You rarely visit Sushi-san anymore, but it will always remain a nostalgic place for you. Though LEYE opened the concept at the tail end of 2017, it was really in 2018 that you took notice.

In the years prior, you had witnessed New York City’s omakase boom. Masa (opened in 2004) and Soto (opened in 2007) had already held their Michelin stars (three and two of them respectively) for quite some time. Kurumazushi, Sushi Azabu, and Sushi of Gari merited single stars during the early years of Bibendum’s guide too (representing some of the city’s more notable concepts alongside then-starless mainstay Sushi Yasuda). Apart from Masa—which, cloistered in the Time Warner Center alongside Per Se, formed a “temple of gastronomy” from the very beginning—these were charming places that catered to a particular niche but did not possess the kind of glamour the omakase genre now entails.

Pete Wells’s four-star review of Sushi Nakazawa for The New York Times in 2013 is generally regarded as the turning point. The critic, one of painfully few whom you respect, reflected on this paradigm shift when demoting the restaurant to three stars in 2020: “I didn’t know it was going to change the sushi landscape…but I knew it was original and unexpected. I also knew that no other omakase meal lobbed out so many thrilling pieces of sushi, or was quite as entertaining. Within a year, its name was a metonym for excellence in the art of raw fish.”

Looking back, the critic deftly describes what made the restaurant so special for its time: “The great inspiration…was to translate an elite Tokyo-style sushi counter in ways suited to an American audience. They didn’t try to make you feel as if you were in a 1,000-year-old Zen temple in Japan…. Mr. Nakazawa put customers who might have felt out of their depth in a hushed, old-school nigiri sanctuary at ease. He was already a minor celebrity from his appearance in the 2011 documentary ‘Jiro Dreams of Sushi’…. Out on his own, he showed an instinct for the spotlight that the movie barely hinted at. His smile was quick. His laugh was quicker, and was heard every time he successfully startled diners by flicking live shrimp on to their plates.”

Though some “traditionalists found Sushi Nakazawa’s mix of American and Japanese sensibilities off-putting,” it “helped introduce Tokyo-style omakase, in which the chef decided what you would eat based on a close reading of the ocean’s seasons and, to some extent, pure whim, to New Yorkers who weren’t necessarily students of Japanese culture. You didn’t need to know that shiny-skinned fish are called hikari-mono, or that kohada come into season in April…. You just sat back and let it happen.”

The ”downside” of this new degree of accessibility was personified by the “rich young men” known as “’bromakase’ patrons” and lampooned on the show Billions in a scene shot at Sushi Nakazawa itself. There, “a sushi connoisseur upbraids a young moron who is sloshing each piece of nigiri in soy sauce as if he were dunking a mop into a bucket of soapy water.” And now, compared to when the restaurant first opened, “Nakazawa’s chefs and servers…warn you at the start of the meal to eat every piece in one bite, and never to top sushi with pickled ginger.”

You will leave Wells with his summation of the restaurant’s effect on the wider genre: “Before Nakazawa, the best omakase meals were typically served inside restaurants that did most of their trade in à la carte sushi; after Nakazawa, one dedicated omakase parlor after another opened up, and like Nakazawa, many of them were inspired less by Japanese customs than by modern New York stagecraft.”

With Masa, Nakazawa, and Soto as foundational experiences, you would sample a succession of increasingly splashy openings like Shuko (November 2014), Kosaka (December 2015), Sushi Zo (December 2015), Sushi Ginza Onodera (May 2016), Ichimura (January 2017), and Sushi Amane (June 2017). After your departure, the city would hit an even higher peak via establishments like Sushi Noz (March 2018), noda (March 2018), Nakaji (March 2020), Shion 69 Leonard Street (May 2021), Yoshino (September 2021), icca (October 2021), and ITO (Februrary 2022). The genre shows no signs of oversaturation (yet) and benefits—nearly a decade after Nakazawa’s opening—from a mature base of consumers that empower a broad range of price differentiation (with top spots costing around $500 per person and Masa charging $750-$950) and a high degree of distinction at the stylistic and aesthetic level.

In 2018, Chicago’s sushi scene (for you struggle to term it an “omakase scene”) could barely be called nascent. Yes, the craft had been practiced in the Windy City for quite some time, with places like Lawrence Fish Market catering trays of maki and sashimi for more than 40 years and Katsu serving straightlaced Japanese fare for nearly 30. However, while these kinds of expressions are, of course, beautiful in their own way, it stands worlds apart from the contemporary framing of sushi as a particularly trendy form of luxury dining and, more specifically, from omakase’s present privileged status within the experience economy. These “uncouth” Chicagoans ate sushi—oh yes they did—but never thought to worship the chef or dick-measure about who has the fattiest tuna.

Japonais, you suppose, had its heyday as “one of Chicago’s most hip dining destinations”: opening under chefs Jun Ichiwaka and Gene Kato in 2003 before bringing on Masaharu Morimoto in 2013 and closing in 2015 amid an eviction lawsuit. While the restaurant’s Las Vegas offshoot would last from 2007-2017, the New York location only survived from 2006-2011 after being branded a “big-box” “Nobu knock-off” and being saddled with a one-star review from The New York Times. In its time, Japonais unabashedly occupied the “fusion” genre that has today become anathema to tastemakers and critics. Slinging spring rolls, burgers, teriyaki, tempura, and filet mignon (cooked on a hot stone) helped comfort skeptics who, otherwise, would never set foot within a dedicated sushi concept. Thus, the restaurant helped introduce locals to forms like nigiri through mere exposure if nothing else. The association between raw fish and a sprawling, sexy venue filled with fashionable people had been constructed. These are the baby steps a dining scene must take to cultivate taste in new categories and eventually support more specialized concepts.

SushiSamba (opened in 2006 and closed in 2014) was very much cut from the same cloth as Japonais and dove, in its time, even more deeply into the fusion model. Sunda (opened in 2009), by comparison, embraces more of a Pan-Asian model while the Chicago branch of Roka Akor (opened in 2011) buffers its raw fish selection with a focus on steak. Arami (opened in 2011) would somewhat buck this trend (like by “discouraging you from using a lot of soy”), but KAI ZAN (opened in 2012), too, still embraces the fusion mold in its own way. But Juno (opened in 2013) seemed to signal a change in mentality. Yes, there were “oyster shooters, grilled king crab, and smoked kampachi” on offer, but the menu was “tempura-free” and emphasized raw fish “flown in from Japan, Korea, Hawaii, and New Zealand” with a “private seven-seat omakase chef’s table where you can go off-menu.” And Momotaro (opened in 2014) would up the ante even more: “Jeff (Ramsey) and Mark (Hellyar) are very offended by that fusion word…. It’s not our style. Kevin and I don’t like mango purees and aioli spread over our nigiri.” BRG would ultimately aim for a blend of “90 percent traditional, 10 percent modern” at the concept that—under former Japonais chef Gene Kato—remains respectable (if not superlative) today.

2016 would see LEYE get in on the act with the opening of Naoki Sushi within the former L2O private dining room at Intro. The small casual restaurant featured crowd-pleasing items like “Edamame ‘Guac’ Dip” and “Kagawa Chicken Teriyaki” but remained surprisingly focused on nigiri, sashimi, temaki, hosomaki, and maki before making way (in 2019) for the aborted reboot of Ambria (in partnership with The Alinea Group). In 2017, Brendan Sodikoff’s Hogsalt Hospitality took aim at the same genre with the announcement of Radio Anago. The spot (where Ciccio Mio currently sits) would open in March of 2018 with a focus on “sushi classics” and a few frills like “Steamed Pork Buns,” “Wagyu Tartare,” and “Houji Fried Chicken” (with edible gold). Radio Anago would close in May 2019 with the frank admission that “it didn’t work.” (Katana, a “glitzy LA import,” would also open near the Marina City Towers in 2017 but eventually close in the aftermath of the pandemic.)

But Sushi-san, perhaps benefitting from its comparably prime location at Grand & Clark, proved more successful. The restaurant expanded on LEYE’s existing Ramen-san concept with “hip-hop references” and a “relaxed vibe” playing home to “nigiri bombs, sashimi sets, tempura, and late-night yakisoba.” It was open until 1 AM on Fridays and Saturdays and, with non-Japanese offerings like “Vietnamese pork and a cocktail made with Chinese five spice,” aimed at a “younger demographic” than Naoki with “a more modern presentation.” It all sounded a bit gimmicky on the surface—like something made in the Sunda mold (but still even more casual)—yet Sushi-san delivered. The restaurant earned two stars from the Tribune, with Phil Vettel singling out diverse items like the “cute and smart beverage program,” “Tako Taco,” “Beef ‘n Bop,” edamame, and “12-seat hand-roll bar” for praise. The critic also paid special compliment to the $88 “Oma-Kaze” (named for Sushi-san chef Kaze Chan), a “reservations-only experience that has exactly four seats.” Vettel admitted the restaurant’s take on omakase was even “worth an extra star.”

Having returned from New York City and sampled the omakases offered at Arami, Juno, KAI ZAN, and Momotaro, you quickly made Kaze’s counter your home. On any given night, the rest of Sushi-san brimmed with energy, but sitting in front of the chef lent you his undivided attention. He was quiet, focused, and precise but still a good deal friendlier than your typical, stoic itamae. Most importantly, the $88 sum ensured that it was always Kaze himself who prepared your nigiri—often with a dose of humor and, after just a few visits, the kind of subtle (though shining) warmth that makes regular patronage so fulfilling.

Originally, it was said that the “omakase selections will rotate monthly,” but the menu—in fact—showed much more dynamism. Kaze served “whatever strikes…[his] fancy that day,” representing “the best of everything” from the totality of his restaurant’s fish sourcing. Of course, certain pieces were destined to repeat, but you were really impressed at how the chef always managed to find a new fish (or a particular segment of a familiar fish) to serve on a week-by-week basis. His toppings too—like “white soy, pickled plum and seaweed”; “lime zest and salt”; or “ponzu jelly and minted salt”—were on the pronounced, flavorful side without ever descending into needless novelty. The 18 bites, at $88, ran the gamut of all the usual suspects (tuna from Tsukiji, uni from Hokkaido) while preserving an immense feeling of value. The accompanying wine selection was not quite up to RPM levels of indulgence, but prices were more than fair and the other beverage options sometimes proved fun.

Overall, the “Oma-Kaze” totally overperformed for its era (vis-à-vis Chicago’s other exemplars of the genre). Sushi-san, to you and those you shared it with, formed a perfect introduction to the craft that ditched some of omakase’s pomp and ceremony while still privileging quality and achieving a kind of accessibility that, today, is even more the rage. You enjoyed the “Oma-Kaze” more than a dozen times from February of 2018 through July of the same year. It formed a thoroughly satisfying, often delightful experience (even in the context of menus that had cost three or four times the price in Manhattan). It was a fixture in your life—until it wasn’t. For the world of omakase amounts to something like an arms race, and, with no hard feelings (though perhaps a tinge of sadness), you followed the flow of Chicago’s rapidly maturing market.

