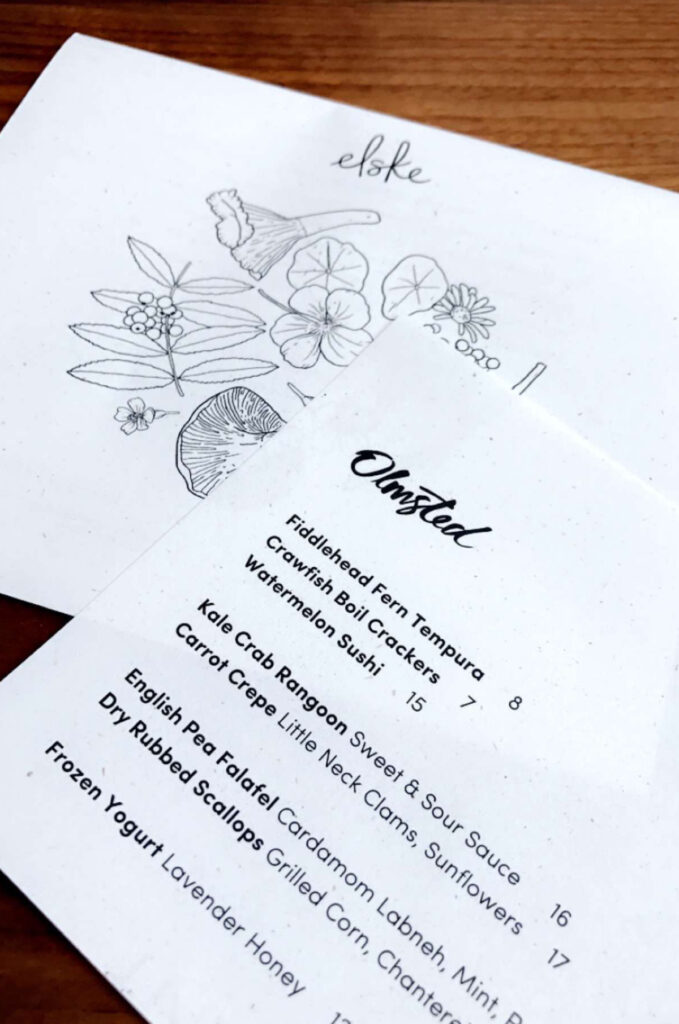

You first found your way to Elske in August of 2017, and—for all intents and purposes—the restaurant formed little more than a chance venue on that occasion. The place had been open since December of 2016. But Greg Baxtrom of Olmsted was in town, and, for one evening only, he’d be bringing Brooklyn’s hottest haunt to Chicago.

Both restaurants had made it onto Bon Appétit’s list of 50 finalists for the yearly “Best New Restaurants in America” list. And Baxtrom—who had studied at Kendall College and risen to the rank of sous chef at Alinea—was described as a “longtime close friend” of Elske’s chef-owners (with David Posey having even helped open Olmsted in 2016).

Ultimately, the collaboration comprised little more than a half dozen of Baxtrom’s dishes placed opposite the entirety of Elske’s menu. The visiting chef impressed with crowd-pleasing favorites like “Fiddlehead Fern Tempura,” “Crawfish Boil Crackers,” “Watermelon Sushi,” “Kale Crab Rangoon,” and “English Pea Falafel” alongside more thought compositions like a “Carrot Crepe” (with little neck clams and sunflowers) and “Dry Rubbed Scallops” (with grilled corn, chanterelles, and blueberries).

Though, admittedly, the Olmsted items commanded your attention, you supplemented them with Elske’s own confit lobster mushrooms (with cherry and purslane), crispy veal sweetbreads (with apricot, mint, and honey), and miso-braised porcelet (with shoestring fries). Baxtrom’s lone dessert that evening was a lavender honey frozen yogurt. While, from Anna Posey, you enjoyed a raspberry meringue (with Norwegian dulce de leche) and a sunflower seed parfait (with sour honey).

It might have been easy for Baxtrom to steal the spotlight that evening, but you walked away thoroughly impressed by the host restaurant—later returning twice during the following month to sample the rest of the Poseys’ fare. The powers that be would seem to have agreed: Elske was named #2 on Bon Appétit’s final “Hot 10” list and would earn one Michelin star just a couple months later. (Olmsted, though not earning the same plaudits, would form a springboard for Baxtrom to launch two other lauded New York City restaurants with yet another on the way).

The Poseys’ cooking had made a great impression on you, but, over time, Elske would recede into the background. Oriole and Smyth, which both also opened in 2016, would come to define the next generation of Chicago fine dining (with the latter of the two, as readers might know, rewarding as many repeat visits as you could stand to make). Joe Flamm could still be found making gnocchi at Spiaggia, Ryan Pfeiffer’s extended tasting menus enlivened Blackbird, and Iliana Regan impressed—no matter how eccentric the theme—behind the stove at Elizabeth. The city’s “omakase boom,” too, was just around the corner.

So it came to be that Elske got lost in the shuffle. Perhaps you even took the restaurant for granted. It would entice you enough to visit two or three times a year. The cuisine would be creative and intellectually stimulating, yet it would fall short of the pomp, circumstance, and pure hedonism of other establishments. Thus, the concept didn’t quite break into that perceived upper echelon of eateries that demanded—for you—consistent, concerted patronage.

However, the pandemic’s razing of the dining scene—alongside what you feel to be legitimate growth in your taste preferences—has catapulted Elske to the very forefront of the city’s restaurants. More than five years after its debut, the Poseys’ work is more relevant than ever. (You wonder what it might take to earn that second Michelin star). And, quite simply, you think the time is ripe to engage with a place that has long been unapologetic, if not downright provocative, in expressing its singular conception of flavor and form. Few restaurants in Chicago beg for such thoughtful analysis and, frankly, deserve it.

But first, let’s go back to the beginning.

David and Anna Posey—playfully termed the “One Off Hospitality Group power couple”—met in 2011 when the latter “began her pastry career as an intern at Blackbird.” The former had begun working there back in 2006 after stints at both Trio and Alinea.

David would rise to the position of chef de cuisine at Blackbird, earning James Beard nominations for Rising Star Chef in 2013 and 2014 while holding a Michelin star at the restaurant from the time of the Guide’s debut until his departure. Anna, who originally studied painting and drawing (more on that later), attended the French Pastry of Chicago. After her internship at Blackbird, she worked at Everest before becoming the pastry chef of The Publican and Publican Quality Meats.

David would depart from Blackbird in July of 2014 while Anna would stay on at The Publican, earning StarChefs’ Chicago Rising Star Pastry Chef award in May of 2015. Just two months later, the former would show off the key to the building that would house the couple’s new restaurant. He expressed, at the time, that their goal was “to feature fine dining cuisine in a relaxed atmosphere” via an eight-course tasting menu “in the $75 to $90 range” alongside a “small” à la carte option each drawing on herbs and flowers grown on-site.

Later in the year, it would come to be known that the Poseys were taking over the former Sawtooth Restaurant and Lounge space at 1350 W. Randolph Street. That establishment was ignominiously known for a series of shootings near the venue over the prior two years, and the business was also in the process of having its liquor license revoked. The husband and wife team “weren’t set on any particular neighborhood, or staying in the West Loop” (only some 12 blocks west of Blackbird). But David’s father knew someone who knew the Sawtooth space’s owner, and they saw “enormous potential” in giving the building a new lease on life.

Conceptually, the Poseys’ restaurant was starting to take shape too. The fare would be “similar to Blackbird, but at a lower price.” Meanwhile, the design would be “influenced by the Scandinavian aesthetic,” described as “clean, light and open.” The theme was drawn from David’s own family history: his mother being from Denmark and her home country forming a family travel destination throughout childhood school breaks and summer vacations. Denmark was also where he and Anna had gotten engaged—“in front of a Hans Christian Andersen statue in the heart of Copenhagen”—adding a perfect kind of symmetry to the selection.

By February of 2016, the couple was ready to unveil their eatery’s name: Elske, the Danish word for “love.” (As luck would have it, the two were married “just down the street” from the restaurant’s location).

David would also reveal that there would be “Scandinavian aspects” to the cuisine; however, he did not want to term it “New Nordic.” Rather, the pair hoped “to create an experience that is simple, intriguing and delicious.”

This professed intention would find its anchor in the Danish concept of hygge, “a sense of welcoming and warmth” (likened to coziness) as expressed by the atmosphere. Though coy about the degree of New Nordic influence on the cuisine—“we use the word Danish loosely”—the Poseys did not shy away from embracing the culture’s design principles in order to spur such a feeling.

The “white-washed” two-floor space would be announced by a “neon Elske sign in script” and “outdoor sandy garden” with an “al fresco fireplace” (“used for drink service and eventually food as well”). Inside, guests would find a seven-seat bar and a 55-seat open dining room “with a variety of new as well as 1960s-sourced wooden tables, chairs, and green banquettes.” Handmade dinnerware, meanwhile, was sourced from Little Fire Ceramics (in Chicago) and CG Ceramics (in Cincinnati).

According to designer Erin Boone, the restaurant could be described as “inspired by contemporary Danish design with historic elements.” She thought to bring in some “earthy materials,” some “texture” (via plaster), and custom lighting fixtures while keeping native elements like the “exposed brick,” which was “lovely.” A “cut-out in the first-floor ceiling” would make use of the “great” two-level space and “draw the eye upward” toward a 21-seat private dining room featuring its own separate fireplace.

