Though, just a few years ago, children as young as 8 years-old were treated to a three-Michelin-starred lunch at Thomas Keller’s Per Se, few Americans are—in fact—nursed on fine dining.

Of course, the destruction of cultural barriers to connoisseurship and the mainstreaming of the “foodie” identity might change that. For the immersive, interactive, and visceral nature of gastronomy has transformed it into one the “Experience Economy’s” high art forms. And, relative to pleasures of the stage and screen, a meal shared by discerning parents and their well-behaved children might offer greater bonding through a shared sense of discovery. Those indulgent dinners—rooted, nonetheless, in quality ingredients—could inoculate kids against the siren song of the industrialized food system. Maybe the concept of the celebrity chef—that of a magician or “mascot” conjuring creative cuisine—contains enough cachet to overshadow snack and fast food marketing budgets. Maybe the humble craftsperson—communing with and expressing nature through their fare—can be a shining light leading kids away from processed, alienating (but alluringly convenient) comestibles.

You dream of that future—but cannot forget your past. Before the proliferation of social media, fine dining retained a greater sense of mystery. Yes, you could read the newspaper reviews and gaze longingly at the pictures in magazine features. Zagat gave its ratings and Michelin doled out its stars, yet their accompanying blurbs could never quite capture a restaurant’s feel. They revealed little about the nuts and bolts of dining at the table—though programs like A Cook’s Tour might have offered a voyeuristic peek behind the white tablecloth.

Online, eGullet brought dining enthusiasts and early food bloggers into contact with industry figures. The trailblazing message board served to organize discussion—with all the limitations of the early aughts’ media capability. That proved, you think, to be a blessing. In the age before smartphones, one’s restaurant recollections were engaged verbally. You could not simply post a range of high definition photos and impress the audience with a feast for the eyes. Rather, your sense of the hospitality and cuisine had to be formed into words. Memory and nostalgia needed to be engaged, and analysis thrived as users lacked any easy recourse to a conspicuous consumptive collection of images. Braggadocious diners sharing experiences bereft of any real insight revealed themselves easily, and opinions were shared in the interest of advancing the craft.

This is all to say, you cut your gastronomic teeth at a time when dining experiences were more intimately defined. Even if you sought the most exhaustive information available on a given restaurant, you’d only be left with a mixture of multimedia scraps and other guests’ written perceptions. Those diners—unlike today’s “influencers”—shared experiences for the sake of expanding knowledge. They necessarily grappled with their own tastes and the essential, ephemeral nature of any restaurant. There was no prestige to be gained by simply showing one’s face “here” or “there.” Quality needed to be communicated intelligently, and recommendations reflected the essential truth that judging quality was a personal interpretative act.

While the mimetic power of Instagram has enabled “foodie” culture’s growth, it has come at a cost to dining’s transcendent power. Viewers are not led to engage with the craft of cuisine, but with its totems. The audience does not dream of visiting a renowned restaurant and soliciting a singular, personal experience. Rather, as is the case in all luxury branding, the mark aspires towards the perceived status of their chosen influencer. For the ticket price, the sucker expects to step into their ill-chosen idol’s shoes and envelope themselves with the stench of their “glamour.” Being where they’ve been, eating what they’ve eaten, thinking what they’ve thought is enough to justify their outlay. The chef is reduced from craftsman-artist into a caged animal in a social media petting zoo. The modern “foodie” only needs to receive their money shots to leave happy. For it is through those conspicuous monuments that money is traded for status. It is through those photos and gushing captions that understanding is sidestepped. The farce is then perpetuated upon the next rube further down the social food chain.

You prize your salad days—long before the dawn of OAD’s competitive conspicuous consumptive paradigm. To each establishment, you arrived as a tabula rasa—free from any reference point or expectation. The critics and raters testified that someone, somewhere perceived a certain quality. But “collecting” Michelin stars was not yet a pastime. Dick-measuring in the familiar “foodie” style had not reared its pernicious head, instilling that latent insecurity that one was a sucker for finding enjoyment in a place from which the gastronomic elite had long moved on.

That innocence for which you reminisce ensured that each restaurant made an unadulterated impression. Each establishment shone—or shrank—based wholly on your hermetic relationship. Personal—rather than publicly brokered—taste could develop. A more careful consideration of quality—rather than reductionist lists—could reign. But, freed from any outside influence, you surely suffered ample embarrassment as you and the members of your party learnt the ropes.

“Foodie” influencers might not be experts in etiquette, but their narcissism serves to shine a brighter light on the workings of hallowed dining rooms. Visually, their content induces greater familiarity with a given restaurant’s space. One gleans some sense of an establishment’s formality and contends with the intricacy of the cutlery, glassware, and plateware. One notes the dress code—both of the influencer and the front of house staff—and tailors themself accordingly. Those obnoxious photos of every course signal the meal’s portion size and introduce any novel ingredients that might pose a problem. Perhaps the post will clarify a kitchen’s signature dish, a noteworthy supplemental item, or—simply—the degree of “celebrity” a given chef maintains. The mimetic nature of the influencer-patsy relationship ensures that many of the kinks for those new to gastronomy are ironed out. The duped retraces the steps of the duper, and that script ensures a smooth ride (even as it suffocates any truly personal dimension to the experience).

Looking back now, you revel in the fear you once felt when entering revered dining rooms. You treasure the technical errors, faux pas, and outright mortification inflicted upon those who stewarded your earliest gastronomic experiences. For the true test of hospitality staff is how handle those agonizing moments with aplomb, resisting the temptation to twist the knife and solidify a bad memory. Graciousness, on such an occasion, comes close to godliness. The requisite lesson to be learned is never forgotten—and, quite the opposite, it forms a crucial moment in the development of a bonafide gourmand. Moreover, it endears the given restaurant in the mind of a diner. The establishment reveals itself to be more than an unfeeling crafter of fine cuisine but a consummate host. Hospitality engenders loyalty, and the mercy shone accentuates that it is the humanity—as much as the food—that leads us back time after time.

With that in mind, you humbly offer your recollection of dining missteps, mishaps, and meltdowns. The nuggets that follow have all occurred to you personally or involved a member of your party. While such moments would seemingly be difficult to dig up, you marvel at how many of the restaurants that feature remain among your very favorites. That, you think, would seem to prove your point from the preceding paragraph.

Abandoning Aviary’s Brunch

Once upon a time, that favorite whipping boy of yours—the Alinea Group—concocted a “boozy brunch” at its Chicago cocktail bar. The two-weekend-only affair, you think, was derived from The Aviary NYC’s regular brunch service as part of the Mandarin Oriental hotel. There, the lounge served a three-course prix fixe menu—with items like crab salad, gazpacho, and “steak and eggs”—paired alongside cocktails. Though the venue’s views of Central Park must have formed a gorgeous backdrop for a morning splurge, at least one guest termed her experience the “Worst Brunch in NYC.”

Thankfully, the Alinea Group took a different tack for the Chicago rendition. That “boozy brunch” would comprise two seatings—one at 10 AM, another at 12:45 PM—on two Saturdays and Sundays during the summer of 2018. At only $60-$80 per ticket—before tax and service charge—the mailer promised that guests would “enjoy five culinary stations featuring everything from avocado toast (Alinea Group style) and giant crudités to a raw bar and a Bloody Mary fountain. Oh, and plenty more booze to match. We invite you to mix, mingle, and make the space your own.”

Bright-eyed and bushy-tailed, you arrived just a bit past 10 AM on that fateful first Saturday service. It was strange to see the bar unshrouded by darkness and free from the throngs of walk-ins which typically cluttered its entryway. You entered into the familiar, cloistered space—curtains drawn, patio doors closed—to find the lounge’s usual assemblage of tables and chairs missing. A few of the high-tops typically perched near the entrance were placed here and there. But the floor had been opened—the usual banquettes becoming more like barriers that channeled traffic towards the various “culinary stations.”

You took a moment to survey the scene: bagels and avocado toast near the kitchen, fresh juices running along the side, shellfish and Bloody Mary fountain against the wall at the center of the dining room, and one final station with salads, charcuterie, and cheese towards the rear. Moving opposite the shellfish, you noted the flow of the line. Each patron filled their plate, grabbed a drink with their other hand, and then desperately looked for some place to go. The pitiful number of high-tops had long ago been taken—those lucky parties smartly visiting the stations in shifts so as to retain their coveted surface area. The other guests jostled for any available inch, spilling over onto service stations and balancing dishes on their knees at the tableless banquettes so that they may enjoy the fare.

In retrospect, the promise that guests would “mix, mingle, and make the space your own” should have tipped you off to the looming chaos. But, having taken it all in, you slipped out your smartphone, navigated onto Tock, and secured a last-minute table at Roister. Just minutes after arriving—having enjoyed not one drop nor morsel—you slipped back out the entrance unnoticed and sat down next door for a civilized brunch.

