On the back of your venomous preview of Boka Restaurant Group’s forthcoming Alla Vita venture, you thought it would prove instructive to delve more deeply into the Italian genre. While you lust for restaurants such as Carbone, Marea, and Vetri Cucina out east, the Windy City stands as a fitting microcosm of the many gradations between “Italian” and “Italian-American” cuisine.

Red sauce “joints” have formed part of Chicago’s cultural fabric since as early as 1893, when Lucca native Carmelinda Galli opened Madame Galli’s at 18 East Illinois Street. The restaurant developed naturally out of the boarding house she ran in what was then considered a “near north side art colony.” There, Galli typically prepared spaghetti for the “poor starving artists and writers” who rented her rooms.

When a troupe of actors from abroad threatened to leave Chicago unless they could find a satisfactory spaghetti restaurant, one of their stagehands—who also happened to be boarding at Galli’s house—recommended they pay Carmelinda a visit. The performers’ patronage secured the chef’s reputation, and she soon installed the additional tables that transformed the hostel into a bonafide restaurant.

Decades later, 1914 saw the opening of “Big Jim” Colosimo’s namesake restaurant, which touted “one million five hundred thousand yards of spaghetti always on hand.” “Big Jim,” if the nickname didn’t clue you in, was also a founding member of the Chicago Outfit. In 1920, he was gunned down in his restaurant’s lobby—but “despite this (or maybe even because of this), Colosimo’s thrived long afterward.” The establishment would become “a favorite stop for tourists at the 1933 World’s Fair eager to experience a touch of Chicago’s gang culture” (Block and Rosing 176).

And perhaps that dichotomy—between Madame Galli’s humble boarding house fare and “Big Jim’s” sense of grandeur—encapsulates the key tension. Though “Italian cuisine” ranks as the world’s most popular—edging out Chinese, Japanese, French, and Spanish food—it comprises at least two distinct traditions. There exists the “real,” “authentic” cookery of the old country: “slow food” marked by simplicity and seasonality. And there also exists the Frankenstein version: diaspora cuisine shaped by Italian immigrants’ assimilation into American culture, their grappling with a never-before-seen abundance and the predilections of native tastes.

The “garlic eaters” who carved a place for themselves in early 20th century New York and Chicago developed their own distinct canon. They popularized the “chicken parm,” the “side of pasta,” mountainous meatballs, Caesar salads, and the “hero sandwich.” They brought the Neapolitan pizza to its apotheosis: a plethora of forms and toppings that stands as a shining example of why bowing before “authenticity” inhibits the development of even greater pleasure.

This article, however, will not concern pizza, for that world-renowned form has already provided endless fodder for every garden variety foodie influencer and craven content creator. Rather, you concern yourself with the “Italian restaurant” as a structural form that comprises appetizers, pastas, entrées, and dessert. Such establishments may indeed offer pizza, but it is not their specialty.

(In the same vein, some pizzerias may offer other “Italian” fare, but moreso as a token offering. There are some high-quality exceptions, but you would still classify such establishments primarily as “pizzerias” rather than “osterias,” “trattorias,” or “ristorantes” that focus on composed plates).

