-Milly-Lamartine ($22)

- 2017 Minimus “Dijon Free” Chardonnay ($25)

Rosé

- 2021 Finca Enguera “Rosado” Tempranillo ($14)

Red

- 2020 Enderle & Moll “Liaison” Pinot Noir ($22)

- 2021 Chacra “Barda” Pinot Noir ($22)

- 2021 Roagna Dolcetto d’Alba ($22)

- 2021 Jordi Raventós Clos dels Guarans “Les Someres” Grenache ($16)

- 2020 Sara Pérez i René Barbier, Dido “La Universal” Grenache ($18)

- 2019/2021 Julien Cécillon “Les Graviers” Syrah ($16)

- 2016 La Chapelle de Meyney St-Estèphe ($30)

While these bottles have not appeared on the list all at once, looking at them in sum reveals a clear pattern. First, Idenn is adept at giving his customers what they want (Champagne, Sauvignon Blanc, Chardonnay, Pinot Noir, Cabernet) while simultaneously showcasing the sort of oddballs (Grüner, Erbaluce, Gros Manseng, Dolcetto) that invite a conversation and, thus, customer education. Second, the wine director knows how to provide pure value—a $15 Prosecco, a $16 Riesling, a $14 rosé, a $16 Grenache, a $16 Syrah—while, for those willing to spend a little more, delivering producers that punch way above their weight: the Etienne Calsac, Michel Gonet, Keller, Les Héritiers du Comte Lafon, Minimus, Enderle & Moll, Chacra, and Roagna all being extraordinary choices that you would be thrilled to drink anywhere. (Even the La Chapelle de Meyney, though you are not familiar with it, looks to be about as good a young Bordeaux as you could hope to find on such a list.) Lastly, Idenn seems just as comfortable sourcing great wines from classic regions (Pouilly-Fumé, Alba, the Northern Rhône, Médoc) as he does finding counterparts from unexpected places: California Albariño, Oregon Riesling, German Pinot Noir, Catalonian Grenache.

In short, Idenn has put together what you consider to be one of the best—if not the best—by-the-glass selection in Chicago. It contains the kind of bottles that make you, as an experienced oenophile, do a double take, which means the uninitiated are in for quite a treat. By marshalling Boka’s resources in order to offer great wines at an accessible price, the wine director does a commendable job of enriching vinous appreciation in Chicago.

As a supplement to the restaurant’s “Seven Course Tasting Menu” ($165), Idenn offers two turnkey options: the “Standard Wine Pairing” ($80) and the “Reserve Wine Pairing” ($160). Of these, you have only tried the latter, which has comprised the following bottles:

