With every passing year, yet another attempt at ranking restaurants rears its ugly head. For an uneducated public can only resort to “best of” lists in an attempt to buttress their lack of connoisseurship, and what restaurant can ever resist the marketing allure of a tidy placement on a numbered list? Methodology be damned, just paste some fancy pictures, a fawning blurb, and that all-important numerical order together and you, too, can envelop yourself in a contrived “authority.”

Perhaps you are being a bit unfair to Opinionated About Dining—OAD for short—which has published some form of restaurant ranking since 2007. But, surely, such a ghastly moniker for an organization must invite some level of scorn. Even a petulant child pushing their serving of peas off of the plate can be described as “opinionated about dining.” Society is saturated with all manner of self-righteous missives on matters cultural. Forging an inclusive, distinctive dining scene demands fewer iconoclastic “opinions” and greater, deeper understanding of the subject matter (though you might be a bit biased).

“Outspoken entertainment industry veteran” Steve Plotnicki, OAD’s founder, sounds like just about the last person anyone should listen to in search of some “objective” quality. Sure, you appreciate the impetus behind his list: offering a crowdsourced counterpoint to the murky machinations of Michelin and William Reed Business Media’s “World’s 50 Best Restaurants” ratings. But is it not deliciously ironic that Plotnicki’s merry band of sycophants might, in the long run, debase the art of dining more than his erstwhile rivals could ever dream of?

Yes, in the late aughts, those two organizations—Michelin and William Reed—wielded a particularly disproportionate amount of power in shaping public taste. American “foodies,” in those days before the birth of Instagram, had yet to arrive at the fore of mass culture. So aspirational diners, left to their own devices when it came to honing appreciation, outsourced their opinions to the Leviathan lists bestowed by their Europeans “betters.”

Perpetually debased as the land of factory farming and fast food, America could not help but lap up the crumbs of Continental praise that finally arrived. The French Laundry’s place atop the “World’s 50 Best Restaurants” list in 2003 and 2004 was certainly a seminal moment—something of a “Judgment of Paris” style coming of age for the national craft of cookery. Just a couple years later, 2006 counted the broadcast of Top Chef’sinaugural season alongside the publication of Michelin’s very first NYC guide. The United States, suddenly, had been judged worthy of entry into the rarefied world of international gastronomy. The pastime of a privileged segment of the population—fiercely guarded by an impenetrable, requisite etiquette—now shone a bit more brightly with the common knowledge that this or that restaurant was firmly “the best.”

“Foodies” lacked their contemporary haughtiness—their access to the hashtag hivemind—and naturally bowed before the rankings and ratings delivered from on high. Rampant consumerism fueled by a promotional media apparatus, as always, did little to breed discernment. A citizenry bereft of confidence when it came to place settings and tablecloths were perfect patsies. The novelty of white glove hospitality, of totemic luxury ingredients, the cult of the “celebrity chef,” and the ever-present thrill of conspicuous consumption worked wonders to obscure fussy fare that missed the mark for most Americans. But how many diners were brave enough to assert that “the best” wasn’t all it cracked up to be? How many would disparage the fruits of such a sizeable, aspirational outlay when it was all too easy to play pretend and reap the rewards of a contrived connoisseurship?

There was something paternalistic about the whole process: Americans were being led towards a definition of “luxury” shaped firmly from without. The country’s cultural hegemony was being challenged, its latent insecurity regarding expressions of “high art” stoked, by opaque organizations whose exact aims were unknown. The press, of course, would never resist perpetuating prestige ascribed to their local establishments. The stories wrote themselves—with fancy photos and fawning interviews to boot. What food writer would dare question the wisdom of letting Michelin take its perch a the top of American food culture? Who would think to ask the all important question: from where does William Reed derive the authority to publish such a “definitive” list?

In that era, it must have been easy to view Plotnicki as a homegrown hero ready to slay those European snobs who sought to make the American public dance to their tune. The fawning Forbes piece from which you quote certainly adopts that tone.

In it, OAD’s founder explains that he formed the organization in 2007 because he thought “the discussions people were having about food were not organized properly.” While such a statement makes you wonder why Plotnicki did not simply promote his original forum (titled Opinionated About), the former record company executive “sent out an e-mail survey to 175 voters, who in turn replied with their picks of their most recommended restaurants in North America and Europe.” He compiled the recommendations into a PDF that was freely available to the public—a touch of democratization that does, indeed, deserve praise. (But, in essence, does the reduction of many opinions into an ordered list not represent the antithesis of “discussion”?)

Sensing he was onto something, Plotnicki raised his game the year after. He redesigned OAD’s website and placed the results of its survey front and center (along with his “own restaurant reviews and dining commentary,” which have now wisely been removed from the equation). The former record executive also published “The 100 Best Restaurants of North American & Europe” in print—a double shot at Michelin’s guides and William Reed’s rankings in one tidy package.

Contemporaneous reviews of that volume provide some additional insight as to OAD’s perception at the time of its entry onto the scene. Grub Street titles Plotnicki “the so-called king of the bloggers” and earmarks his “distinctive…weighted system” wherein “the opinion of someone like himself, a deep-pocketed trencherman who eats out 300 nights a year, counts more than someone who comes into the city only occasionally or whose dining habits are limited entirely to his or her own neighborhood.”

Meanwhile, The New York Sun asks the all important question: “does New York really need another restaurant guide?” It goes on to aptly distinguish the nature of OAD’s audience: “unlike the mainstream guides geared as they are to those who merely enjoy eating out, Mr. Plotnicki’s 56-page pocket-size book is aimed at the small cohort of well-off foodies whose travel plans are driven not by museums, shopping, or sports, but by the restaurants at which they want to book a table. He calls his target audience ‘avid dining hobbyists.’ Their poster boy is Park Avenue-based Mr. Plotnicki himself, a former entertainment business mogul who heads off to Europe several times each year to seek out restaurants that matter and talk shop with their chefs.”

Moving back to the Forbes piece, Plotnicki singles out OAD’s “diversity of voices” as a particular strength: “It is more difficult for a guide derived from a single opinion to have the same impact as one that is based on a finely tuned algorithm that captures numerous opinions.”

“Algorithm,” there’s that word again.

Plotnicki’s “voter pool,” from which the OAD lists are developed, includes “restaurant industry heavyweights such as chefs, restaurateurs, food writers and bloggers” alongside a “majority” of “regular working professionals who are simply enthusiastic about dining out.” His “top reviewers” typically “eat between 100 to 150 meals in restaurant around the world per year, and mostly for their own pleasure rather than professional obligation.”

