Elina’s

We now travel from the threshold of Chicago’s Gold Coast to a quiet stretch of Grand Avenue. Approaching Elina’s from the east, you pass the venerable D’Amato’s Bakery (and its next-door rival Bari Subs), a hair salon, a tattoo parlor, and some humble eateries slinging barbecue, sushi, and fried chicken serving the fringe between the southern boundary of Noble Square and northern boundary of West Loop. Approaching Elina’s from the west, you see two of your favorite artisans (Tempesta Market and Aya Pastry), a couple of pizzerias (Coalfire and Salerno’s), a classic biker bar (Twisted Spoke), and yet another sandwich shop—Vinnies.

While Adalina, proximally, appendaged itself to those Rush Street peers, Elina seems to hide in plain sight. It stands apart from all the action on Fulton, Lake, and Randolph while—at the same time—resisting inclusion among Chicago Avenue’s range of new and eclectic dining options. Despite that, the restaurant is perpetually booked a full month in advance (unless you like eating after 9:30 PM). Elina’s has drawn diners towards an area known more for pastries, grab and go lunches, and late-night drinks than trendy restaurants. Its owners have transformed a former taqueria (The Gringo), tavern (Grandview), and wine bar (Cafe Fresco) space into the kind of Italian joint that can rival a litany of neighborhood options like Bella Notte, Provaré, Mart Anthony’s, Piccolo Sogno, La Scarola, Macello, and Gioia. And yet, nothing about Elina’s seems out of place.

You see, Adalina and Alla Vita are characterized by their investment. Anchored by larger restaurant groups, they boast streetwise design and advanced world-building. They are large operations lumbering into a crowded genre with the hopes of disgorging some large part of the pasta-eating public into their own dining rooms. They announce themselves on their respective blocks—the potential flow of walk-ins forming the most compelling reason to occupy such premium real estate in the first place. Why try to be the best Italian restaurant in Chicago when you only need to be the biggest and most competent on your block? Why reinvent the noodle when you only need to boil and sauce it and serve it up hot to the unwashed masses?

With only twenty-eight seats to speak of—along with another ten first-come, first-served spots at its bar—Elina’s has quietly chosen to pursue perfection. Chef-owners Ian Rusnak and Eric Safin, whose sterling credentials you noted at the beginning of the article, would seem to have no other choice. They opened their restaurant without the least bit of fanfare in mid-September. There was no professional media blitz, no spoon-feeding of tantalizing copy to Chicago’s usual hacks. Even the business’s Instagram account promises little more than “Fine Italian American Cooking.”

Elina’s was not going to catch any of the thunder Adalina and Alla Vita had drummed up. Its interior would never form a fitting stage for the kind of “food influencer” for whom the quality of a meal correlates principally to its trappings. The restaurant’s menu—at least at face value—would not appeal to garden variety “foodies” for whom gimmicky descriptors and eye-catching presentations form the lifeblood of their content. Rusnak and Safin were just two guys slinging red sauce fare behind a subdued façade that could be dated to the 1970s like its submarine shop confrères on the block. They never screamed nor shouted about serving the best Italian food in the city, but humbly plied their trade and welcomed customers who—for whatever reason—made the trek.

It only took one glance at the chefs’ combined experience—Jean-Georges, Carbone, ZZ’s, Marc Forgione, Blackbird, Bavette’s The Grill, 4 Charles—to pique your interest. That any other details were scant secured it. You visited Elina’s during its opening weekend and thrice more after that. Quite suddenly, the quiet restaurant grew into a buzzing hive. They no longer sat you by the window to attract walk-ins but, rather, pleaded with would-be guests that there really was no more room.

Elina’s topped Resy’s “October Hit List” and featured in an October 7 article by Eater Chicago. Only a week or two after that, the restaurant’s reservation book filled up to the current brim it maintains. (Tuesday-Saturday, if you want to eat at a decent hour, you had better set your alarm for midnight one month prior). Which is to say, Rusnak and Safin have achieved “trendy”—if not blazing hot—status with little more than old-fashioned word of mouth. Meanwhile, they’ve retained every bit of the charm that colored your very first experience.

Elina’s success flies in the face of the media gatekeeping, prefabricated public relations drivel through which hospitality’s major players conspire with undiscerning content creators to mislead the public. Promising nothing more than “fine Italian cooking served by two chefs in an intimate space,” Rusnak and Safin have sidestepped the promotional paradigm that so often debases their craft. What they have gained by doing so is immeasurable: the chance at culinary expression free from puffery and the pressure of expectations.

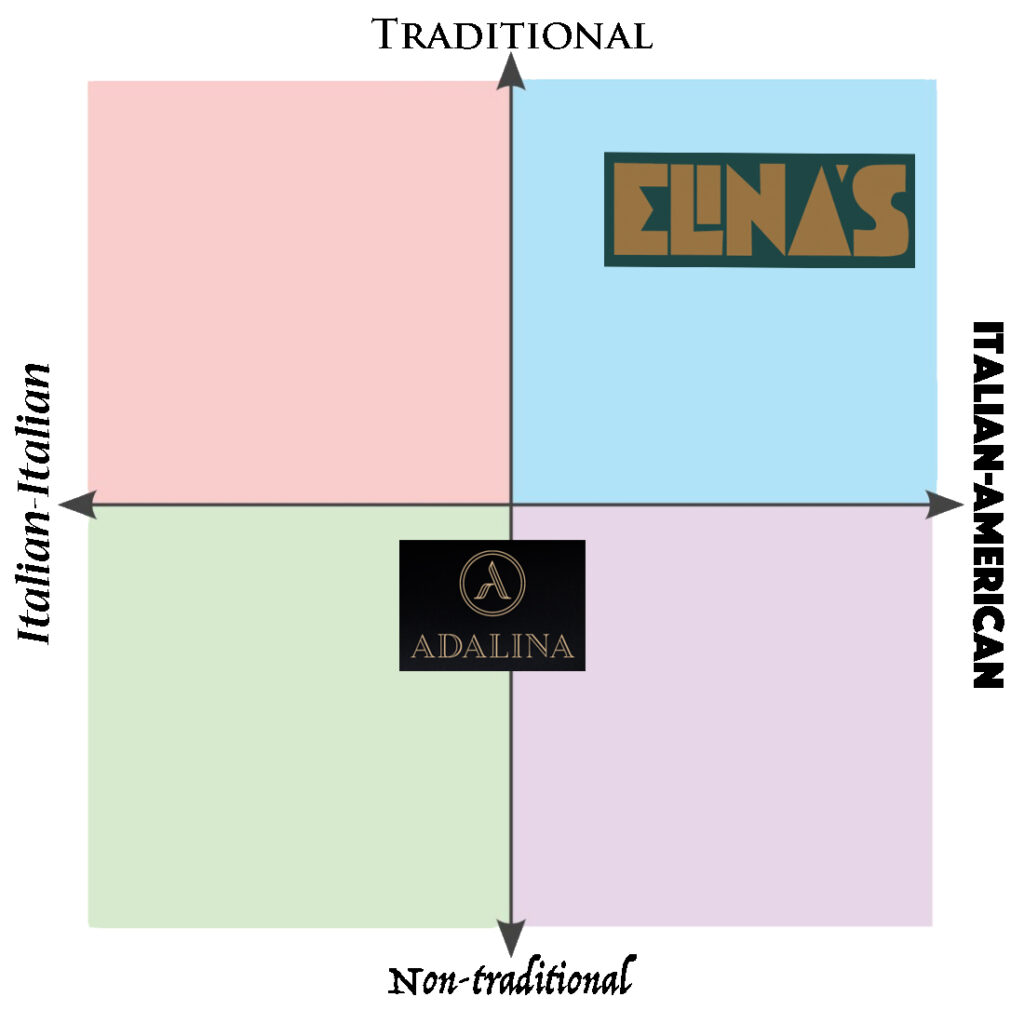

The two have built a beautifully understated temple to Italian-American cooking that affirms Chicagoan taste. Elina’s, like Carbone, might very well mark the first of the city’s next-generation “red sauce joints.” It might usher in the revival of that beloved hyphenated cuisine that diners took for granted but tastemakers judged beneath them. It might plant a shining flag in that upper right corner of your chart that asserts the Windy City can transcend notions of “authenticity” in order to revel in the glory of nostalgia. For Elina’s speaks to the Italian “tradition” that shall not be named. It is a shining example of the quality that lies beyond the “Italian-Italian” canon.

But, of course, you get ahead of yourself. As usual, you will combine the totality of your four experiences into one cohesive and encompassing narrative. Let us begin.

No matter from which direction you approach it, Elina’s demands a double take. The Gringo—as the space used to be called—had made its presence known (perhaps too well known). Its bright white façade distinguished itself from the blocks of red brick buildings on Grand. Multicolored signage advertised “margaritas,” “churros,” “queso,” “cerveza,” “chicos,” and “chicas” to all who walked by. But The Gringo’s owners would be accused of defrauding one of their investors—an Army veteran—in March of this year. The restaurant, as far as you can tell, had actually closed in December of 2020, but not before having its liquor license revoked (a reality that affects Elina’s to this day).