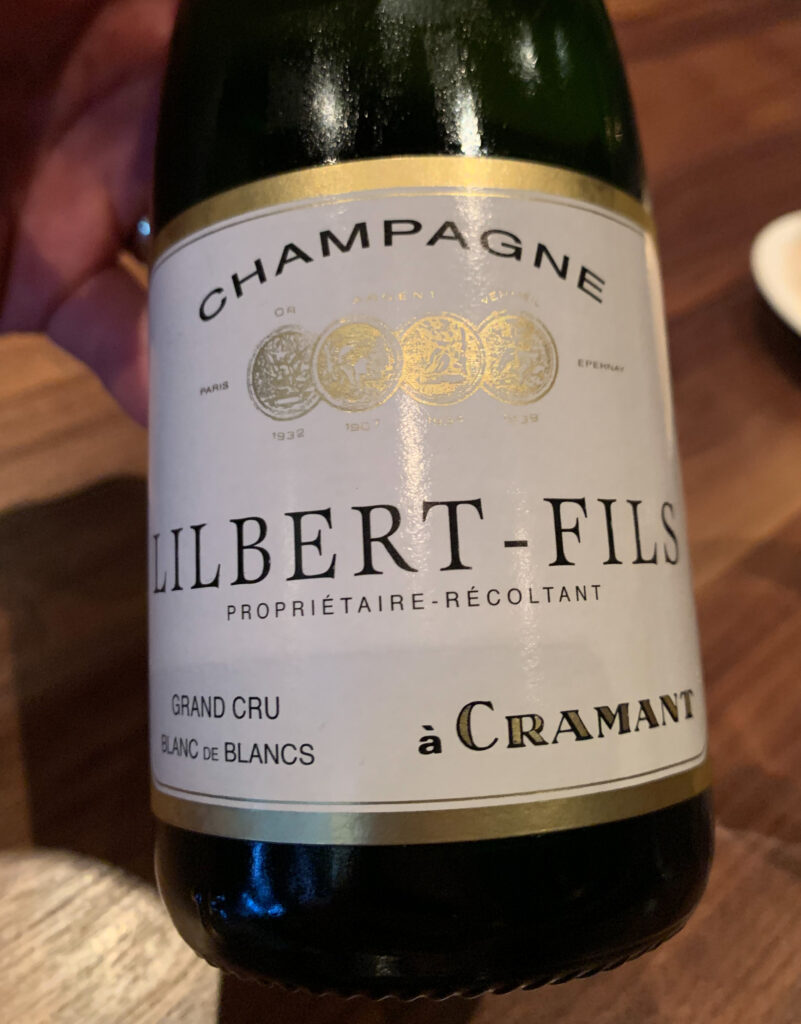

- Lilbert & Fils Blanc de Blancs Champagne Grand Cru

- 2020 Weingut Beurer “Alte Reben” Silvaner

- 2018 Henry Marionnet “Provignage” Romorantin

- 2016 Tenuta di Fiorano “Alberico Bianco” Sémillon

- 2020 Parés Baltà “Electio” Xarel-lo

- 2018 Maison Stéphan “Côteaux de Bassenon” Côte-Rôtie

- 2008 Closerie du Pelan Francs-Côtes-de-Bordeaux

- Jorge Ordoñez & Co. “Victoria N°2”

- Domaine du Mas Blanc Banyuls “Collection 1978”

First, you must praise the simplicity and affordability of these pairings. They comprise only two options that avoid using any weasel words (to entice customers into choosing a more premium option for a “once-in-a-lifetime” meal) and that roughly correspond to half or the full price of the tasting menu. These sums allow guests to draw on Idenn’s experience in an approachable manner ($80) or splurge on something a bit more special ($160) without compromising the sense that Boka is a neighborhood where wine appreciation is a bonus but by no means an expectation.

That being said, it is the substance of the “Reserve Wine Pairing” that really impresses you. $160 is around where the standard pairings at pricier fine dining restaurants land, so utilizing that sum to offer a selection that guests perceive as “premium” demands a bit of strategizing. Idenn displays a masterful understanding of the peak-end rule, as well as the tastes of mainstream consumers, when he weighs the pairing toward Champagne and red wines. The Libert & Fils Blanc de Blancs, made using grand cru fruit sourced from old vines Cramant, is served in half bottle (which helps to accelerate aging) and offers a quintessential expression of a pristine, razor-sharp Chardonnay-based sparkler. The Maison Stéphan Côte-Rôtie is made from organically grown Syrah that is fermented whole cluster and bottled without sulfur, making for an example of the burly grape that is uncommonly open and absolutely bursting with flavor at such a young age. Finally, the 2008 Closerie du Pelan is made from traditional Bordeaux varieties that are organically grown and offers an uncommon degree of age, accessibility, and value for the region (courtesy of a late-release program after the property’s purchase by Le Puy).

These are three showstopping bottles that ensure the sort of diner that is inclined to pay for the reserve pairing feels they have gotten their money’s worth. And you say that as a lover of Burgundy (and of its white wines in particular). Offering bottles of value from that coveted region has never been more difficult, and there is a good chance that Chicago diners (a population that still seems to prefer bolder reds) would not appreciate the outsize spending required to do so. Instead, Idenn smartly marshals his resources toward headlining pours that will please amateurs and snobs alike.

As for the rest of the selection, the wine director finds value—effectively padding the more expensive bottles—with obscure varieties like Silvaner, Romorantin (a completely new one for you), Sémillon, and Xarel-lo. This is sensible, for you think most white wine drinkers would be open to trying new grapes that share some of the same characteristics (acidity, oak influence) as their usual favorites while lovers of Champagne or Cabernet really want the “real thing.” Plus, these varieties once more provide Idenn and his staff with an opportunity to educate even moderately experienced drinkers with a whole host of information relating to terroir and winemaking that they may carry into future experiences. All the while, they remain broadly refreshing and, thus, easy to enjoy.

When it comes to dessert, the wine director brings forth crowd-pleasing pours of the Ordoñez & Co. “Victoria N°2” (a late harvest Muscat of Alexandria) and Banyuls “Collection 1978” (a Port-like fortified wine made with old-vine grenache). These bottles offer all the sappy sweetness one might desire at the end of the meal at a fraction of the cost one would pay for famous names like Sauternes, Trockenbeerenauslese, or Eiswein. Once more, their relative obscurity—and hedonistic appeal—invites a rewarding conversation about how these sweet wines are made.

Overall, as with Boka’s by-the-glass selection, Idenn has done an exceptional job with the “Reserve Wine Pairing.” His selection is intelligent but still totally approachable and satisfying (even for a snob) at that $160 price. It ranks as one of the best you have seen in the city and reminds you that pairings—so frequently tacked on for the hell of it—can still offer pleasant surprises even when you are so used to picking out your own wine.