That all began with Omakase Yume’s opening in July of 2018. Sangtae Park started slinging 15 to 17 courses in an eight-seat space entirely devoted to showcasing his craft. Priced at $125 (back then), the restaurant presented a noteworthy upgrade on what Kaze was doing at Sushi-san. Of course, economies of scale may have meant that LEYE’s relative value and quality could not be neatly reduced to what they were charging. But Yume had the intimacy, the stagecraft, and the charm that signaled omakase—untethered to any more casual concept—might finally begin to thrive in earnest. Service from Park’s wife was warm, the BYOB/corkage policy was generous, and the restaurant—even if much of the nigiri selection stayed consistent—always had new delicacies to offer à la carte at the end of the meal. You would patronize Yume six times over its first few months of operation before your eyes began to wander.

First, that took the form of Omakase Takeya (opened in August of 2018): 16 courses for $130 in a calm, underground lair beneath Fulton Market’s bustling Ramen Takeya. Another restaurant had upped the ante in terms of price, and it promised an experience that was also more focused and secluded than Sushi-san. Chef Hiromichi Sasaki didn’t quite offer the same “one man show” as Park—he was helped by two sous chefs but, crucially, formed each piece of nigiri himself. The wine and sake selection wasn’t much to write home about either. But you thought the nigiri was well-made and flavorful in a fairly traditional style. It was also presented in a space that felt carefully curated and pleasingly reverential. More than anything, it was heartening to see another establishment take aim at the genre and help to cement its burgeoning appeal. You visited Takeya some three times after opening before, once more, another omakase caught your eye.

Your admiration for Otto Phan’s work has now been extensively recorded. However, in September of 2018, you visited Kyōten with almost no sense of what to expect. At $220 for “approximately 20 bites,” it was clear that Chicago’s sushi scene was starting to get serious. Though arriving from Austin, Phan confidently occupied an aspirational price point that seemed to have more in common with Manhattan than anything the Windy City had yet seen (and that still holds true today). Of course, the chef had actually worked for Masa before making his name back home in Texas. He brought luxurious touches like caviar and truffles to the table too. But what struck you more was the larger grain of Phan’s sushi rice (now a hallmark of his and his protégé’s approach to the craft) and the corresponding size of his fish. Kyōten, even if the environment back then could not hold a candle to the current remodel, embodied a clear, distinct perspective on omakase from the start. When you made your second visit, Phan did not hesitate to meaningfully change the menu and has continued to do so every meal since. Yes, there were rough edges, but the chef’s potential was astounding. His outsider status, combined with total fidelity to the diners that defined his new home, was totally endearing. You were smitten, and you pretty much never looked back or considered eating sushi anywhere else.

When Mako opened in March of 2019, you put the restaurant through its paces. B.K. Park, described in his own words as “one of the country’s premier sushi chefs,” had worked at Arami and later opened Juno. Those places never really impressed you by the time you tried them—admittedly relatively late in their life as concepts—but the chef was a fixture in the community. Offering “up to 25 courses for $175,” Mako was poised to compete with Yume, Takeya, and Kyōten while offering an attractive value proposition (coming in at the higher end without looking to usurp Phan’s $220 price). The restaurant would be a “culmination” of Park’s “years of expertise seeking out and serving the most pristine fish in the world.” He had (once more in his own words) “done much to teach Chicagoans about sushi” over the last two decades and now felt the city was “educated enough” for an omakase spot to flourish. The chef was even rather emphatic that “so many chefs or owners…don’t know sushi” (“they think they can make money just making a roll, fill it with sauce”) in the Windy City.

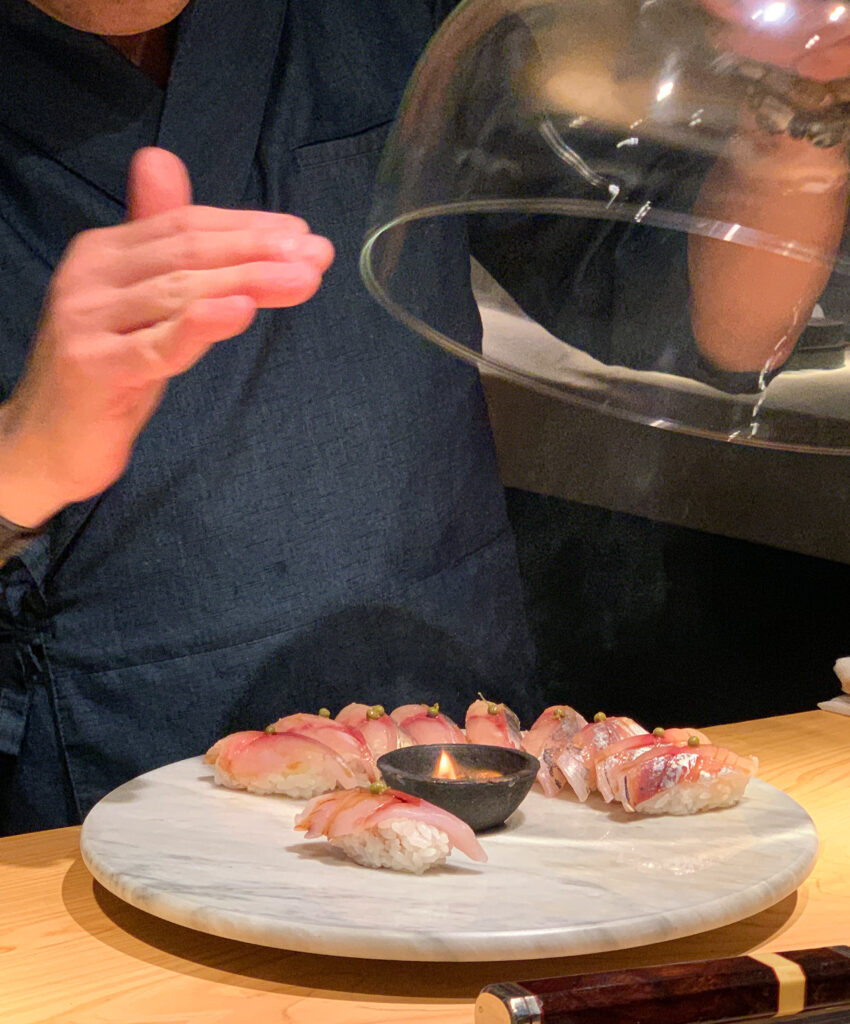

Mako certainly was the glitziest of Chicago’s omakase openings, boasting 22 seats (of which 12 are at a “graphite and walnut wood sushi counter”) in a beautifully lit and outfitted space. The meal’s aesthetic touches—like Park’s favorite cloches and a terrarium-like presentation of sashimi—surpassed the competition. The restaurant even benefitted from the unaccredited work of Tim Flores, who cooked preparations of sea bass and duck behind the scenes that would intersperse the meal’s three separate flights of nigiri. Yes, Mako had a lot going for it, but the concept was fatally flawed. Across four visits, the menu did not only show little development, but, in truth, Park never actually prepared any of your sushi. The chef split his workload with an apprentice, and fair enough you say. But the restaurant made no effort to seat you in Park’s section on subsequent visits, and there was even one occasion when the main man was not there at all and your meal was left in the hands of the apprentice’s apprentice. Compared to Sushi-san, Yume, Takeya, and Kyōten, the price you paid did not guarantee the master would actually touch your food. No, at Mako, you were treated to an assembly line style of nigiri production punctuated by unrelated hot plates in a sexy setting: a perfect way to placate diners being dragged there by their significant others. Ultimately, the restaurant struck you as a clever business concept that glossed over an important truth: Park may like to dress up but has little interest in actually working as a sushi chef anymore.

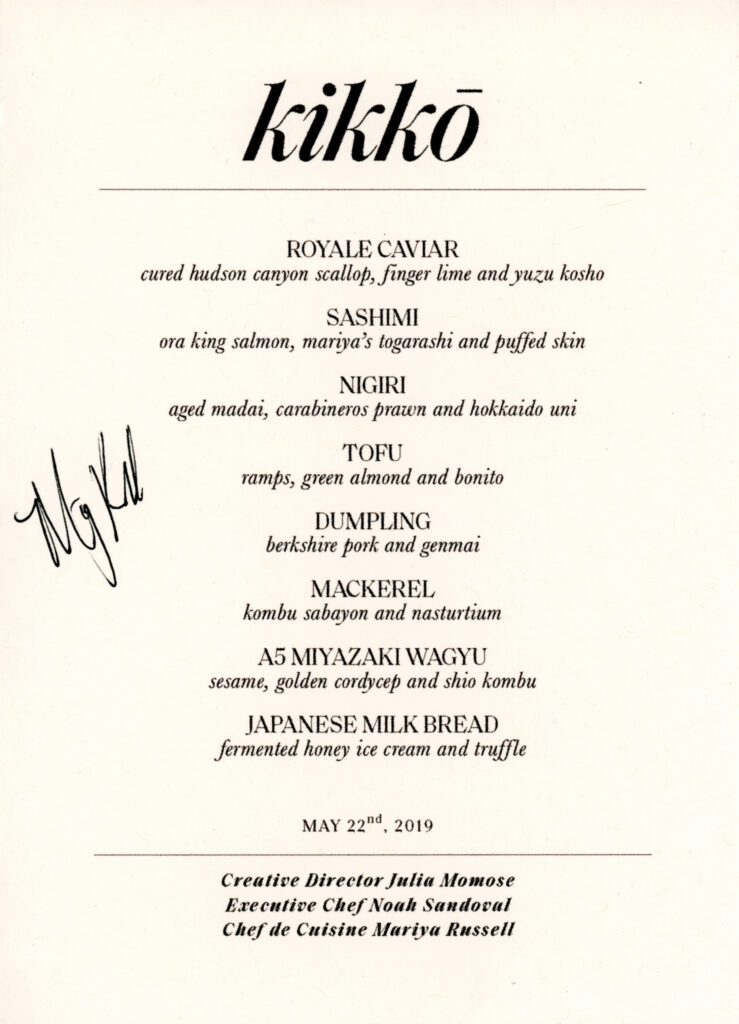

Next, Kikkō would open underneath Julia Momose’s Kumiko in May of 2019. Mariya Russell, the concept’s chef de cuisine, would become “the first black woman to command a Michelin-starred kitchen” later that fall. Her experience included time at Green Zebra, The Bristol, Nellcôte, Senza, and Oriole (working for her mentor and “big brother” Noah Sandoval at the latter two). On paper, this would not seem to suggest that Russell had any intensive training in the craft of sushi. However, pre-renovation Oriole did typically serve one or two pieces of nigiri as part of its tasting menu, and Kikkō played to the chef’s strengths.

The $130, 10-seat omakase was set within a sleek, moody downstairs lounge and juxtaposed by a range of Momose’s expertly crafted pairings. The menu started with cured scallop and caviar before traversing a serving of sashimi (salmon with housemade togarashi and puffed skin) and a trio of nigiri (madai, prawn, and uni). Then, it shifted toward more substantial fare: tofu (with ramps), a pork dumpling, mackerel (with kombu sabayon), A5 Miyazaki wagyu, and the delectable Japanese milk bread (with fermented honey ice cream and truffle) to finish. You might have been tempted to term this format sacrilegious, yet you think the right word is actually “differentiated.” Compared to B.K. Park at Mako, Russell was not posing as a master sushi chef while simultaneously desecrating the craft and leaving an unseen collaborator in the kitchen to pick up the pieces. Rather, she, husband Garrett, and Momose had created an experience that was singular, competitively priced, and quite satisfying. They put their personality and warmth into each performance and made it feel memorable in a way that the city’s more stoic (or conceited) chefs couldn’t. To you, with Phan’s technical mastery totally transcending anyone else in town, Kikkō excelled by expanding the idea of omakase in Chicago beyond nigiri while still prizing tableside action. More importantly, it cemented the idea that this genre primarily forms a stage for the chef’s imagination and engagement—that it should be judged on the basis of storytelling and sincerity as much as rice, fish, and flash. Thus, it formed a worthy addition to the scene (and was richly rewarded by Bibendum despite being a bit unconventional).