Nonetheless, Rusnak and Safin’s restaurant—which takes its name from that of the latter’s mother—has given 1202 W. Grand Ave. a new lease on life. The Gringo’s obnoxious storefront has been erased by a dark coat of paint and two decals with faded bronze lettering. That font—which renders the name “Elina’s” with a mixture of triangles, rectangles, and misshapen curves—speaks to something essential. The design, affixed to the restaurant’s front door and the center of the façade’s windows, is deceptively simple. The block letters could belong to almost any business from the 1970s. They could speak to the same history as D’Amato’s or Bari. But closer inspection suggests a studied carelessness, an undercurrent of intention that will only ever so slyly announce itself.

Some nights, when driving down Grand, you strain your eyes trying to catch a glimpse inside of Elina’s. You know where the place is by now, but it has taken practice. Unlike so many of its neighbors, the restaurant boasts no neon sign. Its decals are illegible by night. So you’ve trained yourself to spot the crowded row of tables—illuminated only by the glow of candles and sconces—that spans the length of the dining room.

On foot, locating the restaurant is only a bit easier. Yes, you can stop and read the signage—and perhaps survey the menu posted to the side of the door—but that assumes you haven’t already hightailed it halfway to Ogden. It is best to remember that Elina’s sits just about on the northwest corner of Grand and Racine. One door down, the white tablecloths and well-dressed patrons will confirm your arrival. The restaurant does not announce itself but begs to be discovered.

You pull open the door, pass through the vestibule, and hug the sideboard that sits along the wall closest to you. The hostess mans a tablet at the corner of the L-shaped bar before you. Its surface stretches back towards the kitchen, making room for those ten coveted seats for walk-ins. She greets you, takes your name, and guides your party to a table posthaste.

That could mean one of two freestanding four-tops placed front and center on the floor only a few steps away. (Of the pair, the table closer to the window is favored for being better insulated from foot traffic. Of course, you also open yourself up to the greedy eyes of passersby as they watch you slurp your spaghetti). Past those four-tops, against the wall, spans the tufted blue-green banquette that frames the majority of Elina’s seating. The individual two-tops can be pushed together to seat as many as six guests, but, often, groups of two and four make up the twelve spots. These are the tables—row after row of red sauce set ablaze by the glow of candlelight—that catch your eye from across the street.

Beyond the furthest banquette, past the entryway to the restaurant’s bathroom, sit two booths made from the same tufted leather. They offer the restaurant’s most intimate, comfortable seating for groups up to four—their cushions rising high enough to obscure the rest of the dining room. At the same time, Elina’s bar seating runs perpendicular to the booths’ openings, allowing a bit of people-watching and, on one occasion, the chance to share a few glasses of wine with some other, particularly convivial guests.

Beyond the aforementioned white tablecloths, sconces, candles, and tufted leather, Rusnak and Safin’s restaurant is rather light on design elements. Gray tiles with a compass rose pattern—a holdover from The Gringo—coat the dining room’s floor. Yet they do not seem out of place, especially when you cast your eyes upwards towards the antique molding and inlaid ancient map that adorn the ceiling. (Surely, these characterful elements are original to the building, but Elina’s did well to paint the molding to match the darker tones with which they infused the space).

The wall closest to the entrance is made of exposed brick in a faded, off-white tone that, likewise, speaks to the space’s history. The lighter color helps frame the white tiled cabinetry behind the bar. That interesting piece—another holdover from The Gringo—contains six compartments that might eventually be used, once more, to hold bottles. However, at present, they display candelabras, vinyl records, stereo equipment, and canned tomatoes. The bar itself is made of dark-colored wood with a lighter, lacquered (and rather slippery) top. It is illuminated by five hanging lanterns that shine down upon even more candelabras along with a couple colorful floral arrangements placed in imposing vases. At the end of the bar, back towards the entrance, rests a cake stand with a tantalizing stack of cannoli. A tall, dark oil painting featuring a bare-chested woman hangs next to the sideboard, which itself displays more candles, another vase, some small ceramics, and an antique mirror.

Having worked for Hogsalt, Rusnak surely knows a thing or two about how Sodikoff’s group combines layer after layer of antique bric-a-brac to build a sense of timelessness and romance. That décor, when combined with the right lighting, furniture, and finishes convinces diners they have actually stepped into some cozy neighborhood place from yesteryear. And that feeling, when it comes off so well, sets the table perfectly for the enjoyment of unabashedly classic fare executed with finesse.

Now, Elina’s is no Ciccio Mio—which is to say, a movie set—but the restaurant channels some of the same feeling. The materials—brick, tile, and wood—are worn but clean, reflecting a lack of fuss or needless refurbishment for the sake of curb appeal. The blue-green, gray, dark brown, and black tones combine to form a palette that is sleek but still subdued. At the same time, the tufted leather, white tablecloths, glowing glass sconces, and small candles emblematize the proprietors’ care for guest comfort and the desire to channel a sense of refinement. The dining room’s wooden chairs land somewhere in between. While they do not provide the ultimate in comfort, they are stable (and you’d be lying if you said they didn’t remind you of the rickety seats at your childhood red sauce joint).

The bar, being accented by that surprising burst of white tile, resists a dark and seedy feel that might detract from the worship of Elina’s food. (As with Monteverde and Rose Mary, the sight of diners perched on stools shoveling pasta into their mouths serves as one of the very best signals that some serious cooking is going on). Meanwhile, the two booths—should you be lucky enough to be seated there—truly feel like sanctuaries. The dining room is intimate, but you do not feel smashed against any of the other patrons. Rather, the bustle of a full house cements the sense that you are somewhere. It makes that creaking chair feel worth its weight in gold.

Ultimately, Elina’s few meager flourishes—the painting, many candelabras, floral arrangements, canned tomatoes, and stacked cannoli—simply humanize the space. Scattered about with that same careless elegance you sense in the restaurant’s font, they reflect a restaurant fueled by some person’s passion, some kind of vision that understands intuitively how to set the experience’s tone. Such fragmented design elements are easy to underestimate, but the whole effect lends the space that desired intimacy.

Elina’s feels familiar and knowable but, at the same time, one of a kind. It possesses a personality that cannot be formulated or designed by committee but must express itself, naturally, as Rusnak and Safin grow the business from its humble beginnings. That genuine, bootstrapped quality is what conjures a feeling of comfort and, even, luxury. For what feels more special than a tiny neighborhood place that only you know about?

After being seated, you turn your attention towards beverages. Now, as previously mentioned, the revocation of The Gringo’s liquor license has left Elina’s in the lurch. The restaurant possesses ample glassware, along with essentials like sparkling water, but leaves it to guests to handle the booze. That’s not a bad thing. For as much as you await Rusnak and Safin’s eventual wine list, the prospect of refined Italian fare with a BYOB policy is rather exciting.

Ciccio Mio (as did Spiaggia back in the day) allows corkage for $50 per bottle with a limit of two bottles per party. Adalina’s corkage costs $45, and RPM Italian’s fee clocks in at $40 (both with the same maximum of two bottles). Meanwhile, Gibsons Italia charges only $35 per bottle ($50 per magnum) with no bottle limit. Formento’s goes even lower—charging only $25—but maintains the same maximum allowance as the others. It is unclear where Alla Vita falls in this hierarchy, but you would guess they charge $35 (with a two bottle limit) in the same vein as Swift & Sons’ and GT Prime’s policies.

For an oenophile, even a $50 sticker fee is well worth it to enjoy a bottle that one has selected and cellared to suit their taste. As an example, you could pay $796 for Ciccio Mio’s 2007 Conterno “Cascina Francia” off the list or spend $349 (plus $36.17 sales tax and $50 corkage) to bring the 2004 or 2001 vintage of the same wine purchased locally from Flickinger. That adds up to just a little more than half the price!

Now, you certainly frown upon so consciously undercutting a restaurant’s pricing when a more or less similar expression sits in its cellar. (You recall once bringing a bottle of 2000 Tua Rita “Redigaffi” to Spiaggia. Despite other aged examples of the wine being represented on the restaurant’s massive list, beverage director Rachael Lowe shared her excitement regarding the exemplary vintage you had on hand. A more cynical wine professional might have rued you cheating them out of a four-figure sum). However, with knowledge of fine Italian wine still out of the mainstream, a generous corkage policy (to say nothing of full-on BYOB) can really enrich the appreciation of both “Italian-Italian” and Italian-American food.

Those $300-$400 bottles of 1990s Oddero Barolo from Adalina’s wine list really are a rare exception. For diners must typically pay closer to $600-$700 for any aged bottle of Nebbiolo, Sangiovese, or Amarone from a mid-tier producer. The same amount could also get you a current release wine from a top-tier producer that, generally, would not be worth opening at such a young age. The same price logic generally holds true for American cult Cabernets—another favorite choice within this genre of dining—but many coveted domestic wines, while they certainly benefit from aging, are generous enough to be enjoyed early on.

