With your hundredth visit looming in early 2023, the time seems ripe to step back, reflect, and review the creative output that has flowed ceaselessly from Ada Street’s colossus of seasonal American cuisine. But it is not quite that easy.

Smyth, when you last left it, had weathered the worst of the pandemic and come out the other side. You still remember how resolutely the restaurant labored to stage your third “The Farm Series” tasting menu, outdoors, in early November of 2020. And you remember, despite the perilous circumstances and pervading frustrations of yet another indoor dining shutdown, just how brightly the cuisine shone that night.

When you finally returned to Smyth—after a period of pickup orders and at-home celebrations—to eat in person, you were merely thankful the day had come. It was March of 2021, and the restaurant had devoted the past year to little more than survival at all costs. The hearth, the record player, and the piscine wallpaper remained, but the staff had been depleted and any kind of larger momentum sapped. The core of a stylistic identity, of course, remained. Yet the grand plans you had sensed at the start of 2020, a paradigm shift towards an entirely new set of forms and sequences spun from the same hyper-seasonality, had long faded.

With lingering capacity restrictions and public health concerns to contend with, reopening hardly meant a return to “business as usual.” Rather, for John Shields and what remained of his team, March of 2021 marked a time to dust off the cobwebs and slowly but surely rebuild. Service by service—though the tables were fewer and the menus shorter than before—the kitchen worked to regain its footing and maybe, just maybe start to dream again. However, though sitting in the dining room and going through the motions brought back a feeling of normalcy, there was no question Smyth’s foundation had been irrevocably changed.

The Farm, once the cornerstone of the restaurant’s ingredient sourcing and the protagonist of the meal’s seasonal narrative, gave way to a more varied array of small domestic purveyors. Smyth’s menu, thus, would lose some of its internal logic—no longer being able to defer to the expression of a singular piece of Illinoisan terroir, at a particular moment in time, as the basis of its creative decisions. Instead, shopping from the same amorphous national pantry as the country’s other great chefs, Shields would need to affirm why particular products were worth the fuss. (Though, at the same time, this change in posture held the promise of enabling the chef to paint with a comparably richer palette of flavors and textures all year long).

Further, while the continued leadership of Chris Gerber and Tyler Gore (as general manager and executive sous chef respectively) would forge an essential continuity with Smyth as it was before, this era would be defined by the introduction of new blood and the fruits of their fresh perspectives.

In the kitchen, that has meant the arrival of Luke Feltz as executive chef of both Smyth and The Loyalist. While, seemingly, hiring for such a role would make Shields himself redundant, the resulting division of labor has undoubtedly enhanced the restaurant’s operation while supercharging the development of its cuisine.

Feltz grew up outside of East Lansing, Michigan and has carried a passion for cooking since childhood, working in kitchens throughout high school and college. Nonetheless, it took a White House internship (under President Obama) and a budding career in nuclear security policy—built upon his degrees in Globalization Studies and Political Science—for him to realize just how deep that passion ran. Feltz cut his teeth as a line cook, then sous chef, then head chef of an “American farm-to-table bistro” in Washington D.C. In lieu of culinary school, the restaurant offered him a golden opportunity for “autodidactic trial-and-error learning there, both culinarily and as a leader.”

With this experience under his belt, Feltz joined José Andrés’s minibar as a chef de partie. Six months later, he found his way to Amass—a zero-waste Michelin Green Star recipient headed by a Noma alumnus—for a three-month stage. Feltz then returned to minibar in the role of sous chef: directing dinner service, writing menus, crafting new dishes with the R&D team, and overseeing the restaurant’s “lauded non-alcoholic beverage pairing” during a period that saw the establishment earn—and maintain—two Michelin stars. (You actually recall meeting Feltz there, in passing, as part of a post-meal kitchen tour in 2018. He prepared an incredibly delicate frozen tart shell that was filled with pumpkin and mandarin then spatulated directly into guests’ mouths).

Feltz had been a fan of Shields—whose Town House and Riverstead restaurants, readers may recall, transformed quiet Chilhowie, Virginia into a destination for East Coast gastronomes—before the Chicago chef joined him at minibar for a collaboration dinner with Sonoma’s SingleThread. But the evening offered a chance for the two to meet face to face and work side by side. This laid the groundwork for Feltz to eventually join Smyth in March of 2019—offering him little more than a year of calm before the storm but providing the kind of pre-pandemic experience that has paid dividends with the return to normal operation.

Rather than representing an abdication of his own role, Shields’s hiring of an executive chef has effectively broadened the kitchen’s range of expression. Feltz shares his senior’s molecular gastronomy chops—with minibar, like Alinea, instilling not only an assortment of advanced techniques, but a rigorous process of inquiry through which they are channeled. But, more importantly, his time at Amass signals an essential grounding in the kind of sustainable, hyper-seasonal cookery that has come to characterize Smyth far more than deconstruction for its own sake.

Chilhowie offered Shields a chance to apply his Charlie Trotter and Alinea training, on his own terms, towards a singular slice of American terroir. And Chicago, maybe, offers Feltz the chance to apply his minibar and Amass experiences towards the broader Midwestern terroir. In fact, now that Smyth looks beyond The Farm to encompass the full national bounty, the stage seems set for a new, bold “big picture” perspective to take hold. Feltz, benefitting from the global perspective of his policy background and the distinctiveness of his autodidactic approach to the craft, seems well-suited to writing the restaurant’s next chapter.

Approaching the Smyth space, equipment, and customer base with the fresh perspective a new executive chef entails has helped to ensure a clean break from the past. At the same time, Shields’s steadfast presence preserves the restaurant’s spiritual and philosophical core even as he cedes a certain degree of creative control. Striking this balance allows the concept, unencumbered by whatever came before Feltz’s time, to charge forward toward an unforeseen frontier of flavor and, in effect, be born anew. It allows for the growth (and associated growing pains) of a new team that need not master old recipes but, instead, may engage in the same kind of experimentation that inspired those hallowed dishes in the first place.

All the while, Shields remains there as a guiding hand and stylistic sounding board that ensures, if only by the same purity of intention, some longstanding connection to his past work. The more senior chef, meanwhile, is granted time to pursue his own course of experimentation. He is free to devote himself more fully to the technical, intuitive work of his craft—to get his hands dirty and play the role of provocateur—without needing to worry about the kitchen in a quotidian sense.

Despite the trials of the past few years, it really seems as though Shields enjoys himself more than ever these days, descending from above and bestowing the team with a preparation they have never seen nor heard of before (but that, at this very moment, he is ready to serve for the first time). The senior chef gets to play the part of the consummate host, the patient mentor, and the wily master while affirming—as only a true artist can—that “Smyth,” as an aesthetic expression, exists outside of what comes from his or Karen’s minds. By sharing ownership of the menu in this way, Shields has quietly ushered in his restaurant’s next generation and begun to cement a legacy that transcends individual talent. Just what that has meant for the development of his cuisine will form this article’s central concern.

When it comes to the front of house, Smyth—as a consequence of the exodus that extended pandemic closures entailed—has had to set about training a new cadre of captains and their supporting front and back waiters. Surely, the staffing issues that continue to pervade the industry make recruitment itself is no easy task. But how, even if the fresh faces are ready and willing to get to work, does the restaurant recapture the magic of its bygone era?

Yes, the coming and inevitable going of favorite team members stands as one of hospitality’s most bittersweet realities. The singular connections formed between “server” and “served” represent one of the craft’s most transcendent features—revealing all the fancy food and wine to be little more than window dressing for a broader celebration of humanity. And bidding farewell to any one figure—whose visage, relative to an ever-changing menu, remains a comforting constant—feels like the closing of a chapter in itself. Yet each heartfelt goodbye, however painful, is typically buffered by a reserve of other staff with whom you share warm relations and who stand ready to swoop in and provide some continuity of service. But, with almost none of its former roster to draw on, just what remains of Smyth’s culture?

At a mechanical level—and despite some early turnover following the restaurant’s reopening—the front of house team has restored the kind of coordination, poise, and precision that makes conducting service (from the perspective of the customer) seem easy. Little niceties, like remembering guests’ birthdays, their handedness, their allergies, and their water preferences, have also—once more—served to enrich the experience. Pashminas and purse hooks, likewise, always lay close at hand. There have, indeed, been inevitable missteps (you recall being given a rather grainy pot of pourover coffee on one occasion) but no persistent problems. Thus, while it has taken some time for the team to return to full strength, the current crop, in a technical sense, does the restaurant’s legacy proud.

Nonetheless, Smyth’s culture has always gone far beyond this kind of “excellence”—a rather empty word when wielded by staid, award-chasing establishments that substitute it in place of an actual personality. Instead, the restaurant has always been defined by the fullness of the staff’s presence, the sense that—rather than running through some contrived, “uncanny” course of interaction—they are thoroughly “there,” in the moment, with you. This genuine expression of self, unencumbered by the other demands of the job, brings with it a whole range of hospitality virtues: warmth, charm, humor, insight, and a sincere sense of care. But these flourishes cannot be forced or fabricated—lest you end up with “uncanny” scripting of another, even more cynical type.

The best any restaurant can do to forge this exceptional degree of presence is to prepare the soil, plant the seed, and provide the kind of support that allows each member of the team to grow toward it on their own terms. With the right balance between care and struggle, the honing of skills leads to increasing fulfillment and, eventually, a full actualization of one’s identity within the hospitality setting. Of course, mechanically, the structure of service must support this kind of interaction, and Smyth remains the only restaurant where you routinely see the staff relieve each other of their pressing duties so that they may remain devoted to an ongoing guest conversation.

Since each member of the team must walk a wholly personal path to uncover and refine the authentic expression of self, it seems wrong to tally how many people possess that particular energy at this particular moment and how many don’t. Rather, you will say that more than a few do, indeed, capture that intoxicating ease and depth of engagement that has always characterized Smyth’s hospitality at its best. Likewise, the potential for that kind of actualization across the rest of the team clearly exists—and the rambunctious spirit shared by the staff (as observed in those moments when no one is thought to be looking) is infectious. Even the back of house, conscripted to deliver and describe certain dishes, play their part by demonstrating a touching humility—and often rivaling their front of house counterparts when it comes to landing zingers.

Chris Gerber and David Bedke—The Loyalist’s floor manager (who has been with the restaurant since 2016)—deserve immense credit for preserving this culture during the pandemic and perpetuating it throughout the cultivation of a new team. So, too, do the Shieldses (embodying, as always, the emotional core that guides the concepts) and Feltz (a young leader, shaped by the pre-pandemic era, now entrusted with carrying the torch in the kitchen).

Ultimately, Smyth’s staff works with a common purpose and displays a devotion to each other that transcends business. You recall hearing about an incident during the past year or so (relayed secondhand and then confirmed in person) that really illustrates this point. One of the restaurant’s front waiters had been taking care of a party of VIPs from whom the kitchen sources some of its product. Going about their duties, this individual was exposed to the grotesquely racist comments being made by the diners. They reported their resulting discomfort to the captain, which flowed up the chain of command, and found that the staff stood in total solidarity. The bigoted guests were allowed to finish their meal then informed that they were no longer welcome back. The kitchen, anticipating how their business relationship might be wielded as leverage (or revenge), immediately resolved to source their product from elsewhere.

In this manner, the entire establishment responded in lockstep to affirm its values and safeguard the dignity of its team. You find this particularly heartening because the racist comments were not directed, as far as you recall, toward anyone present (a rather cut-and-dry case of harassment that merits immediately dismissal from the dining room). Rather, the customers’ behavior was considered objectionable in an overarching sense—a reflection of a backwards and demeaning attitude that stands as anathema to the craft of hospitality. Smyth showed no hesitation in proactively protecting its staff and other customers from even the possibility of perceiving such ugly conduct. The restaurant did so at the cost of future repeat business, of any quality the product it was sourcing possessed, and of whatever retributory bad-mouthing that bruising those bigoted egos may entail.

