In your recent evaluation of Daisies “2.0,” you saw how a neighborhood pastificio—well-received in its first, relatively humble form—traversed the pandemic and transformed into a bigger, better concept attracting national acclaim. And, as you now turn toward Thattu, it is hard not to see a bit of a parallel.

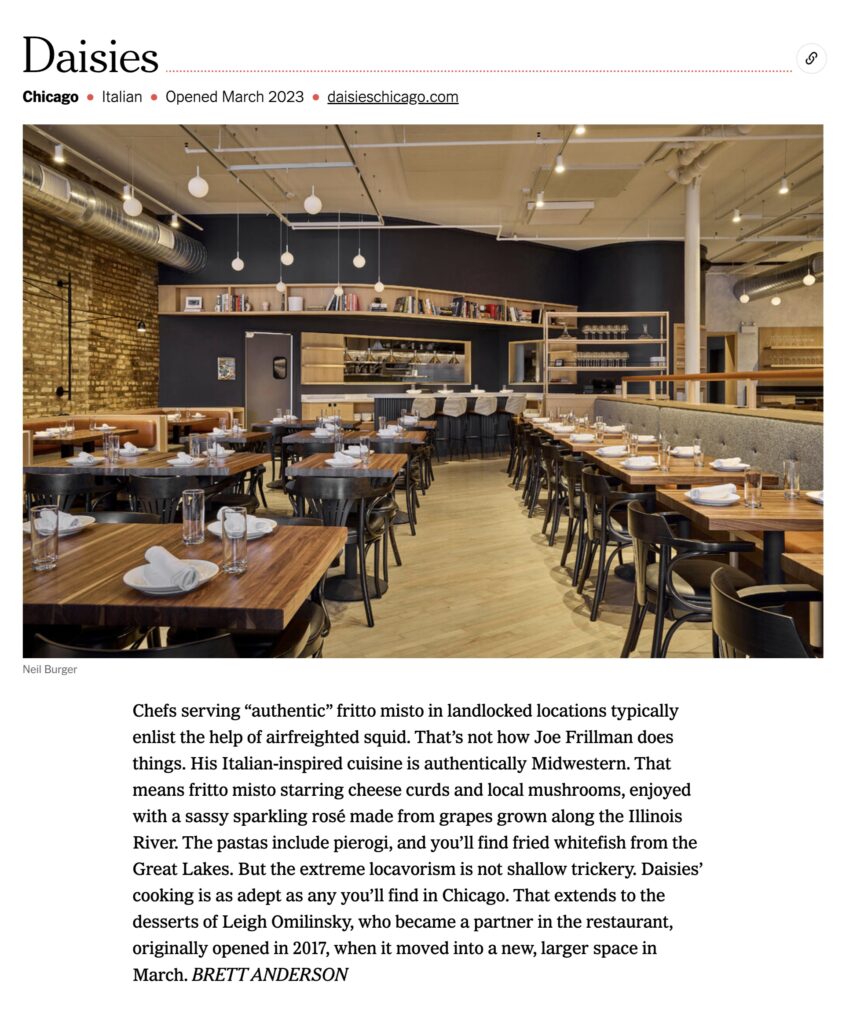

To recap: Daisies’s journey saw key aspects of its identity (e.g., an “if the Midwest was a region of Italy” ethos and ingredient sourcing from Frillman Farms) remain in place as chef-proprietor Joe Frillman brought on pastry chef-partner Leigh Omilinsky and expanded operations to include an all-day café. With a sleek, new kitchen and an expanded dining room, the restaurant began serving breakfast and lunch to a grateful neighborhood. At dinner, old favorites still reigned, but the number of starters, pastas, and desserts also increased notably. Even the cocktails (now utilizing food waste) and wine program (that came to include Italian offerings) showed clear growth.

With such objective markers of improvement to showcase, Daisies “2.0” was perfectly poised to build on the reputation of its predecessor. However, Frillman was not content to just reopen and quietly go about executing the same Midwestern-Italian cuisine on a larger scale. Yes, he had the farm-to-table philosophy to lean on, but just how brightly would the concept shine when compared to countless places serving pasta throughout the city? How would he compete with restaurants boasting even grander dining rooms, deeper wine lists, and beloved celebrity chefs at the helm?

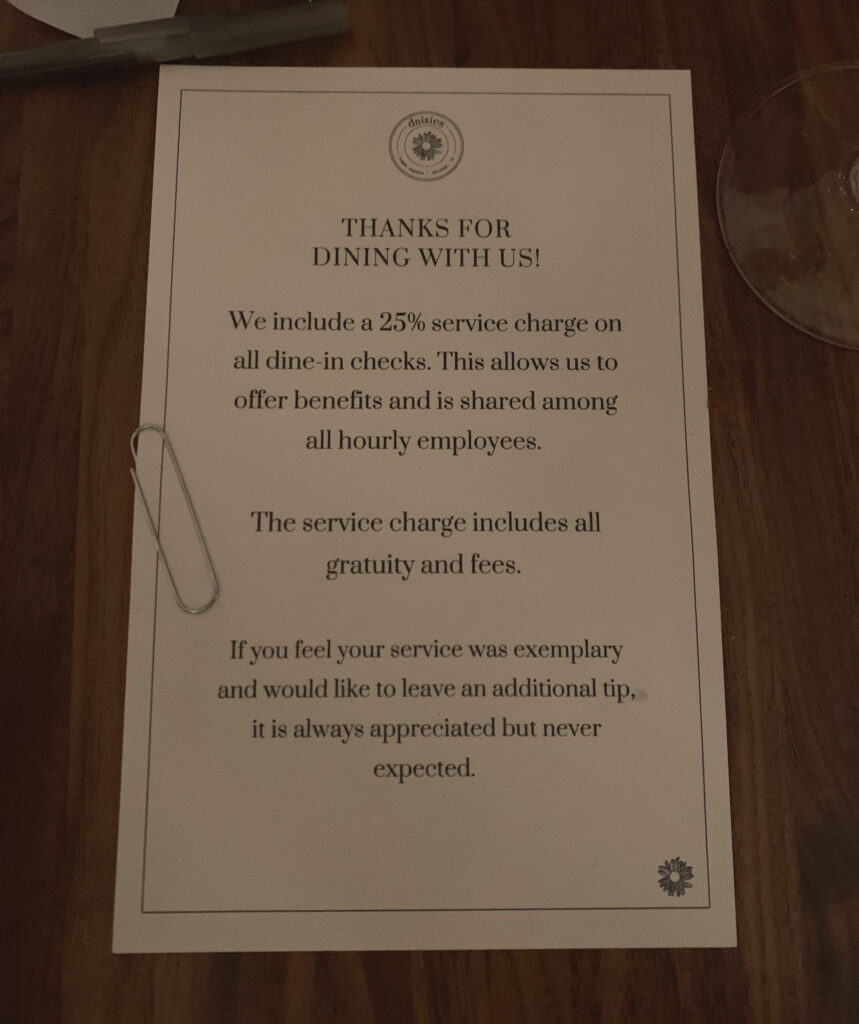

Frillman had already been assessing a 2% charge on all checks since the early days of “1.0” to help pay for employee health insurance, and, in the post-pandemic climate (one in which surcharges were de rigueur), he saw a chance to situate himself as an industry leader. Daisies “2.0” would “include a 25% service charge on all dine-in checks” in order to help “offer benefits” and whose proceeds would also be “shared among all hourly employees.” Though the tip line remained, providing any additional gratuity was “always appreciated but never expected.”

Chicagoans had grown accustomed to the smaller (3%-3.25%) surcharges adopted by groups like Hogsalt and Lettuce Entertain You “in lieu of increased menu prices” to “offset rising costs associated with the restaurant (food, beverage, labor, benefits, supplies).” Many had also, no doubt, encountered the 20% service charges assessed by some of the city’s Michelin-starred properties (ones that sometimes played coy about precluding the need to also tip). But Daisies was bigger (in amplitude) and bolder (given the casual nature of the concept) in how it went about securing its extra sum.

Frillman took everything that “2.0” had going for it—fresh setting, expanded service, new menu—and confidently sprinkled the 25% on top. This premium proved controversial among some diners (and continues to be despite painstaking work to prime customers for the pain) but transformed the restaurant into a cause célèbre. “Critics” took for granted that Daisies “2.0” did everything better than its predecessor and focused, instead, on carrying water for the concept’s unique approach to labor compensation. These journalists, seeing in activism a pathway toward increased relevance, defended the 25% even more wholeheartedly than they endorsed the food. The writers made their case to the public—not all that convincingly—to help normalize a practice they personally approved of. And, a few months later, national publications provided the rubber stamp: tacitly supporting their local peers while cherry-picking a couple fashionable dishes to feature.

You could, perhaps, just chalk this all up to a bit of marketing genius on Frillman’s part. When you already have the goodwill of the neighborhood on your side, why not recruit them for a “giant experiment”? (Surely, the 25% service charge made devoted customers feel like bold “activists” in their own right while soothing them with that most insidious salve: the feeling of conscientious consumption.) Likewise, when there’s a narrative that the press seems desperate to sell, why not deliver it to them on a platter? That’s just good business—the kind of killer instinct that turns a simple reopening into a powerful, newsworthy statement.

It is hard to take much issue with a “good” restaurant that uses the black magic of public relations to appear “great.” Yet, in Daisies, you discovered a malfunctioning—and at times hazardous—restaurant that draws on its media narrative in order to deceive.

