Perhaps no other new Chicago restaurant—outside the realm of tasting menus and glitzy riverside eateries—has commanded more attention over the past half a decade than Virtue. And you do not find qualifying that statement to be unfair. Erick Williams did not trek to Hyde Park with Michelin honors on his mind, nor did the chef benefit from the barrage of publicity that accompanies splashy openings from the city’s most prolific hospitality groups. Rather, he opened the restaurant with the more measured intention of “providing the community…with a new staple.”

Williams took over the University of Chicago-owned space that had housed A10, Matthias Merges’s contemporary French-Italian hybrid, for five years and had Virtue up and running just three months after signing the lease. The chef wanted the restaurant “to appeal to a broad demographic,” to “listen to locals and adjust if needed based on community feedback,” to—in other words—“win over Hyde Park.”

At the same time, the neighborhood—due to a confluence of factors including “picky University of Chicago folks, a diverse population with wide wealth disparities, and the perennial difficulty of drawing diners and employees to the South Side”—had lacked a destination restaurant. (A10, in its heyday, could claim being “the only restaurant South of Chinatown named to Michelin’s Bib Gourmand list”). Williams would not be “asking people to pay $85 a meal, $100 a meal” but would give them the option to: “if they want to throw down, then they have a space where they can throw down.”

Virtue’s biggest draw, undoubtedly, would be stylistic: offering “American southern food” that goes beyond the stigmatized “soul food” descriptor to offer “dishes that originated in all the Southern regions, allowing diners to experience a variety of ingredients and culture.” Williams did not want “people to feel” the restaurant was “focusing on fried food.” Yet, as Eater Chicago’s editor mortifyingly put it, the chef would be “keeping it real” with items like pig’s feet fritters. Meanwhile, other hallmarks included braised beef short ribs, blackened catfish, gumbo, red beans and rice, collard greens, southern ham (with pickles and crackers), and hush puppies.

Virtue opened quietly enough on November 15th, 2018. Yet the restaurant would soon ride a tidal wave acclaim that weathered the pandemic and would earn Williams, in June of 2022, one of the industry’s highest honors. The chef was named the James Beard Foundation’s Best Chef: Great Lakes, beating out local peers like Jason Hammel, Noah Sandoval, and John and Karen Shields to take the crown.

It hardly took that award to catch your attention, yet it no doubt formed a seminal moment for Williams, his restaurant, and the community (close and far) it worked to support. Notably, the chef also formed Chicago’s sole winner across the entirety of this year’s JBF Awards categories—making something of a statement regarding the local industry’s degree of national import. Virtue has distinguished itself in an era that has seen openings like Elske, Ever, Kasama, Oriole, and Smyth battle to shape the next generation of “fine dining” (as traditionally conceived). It has succeeded wildly in forging a singular identity, cooking in a distinct style, that has redefined what the “view from the top” looks and feels like.

It goes without saying that Virtue is a restaurant of great significance that deserves the same careful study and evaluation you apply elsewhere. At the same time, it may prove rewarding to decontextualize its food, drink, and service from the tailwind provided by certain cultural movements and corresponding media narratives. For kitchens do not only cook for those who are predisposed to support their mission. Rather, their most valuable work comes from forging bonds with those who are least likely to share the table.

Free of any emotional priming or conscious notions of “allyship,” the purest experience may present itself. It may reach you where you stand and communicate something meaningful and unadulterated by expectations—or predilections—that are not your own. This position of neutrality, which you endeavor to maintain throughout all of your work, is the only posture from which transcendent hospitality can be sensed. For those superlative experiences, whenever they do strike, demand nothing more (or less) than an open heart and presence in the moment. And to cheerlead for a concept before stepping one foot through the door seems just as bad as denigrating it sight unseen, because both maneuvers venture forth a false sense of self that robs dining—the ritual of breaking bread—of its most essential power.

But you get ahead of yourself.

Erick Williams is a Chicago native who lived in Lawndale, “one of the city’s poorest and most dangerous neighborhoods,” until he was nine. As a teen, he lived in Austin and underwent a period in which “his parents feared they were losing him to the streets.” Williams changed course and set about studying English Language and Literature at Wright Junior College, yet his path from there into kitchens was far more serendipitous.

Williams had “tried to work in a Burger King” as a kid but could not get hired, and being denied that experience sapped any excitement he had about “restaurant life.” After school, he “would have went into real estate” but appeased his parents by replacing a friend who had just quit his job in a kitchen. That eventually led to “a restaurant down the street”—and to being laid off. But, walking past River North’s Hudson Club “one day in 1996,” Williams resolved to ask a man sweeping outside for a job. He would spend two years there working “the salad and appetizer stations, competing for a chance to work the pizza station,” which led to “a brief stint at the Hyatt Regency.”

Meeting Michael Kornick, however, would prove decisive. The chef of mk sensed that Williams “wasn’t a good cook” but “was just in restaurants.” Yet Kornick drew a parallel between basketball, its hand-eye coordination, and working in kitchens. If Williams “understood the difference between offense and defense” in the sport and “the importance of recovering the ball,” he could learn “how to be a good cook.” As it happened, he “never looked back.”

Williams would start at mk in 1998 and work there for nearly nineteen years, rising to the position of executive chef and stewarding the restaurant until the day it closed (due to a “landlord dispute”). Though you never ate there during its time, the concept “was extolled for his farm-to-fork, seasonal approach” and “amassed a fiercely loyal patronage while consistently receiving accolades from coast to coast.”

Looking through archival menus (comprising the period from 2013-2016), you note bites like artichoke hummus, asparagus (with serrano ham), bison tartare, blue cheese-stuffed dates (with prosciutto), crab toast (with truffle cream), figs (with feta and honey), fried chorizo-stuffed olives, fried goat cheese-stuffed squash blossoms, and sweet potato agrodolce.

Smaller plates included charcoal-grilled baby octopus (with merguez sausage), an octopus terrine, butternut squash ravioli (in brown butter), chicken consommé (with poached black truffle dumplings), chilled Maine lobster (with persimmons), lobster bisque (with black trumpet mushrooms), English pea soup (with Jonah crab), foie gras torchon (with peaches), kampachi crudo, roasted baby artichokes (with pickled white asparagus), “two tartares” (of tuna and salmon), seared scallops (with pistachio vinaigrette), shrimp (with dill silk “hankies”), soft-shell crab, summer vegetable tian, and veal sweetbreads (with morels).

While entrées spanned items like pan-seared bass (with maitake mushrooms), bouillabaisse, pan-roasted fluke (with hollandaise), pan-seared haddock (with fennel-pimentón hollandaise), peppercorn-crusted tuna (with red wine syrup), seared walleye pike (with spring green onion kimchi), whitefish (with poached Maine lobster and coconut broth), bacon-wrapped monkfish tail, grilled salmon (with ginger soy vinaigrette), grilled swordfish (with chanterelles), tempura-fried morels (with Aleppo pepper aioli), pork tenderloin (with rosemary pork sauce), venison loin (with huckleberries), roast lamb (with ash-roasted eggplant), roast duck (with rhubarb gastrique), bison ribeye (with salsa verde), squab breast (with foie gras and natural jus), molasses-glazed short ribs (with “Geechie Boy” grits), and prime sirloin steak (with red wine sauce).

Special tasting menus included “A Celebration of Sonoma Wines” and “The Bounty of Chicago Farmers Markets” (with a note on the standard menu stating that “mk supports Chicago’s Green City Market, sustainable agriculture, & organic farming). Also listed were the titles of artwork featured throughout the restaurant, along with the names of their creators.

Overall, these dishes—with regard to ingredient sourcing, advanced techniques, and wide variety of influences—strike you as noteworthy for the era. In particular, you are drawn to the number of classic, hearty forms that are enlivened by some component that is seasonal (or, simply, unexpected). There is no question that the food intends to please; however, it balances guest pleasure with a tinge of thoughtfulness drawn from a distinct culinary philosophy: the aforementioned “farm-to-fork” approach.

It is not hard to conceive of how Williams endeared himself to Chicago diners by offering this sort of refined yet accessible fare within one of the city’s burgeoning neighborhoods. Likewise, it must be said that pursuing this kind of seasonal cooking for the better part of two decades amounts to a rare kind of experience that is often drawn only from even finer (i.e. strict tasting menu) forms of dining. The chef’s work at mk, as best as you can perceive it, offered invaluable experience serving artful, carefully sourced cuisine to a more mainstream demographic than would necessarily seek out the set menu, jacket required, white tablecloth style of restaurant for a great meal. Reaching this aspirant population and affecting how they view food will, by your measure, always prove more valuable (for both the chef and society’s growth) than catering to self-described gastronomes.

