Otto Phan has been a busy man, and you cannot think of any other chef that has managed the pandemic’s uncertainty so well. Of course, it helps to be a one-man band who, not that long ago, was serving sushi out of a humble trailer. There’s a nimbleness afforded to an itamae that need not worry about supporting dozens of employees but can focus purely on sustaining their craft. Yet Phan saw the pandemic not as a test of Kyōten’s survival, but, rather, as a golden opportunity to write its next chapter.

What the chef has achieved, even if his cuisine is now priced out of reach for many consumers, represents a paradigm shift every bit the equal of Chicago’s initial “omakase boom” four years ago. If you want to check which way the wind is blowing, just look at the $250 per person “opulent and intimate 10-seat dining cove” LEYE opened inside of its fast casual Sushi-san back in February. But just as Phan, upon first opening, envisioned greater things for the city’s omakase scene than his homegrown competitors, Kyōten “2.0” cements his status as the undisputed king of the genre.

You will spare readers the pain of retreading the same ground as your original review of Kyōten from October of 2020. That lengthy article, which principally tracked the growth of Phan’s cooking since the restaurant’s opening in August of 2018, touched a bit on the pandemic. However, it preceded Chicago’s second indoor dining shutdown, and a bit of retrospection might help set the table for this present piece.

Throughout the pandemic, Kyōten sold $120 bento boxes for pickup during the early evening before closing, when allowed, to conduct a solitary private dining experience. This format allowed Phan to balance a certain degree of volume with the continued pursuit of excellence. At $500-$600 per person (varying with the number of guests in the party), these omakases touted an eye-popping price. However, being inclusive of gratuity, the cost was actually not far off of what Alinea charges for its top-tier experiences.

Far from profiteering on the circumstances, Phan saw in the private format a path towards offering a greater sense of luxury during a period when most businesses had to compromise to stay afloat. For their money, guests got an evening one-on-one with the chef. By being masked, vaxxed, and separated from patrons by the sushi counter, he quelled any lingering health concerns that might, at a busier restaurant, detract from a total sense of comfort. The chef generously accepted last minute cancellations, however inconvenient, without complaint. He even contended that he would totally refund any customer that felt dissatisfied upon completion of the meal (a money back guarantee that, to your knowledge, has never yet been claimed).

Kids, importantly, could come along for the pricey omakase and ate free. Not to mention, Phan promised he would cook until you were full. In this manner, Kyōten offered a turnkey experience unlike anything else in pandemic Chicago. It felt like a real escape from the doom and gloom of reality without demanding the kind of tolerance and understanding paid towards establishments still getting back on their feet.

However, the real enduring effect of Phan’s private dining format has to do with fish sourcing. Apart from the chef’s hallmark inochi-no-ichi rice (one and a half times the size of typical sushi rice), Kyōten has long been characterized by his relationship with a “fish guy” working out of Fukuoka. The benefit of forging a strong relationship with such a purveyor has nothing to do with freshness. Phan concedes that, with the benefit of modern logistics, it is a given that Chicago’s top sushi restaurants (like Momotaro and Juno) are serving the freshest fish. Fattiness, rather, is the real prize, and having a great purveyor means having someone there on the ground to secure the best of the catch.

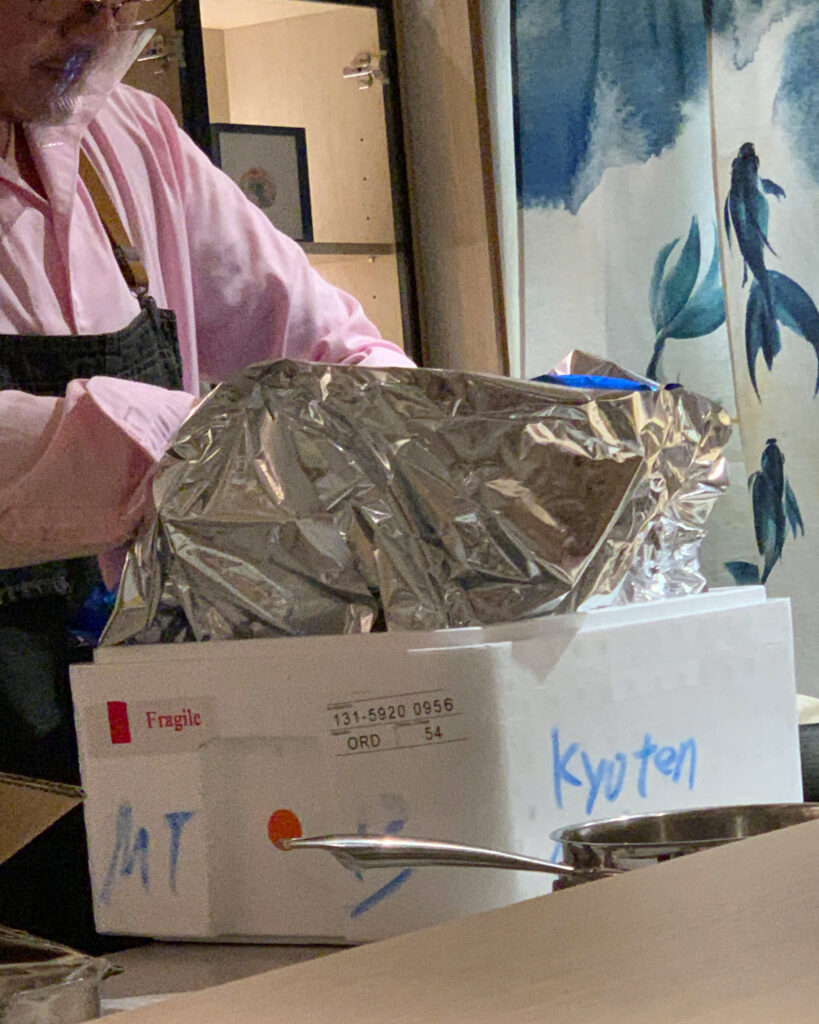

Wanting the best, nonetheless, does not mean getting it. Top quality Japanese seafood, when it does not go to auction (and command an exponential premium for what is sometimes only a miniscule increase in quality), is allocated on the basis of longstanding relationships between fishermen, purveyors, and chefs. When the global market for high-end seafood waned with the mass closure of restaurants during the pandemic, Phan’s private dining format and pricing allowed him to make some headway in what is a rigorous, loyalty-based system. He began to secure an even higher caliber of fish that has pushed his craftmanship further and come to uniquely define Kyōten relative to all other Chicago omakases.

The private dining format persisted through August of 2021, upon which the restaurant closed to remodel for a few months. During that period, Phan traveled extensively and immersed himself in not only other high-end omakases, but off the beaten path eateries in places like Flushing, Los Angeles, and Toronto.

This latter category of establishments, often serving unapologetic, regional Chinese cuisine, operates something like private supper clubs. They deliver customers an ultimate degree of control in shaping a luxury experience that goes beyond menus contrived to meet the lowest common denominator of the public’s (media-driven) expectations. They also accommodate corkage in a manner that encourages the celebration of fine wine to a degree that would cost thousands of dollars in a conventional fine dining setting. While sampling the cutting edge of New York City sushi was surely influential, Phan, who counts his time at Masa as the foundation of his craft, has seen in these other expressions of hospitality the future of luxury.

That idea, “new luxury,” forms the cornerstone of Kyōten “2.0.” Though Chicago is naturally disadvantaged when it comes to offering fresh fish from afar, Phan has found a way to source superior product than can be processed and aged to yield a superior flavor. The city, relative to more major markets touting top Japanese talent, is relatively free from the snare of tradition and “authenticity.” Diners have not yet been led to fetishize a certain image of omakase that rejects straightforward pleasure for the sake of tickling rootless cosmopolitan tastes. (Of course, you may still encounter that kind of sorry dick measurer who absolutely must regale the room with stories of the sushi they ate while visiting Japan).

You certainly do not mean to denigrate tradition, for it will always loom large over any chef who claims to offer an omakase. Rather, it is worth probing how some sense of “this is how it’s supposed to be done” chiefly acts as a form of social currency for well-heeled travelers to look down their noses at aspirational fine diners. You are not talking about flagrant “sushi sins” like dunking your nigiri in wasabi speckled soy sauce, but rather a kind of masochistic defense of certain stylistic decisions that prove maladaptive in a new environment. You find that some of the most supposedly liberal people possess totally retrogressive views when it comes to the development of cuisine. No recipe, no technique, no tradition is sacred if it is thoughtfully commandeered in pursuit of deliciousness. The reflexive process through which diverse forms of cookery adapt themselves to new terroirs comprises the lifeblood of the art.

So why should Chicagoans stand going to a place like Mako when they reliably find the portions too small and leave in search of a burger? Why should they bow before the altar of Michelin and its media sycophants that insist you must suffer through a paltry experience if you hope to seem “cultured”? Kyōten, from the start, has served larger slices of fish on larger grains of rice. The restaurant has bent the rules a little bit in satisfaction of its native population. Those decisions do, perhaps, irk some. But do such people not have plenty of other options? Must they suffocate the one place that bravely aims to please a different, yet significant, audience due to some sunk cost spent learning how to appreciate things the “right way”? Such reactions smack of insecurity and only work to deny the self-determination of Chicago’s dining scene.

“New luxury,” as embodied by Kyōten “2.0,” is more like a return to a kind of luxury untainted by contemporary consumer culture. It does not trade in the symbology of refinement that a conspicuous class of customers love to portray: a photogenic dining room, a fancy wine label, a doting itamae, and healthy portions of caviar, uni, tuna, and truffle (sometimes combined together). For such symbols, to all but the most discerning diners, act only as transmitters of clout. They lead the audience to judge their own experience on the basis of this or that totemic luxury ingredient rather than a sincere engagement with craft. They perpetuate a lazy heuristic that is used to judge quality and make every venue feel interchangeable so long as it reaches a certain threshold of visual appeal. This acts to sap creativity as chefs cater to the expectations of their most superficial, social media savvy customers.

Kyōten “2.0,” to be honest, does tout a beautiful dining room and an exemplary selection of wines that includes the world’s most coveted labels. Yet Phan centers every aspect of his experience around a sense of the singular. You pay to engage intimately with him (and not the apprentice or the apprentice’s apprentice). You appreciate music, design elements, and a beverage selection that have been personally curated by the chef. You sample a range of seafood selected at market for particular, sometimes “once in a lifetime,” qualities that transcend shallow associations or hierarchies. Phan shares his enthusiasm for the product and attests to its virtues and rarity. He makes clear that, as a chef, he respects and transmits whatever bounty nature shares. Harnessing those riches from the sea, he prepares them in a manner that privileges his guests’ sensibilities with some (but not slavish) devotion to tradition.

The whole evening is steered by a sense of ease and frankness that demystifies omakase and opens the door, unlike any other such restaurant you have visited, to a sincere engagement with the genre. No two meals at Kyōten “2.0,” just like its predecessor, are ever alike. You pay a premium not to go through the motions of the one-size-fits-all experience you saw someone else enjoy online, but for the culinary equivalent of haute couture.

Though every fine dining restaurant promises a special experience, visiting Kyōten (like visiting Smyth), reveals just to what degree the guardrails are up at every other place. Phan, like Shields and Feltz, embraces the entropy that truly seasonal cooking necessarily entails. The chef takes risks every night in order to reward his diners with some form of decadence they have never seen before. (And that is not to ignore that Phan always has a range of classic preparations in his holster).

As consumers routinely trade down in some categories so that they can trade up towards the ultimate luxury in others, Kyōten’s ticket price does not seem so steep. There is a time and place, perhaps, to stuff one’s face with maki, but you would be a fool to waste money visiting Mako or Yume a couple times rather than simply save the money and splurge on Kyōten once.

After a short period of private buy-outs in late December through January, Phan launched his “2.0” concept in February of 2022. The pricing of $440-$490 per person (depending on the day and inclusive gratuity) preserves all the quality of the prior format while, once more, allowing multiple parties into the space.

You will take that date as a starting point to engage with what’s new. As usual, you will condense the sum of your experiences into one cohesive narrative.

Let us begin.

The corner of Armitage and Campbell is as noisy as ever, but the bustle of the Blue Line makes stepping into Kyōten feel serene. Nonetheless, now more than ever, you could be forgiven for missing the entrance.