From the vantage point of the local or even national “critic”—limited by time and money and only capable of making one visit—Daisies “2.0” looks quite good: a handsome community space serving clever farm-to-table fare (e.g., the artichoke and cheese curd “Fritto Misto”) and desserts from an eminent pastry chef with a delectable social justice angle to boot. It’s the sort of restaurant that Chicago journalists, seeking the approval of their more prominent peers, desperately wish the backwards public would support. Likewise, the concept allows those national publications—forever dismissive of the Midwest—to paint the region as a bit less regressive than their readers suspect: “look, even the hillbillies eat their vegetables and help pay for employee healthcare.”

However, from your vantage point—coldly evaluating Daisies across four visits with no incentive, no partiality other than to judge the concept against its peers—the restaurant revolted you. First, the 25% service charge yielded service that was warm at best and often totally overwhelmed, inattentive, and listless at its worst. The kitchen, too, habitually struggled with pacing, meaning that the extra premium paid to the staff could not be justified by the quality of experience offered. In truth, these concerns can be waved away as the product of bitter subjectivity. Thus, the real damning evidence came from the food. The Frillman Farms produce, much touted, displayed no particular advantage over conventional ingredients. The pastas (only two of 11 you could recommend) were frequently stuck together and drowned in flavorless liquid you hesitate to call sauce. Seafood options included deviously mislabeled, 10-week-expired caviar, sandy mussels, and sulfurous prawns. In sum, only a third of the menu—at best—passed muster, and the kitchen clearly revealed it has a dire problem when it comes to consistency and hygiene.

With this in mind, Frillman’s marketing genius started to seem more like a cover for his mismanagement and overall lack of aptitude (considering how many of the chef’s longstanding recipes failed to impress). The restaurant, by your measure, had been so anointed at the time of reopening that it started to believe its own hype and never properly grew into the expanded space. Months after the highs of positive coverage wore off, with business still swelling, the staff was floundering while Frillman and his managers did little more than wipe down tables.

Daisies’s success, brokered by media figures who went once and saw only what they wanted to see, represented a victory of hyperreality (the restaurant as a symbol of intangible, untastable values) over substance. It formed a blueprint for how you can win national acclaim without really putting in the work and marked—though you hope it does not—Chicago’s further estrangement from the careful appreciation of craft.

Again, you do not retread this ground meaninglessly. Rather, you bring up Daisies because you see, in it, some relation to what you know about Thattu. The latter restaurant started in a humble food hall with a fairly novel, easily communicable focus on the regional cuisine of Kerala. It won early acclaim with its work before the pandemic forced the team to take up a nomadic existence. Through pop-ups, they kept the concept alive and came out the other end with plans for a brick-and-mortar restaurant. This bigger, better location empowered greater creative expression. It also saw Thattu relaunch with a no-tipping model and land, just a few months ago, alongside Daisies as Chicago’s only other representative on The New York Times’s list of “50 places in the United States that we’re most excited about right now.”

Now, this similar narrative—modest beginnings, a story of growth, an embrace of social change, and resulting national attention—does not predispose you toward disliking Thattu. The concept, at core, is more heartfelt and more intimately conceived than Daisies. It represents an attempt to bring something new to Chicago while Frillman, in contrast, nefariously contrived a way to make his lackluster pastas and nepotistic produce seem more appealing within a crowded genre.

Yes, Thattu’s story must be taken on its own merits while preserving just a wee bit of suspicion for a blueprint you have seen succeed before. Surely, for those who seek to guide the unwashed masses toward a better tomorrow, fostering the appreciation of underrepresented regional cuisine—alongside the promotion of a progressive labor compensation model—proves just as tempting a topic as the farm-to-table/25% service charge model. Have these “critics,” in their haste to socially engineer the public, failed yet again to do their due diligence?

More importantly, does Thattu—despite benefitting from the novelty of its food and support for its practices—impress those who are not predisposed to care about either? Does it excel in those fundamental dimensions of setting, service, beverage, and food? Is it great because it is merely different—or because it really pushes hospitality, texture, balance of flavors, and consistency to another level? These are the questions you must always ask: the questions that strip away the advantages of trendiness and allow for a valid assessment of where a restaurant ranks in the wider dining scene. Dedication to craft is, after all, the real equalizer and the only means through which novel ideas rightfully win acceptance.

Before evaluating where Thattu stands today, it may be instructive to uncover how it got there.

The story starts with Vinod Kalathil, who moved to the United States from Kerala in 1996. He missed the cuisine of his homeland, located on India’s tropical Malabar Coast (and known for its “coconut-lined sandy beaches”), and “asked his mother to send recipes for the dishes he craved.” They “never had any proportions, just a little bit of this and a little bit of that,” but Kalathil slowly honed his skills while working as “a consultant who traveled the world designing warehouses.”

Margaret Pak, meanwhile, grew up in Santa Maria, “a small agricultural town in California,” across the street from a cow pasture with farms cultivating fresh strawberries and broccoli further down the way. Her parents immigrated to the United States from Korea—her father escaping from the North and her mother leaving a small town in the South—and met in Texas through an arranged marriage. When the former graduated medical school, the family moved to Los Angeles (where two of Pak’s three older sisters were born) before settling in Santa Maria.

Of childhood, Pak recalls her mother’s “excellent Korean cooking” (including “strange, weird kimchis” made from local ingredients like broccoli remnants) but also notes the influence of native delicacies like the city’s famous barbecue tri-tip. Though originally attending college in San Diego and studying mathematics, she returned closer to home and discovered, in statistics, a field that better spoke to her preference for working with “concrete things.” Living in a transfer dorm, Pak describes going to school when she did and where she did—developing lasting friendships with students from Vietnam, India, and Iran—as a “big factor” in her later career.

After college, Pak moved to Salinas (near Monterrey) and took a job as a risk analyst with the intention of putting her time into the corporate world before one day becoming a teacher and staying in California all the while. The job, nonetheless, brought her to the company’s headquarters in Chicago and inspired some wider consideration of where she might like to work. During one of those trips, Pak “felt it in her bones” that she had to go to a Tori Amos concert—her 40th as a fan—in Las Vegas. Since a friend had dropped out, it ended up being the first time she ever traveled by herself and went to a performance by herself. There, “on the floor of a Las Vegas dance club” in 2003, she first met Kalathil, and the two decided to pursue a long-distance relationship for what amounted to 13 months.

During that period, Kalathil was living in Connecticut and Pak was trying to facilitate a permanent move to Chicago. Still, she would trek across the country to visit, and he would prepare Keralite recipes like crab curry for them. Looking back, Pak described it as “such a simple, beautiful, comforting dish” and admitted she thinks she “fell in love with Vinod and Keralite food around the same time.”

Having both relocated to Chicago, Kalathil and Pak married in 2005. The ceremony was conducted in Kerala, and the bride “was in awe” at her “first time experience a sadhya, or Indian wedding feast.” Plus, “Vinod’s mom would cook every day,” and Pak would enjoy eating items like “fish molee,” “fluffy idli served with coconut chutney,” “payasam (rice pudding),” and “the masala biscuits Kalathil’s father offered with afternoon tea.” (The latter recipe—a “sweet, savory, and spicy cookie”—came from the 79-year-old Delecta Bakery and is made with “nearly two-dozen ingredients.” In 2010, Pak would be granted their “industrial-scale recipe.”)

Back at home, Pak stayed in the finance world for a couple of years and “tried everything,” traveling and learning a lot, but ultimately felt it “wasn’t working.” She worked for a credit bureau downtown for a couple more years before taking an analytics job with a Japanese pharmaceutical company in the north suburbs. Pak loved the company but not the three-hour commute each day and continued looking for closer opportunities. That led her to an “up-and-coming,” “for much younger kids” (she was then in her late 30s) firm and, eventually, a “devasting” layoff.

This experience, according to Pak, formed a “big turning point.” Kalathil offered his support and urged her to take some time to figure out what she really wanted to do. Pak took a retail job at Ann Taylor LOFT, which she “loved doing,” while pondering her next move. The idea of “doing something with food” came to mind. She characterized herself as “an expert eater” but “never really cooked at home” save for a few Punjabi recipes and some Keralan cuisine gleaned from Kalathil. Thus, Pak ventured into food sales for a year and sold ketchups for a small boutique firm. Eventually, the company shifted to offering a michelada mix, and she began to meet “more interesting chefs.”

Pak was struck at seeing how Korean cuisine was being reinterpreted in the city, and the desire to “get into the kitchen” finally hit her. Drawn to culinary school, she polled the chefs she was working with and opted to pursue “real world experience” instead. Pak made a long list of restaurants she either “really liked” or just “wanted to go stage at” and found herself immediately conscripted upon arriving at her first choice: Kimski.

Chef Won Kim—a somewhat controversial figure you might recall—revealed his sous chef had pulled out his back and asked if Pak could help peel and prep a bunch of tofu as they talked. She enjoyed the two or three hours she spent readying ingredients for the restaurant’s mushroom vegan ramen and was invited to help serve it at Ramenfest two days later. Despite being thrown into the deep end and tasked with working alongside 30 different concepts in the BellyQ space, Pak “absolutely loved” the experience. Yes, she was exhausted by the end of it but, also, heartened by the feeling of feeding so many people.

Pak planned to stage in “a couple other places” but Kim invited her to come back. It was 2017—and things were proceeding swimmingly—until she received news that her father had abruptly passed away. Pak left Kimski and returned to California for two months in order to take some time off. However, upon returning to Chicago, Kim invited her back into the kitchen and quickly assigned her a five-day work schedule. Pak describes this time in the Kimski kitchen as a “crash course” in learning how to cook Korean food and to prepare food at a restaurant-level scale.