As Williams mastered his craft over those years in the kitchen at mk, the chef started to think of what might come next: what his “place was,” where his voice “was going to have the most resounding sound.”

He met with his father, who imparted a precious lesson from the realm of music: “look, all musicians want to go out and do jam sessions. Everybody with an instrument is excited about doing a jam session. But the best improvisation comes from people who really understand the standards. If you don’t understand the standards, you don’t leave a trail—you’re just playing a bunch of notes, there’s nothing anybody can follow.”

Williams would, years later, find an easy parallel in the world of art via Kerry James Marshall, “recognized as one of the most important African-American painters of our time.” Marshall, talking about mastery, described “how, as a young painter, there were no images of African-Americans to paint. There weren’t many people for him to ask for tips as he wanted to hone in on that particular skill set. So he was going to master the platform that was given to him, which was the art of painting white figures. And once he mastered that, and people recognized that he was the best in that category, then he’d be able to do whatever the hell he wanted to do.”

At mk, Williams was watching a video of Marshall while talking with his chef de cuisine when everything clicked. They had already been discussing, at that time, “a need in our community—a need for someone who looked like me to be able to speak intelligently about what our food means, about what the relationships in this community mean to us, and what service that provides—merely to our team.”

And that notion of mastery, as described by the renowned painter (and in relation to what Williams’s father described about music), formed the key. The chef had “been doing this long enough, and at a high enough level, to do whatever the hell I want to do.” He would embrace the food that he “never thought about cooking—Southern food, because it was so common.” He would cook it and “cook in a way that showed respect, and homage, to our ancestry. That provided space for our culture.”

The door would be open to “anybody that wants to walk in.” But the place would also be “unapologetically black.” In other words, “the art’s black, the people that are serving you are black, the people that are cooking are black, the people that run the place, own the place, and the investors are black.”

Williams would embrace the idea that “there aren’t many spaces like this” and “embrace it in a way that makes it a lot more palatable for people that don’t look like us.” However, “for folk that do look like us,” it would “carve a clear path to how you become successful in a way that is dignified, first and foremost, but also that amplifies the fact that you will not get here unless you plan on working your ass off. And it doesn’t matter what color you are.”

As these ideas regarding a restaurant that would serve and inspire Williams’s community swirled, a Crain’s Chicago Business article from 2016 underlined to just what extent the chef had already dedicated himself to doing just that.

It described his return to Lawndale in 2007 with wife Tiffany, an elementary school principal. Despite knowing the neighborhood to be “dangerous,” the two explained that they “think it’s necessary for people who are successful to be in the environment to help offer a glimmer of hope.”

Williams had previously shied away from sharing his personal history because “he didn’t want to give people the room to think all people of color had a blighted past” and “didn’t want to be categorized.” Yet the chef eventually realized that his “own agenda was hindering a bigger agenda—to show kids they could avoid obstacles” and “to help kids so they could hear stories they could relate to.”

To that end, he worked with Embarc—“a local high school program that helps inspire low-income kids to strive for high school and college success”—and kids from CSW Career Academy, arranging for them “to spend time cooking in the mk kitchen.” The pivotal moment occurred when “a group from Englewood approached him to mentor their kids as well.”

The group leaders “told Williams he couldn’t have kids cross gang boundary lines,” but the chef was undeterred. One day in 2013, he “invited 40 students from Englewood to mk for a meal of roasted chicken and potatoes, sautéed spinach and Caesar salad prepared by the eight CSW kids from Lawndale.” The “tension” of two groups from “two sides of town” mingling was defused by the act of cooking. Each side “realized where the other was from” and “boundaries started getting lifted.” The students from Englewood told those from Lawndale “the food was good, thanked them, and that turned things around.” In Williams’s words “there is nothing that can’t be solved over a meal if you have the patience to solve it.”

This idea—constructing community through the act of cooking, cooking from the heart on the basis of a hard-fought mastery—formed the spiritual core of what would become Virtue. But, as that larger sense of purpose simmered and mk inched towards the end of its lease, there were still a few more important pieces yet to fall into place.

Williams would tap Jesus Garcia, another alumnus of Kornick’s restaurant, to be his general manager, beverage director, and business partner in the new venture. The pair’s careers, in truth, seemingly paralleled each other. Garcia was born in Mexico and raised on the North Side of Chicago. He started his career as a back waiter at mk and knew “in an instant” he had found his calling: “the ability to make a positive imprint on someone’s day or occasion through hospitality.”

Garcia and Williams became “fast friends” while both at mk and, respectively, rose through the ranks. The former would leave after four years to go work in Minneapolis yet, in due time, would return to Kornick’s restaurant in a management position. Just two years later, Garcia rose to become mk’s general manager and would work in a similar capacity at The Bristol before reuniting with his “longtime friend, colleague, and mentor” to open Virtue.

The pair form a powerful combination not only due to their shared experience—learning the same dishes, pleasing the same customers—at the longstanding River North concept. Rather, Garcia—like Williams—started at the bottom of the industry and knows his entire team’s responsibilities inside and out. He knows the kind of motivational structure and personal growth required to cultivate talent—even from unlikely sources—and, thus, forms a natural leader and “passionate advocate for the community” in the same manner as his chef-partner.

For his chef de cuisine, Williams would draw on the talent of Damarr Brown—who, thanks to his four-place finish (and “fan favorite” status) during season 19 of Top Chef, has attained a level of fame every bit equal to that of his boss.

But, prior to that breakout moment, Brown honed his craft for seven years at mk with Williams as his “mentor.” That period was followed by two years at Roister under Andrew Brochu (who, in his time there, instilled the live-fire Alinea Group restaurant with the only sense of identity and direction it has ever had). Brown’s “strong reputation and relationship” with his former executive chef must have made joining Virtue an easy choice. However, he forms a perfect philosophical fit too.

Brown shares the belief that “all cultures celebrate, grieve, and come together around a table”—an idea that is very much kindred to the kind of community Williams endeavored to build through the restaurant. Being the very same chef de cuisine who shared in the inspiration of Marshall’s treatise on mastery back at mk, it is no surprise that the Top Chef ace believes strongly in Virtue’s “inclusivity” and “culture of equity.” Brown, like Williams, finds in the Hyde Park restaurant a venue in which to draw from the “familiar flavors he grew up with” while pursuing a “continual search for new or forgotten flavors and technique[s].”

The last piece of the puzzle would come from Becky Pendola, former pastry sous chef at Sepia and Proxi who had started her career as a pastry assistant under Lisa Bonjour at mk. She had previously graduated Kendall College at the head of her class and, like Brown, is an “avid researcher of vintage recipes.”

Stylistically, Pendola’s pastry work “strives to wow patrons” by concentrating “the flavors of classic desserts” and blending them with “unexpected presentations.” This philosophy is anchored to a belief that “guests should leave the restaurant feeling cared for and welcomed as if they were visiting a friend’s house.” However, like her colleagues, the pastry chef displays a wider commitment to “feeding the homeless community” and providing “equitable space for the BIPOC community” at her restaurant alongside Williams.

When Virtue opened in November of 2018—nearly a year and a half after mk held its last service—the restaurant could rely on this crack team, forged in Kornick’s kitchen under Williams’s command, to realize its vision. While it would have been tempting to term the Hyde Park spot a spiritual successor to the River North stalwart, the former’s unique identity was affirmed.

That sense of character was rooted, among a multitude of aesthetic elements, in the “tributes to Aretha Franklin and James Brown” that featured in the space. They would not only reflect the concept’s “unapologetically black” influence, but also connect back to the musical inspiration that first captured Williams and Brown’s imagination. Speaking of Beyoncé—“a modern African-American icon”—the chef-partner connected the dots between the two artistic domains: “at the end of the day, that woman puts on a full performance—in heels—and if she misses a beat it’s hard for you to detect it.” That’s the attitude he would look to instill in his team so that they “can get that done in the front of the house and back of the house” each and every night.

Within a week of opening, Virtue would face one of its most notable tests—hosting former President Barack Obama. 44 “was one of the first guests in the first few days,” capping off a debut described as “much anticipated and celebrated by South Siders.” Yet despite hosting this famed guest right at the start, the restaurant proved too new, too untested to feature among local media’s year-end “best of 2018” filler.

