The closure of Elizabeth after 10 years of operation (nine of those during which it held one Michelin star) was a bitter pill to swallow. Iliana Regan’s “new gatherer cuisine” tasting menu concept in Lincoln Square—later stewarded by owner Tim Lacey and executive chef Ian Jones during its final, post-pandemic chapter—always formed one of the most challenging meals in the city. No other restaurant pursued its vision so doggedly, so seemingly unconcerned with conventional conceptions of pleasure, but so frequently achieved memorable results.

Yes, eating at Elizabeth usually felt thought-provoking more than it did satisfying, but the food never rubbed you the wrong way like Alinea’s. Regan’s cooking was just so earnest, so quietly confident, and so starkly evocative of the natural world. It was not the product of a bunch of fart huffing nerds turning their technology toward ever more tortured compositions of style over substance. Rather, her menus always privileged a sense of purity that placed raw (or carefully preserved) ingredients at the forefront of each plate and, through conscientious accompaniments, allowed them to sing. You had never tasted vegetables, fruits, grains, and flowers presented in such a way before, and Regan ensured the more decadent fare (meat, seafood, pasta, sourdough, and otherworldly foie gras mousse), when it did appear, demanded the same careful consideration.

Elizabeth, as Smyth would later do, reflected that rare kind of fine dining that did not concern itself with appealing to the lowest common denominator. The restaurant did not work backwards calculating how it could most efficiently marshal its resources toward delighting the greatest number of palates or orchestrating the most unforgettable show. It dove headfirst into its chosen genre—its obsession—and never looked back. Thus, it was the first place where you really came to understand what it means to trust a chef: not in the sense that what they served you would always be conventionally “good” but, instead, that it would be true. Trusting Regan meant embarking, hand in hand, on a journey of discovery. It meant empowering a process through which the expression of the season always took precedence. It meant learning—slowly—to cherish natural products that had never merited a second look before. It meant, frankly, ingesting some food that was too green, funky, or bitter compared to what you were used to (let alone at premium prices). Yet the dishes were always singular, and, bit by bit, they worked to reveal a wider vision of cuisine that totally redefined what you considered palatable (let alone prized) in service of a creative instinct you can only term sublime.

Of course, it was easy to get distracted by the many pop culture-themed menus Regan put on with her wife Anna Hamlin: Alice in Wonderland, Chronicles of Narnia, Downton Abbey, Dr. Seuss, Game of Thrones, Harry Potter, Lord of the Rings, Nintendo, Star Wars, Stranger Things, Wes Anderson, and the like. But these media properties only served as window dressing—a jumping off point—for food that was totally uncompromising in its fidelity to the chef’s inimitable style. You came expecting a good dose of whimsy (and received it via homespun decorations, colorful drinks, and clever references) but still ate the same challenging “new gatherer cuisine” Regan was known for.

It was through these themes that the chef ingeniously demarcated the many small segments of the season: spans of just a few weeks (reminiscent, on much a broader scale, of the 72 micro-seasons observed in Japan) that would be far harder to brand and sell to the public via conventional means. To this day, most aspirational fine diners are led astray by the impulse to “catch them all” and visit every one of Bibendum’s starred recommendations. They miss the fact that a small stratum of restaurants, pursuing processes of perpetual growth, craft dynamic menus that reward repeat visits from month to month (or even week to week!). These diners chase a steady stream of novelty rather than resolving to support places with overflowing creativity and exceptional hospitality more consistently. In doing so, they privilege their own conspicuous consumptive lifestyle (as concocted through social media) rather than engaging deeply with the kind of artistry that transforms mere food into something transcendent.

Regan found a way to galvanize diners without ever needing to spell out why her style of cookery was so well-suited to repeat patronage. It also certainly helped that Elizabeth, in its time, was just about the cheapest Michelin-starred tasting menu in town (with tickets being priced as low as $50 on weekdays). But Regan’s goal was never to exploit that status for the sake of commercial success. Instead, she was the best kind of evangelist: one who humbly shared her passion with as many people as she could without ever diluting its power. She remains, for you, one of Chicago’s greatest chefs ever: a craftswoman who revived the city’s great “prairie cuisine” tradition and, without any hint of pretense, revealed its kindred connection to the New Nordic movement that has come to dominate global gastronomy.

Looking back, Elizabeth still seems far ahead of its time (and stands distinctly apart from anything offered in the city today). Nowhere, save for Smyth (and maybe Lula Café), devotes itself quite as strongly to the rhythms of the season. And few chefs, even with a surging population of young, adventurous diners to cook for today, approach their craft as unapologetically. But Regan—now a New York Times bestselling author—has deservedly ridden off into the sunset: running The Milk Weed Inn with her wife in Michigan’s Upper Peninsula. This new setting, surely, intertwines her even more intimately with the natural world her work always sought to express while allowing for a kind of total experiential hospitality that has few peers worldwide. Regan’s cuisine, to judge it by a recent pop-up, has never been better, and it is hard to think of any more graceful an exit from an industry that hardly ever allows talented chefs to just step away.

Ian Jones’s era as executive chef—spanning a period from August of 2021 through the restaurant’s closing in December of 2022—was certainly successful at a creative level. Regan had been planning her departure from Elizabeth “as far back as November or December [of] 2019” but stayed on through the pandemic. She formally sold the restaurant to Tim Lacey—whom she originally worked with at Trio and who later ran her Japanese-inspired concept Kitsune—in August of 2020. However, the two would not divulge that information for more than a year so that the concept could regain its balance before charting a new course.

Jones, who had also worked at Kitsune (as chef de cuisine) and could count prior experience at Band of Bohemia, Sepia, and Bavette’s too, took over as executive chef of Elizabeth when it was still doing takeout. Regan trusted him with “executing her vision,” and the team would grow to include pastry chef/chef de cuisine George Kovach (of Ever, Acadia, and Band of Bohemia) and beverage director Ali Martin (of Blackbird). Jones would preserve the restaurant’s original “hyper-seasonal” ethos with “gradual changes [to the menu] every day” and full rotations “every six to eight weeks.” Regan herself would eat there on (re)opening night and term the meal “incredible.”

You only made one sole visit to this new iteration of Elizabeth in November of 2021; however, it left you impressed. Jones’s menu included courses like “Pumpkin” (stuffed with osetra caviar, mango, and grains), “Japanese Sweet Potato” (with matsutake mushroom, quince, and koji), “Sunchoke” (with coffee, shiitake, and smoked duck), a savory “Mont Blanc” (with fennel, chestnut, and “porkoboshi”), “Iberico Secreto” (with apple and cabbage), a “Chopped Cheese” sandwich (made with A5 wagyu and Swiss Chällerhocker), and “Beef Tongue” (with husk cherry, huitlacoche, and nori). Kovach’s desserts included a play on the Nestlé “Drumstick” (with white truffle, brown butter, white chocolate, and rainbow sprinkles), “Paw Paw” (with white chocolate, pepita, and maple), and “Parsnip” (with Anjou pear, wild licorice, and vanilla). Meanwhile, two sets of snacks—“Porchetta di Testa” (with blackberry and hoisin) and “Delicata” (with kombu and maguey) on the savory side then a “Tart” (with black sesame, milk tea, and cacao) and “Pâte de Fruit” (with magnolia oolong and lavender sugar) on the sweet side—would bookend the meal.

Presented on beds of hay or algae (along with slabs of wood and shadow boxes filled with gourds), these dishes were clearly spiritual successors of the intricate, beautiful compositions for which Regan was known. The bites were ruggedly naturalistic—beautiful in their imperfectly flowing strokes of color—but still made with finesse and a good dose of nostalgia. Jones’s style even seemed just a bit more generous than that of his predecessor. Luxurious meats like the ibérico secreto and wagyu took center stage alongside servings of porchetta di testa, smoked duck, and beef tongue throughout the meal. Flavor combinations were still inventive but aimed more firmly at a satisfying sense of umami than the bitter, floral, and roasted notes Regan often allowed to shine. An excellent sourdough was still offered too.

Elizabeth, reborn under Lacey and Jones, struck you as a success. Bibendum would agree when declaring, in April of 2022, that the restaurant had retained its Michelin star (no mean feat when enduring a change of chef). You regret not visiting this iteration of the concept more often, for it certainly merited an extensive review. Yet Elizabeth’s location, rather removed from downtown Chicago, had always been a sticking point: there was no other local restaurant you traveled farther to experience (save for rare jaunts to George Trois), and the combination of challenging cuisine with a distant neighborhood did not always prove appealing. (Honestly, it is a huge testament to Regan that you braved the trip dozens of times.)

By late November, it became clear that Elizabeth—the concept originally named for Regan’s late sister—would be no more. Jones was departing to work at three-Michelin-starred Quince (also a “Green Star” winner) in San Francisco. Lacey, as owner of the space, planned a reset: making “a few minor cosmetic changes to the interior” and interviewing executive chef candidates for a new “tasting-menu restaurant” titled Atelier. The name would be a callback to his time as bartender at Trio Atelier in Evanston (once home to chefs like Regan and Grant Achatz). It would represent a “clean break” and a chance to tell a new story rather than cling to one whose time—after a decade of achievement—had clearly passed.