Ultimately, Kikkō would come to an end in the wake of the pandemic—though not unhappily: Russell and her husband were moving to Hawaii. However, Sushi Suite 202, which first opened in February of 2020, would make it to the other side and resume operation in January of 2021. The concept, a spin-off of New York City’s Sushi by Bou, offers a “17-course 60-minute omakase sushi dining extravaganza” at a six-seat bar for $130 per head. Of course, this all took place in a room on the second floor of the Hotel Lincoln, with the restaurant being masterminded by a company that specializes in maximizing the “financial potential” of “underutilized spaces.”

Nobu would finally open its Chicago location (set within a Nobu-branded hotel) in October of 2020, more than seven years after its initial announcement. The menu, filled with Matsuhisa’s blend of classic and contemporary dishes (all rather luxuriously rendered), also features a $225 omakase in what is naturally one of the city’s most fashionable dining rooms (for a certain loathsome sect). KŌMO would open in October of 2021 just a bit further east down Randolph Restaurant Row. The concept, a collaboration between longtime Chicago sushi chef Macku Chan (brother of Kaze) and Nils Westlind, offers an eight-course blend of kaiseki and omakase (nigiri being served at the end of the meal) for $160.

Frankly, you have never visited Sushi Suite 202, Nobu Chicago, or KŌMO and will refrain from speculating as to their quality. Rather, with Yume and Mako cemented as “Michelin-starred” establishments (now priced at $225 and $185 respectively) and Kyōten occupying the super-premium price point of $440-$490 (inclusive of service), none of these concepts seemed (to you) intent on competing at a citywide level within the genre of chef-driven omakase. Instead, they looked more like attempts to capture particular niches (in terms of price and type of customer) within specific neighborhoods. So, you ignored them, and you ignored The Omakase Room for a good year too.

The concept, nonetheless, took shape rather quickly. Or at least it seemed to. Who knows how long LEYE dreamt of better maximizing the Sushi-san space with some kind of premium offering? The company did not tease the idea or look to drum up any hype. It really, with the closure of Everest at the end of 2020, did not even seem interested in pursuing finer expressions of dining anymore. But all the ingredients, surely, were there to get in on the omakase boom. The market had become a bit saturated, but what competitor could boast a prime piece of River North real estate? Who else could count on a successful, casual counterpart (then open for a little over four years) to serve as the foundation for an omakase and mitigate most of the risk? The Omakase Room did not need to justify itself as a splashy opening in an (only recently) post-pandemic era—it just simply appeared.

LEYE, in a manner that has now become standard practice for companies like Hogsalt and The Alinea Group too, ensured its new property was totally finished and tied up in a bow before introducing it to the public. “The Omakase Room at Sushi-san Is Now Open,” read the February 7, 2022 announcement from the official blog. Eater trumpeted this reveal on the very same day: “Lettuce Entertain You’s Fancy New Omakase Spot Swaps Formality for Friendliness in River North.” Meanwhile, Robb Report published its own coverage just a few days later: “This New Chicago Sushi Restaurant Wants to Take the Stuffiness Out of Omakase.” Clearly, a narrative had been set (and happily parroted by “journalists” none too proud to regurgitate a tidy public relations dossier without offering any critical insight). LEYE, it seemed, would be inserting itself at the high end of the genre while simultaneously framing competitors as “formal” or “stuffy.”

The official announcement confirmed that The Omakase Room would, as with Sushi-san’s “Oma-Kaze” be under the command of “Master Sushi Chef Kaze Chan.” Vettel, writing for the Tribune, would term him “virtually a one-man history of Chicago’s sushi scene.” Born in Vietnam, Chan came to the city in 1995 and worked as “the original chef at Marai, at the time the best sushi destination in the city” when it opened in 1999. (Miae Lim, the restaurant’s owner, would later open Japonais in 2003.) Before that, he apprenticed at Restaurant Suntory in Boston (as an assistant sushi chef) and later “continued his culinary training under official Japanese Sushi Master, Shozu Iwamoto” (information on whom you are unable to find). Beyond Marai, Chan’s reputation was built at places like Heat, SushiSamba, Kaze, Macku, and Momotaro (where, notably, he served as opening head sushi chef).

Chan would be joined behind the bar by “Master Sushi Chef Shigeru Kitano,” who was born in Sapporo, Japan. Possessing a childhood love of “the culinary tradition and the bold flavors of the sushi,” he started his career by helping around “at a tiny restaurant owned by a family friend.” However, over a period of six years, Kitano made a place for himself and, upon leaving, went on to work as an apprentice for five different “Sushi Masters” over a span of ten years. “I learned a little bit from each one, and each one had a personal approach to sushi that I could respect,” the chef would say. Upon arriving in Chicago, Kitano would work at Hatsuana and Kamachi “for 13 years” before becoming the executive sushi chef of SushiSamba. “When I started at Hatsuhana, the ingredients were, like, frozen hamachi, and the selection was very limited compared to what I knew in Hokkaido,” he reflected, but now “he and Chan can get anything they want, straight from Japan.” Ultimately, Kitano describes his approach to the craft as “traditional” (something that keeps The Omakase Room “grounded” according to his partner).

The concept was framed by LEYE as being “meant to feel like a dinner party hosted at Chef Kaze’s home.” It would boast “world-class cuisine” built upon “daily fish deliveries, with a focus on wild line caught fish” and “the best ingredients from across the globe” sourced in “partnership with the Yamasaki family at the Toyosu Fish Market.” The space is “reminiscent of a modern loft” with both a “living room” lounge area and a sushi bar defined by “raised Japanese Hinoki cutting boards” meant to “provide unobstructed views” that facilitate interaction with the chefs. The announcement even references “partnerships with local ceramicists and stone masons to create one-of-a-kind service pieces” like the “custom-made Lazy Susans placed at each seat.”

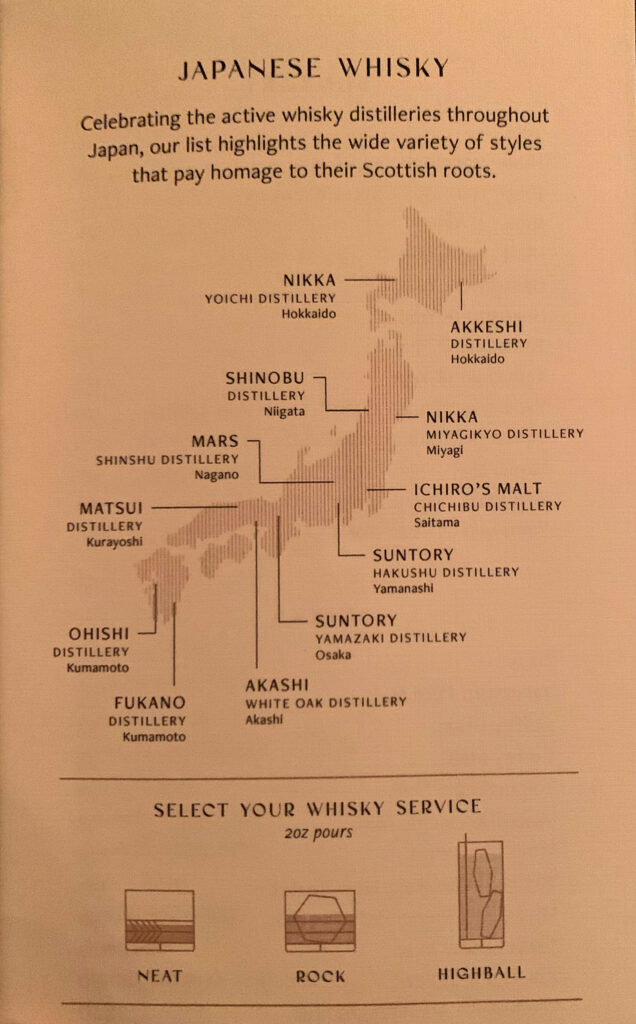

Accompanying the food would be a “highly curated beverage program” that joins together “award-winning Beverage Director Kevin Beary” (of Three Dots and a Dash and The Bamboo Room), “Sake Sommelier Daniel Bennett” (also a long-serving manager at Sushi-san), and “Wine Director Richard Hanauer” (who, in your opinion, has put together some of Chicago’s very finest lists at the various RPM locations). Notable offerings included “more than 100 bottles of whisky celebrating whisky houses throughout Japan,” “an extensive sake list,” and “hand-chipped ice” for drinks “influenced by refined Japanese cocktail bars.”

Via Eater, you would learn that “patrons…shouldn’t expect a traditional rendition of the [omakase] form: instead of a ritualized and generally silent performance, [the] chefs…will provide an entertaining experience with music and conversation alongside the ever-changing 18-course menu.” One of the restaurant’s partners would stress that “everything” about the concept “is designed to break down barriers between chefs and patrons.” The Omakase Room would showcase “items that are luxurious and made with craft and care” while looking to also demonstrate they are “not antithetical to being comfortable or having fun.” Much of that would be drawn from the aforementioned “unobstructed view” while seated at the sushi bar, meant to aid in “demystifying a culinary genre that some Westerners find intimidating.”

At the level of cuisine, Chan revealed he wants “to stay sharp and push the boundaries of the tradition-bound omakase he’s encountered overseas.” The chef, rather boldly, labelled omakase in Japan as “boring” and tasting “the same everywhere.” By contrast, he would weave in “the flavors he grew up with alongside other international influences” at The Omakase Room as part of a menu that will “change often—even daily.” “Combining things to bring out new flavors in the fish is fun for me,” Chan would say. “If I have an Italian or French ingredient—whatever I think is best for each different kind of fish—I’ll use it to bring out another flavor.”

Robb Report would echo many of the same sentiments, describing the “highly respected formality that goes into omakase-style dining” but noting it can “feel stuffy and intimidating to diners new to omakase.” Still, the publication offered a bit of nuance. The Omakase Room would be “hoping to redefine and demystify” the genre, to “make diners feel like they can really take part in the experience, not just be at the receiving end of it.” But this was not only framed as an appeal to sushi novices, forming a kind of remedial education that would bring them up to the standard of more worldly, “authenticity”-seeking connoisseurs. No, all that “pomp” and “reverence” may actually “feel unnecessary to diners accustomed to omakase [emphasis yours] who want a good time served alongside their nigiri.”

Seen this way, The Omakase Room was not just a bastardization of a tradition that had succeeded in snaring coastal, cosmopolitan Americans (ever eager to fetishize opaque imported customs and wield them against one another) but that largely went over the heads of those in flyover country. Instead, it represented—perhaps—the future of the craft. A future for the craft—at least—constructed reflexively in accordance with native tastes and not rooted in quelling status insecurity. In short, LEYE was betting that a more engaging staging of the experience would appeal equally to sushi neophytes as well as those who had scaled the heights of omakase (globally? nationally? locally?) and come to desire something less starkly ritualistic.