Nonetheless, the new year would see the upstart take its turn in the critical crosshairs—and impressions were good. Awarding the restaurant three stars (“excellent”) that January, the Tribune gushed that the concept “oozes both Southern charm and urban sophistication” and offers a “winning combination of technique, nostalgia and personality.” Virtue, in Vettel’s words, would “prove to be not only a very good restaurant, but also an important one.”

In February, Time Out would agree, awarding the concept five stars (“unmissable”) and declaring that Williams “surpasses lofty expectations” by capturing “the depth and scope of Southern cooking with soul-satisfying results.” So, too, would Chicago magazine (albeit more than a year later)—awarding two stars (“very good”) and declaring that Virtue “solves the Hyde Park puzzle” by “conquering” its “prickly” community with “an infectiously upbeat vibe that other restaurants strive for but rarely achieve.” This latter article, from February of 2020, could praise Williams for “hiring and mentoring fellow African Americans” as the chef-partner intended. By that point, customers were “pouring in from Lincoln Park, Highland Park, and Schaumburg and becoming regulars.”

But the rest of 2019 was still a watershed year for Virtue—even if additional local media coverage was rather limited. In April, the restaurant began offering Sunday brunch service (which, sadly, has yet to return). In July, it would rank as “the sole Chicago representative on Eater National’s Best New Restaurants of 2019” on the basis of its “culinary inspiration” drawn from “many of the Southern states,” “from Chicago,” from Williams’s fine dining background, from the chef’s family history, and “from the world.”

In September, Virtue would reclaim A10’s former mantle as “the only restaurant South of Chinatown named to Michelin’s Bib Gourmand list.” It would join Nella Pizza e Pasta (also of Hyde Park) as two of only 14 additions to the list of “friendly establishments that serve good food at moderate prices” during a year that also saw 18 Chicago restaurants excised from the selection. Bibendum described the space as “an inviting retreat with a welcoming bar, striking dining room, and buzzy kitchen helmed by the very talented Erick Williams,” who offers “well-executed Southern cooking.”

In November, Williams would be nominated for the 2020 Jean Banchet Awards “Chef of the Year” honor—though the chef was ultimately bested by Anna and David Posey of Elske. However, that same month, Virtue also ranked #13 on Esquire’s “Best New Restaurants in America, 2019” list. Jeff Gordinier was tickled by a menu that seemed “like a spread at a family reunion piled high with dishes that inspire such love” and, in particular, by a dessert called “we finally got a piece of the pie.” (Never afraid to gild the lily, he sneered “if you don’t get the reference, or the extra layer of meaning behind it, I’m not going to explain it to you here.”)

In December, Eater Chicago followed in the footsteps of its national mothership and honored Virtue with its “Restaurant of the Year” award—citing its “level of execution, pedigree, hospitality, and impact” in combining “fine-dining technique with American Southern soul.” (Williams had also been nominated for “Chef of the Year” but lost out to Jeong’s Dave Park).

2020 brought more good news, as Williams was named a semifinalist for the James Beard Foundation’s “Best Chef: Great Lakes” award. He would, in May, be named a finalist alongside Gene Kato, Jason Hammel, John and Karen Shields, Noah Sandoval, and Lee Wolen. However, by that time, the industry had been utterly rocked by the pandemic, and the James Beard Foundation—ultimately—would choose not to present any winners that year.

COVID-19 would test the mettle of Chicago’s restaurants, mercilessly shuttering some spots while rewarding chefs who displayed flexibility and creativity under duress (though often with nothing more or less than mere survival). Williams would, upon the shutdown of indoor dining, immediately pivot towards offering Virtue’s dinner menu and daily family meals for curbside pickup. But the pandemic would prove even more consequential in defining just how far the sense of community the chef had labored to build actually reached.

In March of 2020, as the reality of the situation took hold, Williams sounded an upbeat note. “I believe that our community is going to gel and we’re going to be better on the other side of this—more efficient, more communicative, more of a united voice,” he said. “We haven’t had anything like this that’s brought the entire city together around our cause…[restaurants] have been the backbone of the philanthropic community in this city for years. Every event, every occasion…chefs have gone above and beyond to make sure those experiences are lasting….Now we need help, and I look forward to seeing how organizations, groups, and our political officials are going to step up to rally around this cause.”

The Payroll Protection Program would—albeit imperfectly—shoulder some of the burden of the forced closures. Targeted relief, like the Restaurant Revitalization Fund, would take more than a year to come to fruition. Yet Williams would not have to worry that his “countrymen and women were going to bail out large industries like the airlines and leave the lifeblood of our country, the restaurant community, behind.”

Quite the opposite was true, in fact, as Virtue found itself in a position where it could look outward towards others in need of assistance. Williams had launched a GoFundMe in mid-March—concurrent with the closure of indoor dining—to “secure the stability” of his team and “respective community.” With that support, the chef was able to close the restaurant’s takeout operation in late April and focus “solely upon providing meals to our city’s first responders.” His team had already been providing meals for workers the University of Chicago Medical Center, but donations—alongside an outlay from investors—would empower the restaurant to further support healthcare professionals throughout the city and “also provide jobs to friends who are currently unemployed due to the pandemic.”

In late May, Chicago was set to open for outdoor dining—with at least “six major streets” closed “to make room for restaurant tables and chairs.” But the death of George Floyd sent shockwaves throughout the country, prompting demonstrations and riots within the city that dealt a beleaguered industry another blow. While chefs grappled with their moral and social obligations during a period that had already been so difficult for business, Williams distinguished himself by using his platform to share fervent, forthright posts in pursuit of justice. During a period of such volatility, his self-written content worked to build a thoughtful, good faith dialogue that resisted the heightening polarization seen across the nation.

Williams, if there was ever any doubt, backed up his words with action. He joined more than 30 other chefs—including Carlos Gaytán, Paul Kahan, and Mariya Russell—in a “coalition cookout” aimed at easing tensions between the Black and Latino communities in the wake of looting. The chef later teamed up with future Michelin-star awardee Galit for a week-long “Hummus & Pals” special (made with cauliflower and chow chow) with all proceeds supporting Brave Space Alliance.

As part of that year’s Chicago Gourmet festival, Williams hosted a candlelit, four-course “Dinner in Black” at Virtue—where guests were required to dress from head to toe in the titular shade—in honor of George Floyd. Then, as part of EXPO Chicago, the chef headed a $750 virtual dinner benefitting Enrich Chicago—“a collaborative of over 40 Chicagoland arts and philanthropic organizations…committed to ending racism and systemic oppression in the arts sector.”

At the end of July, Chicago magazine honored Virtue with the title of “Best Restaurant That Lives Up to Its Name” in a special issue dedicated to “79 Extraordinary Ways the City Has Shined Through Turbulent Times.” All the while, Williams and team were welcoming guests back on their patio—and, later in June, indoors—and serving food in person once more. “Infinite Hope is a Virtue,” the concept roared (by way of fresh graphics from artist Jason Pickleman). It was joined by four other statements—“Helping People is a Virtue,” “Caring for People is a Virtue,” “Aiding Others is a Virtue,” and “Patience is a Virtue”—that might just serve to encapsulate the attitude with which the restaurant weathered 2020’s difficulties.

The second ban on indoor dining—beginning at the end of October—took the wind out of many a restaurant’s sails. Virtue, however, benefitted from a $5,000 “winterization” grant from Doordash. And, certainly, nothing would stop Williams from continuing to serve his community. That took the form of a takeout Thanksgiving meal, a complimentary family meal for 100 hospitality industry employees in need, a virtual toy drive for Comer Children’s Hospital, and continued advocacy for restaurant relief.

When indoor dining resumed in late January of 2021, Virtue was among the first restaurants to open its doors. Williams would celebrate Black History Month with a series of “things one should know” posts and a “Shoebox Meal” collaboration with Patrick Coleman of Detroit’s Beans & Cornbread—named thus in honor of the latter’s mother and great grandmother, “who were barred from eating in train dining cars during the Jim Crow era…[and] packed their own lunches in shoeboxes.”

In April, Williams was honored with Chicago’s inaugural “Mayor’s Medal of Honor” for his “commitment to promoting social justice and donating meals to frontline workers.” That same month, Virtue would retain its Bib Gourmand. And, with the darkest days of disease and strife behind it (but so much more work to do), the restaurant could set about pursuing its original vision—which included, in December of 2021, the opening of the “approachable and affordable” American takeout spot Mustard Seed Kitchen on the Near South Side.