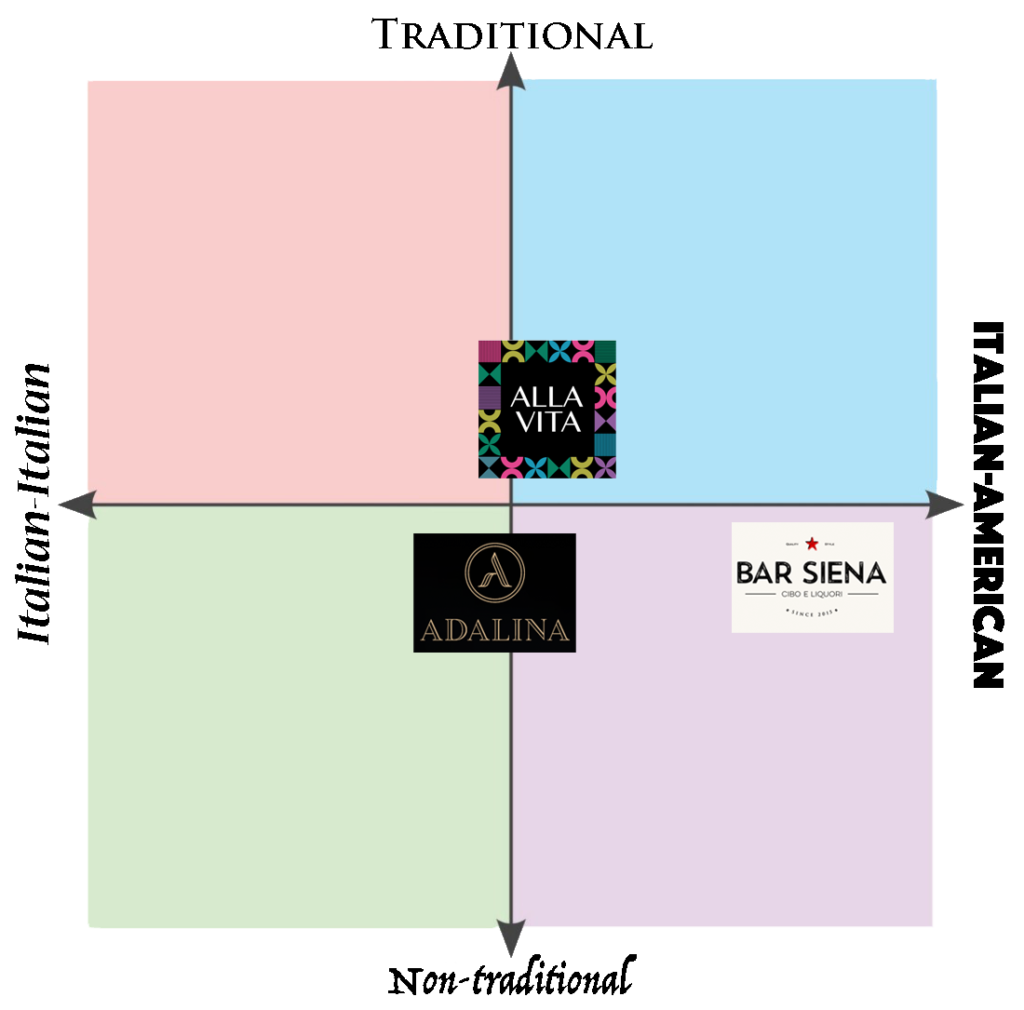

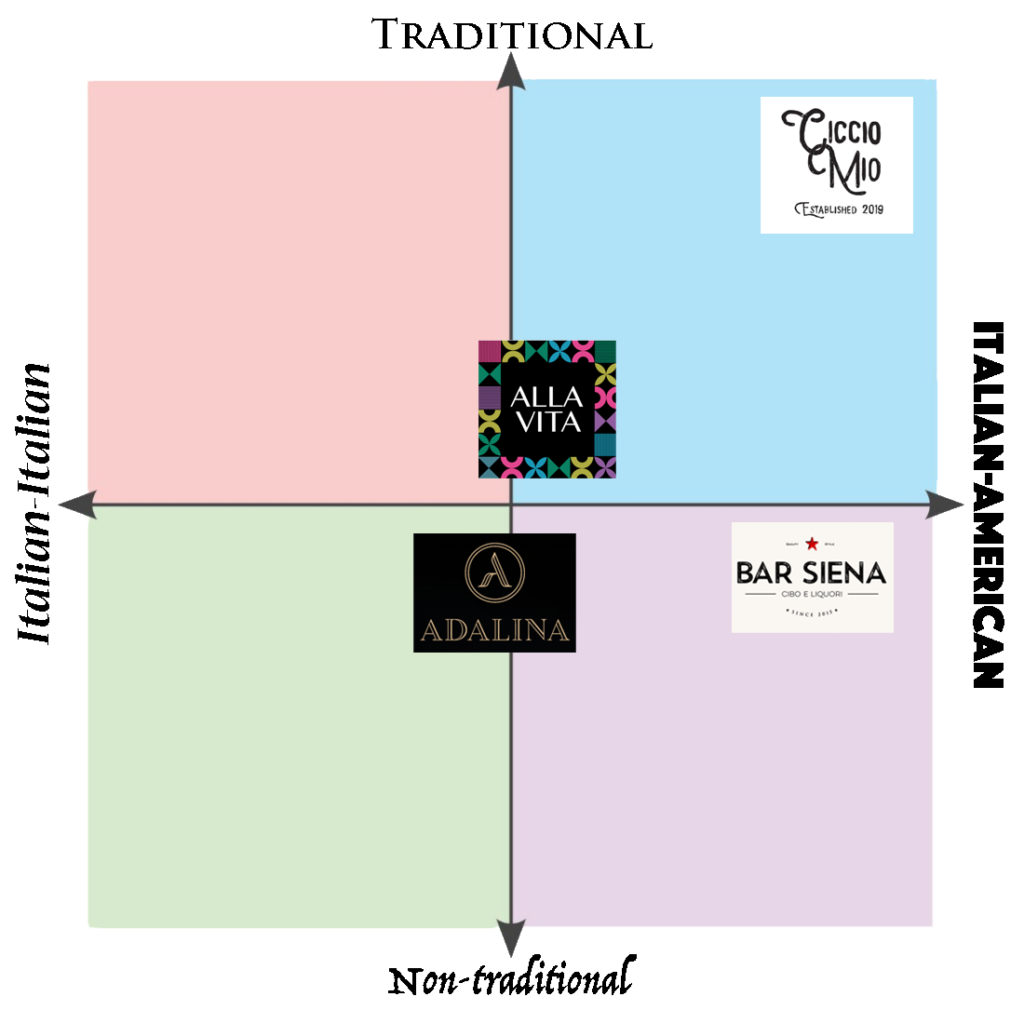

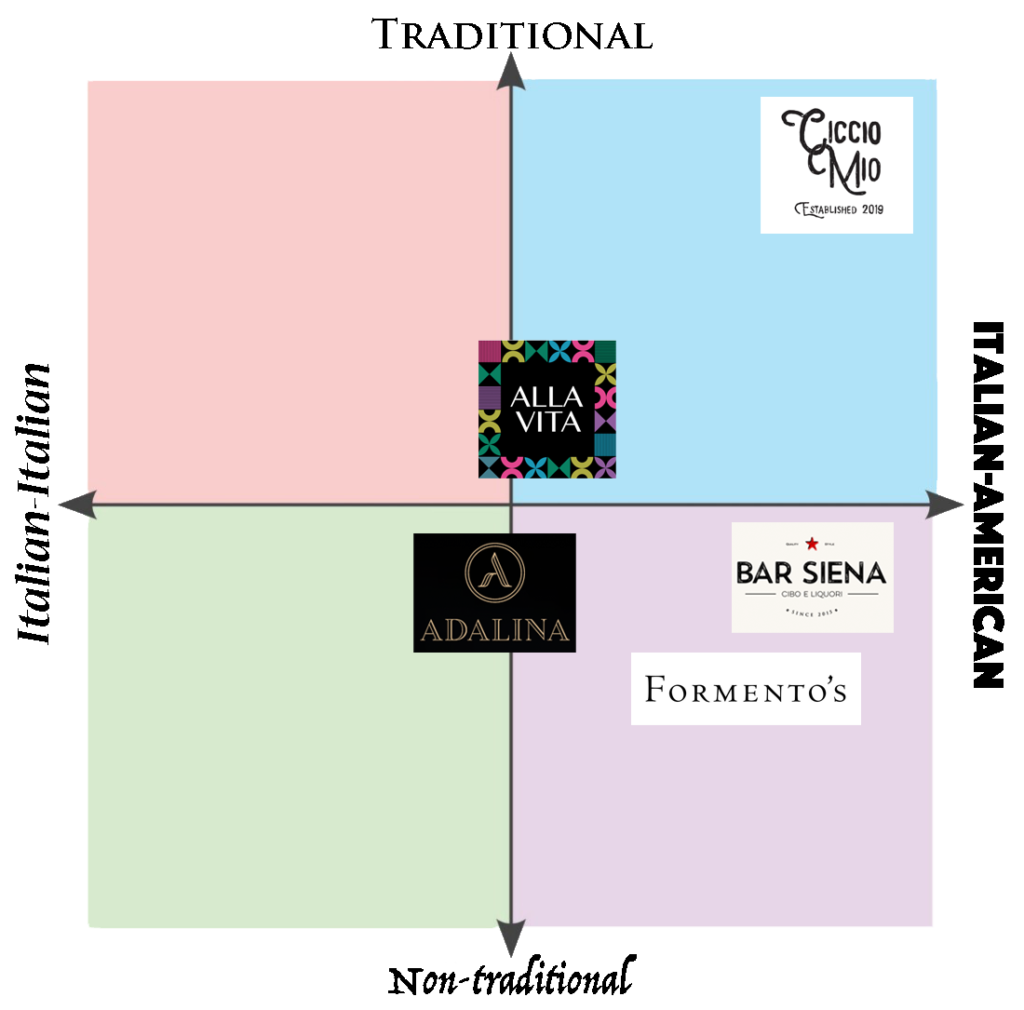

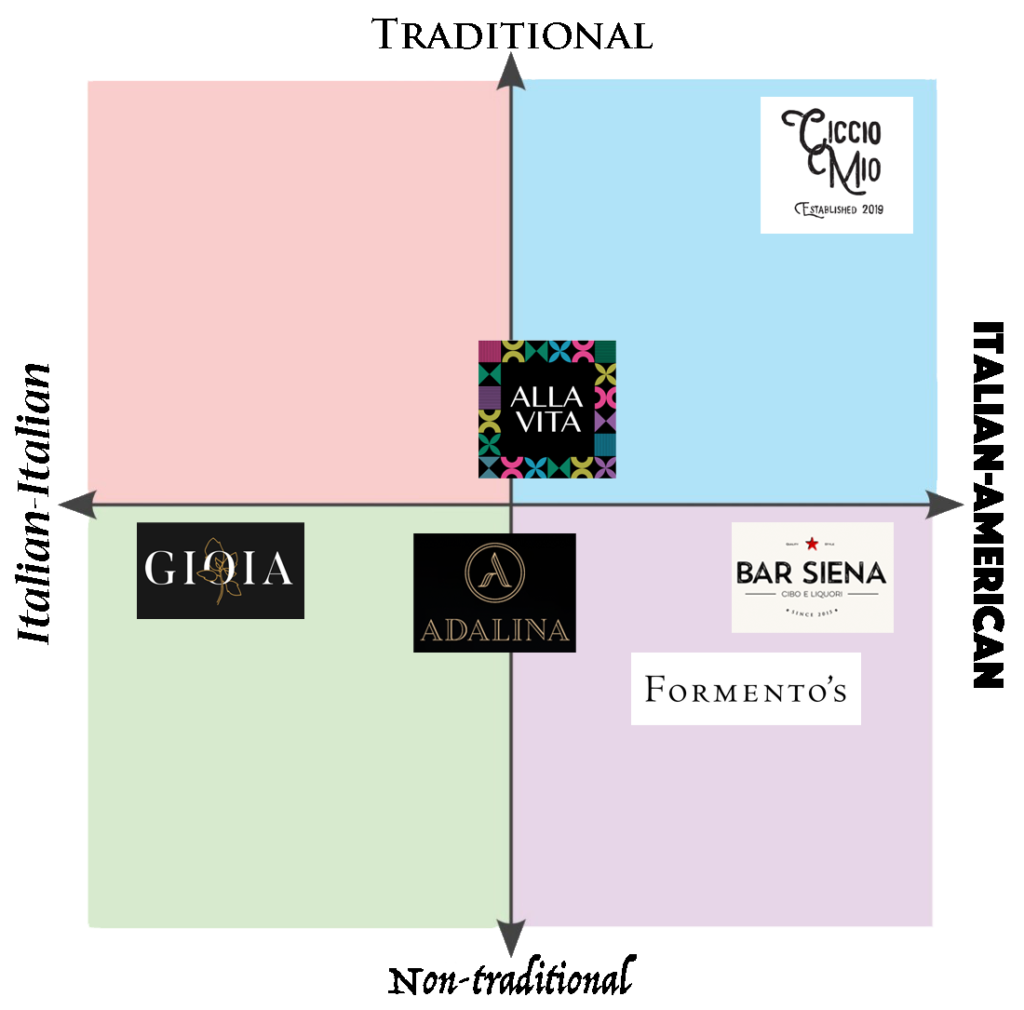

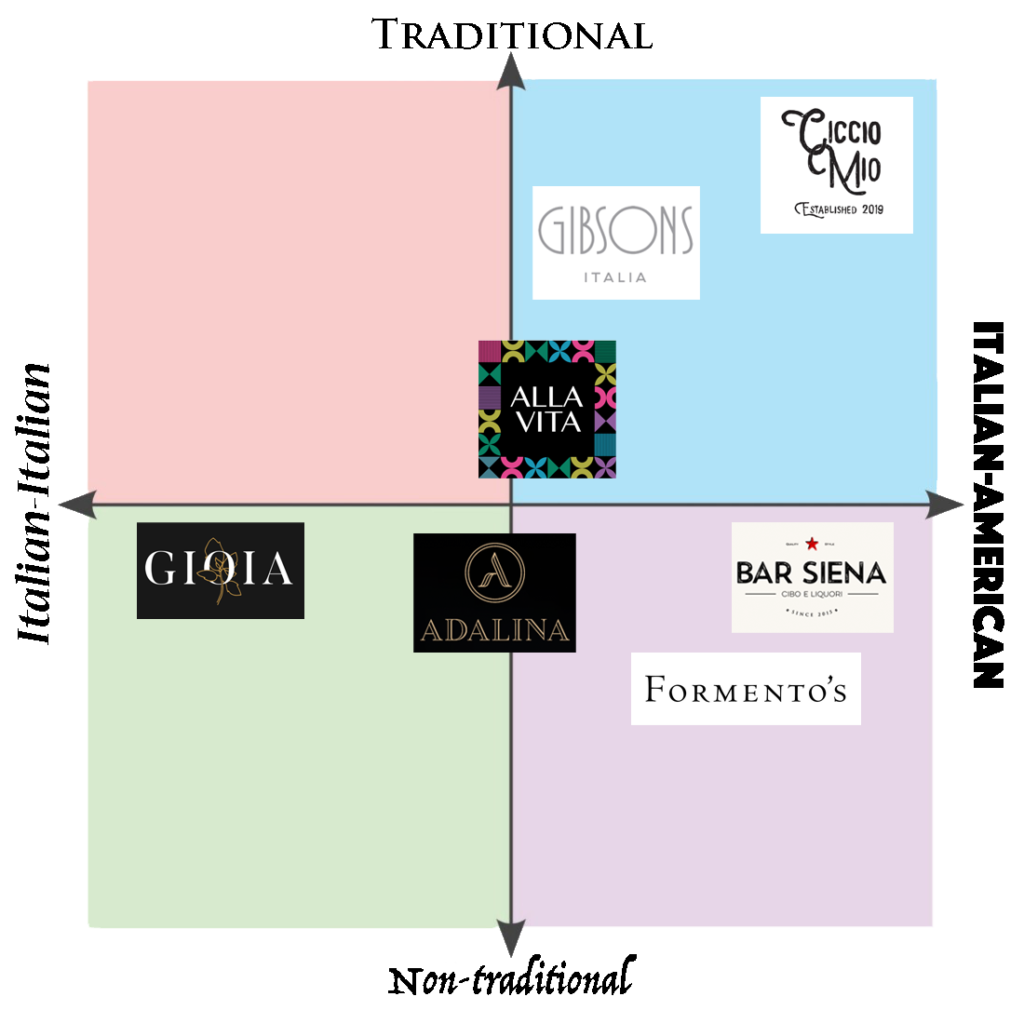

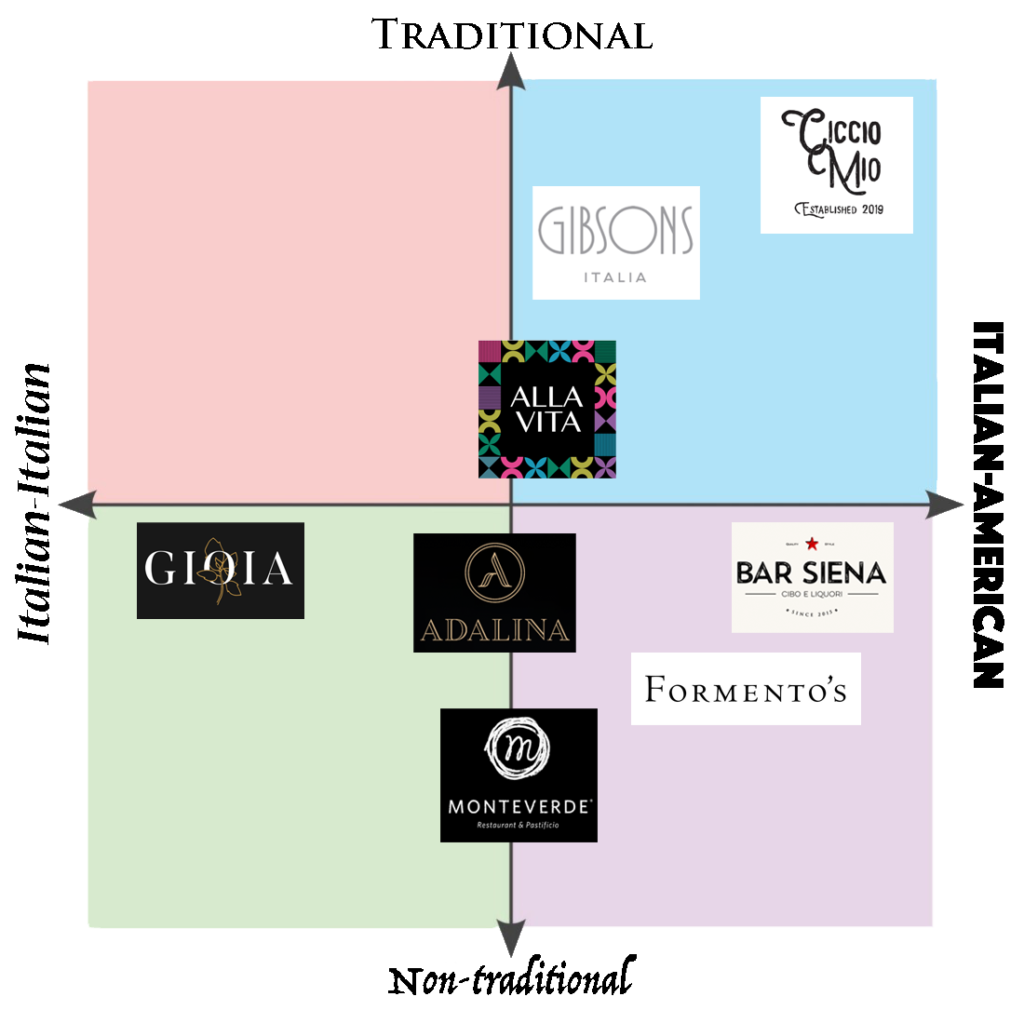

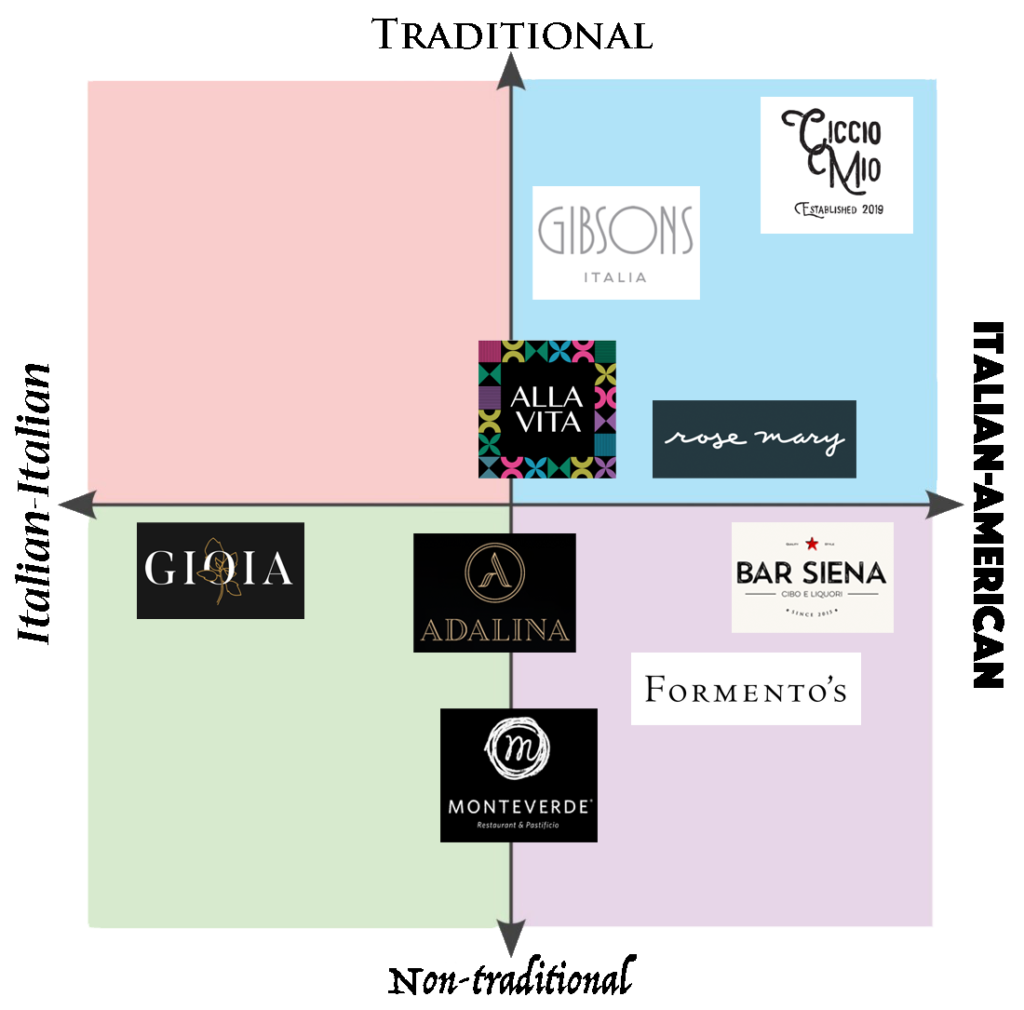

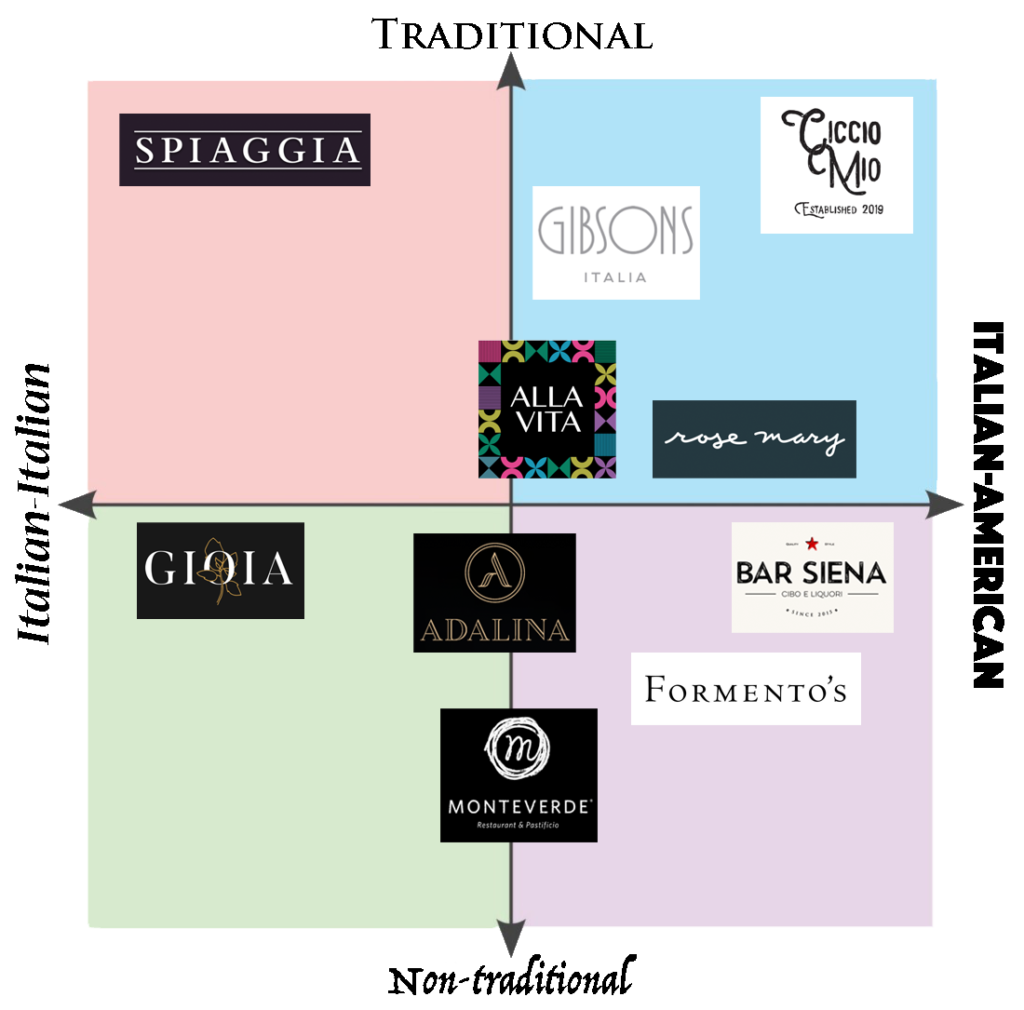

With that in mind, you will survey some of Chicago’s shining examples of Italian cuisine and situate them on a scale that distinguishes “Italian” versus “Italian-American” character and the degree of faithfulness with which each restaurant approaches the respective canon. Some examples will surely occupy a liminal space between these four poles—a reality that makes such a triangulation all the more rewarding.

As Italian-Americans increasingly see themselves absorbed into the contemporary, reductive paradigm of “whiteness”—and as American consumers themselves come to know how Italy’s own cooking diverges from that which has been popularized on their continent—the survival of the red sauce “joint” remains an open question.

How do notions of “abbondanza” figure into a culture less engaged with the kind of backbreaking physical labor that originally necessitated such heaping portions? Does the restraint shown within the “proper” Italian tradition not provide an appealing—if only partial—solution to this nation’s growing obesity epidemic?

But what do we stand to lose by turning away from that hyphenated American tradition? Can some essence of the past century’s “Italian-American” nostalgia not be rescued, refined, and preserved? Does such an offshoot tradition still hold any value now that the conditions that conjured it into existence have come and gone? Or will that pigheaded pursuit of “authenticity,” once more, stifle creativity and make the world of culture just a bit less diverse and beautiful.

You will seek to untangle some of these questions as you establish the lay of land for Chicago’s saturated—yet surprisingly distinct and characterful—Italian dining scene. With more and more restaurants embracing the world’s most popular culinary genre, it pays to know just which vision of “Italy” one will be exploring in a given dining room.

