Following your recent exploration of the omakase genre, it seems natural to keep your palate trained on the craft of sushi. Nigiri, sashimi, maki, and the like are defined by small degrees: intricacies of flavor and texture that are more easily judged with reference to some other restaurant. Plus, the price stratification within the genre—it must be said—invites comparison. Any chef working in this format will have their fish and rice (and overall experience) measured against the city’s other options as consumers look to discern the right sweet spot for their palate and pocketbook. Thus, it is always worthwhile to lay some of the groundwork for other diners—to dig into the essential differences that define each concept in the rigid (relative to fine dining writ large) world of omakase.

Sushi by Scratch Restaurants is Chicago’s newest entry in the genre, having only opened in February. The concept—with other locations in Austin, Los Angeles, Miami, Montecito, and Seattle—is an import. It’s one of those businesses that, like Sushi Suite 202, reimagines “underutilized spaces.” Your first instinct was to turn your nose up: why bother investigating this disposable interloper when local chefs, manning the same counter each evening, are better worth supporting? The Windy City has no need of opaque national luxury brands when omakase, at its very best, should offer an intimate, singular encounter with a craftsperson who owns and operates the enterprise.

Nonetheless, Sushi by Scratch Restaurants’s Montecito location earned a Michelin star in 2021 and 2022. That pedigree would ensure the restaurant, in a Midwestern city lacking many Bibendum-approved examples of the craft, made a splash when it opened its doors concurrent with this year’s Valentine’s Day celebrations. The omakase has immediately become one of Chicago’s toughest reservations, with all of April’s tickets (save for a couple spots for single diners at 9:30 PM) selling out within a couple days of release and May’s tickets, even more impressively, being depleted in just a couple hours. That amounts to something like 660 seats (each month) that have been filled while Mako, touting its accolades and home-field advantage, struggles to fully book (not counting its tables) a fraction of that. John Shields—the most influential chef of the city’s post-Trotter, post-Alinea era—has given Sushi by Scratch Restaurants his stamp of approval (at least in terms of posting an Instagram story). And the concept, as you dug into its history more, can actually claim some intimate connection to its newest home.

But where to begin? Well, with Phillip Frankland Lee of course—Sushi by Scratch Restaurants’s chef/owner (alongside wife Margarita Kallas-Lee). Like any good founder of a sprawling luxury brand, the man is a living, breathing billboard for his business: a tatted, bearded, timepiece-clad impresario of new-age gourmandise. Lee is polished, no doubt about that. Some might even say charming (and understandably so). He competed in the 13th season of Top Chef, finishing in eighth place, and can count a dozen appearances (both as contestant and judge) across the Guy Fieri properties Guy’s Grocery Games and Tournament of Champions. Throw in a couple spots on Cutthroat Kitchen and Chopped, and you have the makings of a chef that is enviably media-savvy.

You do not fault Lee for being a gifted entertainer (a trait whose increasing importance, vis-à-vis modern chefdom, Gordon Ramsay reminds of us with every passing year and subsequent Botox injection). In fact, showmanship runs in the family: the chef’s mother is an acting coach, his biological father is a musician, and his grandfather (whom Phillip was named after) was two-time Emmy and Tony Award winner Phil Silvers (known as “The King of Chutzpah”). True to form, Lee—“who began acting in commercials as a child”—was characterized by some as “this season’s villain” when he appeared on Top Chef. You cannot say you’ve watched the show yourself, but it is worth mentioning that the contestant claimed his biggest competitors that season “were the judges, or whoever it is that decides who wins and loses.” Lee felt his biggest challenge on the show was “knowing that no matter how hard I would try or how good I would cook, I was not going to win.”

This is hardly the kind of attitude Chicagoans associate with local Top Chef stars like Sarah Grueneberg (of Monteverde) or Joe Flamm (of Rose Mary). Yet, in a way, you also sympathize with Lee. Reality television has little to do with reality, and you are not sure Bravo’s longstanding judges have done anything to establish a sense of credibility beyond occupying their positions (and associating themselves with actual talented chefs) for so long. They, as conductors of the show, are entertainers in their own right. Provoking a contestant that is already prone to self-aggrandizement seems like a surefire way to secure that most delicious of audience segments: hatewatchers. And Lee, to his credit, has not harped on about his Top Chef experience all that much since. The chef can be forgiven for voicing his frustrations (well-founded or not) in the immediate aftermath of elimination.

Yet, since Lee has such a nicely manicured media profile these days (one which you will engage with in just a moment), it is worth dwelling on just one more salvo of criticism courtesy of a fellow anonymous food writer. You do not do so out of any personal dislike for the chef (an impartiality that this particular author, you believe, shares). Rather, the power of public relations ensures that any meaningful critique of any given career, unless someone’s conduct is inescapably controversial, finds itself effectively buried under a mountain of fluff. Criticism should not trade in gossip, but consumer advocacy should also not rely upon “official” narratives spun by “journalists” who have a vested interest in pumping out bland promotional content spoon-fed to them by marketing professionals. So long as Lee is able to spin his tale the way he wants within this article, it seems fair to engage with an intelligent counterpoint. This seems like the only way to ensure that chefs are not unduly advantaged by their media mastery, a dimension of the craft that—in your perfect world—would not exist.

According to this more critical perspective’s reading of Lee’s time on Top Chef, the Sushi by Scratch Restaurants honcho was, indeed, the victim of editors who “really condense[d] all of his worse [sic] traits and statements that are usually a bit more spread out.” The chef can be forgiven for being “a bit prone to grandiose drama” and “thus obviously a self-promoter.” However, the writer—who claims to have “done either detailed profiles, dish stories, Q & A or first job stories with a number of other former Top Chef contestants” argues that Lee’s “inability to take constructive criticism is a real trait, not just editing for TV.” Further, rather than being “open and responsive to constructive criticism,” he “likes to portray himself as a victim to generate sympathy, which in turn only generates something a lot worse than honest criticism…false praise.” This leads to a “grandiosity and bombast in particular about his culinary abilities” that, in the author’s opinion, “are very mediocre.”

These negative traits ultimately work to shield “Lee’s other huge downfall,” a “lack of substance.” During the course of the season, the chef’s “constant mentioning of…doing food from his restaurants” was not just “self-promotion.” These “incessant comments,” it is argued, served to mask “very limited culinary skills.” Lee “really doesn’t know how to cook much other food than what he’s already cooked in his restaurants” because “he never spent enough time in other chefs’ kitchens to gather a wide array of culinary tools.” Instead, he rushed “to open his own restaurants” and do “whatever he wants.” Ultimately, it is claimed, Top Chef only kept him around so long “for production value.”

The real teeth underlying this criticism—and certainly its most speculative and provocative aspect—has to do with Lee’s actual restaurants. The author argues that the chef’s first concept, Scratch | Bar, “was originally a collaboration…[with] two other chefs, Joel David Miller and Ryan Duval.” When “Lee’s mother gave him the money to partner with Lee’s original business partner in Beverly Hills and place this concept [later moved to Encino] in that business partner’s existing restaurant, Lee took ownership of the concept and made it about himself.” At that point, “Miller became the chef de cuisine and Duval the sous for a year before they left and took the entire kitchen crew with them to The Wallace in Culver City.” From this author’s perspective, “Miller and Duval conceived, developed and cooked most of the better dishes at Lee’s restaurant” while the latter chef “seems to prefer schmoozing in the front of house rather than working the pass or on the line in the kitchen.”

You still question whether it is fair to include this kind of speculation within your article and can only really stomach doing so because its author writes so prolifically on more highbrow food topics. You also did not stumble upon this (admittedly somewhat hack psychoanalytical) perspective until you had already visited Sushi by Scratch Restaurants twice and, subsequently, maintain your initial opinion that Lee is a talented performer. However, if you are to write the most piercing analysis possible, it seems right to ask if he is an entertainer masquerading as a chef. This should not, in the interest of being fair to Lee, be all that hard to disprove if his sushi shows even a glimmer of quality. But, to reiterate, it also seems like the fairest posture from which to judge the work of a professional that seems to have enjoyed certain advantages his fellow craftspeople have not. Chicago, certainly, should never allow interlopers with concocted reputations to steer its dining scene toward an appreciation of frippery. Nonetheless, you will table all this cynicism for now and engage with Sushi by Scratch Restaurants’s narrative as Lee tells it.