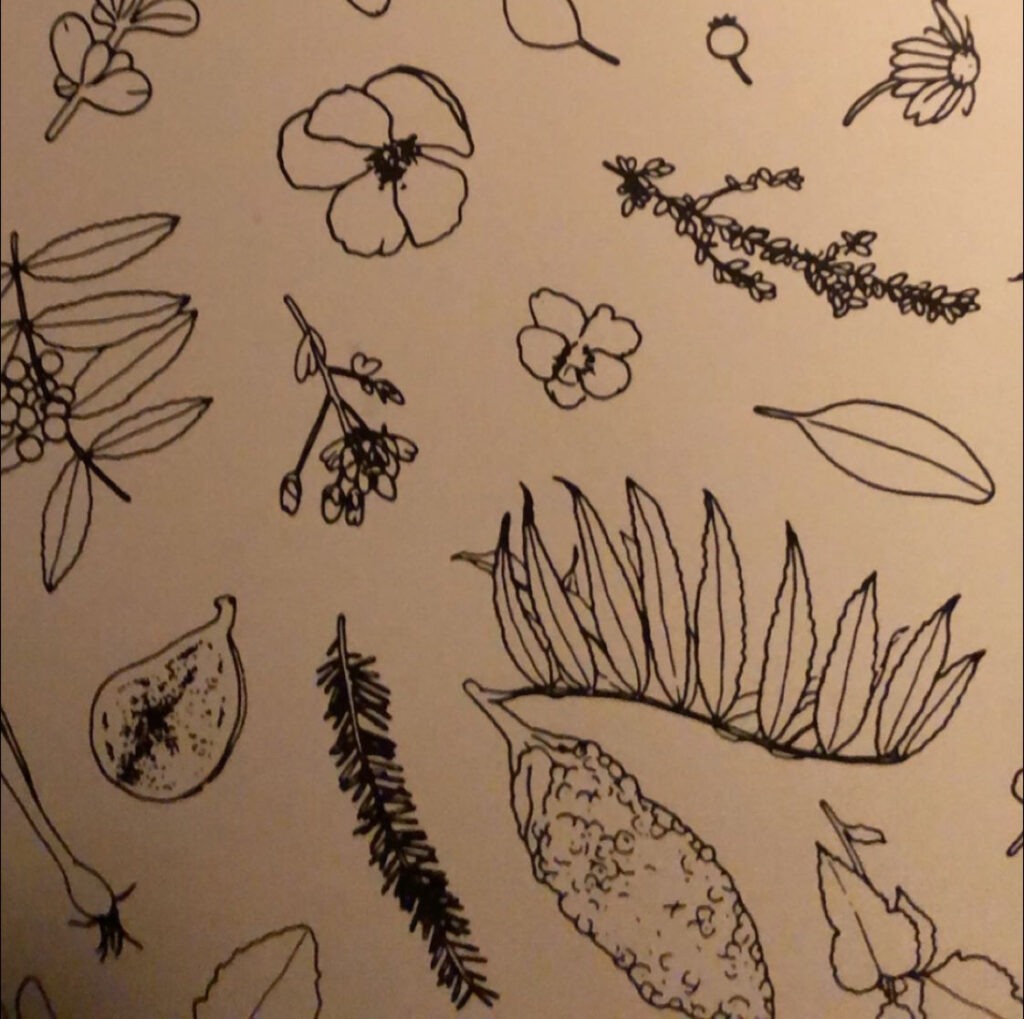

Some of the interior’s most distinguishing designs came from Anna herself: wallpaper in the bathrooms and elevator was drawn from the chef’s sketches of flowers, leaves, and fungi. (Drawing on the classical art training that preceded—and still influences—her embrace of pastry, she had previously done graphic design work for One Off’s establishments while also selling prints, originals, and private commissions via her own website). Adding to the wallpaper’s personal touch, canvases from David’s brother Mark—a talented visual artist in his own right—would hang on the walls. The husband and wife would even be “transforming the building’s third floor into a loft” where “they plan to live.”

Returning to the concept of hygge, Anna describes it as something “you present” when “someone comes to your house to visit — we really wanted to portray that and have it be part of the experience.” “Sometimes,” she says, “you’re in some restaurants and you remember the atmosphere, the feeling, as an event and all of it is this well-rounded thing. We wanted to encompass that feeling when you come in, as a happy place, and it feels like us.”

It would take the better part of 2016 for the Poseys to construct that kind of ambiance, yet Elske would finally be ready to open by the beginning of December. The restaurant launched with an $80, eight-course tasting menu with optional wine ($45) or non-alcoholic ($25) pairings available. Seven à la carte items (priced from $15 to $22), bread service ($7), and a trio of desserts ($14) would complete the comestibles. Meanwhile, the opening beverage program from Blackbird’s Kyle Davidson (who also played the part of general manager) featured four cocktails and close to forty bottles of wine—including some smart selections from Pierre Moncuit, Gunderloch, Aldo Conterno, and Denis Mortet. (David would note at the time that he would like to see the list “grow to around 60 bottles”).

Within a month of opening, Elske was already praised as “one of 2016’s best new restaurants.” The Tribune would follow suit, awarding the Poseys three stars later in January of 2017. The Reader, Time Out, and CS Magazine would echo the same sentiments. However, Chicago magazine would dissent: its critic found the restaurant’s à la carte offerings to be noticeably stronger than its tasting menu and thought the service to be too “fast” and “unceremonious.”

Nonetheless, Elske would continue to ride a tide of good press over the course of the year. The concept was named Chicago’s lone entry on Eater’s “Best New Restaurants in America” list, received second place in Bon Appétit’s “Hot Ten” “Best New Restaurants” selection, and earned one Michelin star in October. Closing out 2017, Anna Posey would be nominated for the Jean Banchet “Pastry Chef of the Year” Award (which she would go on to win) and Elske would be nominated for “Best New Restaurant” (which it would go on to lose to Smyth). But, fear not, they would clinch the “Restaurant of the Year” title from Eater Chicago.

2018 would bring the Poseys further plaudits. David and Anna would share a semifinalist nomination for the James Beard Foundation’s “Best Chef: Great Lakes” award—later reaching the shortlist of five finalists (but losing out to Abe Conlon of Fat Rice). In September, the husband and wife would retain Elske’s Michelin star. And, in early 2019, they would climb back on the JBF merry-go-round once more: being nominated as a semifinalist and, then, finalist for the same “Best Chef: Great Lakes” award (losing, on this occasion, to Beverly Kim and Johnny Clark of Parachute).

2019 would also see the pair compete in an episode of Vice’s Bong Appétit: Cook Off, where they bested a rival couple before Anna defeated David in a final dessert round. Elske would retain its Michelin star once more that fall, and the chefs would see themselves jointly nominated for the 2020 Jean Banchet Awards’ “Chef of the Year” honor. They would take home the title—alongside Smyth for “Restaurant of the Year” and Kyōten for “Best New Restaurant”—shortly before the pandemic turned the industry inside out.

Throughout that period of perpetual indoor dining bans and haphazard reopenings, the Poseys played things carefully. They starting offered weekend takeout in May of 2020, with comforting “Elske at Home” offerings that inaugurally included “Swedish Meatballs with Gravy and Tart Cherry Jam,” “Mashed Potatoes,” and “Chocolate Layer Cake” (all excellent). As Chicago grappled with protests regarding racial justice, the husband and wife would donate 10% of their sales to organizations like Brave Space Alliance, Assata’s Daughters, and BYP100 over the course of several weeks.

In July of 2020, Elske would open its patio for outdoor dining, offering a socially distanced set menu that roughly approximated the kind of fare that the chefs offered pre-pandemic. Meanwhile, the restaurant would continue its “at Home” offerings for guests who were not yet ready to contend with increased interpersonal contact. Each week’s selection was graced with one of Anna’s illustrations—the takeout option culminating with a delectable “Swedish Meatball Burger” and fries.

As colder weather approached, the Poseys announced at the start of October that their restaurant would be taking “an extended winter break” until “early 2021” rather than contend with the demands of strictly limited indoor dining throughout the season. Their decision would prove to be prescient, as restaurants would once more be forbidden from hosting diners inside just a couple weeks later. Elske seemed intent to proceed at a slow and steady pace, retaining—through their caution—some fundamental sense of control while facing uncertain conditions that totally crippled peer establishments.

In late January of 2021, indoor dining would once more be allowed. But Elske would stick to its original plan: seeing through the entirety of its winter break, the further loosening of restrictions at the start of March, and the first rollout of vaccinations. The chefs set a formal reopening date of April 22nd, and—two days after that—you eagerly attended your first dinner there in close to two years. It was a grand occasion, highlighted by familiar bites from the set menu alongside à la carte dishes of agnolotti, sweetbreads, and pork all washed down with a rather affordable bottle of Selosse “Substance.”

The restaurant looked to be back at its best (and clearly benefitted from a wonderful wine list whose prices reminded you of what the market looked like before the pandemic). Yet, after operating Elske through May, June, and most of July, the Poseys decided to take a step back. Citing “staffing shortages,” the chefs admitted they were “unable to execute Elske at the level of service and hospitality” they “strive to uphold.” (This despite the very fair addition of an optional 3% surcharge going “directly to providing health benefits for the Elske staff”). You found the announcement to be foreboding, but it ended on a note of hope: they would “take some time to renew the restaurant,” focusing “on how to become more sustainable and successful in this new chapter of the service industry.”

On December 8th of 2021, Elske’s “re-re-re opening” was finally on. The Poseys, in the meantime, had welcomed a son, Henry, into their lives. Anna would continue to take “a half-step back” from the restaurant (while remaining “at the helm of the dessert menu” and “in close contact with staff”). And David, having cherished his time with the newborn, asserted “we’re definitely feeling reinvigorated” and “I know we’re planning on being the same restaurant we were before the pandemic started.” In April of 2022, his words would ring true as Elske retained its Michelin star for a fifth straight year.

Today, the Poseys’ restaurant looms larger than ever. It has reached the half decade mark of maturity while weathering what may prove to be a once in a generation paradigm shift for the industry. It has tallied up a whole host of nominations and awards while securing Bibendum’s favor for the foreseeable future. It stands on a distant stretch of Randolph Restaurant Row that, after years of seclusion, is now set to reach critical mass. And its cuisine—always a masterful blend of the forward-thinking and delicious—remains among the most exciting in the city.

Yes, the time is ripe to engage with Elske and put it through the paces that might serve to define it as one of Chicago’s finest establishments. For the sugar rush of the restaurant’s opening publicity has worn off, and promoters of all stripes have trained their attention on the next shiny object. That leaves it to independent diners to take up the fight and discern—through the evaluation of lasting quality—if Elske is well on its way to becoming an institution.

While you possess several years’ worth of memories to draw on, you think it best to focus on Elske’s post-pandemic era. That comprises, thus far, five meals in 2022. As usual, you will condense the sum of these experiences into one comprehensive narrative.

With that said, let us begin.