Past the Redhot Ranch (one of Phan’s favorites), the tattoo parlor, and the Mediterranean grill, the restaurant is tucked into a blocky, modern apartment complex that, thus far, has spurred little other development on the surrounding block. That might be a good thing, for the street, apart from the horrendous road construction to the east, quietly counts a number of exceptional establishments littered among a mixed bag of residential buildings and businesses to the west. This stretch of Armitage, this unheralded slice of the city, seems like an unlikely home for one of Chicago’s most expensive meals. When you come to the door marked “2507” and see that it’s papered over from the inside, it’s not unusual to second guess yourself.

Phan, as idiosyncratic as ever, spurns the luxury marketing playbook that says you must coddle and entice customers every step of the way. Yes, Kyōten maintains sterling averages on the major review aggregate sites, but the restaurant’s brand is not one that shouts for attention. Its Tock page, where would-be guests grapple with the ticket price, is free of the frippery that characterizes competing omakases. The description promises “an intimate…experience…serving sushi with bold expression of character grounded in…purity, harmony, and balance.” The boldest claim, perhaps, is that the chef “uses some of the world’s greatest ingredients from Japan and beyond.”

Kyōten’s social media posts are few and far between but resonate with a level of genuine emotion rarely seen from Chicago’s chefs. Phan reposts guests’ stories a bit more frequently, offering a peek at some of what lies in store. But future diners, otherwise, have little to go on. The crop of reviews that appeared upon the restaurant’s opening are now dreadfully out of date. They describe a different experience in a different setting at a different price and totally discount Phan’s exponential growth as a craftsman year after year. Some testimonials, like that of Oriole’s Noah Sandoval, remain more salient. But Kyōten remains something of an unknown quantity until you step through papered over door. You do not doubt that the most lovely signage will some day beckon patrons inside, yet, for now, the mystery forms a key part of the fun.

Stepping through the threshold, you find yourself in a dramatically lit waiting room with a few chairs, a bench, and a glowing gradient of gray paint on the walls. The scene does not exactly scream “expensive sushi,” but the setting is sleek enough to confirm you have found the right place. In one corner, a shoji style door emits warm rays from the restaurant proper. You hear the hum of music and, more faintly, the percussive notes of the chopping and slicing Phan does in preparation for the meal.

Before you can deduce much more, the door slides open. José, Kyōten’s front and back of house dynamo, greets you. He relieves you of your bag and bids you to enter the restaurant’s inner sanctum. There, he designates your seats and hangs your jackets before going about wine service for the bottles you brought along.

José is that rarest sort of hospitality professional you have only encountered a handful of times in your life, and he has now worked with Phan for several years. In earlier times, Kyōten has comprised a team of three, but, in this new and most luxurious era, it is telling that the chef counts on only one man to help engineer a superlative experience. José welcomes guests, curates the music, pours beverages, serves plates of food, and ducks back into a rear kitchen to assist with certain aspects of the cooking (allowing the chef to maintain pride of place in front of his diners).

Mechanically, his work demands an insane level of concentration and constant engagement with some of the most discerning customers in Chicago. José does not only accomplish this with aplomb, but he, after so long, as really formed part of the heart and soul of the restaurant. The soft touch and degree of sincere warmth he transmits to his guests sets the mood and forms the perfect counterpoint to Phan’s own acerbic style. The two make a brilliant team that demonstrates just how much is possible when a small enterprise is fueled by trust and passion. You can only liken the pairing to Japanese omakases that are run by a chef and his partner (or even his mother) and that beguile customers with their joint sense of devotion.

José’s deferential and earnest tableside manner has become even more consequential now that Kyōten boasts a new and luxurious setting. Such trappings, when paired with hovering robots for staff, can leave you feeling cold (if not intimidated). But Phan and his counterpart balance a sense of refinement with the kind of ease that invites their guests to sit back and relax.

That, indeed, has never been easier, for Kyōten can now claim an interior design that commensurately reflects the artistry of its chef. Structurally, the most important change comes from the reconfiguration of the sushi bar. Phan formerly worked along an L-shaped surface that painted him into the corner of the room. Now, however, the bar spans one continuous, horizontal length that runs parallel to the windows that look out onto Armitage. This barrier ensures that all guests are oriented in the same direction (whereas before one or two diners would be positioned perpendicular to the others). The resulting sightlines grant a greater sense of privacy between parties while establishing clear a sense of “frontstage” and “backstage.”

That dichotomy, in which Phan commands guests’ forward attention while José conducts service from out of sight, lends the omakase a greater sense of showmanship. The chef need not even call undue attention to himself to draw on it; rather, he can simply maneuver throughout the space, handle his tools, and prepare the meal to captivate his audience. Each motion, each detail is lent gravitas by the centering of diners’ concerted energy on the same area of focus. Kyōten’s ticket price guarantees you a front row seat no matter where you are positioned along the bar. (And, though it is easy to favor being seated directly in front of Phan’s cutting board, the chef works the entirety of his stage as he goes about the diverse array of techniques that shape his menu).

The sushi bar itself is rendered in a familiar, lighter tone of wood. It retains a ledged design in which the diner’s eating surface is positioned about nine inches lower than the top of the counter. This intensifies the feeling of Phan being on stage and ensures that each piece of nigiri he places on the trusty blue-grey slabs really shines. This perspective empowers patrons to bring the eye of their cameras close to the finished product, and the level of detail yielded makes for mouthwatering photos.

Kyōten’s remodel has extended the aesthetic of the sushi bar into a complete tableau that comprises two sets of rear cabinetry, a central backdrop (done in a paneled kumiko style), and slanted ceiling segments that are illuminated by strip lighting. The color tone of the counter is also matched by new flooring, a wine storage cabinet (located up against the windows), and wooden dividers that serve to separate parties when seated.

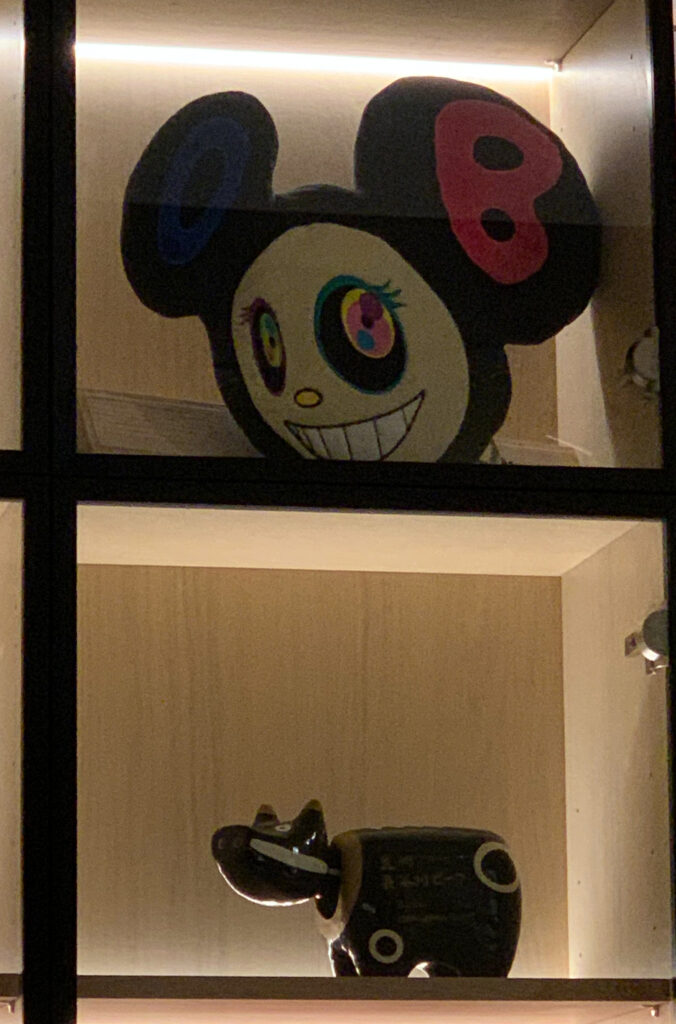

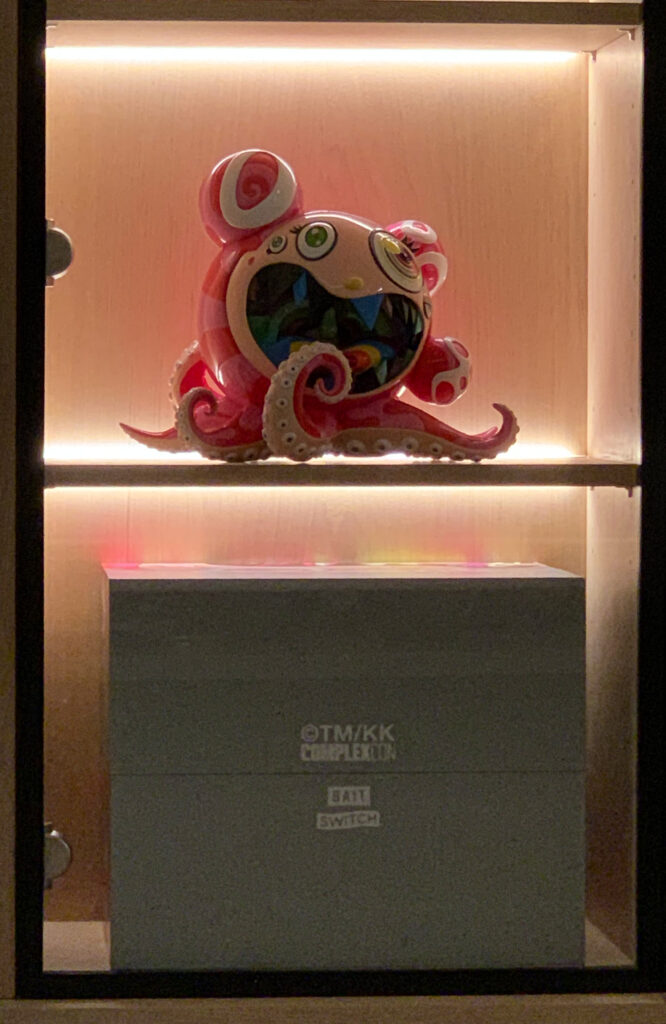

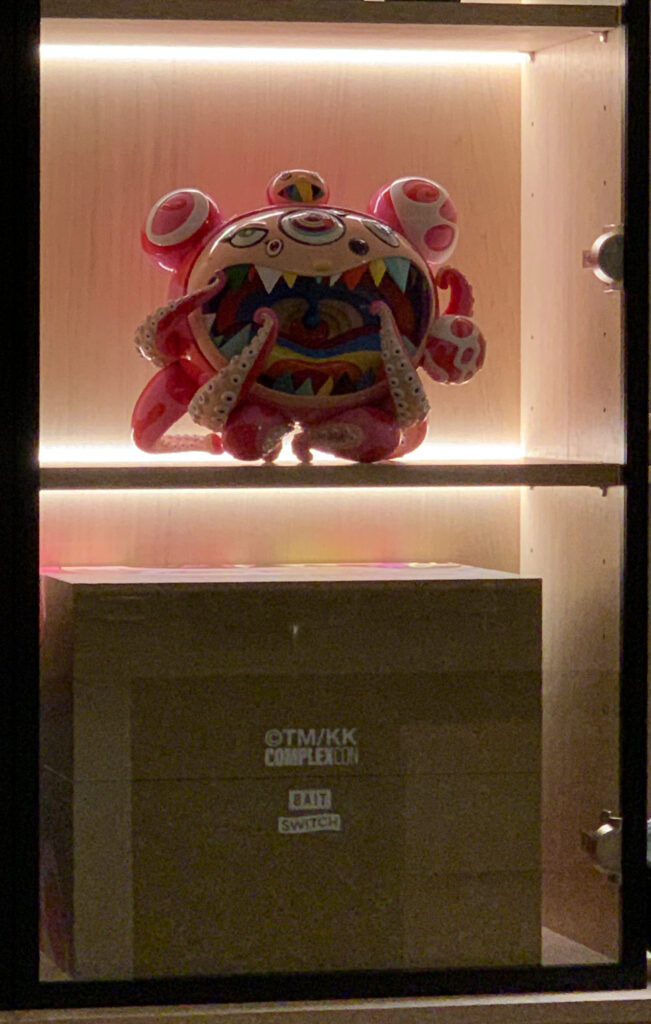

Of these elements, the set of cabinets and backdrop that define Phan’s “stage,” along with the dividers that demarcate different groups of guests, are the most salient. The array of shelving that bookends the chef’s space provides him with a golden opportunity to tacitly express some element of his personality. Just as Phan once showcased a towering stack of multicolored uni boxes in one corner of the bar, he can now elegantly display a few choice containers in one particular cubby. Others feature ceramic vessels, a cow sculpture (related to wagyu purveyance), and several pieces designed in collaboration with Takashi Murakami. These include a plush modeled after the artist’s And then, and then and then and then and then as well as two limited edition vinyl sculptures: Mr Dob/Dobtopus A & B (2 Works).