2022 has, thus far, seen Virtue go from strength to strength: January saw the announcement that chef de cuisine Brown would be competing on Top Chef, February witnessed the return of the Black History Month “Shoebox Meal” collaboration, May dealt Williams his Jean Banchet Award for “Chef of the Year” (and Brown a fourth-place finish on the cooking competition show), while June was undoubtedly defined by the executive chef’s “Best Chef: Great Lakes” win at the James Beard Foundation Awards.

That brings us to the present day, in which Virtue has all the plaudits, celebrity chef fandom, and weight of expectations it could ask for. Williams has even expanded just up the street, opening Daisy’s Po’ Boy and Tavern in order to offer the neighborhood grab-and-go comfort food and “create amenities that both support the community and support this idea of ‘kind hospitality.’” Relative to Virtue, Daisy’s would provide an “outlet” to retain and grow his team “so that they can continue to elevate up the ladder,” signaling that—perhaps—even further expansion is in store.

This crest presents the perfect opportunity to assess Virtue in the prime of its operation and judge it both on the basis of its singular quality and against the great pantheon of Chicago hospitality you have labored to build. There can be little question of the buoyant spirit Williams has imbued his restaurant (and the wider community) with, but the nature of its execution—and the ability to successfully extend that hospitality more broadly—stand ripe for analysis.

You have visited Virtue three times during a period that spans early May to late July of this year. While this narrow window robs you of the chance to appreciate the full range of the restaurant’s seasonal offerings, you feel comfortable basing your evaluation on the degree of change you have witnessed throughout this three-month period. As is typical, you will condense the sum of your experience into one comprehensive narrative.

With that said, let us begin.

Visiting Virtue inevitably means—for Chicagoans whose lives revolve around the West and North Sides of the city (and their outer suburbs)—winding down Lake Shore Drive and appreciating the array of museums, parks, and beaches that line the way. For those associated with the University of Chicago—an institution that is tacitly associated with the restaurant but whose Main Squad actually lies nearly a mile and a half away—visiting Virtue means making a jaunt northeast towards the commercial part of town that also boasts a Trader Joe’s, AKIRA, Whole Foods, and Marshall’s.

For longtime residents of Hyde Park, Virtue might just represent one of the crown jewels of the 53rd Street TIF district established by the city government in 2001. A single restaurant might not seem as consequential as a six-story Hyatt hotel, rehabilitated middle school, or 180-unit Studio Gang-designed apartment building, yet it now forms a destination just as much as it does a neighborhood amenity. Virtue draws outsiders into a community that no longer—save for the Museum of Science and Industry—need stand apart from conventional Chicago tourism. It connects local stakeholders with a wider population that may help sustain the area’s wider revitalization.

But none of that necessarily comes to the fore as you exit off of Lake Shore and turn onto 53rd. The street looks an awful lot like any other anonymous urban sprawl: Starbucks, Roti, Chipotle, GNC, Nando’s, Subway, Five Guys, Dunkin’, Boston Market, and sweetgreen line the way. But there are signs of life too. Local salons and eateries make up some of—most notably the cash-only Valois, “one of the oldest cafeteria style restaurants in the United States” that has been in existence for some 101 years across three different locations in Hyde Park. The restaurant, which hosts “a combination of every socio-economic class, all different ethnicities and what really encapsulates Chicago” according to its manager, speaks to the same kind of community feeling Williams has sought to build.

Virtue, nonetheless, would not share Valois’s French-Canadian roots—it would center, instead, on that cornerstone of “unapologetic blackness” and serve the community from that posture. This particular perspective can first be noted when reading the text emblazoned on all but one of the restaurant’s windows. Last year, white signage proclaimed “I Can’t BREATHE,” “I Can’t Lawfully Carry A WEAPON,” “I Can’t Look Out THE WINDOW,” “I Can’t Leave A PARTY,” “I Can’t Relax In MY OWN HOME,” “I Can’t SELL CDs,” “I Can’t Go To CHURCH,” “I Can’t Watch BIRDS,” “I Can’t KNEEL,” and “I Can’t JOG.” Recently, Virtue has slightly tweaked the display by stenciling the text directly onto the glass alongside associated names like George Floyd, Breonna Taylor, Jennifer Pinckney, Ahmaud Arbery, and Jordan Edwards.

The display sends a strong statement that reflects Virtue’s commitment to social justice yet, at the same time, draws attention to the victims themselves and the tragically mundane circumstances surrounding their deaths. By sidestepping more divisive, politically-charged language, these installations strike you as disarming, broadly relatable, and effective at penetrating any instinct to discount the human toll of the referenced events on account of pigheaded partisanship. Williams speaks, in a poignant way, to the effect these killings have had on his community. He invites guests to share in his grief—his fears—without tangling, just yet, with the thornier processes of legislation and prevention.

As striking as its signage is, Virtue’s building cuts an attractive figure on the block. Matching the Prairie-style Harper Theater (built in 1913) that runs alongside it (and that, in fact, the space was once a part of prior to renovation), the restaurant’s façade combines red brick, white stucco accents (including filled flowerbeds), dark grey window frames, and black awnings. “VIRTUE restaurant & bar” dominates the corner window—with two hanging signposts on either side of it. The font is bold and burnished. It is matter of fact like the theater’s glowing letters, but close inspection reveals the fine touches of a flowing hand.

Virtue’s name is repeated across the set of front doors at the ornate main entrance—complete with mosaic tile—off of 53rd (while there is also, it should be noted, a separate bar entrance down Harper Avenue towards the marquee). There is a sense of scale—and corresponding quiet dignity—to the building. It conveys a kind of permanence that is perfectly suited to Williams’s community goals.

Stepping through those doors, that outer sense of austerity transitions into a more artful aesthetic punctuated by flashes of color and texture. It all begins with the host stand, which is rendered as a monolithic slab of bright white (matching the exterior accents) and offset by dark flooring. Behind that, set onto a bar positioned just a couple feet beneath the high ceiling hangs a patterned curtain. It draws your eyes upwards towards the chandelier—a glass and metal number with a retro-industrial feel—and the wallpaper that runs along the back wall (only a thin strip of which is visible in the gap between the top of the curtain and the ceiling).

It takes half a second to note that the pattern of the curtain and the rear wall it largely obscures are exactly the same, comprising a series of spindled wheels with squiggled markings set in uneven rows. The image evokes a sense of the handcrafted and of the fine details (or even captivating imperfections) that accompany heritage artisanship. At the same time, the design’s neat, circular nature and staggering repetition across the two surfaces lends the symbol a sense of centrality and power. This visual element breaks from the outer sternness of the edifice, invigorating and directing it towards the notion of craft, without totally defusing the building’s effect.

Though Virtue certainly weathers a perpetual flow of walk-ins on any given evening, the host stand is manned cheerily and the crowd of people that packs the entryway is kept moving. You might, while waiting for your turn, have just enough time to appreciate The New York Times’s “16 Black Chefs Changing Food in America” feature that honors Williams and has been rendered in poster format on one of the walls. Perhaps you might also take a peek into the bar area located through the doorway to the right of stand—a part of the establishment you have yet to appreciate firsthand (but that, in practice, forms a key part of its identity).

Booking any primetime reservation in the dining room demands—more or less—two weeks’ notice, yet this separate space assures locals that Virtue can live up to being a neighborhood haunt no matter how brightly the restaurant’s star shines. The bar features nineteen sturdy, backed stools (separated into banks of seven, five, and seven) surrounding a polished brass surface. Spirits—including a boatload of bourbon and, prominently, the restaurant’s own line of vodka—occupy a hanging shelf situated overhead the side closest to the curtained windows facing Harper Avenue. Light fixtures, executed as thick discs of glass, also dangle from the ceiling. There are a few televisions placed behind the bar and in the corner closest to the entrance. Otherwise, canvases tend to occupy any open space on the stark white walls.

While the brass bartop is complemented by metal accents drawn from the stools, fixtures, and shelving, the room really sets its tone through the use of wood. The dark grained flooring is offset by lighter grained tables and chairs. Trios of two-tops line the windows and the wall closest to the host stand. The center of the bar room, meanwhile, is defined by a sextet of four-tops arranged on the diagonal. This orientation serves to break guests’ sightlines with the rectangular counter and invites standing patrons to more easily post up throughout the room. However, just as easily, the four-tops may be broken up and recombined to seat a party of twelve.