One of The Omakase Room’s partners would reveal that “the team traveled around the world, sampling traditional omakase experiences in Japan and some others closer to home like at Masa and Sushi Ginza Onodera in New York” as they prepared to open the concept. “We were blown away by what we saw,” he said, but they all “unanimously” wanted “an experience that was of that quality and of that standard, but that just felt more approachable, a little bit less formal.” The “respect for omakase dining in Japanese culture,” nonetheless, is something the restaurant is “very careful to uphold.” That is actualized through the care Kaze “takes with all of the ingredients, seeing the way he treats his knives, seeing the way he treats all of the items he brings in.” But “being respectful and being thoughtful and intentional shouldn’t be in the way of having fun and feeling comfortable.”

Elements like the “custom-made Lazy Susan” and “Japanese Hinoki cutting boards” would again be invoked. Yet the article also revealed that team “won’t know what a menu is for any given evening until that morning” and that they’re “writing menus almost up until guests sit down with us because fish are landing on our cutting boards that day.” Chan was particularly excited about the sayori (or Japanese halfbeak) because “no one else really carries that fish” due to its small size and many bones. The chef also noted how customers “want to learn a lot of things, about fish, about rice, how you cut the fish this way, how you cut the fish that way, why you serve this one first, why you serve this one last.” Educating them on these points does not only make Chan “happy” and “satisfied” with his work but will lead to greater “confidence” in the guest when they go to other omakases—invoking what they learned at The Omakase Room and “thinking about when they will be back.”

Ultimately, the restaurant wants “to make sure that every single thing that a guest experiences when they’re in the Omakase Room is the best in Chicago that night.” In short, they “want to be the best omakase in Chicago.”

The Omakase Room would open on February 10th, 2022—just three days after the concept’s announcement. It offered two seatings a night (5:30 PM and 8:30 PM) from Thursday through Saturday. That amounts to a maximum of 60 patrons who might enjoy the experience per week. (Kyōten usually can seat a maximum of 40 guests each week while Yume’s cap is 90 and Mako’s is over 150.) The ticket price was $250 (exclusive of 20% service fee and tax), a figure that remains the same today. That clocks in north of Mako ($185, exclusive of 20% service fee and tax) and Yume ($225, exclusive of gratuity and tax) but falls short of Kyōten ($440-$490, inclusive of service but not tax). LEYE, with the weight of all its resources, had clearly taken aim at the top of the omakase market. It leapfrogged the Michelin star holders in terms of entry price, promised a more engaging overall experience, yet could still seem like a relative value compared to the Alinea or Kyōten stratum of dining. And it was also worth asking: would the hospitality group’s economies of scale effectively erase the $140-$190 premium (and corresponding increase in quality) that Phan’s sushi entails?

Chicagoans would have to find out for themselves if The Omakase Room really delivered on everything touted in LEYE’s marketing copy. Steve Dolinsky, the ghoul of local gastronomy, would name the concept one of four “Restaurants for a Special Occasion” in June of 2022 without offering even a shred of insight on what he bizarrely called “Lettuce Entertain You’s homage to Japanese tasting menus.” Next, Chicago referenced The Omakase Room as part of its “Chicago’s New Sushi Wave” feature in August. It did not make it onto the “5 Omakase Spots You Need to Know Now” list (comprising Kyōten, Yume, Mako, Jinsei Motto, and Sushi Suite 202). However, Chan and Kitano would feature in the “Know Your Sushi Chef” article, being praised (relative to Jinsei Motto’s “Up-and-Comers” and Kyōten’s “Sushi Showboat”) as “The Sushi Masters” in town.

In September of 2022, the Chicago Tribune would award The Omakase Room two-and-a-half stars (“between very good and excellent” but short of “outstanding”). Nonetheless, Nick Kindelsperger’s article—”With The Omakase Room at Sushi-San, Lettuce Entertain You swings for the fences again”—cannot be considered professional food criticism due to the admission that “because of the cost, I only dined once for this review.” It is cute to see the “critic” contort himself to offer a meaningful (let alone valid) appraisal of Chan and Kitano’s work without any sense of the experience’s dynamism or consistency. But the piece frankly reads like LEYE propaganda when he references Everest, Tru, and “Anthony Bourdain visibly convulsing with pleasure…while eating at L2O back in 2009.” At face value, the hospitality group has hardly taken any risk in opening The Omakase Room (essentially a premiumization of the existing Sushi-san brand in an unused space). Rather than “swinging for the fences again,” the maneuver suggests something more like getting hit by a pitch (the sudden growth of the omakase genre at the hands of independent chefs) and taking first base (the easy money that comes from any scary new concept offered with the LEYE “seal of approval”). Kindelsperger’s analysis, in its fundamental superficiality and borderline corporate shilling, may be better suited to Yelp.

(The same goes for The Omakase Room’s appearance on the Tribune’s “25 best new restaurants in Chicago” list, where Kindelsperger weaselly terms it “an experience unlike any other in town.” You suppose that is what passes for “expertise” these days.)

In November, CS would highlight The Omakase Room’s sashimi as one of “Editor-in-Chief J.P. Anderson’s 8 Favorite Chicago Dishes Of 2022.” The piece would observe that “sushi is having a major moment in Chicago, with several world-class chefs calling the city home” but claim that Kaze Chan stands as the “best of the best.” He “masterfully executes an 18-course omakase menu in a 10-seat jewel box of a dining room” where “each course is a revelation” (but especially that sashimi trio). Time Out would put forth an almost identical blurb in December, explaining that “omakase-centric restaurants are so en vogue right now” but that few “match up to Lettuce Entertain You’s impressive 10-seat sushi counter hidden inside Sushi-san.” The Omakase Room would be termed “an exquisite, albeit expensive, meal that’s well worth saving your pennies for.”

This stands as just about all Chicago’s food media could muster to help guide consumers within a complicated and expensive genre. Nonetheless, at the time of writing, The Omakase Room can claim a five-star rating (based on 12 customer reviews) on Google and a four-and-a-half-star rating (based on five customer reviews) on Yelp. It also, as of just a couple days ago, can claim the number three spot on Chicago’s “Best New Restaurants” list (though, once more, the associated blurb barely offers any insight and cannot substitute for a valid review).

This certainly bodes well for LEYE, but sushi is a craft of fine degrees. Paying more should roughly (or is it hopefully?) correlate to higher quality fish displaying more nuanced texture and greater depth of flavor. Yet that extra lucre could just as easily be spent on totemic luxury ingredients (like caviar and truffles) that may make for enticing photos but often mask the character of the principal ingredients and, in doing so, preclude the kind of purity that should instead be prized. A higher price may also yield additional staff that, equipped with a robust beverage program and other creature comforts, enacts a kind of hospitality that complements (or is it obscures?) the chef’s craft. Consumers must ask themselves if they crave the very best sushi (at the level of sourcing and technique) or the very best “omakase experience” (at the level of presentation, interaction, and comfort). Of course, this is not strictly an either/or proposition, but it forms the basic orientation from which the evening’s expectations are drawn.

Those who prize the actual piece of sushi above all else may be interested in where the chef apprenticed, how often the menu changes, the rice they use, how they season it, where the fish comes from, how it is treated, who made the knives, how they are wielded (scoring etc.), and how all of these elements come together—via that mesmerizing prestidigitation—to produce a cohesive, superlative bite. Even if the itamae executes everything perfectly (a rather big “if”), this consumer must reckon with certain essential subjectivities like genetic differences in salt tolerance and one’s position on the hedonic treadmill. They must deduce if the chef’s palate more or less matches their own—or, perhaps, if the craftsperson would be amenable to adding a little more wasabi or a little less rice. Certain rudiments, like the character of the vinegar being used or the style and type of toppings, cannot really be changed outside of the itamae’s own experimentation. So, this kind of consumer must be able to sense that the chef exhibits a high degree of technique that also aligns with their personal aesthetic priorities. Then, they can ponder whether the premium this hypothetical “100-pt.” sushi entails forms an acceptable value proposition relative to the “95-pt.” or “90-pt.” examples available at a lower price. This is one train of thought that is worth pursuing as you evaluate The Omakase Room.

Those who prize omakase, first and foremost, as an intimate social experience and face-to-face encounter with craft operate in more of an emotional realm (one, no doubt, you are fond of). This does not necessarily make them chumps when it comes to cuisine. Rather, they affirm Marco Pierre White’s dictum that “service is more important than food” and, “if the environment is wrong, customers will not return to a restaurant.” These consumers are not worshipful sushi nerds looking to flex their knowledge but, rather, hosts who are status conscious for other reasons. They may be dining for business or pleasure, but they want to be impressed and to impress those whom they have invited. To this end, trappings and photo-ops are rather important, but these people are not always tasteless. Such a consumer desires warm, gracious service that makes their party feel special as it conducts the evening without a single false beat. They want to enjoy the shared wonder of watching a “master chef” work while still being able to toast and make merry. They want each and every desire to be anticipated so that the meal maintains a flowing rhythm and that the assembled guests can form the desired emotional connection. The difference between “90-pt.,” “95-pt.,” and “100-pt.” sushi is less consequential so long as the other pieces of the experience are in place and the food broadly tastes good. Consistency, rather than constant menu changes, may actually be a boon to those who do not want the evening blemished by experimentation. Omakase, to them, is about feeling confident and cultured as you share in a singular, memorable occasion. Any sense of “value” is constructed in accordance with how the evening feels and how that feeling compares to other restaurants of all stripes and even to concerts, plays, and other events. This is another train of thought that will inform your analysis of The Omakase Room.

With LEYE’s luxe sushi spot recently celebrating its first birthday, the time seems ripe for you to pay it a visit. In doing so, you will test the concept’s intention of making sure “every single thing that a guest experiences…is the best in Chicago that night,” as well as being “the best omakase in Chicago” and ensuring guests feel “it was an incredible value” too.

You have visited The Omakase Room a total of three times, spanning a period of January through March of 2023. As is usual, you will condense the sum of your experiences into one cohesive narrative.

With that said, let us begin.

Sushi-san sits on a relatively quiet corridor in the very heart of River North. But, sandwiched between Clark & Dearborn, the restaurant seems to fit naturally with the wealth of concepts that flow northward from the water. That includes LEYE compatriots like RPM Seafood, Steak, and Italian—to say nothing of Bub City, Beatrix, Three Dots and A Dash, Ema, Il Porcellino, Pizzeria Portofino, Ramen-san, or Lil’ Ba-Ba-Reeba! to boot. Yes, the Melmans have ensured that anyone eating along these particular blocks is likely to do so under their care. Yet Rick Bayless retains his small kingdom (Frontera Grill, Topolobampo, Bar Sótano, XOCO) and Carrie Nahabedian still has some presence there (via Brindille). NAHA, her former Michelin-starred establishment, is now home to José Andrés’s Jaleo outpost. Meanwhile, Tanta, Sunda, and Roka Akor each offer their own takes on sushi in close proximity too.