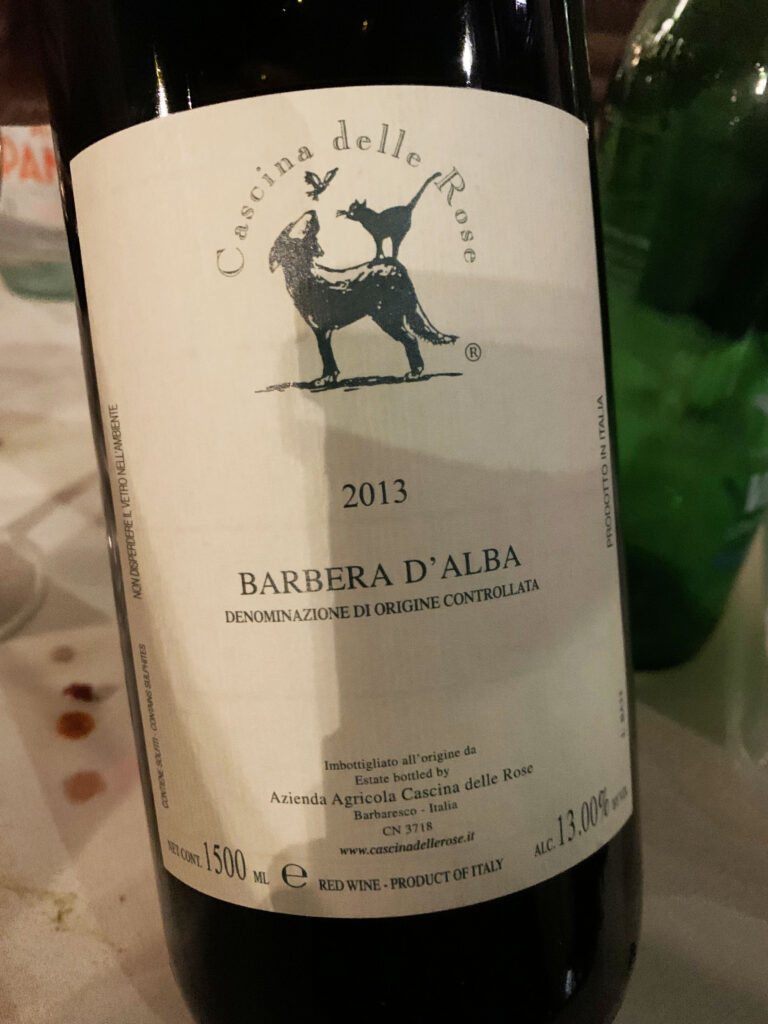

Thus, you would say that Italian reds form something of a pitfall. Their tannic, coiled nature forbids accessibility to anybody unwilling to spend a pretty penny. In the $100-$200 range, restaurants are left stocking early-drinking off vintages and low-tier producers whose perceived quality can only be deduced by how much you trust the sommelier’s taste. At the $50-$100 range, one can find value and pleasure from grapes like Dolcetto, Freisa, and Barbera. One can also find more affordable, drinkable examples of Nebbiolo (labelled Langhe Rosso) and Sangiovese (Rosso di Montalcino). But these latter examples demand that one look beyond more recognizable appellations like Barbaresco, Barolo, Chianti, and Brunello.

Italian reds generally demand a conversation with the sommelier if one looks to avoid something brooding and nasty. Italian white wines are not much different: one chooses from overpriced examples of familiar, international varietals like Chardonnay and Sauvignon Blanc or takes a leap on some unknown grape like Friulano, Ribolla Gialla, Roero Arneis, Soave, Trebbiano, or Vermentino. There are plenty of excellent bottles to be had, but there is also quite an increased risk of receiving something jarring to one’s palate even when throwing one or two hundred dollars down.

With this in mind, Elina’s BYOB policy—at least a present—allows diners the rare opportunity to drink exactly what they like or—better yet—to splurge on the kind of bottle that would cost an exorbitant amount on a list. Given that the menu is principally Italian-American (more on that later) and, thus, highly nostalgic, the simplest advice you can give is to drink what you enjoy. It will sure as hell beat the wicker basket Chianti that sat on the table when you were a kid. And you’ve seen plenty of guests come in with beer or, better yet, even a bottle of bourbon.

For those looking to make the most of their evening—especially given how hard a reservation Elina’s has become—you’ll make some more specific recommendations. Italian-American cuisine, despite being refined by Rusnak and Safin on their menu, remains full-flavored. Lighter fare like salads, fritto misto, baked clams, scampi, branzino, and dover sole feature savory accompanying elements that demand white wines from neutral grapes (like Chardonnay or Riesling) that feature either cleansing acidity (as a contrasting note) or moderate oak and ripeness (as a complement). Delicate, nuanced whites run the risk of being overshadowed. Likewise, you do not see much room for “greener” varietals like Sauvignon Blanc or Grüner Veltliner. However, the phenolic bitterness shown by Italian grapes in general—along with skin-contact “orange wines” and clean styles of “natural” wine—will also stand up well to the food.

When it comes to red wine, the same rules apply. Dishes like vodka rigatoni, eggplant parm, chicken parm, meatballs, and steak are not well-suited to soft-spoken bottles. While Elina’s hand-cut ribeye can withstand your favorite, tannic “steakhouse” wine, plates featuring tomato sauce will sing when paired with ripe red fruit and acidity. That includes varietals like Pinot Noir, Nebbiolo, and Sangiovese along with Cabernet Sauvignon and Zinfandel of more moderate body and oak usage. Your Chardonnay, Riesling, native Italian varietals, and “orange wines” can also carry over to the rigatoni, eggplant, and chicken too—as can a drier style of rosé.

Apart from the ribeye, Elina’s cooking avoids the heaviness diners associate with Italian-American cuisine. Thus, when choosing what to bring, the key is select vibrant, open wines that will not overwhelm the food with jarring oak, tannin, or alcohol. The lack of corkage makes the restaurant an attractive option for those who enjoy well-aged Barbaresco, Barolo, and Brunello, but you would avoid going out and purchasing too young of an expression. That money could be spent on a top-tier Langhe Nebbiolo or Rosso di Montalcino that will better guarantee immediate pleasure. Likewise, you can just as easily put the money towards an exceptional, easy-drinking domestic wine or even Champagne. The hedonistic appeal of the food should be matched by a wine of equal pleasure. That’s the spirit of this sort of dining, and, ultimately, there’s no need to complicate matters.

You remove your bottles of wine from their tote and set them on the table. Normally, your server would offer to open them, but he notes the Durand you have brought along and declares that he will be right back with some glassware. When it comes to decanters, you have never made the request. But, judging by the vessels sitting in one of the cubbies hanging over the bar, you are sure the restaurant could find one if necessary.

With the drinks settled, it now comes time to order. At Elina’s, the hostess doubles as a captain, and the lone server works as a jack of all trades. The kitchen—as well as the chef-proprietors themselves—pitch in plenty too. It’s a shoestring team—befitting such a small space—but it operates with virtuosity and soul.

From the get-go the hostess’s greeting is warm and relaxed. When she comes to take the order, there’s no kind of rehearsed, concocted spiel. Rather, it’s a conversation—or, in your case, a challenge to transcribe the full breadth of the desired dishes, their quantity, and their staging throughout the course of the meal. For example, you might request that a seafood pasta be timed to arrive with fish dishes, lighter meat and vegetable pastas to be paired with eggplant, and a pasta with vodka sauce brought out with meatballs and chicken parm. The hostess-cum-captain handles such orchestrating with aplomb, double-checking her transcription with a sincere sense of ownership over your party’s experience. (Midway through such a meal, she earnestly asked if she had done a good job following your fanatical instructions. It was a touching gesture, for the dinner had proceeded perfectly).

The lone server-cum-busser, first and foremost, certainly looks the part. The crucifix hanging from his neck is no prop, but the kind of bonafide adornment that makes you feel right at home in such a restaurant. Of course, he was kind enough to recognize and warmly greet you on the occasion of your third visit. But such a personal touch takes nothing away from his technical skill. With all the hustle demanded of a lone body working the floor, you have found this server to be fleet-footed and highly aware. Empty plates and water glasses do not linger for long, and they are handled with finesse despite the cramped spaces separating some of the tables. Turnover in these front of house positions might, unfortunately, be close to inevitable. Yet this positive attitude, energy, and excellence can only exist when supported from the very top.

Fittingly, the back of house does a commendable jobs when they step away from their pots of boiling water and bubbling tomato sauce. The chef-proprietors strike you as being deeply engaged in their work, but not so much that they cannot pause to offer a warm greeting and marvel at your gluttonous indulgence in their food. Their appreciation for guests’ patronage rings true, and it is never beneath them—as the best chefs (Iliana Regan always come to mind) always embody—to bus a table on their way back to the kitchen.

As an enterprise, Elina’s is too small to afford lackluster service. Nonetheless, the restaurant achieves more than mechanical competence. The staff operates with coolness and confidence despite its perpetually-filled seats. They smack of elbow grease and passion in a manner that reminds you of family-run red sauce joints of yesteryear. That is to say, they fulfill the image of the intimate eatery to which Rusnak and Safin aspire, infusing the space with the sense of care that forms a perfect pairing for fare of such nostalgia.

When it comes to Elina’s cuisine—and the prospect of orienting the restaurant relative to its “Italian-Italian” and Italian-American peers—you find the fare rather easy to place. Rusnak and Safin both worked for Major Food Group, whose partners Mario Carbone and Rich Torrisi have built their name upon refined, nostalgic Italian-American (ZZ’s Clam Bar, Carbone, Santina) and more broadly American (Sadelle’s, The Grill) concepts. M.F.G. has also grafted that same sensibility onto the French bistro (Dirty French) and “Japanese brasserie” (The Lobster Club) genres, defining a style that is both luxurious and crowd-pleasing for the fashionable sect willing to pay the premium to dine at their restaurants.