As the story goes, Phillip Frankland Lee grew up “as an avid eater in the valley of Los Angeles.” The “earliest memories of his love of food” can be drawn “from a home video of his 3rd birthday.” Therein, the future chef’s father tries “to justify to his mother why he bought his young son a chef’s knife,” relenting that “I don’t know what else to get him; all he likes to do is cook.” Lee would grow up “in California’s San Fernando Valley as the oldest of six children” and the one that would handle all the “kitchen chores.” This “instilled in him a sense of purpose and a love of cooking at an early age,” one that would eventually lead him to drop out “of high school to be in a band and find a way to pursue his passion” for cuisine. He “attended Le Cordon Bleu College of Culinary Arts in Pasadena” but “left after three months, feeling that real world experience in the restaurant business would best suit his short-term goals.”

Thus, Lee “began his career as a dishwasher [for his godmother’s catering company] at 18 and quickly rose from the ranks working under some of the best chefs in the country.” That included Quinn Hatfield, whose restaurant Hatfield’s earned a Michelin star in 2009 as part of Bibendum’s short-lived (now restored as part of a broader California edition) Los Angeles guide. Lee also worked for Stefan Richter, runner-up on season five of Top Chef. Through these experiences, the future Sushi by Scratch Restaurants proprietor “became a Sous Chef at 21” He decamped to Chicago in 2010, working as a chef de partie under Laurent Gras at L2O then “completing a stage at Alinea” and helping the group open Next.

In the fall of 2011, Lee returned to Los Angeles looking to apply his “training and experience” within “what he saw as a niche.” The chef “launched a food delivery service together with his then fiancée Margarita [Kallas]-Lee,” serving $200, 10-course tasting menus in which they “set up everything in the homes of the customers.” The couple, it should be mentioned, first met each other in seventh grade and can claim similar, winding paths to the kitchen. Kallas-Lee, “originally from Latvia, grew up with grandparents who indelibly imprinted on her a love of cooking.” Upon moving to the United States “as a young teenager,” she “worked as a runway, print and commercial model while feeding her passion for cooking by catering events around Los Angeles.” In 2011, Kallas-Lee “answered the lifelong call of a culinary career, joining the historic D’Cache in Toluca Lake as pastry chef.” This led her to reconnect with her future husband and, as it happens, did not stop her from booking appearances on shows like New Girl, NCIS, and The Newsroom from 2013-2014.

Wolf Cuisine, as the “food delivery service” was called, offered “a brilliant and innovative dining solution concocted by alpha chef Phillip Frankland Lee.” More specifically, it would claim to offer “whimsical arrangements and adventurous pairings bound to curb even the most ravenous appetite.” The concept’s opening menu is still accessible via social media (and even exists in video form), comprising dishes like “Oyster” (with lime panna cotta, mignonette, and American caviar), “Green Lip Mussel Cebiche” (with avocado mousse, uni, salmon roe, and pickled onion), “Sweet Onion Soup” (with passion fruit), “Scallops” (with foie gras and cauliflower), and “Dry Aged New York [Strip]” (with Peruvian potato, asparagus, and tomato). Truth be told, while the business seems a bit tacky on the surface, the fine dining delivery idea must have been a bold one for Los Angeles in 2012. The dishes, too, demonstrate an admirable degree of creativity for the era without veering off into anything too strange.

It is hard to find much in the way of reviews for Wolf Cuisine during the period it operated. One customer, on Facebook, termed it “the most delicious haute cuisine I had outside of Japan” with raw fish “so fresh it melts in the mouth.” However, the business’s Yelp page only features a trio of one-star ratings complaining about a holiday Groupon deal (that discounted the meal’s $200 price to $99). Users note “horrible customer service & business ethics” in attempting to schedule their delivery, terming the experience “frustrating and aggravating” despite calling “3 weeks before the desired date.” In one case, “the two person coupon turned into 2 people sharing one meal” as Wolf Cuisine “wanted us to buy another for two meals for two people.” While this haggling felt “really sleezy [sic]” and left one reviewer (observing that “the monthly menu never changed over 4 months”) feeling “not even sure this business is real,” another conceded “the food was OK and the idea and presentation were ‘fun’” despite the “lack of responsiveness.”

Whether the experience provided—at that eyewatering $200 price point (equivalent to about $270 today)—was ultimately good or bad, Wolf Cuisine represented an important step in Lee’s career. It marked his move from “dishwasher at 18” and “Sous Chef at 21” to “Executive Chef at 24” and the beginning of a longstanding professional (and personal) partnership with Kallas-Lee. It also laid the foundation of Lee’s larger media profile thanks to features in The Huffington Post and Eater LA that touted the cleverness of the concept (and its chef’s L2O and Alinea pedigree) without passing further judgment on how the food actually comes together. (The latter piece comes courtesy of none other than the queen of conspicuous consumptive “foodie” shilling herself: Kat Odell. One pointed comment states that Lee is “as much a chef as Kat Odell is a legitimate journalist.”)

Concurrent with the operation of Wolf Cuisine, Lee would launch a Kickstarter for his movie COOK. The “film,” written and directed by the “award winning” chef, was described as “an intimate story taking audiences into the battlefield of the professional kitchen exploring the intertwining passions of FOOD, LOVE, and SEX.” At the time of the fundraiser’s launch, the project boasted “a full cast and crew of industry professionals excited to go on this adventure” along with “a distribution deal for a wide theatrical release” secured (along with “half” the budget through “private investors”) on the basis of the script and idea “alone.” COOK would only raise $19,661 of its $65,000 goal—meaning the Kickstarter funding was cancelled and the project never came to fruition—but a teaser trailer survives.

By the end of 2012, Wolf Cuisine came to an end as Lee set his sights on the next step of his career. Looking back, the chef would term the “unconventional venture” as “successful” but said “it was a lot of work and he was anxious to open his own restaurant in L.A.” The first move in that direction would come with the announcement (once again from the ethically bankrupt Kat Odell) that Lee dropped “Eater a note explaining that he has accepted the title as executive chef at D’Cache, a small Basque restaurant in Toluca Lake.” Readers might recognize the name of the restaurant as the “historic” place where Kallas-Lee “answered the lifelong call of a culinary career” as pastry chef in 2011. Lee would look to “re-conceptualize” D’Cache’s “existing bill of fare” and try to “bring better cuisine back over the hill.” He would at least try to do so before opening “a full service restaurant under his direction in West Hollywood” the following summer. (Another thorny comment states “unfortunately for all involved, Phil cannot and will not threaten anyone with good food.”)

Lee would reach the mountaintop—“chef and owner at 25”—with his “first solo restaurant” in April of 2013. Scratch | Bar would begin as a pop-up within L.A.’s Tiago Espresso Bar + Kitchen but, after a few months, found its own permanent space. With chef de cuisine Joel David Miller (of Cleo), sous chef Ryan Duval (of Animal), and pastry chef Kallas-Lee as part of his opening team, Lee served inventive à la carte fare like “Pork Belly & Raw Oyster,” “Puffed Smelt & Bone Marrow,” “Pig’s Head,” “Warm Hamachi w/ Sweetbreads,” and “Local Squid & Mushrooms” while putting the finishing touches on a “five seat chef’s tasting bar” where he planned to serve a 12-course menu. When this counter eventually opened in December of 2013, it would boast room for 11 diners per seating with “12-15 plates priced at $111” comprising a mix of Lee’s “signature dishes and specials which change nightly.”

Nobody less than Jonathan Gold of the Los Angeles Times would review Scratch | Bar in March of 2014. The dearly departed critic would term the restaurant “a welcome bit of comic relief” in a “restaurant scene dominated at the moment by extreme localism, modernist trickery and the marriage of European and Asian technique.” Gold likened Lee to “the wiseguy telling jokes in the corner while the popular kids forage miner’s lettuce and make buttermilk cheese with a centrifuge” while sagely observing that “hyper-intellectual cuisine has its place, but parody can be more fun.”

Of the fare, the critic singled out “canapés of sweetbreads, tiny flatbread and maple vinegar” (titled “’Chicken’ ‘n’ Waffle”), a “Smoking Goat’s Milk Cheese” (“dry, crumbly fresh cheese” with puréed olives, toast, and “smoldering dried timothy grass”), and the “signature presentation” of “Squid in a Box” (with “fried potato” and a “tar-black purée of charred eggplant”) for praise. Other experiments, like combining “the squishiness of long-braised pork belly” with “the briny creaminess of uni” or a “corn-infused custard spiked with king crab meat” do not work. However, Gold says “you can see the reason behind” the pairings. Ultimately, he is “not sure Lee is aiming toward a higher end at Scratch Bar,” but the chef’s “food tastes pretty good, it is attractively presented and it makes you smile.” “This,” the critic says, “may be enough.”

Gold was right to note that Scratch | Bar’s “tiny portions and militant whimsy might enrage a certain kind of customer,” for Yelp reviews from that era are split between a majority of four- and five-star ratings and a notable minority of one- to three-star evaluations criticizing strange flavor compositions and an unshakeable sense of hunger. Still, the restaurant was clearly (at the very least) a modest success, and Lee—with wind in his sails—set about opening a second concept in September of 2014.