The tentacle details that feature in the latter pieces are particularly striking. They ground the sculptures in their setting by referencing, through their eerily realistic curling tendrils and suction cups, the ugly reality that butchering seafood entails. (At the same time, they call to mind Phan’s signature braised octopus and avocado preparation). However, the tentacles quickly yield to a hodgepodge of multicolored teeth, eyes, and protuberances set upon striped pink bodies. The pieces are both hideous and playful. They disturb but, somehow, draw you back in. The sense of alienness they embody connects you to the restaurant’s ingredient sourcing. The chef always has something new to share, something that is seemingly disgusting (like milt or ankimo), but that ultimately tastes wondrous. That tension, the leap patrons must be prepared to take, strikes right at the core of the omakase tradition.

While Kyōten’s new cabinets provide the viewer with plenty of eye candy, the center backdrop that frames Phan’s work is just as consequential. The woodworking, as you have previously mentioned, is intricately executed in accordance with Japanese style. The pattern is not overly complex in its essence, yet the sum effect is certainly pleasing to the eye. Most importantly, the offset screens revolve around a circular window that acts to channel all of the room’s energy towards a distinct focal point. This central marker blocks Phan’s movement vis-à-vis the “stage” and diffuses viewers’ attention to either side of it. Lost in the details of the wood, the cabinetry, the chef’s knives, or a lone orchid, the audience easily grows entranced. For they need not tune in to every moment of the cooking but can zone in and out at will, awash in the larger aesthetic experience derived from the thoughtful design of the sushi bar. The full array of details seen on the other side of the counter lend a sense of character that more concocted expressions of interior design (à la Mako) complete miss.

The dividers that separate different parties complete the effect. The presence of the wood-paneled and plasticked barriers, surely, has something to do with post-pandemic jitters. Nonetheless, their design matches the restaurant’s overall aesthetic beautifully and you think they are there to stay. The front portion, made solely of plastic, juts over the counter and ensures that guests, no matter where they are seated, always retain a full view of Phan’s movements. The larger part of the divider, which touches the floor, features the same kind of interlocking wood seen elsewhere throughout the space. Here, however, it serves to somewhat obscure diners’ view of each other.

Other omakases, indeed, have experimented with such separators, yet their presence at Kyōten, combined with the move away from an L-shaped bar, is utterly genius. No part of the new design, perhaps, speaks more to Phan’s deep understanding of consumer psychology and the pitfalls of coastal sushi culture.

Every group of patrons, nestled behind or between such a barrier, retains the highest level of intimacy possible. They can converse with the chef or each other at will without provoking interaction with any other guests. This sidesteps the kind of “foodie” dick measuring and detestable “sushi bro” culture that have poisoned the enjoyment of the craft in more mature markets. This lends each party the full power to enjoy a special evening amongst themselves, averting any errant interaction that might spoil the mood and stymie the sense of luxury such a pricey experience demands. Personally, you prize the ability to bring a sizeable volume of wine to the restaurant (via corkage) without attracting undue attention. Practically, Phan naturally commands attention, and the dividers enable him to connect with each group of customers in a controlled, personal manner.

The real beauty of this design element, nevertheless, comes from its permeable nature. There have been occasions, towards the end of the meal, where conversational barriers between parties naturally break down and a toast, perhaps, is shared. José, ever observant, can easily remove the separators and allow patrons to better see and speak to each other. This fluid, situational sort of design represents Phan’s “new luxury” at its best.

The chef prizes delivering an exceptional experience to his guests that is as pure and personal as possible. However, when it becomes clear that the groups he is hosting might enjoy a higher degree of interaction with each other, he can easily accommodate it. There is no “one size fits all” solution to delivering a superlative omakase, yet Kyōten has developed a tool of great consequence that, for your taste, guards the essential spirit of the meal against outside influence. It enables the chef to use his discretion in marrying distinct groups that, once they come together, might conjure a magical memory. Likewise, he can compartmentalize opposing parties (you, for example, and an influencer type) to limit any potential friction. In this manner, Phan guarantees that he can always put his strongest foot forward within a controlled environment that is absolutely singular for each customer.

Other notable elements of the restaurant’s remodel include floor-to-ceiling screens that cover the windows and shield all but diners’ silhouettes from outside observation. There’s a sleek standing wine fridge, placed adjacent to the aforementioned storage cabinet, that keeps the restaurant’s pricier selections at the perfect temperature. In the corner, the previous standing bar remains as an operational hub for José’s front of house work. However, it is now distinguished by the painting the hangs behind it (and once featured as the central decorative element behind Phan’s sushi bar). Recessed floor lighting now leads guests towards redesigned bathrooms that boast attractive sinks, backlit mirrors, and a state-of-the-art Japanese toilet.

Back in the day, Kyōten’s bare bones aesthetic provided an ironic juxtaposition to Phan’s refined fare. The restaurant provided a food-forward, no frills experience befitting Chicago’s broad-shouldered appreciation of substance over style. Of course, the chef worked to fill the space with a degree of heart and soul that transcended more shallow signifiers of “luxury,” yet there is no doubt that a certain segment of customers expects a particular range of niceties when forking out a couple hundred dollars per person.

Now, in accordance with a price point more than double his opening figure ($220), Phan can proudly host his guests in one of the city’s very finest settings. Kyōten avoids the cold, empty feeling that pervades places like Ever and Alinea. Rather, the restaurant feels more like Smyth or Oriole, in which high quality materials are married to an overarching sense of personality and warmth. In fact, emotionally, Phan’s sushi bar goes beyond its lauded brethren. It strikes you more like the chef’s home, a natural habitat that acts as a “stage” without pandering to any contrived marketing demographic. The rarefied setting shatters any sense that one has stepped inside a mere business, that one is an interchangeable vessel for fish and rice. Entering the space marks the fulfillment of a gastronomic pilgrimage that has not yet been promoted to death (and spoiled) via social media.

Kyōten makes you feel at home in a way that goes beyond both Chicago’s fine dining stalwarts and New York City’s finest omakases. The chef is the embodiment of luxury that does not take itself too seriously but does not compromise on any creature comforts. Guests who might raise their eyebrows at the ticket price will, after passing through that papered up entrance, quickly realize they have entered one of the city’s most special establishments. The fact that Kyōten has remained a bit coy about its new trappings deserves respect, for it empowers the space to confound expectations and charm patrons piecemeal while preserving a sense of wonder.

After thoroughly appreciating the ambiance, you take your seat at the sushi bar and turn your attention to the beverage list. Fundamentally, you still believe Kyōten to be the city’s finest destination for wine collectors. The $50 corkage might seem high at first glance; however, the restaurant places no limit on the number of bottles one can bring. Further, the sum must be judged against a rather fairly priced pairing ($140) and a generous selection of wine, beer, and sake that comprises excellent options under $100 as well as absolutely top-tier selections fit for a special occasion.

Pairing Phan’s ever-changing cuisine with Champagne, white wines, and lighter reds from your cellar represents, for you, the absolute height of Chicago dining decadence. And José, as if he already does not stay busy enough, does a superb job conducting service. You particularly enjoy his touch of placing bottles and ice buckets on a rollable cart that can be positioned behind guests and accessed at will.

But, putting your own preference aside, Kyōten really shines in how it approaches beverage service for the unwashed masses. The “Beverage Tasting,” as the restaurant labels it comprises top value producers like Roger Coulon, Schäfer-Fröhlich, and Benjamin Leroux with bottles that have a bit of age on them. (Leroux’s 2012 Savigny-lès-Beaune 1er Cru “Les Haut Jarrons” is a particularly wonderful selection relative to the sort of Burgundy that typically finds its way onto accessibly priced pairings). Those producers are joined by thoughtful selections spanning categories like white Bordeaux, Junmai Ginjo sake, and Honjozo sake that partner naturally with the cuisine. You have even seen Phan boldly serve Fabio Gea’s “DNAss,” a biodynamic Nebbiolo, alongside his tuna!

Though you enjoy many of the restaurant’s current pairings, your praise is primarily philosophical (for particularly selections are bound to come and go with time). You have described before how fine dining restaurants use tiered beverage options to goad diners towards spending just a little bit more on their “once in a lifetime experience.”

Smyth and Alinea, for example, maintain three levels of pairings: “normal” (both priced at $145), “reserve” (at $215 and $235 respectively) and “ultra” (at $355 and $395 respectively) discounting non-alcoholic options. Premium seating at both restaurants (Smyth’s chef’s table and Alinea’s kitchen table) demands that customers select either the “reserve” or “ultra” options to book. (However, it should be noted that Smyth does not demand prepayment for beverage selections and that one’s ultimate choice could be negotiated, perhaps by opting for the bottle list, upon dining there).

Oriole, by comparison, offers only a standard pairing (for $145) and a reserve pairing (at $275). You have praised this pricing scheme for splitting the difference between the middle and upper categories, offering guests an easy decision: to splurge or not to splurge (rather than settling for what might seem like a half splurge in the case of a three-tiered system). You have also recently honored Kasama’s sole standard pairing ($115) for offering an exciting diversity of quality selections at a highly accessible price.

Of course, there is nothing fundamentally wrong with offering a greater range of pairings to suit varying levels of wine appreciation and budgets. Rather, your wariness comes from past experiences that have shown that premium priced options often amount to nothing more than a parade of young vintages from well-known producers that offer little drinking pleasure or coherence with the cuisine. At their worst, expensive pairings reduce wine into a superficial totem where flashy labels and unyielding juice become something more like props.

The question, really, is one of consumer psychology and perceived luxury. Does the “special experience” continue to seem as special when one is unable or unwilling to pay for an extended menu, a supplemental course, or a top-tier wine pairing? Given that fine dining’s value proposition transcends the purchase of sustenance to instead offer a more emotional, performative pleasure, just how happy are those who know they have chosen the “cheap seats”?

That metaphor, actually, is not quite apt, for the cheapest seats in the theatre observe (albeit less ideally) the same show. By comparison, diners who go whole hog in purchasing the finest wares a restaurant has to offer do, indeed, secure a higher potential for pleasure. (Of course, they will have to judge post hoc if the premium paid was worth it). But is that not a better situation to be in than having chosen a lesser, ultimately disappointing option and wondering if you hadn’t still wasted your money by holding back? Yes, restaurants should excel at each and every price point offered, yet the knowledge that other customers are enjoying themselves more than you can be quite pernicious. Such a sensation denigrates the feeling of singular, personal, and limitless luxury these establishments labor to build by introducing an element of class insecurity into the equation.

Wine, thankfully, is easy for many aspirational fine diners to write off. The cuisine forms the main event, and any curated selection of beverages will seem like a treat. Yet certain special occasion diners who lack the experience to select a special bottle from the list or engage the sommelier for advice may be nudged towards a premium pairing. Who wants to say “I love you” or “happy birthday” in a “standard” way? Who can bear to compromise on giving their significant other the very best, the “ultra,” when the server presents such a hierarchy before you at the table? No, a ”standard” pairing is not quite the cubic zirconia of beverage selections, but it creates a situation in which consumers who lack vinous knowledge are prodded towards wasting their money on something they cannot recognize is a rip off.

Any truly great restaurant allays these fears by broaching the pairing options with a light touch that honors even those guests who are happy only to drink water. Kyōten deserves immense credit for delivering one solitary option that displays incredible value and generosity with its pours. Customers paying for one of Chicago’s most expensive meals will feel grateful not to be squeezed a second time upon encountering the beverage menu. Phan’s pairing honors his food by ensuring diners feel good about their purchase. They need not question whether such refined fare would have shined even more brightly alongside a pricier assemblage of pours. In fact, given that the chef embraces the role of describing each of the selections, the “Beverage Tasting” forms a natural extension of his culinary performance.

