While the pandemic has decimated large swaths of Chicago’s hospitality industry, the Alinea Group put on something of a masterclass in taming the black swan. They pivoted to meal kits—first, locally and now nationwide—alongside opening up their wine and spirits cellar for online sales. Grant, Nick, and friends adapted their three Michelin star concept to an outdoor rooftop space—Alinea in Residence (AIR)—and even courted “controversy” (the good kind, that is) with a kooky COVID-inspired amuse-bouche.

The group successfully secured PPP money to help maintain payroll for their hard-working acolytes and announced two forthcoming restaurants in the St. Regis Chicago—set to be the city’s newest architectural landmark. All the while, Grant and Nick’s testimonials for Made In cookware blanketed the airwaves—touting, time after time, that “one of the best restaurants in the world” had put the pots and pans through their paces.

In a time of market constriction—if not outright closures—the Alinea Group has expanded and established their brand across new domains. The molecular gastronomy mavens have transformed into custodians of classic American fare—purveyors of pot pies, canapés, and all manner of holiday meals to the unwashed masses. They have appended their names to products and applied their expertise to kits that refurbish Alinea’s reputation from conjurers of cheap tricks into authorities on cooking and cuisine writ large. The group—led by a new-and-improved, social media-savvy Grant—has embraced and actualized the eminence they have long postured, operating with an expertise and coolness befitting their place in the annals of American dining.

Of course, given your background as Chicago’s lone ranger of Alinea Group criticism, you must qualify your cloying praise. Judging the group on the basis of your experiences dining in The Gallery—as well as a series of high-priced wine dinners—much of this expansion into new directions left you feeling cold.

Why trust a restaurant that resists serving pleasing food at its flagship to meaningfully interpret any manner of classic cookery? Do cooks who have spent the past five years crafting cuisine of style over substance at Alinea 2.0 now have the right to charge costly sums for literal “steak and potatoes” fare? Yes, the group has Roister—a frustratingly-static, stolid restaurant despite its potential—and St. Clair Supper Club—the offshoot that barely qualifies as its own concept—to hang their hat on. But is it ethical to trade on the “Alinea” name to sell meal kits that bear no resemblance to the food one enjoys when shelling out the big bucks for the actual “three Michelin star experience”?

For the Alinea Group’s pandemic offerings have provided Chicagoans—many (if not most) of whom have never eaten at Alinea itself—a “taste” of that highly-touted establishment at a comparatively cut-rate price. The meal kits—emblazoned with the restaurant’s logo and, at times, featuring retrograde dishes like “hot potato-cold potato” or the “tabletop dessert”—seduce customers with direct expressions of gustatory pleasure. They affirm that Alinea’s three Michelin stars denote superlative food when, in reality, the venue has developed into a vehicle for ambient effects and highfalutin presentations at the cost of grounded, substantiative culinary artistry.

You have argued before that Alinea 2.0—in prizing visual, environmental parlor tricks that read well on social media—has abandoned the more difficult work of storytelling on the plate. While set pieces such as the edible balloon are, indeed, quite memorable, this only rings true for first time guests. Past that point, one wonders what just is so exciting about the taffy substance from which it is made. The same could be said for the “tabletop dessert”—its accompanying musical score and the cavalcade of cooks that trot out from the kitchen, while impressive the first time, disguise a jumble of superficially attractive textures and flavors that ultimate fall short of satisfying any sweet tooth.

This is all to say: Alinea, post-renovation, has served up memorable gags and tricks but rarely struck upon truly great food. You recall that “black truffle explosion” and “hot potato-cold potato” were formally retired alongside the transition from Alinea 1.0 to 2.0; however, they were rescued only years later to be introduced as “bonus” bites for “regulars” and VIPs. One could read that as a nice, nostalgic touch or, perhaps, as the telltale of a kitchen bereft of creativity. Not creativity in the shallow, “shock and awe,” “theme restaurant” sense. Rather, a kitchen that has forgotten how to ground their array of molecular gastronomy techniques within legible compositions that yield—first and foremost—gustatory pleasure. Why warp textures and tweak colors when you can concentrate—or contrast—flavors? Why bother the service staff with tableside gobbledygook that already seems dated when they should be altogether focused on forging human connections?

So, when Alinea suddenly looks to cozy up to your family’s holiday table, is it wrong to be skeptical? Would you trust the restaurant whose tasting menu hinges on a sorry sliver of wagyu beef to cook the prized Thanksgiving bird? Doesn’t part of you expect the seemingly-plump turkey to deflate and reveal a bunch of hot air and a few compressed poultry nuggets as sounds from A Charlie Brown Thanksgiving play?

Yet, by all accounts, the Alinea Group’s meal kits pleased Chicagoans. They may have even formed, you think, a sort of lifeline during the deepest antisocial thralls of isolation. Of course, nothing Alinea does is for charity—they make well sure their bread is buttered on both sides. But the Group made their presence felt within the city and across the suburbs. They stayed in denizens’ hearts and minds throughout the year’s socially-distanced special moments, biding the time until those customers would be lured to shoot their wad at the mothership. Because Alinea is a “one and done” sort of place that can blow anybody away the first time only to suffer with each subsequent visit.

Rootless artifice does not a memorable hospitality experience make, especially when the restaurant’s cuisine is made subservient to its social media appeal. Nonetheless, that social media appeal ensures a steady stream of suckers who—having plonked down several hundred dollars per person in a desperate bid to keep up with the Joneses—are desperate to justify their conspicuous consumptive expenditure. They “ooh” and “aah” at the special effects but have curiously little to say about the flavors themselves. To an outsider, it all sounds and looks like Willy Wonka. The tacit assumption is that the food was “good,” if not “great” (Alinea is “one of the best restaurants in the world” after all). But, in reality, the failure of the cuisine to resonate with the audience is hidden behind layers of impenetrable abstraction.

You have argued all of this before and need not continue to do so here. The point is: the Alinea Group has pivoted towards being a purveyor of delicious food (via meal kits) after several years of serving up disappointing nonsense at their lauded “three Michelin star” establishment. If the talent and technical knowhow was clearly present all along, why did Alinea 2.0 veer headlong towards cooking that left local and repeat patrons feeling cold? Is it wrong to view Grant and Nick as opportunists for whom customer satisfaction only matters when stripped of the bag of tricks they typically use to gouge and deceive diners? Does such a lens not out them—as if it wasn’t obvious all along—as businessmen who happen to sell fine dining experiences rather than bonafide hospitality professionals?

Surely, 2020 sent the Alinea Group some sign that their schtick is getting old. The Aviary and Office NYC franchises—located in the ritzy Mandarin Oriental and overlooking the soulless consumer mecca known as Columbus Circle—fizzled out in February. Kokonas and crew took some unwarranted fire from clickbait rag Eater for having “blindsided” its employees with news of the closures. However, you buy the Alinea Group’s defense that all staffing decisions made after their separation agreement—specifically, the furloughing of the staff in late March—were solely made by the Mandarin Oriental. Even the Eater article concedes that “Aviary and the Office staffers are unionized Mandarin Oriental hotel employees—not Alinea employees.”

The affected parties, of course, are right to mourn their transformation from representatives of Chicago’s lauded molecular mixology establishments into anonymous “hotel bartenders.” But the larger story—lost among the widespread closures that followed throughout 2020—is that the ventures—completely independent of the pandemic—fell flat.

Goaded by commenters on the Eater article who characterized the Alinea Group’s partnership with Mandarin Oriental as being fueled by greed, Kokonas responded. Declaring that the group “made more money on each of our other operations [based in Chicago],” he saw in the hotel “an iconic space overlooking Central Park in the best food city in the US and perhaps the world.” Kokonas saw the venture as an opportunity, “perhaps, to bring what we do to other parts of the world” and admitted he “put nearly 5 years into planning it—unpaid.”

As the Alinea Group takes aim at another luxury hotel partnership—this time on “home turf”—can they be sure they have learned from their failure in the Big Apple? “It didn’t work out for many, many reasons,” Kokonas admits. But, as with the Alinea flagship itself (a place he proudly, for some reason, declares he no longer eats at), he fatally misunderstands the value (or lack thereof) of the brand he has built.

You are not a “New Yorker,” but you resided there long enough to develop some sense of the city’s dining scene. Interlopers who are only looking to peddle a facsimile of what made them famous in some other (likely more “minor”) location are not bound to succeed. Even ostensibly new concepts from hallowed hospitality names are likely to have a rough go of it.