When the sun is up, the bar brims with natural light and the energy of all those wrangling for a bite or a drink—particularly during happy hour, which features specials like four-piece wings ($12) and catfish sliders ($4) alongside house wine and cocktails. Under cover of darkness, the room maintains a moody glow drawn from its glass lanterns and invites customers to tuck in for a longer stay. No matter the moment, this space offers Virtue an estimable degree of flexibility with which to cater to its surging crowds (and even to screen select sporting events or episodes of Top Chef).

At the same time, given the likelihood that visitors from afar will aim to secure seating at an early hour, the room increasingly opens up to locals as the evening winds down. They can afford to wait around a little longer or slide in later on—fueled, no doubt, by some familiarity with how good the fare is. The community, thus, is not disadvantaged by all the positive press and resulting tourism: “the customer who sits at the bar three nights a week with his biscuits and glass of Zinfandel” can find a home. Maintaining this kind of accessibility for Hyde Park residents while continuing to impress those who come from afar (with reservations in tow) forms an essential part of the Virtue ethos. It provides Williams and his team with an all-important venue to connect with their neighborhood on any given night.

The space opposite the bar can be accessed by passing through to the other side of the host stand or navigating a rear connecting corridor that contains the restaurant’s bathrooms. Both paths inevitably lead to the dining room, an area about double the size of what is reserved for walk-ins. The overall aesthetic, nonetheless, remains the same: white walls, dark wooden flooring, lighter wooden furniture, hanging glass lanterns, and plenty of natural light drawn from the windows overlooking 53rd.

Spatially, the rear (western) wall of the dining room is defined by the open kitchen. Most of its workings are obscured by a low wall (that also sometimes acts as a shelf for stacks of plateware), yet it is hard to miss the black tile backsplash and stainless-steel paneling that distinguish the line. There’s a service station—stocked with glassware, utensils, and more plates—situated at the end of dividing wall closest to the windows. At the other end—in the corner furthest from the entrance—the counter dips down to form the pass. From there, Williams, Brown, and/or Garcia will run the show—the closest table of guests being seated only a mere few feet away.

The center of the dining room, stretching out from the central point of the kitchen, comprises a double-sided banquette each made up of three four-tops. Past that, running along the eastern wall that faces back at the line, is another banquette lined with three two-tops and one four-top. Closest to the windows, in the corner nearest to the entrance, there’s a six-top banquette. It is followed by two four-tops and a sole two-top running towards the kitchen. Finally, along the wall closest to the pass (and nestled within a partition that allows egress from the line), there are two freestanding six-tops. That brings the total number of seats in Virtue’s dining room to 62, with the modular nature of the two-tops and four-tops allowing for a variety of permutations based on party size.

Ultimately, the room’s energy flows out from the kitchen, crosses the three central banks of tables, and reverberates against the banquettes facing back towards the pass. Servers scurry back and forth on the three avenues formed between all the seating. These neat blocks of patrons—staged throughout one singular room—yield the feeling of communal dining. As does the relatively low elevations of the chairs, which serves to more starkly distinguish the height of the servers from all those being served. But guests, no doubt, are seated comfortably apart—you simply get the sense that you are rubbing elbows and sharing, to some extent, in a mutual experience.

The dining room’s most striking flourishes come by way of art, which weaves a degree of soul into a space that, otherwise, is comfortable without being particularly memorable. One mainstay has been the tobacco baskets—made from strips of oak—that hang from the ceiling. So neatly are the vessels arranged, so comprehensively do they command your attention overhead, that you first thought them to be some kind of abstract lampshade. Nothing outwardly suggests the objects’ identity until you come across, or perhaps solicit, further information.

Then, masterfully, their meaning takes hold of you: the baskets hang as an eternal reminder of the Colonial tobacco plantations, which not only formed an essential part of the early American economy but demanded (relative to rice and cotton) skilled, careful labor from their slaves. It is unclear whether the baskets, too, were crafted by slave labor. It is ironic that the vessels feature, in other settings, as an innocuous piece of interior design. Here, at Virtue, you may say that each tobacco basket represents—at the very least—the agony of a skilled artisan whose life was condemned to servitude. They offer an elegant reflection, perhaps, on what it means for the kitchen to cook for their own community on their own terms.

While the baskets have formed a perpetual presence in the dining room, the rest of the space has laid home to a rotating collection of black artists drawn from Williams’s “commitment to supporting and amplifying” their voices through the restaurant. On each occasion, the chef is sure to share his enthusiasm for the pieces and communicate some of what they bring to his space.

Currently, Williams is featuring works from UChicago professor, installation artist, and “longstanding friend” Theaster Gates throughout the restaurant. In the bar, that includes Black Image Corporation (images drawn from the archives of the Johnson Publishing Company) and Race Riot (made from decommissioned fire hoses). In the dining room, Gates’s works include Civil Tapestry (another piece made from these hoses, representing their “use against largely Black and Brown protestors”), Tar Paintings (inspired by the “signifying materials and skilled labor of roofing,” his father’s profession), and Mountain Aura (an abstract, neon visualization of W.E.B. Dubois’s sociological findings regarding African American households) as well as several large ceramic vessels (inspired by traditional Japanese pottery) set between the central banquettes.

Many of these pieces, like the tobacco baskets, prompt a moment of pause and—once the secret of their construction is revealed—a period of deep rumination. However, during the bustle of service, it is easy for the art to fade into the background and function more as ornamentation. The point is not to disturb or consciously provoke but, rather, represent the kind of art that the community can meaningfully engage with should they choose to. Meanwhile, visitors, even if the larger context escapes them, are treated to an extension and enrichment of Virtue’s culinary mission in a strictly visual domain.

Virtue’s rotating artwork proves infinitely more rewarding than the banal Thomas Masters canvases that have littered Alinea since its renovation. By offering some degree of depth to discover (and, potentially, drive conversation), Williams’s curation reflects a degree of engagement with the wider community that Jenner Tomaska—who worked under both Achatz and Williams—has woven into Esmé as well. Visual art and the art of cuisine can both shine as expressions of local terroir, but they do so most effectively with a bottom-up (rather than top-down) approach to sourcing. A restaurant’s walls—and its plates—are best wielded to give voice to small-scale artisans rather than rewarding luxury ingredient conglomerates or dilettante gallery owners.

Your party is led to its table, and you take your seat. The cushioned armchair feels both solid and comfortable—inviting you to stay a while. Those seated in the banquette opposite you, too, benefit from an assortment of throw pillows that may be used to adjust their posture. Having settled in, a busser comes by with water in short order. He seems young—and a bit green—but offers the most earnest of greetings. The busser fills a couple glasses, notes your request for sparkling water, and returns with it almost immediately. He states that the server will stop by shortly and leaves you with the warmest of wishes to enjoy your meal.

It will take a few minutes for the waiter or waitress to greet the table, but, for the moment, you have everything you need. A printed spirits list is already perched on the table, containing a pair of QR codes that lead to the beverage list and dinner menu (also accessible via the restaurant’s website). You turn your attention first to the drinks.

Virtue’s “Southern Cocktails” comprise a selection of nine rotating offerings (priced from $14-$16) made from spirits like bourbon, cognac, gin, mezcal, rum, rye, tequila, and vodka. Of these, rum—which must naturally call the dark history of sugarcane plantations to mind—is well represented. You have sampled and enjoyed both the “Strawberry Fields Forever!” (mixed with strawberries, lime, and cane sugar) and “Caribbean Daiquiri” (mixed with guava, cane sugar, and citrus) for their balanced booziness and sense of refreshment.

That forms something of a consistent theme for the bar program—at least during spring and summer—when ingredients like blueberries, strawberries, pineapple, lime, coconut, grenadine, peach tea, and orange or raspberry liqueur appearing across the board. You even recall one offering from a few months ago, titled “Pass the Peas,” that combined the titular ingredient with gin and mint. (The team will also experiment with one-off specialty cocktails made from that particular day’s fresh ingredients).

No matter how fresh and fruity the seasonal selection may be, the “Hyde Park Sazerac” (made with rye, absinthe, and a mix of old fashioned and lemon bitters) forms a notable mainstay. Referencing the classic New Orleans cocktail and connecting it to Virtue’s neighborhood sends a strong statement regarding the nature of local tastes and a sense of shared belonging that transcends the distant communities. The Sazerac joins the “Brown Fashioned” (made with reposado tequila, mezcal, “Aztec chocolate,” and piloncillo) on the more robust side of the spectrum. There’s also the “Patience Is a Virtue”—first made with cognac, amaro, pear liqueur, and barrel-aged bitters back in 2018 but now constituted of vodka, raspberry liqueur, and rhubarb bitters today.