After a year of throwing herself into the industry as a prep cook, Kim invited Pak to prepare some of the Indian food she was making at home for staff meal (like egg curry and goat biryani). The chef was enthused by the results and pushed her to do a pop-up. Pak resisted at first but ultimately felt inspired by the other emerging talents that offered limited-time menus at Kimski. When her mother passed in May of 2018, cooking Kalathil’s cuisine also offered a way to process her grief at a time when cooking Korean food “became too hard to continue.” That following summer, she finally accepted Kim’s invitation.

Pak was “so nervous” to cook her food for the public and, in the days before presales, “people just showed up.” As it happens, they “got slammed” and the first pop-up was “such a success.” She thought the event would be “one and done” but had “too much fun” and scheduled another for the fall.

One particular pop-up, a five-course dinner at Saigon Sisters, “changed everything.” It was Pak’s first time doing dinner service in any form and prompted Mary Nguyen Aregoni, one of the restaurant’s owners, to ask if she would ever want to open a restaurant in the West Loop. Feeling that the prospect was “too much” for her, Pak resisted. However, Aregoni put forth the idea of opening a stall in a food hall that was set to open in the area. Pak had “never done a tasting before” but decided to try out for a spot. Despite “secretly freaking out,” she compiled the favorite dishes from her five pop-ups (e.g., coriander chicken, goat stew, appam, fried chicken), and the food hall’s proprietors—though “confused” at first—loved what they sampled.

Pak earned a stall at Politan Row and went about setting up the business while Kalathil, “still working his perfectly well-paying job,” helped on the back end. When thinking up a name for the concept, the couple “wanted it to be approachable, comforting food, authentic” and settled on Thattu, “the Keralite word for plate.” However, three weeks before opening, Pak was beginning to feel she could not run the business by herself. Kalathil, as it happened “was at a time in his career when he had been…looking for the next thing,” and the timing was perfect for him to leave the corporate world. He and Pak “worked on making their food food-stall friendly,” like “dredging chicken with rice flour to ensure it stayed crispy for their Kerala fried chicken” and “using Instant Pots to achieve the proper fermentation required to make their appam batter rise.”

In May of 2019, Thattu opened in Politan Row, “the first food hall to officially launch in the West Loop since French Market” (and one located in the same building as McDonald’s Global Headquarters). The concept joined 12 others, including spinoffs from Bayan Ko, Cafe Tola, Fat Shallot, and Floriole alongside newcomers like Bumbu Roux and Mom’s. At the time of launch, Pak described the venue as a “perfect platform” to “introduce folks to the street food not typically found in traditional Indian restaurants.” The fare was characterized as “heavily coconut based” and using “an assortment of aromatics,” comprising “hearty Kerala curries, house-made appam, and savory masala cookies” alongside a “signature” egg curry of “boiled eggs simmered in coconut gravy, served with fermented rice flour pancakes.”

Kalathil and Pak, it should be noted, had continued to visit Kerala “once a year,” with the latter’s mother-in-law teaching her “so many recipes.” In the days before Instagram, the chef “would take a boatload of photos and videos” to make sure she was “doing it right.” Likewise, Kalathil’s mother was said to still consult “from across the world by phone when a dish seems to be missing something.”

When Thattu opened, Pak was “really surprised” at the positive response “simple” items like the egg curry generated. They had also thought the fried chicken bites would be the concept’s “biggest thing” but found, instead, that the decidedly “homestyle” coriander chicken (a refinement of the “bachelor chicken” Kalathil used to prepare) proved to be the top seller. Though customers “were baffled at first when she started selling appams,” the coconut milk-infused fermented rice flour “pancakes” (cooked only on one side) “piqued their interest” and made them wonder “how they were supposed to eat it.” Pak would instruct them that “this particular pancake had to be dipped in a curry to be eaten,” yet this curiosity and openness helped the concept expand its client base and eventually introduce “several other Kerala cuisines to the menu.”

With such a positive response, the stall was quickly “attracting some of the longest lines at Politan Row.” Unsurprisingly, the media soon came calling. In June of 2019, Mike Sula, writing for the Chicago Reader, praised “the city’s only Keralite restaurant” and dishes like a “Portuguese-influenced vegetable stew called ishtu,” a “black-chickpea kadala curry,” and an a “kimchi upma” described as “an astonishingly tasty and unexpected union of spicy fermented cabbage, fluffy steamed semolina, and crispy fried shallots” (representing Pak’s “take on kimchi fried rice”). Those masala biscuits, first served to the chef by Kalathil’s father, already seemed “cemented as her signature.” However, the appam—”pillowy, warm, slightly sweet, and flatter” than the traditional version—formed “the ideal vehicles for the curries.” Pak was making “about 70 of these per day,” and, taking “about four minutes each,” they inspired customers to wait “for up to 35 minutes” to get one at peak times.

In October, the Chicago Tribune got in on the act. In an article praising 24 of the “best” examples of Indian food in the city, the publication praised Thattu’s “pristine pancakes,” “steamed ghee rice” (“better paired to capture the sauce dishes”), and a beetroot korma offering “tender chunks of beet bathed in warm spice the color of a dusky pink sky.” In November, Thrillist would name the food stall as one of “Chicago’s Best New Restaurants of 2019” (alongside nine other concepts like Bungalow by Middle Brow, Galit, Kumiko, Jeong, and Virtue). More particularly, the piece praised Pak’s “blend of spicy aromatics, curries, and savory masala cookies the city can’t get enough of.” Finally, in December, Time Out would award Thattu with the ninth spot on its list of “the 15 best new Chicago restaurants and bars of 2019,” praising “spicy-sweet masala biscuits, rich chickpea curry, aromatic coriander chicken and lacy rice crepes that go with just about everything on the menu.”

Nonetheless, Thattu’s biggest honor came in February of 2020, when the concept was named one of 30 semifinalists for the James Beard Foundation’s “Best New Restaurant” award. Though this nomination occurred in a climate where the organization had already “promised…to field more diverse slates of candidates,” it also preceded more sweeping institutional changes that followed the cancellation of that year’s ceremony. For what it’s worth, Pak was “floored” that Thattu was listed “with all these full-fledged restaurants” and described that she and her husband were “shocked, stunned, grateful and truly humbled.” The chef-owners also revealed, at the time, “ambitions to open a stand-alone brick-and-mortar restaurant in the future.”

Following the James Beard nomination, Thattu had its “busiest day of 2020.” However, the next day, “business plummeted,” and, “by March 4, sales were even worse.” Pak “realized how serious things were in New York” (with the spread of Covid-19) and made the decision to shutter. Politan Row itself would close its doors on March 16, and, despite reopening for a few months in August, the food hall would permanently close after entering “hibernation” in October.

Though the sudden shift meant going “from an extreme high to an extreme low,” Kalathil and Pak were smart to get out of their annual contract in favor of “a nimbler approach.” The chef-owner described the volume they were doing “seven days a week” and “14-plus hours a day” as “soul sucking” even if the transition to being at home was, in its own right, “like a shock to the system.” Still, the pandemic provided the couple with “a chance to take stock” and see how much they “wanted to keep pushing.”

For the first two weeks, Pak “was a blob and basically just slept” but then “started doing a lot of yoga, a lot of meditation, and a lot of cooking as self-care.” She began posting recipes on Instagram and the restaurant’s blog to “show people what they can do at home” while also “playing around with more vegetarian options” to help utilize more produce and support their distributors. Instead of a “long-planned trip to India,” the couple was able to get away to “eat and hike their way from Seattle to Sonoma” and “think about their next steps.”

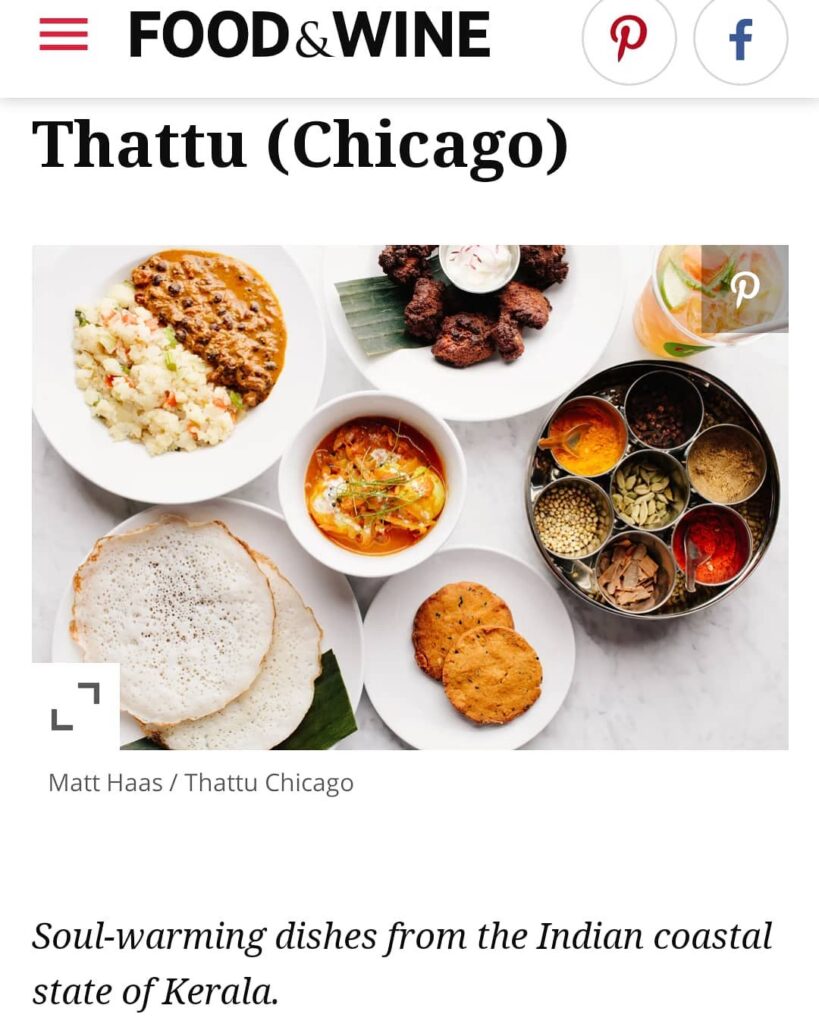

Despite being out of action, Thattu would, in June of 2020, be named one of Food & Wine’s “Best New Restaurants 2020.” The magazine, in particular, praised “juicy Keralan fried chicken,” “comforting beef curry,” and “perfectly pillowy appam” like those made by “a Keralan auntie with 40 years of cooking experience under her belt.”