Aviary’s eye-catching cocktails and The Office’s collection of antique spirits shine in a city bereft of luxury and—in many ways—a strongly-defined identity. The Alinea Group’s properties appeal to travelers coming in and out of Chicago who lack the insight to engage deeply with the local culture. They survive on the added traffic drawn from residents who have been hoodwinked into thinking they represent the city’s “best.” But that benefit surely comes by being a big fish in a small pond whose stiffest competition over the years (L2O, Grace) met untimely ends.

In New York, you surmise, the Alinea Group lacked the panache to compete with the litany of visually appealing options clogging social media at any given moment (you think, for example, of the heyday of the Black Tap milkshake). At the same time, they were not quite so ridiculously luxurious as to lure in the city’s whales. Not to mention, there was little sense of value, storytelling, or rootedness to New York that would appeal to more aspirational patrons. Kooky cocktails that—even in Chicago—could never be called the best tasting in the city simply hold little currency in a place that is spoiled for choice. The Alinea Group’s prizing of visual, presentational aspects of hospitality proves to be an Achilles heel when put up against New York’s native masters of viral marketing. And few people, even in Chicago, could really feel they are getting their money’s worth when visiting one of the group’s properties.

Thus, New York’s Aviary and Office franchises existed as insulated luxury hotel bars offering views “overlooking Central Park” that no native New Yorker would want to be sucked dry to see. Establishments that feel sexy in Fulton Market can only be read as craven cash grabs when situated in such a place as Columbus Circle. For molecular gastronomy and mixology only shine in the shadow of Chicago’s insecurity regarding being an unabashed representative of “Midwestern” or “American” cookery. Smugly contrived smoke and mirrors—bereft of both value and soul—mean little to residents confident of their place in a cultural capital. In Chicago, they only succeed due to a deferment to higher powers such as Michelin and a sense of self-hatred that accepts the erasure of local identity by our supposed standard bearer.

When the first attempt to copy the “Alinea” brand to another location falls flat, is it not right to ask what the group’s strategy of snubbing local tastes was all for? It is with this mindset that you approached “Alinea 3.0,” the Lincoln Park restaurant’s long-awaited revival.

In the leadup to that fateful encounter, you had enjoyed your sole visit to AIR—Alinea’s summer rooftop residence—but hardly found it life-changing. The group did an admirable job staging guests’ entrance into the space, leading them through an illusory hallway inspired by Alinea 1.0’s optical trickery. The COVID-inspired bite that drew so much “controversy” did not even read, to your eye, as if it was referencing the virus. Perhaps you were too taken in by the novel space and the looming elevator ride. Or, maybe, you were too focused on escaping the masked gaze of the restaurant’s greeters. Alinea has always struggled to welcome guests warmly—compared to, say, Oriole—and you regularly find yourself rushing to the relative comfort of the table to avoid awkwardly standing around and grasping for anything more to say than “it’s nice to be here.”

In any case, the “COVID canapé” clearly suffered under the static microscope of social media—which makes you think the whole hullaballoo was encouraged, if not concocted, as a means of self-promotion. It was as if to say that Alinea could still be playful and subversive in its advanced years as an institution. Point taken, but imagine if that coconut, raspberry, and Szechuan (!) peppercorn morsel had really tasted amazing? Then you’d have something to talk about.

Forcing the cooks to prepare food only using outdoor grills for heat made for an impressive impediment to Alinea’s usual molecular gastronomy style. Of course, the rooftop also denied them the opportunity to embellish the experience with some of their typical ambient effects. (You suspected the multicolored, many-shaped sculptures the staff maneuvered from place to place within guests’ eyelines would amount to something. But no, they were just window dressing to help mediate the—at times—lamentably long wait between courses).

Certain dishes, such as a pork and peach croissant sandwich and a corn soft serve ice cream (with honey-butterscotch, bacon, and truffle) were rather delicious. They count as two of the most directly pleasing creations to come out of the Alinea kitchen since the dawn of “2.0.” Other creations, like a salt-roasted watermelon made in the style of mojama—a Mediterranean salt-cured tuna—displayed some of the restaurant’s usual, intelligent manipulation of texture.

However, you thought a closing course composed of a trio of Fruition brand chocolates was utterly contemptible. Eleven Madison Park, for example, has long invited guests to play “guess that milk” with an array of custom-made and packaged chocolate bars derived from cow, water buffalo, sheep, and goat milks. Of course, it’s still a bit boring when a top class restaurant serves you something premade—but at least EMP made it into a game! Alinea’s presentation of the Fruition chocolates reads like sponsored content. It has not the slightest thing to do with the restaurant, and the brand itself has nothing to do with Chicago or the Midwest. You can only hope that Fruition made it worth Nick’s while.

Overall, AIR was little more than a diversion. It felt like a way for the team to stretch their legs—rarely striking upon genius, but generally enjoyable. The “action,” by necessity, was forced to occur altogether more on the plate in conjunction with select tableside presentations. To that effect, the dishes engaged guests—many who hadn’t been out to eat in months—to an extent, but they told no story, possessed no particular identity. Few of the creations—other than those aforementioned—live on in your memory.

Alinea, stripped of its setting, is merely a showcase for a jumble of molecular techniques—transformations of texture and form—that detract from the achievement of superlative flavor. Yes, it was a feat to do any justice to that “style” on an outdoor rooftop. But the sparseness of the space made all the more clear how much of a crutch the restaurant’s usual environmental artifices have become.

Still, as ever, charging premium prices, AIR made clear that the Alinea Group views itself as a luxury brand that can toy around aimlessly with food and expect suckers to lap it up. They choose the path of offering provocation and meagre pleasure to conspicuous consumers who have already been “sold” by the exclusivity of the experience long before they have taken a bite. In doing so, Alinea ignores the much harder work involved in shaping a meal that is deeply satisfying and emotionally resonant.

And therein lies the essential tension: Alinea has demonstrated they can craft meal kits that, while expensive, utilize the kitchen’s technical expertise to deliver hedonic pleasure, yet they build tasting menus that shirk that type of satisfaction in exchange for superficial, social media, theme restaurant fare. Put another way, the Alinea Group gives the public what they want when they stand to make money doing so. Otherwise, the restaurant exists only to blow smoke, to seduce first time customers with the promise of an incredible experience that ultimately has little to do with the appreciation of cuisine. Alinea pleases palates when they are forced to, but, otherwise, they have found that doling out camera-friendly fluff ensures far better margins.

Such a gambit sure as hell did not work in New York. Would the Alinea Group pick up where they left off in Chicago? AIR had shown some promise, and a second residency at the Ace Hotel (which was scuttled) might have offered another opportunity for a renewed focus on food over fluff. Do they want to be the Alinea Group that entered Chicagoans’ homes during the pandemic and offered—putting all their tricks, for once, to great use—delectable holiday fare? Or do they want to be the “three Michelin star restaurant” nobody can make sense of (but that everyone, in their subsequent Instagram post, makes their best effort to pretend to)? Will the Group’s tone, moving forward, be the same old tune of smug, impenetrable, superiority? Or will they step into the role of standard bearer they have for so long reaped the benefits of but never actually embodied?

It is with all this in mind that you entered Alinea—“3.0” you have termed it—on the long-awaited day of its reopening: March 17th, 2021. You were the first party to glimpse what had been lurking, festering in Grant and co.’s minds during the many months spent serving a quite different sort of food. And you could begin to sense, for yourself as much as Chicago, just what path forward the Alinea Group would choose as it leaves NYC behind and prepares to lay down yet stronger roots at the St. Regis.

As is typical, you will present your experience in a narrative form. However, given this article concerns one particular meal on one particular evening, there will be no need to condense multiple meals into one package. Instead, drawing on your history of dining at Alinea during the past decade, you will look to contextualize the current “3.0” menu with regards to the restaurant’s “1.0” and “2.0” iterations as you understood them. All else having been said, let us begin!

That familiar stretch of North Halsted Street is, at long last, back to its usual, subdued state. The throngs that clogged traffic—even taking over the parking lot across the street—have dissipated now that Chicagoans have had their fill of “Alinea at Home.” Sure, some Johnny-come-latelies may still whip in and out to secure their taste of “three Michelin star cuisine” (which, at present, entails a smoked ribeye with cherry Bordelaise). Alinea’s curated holiday meals, of course, still carry the allure of one time only extravagance. But there can be no denying it: the restaurant has reopened, and any alternative streams of income necessarily become afterthoughts in the shadow of the tasting menu proper.