Voters are chosen in a manner that “corrected what…[Plotnicki] saw as the flaws in the other guides and lists.” They “sign up on their own” or the OAD founder finds them “via their blogs or Instagram feeds and…invite[s] them to participate.” Some longstanding participants have been drawn from Plotnicki’s former “Opinionated About” forum—a testament to the manner in which he was able to sublimate their previous discussions via the survey and list format. Still, others—even back in 2017—boast “Twitter and Instagram followers numbering in the tens of thousands.” Plotnicki believes that such user popularity (which, no doubt, must have grown exponentially in the past four years) allows his voters to “identify an up-and-coming restaurant or chef before other guides.”

Despite OAD’s professed prizing of “diversity,” votes are “weighted according to how experienced its voter is.” As Forbes describes, “each voter’s results are run through a proprietary algorithm that takes into account the quantity and quality of the restaurants they have visited, after which they are assigned a score. This score determines how much weight each participant’s votes have on the results. The distance a voter is willing [to] traverse for food is also a factor.”

As Grub Street mentioned above, the opinions of those who retain a narrow focus on their own neighborhood are deflated in favor of interlopers who provide a given community an outside perspective. Surely, this is a decision that orients OAD towards its professed audience of “avid dining hobbyists,” establishing something of an international standard that diverts attention towards a particular form of distinction.

Debbie Yong’s Forbes piece—which, you must admit, is laudably incisive in certain places—closes by touching on two of criticisms chiefly made about OAD that will serve as a convenient jumping off point for your own analysis. (Though, ironically, was it not something of a conflict that Yong—then as a digital editor, now as an editorial director—works for Michelin and was covering some ostensible form of competition? However, who else in media—in good or bad faith—can really be expected to probe beyond the usual puff pieces such rankings attract?)

First, OAD’s “detractors often deride…[Plotnicki’s] decision to publicise the names of the OAD’s core group of the 150 most prolific diners on his website, along with their number of votes cast.”

Second, “the harshest among Plotnicki’s critics have also questioned his impartiality for not dining anonymously and, in some cases, gratuitously — assertions to which Plotnicki has publicly responded…that his aim is simply to ‘search for the atypical meal that is generally available to the public, providing one knows how to ask for it.’”

There is plenty to like about OAD’s rankings, and you must admit that the organization’s lists truly are more nimble than those published by fine dining’s entrenched powers. You will even concede that Plotnicki’s proprietary formula has yielded greater accuracy than William Reed’s “Top 50” and points diners towards more distinctive experiences than Michelin’s static stars. If you’re being completely honest, you typically find yourself in agreeance with the American rankings and are thankful for the attention it calls to establishments overlooked by traditional media.

In just under 15 years’ time, Plotnicki has built a collective whose opinions can go toe-to-toe with—and even distinguish themselves from—the big boys. With 2019’s survey having been based on “over 175,000 reviews contributed by more than 5,700 people,” OAD’s rankings have become estimable data points in any discussion regarding global gastronomy.

However, as the organization’s legitimacy and reach have grown, OAD’s overarching influence on dining culture must be grappled with. What started as a highbrow guide for a distinguished sect of serial fine diners has now, in turn, begun to shape aspirational “foodie” culture. With its emblems now pinned on restaurant websites and Tock reservation pages—given pride of place alongside those other classic signifiers of supreme quality—Plotnicki’s project has clearly come of age. Thus, the deficiencies of its model—and the manner of culinary appreciation it implicitly stands for—must be judged with the same harshness as those titans of influence it originally sought to slay.

While OAD offers diners a valuable reference point within a crowded field of restaurant rankings and criticism, it carries within its proprietary process the very same power to obscure an individual engagement with the art of hospitality. The urge to standardize taste across international lines—while noble in its intention—ultimately works to erase the intricacies of regional foodways. Plotnicki’s standards may guide “foodies” towards a higher ideal than those of his rivals, but they amount merely to a different-colored filter tinging the same path towards a purely personal, transcendent experience of dining.

Such a manner of appreciation—the only one that may turn consumption towards a higher purpose—starts with an individual customer and a singular chef. It comprises a give and take of gustatory pleasure and service that grows to include the staff, the street, the neighborhood, the community, the city, and the region. Through such a process, the restaurant fulfills its highest calling: the expression of terroir. Such a precious characteristic resists the appraisal of any reductionist rating process—it speaks a language salient only to those who belong. The very nature of steering a jet-setting cognoscenti towards this or that place impedes the essential, local focus that promises—in time—to turn all hospitality towards the natural benefit of humankind.

Those are the stakes implicit in any attempt (intended or unwitting) to shape the tastes of an undiscerning public. And it is a duty abandoned by influencers of all stripes who crave the rewards of promotion more than the deeper fulfillment that can be drawn only from consumer education—a matching of each individual to some place whose magic speaks chiefly to them.

With the stage set, let us begin.

Of the criticisms levied at Plotnicki from the Forbes article listed above, you think OAD’s founder cannot really be faulted—at this point—for abandoning any pretense of anonymity. Likewise, while “eating for free” would seem to impede any accurate interpretation of a meal’s value, the man—it must be said—occupies a special role within the world of “food influencers.”

Given his past life—either as an “executive” or a “mogul,” depending on the degree of sycophancy one indulges—Plotnicki surely indulged in a more extravagant manner of dining from the get-go. One need not consciously carry the banner of an “influencer” to be greeted with special treatment. Rather, placing large or luxurious orders (at à la carte establishments), opting for extended tasting menus (when offered), or merely ordering fine bottles of wine are all sure to catch the attention of any discriminating service staff. Of course, those possessing extreme levels of connoisseurship are also easily detected by way of their gestures and fluency while at the table. Over time, the giddy wonder one feels when entering rarefied dining rooms subsides into a restrained (yet thoroughly comfortable) sort of appreciation—and that, to the trained eye, stands out.

OAD’s founder strikes you as the sort of man who wielded his resources in such a way as to elicit the very best a restaurant had to offer. Today, chefs who know of Plotnicki’s status could possibly engineer some special means of pleasing him. However, knowing that the “king of the bloggers” would pass his experience onto his followers, any contrived, individual offering would also be expected by the wider voter pool. Plotnicki ranks highly on his own leaderboard—meaning that his survey responses carry a disproportionate weight—but no place could afford to attract further evaluation without measuring up to the other diners of equal (or even higher) status. To do so would be to defeat the purpose of recognizing and feting OAD’s founder in the first place.

While it is easy to romanticize the kind of restaurant that provides an equal, unparalleled experience to each and every guest, part of the art of dining involves stoking the fire that ensures a given kitchen—when they see your ticket come across the pass—nails the “lot of little things done well” that define the finest food. Even the highest standards run the risk of lapsing, and Plotnicki—who has always been frank about the population of diners his list intends to address—surely expects his followers possess the financial or social largesse to demand chefs’ best efforts. An “atypically” excellent meal is rooted not only in the menu’s conception, but in a faultless level of execution, pacing, and showmanship that must sometimes be solicited.