Perhaps that’s not really an embarrassing moment. As a host, you are certainly glad the other members of your party did not mind a sudden change of plans. As a guest, you are sure The Aviary had no hard feelings—assuming they even noticed your absence. For you did not bother to request a refund, and—however rude the gesture of walking out immediately might seem—that decision had the benefit of thinning the crowd a bit for the poor souls stuck behind. (By all accounts, your “solution” meant spending yet more money at an Alinea Group property that morning—hardly a bad break for their bottom line).

While departing in such a fashion felt like a slap in the face at the time, your reaction was corroborated by other accounts of that morning. One guest decried that Aviary’s “event style” brunch meant that “you have to become very competitive and aggressive to find a seat…. You wait to get soup & they don’t have spoons. You find a clean table top, but there’s no chairs.” The staff “appeared stress and annoyed….as if most of them found out last night they were working this morning and none too pleased.” The food was “lackluster” and “made with no enthusiasm.” Ultimately, the “whole ‘event’ was phoned in” with the customer left feeling “duped.”

Another account of the morning characterized it as “a very unpleasant, awkward experience that felt more like unwittingly participating in a sociological experiment.” They described the brunch as an “overcrowded, buffet-style wedding cocktail hour.” Despite finding a “high-top cocktail table,” they “barely had any space for…[their] plates and…drinks, and…were also partially blocking the flow of bussers to have of the space.” Soon, they “realized that there were people around…[them] who didn’t even have a cocktail table,” describing that they had “never seen so many scowling patrons.” The guest even “witnessed two parties fighting over a table.” Ultimately, they also felt “duped” and termed the experience “an overbooked failure and an abuse of the Alinea brand.”

You suppose, at this point, you only feel secondhand embarrassment at what occurred that morning. It was a disastrous dilution of a brand identity that touts itself (to say nothing of pricing itself) as a paragon of hospitality. You count yourself lucky for escaping posthaste.

A Disappearing Act at Chefs Club NY

Two years before (rightfully) abandoning that Aviary brunch, you made a rather more grievous departure from a dinner in New York City. You resided there at the time and enjoyed nothing more than hosting visiting friends and family for weekends (or weeks) of superlative hospitality. Stalwarts like Le Bernardin and Brooklyn Fare were guaranteed to delight even the most experienced diners in your retinue. However, on some lucky occasions, your guest’s trip would coincide with a special dinner—a limited engagement—that you both could get giddy about.

In June of 2016, Food & Wine’s former Chefs Club concept—now a separately owned entity—hosted chef Zaiyu Hasegawa of Tokyo’s Den. Back then, the restaurant held one Michelin star and had only just ranked 37 on William Reed’s “Asia’s 50 Best Restaurants” list. By 2017, Den was ranked 45 in the world. In 2018, it climbed to rank 17 (and collected its second Michelin star). As of 2019, Den occupied the 11th position on “The World’s 50 Best Restaurants” list, distinguishing itself as the “Best Restaurant in Japan” and seeing Hasegawa receive the “Chefs’ Choice Award” from his top 50 peers. And, in 2021’s ranking, the restaurant stands as 3rd best in Asia and still holds the honor of “Best Restaurant in Japan.” You may take William Reed’s lists with a grain of salt, but there is no denying that Hasegawa’s rise has been stratospheric.

So, how lucky were you to partake in some expression of Hasegawa’s vision on the cusp of him receiving such international esteem? Lucky, yes—grateful, no. And you cringe thinking back at how unceremoniously the evening ended.

See, like any good Amphitryon, you orchestrated that evening so as to include dinner and a show: 7:30 PM at Chefs Club in NoLita followed by a 10:30 PM engagement at The NoMad Hotel in the neighborhood of the same name. The mere two-mile journey seemed totally surmountable: you’d whisk out of dinner well-fed, catch a cab uptown, and settle into your seats for the show with enough time for a digestif or two.

If Hasegawa’s star was rising at that time then also, surely, was Dan White’s. His show—“The Magician at The NoMad”—had been staged for a little more than a year. It was already a tough booking at the time and was soon to become nearly impossible as its star illusionist racked up appearances on late-night television. With bowls of truffle popcorn and beverages by way of The NoMad Bar (ranked eighth in the world at that time—and number three just a year later), the show was every bit as estimable an occasion as Den’s pop-up dinner.

Hasegawa’s dinner at Chefs Club was staged around an open kitchen. Communal tables spanned the circumference of the room, with diners seated adjacently so that staff could move about the center space and present food. The chef was joined by his wife and several other members of Den’s team, imbuing service with some genuine sense of the restaurant’s hospitality (versus guest appearances in which the visiting craftsperson expresses themself principally through the creation of the menu). Hasegawa’s earnestness was absolutely charming. Though unable to convey much in English, the chef’s relationship with his staff imbued the evening with an indelible spirit.

The cuisine, of course, was no slouch either. Den brought along several of the party tricks that had, no doubt, endeared the restaurant to international visitors even in those early days. Apart from those now-familiar set pieces, the menu struck you with a sense of whimsy words away from the cliché of the stoic, traditionalist “Japanese chef.”

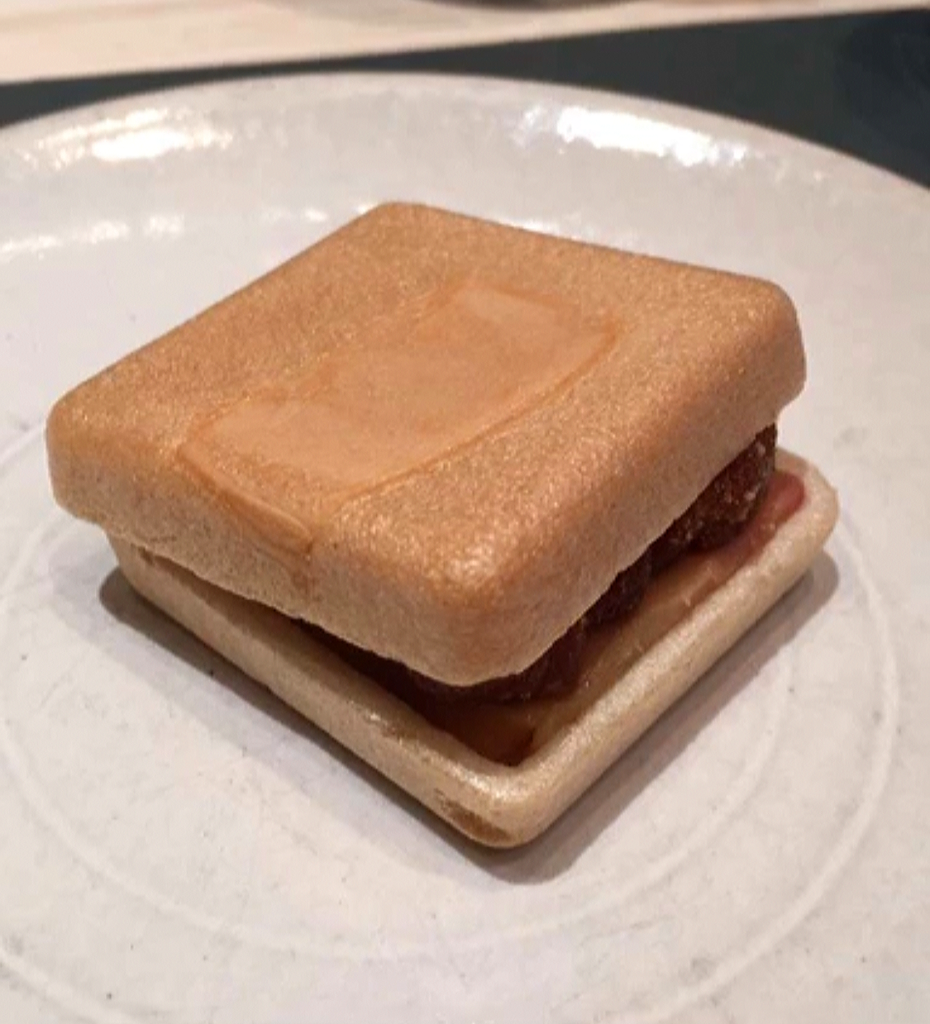

To begin, Hasegawa served a “Monaka”—or wafer sandwich—filled with foie gras and pickled radish instead of the traditional azuki bean paste. “Texture” comprised tomato jelly “noodles” laced with basil and bits of fruit. “So Good,” as one course was called, featured the chef’s signature “Dentucky” stuffed chicken wing served in a custom container on which he does his best impression of the Colonel. And “Garden,” as another dish was titled, looked every bit as verdant as the name implied. It was made up of more than 20 different vegetables prepared in a variety of ways and scattered across a cutting board. The layered assortment of lettuces, herbs, and flowers—accompanied by the odd peapod, carrot, or cucumber—made for lush, naturalistic scene that lived up to the item’s namesake.