With that being said, let us begin.

Adalina

Proceeding alphabetically means that you must engage with two of Chicago’s forthcoming Italian restaurants first. Thankfully, Adalina—a glitzy Gold Coast venture from a former Gibsons partner that touts Soo Ahn, who earned a Michelin star at Band of Bohemia, as its chef—has already revealed its menu.

The bill of fare’s categories certainly embrace an “Italian-Italian” aesthetic: there’s “Piattani” (a misspelling, you think, of piattini, the term for small plates), “Crostacei” (crustaceans), “Foglie” (literally, leaves—a reference to salads), “Terra” (earth), “Mare” (sea), and “Goomara” (a slang word for “mistress” that forms a hilarious moniker for side dishes). But there are also categories comprising “handmade pasta” and items “carved tableside.”

The “Piattani” section is largely “Italian-Italian” in character: meatballs are labeled “polpettine,” a dish of burrata is served with “Sicilian caponata,” and “gnocco fritto” (a traditional Emilia-Romagna appetizer) is joined by San Daniele prosciutto, whipped ricotta, and Mieli Thun honey. However, a “cacio e pepe” arancini is distinguished by its use of Forbidden Rice and Manchego while a seemingly-traditional preparation of charred octopus with sunchokes, Sicilian pistachios, and fennel is accented with horseradish goat cheese.

The “Crostacei” section features an “Adalina’s Tower” of oysters, prawns, king crab, and Maine lobster that must seem familiar to anyone familiar with Chicago’s steakhouse tradition. And, while you are not sure that Italians gorge themselves on seafood in exactly the same manner, they surely enjoy the riches of the sea all the same. More interesting is the tower’s accompanying “cannoli”—a reference, you think, not to the famous dessert but, perhaps, to a savory cracker made from the same manner of shell. A dish of “Mussels au Gratin” also strikes you as interesting. While the dish reads as French, it combines the cheesy bivalves with fregola sarda (a Sardinian pasta), ‘nduja, heirloom tomatoes, and Tuscan bread—a supporting cast that smacks of Italy.