That leads you, at long last, to the main event: the bottle list. You have already surveyed the countless illustrious producers that have graced Boka’s cellars over the decades and still find a lot to like. Here are some notable selections that have appeared over the past year:

Sparkling

- NV Etienne Calsac “Les Revenants” Brut Nature ($265)

- NV Roger Coulon “Heri-Hodie Brut” Premier Cru ($142)

- NV Dhondt-Grellet “Les Terre Fines” Blanc de Blancs Premier Cru Extra Brut ($252)

- NV Egly-Ouriet “Les Vignes de Bisseuil” Premier Cru ($266)

- 2011 Egly-Ouriet “Cuvée de Prestige Millésimé” Grand Cru Brut ($580)

- NV Egly-Ouriet “VP” Grand Cru Extra Brut ($376)

- NV Egly-Ouriet “Les Crayères” Blanc de Noirs Grand Cru Brut Vieilles Vignes ($625)

- NV Pierre Gerbais “Champ Viole” Blancs de Blanc Extra Brut ($205)

- NV Jacquesson “Cuvée 744” Extra-Brut ($235)

- NV Krug “Grande Cuvée 170ème Edition” ($499)

- NV George Laval “Cumière” ($240)

- NV George Laval “Cumière Rosé” ($592)

- NV Les Frères Mignon “L’Aventure” Blanc de Blancs Premier Cru Extra Brut ($198)

- 2018 Roses de Jeanne “Haute Lemblée” Blancs de Blanc Brut ($325)

- NV Frédéric Savart “L’Ouverture” ($185)

- NV Vouette & Sorbée “Fidèle” Brut Nature ($249)

- 2012 Veuve Clicquot “La Grande Dame” ($370)

White

- 2019 Arnot-Roberts “Trout Gulch Vineyard” Chardonnay ($116)

- 2020 Domaine Bernard-Bonin “La Rencontre” Meursault ($463)

- 2021 Thibaud Boudignon Anjou Blanc ($104)

- 2016 Clos Rougeard “Brézé” ($460)

- 2018 Domaine du Collier Saumur Blanc ($138)

- 2021 Pascal Cotat “La Grande Côte” ($236)

- 2021 François Cotat “La Grande Côte” ($193)

- 2021 François Cotat “Les Monts Damnés” ($193)

- 2021 François Cotat “Culs de Beaujeu” ($209)

- 2019 Benoit Ente “Antichtone” Bourgogne Aligoté ($85)

- 2019 Pierre Vincent Girardin “Eclat de Calcaire” Bourgogne Blanc ($105)

- 2020 Domaine Guiberteau “Les Moulins” ($117)

- 2018 Domaine Guiberteau “Brézé” ($200)

- 2015 Domaine Guiberteau “Brézé” ($250)

- 2021 Emrich-Schönleber “Mineral” Trocken ($100)

- 2019 Domaine Huet “Le Mont Demi Sec” ($130)

- 2019 Keller “Abts E® Westhofener Brunnenhäuschen GG” ($664)

- 2019 Keller “Dalsheimer Hubacker GG” ($774)

- 2019 Keller “G-Max” ($2000)

- 2019 Keller “Nieder-Flörsheimer Frauenberg GG” ($987)

- 2019 Keller “Niersteiner Hipping Kabinett Goldkapsel” ($987)

- 2019 Keller “Niersteiner Pettenthal Kabinett Goldkapsel” ($987)

- 2020 Keller “Von der Fels Trocken” ($136)

- 2021 Keller “Von der Fels Trocken” ($130)

- 2020 Keller “Westhofener Kirchspiel GG” ($794)

- 2019 Keller “Westhofener Morstein GG” ($774)

- 2021 Kelley Fox “Durant Vineyard Lark Block” Chardonnay ($110)

- 2018 Domaine Hubert Lamy “La Princée” Saint-Aubin ($159)

- 2017 Domaine des Comtes Lafon “Clos de la Baronne” Meursault ($479)

- 2019 Domaine Leflaive Bourgogne Blanc ($277)

- 2019 Domaine Leflaive “Clavoillon” Puligny-Montrachet Premier Cru ($655)

- 2020 Domaine Leflaive “Les Chênes” Mâcon-Verzé ($198)

- 2017 Lingua Franca “Bunker Hill” Chardonnay ($135)

- 2017 Dr. Loosen “Alte Reben Urziger Wurtzgarten Trocken GG” ($118)

- 2022 Massican Sauvignon Blanc ($102)

- 2018 Matthiasson Ribolla Gialla ($120)

- 2017 Domaine Bernard Moreau “Sur Gamay” Saint-Aubin Premier Cru ($195)

- 2021 Domaine Moreau-Naudet Chablis ($125)

- 2020 Domaine François Raveneau “Butteaux” Chablis Premier Cru ($995)

- 2021 Ronco del Gnemiz “San Zuan” Friulano ($150)

- 2018 Domaine Roulot Meursault ($555)

- 2017 François Rousset-Martin “Terres blanches” ($146)

- 2021 Sandhi Chardonnay ($68)

- 2020 Domaine de Trévallon Blanc ($310)

- 2019 Domaine Vacheron “Le Paradis” ($198)

- 2021 Vietti “Roero” Arneis ($68)

- 2020 Williams Selyem “Unoaked Chardonnay” ($186)

Red

- 2019 Thierry Allemand “Chaillot” ($685)