The Gadarene Swine, as his next venture was called, represented the chef’s Biblically named “return to the Valley” (where he once worked at D’Cache) via a “near-vegan restaurant” (compromising on the use of honey) with an eight-seat chef’s counter and a few scattered tables. It sounded a lot like Scratch | Bar and would allow Lee, once more, to make “much of the food right in front of the guests” in accordance with an “all-vegetable” ethos and that evening’s “whims.” However, the chef wanted to avoid the word “vegan” because the term “has become so politicized” and he was looking to cook for a broader audience than what it might imply.

The opening menu included dishes like “Lemon & Pistachio Kale Chips” and “Olive Stuffed Olives” (both taken from Scratch | Bar) alongside new creations like “Blackened Cauliflower,” “Roasted Mushrooms w/ Burnt Sweet Potato,” “Crispy Lollipop Kale,” and “Vegetables in a Box” (a variant of the signature “Squid in a Box.”) Yelp reviews of the concept would, once again, be split between a majority of positive (four- and five-star) reviews and a vocal minority (in the one- to three-star range) terming the menu “pretentious,” the portions “cartoonishly tiny,” and everything tasting “EXACTLY the same.”

Nonetheless, Jonathan Gold would review The Gadarene Swine a couple months after opening and term it maybe “the first purely vegan restaurant ever opened by a frankly carnivorous chef, an animal-free zone populated by hummus with seaweed chips served in clay planters and dips served in simulated birds’ nests.” Rather than embracing “alternative proteins” or indulging in “vegetable worship,” the critic contends that “Lee’s cooking is basically the same as it is at Scratch Bar, except without the meat: housemade everything, tons of pickles, lots of crunchy dehydrated vegetables, pistachios everywhere, and simple flavors enhanced with olive oil, lemon and salt.”

More specifically, Gold characterizes the “Vegetables in a Box” as “basic yet complex, depending more on the delight of the presentation than on the mash-up of flavors.” Lee’s “PB&J” (“churned peanut butter topped with smashed prunes, thinly sliced onions, pickled vegetables and arugula”) is “like what would happen if your dad absent-mindedly garnished your lunchtime sandwich as if it were Black Forest ham on rye.” But the critic, at least, “liked the sweet, deep-fried olives a lot” in an overall lukewarm review that left him thinking The Gadarene Swine “is a complicated place.”

2015 would see Lee named as one of 10 U.S. finalists in San Pellegrino’s “Young Chef 2015” competition (he would lose to Vinson Petrillo of Charleston, SC) and, otherwise, continue to run both his concepts until the start of a rather strange saga. In the middle of July, Scratch | Bar closed “overnight” as the restaurant was “nearing the end of its lease” and the chef sought to relocate the “2.0 version” to a “hipper part of town.” Fair enough, you say, but—just a week later—“Someone Reopened Scratch Bar in Beverly Hills, But Didn’t Tell Phillip Frankland Lee” (as the Eater LA piece was titled). The revived concept, later termed an “imposter,” was helmed by Dario Danesh, “Lee’s longtime (former?) partner in the…space” and a partner in The Gadarene Swine to boot. When a Yelper complained about a subpar experience under the management, Lee personally responded and noted Scratch | Bar had been reopened “without…[his] consent.” The chef graciously offered the aggrieved diner a free meal at The Gadarene Swine to make up for the confusion. However, the “imposter” concept would persist until October of 2015 when it finally closed.

That month, nonetheless, would be a great one for Lee. He would formally announce the new location of Scratch | Bar (now formally titled Scratch | Bar & Kitchen) on the second floor of a “high-volume shopping center” in Encino. And, even more consequentially, the chef could announce that he would be competing on the 13th season of Top Chef. You have already mentioned some of the reaction Lee provoked via his appearance on the show, but—even in that “villain” role—the boost to his public profile would have been significant. The season aired between December of 2015 and March of 2016, ending just in time to see Scratch | Bar “2.0” receive its first professional review.

The concept had actually opened in December, ensuring that Lee could make the most of his Top Chef run, and the chef’s television appearance would strongly color LA Weekly critic Besha Rodell’s two-star (out of five) review. In the piece, the author mentions season six contestant Michael Voltaggio as a point of comparison with her subject. Both he and Lee (who “played the part of villain perfectly, either through force of personality or force of clever editing”) are said to embody the image of the “tattooed badass” redefining “American culinary modernism.” The two appear to be “cut from the same cloth,” but the latter complained about having to “cook food to make the judges happy” (exiting mid-season) while the former won Top Chef feeling “it was just about cooking good food.” Voltaggio, like Lee, “may give off the appearance of doing whatever the fuck he wants,” but “underneath it all is a rigorously trained chef, one who understands the rules before he breaks them.”

This forms the core of Rodell’s criticism of Scratch | Bar, the “conundrum” that “lies at the heart” of the concept: “Can a chef really just do whatever the fuck he wants — with no classical training, no years spent working his way up through the ranks? Should the truly talented be able to fly free early and without constraints?”

The critic singles out “a sake shooter layered with sea urchin and avocado mousse, with a green mussel and a sliver of serrano chili speared across the top” as being “assertively sweet” and setting off the seafood “in the most disconcerting way possible, like a dirty martini garnished with a maraschino cherry.” A “bowl of popcorn touched with butter and thyme and salt and, yep, sugar,” she says, “doesn’t work any better.” There’s even an “insane ode to lowbrow sushi rolls”—”made up of a base of sushi rice topped with torched sea urchin, nubs of pork belly, diced cucumber and tons of salmon roe”—that Rodell cannot decide is “brilliant or an abomination.”

While sugar “is an issue throughout many dishes,” there are great “successes” when “Lee resists his obviously strong urge to combine dinner and dessert.” These include “soft roasted salmon…with beautiful rainbow carrots, salmon roe and daubs of yogurt,” “torched escolar over sunchoke puree with puffed amaranth…[and] nubs of sweetbreads,” and more salmon roe “used on a dish of house-made chorizo over a smear of mushroom paste.” Even “some of Scratch Bar’s cheeses are pretty good.”

Rodell finds “there’s something genuinely heartwarming about the enthusiasm and sense of adventure that drive this troupe of cooks” who “make everything, including bread and charcuterie” by “scratch.” But she contends, for “many kinds of culinary techniques, there really is no substitute for learning under a master, for being an apprentice rather than a wunderkind. This shows itself most obviously with disciplines that are entire professions: the aforementioned charcuterie (which in the case of Scratch Bar is mainly smoked or cured pork that turns out far too salty and slick in all the wrong ways), as well as baking (the bun on the Scratch Bar burger is supposed to be brioche but is dense and almost crumbly and overwhelms the other ingredients).”

Lee “appears to be someone who believes that training in those fields is optional, that some chefs can succeed through the sheer force of talent.” But, in doing so, the chef “does a disservice to the very profession he aims to glorify.” He is “so wrapped up in boundary-pushing that he can’t taste the flaws in his own cooking” and ultimately lacks “training and time and the ability to recognize when people ‘not understanding’ your food is actually just the food not tasting very good.”

This review, while quoted at length, strikes at the core of the criticisms levied at Lee for his time on Top Chef and (via comment sections and Yelp) the nature of his cooking. You think it provides a particularly useful paradigm with which to judge Sushi by Scratch Restaurants, especially when Rodell concedes “there’s plenty that tastes good at Scratch Bar” along with “inventiveness and excitement and food that could only come from the freedom Lee has given himself and his crew.”

The chef, true to form, took to social media to rail against the negative review, perceiving it as more of a “personal take on me as a professional” (based on Top Chef) than a careful evaluation of “cookery or technique.” He felt “dumbfounded and a bit let down” to see her not mention “desserts, drink options, hospitality, or many of the things you would look for in a ‘review’ of an establishment” but invoke the trailer to Lee’s COOK project (as you yourself did). Personally, you think Rodell was fairly specific about the flaws in some of the dishes and the flawed attitude that informs how crafts like charcuterie and baking are approached at Scratch | Bar. Given that Lee has benefited from an uncommon degree of media attention since the very start of his career, it seems proper (as you have already done) to call his manicured image into question. “Chutzpah” (a term that Rodell invokes in her review) has its place in inspiring diners’ confidence, but no good critic should allow naïve consumers to be deceived by a dilettantish approach to craft. Insofar as she actually noted problems with the cheese, charcuterie, and bread, it is right to take aim at a “persona” that seems unwilling (or unable) to hone his techniques in a traditional fashion. Rodell certainly shouldn’t stand by and allow someone to transform laziness or arrogance into a virtue!