The “Foglie” section, however, veers more towards the “Italian-American” side of things. It is headlined by a “Truffled Caesar” that is prepared tableside. A “Summer Salad”—featuring kiwi, strawberry, and an elderflower vinaigrette—feels broadly seasonal (though Italians do enjoy elderflower liqueur). But the “Fried Green Tomato Caprese,” you must say, is quite captivating too: it represents a coming together of “Italian” and “American” culture that starts apart from the “Italian-American” tradition of limply recreating the salad with subpar domestic tomatoes.

The “Handmade Pastas” seem to be constructed in a fairly traditional manner. You see no sign of spaghetti and meatballs or other heaping bowls in the “Italian-American” tradition. Surely, richer offerings will come with the season, but the section—as it stands—is defined by a light touch. Only the “soubise” and “mornay” elements seen in a cannelloni preparation and the Gordal olives (from Spain) in a dish of agnolotti stick out as transcending the flavor palette of the “Old Country.”

“Terra” is defined by steak—which, like the seafood tower, seems to tip its cap towards Chicago’s Italian (American) steakhouse tradition. The “Veal Chop Parmigiana” certainly fits into that mold as well, but opting for a bone-in chop instead of a cutlet surely classes the dish up just a bit. A “Bavette Tagliata”—adorned with parmigiano and aged balsamic—places itself more in Italy, but dishes like lamb chops—with mint, pistachio, and sesame—and roasted chicken—with tomato mostarda and Dijon—occupy a liminal space between the two cuisines.

Under “Mare,” both the “Sea Scallop Vesuvio” and “Ora King Salmon” items gesture towards a modernized “Italian-American” manner of cookery. But the “Bistecca alla Fiorentina” and “Dover Sole” offered under the “Carved Tableside” section seemingly embrace a prototypically “Italian-Italian” form of simplicity. The “Goomara”—seasonal mushrooms, fingerling potatoes, asparagus, fried cauliflower, and charred rapini—resist easy categorization into either camp.

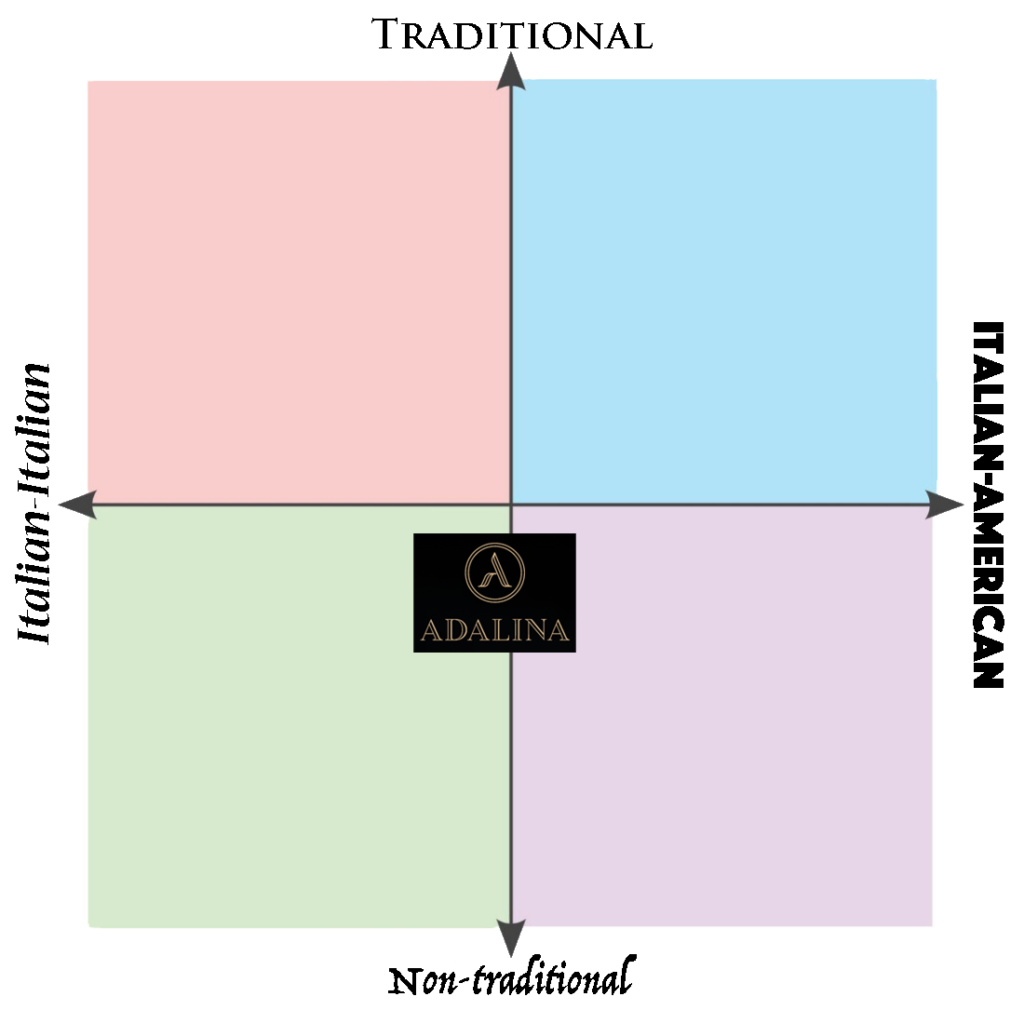

In the final analysis, you think Adalina taps into the grandeur of the “Italian (American) Steakhouse” tradition while fortifying it with “Italian-Italian” soul. Some offerings embrace domestic classics like Caesar salad and veal parm—but in a refined way. The menu is more largely defined by a European touch, but Soo Ahn carefully introduces some novel elements that provide—whether a given dish is “Italian” or “Italian-American”—a non-traditional, forward-thinking tinge to the fare.

Alla Vita

You will look to avoid retreading the ground you have only just covered in your article regarding Boka Restaurant Group—all the more because Boehm and Katz’s newest concept is still in utero.

However, BRG has revealed that their self-described “Italian-American” restaurant, whose name (“to life”) is a literal translation of a toast that does not exist in the Italian language, will be helmed by the Michelin-starred duo of Lee Wolen and Meg Galus. The former is the chef/partner and the latter the pastry chef of the group’s namesake mothership in Lincoln Park. Neither can claim a particular affinity for Alla Vita’s supposed cuisine, though Boka’s ricotta dumplings—a longstanding dish you would hardly call distinguished—is being touted as both a carryover and mark of Wolen’s affinity for the genre.

Surely, you do not need to be Italian to cook the cuisine—whether “authentic” or Americanized. You cannot ignore that brigades of Hispanic cooks have long contributed to the perpetuation of the tradition. And seeing chefs like Soo Ahn—or Jennifer Kim of the shuttered Passerotto—put their spin on another culture’s fare can be particularly rewarding.

But Wolen, as judged by his work at Boka, at Somerset (where he was recently replaced with Stephen Gillanders), and at his latest “Chicken Shop” concept, has a stunted vision of American cuisine. Adept at cranking out safe, bland food for Lincoln Park geriatrics, how can he hope to innovate within the realm of the world’s most popular category of comestibles? Well, at least they didn’t tap skewered steak and catering impresario Giuseppe Tentori to head Alla Vita—you’ll give them that!

“Bright, bold, and beautiful”—the favorite phrase of BRG that translates, as far as you can tell, to boring—has little to do with “Italian-American” cuisine as you know it. Yet Boehm and co. have branded their new space—rather presumptuously and arrogantly—as “the West Loop’s neighborhood Italian” and “a place to gather.” Alternatively, they refer to it as “casual Italian” and “an Italian eatery.”

Which makes you wonder, has BRG slyly stepped back from the original “neighborhood Italian-American restaurant” label shared with the press in early May and opted for a more overarching branding as “Italian”? Wolen described the concept as “for families…for tourism…for young adults and old adults. This restaurant is for everybody,” language that seems to tap into the cuisine’s wide popularity. “The goal is to have everybody come eat and not push anyone away by prices,” the executive chef also said.

Alla Vita’s menu, based on what has thus far been shared, comprises “five to seven pastas, selections like a vegetarian lasagna with wild mushrooms and ricotta; and a squid-ink pasta with spicy tomatoes, calamari, and Parmesan-garlic breadcrumbs” in addition to those dastardly “ricotta dumplings” brought over from the Boka mothership. Another source claims that guests “can expect a roster of classic, unfussy Italian-American dishes…[like] garlic knots and chicken parmesan.”

One of the more notable aspects is “the salad service, where servers will tote giant bowls of chopped salads that can be shared for groups as large as six.” And then there’s the pizza, which Wolen has recently teased on Instagram: medium-sized pies made in a Neo-Neapolitan style from the restaurant’s wood-burning oven.

A recent social media post also reveals an utterly stereotypical selection of antipasti like roasted garlic focaccia (with blossom honey), tuno [sic] crudo, fritto misto (with shrimp and calamari), wood fired meatballs, arancini (with n’duja aioli and fennel pollen), roasted octopus (with salsa verde), and burrata panzanella (with plums). You’ve tried to pick out some of the more interesting accompanying ingredients, but Wolen’s renditions—overall—do nothing to advance the genre. And, while these dishes are nominally “Italian-Italian,” they’ve been around in this form for so long as to become a part of the “Italian-American” canon.