Still, if guests flip a couple pages further, they will find an “Extended Wine List” that is “curated by Chef, who simply collects delicious wines that he loves.” By burying these bottles a bit more deeply than the by the glass and pairing options, Phan can present an array of highly coveted wines without giving average customers sticker shock.

These include Champagnes from Bérêche, Krug, and Selosse; dry Rieslings from Schäfer-Fröhlich and Keller; red Burgundies from Leroux, Domaine Leroy, Dujac, and Soyard; other reds from Ganevat and Gea; and sweet wines from Domaine des Baumard, Dönnhoff, Keller, and Wittmann. The selection reads like a laundry list of coveted producers, and it is fair to say that the chef has curated a range of bottles that equals Chicago’s other great restaurants in discernment (if not in net number of options). The value Kyōten delivers with some of its pricing is rather superb too (particularly when you consider that each listing is already inclusive of gratuity).

The pricing on Phan’s Selosse “Initial,” “Substance,” Rosé, and “Millésimé” Champagnes falls well below their respective average national prices on wine-searcher. The 2002 and 2008 vintage bottles, in particular, cost half and a quarter of the secondary market price respectively! The chef’s assortment of 2015 Keller, along those same lines, aligns about evenly with each bottle’s national average (meaning customers need not pay the typical restaurant markup to enjoy such a wine).

Kyōten’s grand cru Burgundy, like Dujac’s 2017 Bonnes Mares ($1,500), Clos de la Roche ($1,000), and Clos Saint-Denis ($700), fall a bit above their national wine-searcher averages. However, readers familiar with the wines will know the degree to which prices have skyrocketed, and the restaurant is only charging something like a 10%-20% premium (compared to a double, triple, or Ever-style quadruple markup) relative to market price. Even Phan’s heart-stopping listing of a 2002 Domaine Leroy Romanée-St.-Vivant for $15,000 is fair relative to what you would have to pay to get your hands on such a bottle at retail or even at auction these days.

Nonetheless, what does it mean for Kyōten to offer what might be the most expensive wine ever listed at a Chicago restaurant? One’s instinct is to view the gesture as a bit braggadocious, but readers should remember that the bottle is buried well beyond where the average customer would stop browsing. Nestled among other selections that deliver rather good value, with gratuity included (so that guests need not reckon with an additional 20%-30% fee on top), you think the Leroy is not unlike a piece of fine art in its symbolic worth.

There is no question, considering the corkage, by the glass, pairing, and bottle options, that Phan invites his patrons to celebrate wine while dining with him. Kyōten’s beverage offerings do not only form an extension of the chef’s taste, but they reflect a generosity that encourages customers to splurge wholeheartedly when enjoying their omakase. Fine wine, in this manner, is not reserved only for those willing to spend double, triple, or quadruple what they typically pay at Binny’s. Rather, knowledgeable diners will spot a relative bargain within their price point and enjoy that rare gleeful feeling that comes with receiving a bona fide deal.

The chef honors what a great drink, across any category, can add to his food by wielding the restaurant’s largesse to secure allocations from suppliers and undercut the secondary market prices most collectors must grapple with. There is no more glorious way for a wine program to function, and you must count Kyōten on a very short list with places like Smyth and Oriole that deliver the same experience.

With this context in mind, that $15,000 bottle of Leroy forms more of a totem, a symbol, rather than something someone could conceivably imbibe. The wine is a testament to the fact that the chef will spare no expense in securing the absolute highest expressions of quality for his guests. It asserts that he will not compromise in delivering the “best” and, in doing so, elevates the experience for the vast majority of customers who could never imagine paying five figures on a beverage. For they have made it through the door at $440-$490 per head and can enjoy the same exact meal, made to the same standard, as someone who would conceivably spend thirty times the ticket price on grape juice.

The Leroy is not malevolently used to anchor the rest of the wine list’s pricing and nudge guests towards spending more than they intended. It is not a current vintage bottle that would make for infanticide if opened today. No, the 2002 Romanée-St.-Vivant is a prime expression of Phan’s ultimate taste. It is a promise that the chef has scaled the heights of connoisseurship as best as he can in search of the most extraordinary flavors for his guests. It signals he will continue climb as high as diners will let him while graciously ensuring that even those who do not drink a drop reap the same rewards.

A parallel, of course, can naturally be drawn to Kyōten’s ingredient sourcing, and you think that is the point. Those who encounter the $15,000 Burgundy must be heartened to know that the same discerning palate and deep pockets have engineered their meal. The restaurant’s new décor and expanded beverage program buttress the higher price point without any hint of artificiality. Each of the elements connects to a common philosophy that, insomuch as it reflects Phan’s personality, establishes a degree of immersion (and, dare you say, luxury) unlike anywhere else in the city.

If you were to critique the restaurant’s beverage program, you would only say that the extended wine list could benefit from a greater selection of Chardonnay and other dry white wines made from Chenin Blanc or Bordeaux-style blends. Likewise, you think a few more Champagne options, particularly focusing on Blanc de Noirs and rosé, would be nice too.

Nonetheless, you know that the bottles are first and foremost reflective of what Phan personally enjoys and that storage space, accounting for the pairings and sakes, might form a limiting factor. Most of the patrons you have observed do, indeed, opt for the “Beverage Tasting,” so there might be little reason to add to the restaurant’s cellar until some of those coveted bottles begin to be picked off.

On that note, while you find the chef’s personal engagement in describing the pairing charming, it demands a lot of work. The descriptions given tend to lean on a mixture of enthusiasm and general stylistic qualities rather than really educating customers on the nature of the wine and food pairing. You certainly think the pours are introduced well enough relative to other Chicago omakases (that lack sommeliers) and the affordable price point. You also think that diners tacitly understand that whatever they are drinking reflects an extension of the trust they have already paid the chef in serving cuisine they might not be entirely familiar with.

However, with a bit of study and practice, you think Phan could certainly present a more detailed picture of each wine’s technical characteristics (like simple descriptions of fruit, acidity, body) and how they interact with his fare. The exact nature of the interaction might not even be necessary to spell out if guests retain some sense of what the drink brings to the equation. There is no question that the chef’s love of wine is deep and sincere. The selections are not only sound, but largely delicious. But a little extra pomp and flourish in their presentation, if it’s a role Phan envisions himself playing in perpetuity, would play beautifully into the rest of his performance. It would really solidify Kyōten as one of the city’s most influential wine destinations, as nobody is better positioned to demystify the subject for consumers than the rambunctious chef.

With your beverage selections settled, the meal itself begins.

Though the current omakase utilizes the same quality of ingredients as Kyōten’s prior private buy-out format, the structure of the meal is somewhat different. When Phan played for just one party per night during the pandemic, he could experiment a bit more in accordance with particular tastes. That kind of captive audience, too, afforded the chef a bit more time to try out new techniques and compose complex cooked fare. The idea was to keep the creative juices flowing during a fallow period for the industry and to put in the kind of hard work that would pay dividends upon the dawn of a new era.

The chef took risks that often paid off, laying the groundwork for what would become a new signature creation. Other, harebrained ideas could sometimes fall flat, but it was always a treat to come along for the ride. There was never any question that you would leave the restaurant satisfied, for the ironclad quality of Phan’s nigiri always laid in store (along with that overarching guarantee that you would not leave hungry). Rather, indulging in the chef’s compulsions offered a rare window into his process and his vision for the new Kyōten to come.

As much as he likes to throw himself curveballs and cook on the fly, Phan is also a perfectionist who will hold back dishes that might, indeed, taste very good but fall short of his expectations. The private buy-outs dissolved this editorial instinct and exposed you to a more vulnerable range of expressions. Providing honest feedback to someone who demands (and so often delivers) the ultimate in quality could feel trepidatious. But that reflexive, interactive process forms the hallmark of the very greatest hospitality experiences, and it shone uniquely within a genre so often characterized by performatively stoic chefs who seem not to solicit any sort of feedback, good or bad.

Phan’s enthusiasm, throughout this private buy-out period, centered primarily on new, exotic fish he was able to source and how its composition (i.e. fattiness) changed from week to week. You saw the chef grapple with just how to butcher, age, and slice new ingredients to reveal their full potential. Flesh that might have seemed coarse on first encounter would, weeks later, display the most striking butteriness. In short order, the fish would reach its quintessence: a sublime texture enlivened by an artful balance of accompanying flavors. Phan looked beyond omakase’s usual luxury totems to craft dishes of equal pleasure drawn from comparatively unknown fish. Forging such a path brought the chef into uncharted waters, but he navigated them with aplomb.

Diners, in this manner, were exposed to a rather raw process of familiarization, refinement, and ultimate mastery that forms the essence the sushi craft. They peeked behind the curtain and helped Phan beta test creations that now form cornerstones of the Kyōten “2.0” experience. It was a wondrous era of great creative fulfillment for both parties in the exchange, and it allowed the chef to condense a process of actualization that might normally take many years to accomplish.

Still, as nostalgic as you feel for that time, there is no question that the restaurant’s “new normal” far surpasses the private buy-out format. Phan’s period of travel during the remodel forced him, upon returning behind the counter, to reevaluate everything he had ever done. The return of mixed groupings of customers (some experienced, some first-timers) has demanded that the chef put his best foot forward. Thus, experimentation is moderated so that the changing nature of each fish, rather than the techniques used to process them, take the lead. The whole pacing of the meal, as well as the nature of its presentation, has also tightened. So, to you, “2.0” feels like a supercharged version of the private buy-outs in which all the “best of” preparations remain alongside a healthy dose of entropy rooted in hyperseasonality.

Kyōten’s omakase has never been better packaged, and the array of bites it today comprises represents an absolute onslaught of unique and familiar fish brought to their apotheosis. A typical menu starts with five or six opening small plates followed by a sequence of around a dozen pieces of nigiri before finishing with dessert. The meal usually lasts exactly three hours, which makes for an impressive pacing per course (especially considering that dinner usually begins fifteen or twenty minutes after the reservation time). There’s an element of concentration to the experience that, as guests reckon with the third or fourth mind-blowing bite in a row, seems absolutely staggering.

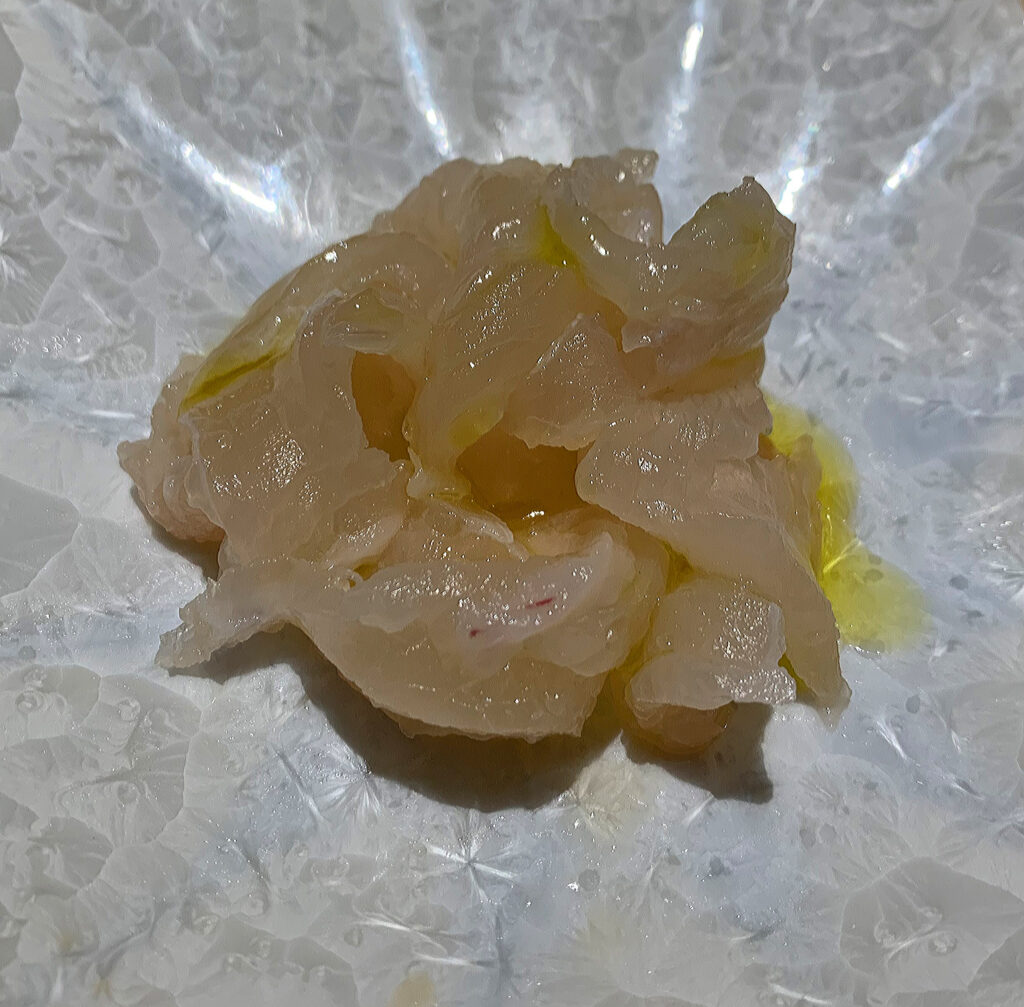

Phan starts the evening off with a sashimi of longtooth grouper. The fish, known in Japan as kue, can grow to over one meter in length and 100 kilograms in weight. It has a rather repulsive looking face but is “prized as a high-class fish” with “sweetness like a fatty cut of high-quality tuna belly meat [that] deeply impresses gourmets.” Kue are caught so sporadically that anglers sometimes refer to them as “phantom fish.”