Through December and the first couple weeks of 2023, Lacey would keep his cards close to his vest. However, on January 18th, he was ready to announce whom he had chosen to be Atelier’s chef.

Christian Hunter was born in Lexington, Kentucky as the middle of seven kids. He credits “fresh vegetables from his grandad’s garden” and “his mother’s cooking prowess” with making him fall in love with food— “I would see, smell, or look at something then immediately want to imitate it.” He also notes that his mother, as a single parent, “showed him not only how to make humble ingredients shine, but also how to have a strong work ethic.” That latter quality would be tested at age 11, when Hunter entered a three-year scholarship program with the hope of “easing the financial burden” on his family while also “broaden[ing] his horizons.” He “worked hard in his studies, stayed out of trouble, and tested well,” earning the opportunity to attend Baylor School in Chattanooga, Tennessee. There, he developed “the fundamental yearning of discovery” but “nothing grasped his full attention as much as food.” Hunter began “to cook in the dorms and on the weekends at his friends’ houses,” exploring different flavors and spices “from faraway lands.” This “fueled his hunger for more food knowledge” and, by graduation time, he “knew he didn’t want to continue on the traditional academic path.”

Without “ever visiting or attending a single orientation,” Hunter enrolled in the Culinary Arts and Service Management program at Paul Smith’s College in Upstate New York’s picturesque Adirondack Park—realizing that “he had inadvertently spent his entire life preparing himself for culinary school.” Moving there was a “culture shock” (especially “when it began to snow”), but he quickly fell in love with the area’s “abundance of root vegetables and mushrooms” that were utilized in his classes. Upon graduating, he took his first job as a line cook at the nearby Lake Placid Lodge: a five-star Relais & Chateaux property known for “excellent farm-to-table cuisine” crafted from ingredients sourced in its “own backyard.” After a little more than a year there, Hunter would venture south toward the Catskill Mountains, joining Glenmere Mansion (another five-star Relais & Chateaux property) as sous chef. There, at what is termed “a little slice of Tuscany in the Hudson Valley,” he would once again work with “the freshest produce from local farms and markets out…[the restaurant’s] back door” as well as ingredients drawn from “the best international markets in New York City just minutes away.”

After working there, once more, for a little more than a year, Hunter made his way to Manhattan. He joined FiDi’s Le District—a sprawling French food hall with markets, a bistro, and, later, a Michelin-starred restaurant named L’Appart—as sous chef but left after four months. Perhaps finding the big city setting (especially around those parts) stifling, Hunter decamped for Rhode Island’s Weekapaug Inn. The four-star Relais & Chateaux property “caressed by the Atlantic breeze” allowed the sous chef, once more, to work with “local growers, farmers, and fishmongers” and express the “micro seasons of coastal New England” using ingredients “at peak freshness.” Hunter would stay there for a year and a half before taking a job as the executive sous chef of The Restoration, a four-star boutique hotel in Charleston, South Carolina. Though not, in this case, a Relais & Chateaux property, the venue would offer him a chance to “challenge himself” outside of finer dining while cultivating “his own culinary identity.” With time, he would realize that “working locally with farmers” was his “calling” and that “a vegetable forward emphasis with a nod to global flavors” formed a personal style through which he could utilize the local bounty.

After nearly a year at The Restoration, Hunter would take the most consequential step of his career yet by joining Sorghum & Salt as its chef de cuisine. The 40-seat Charleston restaurant had opened a year earlier (in 2017) and represented something of a homecoming for chef-owner Tres Jackson, a Carolina native who had spent the past 13 years cooking in Alabama. The concept’s ethos had always been “vegetable-forward with plenty of small plates” utilizing “the bounty of the surrounding farms, seas, and fauna,” making it a perfect for the young chef’s burgeoning style.

Archival menus from Hunter’s time at Sorghum & Salt reveal the kind of creativity this job empowered. The “Dim Sum (Kind of)” section featured bites like “Charleston Brown Bread” (with Anson Mills farro and apple butter), “Crispy Okra” (with Clemson blue cheese, plum, yogurt, and benne), “Roasted Vegetable Wontons” (with cabbage soubise, chili oil, and sesame), “Braised Yellow Beets” (with tarragon, Meyer lemon, chili, and pistachio gremolata), “Steamed Buns” (with lamb, dried fruit salsa verde, and harissa yogurt), “Collards” (with parmesan, bean paste, and chili), “Sweet Potatoes” (with black garlic, herbed yogurt, feta, and apricot), “George Flame Relleno” (with ranchero sauce, corn, feta, and salsa verde), “Butter Beans” (with roasted garlic, dried egg yolk, and black pepper), and “Preserved Summer Squash” (with toasted housemade brioche, oregano, capers, and roasted garlic).

The ”Small-ish Plates” section featured items like “Hoppin John” (with pickled pea and spring onion salad), “Spicy Marinated Cauliflower” (with pickled tomatoes, pickled corn, carrot cardamom purée, and chili oil), “Root Vegetable ‘Trotter’” (with pine nut purée, strawberry, and spring onion), “Kale Caesar” (with parmesan custard and miso powder), “Rutabaga ‘Tagliatelle’” (with Meyer lemon, bagna cauda, and almonds), “Miso Glazed Rainbow Carrots” (with whipped ricotta, pink peppercorn, and honey), “Potato Salad” (with quail egg, black garlic, and candied salmon), “Gnocchi” (with tofu, blistered shishito cream, and brioche crumbs), “Roasted Butterkin Squash” (with harissa, yuzu buttermilk vinaigrette, and pumpkin seed), “Fried Quail” (with jalapeño jam, gribiche, and parmesan), and a “Six Minute Egg” (with sunchoke, oyster mushrooms, and caviar).

Lastly, the “Large Format” section featured dishes like “Seared Sea Scallops” (with corn velouté and preserved mushrooms), “Snapper” (with walnut butter and roasted cauliflower), “Seared Halibut” (with field pea ragu, black cherry tomatoes, and corn-miso vinaigrette), “Spaghetti” (with lamb bacon and goat cheese), “Eggplant Meatloaf” (with tomato vinaigrette and squash conserva), “Heritage Pork Steak” (with spicy pickled cauliflower and black garlic), and “Spiced Lamb” (with fermented honey and apple-fennel chutney).

Frankly, the degree to which Sorghum & Salt’s menu changed from month to month (and even week to week) is pretty stunning. You also particularly like how many of the vegetable-focused dishes do not shy away from intensity of flavor (via accompanying ingredients like black garlic, dried egg yolk, and chili alongside various cheeses, vinaigrettes, preserves, pickles, and salsas). Despite that, The Post and Courier would saddle the restaurant with a two-star (out of five) review in May of 2017 and, once more, in March of 2019 citing the kitchen’s penchant for “needlessly piling on flavors” that (in the later review) “now wouldn’t impress even if presented in isolation.” The author, at least, would admit that Sorghum & Salt is “consistently exalted” by the public (via Yelp and Google) “for its creativity, innovation and mad scientist streak.” And you, naturally, must question how well any newspaper “critic” can adequately evaluate such a dynamic concept when constrained by time, funds, and those pesky word limits.

For any young chef, such a concept—whether each dish is ultimately successful or not—offers a rare opportunity to pursue a creative process that forbids nothing. Learning to edit one’s more harebrained inclinations, no doubt, is an important mark of wisdom. But getting to play in such a sandbox while utilizing the best of local ingredients seems like the surest way to really get a handle on—and refine—one’s personal style. You can even note one or two preparations from Sorghum & Salt that seem to inform Hunter’s later creations at Atelier!

The chef’s time at the restaurant—a period of nearly two years—would nonetheless end on a sour note. Ahead of New Year’s Eve service in 2019, Hunter’s sous chef arrived at Sorghum & Salt to find it “unlocked and in ‘unsightly’ condition.” The gory details were spared except to say “bodily fluids” were involved, and Jackson (the chef-owner) was identified as “the last to leave the building” the night before. This formed the “last straw” for Hunter and led him to resign, explaining “he no longer felt obliged to prop up a restaurant owned by ‘someone … who doesn’t respect our craft, our effort and genuine love for the business.’” Front of house manager Joe Vidal and sous chef Alan Burgmayer would also quit out of solidarity (the former stating “Christian was the linchpin. Christian is a fantastic chef, and I would work anywhere he wants to be”), but the trio would stay on and complete New Year’s Eve service out of loyalty.