This kind of “sacrifice” (which, in truth, was something more like moral sureness) simply confirms that Smyth views hospitality as something that stems from the hearts and souls of its team members, something that takes as its precondition the total comfort of those working the floor (rather than their ability to look pretty and hit their marks). This enlightened perspective understands that going the extra mile for employees—making them feel seen and heard—forms the finest guarantee that they will do the same for guests. It’s a philosophy that stands totally opposed to the more conventional cost-benefit analyses used by greedy restaurateurs to justify sweeping venial sins under the rug. It represents—in this era of increasing labor valuation—the future of the industry (especially at the high ”luxury” level). But, perhaps, the best thing you can say is that dining at Smyth today—despite all that has gone on in the world—feels just like old times.

One particular bright spot, when it comes to the front of house, has come by way of wine director Kevin Goldsmith. The Virginia native (a fated connection if there ever was one) came to Smyth by way of Alinea—where he served as head sommelier—in October of 2020. Whereas Feltz was able to immerse himself in what pre-pandemic Smyth represented, Goldsmith had to take the reins, mid-pandemic, of a program that had run fallow. But that Alinea heritage, common to so many members of the restaurant’s team, has served him well. And it surely helps that the wine director was already a fan of Shields’s work—celebrating his anniversary there annually.

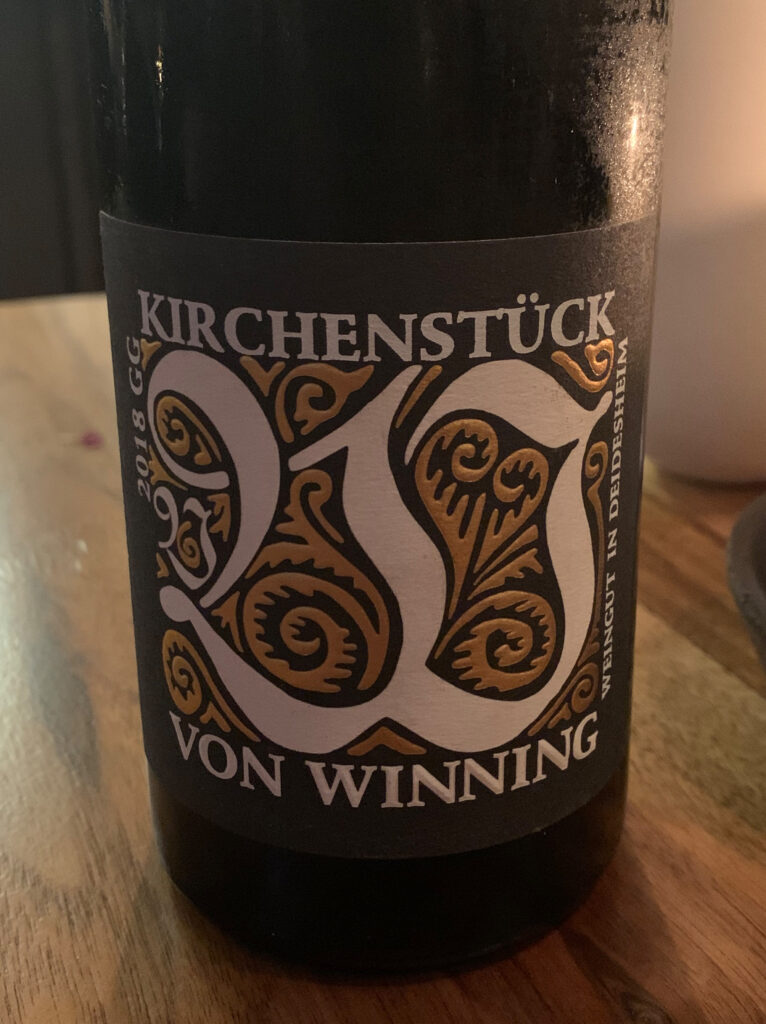

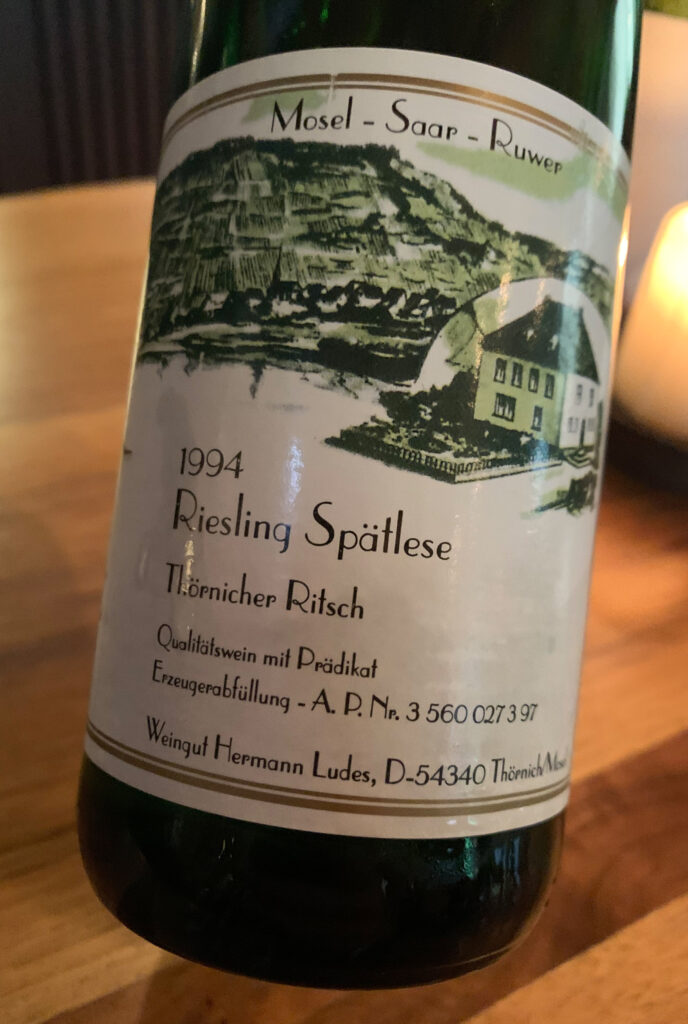

Goldsmith has built upon the estimable work of Richie Ribando, whom you credit with championing renowned producers like Keller and Guiberteau before (at least in this market) they were fashionable. But the nature of the wine market—especially now that global auction demand and the commodification of cult bottles have surged—means that yesterday’s value plays may cost double or triple today. And Goldsmith, not to mention, must contend with offering a three-tiered set of pairings whose highest level (the “Super Mega Pairing” priced at $375) is the only in Chicago that comes close to Alinea’s “Alinea Pairing” (priced at $395).

(Oriole, readers may recall, opts for a two-tiered system of pairings that tops out with the “Reserve” at $275. Temporis, meanwhile, comes closest to matching Smyth and Alinea with a “Grand Reserve” pairing priced at $325).

You typically critique these ultra-premium offerings for the psychological damage they can inflict on consumers. Aspirational diners, who have scrimped and saved to merely get their foot in the door, are left compromising on a “Standard” (in Alinea’s terminology) pairing that implies their luxurious experience is not quite as refined as it could be. (“The Alinea Pairing,” in contrast, would seem to communicate that it is the only commensurate option to properly honor the food.)

Smyth has always deserved praise for terming its “Standard” pairing as “Traditional” and its “Alinea Pairing” equivalent as “Super Mega”—a turn of phrase that reassures customers this is a particularly exceptional option and nothing like what you “must” select to do things right in the eyes of the restaurant. Likewise, while you feel that Alinea’s ultra-premium offering has typically leaned too heavily on Napa and Bordeaux (big, bold wines matched to comparable morsels of A5 wagyu), Goldsmith’s selections have comprised a more diverse and distinctive assortment of wines.

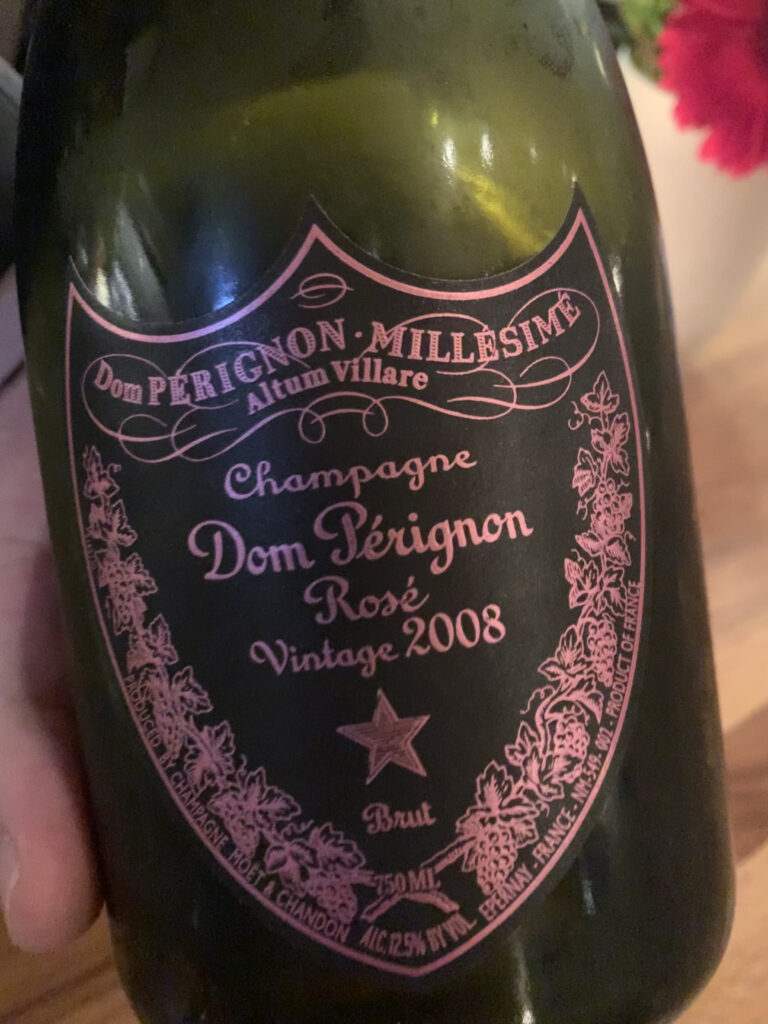

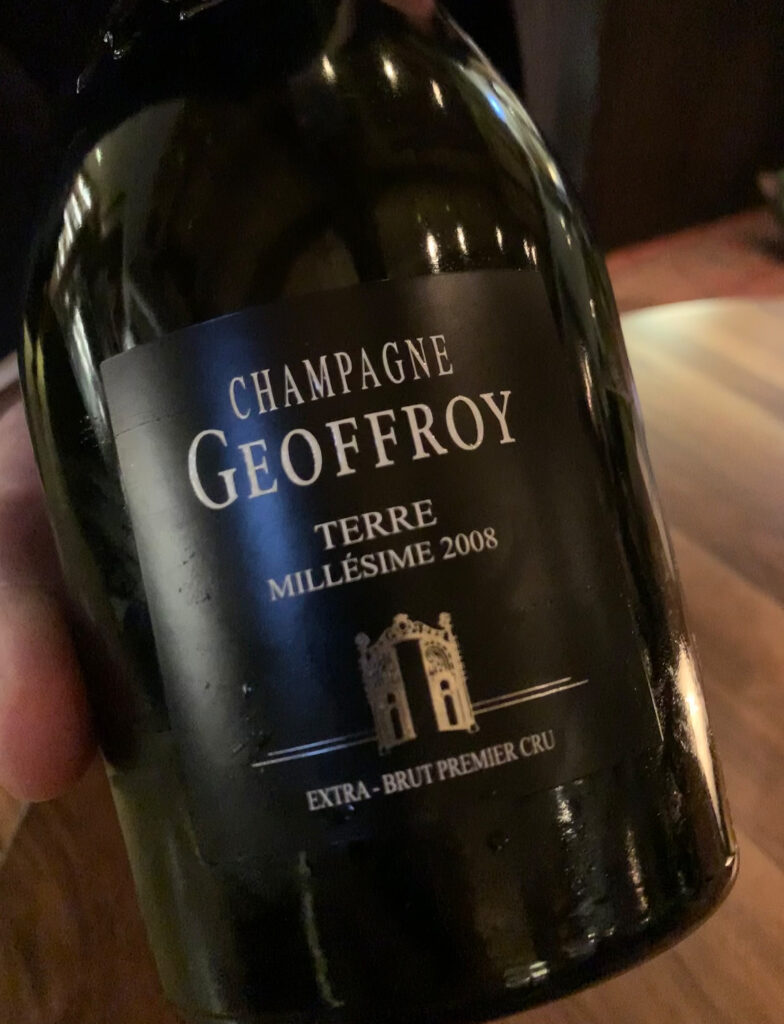

His ”Super Mega” lineups represent the rare high-priced pairings that actually offer equivalent value when compared to buying two or three bottles off the list. Some of the notable wines that have featured on these selections throughout 2021 and 2022 include:

Sparkling

- NV Bérêche et Fils “Reflet d’Antan” Champagne

- 2016 Bérêche et Fils “Cramant” Champagne

- 2014 Marie-Noëlle Ledru “Cuvée du Goulté” Champagne

- 2007 Dom Ruinart Champagne

- 2005 Bollinger Champagne “La Grande Année” Rosé Champagne

- 2004 Laurent-Perrier “Cuvée Alexandra” Rosé Champagne

- 2000 Dom Pérignon P2 Champagne

White

- NV Schloss Gobelsburg “Cuvée 10 Years”

- 2021 Peter Lauer “Kern Fass 9” Riesling

- 2019 Bernard Moreau Chassagne-Montrachet Chardonnay

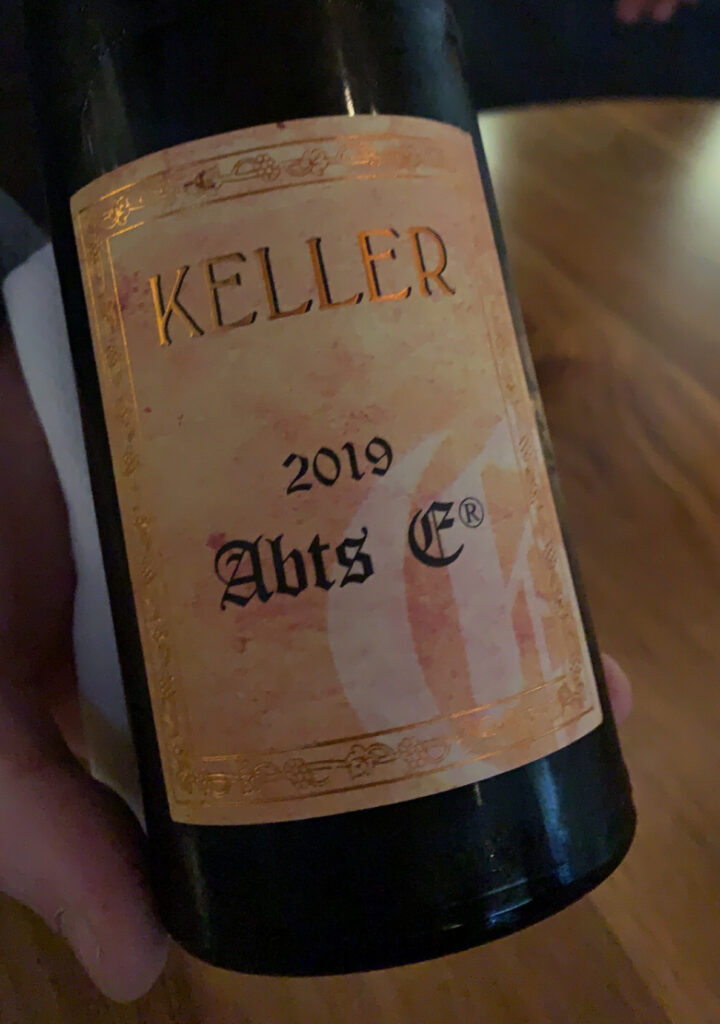

- 2019 Keller “Abts E®” Riesling

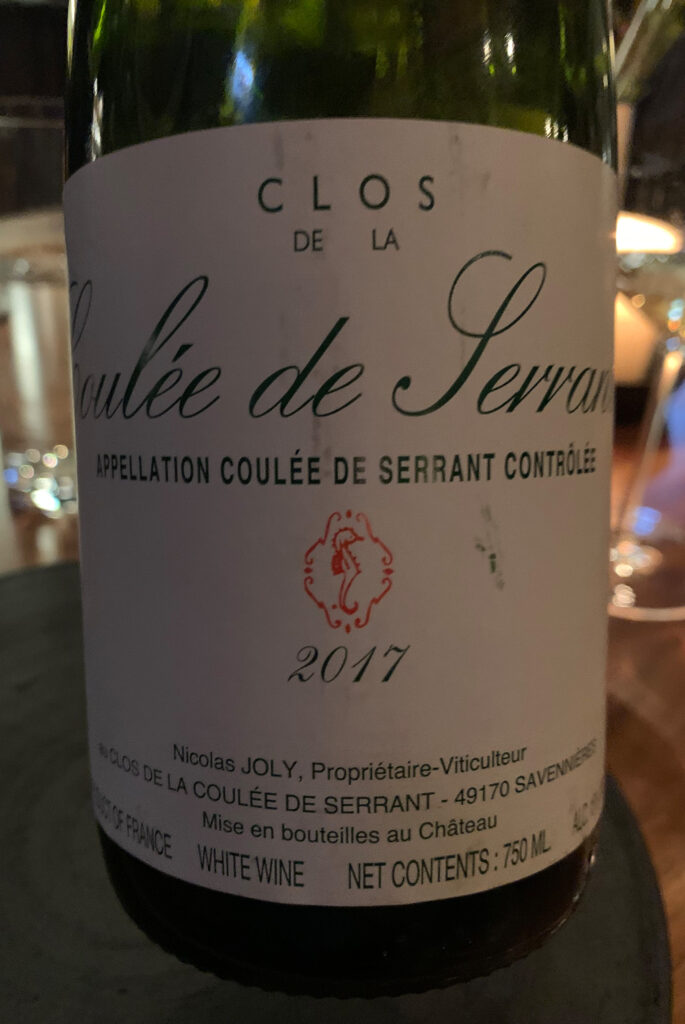

- 2019 Raul Pérez “Sketch” Albariño

- 2019 Willi Schaefer “Graacher Domprobst” Riesling Spätlese #5

- 2019 Wittmann “Aulerde” Riesling

- 2018 Bernard Moreau Chassagne-Montrachet Chardonnay

- 2018 Domaine Laroche “Les Blanchots” Chardonnay

- 2018 Domaine Laroche “Les Clos” Chardonnay

- 2018 Domaine Vocoret “Les Clos” Chardonnay

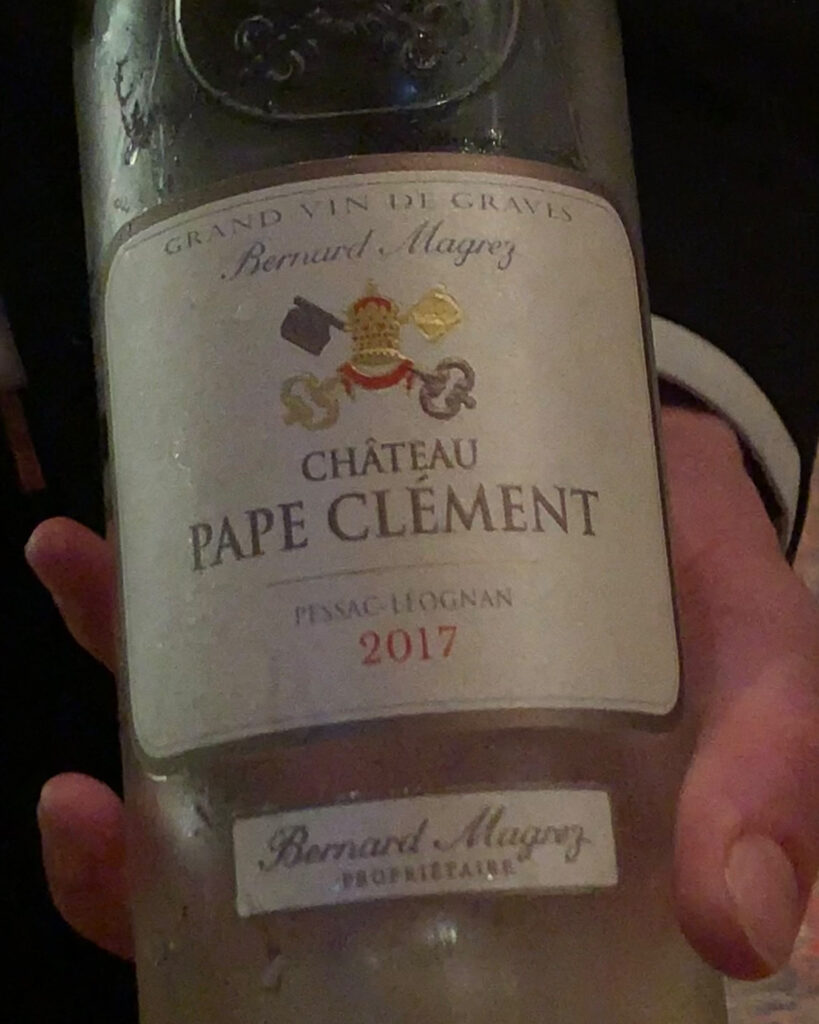

- 2017 Château Pape Clément Blanc

- 2017 Jean-Claude Ramonet “En Remilly” Chardonnay

- 2015 Emidio Pepe Trebbiano d’Abruzzo

- 2015 Jacques-Frédéric Mugnier “Clos de la Maréchale” Chardonnay

- 2014 Aubert “Ritchie Vineyard” Chardonnay

- 2012 Trimbach “Clos Ste. Hune” Riesling

- 2010 Schäfer-Fröhlich “Felseneck” Riesling Spätlese

- 2005 F.X. Pichler “Unendlich” Riesling

- 1997 Trimbach “Cuvée Frédéric Emile” Riesling

Red

- 2018 Pascal Cotat “Chavignol” Rosé

- 2016 Domaine des Lambrays “Clos des Lambrays”

- 2016 Tua Rita “Per Sempre” Syrah

- 2012 Sérafin Père et Fils “Les Cazetiers”

- 2010 Vega Sicilia “Unico”

- 2006 Radikon Merlot

- 1996 Château Ducru-Beaucaillou

- 1990 Château Cos d’Estournel

- 2013 Klein Constantia “Vin de Constance”

- 2007 Giuseppe Quintarelli “A Roberto” Recioto della Valpolicella

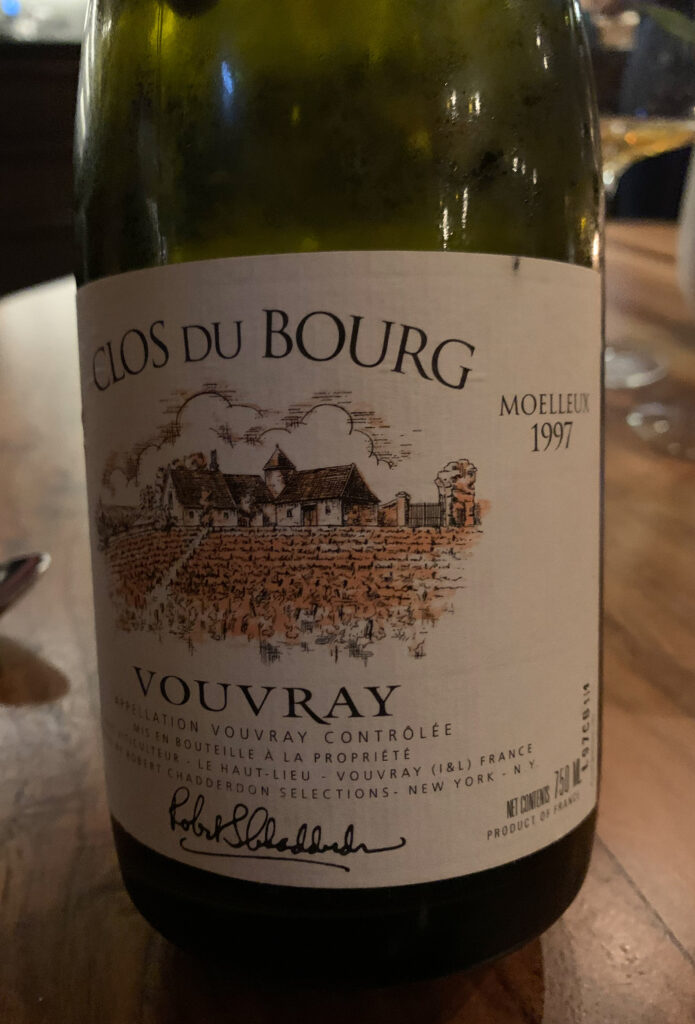

- 1997 Domaine Huet “Clos du Bourg” Vouvray Moelleux

While, admittedly, the red wines listed are not much to write home about, sourcing any substantial amount of aged Burgundy or Barolo for the pairing would—given current pricing—likely detract from its overall value proposition. Not to mention, a meal at Smyth typically only offers one “proper” red wine course anyway (with rosé of the sparkling or still variety often being used in a transitional role where some sommeliers might serve a lighter red).