At Kyōten, the grouper is sliced into thin, translucent strips with a glistening “pale cherry-blossom color.” The pieces of fish are lightly dressed in olive oil and fish sauce then loosely tangled together in the center of a shallow bowl. You pluck the slices one by one with your chopsticks and let them glide across the palate. The grouper’s firm flesh caresses the tongue before, with just a couple chews, unleashing a soft, gelatinous mouthfeel. The superpremium olive oil, sourced from Italian winemaker Valentini, transforms the preparation into a luxurious play on crudo. It envelops the fish with an added dimension of richness while the accompanying fruity notes, along with the latent umami of the fish sauce, work to enhance the kue’s subtle sweetness.

This opening dish of longtooth grouper has become a Kyōten “2.0” staple for good reason. It features a rare, largely unknown fish in a simple way, yet the texture derived from its flesh is sublime. The sashimi invites you to slow down and savor each morsel. It readies you for the series of intimate, tactile encounters that will come to define the omakase. All the while, there’s something sneaky about the sparse presentation: it does not scream for attention but keeps skeptical guests on tenterhooks until the very moment they take a bite.

Next, when in season, arrives ankimo. The term refers to a classic dish made from monkfish liver that is cured, steamed, and served with ponzu (a citrus-inflected soy sauce). To be honest, you never understood ankimo when it was served to you as part of high-end New York or Tokyo omakases. The liver was obviously highly prized by the chefs, and you always ate it with gusto. Nonetheless, it always struck you as a chalky, rather muted substance that felt far from luxurious. That perception, you will admit, could very well be due to divergent tastes between America and Japan.

But Kyōten’s ankimo has made you a believer. It is, without any doubt, the very best rendition of the dish you have ever tasted. The preparation not only fulfills monkfish liver’s status as a luxury product, but also affirms that it can equal top examples of foie gras.

Phan, for what it’s worth, does not pull any tricks. He serves one or two or three nuggets of ankimo in a shallow bowl with the traditional ponzu. Once again, patrons may be caught off guard by how decidedly unglamorous it all looks. Yet the liver is luscious and creamy when it strikes the tongue. It reveals a deep yet totally pristine flavor of fish as it melts on the palate that, once combined with the tangy, salty, and sweet ponzu turns absolutely hedonistic. The dish is an absolute flavor bomb and a delicacy you desperately look forward to tasting on any occasion it appears. The chef deserves real credit for rescuing the reputation of such a routinely manhandled dish.

The following dish, also when in season, ranks as one of the restaurant’s most challenging. It comprises shirako (“white children”), also known in English as milt, which refers to the sperm sacs of a male fish. The ingredient is harvested, in this case, from fugu (the famed poisonous pufferfish) and retains a rich, runny, and creamy texture.

On one occasion, Phan has lightly poached the milt, placed it atop a bottom layer of rice, and garnished the dish with a mixture of grated daikon and ponzu. On a later occasion, the chef has tempura fried the shirako before serving it with the same accompaniments. The former preparation, understandably, was all about textural purity. As each spoonful entered your mouth, the emulsified texture of the sperm took center stage. The bits of daikon and rice worked to help contrast and define the oozing, ethereal substance, but the mildness of the milt’s flavor drew attention almost solely towards its mouthfeel. That, perhaps, would prove difficult for some diners to withstand. At its best, it seemed like a fun dare to goad unsuspecting friends into sampling.

The tempura version, nonetheless, has proven to be a clear advancement of the dish. That bit of crisp outer coating, along with a more balanced ratio of milt to rice, has helped make the ingredient more approachable. The textural sensation now feels more familiar, like biting into a fried delight with a molten cheese filling (an arancini perhaps?). The flavors, meanwhile, are better defined by the rich, oily batter and more balanced addition of ponzu that adequately dresses every bit of the sperm. Kyōten deserves some credit for introducing its guests to such an interesting delicacy. However, Phan really deserves plaudits for engineering an improved method of delivering the shirako. His use of tempura is both impressive and disarming to those who might otherwise be grossed out.

During recent meals, as part of the opening small plate sequence, Phan has served up one of the crown jewels of luxury seafood. It’s a totemic ingredient of such rarity and character that you hesitate to even use the term. Abalone, that king of mollusks, is known for a rather robust, sometimes surprisingly chewy texture that reveals a subtly buttery, salty flavor. As with the ankimo, it was not always apparent to you what all the fuss was about. You knew, back in the day, that one of L2O’s specially designed fish tanks was used to house the bivalve, and chefs always seemed enthused to serve the product whenever you came across it.

Kyōten labels its abalone as kuro-awabi, a term that specifies the mollusk is sourced from Japanese waters rather than Australia, Canada, or California (where cultivation is prohibited until 2026). Kuro-awabi itself means “black sea ear,” a reference to the shape and color of the mollusk’s shell. This particular species is considered both the “tastiest” and the “best suited for sashimi” due to its “firm flesh,” pleasant smell, and “full flavor.”

Phan has served the abalone in several ways. The simplest of these have seen the bivalve sliced and served as sashimi or gently steamed in sake. The former preparation retained a hint of the brittleness you associate with the ingredient; however, the thinness of the pieces made the texture more appealing than you are used to. The use of sake in the latter preparation serves to soften the abalone’s collagen into gelatin, yielding thicker, softer nuggets that struck you with their meatiness.

Your favorite of the chef’s abalone preparations, nonetheless, is a little more involved. It comprises smaller, thicker chunks of the mollusk that have been given the same steam treatment. However, rather than being served as-is, they are used to crown a tangle of noodles dressed in an abalone liver sauce and garnished with sesame seeds. The combination transforms the luxury ingredient from something to be worshipped into a playful, hearty expression of deliciousness. The slight chew of the noodles enhances the firmer texture of the abalone while the undercurrent of flavor drawn from the bivalve’s liver helps extend the subtler notes of the meat itself. This dish is a brilliant example of how the restaurant uses coveted ingredients not as a crutch, but a jumping off point for something engaging and appealing to the average customer.

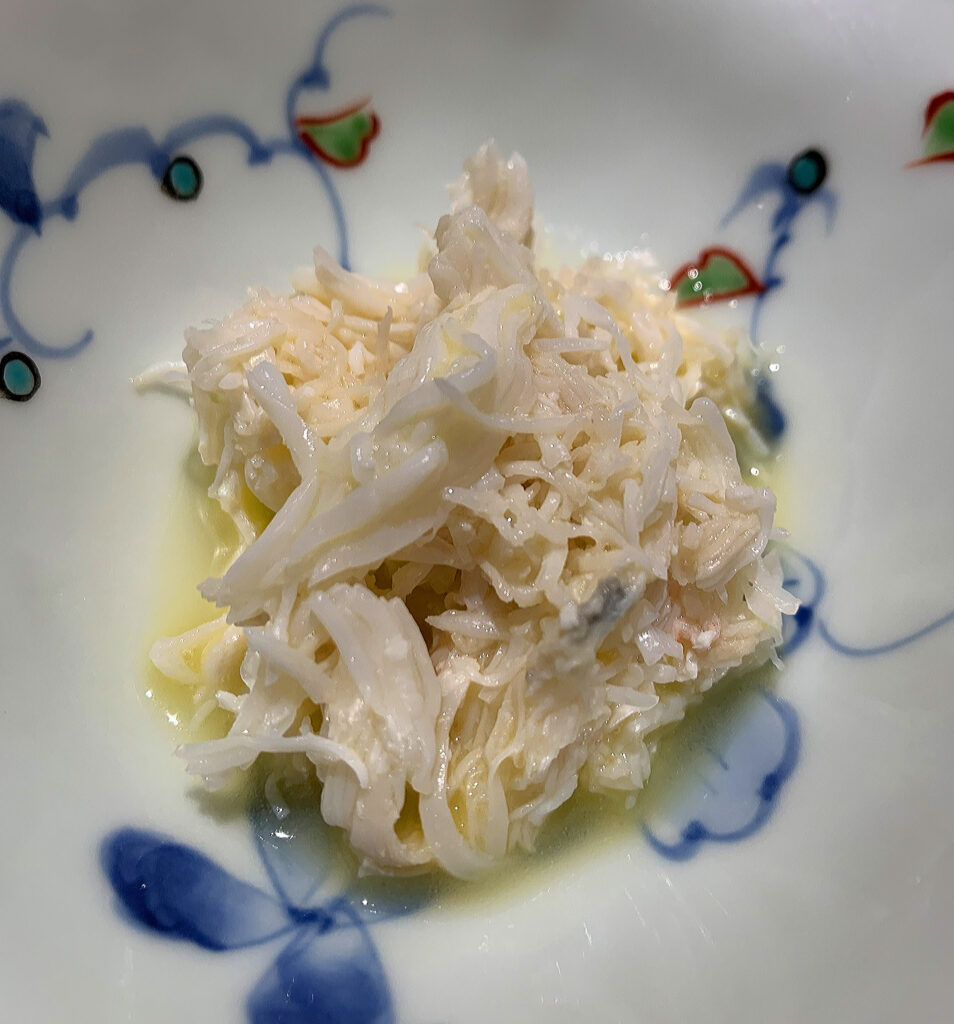

Crab, in some form, inevitably features as part of Kyōten’s opening small plates. That’s a good thing, for Phan has undoubtedly mastered the ingredient across a range of species and preparations. (Does the chef’s own crabby temperament give him a special, kindred understanding of the crustacean? You do not know). However, you do know that the restaurant consistently sources its product from Hokkaido, a seafood haven that harvests varieties like the horsehair, snow, and red king crab. Phan will switch between the exact type depending on the point of the season.

His treatment of the ingredient, nonetheless, tends to remain the same. The crab is boiled and its meat is finely shredded. (On occasion, you might receive a larger chunk of the leg). The crustacean is then tossed with its tomalley (the innards or “fat”), butter, and/or lemon. It might be garnished with furikake, some sesame seeds, or nothing at all. But the focus remains squarely on the delicate texture and subtle, natural sweetness of the crab.

Attacking the dish, you are amazed at how such tiny morsels of crab can strike with an intensity beyond the heaping legs and knuckles you enjoy at your favorite Chicago steakhouses. The shreds splinter on the palate, release their juices, and all but melt on the tongue. There is a level of purity and nuance to these preparations that is simply remarkable, and the serving always feels generous relative to the degree of satisfaction it delivers. That being said, these elegantly simple dishes do not represent the peak of Phan’s powers when it comes to crab. Their ultimate decadent expression, depending on the evening, arrives a bit later.

On rare occasions when the crab is not judged as being up to Kyōten’s high standards, the chef opts for spot prawn (or botan ebi). The ingredient is sourced from Hokkaido or Santa Barbara, depending on the evening, and is served in a similar manner: lightly dressed with lemon and butter then paired with its roe. Unlike the crab’s tomalley, which coats the crustacean with a viscous sheen, the prawn’s eggs function more like a caviar. The amber pearls top the dish and pop on the palate as you consume the tender pieces of flesh.