Likewise, a kitchen’s highest expression of creativity must sometimes be induced. An à la carte establishment might put together a tasting menu upon request, one which features experimental or luxurious items that are otherwise unknown to the public. In the same manner, “regulars” at certain tasting menu restaurants are often provided with off-menu bonuses or previews of “coming attractions.” A newcomer, should they push in one way or another for special treatment, might also gain access to this kind of extended, expanded experience. It is often enough to ask ahead of time or assert the distance one has traveled to try a chef’s cuisine. Plotnicki, both before and after OAD, surely fit that bill, and that is why his list encompasses a higher stratum of meal that might demand “one knows how to ask for it.”

In a separate post on his former blog, Plotnicki rephrases his critical philosophy more clearly: to “elicit the best possible meal that a restaurant has to offer and in that context anonymity actually hurts instead of helps.” More than a decade ago, the OAD founder’s shirking of subterfuge drew criticism from Chicago food writers Julia Thiel and Michael Nagrant, who viewed his decision as one that necessarily skews the results of his surveys. Plotnicki found himself defended by the late Josh Ozersky—who, while beloved, became embroiled in his own ethical snafu not long after.

Plotnicki defended himself back then by asserting the only ethical hazard lies in a journalist receiving “an atypical meal that is not generally available to the public” and, by extension, praising a restaurant on behalf of an experience that lies out of reach. By playing within the boundaries of what any customer of adequate means and foresight can ostensibly purchase, the OAD founder feels that he sidesteps any notion of special treatment. He casts doubt on the idea that any chef would “run out [to] replace his $4 a pound veal with $5 a pound veal in order to get a better write up” should they notice a reviewer in the house. And Plotnicki decries Thiel and Nagrant as “blindly following a rule [anonymity in reviewing] that is antiquated and doesn’t make sense in a contemporary context.”

You appreciate Thiel and Nagrant’s valuing of anonymity in the context of food writing for a popular audience. While it is foolhardy to assume such a low profile can truly be maintained, the impetus of the effort lies in appraising some kind of “lowest common denominator” experience that the general public—lacking the largesse or social graces to solicit special attention—might receive. However, as revealed by Phil Vettel’s eventual unmasking, critics’ identities may stand as an open secret within the industry. If the restaurant knows the critic is in the house but the critic doesn’t know that they know, is the critic not easily manipulated into championing an exceptional experience they view as the norm?

Plotnicki is right to assert that chefs are not so cynical as to serve poorer quality fare to the unwashed masses, but ingredient quality isn’t quite the right example to consider. Rather, as mentioned above (as well as in the comments on his blog post), VIP-status in whatever form demands the kitchen pay just a bit more attention. It takes a well-oiled machine that might, on occasion, slip into “autopilot” and make a small error and ensures they put out their highest expression. Perhaps, in certain restaurants, a diner’s reputation earns them the extra flourishes of service that take a good evening and make it magical.

Such was the reasoning behind Pete Wells’s downgrading of Daniel from four to three stars in 2013, the critic writing that, though the restaurant cannot be faulted for providing special treatment to some guests, it “can be faulted, though, for turning its best face away from the unknowns, the first-timers, the birthday splurges, the tourists.”

Plotnicki’s philosophy is not well-suited to a food writer who seeks to lead the public. Nonetheless, you defend his decision not to dine anonymously because he views himself and his guide as shepherding the upper crust of “foodies” who are informed enough—and can afford—to demand the best of any given establishment. He is right to merely ensure that whatever he is given can be gotten by those who follow in his wake—for the nature of the survey naturally incentivizes rolling out the red carpet in repeat fashion. And, should something come gratis, the OAD founder is right to think that his audience is not quite inhibited by pricing when it comes to tasting quality.

The danger comes when, perhaps, OAD is increasingly looked to by an undiscerning public as an appropriate resource. While Michelin and William Reed keep a more generic guest in mind, disappointment might await for diners who are unable to distinguish themselves (or whose tastes, themselves, are undistinguished) in the same manner as Plotnicki’s voter pool. That being said, the responsibility lies on restaurants to make the most of a high OAD ranking by pleasing the full range of guests it attracts. Plotnicki, for what its worth, has always been clear about whom his survey speaks to.

No doubt, by spurning anonymity and acting as the face of his organization, Plotnicki can forge meaningful connections with the chefs he visits. That not only allows the founder to dig more deeply into the philosophical and stylistic underpinnings of each establishment, but to draw more professionals into OAD’s community.

The organization’s “grand collaborative dinner[s]” have become something of a big deal. They incentivize Plotnicki’s voter pool via nosh, networking, and rewards like a reservation at Noma. It is unclear what benefit the chefs involved might derive other than the development of an elite international clientele. But such promotional engagements are nothing new, and the grand dinners must play an important part in galvanizing the loosely-connected group of contributors that ultimately work to build OAD’s lists.

There is nothing flagrantly unethical about Plotnicki’s own efforts to transform the publication of OAD’s lists into an occasion. The former record exec is simply a one man band. While Michelin and William Reed possess the organizational structure to compartmentalize their inspectors/raters and promotional teams, OAD is more grassroots in nature. In fact, it’s really a guerilla operation wherein Plotnicki—the tip of the spear—directs and motivates his voter pool through serving as a living embodiment of the brand.

Dining anonymously, OAD’s founder is just another journalist judging a singular experience with the aim of extrapolating some paltry recommendation for the public at large. However, if Plotnicki makes himself known as an “uber diner,” he can push chefs to give it their all. The singular experience becomes something like the apotheosis of the restaurant. Plotnicki scales the heights of the kitchen’s creativity, gets to know the chef’s story, and cultivates the kind of relationship that clears a path for the subsequent judgments of the full voter pool. Surely, OAD’s founder is not always the first to make a discovery—rather, members of the community steer each other towards perceived greatness (knowing that any faulty recommendation maligns their individual reputation).

As a promoter, Plotnicki privileges the accuracy harvesting a greater number of survey responses would seem to entail. If the head honcho receives a particularly “atypical” meal, that would seem to skew his perception of quality. However, given that Plotnicki’s ultimate goal is to tout OAD as an organization, it can be expected that chefs roll out the same “red carpet” for subsequent members of the voter pool. For they will know the stakes and the style of experience this class of diners craves, and to have given Plotnicki a special experience yet snub his followers defeats the whole purpose.