East of Sushi-san, heading toward Michigan Avenue, you come upon another collection of concepts: places like Yardbird, Eataly, Joe’s, Sugar Factory, Shake Shack, and The Purple Pig each interspersed within a dense mix of luxury hotels, foreign consulates, and shopping. However, north of the restaurant, the scene changes. You find the remodeled Rock N Roll McDonald’s—now the greenwashed “McDonald’s Chicago Flagship”—with its glass, shrubbery, solar panels, and ample parking. Portillo’s (now a shadow of its former self), Hard Rock Café, TAO, and Fogo de Chão also distinguish this area, which seems more geared to vehicular traffic (drawn from the Kennedy Expressway) than the wide range of walkable entertainment seen elsewhere in the neighborhood. West of Sushi-san, too, you hardly find anything worth talking about: salons, furniture showrooms, and a smattering of residential towers fill the space with only a couple restaurants (Le Select, Gene & Georgetti, Coco Pazzo) to speak of.

Close to the Merchandise Mart, of course, you find Hogsalt’s beachhead: Doughnut Vault, Gilt Bar, Ciccio Mio, and Bavette’s. But it is fair to think of Sushi-san as marking the northern boundary of LEYE’s extensive River North holdings. It signals where the concentration of concepts built north of the water—along and a bit above Kinzie—currently ends, where all the action begins to be funneled diagonally up the Magnificent Mile and into the Gold Coast. Apart from the aforementioned Joe’s (a place that, for you, surpasses any of the RPMs) and somewhere like Tzuco, this area holds little appeal for locals until you reach the Oak Street boutiques and Rush Street steakhouses (and, even then, this only attracts a particular demographic). Yes, Sushi-san is sort of the capstone of an entire hospitality district: the prime portion of River North that—loaded with a smaller proportion of national chains and still maintaining a good few superlative spots—can maybe hope to compete with the sprawling options in Fulton Market and on Randolph Restaurant Row.

However, taken in isolation, the stretch of Grand Avenue between Clark & Dearborn looks totally mundane. On the corner to the west, you find a three-star hotel that Marriott operates under its “Aloft” brand name. Beatrix, that most anonymous of all-day eateries, operates out of the ground floor with windows that open up onto the street. On the corner to the east, you find Mastro’s Steakhouse: an Arizona-based chain with a sizable presence across California. There, if guests happen to miss Sushi-san’s entrance and make a wrong turn, they might enjoy “Steak Sashimi” ($27) or a half dozen rolls ($22-$36) “developed exclusively for Mastro’s Steakhouse by Chef Angel Carbajal of Nick-San Cabo San Lucas.”

Smack dab in the center of the block stands the eight-story 57 W Grand building—“designed in 1912 by Huehl & Schmid to house the wholesale division of Remien & Kuhnert, a paint supply and wallpaper firm.” The façade’s red brick and white stone, topped with an attractive pediment, is offset by dark gray window fixtures that are matched by the design of the ground floor. In fact, this part of the building was renovated around 2012 in order to make its storefronts seem more subdued in a manner that matches the darker tones of the adjacent Mastro’s exterior. The work also uncovered the original “Remien and Kuhnert Co” engraving spanning the front of the structure (and that remains visible today).

Sushi-san occupies the former Osteria La Madia space at the western end of 57 W Grand. Its neighbor there is India House, whose original location opened in Schaumburg in 1993 and later expanded into Chicago a few years later. At some point (though when exactly you cannot quite tell), it changed addresses and ended up at the current spot. That was at least 15 years ago, for India House has been there long enough to merit a renovation (concurrent with the updating of the building’s façade) and continues to offer a popular $19.95 lunch buffet. Perhaps this provides some sense of LEYE’s closest competition: an interloping steakhouse, an Indian standby (with “over 250 menu items”), and the group’s own fast casual restaurant on the corner.

Across from Beatrix, Sushi-san, India House, and Mastro’s, the “Fort Dearborn” location of the United States Postal Service totally dominates its side of the block. Clad in brown brick and lined with associated gates, posts, cones, and trees, the building positively looks like a fortress. And, in its plainness, the structure saps most of the street’s energy. It precludes the development of any appealing stores or restaurants, marking the end of Clark Street’s action (unless one ventures further north in search of Ronald or Hard Rock). At the same time, it makes Sushi-San feel snug and, despite the neighborhood’s overall accessibility, just a bit out of the way from the main strip’s pulsating nightlife.

Approaching the restaurant’s revolving door ahead of your 5:30 PM (or 8:30 PM) reservation, the ground floor already looks to be in full swing. In the wake of the pandemic, Sush-san may not stay open until 1 AM anymore, but it does steady business from the start of dinner through closing (now 10 PM on Thursdays and 11 PM on Fridays and Saturdays). Pushing your way inside brings you to a small sliver of space with the host stand lying to your left and the hand roll bar to your right. One of the countless high-top tables that define the central part of the dining room sits directly ahead, so you turn and shimmy to make yourself small and stay out of the way while you wait to check in.

There are about 10 other people filling the same space at present. You maneuver yourself behind a cadre that has lined up to the side of the host stand. The rest huddle in the corner closest to the door—no doubt waiting for takeout orders or tables to become available. This scene can feel a bit overwhelming, particularly when the ingress or egress of other customers ripples through the assembled crowd. Nonetheless, Sushi-sans hosts and hostesses keep things moving. After giving your name, it only takes a moment for you to be whisked away from the door. On other occasions, one of the managers picks you out of the crowd upon arrival and precludes any need to navigate the other patrons altogether.

Being led through the restaurant, at this peak point of the evening, feels a bit like having a backstage pass. High-top after high-top, booth by booth, bar stool to bar stool, patrons sit clutching chopsticks and cramming maki down their gobs. Okay, it might not quite be so animalistic. But Sushi-san—with its moodily lit combination of light brown and black tones, its sparseness and maximization of seating—has always sought to be trendy. That is not even to touch on the concept’s “old-school hip-hop” styling (via the soundtrack, the “ice cubes,” or boombox-inspired to-go containers) or its invocation of emojis (via the “E-Mochi” desserts and bathroom signage). Rather, at core, the space is packed with bodies, buzzing with conversation, and awash with sake bombs while the open kitchen and sushi counter crank out a seemingly endlessly assortment of cutesy Japanese fare. It’s Nobu without the power brokers or the pretense, and it’s a thrill to wade through the action knowing you’re destined to slip through the back door.

There, in the corner by the kitchen and the sushi counter, you come to a door, then a stairwell, and climb up a few flights until you see a placard: The Omakase Room at Sushi-san. Stepping through yet one more door, you come to the restaurant’s lounge. This is where those who talk about “an experience unlike any other” start to salivate. To your right, you find the first seating area: a mix of exposed white brick, piping, and concrete with hanging glass lanterns, marbled tile, an abstract patterned rug, a wooden screen, and a couple planters (from which one tree nearly reaches the ceiling). There’s a long, low couch set against the back wall with a plush armchair and a cocktail table positioned on either side. This zone is bathed in warm candlelight and can be used to seat parties of up to six guests. More typically, it accommodates two sets of two that are amply spread apart along the couch and the chairs.

To your left, you find another seating area that has the distinction of housing the restaurant’s bar. To that end, the space is a bit less plush and a bit more functional. There’s another concrete wall with some piping and ventilation on display. The lighting comes not from lanterns but by a pair of wrought metal chandeliers each fitted with six bulbs. The bar itself is set against the rear wall; it boasts a wooden base with a gray-and-black top and a textured backsplash that vaguely matches the marbled tile. The surface holds a neat arrangement of mixers, tools, and ice bucket for the crafting of cocktails. The top of the bar features more than 40 bottles of Japanese whisky (only a small fraction of Sushi-san’s full collection) and a TV just above that. On either side stand shelves holding glassware, candlesticks, and other bric-à-brac. One lower level, however, holds a record player that is actually used to pipe music into the space.

In front of the bar, you find—to one side—a set of armchairs with accompanying cocktail table. To the other side, you find one additional low couch flanked by another set of chairs and tables. Candlelight, once more, ensures the setting feels intimate (if not downright romantic). But the most dramatic touch comes by way of a canvas replicating Andy Warhol’s Double Elvis [Ferus Type] but replacing The King’s head(s) with those of Daft Punk. The work sits above the low couch, meaning that those seated in the armchairs enjoy the best view. This helps prevent the composite from seeming too tacky or out of left field (for the French electronic duo has no obvious connection to the “old-school hip-hop” theme downstairs). Rather, this burst of pop reminds guests that LEYE wants this experience—even if it is on the luxurious side compared to the group’s other offerings—to be playful.

Overall, at an aesthetic level, you think The Omakase Room’s lounge is successful. The space is somewhat guilty of following in the next-gen Melman tradition of throwing a wide range of materials at the wall and seeing what sticks. It also constructs a kind of contemporary luxury that offers little to no sense of place. However, the design is smart in its avoidance of tacky Orientalism (that would only serve to invoke the sense of otherness LEYE is looking to avoid). Instead, it offers layers of detail that, even if they are somewhat senseless, serve to attract the eye. The furniture, likewise, is comfortable to sit in and spaced in a way that maintains privacy, allowing you to confer with your guests before the meal while maintaining the sense of a singular, shared encounter. The room, in short, really feels like a haven and cements a memorable transition from all the activity you witnessed downstairs. Its utility, nonetheless, is really demonstrated through your interactions with the staff.

Stepping into the lounge, you are warmly welcomed and relieved of your belongings. Given the modest number of diners at each seating, as well as the brief bottleneck that occurs when checking in downstairs at Sushi-san, LEYE manages the flow of patrons perfectly. Other parties may already be present—tucked away in their chairs with cocktails in hand—but the space, upon entry, feels entirely your own. This might have something to do with the profusion of candlelight, which allows you to get a sweeping view of the room without attracting anyone else’s eye. You may also peek through the curtain leading to the sushi counter—the promised land—that benefits from a more comprehensive lighting scheme. But a subdued mood certainly reigns: this is your carefully curated evening that just happens to be shared with a handful of mysterious strangers. You are not their entertainment, and they are not yours. Friendliness can certainly be abided, but intimacy—untainted by any contrived “dinner party” character—remains the order of the day.

The spatial contrast between the darkened lounge (backstage) and bright counter (front stage) is echoed by the service. Being led to your place on one of the couches or in one of the armchairs, you are offered a welcome drink: a delectably sweet nip of green tea and sushi rice horchata to meditate on for a moment. Shortly after, the server returns clutching the beverage menu. They are sure to note, when applicable, that you have already selected (and paid for) a pairing. They also warn that your stay in the lounge will be a brief one, and that you should feel no pressure to order anything during your stay. Just the same, the server springs into action should you desire a libation. Depending on your view, it might be mixed before your very eyes at the aforementioned bar. It arrives in short order and, should you not have a chance to drain it before dinner, will be transported to your spot at the counter on a silver tray.

By your measure, The Omakase Room’s lounge succeeds in adding to the dining experience on account of its restraint. Yes, everyone is offered that welcome drink, but it’s not nearly enough booze to really affect the palate. Rather, it’s a nicety—a frill—whose lilliputian size reinforces that this is only a waiting room. The staff does not ply you with any small bites, a gesture that you welcome in certain concepts but that, within the omakase genre, feels underhanded. (That is to say, mediocre chefs may try to frontload the menu with a few luxurious morsels in the lounge in order to get the hooch flowing, hit an early “peak,” and distract from the ultimate quality of their nigiri.) No, the sense of anticipation that builds with the ticket price, the walk through the downstairs dining room, and the first glance at the sushi counter is totally preserved. Not one grain of rice touches your lips until you are face to face with the chefs, and that superlative, magical moment is not spoiled by any heavy-handed attempt to make the lounge anything more than it is. This is worth appreciating, for it demonstrates how LEYE may enrich part of the experience (i.e., waiting for the meal to begin) while honoring the emotional underpinnings of the meal. Once again, the evening does not devolve into a frivolous “party” but strikes a careful balance between total comfort and a more considered (you would say rewarding) atmosphere of connoisseurship.