1350 W. Randolph Street once seemed like a lone fine dining outpost. Now, it’s a positive oasis. Of course, Smyth lies just half a block north—now tucked under the shadow of a hulking apartment building called The Mason. Ever, too, has sprung up just a bit further down Ada, occupying the ground floor of the 290,000 square foot Fulton West office complex. Yet those places are “worth a detour,” and it makes sense that they would be nestled away from the heart of West Loop’s action.

Elske, rather, flows out from all the hubbub that begins just east of the Kennedy Expressway and stretches more than dozen blocks west. The area is the dominion of Alinea, Boka, DineAmic, Lettuce, One Off, and newcomers like Sancerre. But there are plenty of upstarts comprising myriad cuisines. There’s a food hall, pizza parlors galore, and an assortment of national chains like Boqueria, City Winery, Jeni’s, La Colombe, Nobu, Shake Shack, and sweetgreen. Two titans of the food world—McDonald’s and Mondelēz—have made the neighborhood their own (while Google’s presence surely hasn’t hurt either).

Somewhere past Morgan Street, the energy begins to fade. Restaurants are exchanged for what remains of the old meatpackers and wholesalers. There’s the odd gym, school, and loft building, but the creeping tide of development has yet to extend the preceding sprawl’s excitement all the way down.

Approaching Randolph Restaurant Row eastward from Union Park tells a different story. The lot that once held BellyQ, Urbanbelly, and—once upon a time—Michael Jordan’s one sixtyblue is now home to a twenty-five-story apartment building titled Parq Fulton. Kaiser Tiger still occupies the opposite corner facing Ogden Avenue. However, it now neighbors a new seven-story “parking and retail structure” built as part of the Local 130 U.A. campus, and there’s an adjacent 503-vehicle garage (running along Ada) on the way.

With another apartment building already located at the northeast corner of Randolph and Ada (and The Mason located just behind it), Elske finds itself smack dab in the middle of Restaurant Row’s rising commercial-residential capstone. The restaurant, alongside a bridal shop and a location of Gyu-Kaku, seems increasingly dwarfed by its neighbors. But the changing composition of the block has only worked to transform the establishment from a lone bright spot on a barren plain into a gastronomic hideaway insulated from the growing bustle.

That being said, the building looks the same as ever.

Though surrounded by faded, reddish-brownish brick on three sides, Elske’s façade is totally transporting. The cool, gray stone—complete with a neat, squared cornice—stands apart from the rest of the block. Sawtooth had obscured this crowning element as part of its overwrought, blocky design. But any trace of that is now gone, leaving a delightfully understated exterior accented by black framed windows, dark gray curtains, and an assortment of baubles.

There is, of course, the hallmark neon sign that glows a glorious electric blue. Yet that distinguishing element is joined by all manner of other tchotchkes: a letter board, flowerpots, candles overflowing with melted wax, and a Bibendum statuette. Depending on the season, you might spy cacti or a village of expertly iced gingerbread houses. Perhaps you’ll even see the Poseys’ Dutch-made WorkCycle, used to transport fresh ingredients from the local farmers’ market. From the start, the space feels lived in (and, on account of that third-floor loft, quite literally so). It brims with personality in an effortless manner that strikes right at the core of what it means to be hosted—or, as the chefs might term it, hygge.

Passing by the front of the restaurant, you come to a low wall with a wooden gate. Affixed to the front, there’s a small bench, which forms a rather courteous platform for those who wish to wait for the rest of their party to arrive. Through the gate, you find Elske’s patio, a splendorous area defined by pebbled stone, planters, birdbaths, trees, lanterns, patches of garden, and even an accompanying gnome. The towering brick wall of the adjacent building lends the zone an intoxicating feeling of snugness. It is, thanks to the gate and the surrounding canopy, every bit an urban oasis.

Nonetheless, the patio is functional too. It comprises more than a half dozen sturdy tables surrounded by weighty metal chairs. There’s a gorgeous fireplace, whose chimney climbs up and over the wall of the adjacent building, as well as a hearth surrounded by a few benches (perfect for postprandial imbibing). When the weather cools, they may be draped with pelts. Or guests may be invited to fetch a blanket out of the wooden crate placed off to one side. A sign affixed to the firewood rack warns you to “PLEASE ALLOW THE ELSKE STAFF TO TEND THE FIRE.” (Woodsman fantasies aside, that’s probably a good thing).

Elske’s patio forms a large part of the restaurant’s soul, especially in an era of ubiquitous, corporate contrived rooftops that use their superficially glamorous settings to squeeze consumers. As with the bric-a-brac embellishing the restaurant’s façade, this outdoor space communicates a level of care. Its design is organic and homey. Everything is tended to—every possible guest need has been anticipated—and the staff welcomes you to enjoy the confines with obvious pride. Even those who dine within the restaurant—or, best of all, at the indoor/outdoor threshold whenever the windows are open—will find themselves gravitating towards the space.

As you pass through the patio and pull open the restaurant’s front door, the naturalistic aesthetic yields to one that is subdued and pristine. There is still plenty of greenery at play, yet it serves more to accent—rather than define—the interior. Instead, the space is awash in polished tones of black metal, dark gray concrete, light gray stainless steel, dark brown wood, and off-white countertop. The walls are rendered in a soft white with wooden ribbing set throughout. The lighting—drawn from candles, bare bulbs, and overhanging lanterns—is decidedly warm. There’s more of the reddish-brownish brick, as well as sets of banquettes and chairs done in a firm (but comfortable) medium gray fabric.

Spatially, the host stand faces away from the dining room’s rear wall and roughly aligns with the middle of the seven-seat bar. Guests situated there are given a partial view into the kitchen, which occupies a flowing cutout space between the bar and the dining room proper. The liminal nature of this construction lends a certain sense of intimacy between the back of house and the diner (while never commanding too much attention or interrupting proceedings). Beyond it lie three orderly rows of four-tops, two-tops, and the occasional six-tops. (Other than the tables that abut the patio, the two four-tops that look out onto Randolph Street might be the nicest).

The bathrooms (graced by Anna’s illustrations) lie around a corner located behind the host stand and bar. There, guests may spy a miniature version of the neon sign that hangs out front. They also can access the restaurant’s second floor private dining room, which—while you have never visited it—looks like a wonderful extension of the first floor’s aesthetic. The space’s finishing touches, mounted on walls throughout the interior, come from framed versions of Anna’s illustrations alongside canvases painted by her and David’s brother.

Looking only at its essential elements, Elske’s interior almost seems austere. The furniture is solid, subdued, and impeccably arranged. Its surrounding materials are neutrally toned and crisply defined by vertical lines. The room glows with a kind of otherworldly sheen. Yet, no matter which seat you have taken over the years, the resulting feeling is one of solace. For the restaurant’s lighting—be it the rays drawn from the windows or the warmth of the hanging fixtures—washes over any sense of starkness. The space’s naturalistic elements extend the charm of the outdoor patio/garden. And the many expressions of artwork affirm an aesthetic that is singular, personal, but not at all ostentatious.

The Poseys have realized an environment in which you simply love to sit. There’s nothing ornate or precious about it. You do not get the sense that you are awash in a sea of humanity. Rather, you can appreciate the hum of the room while feeling, among your party, total seclusion. You can focus solely on each other—as the evening flows around you—or disengage for a moment to indulge in some anchoring detail: the flicker of a candle, buzz of a neon sign, or roar of a fireplace.

No part of Elske’s design tries to impress. The restaurant only begs to be discovered, to be subliminally appreciated as it works to construct the kind of hospitality experience that stirs the soul. That means offering a blank canvas for genuine social bonding, presenting a setting in which guests may turn inward rather than jockey for attention with their neighbor. When you break eye contact with your companions, no avalanche of senseless detail invades. The “Danish” theme does not enforce itself. Instead, you catch some small reflection of the chefs’ own personal story, and it promises that this is a place where patrons can let go and begin to write their own.

This push-pull between effortlessness and intention forms the intoxicating quality of authentic, understated design. Such a dimension cannot be ascribed to any one aesthetic decision. It cannot be contrived. But it comes about naturally as a result of many little artful touches made with the creators’ own tastes and the desired customer experience in mind. As guests and staff alike make use of the space—as seasons change—this creative process is iterated on to expand and enrich how hospitality is expressed at an ambient level. That, you think, amounts to the sense of hygge that Elske is aiming for, and the restaurant’s setting—due to the described kind of entropy—may already even be called timeless.

Having gotten your bearings, you are recognized by the hostess, warmly greeted, and led—past the bar, past the kitchen—to your favored four-top closest to the front of the building. You pick a chair and settle back into its ample frame. In front of each seat, Elske’s menu, as always, lies cleverly obscured underneath the napkin. A server stops by, offers their own gracious welcome, and inquires about your water selection. They deposit doilies underneath the glasses to demarcate sparkling and, in short order, return bearing a beverage list to boot.

While deceivingly accessible on the surface, Elske’s drink selection has long impressed you with its surprising depth. The four cocktail options with which the restaurant opened have now expanded—under bar manager Monica Casillas-Rios—to include a fifth. Each is currently priced at $14, with offerings over time comprising classic categories such as “Shaken,” “Sour,” “GinTonic,” “Swizzle,” “Spritz,” “Martini,” “Collins,” “Cobbler,” “Stirred,” “Sazerac,” “Old Fashioned,” “Gløgg” (a sort of mulled wine), “3-Parter,” and “Milk Punch.”

Though the chosen base spirits (aquavit, vodka, mezcal, bourbon, and rum at the moment) are representative, accompanying elements are always seasonal. “Shaken,” for example, combines aquavit, gin, and Campari with refreshing notes of strawberry and grapefruit. “Stirred” blends bourbon with limoncello and chamomile. The “Martini” draws on Salers gentian liqueur and a cucumber-dill vermouth to go with its vodka. While the “Collins” combines mezcal and Ancho Reyes chile liqueur with cleansing notes of snap pea and lovage.

Even the non-alcoholic options ($11) get in on the act. The “Floral” combines Seedlip Grove with hibiscus-melon clarified milk tea and banana in a manner reminiscent of the “Milk Punch.” The “Herbaceous,” meanwhile, blends Seedlip Garden with celery, snap pea, and lemon.

