Galit marked one of Chicago’s most consequential restaurant openings of 2019. The local media worked hard to ensure that: cheerleading the concept as it came to fruition and eagerly christening it a “Middle Eastern masterpiece” just a couple months after doors opened.

Can you blame them? The Windy City rarely attracts national culinary talent, and Zach Engel seemed destined to redefine his chosen genre. Galit’s chef/owner had won the James Beard Foundation Award for “Rising Star Chef of the Year” in 2017 while working at Shaya, “a modern Israeli restaurant in New Orleans.” Before that, he had already helped the concept claim JBF’s “Best New Restaurant” title in 2016. And Engel could also count experience cooking at Michelin-starred Madrona Manor (near Healdsburg), Catit (Meir Adoni’s “flagship” in Tel Aviv), and Zahav (Michael Solomonov’s 2019 JBF “Outstanding Restaurant” winner in Philadelphia) since entering kitchens straight out of college in 2010.

(Reflecting on his time at Madrona Manor, something of an unknown quantity for you, Engel would say that working “under Jesse Mallgren” was “fundamental” to the way he cooks and creates dishes. He wanted to work for the chef because they “used to pick ingredients” in the restaurant’s garden “to cook for service each day.” Engel, thus, was able to get his “hands in some dirt” and start “to understand growing seasons” and become “a better judge of seasonality,” bringing Mallgren’s “level of focus and balance” to his own subsequent dishes.)

To be fair, Engel spent some time alongside Alon Shaya at Domenica (an Italian restaurant in New Orleans), Federal Donuts (another Philly spot—now a chain—from Solomonov), and Gautreau’s (offering “modern French and contemporary Louisiana fare”) too. But the narrative of the chef’s career seemed tailormade. He spent time at what are generally regarded as the country’s finest modern Israeli concepts—winning, at Shaya, two of the industry’s most coveted awards—and was ready to set up shop on his own. With this kind of pedigree, Engel could seemingly choose any city in which to ply his trade, and whatever he opened would undoubtedly have that air of a “destination restaurant” about it.

Ultimately, the chef chose Chicago. He and his wife Meredith “fell in love with the city and Midwestern values everyone seems to embody” and became “enamored with the farmers markets, the architecture, and the sense of pride in the city itself.” Engel would note his future home’s “rich dining scene” drawn from its “immigrant and blue-collar roots” and claim that “nowhere else in America does there seem to be a more exciting place to cook.” Chicago also brought the chef back together with his former Tulane classmate Andrés Clavero, who had spent five years at Deloitte before becoming One Off Hospitality’s senior account (while also working the floor at Nico Osteria). The two had actually met in 2015 when “Clavero dined at Shaya while visiting New Orleans to attend a Saints game. Engel introduced himself, and the two began to see all the connections they shared.” They first worked together a year later, when “One Off Hospitality catered the James Beard Awards and hosted Shaya’s takeover event.”

With Clavero as his partner and general manager, Engel would look to Lincoln Park to open a restaurant named after his daughter Margalit’s nickname (with “Galit” also representing the Hebrew word for “wave”). The cuisine would be “similar” to the chef’s work at Shaya but also draw on his “diverse culinary experiences.” It would “strive to embody” who Engel and Clavero are “outside the kitchens” they worked in: referencing “the dishes served on our family tables…and the flavors that feel like home.” For the chef, that signified his “time growing up in a Jewish household as the son of a rabbi and his many trips to Israel.” Back then, his father was “too busy to cook” and his mother “too uninterested,” but the family “would eat really great food” when traveling. For the general manager, the concept would draw on his “Palestinian, Cuban and Spanish background” and memories of his parents “being the ultimate hosts.”

Engel had a building at 2329 N. Lincoln Ave. picked out—“a pizza parlor across the street from Lincoln Hall and around the corner from the legendary alley where bank robber John Dillinger met his demise”—from the moment he first announced he’d be leaving Shaya in September of 2018. Galit aimed at opening “in early 2019,” and the restaurant would secure the services of Kinship, a Chicago-based “complete marketing agency for leaders in culture, food and travel” (whose notable clients include Andros Taverna, Bazaar Meat, Rose Mary, Sepia, and Smyth), to help promote its concept.

The chef’s reputation preceded him, and partnering with his Palestinian friend spoke—rather endearingly—to a vision of hospitality that transcends thorny, often dehumanizing political disputes. Galit, thus, had the perfect story to tell the public: a narrative about the coming together of cultures and the culmination of a meteoric career. But the restaurant, as it took shape, could boast some unique foundational elements too. One “focal point” would be “the kitchen’s 8-foot charcoal hearth” (designed by Pilsen’s Wayward Machine Co.) that would “literally” form “the center of the restaurant.” It would come “equipped with custom metalwork that Engel designed, including a kebab box and shelves to hang meats and dry herbs.” “My first night at Zahav, I cooked everything over charcoal, and I thought, ‘at my first restaurant, I’m going to cook over charcoal,’” shared the chef. The kitchen would also boast an “Engel-designed smoke box, inspired by Carolina pit barbecue” that the chef could “mess around” with and “figure how to take this cuisine and drive it in a different direction.”

With regard to ingredients, the chef proudly shared that he had “a farm growing hyssop for us…so we can make our own za’atar—a true za’atar, not like the markets that substitute dried oregano.” With regard to the menu, Engel admitted “it’s pretty obvious” he’d be “doing hummus and pita,” along with “great falafel,” in order to “give people what they inherently want.” However, the chef would also develop his “own style” that would free itself from “how Alon would want it executed” back at Shaya and enable “more experimental stuff.” That would include “dishes with a charcoal element” like “wood-roasted Brussels sprouts with orange blossom” and “shakshuka eggs…with coal-roasted sweet potatoes” alongside “less-common bread dishes” like “laffa, a pitalike flatbread” and “malawach, a Yemenite pancake” that would be paired with a foie gras torchon.