Underlying the level of disrespect shown by the soiled kitchen was a deeper philosophical problem—namely, that Jackson “didn’t always honor the culinary philosophies which the restaurant promoted.” Hunter pinpointed a signature “Beet Crémeux” dessert that, “because beets aren’t in season year-round…has got to disappear” from the menu at some point. Nonetheless, it never ceased being offered, and the chef affirmed “if we’re going to be farm-to-table, I want to be legit about it. That’s important to me.” A dish of “cucumber and crab” that Jackson sought to add to the New Year’s Eve menu also drew protests, with Burgmayer explaining “we could not be sure the crab was coming from Charleston…. It was in conflict with what we wanted to do in promoting local foods.”

This philosophical divergence undermined a professional relationship that was already strained. Hunter “didn’t think Sorghum & Salt would ever make him rich or famous, particularly since he was earning $9 an hour when he quit” (though also collecting tips “under a scheme which required all employees to handle both dining room and kitchen duties”). But the chef “was disappointed that he and his co-workers weren’t credited publicly for their contributions to the restaurant’s financial stability and growing popularity.” Hunter would even argue that “most of the things on the menu were mine and…[Jackson] takes credit,” something the owner could get away with because he doesn’t “look like your typical downtown Charleston chef.”

Ultimately, Hunter “cared about…making the business viable and using hyperlocal products” but “didn’t feel he could achieve his goals so long as he and Jackson didn’t share the same set of values.” The Sorghum & Salt owner would offer a partial, if unconvincing, rebuttal to the allegations a couple days later, but this chapter of the chef’s career had clearly come to a close.

The dawn of the pandemic in early 2020 would complicate Hunter’s next step. However, that May, he was invited to become the chef of Community Table in New Preston, Connecticut. Managing partner Jo-Ann Makovitzky “knew that CT needed an energetic, sophisticated chef to lead the kitchen team into our future” and found that Hunter “was easy to get along with” and shared “the same views and philosophies about food, restaurants, and how growth and change occurs.”

The chef would describe the period following his arrival as “incredibly challenging,” having “to change the dynamic of the restaurant and switch to doing take-out meals and outdoor dining, which was totally new for CT.” However, thanks to the restaurant’s regulars and an “excellent” team, the kitchen stayed busy during an otherwise quiet—if not disastrous—era for restaurants.

By August of 2021, Hunter had hit his stride at Community Table and could expand on what was now a fully formed vision. He would describe “the explosion of small organic farms in the area” as “one of the most exciting things about cooking” there. These allow for “everything” done at CT to be “seasonal” and ensures that “almost all” their ingredients are “locally sourced.” The chef would describe working with farmers as “an intimate thing” and cited “getting to know them and their culture” as informing how he feels about the food he makes. Moreover, Hunter would explain that “the great advantage of working seasonally” is “not only…getting the freshest ingredients” but being empowered to “continually innovate with the menu and provide his guests with an exciting variety of new dishes.” He would observe that “people don’t want the same thing all the time. They want an experience that will give them a memory.”

More specifically, “exploring and juxtaposing global flavor profiles” would be described as “key” to Hunter’s cooking. The chef “takes what at first glance might appear to be your standard New American fare but gives it an extra zing by adding unexpected ingredients or spices.” His “grilled marinated quail,” for example, “comes with asparagus, white beans, and mushrooms, but he punches it up with chermoula, a traditional North African cumin-based marinade.” His “roasted rack of lamb,” likewise, “is served with freekeh, a North African barley.” He also “draws on tastes from South America, such as piquillo peppers, which are a key component of his slow-poached monkfish,” as well as “sourcing bourbon from Litchfield Distillery for his New England seafood chowder.”

Ultimately, Hunter would affirm that he wants “every plate” he makes “to tell a story” and to make people “sit back and say ‘Wow. This is the best thing I’ve ever eaten.’” His ambition, furthermore, was clear: “I want to win a James Beard Award.”

One representative menu from November of 2021 lists dishes like “Smoked Salmon Dip” (with lemon aioli and caper-olive salsa verde), “Crispy Sweet Potato Wedges” (with beet ketchup, whipped feta, and barbecue spice), “Caesar Salad” (with shaved radish, cucumbers, and anchovy), “Lump Crab Wontons” (with cream cheese, black vinegar, and ginger aioli), “Striped Bass Crudo” (with squash aguachile, shrimp oil, and clam escabeche), “Burgundy Truffle Cacio e Pepe” (with duxelles), “Mahi Mahi” (with butternut squash chowder and bacon lardon), “Pan Seared Diver Sea Scallops” (with squid ink risotto, black rice grits, and Espelette aioli), “Pan Roasted Pheasant Breast” (with cannellini beans, kale, and charred carrot coulis), “Slow Roasted Berkshire Pork Chop” (with garlicky local greens, potato salad, and squash purée), and “Roasted Hen of the Woods” (with braised chickpeas, za’atar, and zhug).

Another menu, from October of 2022, lists items like “Sourdough Pumpernickel Rolls” (with rosemary olive oil and miso-maple butter), “French Onion Spread” (with Greek yogurt and crispy shallots), “Roasted Carrots & Parsnips” (with whipped ricotta, smoked local honey, and salsa macha), “Roasted Stratford Point Oyster” (with crispy potatoes, Calabrian chile butter, and local miso), “Hudson Valley Steelhead Trout” (with braised beluga lentils, smoked trout roe, and sauce Dugléré), “Seared Atlantic Scallops” (with forage mushroom risotto, yuzu, and togarashi), “Maple Lacquered Duck Breast” (with toasted fregola pilaf, apricot purée, and tagine sauce), “Double Cut Ribeye for 2” (with truffle parmesan tostones, garlicky kale, and Bordelaise), and “Braised Winter Fennel” (with tomato sugo, sunflower-pine nut risotto, and Arborio water).

While you wish you had more menus to draw on (and judge just how quickly new dishes appeared and old ones retired), Hunter’s time at Sorghum & Salt clearly demonstrated his capacity to changes things constantly. There is every reason to believe he did so to the same (or an even greater) degree at Community Table, and you are also heartened to see his food paired with wines from producers like Arlaud, Ar.Pe.Pe, Azelia, Beaux Frères, Bollinger, Clerget, Dönnhoff, Giacosa, Gimonnet, Kongsgaard, Krug, L’Arlot, Lafon, Laurent Perrier, Marguet, Nanclares, Palmer, Penfolds, Peter Michael, Racines, Roagna, Thibaud Boudigon, Turley, and Vietti.

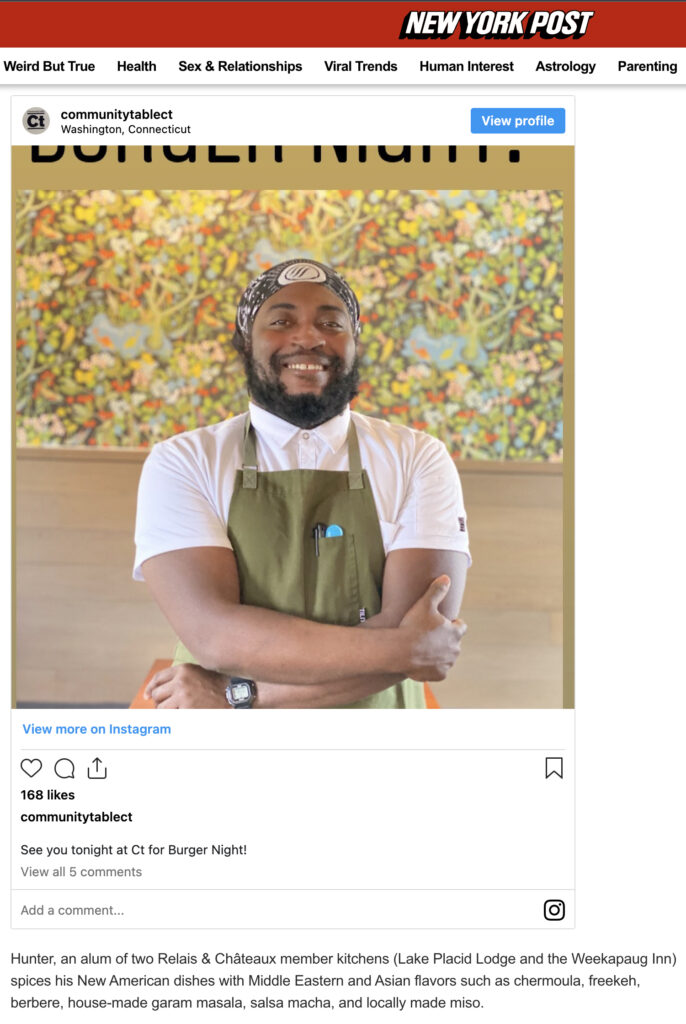

Ultimately, Hunter’s work at Community Table would earn him a mention in the New York Post, which referenced how the chef “spices his New American dishes with Middle Eastern and Asian flavors such as chermoula, freekeh, berbere, house-made garam masala, salsa macha, and locally made miso.” Prophetically, he would not only be named a James Beard Awards semifinalist for Best Chef: Northeast (CT, MA, ME, NH, RI, VT) in January of 2023 but make the list of finalists at the end of March. Of course, by then, he had already started cooking in Chicago, transferring this incredible acclaim to his new home Atelier.