Of course, Elske maintains a fully-stocked bar with a more extensive spirits list on offer too—ensuring that the restaurant is equipped to cater to more traditional tastes. Yet the concise list of cocktails that is advertised on the menu, by enabling the thoughtful sourcing of components, helps forge a degree of continuity with the larger concept. Your sense of the season, the farmers’ market, and the garden that lies just outside the window extends directly into the glass.

On draught, the restaurant currently serves a wheat beer from Art History Brewing in Geneva, a pale ale from Hopewell Brewing in Chicago, and a sour ale from WarPigs Brewing (a collaboration between Indiana’s 3 Floyds and Copenhagen’s Mikkeller). There’s also a refreshing hard kombucha on offer from JuneShine in San Diego—which, though usually offered as a low ABV option, actually clocks in just a half percentage point above the beers.

The ”Bottles & Cans” section currently features a kölsch from Germany’s Heinrich Reissdorf, a wild saison from Chicago’s Whiner Beer Co., a dry-hopped lager from Chicago’s Off Color Brewing, and a Trappist ale from Brouwerij Westmalle in Belgium. Rounding things out are a pear cider (from Michigan’s Virtue) and an apple cider from the always reliable Eric Bordelet. A rotating trio of potent house-made snaps—currently offered in fennel, serviceberry, rhubarb-strawberry, and hoja santa flavors—are also offered for those looking to indulge in the classic Danish drinking ritual. (While you found the serviceberry to be a bit too potent, the rhubarb-strawberry was luscious and sweet).

But the wine, as always, is where things really get exciting. Though Elske, to the best of your knowledge, does not formally have a sommelier or wine director at the moment, the list has been excellently stewarded over the years by Kyle Davidson (now of Rose Mary) and Marie Cheslik (who went on to found Slik Wines alongside another Elske alumna).

The by-the-glass offerings range from an Italian rosé ($11) and Portuguese white field blend ($12) at the low end; a Loire Sauvignon Blanc ($14), Languedoc red blend ($14), and J. Christopher’s “JJ” Willamette Pinot Noir ($15) in the middle; and a Bourgogne Blanc ($16), Sangiovese blend ($16), and non-vintage Champagne ($20) at the more premium end. Though you do not find any of these selections to be particularly exciting, they are widely representative, accessible, and offer good value. (Elske’s past lists, to their credit, have included producers like Aubry, Minimus, Benjamin Leroux, Wyncroft, Sandhi, Pierre Cotton, and Domaine des Roches Neuves).

The bottle list, however, retains some of the magic that has long made the restaurant a sleeper destination for fine wine at a highly appealing price. Though the Selosse is gone, Elske maintains a smart array of bubbly from producers like Suenen (“Oiry”), Marzilly (“Ullens”), Paul Bara (“Réserve”), Marie Courtin (“Indulgence” rosé), Georges Laval (Cumières), and Laurent-Perrier (“Grand Siècle No. 24”). The pricing of the Laval ($195) compares favorably to the same bottle from the same vintage at Maple & Ash ($235), as does the Laurent-Perrier ($250) relative to the same release at Oriole ($275).

Rosé proves a difficult category for most Chicago restaurants—even though you think its more serious styles are among the most enjoyable food wines around. Elske offers but three options, yet two of them are rather fine: Rabasco’s “Cancelli” from Montepulciano ($55) and Bruno Clair’s “Le Centenaire” bottling from Marsannay ($72). The “Orange” category, by comparison, is more than double the rosé section’s size. You think that is both a bold and wise choice, for the full-flavored, slightly sour style they comprise marries beautifully with the Poseys’ food. The Ribolla Gialla from Radikon ($85 for a 500 mL bottle) and “Côtillon des Dames” by Jean-Yves Péron are your favorites of the bunch, yet the eclectic assortment leaves much to discover.

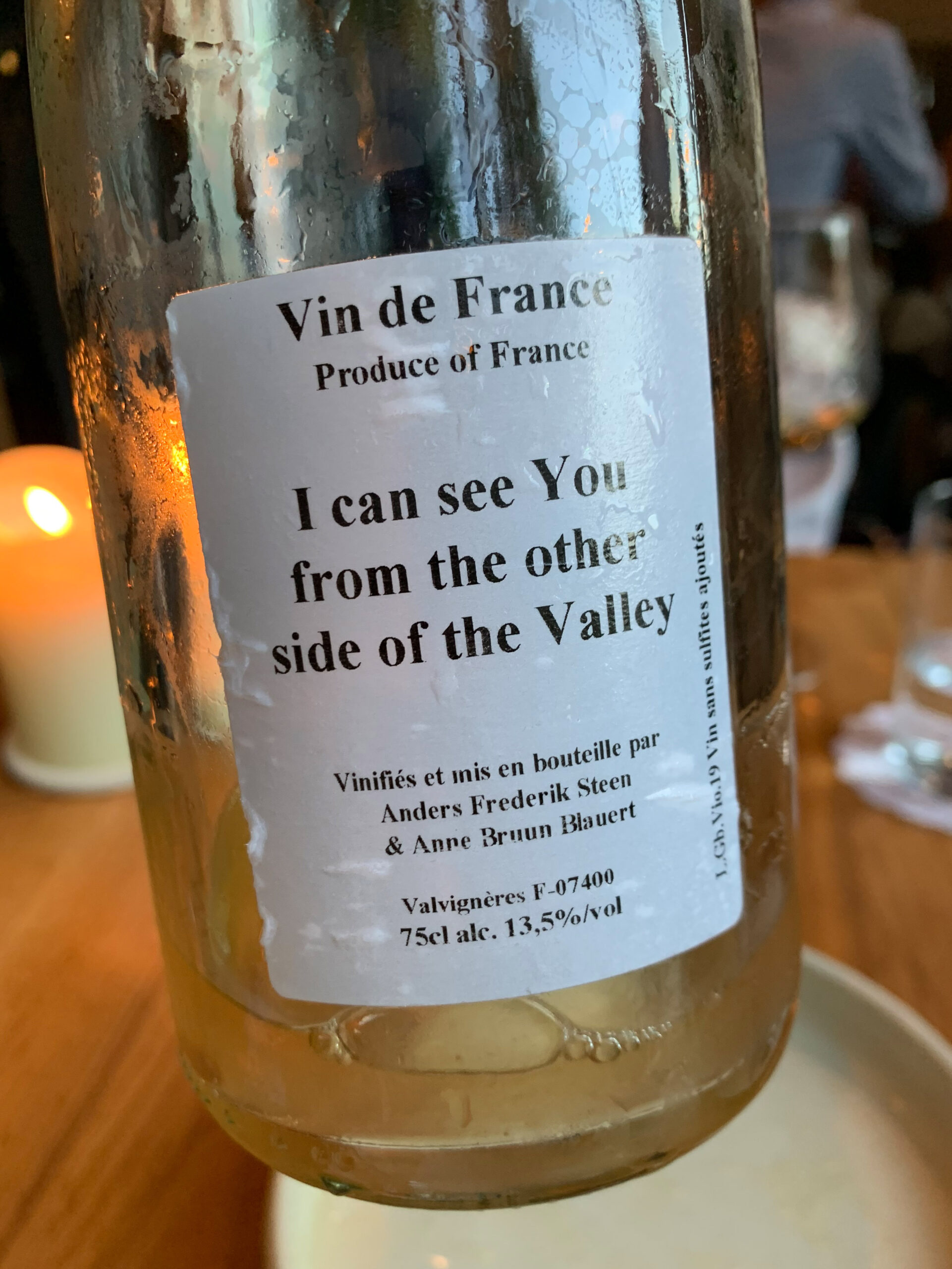

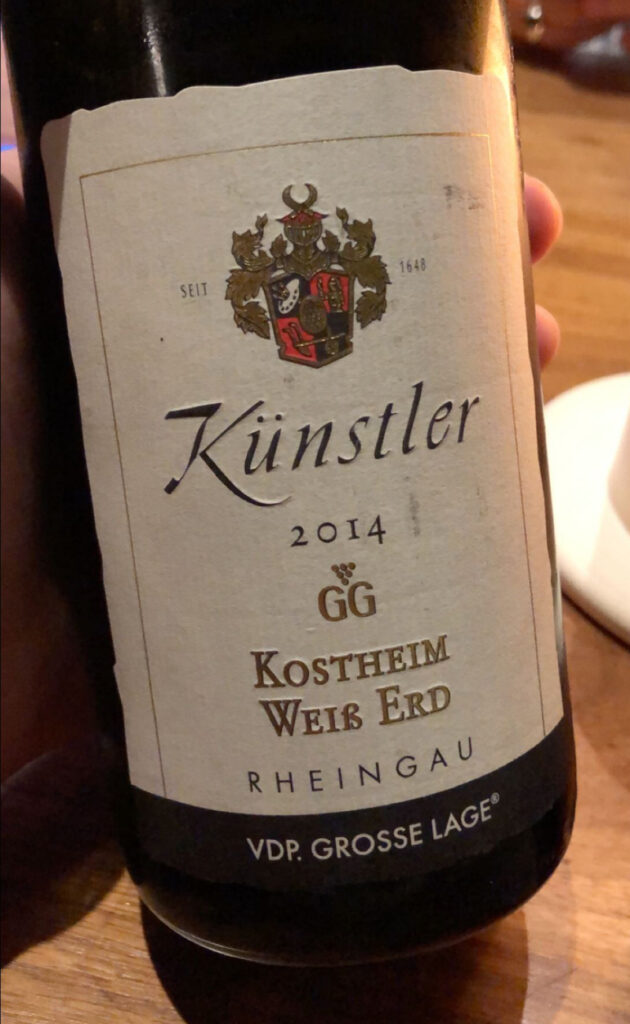

Elske’s white wine selection runs the gamut with Rieslings by Beurer ($58), Vollenweider ($125), Hermann Ludes ($78), and Koehler-Ruprecht ($135). There’s a couple Sauvignon Blancs (from Gerard Boulay and Alexandre Bain) and Chenin Blancs (from Leo Streen and Loire’s La Grapperie), as well as a luxurious $240 white Rhône blend by Pierre Gonon (“Les Oliviers”). On the more natural side of the spectrum, you have enjoyed Anders Frederik Steen’s slightly sweet “I can see You from the other side of the Valley” pét-nat of Grenache Blanc ($88) and the biodynamically farmed 2016 Mâcon-Chaintré from Maison Valette ($95) made with 65-year-old vines.