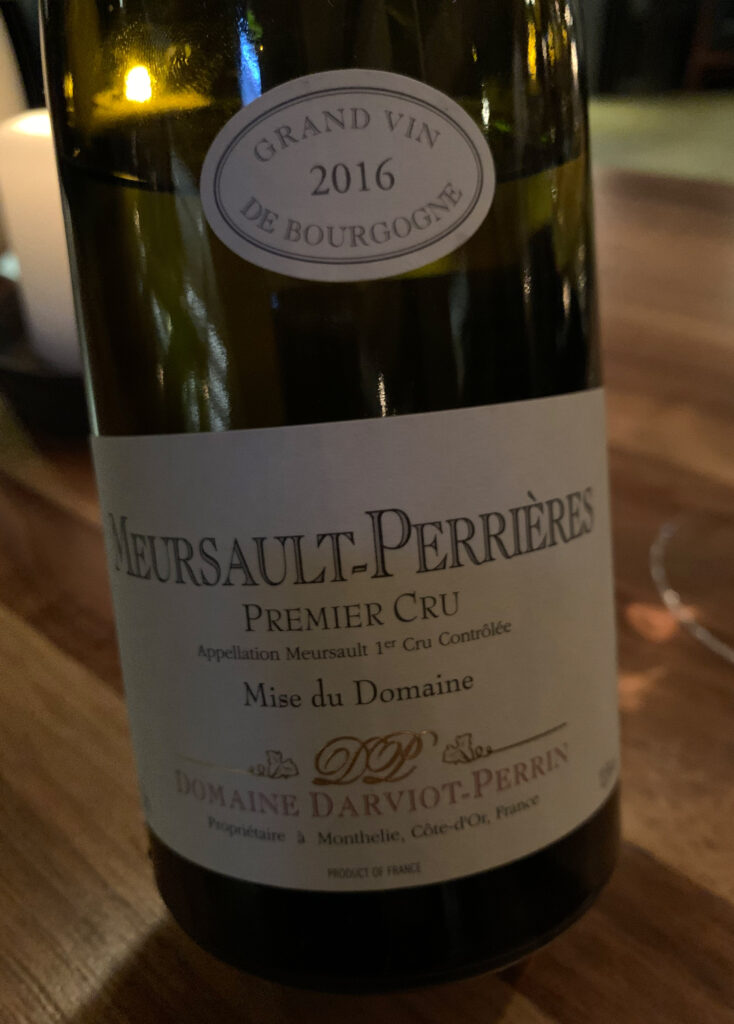

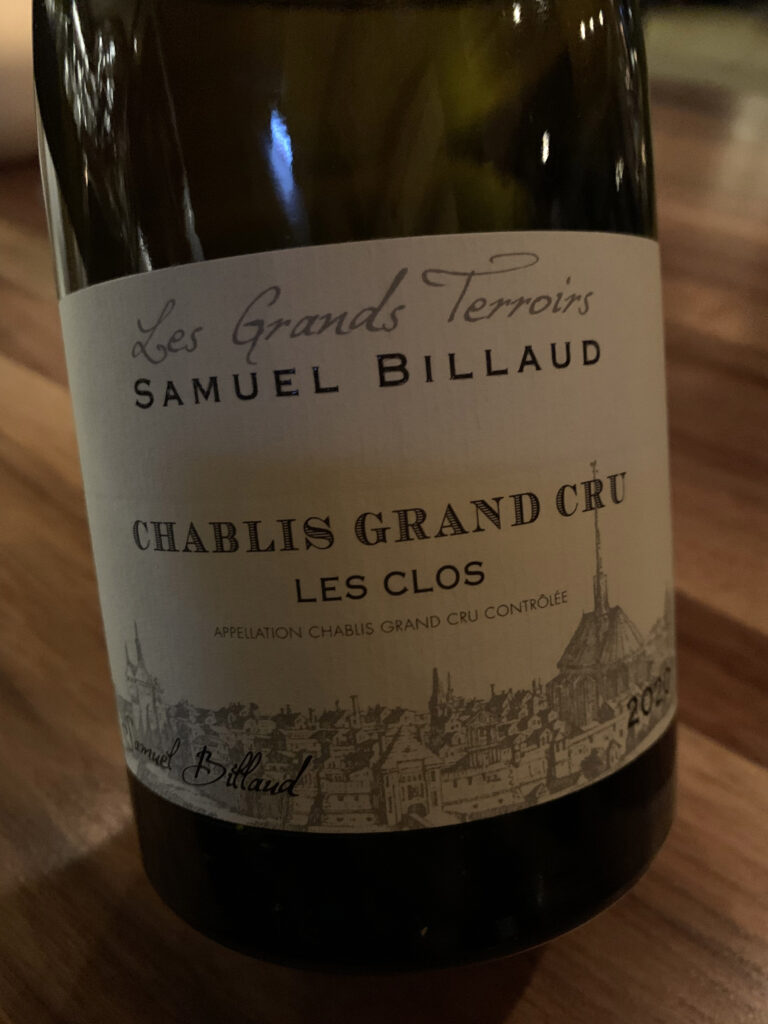

Yes, in truth, Shields and Feltz have come to craft menus that center on pristine expressions of seafood and produce that may be enriched by trace amounts of animal fat (or a more composed sauce making use of the same kind of ingredient). Thus, Smyth’s food really shows well with a wide variety of Champagne and white wine. And producers like Bérêche, Ledru, Moreau, Keller, Willi Schaefer, Wittmann, Ramonet, Aubert, Trimbach, Schäfer-Fröhlich, and F.X. Pichler are close to as good as it gets (at least within this market) when it comes to those categories. Goldsmith also deserves credit for many of the back-vintage bottles this roll call comprises, for a well-aged Clos Ste. Hune, Felseneck, or Unendlich makes quite an impression when it comes to the table.

Of course, Smyth’s new wine director must also—and, as far as any program goes, principally—be judged on the quality of his bottle list. Given that many of the finest selections are destined to leave the menu as quickly as they appear (guilty as charged), you think it best to transcribe the most striking offerings that appeared throughout the 2021-2022 timeframe. These include:

Sparkling

- NV Pierre Péters “L’Étonnant Monsieur Victor MK.14” ($475)

- NV Ulysse Collin “Les Maillons” ($275)

- NV Ulysse Collin “Les Pierrières” ($325)

- 2018 Bérêche et Fils “Campania Remensis” ($255)

- 2016 Etienne Calsac “Clos de Maladries” ($275)

- 2013 Jacquesson “Terres Rouges” ($420)

White

- 2020 Eva Fricke “Mélange” Trocken ($135)

- 2020 Stein “Alfer Hölle 1900” Spätlese Feinherb ($175)

- 2020 Stein “Palmberg” Kabinett Trocken ($110)

- 2019 Bernard Moreau Chassagne-Montrachet “La Maltroie” ($305)

- 2019 Bernard Moreau Chassagne-Montrachet “Les Chenevottes” ($305)

- 2019 Bernard Moreau Saint-Aubin “En Remilly” ($245)

- 2019 Miani “Buri” ($345)

- 2019 Pierre-Yves-Colin-Morey Saint-Aubin “Hommage à Marguerite” ($235)

- 2019 Raveneau Chablis “Forêt” ($540)

- 2018 Fontaine-Gagnard Bâtard-Montrachet ($515)

- 2018 Vacheron Sancerre “Les Romains” ($185)

- 2018 Vincent Dancer Meursault “Les Perrières” ($450)

- 2017 Guigal Hermitage “Ex-Voto” ($450)

- 2017 Jean-Claude Ramonet Chassagne-Montrachet “La Boudriotte” ($275)

- 2017 Jean-Claude Ramonet Chassagne-Montrachet “Les Chaumées” ($275)

- 2017 Domaine Roulot Bourgogne ($195)

- 2016 Anne et Jean-François Ganevat “Les Cedres” ($175)

- 2016 Jean-François Ganevat “Cuvée Orégane” ($350)

- 2016 Terlano “Quarz” ($145)

- 2013 Pierre-Yves-Colin-Morey Chassagne-Montrachet “Les Ancegnières” ($375)

- 2009 Vincent Dauvissat Chablis “Les Preuses” ($950)

Red

- 2017 Cappellano “Otin Fiorin” ($285)

- 2017 Domaine Rougeot Pommard “Clos des Roses” ($125)

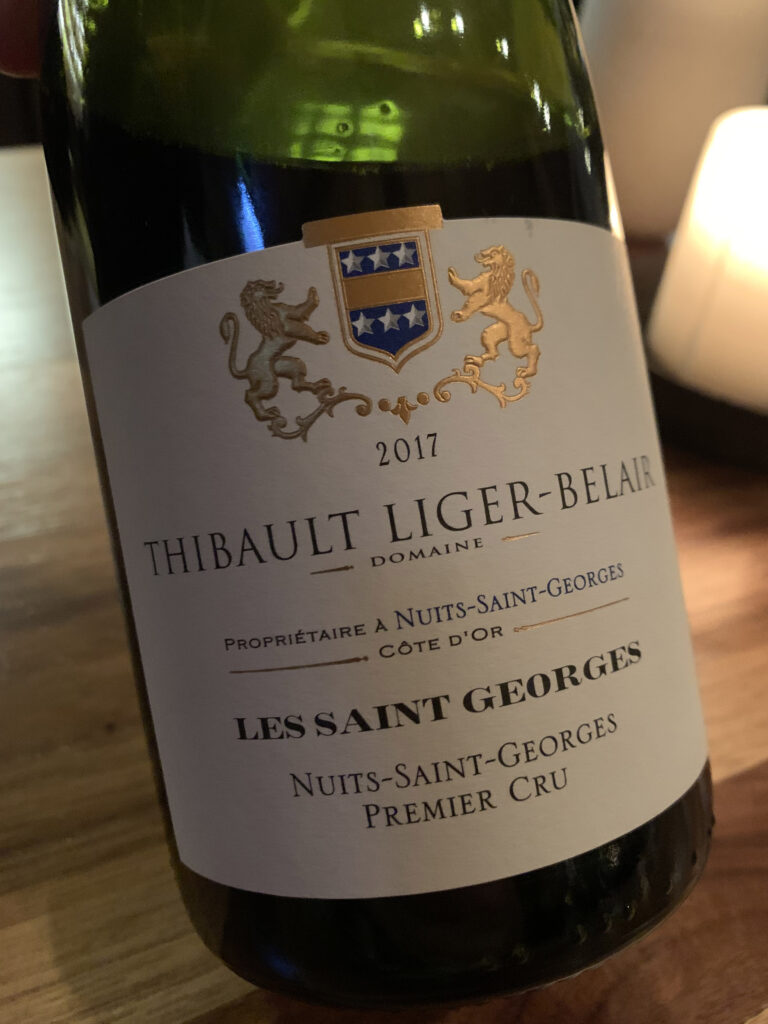

- 2017 Thibault Liger-Belair “Les Saint Georges” ($360)

- 2016 Joseph Roty Bourgogne ($145)

- 2014 Emmanuel Reynaud “La Pialade” Côtes-du-Rhône ($125)

- 2013 Claude Dugat Gevrey-Chambertin ($245)

- 2013 Giuseppe Quintarelli “Alzero” ($750)

- 2013 Pierre Damoy Chapelle-Chambertin ($575)

- 2012 Littorai “May’s Canyon” ($285)

- 2012 Philipe Charlopin-Pairzot Vosne Romanée ($195)

- 2011 Giuseppe Quintarelli “Alzero” ($750)

- 2007 Château Rayas ($1,100)

- 2007 Produttori del Barbaresco “Asili” ($295)

- 2007 Produttori del Barbaresco “Rabaja” ($295)

This, it goes without saying, is a partial list—and it is rather partial to your particular tastes. But, rest assured, there are plenty of notable wines from Alsace, Austria, Bordeaux, the Loire, Napa, the Rhône, Sonoma, Spain, and Tuscany represented as part of Goldsmith’s selection.