Reservations for the reopening menu—only a mere day or two after its announcement—were booked solid. A two-top at Alinea remains one of Chicago’s most difficult tables, yet it must be said that even the four-tops and six-person kitchen table have seen high demand. At present, only a select few timeslots on Wednesdays and Thursdays in May remain available for these larger groups. Interest in Alinea from travelers—foreign and domestic—can always be assured; however, you wonder to what degree their presence has remained stymied.

Surely, Ever’s opening has proven that Americans from outside the Midwest are willing to brave the pains of pandemic travel for the sake of appreciating dining of the highest caliber. And Alinea, it must be said, continues to enjoy a unique “bucket list” status among the nation’s elite—shining all the more brightly due to the dearth of comparably branded or conceived concepts in the region. At the same time, establishments of Ever’s or Alinea’s class transmit a sense of expertise and security when it comes to preserving public health. All the precision and attention to detail demanded (or, shall we say, advertised) by their cuisine translates easily into an obsession for hygiene and sanitation across the entirety of the guest experience.

Thus, diners who have heretofore avoided patronizing restaurants in person may have been holding out for an institution of Alinea’s reputation to reopen. Likewise, the backlog of celebrations deferred throughout 2020 may have found a natural home at this “special occasion restaurant” par excellence. Of course, you cannot know for sure if Alinea is experiencing an uncommon swell of local diners at the moment. But conditions—not least of all a dampening in overall culinary tourism—could mean that the restaurant is serving a greater proportion of Chicagoans now that is equaled only by the period following the original opening of “1.0” in May of 2005 and the (re)opening of “2.0” in May of 2016.

In any case, the stage has been set for some sort of reintroduction—to restaurants, to fine dining, to the Lincoln Park flagship itself—depending on where exactly a given patron lands. For you—palate sharper than ever—it can only be the latter. With a few mid-pandemic visits to Ever and Smyth under your belt, Alinea cannot expect much mercy for merely deciding to reopen. Nor can they coast on the novelty implicit in escaping into dining rooms once more. The food and hospitality experience must speak clearly and proudly as the elder statesman of the city’s dining scene. Otherwise, at this late stage of the game, why not simply wait longer until the concept has something truly interesting to say?

You exit your Uber and sidestep the disoriented valet. He recovers quickly enough to reach the restaurant’s front door and holds it open as you guide your date curbside. She enters first, and you shimmy into the slender entryway right after. Three masked faces man Alinea’s front desk. You exchange a flurry of nods and smiles (that go unseen hidden underneath your mask). Words, as they usually do at this moment, fail you. The best you can stammer is that “it is good to be back,” that it is “nice to see them,” and that you are “excited to see the new menu.” There will be a new menu, won’t there?

Putting you out of your misery, one of the hosts hustles you out of the hallway and into the dining room proper. He confirms that you are the very first party to be seated on this, the reopening evening, as he passes the ground floor Gallery and guides you up the restaurant’s staircase. Oh, what memories climbing these steps conjures: of all the nights spent at Alinea “1.0” when you would invariably be whisked to one of the upstairs chambers, wondering just who was so special to deserve being seated downstairs. Then, with the dawn of “2.0,” your predilection for The Gallery experience meant you never scaled those steps again—until now.

You cannot say the second floor dining room looks all that different from what you remember more than half a decade ago. Sparseness reigns along with a smattering of neutral tones, slick banquette seating, and shiny metal tabletops—surely a replacement for germ-catching linen—that lend the environment a sort of space-age appeal. All the better for molecular gastronomy, you think. Nothing hanging from the ceiling, nothing under the server’s sleeves. Just ample room for the drama that occurs on the table—and nary another customer in sight.

Having neglected to choose a beverage pairing beforehand, the sommelier—an Alinea veteran who had made his way to Boka and, recently, back to the mothership once more—approaches and gets down to brass tacks. You order two of The Alinea Pairing—“the rarest wines from our collection — limited availability”—despite lingering reservations regarding its ultimate value. You also ask to browse the bottle list—which, unlike some recent past experiences in The Gallery, arrives promptly.

You have written plenty about the nature of Alinea’s wine service, both within the context of the restaurant and across the larger scope of the Group. Though Grant initially had something of a manager/sommelier partner in Joe Catterson, it seems the latter’s fear that Tock would render the restaurant inflexible (and, thus, to some degree inhospitable) forced him out. What followed has been a carousel of talent with no one name rising to embody either the restaurant’s sense of hospitality or its beverage program. Turnover just occurs too quickly, and there seems to be no clear path towards team members taking ownership over these dimensions of service in a traditional sense.

The wine pairings—and the wine list itself—have often appeared scattershot. Rare bottles—unseen at any other establishment in the city—mingle among utterly thoughtless and anonymous selections that might as well have been poured directly into your glass by the distributor. Yes, of course, Alinea’s food can present some difficulty for sommeliers designing pairings. But a long-term wine director might have gotten to know the building blocks of the kitchen’s cuisine and found a reliable, structural approach to increasing guests’ pleasure through beverages. They might have managed a cellar for the long haul, rewarding patrons with perfectly-aged riches that cost only a fraction of their price on the secondary market. But, at a certain point in the past, Alinea decided a “good enough” wine program would suit their purposes, and they put all their effort towards urging customers to choose from one of three readymade buckets: the “Standard,” “Reserve,” and “Alinea” pairings.

While the Alinea Pairing, on this evening, again failed to live up to its $395 price tag, you think it took a small step in the right direction. The chosen bottles—which you will discuss more in the context of the particular dishes where they appeared—largely comprised grand cru (or equivalent level) expressions of traditional Old World grapes. Some wines showed a bit of age—and some, essentially, were current release—but the combination of lauded producers and estimable appellations will likely do enough to inhibit feelings that guests’ money was wasted by purchasing the highest tier. A 2008 vintage Australian Semillon and a Junmai Genshu (undiluted) sake were probably the most “adventurous” of the pours—which is to say that the selection avoided any polarizing displays.

How would you like to see Alinea’s wine pairings transform if they are to earn “full points”? Well, you would point to Smyth’s “Super Mega” pairing that is currently being crafted by an Alinea alumnus for $60 cheaper than the “Alinea Pairing.” The two pairings, in truth, share much of the same general structure. They even both incorporate a bottle of Billecart-Salmon’s 2006 “Cuvée Nicolas François” towards the midpoint of the meal. But Smyth’s selection is defined, to you, by a bit more age on the bottles: a 1997 Trimbach Cuvée Frederic Emilie and a 1990 Cos D’Estournel being the most aged white and red wines served versus the 2008 Tyrrell’s Semillon and a 2005 Château Canon en magnum at Alinea.

While Smyth serves a sake that has been aged for 15 years—replete with bitter, caramelized notes—Alinea’s sake is of a richer and rounder style (and costs about half the price of the former). While Alinea pairs its caviar course with the aforementioned Billecart-Salmon bottle, Smyth reserves it for a preparation of Maine lobster tail. Instead, Smyth’s warm preparation of caviar is juxtaposed with a pour of Palo Cortado sherry that expresses, in the roe, a profound nuttiness unlike any you have ever experienced. It’s that rare sort of wine pairing that helps the given dish transcend anything it might have expressed alone. It is bold, controversial, and it unerringly worked the three times you have had it.

So, with that in mind, you think Alinea needs to play things a little less safe. Their high-end pairing should not be structured to overload patrons with a smattering of good and great wines with recognizable labels that look to avert failure. You would rather see a couple carefully-conceived combinations of wine and food anchor all three tiers of the pairing—making use of allocated or otherwise unknown producers marked by the character of their wine as expressed by, through, and with a particular dish. These do not need to be expensive bottles by any means—it’s all the more impressive if they are not. Rather, these pairings would underline the talent of the sommelier and the harmony that can be achieved by putting beverage in perfect tandem with a dish. Alinea tried to do such a thing with a mezcal pairing during “2.0,” but it was ill-conceived and, like most of their pairings, stood apart from the food (contrasting it) rather than truly completing it.

Once these “perfect” pairings are pegged, they can form a common thread that unites all three tiers of price. In some sense, they can speak for what an “Alinea wine pairing” (in the abstract) truly is: wine not just as an optional appendage to the smoke and mirrors but, rather, an integrated element with untold depth and potential for experimentation. With some amount of the pairing being instituted in this way, the remainder of guests’ money—especially for the upper two price points—can be diverted towards offering a smaller amount of luxury wine from the very best producers, appellations, and vintages. Rather than “playing the field” competently, this mixed format would enable Alinea to serve absolute jewels of wines that will leave a lasting impression. However, as with crafting the more adventurous, “common thread” pairings, selecting wines of this caliber demands a wine director who possesses proper ownership of this domain and the requisite vision to put such a cellar together.