Lacey’s success in luring this rising star—only days away from receiving national affirmation of his talent—to the Windy City seems uncanny, but Hunter—in truth—hesitated to respond to the Atelier owner’s job listing “because he thought his lack of credentials in high-profile restaurants would disqualify him.” Nonetheless, the chef was attracted by the prospect of having a “blank canvas” within a “landmark space” that “has made some really good food.” He was conscious of what Regan had accomplished at Elizabeth and recognized “there’s a lot of pressure behind that.” “I was definitely aware of Chef Regan, but I was not aware until getting more background information how badass chef was,” Hunter said. “Let’s be very, very honest: Iliana’s a great chef, and Ian’s a great chef as well. It’s a hell of a one-two punch to follow up.” Nonetheless, he viewed this next step as a “natural evolution.” “Not to say anything bad about my previous employer, but I know that my time is up there….I really enjoyed almost three years there, but when the Atelier job showed up, it seemed like a perfect job for me.”

Atelier’s owner would reveal that he “didn’t have any sort of style or aesthetic in mind” when searching for a chef. “If it wound up being classical French, great, if it wound up being, I don’t know, this Bosnian-Basque mash-up, great,” he said, so long as it was somebody whom he “could get excited about and get behind and support to do what they love, what they’re good at.” This kind of philosophy connected to the restaurant’s namesake, the aforementioned Trio Atelier in Evanston where owner Henry Adaniya “was finding people whose time it was and giving people the opportunity and the space to do what it was that they were passionate about and good at.” Lacey “really liked” where Hunter’s “head was at with what he was trying to do with his food” and, upon conducting a tasting, found his flavors to be “just really tight and complex without being overwhelming.” The owner, as Adaniya had done, felt it was time for the chef to have “the opportunity to do what he was excited about….to have that shot.” Most of Elizabeth’s staff would be staying on to help him fulfill that potential.

Stylistically, it was clear that Hunter’s “priorities matched some of Regan’s.” Namely, as the earlier chapters of his career demonstrate, he is “really focused on utilizing local products, but trying to be inventive and creative with [them].” Despite that experience, the chef described himself as coming in “from a place of respect and humbleness” because Chicago is not is hometown. Still, he would “try to represent it and use the local food and really try to become part of that community”—the goal being “to push the food” the way he wants to, “which is supporting local, but having really cool, awesome flavors to go with that.” That would include celebrating “the different nationalities and flavors and everything that makes a place a place” including his community and himself.

Upon accepting Lacey’s job offer, the “first thing” Hunter did was to “start talking about vendors and looking up previous vendors that the restaurant was already using, reaching out and just starting to look at distribution lists and availability in the area” so he could get “a head start on building a menu.” That “tentative initial menu” would start “with a selection of local beer and cheeses served alongside harissa-marinated beets and smoked whitefish salad” before continuing with “six savory courses and dessert.” These would include a “sourdough cardamom bread with whipped sorghum butter,” a “raw lamb dish” with “Ethiopian spices,” a “kombu and pastrami-spiced short rib” (“served with giardiniera”), and a “roasted mushroom and onion pierogi — an homage to one of Regan’s signatures.” Desserts, meanwhile, would comprise “foie gras crème brûlée” and a “delightfully American ice cream sandwich flavored with toasted rice and furikake.”

Ultimately, Hunter hoped, by seizing this opportunity, to “be an example for anyone who doesn’t see their self being represented, or their food being represented, or maybe just they want to see something different.” He wanted to show “that there is not a cuisine that Black chefs can’t do,” the idea being “to continue to push the idea that Black chefs are out there and to give them the space that they deserve.” Just the same, doing so would “ideally” push “the idea that chefs are of all colors and backgrounds,” a commendable goal that looks beyond the particulars of his own story to envision a bright, wholly inclusive future that you think everyone can get behind.

Atelier would open on February 22nd and, somewhat paradoxically, be named one of “The Best Restaurants in Chicago Right Now” by Thrillist on the same day. The chef was praised for “his seasonally driven tasting menus, served with style and panache” and including dishes like a “Rutabaga Pappardelle Caesar” and “Clam Chorizo Pozole.” Chicago, on March 1st, would praise Hunter’s “obsessive commitment to local ingredients, even when they aren’t particularly popular ones.” In particular, the magazine would note how the chef offers “a different sort of tasting menu, one that is missing many of the ‘prestige’ ingredients that are typical of the genre” (like “wagyu,” “fancy seafood,” and “caviar”). Regardless, Hunter would admit that “it’s not cheap to buy local” and that, even if what he sources doesn’t have “the same sexiness” as those items, it is important for him to use his platform to support the community.

These articles amount to all the media coverage Atelier has attracted up until this point, a relative vacuum of information that makes the restaurant quite ripe for a proper review. You must also admit that Hunter’s pedigree, even if he has not quite worked anywhere of national renown, really impresses you. The chef has devoted himself to careful local sourcing and hyperseasonal cooking since the very start of his career, combining these admirable stylistic foundations with an eclectic, multilayered flair. The man has also paid his dues and been uncompromising in just the right ways when the integrity he brings to his work has been undermined. Hunter really does remind you a bit of Regan, and, at the precipice of potentially receiving such a huge professional award, he has been entrusted to spread his wings with an owner and team that seem tailormade for his personal style.

Few concepts (especially when large hospitality groups get involved) are willing to let a young, relatively unproven (at least within fine dining) chef put together their own tasting menu. Even more independent ventures—passion projects from first-time restaurateurs—can often be blemished by the owner’s egoism and effectively sap the kitchen’s creativity. However, just as Stephen Gillanders, working with Time Out Market to create Valhalla, has been empowered to cook the finest food of his career thus far, Hunter, in Lacey, has seemingly found a partner equipped to make his dreams come true. It is hard to think, in this era of splashy, soulless openings from Chicago’s usual suspects, of a more exciting proposition.

Whether Atelier’s food ultimately sets off fireworks or comes across as nothing more than a dud, the city will be far richer after having taken the ride. For any unadulterated expression of artisanship, any process of experimentation pursued with humility and care, is sure to provoke something from its audience. Yes, good or bad, the fruits of such work stand apart from anyone or anywhere else. They speak to the truest kind of diversity—that of the individual—and a kind of distinction that transcends all expectations regarding “luxury dining” (or, to invoke a bit of what Hunter himself feels, what the leader of such an establishment looks like). They signal that the Windy City has a path out from the present morass of derivative, redundant concepts toward a reclamation of its heritage as a hyperseasonal, chef-driven city.

In Hunter—and Atelier—you find that rare potential to shift the entire paradigm of an overly commercialized, lowest-common-denominator dining scene, to remind the public that a cook’s job is to commune with nature and not to torture her for the sake of the camera. Few figures, save for Regan herself, have ever taken up that fight, and, perhaps, it will be left to a total outsider to make such a philosophy resonate anew. Those, at least, are the stakes, and they help reveal why this restaurant opening is so special. Success at any cost—that is to say, a success rooted in some desperate desire for fame and money—is clearly not the goal. Hunter and Lacey have bravely resolved themselves to following the flux of the season because they know it to be the only truly worthwhile, forever-rejuvenating approach to their craft. That is something to celebrate long before the first bite touches your tongue.

You have dined at Atelier a total of three times, comprising a period from March through April of 2023. As is usual, you will condense the sum of your experiences into one cohesive narrative that best reflects the highs, lows, and overall dynamism that have characterized your meals.

With that said, let us begin.

The stretch of Western Avenue just north of Lawrence hardly screams dining—let alone fine dining. A bank, a Walgreens, and a mattress store make up the corner while, on either side of Atelier, you find a comic shop and a soccer specialty store. There is not a skyscraper in sight but, across the way, a towering piece of McDonald’s signage. Parking lots, a smoothie shop, and rows of brownstones make up the block surrounding the Golden Arches. There’s a Catholic elementary school and a church for good measure too. The scene, in this corner of Lincoln Square, seems positively suburban, but there’s actually quite a proud food culture simmering under the surface.

Goosefoot, that other longstanding Michelin-starred spot, lies a few blocks to the west: a second high-end renegade in an area that appears to be anathema to the tasting menu form. 016, the cult Serbian-American restaurant, can be found up Lincoln Avenue to the northwest (where Jibek Jolu, too, offers singular Central Asian fare). Korean cuisine, it should be mentioned, is also represented up that way courtesy of Dancen and San Soo Gab San.