Guests looking for a more familiar expression of Chardonnay will find themselves spoiled for choice. The 2018 Peay “Estate” ($100), 2019 Bindi “Kostas Rind” ($148), 2019 Littorai “Charles Heintz Vineyard” ($198), and 2018 Bernard Moreau Chassagne-Montrachet ($240) are each excellent options. While the pricing on the latter bottle did not seem to make sense, you ordered it anyway and was pleasantly surprised to find that it was actually Moreau’s premier cru “La Maltroie.” Thus, the cost—as is true with so many of the restaurant’s selections—actually represented a great value. (The 2017 vintage of the Peay, for example, costs $142 at Ever, and the 2017 vintage of the Bindi costs $162 at Sepia).

Elske’s red wine selection, by comparison, feels a bit lacking. There’s a range of Pinot Noirs from Alsace ($56), Rheinhessen ($84), Rully ($95), Arbois ($115), Mendocino ($120), and Australia ($148). A couple of Gamays from California ($56) and France ($60) provide additional value alongside a Tuscan Sangiovese ($60), Etna Rosso ($65), and Crozes-Hermitage ($60). The 2018 Trousseau from Les Matheny ($128) and 2020 Côtes du Rhône by Domaine Clape ($130) hit the right sweet spot between price and depth of flavor. But the domestic Cabernet options from Avennia ($165), Tres Sabores ($180), and Gallica ($395) seem less appealing.

You will concede that David’s cuisine—often headlined by lamb or beef—pairs well with these wines. They also certainly appeal to the archetypal “Chicago steakhouse diner” palate while avoiding any of that genre’s most notorious, somewhat anonymous offerings. And you will also admit that your lack of familiarity with those producers—despite them scoring well—may color your perception. The selections are still distinctive and priced in a friendly manner. So perhaps you are only scapegoating these bottles because they are among the more expensive options in a category that—compared to the whites—lacks best in value producers (like Koehler-Ruprecht, Valette, Peay, Littorai, and Moreau).

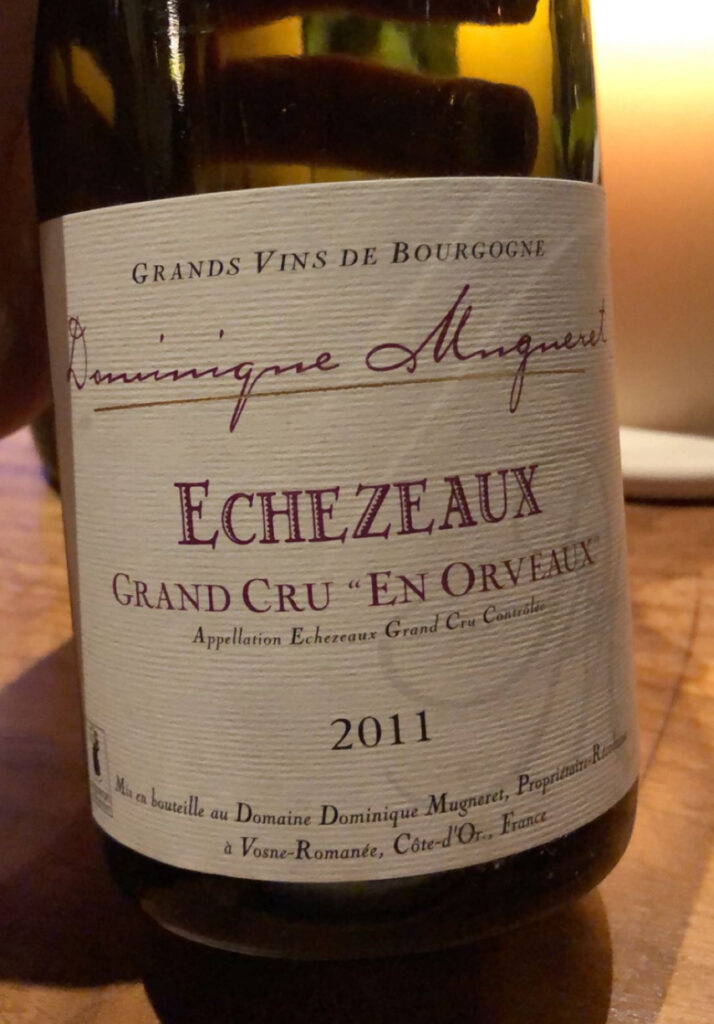

Of course, any oenophile’s eyes are certain to bulge when they spy Elske’s 2011 Domaine de la Romanée-Conti La Tâche ($3,200). High as that price may seem, it’s an absolute steal compared to the current $7,440 Wine-Searcher average—especially for a vintage that has entered an early drinking window. However, that superlative value aside, you would like to see the restaurant’s selection of reds offer the same allocated, high-QPR bottles seen elsewhere across the menu. That may prove tricky without distinct leadership for the program, but past lists have indeed stocked appealing options from producers like Denis Mortet, Aldo Conterno, Arnot Roberts, Château de Fonsalette, and Ridge. Nonetheless, for now, you typically utilize the rosé and orange wines to bridge the gap.

Still, this weakness aside, you think Elske has maintained a very good wine program. Each section’s selection is roughly ordered from lightest to heaviest—a practical decision that aids diners in finding a stylistic match without demanding they decipher more esoteric grape varieties and regions. The mark ups, as you have already shown, are minimal—coming in at (or slightly below) just twice the retail price (rather than the three or four times premium seen elsewhere). This is particularly laudable when it comes to Michelin-starred dining, a setting where special occasion customers may be induced to spend more than is usual for the sake of appearances.

Yet the value does not end there. The by-the-glass list, though missing some of the renowned producers that once featured, retains a friendly entry point of $11. The offerings, barring Champagne and including many of the most popular varieties, top out at $16. Overall, out of 63 total bottles on offer, 19 are priced in the $50-$70 range while 38 come in at $100 or lower. That leaves 25 wines that might be termed “finer” (yet, in truth, still reflect a degree of value that would be hard to come by on more comprehensive lists). Lastly, a corkage fee of $33 per 750 mL bottle—with no limit on the number that guests bring—offers a very appealing option for those looking to enjoy something special from their own collection.

With this kind of foundation and pricing philosophy in place, the program has a ton of latent potential. You think that is particularly true when it comes to biodynamic, low-intervention, or otherwise “natural” wines—which have only begun to appear on Elske’s list and that fit the restaurant’s identity to a tee. Shepherding the growth of the entire selection, perpetuating its more than half a decade of quality, would seem to be one of the most rewarding beverage jobs in the city. You hope someone steps up to the task, as it is somewhat of a shame that these virtues (and this buying power) are not being exploited to the fullest for the sake of local customers. The restaurant deserves a reputation as one of Chicago’s finest wine destinations. Nonetheless, in its present state, the program still rewards drinkers at all levels of connoisseurship with a concise, curated lineup. You eagerly await browsing the list’s additions each and every time you visit.

The wine service, though lacking the leadership of a bona fide sommelier on the floor, is conducted admirably. Of course, it helps that there are no particularly aged selections on offer that might demand gentle uncorking or decanting for sediment. But you have found your servers’ mechanics to be both proficient and natural. They have been able to juggle up to a half dozen bottles during the course of a meal, ensuring glasses always remain filled and that the flow between different wines remains steady as salad yields to fish yields to meat. Moreover, the team shows an organic interest in the selections they offer—cultivated, in part, through staff tastings alongside a simmering curiosity regarding some of the list’s more notable producers.

This plays into the overall standard of service, one that is established from the very moment you enter the restaurant. Despite the Michelin star, there are no white tablecloths nor are there suits. You do not witness any contrived synchronization (pulling out chairs, pouring water), and the spiels—even when dining with newcomers—are kept to a minimum. The absence of these elements may very well stand in the way of pleasing Bibendum’s target demographic of roving gastrotourists (and, thus, reaching the next rung of the Guide’s ratings). But, in practice, the restraint demonstrated by Elske’s service standards works to affirm a larger identity that strikes you as far more valuable than the cookie-cutter theatrics seen nearly everywhere else.

You are no expert on hygge, but the concept seems rather distinct from “luxury” as it is typically conceived in fine dining. The latter, by reaching towards the ultimate refinement, deals in fantasy. The setting (and the interactions that take place within it) prize a smoothness of so great a degree that the interpersonal element of the experience runs the risk of seeming uncanny. Perfection forms the guests’ expectation because the staff are, essentially, strangers—who, for hundreds of dollars per head, are tasked with delivering the kind of hospitality that surpasses the quotidian. Dealing with a vast clientele that comprises all manner of values and cultural codes, luxury restaurants dazzle with a distinct style that is sure to please the widest array of patrons.

Hygge, to you, has more to do with the substance of hospitality—that is, its emotional core. The “sense of welcoming and warmth” presented when “someone comes to your house to visit” has little to do with fancy furniture, perfect coordination, or scripted frippery. It really does not even demand that the food and drink be of an extraordinary quality. Rather, it is the spirit of the host’s every gesture—their presence and sensitivity to their guests’ needs at any given moment—that defines what you feel. The goal, as with luxury, is not to impress, but to please one’s guests wholeheartedly, with the utmost joy, no matter how humble the material one has to work with. Hygge is canny hospitality: a performance that cannot be formulated or standardized because it comes sincerely from within. It takes as its stage the theatre of life—or, at the very least, a setting that authentically reflects the predilections of its performers. Only then need they not act, but merely react to whatever each moment brings.

Elske’s understated façade, sprawling patio, subdued interior tones, orderly arrangement, and sturdy furniture form the foundation. The greenery, fireplace, flickering candles, glowing neon sign, and assortment of artwork set the mood. Then, the staff—clad simply in shirts and aprons—are set loose.

Prefacing the start of the meal, your interactions with the server are warm and refreshingly casual. They breezily meet the energy of your party with a laugh and a smile (rather than commanding its attention with some rehearsed introduction). The wine order, no matter its length, goes down easily. As does the food selection—regardless of the total number of dishes or your desire to intermix the set menu with à la carte offerings. (You recall one occasion many years ago where a similar request, made at Sepia, went disastrously. The more substantial à la carte fare was all lumped together at the beginning and then followed, jarringly, by the dainty first bites of the tasting menu).