The one real positive thing to note regarding Alinea’s wine program this evening is the absolutely shocking expansion of its bottle list to something like triple its previous size. Such a change was all the more surprising, given that the restaurant had offered select bottles from its cellar for sale online during the pandemic. The sommelier, as best as you can remember, admitted that the team finally had the time to do a proper inventory and compose an expanded version of the list that, at long last, comprised the entirety of their holdings.

With that one move, Alinea’s wine list has instantly become the best in the city. Browsing the selection, you felt absolutely spoilt for choice. You even found yourself ignoring the presentation of the first couple courses in order to steal a bit more time scanning its breadth. Perhaps that was the driving force behind listing only a fraction of their holdings? That Alinea wanted to avoid guests getting sucked into choosing beverages when “showtime” (especially in The Gallery) loomed? But, if the goal all along has been to push the pairings, would not an imposing tome packed full of options deliver overwhelmed customers into their hands?

To be clear, you would not necessarily label Alinea’s expanded wine list as overwhelmingly generous. The strongest sections in the previous rendition of book—such as Klaus Peter Keller’s Rieslings (including several vintages of the G-Max)—have, as admitted to you by the sommelier, seen their prices increase in line with the secondary market. However, sections such as Burgundy (both white and red) feature a bevy of options with some amount of age and prices that fall below the usual two times markup expected at restaurants. For example, you ultimately decided on ordering a bottle of 2011 de Vogüé Bonnes-Mares that—being priced, as best as you can remember, between $600 and $700—falls well short of the average Wine-Searcher price of $476 once a typical markup of 100% is factored in.

This discussion of wine pricing might all seem rather remote from the experiences of the “bucket list,” aspirational fine diner. However, it is a most welcome change when judging Alinea as a senior statesman of Chicago dining and a bonafide national gastronomic institution. A restaurant holding three Michelin Stars for 16 years should possess a cellar worth showing off. They do not, under any circumstance, need to give the wines away. But there should develop natural sweet spots of pricing that, even if the restaurant makes a healthy margin, resist some of the speculative extremes of the wine market. Alinea, now that it has put all its cards on the table, can be proud to offer such a list.

Any criticism of the restaurant’s wine pairings is partially undone by offering oenophiles such an olive branch. Rather than spend $395 per person on a flight of the most premium wines, wine-loving guests can divert those resources towards crafting their own accompaniment from a litany of options. This empowers the pairings to tell a story that is fit for an audience featuring variable levels of wine knowledge without needing to carry any special appeal for the geeks and nerds. They, instead, can cherry pick the bottles that tickle their fancy and revel in the rewards of such longstanding cellarage.

You must only ask—what took Alinea so long? For a restaurant group so obsessed with monetization, how could they stomach leaving so much of their stock unlisted and unaccounted for? How could they, in good faith, hold back from offering guests every chance at finding a bottle of wine that pleased them?

Perhaps, in due time, the bottles that have only now made their way onto the wine list would have been drawn on for future pairings (or, dare you say, future wine events). Perhaps the high turnover within the wine team and lack of long-term leadership naturally prevented any comprehensive inventory from being conducted until this moment. Or, maybe, Nick is in possession of some data that demonstrates nearly every customer opts for some manner of pairing and that the purchasing of separate bottles from the list in no more than an incidental occurrence.

Whatever the truth, it always seemed as though Alinea’s wine service was holding out on you. It was frustrating to think of the sort of allocations a longstanding restaurant of its caliber had surely been offered—only for there to be no sign, browsing the list, that they had been seriously collecting bottles at all. Alinea’s wine list now, at long last, fits the stature with which the restaurant carries itself. You might still disagree with some of their posturing, but you also must celebrate a firm step towards rewarding the sort of repeat customers whom you have felt have long been hard done by. Great, truly great, wine forms a natural companion to such finicky, molecular food. It offers the depth of flavor that such kitchens’ disjointed compositions sometimes fail to achieve. In that sense, a generous wine list forms the best buffer between the overreaches of experimental cuisine and the realization of an overall sense of satisfaction.

Speaking of cuisine, the time has come to grapple with just what the Alinea “3.0” experience looks, smells, and tastes like. You would typically include “sounds like,” but the realities of the pandemic—as you have alluded to earlier—have worked to rob the restaurant of essential elements such as the musical crescendo that accompanies the “tabletop dessert.” Yes, in some sense, adapting Alinea to a socially-distanced, streamlined state has tied one hand behind the kitchen’s back. Given how much, in your opinion, the restaurant has leaned on smoke and mirrors throughout 2.0’s menus, tying that hand is more like an amputation.

Can the back of house still cook? Can they conceive of dishes that merely play within the boundaries of the plate? Can they design clever, provocative creations that speak only through texture, flavor, and form?

Molecular gastronomy, as a genre, is undoubtedly the most difficult style of cookery to adopt. Placed within a well-defined cultural frame, such warping of ingredients may remain grounded by referencing some manner of nostalgia, accessing some legible concept drawn from the culinary canon. Alinea 2.0, in its odes to Dalí, Steak Diane, and Tournedos Rossini, had inched towards such a practice. But those presentations—few and far between—always read a bit too consciously as a sort of “bone throwing” to customers dissatisfied by the rest of the experience. They enabled the kitchen to indulge in their usual abstractions guilt-free, oblivious to the manner in which many fell flat.

Moreover, Alinea largely resists any identification with Chicago or the Midwest, which makes references to American (Steak Diane) or European (Dalí, Rossini) culture seem contrived. They are table scraps situated within a menu that privileges international appeal over a sense of place. And, perhaps, therein lies the key to the whole concept: smoke and mirrors read well across all cultures while sidestepping the deeper, foundational elements of gastronomy that are far harder to cultivate (let alone sell).

So, stripped of their lavish ambient elements, would the dishes served at Alinea “3.0” look to find some stable footing within a local, regional, or national cultural context? Would they weave a largely more legible narrative that works to explain why certain techniques were applied to certain ingredients? Would the food, for once, simply taste better? Would it finally fulfill the (mistaken) reputation that Alinea is Chicago’s “best restaurant”?

Or were all those meal kits filled with comfort food merely a marketing ploy? A stopgap, a shell game? And now Alinea could go back to adopting its usual, smug, impenetrable aura—one through which they do not serve fine food so much as hot air.

You are pleased to share that Alinea’s reopening menu (“3.0,” as you call it) ranks as one of the strongest you have experienced since the days of 1.0. That is to say, by forcing the kitchen to focus firmly on the plate—rather than the larger dining room—they have achieved a collection of dishes that surpasses more or less every menu you can remember being served in 2.0’s The Gallery space.

Given how outspoken you have been in your criticism of the restaurant, you felt a sense of relief after the meal. Faced with the suppression of some amount of their usual creative freedom, Alinea shone all the more brightly. They pushed boundaries within the realm of the table, packaging dishes in a clever, thematic fashion that felt far less alienating than usual. The kitchen was cooking as intelligently as ever but doing so in such a way that the “idea” driving each dish—even if its form was highly abstract—could be comprehended. Their molecular gastronomy, for once, felt grounded. And, in doing so, the restaurant has started, once more, to fulfill the reputation it has cultivated over the past sixteen years.

The meal began not with caviar, but a raw preparation of scallop. Thin slices of the mollusk coated the bottom of the serving vessel, which itself mimicked the shape of a scallop shell. The gossamer morsels of shellfish were joined by halves of pitted Picholine olives, and the whole composition was blanketed in a coating that approximated gold spray paint. This gold element did a great job of clinging to and obscuring the other ingredients, resulting in a plate that looked something like a shining crater. (Titled “Scalloped” on the menu provided at the meal’s conclusion, the dish seems to reference the appearance of scalloped potatoes, where a cream sauce yields a similar glossy finish to the top layer).

The “bumps” formed by the olives looked as though they might be crisp air bubbles, but, working your way into the dish, the Picholines struck you with the softness of their flesh and the mouthfilling quality of their juices. In terms of flavor, the olives imparted layers of citrus, brine, and butter that formed a perfect complement to the luscious strips of scallop hidden below. It’s a brilliant pairing of ingredients that you might interpret as a takeoff of a crudo; however, the substitution of olive chunks for a coating of oil is substantially more interesting. In the same manner, the plate’s gold coating adds a sense of mystery and visual denial to the experience that allows the elegant juxtaposition of such superb textural forms to take diners by surprise.