To stay busy, Thattu “hosted a handful of pop-ups in Kimski” and helped prepare meals “as part of Marz Community Brewing’s Community Kitchen,” which “provides meals to those in need via food pantries, hospitals, churches, and other community organizations.” Kalathil and Pak debated “every day” about the “different, alternative formats” they might pursue “given the uncertainty facing the restaurant industry.” They knew they wanted to “continue to showcase Keralan cuisine” but didn’t “want to be in a ghost kitchen.” Thattu, to that point, was not just about showing people “that Indian food is more than just chicken tikka masala,” but “about the human interaction” even if it’s “a few minutes at a window.”

The start of 2021 would see Kalathil and Pak finally make that long-awaited trip to Kerala, spending a few months with the former’s family and engaging in R&D. By June, they were ready to get back in action via a pop-up (one that completely sold out) at Two Mile Coffee Bar. That was followed by two other limited engagements at Blind Barber and Perilla. At the end of August, the Thattu started a Kickstarter (successfully funded) for Everyday Sadya, a “cooking zine” exploring the “everyday delights of Kerala’s favorite vegetarian feast.” This would precede, in September, a proper Sadya banquet held at Guild Row, “a sprawling social club with a woodworking shop, industrial kitchen, lounge and more” located in Avondale.

September also saw Kalathil and Pak pop up at Wazwan before, in October, returning to both Guild Row (where they had secured a “one-day-a-week pickup location”) and Perilla. November would see Thattu conduct a four-night residency at Dorian’s and bring classics like appam and coriander chicken back via the Guild Row partnership. However, it would not be until January of 2022 that the team announced something more permanent.

That month, Kalathil and Pak revealed they had found a “permanent home” for Thattu in Avondale, “steps away from Metropolitan Brewing Company and social club and food incubator Guild Row.” The space, “projected for fall 2022,” would feature all the Keralan recipes Chicagoans had grown to love at Politan Row alongside the fruits of “four years of testing out recipes.” That being said, Kalathil asserted they “don’t want anything to do with ‘authentic,’” as reflected by Pak’s experimentation with dishes like “soba noodles with octopus and eel” that “uses the same coconut milk base as her fish curry.” There would also be a “full bar” and “room for a retail space,” with the couple wanting to “bring Indian pantry items,” such as banana chips, appam instant mix, and Pak’s spice mixes, “to a wider audience.” They even envisioned a possible “chai shop.”

Notably, the brick-and-mortar location would be “self-financed,” and the money Kalathil and Pak had saved meant “they could afford to be picky.” Thattu “was close to signing a lease…in Lincoln Park” but “couldn’t finalize a deal.” Other potential locations were “too small” or “didn’t feel comfy enough.” However, the couple’s partnership with Guild Row was so fruitful that its founders offered them “one of their warehouses as a permanent location.” Originally “pegged for private events,” the building didn’t have a kitchen, and the 2,900-square-foot space “was a little larger than they planned.” The area, “hidden beside the Chicago River and near car dealerships,” also didn’t “draw a lot of foot traffic.” However, Pak loved the prospect of having “a blank canvas,” and Kalathil noted they “didn’t want fine dining.” Thattu’s permanent home would not be “all reservation” but a “walk in, enjoy” kind of place.

As it happens, construction on Thattu’s permanent home would not begin until August of 2022, so Kalathil and Pak continued to busy themselves with pop-ups at The Kedzie Inn (alongside Maa Maa Dei), Guild Row, Longman & Eagle, and the 95th Street Farmers Market. The couple made their way to Kerala again in July and, in September, popped up at BiXi Beer. October saw them return to “where it all started” at Kimski.

With the dawn of 2023, some of the restaurant’s final details fell into place. Naming Kalathil and Pak among a group of 12 “rising stars…bound for big things in Chicago,” Chicago magazine revealed, in February, that Thattu would open with a “dedicated staff earning salaries, not tips” who will “run the restaurant five days a week.” In March, the concept was ready to “soon debut” with a focus that was no longer termed “South Indian street food” but, rather, “comfort food from Kerala, India’s spice garden” (particularly dishes that “remind” Kalathil “of his mother”). Her “handwritten recipes” would be on display in the space alongside the co-owner’s “own photography.”

The couple noted at the time that they wanted Thattu to be a “destination” but decided to debut solely with a “counter-service lunch menu” (to help “figure out supply and demand and proper staffing”) that included “a Kerala fried chicken sandwich, coriander chicken with appam, and veggie curry of the day.” Nonetheless, the restaurant brought on Danny Tervort, who worked at the original Politan Row stall, as chef de cuisine. He was characterized as “someone they could trust” who was “also willing to learn how to cook Indian food” as they expanded dinner offerings with items like Peralan pork chops, Alleppey duck roast, and prawns cooked with tamarind sauce. Tervort would also be joined by Cindy Knott, another veteran of the food hall, as sous chef.

Returning to the idea of being a no-tipping restaurant, Kalathil and Pak explained that they “needed to offer competitive wages and full health care benefits” to “retain and attract talent” capable of “unique skills” like “understanding Indian cooking techniques” and “how to properly sauté foods and infuse them with ghee and spices.” Rather than utilizing a service charge—and possibly prompting “consumer pushback”—they decided to go with a “transparent all-inclusive price” built into the menu itself. The couple was “nervous about how customers will react” but had faith people would pay more for individually crafted dishes.

On April 23rd, Thattu would conduct its first lunch service followed, on May 28th, by its first dinner service. Then, in August, the reviews (and features) started trickling in.

Awarding the restaurant an “8.0” in The Infatuation, Veda Kilaru praised the “laid-back atmosphere” and food “that’s near impossible to find in Chicago.” More particularly, she noted the way Kalathil “treats everyone like the nice kid who shovels their driveway” and how “seafood, coconut, and spices like turmeric and black pepper feature heavily in the best things” on the menu. Those include a “perfect amuse bouche” of fried yucca balls, a “perfect pre-dinner cocktail snack” of spicy pan-fried mussels, a “perfectly cooked, mild fish” (in a “pool of tomato and turmeric gravy”), and a bone-in pork chop with coconut braised greens and a “perfect formed yucca cake.” Perfection aside, the review admitted Thattu “can be frustratingly inconsistent” due to dishes like the mussels being too salty or the pork being overcooked. It also noted that the ordering system (via QR code) could lead to savory food appearing at the same time as dessert if you do not know any better.

Later that same month, Chicago magazine—who had named Thattu the “hottest restaurant in Chicago right now” in July—put forth “Pak’s breakdown of the perfect order at Thattu.” That included:

- “Kallumakaya”: mussels “marinated with Kashmiri chile, turmeric, and salt” then fried with onions and curry leaves that form “the sleeper hit of the menu.”

- “Chicken Ishtu and Appam”: a “lighter bite” of the beloved rice and coconut crêpe served with “chunks of potatoes, carrots, peas, and chicken” with “a touch of black pepper and cardamom.”

- “Pork Chop Peralan”: the aforementioned chop with collard greens in a “coconut and tomato base” and yucca cake.

- “Meen Pollichathu”: a “more traditional” dish of tilapia “steamed in banana leaves” with “tomato-basil gravy and turmeric-lime rice” that Pak makes “on the regular.”

- “Pazham Pori”: a dessert of plantains “deep-fried in gluten-free flour and rice flour” then served with “coconut crème anglaise, powdered sugar, and mint.”

- “Kappa Bonda”: boiled, mashed, and deep-fried yucca balls served with an onion-tamarind chutney the chef learned to make from her mother-in-law.

August would also see the Chicago Tribune have its say. Awarding Thattu three stars (“excellent”) out of four, the review termed the restaurant “a refuge for fellow nomadic souls.” More particularly, it praised the “minimalist in form, but maximalist in spice, though not numbing with heat” Kerala fried chicken sandwich, a “required side” of “ChaaterTots,” the “rice and curry of the day you’ll want every day,” and a “stunning main event” of fried catfish—all only available at lunch. For dinner, the review highlighted “irresistible lacy white crepes” of appam, a “kadala [chickpea] curry with…deeply roasted coconut gravy,” and jeera rice that was “flavorful and flawless.” Nonetheless, Kerala fried chicken bites did not “fare quite as well” as the lunchtime sandwich, a Malabar chicken biriyani “was surprisingly undersalted as a whole,” and a chicken ishtu “seemed more of broth” than stew.

Still, the service experience was labelled “impressive and gracious.” Further, Kalathil revealed in the piece that “95%” of customers are happy with the QR code ordering (something that allows for limited staff and lower prices) and that, otherwise, “he and the servers go around and talk to every table.” Additionally, “employees get a percentage of the restaurant’s income based on their weekly hours” and, despite the no-tipping format, diners “still do leave a lot of cash tips” (that were used to fund the restaurant’s three-month celebration along with other staff perks like caffeine and beer). Thattu was ultimately branded “a place of comfort and convictions” for “anyone who walks in the door.”