Once your orders are set, the flow of the meal is conducted by a mixture of front- and back-of-house staff. The open design of the kitchen—along with a corner passageway (where the front neon sign hangs) that sneakily connects it to the far end of the dining room—facilitates the coming and going of each course. Dishes are deposited and described concisely, yet there is great fluency and verve to the locution. Rather than offering a Gish gallop of esoteric ingredients and techniques, each presentation leaves enough room for the Poseys’ food to surprise and delight the palate. The complexity of the flavor combinations is apparent, but you’re not beaten over the head with it.

When there’s a story to tell—as with the restaurant’s longstanding “Tea of Lightly Smoked Fruits and Vegetables” or ingredients sourced from its garden—it is communicated with a sense of familiarity and ownership. That rings especially true when interacting with the back of house, who trot out the very dishes they specialize in. Their diction strikes you as unrehearsed yet smooth in a manner that only intimate familiarity with a preparation can yield. Watching them walk over from a kitchen area that remains within sight and that feels accessible lends the exchange an appealing fluidity. The back of house, empowered in this way, forges an overarching presence and personal bond with the guest that can often go missing—even at the most renowned restaurants—when they are cloistered away. They appear at the table not as a contrived cameo, but meld seamlessly into the rest of the team.

That, perhaps, is the best way to characterize Elske’s service in aggregate: a cohesive team that operates with precision, positivity, and a soft touch. Nothing feels forced, yet there is also no question that further details and special requests will be accommodated. That, to you, amounts to a pervading sense of naturalness within a world of fine dining that can often seem stiff. The lack of artificiality and formality feels as though you are waited on by friends—or perhaps a real “restaurant family.” The hospitality works harmoniously to channel your attention towards those you share the table with while, here and there, enriching the sense of occasion. Elske’s sense of hygge is, by your measure, realized in a manner that matches Chicago’s other great hospitality cultures.

With your beverage selection settled—and your appraisal of the restaurant’s service out of the way—you can now turn your attention to the Poseys’ food.

Elske opened by offering a $80 “Tasting Menu” comprising eight courses, along with an accompanying wine pairing for $45 and a non-alcoholic option for $25. Today, Elske serves a nine-course “Set Menu” for $115, along with a wine pairing for $55 and a juice pairing for $25. The difference in the number of dishes between then and now is drawn from the addition of one extra amuse-bouche. But the structure of this menu remains the same.

Guests start with the totemic “Tea of Lightly Smoked Fruits and Vegetables,” which is accompanied by another bite. After that, they receive two more morsels served alongside each other. Following that arrives a series of three more substantial composed plates served individually. Those lead to a small palate cleanser and, finally, a dessert. Of these, one of the opening bites (“Duck Liver Tart”) and the palate cleanser (“Frozen Fennel Jelly”) can trace their origin to Elske’s opening menu. They are, in a sense, part of the restaurant’s core identity. That leaves six courses—two amuse-bouches, three composed plates, and one dessert—through which the chefs strut their stuff.

In practice, however, Elske’s set menu seems driven more by offering a reliable, faithful representation of the Poseys’ cuisine from month to month (rather than forming a vehicle for experimentation). Comparing the offerings from March of 2022 to the current menu (in mid-July) may help illuminate this point.

A bite of “Crispy Fried Sunchoke with Black Truffle” made way for one of “Pickled Cucumber with Buttermilk on Rugbrød,” and a bite of “Smoked Fluke Salad on Rugbrød” was substituted for one of “Cured Fluke with Fried Potato.”

Of the composed plates, a dish of “Grilled Fjord Trout with Spiced Carrot, Sunflower Seeds, and Fried Garlic” was replaced by “Smoked Fjord Trout with Roe and Spiced Carrot, Sunflower Seeds, and Garlic.” The “Steamed Halibut with Turnip, Pomelo, and Pecans” became “Steamed Halibut with Mussels, Kohlrabi, and Chamomile.” Lastly, “Roasted Lamb Saddle and Sausage with Cauliflower and Smoked Dates” was only slightly tweaked to include fennel and date jam (in place of the fresh, smoked fruit). Meanwhile, the dessert “Whipped Gjetøst Cheesecake with Poached Rhubarb” has stayed entirely the same.

Overall, these menus reflect surprisingly little development for a period of approximately four months—particularly when traditional, “seasonal” fine dining restaurants may roll out a totally distinct tasting every three months or so. Nonetheless (and especially given those three evergreen bites), you view Elske’s “Set Menu” as an affordable, entry-level delve into what the Poseys’ cuisine is all about. It allays any fear of choosing dishes from the à la carte section (some of which feature unfamiliar ingredients) while also offering appealingly priced pairings and the capacity to accommodate all manner of dietary restrictions. The “Set Menu” has been the subject of criticism since the restaurant’s opening; however, you think it offers newcomers (to Elske or to fine dining in general) a distinctive, easily digestible experience.

(It should be mentioned that the “Set Menu” has just recently added four new dishes at the end of July, signifying that major changes might—indeed—align with a four-month creative cycle).

By comparison, the à la carte section allows the chefs a greater degree freedom (in line with a more “choose your own adventure” form). There are, of course, some perpetual offerings: “Oat Porridge Sourdough,” “Aged Gouda,” “Belgian Endive,” “Fermented Black Bean Agnolotti,” and “Sunflower Seed Parfait.” However, of 15 dishes offered in March of 2022, eight have been replaced on the menu dated July 2022. There is also an additional appetizer, as well as another dessert, added to the mix—raising the total count to 17 items. Thus, apart from a handful of longstanding favorites, guests visiting Elske four months later and ordering à la carte would find an almost entirely new culinary experience. With prices ranging from $21-$30 for medium- and large-sized plates, a hungry couple could eat their way through the section for around the same price as the “Set Menu.”

Personally, you recommend that first-time customers opt for the tasting in order to familiarize themselves with some of the Poseys’ signature preparations. However, they should feel free to supplement those offerings with as many à la carte dishes as they can stand to sample. The kitchen does a wonderful job of interlacing these additions into the natural flow of the “Set Menu,” and, thus, doing so ultimately feels like getting an extended tasting (rather than a haphazard hodgepodge of plates).

On subsequent visits, you would recommend focusing solely on the à la carte fare while, over longer periods of time, keeping an eye out for when the “Set Menu” may substantively change. (Elske kindly allows you to add single dishes from the tasting—like the “Gjetøst Cheesecake”—as part of an order otherwise drawn from the à la carte section).

With this hybrid nature in mind, you will look to analyze all the dishes from both menus while arranging them in the same manner that the kitchen might. This will allow you to not only be comprehensive, but to make comparisons across dishes of similar size and character.

The first item on Elske’s “Set Menu” is one you have already termed totemic. The dish, in one form or another, has always featured at the restaurant, and its very composition reflects the essence of the Poseys’ cuisine at any given moment.

The “Tea of Lightly Smoked Fruits and Vegetables” sounds and looks deceptively simple. Yet, by comprising the totality of the menu’s produce, it affirms the chefs’ commitment to sustainability. Excess product (including, you imagine, trimmings judged unsuitable for any other purpose) is gently heated to draw out its depth of flavor. The fruits and vegetables are then allowed to steep and transform plain water into a layered “tea” with flavors drawn from the many fresh ingredients guests will see used throughout the rest of the menu.

Though you have once seen this tea served with a spoon as a cold gelée (and topped with lightly pickled vegetables), it almost always appears as a lukewarm, brownish liquid served in a small cup. Often times, it arrives with some kind of cracker balanced along its rim—though, on other occasions, the accompanying bite occupies an adjoining plate. But more on that later. The flavor of the tea itself has vexed you over the years, seeming pronouncedly earthy, vegetal, and bitter in a way that was not immediately appealing. (This could have something to do with changing seasons and the predominance of brighter, more pleasing produce during the spring or summer). The liquid also possesses a surprising tannic quality, exacerbated by the lukewarm temperature, that lives up to the mouthfeel of “tea” but has also served to make those jarring notes more persistent.

However, in 2022, you find the “Tea of Lightly Smoked Fruits and Vegetables” to be more refined, better balanced, and altogether intriguing. While it is obvious that the broth’s constituents must constantly change, you are unsure if the recipe or process involved in making it has. Perhaps, more than anything, your palate has simply grown over the past few years and come to prize flavors that once seemed subdued, green, and savory. (Serving such a “tea,” really, would not be out of place at Smyth or Elizabeth—two restaurants that have only grown in stature as your tastes have developed).

Ultimately, the liquid strikes you today with a complexity that spans those same bitter, earthy, and vegetal notes but combines them with the requisite sweetness, fruitiness, and florality to be enjoyable. The sum total of these components amounts to a lasting, shapeshifting, delicately savory tea that leaves your mind spinning in its attempt to describe what flavors it senses. There’s a reductive yet connective element to the dish (as regards the larger meal) that is intellectually satisfying. And, while it could never be classified as hedonistic, the broth is absolutely singular in its character and is imbued with immense value as a relatively unfiltered expression of the kitchen’s sourcing practices.

The ”Tea of Lightly Smoked Fruits and Vegetables” has typically been paired with a cracker made from rugbrød—a Danish rye bread flecked with whole grains and other seeds. One rendition of this bite has been topped with radish slices while another featured a combination of shiitake mushrooms and marigold. The current version, titled “Pickled Cucumber with Buttermilk on Rugbrød” follows in a similar style: gossamer slices of vegetable are layered atop a thin crisp of the dark bread to make for a fleeting, distinctly fresh morsel.

Eaten on the back of the transfixing tea, the rugbrød serves to reorient your palate. The cracker’s rye base complements the smoky, earthy notes of the steeped produce beautifully. Its topping of cucumbers, though nominally pickled, are crisp, clean, and refreshing. They work to override the stewed notes of the tea and reset the palate for the other fare to come. Ultimately, it is the schmear of tangy buttermilk (used to anchor the cucumber to the cracker) that serves to emphasize the dish’s “pickled” quality. Still, its effect is subtle, and the bite succeeds by enveloping the palate with robust flavors that extend—then wash away—the lingering effect of the preceding broth.