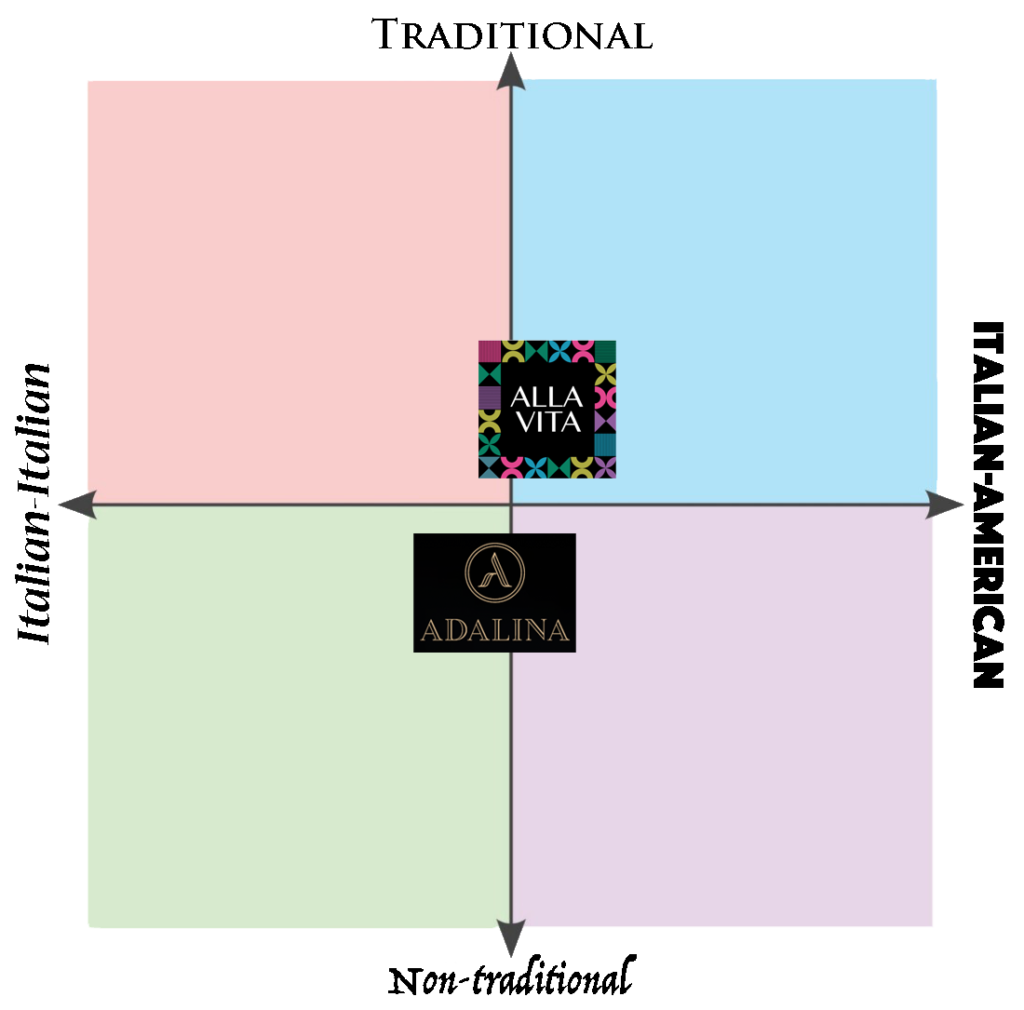

In the final analysis—though you only have scant details to go on—items like garlic knots, humongous chopped salads, and chicken parm surely place Alla Vita in the “Italian-American” category. The pastas mentioned do not seem quite as heaping as one would expect within the genre—there’s still no sign of spaghetti and meatballs—but touches like “Parmesan-garlic breadcrumbs” seem to pander towards an Americanized palate.

The pizzas, too, though not quite a benchmark of the old school “red sauce” joints, signal some divergence from the traditional Neapolitan style that has been so fetishized in America as to become—in your opinion—rather boring. Though Wolen makes use of the classic wood-burning oven, his crust is clearly a bit more airy and charred than is typically seen in Naples. The Neo-Neapolitan style—an application of “Italian-Italian” knowhow to domestic tastes and ingredients—reflects the new age of “Italian-American” cookery that breaks from the old canon but retains some of the spirit with which the original immigrants approached cooking upon arriving in America. You would expect the pizzas’ toppings to reflect fresh, locally-sourced ingredients—a touch that places Alla Vita, philosophically, towards the non-traditional side of the “Italian-American” scale.

Bar Siena

Fabio Viviani owned and operated a range of restaurants in his native Florence before moving to California at age 27. He won national attention—no doubt for his charming accent as much as his cuisine—while competing on the American edition of Top Chef in 2008. Though Viviani originally operated two restaurants out west, it must be said that the chef truly planted his flag in Chicago with the opening of Siena Tavern in 2013 and Bar Siena in 2015.

Though both restaurants took inspiration from a restaurant called La Taverna in—get this—Siena, Italy, the menus at Siena Tavern and Bar Siena reveal Viviani’s deep understanding of American tastes. Rather than demand that diners bow before some vision of “Italian-Italian” authenticity, the chef indulges his audience in a rather interesting blend of his native sensibility with some of the popular forms—and portion sizes—of his new home.

Ciccheti—a Venetian word for small snacks—are traditional enough: tuna carpaccio (with olive relish), octopus (with Calabrian chili vinaigrette), and burrata (with a spicy apricot mostarda). But when one approaches the antipasti, a distinct sense of flair emerges. Viviani satisfies his customers’ taste for stalwart items like meatballs, focaccia, and bruschetta but adds to the mix dishes like parmesan potato skins (with truffle garlic aioli) and parmesan crusted Parker House rolls (served with prosciutto, fontina, provolone, and honey). And, mind you, these are not lazy appropriations of American culture: you are comfortable declaring that Bar Siena’s parmesan potato skins are the crispiest, most delicious you have ever tasted. TGI Fridays eat your heart out.

Though presently absent from the menu—no doubt, a sad casualty of the pandemic—you must also single out Viviani’s embrace of the domestic barbecue tradition. His habanero-spiced Chicken Wings Diavolo—served with lemon caper ranch—and balsamic-glazed pork ribs (topped with crispy brussels sprout leaves) were proudly charred and unerringly tender each time you tried them. Moreover, they were lip-smackingly, aggressively flavored to such a degree that they even outdo Joe Flamm’s excellent Pork Ribs Pampanella at Rose Mary.

While Bar Siena’s pizzas embrace a more traditional Neapolitan style—as do dishes like gnocchi (with rapini), tagliatelle (with wild mushroom), bucatini cacio e pepe, and a half roasted chicken panzanella in a broader “Italian-Italian” sense—the menu is marked by further advancements of a new “Italian-American” canon.

Viviani serves a tomato bisque with a “petite grilled cheese.” He prepares a mac ‘n’ cheese with pancetta, braised leek, Calabrian chili, and parmesan cheese. Branzino—which forms a familiar presence within both genres of “Italian” restaurants—sees itself transformed into fish and chips, being served with “sticky” potatoes and a Meyer lemon aioli. Yes, there’s a rather traditional eggplant parmesan on offer. But the chef tackles his NY strip in a fairly restrained style—serving it in a simple “steak and (au gratin) potato” style.

The desserts, too, capture the blend of “authentically” Italian and forward-thinking “Italian-American” that defines Bar Siena’s menu. Bomboloni, gelato, and tiramisu stand alongside a “deconstructed” cannoli and, more notably, “The Cookie Jar”—a serving of caramel cookies to be dipped in a pot of Nutella mousse and hazelnut cream.

While Adalina and Alla Vita both offer some non-traditional twists on “Italian-American” food, Fabio Viviani has confidently formulated the next generation of the genre’s fare. For that hyphenated cuisine is not merely a mausoleum for dishes dated to the early 20th century. Rather, it enables chefs to embrace American abundance and nostalgia with an Italian zest. Though many sorry chefs trapped under the false paradigm of “authenticity” would view Viviani’s creations as a bit of pandering, the goofy Venetian cooks to please and deserves credit for pushing the boundaries of a distinctly “Italian-American” tradition forward like few modern figures have. Such is the freedom offered to any foreign chef who genuinely engages—rather than looks down upon—their new home’s culinary heritage.

Ciccio Mio

Oh, how long ago you wrote about Ciccio Mio. To be quite honest, despite your praise, you have rarely found yourself back at that establishment—pandemic or not. The menu, to your taste, hasn’t changed quite enough to whet your appetite. However, in the context of this particular article, that can hardly be called a bad thing.

Though Chicago still counts a roster of classic “Italian-American” restaurants—establishments such as Rosebud, Carmine’s, Volare, Topo Gigio, The Italian Village, and Gene & Georgetti—Ciccio Mio promises to preserve their traditional fare for a modern audience. The concept, which replaced Radio Anago—Hogsalt’s ham-fisted attempt at a Japanese lounge—possesses all of the timeless charm Brendan Sodikoff has become known for.

The bottles of amaro lining the walls of Ciccio Mio’s parlor, not to mention the plush, ample booth seating that defines the its dining room, is utterly romantic. The scene transports patrons to something like the platonic ideal of the “red sauce” style. It smacks of comfort and class to such an extent that one would not be surprised to spy a fedora-clad capo holding down a corner booth.

The aesthetic reminds you of New York City celebrity magnet Carbone—the king of kings (or capo di tutti capi, if you will) when it comes to “Italian-American” dining. Mario Carbone, who has held a Michelin star there since 2013 and subsequently opened offshoots in Las Vegas and Miami, is without question the cuisine’s strongest champion. He and partner Rich Torrisi—who have also successfully revived The Grill—possess that rare ability to refine tradition with the utmost sense of reverence and nostalgia. Major Food Group counts its critics, but Chicago could do with minds such as theirs.

Ciccio Mio may not possess that kind of talented chef-partner—in fact, the menu does not even list the chef’s name—but it celebrates and adapts tradition in its own way. Servers don elegant dinner jackets and indulge diners with a tableside presentation of cheese, salumi, bread, and olive oil. The staff may not literally sing—a favorite flourish of the hulking men who work the floor at Carbone—but approach patrons with a real sense of elegance and bearing. For, while first generation Italian-Americans faced their share of tribulations upon arriving stateside, they earned their wings by offering the native population an earnest sort of hospitality that is still, to this day, rarely surpassed. The tenor and tone of service speaks to that proud legacy.

Of course, Ciccio Mio’s menu tells the most consequential story. Their meatballs are a blend of beef, pork, and veal. The house salad is studded with salami—the fried calamari with cherry peppers. The pastas include orecchiette with sausage and rapini—oh, and spicy vodka rigatoni too. There’s shrimp scampi, branzino, Chicken Vesuvio (a “Chicago original”), and chicken parm too: a rogues’ gallery of the classics—all cleaned up a bit, but avoiding any undue ostentation.

But the restaurant does play with the canon just a little bit. Gnocchi is rendered in a “lamb sugo” style with braised meat and a rosemary gremolata. A typically heaping portion of lasagna is transformed into a more manageable “rotolo” form and flavored with a Bolognese sauce. Ora King Salmon—a favorite ingredient across Hogsalt’s establishments—is served simply with a remoulade (surely something for the less adventurous diners that might grace Ciccio Mio’s hallowed booths). And braised beef cheek—coated with red wine demi glace and served atop soft polenta—offers a more refined counterpoint to the restaurant’s bone-in, coal-fired ribeye with roasted garlic and fried rosemary.

The desserts—a berry pavlova and a dish of cannocini (a sort of crisper, lighter cannoli)—show a surprising restraint. Given how good the pies and cakes next door at Bavette’s are, you’d like to see a rendition cheesecake or tiramisu make an appearance. Surely, the pandemic worked to inhibit Ciccio Mio’s menu development just a little bit. But customers won’t be left wanting. The classics are well conceived and the environment rings true.

Despite flashes of innovation, Ciccio Mio proudly preserves the “Italian-American” dining tradition. It updates the genre without diluting any bit of its essence. And it stands as a shining example of its dishes’ enduring quality. To that extent, the restaurant really corners the market on any modern interpretation of the form—unless someone in Chicago is willing to aim for a bigger, better, more comprehensive embrace of the style.

Formento’s

Located just a bit further west than Alla Vita and Bar Siena down Randolph Restaurant Row, Formento’s promises “bright and light flavors of Italy” and “an array of dishes steeped from [sic] traditional family recipes alongside new-age dishes.” The establishment is alternatively called “an Italian-heritage restaurant” (that’s a new one) whose name is drawn from “Nonna Formento,” the grandmother of co-partner John Ross.

He and Phillip Walters run B. Hospitality Co., which partnered with Boka Restaurant Group on their former Italian restaurant Balena. They also currently manage Swift & Sons alongside BRG—making it all the more strange that Boehm and Katz would open a competing concept in the same neighborhood.