At this point, you must concede that OAD successfully escapes criticism because it has retained its essential focus after all these years. Plotnicki’s survey stands as a resource for diners who are cut from the same globetrotting, gastronomic cloth. It subverts the institutional, mainstream approach of Michelin and William Reed by assuming its readers will plan their travel in a way that seeks out internationally distinctive dining experiences.

Occasional or aspirational fine diners, in contrast, likely find themselves traveling abroad for other reasons. Their dates and itinerary are set in accordance with personal or broadly touristic concerns, and then they endeavor to fit whatever great restaurants they can into the gaps. From such a perspective, any “foreign” establishment possessing at least one Michelin star will provide a memorable experience. It will provide the culinary cherry on top of what was, otherwise, a conventional bit of travel defined by sightseeing and special events (like weddings).

Certainly, doling out the dough for a Michelin-starred meal—which, often, comprises a tasting menu—will always remain an exceptional decision. However, the standards set by the tire company ultimately form the gateway into—and not the endpoint of—luxury dining. Bibendum and his henchmen privilege a level of consistency and comfort tailored to travelers of means who—nonetheless—defer to the Red Guides rather than sniff out the most exceptional of all dining options at a given moment.

Put another way, Michelin’s consumers will be pleased with great food plus the pomp and circumstance of classically-tailored, internationally-standardized luxury hospitality in a novel (to them) setting. OAD’s intended consumers would be happy to ditch some of fine dining’s more traditional tropes in exchange for greater creativity and character of a global caliber. Michelin is a guide for luxury consumers just getting their feet wet while OAD’s ranking lies waiting at the deep end of the pool. Consumers who reach the point where “three star” restaurants sometimes strike them as boring will find that Plotnicki’s surveys offer a breath of fresh air.

William Reed’s “World’s 50 Best” lists, while they would seem to compete more directly with OAD’s ranked style, are somewhat structurally flawed. By retiring “#1 restaurants” from contention once they have reached the summit, the organization effectively abandons any pretense of showcasing the absolute “best” establishments year in and year out. Instead, earning top billing becomes something of a lifetime achievement award for chosen chefs. It reflects William Reed’s acknowledgement that a certain concept has reached legendary status. They train a spotlight on that restaurant for a year, allowing it all the benefits that being “#1” entails, before letting it ride off into the sunset.

Surely, only a select range of chefs will ever occupy that absolute top spot (and, subsequently, be retired from the list)—so, perhaps, some level of constant competition remains. But the point of constructing a numerical ranking seems to be defeated if it is not all-encompassing. William Reed dilutes its winner’s status through the ever-present caveat that such a restaurant is only “the best” without regards to The French Laundry, The Fat Duck, El Celler de Can Roca, Osteria Francescana, and Eleven Madison Park. William Reed’s consideration of “Noma 2.0” as a separate contender from the restaurant’s original iteration demonstrates a certain self-awareness. But diners looking towards them to pinpoint the world’s greatest dining experience in a given year will find themselves playing a few cards short of a full deck.

Of course, there’s a more fundamental issue at play when formulating a global ranking. Should the “world’s best restaurant” be judged by self-selected, weighted, independent diners (in the manner of OAD) or be left to William Reed’s patriarchal, professional regional panel members? It is this decision that, more than anything, forms the distinguishing factor between all three restaurant rating organizations discussed in this article.

The “World’s 50 Best” list relies on 26 Academy Chairs who each cover a distinct geographical region. These figures—along with their Vice Chairs—are known to the public. Otherwise, the 38 members of the voting panel they appoint within their region must remain anonymous. This pool must strike a 50/50 gender balance and is comprised of “100% restaurant experts” of which a third are chefs/restaurateurs, a third are food writers, and a third are “well-travelled gourmets.” Additionally, at least 25% of each region’s voter pool must be new each year.

Each voter selects 10 restaurants—at least 4 of which must be from outside their home region “based on their personal best…experiences”—ranked in order of preference. They must have eaten in each of their selections within the last 18 months and must also confirm they hold no financial interest in any of the chosen establishments.

The United States and Canada are represented by three Academy Chairs: Jamila Robinson, a food editor for the Philadelphia Inquirer; Steve Dolinsky, specter of Chicago’s dining scene; and Virginia Miller, a former editor for Zagat and critic for the San Francisco Guardian.

In other words, three journalists orchestrate the entirety of America’s voting process for the “World’s 50 Best” list. Their personal biases and ethical lapses are altogether unprobed. The nature of their relationships with those whom they place on their panels is shrouded by an overarching anonymity. And any sense of fairness or integrity must be assumed in good faith. (But what member of the Fourth Estate—in this era of division—can we trust to resist flexing their influence in pursuit of what they personally perceive to be just? You cannot count one solitary figure in that industry who has earned widespread public trust without erring on this or that side of some contentious issue).

William Reed’s ranking hinges dubiously on those who make a living by shaping superficial narratives for public consumption. And, other than the nominal “independent adjudication” done by Deloitte, the “World’s 50 Best” is totally at the beck and call—at least within America (and Canada)—of figures who have every incentive to prize what’s novel or politically correct rather than assert the value of enduring technical quality. It seems all too easy for Academy Chairs to surround themselves with those who will toe the line in exchange for the “prestige” of their placement, who will lobby in a likeminded manner towards rewarding token establishments that fulfill prefabricated cultural storylines.

In this manner, the chairs’ authority might easily be wielded to indulge and reward those restaurants that tickle distinctly personal proclivities. At the very least, Robinson, Dolinsky, and Miller—based on a shared mass media experience—reflect a uniformity of vision that degrades any true sense of diversity in how one evaluates such a vast industry. William Reed errs in trusting those who, by the very nature of contemporary journalism, are essentially self-interested to run the show. These figures are naturally drawn more towards the fruits of public influence, the construction of a personal legacy, than any fidelity to art and shared cultural heritage. They are the last people to be trusted in placing the country’s best foot forward towards the rest of the world—for they only know how to deconstruct, not defend.

OAD, rather than bow before three chairs who contrive a pool of 117 other voting members, has broadened its approach far beyond that of the “World’s 50 Best.” Instead of channeling power towards a few golden children, Plotnicki relies on that “finely tuned algorithm” to align his data with regard to the intended audience.

The survey, of course, starts with self-selection. Voters sign up via OAD’s site or are invited by Plotnicki himself. Whatever the route, contributors decide they want to play a part in constructing the organization’s lists and must follow through of their own accord.

“World’s 50” Academy Chairs are selected by William Reed on the basis of some professional prestige. While a candidate’s worth as a restaurateur or chef would be hard to argue with, choosing among foreign journalists surely presents the powers that be with a more subjective choice. “Prominence,” in that space, aligns more closely with pernicious staying power and designs to excel in an increasingly clickbait-driven genre. Journalists advance through the ranks—while earning a pittance—by pleasing their masters. Their reward comes via access and influence—the self-importance felt when molding public taste in your image.