You have enjoyed your visits to Carbone and The Grill—their wine lists alone signify just how seriously the group approaches hospitality. But the group’s collaborations with famous architects, fashion designers, and visual artists on the many details that define their spaces signify an attention that goes beyond food and drink. Major’s partners repackage timeless recipes and deliver them via graceful service in environments that capture guests’ imaginations. Their restaurants appeal not only to “foodies” (in fact, one could argue they fall short of ever pushing boundaries), but a wide range of diners for whom dressing up, going out, and feeling a sense of place defines the evening’s quality more than a minute focus on flavor.

Beyond the chefs’ shared experience with M.F.G., Rusnak’s time as Hogsalt’s culinary director—even if he worked principally on 4 Charles Prime Rib and Bavette’s—surely made him familiar with Ciccio Mio. Brendan Sodikoff’s group might lack the glitz and glamour that surround establishments like Carbone or The Grill, but the success of 4 Charles in a Manhattan market perpetually opposed to interlopers stands as a triumph. Likewise, Bavette’s continued success within Chicago’s crowded steakhouse genre also demands respect. Though lacking famous collaborators, Hogsalt’s spaces conjure a similar sense of place while maintaining high standards of cooking and service for a large volume of customers.

Now, Elina’s décor does not quite reach the heights of Carbone or even Ciccio Mio, yet—as mentioned—captures the same tone in a homespun, personal way. The restaurant’s service—as you have just covered—excels due to the nature of its all-hands-on-deck intimacy. So, despite the rigorous corporate hospitality culture and training processes M.F.G. and Hogsalt have developed to iterate a sense of warmth, Rusnak and Safin’s upstart achieves much of the same charm on account of its small size.

Now, it would be tempting to label Elina’s cuisine as derivative of Carbone and/or Ciccio Mio. All three restaurants, surely, draw on the same Italian-American canon, and all three share the symbology of—and a reverence for—that classic theme. Carbone opened in 2013, and you think it’s safe to assume that M.F.G.’s success with the concept (which now includes additional locations in Hong Kong, Las Vegas, and Miami) inspired Sodikoff to open Ciccio Mio in 2019. The red sauce joint replaced the floundering Radio Anago while capturing a slice of the next-generation Italian-American genre that only Formento’s (opened in 2015) had then touched on. Chicago, no doubt, seemed due for the kind of nostalgic reimagining that had marked Carbone as one of New York City’s toughest reservations. But Ciccio Mio, as much as you enjoyed it, filtered Carbone’s vision through a Hogsalt filter that restrained the menu from going far enough.

You see, the key to Carbone’s reinvention of the red sauce genre lays in providing those pitch-perfect luxury conceits. The restaurant’s setting looks convincingly like the 1950s—and the bill of fare reads that way too—but the food that arrives stakes its claim as superlative, contemporary comfort food by any measure. Carbone’s baked clams, for example, are rendered as a trio of “Oreganata” (breadcrumbs, oregano, garlic), “Casino” (bacon, peppers), and “Fantasia” (uni, green onion) dressed bivalves that blend classic flavors with novel decadence. The “piccata” preparation (lemon, caper, butter) one associates with chicken is ported over to dover sole while the veal parmesan is larger but somehow thinner and crispier than any example one has seen before. Carbone and Torrisi preserve the archetypal essence of these recipes while writing their new chapter for modern palates.

Hogsalt, by your measure, has exceled—instead—by its restraint. Yes, Bavette’s “Maude’s Tower” might be the most expensive seafood tower in the city, but it has long been the only example that causes the desired wonder and awe when it reaches the table. The rest of the menu—particularly the fried chicken and steaks—have distinguished themselves for quiet excellence without fanfare or premium pricing. Compared to the pricy cuts of Japanese and American wagyu touted by Maple & Ash, RPM Steak, and Gibsons Italia, Bavette’s fleet of USDA Prime beef has always struck you as better-tasting, better-textured, and more consistently prepared. What the menu lacks in creativity, customers gain in reliability and value. For Hogsalt properties are not actively chef-driven, but reflect a common grammar that establishes (and suits) guest expectations across a variety of genres.

Thus, while Ciccio Mio struck you as unique upon its opening, the restaurant’s menu now stands—relative to Adalina and Elina’s—as somewhat more institutional. The biggest flourishes are seen when ingredients like black truffle are thrown onto mozzarella sticks or bucatini, but other old favorites are rendered in a familiar, approachable way. Ciccio Mio’s menu really has a lot in common with Alla Vita’s (more on that later), which is to say that both ventures form a foothold for a large hospitality group to get in on the red sauce act without committing to a particular chef’s distinct creative vision.

You originally placed Ciccio Mio at the upper right-hand corner of your grid (highly Italian-American, highly traditional) and stand by that orientation. By comparison, you will place Elina’s just as far to the right but a bit lower on the “traditional” scale. That is to say, Rusnak and Safin’s restaurant is distinctly Italian-American, generally representative of its tradition, but makes greater room for that tradition to be transcended. The upstart might not yet do so with the same depth as Carbone’s menu, but the intention is there. Certainly, the chef-proprietors have already struck upon at least one novel preparation recipe that speaks to the pair’s ability to reconfigure the beloved cuisine.

Once you place your order, the show begins. Guests expecting one of Elina’s salads to arrive first will be pleasantly surprised when an aproned figure arrives at the table with a basket of goodies. Unlike Adalina’s bit of parmigiano, bread, and tomato—which arrive immediately upon your being seated—Rusnak and Safin take a page from the Carbone and Ciccio Mio playbooks. They offer garlic bread, pizza bread, thinly-sliced salami, and eggplant caponata to their customers in an attractive spread. Rather than merely providing a nibble, the assortment of bites invites the table to begin using their hands, to become engrossed in a style of dining epitomized by “family-style” sharing.

Presentation aside, the items, technically, are rather nice too. The garlic bread is crisp, crunchy, and amply flavored. The pizza bread is molten, saucy, and nearly good enough to be sold by the pan in fulfilment of its namesake form. The salami possesses a gossamer quality that melts on the tongue—it will do a good job pleasing palates that struggle to appreciate chewier, chunkier cured meats. Likewise, the caponata is more of a pickle dish than a fine paste. The rounds of eggplant within the dish display a hearty crunch with a pleasing sweet and sour flavor accented by sweet pepper and basil. It does a brilliant job stoking your stomach for the forthcoming feast and will even make a believer out of diners who tend to dislike the nightshade.

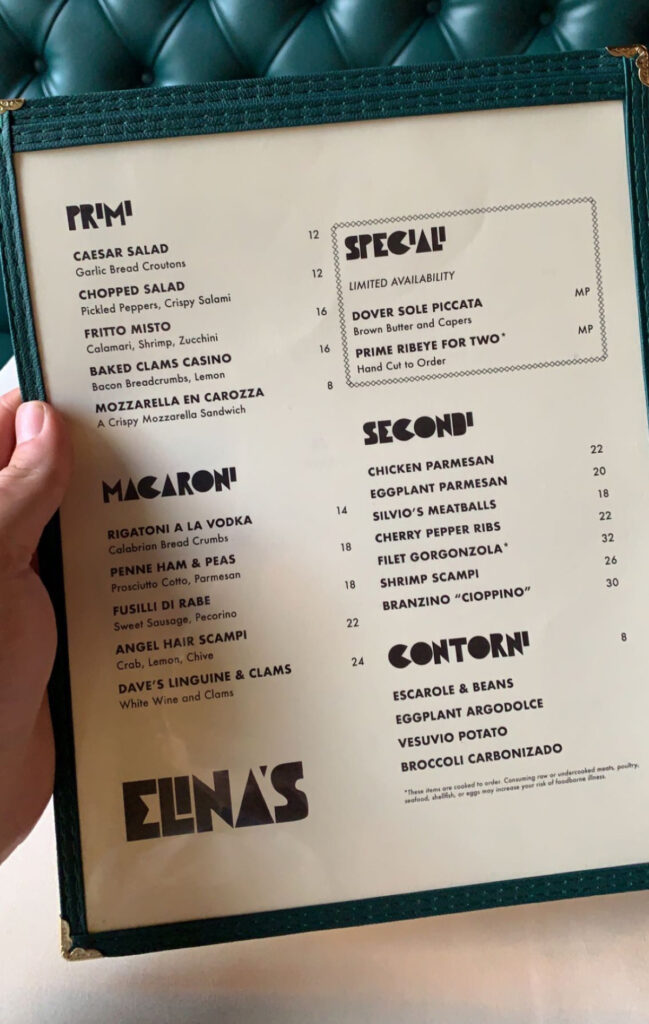

Turning to the menu proper, Elina’s “Primi” section begins with a couple salads (each priced at $14). There’s the ever-present Caesar, paired with “garlic bread croutons,” and a chopped salad that features chickpeas, tomatoes, pickled peppers, and crispy salami in a classic vinaigrette.

Though Carbone, certainly, has made its name by offering a tableside Caesar, Rusnak and Safin have smartly resisted imbuing their version with any needless flourishes. (You have already noted how Adalina quietly axed such a presentation, leaving behind a fairly ordinary example of the form). Elina’s rendition features well-dressed, not soggy, and—ultimately—refreshingly tangy lettuce dusted with enough grated parmigiano to provide a pleasing, savory undercurrent of flavor. The croutons are, as advertised, made from that same garlic bread toted out to the table. It is cubed and toasted a bit more—but not so much that it entirely loses its absorptive property. This Caesar might lack any compelling “twist,” but it shines as a precise execution of the classic recipe and, thus, a guarantor of pleasure for a wide audience.