The duo, while not offering much obvious pleasure, is always distinctive and continues to grow with each iteration. (The newest, late-July rendition of the rugbrød, titled “Gunde’s Cucumber Salad on Crisp Rye Bread,” is particularly delicious thanks to the addition of a thin slice of pork belly). However, no matter which exact form they take, the two opening dishes serve as an introduction to the Elske culinary aesthetic, working to establish a baseline—built on a particular grammar of flavor composition and palette of favored ingredients—that will help carry the diner’s palate throughout the rest of the meal.

Courses three and four of Elske’s “Set Menu” also arrive as a pair. Currently, they comprise bites titled “Cured Fluke with Fried Potato” and “Duck Liver Tart with Buckwheat and Pickled Ramps.”

The former of these is a new construction that sees a thin slice of lightly cooked fluke wrapped around a cylindrical potato crisp affixed to the plate with a dab of crème fraîche. The “chip” is rather delicate, yet it holds its structure well as you pop the morsel into your mouth. There, it cleanly shatters and crunches between your teeth as some of the residual crème fraîche serves to hold the fragments together. This proves a fitting canvas for the fluke itself, whose flesh—once it reaches the tongue—is smooth and sweet. The bite impresses with its subtlety and disappears without any trace of “chew.” It ranks, you think, as the most elegant of Elske’s current roster of amuse-bouches.

The latter member of this duo—“Duck Liver Tart with Buckwheat and Pickled Ramps”—is just about as totemic as the restaurant’s fruit and vegetable “tea.” The dish may not comprise the totality of the menu’s produce—and Danes themselves may agitate to have foie gras production banned throughout Europe—but it has been served from Elske’s very beginning and cuts a striking figure on the table. The tart, made from bricks of buckwheat dough, also represents—you believe—a collaboration between David and Anna: treading the line between savory decadence and pastry precision.

In the past, the tart’s crust has displayed a slightly finer grain that helped provide ample structure for slices that were provocatively slender and pointed. These days, the crust is attractively rough and crumbled. It forms the base for slices that are about 50% wider and a wee bit shorter than before, and you must say that you prefer this new form. The duck liver mousse has remained consistent, being unabashedly savory and unadorned by the kinds of sweet notes many chefs use to buttress the flavor of foie gras. The tart’s gorgeous green topping is drawn from powdered pickled ramps, an ingredient that shows some clear relation to the “salted ramps” and “parsley powder” that have been used in the past.

Historically, you have found Elske’s “Duck Liver Tart” to taste a bit subdued when compared to more hedonistic preparations of the totemic luxury ingredient. The dish does not flatter the palate with syrupy expressions of berry or maple. The crust does not resound with notes of brown sugar. Rather, the flavor of the foie gras speaks clearly with an unapologetic meatiness and depth driven further by the earthy buckwheat and pungent ramp. This tart has taken some time to grow on you, yet it offers an unadulterated expression of duck liver that tastes more and more appealing on each occasion you encounter it. The dish affirms the Poseys’ unique style of cookery and finds few peers—even within the rarified realm of foie gras cookery—throughout the city.

Moving over to the à la carte section for a moment, there are three opening dishes—separated by a small gap in the menu—that may be called appetizers.

The “Publican Quality Oat Porridge Sourdough and Cultured Koji Butter” ($10) represents a tip of the ballcap from the Poseys to their friends and colleagues at One Off. That relationship has secured them access to some of the very best bread in town—courtesy of 2019 James Beard “Outstanding Baker” Greg Wade.

While Elske has previously made use of Publican Quality Bread’s “Dark Rye” loaf, the switch to the “Honey Oat Porridge” (made with Ackerman Farm oats from Illinois and Kallas honey from Wisconsin) has been a good one. The latter possesses a slightly lighter character with a hint of sweetness that provides a reprieve from the robust flavors of the savory food. The accompanying butter, made from dairy sourced from Kilgus Farmstead, is rich and creamy with a transfixing tangy-nutty finish from the kōji (a mold that grows on rice grains, forming sugars that play an essential role in fermenting both sake and miso). It glides effortlessly across the warm, crusty bread, enriching its latent flavor. Though Anna has also crafted excellent Parker House rolls as part of Elske’s “Set Menu,” this à la carte bread service forms an essential accompaniment to any meal. It is hard to resist a second helping.

The next of the appetizers forms something of an introductory cheese course. “Aged Gouda with Honey, Strawberry, and Crackers” ($15) has been on the menu, in one form or another, for at least a few years. The dish has previously been billed as “Wilde Weide Aged Gouda” or “L’Amuse Aged Gouda” but currently carries no designation as to the cheese’s exact sourcing. Likewise, the accompaniments have included apple jam and cherry over time, yet the style of cracker has remained a persistent element.

No matter the exact style of gouda—or the chosen fruit—Elske’s cheese plate is excellent. It starts with the crackers: thin, flaky numbers with a couple air bubbles across their surface. They blanket the slices of cheese in an alternating fashion, just about matching them for size and thickness. For the price, you get about ten of these paired bites, which you can then top with a bit of the strawberry (rendered as a syrup) or a gushing cell of the honeycomb. Either option underscores the gouda’s rich butterscotch notes while enlivening it (in the fruit’s case) with a burst of acid. The drying cracker helps moderate the accompaniments’ sweetness and marry the three elements together, yielding a starting complexity given the simplicity of the construction. The result is as close to a perfect bite of cheese as can be found in Chicago. You credit this dish for first enamoring you with gouda, and it will invariably find its way onto your table as long as Elske continues to offer it.

The last of the à la carte appetizers is something like another bread service. However, rather than being paired with a fine cultured butter, four slices of grilled sourdough (Publican Quality Bread’s “Spence Sourdough” you believe) are served alongside “Salt-Cured Anchovies” ($15). The five fillets sit in a pool of olive oil at the center of a small plate and are topped with a dusting of fennel powder along with some slices of lemon.

To construct a complete bite, you coat the surface of the bread in the olive oil (picking up some of trace amounts of the pollen). You deposit one or two of the fillets across the sourdough and position the lemon segments (which notably include parts of the pith and peel) over the fish. The resulting sensation is crunchy, charred, briny, citric, and bitter in turn with a sweet, anisey finish and absolutely no trace of fishiness. As with the cheese plate, the degree of balance and complexity David is able to conjure from such a deceptively simple form is stupefying.

However, you think this dish only falls a little short due to the thickness of the bread. Even if you top it with two of the anchovy fillets, the crunch and substance of the toast overwhelms the fish just a bit. Nonetheless, you will never fault a generous serving of bread (and perhaps erred a bit in not breaking your slice in two or folding it to form more of a sandwich). Still, cutting the bread more thinly or, otherwise, opting for a slightly softer, crustless vessel could serve to showcase the anchovies more effectively.

Before returning to the “Set Menu,” you will note a couple more à la carte dishes that rank among the restaurant’s lightest dishes. First, there is the “Belgian Endive with Sherry Dressing, Pickled Raisins, and Walnuts” ($21), a preparation that Elske has offered since (at least) January of 2020. That is for good reason.

The plate arrives with the titular leaves of lettuce neatly arranged in a phalanx. The endives totally obscure the rest of the salad’s ingredients and make the presentation seem quite plain. (This deviousness ties back, in some sense, to the manner in which the restaurant’s menu is carefully hidden under your napkin). However, as you breach the wall of bitter greens with fork and knife, a well-dressed assemblage of shredded lettuce, raisins, and walnuts reveals itself.

Diving in, the larger leaves of endive provide a crisp, clean snap. They serve to corral the smaller components that lie within—and which resonate with a hearty, highly pleasing crunch. The raisins, with their hallmark chew, demonstrate a bit more staying power on the palate, yet the pickling process serves to rehydrate and soften them slightly. With regard to flavor, the endives’ cleansing entry yields to a tinge of bitterness, the tang of the sherry dressing, the sweet-sour pickled raisins, and the earthy, slightly bitter walnuts. All of the four elements blend seamlessly together, displaying harmonizing notes that remain anchored to (and balanced by) their distinct characters. The salad’s overall sensation is one of mouthwatering, lip-smacking goodness. It stands as one of Chicago’s very best representations of the form, and a dish that the restaurant may very well struggle to ever replace. Bravo!

Nonetheless, the newest of Elske’s salads might very well give the endives a run for their money. The “Heirloom Tomatoes with Stracciatella, Cherries, Smoked Paprika, and Herbs” ($26) only came onto the menu a week or two ago. And you think the dish already lives up to the high standard set by Rose Mary’s “Stracciatella” ($21)—served, at the moment, with Klug cherries, pine nuts, fennel pollen, and lepinja.

Both preparations are dominated by the “rags” of shredded mozzarella curds—mixed with heavy cream—that coat the plate. Yet it is worth noting that the stracciatella actually receives second billing in Elske’s case. The stars of David’s dish are actually the halved, golden orange heirloom tomatoes that top the cheese. They come raw, roasted, and pickled and are joined by pieces of cherry (whose reddish hue blends perfectly into the composition), as well as bits of leaves and buds that sit within the ingredients’ crevices.

The construction of the dish seems effortless, as if the chef simply tossed a few ingredients together. But the tomatoes and cherries are impeccable, offering a gushing mouthfeel that is backed up by refreshing acidity and a concentrated fruitiness. The stracciatella, by coating and enriching its accompaniments, enhances the textural sensation of the produce. Its latent sour notes also balance the cherry’s tinge of sweetness and reveal—alongside the herbs—a deep, savory character to the heirloom tomatoes. The whole preparation, owing to the multidimensional way in which the star element is treated, is pleasantly chunky and hearty but undeniably fresh. It forms a dream pairing with the aforementioned “Oat Porridge Sourdough” yet can just as easily stand on its own. That is because the dish treats its core ingredients reverently, and they measure up to that honor through the degree of multifaceted flavor and texture they offer. Well done!

Moving back to the “Set Menu,” one of its newest offerings (as of a week ago) almost seems to imitate the “Heirloom Tomatoes with Stracciatella” at a structural level. The dish is titled “Roasted Celtuce with Trout Roe, Ricotta, Red Currants, and Sorrel” and, once more, sees an intriguing juxtaposition of produce play out across a schmear of rich cheese.