One of Kyōten “1.0’s” signature pieces of nigiri made use of Alabama’s Royal Red shrimp. The richly flavored and lusciously textured variety made for a showstopping piece, and Phan displays the same artistry with his spot prawn. The botan ebi is beautifully plump, subtly sweet, and bursts with succulent juices upon being bitten. The accompanying roe imparts a saline, deep sea quality that intensifies the delicate flavor while playing nicely off its smooth, slick texture.

Indeed, each piece of prawn delivers a level of satisfaction more often associated with crab, lobster, or langoustine. The dish is an ode to how high quality sourcing can turn a mere “shrimp” into a star, and it is well-positioned to please a city that has feasted on local species of the crustacean for generations.

Octopus, too, has been one of Kyōten’s signatures since its earliest days, and Phan’s pairing of the cephalopod with avocado must now be called a classic. Thankfully, the preparation persists as part of “2.0’s” small plates. The chef makes use of actual fresh octopus from Fukuoka (rather than the parboiled kind typically used at restaurants). He massages the tentacles lovingly before quickly boiling the creature and slathering slices in an avocado ponzu.

Guests are served a few choice nuggets of the flesh, which displays a clean, white interior color along with a burnished outer skin. Most of that is masked by the green of the avocado, whose thick consistency clings to all the tentacles’ nooks and crannies.

On first bite, the octopus displays the slightness firmness. However, that immediately yields to a texture you can only compare to rendered fat. That bursting, gelatinous quality marries beautifully with the mouthfeel of the avocado and the tang of the ponzu. The sauce underscores the octopus’s own latent sweetness, but the experience is primarily characterized by a full-flavored, “stick to your ribs” quality one normally only associates with meat. This dish remains the best preparation of the ingredient you have thus far tasted in Chicago. It would be hard to ever see Phan stop serving it!

As previously mentioned, the chef keeps one more preparation of crab up his sleeve for when the time is right. It stands, you think, as one of the most decadent, nostalgic creations you have tasted over the past few years. And there’s nothing particularly fancy about it. Rather, it reflects Phan’s personal philosophy of pleasing his audience on the basis of native tastes.

The combination is a simple one: crab and corn. It is made even more transfixing by way of a rather elegant temperature contrast: warm crab meat and cold corn sorbet. Though Phan has invested in a Pacojet to bring his sorbet to the highest molecular gastronomic standard, the chef has found that the advanced machinery cannot contend with his recipe. He uses 100% corn juice that cannot properly be frozen for processing via the machine. Thus, the sorbet remains more of a homespun effort that displays the surprising limits of top-of-the-line kitchen technology.

That is no tragedy, for the sorbet displays a smooth consistency and strikes your palate as perhaps the most concentrated expression of corn you have ever tasted. The crab itself is shredded and mixed with its tomalley and some sesame seeds (as seen in the prior preparations). When the two components mingle in your mouth, the result can only be called ecstasy. The intense corn flavor unlocks (but does not overshadow) the most pristine buttery-sweet flavor of the crustacean. The play of hot and cold, too, enhances your sensation of their marrying. Such a dish seems destined to go over well in the “Corn Belt,” but it really is extraordinary. Phan makes conjuring such an effect seem effortless.

The next small plate has debuted only recently, but you think it is here to stay. The recipe taps into some of the chef’s past experience and nostalgia, for he once worked for Nobu in New York City. One of Matsuhisa’s most signature preparations, of course, is his miso-marinated black cod. The dish is a signature across all of his properties and probably deserves credit for, decades ago, opening American minds to the riches of Japanese cookery.

Phan, if he’s being honest, will admit that he never quite liked Nobu’s recipe and has long been obsessed with improving it. For his rendition, the chef makes use of a premium black cod nicknamed umibōzu (in reference to a mythical sea-spirit said to attack ships) and Hatcho miso (also known as “emperor’s miso”).

Guests receive a glistening chunk of the fish that has been marinated, broiled, and boasts a few specks of char across its faintly yellow, lacquered flesh. The cod sits atop a small mound of rice with a bit more of the miso, sake, and mirin mixture at the bottom of the bowl. Diving in, the fillet displays a wonderful flakiness as it breaks apart. The fish is tender, juicy, and strikes you with a depth of sweet and salty flavor that invigorates its richness. Phan says that the miso he uses, often substituted by other chefs for a “cheap replica,” possesses a natural sweetness that requires no additional application of sugar. As you sop up the rice and the marinade at the bottom of the bowl, that rings true. The sauce is lip-smacking but in no way sickly, and it makes for a dish that is deeply satisfying.

Though the chef has signaled that serving the cod directly after the crab and corn might make for too much sweetness at once, he has undoubtedly struck upon another brilliant crowd-pleaser. The dish takes the essence of Nobu’s preparation and refines it for a new era. To your palate, it really does represent an improvement of the legendary chef’s recipe.

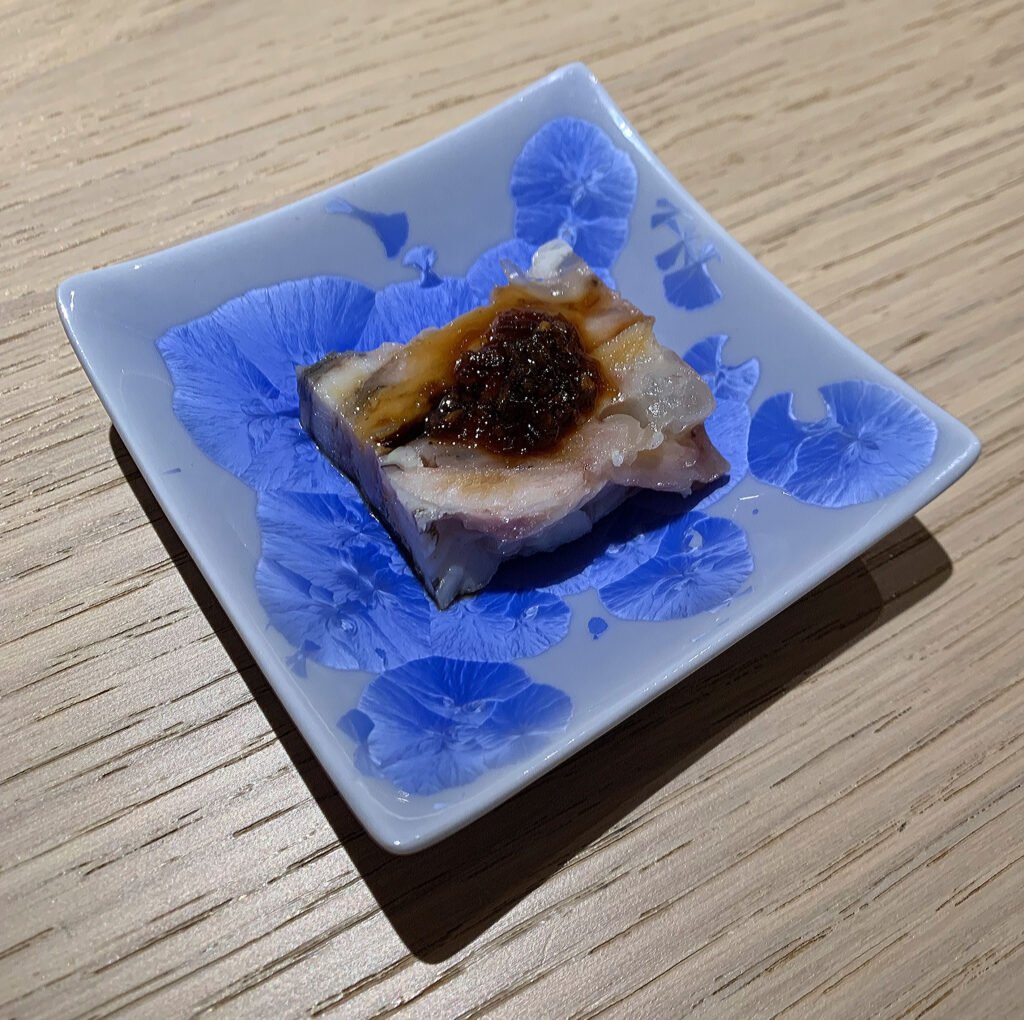

The next small plate is, perhaps, Phan’s boldest, and it winks towards the chef’s love of classic French cuisine. The recipe is a take on head cheese, a cold terrine made from various cuts of offal and other trimmings taken from calves or pigs that are set with aspic. Kyōten, cleverly, makes use of the longtooth grouper whose sashimi features so prominently at the start of the meal. Though the head cheese, as far as you know, is not made entirely from the head of the fish, sections like the cheeks have long been prized for their exceptional texture and flavor.

Guests receive a neat little square of grouper meat that has been tightly formed and topped with ponzu. Whereas a traditional beef or pork head cheese displays varying pockets of flesh and fat, you like that Phan’s version is made up of more cohesive strands of the fish that remain identifiable as they have been layered together. The terrine breaks apart cleanly when attacked with your spoon, displaying enough gelatinousness to hold its form without being obscured by the aspic. The texture, when the grouper hits your tongue, is firm and meaty. Nonetheless, it chews pleasantly (perhaps even moreso than a typical head cheese).

The accompanying ponzu serves to enliven the dense fish flavor; however, you think the dish still has some ways to go if it is to measure up to the rest of Phan’s creations. The form is exceedingly clever and technically sound. However, you think the preparation does more to show off the chef’s skill than it does deliver pleasure. Nonetheless, given the quality of most of the small plates, he certainly has earned the room to do so. And, since you have only seen the head cheese served once, it is sure to grow in time.

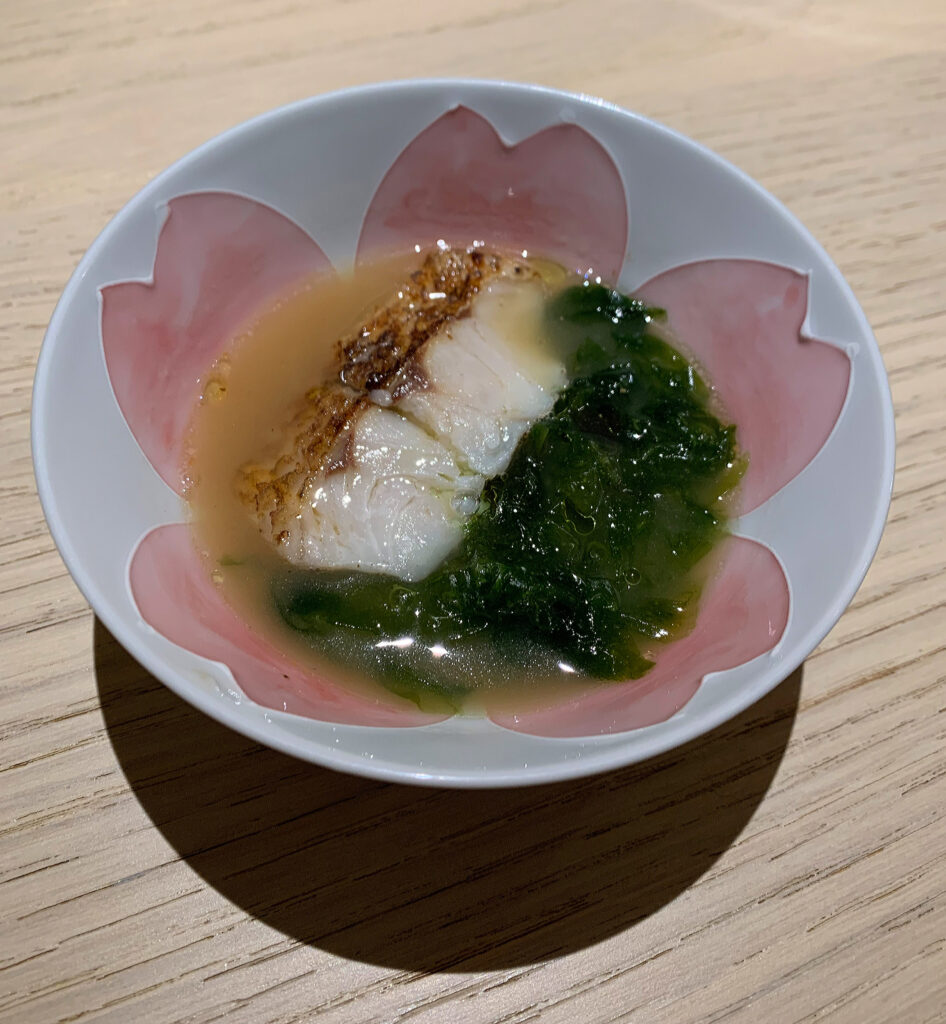

To draw his sequence of small plates towards a close, Phan has often served amadai, also known as tilefish. The species is known for excavating underwater burrows (sometimes digging within the same location for a lifetime) that they the use to shelter from predators. Otherwise, they are bottom feeders whose diet of shrimp, crabs, and clams develops a mild flavor that is itself compared to lobster or crab. For this reason, the fish is both highly prized and expensive. Though it rarely features as sushi, tilefish is utilized in a variety of traditional cooked dishes.