So there’s a bit of self-selection at play there too: just what sort of person is empowered to succeed in a given media environment? What narratives do they routinely sell? Who sort of businesses do they typically promote? Is there a balance to their coverage, or do they view it as their duty to change culture in accordance with some unspoken aim?

Beyond any surface-level “prestige” shoved down the public’s throat—intra-industry awards are a favorite bit of artifice—food journalists’ motives escape scrutiny. Their biases are obscured by an impenetrable process of inclusion and omission. “Newsworthiness” is determined tautologically; meanwhile, trust is ascribed to a defunct editorial tone that ultimately serves to shield the writer from putting all their cards on the table.

Robinson, Dolinsky, and Miller reflect the viewpoints of a narrow, nearly monolithic profession. To trust them with appointing voters who, in turn, guide consumers on an international level is farcical. Imagine how those unlucky Canadian chefs—swept up in this domestic madness—feel! William Reed’s “World’s 50 Best” list, no matter how superficially rigorous they make the judging process sound, is a media construction meant to guide global coverage in accordance with unstated goals.

Undiscerning diners see those magic words—“the best”—and afford the list an unearned prestige. It’s the sort of dark magic of manipulating human nature that has formed the bread and butter of the journalistic profession since time immemorial. William Reed’s list reflects only the opinions of a small sect of professionals whose credentials as diners—appreciators of art, appraisers of lasting quality—have escaped questioning. “World’s 50” is contrived by a media group, with the help of journalists, for the sake of constructing narratives that benefit promotional and political aims.

But that does not mean OAD is perfect.

Plotnicki, by allowing broad participation, largely controls for the biases inherent in the Academy Chair model. Likewise, by indulging in a points-based system that rewards prolific diners, he privileges those voters who have cultivated greater dining experience. The last bit of weighting—which counts the scores of those who have traveled farther to a restaurant more than relative locals—functions something like William Reed’s condition that voters must select at least 4 restaurants from outside their respective region.

For lists that purport to rank the world’s best, the prizing of international opinions makes total sense. Top restaurants consciously view themselves as global destinations, and the mark of superlative hospitality, surely, is to make as wide a variety of people comfortable in your care as possible. “World’s 50” seeks to generate international press coverage while OAD looks to guide a population of “uber diners” that transcends borders.

By letting the “uber diners” themselves have their say, Plotnicki achieves far more accuracy than William Reed. The former keeps its finger on the pulse of the most delicious, most forward-thinking restaurants of the moment. The latter, in contrast, reflects the proclivities of a murky food professional class who are not even guaranteed to have visit their chosen establishments in the past year. OAD uses guerilla criticism to sharpen the definition of “international quality” to a razor’s edge. William Reed decides only when a certain (usually longstanding) restaurant is well-suited to a wide-ranging media blitz.

In that manner, OAD stands more distinctly at the bleeding edge of gastronomic culture while William Reed does little to distinguish itself from Michelin’s own efforts to influence would-be fine diners who lack discernment. While Bibendum’s star ratings speak to the inspectors’ enduring standards, “World’s 50” rankings might as well be drawn out of a hat. William Reed’s voting system is neither broad nor deep enough to be insightful. It’s an insular (though, nominally, rotating) hivemind driven by branding concerns. It’s a method of duping members of the aspirational public inexperienced enough to outsource their taste and vain enough charge headfirst towards a conspicuous “number one” for the prestige visiting might bring.

OAD, to Plotnicki’s credit, hits closer to the mark in defining some rigorous, widely-felt standard of quality. But the list format, in its essence, remains reductive. It sidesteps the founder’s original aim of “organizing discussion” by establishing a hivemind of a different order.

While going out to dinner more frequently does not necessarily mean a voter develops greater insight, it stands to reason that the best perceivers of the art of dining do, indeed, spend more time than most at the table. OAD indulges in the necessary evil of stratifying its survey responses in accordance with the best measure of connoisseurship one could contrive (short of something unimaginable like standardized gustatory testing).

It is surely better to discriminate between voters in a flawed way—total number of restaurant visits—rather than to avoid accounting for experience at all. The privileging of travel, too, works to ensure that gluttons do more than merely pump their numbers up within their own neighborhood. For it is one thing to routinely enjoy fine meals on one’s home turf, but another to uproot in search of excellence. Such a concept strikes right at the heart of the Michelin Guide’s own founding motivation: defining worthy destinations to sell more tires.

OAD’s well-founded means of filtering the most intrepid diners out from those creatures of habit begins to fall apart upon considering Plotnicki’s publication of the survey’s “core group of the 150 most prolific diners on his website, along with their number of votes cast.” Yes, of all the criticisms that have been made, that regarding the construction of a consumptive leaderboard remains enduring and—in your opinion—of great consequence for global dining culture.

By ranking its top contributors, OAD introduces a sense of prestige—perhaps even fame—into the equation. Though any given voter could identify themselves to a restaurant as a survey-taker, perhaps leveraging a social media profile to outline just how influential their scoring might be, formally ranking participants adds a competitive-consumptive incentive to the process.

Conducted in a wholly blind fashion, the survey would ensure that its voters are guided purely by the thrill of dining and widening their own insight to the best of their abilities. They would understand that increased participation awarded them greater influence; however, the fruits of their work would be obscured by the overall survey results. Thus, independence and careful appreciation would be preserved against any perceived need to keep pace with OAD’s heaviest of hitters.

In contrast, placement on a prestigious leaderboard takes what should be solemn, careful work and provides voters with an incentive linked to their personal branding. While typical conspicuous consumptive “foodies” must debase themselves by consciously touting their “experience,” OAD provides an all too valuable external sanction. They need not game social media algorithms, create viral content, or engage in the impossibly hard task of educating the public to acquire a reputation as someone of taste. They need not even trawl the depths of journalism with the hopes that one day they can con themselves into the title of “critic.”

Rather, those in OAD’s top 150 spots have successfully traded money for influence. The necessity of offering the public any shred of insight—of weaving together the cultural and historical threads that make dining an art—is sidestepped altogether. Resources are simply devoted towards collecting experiences, shallow social media posts are perpetually made, Plotnicki’s survey is provided a veneer of “authority,” and the OAD leaderboard ensures the influencers’ bread is buttered. It all amounts to a feedback loop in which the conscious desire for self-exposure trumps the cultivation (let alone the sharing) of expertise. It strikes you as yet another manifestation of fine dining’s longstanding role as a shallow means of class distinction.