But, truth be told, Formento’s—being in the Italian chophouse tradition—is positioned a bit more upmarket than Wolen’s sorry pizza, pasta, and salad experiment. B. Hospitality Co. does run an adjacent property—Nonna’s—that offers “grab and go” slices, sandwiches, and salads. But that is merely a small, spinoff space, and it must be said that—as a separate, sprawling restaurant—Alla Vita intentionally aims for far broader appeal and value than Formento’s does. So BRG, despite being greedy for their own piece of the (pizza) pie, is not quite stepping on the toes of their chums. (Though you’d love to know what Ross and Walters thought of Alla Vita’s announcement).

Formento’s menu comprises an intriguing range of offerings that defy being as easily categorized those offered at this survey’s other, aforementioned establishments.

With regards to the “Italian-American” genre, chef David Schwartz’s menu offers a “chop” salad filled with that signature hodgepodge of provolone, cured meat, olive, and Italian dressing tossed with iceberg lettuce. A starter of fried cauliflower with lemon and chiles receives a flourish of crispy pepperoni. There’s a classic spaghetti and meatballs—surprisingly, the first of the restaurants in this article to offer one—as well as a dish of squat, curved canestri noodles served with pork neck gravy, fennel sausage, and—also—a meatball. And, of course, the menu offers a classically-styled chicken parmesan to which customers can add spaghetti for an additional fiver.

As far as “Italian-Italian” fare, Formento’s offers tuna crudo, a tempura-fried fritto misto, grilled octopus with giant white beans, and grilled tiger prawns with fennel pollen. The salads include one made from gem lettuce (featuring radicchio, Pecorino, and an oregano vinaigrette) and another from kale (paired with brussels sprouts, raisins, more Pecorino, and a citrus vinaigrette). Classically-styled pastas include a bucatini cacio e pepe, a bucatini carbonara, strozzapreti (with spring onion pesto), a seafood orecchiette, and a spinach and artichoke agnolotti.As far as entrées go, you can only really single out the “Whole Grilled Branzino” as being emblematic of old world simplicity. Still, it is served with pea tips (a favorite ingredient in stir fry, though one you think that captures the prototypical crunch of rapini) and chiles.

So how would you class the sizeable remnant of the menu that resists your chosen “Italian-Italian” vs. “Italian-American” dichotomy?

Where does one placed a whipped ricotta defined by pistachio dukkah (an Egyptian dip/condiment) and hot honey? Or a pork chop served with frisée, apple salad, and Sauce Robert (a compound sauce of onions, white wine, demi-glace, and mustard)? How about a roast chicken served with spaetzle? And a side dish of cauliflower alla Robuchon? The steaks—no doubt, one of the star attractions of the concept—are invariably served with Bordelaise sauce too.

Formento’s is right to call itself an “Italian-heritage restaurant.” It winks at tradition—and is sure to serve a few beloved items, both “Italian-Italian” and “Italian-American”—while transcending it at will. Schwartz borrows ingredients and techniques from anywhere that might make for a more delicious, engaging variant of a familiar dish. That could mean drawing on anything from Japanese tempura batter, Egyptian dukkah, German spaetzle, or a canonical French sauce to gussy up a given item.

It’s not sacrilege; rather, it reads as an attempt to reinvigorate the “Italian steakhouse” tradition with a dash of this and a bit of that. The substance of the experience is still there, and the kitchen—more than showing off—endeavors to achieve satisfaction with a bit of a twist. Relative to Adalina, Formento’s pushes boundaries just a bit further (though never outside the realm of comfort). Being, in your mind, an Italian steakhouse first and foremost, it lands on the “Italian-American” side of the equation with a particular affinity towards non-traditional compositions that offer the genre a shot in the arm.

Gioia

Gioia Ristorante + Pastificio stands as yet another of Chicago’s new “Italian” restaurants. It was set to open in 2019 but found itself—like so many other things—derailed and delayed. Like Alla Vita, Bar Siena, and Formento’s, the establishment is located on Randolph Restaurant Row—being located even further westward than the others. (With all the various expressions of Italian dining studded throughout that promenade—not least of which, the legendary J.P. Graziano Grocery—can we not term Randolph a next-generation “Taylor Street”?)

Gioia is the brainchild of chef and partner Federico Comacchio, who was born in Lombardy and counts as formative experiences his time at the Michelin-starred La Quinta Ristorante (in Lodi) and Sadler Ristorante (in Milan). Comacchio made his way to Chicago in 2000, working as the executive chef of 437 Rush for twelve years and, later, Coco Pazzo for another seven. In opening his own establishment, “he is thrilled to express his interpretation of regional Italian cooking with the purity of ingredients that ignited his journey more than three decades ago.”

More specifically, Gioia—if the Pastificio titled didn’t give it away—touts “12-15 different types of pasta made daily in-house” as the “centerpiece” of the restaurant. It also touts an “ever-changing menu…fueled by Comacchio’s regular visits to Italy to eat and learn from local artisans.” Such an expression of simplicity and humility—built on the back of nearly two decades of pleasing Chicagoans’ palates—will hopefully allow the experienced chef to shine within such a crowded genre.

Though rather clearly (and uniquely, relative to Adalina and Alla Vita) positioned within the “Italian-Italian” category, it is worth exploring to what degree Gioia’s menu transcends the tradition which Comacchio clearly knows so well.

The chef’s antipasti include a warm seafood salad (with fava bean and avocado tartare), a branzino crudo, and a pizzetta made with wild mushrooms, taleggio, and speck. His rendition of a fritto misto involves soft-shell crab, zucchini blossoms, Stracciatella, and colatura—a sort of Roman fish sauce. Also of interest is a tortina al tartufo comprised of a Tuscan shortbread, warm Robiola cheese, asparagus, salted caramel, and black summer truffle.

The much-touted Pastificio section includes a tableside paccheri (a tube shape even wider than rigatoni) “for two” paired simply with tomato sauce and 22-month-aged Parmigiano. There’s a classic bucatini cacio e pepe—quite a popular dish within Chicago, it seems—and a Tuscan pici (a “fat spaghetti” shape) made with meat ragù.

A ramen di pesce—made from tagliolini noodles in a “seafood & crustacean broth”—sounds quite unique. With the city having already weathered something of a ramen craze, Comacchio’s thoughtful treatment of the form in a bonafide Italian style could prove to be one of Gioia’s most attractive lures. Its counterpoint, perhaps, is a slightly more traditional tagliatelle di mare made with high-quality Spanish anchovies, sea urchin, clams, Mollichella (bread crumbs), and—interestingly—noodles made from chickpea.

The griglia e secondi category contains simpler preparations like an eggplant parmigiana and grilled, butterflied branzino. Yet, Comacchio displays a bit of imagination by pairing a TJ’s free-range chicken (sourced, you believe, from a small farm in Minnesota) with vegetables fried in a tempura batter carbonated with Prosecco. The chef’s pork preparation—maialetto—comprises Kilgus Farm Berkshire pork belly, its “baby” ribs, and sausage. Meanwhile, Gioia offers two additional entrées designed for two: a beef tenderloin with “pesto fiorentino” and a beautiful “double veal Milanese” (nicknamed an “elephant ear”) breaded, rather ingeniously with the crumbs of leftover breadsticks. Man, if that doesn’t make your mouth water!

The menu’s contorni, too, demonstrate a bit of flair. Roasted new potatoes are rendered as “chips” by way of black summer truffle butter and 24-month (rather than the previously used 22-month) aged Parmigiano. And roasted shishito peppers are Italianated via Calabrian Tropea onions and vincotto—a thickened wine reduction popular in rural Italy.

Whereas Fabio Viviani indulges quite distinctly in adapting his native touch to American tastes, Federico Comacchio displays more restraint. His menu reflects a greater sensibility of simplicity that, nonetheless, carefully includes novel ingredients and techniques while—nonetheless—still endeavoring to please.

That might be as simple as using avocado, shishito peppers, or soft-shell crab in an unmistakably “Italian-Italian” manner. It might mean fashioning an Italian-style “ramen” from a rich seafood broth or a plate of tempura vegetables with a batter leavened by Italian “bubbly.” Dishes like the maialetto and truffled potato chips (which recall Viviani’s own potato skins) demonstrate an understanding of the hands-on manner in which Americans love to eat—while his “elephant ear” Milanese is surely destined to become the city’s standout representation of the form.

Gioia strikes you—despite the glut of “Italian” concepts storming onto Chicago’s dining scene—as a worthy addition to the genre. Comacchio humbly plied his trade for quite some time here, and you see nothing self-indulgent about the manner in which he is jutting out on his own.

While an Alla Vita draws on a tradition it has no claim to for the sake of making money, Gioia carefully writes a new chapter through which an Italian cook shares the riches of his home country, his experience in the industry, and his devotion towards expanding and exciting Chicagoans’ palates. Comacchio’s establishment does not tout any glitz or obvious gimmick—and that’s a good thing.

The restaurant—which is among the most distinctly “Italian-Italian” on this list—carefully breaks from tradition just a bit. Such restraint often signals deep quality, and Gioia will surely merit additional coverage upon its opening.

Gibsons Italia

The jewel in the crown of Chicago’s signature Gibsons Restaurant Group—having opened in October of 2017—combines two of the city’s most popular forms: the luxe steakhouse and the hearty red sauce joint. While the aforementioned—in the case of Formento’s—“Italian steakhouse” genre has long sought to do the same, the whole—in such a case—is often less than the sum of its parts.

For an “Italian steakhouse” often offers little more than a few prime cuts appended onto a premium red sauce menu. And, as the prototypically “Italian-American” Ciccio Mio itself even shows—by way of its coal-roasted ribeye—a token bit of beef is already a stalwart of that genre anyway. Consumers, thus, are stuck between a taste for pasta and one for steer. Maple & Ash offers plenty of premium steaks alongside a dish of dry-aged meatballs and another of ricotta agnolotti. RPM Italian, taking the opposite approach, offers plenty of premium pastas alongside one type of Filet Mignon, one type of bone-in ribeye, and an—admittedly excellent—Bistecca Fiorentina porterhouse.

Gibsons Italia—beyond offering, you must admit, one of Chicago’s finest views—looks to bridge the gap between two distinct concepts. Under chef Jose Sosa—a veteran of Ambria and Boka who has, consequentially, become the culinary face of the entire group—it looks to compromise on neither dimension of the steak-pasta equation. Surely, for a litany of reasons, the venture’s success was all be guaranteed. But does Gibsons Italia put any meaningful stamp on the “Italian-American” or “Italian-Italian” genres?

The restaurant promises that it is “built on a tradition & elegance that is relentless in the pursuit of the very best,” one in which “chef-driven tastes of Italy are paired with the superiority of Gibsons Steakhouse, creating a restaurant that makes the familiar, exceptional.”

Gibsons Italia’s menu starts with osetra caviar, burrata, and potato chips. It segways into tuna crudo and shellfish towers—that staple of the steakhouse genre—distinguished by Italianate accompaniments such as San Giacomo (balsamic vinegar) mignonette for oysters, salsa rosso for lobster, and a mostarda Dijon for king crab.

Then, there comes the antipasti. A crabmeat and avocado “parfait” (with mango, bell pepper, cognac mayo, and Calabrian chili oil) and a wagyu beef tartare (with burnt onion aioli) speak to the steakhouse genre while retaining a tinge of Italian charm. The arancini cacio e pepe (there’s that phrase again!), charred octopus, “Italia meatballs,” and platter of San Daniele prosciutto with mozzarella di bufala, compress cantaloupe, and avocado carpaccio speak more clearly to an “old world” sensibility.