However, it is to the south and east of Atelier that the neighborhood really begins to shine. Heading down Western, you come across the new location of Jimmy’s Pizza Cafe (that venerable New York-style slice shop) and Boonie’s Filipino Restaurant (just opened in February). This latter spot, while not quite measuring up to the nearly unanimous praise it has received, is worth a visit—particularly for those (such as yourself) who leave Atelier with some lingering carnivorous craving. Heading down Lincoln to the southeast, you come upon a gorgeous promenade defined by institutions like Gene’s Sausage Shop and Merz Apothecary alongside a range of other small shops and restaurants. Further east, you may come across the excellent Filipino-Cuban eatery Bayan Ko (newly remodeled) or Chicago’s temple of Neapolitan-style pies Spacca Napoli.

Yes, unlike some neighborhoods you trek to during the course of your work, this part of Lincoln Square absolutely sends your tongue wagging. It is no indictment of Atelier’s cuisine that you dream about where you might eat before or after indulging in Hunter’s tasting menu. Rather, as was always true in the Elizabeth era, food that privileges such freshness and finesse stokes the fire for something more straightforward and indulgent. You would even say that few gastronomic concepts, lacking the overflowing bread baskets and roving cheese carts of yesteryear, are equipped to please robust appetites anymore. Smyth (with its burger) and Oriole (with its ham sandwich) have each found a way to do so. And Atelier, though seemingly isolated, boasts plenty of diversions in the surrounding neighborhood that make taking a trip there doubly delicious. A strange consideration, perhaps, but one that is worth dwelling on whenever you are forced to leave the concentrated culinary enclave of the West Side.

Approaching Atelier, nonetheless, could not be easier. Given that the surrounding businesses are not exactly packing customers in through dinnertime, there is ample street parking available right up to the restaurant’s very door. That being said, the façade of 4835 N Western is a bit easy to miss in the daylight (look for the small portion of white brick just before the black exterior of the soccer shop), but, under cloak of darkness, a blue neon sign leads the way.

In something of a funny throwback to the Elizabeth days, the restaurant’s door remains one of the trickiest to open in the city. Approaching it, you feel the temptation to simply push your way through. However, there is actually a small latch to the right that must be turned 90° to disengage the lock. If you have already started to push, you may find that you need to pull the door back toward you in order for the latch to function. Likewise, upon entering, you should make sure to engage the handle once more so that the door fully closes. This all can feel a bit disconcerting as you arrive for a fancy meal, but the staff, to their credit, is always quick to come assist guests when necessary.

Stepping through the portal, you find yourself in a narrow hallway illuminated by glowing strips of light that run along the floor and ceiling. To your right, a series of cut-outs embedded in the wall offer peeks into the dining room. Each one features a plant, some rocks, and algae—making for something of a terrarium effect. To your left, you find a bin filled with ice and a wide array of wine and water bottles. Straight ahead, after just a few steps, you encounter a wooden service station stocked with glassware, menus, and trays. Depending on the exact moment of your entrance, this bartop may be abuzz with front-of-house staff. It is as close to a ”offstage” area as they are granted (save for the area behind the kitchen), but it ensures space in the dining room is maximized and, attuned, as best as possible to a focused guest experience.

Approaching the end of the hallway, you are warmly and enthusiastically greeted by a member of the staff that relieves your party of any belongings and checks your name off of the reservation system. You are led around the corner to one of seven table that make up the dining room, and it is immediately clear that almost nothing of Elizabeth’s aesthetic remains. That is a good thing, you must admit, for Regan’s concept was utterly charming but always felt a bit cobbled together. No doubt, that allowed the personality of both the chef and the food to shine a bit more brightly; however, Atelier deserved a fresh canvas, and Lacey has done an excellent job remodeling the space.

At a structural level, the boundaries of the initial hallway, the dining room, the kitchen, and the area behind it have not changed at all. This is a small restaurant that, at the Michelin-starred level, can best be compared to the city’s omakases. Such a feeling of intimacy can be quite a blessing once you realize that places like Ever and Alinea leave you feeling quite anonymous. However, at the level of interior design, every inch of the room must be accounted for. The white tile of the kitchen remains along with the stainless-steel accents of its appliances, but the white molding that once distinguished the ceiling has been covered over. In its place you find a smooth, white surface that yields to an overhanging segment rendered in bright green. This latter element, studded with new, more extensive lighting, wraps along the ceiling and down the wall, forms an embedded piece of cabinetry that seems to lean diagonally toward the pass. Its five shelves chicly hold the kitchen’s plateware, imbuing this functional end of the space with a surprising burst of color and a sharp, modern silhouette.

This bright green tone is best understood upon consideration of the actual dining area. Like the service station you encounter upon entering, Atelier’s new chairs and tables are rendered in a dark grain of wood. They are complemented by the faded gray of the concrete floor and the brownish-beige color of the surrounding walls (adorned, in certain places, with sculptures made from reclaimed wood). Once more, the old molding on the ceiling has been covered. However, in this part of the room, it has been replaced with a wood-paneled cut-out with glowing edges and a track of lighting running down the middle. Factoring in the lighting that runs along the floor, the entire space appears to glow from its corners. Moreover, when you consider how the earthier tones of the dining room are juxtaposed by the bright white and green of the kitchen (with the white stretching out along the ceiling), the back of house is illuminated very much like the team is on stage.

Taken in all at once, a captivating energy flows from the sleek, shining kitchen toward the more rustic, subdued dining area—one that you think reflects the essence of the cuisine. The hyperseasonality of Hunter’s menu ensures that guests feel totally submerged in nature (those encompassing tones of wood); however, the chef and his cooks imbue their fresh ingredients with a spark of creativity (that burst of white and bright green) that stamps the Earth’s bounty with some sense of personality. These two elements coexist without detracting from the other. No, the contrast actually helps you appreciate how exactly the act of cooking—that is, human technique and artifice—imprints itself upon the natural world. It helps you appreciate the ingredients for both what they are and what the chef, with a careful touch, makes of them. This dichotomy, spatially expressed and quietly reflected upon, can be quite intoxicating for those who subscribe to a kindred philosophy.

Overall, you find Lacey’s remodel of the Elizabeth space to be hugely successful. Atelier looks a good bit more modern without feeling cold. It retains every bit of the intimacy that made Regan’s restaurant feel so special but coats it with the kind of accents, materials, and overarching harmony that befit its (admittedly rather higher) price. The space no longer feels like the ugly duckling of the Michelin-starred cohort—leaning heavily on force of personality to bridge the gap—but fits the expectations of those who might demand a certain baseline of aesthetic refinement. It looks about as good as you could possibly imagine (given certain fundamental constraints) while resonating, too, with some deeper meaning.

Taking your seat, you admire the weighty feel of the chair and table. There are no white tablecloths here to speak of, but the furniture—at a tactile level—invites you to settle in for a while (though one of your dining companions found, at the conclusion of the meal, that the upholstery’s fasteners tore her tights). Nevertheless, the staging of the tables is smartly managed to ensure that the majority of guests enjoy favorable sightlines. One two-top abuts the kitchen itself while a four-top, positioned just beyond the pass (on the other side of the service station), puts you close to the action too. The majority of two-tops (three of them in total) are arranged along the restaurant’s south wall. Rather than having patrons face each other, the chairs are positioned at an angle so that both diners can catch a glimpse of the rest of the room. The remaining two-top and four-top are set near the west wall (on the other side of the hallway from which you enter). These seats are certainly the most isolated, but the view of the kitchen remains adequate (for all but those facing the street) and the interaction with the staff there, with your back to the wall, feels a bit more directed and personal.

With your party settled in, one of the servers arrives to ask everyone’s preference of water. They also take this opportunity to gauge interest in (or, for those who have preselected it through Tock, confirm) any beverage pairings. These comprise three different options designed by beverage director Ali Martin, who stayed on at Atelier after managing the program at Elizabeth.

First, priced at $85, you have the “Spirit Free” option: “a variety of teas, juices, infusions, sodas and other concoctions created by our team to enhance your meal.” These have included drinks named after combinations of diverse ingredients like “Elderflower, Hops, and Fizz”; “Mugolio [or pine cone syrup] and White Verjus”; “Rose Soda [with citric acid]”; “[Smoked] Apple Saba and Thyme”; “Peach and [locally foraged] Spruce”; “Kabosu, Smoke, and Fish Sauce”; and “Brown Sugar, Gnista, and Fizz.” Having sampled this pairing once, you found that the “Rose Soda” formed an excellent pairing with Hunter’s subtly sweetened “Cardamom Sourdough” (with sorghum butter). The rest of the non-alcoholic drinks were rather enjoyable and followed a natural progression too; however, they are more like pleasant passersby to the food than proper enhancers of the constituent flavors. This criticism, in your opinion, holds true of nearly all wine pairings (even rather expensive ones), so it should not be taken as an indictment of the “Spirit Free” pairing. It is a good, highly accessible offering (often prepared tableside and served in beautifully ornate glassware) that may strike some palates as being a bit too sweet at times but, especially when making use of foraged ingredients, adds a nice extra dimension to your dinner.