Phan fries his amadai in a manner reminiscent of his Kyōten “1.0” preparation. However, rather than handing the horseradish- and caviar-topped fish directly to customers, the chef now submerges it in a bowl of broth. The real benefit to frying the tilefish comes from how its scales puff up and crackle like Rice Krispies, and the current preparation boasts a much more delicate texture than before (owing to the fact it need no longer balance on your hand).

The crunching layer of skin yields to flaky, juicy flesh that is invigorated by the umami of the surrounding nori (seaweed) soup. Phan has thrown caviar back into the mix at times, but you think he has decided (and must agree) that the dish is better without it. The warmth and richness to the combination of fish and broth is appealing, and you think it helps soothe guests’ stomachs ahead of the forthcoming assortment of nigiri. However, you find that the amadai’s presentation has sometimes looked a bit muddled, and, while there’s great savory power to the preparation, it lacks one more complicating dimension to really sing.

Nevertheless, after amadai has fallen out of season, Kyōten has continued to make broth-based dishes a fixture of its small plates sequence. This points to the form being used less to feature the tilefish in particular and more as a transitional course to bridge the gap between cooked and raw.

Other examples have included wild madai, or red sea bream, poached in the same nori stock. Though lacking the crisp, alluring scales of the amadai, this fish comprises a denser, meatier portion with all the same tender, mild flavor. You think you prefer the sea bream to the tilefish due to how pristine the flesh seems. It is easy to break into and savor on the palate without any aggressive element of crunch. (Perhaps the amadai’s puffed skin, however texturally appealing, ultimately detracts from your appreciation of the rest of the fillet as a transmitter of the soup’s subtle character. Or, maybe, a bit of the oil used to fry the tilefish muddies the waters and, thus, the flavors).

Phan has also served an even simpler presentation of the nori stock with only a few pieces of fresh French white asparagus floating within it. When it comes to this dish, you have no complaints. The slight sweetness of the vegetable is wonderfully accented by the broth’s depth of flavor. The combination seems effortless and elegant and helps demonstrate the chef’s mastery. For each of the stocks he has made are consistently delicious, and such an element deserves to have some place in the flow of the meal.

The soups need not even be associated with any fish or vegetable to strike guests with their excellence, and, indeed, the chef has served up simple cups of lone liquid before too.

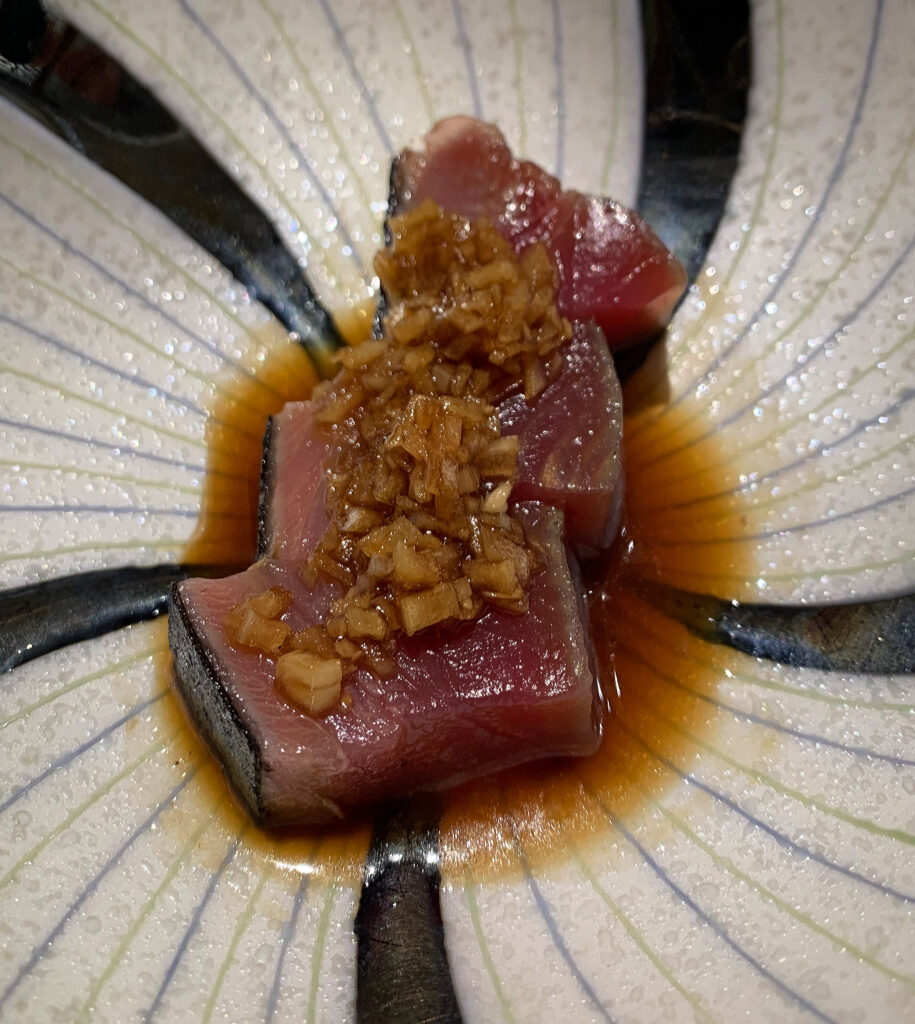

Kyōten typically bookends its small plates with another sashimi-style preparation that is somewhat a corollary to the longtooth grouper “crudo.” However, while the kue displays a lasting texture and mild flavor, Phan’s katsuo and sawara serve to shepherd in the top-tier nigiri that is soon to follow.

The former of these two, also known as skipjack tuna, is traditionally simmered, smoked, and fermented to make katsuobushi (or bonito), a key ingredient in the creation of dashi. However, the fish can also be used to make sashimi or sushi. It is often prepared tataki style: grilled on the outside but raw in the center. Phan adopts this method, which yields glistening pieces of tuna with a crisped outer skin and ruby red interior.

Relative to the bluefin species, whose flesh features in the most coveted pieces of nigiri, skipjacks are smaller, less fatty, and more sustainable. Still, what the fish lacks in textural nuance it more than makes up for with a robust, meaty flavor and mouthfeel. Phan’s preparation is lightly dressed with daikon and ponzu, which serve to balance the tuna’s stronger character. The skipjack displays a pleasing weight on the palate that quickly melts with each bite. The dish forms a wonderful introduction to the quality of tuna Kyōten serves and provides an important reference point guests can draw on when eventually tasting the fattier, more intricate cuts from the bluefin’s belly.

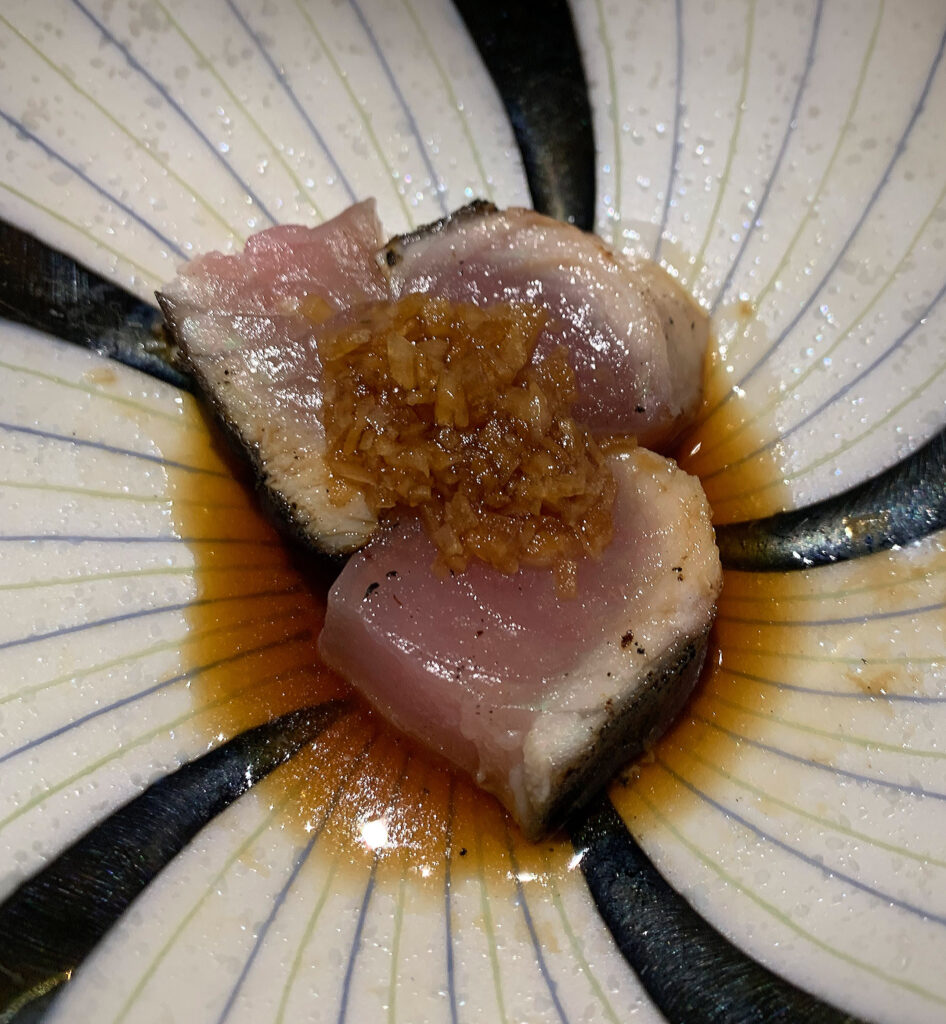

The latter of these two, also known as Spanish mackerel, actually comes sourced from Japan. The fish, which feeds on sardines, is known for a particularly rich yet mild taste alongside a high fat content that is sometimes compared to tuna. However, the sawara’s skin is typically left on the fish and seared (in the same tataki style) before it is sliced and served. Phan skewers a large fillet of the mackerel and conducts this process over an open burner at the end of the sushi bar opposite his cutting board. It’s a rather appealing thing to witness (should you be seated down at that end and otherwise unable to closely observe all the knifework).

Guests receive two or three pieces of sawara boasting a crispy, charred skin, a small layer of white flesh, and a larger, blushing white-pink interior. The fish is topped with that familiar combination of diced daikon and ponzu, but, in truth, it needs little help. The Spanish mackerel absolutely bursts with clean, meaty flavor when it reaches the palate. Its mouthfeel is truly extraordinary, with a soft, melting quality that is beautifully offset by that slight layer of skin.

You have long thought of both the katsuo and sawara bites as something like “fish gushers” given their bewitching combination of size and delicacy. They always present an early occasion to pour yourself a lighter red wine and revel in their weight and richness. Even after an onslaught of incredible small plates, the skipjack tuna and Spanish mackerel form a most welcome part of the meal each time you encounter them. That, you think, has something to do with their liminal status as part-sashimi, part-cooked. Such an in between state makes for an elegant, natural transition into the next chapter of the meal.

Phan’s nigiri, understandably, forms the main event. Guests pay the high ticket price to receive an omakase (rather than a contemporary Japanese meal more in the style of Yūgen, rest in peace). So they expect an assortment of totemic ingredients like tuna and uni to be served on top of rice, and they expect these pieces to blow Kyōten’s local (or maybe even national?) competitors out of the water.