Your menu names one more ingredient—“blood”—which your memory of the dish cannot quite account for. Whatever the blood’s origin (pork seems likely), the subtlety of its presence points to its function in shaping an added perception of viscosity and richness by which the mollusks’ mouthfeel could further shine. As it happens, that undercurrent of meatiness would have formed a fitting partner for the chosen pairing: a 2006 Dom Pérignon Rosé boasting some 20% still red wine in its blend. While such a sparkling wine certainly appeals to “label whores” (what Dom Pérignon product would not?), the rosé commands the respect of oenophiles as well. It made for a start to the meal that was both luxurious and bold.

This dish—visually provocative but directly pleasing—was far cry from the dehydrated scallop (or, sometimes, langoustine) paper served at Alinea 2.0 that guests were supposed to reconstitute in a bouillabaisse sauce. That was an interesting idea but, ultimately, an outright denial of the ingredient’s immense textural pleasure. In that case, the presentation overshadowed the eating experience. Here, as is proper, the gold coating is merely a garnish placed on top of a structurally sound creation.

The next dish that evening—titled “Charred”—indulged in another play on words. A sturdy glass platform arrived at the table, the surface of which was designed by the glassblower with an inlaid bubble design featuring yellow, orange, and purple. Atop that sat a healthy sliver of arctic char whose skin, itself, had been charred to an impressive, carbonized sheen. The fish was seasoned further with maple syrup (which no doubt played a part in the impressive crust) and fish sauce. As a bite, the arctic char was straightforward in its satisfaction: the sweet notes of maple and added umami of the fish sauce amplified the fish’s fatty, flaky flesh. The crackling top layer of skin, of course, was quite impressive—it provided an essential contrast to the more gushing nuggets of the fillet.

But could the dish really be that simple? Just a bite of (admittedly excellent) arctic char served on a fancy piece of plateware with no further ostentation? What sort of “Alinea” is this?

Before you could exactly dwell on that question, your server returned with two spoons and instructions to flip the plate over. Doing so, the wider upper platform upon which the fish was perched now formed the base, and the smaller, lower platform now faced upwards. The colored bubbles had obscured the fact that the base of the plate was hollow, having contained—in suspension—the second part of the dish all this time.

Smoked char roe was encased in a gel that prevented it from falling while upside down. The pearls—possessing a sort of matte orange hue—camouflaged themselves perfectly among the multicolored bubbles embedded in the glass. They were paired with flavors of carrot that balanced the roe’s smoke characteristic with a touch of sweetness and vegetal depth. But this second part of the dish, not unlike the charred skin of the previous component, was a textural achievement above all else. The gel which had suspended the pearls was actually rather soft upon being broken. It encased the roe with an added coating that highlighted the delicacy with which each orb burst.

The accompanying wine pairing, Jean-Louis Chave’s 2013 Hermitage Blanc, matched all this textural intrigue with the classic oily, waxy sensation found in the white wines of the Rhône. Concentrated flavors of stone fruit, nuts, and an impressive minerality—unadorned by any harsh, driving acidity—managed to meld with everything from the maple syrup to the carrot element ensconced with the smoked char roe. Ah, the smoke—and the fish’s “charred” crust—that’s where this Hermitage Blanc really shone. You cannot think of any wine that could fit the part so well, and you tip your hat to the sommelier despite having been disappointed by the Alinea Group’s Chave Hermitage wine dinner a couple years ago.

As a duo (and a bonafide surprise you in no way saw coming), the arctic char was an unquestionable success. You found the interplay of the plate’s design and the structural role of the gelling technique to be a match made in heaven, a testament to the kind of partnerships and solutions molecular gastronomy might perform. Further, though you cannot remember if it was said, you believe both the maple syrup and the smoked char roe itself were sourced from BLiS in a nod to Achatz’s first mentor Steven Stallard. Use of BLiS products is one of the chef’s rare personal conceits—and a connection to the Midwestern region via Michigan—and it demands special praise given your longstanding criticism that Alinea resists expressing any sense of place.

Next, succeeding the scallop and arctic char, arrived crab. “Royalty,” the course was later titled: a duo of Alaskan king crab and Maryland blue crab. The former crustacean was shaped into a dark-red mantou—better known to Americans as a Chinese steamed bun. The latter variety of crab was processed into soup as an ode to William Deas, the black butler whose improvised recipe for She-crab Soup was served to President William Howard Taft in 1909 (and thereon became a hallmark of South Carolina’s culinary heritage). Deas is credited as the first cook to enrich a typical, pale crab soup with the addition of the crustacean’s roe, lending the dish an added depth of flavor and striking orange color.

Both the king crab mantou and blue crab soup were served in intricate, custom glass sculptures made in collaboration with Ignite Glass Studios, a local workshop situated not far from the Alinea Group’s outpost in Fulton Market. The glassblowers there are somewhat of specialists at depicting aquatic life in fine detail, making use of thin, translucent materials that feel pleasantly lightweight and delicate in the hand.

For the “Royalty” course, Ignite fashioned a piece of glassware that replicates the head of a blue crab (recognizable due to its pointed sides) and two front-facing claws. The top of the head features a slight dimple that serves to hold the mantou in place. A second piece of glassware retains the same claw structure but inflates the head of the crab to conch-like proportions. The oversized shape serves as a sort of flask from which the soup can be sipped. Needless to say, both sculptures are striking—uniting form and function while underlining that Alinea, as an institution, endeavors to support Chicago’s larger artistic and cultural scene.

However, while the course’s presentation pleased you, the subsequent bites and sips the two dishes offered fell slightly short. You like the idea of serving a Chinese steamed bun and found the thinness of the wrapper, as well as its deep red color, appealing. It adhered to the shape of the king crab nugget rather well, excising the extra dough that sometimes characterizes clunky technique. Nonetheless, while the quality of the wrapper ensured the crustacean’s texture was featured front and center, you found that the bite lacked adequate flavor. Yes, the bun’s slight sense of chew enhanced the soft chunks of crab, but why choose the mantou form at all if it does not offer an adequate filling? Any additional mouthfeel imparted by the wrapper must be balanced against the moistness it draws from the crustacean. The application of a light glaze or dressing would have transformed the bun from an attractive novelty into a more complete and satisfying bite.

In the same manner, Alinea’s play on William Deas’s famous She-crab Soup went down easy but spoke a bit too softly. The kitchen did a good job with the serving temperature: the liquid was warm but stood no chance of singeing guests’ palates. (In fact, you might recommend aiming a few degrees hotter, so as to preserve a greater cleansing sensation when the liquid flows down your gullet). The soup was plenty savory—stamped with the richness of the blue crab’s roe—but lacked an added dimension. That could have come from a more intensely extracted stock or a touch of something like sherry. Truthfully, it could have come from any number of techniques, but you are right to say that an “Alinea” crab soup, no matter how charming its receptacle, should shine more brightly than the average steakhouse bisque.

The 2008 Tyrrell’s Wines “Vat 1” Sémillon from Australia, it must be said, lent a nice sense of body—as well as notes of butter, toast, and ripe exotic fruit—to the composition. Undoubtedly one of the pairing’s cheaper bottles, it testified to the age-worthiness of the region’s white wines—even under screwcap! The Sémillon overperformed, melding well with the mouthfeel of the mantou, but it could not quite rescue either dish from lacking that something extra.

Crab—of all types—stands as one of your very favorite ingredients. You enjoy seeing Alinea work with it—especially in such a manner that juxtaposes several species—but the restaurant must be sure that each bite of the crustacean resounds with untold flavor. Preparations of king crab at Smyth and Ever, for example, are far more indulgent (and rather unique in their presentations too). You even think Kyōten’s combination of king crab and corn sorbet, as well, easily outdoes Alinea’s effort with elegance and simplicity. The Ignite Glass sculptures—which will soon also find their way to Mauro Colagreco’s Mirazur—are well worth using. Alinea needs only to concentrate its powers and use those pieces as containers for the most captivating crustaceous creations Chicago has ever seen.

For the next course, the dainty glass crabs were swept away and replaced with a familiar piece of plateware. You might call it the “XXL plate,” seen throughout Alinea 2.0’s menus as just about the largest canvas utilized by the kitchen (other than the table itself). The dimensions of the piece—which is rounded but not precisely circular—ensure that the spotlight is trained on its center. At the same time, the plate’s uneven circumference preserves a sense of abstract design that complements the kitchen’s own painterly hand.