Despite the negative evaluation from LA Weekly, Yelp ratings of Scratch | Bar from the time show the usual pattern: a vast majority of four- and five-star reviews juxtaposed by a notable minority of one- to three-star ratings finding the experience “loud, crowded, and uncomfortable” with “pretentious” food lacking “in diversity and quality ingredients” for the price.

Though The Gadarene Swine would close in July of 2016 (due to lingering problems with former business partner Danesh), Lee had signed on as a chef of “longtime Los Feliz Mexican dining anchor” El Chavo in May and could tout a forthcoming “Scratch Bar adjacent noodle joint,” titled Oh Man! Ramen, in November. The latter spot would fall through but be replaced by a “seafood-focused venture” titled Frankland’s Crab & Co. On the other side of Scratch | Bar, the chef would open Woodley Proper, a “full-on cocktail den” offering a “proper dining at the bar experience” like towers of “house-cured charcuterie, Scratch Bar x Stepladder Creamery cheeses, and chilled shellfish.”

Woodley Proper and Frankland’s Crab & Co. would open in April and May of 2017 respectively. The latter concept would survive less than a year, closing (with a three-and-a-half-star Yelp average) to “make room for a lounge area for Scratch Bar.” Woodley Proper would last a little over two years (and can claim a four-and-a-half-star Yelp average at the time of closing). But the year’s most consequential opening would occur at the very end of June when Lee “surprised media… with a multi-course omakase meal from a newly-built private sushi counter, hidden inside a formerly unused back room” within his cocktail den.

The concept, which would eventually be known as Sushi | Bar (before later adopting the Sushi by Scratch Restaurants name), offered a $110 menu for eight diners at a time spread across three seatings a night. Lee, despite having “little formal background in sushi,” was inspired by “his experiences at places like [two-Michelin-star] Urasawa, where he dined as a young line cook.” However, he did not intend to even try to offer “hyper-traditional Japanese cuisine.” Rather, despite fearing “people would [be] upset that young white people are doing sushi,” he crafted “new wave nigiri” (“sweet-corn-brushed yellowtail; yam with salmon roe and mushroom dashi; sushi rice topped with roasted bone marrow”) in a space described as a “1930s-Japan-inspired” speakeasy.

Though Lee described that “at first when we were shopping at the fish markets we didn’t have a lot of clout,” by September of 2017 they were getting “the best fish” with everything flown “overnight from Tsukiji Market in Tokyo.” A few months in, the chef would characterize the response from diners as “incredible,” sharing that he already has “many people who come in more than once a week.” Without “trying to sound pompous,” he also shared that “upwards of 80% of diners say it’s the best sushi they’ve ever had in their life, and these are people who’ve had some of the best sushi in the world.”

The Los Angeles Times would not review Sushi | Bar until May of 2019, but Patricia Escárcega’s evaluation was a positive one. By then, the restaurant was serving “17 courses of unapologetically nontraditional bites” for $125 and leaning into that “new wave nigiri” tagline. But the experience also began with a “complimentary house cocktail” and a “choreographed and schticky—or charming, depending on your point of view” route to the moodily lit counter that “blurs the line between a modern omakase dinner and a cabaret performance.” The critic, in a manner reminiscent of Gold’s original comment regarding the cooking at Scratch | Bar, suspects “some of the bites, topped with things like sourdough breadcrumbs or yellow corn pudding sauce, will infuriate a certain kind of customer, sushi purists in particular.” However, everyone else “will find it fresh and uncomplicated, in the sense that it all tastes pretty good.”

Digging deeper, Escárcega notes that “by the time the seventh or eighth course rolls around, the kitchen’s formulaic one-two punch is clear: a swab of the subtly sweet house-made soy sauce, some fresh grated wasabi, a sprinkling of Bali salt.” The sequence, while “highly predictable,” is also “effective and good.” Likewise, there are some more unique bites worth special praise: “Japanese yellowtail…scored and slicked with a surprisingly delicious yellow-corn sweet pudding,” “shima aji…splashed with a yuzu kosho infused with the smoky, savory notes of Anaheim chile peppers,” and “smoked albacore wrapped in sake-soaked seaweed, topped with crispy onions.” Even dessert, “a sweet frozen lozenge of lime ice cream and black sesame shortbread encased in a green tea chocolate shell” made by Kallas-Lee, is termed “marvelous.”

This must stand as one of the finest professional reviews Lee has received in his career, and the public seemed to agree. Sushi | Bar (now known as Sushi by Scratch Restaurants: Los Angeles) enjoys a four-and-a-half-star average on Yelp. However, as is typical, there is a share of one- to three-star reviews criticizing upselling, the amount of sugar used, “mushy” rice, heavy-handed toppings, and being “all presentation without substance.”

With Sushi | Bar making waves within Woodley Proper, 2018 would see Scratch | Bar receive “a conceptual refresh and a minor interior layout change” termed the “2.0” version of the restaurant. The space, thanks to “wall-leaning banquettes that face the kitchen,” would feel more like a “kitchen theater.” The menu would retain Lee’s “signature dish” of a “poached green mussel sake shooter” but “otherwise the courses are completely new.” The chef would “lean heavily on the wood-fire hearth” but retain the “scratch” ethos of making everything from “the cheese and butter to the bread and charcuterie” in house. The “heavy” reliance on (totemic) luxury ingredients like “uni, salmon roe, and foie gras” would be dialed back while Kallas-Lee’s desserts would be “numerous,” sometimes “visually deceptive,” but “well-composed.”

For Lee, the later part of 2018 and first few months of 2019 would see the culmination of a set of concepts within Santa Barbara’s Montecito Inn: another location of Frankland’s Crab & Co., an “all-day hotel restaurant” called The Monarch, a “modern approach to the grand fine dining tradition” titled The Silver Bough, and a second iteration of Sushi | Bar.

Of these, The Silver Bough is undoubtedly the most interesting. It opened in late January of 2019 touting a $550 ticket price (inclusive of tax, tip, and beverage pairings) for one of eight spots in a “400 square foot dining room-within-a-dining room” (within The Monarch) with a sole 6:30 PM seating each night. Lee stated at the time of opening that “The Silver Bough is designed to be a three-star restaurant. That’s what we want. If we get one star, I will probably burst into tears. But three is what we’re shooting for.”

Eater LA termed the restaurant “California’s Most Ambitious New Restaurant” and Forbes distinguished it as “undoubtedly” the “most extravagant and exclusive dining experience in town.” Food & Wine would call it “a fine-dining destination that walks the fine line between balancing extravagant flavors and gilding the lily” while the Santa Barbara Independent would ask “Did the World’s Best Restaurant Just Open in Montecito?”

Existing menus for The Silver Bough display dishes like “American Sturgeon Caviar” (lobster gelee, hazelnut cream, smoked eel), “Live Spiny Lobster Tartare” (sea urchin, tomato aspic), “Pommes Souffle” (stuffed with lobster innards, topped with sea urchin), “Lightly Grilled King Crab” (sea urchin emulsion, sauce vin jaune, caviar), “Legendary Olive Wagyu Ribeye Cap,” “Center Cut Legendary Olive Wagyu Ribeye” (lots of black truffle, candied pecans), and “Black Truffle Ice Cream” (white truffle brioche cone, 24k gold). The wine pairing, you must say, impresses you with producers like Bruno Clair, Clemens Busch, D’Oliveira, Keller, Larkmead, Sandhi, and Realm being featured. And the restaurant earned six five-star reviews from Yelpers during the time it was open.

The lone one-star review comes from a user whose reservation was cancelled and refunded due to circumstances beyond the restaurant’s control. As it happens, The Silver Bough would close in early September of 2019 “owing to a staffing issue.” In October, Lee would announce he was closing all his Montecito Inn concepts save for one. Sushi | Bar would remain (that location being run by brother Lennon Silvers-Lee), and the chef would be “heading back to Encino to regroup” and plan the expansion of the omakase concept “up and down the California coast.”

These plans would be delayed by the pandemic—during which Lee sued his insurance company “for declaratory relief” surrounding its business interruption policy—but, by the summer of 2020, the chef’s creative juices were once again flowing. In June, he would announce the launch of Pasta | Bar in the former Woodley Proper space: a “multi-course tasting menu” of Italian flavors “guided by chef de cuisine Kane Sorrells” (formerly of NYC’s two-Michelin-starred Blanca). That following September, Lee would announce Leviathan—an “all-outdoor wood-fired” seafood restaurant—one floor below Scratch | Bar, Sushi | Bar, and the new Pasta | Bar. This latter concept seem to not have lasted very long through the end of the pandemic, but the chef’s other ideas would prove resilient.