Self-selection might work fine when it attracts those who are merely passionate (or, shall we say, opinionated) enough to devote time towards rating restaurants. Anonymity would work to ensure the best intentions from those in the voter pool who venture above and beyond into the extreme range of several hundred meals per year. But ascribing status to the most prolific consumers changes the game altogether. It transforms the list into a vehicle for vain individuals who are happy to notch tasting menu after tasting menu on their belts with nothing more to show for them than a couple trite compliments.

Michelin’s inspectors are quite clear about the grueling nature of their work—which, at bare minimum, involves writing a detailed report about each visit to every establishment. While Bibendum’s star ratings are certainly glamorous, the grunts who do the groundwork consciously spurn any attention—to say nothing of a perverse critical “fame.” Even the newspaper or magazine critic—though rarely a figure of much authority—benefits little by touting their status to the public at large. They must, as best as they can, retain a focus on their readership. And any infamy they develop—the only quality that could possibly lend those writers some measure of real reputation—carries with it the consequence of greater scrutiny from those being judged.

OAD’s leaderboard, at the end of the day, expresses the same tendency as the mukbang trend or any other form of “eating influencer.” It is telling that China, of all places, has stepped in to ban such gluttonous content while the West celebrates it.

Plotnicki’s methodology reduces dining to a purely consumptive—rather than personal, emotional, and transcendent—act. In an effort to construct an international standard of taste, OAD has, instead, encouraged a race to the bottom of shallow engagement.

For those at the top of Plotnicki’s leaderboard naturally attract more followers. Their content influences the rest of the voter pool—and restaurants themselves—without any need to offer valuable feedback. Travelers orient themselves towards the experiences touted by OAD’s “upper crust,” and their subsequent survey responses also benefit from an added weight. Meanwhile, locals who might disagree—who stand for a definition of quality more intimately connected to regional tastes—find their scores deflated.

Jet-setters guiding jet-setters is fine—but for the fact that OAD’s self-selected, incentivized “power users” turn around and define their native scene for the sake of an international audience. They embrace the prestige of global tastemaking, align themselves towards a standardized ideal, and then devalue—if not erase—expressions of distinction that retain an eminently local character. The critic who always keeps their eye trained on what other “elite foodies” from other countries privilege will always, inevitably, overlook latent quality in their own community. Perhaps they even look down upon that which would fail to appeal to their far-flung friends.

OAD ultimately channels its talent towards the development of a rootless gastronomic standard. It lures “foodies” of means out from their communities and transforms them into agents who champion some outside definition of taste. Plotnicki’s voter pool is, indeed, grassroots. But, rather than forge a bottom-up standard of quality that reflects local character, it encourages a bowing before the proclivities of a privileged population.

Those who travel constantly in search of food speak a certain language, and their global perspective is well suited to a minority that skims the cream off the top of any community they find themselves in. Plotnicki’s genius, however, comes from turning a range of regional influencers towards the propagation of OAD’s proprietary standards. By promising them validation (and, thus, fame) a generation of “foodies” will be brought into the fold of a group that feels the most valuable work to be done lies in appraising what lies far away. They will be taught that chasing one-off experiences in exotic locales—following in the footsteps of some unreachable figure—holds more value than wielding their expertise to cultivate wider appreciation and higher standards in their own neighborhood.

Plotnicki, for all his interest in provoking discussion, seems content to encourage fawning posts and numerical rankings as the be-all and end-all of connoisseurship. The world of gastronomy does not grow richer by boiling the myriad factors that distinguish a given individual’s appreciation into a survey response. What American food culture needs, in this moment of unparalleled engagement across class lines, is articulate, distinctive voices that defend intensely personal definitions of quality.

Gastronomy must take a cue from oenology—the latter being, without question, the superior intellectual domain. Budding American wine drinkers did not come of age by deferring to tastes gleaned from afar. Instead, Robert Parker appealed to their palates and their wallets by acting expressly as a consumer advocate. Surely, Parkerization had its problems—but appraising gastronomy demands far less expert knowledge, and a multiplicity of distinct perspectives is much more easily attained.

The heyday of print media once allowed cities to possess a range of prominent voices each standing for a particular vision of gustatory quality. Snobbery, the limitations of print, a lack of insight drawn from the journalistic ranks, and a bowing before the same “content creation” model now mastered by “foodie” influencers has all but eradicated this vanguard of taste. The next generation of local critics must stake out new territory between broadly-appealing tripe and the sort of shallow indulgence designed only for a rarefied audience. Dining only affirms its status as “art” when consumption is turned towards a deeper appreciation of life. It only transcends its longstanding role as an expression of class insecurity when interpreted in such a way as to bring new beholders into the fold.

OAD’s recently published North America “Top Restaurants” ranking exposed to just what degree Plotnicki hides behind the supposed statistical rigor of his survey to silence dissent.