The Zuppe e Insalate section features old steakhouse favorites like a king crab bisque and Caesar salad. Gibson Italia’s play on a wedge melds the genres by way of gorgonzola and crisp pancetta standing in for generic blue cheese and bacon. Meanwhile, the “Italian Grain Bowl,” a combination of arugula, farro, barley, lentil, avocado, and two kinds of beans, reads like something served at BIÂN but, in truth, does speak to an “Italian-Italian” rusticity (as far as “health food” goes).

From your very first visit to the restaurant, much ado has been made about Gibson Italia’s “housemade gold-extruded pasta” made from “Italian heritage organic stone ground Senatore Cappelli flour.” That word salad of buzzwords probably belongs up above in the Insalate section, but the idea behind gold extrusion—to hear the staff tell it—is that the process imparts microscopic grooves into the pasta that enable a superior retention of sauce (and, thus, a better mouthfeel). You cannot say you have noticed any particular advantage imparted by this process—or the heritage flour itself—but the pastas are certainly good.

The offerings include, of course, cacio e pepe. There’s a spaghettini and meatballs, a spicy rigatoni with vodka sauce, and a pappardelle defined by Neapolitan beef and onion sugo. The more refined dishes include a raviolo (singular) carbonara topped with crispy prosciutto and truffle, as well as a longstanding risotto made from an aged Carnaroli rice called Acquerello and topped with scallops.

Entrées include the ever-present branzino and Ora King salmon (this time with Sicilian eggplant caponata), as well as a pan-roasted, humane-certified Green Circle chicken (with charred rapini and lemon). Sosa’s rendition of Veal Milanese isn’t as gargantuan as Gioia’s, but it has stood as a great representation of the form and a good fit for the menu since the restaurant’s inception.

Of course, the standard bearers of any Gibsons property—yes, even that Disney Springs location—are the steaks. And Gibsons Italia’s offering are altogether undiluted by hybrid nature of the concept. They include the classic “Gibsons Prime Angus,” “Gibsons Grassfed Australian,” Japanese Miyazaki and Olive beef, and Carrara 640 wagyu from Australia. The “Housemade Sauces” include bearnaise, steak sauce, au poivre, black truffle butter, and creamy horseradish—an assemblage that, again, resists any undue Italianate influence.

The sides—or contorno (every one of these restaurants embraces different spellings, it seems)—split the difference. There are crispy brussels sprouts (accented by prosciutto and parm) and a double baked potato (with ricotta and truffle), as well as more standard steakhouse fare in mushrooms (in red wine sauce), fresh-cut fries, and French potato puree.

The Dolce section of the menu is more distinctly Italianate, particularly a classic tiramisu and a lemon-almond semolina cake (with basil crema pasticcera). A banana gelato, however, is Americanized by way of an Oreo crust and a “Bananas Foster” treatment of brûléed fruit with salted caramel. The fusion of the steakhouse and “Italian” genres reaches its apotheosis in a “Spumoni Baked Alaska,” where chocolate cake, pistachio nougatine, chocolate ganache, gelato, meringue, and Luxardo cherries form a symphony of sweetness.

In the final analysis, you do think Gibsons Italia succeeds in combining a meaningful steakhouse experience—defined by seafood, salads, steer, and sides—with an ample array of antipasti, pastas, and other entrées that form a refinement of the “Italian-American” genre. Yes, you say “Italian-American” despite the preponderance of “authentic” Italian ingredients being showcased. They represent a form of premium sourcing that raises the cuisine up to a “luxury” Gibsons standard.

However, to the restaurant’s credit, the dishes aim for a sense of decadence and satisfaction that displays a reverence for the Chicago “red sauce” tradition. For the American steakhouse form—one that some might label excessive—is a kindred spirit to the “Italian-American” style of hospitality. The notion of the “Italian steakhouse,” as such, has long sought to blend the two. But Gibsons Italia, though lacking the trappings of a Ciccio Mio or the breath of influence seen at Formento’s, truly refines the genre while retaining a classic orientation. Moreover, it works to preserve that heritage through a clever nesting within a proper steakhouse form.

Adalina—being the brainchild of a Gibsons alumnus—will form an interesting counterpoint to Gibsons Italia. Though, of course, it’s far enough away as not to consciously cannibalize their business—nor the steak selection being offered nearby at its original Rush Street location.

Monteverde

Monteverde—from almost the moment it opened in November of 2015—has catapulted itself towards the very top of Chicago dining. Though it still counts itself as one of the city’s toughest reservations—perhaps, even now, tougher than ever—chef Sarah Grueneberg has ceaselessly developed her menu over the years, ensuring that each iteration brings with it a new range of droolworthy delights.

Of course, Grueneberg notably held a Michelin star for several years as Spiaggia’s executive chef and has developed quite a following as a contestant (then host) across food media. But, at core, she’s a “chef’s chef” who can almost always be seen happily leading her line, presenting dishes firsthand, and chatting up legions of satisfied diners. Grueneberg, on all accounts, is a shining light of the city’s dining scene, but—beyond that—the nature of her cuisine displays a rare depth and complexity within the crowded “Italian” genre.

Her piattini have long be defined by a beautiful platter of burrata e ham—that “ham” moniker (used to describe San Daniele prosciutto) signaling something of a liminal place between “Italian-Italian” and “Italian-American.” Filling the role of focaccia or some other standard loaf, the chef makes use of tigelle, a traditional round bread from Modena that arrives piping hot. Guests can fill it with the prosciutto, an accompanying housemade mostarda, or any number of supplements like Salumi Chicago finocchiona (the fennel-flaked “king of salami”) or housemade prosciutto butter.

The Oma’s Green Mountain Salad—one of Grueneberg’s longstanding specialties—has long struck you as being “Californian,” which is to say a fresh, elegant expression of American farm-to-table cooking. Items like the Insalata alla Romana—with asparagus, chicories, and garlic anchovy vin—and ‘nduja arancini reflect a greater fidelity to an “Italian-Italian” sensibility.

Still, items like a blackened Texas redfish picatta and a recent addition of grilled hanger steak with charred Tropea onions and Piedmontese hazelnuts work to construct a new canon. The dishes are forward in the pleasure they offer but, nonetheless, are composed with a layered complexity that avoids the heaviness of typical “Italian-American” fare. The reflect an application of an “Italian-Italian” mindset towards making food that utilizes American ingredients with the aim of pleasing domestic palates. This is particularly true given the fact that these “smallish shared plates”—in their scale and balance—read like entrées.

From the very beginning, Monteverde has structured its menu around “Pasta Atipica” and “Pasta Tipica” categories that spell out, quite distinctly, the manner in which Grueneberg tinkers with or respects tradition. The former category has included the longstanding cacio whey pepe—a version of that classic dish enriched with whey protein—as well as its successor: a pecorino e limone that captures some of the same wonderful, buttery mouthful (given that it retains the whey) with a cleansing burst of whipped lemon ricotta and Campanian hot pepper. Other offerings have included a wok-fried arrabbiata (with head-on gulf shrimp), a country ham-stuffed tortelli, hand-stamped cocoa corzetti, egg yolk raviolo (with garam masala and pomegranate molasses), and an imaginative “Twin Ravioli” inspired by Shakespeare’s Comedy of Errors.

The “Pasta Tipica” category has featured more classic preparations like gnocchetti con pesto, spaghetti al pomodoro, linguine (with shrimp, not wok-fried), ricotta-filled agnolotti, hand-cut tagliatelle (with white Bolognese ragù), and a lasagna al forno (which, nonetheless, features a Mangalitsa pork sugo and Melrose peppers). That last example is instructive, for Grueneberg’s “typical” pastas need not bow before “Italian-Italian” ingredients. Rather, they retain the essential form of traditional preparations while distinguishing themselves here and there. For example, one rendition of the pomodoro featured sesame za’atar while the current version offers the addition of chile garlic oil for an additional dollar.

Monteverde’s “Per la Tavola” section has long stood out to you as a reinterpretation and refinement of the “Italian-American” style of dining. Lighter fare has included whole fish like wild red snapper, striped bass alla plancha, grilled Texas redfish acqua pazza, and skate schnitzel—each adorned with an assortment of “Italian-Italian” ingredients like lentils, salsa verde, pistachio, polenta, and fennel pollen.

The main event, assuredly, is the Ragù alla Napoletana, a heaping bowl of braised pork osso buco, soppressata meatballs, and cacciatore sausage served atop fusilli with some token leaves of broccoli rapini. It’s a dish that encapsulates the quintessential Southern Italian “Sunday dinner” tradition—one that, due to the nature of Italian immigration, disproportionately shaped the development of “Italian-American” cuisine. A more recent addition to the section has been a “whole bird” chicken parm that Grueneberg used to beat Bobby Flay on the eponymous Food Network show. Rounding things out, a prime bone-in ribeye has long stood as one of the best steak preparations in the city—enlivened by a drizzle of balsamic vinegar, cherry tomatoes, and spring onions.

The manner in which Monteverde’s menu blends “typical” “Italian-Italian,” “atypical” “Italian-Italian,” and an assortment of new and refined “Italian-American” creations makes the restaurant somewhat hard to categorize. There’s no doubt that Grueneberg, having risen through the ranks at Spiaggia, has mastered “old country” tradition. Yet, she wholeheartedly embraces local products and bends them towards familiar, delicious forms. She bridges the gap between the two genres, imparting twists here and there that give every dish her stamp.

Grueneberg occupies a space that is eminently her own, reflecting a vision of Italian cooking in American that is brave enough to offer the best of both worlds. You think her menu is slightly more defined by “Italian-American” cookery than “Italian-Italian.” However, her cuisine still lands somewhere close to a middle ground—being defined more by the many ways she tweaks and transcends tradition to please her guests in novel ways.

Rose Mary

The story behind Rose Mary—which you have already described to some degree—reads somewhat like Monteverde’s: a former Spiaggia executive chef and food media darling strikes out on his own, catapulting immediately to the top of Chicago’s dining scene. (Though, you must say, the road from being buzzworthy into becoming an institution is a long one. But, having eaten there four or five times already, you believe Rose Mary has the goods to do so—just spring for a proper wine professional).

Despite possessing that dastardly title of “Top Chef champion,” Joe Flamm, like Sarah Grueneberg, leads his line with grace and class. He works his dining room with a broad-shouldered charm and delivers an equally-broad smile in the countless photo-ops he grants the swarm of “foodie” lemmings. You question the chef’s decision to partner with Sancerre Hospitality—whose West Loop steakhouse, BLVD, somehow maintains an altogether anonymous presence within Chicago’s favorite genre. (Really, the best praise they can tout is having “one of the most beautiful restaurant restrooms in the world” as declared by People Magazine). You would recommend Sancerre cut their losses and deliver BLVD’s cellar to Rose Mary, for Flamm’s ribeye preparation is better than what their steakhouse is slinging anyway.

But you do not mean to spoil your forthcoming review of Rose Mary, whenever that time comes.