Once again, you find categories like Champagne, German Riesling, and white Burgundy to be strongly represented—with producers like Bérêche, Bernard Moreau, Etienne Calsac, Eva Fricke, Pierre-Yves-Colin-Morey, and Uli Stein offering some relative value. Meanwhile, though bottles from Ramonet, Raveneau, Vincent Dancer, and Ulysse Colin are certainly pricey, they represent a relative bargain compared to what the market currently bears.

For example:

- The 2017 Ramonet Chassagne-Montrachet “La Boudriotte” ($275) has a current Wine-Searcher average of $340 at retail.

- The 2017 Ramonet Chassagne-Montrachet “Les Chaumées” ($275) has a current Wine-Searcher average of $250 at retail.

- The 2019 Raveneau Chablis “Forêt” ($540) has a current Wine-Searcher average of $579 at retail.

- The 2018 Vincent Dancer Meursault “Les Perrières” ($450) has a current Wine-Searcher average of $900 at retail.

- The Ulysse Collin “Les Maillons” ($275) has a current Wine-Searcher average of $472 at retail—and, just for comparison, costs $425 on Oriole’s current wine list.

- The Ulysse Collin “Les Pierrières” ($325) has a current Wine-Searcher average of $502 at retail.

By maintaining standard mark-ups across his entire list, Goldsmith offers oenophiles the opportunity to enjoy highly allocated bottles at appealing prices. Using the restaurant’s buying power to reward—rather than rip off—wine lovers represents the absolute peak, philosophically, that any program can attain. It ensures that you are always excited to browse the selection and see what new, exciting, and limited drinking experiences are at hand. (However, in the spirit of goodwill, you strictly ration how many of these coveted bottles you order so that others may also appreciate the wine director’s good work).

Moving on, you think the Jura wines from Jean-François Ganevat—when they have been offered—represent some of the list’s finest values, showing the kind of slight oxidative notes that make for a heavenly match with Smyth’s food. Nonetheless, you think this category could benefit from being expanded upon.

When it comes to reds, there are a few good values—like the Cappellano, Charlopin-Pairzot Vosne Romanée, Dugat Gevrey-Chambertin, Joseph Roty Bourgogne, Rougeot “Clos des Roses,” and Reynaud “La Pialade”—worth appreciating. These bottles are not quite best in class when it comes to QPR, but they allow you to enjoy red Burgundy (or lauded producers from Barolo and Rhône) at a more friendly price.

Turning toward the more expensive options, you have omitted bottles like the 2018 Emmanuel Rouget “Cros Parantoux” ($1950) because, while a relative steal compared to a $3,531 Wine-Searcher average, these young grand cru and premier cru wines from Dujac, Lignier, Roumier, and so on offer limited enjoyment while also being found on other lists throughout the city. Instead, you most appreciate that Goldsmith has been able to secure wines of premium quality with some degree of age (and, thus, drinkability).

As with the pairings, you think the red wines represent a bit of a relative weak spot compared to just how good the white wine selection is. But, as you mentioned before, this fits well enough with a menu that does not typically offer more than one course of meat. Red wine devotees, surely, will still find something to like. And you think it is sensible to weigh the list towards flexible, harmonious options rather than cynically stacking it with Cult labels that, while they might sell, detract from the program’s identity.

Nonetheless, you can certainly offer some other constructive criticism. The lowest priced bottle you could find on Smyth’s list came in at $115, which seems a little steep. Oriole, by contrast, offers a plethora of wines under $100 with many around $50 and some as low as $30. In Smyth’s case, you suppose it is fair to consider that a basic menu price of $285 per person, along with an entry-level $155 “Traditional Pairing,” can be used to justify what amounts to a relatively meager “minimum spend.”

But, certainly, nobody is forced to order alcohol, and you think it is fair to say that even the cheapest of Goldsmith’s chosen bottles (a $115 Burklin-Wolf Riesling, Selbach-Oster Spätlese, Tondonia Blanco, or 2017 Santa Cruz Pinot Noir) offer a memorable drinking experience. You might say that Smyth looks to funnel customers toward a meaningful encounter with (a slightly more expensive class of) wine while Oriole maintains a friendlier posture (which corresponds to its prominent cocktail program). It is a stylistic decision that makes the former’s program feel more serious even though the tone of service is humorous and engaging. Perhaps the list is filled with wines that all have stories to tell?

Though this is to take nothing away from Oriole’s incredible selection and high standard of service either. Sandoval’s restaurant simply offers more room for guests to imbibe at a humbler level of expenditure. That should be celebrated, for it yields an atmosphere of more varied manners of enjoyment corresponding to different kinds of consumers. Smyth, instead, grounds itself a bit more firmly in a classic European fine dining tradition that privileges wine as a matter of course. The restaurant is anything but stuffy—and patrons face no problem ordering drinks from The Loyalist to be brought upstairs—but it constructs a certain sense of shared wine appreciation across the dining room that can be highly enriching. Still, it is hard for you to know—with by-the-glass and half bottle options—if anyone actually feels sticker shock.

Otherwise, when it comes to the content of the list, you would like to see the selection grow to encompass more still rosés (that can match the early courses while offering some weight on the palate), large-format bottles (perfect for larger parties, especially when sparkling), and wines from the Jura. When it comes to the latter point, you can appreciate that Smyth has not delved as deeply into “natural” producers as Elske, for example, has. The incidence of off flavors and aromas in certain bottles of these wines presents a gamble in a two-Michelin-star setting whose food itself is quite bold. Some drinkers simply do not like the character of such wines to begin with.

But, as you said in relation to the Ganevat offerings, the oxidative notes present in Jura’s white wines seem like a dream pairing with Shields’s cuisine. And the red wines made from Pinot Noir, Poulsard, and Trousseau in that same region offer a light body and earthy character that could make for good affordable, early drinking options within the category. The presence of the Radikon, first chosen for Smyth’s collaboration with Atsushi Tanaka (a devotee of “natural” wines himself), would seem to suggest that the door is open.

Despite these small critiques (for what beverage program in Chicago can be said to be perfect?), you believe that Goldsmith is unquestionably one of the city’s finest wine directors. Certainly, you think that Richard Hanauer (who does the buying for LEYE’s RPM properties) might take the crown when it comes to the sheer scope and scale of fine bottles sold at his restaurants. But Goldsmith joins a short list of professionals—including Aaron McManus (formerly of Oriole) and Christian Shaum (of Bazaar Meat)—who aggressively pursue back-vintage offerings (at auction and via traders like Ventoux) for their lists while keeping their fingers on the pulse of the wine world’s next big producers. These expertly curated selections join with low markups to make for wine programs that actually reward knowledgeable drinkers (rather than reserving the best bottles only for those willing to spend exorbitantly).

But Goldsmith, McManus, and Shaum do not merely direct from behind the scenes. They are sommeliers who work the floor at single establishments (or, perhaps, upstairs/downstairs hybrid concepts like Smyth/The Loyalist or Bazaar Meat/Bar Mar) and weave their enthusiasm for the offered bottles into every interaction. This sense of ownership, which trickles down through every member of the supporting wine service team (Smyth, in fact, can now boast two Advanced Sommeliers on its floor), mirrors that shown on the culinary side by the chef. It makes for a beverage program that really equals (and enriches) the food on account of the degree of self-expression it transmits.

Each bottle at Smyth, Oriole, or Bazaar Meat, no matter the price, feels special because the passion that it stoked in the purchaser is always close at hand (or, at the very least, can be translated by a trusted deputy). No matter your level of vinous knowledge, placing an order inevitably engages you with the sommelier, inducts you into their craft, and earns you all the warmth, charm, and insight that comes with a trek through the cellar. These interactions, though intimidating for the neophyte, may even prove more memorable than a bit of face time with the celebrity chef. A good sommelier could be the one to help a newcomer finally, legibly define their taste and find some foothold from which they may grow their knowledge. Or, for the oenophile, a wine director working the floor may possess some tidbit of arcane trivia that transcends mainstream reference material and deepens your enjoyment of a favored producer.

Goldsmith, beyond the content of his selection, brings this bespoke, dynamic dimension of beverage service to the table and promotes it throughout his team. He establishes a mood of earnest—never sneering—wine appreciation that further glorifies the tasting menu. In truth, it really honors the entire evening because it sparks conversation and connection with a specialized segment of the front of house that, through their work, reveals yet another facet of Smyth’s beauty. That would be: a wine list written and conveyed as the work of enthusiasts, not salesmen, with plenty of pleasure, insight, and exposition to go around no matter what sum you decide to spend.

This is a feeling—of tapping into an eternal, bacchanalian celebration that connects all wine lovers past, present, and future—that you only ever sense at a couple other (aforementioned) places in town. Without the work of professionals like Goldsmith, McManus, and Shaum, Chicago’s wine scene—at least when it comes to the kind of bottles that turn collectors’ heads (and, thus, drive conversation) globally—would risk fading into obscurity. But, more importantly, these figures are helping to cultivate a new generation of drinkers with a combination of intelligence, reverence, and relatability. Perpetuating this culture of good faith enjoyment (while razing any lingering traces of snobbery’s status insecurity) is one of the trade’s most consequential tasks—should wine retain its hard-fought place on the American table.

Finally, before you tackle this article’s principal task (evaluating the growth of Smyth’s cuisine throughout the 2021-2022 period), it is worth noting just a couple more changes that might better contextualize your analysis.

Prior to the pandemic, Smyth’s “Omaha” (or extended) menu was priced at $235 per person with a more customary “Smyth” menu offered for $155 and an abbreviated “Classic” menu for just $95. When you returned to the restaurant in March of 2021, this three-tiered set of experiences had been streamlined and substituted for a solitary “Smyth” option at $225 per person. By September of 2021, the restaurant had increased the price of that sole menu to $240 per person. And, in 2022, the price of the “Smyth” menu has gone up to $285.

That figure—$285—happens to match the price of the tasting menus served at Ever, Moody Tongue, and Oriole while falling short of Alinea’s “Salon” ($295-$365), “Gallery” ($405-$465), and “Kitchen Table” ($475) tickets as well as Kyōten’s omakase ($440-$490). It is also worth noting that none of these sums are inclusive of tax, whereas only Kyōten’s is inclusive of service. So, a two-Michelin-star dinner in Chicago essentially starts at $377 per person exclusive of any beverages. And each of the four restaurants bestowed with that honor—along with Bibendum himself—must be pleased to hold a united front when it comes to defining what visiting an establishment “worth a detour” must necessarily cost.

Certainly, prices have risen across a wide range of industries with particular pain felt in the grocery store and at the pump. Thus, it is certainly not worth clutching your pearls when the city’s upper stratum of fine dining increases the cost of entry in lockstep. (Ever, for what it’s worth, debuted at $285 while Oriole “2.0” savvily bumped its price up from $195 with the reveal of its renovation. Moody Tongue was $155 per person, inclusive of pairings, in 2019 before raising it to $225 in May of 2021 after earning its stars and reopening. The shift to $285, exclusive of the beer pairing, has come about more recently as the brewpub now offers only one seating time on Wednesdays and Thursdays alongside two on Fridays and Saturdays).