In early September, Lakshmi Varanasi recounted a conversation she had with Kalathil for Business Insider. The piece, titled “We opened a restaurant with a no-tipping policy. We have to charge more, but it’s been totally worth it,” revealed that the “other restaurant owners” Thattu reached out to for advice thought “customers would balk at” the higher prices entailed by their model. However, Kalathil noted that the practice was somewhat inspired by the restaurant’s experience using Square card readers during their pop-ups. Back then, upon paying, customers encountered a screen displaying suggested tip amounts, and Thattu’s owners perceived that they “seemed to feel a lot of pressure to tip” when the server was standing in front of them. Kalathil characterized these exchanges as “a little confrontational” and saw the no-tipping policy as also being a means to “avoid these interactions” and their resulting “friction.”

Otherwise, the article specifies that menu prices at Thattu are “about 15 to 20% higher” than they’d be if the added premium tacked onto the bill as a service charge. This allows the restaurant to pay the wait staff “about $19 an hour” that, factoring in the distribution of “about 8%” of all sales (“whether they’re from the restaurant, the bar, any catering we do, or our small retail section”), amounts to “between $24 or $25 an hour on average.” Labor was said to make up “more than half” of the business’s total costs, and that’s how they “planned it.” Kalathil also referenced Chicago’s proposed—and, later, successful—effort to eliminate subminimum wage for tipped workers and asserted “that’s how it should be.”

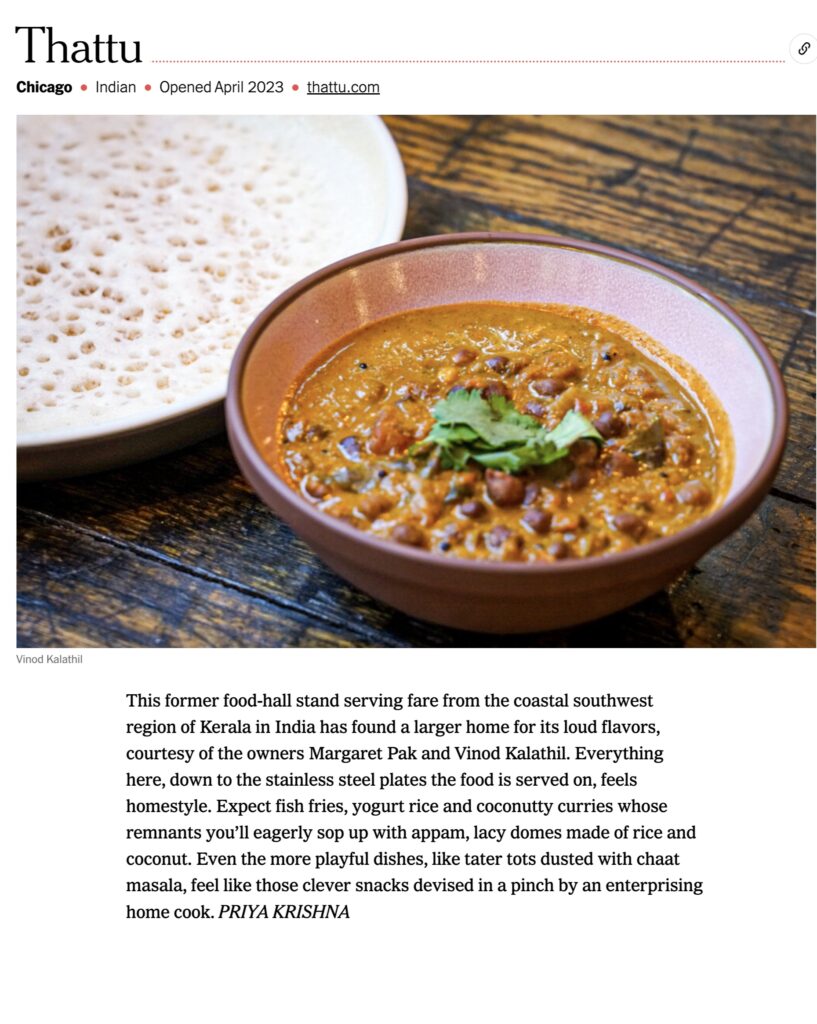

Later in September, Priya Krishna, writing for The New York Times, profiled Thattu for the publication’s list of “50 places in the United States that we’re most excited about right now” (where it and Daisies formed Chicago’s only entries). Therein, she described that “everything here, down to the stainless steel plates the food is served on, feels homestyle.” Dishes like “fish fries, yogurt rice and coconutty curries” were praised alongside those “lacy domes made of rice and coconut” called appam. Even “playful” recipes like “tater tots dusted with chaat masala” were said to “feel like those clever snacks devised in a pinch by an enterprising home cook.”

November would see Thattu awarded the 29th spot on Time Out’s list of “the 90 best restaurants in Chicago you have to try,” besting concepts like Alinea, Elske, and Ever. That month would also see Kalathil and Pak clinch another national honor. Thattu was named to Eater National’s “12 Best New Restaurants” list, with Ashok Selvam praising its “unorthodox glimpse” into the culinary traditions of Kerala (that, eschewing “authenticity,” combines “curry and coriander leaves with a Midwest meat-and-potatoes sensibility”). Equal praise is given to how the concept “tests boundaries on the business side,” with the no-tipping model being termed “an example for restaurants anxious about Chicago’s recent move to abolish the tipped minimum wage.” Still, it is said that Kalathil “doesn’t call attention to this” despite his practices, developed through consultation with “advocacy groups,” featuring in almost all of Thattu’s press coverage.

To that point, Crain’s Chicago Business also highlighted the concept’s labor compensation this past November with an article titled “Insights from a Chicago restaurant that has already ditched tipping.” Using the Chicago City Council’s elimination of the tipped minimum wage as a jumping-off point, the piece revealed “things will remain business as usual” as Thattu. In the article, Kalathil would again mention the “friction” tipping creates but, this time, as it relates to the staff: “It becomes competitive. It pits everybody against each other. It also creates bad behavior for the customer.” Instead, the co-owner tells his servers “you guys should be ready to do anything and everything” and “you don’t own a table. Just keep your eyes and ears open and make sure that people are getting what they want.” In this manner, “the service of each guest is considered a team effort,” and Thattu’s success foretells that “with the Chicago ordinance, the whole thing is going to become a more level playing ground over the next four or five years.”

Finally, the end of November would see Pak named a finalist for “Rising Chef of the Year” (alongside Trevor Fleming, Emily Kraszyk and John Lupton of Warlord; Christian Hunter of Atelier; and Damarr Brown of Virtue) at the Jean Banchet Awards. The same announcement revealed that Kyōten, Jeong, Galit and Daisies would be duking it out for the “Restaurant of the Year,” and the reference to that latter contender just about brings you full circle.

Returning to the comparison you made at the beginning of this piece, Thattu and Daisies are, undeniably, at different stages in their evolution. No doubt, Kalathil and Pak did great work at Politan Row—and that James Beard Foundation “Best New Restaurant” semifinalist nod in 2020 stands as a huge accomplishment in their given format—but the husband and wife hardly had time to cement their burgeoning reputation. The couple traced a circuitous route from staging at Kimski to pop-ups to a food hall to more pop-ups, more research, the construction of a brick-and-mortar space, and its eventual opening nearly five years after Pak first served Keralan food to the public. Thattu is the clear culmination of a half decade in the industry—as well as a couple decades of toil in the corporate world, some moments of heartbreaking loss, and still more of resilient love. It stands, today, as an anchor for all of the goodwill Kalathil and Pak have earned in Chicago, a place of permanence that can finally be rated and celebrated.

Daisies represents a more conventional tale of a chef who, working at local favorites like The Bristol and Balena, set upon opening a place of his own. With a brother growing organic produce and a snappy “if the Midwest was a region of Italy” tagline, Joe Frillman built a beloved community establishment. He navigated the pandemic with aplomb by catering to the neighborhood and positioning himself as a voice for the industry. On the other side, that led to recruitment, expansion, and the opening of a proper “2.0.” Daisies, upon relaunching, was not only bigger and better. It was now, by “experimenting” with a 25% service charge, boldly leading the nation. Frillman had not only grown the concept but seized the moment. Food and service floundered, yet the restaurant fit the bill for what the public shouldbe—must be—supporting irrespective of quality. Daisies was amply rewarded for symbolizing “the future” and providing “critics” with enough easy fodder (e.g., the “Onion Dip,” the “Fritto Misto”) to get the unwashed masses through the door.

Keeping these two stories in mind, Thattu must—despite its lengthy history as a pop-up—be judged somewhat charitably. Kalathil and Pak have only just opened their first restaurant and instituted practices, from the ground up, to more fairly compensate labor. To do so, they consulted with “advocacy groups” and embraced the part of posterchild for the no-tipping movement. Despite the claim that Kalathil “doesn’t call attention to this,” he explains the workings of the model to the press just as often as Pak describes her love of Keralan cuisine. It forms a key part of the restaurant’s identity, one that the co-owner happily exploits. However, the no-tipping idea feels authentic to the concept, is handled with restraint, and fits a narrative of corporate career changers disrupting an industry. It stands distinct from what Frillman did as a means of generating attention for his existing concept: tacking on a 25% service charge with a tip line and all sorts of disclaimers. Thattu, in contrast, is not courting controversy even if it knows how to tickle the media. Thus, the no-tipping policy need not be viewed as cynically as the Daisies service charge even if the two businesses seem to be using a similar playbook.