The dinner’s pacing had been superb as you reached the penultimate course. The fare was complex and engaging but relatively forthright. It had not demanded the kind of extended preparations or presentational flourishes that ate up valuable time. Moreover, Den’s team operated with a mutual understanding that enabled several pairs of hands to harmonize any given plating. You looked forward to Hasegawa’s savory finale, a bit of dessert, and a timely departure that would transition swimmingly into that evening’s entertainment. You felt like the consummate host, the master of those shifting sands of time that—when perfectly managed—yield a given night out its enchanting sense of energy and intoxicating “flow.”

“Japanese Flavor,” that penultimate dish, would surely entail a bit of wagyu beef—or something like that—and you’d be on your way. Maybe, you mused, that extra tipple from NoMad Bar would come to fruition and wet your whistle before the magic began. But Hasegawa and team’s flurry of activity had suddenly ground to a halt. The interlude from the arrival of “Garden” to that of this last savory course quickly grew to be longer than all the gaps between the preceding dishes combined. And yet the kitchen seemed wholly at ease. They chatted and laughed amongst themselves and with some of the familiar faces in the crowd. Over time, it became clear that the chef was keeping an eye on one of the ovens. Its contents had been left in the care of one of Hasegawa’s friends, a peer who had also come from Japan to cook alongside the Den team.

As the chef and his wife continued to work their away around the room, you spied the oven opening. Hasegawa’s friend removed a hunk of meat and proceeded to massage every bit of its surface with an unknown seasoning. Though easily pushing 8-10 lbs., the cut bounced and jiggled as it was rubbed. That supreme display of tenderness made your mouth water even as the showtime ticked ever nearer. “So, you won’t have time for that additional drink,” you thought, “but surely the final savory course was now only seconds away.” However, after its spa treatment, the hunk was not yet ready for a sharp blade. Hasegawa and his friend loaded the meat onto a cutting board, draped it with leaves, and paraded it proudly around the dining room so that guests could appreciate the splendor of its well-develop crust. The chef at last revealed the piece was a saddle of Texas lamb that had been cooking since 9 AM. By your calculation, that added up to 10 hours—and also meant you now only had 15 minutes to spare.

The lamb’s butchering was a work of art. Rather than portioning and then slicing straight through the hunk of meat, Hasegawa’s friend kept the saddle whole, peeled back its skin, and carefully removed the tough intramuscular layers separating the various sections. Then, he sliced the primest strips of glistening, medium-rare flesh from the very center of the cut. They would be briefly soaked in a pan filled with the lamb’s drippings, plated, and then garnished by Hasegawa.

Nerves beginning to set in, you finally received your plate: a beautiful piece of lamb rump accompanied by crunchy roasted parsnip. You gobbled the serving up—a task made easier by the meat’s superlative tenderness. But what influence could you hope to have on the other diners? They’d surely need to finish eating before you could even think about dessert. Maybe, just maybe, you’d be able to scarf down the sweet and head straight for the door. The plate that held the rump was cleared, and it seemed as though things might conclude according to plan. But—with a mixture of horror and delight—you saw that more meat was being portioned.

Next arrived a slice of the lamb’s loin served with potatoes cooked in vegetable ash. You eyed your fellow diner—also well aware of the time crunch—knowing a decision had to be made. The second plate of lamb got cleaned even faster than the first. (Of course, the loin was even more wonderfully tender than the rump). You began to stir, checking that you had all your belongings and foreseeing how you might make your flight. (The private event format was a godsend—ensuring that the cost of the meal and pairings had been paid ahead of time).

At just the crucial moment—when you had worked up the nerve to excuse yourself—Hasegawa’s friend spied your empty plates. Noting how ravenously you enjoyed his handiwork, he deposited two more succulent strips of lamb before you. In any other circumstance, you would have been smitten by such generosity. However, as it stood, the hunk of lamb proved a perpetual, insurmountable impediment.

You sent your dining companion off to go “to the bathroom” and make an inconspicuous exit. He could hail a ride while you stuffed your face with two more servings of meat. Then, licking your chops, you paused just long enough to feign that you, too, were only stepping away to use the restroom. Head down, eyes averting the kitchen, you skulked towards the door feeling all the ignominy of a dine-and-dasher. Surely the parties seated adjacently would soon recognize the dual absence. The Den team would notice too. Or maybe they would move forward preparing dessert—their signature “Star Comebacks Den” custard pudding in a coffee cup—only to learn there’d be nobody there to eat it.

Would it have really killed you to notify even just one member of the staff as to your exit? Surely, they could understand the reality of another commitment. You suppose it felt ruder to rush the visiting chef through a confused, halfhearted goodbye rather than preserve his focus on the dinner at hand. There could be no question that you enjoyed your food—including but not limited to those four total servings of lamb. And you made what, in retrospect, seems like the fairest tradeoff: skipping the final fifteen or twenty minutes of dinner to ensure your presence at a two-hour performance demanding your prompt attendance.

Still you would feel tremendous guilt if your “disappearing act” caused Hasegawa, his wife, and the rest of his visiting team the slightest offense or concern. Would they, could they know it was you should you show up at their doorstep in Tokyo? Do you deserve such a coveted reservation after demonstrating such flagrant disrespect? Surely, you would savor the chef’s food all the more without the weight of another commitment on your mind.

But, as a host, you can only look back on that Chefs Club meal with bemusement. For your exit was the sort of foible immediately forgotten by everyone save for you guest. And, more than either Hasegawa’s menu or Dan White’s magic, the farcical departure is what you reminisce about most from that evening. You’d otherwise scarcely remember what were, really, two fantastic events that night—your nostalgia stoked by the sort of thrill that only a shared flouting of etiquette can provide.

A Second Disappearing Act at Next

As a coda to the prior story, you recall one more occasion when you suddenly disappeared from the table in order to attend a magic show. It was 2018—two years after the Den incident—and you had reserved one of Next’s Alinea Retrospective meals at 5 PM ahead of a 7:30 PM show at the Chicago Magic Lounge. Though certainly a narrow window of time to negotiate, you learned from your past mistake and informed the restaurant’s general manager of the other commitment immediately upon your arrival. His response was something like “we can bring out the courses as fast as you can eat them.”

Up to the challenge, your party of four did their part scarfing down the food—the women at the table switching plates with the men after a couple bites to expedite the process. But Next’s kitchen—doing their best to replicate big brother’s molecular fare—could not live up to their end of the bargain. Each dish took the usual 10-15 minutes to arrive. It was almost as if the manager had not actually communicated your situation to the chef.

At 7 PM, with a couple more savory courses to go, you informed a different manager that you had to leave. He begged that you stay just five more minutes and went about scrounging up the menu’s headlining wagyu dish and a couple of the desserts all at once. Finally, it seemed like all hands were on deck working to fulfill your request. But, after those few more bites, you still had to leave.

You made it to the Magic Lounge on time, confident—once more—that the completion of the meal simply had to be sacrificed for the sake of the overall evening. But you felt let down by Next’s general manager. Was he too proud to really believe that you expected the kitchen to cook in accordance with your schedule? His restaurant might not offer a “theatre menu” per se, but you would have gladly excised certainly portions of the meal in exchange for a smooth experience. However, he left the kitchen in the dark and assumed that the menu’s general pacing could match your party’s demand. Rather than smoothing your request over, his devil may care attitude ensured that the back of house suffered the shock of a party suddenly walking out.

You felt bad for the kitchen and for the other manager who actually picked up the pieces and tried to salvage the situation. Had the general manager taken ownership of the experience from the start, everyone’s blushes could have been spared. Perhaps, operationally, it is simply not Next’s policy to honor such requests. But the G.M. should have known some disturbance was inevitable even if his hands were officially tied. He should have struck upon a solution—no matter whatever sacrifice had to be made with regards to the menu and pairings you had already paid for—but instead assumed you’d stay seated and bear being late.

It was the wrong assumption, and it made you feel as if he’d forced you into making a much ruder gesture than was necessary to assert the magic show’s primacy over the tasting menu that evening. The reaction of his colleague—who, by all accounts, came to the rescue—demonstrated that the food could, indeed, be rushed to some degree. It was only through the other manager’s actions that you felt Next actually desired to serve as many courses as possible rather than punish you for your “transgression.” You are thankful that the latter manager remains at the restaurant while the general manager—having irreparably damaged your relationship through his incompetence that evening—would ultimately leave a couple years later.

(Nearly) Falling for the Scenery at NoMad

Years after you left Chefs Club early to attend The NoMad Hotel’s upstairs magic show, the latter establishment played host to a rather daring environmental gaffe. The building’s beautiful library formed the scene. It was a well-appointed space where—during the morning—hotel guests and visitors can sip coffee as they clack away on laptop keyboards. Later in the day, patrons could grab a nip from NoMad’s downstairs bar as they usher in the start of the evening’s festivities.