You think there exists a demographic of consumers that will always privilege getting a “one-,” “two-,” or “three-Michelin-star experience” for the lowest price possible. These are the same people that critiqued dearly departed Blackbird’s $25 prix fixe lunch as not being of “Michelin-star quality” before eagerly writing the restaurant—and Ryan Pfeiffer’s superb, nighttime extended tasting menus—off altogether.

This class of consumers, in its slavish devotion to Bibendum’s assurance of quality, comes to believe that the concepts of “value” and “luxury” can easily coexist. The $25 prix fixe lunch, which may very well be superlative relative to the fast casual place around the corner, is saddled with all the expectations “Michelin-star dining” entails. This myopic focus on the supposed status of a meal—on the hyperreal symbols and photo opportunities that might work to satisfy the diner’s desired mental picture—distracts from the substance of what is served.

These consumers backwardly view Michelin stars as the sine qua non of gastronomy, a promise that some (totally subjective) idealized version of luxury dining is theirs so long as they buy the ticket and take the ride. But they do not know how much they do not yet know. They do not understand that these awards distinguish, retroactively, establishments that have successfully actualized some particular vision of their own. And that developing one’s taste means engaging each restaurant in good faith, sensing the unique story it tries to tell, and appreciating it (or not) without any deference to what some outside organization thinks.

Michelin stars form little more than a signpost of quality—of potential quality should one be attuned to the vision of a particular chef and the spirit of his or her team. But, interpreted blindly, Bibendum’s recommendation drowns out the restaurant’s own voice and serves as a vessel for the projection of one’s singular dining predilections onto some unsuspecting concept. Unknowingly, these consumers come to view each restaurant at the one-, two-, and three-star level as competing amongst themselves to best satisfy their personal palate. Value—or, “how can I get as much of what I like for the most competitive price”—thus forms an effective heuristic to rule out a plurality of options.

However, while this conceit can be understood at face value, it denies the reality that cuisine, as art, must naturally challenge the diner and look to expand their perception of deliciousness beyond the hedonistic towards the more intellectually appealing. A naïve, wholly egotistical perception of a given restaurant filters its gustatory expression through a unique range of genetic and cultural predispositions (to say nothing of explicit and implicit biases or nostalgias). And this approach to fine dining, characteristic of those who view the Guide’s sanction—rather than the chef’s distinct artistry—as the main draw, naturally leads to the privileging of lowest common denominator menu design and unrelated “smoke and mirrors.”

$285 per person might rightfully represent the threshold where Chicago’s two-Michelin-star restaurants can maintain the proper guest-to-staff ratio (one of Bibendum’s own heuristics in assessing quality) in the post-pandemic era. It might form the minimum price with which these establishments can lard their menus with the totemic caviar, crab, lobster, uni, oysters, tuna, foie gras, truffles, and wagyu that close-minded diners come to associate with “luxury.”

But presenting the population with four choices—Ever, Moody Tongue, Oriole, and Smyth—at the same rating and price point emphasizes an equivalence that does not really exist. For implicitly pitting these restaurants against each other serves to obscure stylistic nuances that are better appreciated in isolation, and you think this proves particularly punishing when it comes to the public perception of Smyth.

For one-and-done aspirational diners, a $285 meal at Ever gets you “diet Alinea” molecular gastronomy in a dark, sleek setting. A $285 meal at Moody Tongue gets you a subsidized celebration of beer paired with generous portions of decadent, globe-trotting fare. A $285 meal at Oriole gets you flavors of striking intensity (with a Japanese sensibility) in a grungy luxury setting. And a $285 meal at Smyth amounts to something intricate and hyperseasonal but, otherwise, hard to define.

The perception of Shields and Feltz’s cuisine suffers because its high degree of dynamism and experimentation cannot be sensed by the first-timer. Plus, even if these qualities were discerned, the novel flavors and textures they amount to hold greater appeal for palates that have become desensitized to the trite totemic luxury ingredients served elsewhere. Forgoing these crutches means abandoning the easy source of satisfaction they provide—and offering, for those who expect certain tropes to be satisfied at the “two-star” level, lower perceived value.

In truth, Ever, while presenting itself as experimental at a visual and environmental level, barely changes its menu when compared to Smyth. The same is true for Oriole—though Sandoval offers a warmer kind of experience, a gastronomic “guarantee,” that excuses certain perpetual offerings. (Moody Tongue’s menu, though you lack as many reference points, shows an admirable degree of change—in line with shifting beer pairings—but also pales in comparison to Smyth).

When your average consumer compares the four Chicago tasting menus that occupy the $285 price point, Oriole often wins. The restaurant offers finely tuned, powerfully flavored preparations (several of them that can already be considered “classics”) without all the molecular gastronomy bells and whistles but within an eminently welcoming setting. Ever and Moody Tongue may also reliably please diners upon their first encounter on account of their novelty value. Duffy’s elaborate constructions and Wentworth’s beer-focused fare seem one of a kind. But, with repeat exposure, the value propositions at Oriole, Ever, and Moody Tongue tend to degrade, and the flaws that hide behind all the flash and decadence start to assert themselves.

Smyth, by comparison, is capable of hitting higher highs and lower lows on any given night. This kind of inconsistency seems vexing—until you realize that each dish, rather than representing one of the kitchen’s finest creations over a period of a few months, expresses something fleetingly rooted in the state of nature during that particular week. Shields and Feltz’s food does not only evolve (as the preparations at Ever and Oriole are also apt to do), it never stops evolving because its foundational ingredients are always in flux. The chefs remain faithful to a process that remains far riskier than its peers but that richly rewards repeat visits. They operate in a way that ensures each week, each night’s menu conveys a totally unique story (and not just the “best of” efforts from the past half a year).

This sense of a singular, bespoke experience is hard to value until you pierce the veil of luxury and realize how static and rehearsed many fine dining restaurants are. So, to the uninitiated, Smyth is doomed to be branded an underperformer in that $285 category. Its dishes do not comprise tried-and-trued favorites (à la Oriole) or inventive constructions (à la Ever and Moody Tongue). Rather, they are quietly complex and a bit eccentric. They offer ingredients you have never heard of nor thought edible. They prize distinction over decadence but, time after time, achieve a striking hedonism unlike anything you have ever tasted elsewhere.

Few diners, presented with three other renowned restaurants to try at the same price, will make it to Smyth for that pivotal second visit. Instead, Oriole is likely to deliver the kind of pleasure that demands a repeat visit six or twelve months later. Ever and Moody Tongue will be remembered as unique, easily digestible experiences (“that place with the frozen hamachi,” “that place with all the beer”) that, nonetheless, needed not be endured again. But Smyth, in retrospect, will likely seem a bit weird: a cuisine that is difficult to label, with ingredients that are hard to comprehend, and flavors that provoke as much as they please. The restaurant will be judged a “bad value” until the aspirational diner tires of their A5 Miyazaki. Most hobbyists will never reach that point. So, would greater price differentiation help?

By breaking with the pack, Smyth might avoid the apples-to-apples comparison that reliably privileges Oriole when it comes to nascent or occasional fine dining customers. It may also shield Shields’s restaurant from having to compete with the comparably gimmicky (or, at least, more legible and marketable) experiences offered at Ever and Moody Tongue. If Smyth raises its price, it may cultivate some sense that it offers a more “serious” tasting menu whose exoticism and added dynamism is worth the ticket price. Just the same, that may lead to greater expectations (and disappointments) regarding the presence of certain totemic luxury ingredients.

Likewise, undercutting the other two-Michelin-star establishments at that $285 price point would allow Smyth to occupy the “value” position relative to its peers. While, surely, this may help deflate expectations regarding those aforementioned ingredients, Shields and Feltz make generous use of caviar and game as part of their menu’s identity. Their kitchen also maintains a pretty healthy staffing level that—along with the front of house—would be hard to ever cut. Not to mention, a lower menu price may also serve to attract those aspirational consumers who want an idealized “luxury experience” for as little as possible (and who are even more poorly equipped to appreciate a cuisine that transcends so many of fine dining’s sacred cows).

Neither raising nor lowering the price—now that the genie is out of the bottle—would seem to make sense. Any competitive disadvantage Smyth, without The Farm as its narrative focal point, faces in highlighting the dynamism of its food should, perhaps, be remedied at the level of service. It should certainly be clarified at a critical level (which you always intend to do). But, when it comes to pricing, Smyth finds itself in a particularly sticky position due to how it presents its “service charge.”

Many of Chicago’s finer restaurants, in the wake of the pandemic, have replaced the uncertainty of discretionary gratuity with a guaranteed 20% applied to the totality of the check (though Alinea, for the record, has done so since 2015). For diners who order expensive wines—those whose price dwarfs that of the meal itself—this additional sum, sprinkled on top of the original mark-up, can seem foreboding. (Some imbibers, per this discussion, consider the difference in labor applied to a $100 versus a $1,000 bottle to be negligible and deflate their tip from 20% to 15% in such cases. However, you generally agree with those who say anybody buying such expensive wine can afford to reward the staff commensurately—should the service, of course, be up to par).

More broadly, these 20% “service charges” serve to codify—regardless of how one feels about tipping culture writ large—a degree of gratuity that has undoubtedly become a best practice (if not a basic point of etiquette to boot). In a time of belt tightening, this stipulated sum ensures that a restaurant’s staff is guaranteed a certain return, regardless of the customers’ generosity (or lack thereof), for their efforts. This may, relative to a typical gratuity that is split only among the front of house, extend to the back of house and reward their (often unseen) work. Perhaps it is used to subsidize the cost of health insurance for the entire team (something that Giant has done, via a 2% surcharge, since 2018 and that Galit currently does with a 5% fee).

But, in fine dining settings where service is reliably of a high caliber, consumers should have little to complain about. 20% gets you out the door without any time devoted to tip calculation or deciding whether 22%, 25%, or 30% might endear you more to the establishment. Yes, it may be more fair—in the interest of full disclosure—to bake the “service charge” into the actual menu price (à la Kyōten). Yet the restaurants instituting this practice know that guests have been conditioned to pay some minimum gratuity for competent service. And, with rival establishments clustered around common price points (like $285), who wants to be the first to up the ante to $342 and risk seeming like the “more expensive” option?

Personally, you have had little trouble navigating these “service charges” in practice, as the no-tipping model had already started to take shape—for better or worse—before the pandemic. However, it has been hard to ignore some of the misgivings that have struck other customers.