Priced at $125, the “Standard” pairing is described as offering “primarily wine, with an occasional saké, vermouth or cider making an appearance.” Selections (approximately seven of which are poured per meal) have included:

- Misoo Bitter Aperitivo Spritz ($15 menu price—elsewhere—per 12 oz.)

- Môreson “Miss Molly Bubbly” Méthode Cap Classique ($20 average price)

- 2021 Sallier de la Tour Inzolia ($17 average price)

- Eric Bordelet Sidre “Brut Tendre” ($15 average price)

- 2021 Laurent Lebled “La Sauvignonne” ($26 average price)

- 2018 Precedent “Kirschemann Vineyard” Zinfandel ($32 average price)

- 2020 La Vignereuse “Broco Lee” Braucol Pétillant Naturel ($26 average price)

- 2021 Fitz-Ritter Gewürztraminer Spätlese ($22 average price)

- 2020 Obsidian “Poseidon Vineyard” Pinot Noir ($37 average price)

- Ostinato “Il Dono della Tenacia” Fine Dolce Marsala ($12.67 average price)

You have not sampled any of these yourself, but you can appreciate the blend of more esoteric pours—an aperitivo spritz the menu claims is made in Illinois, a white wine made with the ancient Sicilian variety Inzolia, a classy apple cider, a skin-contact Sauvignon Blanc, a pet-nat made from the Braucol grape—with more traditional (or traditional-seeming) options: a South African sparkler made from Chardonnay, a fruit-forward (and naturally made) Zinfandel, a mildly sweet Spätlese (albeit made from Gewürztraminer), a graceful Pinot Noir (from organic grapes grown in Carneros), and a delectably sweet Marsala. Many of these wines, despite their humble prices, score well with critics (if that’s your thing). Otherwise, you would note that receiving seven glasses of wine from bottles that would cost $30-$74 minimum (assuming a rather tame 100% markup) on a restaurant list strikes you as a fair value at $125. Further, other than Bordelet, you do not see any producers that your average diner would recognize, something that makes the selection feel more unique and exciting.

Priced at $175, the “Reserve” pairing comprises “fascinating and intriguing bottles that we rarely get the opportunity to pour.” These have included:

- H. Billiot Fils “Réserve” Grand Cru Brut Champagne ($57 average price)

- 2020 Costers del Priorat “Blanc de Pissarres” ($32.99 retail price)

- “Sous Chef’s Treat”: Rare Wine Co. Historic Serie “Charleston Sercial” Madeira ($59 average price) mixed with Yuzu Tonic

- 2019 Ruth Lewandowski “L. Stone Zero” Fox Hill Vineyard Sangiovese ($45 average price)

- 2019 ZD Wines Cabernet Sauvignon ($71 average price)

- Konteki “Tears of Dawn” Daiginjo Sake ($39.36 average price)

- 2013 Davis Vineyards “Gratitude” Saralee’s Vineyard Late Harvest Viognier ($25 average price)

You have, in this case, sampled the pairing yourself and felt alright about the value proposition. $175 (per person—though two people can split one serving upon request) goes a long way when purchasing bottles from Chicago’s finest wine lists. However, trying seven wines that would cost $65.98-$142 minimum (assuming a rather tame 100% markup) at a restaurant seems like a fair choice for someone who wants a premium, turnkey beverage solution. The H. Billiot Champagne and ZD Wines Cabernet are great examples of their respective genres while Ruth Lewandowski’s Sangiovese demonstrates how wonderfully natural winemaking techniques can be applied to burly Old World grapes. The “Blanc de Pissarres,” an old-vine Grenache Blanc blend, might be the weirdest of the bunch, yet its rich texture and mineral depth worked well with Hunter’s “Rutabaga Pappardelle Caesar.” The “Sous Chef’s Treat,” served in place of the “Rose Soda” alongside the “Cardamom Sourdough” also formed a clever and delicious pairing. The sake and late-harvest Viognier were more than fine too, but you think the ”Reserve” selection’s ultimate value must really be judged against Atelier’s bottle list.

The beautifully bound leather book, fastened with six rings and featuring attractively speckled paper, features the following preface: “This space in which we find ourselves has always highlighted women winemakers, brewers + toji. We are proud to continue this tradition at Atelier. Throughout this list you will find women made beverage indicated with a female symbol ♀. We include beverages by BIPOC and LGBTQIA+ makers as well. Inquire with our somm to learn more.”

Typically, you find these gimmicks to be overly prescriptive because they arbitrarily limit the scope of wines a restaurant may work with and make the already difficult task of choosing top-value bottles (something precious few buyers are equipped to do) even harder. For several decades now, some of the absolute greatest wines in the world have been made by women like Anne-Claude Leflaive, Lalou Bize-Leroy, Maria Teresa Mascarello, and the Mugneret sisters (Marie-Christine and Marie-Andrée). Female “representation,” at the very summit of the craft, has long existed for those perceptive enough to see it, so any restaurant choosing to promote such a paradigm seems more concerned with branding than running the best possible program. It “represents” a dereliction of the sommelier’s real duty—bringing consumers the best wines at the best prices—for the sake creating easy media fodder or appealing to certain ideological proclivities (an increasingly important dimension of luxury marketing). It obscures the fact that precious few people, no matter their identity, are able to create superlative wine.

To Martin’s credit, the ♀ symbol only appears on something like 25%-30% of the list’s selections, affirming that the intention really is to “highlight” rather enforce a narrow range of products. (On that latter point, you are reminded of Galit’s insistence in proffering overpriced Middle Eastern wines while totally ignoring the other sections of the menu.) Moreover, you think there is value in preserving a piece of Elizabeth’s legacy (the restaurant being, admittedly, a more humble expression of “fine dining” than what Atelier aspires to today with less of a corresponding focus on “fine wine”) via this philosophy. Extending use of the symbol to “BIPOC and LGBTQIA+ makers” also echoes Hunter’s own desire to “be an example for anyone who doesn’t see their self being represented, or their food being represented.” So, in this case, you can appreciate how this feature of the list reflects the concept’s larger character without actually hamstringing its content.

Starting with the “By the Glass” section, you find 11 different wines spread across four categories:

Sparkling

- Hild Elbling Sekt Brut #52 ($14)

- 2021 Paltrinieri “Radice” Lambrusco di Modena ($15)

- R.H. Coutier “Cuvée Tradition” Grand Cru Brut Champagne ($30)

White

- 2021 Seehof Weissburgunder Trocken ($16)

- 2021 Field Theory Albariño ($17)

- 2020 Sylvaine & Alain Normand Mâcon La Roche-Vineuse ♀ ($19)

Orange + Pink

- 2021 La Casa Vieja Palomino ($21)

- 2021 Cutter Cascadia “Strawberry Mullet” Rosé ($16)

Red

- 2021 Yannick Pelletier “Volatil” Rouge ($17)

- 2018 Weingut Weninger Kékfrankos ($15)

- 2018 Movia “Turno” Cabernet Sauvignon ($20)

While, at face value, this range of options seems overly eclectic (or even a bit scary), it is very well chosen. For “Sparkling,” you have a chalky, highly acidic traditional method bubbly made from the ancient Elbling variety in the Upper Mosel alongside a richer, rounder, but still bright Lambrusco made from organic grapes in the ancestral method (with natural, ambient yeast). Both of these bottles offer exceptional value while still displaying the kind of refined mousse and precise flavors that will appeal to diners who prefer Champagne. This strikes you as the right trade-off (rather than finding the cheapest option that can legally label itself “Champagne”) given that the Coutier, for those inclined to spend a bit more, is one of the very best Champagnes at its price point.

When it comes to “White” wines, lovers of Sauvignon Blanc may be disappointed not to see an obvious option. However, the Weissburgunder (or Pinot Blanc) from Seehof (brother-in-law of the esteemed Klaus Peter Keller) offers some of the same aromatic properties with bright acidity and a good dose of ripe fruit. The Albariño from Field Theory (in the Lodi region of California), by comparison, offers a bit more body on the palate with a creamier, honeyed finish suitable for those who enjoy richer styles of domestic Chardonnay. Meanwhile, the Mâcon La Roche-Vineuse—naturally made in Burgundy—splits the differences by combining a rounded texture with stony minerality and refreshing acidity in what amounts to a superb value for the region.

Things get a little weird in the “Orange + Pink” section—courtesy of a natural, Mexican, skin-contact Palomino with notes of butterscotch and a natural rosé of Zinfandel of Oregon with tart red fruit and savory, herbaceous undertones. But that, you think, is what this category is meant for (and the rosé, truth be told, is rather limited production and sounds approachable enough). The “Red” options, much like the “White,” aim to broadly please (even if that doesn’t seem so at first). The “Volatil” Rouge, a whole-cluster Cinsault made naturally, is a light, spicy, totally crushable (or “glou-glou”) wine that will suit those partial to Gamay or the Rhône. The Kékfrankos (another name for Blaufrankisch) by Weninger is a biodynamic wine from Hungary that’s a bit like a darker fruited, more peppery play on Pinot Noir. Finally, the Cabernet Sauvignon from Slovenia—blended with 10% Merlot and organically farmed—offers a more approachable take on the grape that, nonetheless, displays its signature structure, blackcurrant notes, and signs of oak aging.