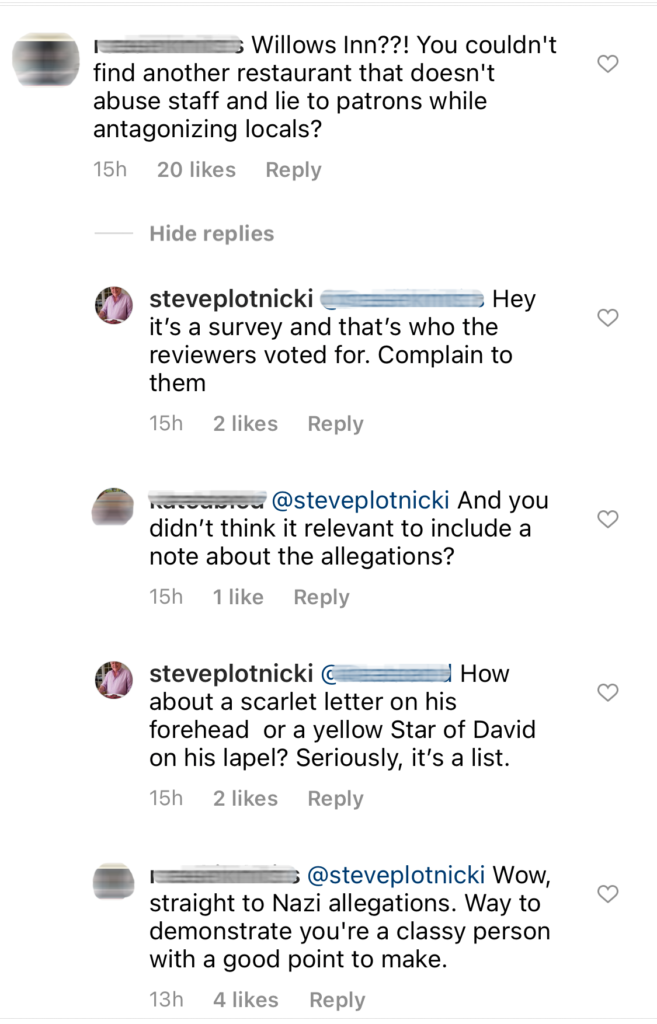

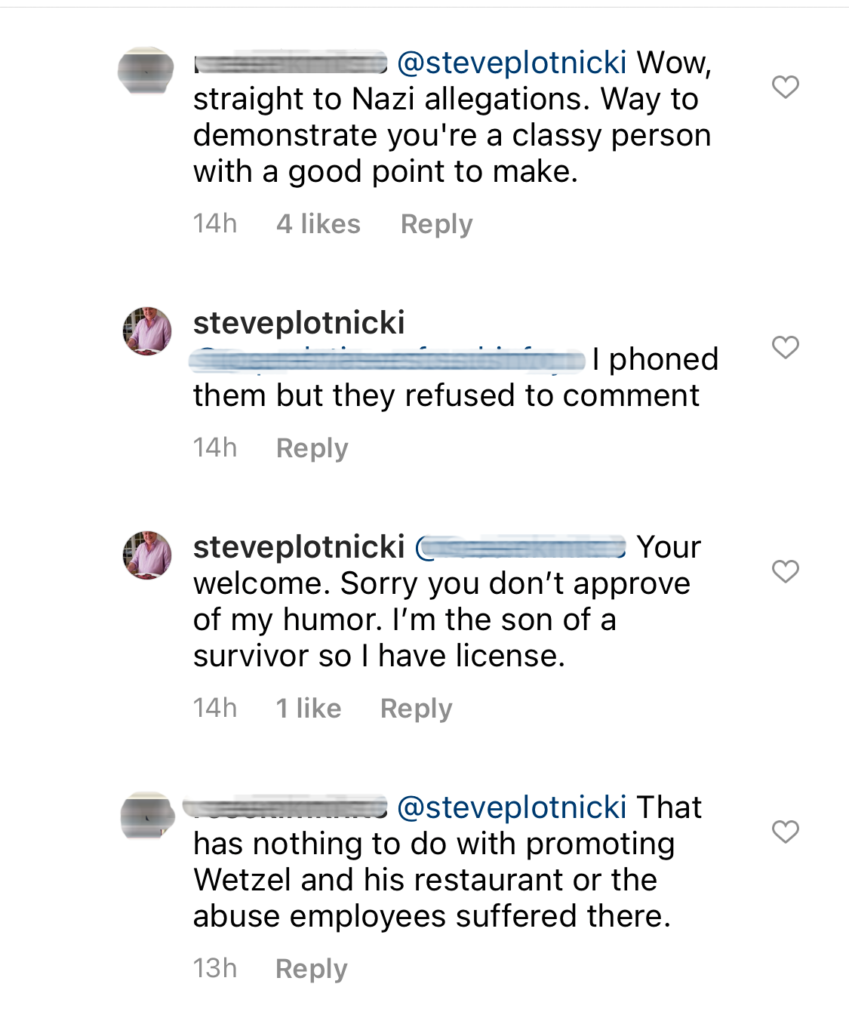

Blaine Wetzel’s Willows Inn claimed 2021’s top spot despite New York Times reporting this year alleging “racism, sexual harassment, and deception” at the restaurant. The social media mob quickly trained its sights on Plotnicki, deploring the fact that his list made no reference to the controversy in awarding the establishment with its hallowed top spot.

The OAD founder contended that such context was unnecessary: “Hey it’s a survey and that’s who the reviewers voted for. Complain to them.” He also added, sarcastically, “I phoned them [the reviewers] but they refused to comment.”

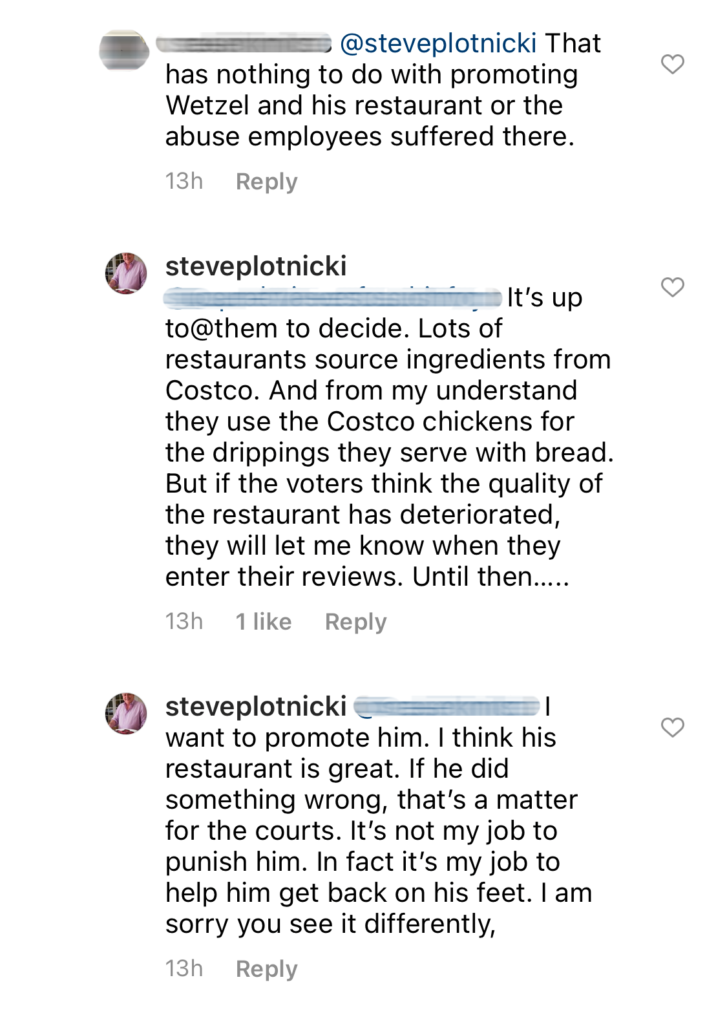

Plotnicki’s more detailed defense of obscuring Willows Inn’s negative press coverage deferred principally to his survey process: “if the voters think the quality of the restaurant has deteriorated, they will let me know when they enter their reviews. Until then….. I want to promote him. I think his restaurant is great. If he did something wrong, that’s a matter for the courts. It’s not my job to punish him. In fact it’s my job to help him get back on his feet.”

The OAD founder’s defense of his decision, you must admit, aligns with your own critical philosophy: let the art speak for itself and allow the justice system to distinguish bad behavior from that which is criminal and disqualifying. You would even argue that, should a chef actually commit a crime and pay their debt to society in good faith, it would be wrong to deny them a fair evaluation. Yes, the public and any potential staff should know whom they are working with—but is appending some additional asterisk onto a ranking driven solely by quality not discriminatory?