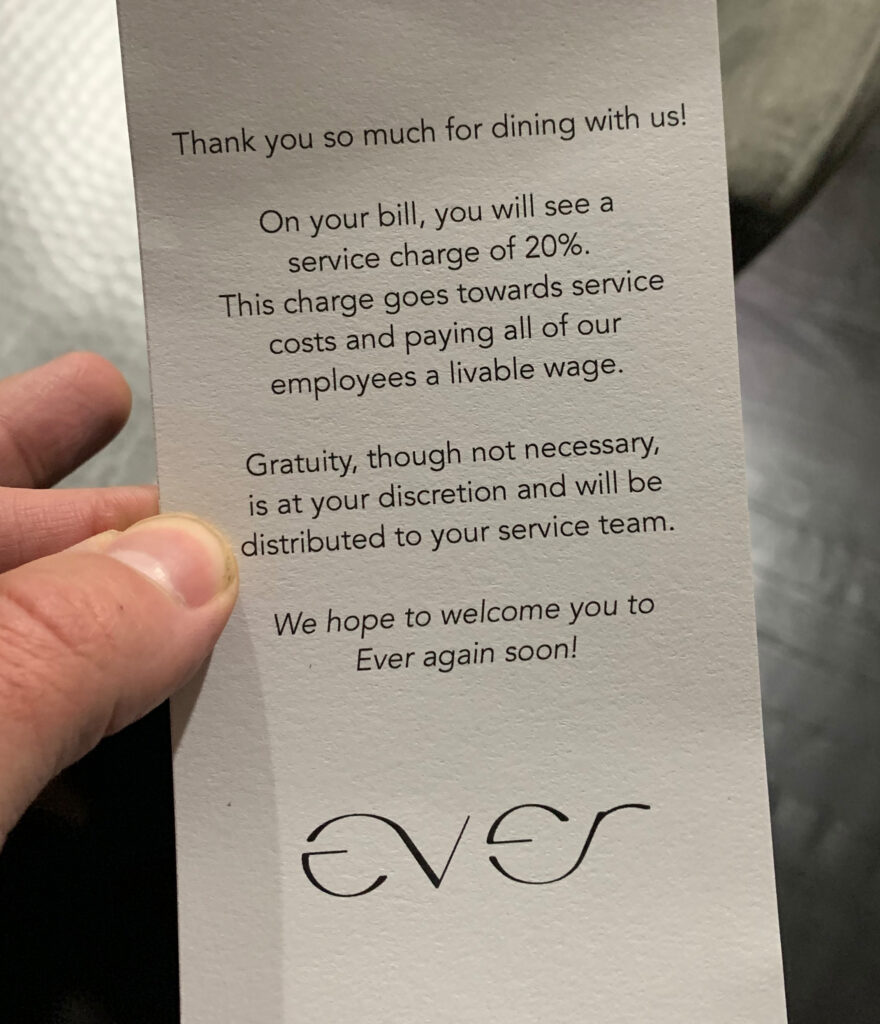

Ever includes a 20% “service charge” that is “is applied towards providing fair and equitable wages to our front and back of house employees as well as operating costs (service-ware, fixed costs, food costs, wages, etc.) to ensure the highest level of excellence in our quality of service.” However, the restaurant also presents a line on the receipt through which customers can provide a tip. An insert that comes along with the bill states that “Gratuity, though not necessary, is at your discretion and will be distributed to your service team.”

This phrasing—which leaves it up to customer “discretion” whether or not they will follow the custom of offering a gratuity—feels a lot like double dipping to some guests. They do not understand why things like “fair and equitable wages” and “operating costs” are not already included in the ticket price. Nor do they like the fact that they are being guilted into tipping 20% (“paid to non-salaried, front of house employees who are directly in service of customers”) on top of a total that has already been inflated more than 30% due to the “service charge” and tax.

By comparison, Moody Tongue clearly states: “PLEASE NOTE: the 20% Service Fee represents gratuity for the service team.” So, clearly, customers need not leave any additional sum. Alinea, though this policy has since changed, did not even print a tip line on its receipt for the longest time (as Kyōten still does) to avoid any possible confusion and assure guests that adding further gratuity is not even possible (let alone subtly encouraged). Roister, while representing a more casual format, even stamps each receipt with “20% Service Charge Included” over its tip line.

Oriole, you recall, began applying its own 20% “service charge” following its “2.0” renovation. You certainly, in a moment of drunken revelry, missed that fact early on and provided a full gratuity (on top of what was already charged) on at least on occasion. At some point, Oriole ceased appending the “service charge”—either in general or on your receipts (to save you from yourself)—in lieu of traditional, wholly discretionary amounts. (Kumiko, as a corollary, assesses a “20% Service Charge” to be “distributed equitably amongst the Kumiko staff.” However, their receipts also clarify that “We have kept a tip line on our checks for anyone who would like to leave something extra. Any additional gratuity goes straight to the service team. Arigatou!”).

Smyth finds itself in a position not unlike Ever. That is to say, the restaurant assesses a 20% “service charge” that is listed on the itemized receipt and accompanied by a tip line with no further context. Whereas Ever, in the wake of customer complaints, has fielded the check insert pictured (and quoted) above, Smyth buries its explanation in the Tock FAQ:

“Why am I being charged tax on the service charge? We include a service charge as part of booking your experience. This charge is applied towards operating costs (service-ware, fixed costs, food costs, wages, etc.) to ensure the highest level of excellence in our quality of service as well as to provide fair and equitable wages to our front and back of house employees. Additional gratuity paid on the evening of your reservation is at the discretion of each guest. 100% of any additional gratuity is paid to non-salaried, front of house employees who are directly in service of customers in strict accordance with the Fair Labor Standards Act.”

Smyth’s captains, you think, must also be prepared to respond to questions regarding the purpose of the “service charge” relative to the gratuity being solicited via the tip line. But, considering that the written explanation leaves something to be desired, you do not think these kinds of conversations—which must tiptoe around the conditions that satisfy this “discretion”—are destined to be successful. In fact, you would wager that guests who look to the staff for further guidance invariably end up leaving some additional tip rather than ever feeling like they’ve been let off the hook.

Ultimately, everyone confronted with the check—or with the answer that “additional gratuity is at your discretion”—is simply left to wonder whether they will be viewed as a cheapskate for leaving the tip line blank. Moody Tongue, Alinea, Kyōten, Roister, Oriole, and Kumiko each, in their various ways, totally assuage this fear. They either remove any ability to offer an additional tip, remove the “service charge” (like Oriole eventually did), or make it entirely clear that there is no expectation guests leave an extra sum. They do not leave customers—pleasantly inebriated after a fine meal—reaching for their calculators in order to subtract tax, then “service charge,” and refigure some appropriate gratuity that feels like a cheery form of extortion at the end of the day.

You could argue that “discretion” is an entirely fair term, which allows guests to bump the 20% “service charge” up by an additional 5%-10% (in line with a 25%-30% total gratuity that you think falls more in line with what one should tip for a superlative dinner). This is your own personal best practice. However, you could also argue that your “discretion” may view providing “fair and equitable wages to our front and back of house employees” as precluding any need to offer one single red cent more. For is tipping culture, philosophically, not based around the subsidization of those wages?

But fine dining stands as one of American culture’s most insecurity-laden commercial/social settings, and diners (especially those of the aspirational sort) as often left grasping for what they think to be “proper” etiquette—what they think affirms that they “belong.” Just as tiered menus and wine pairings may make guests feel like they are compromising on some greater expression of luxury, a tip line—even when 20% has already been assessed—feels like a challenge in which one must, despite some misgivings, demonstrate they are a generous, upstanding customer like everyone else. (Who, even if they fault the establishment for maintaining such a policy, can stomach stiffing—or being perceived as stiffing—the server who just catered a four-figure for them?)

Smyth’s “service charge” has, like Ever, attracted negative attention on the restaurant’s Yelp page. However, it has also spurred its own dedicated thread on the “Chicago Food” subreddit (in which the policy was roundly criticized). And, you must admit that you have even overheard another customer loudly complain about Smyth’s “service charge” while seated in an adjacent booth at CLAUDIA (an establishment that, for the record, adds 22% to the bill and solicits no further tip).

Thus, it must be said that Smyth’s handling of its “service charge” represents a strange miscue for a restaurant that you consider a standard-bearer of enlightened, superlative hospitality. When you take the peak-end rule into account, this end of meal shakedown may even work to negate what had, until then, been an exemplary evening. Nonetheless, it should not be hard to find a solution.

First, the restaurant must ask itself if it really lusts for a 40% surcharge to be applied to the totality of the check. If that is the case, the pricing of all food and beverage should have a 20% increase baked in. Then, Smyth could either assess a 20% “service charge” on top of that or leave a traditional tip line (which allows for the possibility of some greater gratuity) but not both.

Second, if the restaurant views a 20% surcharge as the minimum amount it takes to make the staff whole—and views any additional gratuity as a total bonus—it needs to state this more explicitly on the receipt (à la Moody Tongue or Kumiko) rather than borrowing Ever’s weasel wording of “discretion.” Just as easily, Smyth may consider increasing the “service charge” to 22% or even 25% if that forms the comfortable minimum from which they would not be inclined to solicit any further tip.

Lastly, if the restaurant is interested in ensuring some percentage of sales can be put toward “operating costs” and “equitable wages” while leaving the door open to more typical, discretionary tipping, it should change the surcharge to something in the 5%-15% range. While you still think it would be better to bake this amount into the menu pricing, a lower surcharge may encourage customers to more willfully tip an additional 10%-15%, perhaps rounding up, without feeling unfairly squeezed.

Any of these strategies would help anticipate (and quell) a policy that has damaged Smyth’s otherwise sterling reputation. For there remains plenty of goodwill toward restaurants in the wake of the pandemic, and consumers are certainly on board with the idea of assuring their servers are well taken care of. However, anything perceived as a surprise or predatory charge immediately scuttles this sense of bonhomie. It conjures up the old stereotype of some pushy, mustachioed peddler of luxury that flatters you—painting a picture of effortless, unlimited possibilities—while stealthily picking your pocket.

Going back to the question of a $285 price point, it would seem Smyth is stuck between a rock and a hard place if it looks to differentiate itself relative to its two-Michelin-star peers. The way the “service charge” is managed means that the restaurant’s menu price has no real room to be lowered. And any increase, while serving to position Smyth as a more “luxurious” experience relative to Ever, Moody Tongue, and Oriole, may fall flat considering the cuisine’s intellectual (rather than hedonistic) appeal is likely to polarize aspirational diners who choose the establishment based solely on perceived (read: price-based) superiority.

Reflecting on these points, you now realize how important Smyth’s pre-pandemic, entry-level “Classic” menu (available for just $95 in 2019) was in allowing customers to test the waters of the restaurant’s experimental cuisine and naturally build up to more elongated, expensive, and exotic expressions. That, really, formed the concept’s competitive edge at the two-Michelin-star level: the unabashed value play for those who just wanted a taste of what Bibendum deems “worth a detour.”

Instead, after about a year of post-pandemic operation, Smyth debuted a $345 per person “Chef’s Table” experience that, beyond offering front-row seats by the kitchen and increased interaction with its team, comprises a longer (“enhanced”) menu filled with even more experimentation. (By comparison, Oriole’s $325 “Kitchen Table” offers premium seating without any additional courses. Alinea’s $475 “Kitchen Table” offers privacy and a couple unique preparations but distinguishes itself more with the “immersive” quality of the room—as expressed through the manipulation of light and sound).

While the absence of the former “Classic” menu makes it hard for Smyth to snare aspirational diners who might not—relative to the restaurant’s flashier peers—understand the its appeal, the “Chef’s Table” affirms that Shields and Feltz aspire to offer the city’s greatest gastronomic experience. The “Omaha” menu, in its time, was also somewhat limited: only a certain number of tables in the dining room could be devoted to what was frequently a four-hour meal. Correspondingly, the kitchen need only focus on crafting a smaller number of those unique dishes that distinguished the “Omaha” tasting from the “Smyth.”

But the “Chef’s Table,” billed as a “one-table-a-night experience” (though actually offered for up to two or three parties as necessary), takes things further. It is, in effect, singular, and it allows the kitchen to channel a large degree of effort toward a small number of special plates. This takes all the precision that is characteristic of sweeping, Michelin-starred dining rooms and applies it in a more intimate encounter. The fact that “the chefs serve and explain each course,” as described on Tock, sounds more like an omakase—or the four-seatings-a-week Chef’s Counter at Rose Mary you just reviewed. The menu carries that intoxicating air of being a friend of the house, of being treated to delights that are for your tongue only.

Alinea’s “Kitchen Table,” surely, offers a bit of that feeling. Yet only for parties of six, which you think is more fitting for special celebrations than any kind of routine date night. It also does not help to be ensconced behind glass as the restaurant’s other guests are paraded through the kitchen. Sure, this privileged position might serve to feed some diners’ egos—and stoke status insecurity in those who, looking in from the outside, have chosen one of the humbler menus—but the effect is a bit too much like a fishbowl. And, quite frankly, everything Alinea does feels so overwrought, so calculated to please tourists and their cameras, that there is absolutely no sense of romance to their top-tier culinary expression.

Smyth’s “Chef’s Table” represents a doubling down on the experimentation that can be so polarizing for one-and-done diners. However, when you come to appreciate the process that Shields, Feltz, and their team engage in, this can only be called the restaurant’s ultimate experience. In talking through the preparations with various members of the back of house, you really get a sense of the warmth and camaraderie that reigns. Many of the ingredients and techniques that get described go over your head. Questions are always welcome, but even those who prefer to sit back and soak in the experience will be struck. For so much of what is served has just come into season, has just been freshly picked, or has been carefully sourced from some small farm (and not a ubiquitous national purveyor).