Likewise, at a conceptual level, you found the Daisies “if the Midwest was a region of Italy” ethos and corresponding partnership with Frillman Farms to be clever. It provided a means through which the restaurant could make pasta seem new, exciting, and something of a conscientious splurge. In short, it was just more chum for the media to latch onto and promote “1.0” and “2.0” alike without seriously evaluating the quality of the food. In practice, you found that the Frillman Farms produce was nothing special and that the pasta itself often stuck together or was otherwise poorly sauced.

In Thattu and its focus on Keralan cuisine, you find another story—due to sheer novelty—that the press is prepared to fawn over. Dishes from underrepresented regions find a readymade audience with a demographic of diners that is naturally drawn to what they haven’t tried before. Other customers may need to be prodded, and critics love nothing more than lording newfound “expertise” regarding this ingredient or that technique over their readers. Doing so helps to secure their positions as tastemakers: resources to subscribe to and use as models to appear more cultured. However, these critics—whether pursuing a personal vision of “equity” or simply thinking in practical terms—are ultimately incentivized to promote the most esoteric concepts. Hyperbolically praising an unfamiliar cuisine increases the reader’s. reliance on the tastemaker by placing the former on rocky footing. Doing so, it then makes the consumer feel smart simply for appreciating something new (whether or not it is actually good). It transforms surface-level diversity into the king of all gustatory virtues while more longstanding, native culinary traditions are characterized as boring or subject to increased scrutiny.

You, as a rule, do not award any extra points for novelty. Food must impress in accordance with fundamentals of balance and a good-faith, reflexive attempt to understand each cuisine on its own terms. However, you must admit you appreciate that Kalathil and Pak are not positioning themselves as purveyors of an “authentic” experience diners must prostrate themselves before (and that the press always seems happy to glorify). As it happens, the couple rejects “authenticity” altogether and, instead, makes clear just how personal Thattu’s cuisine is. You find, in this idea of a wife cooking the food she fell in love with through the lens of her own experience, something heartening. It is that core concept of an individual’s singular artistic expression—the food only they can cook based on the life only they have lived—that totally transcends labels. It promotes, insofar as every chef can uncover that part of themself, the only kind of equity that matters: that of each artist as a wholly unique entity.

This is all to say, Thattu benefits from some natural and strategic advantages that remind you of what Daisies contrived; however, they are not deployed nearly as deviously here. Rather, Kalathil and Pak operate their restaurant with a degree of innocence (understandable given their status as newcomers) that you find appealing. They, more than Frillman, have walked a path that anticipates how the industry might develop. And, for that reason, Thattu presents another good opportunity to evaluate what is gained and what is lost by such changes.

You have visited Thattu a total of three times for dinner, comprising a period from late November to late December of this year. As usual, you will condense the sum of your experiences into one cohesive narrative.

With that said, let us begin.

Setting out, as you always do, from somewhere near Wolf Point (home to Chicago’s first eating houses after all), it is rare that you follow the river for so long or so closely. The North Branch takes you past the old Freedom Center (home, one day in the increasingly distant future, to the permanent Bally’s Casino), along Goose Island (with its Mars Wrigley campus), beyond the former Vienna Beef Factory Store, and through a thicket of car dealerships and big-box stores before depositing you in Avondale.

The few blocks directly south of Belmont Avenue, hugging the bends of the river, look like just another industrial corridor. Surely, you find suppliers of artificial turf, fruit-flavored beverages, and dental equipment all in close proximity. However, Thattu belongs to a small nucleus of creative endeavors—the Guild Row coworking space, The Alley rock n’ roll shop, art studios, recording studios, and a dance center—that imbues the area with greater character. There are also batting cages located just down the street from the restaurant, ones whose popularity signals the number of young families living in the surrounding brownstones.

Nonetheless, the most notable sign of life comes from Rockwell on the River, an event venue that also houses a distillery, a coffee roastery, and an outpost of Soul & Smoke. The Metropolitan Brewing tap room and patio were—until just a few months ago—nestled somewhere back there, so most of the foot traffic you now see tends to be heading to the former complex.

That takes nothing away from Thattu, whose reservations are reliably fully booked and whose half-dozen barstools are taken by walk-ins shortly after opening. You just simply do not stumble into this part of town looking for something to eat. The restaurant is, necessarily, a destination, and you need to trek quite a few blocks northwest (toward Kuma’s Corner, Honey Butter Fried Chicken, and Parachute) or southwest (toward Mi Tocaya Antojería, Lula Cafe, and Daisies) to reach any concepts you might recognize.

Still, Kalathil and Pak seem to be looking forward to the neighborhood’s continued growth, with the success of their restaurant’s lunch service affirming they have already found a welcoming home. Thattu announces itself with a neon sign perched at the corner of Rockwell and Fletcher. The restaurant’s name is rendered in alternating tones of reddish orange and orangish yellow on a black background with a bit of Malayalam script set beneath it. A matching awning (further up Fletcher) repeats the word “thattu” along with a tagline stating “Comfort Food from Kerala, India’s Spice Garden.”

Otherwise, the restaurant’s building is fairly inconspicuous: reddish brick, black window frames, and cornices made of sloping black paneling with a bit of stone. The design is meant to mimic the main Guild Row building located just across the street (and, you might remember, the organization had developed the former warehouse before relinquishing it to Thattu). And, compared to the musty, rusty structure (complete with security gate) that stood before, the location now looks infinitely more enticing. No doubt, it seems like little more than a sturdy neighborhood place, yet you appreciate details like the garage door (originally added by Guild Row) that frames the restaurant’s lounge and the window (still further up Fletcher) that provides the best, totally unobstructed view of Thattu’s kitchen.

Passing through the awning, up a step, and then through the front door, you enter the restaurant. It comprises one single, sweeping room from which only the kitchen (ensconced behind another window that doubles as a pass) is separated. Clean concrete flooring, brownish brick walls, wooden beams, and a shiny ventilation system speak to the space’s industrial heritage. The exposed bulbs hanging from the ceiling echo the same thought. The minimalistic tables and chairs—rendered in a lighter tone of wood—are carefully positioned and almost make the room feel stark. However, warm lighting helps round off the rough edges of these harsh materials and invites you to appreciate the smaller details.

Those include, from the start, a wooden beam with signage proclaiming “welcome” in the same Thattu color scheme with matching Malayalam script. There is also, affixed to that post, a smaller sign declaring the “No Tips! No Service Charges!” policy (with a smaller font cheekily admitting “can’t do anything about taxes”). Behind the host stand, you note sets of shelving lined with the restaurant’s merchandise (t-shirts, the aforementioned magazine) and six-packs of beer. In the main dining room, you encounter some rattan light fixtures and, on the back wall, a trio of paintings—rendered in tones of vibrant red, light orange, holly green, and medium blue—depicting Keralan folk instruments. Turning toward the bar, you find the six aforementioned stools set against a base of dark greenish-blue tiling. This hexagonal pattern, interspersed with ruffled and triangular inlays, forms the most alluring textural element in the space. (You also must appreciate the three power outlets and six purse hooks located under the counter to make these seats extra accommodating.) Behind the bar, you find slat wood paneling framed by shelving done in a darker tone. On one level, you find a smattering of bottles and, on the other, some assorted ornaments.

Past the bar, in the corner nearest to the kitchen, you find the lounge. Set in front of that garage door you previously mentioned, this is undoubtedly the most personal and comfortable part of the restaurant. A wide, low-seated couch and some lounge chairs sit atop a worn rug while a small table offers some reading material. Meanwhile, an irregular assortment of picture frames— displaying Kalathil’s own photography and some of his mother’s handwritten recipes—looks on. Though presumably reserved for those awaiting a table, this zone really captures the restaurant’s inspiration and its spirit.

On the wall opposite the garage door, to the left of the kitchen window, and extending to one of the walls at the rear of the dining room, you encounter murals by Won Kim. These swirling, flowing pieces—punctuated by dots and rendered in bright, psychedelic tones—speak to the chef’s profound influence on Pak’s career. They enliven Thattu’s plain white walls but scream for attention just a bit too much. Taking in the entirety of the space, you are not sure the colors really match the rest of the details. The shapes, too, seem overly abstract and estranged from the restaurant’s identity. They imbue the neighborhood place with an uneasy, disorderly edge that might make sense on paper (why not solicit the work of a chef friend?) but detracts from a feeling of cohesiveness. These murals also overshadow Kalathil and Pak’s own self-expression, which is already a bit too subtle to begin with. You would like to see more of the former’s photography—and especially more of those handwritten recipes—throughout the dining room. For, overall, you do not think the restaurant’s design is totally convincing. Rather, it is practical for a place that is looking to be accessible and more or less casual.

Returning to the front door—and your entry into Thattu—you, in truth, barely have a chance to dwell on the setting. Kalathil himself mans the host stand to your immediate right and receives you warmly. Checking your name off of his tablet, the co-owner guides you personally to the table and, upon letting your party take its seats, offers a short spiel. He asks if you have been in before and, even if only as a reminder, directs your attention to the QR code on the table. He advises you to place an order using your phone while assuring the party that a server will be by shortly to help answer any questions. He might also, for those customers returning, note any new menu items. Overall, it’s a confident and friendly performance from Kalathil that sets the evening off on the right foot, and you may later see the co-owner wiping down tables or helping tend to the bar when not welcoming other guests.