What you like, across each of these cocktails, is the streamlined nature of the compositions. The bar team does not look to flatter patrons with far-flung ingredients or pretentious, mixologist presentations. Rather, their creations—spanning pretty much every major spirit at any given point in time—reflect the elegance of just three or four components blended perfectly together. This makes for drinks that are eminently accessible and easy to enjoy—round after round—while posting up at the bar or tucking into a meal. This quality, perhaps, characterizes what the menu means by “Southern.” They are cocktails that warmly wash over you and bring you to a place of bliss.

The beverage selection also features an alcohol-free option titled “The Hummingbird” ($6) and made with basil, bitter lemon, and soda. It sounds simple enough (just like the cocktails themselves) but has been offered since opening (and resists drawing on the Seedlip products that have perniciously expanded across the city’s bars). Virtue also stocks a handful of beers from Estrella, Goose Island, and Founders—the latter of which was embroiled by accusations of racism a couple years ago. While Chicago’s Fifty/50 Group has continued to banish the beers from their menus even after the resulting lawsuit’s settlement, might Williams be giving the company’s leadership a chance to right wrongs within the industry? The inclusion of Founders could very well represent a joint path forward.

However, the wine—as always—is where things get interesting for you. Particularly since mk, back in the day, was known for its broad domestic and European wine list (with the restaurant even contracting its own private label from winemaker Bob Lindquist). And Williams, if one is to look through the chef’s social media, clearly maintains a high appreciation for fermented grape juice. But how would he foster the timeless interplay of fine wine and food at a new concept for a community far removed from River North?

At the “by the glass” level, Virtue aims for an accessible, representative selection of varieties priced in the same range as the cocktails ($14-$16) for a six ounce pour. While you must admit that you lack familiarity with most of the nine featured bottles, they are thoughtfully chosen.

For example, the Francois Montand Brut Blanc de Blancs is made in the méthode tradtionnelle from grapes sourced from the Jura and offers some of Champagne’s appeal at a rather affordable price ($14). The same can be said for Thierry Delaunay’s 2021 “Le Grand Ballon” Sauvignon Blanc ($14), a crisp expression of the grape sourced from the Loire; Fleurs de Prairie’s 2020 Rosé ($14), a salmon colored Provençal-style wine from the Languedoc; and the 2019 Côtes-du-Rhône from Famille Lançon ($14), which offers some small taste of the producer’s renowned Domaine de la Solitude Châteauneuf-du-Pape for a fraction of the cost. While, by comparison, The Guide’s 2020 Pinot Noir ($14) is a bit less distinguished of a choice, the wine offers a light, red-berried expression of the grape that you think will satisfy expectations relative to something more robust (like the aforementioned Rhône).

More notably, the “by the glass” selection is defined by Virtue’s prominent support of three black winemakers. The McBride Sisters—Robin and Andréa—grew up apart in the winemaking regions of Monterey, California and Marlborough, New Zealand but, upon reuniting went on to found “the largest Black-owned wine company in the United States.” Their sparkling Hawke’s Bay Brut Rosé ($16), 2020 Black Girl Magic Central Coast Riesling ($14), and 2019 Central Coast Chardonnay ($15) offer guests more premium options within some of the most popular vinous categories. The same can be said for Maison Noir’s 2019 “Horseshoes and Handgrenades” blend ($16) made from Oregon Syrah blended with Washington Cabernet Sauvignon and Merlot. This wine is the brainchild of André Hueston Mack, former head sommelier of Thomas Keller’s Per Se, who founded the “garage winery” in 2007.

Curating superlative “by the glass” offerings often demands throwing a restaurant’s weight around to secure the best pricing and most coveted allocations relative to the total volume of wine customers consume. Lacking the leverage or foresight to claim the bottles that everyone wants to drink, most programs are left to strike some compromise between quality and value. Virtue has navigated this well. However, more importantly, the restaurant has woven some element of winemaker identity—of supporting black craftsmanship in wine—into its selection. This serves to make the McBride Sisters and Maison Noir pours more personal, aligning them with Williams’s community goals and broader industry currents. But, other than the Black Girl Magic Riesling, you might not ever know that to be the case. Virtue simply features the wines—comprising several of the most popular varieties—as they would any others. Their quality (even if there is a larger context worth appreciating) is allowed to speak for itself.

While the restaurant’s bottle list notably features a 2019 Zinfandel ($126) from Brown Estate, “Napa Valley’s first Black-owned estate winery,” its overarching focus centers on classically-styled wines—including back vintages—at a competitive price.

When it comes to sparkling, that means non-vintage selections from Loimer ($78), Laurent-Perrier ($96), Charles Heidsieck ($118 or $222 en magnum), Ruinart ($192 for rosé, $218 for blanc de blancs), and Lanson ($242). The markups, even in this most desirable of categories, are kept within double the retail price—an exemplary standard that places Virtue among the city’s most competitively priced restaurants. There is even, for an unspecified “market price,” the option to enjoy “a little bubbly & some quality time” with the chef. Though you do not think Williams or Brown are shy about visiting their regular customers, this option offers traveling fans a polite gesture with which they may enjoy a moment with either of the men. Further, putting this item in writing helps to avoid the jealousies that naturally arise when a chef is seen only spending time at certain tables. This is a clever and generous touch.

Notable white wines include a 2019 Pinot Blanc/Pinot Gris blend from Au Bon Climat ($62), a 2020 Chablis from Joseph Drouhin ($82), a 2020 Chardonnay from Rombauer ($108), a 2019 Bernkasteler Badstube Spätlese from J. J. Prüm ($108), and a 2020 Sauvignon Blanc from Merry Edwards ($118). The bottles are split into categories like “Bright & Crisp,” “Fruit-Forward,” and “Rich & Full” that help guide consumers. However, it is that latter category that is home to the two finest wines of the bunch: a 2020 Peter Michael “Belle Cote” Chardonnay ($242) and a 2004 Bouchard Meursault 1er Cru “Les Genevrières” ($314).

Leading into the red wines, the list features a trio of rosés from Alexander Valley Vineyards ($52), E. Guigal ($74), and Caves d’Esclans ($96). The “Light” reds comprise recent release Pinot Noirs from Au Bon Climat ($68), Ken Wright ($78), Domaine Drouhin ($98), Belle Glos ($112), and Merry Edwards ($136) alongside a 2010 Gevrey-Chambertin 1er Cru “Les Cazetiers” from Maison Champy ($395). The “Medium” reds—apart from the aforementioned Brown Estate Zin—contains a 2017 Rioja from Bodegas Muga ($74), a 2019 Merlot from Hall ($92), a 2019 Châteauneuf-du-Pape from Roger Sabon ($105), and Ridge’s 2019 “Lytton Springs” blend ($115)

The ”Rich & Full” category features a 2019 Cantena Malbec ($62), a 2016 Haut-Médoc by Château Larose-Trintaudon ($72), a 2018 Cabernet from Hall ($138), a 2019 “Eddie’s Patch” Syrah by DuMOL ($232), and a 2013 Côte-Rôtie from Stéphane Ogier ($264). The final category—“Developed & Complex”—functions almost (apart from the Burgundies and Syrah) as a reserve list. It comprises a 2006 Brunello di Montalcino from Voliero ($228), the 2008 “Collezione Privata” Cabernet Sauvignon from Isole e Olena ($255), the 2009 ($262) and 2002 ($318) vintages from Silver Oak’s Alexander Valley holdings, a 2005 Napa Cabernet from Merus ($510), and a 1997 from Spottswoode ($780).

Overall, you must say that you have been quite impressed by Virtue’s bottle list. The selection is concise but representative and stacked with notable producers across a range of varieties and price points. For your taste, the J.J. Prüm Spätlese and Voliero Brunello have presented highly appealing options. The two Burgundies—from Bouchard and Champy—have also impressed you given the dearth of such bottles, especially with age, across the city’s wine lists. These and other “reserve” wines may go a bit beyond the flat, twice retail markup seen throughout the majority of the list; however, you think the pricing remains fair—given the bottles’ relative rarity—for guests looking to “throw down.”

Ultimately, Williams offers a list that encourages and rewards the appreciation of wine—which, in turn, honors the chef’s food. While Virtue has shown support to black vintners, the restaurant does so subtlety. The primary concern remains serving people what they want to drink, whether that encompasses oft-maligned brands like Rombauer, Belle Glos, and Silver Oak or respected, high-QPR producers like Au Bon Climat, Drouhin, and Ridge. You can trust that whatever you feel like spending will secure you a nice bottle, and wine service is conducted with care too.