Lee and Kallas-Lee took the Sushi | Bar concept to Austin in late December of 2020 as a pop-up when Los Angeles “disallowed all onsite, dine-in service during a big surge of COVID-19 related cases” in order to “keep their staff employed.” The couple originally intended to return home at the end of January 2021, but “reservations were so immediately booked up with a long waitlist (at the end of its third week, the list was over 100; by the end of January, it was over 20,000) that they opted to extend the stay.” Eight months later, the waitlist was still full, and Lee could proudly state “we’re here to stay.” Far from being a copy of the Encino and Montecito locations, the Austin version combined fish flown from “Japan, Australia, and Santa Barbara” with “Texas products” like “wagyu, bone marrow, olive oil, and all of the produce.”

Despite his success in Austin, Lee was on the precipice of the biggest moment in his career. In September of 2021, back in California, Michelin would award both Pasta | Bar and the Montecito location of Sushi | Bar with one star. The chef “started crying” when he heard the news, describing the accolade as a “lifelong goal” and proclaiming “the only way you can be recognized as the best is if you get a Michelin star.” The dual awards—both of which Lee retained in 2022—mark him as the contestant most awarded by Bibendum in Top Chef history: an absolutely stunning accomplishment given the bitterness that surrounded his exit from the show.

With all this momentum behind him, the chef would announce, in January of 2022, an Austin location of Pasta | Bar. He would also announce the first location of Sushi by Scratch Restaurants in Cedar Creek, Texas. The name of this latter venture would represent the sale of Sushi | Bar (now run by executive chef Ambrely Ouimette, formerly a member of Lee’s team) to new owners and a reopening of the same kind of concept (Scratch Restaurants being the name of the restaurant group under which all of Lee and Kallas-Lee’s establishments had been organized). Subsequently, the Sushi | Bar locations in Encino and Montecito would change their names to Sushi by Scratch Restaurants: Los Angeles and Sushi by Scratch Restaurants: Montecito respectively.

In July of 2022, Lee would open Sushi by Scratch Restaurants: Miami (with a competing Sushi | Bar location arriving a few months later). This was followed in September with Sushi by Scratch Restaurants: Seattle. And, finally, that leads you to February of 2023 and the opening of the group’s sixth omakase property: Sushi by Scratch Restaurants: Chicago.

Eater, as always, would break the news of Lee’s arrival via its Chicago outlet. The restaurant was originally “ticketed for West Town,” but the chef’s team “quickly switched destinations after finding the Swill Inn space” in River West. The “Midwestern outpost” would replicate the same format seen at other Sushi by Scratch Restaurants locations: involving a “bit of theatricality” as diners are “brought into an 18-seat whiskey bar for a welcome cocktail” then welcomed “to the actual sushi bar, which is staffed by three chefs and a bartender.”

It was revealed that Lee has plans for “another concept” in the building’s more expansive upstairs space. However, at the time, the article stressed the chef’s L2O and Alinea credentials, his two Michelin stars, and the fact that Sushi | Bar’s original chalkboard reservation system “was inspired by his many nights spent using a quarter to reserve a pool table on the second-floor at Delilah’s, the divey punk rock bar in Lincoln Park.” Clearly, Lee was not just a carpetbagger looking to capitalize on Chicago’s nascent appreciation of omakase (even though he also made clear his goal “to take this sort of micro restaurant and sort of grow it and grow it and one day become the most starred concept around the country and potentially the world”). Rather, he would look to build an experience where “chefs connect with diners during an intimate meal” and not “tell somebody else’s story, but to tell mine based on the flavors that I grew up with.”

Chicago Food Magazine, nothing more than a repository for press releases in truth, would come out with Sushi by Scratch Restaurants’s official line a day later. Lee and Kallas-Lee would share that they “are thrilled to be opening our first dining concept in Chicago, a city that is widely recognized for its vibrant and dynamic culinary scene.” For 30 guests spread across three seatings each night (Wednesday through Sunday, though other locations have expanded to operating daily), the chefs would look to offer “an unforgettable, deliciously fun, one-of-a-kind personalized experience” via “a progressive 17-course nigiri tasting menu experience” showcasing “fish and shellfish primarily flown in twice a week from Tokyo’s Toyosu Fish Market.”

Lee and Kallas-Lee would note that Sushi by Scratch Restaurants is “revered for our inventive flavor profiles” and “although some of our nigiri flavor profiles may not be what people expect when they think of conventional sushi, our approach to nigiri is very much traditional.” (Of course, by the chef’s reading, the most meaningfully “traditional” aspect of sushi “was that the chef would tell the story of their childhood and the neighborhood that they grew up in”—a coy attempt to redefine the word and untangle it, in line with his own lack of any apprenticeship, from the mastery of canonical techniques.)

On February 14th, concurrent with Sushi by Scratch Restaurants: Chicago’s opening, Lee and Kallas-Lee would appear on WGN9’s “Lunchbreak.” Showing off the omakase’s full set of nigiri (while making a couple of the pieces live), the chefs shared that they had wanted to open a restaurant in the Windy City together when living there in 2010 but it didn’t “pan out.” Nonetheless, they “loved” Chicago back then and saw it as a natural home for the expanding company. At their restaurant, in Lee’s own words, “there’s no menu—you just sit down and we feed you for two hours.” The chef would serve the reporter two of his signatures: “hamachi painted yellow with sweet corn pudding and topped with a fine sprinkle of breadcrumbs” and “unagi that’s fried crispy in…rendered bone marrow fat” (putting on quite a show with his torch in the latter case). Kallas-Lee, likewise, would share the details of her “Matcha Bon Bon” that ends the meal.

(Lee, by himself, would give an encore of this performance on Chicago Today in early April.)

Forbes, about a week after the restaurant had been open, declared “This New Chicago Sushi Speakeasy Is The Stuff Of Dreams.” It would also term Lee’s concept “the Windy City’s most talked about new sushi speakeasy” (a bit of a nonsensical phrase considering a lack of any other openings at the time). However, the piece would reveal that The Swill Inn had become The Drop In and now also houses the “NADC smash burger, a collaboration between Chicagoan Neen Williams, a professional skateboarder” and the Michelin-starred chef. During a meal at Sushi by Scratch Restaurants, you will “not only listen to stories, connect with the other guests, and learn an incredible amount about Japanese-inspired omakase as the night progresses” but also “connect with the [‘master’] chefs as they prepare each course with magician-like fingers.” Within the “unpretentious-yet-vogueish underground sushi sanctuary” the “Ryūkōka-like music and sideway glances” almost make you feel “like you’re a part of a secret society or a whodunit murder mystery à la Glass Onion.”

Lee, having already expanded Sushi by Scratch Restaurants into four other markets (where Tock availability shows they continue to do quite well), clearly knows how to promote his concept. Personally, you stumbled upon its reservation page and booked your first set of tickets without any idea of what you were getting into. Frankly, knowing that the omakase was part of a “chain” lowered your expectations. Yet, before the end of that first meal, you had already scheduled a return visit. Like it or not, the restaurant is a consequential addition to Chicago’s omakase scene.

Plus, after dwelling on Lee’s career for so long, you cannot help but respect his fortitude. On one hand, he clearly benefitted from the promotion given by Kat Odell, Farley Elliott, and Matthew Kang (all of Eater LA) early in his career. These “journalists” were desperate to pump out any content they could (standards be damned), and Lee was savvy enough to package and deliver it to them. Being a Top Chef “villain” and courting a coterie of haters was clearly a bonus: it still counts as attention at the end of the day. Likewise, Lee’s boldness and creativity should be praised (even in the face of failure), but it seems right to question if a certain degree of privilege allowed him to become an owner at such a young age and weather multiple closures without skipping a beat.

Those concepts that did prove successful did so in a market that, at the time, was immature: “the people in Los Angeles aren’t foodies” said Michelin Guide director Jean-Luc Naret when Bibendum left in 2009. And Scratch | Bar, for what it’s worth, excelled as top dog in a sleepy, wealthy enclave whose residents would rather not drive several hours to eat in Los Angeles proper. Lee’s approach to cooking, largely self-taught and even a bit contemptuous toward the traditional “paying dues” development of craft, seems tailormade for a population of diners that has little exposure to how things are “supposed” to be. Montecito, as best as you can tell, fits that pattern as well.

However, with enough time, experimentation, and legitimate growth, Lee has struck upon a formula that undoubtedly works. Scratch | Bar, Sushi | Bar, and Pasta | Bar overwhelmingly please people in their markets even if more well-heeled diners and discerning critics might disagree. Bibendum has judged two of these concepts to offer “high quality cooking, worth a stop,” awarding a set of stars—twice—that must now certainly quiet all the haters (or, at least, make them question what exactly it is that the tire company prizes). So, despite facing detractors almost every step of the way, Lee is kind of unstoppable. You admire him for that, and the chef seems fairly gracious now that he has established a small bit of the empire he has always wanted.