Through the “Chef’s Table” you come to learn—if you did not already—just how dynamically the kitchen operates. Every dish seems to tell the same story: the chef got their hands on some certain ingredient this week and inspiration took hold. Sometimes, that ingredient forms the central component of a preparation. On other occasions, it plays a supporting part in a more persistent recipe that Smyth has been tweaking week to week or month to month. But you always get the sense that the various pieces are constantly changing—that what you are tasting, tonight, will never exactly be replicated.

There is certainly something cavalier about this paradigm. Does the party that only enjoys a tasting menu once or twice a meal really want to pay that premium only to roll the dice on something no other customer has eaten before? Static menus, especially for nationally renowned restaurants like Kasama, help ensure that every guest, on any given night, gets to taste the best of the chef’s creations. But Smyth’s interpretative, generative process—while risky—delivers more deliciousness in the aggregate. The “Chef’s Table” allows diners to embark, alongside the kitchen, on a creative journey. In doing so, it reveals just how short-sighted it is to clutch onto “perfection” when forces like the novelty effect and hedonic treadmill ensure anything perceived as such is destined to be short-lived.

Yet it is only through repeat experiences that this reality comes to the fore, and you hope that showcasing Smyth’s work from 2021-2022 illuminates just how well this process pays off. You may even say that, while most fine dining restaurants offer diminishing returns with further exposure, Shields and Feltz’s food grows exponentially in its expression thanks to the perpetual entry of new ingredients into new and old forms. Once your palate comes to prize this shapeshifting quality, it is hard to ever return to a more broad, nomadic manner of dining out (at least when it comes to Michelin-starred tasting menus).

One last note about the “Chef’s Table.” When booking tickets for the experience, Tock necessitates that users choose between Smyth’s “Reserve” ($225) and “Super Mega” ($375) pairings in order to proceed to checkout. This kind of stipulation is not unheard of: Alinea required the same kind of commitment when purchasing its “Kitchen Table” but, to its credit, no longer does. You think it is fair for restaurants to guarantee that guests booking their most premium seatings will support the wine program to a moderate degree. But this presupposes that consumers value the beverage’s traditional, privileged place at the table. And you cannot recall any restaurant ever justifying such a policy explicitly.

The good thing is that while Smyth makes it so that you must choose one of those options, it does not collect payment for the pairings at checkout. Rather, your selection indicates an intention that is later confirmed at the start of the meal. This provides an opportunity to opt for bottles from the list instead. You think it is good form to spend an amount that corresponds to the cost of the stipulated pairings. But you do not think the restaurant would hesitate to accommodate someone who wanted to drink less wine or no alcohol at all. (Feltz has previously designed the menu’s non-alcoholic pairings, which have yet to return but would certainly fit the “Chef’s Table” format well).

In order to organize Smyth’s creative output from 2021-2022, you will use a loose narrative structure that allows you to preserve the meal’s (each meal’s) momentum. However, the wide array of dishes this period comprises will be grouped thematically, allowing for a richer evaluation of how certain ingredients have been treated over time. Also, the persistence of particular set pieces (filled with ever-changing items that roughly maintain the same form) will allow for certain sections that track the evolution of a certain idea (or obsession) over a longer period of time. You will also look to reference Goldsmith’s chosen pairings when notable.

2021-2022 has seen Smyth host collaboration dinners with Christopher Kostow, Johnny Spero / Rubén García, Paul Liebrandt, Ron McKinlay, and Atsushi Tanaka, which have formed some of your peak gastronomic experiences in Chicago. It is striking not only to taste another chef’s cuisine, but to see the degree to which Smyth changes its own menu—even compared to what was served only a week before. You are able to sense how these collaborations work to fuel the kitchen’s usual creative process and kick it into overdrive. Thus, while you will omit the guest chefs’ dishes from your analysis, you will feature noteworthy Smyth creations from these one-off dinners that help inform the restaurant’s larger body of work.

With all that said, let us begin our exploration of the noted period, an era you might term the rebirth—or reorientation—of Smyth’s cuisine. For, though the restaurant’s core philosophy has remained the same, its practitioners comprise many new faces. And their devotion to the expression of terroir—once of a distinctly Illinoisan type—has expanded to include all the riches of the national bounty. From this mix of old and new and near and far, Smyth has charted a course that breaks from its past while, in your heart of hearts, still ringing true. That, perhaps, forms the silver lining of the crisis the industry has endured: revealing what quietly remains resilient even when everything else turns upside down, reminding chef and diner alike just how precious every fleeting moment—and morsel—is.

But first, before getting all poetic, let us return to Ada Street.

Good ol’, congested Ada Street, which now swells with added traffic from the western end of Randolph Restaurant Row. There, the new Local 130 Plumbers’ Hall and Parq Fulton Apartments (now home to two glitzy Bonhomme concepts) have formed the capstone to a promenade that once—just a few blocks east—seemed to fizzle out. Yes, the days where Smyth and Elske stood as lone fine dining outposts, with parking lots for neighbors, are but a distant memory. Development, now, has formed a pincer movement that has saturated 177 N Ada in all directions.

One block to the north, Ever has clinched two Michelin stars by offering Curtis Duffy’s sweet, herbaceous interpretation of molecular gastronomy—drawn, at least in part, from the Alinea heritage that he and Shields both share. The latter chef, nonetheless, need no longer worry about Rêve Burger stealing his thunder (as if frozen fries and a ketchup + mayo “secret sauce” could ever take down The Loyalist’s “Dirty Burg”). Rather, Ever’s new lounge After will present a distinctly more up-market rival to Smyth’s basement haven.

One block to the west, you find the two aforementioned Bonhomme haunts: Bambola and Coquette. While you find this group underwhelming in a purely culinary sense, they hold a Michelin star (at Porto) and have developed a rather formidable formula for creating aesthetically appealing concepts that turn the heads of the influencer class. Bambola, with its hackneyed “Silk Road” theme, hardly forms a direct competitor; however, Coquette’s “modern and playful takes on bistro classics” treads into the same exact territory as Shields and Feltz’s reimagined menu for The Loyalist. When it comes to food and wine, you think Bonhomme is clearly outclassed. But you think Coquette, nonetheless, will have little trouble attracting diners to its “pink, Parisian, Champagne drenched dream” of a venue.

The area to the south of Smyth—comprising Washington Boulevard and Madison Street—remains surprisingly commercial, with little by way of fine cuisine until you reach Monteverde. However, continued residential development, alongside significant investment in the streetscape, is sure to cement an ever-greater population of patrons ready to fill the seats of Randolph’s restaurants.

Finally, to the east of Smyth lies the same veritable wonderland of hospitality as before. But, at its furthest reaches, that now includes a luxe steakhouse from Feltz’s old boss José. It includes a rejuvenated Oriole (favored, you think, to win a third Michelin star with the foundation its remodeled interior and more immersive manner of service provides). And there are a couple new chef-driven tasting menu concepts—like Joe Flamm’s counter at Rose Mary and Stephen Gillanders’s within Time Out Market—to contend with too.

Smyth finds itself as something of an old warhorse among upstarts, renovations, rotating theme menus, and all manner of superficially appealing “clubstaraunts.” The exact nature of the restaurant’s value proposition is not so easily distinguished as its two-Michelin-starred peers—or even as the Poseys’ place right around the block. That is not for lack of depth or artistry. Shields and Feltz make beautiful food, but they never embellish it. Their dishes are beautiful just as nature, quite simply, is—and, thus, they trade the viral appeal of alien hues and tortured textures for a subtlety that subverts the social media paradigm.

Thus, most visitors to 177 N Ada are destined to go downstairs in search of easy, immediate pleasure. They traverse the sidewalk while falling under the shadow of The Mason, a 13-story apartment building that stands across the street. Seasonally, The Loyalist’s patio—a remnant of the pandemic era—breathes life into the corridor like an open-air café. It humanizes a stretch of road better characterized by honking horns, screeching tires, and the occasional lobbed profanity.

But, once the weather cools, customers cannot wait to slink inside, climb down into the basement, and tuck into one of Chicago’s most totemic burgers—recently christened as the city’s best for the umpteenth time, drawing an appreciative response from Shields along with an even more striking admission, from the chef, that the notion of a “best burger” is inherently flawed. (Philosophically, you must agree: the “best” burger—or rendition of any beloved comfort food form—is always, apart from those examples that stoke intense personal nostalgia, the one sitting right in front of you at a given moment).

All the while, the idea of “Smyth”—of what the concept upstairs may represent—is left shrouded in mystery. The pickled and charred onion, the smash patty, and the frites announce that someone, somewhere back in that kitchen can really cook. The rest of the “Hors d’Oeuvres,” “Plats Petit[s],” and “Plats Principaux” signal that bar food is hardly de rigueur. Guests would be forgiven for thinking that a stuffy French toque reigns with terror over the dining room above. Yet, save for any accidental ingress (something bound to happen despite the signage), The Loyalist’s patrons get little more than streetside glimpse of Shields’s masterwork.

The dining room, they may note, is filled with wooden tables and chairs interspersed with the occasional structural beam. Fine stemware sparkles atop the surfaces, candles flicker, but there’s not a white tablecloth in sight. Instead, you may spy brick walls, a well-worn rug, and an ample credenza (also in wood). There’s a lounge area, and a central kitchen pass from which a tangle of legs intertwines to meet the outflow of dishes. The guests, in their own right, comprise a sea of red bottom heels and loafers with the occasional isle of boots, sneakers, sandals and/or shorts. But that’s about all your Ada Street vantage point—positioned some half a story beneath the floor of the dining room—affords.

Does the average visitor to The Loyalist, lured by the promise of a superlative beef patty and set of buns, dwell on what goes on upstairs? Seated snugly in the bosom of Smyth’s basement bar, who could want for more? Nothing about the two-Michelin-star operation, viewed from the outside, teases or taunts you. The restaurant’s posture is not one of unseen extravagance shielded by a sleek façade or set within a coy alleyway. No, Smyth more or less lays its cards on the table. It begs to be discovered but has refused to enmesh itself with any kind of ambient trickery.

As West Loop reaches critical mass, Ever and Oriole will remain blissfully above the fray: worlds unto themselves situated beyond the mobs of roving yuppies. Passing by the chamber of hanging food—or stepping through the ancient freight elevator—will form the portal to an experience that stands totally removed from the larger neighborhood. But Smyth, with front-facing windows that are open to the world, will find itself woven more and more deeply into the bustle of the city. As the restaurant becomes less isolated, it is bound to feel more ordinary—just another one of countless dining rooms in the area. Yet forming this connection to the reality of big city life, rather than looking to escape it, forms the fulcrum of Smyth’s hospitality.

The Shieldses, as always, offer a vision of luxury that is wholly integrated into everyday life. That is reflected equally by the burger, beer, and a shot offered downstairs—as well as the two- to three-hour tasting menu conducted upstairs. For the view out from Smyth’s windows, toward the quotidian fitness classes and dog walking that define life across the street at The Mason, reminds you that appreciating the moment of the season—an evening at table with those you hold dear—should feel ordinary. That is not to discount the outlay such an experience demands, but to affirm that it engages feelings rooted in the familiar. Smyth does not offer the sugar high of fantasy, but the deeper sweetness that only an awakening—a reflection on (and reconsideration of) our daily habits—can provide.

When you climb the steps and pass through the weighty wooden door that forms the restaurant’s threshold, a feeling of warmth immediately takes hold. There is no imposing host stand, no cold holding area from which to cross-examine those who seek entry. Instead, the host or hostess whisks themself around the counter to relieve you of your belongings. The wine director and general manager are usually on hand to offer their greetings too. But there is no question that this is a restaurant in motion. Almost the totality of the operation is visible from this entry point, and you are guided to a table that feels less like a sanctum and more like a conduit that shares, alongside the other guests, in the energy that flows out from the kitchen.