By contrast, the restaurant’s chopped salad allows the chefs to demonstrate greater textural mastery. While Ciccio Mio’s version combines salami, shaved parmesan, and olives—and Alla Vita’s opts for a blend of salami, pepperoncini, red onion, and tomato—Elina’s weaves together ingredients of greater intricacy. The pickled peppers—relative to pepperoncini—offer a softer chew and sweeter, tangy (but not hot) finish. The crisped salami—while not quite the finocchiona used elsewhere—offers a beautifully crunchy contrast from the well-dressed lettuce. The tomatoes offer a familiar, gushing quality, but it is the chickpeas that really sing. Their buttery texture and mild flavor serve to ground the salad’s more aggressive notes. Crunching through the assemblage of sweet, sour, and salty elements is highly engaging, and the chopped salad stands as a good example of the finesse Rusnak and Safin bring to the genre.

Elina’s “Fritto Misto,” priced at $18, is four dollars cheaper than a similar portion served at Alla Vita. While the latter restaurant pairs its shrimp and calamari with a lemon and Calabrian chili aioli, the former offers theirs with a small serving of a standard lemon aioli alongside a whole boat of marinara. Elina’s version, to complete the illusion of time travel, is garnished with a few sprigs of Italian parsley. But, looks aside, it is no slouch.

The shrimp and calamari are lightly breaded, fried, and display a craggy, crisp crust. However, the coating does not interfere with your appreciation of the seafood’s mouthfeel. The shrimp retains that all-essential succulence which—should it be overcooked—defeats the entire purpose of including it in such a preparation. The squid, likewise, maintains a pleasing chew that marries beautifully with the batter. Personally, you are more partial to cocktail sauce as a pairing for calamari. Yet the marinara imparts ample acidity (along with a big dose of nostalgia). The accompanying squeeze of lemon and side of aioli, too, should suit those who are more averse to dunking their seafood in red sauce.

Elina’s “Baked Clams Casino” harkens back to the luxurious selection of bivalves served at Carbone. There, the “Oreganata” preparation done as part of the New York restaurant’s trio references a more humble, classic Italian-American dish. The combination of butter, breadcrumbs, garlic, oregano, and parsley—often combined in a frying pan with minced clam meat then returned to its empty shell to be baked—simply goes by the name of “Baked Clams” on many menus. The recipe used by The Rosebud on Taylor Street, which makes use of additional ingredients like sweet onion, crab meat, lemon pepper, and paprika, will always stand—in your mind—as the quintessence of the form. It’s a dish, sadly, that has become scarce in Chicago, even among Italian-American revivals. For sopping your bread in the buttery runoff at the bottom of a plate of baked clams will always stand as one of life’s deepest pleasures.

Clams Casino—relative to the oreganata preparation—can be more precisely dated to late 19th century Rhode Island. The recipe, which features common elements like breadcrumbs, garlic, lemon, onion, and/or parsley, is distinguished principally by the presence of bacon. Along with Oysters Rockefeller, it stands as a throwback to an era of luxury dining characterized by baked shellfish dishes. Clams Casino is a bonafide part of the American canon that intersects rather nicely with the oreganata tradition.

For their “Baked Clams Casino,” Rusnak and Safin choose medium-sized cherrystones. $16 gets you nine of them, which arrive boasting a golden brown crust of breadcrumbs. The bacon, garlic, and parsley are blended seamlessly into the finely-ground mixture. Bound with butter and crisped, the ingredients are almost unrecognizable. However, their incorporation in this manner amounts to a homogeneity of texture that ensures each bivalve delivers a consistent bite.

Nonetheless, you have found it hard to slurp the clam cleanly from its shell, which necessitates the use of a fork to dislodge the muscle and release the combination of meat and coating into your mouth. You also run the risk, until one realizes the bivalve won’t budge, of sucking off the breadcrumb mixture and leaving the clam naked. Tasted by itself in those unfortunate circumstances, the mixture of bacon, garlic, and butter is surprisingly unremarkable. It forms a pleasing a textural element but does not strike the palate with any porky power. You’d have loved to apply Tabasco, in the traditional manner, to help rectify this dullness and dryness, but Elina’s does not offer any. You adore baked clams, and you admire the fact that the restaurant offers—and looks to update—the dish. The bivalves, for what it’s worth, are of good quality. But the kitchen needs to devise a cleaner, easily comestible bite with ample moisture and bacon flavor to really do the recipe justice.

The last item in the “Primi” category, nevertheless, is one of the restaurant’s biggest winners. The “Mozzarella en Carrozza”—“mozzarella in a carriage”—is described on the menu as “a crispy mozzarella sandwich.” The dish takes after a popular street food from Campania that later found popularity in New York City’s Italian-American restaurants. The cheese sandwich is traditionally coated in egg and flour and then pan-fried, achieving a crispy exterior while retaining some of the interior softness of your standard sliced loaf. Elina’s version does not only deep fry the recipe—as is often done stateside—but takes the added step of coating the bread’s outer portion in breadcrumbs.

Served with aioli and marinara sauce to dip, the preparation amounts to the most perfect version of a mozzarella stick ever conceived. See, compared to coating the cheese directly in breadcrumbs, the added layer of fried bread forms a rigid barrier onto which the gooey mass can spread itself. This provides a cleaner eating experience while also ensuring the mozzarella enters a molten state free from any lingering sense of chew. Guests can enjoy the usual “money shot” of dribbling melted cheese while engineering each bite with the perfect amount of sauce. The outer coating of breadcrumbs, meanwhile, provides a fine, crisp texture that plays off of the sandwich’s coarser interior crumb. At $12, the mozzarella sandwich will surely establish itself as a “must-order” item with powerful, crowd-pleasing capability.

Elina’s “Macaroni” section contains the full breadth of the restaurant’s pasta offerings. It’s a curious bit of terminology (also used at Carbone) given the word’s particular association with the all-American mac and cheese. But Italians, too, include a wide range of short and long noodles under the term maccheroni. And even the FDA includes spaghetti and vermicelli under the category of “macaroni product.” So Elina’s use of the term is not in error; rather, it speaks to a bit of whimsy and a charming innocence through which a whole panoply of pasta shapes gets placed under that familiar label (whose double meaning, in reference to exotic sophistication, dates as far back as “Yankee Doodle”).

The section kicks off with that old favorite, rigatoni alla vodka—transcribed on the menu as “rigatoni a la vodka.” (Within the Italian-American genre, errors of this sort simply add to a restaurant’s credibility. For any notion of “authenticity” went out the window a long time ago, and only flavor matters). Elina’s rigatoni, in fact, is more like the lumache you described at Adalina. Here, as there, it offers a more captivating mouthfeel as the two bent ends of the short, tubular shape bounce off of each other with each chew. The pasta is cooked to a perfect al dente and sauced with admirable restraint. (Looking at the pictures, you’ll note no puddle at the bottom of the bowl). This allows the topping of breadcrumbs—laced with Calabrian chile oil—to retain their full crispness.

But the star of such a preparation must undoubtedly be the vodka sauce. Though possessing the telltale orange tone, Elina’s rendition avoids the goopy consistency that can sink some preparations. Their sauce is lightly creamy, slightly tangy, and pleasantly sweet. Despite the light touch shown in dressing the rigatoni, each bite of pasta displays ample flavor. The slight chew of the noodles yields to the crunchy contrast of the breadcrumbs, whereupon that tinge of Calabrian chile imparts a trace of spice that shines against the dairy. Rusnak and Safin have crafted a streamlined rigatoni alla vodka that still stokes the fire of diners’ nostalgia for the form. It will, deservedly, remain as one of the foundations of the menu.