The front-of-house team, though programmed in the reliable LEYE fashion, certainly plays its part. The Omakase Room maintains a ratio of roughly one staff member for every two to two-and-a-half guests (not counting the chefs). That includes the sake sommelier you previously mentioned (also a manager) and one of the hospitality group’s partners, who oversees Sushi-san more broadly but leads its crown jewel from the front. (This partner also personally calls to confirm reservations, something that vexed you at first but—in this era of Tock text confirmations—is actually charming.) The remainder of the staff may not technically be management, but they bring the same sort of bearing and polish to their work. Snappily dressed (though not uniformed in any noticeable way), the servers have all the time and space they need to sense your particular energy and cater to it with some degree of sincerity. Of course, when dealing with the group’s frequent diners, the team will also have plenty of notes to draw on. But the interactions all feel natural (and, thus, canny).

At the same time, there is little question that Chan and Kitano are the stars, so the front of house knows how to be sharp and informative without (when you are later seated at the counter) ever stealing the spotlight. Instead, they ensure you do not go one moment with an empty glass or plate before you. They may even—as a reward for repeat patronage or upon ordering of a particularly exorbitant bottle of sake—share a pour or two from one of the pairings with you. In this manner, The Omakase Room’s team is equipped to be proactive, generous, patient, and pleasing in a way that blows many of Chicago’s other omakases out of the water. Certainly, LEYE possesses enviable resources to make this a reality, and the connection you feel is not quite the same as when you are hosted by the chef’s partner (or, perhaps, when they operate as something close to a one-man band). However, the restaurant is exploiting an advantage that its larger hospitality group has earned, and it is hard to deny the excellence of service that supremacy ultimately yields. The concept’s target audience (those who are not as inclined to fetishize an omakase free of any corporate imprint) is sure to be delighted by every interaction. You, yourself, cannot find any complaint, and it stands to reason that Bibendum will be quite a big fan of this staffing ratio too.

After spending what feels like only a few minutes in the lounge, you are invited to take your place at the sushi counter. Once again, there is no mad scramble or need to maneuver around the other patrons. Instead, the staff calmy approaches each party and guides them past the curtain and up a couple steps to their particular seats in a carefully synchronized process. You may, upon settling in, choose to greet your neighbors. However, while you have found the crowd to be friendly (particularly when couples are seated next to each other), most patrons default to a kind of performance mentality at first. That is understandable, for Chan and Kitano man their posts and greet each grouping upon entry. The chefs busy themselves with some final prep work, but the crowd waits on tenterhooks for all their anticipation to come to some delectable resolution. Making the transition from the warm glow of the waiting area into the bright light of the dining room proper drives the point home: you are on stage, and it is finally showtime. But what about the set dressing?

For its luxe omakase, LEYE has designed a space that is totally singular in Chicago. First, it is rather vertical, with high ceilings that draw the eye upward and prevent you from feeling cloistered. (Mako and especially Yume are guilty of this while Kyōten and even Sushi by Scratch cleverly avoid it.) Thus, while you might still be seated as close to the chef as anywhere else—while they might remain the center of attention—it feels like there is a bit more breathing room. Your eyes can wander. You can disengage. It still feels like you are out on the town and not stuffed inside a jewel box that leaves no other option but to observe the sushi ceremony reverently.

More specifically, The Omakase Room’s counter is defined by a ribbed, wooden base whose dark brown tone and texture matches the housing of the range hood that hangs on the wall behind the chefs. The functional nature of this installation is well hidden, for it also displays the restaurant’s logo (a sleek spiral pattern) at the dead center point of the dining room. Above the hood, the room’s ceiling is cut out—providing another touch of darkened wood. Down from it hangs a track of lighting, done in the same color, that traces a path around the U-shaped bar. Likewise, the black marbled tiling (seen throughout the lounge) remains. However, the wooden surface of the counter, the room’s walls, and the portion of the ceiling that is not indented are all rendered in whitish (sometimes bordering on light gray) tones. This contrast sounds stark, but it actually helps to frame your field of vision while accentuating the chefs, their tools, and the many enticing hues of their fish.

Honing in on some of the finer details, you might start with the chairs: barrel-shaped with a tannish color (perhaps meant to match the cutting boards) and velvety upholstery that all swivels on a stainless-steel base. This makes for solid, adaptable, and totally refined seating that easily surpasses the comparably humble furniture at The Omakase Room’s competitors. Facing forward, you may also note the attractively worn wood of the chopsticks, their gilded holder, and the ribbed metal coasters used to hold water or cocktails. The restaurant’s glassware, on that note, is slender and minimalist (so as not to get in the chef’s way) but feels pleasing in the hand and suits its purpose well (like the stemmed, tulip shape used for sake). The much-touted “custom-made Lazy Susan” lies toward the far end of the counter, its finish vaguely matching the style of the restaurant’s tiling.

Just beyond the edge of the surface, Chan and Kitano’s work area sits a few inches beneath the sushi bar. It comprises the aforementioned cutting boards along with accompanying knives (with gilded handles), chopsticks, graters, and a variety of painted ceramic vessels containing various garnishes. Each of these latter items is daintily arranged and serves to offer an additional burst of color when set against the grayscale backdrop. Behind the work area, underneath the range hood, you find a couple stovetops, a konro grill, a toaster oven, and a torch that are wielded when necessary in the preparation of certain nigiri. Adjacent to this station—at the end of the U-shaped counter that touches the wall—you find a small flower arrangement whose yellow, green, and red tones outshine anything else in the space. Its effect, nonetheless, is carefully managed by placing the composition somewhat out of the way.

Overall, The Omakase Room’s sushi counter is successful, like the lounge, on account of its restraint. Kyōten may feel a bit more luxurious (though whether other aspects of the experience live up to that veneer is a fair question) and a place like Sushi by Scratch more memorable (in a hidden underground lair kind of way). However, Chan and Kitano preside over a room that feels sleeker than Mako (probably its closest match at an aesthetic level) and more comfortable than Yume. LEYE’s choice of fairly bland contemporary styling fits with the design scheme they have popularized at places like the RPMs. It matches a desire to transcend omakase’s stereotypical association with wood (and lots of it) to please patrons that are not inclined to wholeheartedly worship tradition. At the same time, the space features plenty of little touches that show a glimpse of the concept’s (or is it the chefs’?) personality. Most importantly, lighting, color, and sightlines combine to ensure the counter really feels like a stage. This empowers patrons to take in every aspect of the performance and indulge in the kind of interaction LEYE felt was missing from the genre.

As you acclimate yourself to the sushi counter, one of the servers offers to bring a stand for any purses in search of a hook. They ask your choice of water and, should you not have already selected a pairing through Tock, inquire if you would like something else to drink. (On one occasion, a lone diner seated next to you elected to stick with water. The reaction of the staff—though this should be expected—was totally gracious and affirms that LEYE does not view the space, however luxe, as a “hard sell” environment. You cannot say the same for Masa.)

The preface to The Omakase Room’s beverage list defines the program using the words “care” and “delight.” They reflect “what you can expect” from the offerings, “all carefully curated to guide you through your omakase experience” and comprising everything from “pours of Japanese whisky and cocktails with hand-crafted ice” to “adventurous and novel sake pairings.” The introduction ends on its own reverential note: “we are honored to share what we love with you. We hope you enjoy them as much as we do.”

The selection starts off with a set of four cocktails from Kevin Beary of Three Dots and a Dash/The Bamboo Room. There’s the “Borrowed Brass” ($19), made with Blanco Tequila, Espadin Mezcal, White Port, and Pandan; the “Japanese Old Fashioned” ($24), made with Yamazaki 12, fresh banana, and Okinawa sugar; the “Guilty By Association” ($16), made with Pineapple-steeped Armagnac Blanche and cold-pressed honeydew melon; and the “Strawberry Highball” ($16), made with Junmai Daiginjo sake and the titular fruit. The pricing on these drinks may seem high at first glance, but it actually accords with Mako (its three cocktails running from $17 to $25) and Jinsei Motto (where all 14 of its options cost $17). Neither of these restaurants, however, can count on the talent of a beverage director like Beary—whose concept The Bamboo Room earned the “Campari One To Watch Award” at North America’s 50 Best Bars 2022.

While the “Borrowed Brass” tastes a bit too rich and boozy for a tequila/mezcal cocktail that occupies the top spot on the menu (especially when an old fashioned is already offered), the “Guilty By Association” is a delight. It displays the kind of pure, refreshing, fruity quality that you most enjoy along with ample acidity and a ripe, rounded finish. This allows the drink to function perfectly as an apéritif without blowing out your palate and detracting from the delicate seafood to come. You count it among the best cocktails you have sampled this year, and one that really lives up to Beary’s estimable work in the tiki world.

Moving on, you find a pair of spirit-free cocktails that also appear as part of the restaurant’s “Spirit Free” pairing ($65). The latter offering features the following blurb: “our premium, zero-proof craft cocktails maintain their complexity and depth from tea-derived infusions—a sophisticated beverage experience delivered in partnership with Rare Tea Cellar.” À la carte, the drinks are titled “Freak Flag Flying” ($14), made with Freak of Nature Oolong, melon, and pandan, and “Strawberry Lapsang Old Fashioned” ($13), made with Lapsang Souchong and a strawberry cordial. You have sampled both of these as part of the aforementioned pairing and think they are nicely made, offering an appealing weight and texture on the palate while nicely balancing sweetness and complexity. Rounding out this section, you find four additional loose leaf teas: the “Sakura Dream” ($15), “Emperor’s Dattan Sobacha” ($7), “Freak of Nature Oolong” ($11), and “Emperor’s Gyokuro” ($9).

While these libations are fine and dandy, wine—for you—always forms the main event, and sake, too, should be given due consideration within this genre. Patrons are first met by a page featuring the various pairings. Apart from the “Spirit Free” option you just discussed, these include “Sake” ($95), described as offering “refinement and subtlety”; “Wine” ($150), described as a “bolder pairing”; and “Wine & Sake” ($175), which offers “the delicacy of sake alongside the richness of our wines” and “meet[s] the meal with power and poise.” At a structural level, you really like this pricing scheme. It ensures that those seeking the cheapest turnkey solution will likely opt for the “Sake,” which—for an audience that might not have much experience with the beverage—brings a sense of novelty to the experience. By pricing the dedicated “Wine” pairing a bit higher, LEYE ensures they can offer “world-class wines from a variety of terroirs” rather than cost-effective bottles guests might recognize from elsewhere. The “Wine & Sake,” meanwhile, does not look to occupy a super-premium price point but simply allows the restaurant to offer the “best of both worlds.” This idea particularly rings true when you are served both a wine and a sake to alternate between upon reaching the meal’s tuna- and wagyu-fueled crescendo. Overall, in their degree of specialization, these four options compare favorably to the lone pairings offered at places like Mako ($95) and Kyoten ($140).