However, as enticing as the libations offered there were, The Library’s popularity was principally a testament to its interior design. The room was appointed with antique rugs, tufted leather sofas, armchairs, rocking chairs, and hanging lamps. The floors, tables, and walls were done in polished dark wood. Blinds covered the doors and windows at The Library’s street-facing wall—ensuring the daytime glare (and the glares of passersby) didn’t spoil the mood—while a second-story set of windows—unobscured—served to remind guests what city they were in. But the room’s centerpiece, without any doubt, was the spiral staircase that connected the two levels of shelving boasting everything from matching volumes and antique tomes to coffee table books and contemporary fiction. The space did not simply wrap itself in intellectual trappings for the sake of a photo-op—it was a functioning library and a celebration of an archetypal literary luxury.

Though you had eaten at The NoMad Restaurant many a time while residing nearby, it was only later on—as a traveler to New York and guest of the hotel—that you found your way to the library. As a terminally longwinded person, you were immediately smitten by the prospect of being surrounded by so many books filled with so many words. (What is luxury if not a means to confirm our self-definition?) The space indulged the fantasy of being an intrepid, eclectic man of letters moored—for just a moment—in the comfortable confines of his manor estate. So you’d call down from your suite and ensure the hostess had a table ready. And there you’d enjoy coffee and juice before brunch, afternoon cocktails ahead of a nap, and pre-dinner libations with a snack or two to buffer the serious drinking to come.

After a couple days of acclimating to your new haunt, the urge struck to make yourself more at home. While waiting on drinks to arrive, you’d step away from your guests and browse the stacks with all the bearing of the Librarian of Congress. You’d choose some imposing volume that tickled your fancy and bring it back to the table, balancing the book on your knees. With your cocktail before you—perfectly perched to deliver the occasional sip—you could flip through the selection while remaining slightly, nobly removed from your friends’ tabletop chatter. “Look at him, the aesthete, insatiable in his quest for knowledge,” some onlooker no doubt thought. “Look at how he rises above the blabbering and posturing that otherwise taints such a civilized space,” mused someone else you are sure.

Appearances aside, you found it charming to embrace the library space as such: good design should be functional, should possess depth, rather than aspiring to little more than a movie set semblance of reality. The Library’s books, as best as you can remember, were little more than glorified props chosen for their jackets’ Francophilic appeal. But they were real, and perusing them helped you whittle away the time between engagements while avoiding the summer heat. Not to mention, the books’ tactile nature kept you from sipping an inordinate amount of caffeine or alcohol merely to occupy your hands.

Eventually, having exhausted all the appealing tomes from the library’s first-floor shelving, your sights set naturally on the spiral staircase and the selections cloistered up above. Could there be a greater thrill than—after familiarizing yourself so thoroughly with the space—making use of its showpiece? The beautifully sculpted steps laid in the corner just a few feet behind your central table. No guests were seated at the adjacent couches, so your sojourn in search of further reading material surely would not disturb anybody. And, hey, maybe your engagement with the room’s signature element would inspire the other assembled patrons to do more than bury their heads in their laptops.

With great pomp, you rose from your chair and strut towards the staircase awash with the grandeur of the moment. What treasures did NoMad keep stored away on the second floor? Just how did they reward those discerning enough to embrace the climb?

The delicacy of the wooden steps struck you immediately as you felt the impact of your ascent reverberate through the spiral’s frame. “What exquisite one-piece craftsmanship,” you thought, “no doubt lending to the fixture’s slight profile.” Reaching the top, you realized that the second-floor railing extended through the staircase’s opening—effectively blocking any passage. You looked for a latch that might swing the gateway open, but to no avail. Yet the railing only reached your knees—could it be that the librarians of yore simply swung themselves up and over like saloon bartenders?

Undaunted, you crossed the threshold and found yourself on the narrow platform that circumscribed the library’s second story. It could just about fit your width and—thankfully—showed no signs of buckling. The railing maintained the same meager height. Would it really be enough to catch your fall? Or would were you destined to smash through one of the tables below?

At this point, you were totally committed to the trapeze. Scanning the stacks—but not venturing very far—you realized the selection was total rubbish. Filler, meant only to extend the illusion that the first floor’s collection comprised only a small bit of the total assortment. It was all a bit of Disney trickery, the same sort used on Main Street, U.S.A. (where the second and third floors of the various buildings get smaller and smaller despite seeming as though they extend the same frame). That, perhaps, explained the short railings and narrow walkway. No wonder, then, the spiral staircase seemed unequipped for actual climbing. It was ornamental, evocative, and, ultimately, led to nowhere.

Aware that your idiocy was now fully on display, you sheepishly slid back over the railing and made a tiptoed descent down the stairs. Thankfully, the assembled patrons still seemed absorbed by their screens. You caught no glares save for the snickering of the guests at your table. That ridicule from your friends, surely, you could stand. But they revealed that a member of the staff stopped by the table—no doubt while you feigned interest in the titles stocked up above—to inform them that you were not to be up there.

It took great restraint and tact not to immediately shout at you to climb down—and, thoroughly mortified, you did not dare even touch one more of the books for the remainder of your stay.

Safety Testing the Lobster Supplement at Shuko

When Nick Kim and Jimmy Lau’s sleek omakase/kaiseki bar opened in 2014, it immediately shot towards the top of New York’s nascent sushi scene. Shuko—along with Nakazawa in 2013—paved the way for a broader appreciation of the craft. Yes, Masa had occupied his position at the city’s summit since 2004, and other itamae had humbly served enthusiasts for decades. Yet these new bars were sleek and sexy. They subverted tradition with what might be termed gimmicky today. But—buttressed by plenty of media hype—they birthed a new generation of sushi aficionado. They taught Americans the ropes with a wink and a smile, ushering in the present era in which New York boasts some of the best omakases in the world.

Looking back now, Shuko—in the summer of 2015—might just have been the first “serious” omakase you ever tried. In the weeks that followed, you sampled Soto and Nakazawa. In the years that followed, you would climb the hierarchy of KOSAKA, Kajitsu, Ichimura, Ginza Onodera, and AMANE—reaching Time Warner Center’s promised land, too, on a couple occasions. But Shuko was the first, and the hybrid stylings of two Masa alumni proved a rather perfect place to start what has proven to be—for you—the final frontier of culinary connoisseurship.

Of course, given your appetite, it helped that Kim and Lau offered more than just an omakase at their bar. The duo offered—for $40-$45 more—a “Sushi Kaiseki” that appended milk bread (with caviar), sashimi, robata, wagyu, and dashi onto the standard serving of nigiri and hand rolls. The extended menu also included that showstopping, all-American conclusion to the meal: miso-accented apple pie with bay leaf ice cream. While the extra courses necessarily dilute guests’ technical appreciation of the actual omakase, they also pad stomachs and help ensure an overall sense of satisfaction. Such a strategy is employed in Chicago at Mako—though far more insidiously, given that B.K. Park wedges cooked dishes in between flights of congealed nigiri in a bid to obscure his sushi’s poor quality.

On top of either the “Sushi Omakase” or “Sushi Kaiseki” menus, Shuko also offered a range of supplements. These could be added to either meal and comprised items like Miyazaki ribeye ($50), a “Drop the Mic” roll of uni, caviar, and toro ($28), or a piece of kama-toro—or tuna collar—nigiri kissed with a hot coal ($20). Relative to the premium paid for the kaiseki-length menu, the supplements compartmentalized the most luxurious bites so that interested diners need not sign onto an overwhelming amount of food. In fact, items like the Miyazaki ribeye could even seem somewhat redundant to those who chose the extended menu—which already featured a different cut of wagyu.

But the prospect of such a beefed up “omakase” experience was infinitely appealing in those early days. The $175 kaiseki could become something like a $300 extended tasting menu when all was said and done. And the heart of the matter—the actual sushi—could slowly seduce your palate without being forced to resolve that all-important question of fullness.

By your third or fourth visit to Shuko, you were well in the habit of tacking the whole kit and caboodle onto your kaiseki. On that occasion, you noted a new supplement: “Spicy Lobster.” For $25, the dish combined tempura-fried pieces of the titular crustacean with green onions, white onions, and lotus root. The source of the “spice” was not immediately obvious. Perhaps it was drawn from a housemade chili oil.

You see, in the sepia tint of Shuko’s hip hop soundtracked sushi bar, your appraisal of the dish was not exactly clear. The space is amply shadowed, ensuring that the wooden counter which forms its centerpiece becomes something of a stage. The lighting doesn’t demand one strain their eyes to identify this piece of nigiri from the next. But it falls firmly into the moody, romantic category—a fitting aesthetic for an omakase that has long sought to distinguish itself from the city’s starker expressions of tradition. When Kim or Lau bust out the blowtorch to sear a piece of tuna, the whole room revels in the glow. When the chefs craft just about anything behind that bar—even milt—it is easy to take the leap on a new ingredient due to the “show.”

However, a cooked item like the “Spicy Lobster” supplement—prepared in an unseen kitchen then deposited, from behind, in front of you—strikes differently. On that evening, it appeared with only a simple announcement as to its identity. You could note at least one glistening nugget of the lobster tempura, but the bulk of the dish was covered under a pile of the green and white onions. The lotus root—also beautifully crisped—formed something like a crown that further obscured the serving of crustacean.