Settling in, you take a moment to scan the room. The crowd at Thattu is predominantly white, middle-aged, and well-dressed. You spy couples—some slightly younger and older ones too—and groups of four, one of which (seemingly a double date) includes an Indian woman. A fun opportunity to share one’s culture, perhaps. But you also note an Indian couple, a young family (stroller parked by the entrance), and even a table of eight 20-something girls. Seeing this community come out—one that might naturally have more familiarity with Kerala—is a good sign. Though you observed a black, middle-aged couple dining at the restaurant on one occasion, the demographic is largely reflective of these two principal groups. That’s not necessarily a bad thing, for you assume that the majority of diners are still being exposed to an entirely new cuisine.

After only a moment, one of the servers comes by with water. The front-of-house team (two servers, one busser, and one bartender) is friendly and rather fluent when it comes to explaining the food. Even the bussers—responsible for running dishes and clearing them once you’re done—can point to each of the components on the plate and describe them with ease. The interactions here feel totally canny and natural. (Though, you must admit, a lack of eye contact and an attitude that is a bit too casual at times might perturb some guests.) Even more importantly, given the manner in which the QR codes are meant to allow for less staffing, the servers are generally pretty attentive.

You recall one occasion—having placed an order for two cocktails and a bottle of wine at the same time—that a server came by to double check the selection and ensure you hadn’t left some of the items in your cart and inadvertently ordered more than desired. Receiving confirmation, she kept the wine to the side and remembered to bring it by once the first drinks were finished and before the arrival of your entrées.

On a second occasion, you found yourself waiting more than 30 minutes for a “Malabar Ginger Cooler” while your dining companion sipped on a different beverage that arrived in a more timely manner. Seeing that you were inquisitively looking toward the bar (around minute 20 of your wait), one of the servers came by to inform you that Kalathil had to change out a keg underneath the counter and provided assurance that the drink was still coming. Though not a great situation overall, you appreciated the observational skill and forthrightness shown.

That being said, on a third occasion, the entrées arrived at the table, and your party was able to finish eating without anyone stopping by to ask how things were. In fact, you actually paid the check and walked out the door prior to anyone coming by to clear plates or otherwise engage you. At that point, you received a halfhearted goodbye from the server who originally greeted you (and who was then doing something behind the bar). But this was also an occasion in which your party (of two) had three unfinished beverages (glasses of wine, a cocktail) on the table that proved unpalatable. Other restaurants might have inquired if something was wrong, but the staff continued to bring your other choices without comment. The team was, on that night, decidedly uncanny: automatons merely transporting goods rather than humans conscientiously practicing hospitality.

At its best, Thattu’s team really does work the room as if they are each responsible for every table. However, when service begins to get bogged down, you quickly realize that shared ownership is really no ownership at all. The employees’ loyalty is to the business—to getting orders out in a timely manner and keeping the money flowing—rather than getting to know (let alone caring about) you. This is echoed at the top by Kalathil himself, who—apart from the friendly greeting—did not recognize you (both of you) across three visits made in quick succession and who does not even seem open to connecting with his customers. The co-owner, again, is busying running a business and attending to more fundamental duties (like changing the keg you just mentioned). He is certainly competent at doing so. Yet, the sense of hollowness you eventually detect calls the supposed warmth of a “husband and wife” concept into question. The servers say they are there to help, but the hospitality (as it relates to emotion rather than mechanics) is reactive rather than proactive. There is no story to be told, no education to be had, no feeling of being in someone’s home, and not even any exchange of names.

To be fair, none of this may very well matter to those who just want to get their food and drinks and, otherwise, entertain themselves. For, a meal at Thattu tends to last about an hour, and that pacing fits well with this particular hospitality style. (Compare this to a two-hour meal at Daisies, where the server you pay a 25% premium for disappears for 20 or 30 minutes at a time.)

Yes, credit to Kalathil: the restaurant’s no-tipping model clearly works if you consider that the team’s job is only to facilitate consumption rather than to connect or inspire. This is a fair stylistic choice to make if the owners really want to run Thattu as an anonymous, casual place (it used to be in a food hall after all). Plus, looking at the menu—where “Bites” range from $6-$14 (average price $10.50) and “Mains” from $16-$32 (average price $22.57)—you must admit you do not feel any pinch from having a 15%-20% premium baked into the cost. Surely, this might have something to do with Thattu’s location in Avondale (and its lower overhead compared to trendy concepts located in more fashionable neighborhoods).

However, the restaurant undoubtedly proves the Tribune’s “critic” wrong. Defending Daisies “2.0,” she argued: “For all the people who say to just build it [the 25% service charge] into the price, that rarely, if ever, works. Even as a professional diner, when I see a price that’s 20% more, I have to pause for a mental calculation.” This was never a convincing argument (amounting to something like “just trust me, it doesn’t work!”) and begins to seem more and more like shameless shilling for a practice the so-called journalist personally supports.

At Thattu, consumers do not encounter prices that are perceivably “20% more.” They do not need to “pause for a mental calculation.” They are simply given an all-in appraisal of what the meal will cost (excluding tax) and can properly channel their expectations toward food and service equally. It seems far more manipulative for Daisies to list a price of $52 for “Prawns de Jonghe” (that will actually come out to $65) or $135 for spoiled “Beluga” caviar (that you will pay $168.75 for) when providing service that would hardly earn a standard 20% gratuity. Frillman’s strategy amounts to a kind of foot-in-the-door technique (since guests must agree to the 25% premium but do not necessarily factor it in when ordering) that makes Thattu’s honesty all the more appealing.

One last point when it comes to the restaurant’s hospitality, and it relates to an idea you often invoke when evaluating the emotional experience of dining. You speak of “chef presence”: quite simply, the degree to which customers are able to connect with the artisan who has very likely drawn them there to begin with. Thattu is a partnership between husband and wife; however, the latter clearly forms the concept’s creative soul. Kalathil’s home cooking inspired Pak to try her hand at Keralan cuisine while filtering it through her personal perspective. She originally planned to open the original food hall location on her own before bringing her partner in to help with the business and operations side. Years later, Kalathil has proven invaluable in creating the brick-and-mortar location, facilitating the no-tipping model, and leading service as the very first face you see. Pak, based on the glimpse you get of her through the kitchen window, is busy leading the back-of-house team and actively cooking the food. This seems like a sensible division of labor to ensure that the restaurant provides the highest quality product. Kalathil may superficially try to make guests feel welcome. However, Pak’s story is the more romantic one—the one that has really been focused on in the press—and Thattu would be enriched by the chef’s presence in the dining room (even if it is fleeting). This would do a lot to remedy the lack of personality shown by the servers. Otherwise, the food alone is left to tell her story—a more difficult, but not at all impossible, proposition.

Having been greeted by your server, you can now turn your attention to the QR menu. In your experience, it is best to place a drink order as soon as possible and then turn your attention to the “Bites” given that the kitchen generally operates more efficiently than the bar.

Thattu’s beverage options are the result of a collaboration between Diageo (the multinational distributor), consultant Alex Barbatsis, and bartender Melanie Hernandez. These include non-alcoholic creations like the “Sassy Spritz” ($7.50), a “floral and fruity version of the quintessential street drink of Kerala” made with nannari (Indian sarsaparilla), passion fruit, yuzu, and Topo Chico. Though this drink took a bit of time to arrive, you enjoyed its prickly, refreshingly clean character along with an earthy, vanillin undercurrent that is hard to put your finger on.

You also sampled the aforementioned “Malabar Ginger Cooler” ($7), which was actually created by sous chef Cindy Knott and comprises a brew made of black pepper and cardamom that is paired with ginger, mint, lime, and fresh fruit. Compared to the spritz, this is even better with a smooth, mildly sweet, and chuggable quality reminiscent of an Arnold Palmer. Finally, you tried the “Manga Inji” ($8), the most expensive of the bunch that combines Alphonso mango, a zero-proof orange and rosemary apéritif, and ginger beer. You found this, too, to be delicious with a refreshing orange soda quality complicated by the depth of tropical fruit, herb, and spice. All three of these non-alcoholic options, it should be said, arrive in tall glasses that offer a generous portion (given the high prices). They form a great counterpoint to the spice notes in Pak’s cuisine and come highly recommended.

On the cocktail side, you tried the “Sarbath” ($14), an “alcoholic version of the quintessential Kerala refresher” (the same one that inspired the “Sassy Spritz”) containing rangpur-flavored Tanqueray gin, fino sherry, lime, and nannari. To your palate, this tastes quite spirit-forward and a bit bitter on the finish. You prefer the non-alcoholic version for its straightforward refreshment. You also sampled the “Konkanita” ($14), described as a “Margarita with a Goan twist” featuring tequila, lime, and “colorful” kokam fruit (a relative of mangosteen) sourced from the Konkan coast of India. This drink, too, shows a pronounced agave character with a creamy, almost chalky mouthfeel that could use a bit more acid or “bite.”

Finally, you tried the “Monsoon” ($14), an alcoholic version of the “Manga Inji” made with Alphonso mango, mezcal, lime pickle, and lime. Much like the contrast between the “Sazzy Spritz” and the “Sarbath,” the presence of the spirit here ruins what made the non-alcoholic drink great. The mezcal flavor is far too pronounced (both the agave itself and its smokiness), and there is also a strange medicinal note that comes through on the finish and makes you retch. Overall, these cocktails are disappointing for the price and would be best avoided entirely.