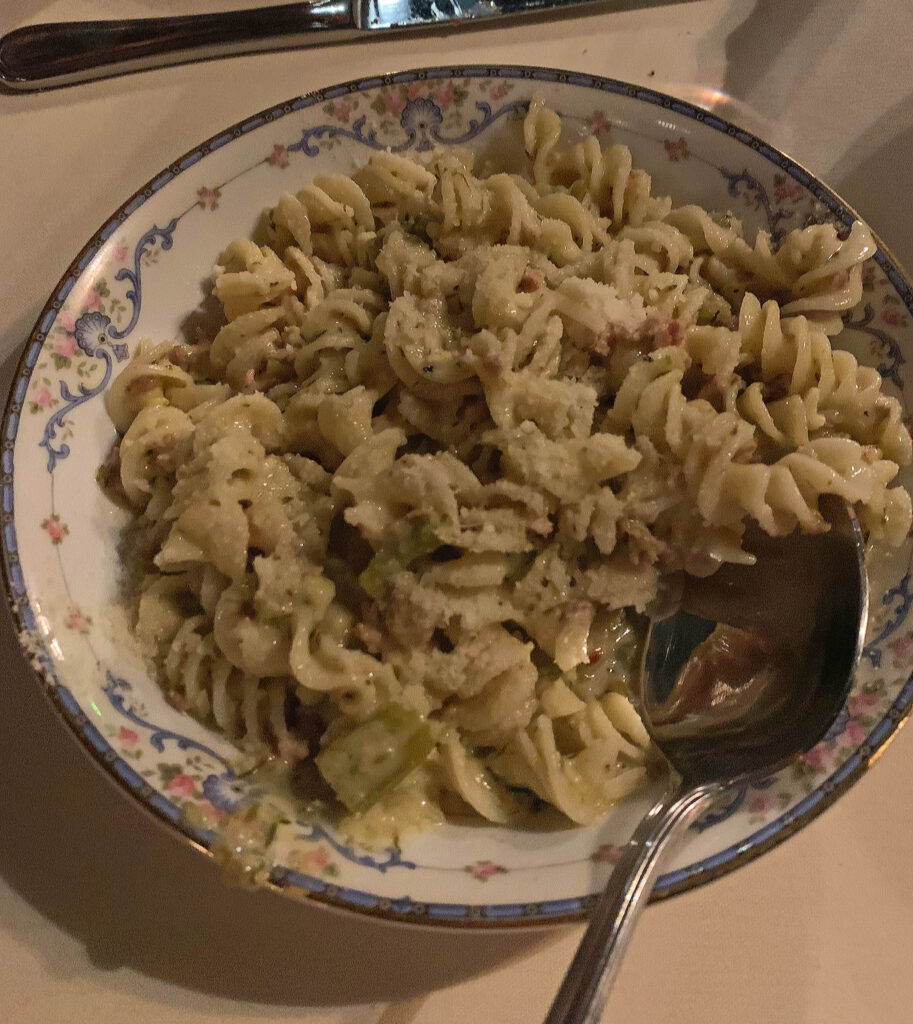

Elina’s fusilli di rabe features those namesake “spindled” noodles shaped like corkscrews. “Rabe,” of course, refers to broccoli rabe—also known as rapini—a member of the brassica family known for its nutty, bitter character. The pasta is lightly dressed with olive oil, paired with chunks of sweet sausage, and blanketed by grated parmigiano (that replaced the tangier Pecorino that originally featured in the recipe). Looking at the dish, you’d hardly know the broccoli rabe was there! But, upon closer inspection, streaks of green can be seen interlaced among the spirals.

By processing the rapini in such a way, the restaurant avoids the crunchy bits of stem and wilted leaves that make the vegetable—when served as a side with roasted meat—so texturally appealing. However, in doing so, the chefs ensure the chew of the fusilli and sweet morsels of sausage can really shine. Given this dish is unmistakably the meatiest of Elina’s pasta preparations, it makes sense to indulge fully in that element. The broccoli rabe does nothing to distract from those essential elements of oil, pasta, pork, and cheese. Instead, it simply offers a subtle bitter quality and sharpness that enhances the star attraction. (That, perhaps, allowed the restaurant to do away with the original, more forceful Pecorino flavor in favor of parm). Those who love rapini will appreciate its traditional presence alongside the sausage. At the same time, Rusnak and Safin have found a balance that ensures the uninitiated can still enjoy the principle flavors. This sense of restraint, also seen with the rigatoni, modernizes the canonical combination without forsaking its essence.

Elina’s “Angel Hair Scampi” makes use of Italy’s thinnest noodle—capelli d’angelo that feature a diameter of 0.78-0.88 mm (relative to 0.85-0.92 mm for standard capellini). The term “scampi” literally refers to a species of lobster from the Mediterranean and northeastern Atlantic but has come to denote a variety of crustacean preparations typically made with garlic, butter, white wine, and lemon. In the case of this particular pasta, the term signifies lump crab that has been dressed with lemon and tossed with chives and parsley in a simple sauce of olive oil and butter.

Just as the fusilli represented Rusnak and Safin’s meatiest “Macaroni” offering, the angel hair stands as the simplest of their noodle dishes. (You say that, in part, due to the relative complexity of the rigatoni’s vodka sauce even though it only, otherwise, contains breadcrumbs). The “Scampi” preparation, rightfully, revolves around the presence of the crab—it $22, it’s three to four dollars more expensive than any of the other pastas. But the chefs wield the crustacean with aplomb. The thinness of the noodles ensures that the lump meat, though certainly no glistening hunk of king crab, feels generous. Likewise, the angel hair’s dressing of lemon, oil, and butter is ample enough to avoid blandness but measured enough to accentuate the crustacean’s sweetness. The garnish of chives and parsley, though usually an afterthought, actually offers a surprising textural contrast given the small scale of the other ingredients. Their dual herbaceous quality lifts the dish while preserving the purity of the “scampi” flavor profile. Given that other examples can devolve into an oily mess, the preparation stands as another impressive showcase of the chefs’ restraint.

Elina’s once featured a pasta titled “Dave’s Linguine & Clams” as part of the “Macaroni” section that has since been discontinued. Relative to the angel hair, the “little tongue” noodles possessed a bit more chew that nicely matched that of the bivalves. The dish was sauced similarly to the “Scampi” but added a touch of white wine and subtracted the chives in favor of parsley alone. The preparation did a better job of showcasing the clams’ pristine meat than the “Baked Clams Casino” do in their present state, and you found the textural interplay to be sound. However, the item really was quite similar to the “Angel Hair Scampi,” and you can sympathize with the small team’s decision to do four pastas superbly rather than offer a fifth derivative that, for little gain, could threaten to derail the more distinct offerings. Once the baked clams get up to snuff, it will be easier to look past the absence of Dave’s recipe.

The last of the pastas was originally titled “Penne Ham & Peas” but is now simply called “Penne & Prosciutto.” Both dishes have featured the same ingredients—sweet peas, prosciutto cotto, and parmigiano—but the change in name adds a bit more subtlety to the nostalgic combination being invoked. The penne itself are ridged (rigate) and rather large, but you don’t think they quite qualify as pennoni. Rather, the noodles’ width and curvature seem less like “quills” and more like bent rigatoni (actual rigatoni, that is, and not lumache). Whatever you call it, the pasta shape is distinct from Elina’s other preparations and suits the dish well.

For the circumference of the penne matches that of the peas perfectly, and the chunks of prosciutto cotto—rendered in convincing ham-like cubes—match too. The buttery noodles are blanketed by plenty of grated parm, providing an added textural dimension along with that tried-and-true nutty-sweet flavor. Working through the bowl, you chew on the penne, burst the peas on your tongue, and savor the chunks of ham interspersed with granules of cheese. The buttery sauce yields to sweetness which yields to salty, meaty goodness in a wonderful interplay. The complexity of the parmigiano—sharing a common note with each of the other components—keeps everything in balance. “Ham and peas” is not a particularly nostalgic dish for you personally, but Rusnak and Safin have created a pasta that stands on its own merits while, surely, touching upon some guests’ childhood memories at the same time. The chefs’ pastas, across the board, are deceptively simple and impressively executed. Bravo!

Elina’s “Secondi” section is something of a mixed bag, spanning both entrées and items that strike you more like medium-sized shared plates. Imitating the actual flow of your meals, you will weave a path from seafood to meat and lighter to heavier fare. Along the way, you’ll insert each of the two “limited availability” dishes that occupy a separate “Speciali” category. In this manner, the reader can better imagine how they might structure their own dinner.

To begin, you return to scampi: “Shrimp Scampi,” rather than the crab and angel hair variety from the “Macaroni” category. Now, having typically eaten your fill of shrimp as part of the “Fritto Misto,” you have only deigned to order this dish once. $27 gets you a plate of seven medium-sized shrimp glistening in a coating of butter, olive oil, and chopped parsley. A segment of lemon and a couple slices of that good old garlic bread complete the presentation. You cannot disagree that it sounds (and looks) a bit scant. Surely, anybody ordering this as their main course will be left scratching their head. But, appearances aside, there is little fault to be found with Elina’s “Shrimp Scampi.”

The shellfish is clean, plump, and accented by notes of garlic and white wine. Though only seven pieces, the portion satisfies by way of the ingredient’s quality. The shrimp that impressed you with their succulence from behind the “Fritto Misto’s” crispy batter and marinara sauce are here given the spotlight. For being so shockingly simple—so jarringly unadorned—the dish punches above its weight. Still, you cannot quite see what part it plays on the restaurant’s menu. Customers with a particular hankering for this item are best advised to pair it with an order of the angel hair or one of the two other seafood dishes you will describe next. The scampi shines when ordered as a pleasant couple of shared bites, not the anchor of an entire course.

By comparison, Elina’s “Branzino ‘Cioppino’” stands as one of the most pleasant surprises of the entire menu. You ignored the dish during your first couple visits, opting for an alternate fish preparation from the “Speciali” category, but it has since become a must-order item. At $32, the branzino is tied with the filet mignon as the most expensive of the restaurant’s standard offerings, but that’s excluding those two “limited availability” options labelled at “MP” or “market price.” Arriving in an attractive handled skillet, the sea bass boasts a lattice-charred skin and swims in a pool of red sauce with rings of squid and a couple odd shrimp.

The label “Cioppino,” of course, refers to the famous San Franciscan Italian-American fish stew typically made with tomatoes, seafood stock, white wine, garlic, some parsley, and a dash of anise-flavored liqueur. Classic recipes traditionally made use of the day’s catch, so the exact assortment of fish and shellfish could vary. Rusnak and Safin, understandably, use the seafood they already have on hand. However, relative to throwing some chunks of fillet into a hodgepodge of a stew, their dish rightfully reads more as a branzino dish. The sea bass is moist, flaky, and benefits from the contrasting crispness of its charred skin. The shrimp are juicy, and the calamari are pleasantly chewy as before. But it’s that cioppino-inspired sauce that makes everything sing.