Personally, you have only sampled the “Wine & Sake” pairing. On that occasion it comprised:

- 2017 Moussé Fils “Spécial Club” (Les Fortes Terres) Champagne (Pinot Meunier)

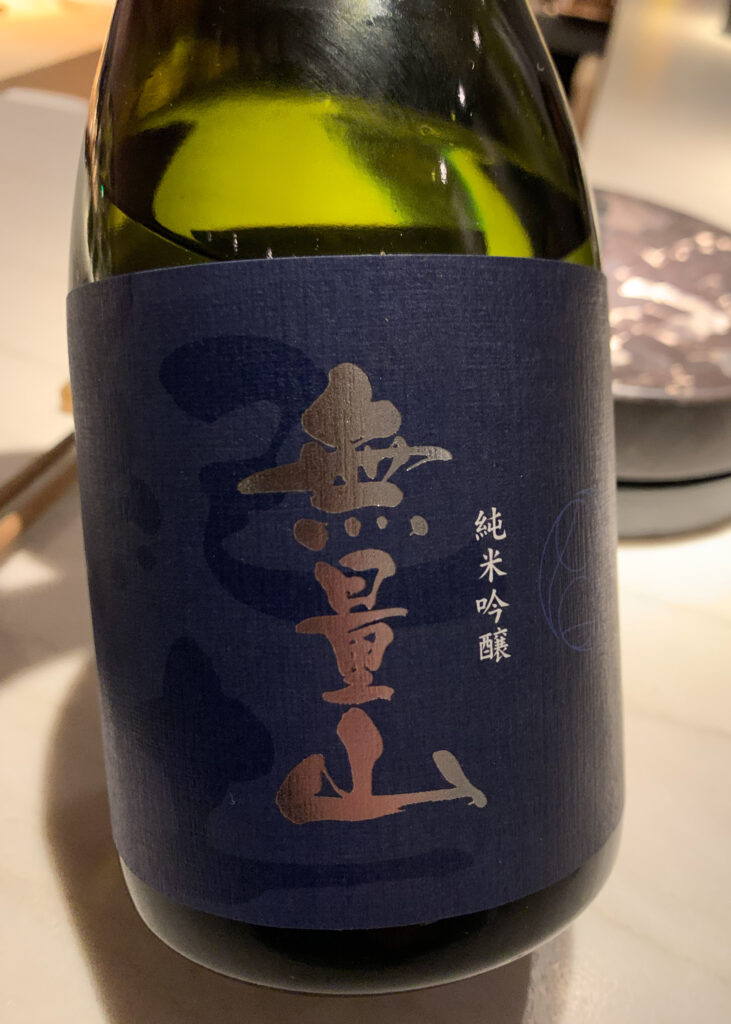

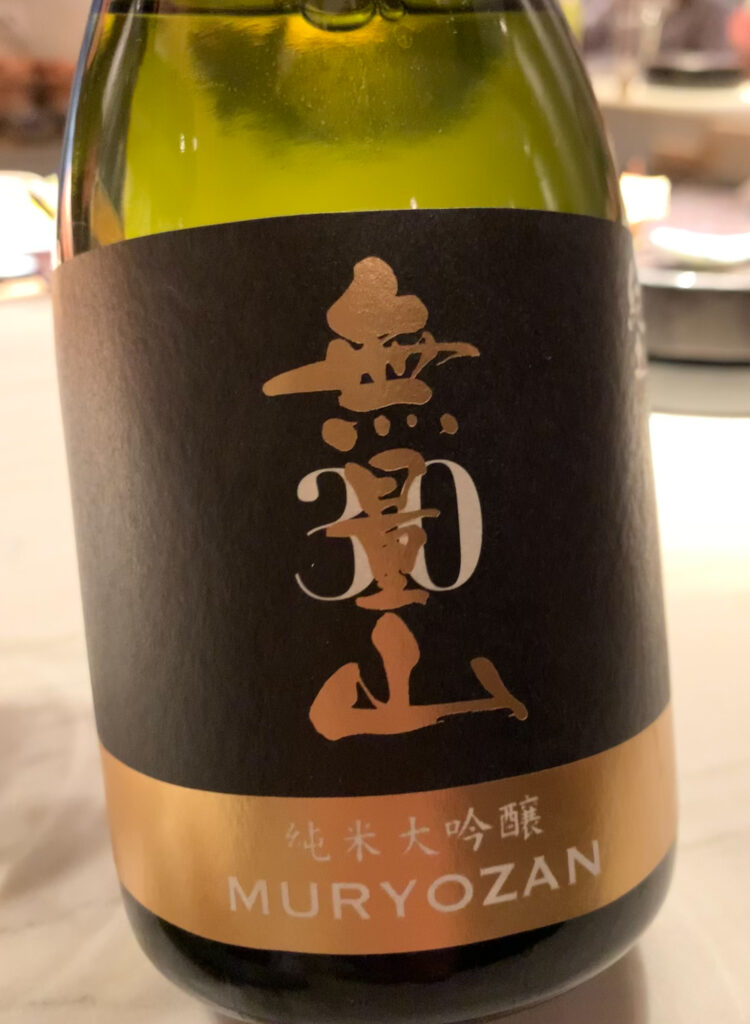

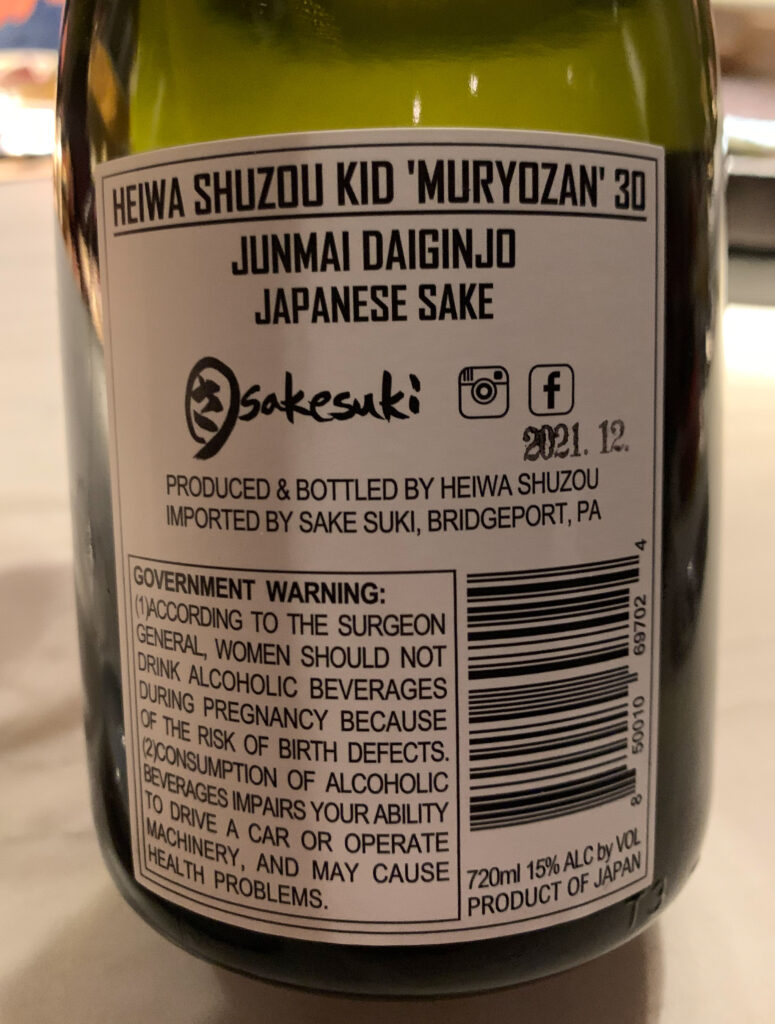

- Heiwa Shuzou KID “Muryozan” Junmai Ginjo

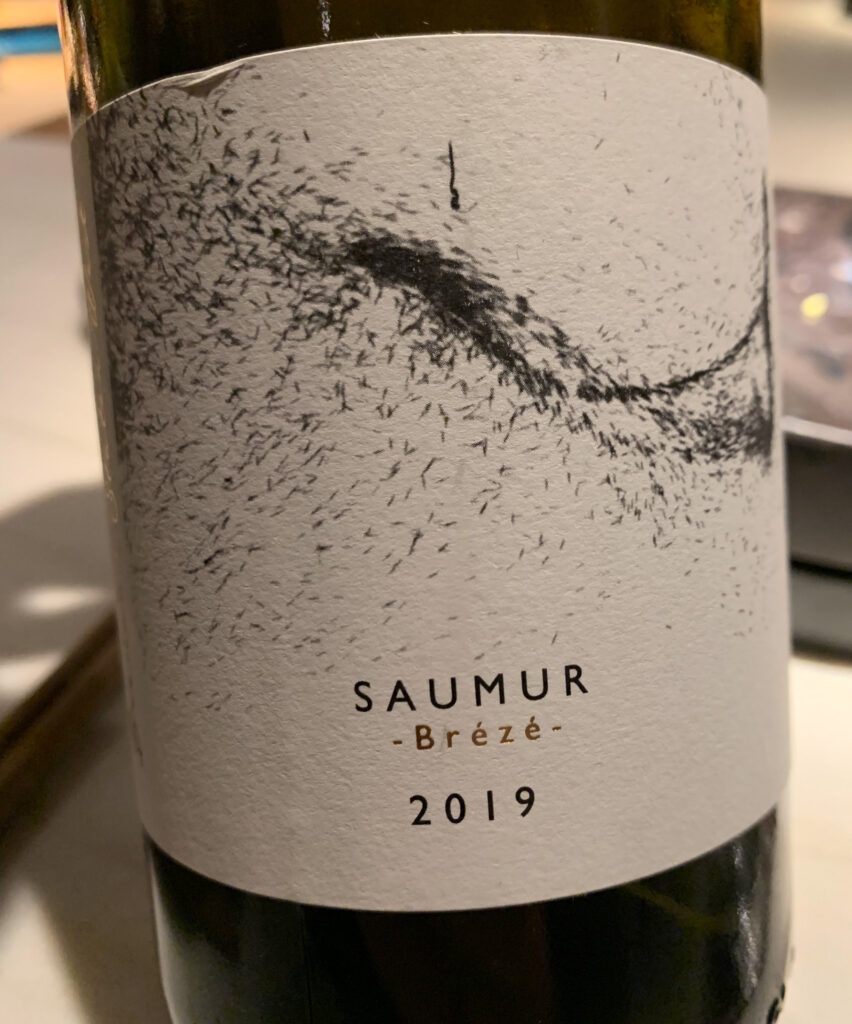

- 2019 Brendan Stater-West “Brézé” Saumur Blanc (Chenin Blanc)