Complementing the cocktails, you find a small selection of spirits like Bulleit Bourbon, Johnny Walker Black Label, and Paul John Brilliance (a single malt whisky from Goa). There is also an extensive selection of beers: three from Marz Brewing and five from Azadi Brewing, which has been described as “the only Indian brewery on tap in the American craft beer market.” The latter products incorporate ingredients like Alphonso mango, basmati rice, chai, and chicory into their blends, with the resulting flavor combinations being described in detail (e.g., “faint noble aroma meets notes of honey drizzled rice, cotton candy grape, and a hint of mixed berry”) on the menu. From Azadi, you have sampled the “Manali” ($11), an IPA inspired by the “fruit bowl of India” that, true to type, moderates the bitterness of its hop blend (Galaxy, Cashmere, and BRU-1) with an impressive ripeness. You do not typically go for this style of beer but must admit you enjoyed it.

When it comes to wine—always your principal focus—you must admit your expectations were low. Thattu only lists a trio of Californian canned wines (made by Nomadica) online: “White” (75% Chardonnay, 25% French Colombard), “Rosé” (Merlot, Gamay, Grenache), and “Red” (100% Teroldego) complete with tasting notes gleaned from the company’s website. Of these, you sampled the “White” and found it to be in a buttery, caramelized style that you do not enjoy. However, there was plenty of fruit and just enough acidity to achieve some kind of balance, so others may enjoy this option more. You also tried the “Rosé,” which proved more palatable with its rounded, “Cherry Jolly Rancher” notes. Still, you are not sure you would order it again.

Ultimately, these Nomadica cans represent a turnkey solution—and one that makes sense if the restaurant figures its own drinks and the beers from Azadi Brewing will be the standout choices—but you were pleasantly surprised to discover something more.

Scanning the QR code, you have found a selection of four wines offered by the bottle:

- 2018 Lagar de Darei “Private Selection” Branco Dão ($64)

- 2022 Mother Rock “Force Celeste” Cinsault Swartland ($60)

- 2022 Banyan Gewürztraminer Monterey County ($55)

- 2017 S.C. Pannell Tempranillo Touriga McLaren Vale ($68)

Each of these options comes paired with an extensive annotation. For example, the Gewürztraminer is described as a “light bodied white” with “refreshing acidity,” “citrus notes,” “floral [notes],” and “delicate spice profiles.” Additionally, it is characterized as “a touch off dry to complement the spice in our dishes” and as “a perfect pairing for Keralan fare.” Alternatively, the Cinsault is described as a “light bodied red” that offers “crunchy red fruits” and “green herbaceous flavors.” It is characterized as “fresh and bright” with “concrete egg aging” (instead of oak) being used “to preserve its acidity.”

While these annotations do not exactly abide by the best practices outlined in your previous piece, the digital format means Thattu does not need to worry about making the menu seem too busy. Rather, guests who select one of the four options are treated to plenty of descriptors, a bit of technical information, or even a rousing endorsement (as in the case of the Gewürztraminer).

You have tried both the Branco—a crisp, dry, and cleansing white—and the Cinsault—light, just as described, and rather smooth (despite being served at room temperature)—enjoying them both. The glasses at Thattu are stemless, but they do a fine job for the chosen wines. Likewise, chillers are provided without asking (though you made the decision to fill yours with ice).

In sum, you think the bottle selection, while short, shows a lot of character. These are not wines you see being served elsewhere, and their thoughtfulness forms a nice counterpoint to the canned varieties offered as a value/”by-the-glass” option. They also, in your experience, work well with even the spiciest examples of Pak’s cuisine, not necessarily working to reveal any added nuance but (to their credit) also not obscuring any of the flavors. When you look at pricing (being sure to remove the 20% premium from the no-tipping policy), Thattu’s markups land between 89%-227% (with an average of 146%):

- 2018 Lagar de Darei “Private Selection” Branco Dão ($64 on the list, $22.99 at local retail)

- 2022 Mother Rock “Force Celeste” Cinsault Swartland ($60 on the list, $19.99 at national retail)

- 2022 Banyan Gewürztraminer Monterey County ($55 on the list, $13.99 at national retail)

- 2017 S.C. Pannell Tempranillo Touriga McLaren Vale ($68 on the list, $29.97 at national retail)

This feels fair, and, considering the restaurant allows corkage for only $15, you do not think any oenophile can be unhappy with how the program is managed. The same goes for the beverage program overall. Though you think the cocktails can use a little work, the non-alcoholic, beer, and wine by-the-bottle options are savvily curated. They reflect a good degree of creativity while still ensuring the menu feels streamlined and accessible in line with a more casual concept.

With your beverage order settled, you now turn to the food—and, in particular, with the so-called “Bites.”

The first of these, sequentially, is titled Kappa Bonda ($6). The recipe’s name refers to fried balls of mashed tapioca roots (also known as cassava, kappa, or yuca) in the same manner that “Mysore Bonda” denotes a kindred preparation made from chickpea or rice flour (popularized in the city of Mysore). Cassava was first introduced to Kerala by Visakham Thirunal, the Maharaja of Travancore (also formerly a botanist), in the late 1800s as a substitute for rice after a period of famine. Understandably, the root became a staple and a “quintessential laborer’s food” ever since.

At Thattu, $6 gets you three sizable pieces of the fried tapioca that come topped with a bit of onion-tamarind chutney. On the palate, the balls display a crisp outer crust that yields to a soft, dense interior that warmly coats your tongue. Given that the serving of chutney is so small, its effect is rather mild at first. The condiment is fleetingly sweet and a little tangy; however, it ultimately builds toward a balanced spice that lasts through the finish. Considering the cassava’s density (and relative blandness), this persistence is impressive. Overall, it makes for a simple—yet surprisingly bold—opening bite that, if anything, would benefit from even more of the chutney (maybe even serving it as an actual dipping sauce?).

Next, you come to the Beet Puff ($6), a dish that follows in a long line of savory Indian pastries stuffed with vegetables or meat. Even more particularly, it can be viewed as an alternative to the egg puffs (i.e., pastries filled with hard-boiled eggs and flavored with ketchup) that are particularly popular in Kerala.

The serving comprises a roughly rectangular pastry puff with an irregular base and some halfhearted crimping on one side. That is to say, the presentation is clearly homespun—moreso in a sloppy rather than a charming manner—even if pocket does its job of keeping the filling at bay. Nonetheless, when you slice into the crust, it shatters cleanly. The vivid red of the beet announces itself but does not leak or ooze. Instead, placing the puff on your palate, its flaky layers crunch and crumble before yielding to an inner reservoir of root vegetable that feels surprisingly meaty. Yes, the beets are not only subtly sweet and a little tangy, but they taste rather savory and satisfying too. You might prefer just a touch more salt, but the filling’s spice is astutely moderated. Ultimately, while it may not exactly look the part, the “Beet Puff” is undoubtedly one of Pak’s greatest creations and a flaky, comforting delight.

With the arrival of the “Eggplant Theeyal” ($11), you encounter the first of the real plated fare (though still listed under that opening “Bites” category). The name of this dish refers to a traditional Keralan preparation said to be “burnt” (theeyal means “burnt dish”) due the dark color provided by the gravy of roasted coconut and tamarind. Prawns and a variety of vegetables are often cooked in this manner, which typically takes on a soup-like consistency.

Thattu’s take on the recipe utilizes the namesake nightshade (not at all atypical for the recipe) and that “burnt” coconut-tamarind gravy. However, by subverting the theeyal’s standard soup form, Pak has created what you might call a deconstruction. Some segments of eggplant, roasted to the point of being black, sit on the plate alongside confited pearl onions and cherry tomatoes. A few rice chips, scattered throughout, enliven the presentation while the titular sauce amounts to little more than a drizzle sitting beneath all the vegetables.

On the palate, the pieces of eggplant are crisp yet meaty and impressively tender. The orbs of tomato and pearl onion, too, melt effortlessly with the slightest bit of pressure. The nightshade, like much of the restaurant’s cuisine, comes powerfully spiced but, if anything, could use a little more salt. This would provide the ingredient with greater savory depth, for the dish predominantly tastes of char (with hints of tomato) yet shines the brightest when you sop up more of the coconut-tamarind sauce. Yes, as a deconstruction, the expert texture of the eggplant is the most valuable thing gained. However, the gravy needs to be thicker or otherwise generously applied to make its flavor more predominant and the whole maneuver worthwhile. Still, this is a very nice effort.

The “Mushroom Mezhukkupuratti” ($13) is the kind of dish that makes you happy to be ordering through a QR code. The pronunciation of that latter term just seems so daunting, yet mezhukku refers to cooking fat, puratti means “coated in,” and the word signifies a kind of stir-fried vegetable preparation that is popular in Kerala (with ingredients like plantains, yams, gourds, and beans being utilized).

For her version, Pak draws upon oyster and button mushrooms that are seared alongside a couple shishito peppers. The resulting combination sits atop a pea purée that has been surrounded by some of the cooking oil. A garnish of coconut chips then forms the final touch. On the palate, the mushrooms are soft and tender. They meld nicely with the smooth purée while being thoughtfully contrasted by the subtle crunch of the shishito and coconut chips. When it comes to flavor, the fungi are expectedly earthy. There is also a hint of sweetness at hand (both from the pea and the shishito). You feel like the dish is a bit boring—that it is missing something—but a delicate vein of spice slowly builds and comes to define the preparation. It imbues those earthy-sweet notes with added complexity and lasts through the finish without ever seeming harsh. In sum, Pak’s “Mezhukkupuratti” grows better and better with each bite, and it demonstrates the chef’s skill at crafting engaging vegetarian fare.

Next, you come to something of a classic: the “Kerala Fried Chicken Bites” ($13) that represent a variant of the “Kerala Fried Chicken Sandwich” Thattu has served since Politan Row. While the latter dish, still served at lunch, comes with the highly praised “ChaaterTots,” the dinner version is more of a shareable appetizer that arrives only with a small cup of yogurt sauce.