With Sushi by Scratch Restaurants: Chicago, Lee enters a relatively mature fine dining market for the first time, yet one that has undoubtedly been declining—at least when it comes to top expressions of gastronomy—since he worked at L2O and Alinea. However, when it comes to omakase appreciation, the city is still rather immature and far from being saturated. Lettuce Entertain You only got in on the act last year and seems sure to earn (at least) a Michelin star for its effort. Mako and Yume have already been awarded by Bibendum but, despite being located not all that far from Lee’s “sushi speakeasy,” do not aim to offer the same style of experiential dining. Sushi Suite 202, another import, seems like the closest point of comparison all the way over in Lincoln Park. While Kyōten, up in Palmer Square, remains singular in its hyper-premium, one-seating-a-night approach to the craft.

What exactly separates Phillip Frankland Lee from Otto Phan (another polarizing chef who came to ply his trade in Chicago)? And just how likely is Sushi by Scratch to earn a star here (as it did in Montecito)? The concept has not yet been evaluated by Bibendum in Miami (a city that already arguably has a better omakase scene), and it seems unlikely that it will be included—being open for such a short period of time—in Michelin’s looming 2023 Chicago guide. As Kyōten proves, Chicagoans do not need to rely on a French tire company to tell them where to get good sushi. But any award would certainly put Mako and Yume’s stars into perspective while helping to clarify just how much an overall sense of “experience” counts.

Lee’s omakase performance has quickly become one of the city’s hottest sold-out shows, and you are eager to engage with a concept that so wholeheartedly embraces the idea of hospitality as theatre. Sushi by Scratch Restaurants does not only present an opportunity to critique food and drink, but to question their very importance within a larger sense of dining “occasion.” There does, indeed, seem to be a bit of an Alinea streak about this idea (for better or worse). And it will, no doubt, be gratifying to unravel exactly what Lee is bringing to a city that he loves, as well as how his concept might inform the growth of Chicago’s wider sushi appreciation.

You have visited Sushi by Scratch Restaurants three times, spanning a period from February through April of 2023. As usual, you will condense the sum of your experiences into one cohesive narrative.

With that said, let us begin.

Sushi by Scratch Restaurants: Chicago is firmly located in your neck of the woods, an area characterized by its access to some of the city’s greatest dining neighborhoods but lacking many of its own attractions. River West, as this small slice of land located off of the North Branch is termed, will soon be home to the Bally’s Chicago casino resort. Neighbors (your neighbors) fought the decision like hell. The development stands to spoil their quiet, residential enclave (complete, of course, with its own gated community). However, you welcome the transformation of the decrepit Chicago Tribune printing plant into an entertainment and hospitality hub. The casino will work to direct some of River North’s flourishing nightlife westward, and you salivate over the prospect that it will house an estimable dining destination.

For now, however, River West (though its exact boundaries are often blurred with the Fulton River District) is home to stalwarts like Piccolo Sogno, La Scarola, and The Dawson. Rob Katz, Boka Restaurant Group co-founder, has just opened The Pearl Club at the same intersection. But most consumers, undoubtedly, are drawn a few blocks further south at present. There, you find the entrance to Fulton Market proper, with places like Kumiko, Moneygun, Oriole, and—yes—Mako heralding your arrival at one of Chicago’s most delectable corridors.

Sushi by Scratch Restaurants sits somewhere between these zones and just a little further east. The Drop In, the bar that houses the concept, can be found on Milwaukee Avenue just beyond the five-way intersection where it meets Kinzie and Desplaines Street. Its neighbors are the ever-fragrant Blommer Chocolate Company, the hulking Pickens Kane Moving & Storage facility, and a Jewel-Osco location that is rather expansive in its own right (complete with an in-store bar). The one-acre Fulton River Park located on the opposite corner is also pretty nice. The Blue Agave restaurant located next to it is a bit less exciting. Yet Sushi by Scratch Restaurants can at least count Perilla as a neighbor—though the Bib Gourmand-winning Korean spot is currently closed for renovations.

Approaching Lee’s restaurant on foot, you are immediately struck by its intimacy. The two-story, brown brick building is dwarfed by Perilla’s three-story home (complete with Michelle Obama mural by Royyal Dog) and the fortress-like Pickens Kane across the street. Further, the Korean concept’s outdoor patio—along with a rail bridge located on the other side of The Drop In—ensure that the structure stands apart from any bordering walls. You can see skyscrapers in the distance (including, if conditions are right, the John Hancock Center), yet the façade of the Sushi by Scratch Restaurants venue is framed by greenery (as well as a vintage Ford pickup that sits in the alley to its side). It feels small and knowable, tinged with personality and even a bit of mystery (especially if you happen to spot Otis the dog peering out the adjacent door).

Other than signage for The Drop In, a placard only announces that Lee’s NADC Burger concept lies within. The sensation, walking through the door, is nothing like stepping through Mako’s sleek entryway. It is less assured than venturing within Yume’s labelled awning. It does not even offer the security—when stepping into Sush-san in search of The Omakase Room—that you are somewhere within the right genre. No, the feeling is a bit more like trying to find Kyōten (though Phan’s façade still makes one wonder if any business is located through those doors).

Lee, as you well know, has a flair for the dramatic: other Sushi by Scratch Restaurants locations have featured signs that say “Serving omakase by appointment only. Please ring bell for service.” However, for the Chicago edition, you receive a reservation confirmation text that advises you to arrive 30 minutes early and reveals that “our front door is located inside of THE DROP IN, 12 paces in on your right you will find a black keypad: enter 8450 and proceed.”

It takes a second for you to register that this is not the usual “press 1 to confirm” boilerplate. You wouldn’t have guessed it when first booking your reservation, but this restaurant is actually indulging in a bit of worldbuilding. It wants to tantalize you with a bit of uncertainty—and a couple dashes of mystery and romance—long before the first morsel hits your tongue. Omakase aficionados may be inclined to roll their eyes, wary of anything meant to distract from the fundamentals of fish and rice. However, those who are unsure about paying a premium for sushi will be comforted by the suggestion that they are not about to embark on a mere meal but, rather, an experience.

In practice, you cannot help but feel a bit self-conscious as you enter The Drop In. The place looks every bit the part of a neighborhood bar: faded tones of wood, brick, and leather with a long line of taps and a couple televisions playing sports. With closer inspection, you may notice a couple distinguishing touches like a memorial portrait of Anthony Bourdain and a couple skate decks affixed to a wall (remember, NADC Burger is a collaboration between Lee and a professional skateboarder). But, moving through the space, you do not sense one bit of pretense from the barkeeps or assembled patrons. None of the traditional markers that scream “luxury dining” are present. You are tempted to ask the staff for further guidance just to be sure—completely sure—that there’s an omakase here. Yet, counting out those 12 paces in your head, you come to a segment of the wood-paneled wall that does, indeed, feature a small handle and keypad. You hold your tongue, and the bartender, standing at the ready to assist you if necessary, smiles knowingly.

The keypad does not beep or click or feel particular tactile, but the door does indeed unlock. Thus, you slip into the corridor and leave the world of the bar behind. For those who have walked through the optical illusion hallway at Alinea “1.0,” this whole gimmick feels a bit primitive. However, subconsciously, it allows Lee to demarcate exactly where the Sushi by Scratch Restaurants experience begins. Such a move does not need to be sexy to work; it just needs to engage your spatial memory and signal the start of the chef’s multisensory curation of the evening. Valhalla, for all its team’s talent, cannot create this kind of liminal moment on account of its food hall setting. The concept retains its association with Time Out Market—good or (mostly) bad—while Sushi by Scratch Restaurants, even though actually related to NADC Burger, occupies a totally different world from anything going on at The Drop In. Plus, if you, as a host, play up the “hidden speakeasy” mysteriousness with a bit of panache, your guests may think the clunky keypad thing is actually a delightful surprise. Lee provides you with the tools to make a date night feel extra special if you are not too cynical to play along. He is also smart enough to know how even the most minor environmental cues help organize (and enhance) consumers’ recollection of a meal.