Overall, Martin must be applauded for putting together one of the most engaging, educational, and ultimately approachable by-the-glass lists you have seen in quite some time. She represents, through these wines, many of the best qualities of natural wine and stands to introduce her customers to bottles that can totally transform how they view their favorite grapes (or, perhaps, introduce them to replacement varieties altogether). Rather than catering to lowest common denominator tastes, Martin anticipates what her guests might typically like and guides them toward options that deliver greater pleasure at a fraction of the price. In doing so, she grows Chicagoans’ appreciation for unconventional wines and nobly works to enrich the wider drinking culture. You cannot think of a higher virtue such a new program might aim for, and there is also a selection of aperitif pours, beers, ciders, sakes, and spirit-free beverages (for those so inclined) to choose from.

When it comes to the bottle list, Martin is mostly making use of what she stored away when the restaurant still operated as Elizabeth. However, this not only ensures that Atelier touts a deeper cellar than most new openings but affirms the kindred philosophies (across both wine and food) that connect the two concepts.

The two most extensive pages of the list—“White” and “Red”—are each divided into three descriptive categories: “mineral + earth,” “fruit + floral,” and “fun + funk.” You will begin by highlighting some of the whites:

mineral + earth

- 2021 Domaine Paul Blanck “Classique” Riesling ($51)

- 2019 Alois Lageder “Porer” Pinot Grigio ($56)

- 2019 Domaine Alain Voge “Harmonie” Saint-Péray ($99)

- 2018 Henri et Gilles Buisson “Sous la Velle” Saint-Romain ($125)

- 2017 Vicentini Agostino “Il Casale” Soave Superiore ($60)

- 2016 Sartarelli “Balciana” Verdicchio dei Castelli di Jesi Classico Superiore ($90)

fruit + floral

- 2020 Domaine Dyckerhoff Reuilly Sauvignon Blanc ($61)

- 2021 Sandhi Sanford & Benedict Chardonnay ($118)

- 2021 House of Brown Chardonnay ♀ ($48)

- 2020 Tania et Vincent Careme “Terre Brûlée” Chenin Blanc ($40)

- 2017 Tatomer “Kick-on Ranch” Riesling ($75)

- 2019 Gust Wines Petaluma Gap Chardonnay ♀ ($69)

fun + funk

- 2020 Domaine du Nival “Matière à Discussion” ($78)

- 2021 Clos de Tue-Bœuf Sauvignon Blanc ($54)

- 2000 Merkelbach Kinheimer Rosenberg Riesling Kabinett ($90)

- 2019 Ktima Ligas “Yomatari” Retsina Blanc ($80)

- 2017 Sono Montenidoli “Carato” Vernaccia di San Gimignano ♀ ($99)

Relative to the by-the-glass section, you like how the bottle list checks all the boxes when it comes to popular grape varieties. Lovers of Chardonnay, Pinot Grigio, Riesling, and Sauvignon Blanc will find one or more options in a range of styles (further illuminated by those unique headings). Classic producers like Paul Blanck and Alois Lageder offer approachability and value while newer growers like Henri et Gilles Buisson, Sandhi, and Tatomer represent some of the best examples from the new guard. Martin shows an admirable degree of restraint and mainstream appeal with this selection, but she would be selling the restaurant short if she didn’t include some oddballs.

The Saint-Péray, Soave, and Verdicchio dei Castelli di Jesi are not all that weird in truth, but they represent styles of wine marked by greater texture, minerality, earthiness, or even bitterness when compared to more quotidian varieties. (These notes, of course, often form a great pairing with seasonal, vegetable-forward fare.) Yet bottles like the “Matière à Discussion” (a 10% ABV dry wine made from Vidal, the same grape used to make ice wine, in Quebec), “Yomatari” (a Greek wine made, in an ancient style, with the addition of resin from Aleppo pine trees), and “Carato” (an organic Vernaccia with a strong savory character that is perfect for cheese) just ooze personality. With markups remaining between 100%-150% of retail price across the board (compared to the 200%-300% or even 400% that can be seen in some fine dining venues), these more esoteric wines can be sampled at a friendly price that prevents those willing to take a chance from feeling burned.

Next, you will look at the reds:

mineral + earth

- 2018 Domaine Petitot Nuits-Saint-Georges “Les Poisets” ♀ ($120)

- 2017 Domaine Vallot “Le Coriançon” Côtes-du-Rhône ♀ ($60)

- 2017 Mari Vineyards “Praefectus” ($92)

- 2018 Château de Nalys “Saintes Pierres de Nalys” Châteauneuf-du-Pape ($138)

- 2014 Château La Peyre “Cru Artisan” Saint-Estèphe ($108)

fruit + floral

- 2020 Siletto Estate “Adroit” Trousseau ($75)

- 2019 Beckman Vineyards “Estate” Grenache ($60)

- 2018 Peay “Savoy Vineyard” Pinot Noir ♀ ($153)

- 2019 Burn Cottage “Sauvage Vineyard” Pinot Noir ♀ ($190)

- 2018 Figgins “Figlia” ($135)

fun + funk

- 2018 Domaine de la Pinte Arbois Trousseau ($118)

- 2020 Enderle & Moll “Liason” Pinot Noir ($99)

- 2017 Slobodné Vinárstvo “Partisan Cru” ♀ ($66)

- NV Amplify Wines “Lightworks” Vol. 5 Merlot Solera ($55)

- 2019 Nicolas Badel Saint-Joseph ($54)

Once more, you really like Martin’s decision (relative to the more interesting by-the-glass options) to reward diners with approachable bottles that include a Bordeaux, a domestic Bordeaux blend, a Grenache, several Pinot Noirs, a couple Rhone blends, and Syrah. Many of these producers—like Burn Cottage, Enderle & Moll, Figgins, and Peay—are simply excellent, and you find the prospect of getting a Nuits-Saints-Georges lieu-dit for $120 to be quite appealing too. Of the more interesting selections, a pair of Trousseaus (one domestic, one from the Jura) form great options for those who want something a bit darker than Pinot Noir but still in the same ballpark. The “Praefectus” (an 85% Cabernet Franc, 15% Cabernet Sauvignon blend from Michigan), “Partisan Cru” (a chuggable, natural Cabernet Sauvignon blend from Slovakia), and “Lightworks” (organic, domestic Merlot blended with seven different vintages from a solera) are a bit more provocative. However, they still sound hedonistic and, thus, crowd-pleasing to those who might like to take the plunge. The markups in this section creep up to the 150%-200% range, but you still feel that is fair for wines that are generally pretty orthodox.

Overall (and though you are omitting the “Sparkling” and “Orange + Pink” sections of the bottle list from this analysis), you think Martin has done a great job with Atelier’s beverage program. Of course, as you have already mentioned, she is building somewhat on the work she already did at Elizabeth but deserves to profit from doing so. Besides, crafting a by-the-glass selection and set of pairings to go with Hunter’s cuisine surely presents an entirely new challenge.

Relative to a menu that costs from $165-$190 (depending on the exact day one chooses to dine), the glasses of wine (ranging from $14-$30) and pairings (ranging from $85-$175) seem appropriately priced and imbued with character. You would single out the by-the-glass selection, the “Spirit Free” pairing ($85), and the “Standard” pairing ($125) as the best values because they combine the right amount of novelty with an admirable amount of mainstream appeal. The “Reserve” pairing ($175) is serviceable—maybe even good—but you feel it offers diminishing returns. For the same sum (per person or even if two people were to split it), you could purchase one or two bottles—likely only marked up 100%-150%—off of the impressive bottle list that suit your particular tastes. The focus on natural wines from some of the best exemplars of the genre—balanced by plenty of classics—also ensures that whatever money you spend secures a great deal of pleasure even when you find yourself paying closer to a 200% markup. Likewise, a $50 corkage fee—while high—is waved when purchasing from the list and accords with a selection that is in no way short on value.

Ultimately, Martin’s beverage program feels like a friendly accompaniment to Hunter’s food that, like the menu itself, surprises you with its hidden depth. Maybe it has to do with the focus on natural wine (or on those BIPOC and LGBTQIA+ producers), but you just do not see many of these bottles elsewhere around town. Avoiding that feeling of drinking something conventional—something you have seen time and again (maybe even at the grocery store)—is essential when building a value-driven selection. That has been accomplished with aplomb, and even you—a devotee of those natural wines—find a lot to like.