You popped that first piece of lobster into your mouth and reveled in the crisp coating, moist interior, and well-managed burn the of the chili oil. Delighted with the intensity of flavor, you dove right into the interior of the dish. Grabbing the lotus root, a tangle of onions, and another piece of the crustacean, you braced yourself for the power of a fully-composed bite. The many layers were pleasurably crisp. But something was a bit crunchy. Could it be a particularly thick bit of raw onion? A starchy section of the lotus root? The tender lobster meat was certainly still there, but its texture was somewhat being overshadowed.

With further chews, the “crunch” turned into a “crack.” It positively crackled, and—still a bit confused as to what exactly you were sensing—you pressed onward until it became embarrassingly clear that you’d nearly pulverized an entire segment of the lobster’s shell. Faced with a plate that was still mostly full—and the prospect of spitting out an entire mouthful of food into your napkin—you concealed your expression as best as you could and pressed onward. But the crunch of the crustacean’s carapace was certainly loud enough for the chef before you to notice. And the slow realization of what you had done was rather plainly expressed on your face.

The chef—and, thank heavens, he was only a sous chef—spared you any comment that evening. But all further orders of the “Spicy Lobster” supplement were introduced with the warning to “watch out for the shells.” And, though the figure delivering the dish would change from visit to visit, you felt the proclamation came paired with a knowing smirk.

You cannot regret the enthusiasm with which you dove into the preparation that first time—even if it turned you into a guinea pig on behalf of subsequent guests. The staff’s good humor, as always, ensured the ordeal was little more than a crunchy “bump in the road” among many enjoyable omakase journeys in the years that followed.

A Spectacled Hindenburg

While you feel a bit silly for having played your part in reminding Shuko customers not to eat lobster shell, you formed the genesis of another, more worthy, warning at a different restaurant.

Alinea, your favorite punching bag, formed the scene. The year was 2016, which saw the dawn of the restaurant’s “2.0” era following its ten-year anniversary and renovation. For five years—until the pandemic struck and ushered in the “3.0” chapter upon Alinea’s 2021 reopening—Grant Achatz, Mike Bagale, and Simon Davies forged a cuisine that drew on spectacular ambient effects to frame the establishment’s mind-bending molecular fare.

Rather than staging countless, identical menus throughout the entire space, the restaurant’s new downstairs “Gallery” could offer a half dozen tables a shared, superlative expression of hospitality. There, the presentation of a course might start at the individual table but—through light and sound—grow to encompass the entire dining room. Guests might not interact much directly, but they shared in the “show.” Their experiences melded into that of a cohesive “audience” for which the staff tailored the totality of their movement and coordinate the evening’s flow.

You have often derided your “2.0” Gallery experiences as “smoke and mirrors” cuisine. At your most extreme, you have branded the entire concept as little more than a big-budget Rainforest Cafe rip-off. But, truth be told, many of the novel effects were charming at first. They would remain—as far as the restaurant’s revolving door of first-time customers was concerned—utterly unique. Yet you came to feel that the ambient elements dominated the appreciation of the food as such. Alinea’s dishes did a good job of partnering the given tableau, but they did not excel in terms of sheer flavor or texture. In that respect, the kitchen’s experimentation was in no way beholden to offering pleasure, for customers were assured to get lost in the overarching performance. Courses that were merely pleasant or intriguing escaped criticism when subsumed into such a spectacle. And the promise that “Chicago’s greatest restaurant” might serve some of the city’s most delicious food always went unfulfilled.

Now that Alinea “3.0” has renewed the restaurant’s prioritization of each dish’s internal—rather than external—logic, you can look back on the “2.0” era with a bit more nostalgia. The stagecraft you witnessed from 2016-2020 was, indeed, like nothing Chicago dining had ever seen. With a sense of visual flourish well-suited for social media content creators, Alinea captured the imagination of a surging population of consumers who might not have ever considered spending “concert ticket” money on a dinner before. The restaurant subverted fine dining’s snobbish association with etiquette and expert knowledge by advertising an experience that was impossible for patrons—no matter how expansive their taste—to parse. Achatz spurned any sense of rootedness (in the local terroir) or nostalgia throughout the menu for the sake of making new memories that were equally accessible to all. Had the chef struck upon any signature savory preparations that could measure up to “1.0’s” Black Truffle Explosion or Hot Potato / Cold Potato, he might have succeeded in reinventing the restaurant.

Instead, you are only left with some semblance of many evenings that played out like high-priced dinner theatre. One grand table would transform into many small ones upon a trip to the kitchen. Cauldrons would bubble, ingredients would come down from the ceiling, and musical interludes would enliven the space. Food would be hidden in plain sight. Maybe it would arrive sizzling on hot stones. It could sit at the center of a gargantuan plate. Or perhaps it would just be presented and portioned tableside. Any delight was always skin-deep: a memorable meal in which one struggled to say exactly what they enjoyed tasting. But why break your back crafting incomparable flavors when it’s so much easier to serve “fun”?

No dish epitomized that philosophy more than Alinea “2.0’s” unabashed totem: the “edible balloon.” The whimsy of the creation earmarked it as a viral sensation from the start. Its appearance towards the end of the meal—the effect its consumption had on the rarefied, dignified dining room—was a bit of genius. Its presence unbeknownst to the diner, the helium inside the balloon subverted the very notion of fine dining as a serious affair. By enforcing a certain level of silliness, the restaurant—in one of “2.0’s” rare instances—tapped into childhood nostalgia. It empowered each table—no matter the extent to which the party knew each other—to bond via the shared vulnerability of a raised vocal pitch. The “edible balloon” made for one of the most memorable moments ever conjured in a restaurant—and it did so while offering little more (in a gustatory sense) than the familiar flavor and texture of fruit taffy.

Forging an indelible food moment in which the comestible forms little more than a vessel for what is essentially a social experience? Lampooning the very notion of fine dining as a stuffy affair while denying that a dish need satiate? Reducing well-heeled diners, clad in suits and skirts, into giggling children? The word “genius” comes to mind, and the “edible balloon” is a real feather in Alinea’s cap. You trust that the creation will grace the restaurant’s menu once more—no doubt, like the retired “Black Truffle Explosion,” when you least expect it. And perhaps, then, the charm will be renewed. For the balloon formed a delightful part of the meal when hosting first-time guests, but—years on—it struck you as just one more dainty, disappointing dessert that concluded the meal with little more than a fizzle.

However, back in 2016, Alinea’s floating food was all the rage. You remember the early days when the “edible balloon” still came with a metal anchor. Later, the kitchen would imbue its “string” with enough weight to excise the bollard and brand the dish as “totally edible.” But it still needed to be approached in just the right way. Time being of the essence, instructions were given to kiss the balloon and form a seal from which the interior gas could be sucked. As the shell deflated, the taffy would clump together and coat your lips and face—and the dangling string could then be slurped up like a noodle.

There was something childlike and nostalgic about all that stickiness—like the sensation one got when diving into a cone of cotton candy with reckless abandon. Yet, by providing customers with hot towels, the restaurant could cleanse any remnant of the helium gag and make an orderly transition to the closing chapters of the menu. The meal’s crescendo, in that way, was expertly managed. It’s amazing that Alinea was able to craft and coordinate such a superlative moment with nary a hitch. Though they had a little help.

By the third or fourth time you faced the “edible balloon,” you had become a bit bold. Thoroughly comfortable in the manner of approach, you’d plant your kiss right away, inhale as much of the helium as possible, and broach—for the sake of The Gallery’s assembled guests—being the first to unleash your mousey cartoon character voice in the space. Many of the friends you hosted, too, were sheepish about the helium’s effect in their own way. The sort of person who dreads hearing their voice recorded would likely be just as averse to the attention a higher pitch draws. So, by braving the embarrassment first, a host reaps the added benefit of inducing their companions to share in the same ritual. They need no longer fear sounding silly but, rather, look to avoid seeming too serious to indulge in the farce.

As if being the first to pierce the tranquility of the dining room wasn’t enough, you soon became so adept at handling the balloon that you’d record yourself eating it. The item’s limited lifespan meant that guests could normally get only picture or two before turning their attention towards its consumption. But you combined both processes into one incredible “selfie.” With your phone outstretched in one hand, you’d use the other—clutched onto the string—to maneuver the balloon towards your mouth while keeping your face in frame.

The delicate process went off without a hitch the first time—though the footage it yielded was totally subpar. Was it even worth eating at Alinea if you could not broadcast your enjoyment of its most titillating item? So you doubled your effort the next time. Confident in your ability to wrangle the balloon towards your mouth with one hand, you kept your eyes trained on the screen of your phone to ensure you were staging the perfect shot. The floating taffy coasted towards your head from stage left. You turned to plant your showstopping kiss only to have the frame of your glasses puncture the balloon at the crucial moment. The taffy deflated and enveloped your lenses to the extent that you could not see. The footage you had taken—interrupted by the catastrophe—only showed the moments leading to your moronic mistake before the camera suddenly spun towards the ceiling.