Stepping through the door into Sushi by Scratch Restaurants proper, you come face to face with a flight of stairs and a small sign asking you to hang your belongings on an adjacent rack before making your way downward. There, you meet the first member of the restaurant’s staff. They do not engage in any further roleplaying that might stoke the sense of mystery but, rather, offer a warm and enthusiastic greeting that puts you at ease. Your party is formally checked in and asked as to its water preferences (a nice bit of anticipation that, however, does not always ensure you get the kind you selected). Nonetheless, the interaction with the mustachioed host is polished. It assures you that something truly luxurious, despite The Drop In’s humble digs, is in store. Yet, just when you are ready to venture into Lee’s sushi sanctum, the chef’s henchman hits you with a “spiel” (as they jokingly refer to it). This evening’s omakase still costs $165 (as advertised), but the restaurant is offering a special $85 supplement that infuses certain parts of the menu with doses of caviar and truffle. Of course, you need not feel any pressure—none at all—to indulge (but just say the word and they will take your meal to the next level).

When you visited Sushi by Scratch Restaurants during its opening week, this supplement was listed on the receipt as “V-Day Omakase” (for an all-in price of $250). Later, the name of the line item would be changed to “Upgrade Omakase,” but the idea remains the same. You whisk your date through the unassuming neighborhood bar, punch in the secret code, and find yourself graciously received in the hidden chamber. You are all set to kick off a memorable evening, but there’s just one more thing. Do you want to upgrade to the superior menu, the kind of uninhibited decadence that really shows someone you care, or stick with the plain, old, standard, discount version like any uncultured swine off the street might opt for? Remember, there are no wrong choices! Lee will still happily take your money (even if you are a cheapskate). But, for a nominal 50% increase in entry price, you can leave no doubt (in the eyes of your party or with regard to that murmur of status insecurity in the back of your head) that you are doing things right. Certainly, if you are going to eat high-end sushi, you must appreciate life’s finer things.

Of course, you are exaggerating how the subtext surrounding this supplement may be taken to its logical conclusion. In truth, it is still a fairly benign form of upselling compared to what you have endured at places like Masa. However, there is undoubtedly something devious about putting customers on the spot before they have even caught sight of the sushi counter. With expectations at their height (and patrons unable to privately confer), some people will undoubtedly be snared by the proposition. You respect that Lee sequesters these luxury ingredients from his normal menu, for that ensures guests paying $165 will see their money go toward an assortment of quality fish rather than flashy totems. However, you have bitten the bullet and paid the $85 supplement during each of your three visits. The chef does a good job of slyly introducing your premium toppings without making other patrons feel inferior about their comparably plain renditions of any given bite. However, the use of caviar and truffle is totally unconvincing. They amount to needless baubles that do nothing distinguish the pieces they appear with. They make you feel like a sucker, and you most certainly are if you get goaded into taking the plunge.

It is also worth considering the $250 price point (exclusive of 20% service fee and tax) Sushi by Scratch Restaurants occupies with the addition of this supplement. It transforms the concept from a relative bargain in the omakase scene (at $165) into a place that clocks in north of Mako ($185, exclusive of 20% service fee and tax) and Yume ($225, exclusive of gratuity and tax) while matching The Omakase Room ($250, exclusive of 20% service fee and tax). Kyōten ($440-$490, inclusive of service but not tax) still occupies the top spot, but it seems clear that Lee is gunning for the Chicago sushi spots that already possess a Michelin star (or, in The Omakase Room’s case, seem highly likely to earn one).

However, while some of the city’s other omakases may make sparing use of caviar or truffle in their own right, these meager amounts are baked into one solitary price that moreso reflects the quality and quantity of fish being used. For example, Kyōten, Mako, and The Omakase Room each offer a sashimi set to start the meal along with other plated creations that preface an extensive service of nigiri. Lee, in order to efficiently get through his three nightly seatings, sticks rather strictly to bites of fish on top of rice. These fundamental ingredients will always remain at a “$165 level” even if they are topped with a luxurious supplement. So, while Sushi by Scratch Restaurants may seemingly occupy the $250 stratum, the $85 upgrade does not fuel any real creativity or structural changes to the meal. It amounts to mere window dressing, a taste of the totemic luxury ingredients that chefs love to shoehorn onto menus (but, here, being even more out of place). Thus, while the $250 sum ensures Lee is not leaving money on the table from those who might like to splurge, it is best to think of his omakase as a sharp value (at $165) that actually looks to undercut the city’s current top examples of the craft.

If one maintains this more parsimonious mentality, it should be easy to resist the offer of a supplement or, at the very least, save one’s money for the sake of purchasing additional bites at the meal’s end. Nonetheless, you must mention that these extra offerings—pieces (like kinmedai, kampachi, or foie gras) that are unique from what is included in the omakase as such—cost from $11-$15 each. Lee tends to offer three or four of them (time permitting and with an admirably soft touch) at the end of the menu, making for another kind of supplement that may tack $40-$50 onto the ultimate price of your meal. (Yume, it should be noted, operates in a similar fashion via a more extensive à la carte list.) Once more, this additional fee firmly places Sushi by Scratch Restaurants in the upper echelon of its peer group. Regardless, you will still primarily look to assess the restaurant on the basis of its bottom $165 price point while also noting the quality of these optional extra bites.

Whether or not you are enticed by the prospect of supplemental caviar and truffle, the host guides you through a beaded curtain into a makeshift lounge. Compared to LEYE’s luxe space at The Omakase Room, you have previously compared this pre-meal holding area to something “more like a jail cell.” (The host, on your most recent visit, even jokingly referred to it as a “hot, humid holding cell” themselves.) But, in practice (and just like the keypad/hidden door upstairs), this element of the experience functions well enough. Details like candles, hand towels, an abstract painting, a velvety curtained wall, and a bar cart inject some glimpses of luxury. The dimly lit space—if you are willing to play along—feels moody, intimate, and even a bit romantic. You almost feel squeezed in with the other patrons who will join you at the sushi counter but not quite so. Rather, this room helps to encourage a bit of fraternization before the actual show begins. When it comes to the evening’s later seatings, this proves essential in ensuring subsequent guests feel properly cared for—welcomed into the “experience”—and not left to be tempted by a burger and fries upstairs. Just the same, it allows Lee’s team to turn over the main space in privacy without being rushed by any other arrivals.

While your reservation confirmation text offers a “friendly reminder to arrive 30 minutes early,” the e-mail sent at time of booking clarifies that you are “encouraged” to “to show up as much as 30 minutes prior to your reservation to enjoy a complimentary welcome beverage.” Typically, you aim to be there about five minutes before dinner in order to minimize the waiting period in the lounge. Despite this, you are welcomed warmly into the space with a little cocktail made of Japanese whisky blended with unfiltered sake, housemade ginger syrup, and lime. The drink is prepared from the bar cart by the host and goes down easily, being sweet and simple enough to appeal to the masses without seeming sickly. It’s not exactly a Kevin Beary-level creation, but—hey—it’s free. They’ll serve you another one if you ask for it (“absolutely” was the response), and the libation offers a chance to toast with the other assembled patrons and break the ice.

As the reservation time approaches, the lounge also plays home to the evening’s first bites. Atop each of the tables, the host places a wooden log holding a bowl filled with pebbles and crowned with a couple fresh oysters. The bivalves, he announces, are sourced from Prince Edward Island and dressed with a tomato emulsion, some puffed rice, and a couple strands of kombu (dried kelp) “jerky.” “Not bad,” you think, as the bite goes down easy. It’s a good—if not transcendent—example of the form that is nicely presented and easy to maneuver in the setting.

Shortly thereafter, the host returns with a second opening morsel: one that initially formed the first course at the counter but has since transitioned to appearing in the lounge. He describes the “Blue Fin Tessin” as the first of three servings of this tuna (sourced from Spain) you will enjoy this evening. That term—“tessin”—refers to the tail of the fish that is ground into a paste and combined with soy, ponzu, green tea salt, and wasabi. The mixture is wrapped in a cylinder of nori (dried red algae) and topped with a bit of avocado mousse, a couple orbs of salmon roe, and some thin slices of scallion. The package, once more served on a bed of pebbles, is quite attractive. However, you find the seaweed to be rather soft and the end result, texturally, to be mushy. The flavor, regardless, is enjoyable, and you commend Lee for using the lounge as something more than just a waiting room.

Without much further delay, Lee and his team are ready to welcome you into the heart and soul of Sushi by Scratch Restaurants. Exiting the lounge and stepping through another door, you are led to the basement’s main chamber where the sound of 1920s Japanese parlor jazz waits to serenade you. There, 10 chairs are arranged across the expanse of a sturdy wooden counter. The surprisingly high ceilings feature a constellation of antique bulbs—as well as a few rattan chandeliers—that bask the bar in soft, warm lighting. Meanwhile, strips of LEDs are positioned perfectly over the cutting boards themselves, being tilted just enough to capture every move of the chefs that man them. This all makes the lighter brown (almost tan) tone of the surface positively glow like a stage. It also makes for a beautiful contrast with the darker wooden accents on the walls—along with the black wallpaper, mirrored inserts, and mounted orb sconces (that only faintly shine).