The quality of the program’s constituents, it should be noted, is matched by the wine service itself. With such an intimate concept, Martin is given full reign to interact with all her guests and really share the stories (as well as technical details for those so inclined) that undergird each of the selections. She brings a great energy and positivity to the table that totally evaporates any trace of pretentiousness that diners can sometimes feel when receiving arcane vinous spiels. Yes, just as Hunter induces patrons to come and “see something different” in the world of fine dining, Martin’s program—and, particularly, its presentation—is up to the same task. There’s a great synergy of spirit and approach to the idea of craft that marries the restaurant’s food and drink and meaningfully adds to the Atelier experience.

The rest of the front-of-house team, likewise, mirrors this energy. Most, if not all, are also holdovers from Elizabeth, and you can immediately tell how at home they feel in the space. Principally, rather than reflecting the jitters or contrived scripting that can mark a new opening, the servers speak with total confidence and ease. They know where everything is—as well as knowing each other—so that the evening proceeds with a total feeling of serenity: no flubs, no miscues, no scrambling to do this or that, but the kind of fluency that takes months or years to develop. Atelier, it should be noted, is not quite aiming for the kind of strict synchronization one typically needs to secure multiple Michelin stars. Such a serious tone would just not fit with the venue or its guiding philosophy. But, indeed, there is a culture of excellence and pride that ensures drinks are refilled and plates are cleared without the slightest delay. This is not drawn from any smug, backslapping corporate culture but smacks of a real sense of ownership. The team has remained in place because they like whom they work for, are taken care of commensurately, and believe in the restaurant’s larger mission. Each individual is bound by a desire to share that story with their guests, and they accomplish this cannily with a good dose of sincere curiosity regarding how each dish is received.

To that point, the staff has clearly sampled Hunter’s food—even, from visit to visit, the very newest creations—and can really identify with your own experience of the recipes. It is galling to think that this practice is not common across all of fine dining, where servers—sometimes—are treated like empty vessels only suited to facilitate a dialogue between kitchen and customer. How strange it is to enjoy a bite of something that is totally shrouded in mystery (or, at the very least, reduced to few bullet points to be memorized) for the person who brought it to the table. How rewarding it is—for both server and served—to share (even if not tasting the same dish at the same time) in the same visceral delight that a certain comestible may achieve. This is where that feeling of pride comes to the fore again: the staff is not just working a job but inviting you to share in a meal and savor the kind of social bonding that emphasizes how the human dimension of terroir works in harmony with the chef’s hyperseasonal cuisine.

Lacey, too, must be given credit for building—or is it preserving—this culture. The truth is probably somewhere in the middle, as the Atelier owner worked for Regan (and knows well what made her concepts so special) but has had to adapt what he learned to a pandemic and two new chefs. It is telling that staff retention has remained so good through what was more than a two-month closure, and this becomes even more striking once you realize that the suited figure clearing plates during service is Lacey himself. Yes, the owner—much in the same way Regan did—leads from the front by humbly shouldering the restaurant’s most mundane tasks with an exemplary attitude. He might softly inquire, at some point in the evening, if you are enjoying everything (just as any good manager would do), but the industry veteran truly is committed to letting Hunter, Martin, and the rest of his team take the spotlight. Lacey is wholly engaged, totally present in the operation of the business without any trace of the ego or dilettantism that characterizes some owners. That is not surprising given his long history here in Chicago, but it deserves praise. Atelier’s earnest, understated, and effortlessly personable approach to hospitality flows from the very top. When ownership is so engaged but still makes room for everyone to express themselves, good things inevitably follow.

Even Hunter, when he delivers plates to the various tables, displays a palpable degree of humility and gratitude toward those enjoying his food. You observed these visits moreso during the occasion of your first meal, with the chef being more contained to the kitchen subsequently. That’s not a bad thing when it comes to ensuring the quality of each and every dish; however, he should aspire to once again forge those personal connections with guests whenever it feels appropriate. For that was a hallmark of how Regan ran Elizabeth (the chef even going so far as to buss tables), and it stands to reason that Atelier’s diners have been drawn there in part due to Hunter’s personal story. The space is so intimate that it almost necessitates some amount of interaction, however small, in order to really make the meal—consciously rooted in the identity of its chief craftsman—memorable.

With the beverage order settled and your rapport with the staff established, it comes time to address the menu. In truth, there are no decisions to make regarding the food (save for potentially addressing any allergies or other restrictions): you buy the ticket and take the ride as steered by Hunter’s singular vision. However, it may be worth briefly dwelling on how Atelier’s menu price compares to the rest of the dining scene. While the restaurant certainly benefits from being one of the city’s newest fine dining concepts, its ultimate value proposition (especially for those who do not savor more than one or two tasting menus a year) is best considered in accordance with a wider peer group.

As previously mentioned, Atelier’s menu price fluctuates between $165 (on Tuesday, Wednesday, and Thursday) and $190 (on Friday and Saturday)—exclusive of a 22% service charge (2% of which is dedicated to employee healthcare). Thus, while the restaurant (in the old Elizabeth fashion) still offers occasional flash sales on tickets, you will make use of the $190 sum in order to help guide the majority of consumers who may find themselves paying the maximum.

On the lower end, a meal at Atelier is priced higher than the tasting menus at establishments like Sepia ($95), INDIENNE ($110-$120), Porto ($120), Elske ($125), North Pond ($125), Jeong ($135), The Coach House by Wazwan ($150-$175), Kyōten Next Door ($159), Boka ($165), Sushi by Scratch Restaurants ($165), Topolobampo ($165), and Goosefoot ($175), as well as Smyth’s entry-level “Classic” menu ($175).

Atelier’s price roughly accords with places like Next ($155-$195), Schwa ($165-$195), Brass Heart ($185), Mako ($185), Valhalla ($185), and Temporis ($195). Meanwhile, the restaurant falls short of Chicago’s highest stratum: places like Omakase Yume ($225), Esmé ($235), Kasama ($235), The Omakase Room ($250), Moody Tongue ($285), Smyth ($285-$345), Oriole ($295-$335), Ever ($325), CLAUDIA ($350-$435), Alinea ($305-$495), and Kyōten ($440-$490, inclusive of service charge).

Ultimately, Atelier’s price point is situated in the middle of the pack. The restaurant does not represent one of the city’s ultimate values (for those looking to secure Michelin-quality cooking at the lowest cost), nor does it distinguish itself as one of the dining scene’s most superlative splurges (for those who, right or wrong, chase multiple stars or a certain sense of exclusivity when celebrating). It does not embody any particularly photogenic, viral style of cooking (like molecular gastronomy) or stand as a refined example of a certain ethnic cuisine (with Danish, Filipino, Indian, Korean, Mexican, and Portuguese cultures each having one or more standard-bearers).

You think the average consumer will likely learn about Atelier as one of Chicago’s newest fine dining openings, a label that (also given the similarity in price) begs a comparison with Valhalla. Some may live close to that Lincoln Square area (where Goosefoot, also similarly priced, offers a longstanding alternative) or, more specifically, miss the experience they formerly had at Elizabeth. Regan, of course, is not involved with Atelier, but few other restaurants—save for Smyth and maybe North Pond—devote themselves to hyperseasonality. These customers may crave a kindred style of cooking surrounding by familiar faces in a nostalgic space while others may find that Hunter’s identity, underrepresented here at the tasting menu level, makes for appealing story in itself.

As far as your own understanding of the concept goes, you think the Atelier/Valhalla comparison is an attractive one to make given that both are new, chef-driven restaurants encapsulating a wide range of cultural influences. Further, the two establishments charge similar prices ($190 vs. $185) and offer similarly eclectic beverage programs but—despite both touting great hospitality—diverge rather clearly in their ambiance. How much does this environmental influence, which you singled out rather clearly in your article, really matter?

Otherwise, in pure terms of cuisine, it may also be worth considering how Atelier approaches seasonality, vis-à-vis dynamism and experimentation, relative to Smyth. It is not quite fair to hold Hunter’s food to the standard of Shields and Feltz’s just yet, but engaging with the chefs’ shared philosophies may help, by contrast, to illuminate the newcomer’s particular perspective on the Midwestern bounty. Of course, the best way to do so is by tasting.

Dinner begins with a sprawling presentation of dishes titled “Larder,” referencing the cool storage areas used to store bread, milk, butter, vegetables, fish, and meats before the widespread adoption of the refrigerator. These rooms existed in households throughout the Western world, but the term today reflects some special affinity with the Southern United States (as demonstrated by the Southern Foodways Alliance’s book The Larder: Food Studies Methods from the American South). Any particular association with Hunter’s personal history is not made explicit; however, you like the idea of using this concept as an organizing principle for Atelier’s larger theme of hyperseasonality.

The ”Larder” set comprises “Fromage Fort” (later replaced with “Pimento Cheese”), “Beets” (later replaced with “Carrot + Parsnip”), “Whitefish” (later replaced with “Trout”), and “Lamb Gored Gored” served with crackers, focaccia, truffled mustard, fennel pickles, and blueberry compote. The whole assortment arrives at the table in quick succession, yielding a feeling of bounty that placates hungry palates and assures you that the chef, despite the tasting menu format, is eager to please.