That means proper stemware, decanting, ice buckets, and even pronunciation—for you, yourself, struggle a bit with words like cazetiers and genevrières. Virtue does not seem to have a sommelier per se, but each server is equipped to handle the majority of wines being sold. However, you have found that ordering some of finer bottles has placed you in the care of a more experienced team member that is engaged in her Court of Master Sommeliers studies. This server’s confidence in handling older corks, as well as the enthusiasm with which she approaches the more formal aspects of wine stewardship, has impressed you. In this manner, the restaurant is able to offer the expertise a floor sommelier might bring to the table without altering the tone of service (as some snobby, suited figure could very well do). Rather, Virtue affirms that wine can be adeptly handled and thoughtfully enjoyed in a setting that feels relaxed and comfortable.

This all amounts to a restaurant that celebrates fine wine and cuisine in a manner that is atypical for its genre. That, given Williams’s time at mk, must have been the goal—and his team have accomplished it with a distinctive style and sense of generosity that should be applauded.

Having decided on your desired beverages, you await your server. They arrive brimming with positive energy and offering their sincerest welcome. The server delivers a bit of a spiel—regarding Virtue’s style of cuisine, the sections of the menu, the 90-minute seating limit, and the necessity of placing the entirety of your order at once—and offers to take drink orders before giving your party a moment to decide upon dinner. But, conscious of the time limit and the size of the meal you intend to have, you say you can give them the totality right now.

That means, for a party of five, sharing one order of just about everything—along with double helpings of a select few dishes. The server receives this onslaught of an order with good cheer. They assure you that the kitchen will pace out the order and even offer a couple suggestions—like if you would prefer that your cornbread arrive alongside the gumbo. You are left with great anticipation for the forthcoming feast, but what happens next has varied.

On the occasion of your first visit, the kitchen aimed firmly at keeping you to the 90-minute time limit. This meant that your party was often overwhelmed—not in the sense that it was too much food to consume (for you always ensure your appetite matches the extent of the order), but that too much of it arrived at once to all fit on the table. Thus, you each had to balance plates in one hand while serving with the other and looking to consolidate or hand off those that had been emptied before you could possibly begin to eat. This process is not an entirely unfamiliar one—Roister being one restaurant that reliably always leaves you in this lurch—and you were able to manage it without any hard feelings. However, you still went 15 minutes over the allotted seating period and got the impression that the restaurant lacked the right communication or leadership to perfectly manage this kind of exceptional order.

Undeterred, you placed a similarly hefty order on the occasion of your second visit. This time, your server and the kitchen took control. The food arrived in flights that were far more manageable—and, thus, enjoyable—without the same scramble to offload the dishes’ contents and have the overflow of plates whisked away. The meal took about two hours, a significant breach of the 90-minute limit. But, surely, you never delayed in attacking the comestibles as they came, and the staff never made you feel rushed or unwelcome (as when offering dessert).

Unfortunately, the party that was made to wait for your table was standing right outside the windows adjacent to you. One of the guests, a middle-aged white woman, resolved to angrily glare at you between intermittent trips to the host stand. When it came time to leave, her party partially obstructed the entryway, and she pointedly remarked—to no one in particular—how incredibly rude your group of diners was.

Virtue, certainly, cannot be blamed for such silly behavior. Nonetheless, this encounter reveals the weakness of operating on such a strict timetable. For there must be some allowance made for parties that, in good faith, simply want to enjoy as much of the menu as possible. It must be recognized that hospitably satisfying such an order demands more than 90 minutes. And there must be enough flexibility in the bookings (or some kind of “release valve” via the bar room) to ensure some other party does not end up suffering. Because, you think, these time limits are meant to punish guests who drag their feet on paltry orders but not to stymie those who enthusiastically and respectfully wish to “throw down.” Thus, however useful such a framework proves for maximizing the total number of patrons served, certain allowances—in the interest of gastronomic appreciation—must be made.

Alas, your third visit to the restaurant proceeded swimmingly. Having placed an order, once more, of a similar size, your party ended up staying all of two and a half hours without the slightest disturbance. At this pace, both the wine service and each individual dish was given the greatest opportunity to shine. The atmosphere itself and the energy drawn from Virtue’s regulars, too, could really take hold. The evening demonstrated a dramatic improvement and growth in how the team managed the situation. It revealed a degree of engagement with singular tables and corresponding problem solving that testifies to great leadership. It spoke to a level of agency and ownership in responding to the kinds of exceptional cases that truly define the craft of hospitality at its best.

That’s a good thing because, overall, Virtue’s service is conducted admirably and should not be hobbled by a one-size-fits-all approach to meal timing. This kind of rigorous systemization, which you associate with establishments like Alinea, secures an overall sense of efficiency but saps dining experiences of any larger degree of personalization. It may take several visits for a diner to deduce just where the various boundaries and guardrails that inhibit the unfettered expression of hospitality lie. However, once a guest peeks behind the curtain and learns that their sense of immersion is calculated with certain hardcoded limits, they start to feel like nothing more than one of countless anonymous consumers. Interaction with the staff, from that point on, can seem uncanny or, rather, empty and transactional. Thus, the art of dining is robbed of its transcendent power because the customer has been denied the chance to enjoy the experience on their own terms—in their own singular way—before they have even taken their seat.

Virtue’s 90-minute time limit makes you feel like a tourist. It organizes your meal in accordance with what the most parsimonious, possibly obnoxious guests demand in order to get them out the door with a minimum of confrontation. The restaurant, during this shining peak of its popularity, deserves some means with which to defend itself. And Williams, certainly, serves his staff and the wider community by ensuring a certain number of covers flow through the doors each evening. But these systems—even if they effectively streamline the experience of the majority while aiding in the egress of those who refuse to yield their seats—are only positive insofar as they can be abandoned contextuality in service of some greater goal. That must always include catering to parties that, in good faith, want to indulge in the chef’s cuisine to the highest degree with plenty of wine and a generous gratuity to go along with it. This is not because such a table simply offers a greater financial incentive, but—rather—because they are engaging with more of the restaurant and constructing a sense of occasion that honors its craft while forging the social bonds that distinguish transcendent hospitality.

By changing course on your second visit and adapting to the needs of your party, Virtue has proven that it does not suffer tunnel vision on account of its time limit policy. The restaurant demonstrated that it does not fit each and every diner into the same mold, but bends the rules when it comes time to offer something superlative. In this manner, the team has not become cynical on account of its wild success and the steady stream of first-time customers that entails. It does not reserve “special treatment” only for a select few. In fact, the kitchen is motivated and equipped to rise to the occasion at a moment’s notice and put out a meal—over the course of a couple hours—that could rival any tasting menu in town. It does so without blinking—without letting on that the pesky 90-minute limit every existed in the first place.

Once you embark on that experience—confident that you can merely sit back, relax, and surrender fully to Williams and co.—the magic starts to flow. With no holds barred, the kitchen can orchestrate the perfect arrangement of the various dishes. They can juxtapose the “small,” “large,” and “extra” rations as the chefs and cooks themselves would enjoy them. And each flight of food arrives in tandem as if you were seated at the finest Southern banquet.

The front of house staff, in their expertise, knows just how to recede as this kind of feast takes shape. Water, wine glasses, utensils, and plates are attended to promptly. Your server checks in and expresses genuine delight when they hear how much everyone is enjoying the food. But the dishes are not larded with excessive descriptors or polemics (however fascinating some of the preparations really are). They arrive, and you are left to your own devices: to serve yourself and each other and join—through the act of breaking bread—the community Virtue has built within its four walls. You are permitted to join in the shared ritual of dining in your own way on your own terms, to share in the company of your guests with minimal interruption or inhibition. That allows some sense of your genuine self to shine through and connects with the spirit of the restaurant as embodied by the staff and the traditions it honors. Williams’s “black space,” in this manner, welcomes anyone willing to engage it in good faith and cares for them with total class.