Sitting at the center of the plate—and anchoring the dish altogether—is what appears to be a single floret of cauliflower. It boasts a picture perfect crown of curds and a couple green leaves that signify its supreme freshness. The cauliflower sits atop a Jackson Pollock splatter of “black curry,” and it all—again—seems rather simple as far as Alinea is concerned.

But then, the server reveals that those “curds” of cauliflower (the appropriate name for the edible white flesh that hangs off of the vegetable’s stem) are actually proper, Midwestern cheese curds. The dairy is freshly churned and formed in-house before being plated and coated in a layer of cauliflower purée, whose rough texture helps create the illusion of an actual floret. The cauliflower stem at the center of the plate, of course, is real—having been lightly steamed. And the black curry, which so whimsically accents the oversized canvas, is made from black lentils, black sesame, and garam masala—an Indian spice mix that typically includes fennel, bay leaves, peppercorns, cloves, cardamom, cumin, and coriander (to name but a few components).

In a manner reminiscent of the crab duo that came before it, this play on cauliflower/cheese curds looked more interesting than it tasted. Doesn’t that sound like the criticism you have always made regarding Alinea’s cuisine? Yes, perhaps, but also no. You have long disliked seeing the restaurant use ambient “smoke and mirrors” to distract from the action on the plate. However, in this case, you applaud the fact that the cauliflower dish’s cleverness is wholly contained within the serving vessel. The visual trick succeeds without a hitch, surprising guests with the way in which a careful layer of purée (piped onto the cheese curds) can double for the grooves of an actual floret. Likewise, the continued embrace of double meanings (“scalloped,” “charred,” now “curds”) imparts an appealing internal logic to proceedings. Compared to how impenetrable, how out of left field Alinea can sometimes be, these (actually rather subtle) puns provide an essential structure to the meal.

And the flavor of the cauliflower and cheese curd dish, it must be said, is by no means faulty. Rather, the composition offers more of a textural experience: the crunch of the vegetable’s stem, the chew of the cheese curds, the creamy mouthfeel of the cauliflower purée, and the thick, rich coating of the black curry. Combined, these ingredients offer slightly-sweet, vegetal flavors; tangy, lactic flavors; and powerfully nutty, earthy flavors that coalesce into something… interesting. The combined sensation is certainly pleasant, but it offers no especially memorable expression of either the cauliflower or cheese components. Perhaps the impressive part—other than the presentation itself—is that everything manages to gel together?

An accompanying glass of Camille Giroud’s 2017 Corton-Charlemagne—replete with a youthful concentration of citrus, brown spice, and hazelnut—certainly formed an impressive partnership with that tricky black curry. But you must ask at what point the visual conception of the “Curds” dish imposed upon the treatment of its ingredients as a means to offer pleasure? Still, the visual and textural dimension succeeded, and there is something to be said for putting a novel assemblage of ingredients (featuring regionally-beloved cheese curds) together.

Luckily, the crab and cauliflower courses were followed by one of your very favorite dishes of the entire evening. In fact, you think it ranks as one of the restaurant’s best truffle preparations to date (only surpassed by Alinea 2.0’s truffled French toast and truffle gnudi supplements).

In one of the evening’s most engaging presentations, a server arrived at the table towing an old-school deli slicer. He proceeded to run a halved head of cabbage through the machine’s mechanism, yielding paper-thin slices. These were placed at the bottom of a bowl with a crosshatched green design and then garnished with both mustard and melted Munster cheese. The pièce de resistance came by way of the aforementioned truffles—Périgords sourced from France—that were rather generously shaven so as to obscure all sign of the cabbage altogether. Oh, and did you mention Alinea “3.0’s” opening night fell on St. Patrick’s Day?

The principle dish of cabbage, melted cheese, and truffle was accompanied by a teacup of Russian cabbage soup and a small bowl containing a composition of brussels sprout, bacon, and beet. The course itself was titled “Shave. Smooth. Stack,” which refers to the shaved texture of the cabbage, the smoothness of the soup, and the stacking of the ingredients within the bowl of the brussels sprout (which is related to the cabbage) preparation. The accompanying wine pairing was a 2017 Grand Cru Pinot Gris from Albert Boxler’s vines in the Kirchthal and Steinglitz portions of the Brand vineyard. Alongside the Tyrrell’s Sémillon, the bottle is one of the evening’s most inexpensive. However, its dense mouthfeel—replete with off-dry notes of honey, ginger, and mango—ensures the wine makes a forceful impression.

And “forceful” is fitting, giving the concentration of flavor contained in the principle “Shave” cabbage dish. The vegetable itself, of course, is crunchy, slightly sweet, and mildly earthy with a cleansing piquancy drawn from the mustard component. The Munster cheese—native to Alsace (ah, now the wine pairing makes sense)—contributes a powerfully savory, sharp, and slightly tangy flavor that—due to the cheese’s excellent capacity for melting—blankets every nook and cranny of the cabbage. By the time the shavings of black Périgord show up to the party, the stage could not be better set. The earthiness of the cabbage and funk of the Munster are fitting partners for the same qualities displayed by the truffle. Meanwhile, the crunchy-creamy dichotomy of the cheese-coated cabbage shavings primes the palate for the Périgords’ delicate texture.

The cabbage’s slight sense of sweetness and the sharpness of the mustard prevent the richer, savory components from being overwhelming. As does that Pinot Gris, which manages—by its weight—to amplify the dish’s sublime mouthfeel while, at the same time, refreshing the palate with honeyed fruit flavors that form a perfect counterpoint to the Munster.

Overall, this is the sort of dish that makes truffle tagliolini or truffle risotto seem boring. Those dishes are exercises in cream and butter, attempts to fashion a blank canvas of starch wherein guests taste only the truffle (the sort of tacky technique oft applied to totemic luxury ingredients). The cabbage and the pungent Alsatian cheese offer such a greater amplification of what makes the Périgords taste so striking. Not to mention, texturally, the two ingredients achieve a sticky-crunchy equilibrium that still works to accent the truffle just as well as rice or noodle. From the presentation (with the deli slicer) to the (generous) shaving of the truffles to the ultimate gustatory experience, this cabbage dish ranks as one of Alinea’s boldest and best creations in many years. Bravo!

The other elements of the course—the “Smooth” Russian cabbage soup and the “Stack[ed]” brussels sprout, bacon, and beet—were perfectly pleasant too. The former introduced a sweet-sour essence of the vegetable that acted as a soothing counterpoint to the richer, earthier elements at play on the main plate. It cleansed the palate without altogether shocking it out of its vegetal indulgence. Likewise, the “stacked” brussels sprout formed a perfect vehicle for a burst of pork and the sappy, earthy (but also sweet) character of the beet. In fact, the beet purée reminded you something of a Bloody Mary mix. It, too, refreshed the palate and allowed for a renewed return to the cabbage/Munster/truffle extravagance that, it must be said, ventured well beyond Alinea’s devotion to the “law of diminishing returns.”

All in all, the “Shave” component of the trio could have done without “Smooth” or “Stack.” However, as seen throughout the menu, the additional elements yield an internal logic to the course that makes such an indulgent dish, in the given context, seem somewhat more intelligent. And you bet some diners would have struggled to clean their plate without contrasting notes from the wine or other, appended creations.

The next course—comprising the joint titles of “Scampi” and “Potted”—made use of additional, intricate pieces sourced from Ignite Glass. However, instead of crabs, the vessels (if “Scampi” didn’t already give it away) imitated shrimp (and/or prawns, as it were).

That first dish in the duo of bites featured a plump, bright-red Carabinero prawn reclining across a curved piece of glassware inspired by the carapace of the very same crustacean. The prawn has been carefully shelled, its glistening flesh getting lost in the glow of the dark red glass. Dressing the bite is a mixture of toasted baguette, garlic, butter, and lemon that is then finished with parsley stem and red chili flakes. In a picture posted by Grant Achatz on Instagram, the prawn looks lovingly adorned with all this textural intrigue. The version of the dish which reached your table looked like it had been barely dressed at all.

It possessed what amounted to a buttery glaze but little by way of any crunchy coating. You understand that a given plating can change quite a bit in the week between Achatz’s post and your dinner at Alinea. However, what looked on social media to be a heartfelt rendition of the classic Chicago recipe “Shrimp de Jonghe” amounted to a rather average morsel. (You distinguish “scampi” as a dish defined by garlic, butter, lemon, white wine, and red chili whereas the de Jonghe preparation makes particular use of bread crumbs). All this “good stuff” had been relegated to a small side dish into which the prawn was supposed to have been dunked. (In fact, this “dip” was positioned so far at the end of the table that both you and your guest forgot altogether that it was there).