For the task at hand—orienting Flamm’s restaurant among all the other “Italian” concepts in town—means grappling with the menu’s distinct Croatian influence. Yes, that certainly means the restaurant could not be categorized all too distinctly as “Italian-Italian” or “Italian-American.” But you can certainly assess, in a more overarching manner, the extent to which the chef indulges American palates or looks to wrap himself in that illusory banner of “authenticity.” Or, of course, he might offer something in between.

To start with, Flamm’s zucchini fritters could easily double for latkes: they are tightly woven, wonderfully crispy, and enlivened by parm, pine nuts, and a pesto aioli. Salads like the coal roasted beets (with kajmak cheese), stracciatella (with lepinja flatbread), pinzimonio (a sort of crudité creation with bagna càuda), and the tomato, farro, and asparagus (with ricotta salata) are all a joy to eat. They demonstrate the sort of excellent layering of textures, paired with bold flavors, that surely calls to mind the chef’s time cooking at Girl & the Goat. Each composition is highly approachable for the inexperienced guest, yet Flamm finds a way to slip in a curious element from Croatian or Italian cuisine to pique interest and educate.

The “Fish” section of Rose Mary’s menu might be its strongest: there, Flamm takes no prisoners in his pursuit of flavor. Simple grilled clams are galvanized via smoked ramp butter. A tuna crudo is beefed up—quite literally—with shallot-beef fat vinaigrette and a veal aioli that imparts an unparalleled richness to what has, around town, become something of a trite dish. Grilled shrimp are paired with a buzara sauce that—containing breadcrumbs, garlic, parsley, and tomatoes—do not fall all that far from Chicago’s famous Shrimp De Jonghe.

Meanwhile, baby octopus is rendered “peka style,” a traditional Croatian preparation that involves slow cooking with olive oil, vegetables, and herbs in the titular, domed peka pot. The end result yields a satisfying plate of tender, steeped tendrils, garlic, potatoes, and peppers with a “stick to your ribs” quality octopus—save for Michael White’s at Marea and Otto Phan’s at Kyōten—rarely ever attains. Of course, Rose Mary offers a half branzino too. It is, perhaps, not as distinguished as the aforementioned dishes. But it displays beautiful charred marks on its skin and features a flavorful “paprikas” sauce.

You have already covered Flamm’s pastas in some detail. And you think it is also right to include his risotto in the following statement. These sections of Rose Mary’s menu speak more to an “Italian-Italian” sensibility, albeit while retaining the burst of Croatian flair that characterize the establishment. For Flamm is known as a master of pasta-making, and embracing smaller portions with subtle textures and refined, concentrated flavors enables a broader enjoyment of the category.

The chef does a great job of bending the items in the other sections towards a more Americanized pleasure. But Americans are perfectly familiar with the enjoyment of pasta, and—you think—they are more comfortable being taken on a journey relative to the many other establishments in which they may simply stuff their face. So Flamm embraces a lighter touch, guiding guests towards deeper enjoyment of each pasta’s nuance. And he distinguishes those dishes with a Djuvec sauce, an Abruzzese ragù, some beef cheek pašticada, a Skradin-style mix of veal with chicken, or a “crni” (black) version of risotto. Yes, there’s a cacio e pepe on offer—the pasta for which Flamm recently changed from cavatelli to radiatore.

Rose Mary’s “Meat” section features familiar forms like grilled chicken wings (with a Calabrian chile-basil vinaigrette) and pork ribs “Pampanella” (with an agrodolce also made from Calabrian chile). The most distinctly-labeled Croatian dishes—perhaps across the entire menu—are a beef burek (beef stuffed into phyllo dough with onions and mozzarella) and a ćevapi of caseless sausage, ajvar (a pepper-eggplant condiment), and kajmak cheese stuffed into that wonderful lepinja flatbread.

Flams roasted duck with plum glaze is classically executed, though you have quite enjoyed the accompanying, highly tender accompaniment of sour cabbage. A dish of lamb shoulder is sweetened—perhaps just a bit too much, by your measure—by a lamb-fig jus. It is served alongside blitva, a Croatian dish of Swiss chard and potatoes sautéed with garlic that lends the composition a satisfying stewed quality.

And, at long last, there is Flamm’s foray into steak: a 32-oz bone-in ribeye topped with charred ramps and hot paprika oil. One might not feel the need to indulge in such an extravagant preparation of beef at a restaurant that offers so many distinct items. But the dish is a great one: a tip of the hat towards the soul of Chicago dining that, bite-for-bite, is amply seasoned.

Though Rose Mary’s pastas nod towards Flamm’s mastery of the form while at the helm of Michelin-starred Spiaggia, they stand as the only overtly “Italian-Italian” expression on the menu. Yes, Italianate flavors—along with their Croatian brethren—are everywhere. But the chef succeeds wildly at packaging traditional ingredients and flavor combinations in a manner that American palates simply cannot resist.

He does not call on diners to contort themselves in order to appreciate some impenetrable mystique of “authentic” Italian or Croatian cuisine. Rather, he humbly expresses his vision of how those cultures might offer guests greater pleasure. Flamm’s novel touches never dominate fare that is always eminently eatable. He puts his knowledge at the service of satisfaction—a viewpoint that strikes you as prototypically “Italian-American” in nature and that, you think, ensures Rose Mary’s longstanding success.

Spiaggia

After covering two of Spiaggia’s spiritual successors—Monteverde and Rose Mary—it seems strange to end with the granddaddy of Chicago’s “Italian-Italian” restaurants. In truth, the hallowed Michigan Avenue establishment is a national benchmark for Italian fine dining, having trained at least two of New York City’s finest chefs in that genre. Tony Mantuano’s deserved retirement surely spelt doubt about Spiaggia’s future, but the institution—even if its future seems precarious without is longtime fearless leader—has not lost any of its ambition.

Grueneberg, Flamm, and Mantuano left massive shoes to fill, and it seemed somewhat surprising that the kitchen was left in the care of Eric Lees, Flamm’s humble sous chef who claims to have no interest in replicating his forerunners’ Top Chef fame. “The chefs I grew up around—the chefs I looked up to the most—didn’t have any of that stuff. It’s not for everyone,” he admirably stated.

Lees is originally from Minnesota and graduated from Le Cordon Blue in Minneapolis. He worked at Quince (in Evanston, not San Francisco) and under Mathias Merges at A10 and Yusho—a respectable resumé, but hardly one to write home about when helming a perennial Michelin star winner. The chef views his three years under Flamm and Mantuano to be the defining moment in his career—with the traditional pilgrimage all newly-minted Spiaggia chefs take to Italy (including, of course, a visit to three Michelin star Dal Pescatore) surely serving as the cherry on top.

Lees seems a bit green on paper, but that is exactly what you like about his stewardship of Spiaggia. Surely, under Flamm and Mantuano, he comprehended the excellence for which his establishment is known. There is no doubt that he possesses the virtuosity and dedication demanded to run such a kitchen. Yet, there is something still unformed about him, a potential to develop a particular personal style that may reinvigorate one of those rare surviving Chicago restaurants that can counts decades of success.

The chef is of the Midwest; he has a sense of the city’s heritage and its great chefs. He has experienced the bounty of the “old country” firsthand. And now, he gets to put the pieces together on his own terms. It reminds you a bit of Wisconsin-native and Spiaggia-alum Michael White—the “Midwesterner with Italian soul.” As much as representing “authentic,” “Italian-Italian” cooking—especially for someone from outside of the culture—presents a pitfall, it also contains enormous promise. Lees strikes you as a thoughtful chef, and he is well positioned to connect his Chicago audience to Italy in a manner reminiscent of the many great chefs who came before him.

You tasted Lees’s most recent menu in October of 2020—the so-called “Puglia” tasting centered around the region that forms the “heel” of Italy’s “boot.” The dishes were intelligently conceived and refined in the manner which you have become accustomed to at Spiaggia. However, the chef thoughtfully transcended a pure replication of “Italian-Italian” tradition in the manner which he treat his dishes’ accompanying elements.

His Calamari Ripieni—a stuffed, crispy fried squid—was accented by a smoked tomato sauce. A dish of ippoglosso (or halibut) was paired with a potato horseradish cake. And a lamb braciola—one of Italy’s most pleasing meat preparations—subverted the dish’s usual rusticity by way of a fennel gratin and cleansing notes of rhubarb. A dessert of olive oil cake “two ways,” too, benefits from an irreverent touch of taralli, those favorite twisted crackers of the Italians (and, of which, you are quite a fan yourself).

Of course, Lees could not possibly turn his back on some of Spiaggia’s other classics: the gnocchi with truffles for which Flamm was so well-known, as well as the restaurant’s beautiful dry-aged porterhouse (with truffle hollandaise and crispy potatoes) maintained their high standard. They always serve as a satisfying counterpoint to the tasting menu’s more intricate food.

Under Lees, Spiaggia remains highly traditional, distinctly “Italian-Italian,” but not static. The chef has already shown his own sense of interpreting regional recipes while retaining a reverence for their essence. With the restaurant poised to reopen—and possibly tinker with the exact nature of its concept—in the near future, the stage is set for the legend of Chicago Italian dining to write a new chapter. As always, it will be one in which “authenticity”—in the only dimension that really matters—describes philosophy more than replication.

Coda

While this list is in no way exhaustive—in fact, you made a point of excluding excellent restaurants like Piccolo Sogno and Riccardo Trattoria/Osteria that are too obviously “Italian-Italian” in approach to be interesting (one can imagine just exactly where they’d land on the grid)—it seems clear that the “Italian-American” genre isn’t going anywhere.

Restaurants like Spiaggia fight the good fight for the recognition of Italy’s “high cuisine”—one that, certainly, has always paled in comparison to the codified technical prowess of the Japanese and French. But can it not be said that the refined expression of Italian culture is—within the context of the fare’s worldwide popularity—the outlier?

Yes, Italians in Italy surely benefit by not stuffing their face with mountainous meatballs, “sides” of pasta, and all the other popular totems of “Italian-American” fare every day. But “abbondanza” transcends portion sizes, which have—it seems—naturally scaled themselves down. The longstanding appeal of the “red sauce” joint comes from its combination of what is, in its essence, comfort food with all the trappings of a warm, rollicking night out.

Italian-Americans, going back again to Carmelinda Galli’s boarding house, exceled—like all successive generations of hardworking immigrants—in doing a lot with very little. To some, tomato sauce stacked upon meat stacked upon cheese stacked upon pasta begins to get boring. And the next generation of chefs cooking, more or less, with a mind towards “Italian-American” sensibility have succeeded in refining recipes without making them precious.

But the pervasive popularity of the genre rests with something of a guarantee: that guests will be served their fill of satisfying food with little pretense and a dose of class. Ciccio Mio, by all accounts, embodies that fantasy in spades. Adalina looks to bring the dream into the future while Alla Vita—your favorite punching bag—simply seeks to leverage it to pad BRG’s pockets.

As long as pretentious chefs disappoint their customers, Italian-American cuisine will reign. It will be the slice of pizza that saves your evening from the pits of molecular gastronomic despair. It will be the bowl of pasta that buffers your binge drinking of wine during some stilted, prissy French tasting menu.

The restaurants will act as one of few “true norths” towards gustatory satisfaction—a reminder that any rarefied ideals of “food as art” must rest upon eternal foundations of service, comfort, and satiation.