Removing your glasses, you salvaged the string and whatever bit of the taffy could be eaten. The lenses themselves demanded not just a hot towel, but multiple alcohol wipes and a microfiber cloth to restore their clarity. At your table, the usual shared moment was substituted for peals of high-pitched laughter aimed at your stupidity. (In truth, the combination of legitimate humor with your guests’ affected voices was even more delightful). You bore the ribbing but were greeted shortly by another balloon from the kitchen.

Graciously, that second time, you enjoyed the dish as intended without any lingering desire to broadcast the moment. Alinea, to their credit, not only rescued you from your idiocy. They warned, on every future occasion, that guests should remove their glasses before enjoying the “edible balloon.” (Though, looking back today, you think it just to “burst the bubble” of diners who carelessly remove themselves from the moment for the sake of social media. At the very least, the resulting blooper does more to entertain than a video of mere craven conspicuous consumption).

Le Bernardin’s Camera-shy Busser

While some members of NYC’s French old guard—like Daniel and Jean-Georges—have fallen, Eric Ripert and Maguy Le Coze’s ode to the cuisine of ocean remains one of the nation’s few timeless, faultless temples of gastronomy. Le Bernardin is not only held in the highest esteem by the chef’s countrymen, but it is wildly popular with discerning gastronomes from China and Japan (no slouches when it comes to appreciating seafood either). Thus, especially before the days of online reservations, you always treasured securing a Friday or Saturday evening reservation. The process was always made all the more charming by conversing with the establishment’s longtime reservationist, one of the most tender and personable you had ever dealt with.

To your taste, Le Bernardin’s food always struck you as a bit dainty during the years you consistently ate there. Perhaps it was too “refined” or “subtle” for you palate at the time. But the compositions themselves were stunning in their simplicity and imaginative in their plating. Every detail of the restaurant oozed class. It embodied an understated luxury free of ostentation. It championed a hospitality that—no matter how rarefied the dining room—was sincerely felt whether you were a weekly regular or traveling first-timer.

Despite knowing you might be destined for a midnight snack, you’d feel delighted every time you walked through the doors. Merely sitting within the space was enough to send a chill down your spine. Le Bernardin’s dining room was not cloistered like Per Se or Daniel. It did not hide in plain sight on a corner of Columbus Circle like Jean-Georges.

Ripert’s restaurant was an oasis on a busy street near Broadway. It felt like “somewhere,” but not in a way that stood apart from reality. The dining room had carved a place for itself among the bustle of the city. It stood as a promise that—just on the other side of that door—superlative hospitality could transport you towards a deeper appreciation of life. “Luxury” could be an everyday occurrence—not the luxury of tuna, caviar, and urchin, but of thoughtful, nurturing service. In their earnestness, Le Bernardin’s staff stood as shining examples that great meals are built on humanity and not vanity.

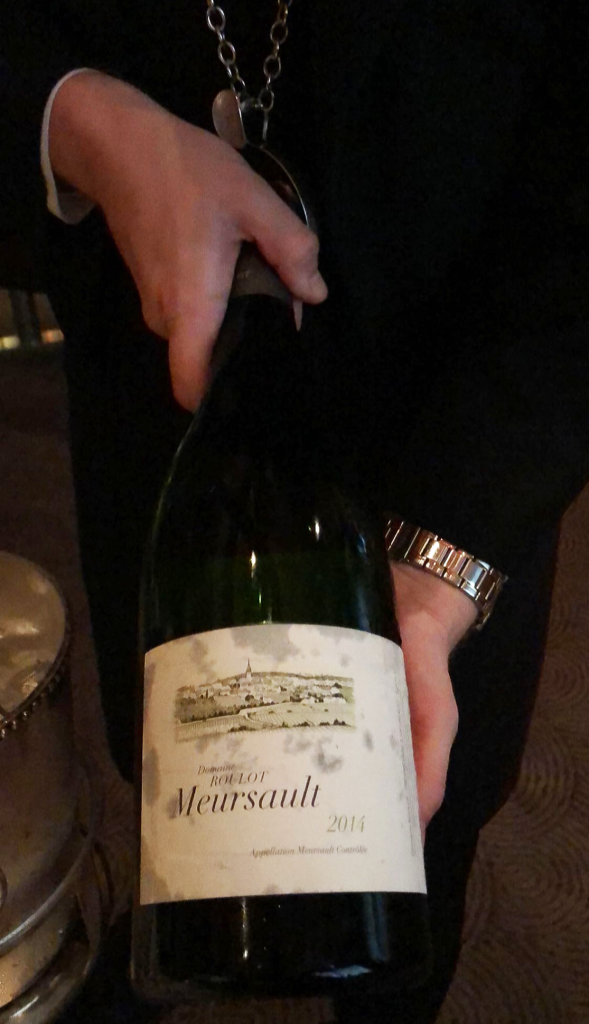

So, even if you thought the Chef’s Tasting Menu would leave you wanting, you looked forward to an excellent experience. For you would surely encounter Aldo Sohm’s incomparable wine list—the magnums of Domaine Roulot’s Meursault being a routine splurge and a heavenly accompaniment for Ripert’s fare. You would find a bread basket overflowing with options and replenished—along with your butter—as many times as desired. And you would interact with a staff empowered to please, be that allowing you to append an additional course of oysters onto the tasting, to enjoy both cheese and dessert (instead of choosing just one), or to simply sample all of the dessert options to conclude the meal.

Le Bernardin’s lofty reputation was not wielded in such a way as to quash special requests (in deference to how “things have always been done”). Guests were not expected to worship at the altar of Ripert. Rather, the restaurant’s reputation was earned anew each day through faithful devotion to delivering upon each guest’s desires to the best of its ability. One sensed, in each interaction, a sense of graciousness and understanding that welcomed you to put the establishment at your service. They would do their best to accommodate you without any trace of resentment. Not only that, their service would burn brighter with the knowledge they were providing you with some special pleasure. As far as classic European hospitality is concerned, you cannot think of a higher expression of quality.

Of course, even the most renowned restaurants are allowed a hiccup. Perhaps you’d term it a misunderstanding. But it stands as the rudest interaction you have ever had with any member of any restaurant’s staff. And the incident reverberated all the more due to the usual, unflappable standard Le Bernardin’s hospitality had set.

Your usual table at the restaurant was one of four central banquettes that laid just past the floral arrangement in the rear of the dining room. You typically ate there as a party of three, and it suited you well to occupy the lone armchair while your guests cozied up on the plush leather bench. An ice bucket fit nicely by your side—allowing you to gaze lovingly upon those magnums of Meursault—and the seating ensured you had a clear sightline to the nook from which servers entered and exited the kitchen. Thus, as each fresh basket of bread came out, you could hail its carrier and get first pick of the litter.

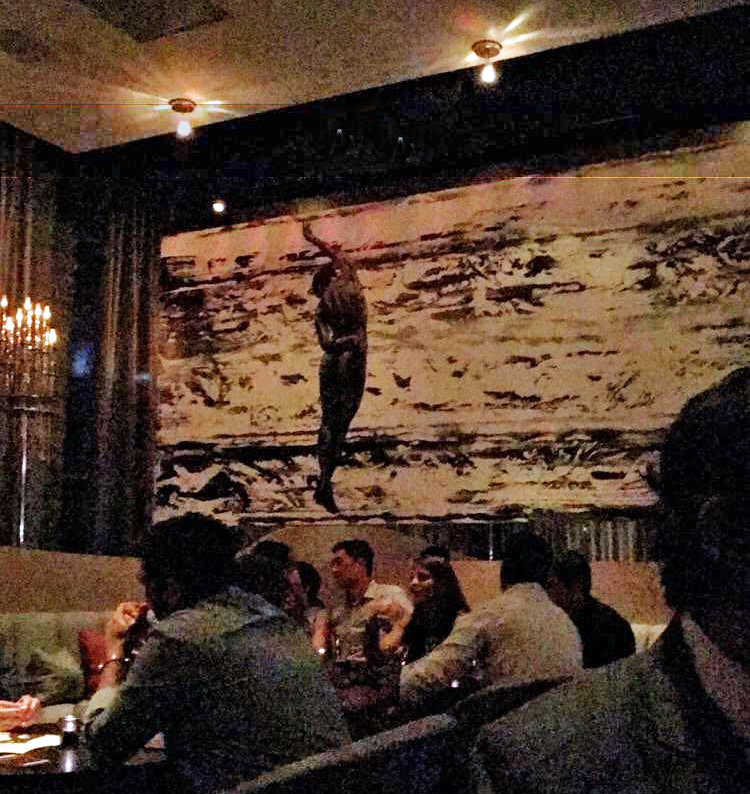

That coveted table also enjoyed a prime view of Ran Ortner’s Deep Water No. 1, the six by twenty-four foot triptych oil on canvas that has come to define Le Bernardin’s dining room since its installation as part of a 2011 renovation. From afar, the painting’s crashing waves play off of the white tablecloths and gleaming crystal to help invigorate the warm wooden accents and dark leather tones that ground the space. But, towering above and across you, Ortner’s piece is absolutely intoxicating. The detailed froth and ripples remind you of the ocean’s lifeforce. The sharpness of the waves captures its power. The subtle blend of blue, green, and white tones speak to its ephemeral nature. The whole effect makes you feel small. It makes you feel damn appreciative to be eating Ripert’s sustainably-sourced seafood. And it underlines a sense of purity and harmony that reverberates throughout the entire restaurant.