Compared to the branzino preparations at Adalina (served with eggplant mostarda) and Ciccio Mio (served with salsa verde), Elina’s use of a tomato-based sauce strikes you as more comforting. There’s still plenty of acid at hand to prevent the dish from seeming heavy. However, the depth of flavor drawn from the seafood stock along with the sweetness of the anise and tomatoes really enhances the sea bass’s more mild flavor. While many fish dishes, for you, run the risk of tasting too bland, the cioppino form allows for a legible infusion of powerful harmonizing notes. The dish, though something of an innovation, strikes closer to the full-flavored Italian-American tradition than the simply grilled varieties you often encounter. At the same time, it marks a particularly luxurious example of the kind of fish stews also found in Italy itself. The chefs deserve credit for conceiving of something that is both elegant and delicious. You only wish they offered some additional bread to dip into the skillet!

The last of Elina’s seafood options, “Dover Sole Piccata,” appears within that “Speciali” category at a market price that you cannot quite remember ($50-$60 would be your guess). “Piccata,” as a preparation, is classically applied to veal in Italy and to chicken in America. However, the recipe has also been adapted to swordfish in Italy as well as a variety of other fish like flounder, cod, grouper, or branzino in America. In its simplest form, piccata denotes meat that has been pounded flat, dredged in flour, browned, and then finished with a pan sauce made with the addition of lemon juice, wine, capers, parsley, and butter. When the technique is applied to dover sole, that most noble of fish, it’s hard not to see the resemblance to sole meunière. And that, perhaps, is the best way to think of this offering.

Arriving at the table split cleanly into two whole fillets, the sole is lightly browned and perfectly deboned. The fish displays the fine flakes and meatiness for which it is prized, and the chefs should be commended for cooking it perfectly. The piccata preparation really only departs from a sole meunière in terms of the level of saucing. While the French tradition shows a lighter touch, Elina’s version is more amply coated in the combination of butter, chives, parsley, and some translucent onions. Relative to the sole’s latent flavor, you do not find the dressing overpowering. It places the dish in line with the intensity seen elsewhere on the menu—a full-flavored preparation in accordance with the Italian-American genre. You think the “Dover Sole Piccata” is an appealing option for parties looking to split a larger portion of fish, but it does not distinguish itself enough to be remarkable like the “Branzino ‘Cioppino.’”

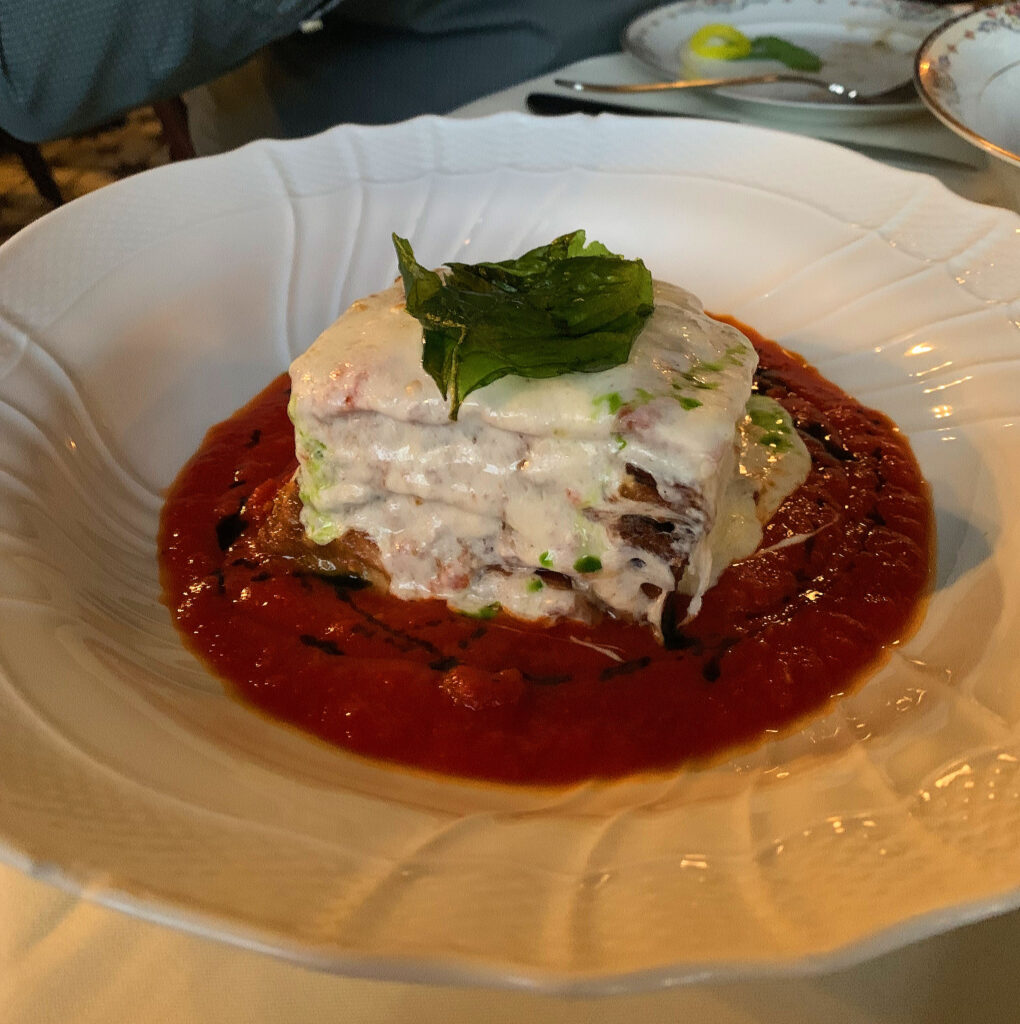

Elina’s “Eggplant Parmesan” is undoubtedly one of the marvels of the menu. It stands, as far as you have searched, as the best rendition of the recipe seen in Chicago. The dish arrives at the table looking like a cheese-frosted layer cake, and the key to the preparation, no doubt, comes from salting the nightshade overnight. The eggplant is first fried and then, slice by slice, stacked six or seven levels high. The layers are interlaced with marinara, mozzarella, and the titular grated parmigiano. The whole thing is topped with more sauce, more cheese, and baked to oozing completion. Diners receive a neat cube of eggplant cut from the pan and topped with a couple leaves of crispy basil. It all sits in a bowl with more marinara and a tinge of herb oil that serve to moisten the parm’s interior portions.

Slicing into the skyscraper of nightshade, you are struck by just how smooth its texture is. There is no trace of stringiness as each one of the layers separates cleanly from the parm’s central structure and allows you to take a full, multifaceted bite. Eggplant, sauce, and cheese strike the palate five, six, seven times in turn without any trace of bitterness. Rather, there’s a sweetness and richness to the nightshade that reminds you why this preparation persists at all. The eggplant is not a sad substitute for lasagne, chicken, or veal, but the genitor of the parmesan style and the base that ultimately yields the best texture and depth of flavor. The ingredient need only be treated with care, and that is what Rusnak and Safin have done. No dish better captures the chefs’ capability to take a simple recipe and do it very, very well.

Elina’s “Chicken Parmesan” is not that far off in quality from its nightshade cousin. Like so many of the restaurant’s dishes, it excels by nature of its restraint. For, in Adalina’s case, their use of a quality bone-in veal chop ensured that any loss of crispness due to the attractive layer of cheese was balanced by the sheer deliciousness of the meat. Rusnak and Safin, instead, have opted to use the humble chicken as their canvas, and, smartly, they avoid coating it too heavily with mozzarella.

Thus, what the pounded poultry breast lacks in flavor can be made up for with its crispness. The Italian breadcrumbs used—in the traditional manner—possess a finer grain than the flakier panko. Their moderate crunch frames a thin layer of juicy chicken and what amounts to a glaze of tomato sauce, parmigiano, and melted mozzarella. There’s no pool of sauce at the bottom of the plate, no goopy overflow of cheese. You particularly like how the edges of cutlet are black and a bit more brittle. They speak to the crust that the chefs have tried so hard to maintain. Rusnak and Safin do so successfully and, by privileging that texture, have created one of Chicago’s most successful examples of the Italian-American canon’s standard-bearer.

“Silvio’s Meatballs,” at $18 for a set of three, are fairly satisfying. Personally, you like to pair them with your vodka rigatoni (rather than situate them alongside other “Secondi” offerings). Though you are not certain, your guess is that Elina’s uses a mixture of beef, pork, and veal for their blend. The balls possess a smooth interior and rich, rounded flavor that would preclude the use of beef alone. They arrive touting a light coating of red sauce, a sprinkle of grated parm (that melts nicely onto their surface), and a solitary crisped basil leaf at the nexus of the three pieces.

Departing from other dishes, the bottom of the bowl holds a bit of extra sauce and a drizzle of olive oil to help dress the interior of the meat. It’s a thoughtful decision, and one that is still done moderately enough to avoid submerging the balls to such an extent that they lose their unique sense of chew and savor. Given that Elina’s pastas only feature smaller chunks of sweet sausage or prosciutto cotto, the meatballs must deliver an accompanying sense of sustenance. That, they certainly deliver (though without ever striking you as particularly remarkable). But making a remarkable meatball is a tall order, and this rendition certainly keeps pace with the other good examples seen throughout the city. However, being priced a bit higher than Adalina ($16) and Ciccio Mio ($15.95), you are not sure you can taste why.