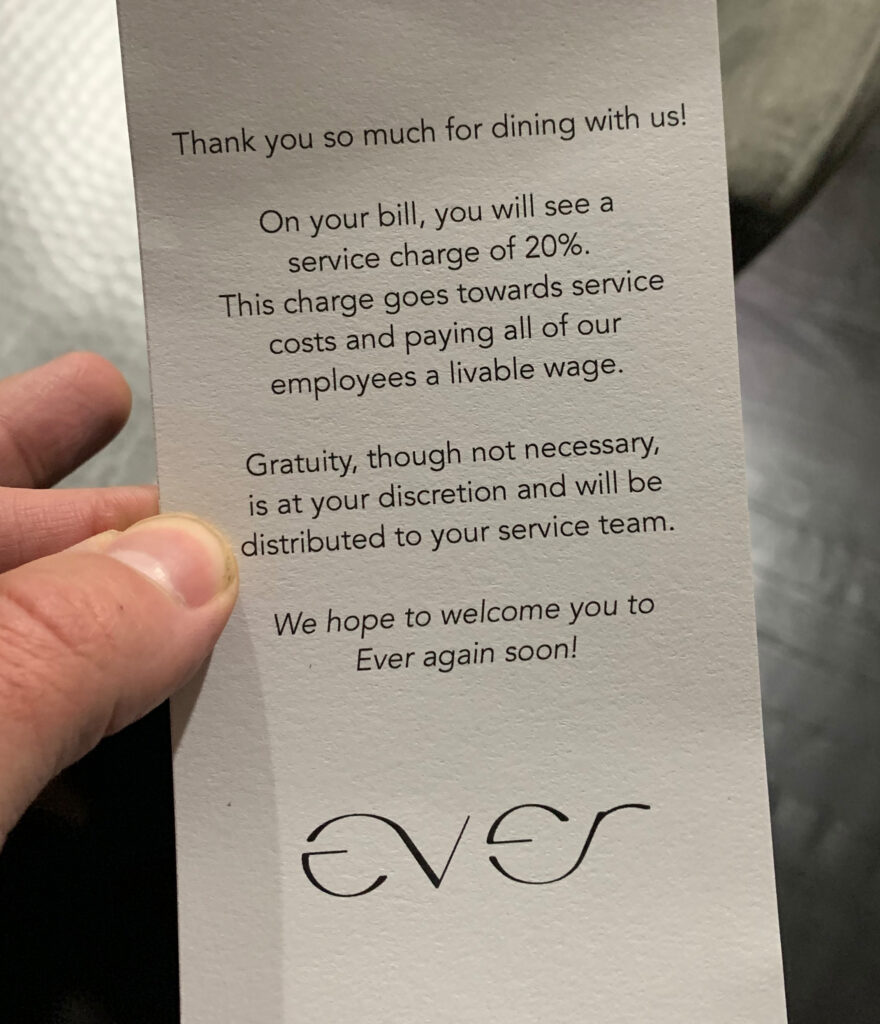

(That, fundamentally, may have something to do with the “3.5% surcharge” added to the final bill to cover the costs “of providing health insurance and benefits” to the team. Along with a “20% service fee” for parties of five or more, Virtue ensures its employees are supported to a degree that they can bring their best selves to the table each day. These policies serve to construct a community centered on an enlightened hospitality that protects and empowers its practitioners before sending them to embrace the wider public).

With your beverage and food order placed—with your party comfortably installed within the space—Williams and Brown take control and bring their vision of Southern cuisine to life.

There’s a reason, you think, that the chefs title their fare “rations”—a term associated with the “limited amount of something that one person is allowed to have,” especially “an amount given to soldiers when they are fighting.” On one hand, Virtue may provide its people with the kind of nourishment they need to fight and claim “black space” elsewhere. More deeply, the restaurant may offer all its diners a daily dose of something absolutely essential: love, care, dignity or respect. No matter the reading, the connection from mere sustenance to something more profound seems clear.

Though the exact sequence of dishes to flow out from the kitchen has changed slightly over the course of your three visits, you will look to preserve the ordering that you most preferred (and that offers the most appealing contrasts within and between courses).

The “Small Rations,” at least during the warmer months, have kicked off with a series of salads that—from the very beginning of the meal—testify to the degree of finesse and textural mastery Williams operates with.

Of these, the “Gem Lettuce” ($10) might seem the most familiar—having also been served since opening. The dish comprises a few hearts of the titular green that come coated with diced eggs, halved tomatoes, and radish slices in a ranch dressing. The distinguishing factor—or “crouton” if you will—comes by way of crispy black-eyed peas. They offer a crispy, earthy counterpoint to the more cleansing notes of lettuce, radish, and ranch. But you are most impressed by the way the size of each of the components is managed. The large segments of leaves crunch against the bursting tomatoes, the smaller black-eyed peas, and the even tinier bits of egg white and yolk. Like nesting dolls, each component contrasts the other and builds an immense heartiness as you chew your way through the salad. The preparation leaves you with a fresh, tangy finishing sensation that whets the appetite for what else is to come.

The ”Snap Pea” ($12), by comparison, is a bit more bold. It mingles its crisp pods with leaves of butter lettuce, slices of radish, and a topping of “crunchy grains.” The dressing, in this case, is not drawn from cooling ranch but, rather, features smoky, spicy harissa (a North African red chili paste). Thus, as you eat your way through the dish, the crunching snap peas meld into the softer lettuce but both are enlivened by a kiss of heat. The dish is carried, however, by the crunchy grains: a sweet, nutty, and earthy garnish of incredible pleasure and persistence that does well to balance the spicy depth of the harissa. There are enough of these crispy bits to coat each and every bite of the salad, amounting to yet another sense of heartiness that keeps you coming back for more until the bowl is empty.

“Cucumber” ($13), the last of these preparations, might be the most impressive of the bunch. In it, the titular vegetable is peeled and cut into rectangular chunks. It is joined by peeled cherry tomatoes and an assortment of mint leaves. But the crowning touch comes from a garnish of bacon bits and benne seeds—a relative of the sesame seed that was brought to the Carolinas by enslaved Africans. The seeds, which distinguish themselves “by magnifying umami nuances in foods,” also feature as a vinaigrette. The end result is a composition that takes the pristine—perhaps sometimes bland or watery—character of the cucumber and uses it as a canvas for powerful notes of pork, nut, and deep burnt honey. This makes for an attractive balance that unleashes the sweet notes of the tomatoes and brings in the cleansing tones of mint. Meanwhile, the soft crunch of the vegetable components—and their size relative to the crispy bits of bacon and benne seed—makes for another appealing textural interplay that you might call a hallmark of the restaurant’s salads. You cannot go wrong with any (or all) of the three!

After the salads, you have most enjoyed a course composed of Virtue’s “Gumbo” ($13) served alongside its “Biscuits” ($9). Frankly, ordering these dishes when you have any sense of the restaurant’s renown is enough to give you goosebumps. For these preparations must form points of pride for the kitchen, and it almost seems destined that your eyes will soon roll into the back of your head in an expression of total bliss. (Not to mention, there must be a reason that “the customer who sits at the bar three nights a week with his biscuits and glass of Zinfandel” keeps coming back).

The gumbo, in the traditional fashion, features the “holy trinity” of onion, bell pepper, and celery as the base of a broth containing chicken stock and tomato. While seafood sometimes plays a part in such recipes, Williams focuses his on the poultry, along with andouille sausage and Carolina Gold rice—“the grandfather of long-grain rice in the Americas.” The finishing touch comes by way of filé powder, which is made from ground leaves of sassafras and serves as both a thickening and flavoring agent.

Diving into the soup, you are struck first by its engrossing, layered aroma drawn from a blend of herbs and spices (like thyme and paprika). That sensation is mirrored by the taste of the broth, which perfectly balances its many inputs to impart a flavor that is deeply savory but invigorated by the mélange of complementary notes. This includes the spice, which matches the character of the smoky, tender chunks of sausage, as well as the herbs, which accent the pieces of chicken. The filé, as it dissolves into the broth, does indeed lend the gumbo a thicker mouthfeel along with undertones of earthiness. And the rice, with its clean, sweet flavor and hearty texture, serves to capture and enhance the totality of the dish’s ingredients. Virtue’s gumbo, it must be said, lives up to (and perhaps even surpasses) your high expectations. The kitchen is even so kind as to divide each order into two separate portions in order to facilitate sharing by larger parties—a gesture that should be applauded.

The kitchen also honors its guests when it comes to the biscuits, which typically arrive three to an order but whose serving size increases by one when necessary to save four-tops from having to pay for six. (Not that that would be such a bad thing). Relative to the crumbly, flaky variety of biscuit that has won popularity across certain—often fast food or fast casual—concepts, Virtue’s rendition is done more in the “drop biscuit” style. That means the baked good is more like a light and fluffy bread. It boasts a craggy, golden brown crust with deeper grooves that help the biscuit break apart into large chunks.