Deep Water No. 1 forms one of the rare totemic visual elements you associate with a restaurant. The best other example you can think of was the suspended sculpture of gold-painted Manzanita branches positioned as L2O’s centerpiece back in the day. But, in Le Bernardin’s case, it could be no surprise that your guests enjoyed being seated in the shadow of such a signature piece. They could not be faulted for snapping a picture—or perhaps filming a short panorama—that captured the triptych’s gravitas, that framed the incredible dining experience they were surely having.

One evening, in the spring of 2017, you were seated in your trusty armchair and the guest across from you in the banquette decided to take one such picture. The meal had been proceeding swimmingly up until that moment. You were, you think, around the midpoint of the menu. And you paid little mind as your companion—the flash on their camera, of course, turned off—swept her lens to the furthest end of the painting to maintain some sense of its scale. She took her snapshot and returned her attention to the table.

Just a moment later, one of Le Bernardin’s bussers—sharply dressed in all black—approached the party. You were so sure that—having spotted your guest’s camera in use—he was going to kindly offer to take your group’s picture. It slowly dawned on you that the busser was livid. The smile you naturally don in service encounters melted into a look of bewilderment. The interloper’s African French accent stung with its sharpness. Still, he maintained enough restraint to avoid attracting the attention of any other staff or diners.

The busser—who, you came to understand, was positioned at the service station to the left of the painting—chastised your guest for having taken a picture of him. He repeated two or three times—emphatic in his indignation—that he did not like having his picture taken as the “culprit” stammered that she was only attempting to capture Ortner’s work. But there was no discussion to be had—no soothing a man who was sure he had been the object of the photo. He made his outburst and returned to his duties. The three of you at the table were absolutely stunned.

Surveying the photo, the man did indeed appear in the frame but was hardly its focus. Deep Water No. 1 undoubtedly formed the object of attention, the corner of the dining room and sliver of the busser and the service station only included—as previously mentioned—to offer some sense of the painting’s scale.

You toyed with calling for a manager, but what would that accomplish? The busser had clearly been traumatized before in some manner. His rant jarred your experience, but he was sincere in feeling objectified—even if mistakenly. Whatever offense you might have felt in being needlessly shamed was moderated by the busser’s discretion in doing so. The table was left feeling confused, bemused, and apologetic for having upset the man even unintentionally. Pleading your case to management, providing the corroborating photographic evidence, and strongarming some kind of apology from him seemed cruel. Confident that your guest had no intention of photographing him, you could only bear the misunderstanding and enjoy the rest of your meal.

The incident never factored into your future visits to Le Bernardin. It did not even embitter that particular experience. Looking back now, you have a hunch as to why the busser might have reacted the way he did. The guest who took the photo was ethnically Chinese, and those in China routinely objectify Africans. That extends to “snapping pictures” of them, and—given Le Bernardin’s popularity among international tourists—the busser might have been exposed to that particular vulgarity before. Such an explanation implicates the man in committing his own sin of superficial judgment. But it goes some way towards explaining why he showed a particular sensitivity to the situation that evening.

Medium-Well with a Side of Disgust

On a different occasion, that same guest from the “photograph incident” elicited yet another emphatic reaction from one of Le Bernardin’s servers. This blunder occurred about a year before the Deep Water No. 1 fiasco. You remember because the restaurant had not yet gotten into the habit of ensconcing you in that favorite rear banquette.

Still on the precipice of achieving that coveted “regular” status, your party—the very same trio as before—was given one of the tables nearest to the entrance and the lounge. Abutting the wall closest to 51st St., your seating ensured a perfect view of all the patrons flowing in and out of the space. Their eyes might naturally wander towards you as they make their way towards their own table. But Ortner’s painting, the floral arrangements, and the wooden fixtures—no doubt—were much more striking. Luckily so: they would have been repulsed by what they witnessed that night.

Having then only recently embarked on her gastronomic career, your shutterbug friend counted that particular meal at Le Bernardin as one of her first indulgences in fine French cuisine. She had little sense of Ripert’s biography or the restaurant’s culinary identity—just the kind of tabula rasa, quite honestly, you enjoy bringing to the table. For conscious worship of an experience either builds impossible expectations or preempts any legitimate criticism. The finest restaurants—like the finest wines—should strike at the very core of amateur and expert alike. So I valued your companion’s innocence that evening. It was the sort that expected excellence—that knew what three Michelin stars in New York City signified—but was entirely unspoiled as to the manner in which that level of quality would be achieved. (The third member of your trio was every bit the cheerleader you were back then. Ripert, by reputation alone, could do no wrong).

For whatever reason, you opted for the four-course prix fixe that evening. Likely, you had grown bored of the Chef’s Tasting Menu, an assemblage of the restaurant’s classic dishes that—largely resistant to change—ensured first-time guests could sample some of Ripert’s most famous creations. Though it has yet to reappear post-pandemic, the Le Bernardin Tasting Menu—a bit cheaper and one course shorter—offered a more nimble seasonal expression. But, on some occasions, the lure of novel dishes cannot defeat the notion that you are indulging in a “lesser” selection. And, already down one course comparably, it seems more tempting to take total control of your destiny and choose larger portions of fewer items off of the prix fixe. (To wit, it is easier to add additional courses—à la carte—to such a menu than wedge them within the flow of a tasting).

However, while the freedom of the prix fixe format invigorated you as someone who had seen Ripert’s signatures before, it proved something of a snare for the shutterbug. The menu’s first categories—“Almost Raw” and “Barely Touched”—from which guests choose two starters offered little room for error. At worst, one deigns for the salad or some simple vegetable preparation (offered as an olive branch to vegetarians) while ignoring more than a dozen superlative dishes featuring trout, tuna, sea urchin, scallop, langoustine, lobster, or octopus (just to name a few of the treasures featured from the sea).

For the main course, diners are treated to a selection of “lightly cooked” fish—everything from salmon and skate to dover sole and hiramasa—prepared in diverse ways—like sautéed, steamed, poached, or pan-roasted—served with a range of accompanying vegetables (wild mushrooms, artichokes, creamy sweet corn) and delectable sauces (razor clam chowder, black truffle barigoule, bone marrow-red wine bordelaise). You have decried a “paint by numbers” approach to crafting dishes before, but Ripert’s work here is positively canonical. He raises each fish to a superlative expression of flavor through a deceptively simple array of supporting players. There is no question as to the star of each dish, yet the other elements on the plate demonstrate a surprising intensity of flavor for all their delicacy. Purity, that’s the word, and it resonates most deeply within this section.

However, Le Bernardin aims to please everyone. “Lightly Cooked” typically features a play on the “surf and turf” that has combined seafood like grilled escolar or pan-roasted monkfish with meat such as seared wagyu or braised oxtail. Purity, of course, remains Ripert’s focus—these are no heaping slabs of flesh—but a bit of beef surely pleases guests who look to satisfy their carnal cravings no matter the menu.

The “Upon Request” category—also within the main course section—represents a further show of good faith towards meat-eaters. It has long featured the fewest items of any portion of the menu (ranging from two to four choices). The whole red snapper (baked in an herbes de Provence salt crust) has long been a fixture, principally due to the 24-hour notice required to prepare the dish. More recently, a tagliatelle with spring vegetables and black truffle sauce has offered an à la carte main course for vegetarians (though the restaurant would surely prepare any dish from its Vegetarian Tasting if asked).

But “Upon Request” really exists to house animal flesh. It has offered crispy duck breast (with sour cherry sauce) and roasted rack of lamb (with black garlic jus). But the longstanding option—and the only, other than the whole red snapper, on that fateful evening—was filet mignon. Pan roasted, paired with ravioli made from braised short rib (or oxtail), and dressed only with its natural jus, the steak reflects the same kind of purity seen in the “Lightly Cooked” offerings. The cut is prepared within Ripert’s signature style—and you are sure it is executed with aplomb—but it is hardly the chef’s wheelhouse. Why seek beef at Le Bernardin when New York City touts so many steak specialists? Only the absolutely seafood-averse, dragged to the restaurant for reasons personal or business, need apply.