Elina’s “Cherry Pepper Ribs,” by comparison, are an undeniable hit. The recipe features on Carbone’s menu, but it’s not one you can say that you’ve often (or ever) seen within Chicago’s own Italian-American canon. (Rosebud, just as one example, opts instead for baby back ribs made in the American barbecue style). Cherry peppers, certainly, are a familiar ingredient within the genre, garnishing plates at Adalina, Ciccio Mio, and RPM Italian. Likewise, spare ribs are braised, grilled, and roasted throughout both the “Italian-Italian” and Italian-American traditions. Combining these two ingredients makes sense when trying to riff on the domestic barbecue tradition while grappling with the relative dearth of hot and spicy seasonings within the canon.

Rusnak and Safin, following in Carbone’s footsteps, glaze their spare ribs with a sauce made from the pickled cherry peppers and roast them in the oven. The racks are then separated into single bones that are tossed with a bit more of the sauce and stacked crisscross on a plate. Some leaves of mint and thin slices of the pickled peppers complete the presentation, which comprises a total of six ribs for $27. That might sound like slim pickings, but this isn’t your ordinary half rack. Though the spare ribs possess some small bones and cartilage towards the tip, they are longer and meatier than their baby back brethren. Elina’s serving can easily satisfy two or three diners, though you will admit once splitting three portions (of which one was solely yours) as a party of five.

As much as you love ribs, you have become wary of restaurants that roast their own without any particular expertise with (or dedication to) the form. Such an item is almost guaranteed to please when prepared well, yet great pit masters make their name more on the basis of consistency than inventiveness. Nonetheless, Elina’s has been unerring in the tenderness of their spare ribs, delivering bone after bone with a pleasing bite that immediately yields to tender meat. The pork’s saucing—all things considered—is actually rather light. The cherry pepper glaze delivers a finish that The New York Times Magazine [referring to Carbone] once called “shiny and piquant, with just a hint of fire.” Rusnak and Safin’s version seems even a little more subtle. There’s just enough sweet-and-sour pickled pepper flavor to moderate the carnal intensity with only a tinge of heat to keep things interesting. The “Cherry Pepper Ribs,” in that respect, are a broadly accessible dish with only a vague connection to tradition. However, they are highly delicious and, like so many canonical recipes, emphasize how an “American” form (like barbecue) might be fitted to include Italian ingredients.

The last and largest item on the restaurant’s menu, another “market price” offering listed under “Speciali,” is the “Prime Ribeye for Two.” As with the dover sole, you cannot quite remember the exact tariff charged for the dish on the couple occasions you have tried it. But your best guess would be somewhere in the range of $130-$140 for a steak weighing in at 36-40 ounces. Some variance is due to the fact that the ribeye is “Hand Cut to Order,” as advertised on the menu. This means the chefs are left with some level of discretion as they portion each cut to a particular number of guests. But, whatever way they slice it, you have been struck by the generosity of the portion. “For Two,” really means for two of the kind of diners who regularly patronize Italian-American restaurants. The label is not an attempt to cash in on some imagined shared splendor; rather, this is a real hunk of meat more than capable of standing up to the very heaviest of red wines.

More importantly, Rusnak and Safin prepare it perfectly. This ribeye not only measures up to the excellent steaks served at Monteverde and Rose Mary (two of the top, if sleeper, preparations within Chicago) but can go toe to toe with RPM, Gibsons, and even Bavette’s. It makes sense given Rusnak’s experience with Hogsalt, but Elina’s really knocks this preparation out of the park. The “Bistecca alla Fiorentina” at Adalina, while beautifully presented and accompanied by mushrooms and potatoes, does not hold a candle to this ribeye. In fact, Elina’s steak arrives looking like nothing more than a massive plate of beef, but it strikes squarely at the carnivore’s deepest desire.

The “Prime Ribeye for Two” is aggressively charred then finished in the oven. It is rested, sliced into segments close to two inches thick, and plated along with the ribs. The beef is garnished with a sprinkle of flaky salt and a drizzle of its juices—that’s it. As is often recommended for ribeyes, the steak is cooked until medium. That means the slices closest to the middle display a pink center while those at the ends feature a bit more brown in their color gradient. Thus, customers who prefer medium rare would do best to explicitly request it, but you have been impressed by the degree to which the steak’s pockets of fat burst in your mouth. There has never been any trace of unrendered sinew throughout the meat, meaning that every inch of meat served—including every morsel you can gnaw off the bones—may actually be enjoyed.

Given its size, the ribeye can easily satisfy parties of three or four that have indulged amply in other parts of the restaurant’s menu. Paired with the “Cherry Pepper Ribs,” you can particularly note that item’s sweet-and-sour character. The steak, meanwhile, is straightforwardly beefy. It’s a rough and tough “closer” that is sure to send patrons hobbling towards the door, belt straining to contain the influx of food. The “Prime Ribeye for Two” ensures that customers willing to pay a premium for a fine cut of meat will be left with no question of their satisfaction. In that respect, it strikes at the soul of the Italian-American genre (one often synonymous with the concept of the “Italian Steakhouse”).

Elina’s “Contorni” (or side dishes) are certainly recommended. They comprise “Escarole & Beans,” “Vesuvio Potato,” “Broccoli Carbonizado,” and “Eggplant Agrodolce.” Of these, the broccoli and the eggplant are the most interesting. The former’s florets possess a healthy layer of char that make it a perfect partner for the well-seared steak. Likewise, the tinge of sweetness to the latter’s puffed eggplant pieces forms a fitting complement to the ribs. Though you sometimes avoid these side items in order to allow for a greater amount of pasta and entrée dishes to hit the table, they will deliver an intricate array of supporting flavors to diners who might only wish to sample a few of the larger compositions.

When it comes to dessert, the choice is easy: take the cannoli. To end the meal, Elina’s only offers their rendition of that totemic Italian (and, perhaps, even more distinctly Italian-American) pastry. Though the restaurant has sold out of them once before, you have otherwise never had any trouble securing at least one cannolo for each member of your party. That’s a good thing, for Rusnak and Safin have done the recipe proud.

Their cannoli possess a thinner, less craggy shell than you are used to. It is dusted in powdered sugar and filled with an overflow of ricotta cream. Finally, a rather generous coating of crushed pistachios crowns each end. While some cannoli wrappers are too bulky or altogether spongey, Elina’s thinner shell breaks apart cleanly. Thus, it reliably delivers a clean, composed bite in which each of the three elements are balanced. The crisp exterior, supercharged by the additional coating of sugar, frames the smooth, tangy center and crumbly accent of nuts. It offers the quintessence of cannoli without any of the mess. It’s a satisfying few bites that, after such an onslaught of excellent savory fare, manages to be just enough.

Obviously, this lone classic offering cannot compete with Guini’s superlative lineup of desserts at Adalina. But these cannoli strikes the desired nostalgic note and possess a fitting cult appeal for the space. They speak to the charming, ragtag nature of the enterprise that has impressed itself so deeply on you. In that respect, there could be no better way to see guests off with a proverbial kiss on the cheek and a wink.

Stepping back out onto Grand, the glow of the Salerno’s sign—and the weight of the red sauce sitting in your stomach—transport you to another place and time. Yes, you feel deeply satiated, but also stirred. Elina’s did not labor to excite you at an intellectual level, to wrap the familiar in a glitzy new coat of paint with all the bells and whistles of a superficial “reimagination.” Rather, the restaurant captured the true essence of those historic Italian-American dining rooms, ones enlivened by the nostalgic yearning for a land left behind and built upon the deep satisfaction of simple, broadly-pleasing recipes done exceptionally well.

It’s easy to romanticize that dying breed of decades-old “Italian steakhouse,” even as standards slip and the brand name transforms into little more than a bauble used to bedeck jars of grocery store pasta sauce. Yes, long after the Sherman House Hotel’s closure, that College Inn name continues to grace Del Monte’s broths and stocks. Will there always be an Italian Village, a Gene & Georgetti, or even a Rosebud? Can those living relics survive the shifting tides of taste (to say nothing of conditions that have toppled even, or especially, the city’s trendiest establishments)? Or will only some fragment, some remnant survive as the greater part of each restaurant’s tone and tenor is lost to history?

You loathe to use the word “authentic,” but something about Elina’s settles that questioning mind. Rusnak and Safin sincerely embody the same Italian-American philosophy that shaped the tradition so long ago. Their work reflects not a caricature of the red sauce genre, but a genuine reckoning with its recipes. The chefs display a deep affection for the category’s essential forms and a firm resolve that knows when there is nothing to add or, better yet, take away. Like next-generation vintners at a family domaine, they confidently steer the ship towards modernity without diluting any of that rare essence that has endeared their product to customers.

Elina’s preparations are faithful, thoughtful, and they resist the tendency to indulge influencers in their shallow marketing drivel. Lovers of Italian-American cuisine will find themselves immediately at home. Foodies will be pleasantly surprised at how easily the genre can be adapted for contemporary tastes. The peacocks will prance about and pose in the intimate space, but that slick background and geotag will tell their followers very little. For, from afar, the experience that the restaurant is selling prompts a double take. Those old recipes, in that dingy space? Why bother seeking out that same goopy, saucy slop that can be secured on nearly any block?

Because a meal at Elina’s is felt as much as it is tasted, and the restaurant—defined almost as much by what it chooses not to do—can steward Chicago’s appreciation of Italian-American dining towards a future in which nothing essential is lost. Rusnak and Safin must be respected for their devotion towards a cuisine, a culture, and a living history that is often drawn upon but rarely defended. That purity of spirit makes Elina’s a special place.