The star of the preparation is celtuce (also known as stem lettuce), a cultivar grown less for its leaves and more for the crisp, green stalk that is typically stir-fried in Sichuan cuisine. This part of the vegetable, which also resembles a wasabi root, is peeled down to its heart and then shaved into a long rectangular strips. These pieces are roasted, and one (per plate) is positioned across a mound of cold, firm ricotta. That gets garnished with the trout roe and redcurrants; some matchsticks made from fresh celtuce; and a crowning leaf of sorrel that serves to obscure all the rest.

Diving in, you like the way the sorrel has already been segmented to help guide your knife down to the plate. This allows you to strike straight at the strip of roasted celtuce, cut off a piece, and pluck a cohesive bite that comes coated with the cheese, roe, red currant, and a couple matchsticks of the fresh stem. The resulting texture is creamy on entry but follows with a faint snap, a smooth interior, an array of bursting orbs, and a crunchy, leafy finish.

In terms of flavor, the roasted celtuce displays an attractive nutty quality that melds well with the faintly sweet ricotta and the deep-sea quality of the trout roe. Balancing notes come by way of the tart-sweet red currant and the tart-fruity sorrel, which also play into the tangy notes of the cheese. The fresh celtuce, meanwhile, offers a cleansing sensation that’s close to cucumber. The dish sounds like it has too much going on—blending textures and flavors of fruit, herb, fish, cheese, and root vegetable together. But the preparation eats like a refreshing salad and leaves you appreciating the nuances each of the components draws from the others. The plate is both bold in its composition and successful in its execution. You cannot say you have ever seen or tasted anything like it.

The next à la carte dish—“White Asparagus with Rullepølse, Remoulade, and Stout Jelly” ($26)—sounded great on paper. The dish, which has now left the menu, comprised that favorite spring vegetable which had been gently cooked, wrapped in a crêpe, and draped with several slices of cured pork belly (rullepølse). The meat, as with several of the restaurant’s preparations, served to obscure the plate’s other elements: the Danish-style remoulade (typically made from mayonnaise, yogurt, mustard, pickles, and shallots) and cubes of stout jelly. The whole preparation seemed to reference the Danish smørrebrød—an open-faced sandwich (made from the previously mentioned rugbrød) that can be topped with countless garnishes but frequently features rullepølse and sky (the Danish term for an aspic).

You attacked the dish expecting a delicate stuffed crêpe enriched by luscious accompaniments. However, in practice, the preparation struck you more as a disparate assortment of cold bites. The rullepølse, while appealing when plucked and deposited straight into your mouth, needed to be cut apart in order to navigate the plate. After doing so, you were able to segment the crêpe, including the two stalks of asparagus within, and drag it through the remoulade. These smooth textures melded well together and offered flavors that were slightly sweet, sour, and tangy with an earthy, malty undercurrent drawn from the crêpe’s rye base. It’s easy to see how the stout jellies might play off of those latter notes, but you struggled to include them—along with the sliced strands of the pork belly—into one cohesive bite.

Admittedly, you shared the dish with one other person and might have made a mess of it structurally. Likewise, your unfamiliarity with the smørrebrød form and errant expectations regarding the asparagus’ degree of decadence could have compromised your enjoyment. That being said, you finished the plate and find the construction—as you describe and contextualize it now—stimulating. It speaks to a strong piece of Danish culinary identity and demonstrates the Poseys’ mastery of a range of native techniques. Your experience was confusing but in no way “bad,” and you would relish the chance to give the dish another try with some firmer direction on how to properly appreciate it. The item stands, perhaps, as one preparation whose fidelity to its form and inspiration presents too much of a challenge at the moment.

Elske’s “Charred Leeks Vinaigrette with Clothbound Cheddar, Toasted Oats, and Black Olives” ($24), on the other hand, is more successful. And, once more, there’s something of a visual trick at play. The charred leeks stand upright at the center of the plate, being surrounded by a scattering of the oats and olives. However, the alliums are coated in a frothy cream made from the famous Jasper Hill Farm cheese that envelops the vegetables and hides them under what appears—at first glance—to be a molten mound of cheddar. A few streaks of bright green oil (the vinaigrette) complete the presentation.

Diving in, you are impressed by just how ethereal the cheese element is. Though sticking and running down the sides of the alliums, the cheddar yields to your fork as it strikes and scoops one of the vegetables out from under its stream. The accompanying spoon helps to retrieve some of the bits of oat and olive, which dutifully affix themselves to the leek. When you take a bite, you are impressed by the vegetable’s smooth, soft texture with only the slightest element of crispness on the finish. The allium’s layers fold nicely into the frothy cheese, which serves to enrich the mouthfeel and buffer the crunch of the accompanying bits.

As to flavor, the dish takes the mild sweetness of the leeks and complicates it with a touch of bitterness (from the char), tangy-caramel notes from the cheddar, some zing from the vinaigrette, rich nuttiness from the oats, and a cleansing fruitiness from the olives. The overall sensation is one of immense textural decadence leavened by a vibrant—yet still decidedly savory—tapestry of ingredients. The Clothbound Cheddar, though it visually dominates the plate, is transformed masterfully into a refined, understated canvas for the plate’s other constituents. This is a delightful take on a classic recipe that travels in a totally singular direction.

Returning now to the “Set Menu,” its four opening bites are followed by the first composed plate: “Smoked Fjord Trout with Roe and Spiced Carrot, Sunflower Seeds, and Garlic.” The preparation arrives boasting—as with so many of the Poseys’ dishes—a beautiful presentation. A crown of carrot slices, topped with orbs of the roe, encircle a pool of carrot emulsion. Beneath the slices (and obscured) lie small chunks of the smoked trout that are interlaced with the sunflower seeds. Other than a garnish of microgreens, the plate’s overall design offers an enticing, painterly study in orange.

It tastes good too. The crisp snap of the carrot slices, pop of the roe, crunch of the sunflower seed, and smooth, slick texture of the trout itself contrast nicely. But it’s the creamy emulsion—tinged with garlic—that serves to bring the elements together. As these components combine, the nutty-sweet flavor of the fish is underscored by the seeds and the saline quality of its roe. The raw carrots impart a mild sweetness too, yet they principally serve to balance the trout’s touch of smoke and maintain a sense of freshness. The emulsion, meanwhile, blankets everything with a more pronounced, savory expression of the vegetable. The ”Smoked Fjord Trout” forms a fine start to the “Set Menu” and affirms the restaurant’s eye for colorful, captivating compositions.

Back in the à la carte section, you find a favorite seasonal item: “Fried Soft Shell Crab with Green Asparagus, Hazelnuts, and Sea Beans” ($30). And, once more, the dish displays an artful design. The whole crustacean is bisected and positioned so that the stalks of asparagus—strewn with sea beans—jut out from its carapace. The scene resembles the shallow grass beds of the Chesapeake Bay in which the crabs shed their exoskeletons: an incredibly clever inspiration that, functionally, works well too.

Texturally, the crab’s batter demonstrates a light touch. You can still make out the shell’s color—typically entombed under a layer of golden-brown crust—yet it still displays the kind of crisp, clean crunch all such preparations should aspire to. That consistency matches the hazelnuts and melds well with the subtler chew of the asparagus and sea beans. There’s also a drizzle of what you think to be mayonnaise blanketing the vegetables, which serves to enrich the overall mouthfeel a bit. In terms of flavor, the dish balances the sweet, rich crab with the toasted notes of the hazelnuts and the salty, grassy notes from the asparagus and sea beans. You like the restraint shown here, one that ensures the crustacean—prepared better than any other soft shell in the city you can think of—truly shines.

One of the newest à la carte dishes, launched just this past week, represents the evolution of a preparation that had featured for several months prior (but that you had neglected to try). The “Confit Maitake with Fava Beans, Creamed Barley, and Garlic Scapes” ($27) has made way for “Confit Maitake with Cornbread Polenta, Lovage, and Pecorino” ($27), and you find it hard to imagine that the prior version could have possibly been better.

The bowl comprises a cluster of the maitake (also called hen-of-the-woods) caps that have been confited to a beautiful dark brown color and almost crunchy texture. The mushrooms sit upright in a pool of polenta that has been dusted with cornmeal, studded with corn kernels, and topped with segments of the lovage’s stalk. Diving in, each scoop imparts a mouthfeel that is smooth and rich then firm and finely crunchy. The polenta not only displays an expert texture—neither too firm nor too runny—but possesses a trace of sweetness that is further invigorated by the fresh corn and tangy Pecorino. The lovage, too, joins these elements with hints of parsley, celery, and anise.

But everything serves to counteract the powerfully meaty quality of the maitake, which delivers a degree of savory pleasure and robust mouthfeel that would have you forget this is even a vegetarian dish. What a nice example of homey, hedonistic cooking—sans meat. The polenta utterly outshines the kind that finds its way beneath many an osso buco throughout the city.

Shifting to the “Set Menu” once more, the lightly smoked trout is followed by “Steamed Halibut with Mussels, Kohlrabi, and Chamomile.” Visually, this plate is more of a “study in white” than its predecessor—save for the pale orange of the bivalves placed across the surface of the fish. The ingredients, nonetheless, are arranged in a more conventional fashion, channeling attention towards the glistening fillet.

The halibut, owing to its gentle steaming, effortlessly breaks apart into large flakes that display a supreme juiciness. The mussels, sliced into thin strips, lack any of their usual chew and do well to match the fish’s smooth mouthfeel. Fanned across the plate in a set of five, the kohlrabi might offer the dish’s most substantial texture. (But, likewise, the brassica is cooked expertly so that it offers only a slight crispness that yields to a soft interior). Whereas the fish itself displays a mild, sweet flavor, it benefits from a buttery chamomile sauce spooned on top that enhances the sweetness and offers a floral dimension to boot. The mussels, you must admit, get a bit lost in the shuffle, but the sweet-peppery kohlrabi is quite nice. While perhaps a bit simpler than Elske’s other dishes, the “Steamed Halibut” preparation is carried by the expert cook on the fish and its elegant, flavorful sauce.

Only recently, the “Steamed Halibut” has made way for a new rendition of the fish: “Confit Halibut with Green Tomato, Aji Blanco, and Almond.” Instead of the former preparation’s subdued white tones, this new dish pops with an appealing pale green color. That is drawn, of course, from the tomatoes, whose slices (in the familiar Elske style) serve to obscure the portion of fish.