Yet that shutterbug companion of yours, intent on maximizing her enjoyment of that first fine French meal, subscribed to the logic of totemic luxury that you so abhor. She did well enough with the starters, opting for the “Almost Raw” and “Barely Touched” seafood preparations for which Ripert is so well-known. When it came time to discuss the main course, you noted that you’d be indulging in Le Bernardin’s dover sole—a superlative fish raised, for a $25 supplemental fee, to its highest expression. The third member of the party followed your lead. For it’s hard not to imagine that any item offered at additional cost on a prix fixe is particularly delightful. And why not defer to the same choice of the diner who had been to the restaurant before if choosing among the diverse range of seafood offered is a bit too dizzying?

But the shutterbug advanced a rather interesting line of reasoning. Given Le Bernardin was the finest French restaurant she had ever had the good fortune to visit, why not take the opportunity to indulge in that classic king of the table? Why not order that most coveted morsel of cow whose very name is synonymous with tenderness, with luxury as conceived by beef-eating Anglo-Saxon culture? Why not channel all the kitchen’s expertise towards the preparation of what would surely be the finest filet mignon she had ever tasted. Three stars are three stars, and how could a three-star steak not beat some flimsy fillet of fish?

You could follow her logic but implored her to reconsider. If the menu hadn’t already made it clear, Ripert’s particular mastery is seafood. She had even been a pescatarian for several years—a dietary reality that would have, no doubt, cultivated an even greater appreciation for fish prepared at the finest level. The other member of the party chimed in, drawing on his own experiences at NYC’s other French restaurants better suited to serving flesh.

Le Bernardin was cherished for a reason. It attracted legions of travelers on the weight of specialties drawn from the sea. The chef, as a Buddhist, struggled with the reality of serving animals (hence the “Upon Request” moniker). So would the shutterbug really force his hand—possessing no aversion to the many other options listed—rather than wait to her craving at a more suitable venue?

But the shutterbug held strong, being enamored with the decadence a filet of that caliber might offer. Being a good Amphitryon, you did not belabor the point. The steak was on the restaurant’s menu for a reason, and it was not you who’d be offending Ripert’s sensibilities.

Your server arrived to take the order. The shutterbug, first in line, deferred so that she could steal a bit more time to decide upon her starters. The other member of the party went first, then you. The supplemental items chosen tickled the server. He jotted them down with obsequious delight. The shutterbug, at last, made her selection and dropped the hammer. The server did not seem crestfallen upon hearing her request the filet. He only asked that all-important question: “how would you like your steak prepared?”

Caught off guard—then deferring to her rather limited steak-eating experience—the shutterbug blurted out that venial sin, “medium well.” The server’s face contorted in terror as his eyes rolled into the back of his head. Perhaps he would have refused to accept an answer of “well done” altogether. Perhaps “medium well” skirted the very edge of acceptability while still allowing for some soft expression of disdain.

The server having disappeared following his chastening flourish, you gently explained to the shutterbug the insult she had rendered. (Back then, Gordon Ramsay had yet to wage his memetic assault on overcooked steak). She professed that she had resorted to naming the only temperature she could remember hearing throughout past experiences eating beef among family. Looking back, the shutterbug might have agreed to let you correct the error with the server. But why put her through any additional embarrassment? Medium well isn’t that far out of bounds, and even Ramsay admits his kitchen works to please guests who insist on well done.

The filet arrived looking pleasant enough, but the shutterbug could not weather more than a couple bites. She enjoyed the ravioli portion of the plate and offered the rest of the steak to you. It took conscious effort, but you were able to chew it all down on her behalf. The kitchen would need not bear witness to the total waste of a cow’s life, the shutterbug would learn a lifelong lesson on appropriate doneness, and you would never forget that server’s petrified expression.

And, as with the prior incident, the lingering memory did nothing to spoil the many excellent meals at Le Bernardin—beef free—that followed.

Deceived by the Garnish in Tokyo’s Rarefied Tuna Den

There’s an old family story that always tickled you as a budding gastronome. Your granduncle—no doubt, the first of your relatives to travel the world with any breadth—flew to Japan on business. He enjoyed the in-flight meal (it being, perhaps, the very first point of contact with the cuisine of the land where he would soon find himself). Graciously, he tidied up his tray table so that the stewardess could clear his food. Spying an untouched breath mint tucked into one of the compartments, your granduncle popped the morsel into his mouth. The flight attendant arrived just in time to witness him burst into tears and desperately down his plastic cup of water. Of course, the “mint” was actually wasabi, and your granduncle had fallen victim to a deceptive association of the color green with “cleansing” that had likely snared many a traveler before.

Today, western consumers are better inducted into Japanese food culture. Even the all-you-can-eat suburban strip mall sushi eater comes to know “wasabi” (dyed horseradish, that is) must be handled with care. Scorching your nostrils with an immoderate dosage of the green paste is something like a dining trope. Luring those unaware of its pungency into taking a fatal dab is a favorite prank. Tasting “wasabi”—even in its most bastardized, masqueraded form—stands as a rite of passage for first-time sushi eaters and a point of pride for even the most modestly experienced aficionados, who might still mix “wasabi” into their soy sauce but—at least—have come to learn the appropriate amount.

Freshly-grated wasabi, offered as an add-on at premium prices, has increasingly found its way into mid-range establishments in metropolitan areas. While those patronizing high-end omakases must always expect they are being served the “real thing,” the root’s appearance further down the food chain speaks to greater familiarity with the product. To know real wasabi from its horseradish doppelgänger—to know that people pay good money for the former—is also to know that the green paste, whatever form it takes, is not to be smeared carelessly. So, certainly, mistakes such as your granduncle made must have grown more rare. What well-heeled lover of sushi today would make such a simple—and stupid—mistake?

Two generations and many decades after your granduncle’s debacle, you found yourself in Japan on a gastronomic tour. Those halcyon days in New York—eating at Shuko and up the rest of the sushi hierarchy—hung under your belt. Chicago’s omakase scene, only nascent at that time, did not quite reach such a standard. But you indulged in the craft with some consistency and continued to sharpen your appreciation as best as possible with the Windy City’s most influential itamae. The fundamentals of rice formation, of fish preparation, of hyper-seasonality and ceaseless refinement were deeply ingrained. So you embarked on your trip with a level of experience commensurate with sampling—and parsing—the very best expressions of omakase you could access.

Though you will look to avoid the usual “foodie” dick-measuring, your time in Tokyo exposed you to a handful of the city’s sushi luminaries. The only one of note—for the purposes of this story—was Kiyota Hanare in Ginza.

That restaurant—a rarefied spin-off of the original Kiyota, which opened in 1963—symbolizes chef-patron Masashi Kimura’s passing of the torch. The then-third-generation owner of Kiyota ceded charge of the establishment to his apprentice in 2018. Subsequently, Kimura opened Hanare to provide loyal customers from throughout his 17 years of service with an even more luxurious, intimate experience than before. Eventually, reservations were opened to the public—allowing outsiders a chance to taste superlative quality tuna sourced from the Kiyota restaurants’ exclusive supplier since 1963: Ishiji. Such a relationship ensures Kimura’s access to the fish’s hard-to-come-by upper abdomen—the harakami—which yields the most superlative otoro. At Hanare’s elevated price point—relative to the original Kiyota—the chef can indulge his guests even more fully in this and other ultimate expressions of tuna. (You cannot think of a more noble “retirement”).

Kiyota Hanare marked only the second dinner of your trip and the very first omakase you tried in Tokyo. Looking back, such an experience might have been better saved for the end of the itinerary—when you could astutely compare the quality of Kimura’s exceptional tuna to that sampled across all the other restaurants that comprised the gastronomic tour. As with wine, judging the minute differences that distinguish a “100-point” bite of fish from all the rest demands an intimate knowledge of the “90 to 99-point” quality range. Appreciating the shades of grey that characterize absolute excellence can only occur once “good” and “great” examples are firmly known.

However, by the opposite logic, you wished to place one of the trip’s most superlative meals towards the very beginning in order to take full advantage of a sharpened palate. For long sequences of fine dining at lunch and dinner (and maybe even a second dinner) every day inevitably wear you down. The hedonic treadmill breaks altogether—gastronomy grows utterly charmless—and the prospect of fast food seems infinitely more appealing than sitting down for another tasting menu. Whether or not that sorry state would be your fate, Kiyota Hanare would undoubtedly have the chance to shine. And you would have the pleasure of beginning your journey under the care of a master who now sought nothing more than to please his guests like never before.

Navigating Ginza for the first time—in search of that private tuna haven—proved daunting. Kimura’s offshoot was so new that it resisted some of the various methods of identification you had honed in the lead-up to the trip. Of course, it didn’t help that Kiyota Hanare kept its address a secret until immediately prior to your reservation. But punching that number into Street View only revealed a building that—a year prior—was still under construction. Tablelog confirmed that the restaurant existed, and that its reputation was well-founded. But it offered no clues as to what Hanare’s door or outer signage looked like.