- Afuri “The Kimotology” Junmai Daiginjo Kimoto-Jikomi

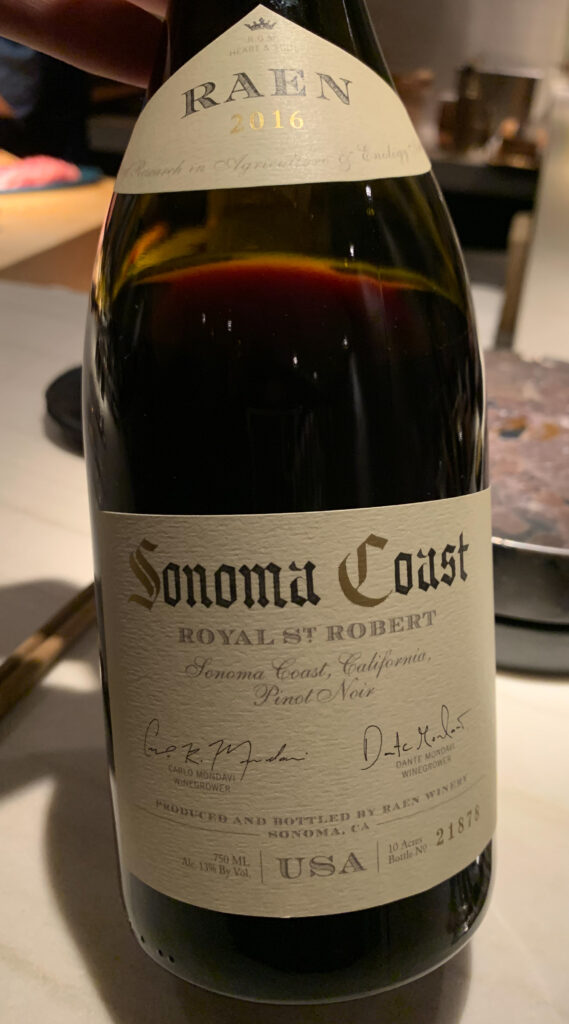

- 2016 RAEN “Royal St. Robert” (Pinot Noir)

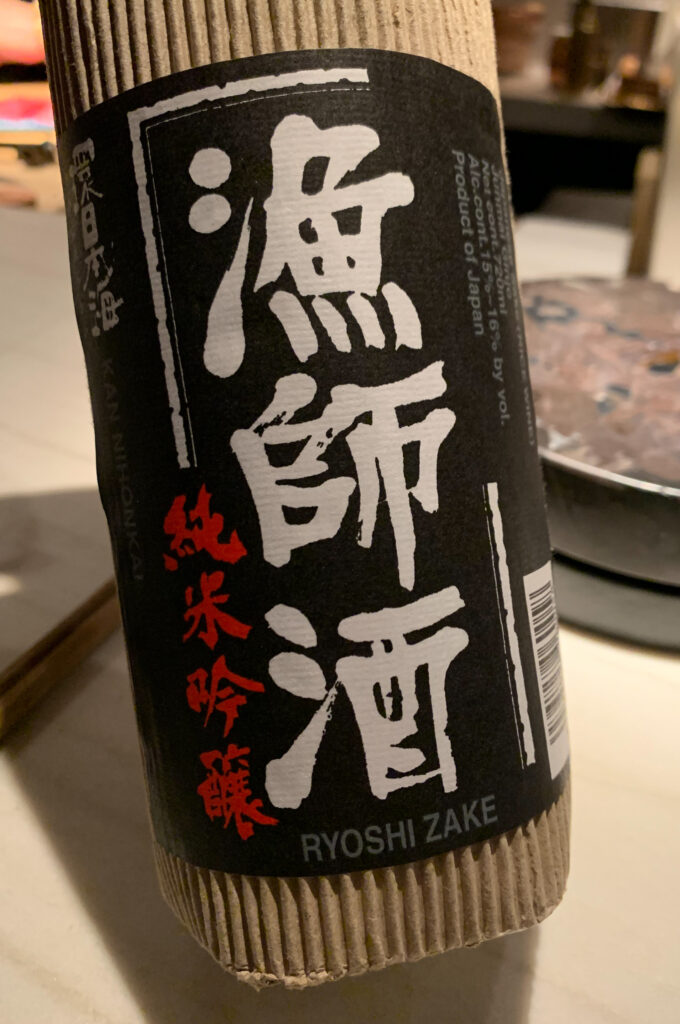

- Kan Nihonkai “Ryoshi Zake” Junmai Ginjo

- 2017 Royal Tokaji 5 Puttonyos Tokaji Aszú

While you lack extensive reference points when it comes to sake, you left feeling impressed by what you were served. Moussé Fils, Brendan Stater-West, RAEN, and Royal Tokaji are each noteworthy producers, and grapes like Pinot Meunier and Chenin Blanc deliver exceptional value while still feeling familiar (compared to a Pinot Noir-based Champagne or a still wine made from Chardonnay respectively). Lovers of Burgundy may turn their noses up at Carlo and Dante Mondavi’s RAEN project, but you enjoyed the 2016 Royal St. Robert’s purity of fruit and overall elegance. Its substantial acidity paired nicely with the fatty tuna without obscuring one bit of the fish’s character. You would also say that the first two sakes, as best as you can describe them, each featured refreshing acidity, supple texture, and a mild sweetness that made them rather easy to drink. Even the bolder “Ryoshi Zake” served (alongside the RAEN) with the tuna and beef offered greater weight and complexity without seeming jarring or alcoholic.

Ultimately, the bottles that make up the “Wine & Sake” pairing land in the $50-$100 range with an average price of around $70 retail (though you are excluding “The Kimotology” since you cannot find it listed domestically). Considering these bottles would cost double or even triple with a standard restaurant mark-up, you think seven pours of wine and sake of this caliber at a price of $175 feels fair. The front of house team, to their credit, is also empowered to offer a refill or two when necessary.

Moving over to the next page, you come to the “Sake by the Glass” selection:

- Wakatake “Demon Slayer” Junmai Daiginjo ($15)

- Eiko Fuji “Glorious Mt. Fuji” Junmai Ginjo ($20)

- Sohomare “Tuxedo” Junmai Daiginjo ($30)

- Heiwa Shuzou “Tsuru-Ume Suppai” Umeshu ($15)

- This is followed by the “Wine by the Glass” section:

- 2017 Moussé Fils “Spécial Club” (Les Fortes Terres) Champagne ($35)

- 2020 J.M. Brocard Chablis “Fourchaume” 1er Cru ($19)

- 2020 Shea “Shea Vineyard” Willamette Valley Pinot Noir ($19)

While the entry price for a single glass of sake or wine seems high, these options compare favorably to Jinsei Motto (where sake ranges from $10-$22 and wine from $16-$26), Mako (where sake ranges from $12-$18 and wine from $15-$25), and Yume (where carafes of sake range from $45-$69 and glasses of wine from $21-$22). Still, it is worth mentioning that Jinsei Motto (21 sakes, 12 wines), Mako (7 sakes, 9 wines), and Yume (6 sake carafes, 2 wines) generally offer a broader by-the-glass selection than The Omakase Room (significantly so in the case of the first two).

In terms of direct price comparison, the “Demon Slayer” that costs $15 a glass from LEYE is listed for $17 at Jinsei Motto. There is no other overlap you can find between the by-the-glass beverages offered at The Omakase Room and those found at the city’s other restaurants (and this sole difference of just a couple dollars means little when diners at Jinsei Motto are so spoiled for choice). Instead, what’s important is that LEYE, despite occupying the upper price stratum within this particular genre, does not squeeze its customers for every cent. You can get a totally serviceable glass of Junmai Ginjo, Junmai Daiginjo, Chablis, or Pinot Noir for only $15-$20 and, say you enjoy two or three of those throughout the meal, get out the door spending less than you would on the cheapest alcoholic pairing ($95). This also holds true when ordering the J.M. Brocard or Shea by the bottle ($76), ensuring diners who might shy away from trying sake can enjoy a large serving of a familiar and accessible grape variety without feeling punished.

Only the $35 Moussé Fils “Spécial Club” Champagne seems priced in a predatory range (given the pride of place that sparkling wine maintains as a celebratory beverage). However, The Omakase Room’s choice of producer outclasses the bottles offered by its competitors: the Canard-Duchêne ($23) and Charles Heidsieck Reserve ($25) listed at Jinsei Motto; the Moutard “Rosé de Cuvaison” ($18) and Vadin-Plateau “Intuition” ($25) listed at Mako; and the Delamotte half bottle ($65) listed at Yume. At The Omakase Room, for that extra $10 sum, you get a vintage wine (2017) from a well-known grower-producer (Moussé Fils), that also qualifies for the prestigious “Spécial Club” designation (meaning the bottle represents the house’s tête de cuvée). In this manner, rather than serving just any old Champagne that would fit the bill, LEYE has chosen something superlative to offer by the glass. That demands guests pay a bit extra to get in the door, but they will be treated to a wine that does far more than meet the mere expectation of being bubbly. Perhaps that is why the Moussé Fils was included as part of the $175 “Wine & Sake” pairing too.

Compared to the by-the-glass sections, where a restaurant must privilege the tastes and spending habits of entry-level consumers, the bottle list offers an opportunity to really demonstrate what the beverage program is about. In LEYE’s case, expectations are particularly high: the group already manages several of the city’s most extensive wine programs and touts the presence of a “sake sommelier” here at The Omakase Room to boot. Thus, you expect to find the same depth and quality of choices (as, say, an RPM property) whether you are seeking something made from fermented rice or fermented grapes. And, at the same time, you expect a group of LEYE’s size and resources to pass a certain degree of value on to consumers (especially when compared to its relatively “mom-and-pop” rivals). Exploiting these intrinsic advantages would form a huge feather in the restaurant’s cap when it comes to attracting connoisseurs (while falling short, likewise, would make you wonder why they entered the genre to begin with).

You will start by looking at the “Sake by the Bottle” selection:

- Taka “Noble Arrow” Junmai ($95)

- Tamagawa “Heart of Gold” Daiginjo ($135)

- Shindo “Reception” Junmai Daiginjo Muroka Nama ($155)

- Heiwa Shuzou KID “Muryozan” Junmai Ginjo ($180)

- Hakkaisan “Awa” Sparkling Daiginjo ($190)

- Sawanoi “Hojo 35” Daiginjo ($275)

- Okunomatsu “Ihei” Shizuku Daiginjo ($350)

- Kuheji “Kurodasho Tako” Junmai Daiginjo Genshu ($350)

- Yuki no Bosha “Morning Flower, Evening Moon” Daiginjo Genshu ($450)

- Yuki no Bosha “The Sound of Snow” Junmai Daiginjo Genshu ($800)

- Heiwa Shuzou KID “Muryozan 30” Junmai Daiginjo ($895)

It is easy to feel a bit of sticker shock when you realize that more than half of the options come in at over $275. Chicago restaurants have not traditionally sold sake of this caliber, and even wines approaching $1,000 are sure to raise a few eyebrows when they mingle with more humble libations on such a short list. Jinsei Motto, for reference, sells 16 sakes by the bottle (ranging from $45-$130 and averaging $92.69), and Yume sells 9 of them (ranging from $60-$265 and averaging $144.78).

Mako, actually, offers the best point of comparison. B.K. Park sells 10 sakes by the bottle (ranging from $95-$850 and averaging $283), which comes quite close to The Omakase Room’s average of $297.33 (that includes the four bottles offered in the by-the-glass section for $115-$220). Even more interestingly, Mako sells the Yuki no Bosha “The Sound of Snow” for significantly less ($625) than the $800 charged by LEYE. So, does this signal that The Omakase Room’s list is just a needless money sink?