Whatever the exact recipe at play—scampi or de Jonghe—you would have loved to sample the version pictured before. The Carabinero prawn was tender, its texture was enriched by the butter, and its flavor was helped by a touch of garlic and citrus. Nevertheless, frankly, the bite was boring. It looked better than it ate, and you wonder if showcasing the glass sculpture played a part in transforming the bite from one that arrived fully-composed into one that must be precariously fashioned.

Further, you wonder if the dimensions of the glass sculpture demand that Alinea make special use of the Carabinero, which is known principally for its size, color, and the “robustness” of its flavor. To your palate, there was little noteworthy about the ingredient. Much of its flavor, it seems, is drawn when slurping juices from its head. Perhaps a sauce drawn from that brainy substance could have set things right or, perhaps, serving one of the many smaller, sweeter shrimp cultivated domestically. (Should the size of a species really play a part in its gastronomic merit? There is certainly nothing especially delicious about an oversized steak or chicken breast).

The “Potted” portion of the course came ensconced in a separate sculpture that imitated only the prawn’s head and featured a similar spout as the piece that contained the she-crab soup. That is to say, the sculpture invited guests to pucker their lips around the vessel and suck: in this case, lapping up a mixture labelled as foie gras, clove, and shrimp. You think the dish references potted shrimp, a classic British recipe in which shrimp are seasoned with nutmeg, cayenne pepper, mace, thyme, and such before being set under a layer of clarified butter in the fridge.

Having never tried potted shrimp before, you think foie gras is a clever substitute for the clarified butter, and clove, surely, can take the place of any of the classic herbs. The shrimp, certainly, displayed a depth of sweetness and a fatty character unlike any you had tried before. The foie gras, to that end, lent the preparation the mouthfeel of rich cream. You do not remember loving the dish, but it intrigued you. The flavors undoubtedly—perhaps somewhat surprisingly—worked. And, thinking through it, you can imagine how duck liver might actually reference the intense richness of flavor hidden in the crustacean’s head. Relative to the “Scampi” portion of the duo, the “Potted” presentation felt complete (if more of a diminutive companion bite by comparison).

The accompanying “True Vision” sake produced by Manatsuru (or “Mana 1751”) brewery, despite its low sticker price, actually fit both shrimp preparations rather well. It possessed a bit of earthiness, a bit of roundness, but enough banana and honey to play well with both the garlicky, spicy breadcrumb mixture and the sweet, clove-tinged foie gras. Credit to the wine team for threading the needle between those two extremes with a comparative bargain of a bottle.

The next “Chinese flavor inspired” (in Achatz’s words) course comprised of dishes titled “Ocean” and “Earth.” With regard to the former, the principle ingredient—sturgeon—featured prominently in one of the chef’s Instagram posts. It had been poached and flavored with black sesame, but it was the shape of the fish portions that struck followers as most peculiar. The sturgeon flesh had been processed into to impossibly long slivers with slight, twisting grooves. These pieces approximated thick noodles or long beans in their length and girth, but with the glistening quality of succulent poached fish.

Diners are served a single tendril of this sturgeon, which forms a loop around the appropriately long plate. The fish is partnered by fermented black beans, mussels, seaweeds, and Sichuan peppercorns. The assemblage is quite attractive—truly reminiscent of the ocean—with the many colors and textures of the seaweeds jutting out from gaps between the coil of sturgeon like a coral reef. They are rooted in a purée made from the fermented black beans, which undergirds the entire dish with a salty, bitter characteristic that accentuates the other ingredients. Just where and how the mussels were incorporated (perhaps as pieces nestled in between the sturgeon and obscured by the seaweed) escapes your memory.

What matters most is that sturgeon itself was a textural triumph. It combined the natural umami quality of the fish—imbued with black sesame—with the familiar mouthfeel of an al dente noodle or softened strand of bean. There’s a bit more “chew” than that, perhaps, but pleasantly so. And that quality finds its companion in the seaweed, which is both crisp and gelatinously chewy in turn. The mussels, surely, would have matched the sturgeon’s texture as well—the bivalve is marked by a pleasant plumpness and slight firmness that echoes the fish’s flesh. The mild numbing effect of the Sichuan peppercorn works beautifully to enhance such an array of toothsome elements.

All in all, “Ocean” impressed you as a dish. It was anchored by an extravagant preparation of fish that—while it took a novel form—delivered a concentrated flavor and textural experience. Molecular gastronomy techniques are not being used to torture the ingredient or deny its most pleasing or nostalgic essence. (You must mention, once more, the disappointing dehydrated langoustine paper served with Alinea 2.0’s bouillabaisse). Rather, the techniques are used to refine the fish’s form in such a way that it may reference other foodstuffs—composing a dish with layered meaning—while retaining a sense of its character as it is eaten.

The “Earth” portion of the course was a bit more simple. It comprised of a shiitake mushroom and sausage fritter seasoned with Chinese five spice. You are not exactly sure what form this bite is referencing, but the texture was crisp, flaky, and delicate. The overall flavor was unmistakably (perhaps even straightforwardly) savory. You might have even liked to see a greater concentration of flavor. But the dish delivered a tidy morsel from which to derive satisfaction opposite bolder flavors of the fish.

The accompanying pairing of Jean Foillard’s Morgon “Cuvée 3.14” Gamay delivered an exceptional concentration of cherry flavor balanced by high acidity and enough of an earthy, sour character to play well with the fermented black bean (and, thus, the sturgeon itself). You think it was a savvy choice to serve a top quality Cru Beaujolais—expressing itself beautifully—rather than endeavor to fit in a merely “good” Burgundian wine. Truth be told, the Morgon’s “natural” qualities—a combination of energy and rusticity—might provide an essential element of balance when pairing it with “Ocean.”

Moving onto the evening’s next course, the Chinese-inspired shiitake and sausage fritter segued perfectly into a Mexican-inspired duo of bites defined by an even more estimable member of the mushroom kingdom.

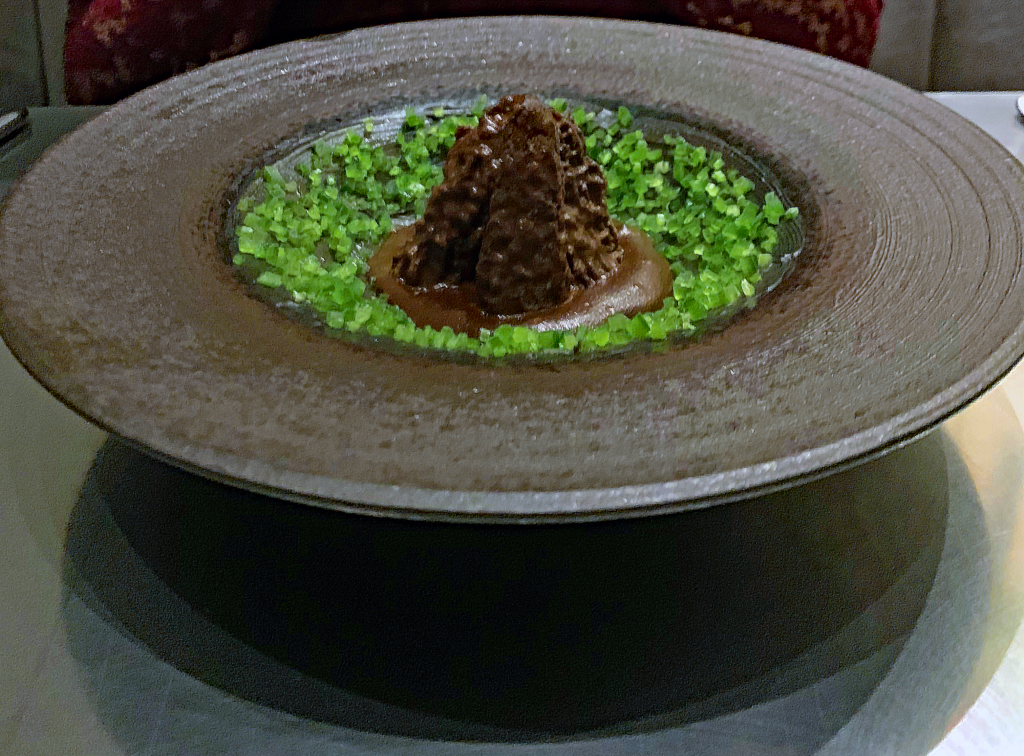

“Morchel” was the title of the first, principle dish in the sequence. The word is the German spelling of the genus Morchella, which comprises several varieties of “true” morel mushrooms that rank among the most prized of all fungi. Part of that reputation has to do with the difficulty involved in cultivating the ingredient. They can be grown in a controlled environment with some effort, but the vast majority of morels must be foraged in the wild (with Michigan’s century-old National Morel Mushroom Festival and the Illinois State Morel Mushroom Hunting Championship both signaling the abundance with which the mushrooms can be found in the Midwest).