The chef does not denigrate his craft by shoehorning such luxurious items in unnecessarily. They appear, as with everything else served at the restaurant, when their quality is judged to be superlative. However, Phan understands the baggage that most of his customers bring to the table. Both amateur and experienced sushi eaters become conditioned to a particular sequence of bites, and he works within this framework (while sometimes subverting it) to please them.

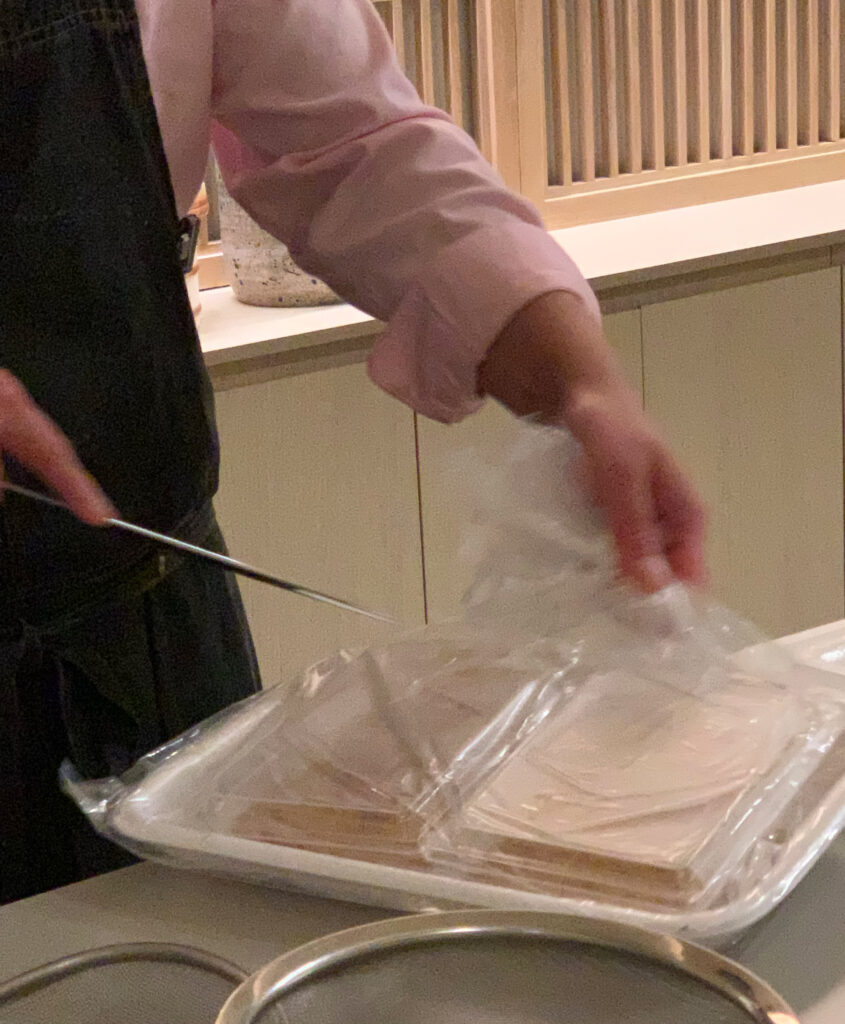

Kyōten’s inochi-no-ichi rice (one and a half times the size of typical sushi rice) remains the centerpiece, but guests will notice that the Phan’s knifework has now reached another level. Scoring a slice of fish (kakushi boucho) enables it to more closely adhere to the rice while displaying greater textural intricacy when it hits the tongue. Many of the toppings (neta) now possess deep grooves and ruffles across their surfaces that demonstrate just to what degree the chef engineers his nigiri to deliver the perfect mouthfeel. Visually, for this reason, Kyōten’s sushi immediately distinguishes itself from its Chicago counterparts.

Phan continues to practice the edomae tradition, which encompasses the treating and aging fish. Given that the restaurant distinguishes itself on the fattiness of its fish (rather than a “freshness” that is now easily attainable by everyone), these techniques are of particular use in bringing prime specimens of seafood to their absolute peak of flavor.

The ideal degree of aging must necessarily correspond to the flavor balance of Kyōten’s rice (carefully seasoned with vinegar), the amount of freshly grated wasabi used, and the application of a bit of soy sauce (when applicable). Even the character of Phan’s pickled ginger, a cleansing condiment that can seem like a soggy mess elsewhere, is distinct. These stylistic decisions, beyond all the work that goes into cultivating amazing textures, are quite consequential. For you find that Phan’s sushi excels in delivering a finished product that is engineered in accordance with Japanese tradition but flavored for a quintessentially Midwestern palate.

Achieving this is quite a tightrope walk since nigiri’s streamlined structure is prone to over- or underseasoning. The question ultimately becomes one of individual thresholds based on both genetic predispositions and cultural conditioning. Personally, you have found the majority of one, two, and three Michelin star omakases you have sampled in Tokyo to be lightly seasoned for your palate. Phan’s conception of flavor balance, by comparison, feels right on the money.

Another diner, drawing on different sensory equipment and a different range of experiences, might feel just the opposite way. However, you think Kyōten’s reverential yet locally-rooted approach to seasoning is often underrepresented among high-end sushi restaurants. Many chefs demand that customers cohere to an alien expression of balance for the sake of “authenticity” rather than working to charm them on their own terms. Phan, uniquely, has bridged that gap by translating tradition for a beef-eating, broad-shouldered population that prefers fuller flavors. Importantly, the chef does so without drawing on a wild variety of gimmicky toppings that distract from the fish. He is a sushi evangelist of the highest order.

Lastly, it is worth keeping in mind how the proliferation of small plates that begin the meal factor into the omakase sequence “proper.” Unlike Mako, in which substantial cooked fare interrupts flights of nigiri, Kyōten tantalizes guests with restrained portions of pristine fish and shellfish (and even a bit of soup) before any nigiri is served. This not only serves to quell any gnawing hunger that might detract from the appreciation of Phan’s sushi, but also calls greater attention to the rice. Moving from dishes that are more like sashimi to an interplay of fish and rice emphasizes what the craft is all about. Customers get a glimpse of the quality of ingredients through the small plates before experiencing how the chef’s touch works to shape them into their ultimate form.

This all makes for a great way to set the table ahead of the meal’s most electrifying sequence. (Often, after feeling so deeply satisfied by the small plates, you find it hard to believe that the best is left to come).

Phan, having already put some food in his guests’ stomachs, wastes no time in swinging for the fences. He starts off his nigiri with that most coveted, fetishized fish of all, tuna, and he presents the very finest cut he has on hand first.

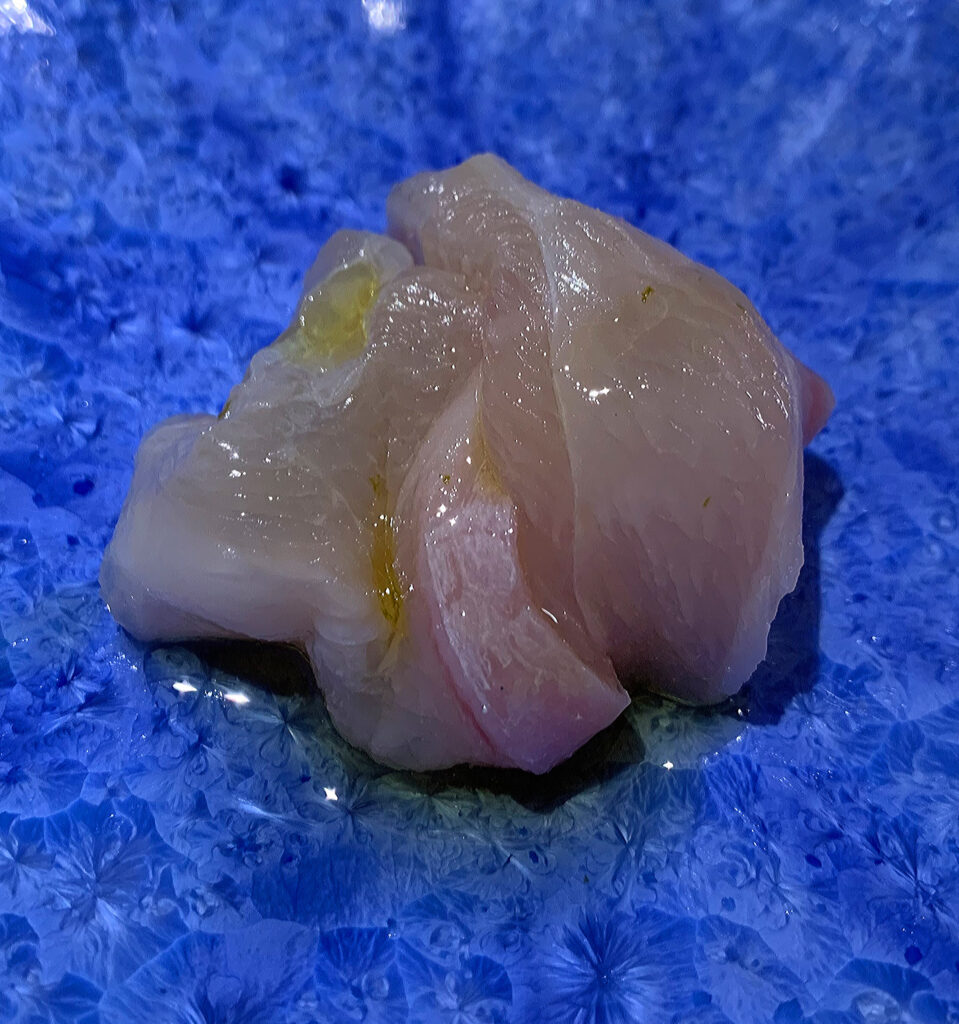

The exact terminology, however, changes depending on the evening. On one occasion, Phan described the piece as hagashi toro, sourced from a section of the tuna located “at the top of the tail or at the bottom of the belly.” This portion of the fish demands that the chef painstakingly remove small pieces of tendon and sinew, but the process yields a supreme tenderness.

On another occasion, the chef has described such a bite as a one-month-aged “back cut” of toro. Sometimes, it is just wryly called “toro,” but the texture and flavor are always exquisite.

There’s not much more you can say without expending all manner of needless hyperbole. Instead, you would direct readers to inspect and appreciate the subtle ribbons of fat that interlace the cuts of tuna. One can easily appreciate Phan’s knifework, of course, as well as some of the darker, browner tones that signify extended aging.

Kyōten fattiest expressions of tuna rank as the very finest you have tasted. The fish is both mouthfilling and utterly ethereal on the palate. The flavor is uncommonly deep and sharp (no doubt on account of thoughtful seasoning). Even that piece shown with the topping of wasabi was beautifully balanced on the occasion (the sharp, pungent quality of the root being moderated beautifully by an abundance of melting fat).

When it comes to what is, for many, the absolute crown jewel of omakase, Phan has noticeably pushed his sourcing standards and technique to the extreme. He serves the kind of tuna that spoils you for anywhere else. It fulfills the ingredient’s totemic luxury status in a way that is so rarely seen.

Kyōten’s nigiri sequence typically continues with yet another cut of tuna. Phan ensures that his guests appreciate the fattiest, most delicate texture first before turning towards more robust (though, depending on personal taste, even more pleasing) expressions of the fish.

That can include chu-toro, a “medium fatty” cut of tuna sourced from the back or stomach. The piece displays a deeper tone of red than the toro with a texture that possesses a slight melting quality alongside greater meatiness. Its flavor is broader and a bit more distinctive than its fattier, more delicate counterpart. However, the chu-toro may be favored by guests who enjoy a bit more “chew” to their fish (relative to the toro’s gentle caress).

Despite the traditional hierarchy (in which fattier is always better), you have a hard time saying one piece is better than the other. Each expression, cut from the same superlative tuna, simply reveals a different dimension of the product. And both grow in stature as you compare and contrast their distinguishing elements.

Phan has also served setoro, “a precious part with very little meat found next to the dorsal fin” of the tuna. This obscure piece, which you have never encountered before and is “not available except to regular customers in almost all sushi restaurants,” marries some of the meatiness found in less fatty cuts with pockets of intense marbling that melt like the finest toro.