That hypothetical situation reminds you, in some sense, of how Stone Flower was treated by Chicago’s critics upon the revelation that the ex-42 Grams chef assaulted his wife. Is there a distinction to be made between a journalist’s efforts to keep their public abreast of a chef’s character—to help a community decide just whom is worth supporting—and that of a critic to judge food purely on its own merit? It seems, to you, to be a distinction most “critics” blur in a desperate bid to wrap themselves in some fleeting shred of relevance by bowing before “social justice.”

The history of gastronomy is built upon countless practices that, viewed anachronistically, become abuses. Yet for any critic or rater to inject their subjective moral standard into the process—beyond the limits defined by the law—is to sever the thread that connects contemporary culinary art to its past glory.

Mean chefs and marauding brigades, like it or not, have long crafted the world’s finest food. Appraising art should not count the degree to which a craftsperson embodies or transcends the accepted practices of his or her times. A compassionate leader should naturally reap the rewards of their good conduct. Likewise, a tyrant will either spell their own downfall (by proving unable to retain talent) or, possibly, attain some similarly high level of quality by pursuing a thornier route. Only the finished product—comestible and hospitable—determines the ultimate value of the art.

Of course, some amount of malfeasance may never reach the threshold of violating a particular law. And the press should play a part in providing a voice to victims who lack the means to unload their trauma in a manner that engages the wider community and demands answers.

Those diners who read the coverage and are struck by the stories told will, surely, take their business elsewhere. But public shaming carries its limits: the news cycle chugs along, and allegations that amount to no tangible legal action are eventually forgotten. The social media mob may work to ensure Willows Inn and its patrons are reminded of the pain the restaurant is alleged to have caused. But, whether Wetzel admitted to impropriety or not, just what is OAD to do other than continue to judge the quality of his food?

Plotnicki only cares about shaping an international standard for fine dining. His survey only reflects the feelings of his voter pool. And—if they care little about what goes on behind the scenes at Willows Inn, if they are shown an experience that consistently ranks as the best in the country—who has the stomach to rain on Wetzel’s parade? Traveling gastronomes hold no feelings for anonymous kitchen staff or Lummi Island locals. They care little about a given community and its stories save for those being expressed on the plate. OAD’s list ranks the quality of the “sausage” alone—not the process by which it is made.

How could they ever discern which restaurant is truly “the best” if they allow personal ethical and moral judgments to impede an evenhanded tabulation other than at the level of each individual voter? Plotnicki respects his followers enough to let them decide for themselves, and he is right to view the fruits of his formula as a natural expression of their acceptance or rejection of the controversy.

But such a viewpoint—while well suited to pure artistic evaluation—only underlines your larger point about OAD: the organization cultivates a kind of “foodie elite” that cares little for the finer details—good, bad, and ugly—that define a given restaurant within its community. How can they ever sense them when playing a game that, by its very nature, disincentivizes rootedness?

Plotnicki prizes a glamorous gastronomic lifestyle forever removed from the intricacies of daily life. His followers engage in an endless game of competitive consumption in pursuit of an illusory, international ideal.

OAD’s “foodie elite” form an effective guidepost towards pleasure—yet it is a fleeting, performative pleasure that denies any tastemaker’s essential role as a nurturer of their local scene, a champion of their distinct regional culture. The temptation to rank as one of the world’s top diners will always defeat the solemn, thankless duty of trawling a city’s dark corners in search of latent talent. America needs more Jonathan Golds and fewer Steve Plotnickis.

It is infinitely more valuable to convince a wider swath of a city’s native population to give its finest restaurants a try than to pimp them out to a rarefied, globetrotting crowd. For the goal is to foster, in each and every place, a deeper appreciation and more careful consideration of cuisine’s power to connect and sustain humanity.

OAD may have accomplished its goal of toppling William Reed and Michelin when it comes to accuracy. It will continue to stand, alongside more insular regional rankings, as a definitive resource for the pure appreciation of culinary arts.

But, in its attempt to standardize taste, Plotnicki has subsumed a generation of “foodies” who might have shone more brightly as advocates of distinct local taste. They would have had to in order to earn credentials that now—thanks to OAD’s leaderboard—are ascribed for the mere act of consumption alone.

OAD brings American dining culture ever further away from honest discussion and a higher diversity of taste that only reveals itself when diners can orient themselves with regards to a wide variety of intelligent opinions. The only “objectivity” that can really exists in appraising fine dining comes about by balancing one’s biases and sensory thresholds via an honest, uninhibited engagement with each restaurant as a singular work of art.

By propagating the reduction of wondrous experiences into cheap numeric ratings—and encouraging shallow content creation and networking by its voters—OAD leads dining culture towards a new dark age.

The snobs that once wielded dress codes and table manners to distinguish themselves from the riffraff have been reborn clutching smartphones and caterwauling about an exclusionary sense of “authenticity.” The OAD voter—in this age bereft of belonging—chooses “fine diner” as an identity. They cultivate and equip themselves with an all-knowing taste to distinguish themselves from all the shameful slobs that make up that detestable place they call “home.”

When their time and attention could be utilized to guide the unwashed masses, step by step, towards a finer appreciation of food, the OAD voter connives amongst their fellow “foodie elite.” The choose a global peerage drawn together only by a desperate need to consume: bigger, better, more exclusive—whatever the cost to continually assert they are different, special, better.

America will only fulfill fine dining’s democratization—the coming of age for her sense of gastronomic pride—when its “foodie” luminaries see the value in guiding its most backwards palates from fast food to fresh food and from fresh food to local, seasonal food that expresses a sense of place. Surely, such a process has something to do with access to resources but more to do with culture. It has nothing to do with the shame conspicuous consumption stokes by celebrating “how the other half eats.”

Conscientious consumption that affirms the connectedness between diner, craftsman, community, and nature holds the power to convince even the most retrograde palate. The tongue does not lie—even if it has been led astray all its life by artificial crap chemically engineered to please. The emotional dimension to dining does not discriminate; it ensures that any human gathered around the right table at the right time may transcend mere corporeal enjoyment. They may find themselves enlivened—sustained—by that eternal art of hospitality that distinguishes all humankind despite countless barriers.

OAD’s “foodie elite” work towards the creation of a global gastronomic culture that is more blatantly stratified and disconnected from the common diner than ever before. In doing so, they deny a meal’s highest power for the sake of personal gain.

“I saw the best minds of my generation destroyed by madness, starving hysterical naked, /

dragging themselves through the streets at dawn looking for an angry fix, /

Angel-headed hipsters burning for the ancient heavenly connection”