Of course, these morels are not hunted down merely because they are rare. The mushrooms—possessing distinctive caps defined by a signature honeycomb design—rank as one of the most striking totemic luxury ingredients in purely visual terms. More importantly, they taste absolutely delicious, marked by a profoundly meaty texture and deeply earthy, quite nutty characteristics to boot. Morels possess a greater flavor concentration than the equally beloved chanterelle mushrooms. And the eating experience they offer is more toothsome and satisfying than the delicacy and aromatic qualities offered by that old chestnut the truffle.

For the “Morchel” dish, Alinea situated a veritably mountainous morel at the center of a shallow bowl. (In truth, it may have been a couple large pieces of cap arranged together so that their points formed a perfect peak—such was the size of the fungus). Beneath this tremendous mushroom sat a shimmering brown mole sauce of a shade that nearly matched the color of the morel itself. Surrounding the sauce—and coating the sides of the shallow bowl all the way up to its rim—was an emerald green layer of finely diced ramps. Also known as wild leeks or spring onions, ramps—like morels—must be foraged in the wild. They appear for a short period at the beginning of spring, during which their combination of garlicky and oniony flavors makes them a favorite ingredient of just about any cook who can get their hands on them.

Foraged morels, foraged ramps, and a pleasurably thick, smooth mole: welcome to umami heaven. “Morchel” ranks as one of Alinea’s most unapologetically savory creations in recent memory. It strikes the palate with the sort of power and concentration you have long craved at the restaurant. The mountain of morel—the gaps in its signature ridges glazed by the Mexican-inspired sauce—captures the mouthfeel of the most succulent offal. That is to say, the mushroom offers all the textural intrigue of tripe or sweetbreads with an unerring tenderness that would be nearly impossible to achieve with organ meat.

In terms of flavor, the morel’s inherent earthy, nutty qualities come to the fore, but they are unleashed by the mole so that they achieve an uncommon intensity. You are not sure exactly what the mole is made from, but the presence of nuts, seeds, chocolate, and a variety of chiles is almost assured. What is most important is that the assemblage never overshadows the flavor of the mushroom. Rather, it forms the supporting euphony of flavors from which the morel’s essence can shine through complement and contrast. Meanwhile, the diced bits of ramp provide a pleasing crunch and cleansing burst of allium to cut the dish’s richness. With regards to the mushroom or Mexican-inspired preparations Alinea has served in the past, “Morchel” is undoubtedly the best of the bunch.

In a manner reminiscent of the evenings prior courses—where a larger plate or bowl would be paired with one or two smaller accompanying portions—the morel preparation was accompanied by a dish titled “Nopal.” That word, of course, refers to cacti—both the plant itself as well as its edible pads. In English, the genus is commonly called “prickly pear,” which Alinea lists as the dish’s primary ingredient alongside succulents and hoja santa.

This trio is presented in a serving piece that resembles the prickly pear’s fruit—essentially a hollow, miniature pineapple that is here rendered in a shade of cactus green. The ingredients stand upright at the bottom of the sculpture, partially obscured by the opaqueness of the glass. It’s a bit like a mini terrarium, a showcase of leaves, herbs, and flowers that guests inevitably trample with their spoons and shovel down their gullets.

Graphic imagery aside, “Nopal” is a refreshing companion to “Morchel” that works to relieve the palate from the latter dish’s richness. The prickly pear is tart and sweet, the succulents mildly peppery and bitter, and the hoja santa combines flavors of both pepper and anise. The portion, all things considered, is rather small; however, “Nopal” effectively cleanses the palate while also exposing guests to the surprising qualities of these cactal components. Served in the shadow of such a satisfying mushroom preparation, this diminutive member of the Mexican-inspired duo of dishes comported itself finely.

And the wine pairing, too, really doubled down on how great this course was. The 2006 Amarone della Valpolicella “Monte Lodoletta” produced by Romano Dal Forno was all lush dark fruit, mocha, dark chocolate, and licorice. It displayed a tremendous presence on the palate but possessed ample acidity and ripeness to leave an impression of freshness. It is no surprise that such an Amarone stood up to the morel’s intensely earthy character, but you also cannot imagine a better match for the “Morchel” dish’s mole sauce. And yet, the Dal Forno possessed enough of a sweet herbal characteristic to match the ramps and the cactus as well. What a stunning wine and a real cherry on top of this segment of the meal. Bravo!

Next came the bread course. It’s one of your very favorite parts of any meal, especially in the realm of fine dining. While establishments such as Le Bernardin, Eleven Madison Park, Per Se, Daniel, Gramercy Tavern, and Bouley have distinguished themselves by offering you a superlative selection of baked goods over the years, Alinea has typically ignored this fundamental pleasure. Truth be told, Chicago’s gourmet restaurants—especially after the demise of L2O, RIA, Tru, and—most recently—the closure of Everest—have largely shirked the traditional tableside bread basket.

Yes, in some sense, the notion of offering five, six, seven, or up to twelve different loaves made from various grains and fillings is an unabashedly Francophilic touch. In an age of gluten aversion and decreasing specialization within the classic brigade system, restaurants can be forgiven for neglecting to bring a master baker on board. It is hard enough to find a pastry chef worth their salt (or is it “worth their sugar”?), let alone one who might be entrusted to shape the sweet side of the menu and to put out a memorable, savory baked creation. In truth, many of Chicago’s fine dining desserts desperately play things safe in a bid to please nonplussed guests. There is no reason why the creation of a bread course—that one reprieve from any polarizing portion of the tasting menu—would be approached any differently.

Chicago’s best bread courses, at present, must be Smyth’s excellent brioche donut and the rotating duo of loaves offered by Spiaggia. The former bends a pastry form into the ultimate vehicle for beef fat and jus while the latter stands as an ode to rusticity—particularly when paired with olive oil, lemon ricotta, or even shaved truffle. Discounting fine dining, you must give kudos to the crusty (yet internally light and fluffy) loaves on offer at Bavette’s, Bungalow by Middlebrow, and Publican Quality Meats (helmed by Greg Wade, who might be just about the best bread baker in the country). Aya Pastry also merits mention—and even Alinea has made use of her bread before—but you think those loaves are not quite as good as Aya’s cakes and other desserts, of which she is Chicago’s foremost expert.

When it comes to Alinea’s attempt at a bread course, it is rather telling that the restaurant lists the bread—“rye bread”—as the last ingredient of four. Taking center stage, instead, is “Le Bordier,” the title of the dish and a reference to Jean-Yves Bordier’s Le Beurre Bordier. These eponymous butters—made without preservatives and using 19th century methods—have gained a reputation as the world’s best. The dairy is sourced from “local small farmers who use the best farming practices” before being transformed into a range of colorful flavors that includes seaweed butter, Roscoff onion butter, yuzu butter, buckwheat butter, and even raspberry butter. Bordier approaches butter making with the soul of a fromager, and his products have been featured by Joël Robuchon and Alain Passard at their restaurants.

Limited amounts of Le Bordier butter were stocked last year by local establishments like Lost Larson (a bakery whose breads, you must say, also deserve an honorable mention) and Rare Tea Cellar (a longstanding purveyor to the city finest restaurants). Given that the Saveur article cited above was published in 2018, two years seems like the right amount of time for this new totemic luxury ingredient to trickle down to the Midwest.

For its bread course, Alinea sculpts the Le Bordier butter into a ribbed conic shape, the base of which has been filled with osetra caviar. In the original version of the dish (posted by Achatz on social media), a second cone made from radish stood alongside that made from the butter. In the version of the dish served to you, small circles of radish and chive simply ornamented the original caviar-filled tower.

When the course is served, a bundled tuft of wheat first arrives at the table. Two individual strands of the grass sit on top of the bundle, each one skewering a small nugget of raw rye sourdough that guests are meant to enjoy before attacking their plate. The plate contains the aforementioned cone of Le Bordier—decorated with the bits of radish and containing that hidden filling of caviar—and the same rye sourdough that has been baked into small, circular roll.