Other details of note include small slabs of chalkboard positioned in front of each place setting. The handwritten names printed thereon help guide you to the right seat while emphasizing the personal nature of the hospitality and facilitating interaction between parties. 16 more of these chalkboard placards are positioned on the wall behind the direct center of the sushi counter. They list, from left to right, that evening’s assortment of nigiri (with the opening lounge bites and Kallas-Lee’s dessert being omitted from the selection). Atop this installation, you find a wooden panel (done in the same lighter tone as the counter) displaying the Sushi by Scratch Restaurants logo. This pop of contrast serves to catch the eye and subtly connect all the drama of the “stage” area to the larger brand identity.

Beneath these features, along the wall that sits behind the sushi counter, you find another surface that houses a double-decker bar housing the meal’s pairings, a whisky selection, some plateware, and ample glassware. Even further down, you find coolers and a pair of rice cookers that serve to equip the chefs during the course of the omakase. Moving to the counter that, upon taking your seat, lies before you, it becomes apparent that the workspace is split into thirds. Off center to the left and right, the two more junior chefs are armed with knives and shadow boxes neatly filled with pristine fillets of fish. From either corner of the C-shaped bar, two diners (on each side) may cast their gaze across the surface and catch a perfect cross-section of the cutting action that precedes each bite. The remainder of the guests are spread out along the middle of the counter with the best seats located in the very center. There, the more senior chef is equipped with a wide array of brushes, spoons, and graters used to top each piece of nigiri. They, no doubt, are the master of ceremonies, but you can count on some degree of intimate interaction with whomever you happen to be seated in front of.

Overall, while you think The Drop In, the hidden doorway, and the lounge feel a bit cobbled together, Sushi by Scratch Restaurants’s dining room ranks as one of Chicago’s best within the omakase genre. Your first sight of the space, especially due to the high ceilings and stage lighting, borders on being breathtaking. It offers a very satisfying aesthetic payoff after all the mystery surrounding the keypad and the promise of a “speakeasy.” Kyōten and The Omakase Room, by your measure, clearly feel more refined and luxurious in terms of their actual finishes. However, these counters could feel a bit sterile to some (and, to be honest, that forms the traditional environment in which one appreciates such expensive fish). Sushi by Scratch Restaurants, to Lee’s credit, really does feel romantic. It feels singular compared to anywhere else in the city while making Yume and Mako—despite their stars—seem drab. Sushi Suite 202 and Jinsei Motto might form better points of comparison (both making use of unused spaces in a similar fashion), yet Sushi by Scratch Restaurants clearly surpasses them in terms of ambiance. The place feels permanent and legitimately memorable in a way that has nothing to do with the novelty value of its actual subterranean location.

With everyone settled in their seats at the counter, Lee offers a hearty welcome to the assembled diners. After noting the 17 courses that are still to come, he introduces the bartender (in truth, more of an all-around beverage maestro) that shares the stage alongside the three chefs. Along with one server (who works the side of the counter you are seated on) this man essentially handles all the traditional front-of-house tasks. He was a longtime Girl & the Goat veteran (estimable experience as far as trendy Chicago dining goes) and, when Lee is not present (more on that later), is without a doubt the most talented showman on the staff.

Taking center stage, the bartender invites you to open the small booklet placed atop the counter. As you browse through its contents, he energetically recites a spiel for those who might feel overwhelmed. In doing so, he echoes the philosophy of the beverage menu’s introduction (and that of Lee himself). The first page of the booklet recommends that “guests leave their entire experience in our hands and partake in one of our pairing options” while still welcoming patrons to “order a la carte from our carefully curated selection of Japanese Whisky, Beer, Sake, Wine and Cocktails.” Privileging a turnkey style of imbibing makes sense for a restaurant that emphasizes the larger experience, and Lee himself admits he has “anxiety about looking at a menu and choosing because what if I choose wrong? How do I know?” Thus, he, too, recommends “going on straight autopilot.”

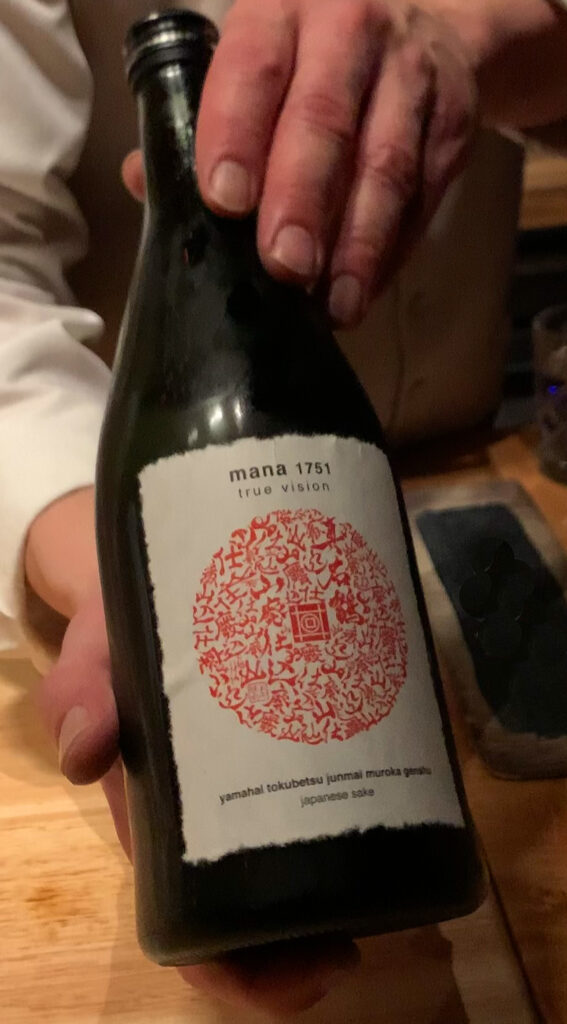

That entails a $125 “Sake Pairing” (“6 pours of premium sake”), a $110 “Beverage Pairing” (“3 premium sakes, 2 cocktails, 1 japanese wheat lager”), and a $115 “Japanese Whisky Pairing” (“6 one ounce pours of japanese whisky”). Guests are generally steered toward the middle, balanced option—with Lee claiming that “beer is fantastic with some of the roasted meats” that appear at the end of the meal. In practice, the “Beverage Pairing” is totally serviceable if a bit undistinguished, featuring bottles like HeavenSake Junmai Ginjo ($44 average price), Mana 1751 “True Vision” Junmai Muroka Genshu ($44 average price), and Tedorigawa “Kinka” Daiginjo Nama ($41 average price). The introduction to a range of different sake styles—alongside a couple cocktails and beer—adds a loosely educational element to the selection. But the most memorable aspect comes when the bartender invites guests to “bend and dip” to slurp the drink out from the cup while it is still positioned on the upper part of the counter.

The à la carte side of the beverage menu is not all that impressive in truth. It comprises a range of 27 Japanese whiskies with producers like Mars, Nikka, Suntory, and Shibui being featured and one-ounce pours ranging from $9-$118. However, you would not classify any of the selections as being particularly rare in a way that can hold a candle to The Omakase Room’s titanic list. The sake options number 13, without any producers of particular note and bottles ranging from $80-$184. However, the most expensive of the bunch—the Imayo Tsukasa “Koi” Ginjo (also the only one not offered by the glass)—is priced favorably in comparison to a $135 average. You enjoyed its balanced, full-flavored, and adaptable nature when you sampled it.

The four bottles of wine offered are listed both by the glass and by the bottle: AR Lenoble’s “Intense” MAG 18 Champagne ($38/$114), Le Pianelle’s 2018 “Al Posto del Fiori” rosé ($18/$54), Groundwork’s 2021 rosé ($18/$54), and Isole e Olena’s 2020 “Collezione Privata” Chardonnay ($47/$140). Again, these are not the most distinguished choices, but they represent a rather fair 100% markup and competent wines within styles that pose no risk of overshadowing the nigiri. You sampled both the AR Lenoble Champagne and the Le Pianelle rosé and found them to be perfectly pleasant. The cocktails, though you have not tried them (and happen to forget which are included in the “Beverage Pairing”), number four along with one additional (Seedlip-based) “Mocktail” ($15). Prices range from $18-$32 with the drinks being made from spirits like Roku gin, Suntory Toki, and Nikka Coffey Grain Whisky then mixed with stuff like Port, nigori sake, lime, orange, yuzu, smoked lavender honey, and demerara to make bright, approachable blends. The lone beer offered—Kawaba’s Snow Weizen ($12)—rounds out the menu. It also appears on the “Beverage Pairing” and is rather smooth and inoffensive.