(Just for reference, it may worth delving a bit deeper into Engel’s work at Shaya as sous chef and, later, chef de cuisine from December of 2014 to October of 2017. Conceptually, the New Orleans restaurant framed “the foods of modern-day Israel” as “a living mosaic of many origins: from Turkey to Morocco, Bulgaria to Greece, and Yemen to Russia” while supporting “local farmers in Louisiana and Mississippi” and “honoring the fresh seafood from…[the] Gulf of Mexico.”

One illustrative menu from September of 2016 lists a selection of “Small Plates” like “Kibbeh Nayah,” “Wood Roasted Cabbage,” “Foie Gras,” “Lamb Kebab,” “Falafel,” “Persian Rice,” “Avocado Toast,” and “Crispy Halloumi.” There are five expressions of “Hummus” titled “Curried Fried Cauliflower,” “Soft Cooked Egg,” “Chanterelle,” “Tahini,” and “Lamb Ragù.” The “For the Table” section—available as a flight of 3 for $15 or 5 for $23—comprises “Baba Ganoush,” “Israeli Salad,” “Labneh,” “Tabouleh,” “Lutenitsa,” “Shipka Peppers,” “Pickles,” “Ikra,” “Moroccan Carrots,” and “Wood Roasted Okra.” Finally, the “Large Plates” included “Shakshouka,” “Amberjack,” “Roasted Chicken,” “Wagyu Hanger Steak,” and “Slow Cooked Lamb.”)

Galit would ultimately open on April 3rd of 2019 (the chef having originally aimed for February), still a rather impressive seven-month turnaround from the concept’s original announcement. It counted 110 seats and a bar, a neighborhood restaurant “that’s a little nice for the neighborhood” in Engel’s own words. The chef notes that the investment was “about $300 per square foot” for a total of “a little over $1 million” (described as “at the low end of what major Chicago restaurant groups…are spending to operate their places”). He and Clavero “did not want to be saddled with heavy obligations;” rather, they “want[ed] to make money, pay it back, own the business, make more profit, and do more concepts.”

Relative to restaurants “in prime areas” that “need to charge $100 to $150 per diner in order to be profitable,” Engel was aiming for an average check of $65: “pretty low for Chicago dining, but it’s also hummus.” The menu would promise “recipes from the republic of Georgia, as well as offerings with roots in Turkey, North Africa and Yemen” and comprise “about 75 percent vegetables”—“a challenging sell in a city that loves meat.”

At the same time, the chef revealed he had overseen Galit’s wine program himself, revealing that his “big thing, passion wise, with restaurants is wine.” Engel touted that “diners will find bottles that aren’t widely available elsewhere” while also, later, admitting that “he encountered some challenges with distributors in bringing the Middle East wines he liked to Chicago.” The list would feature “bio-dynamical [sic] varietals [sic] from Sonoma, the Middle East, and ‘everywhere else’” and not contain “a lot of French or Italian wines.” The chef set the goal of “trying to banish the mystery that has often accompanied choosing a bottle of wine,” calling out “the wine industry” for not “making people feel comfortable” and looking “to eliminate the disconnect between a wine professional and the person looking at the menu.” Ultimately, Engel was “most excited to see how people react to the wine list” because he’s “pretty confident about the food.” Put another way, Galit was “either going to be a restaurant that serves fantastic Middle Eastern food, or a restaurant with fantastic Middle Eastern food and the most exciting wine list (diners) have seen in a while.”

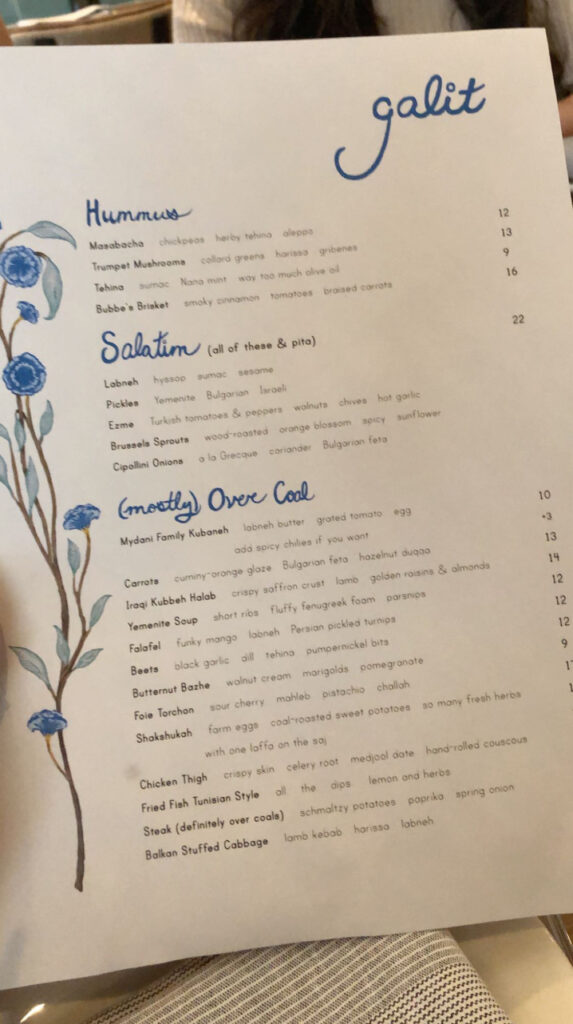

You first visited Galit a little less than a week after opening and dined at the concept another half dozen times throughout its first year of operation. The original menu featured four different versions of hummus: “Masabacha” ($12), “Trumpet Mushrooms” ($13), “Tehina” ($9), and “Bubbe’s Brisket” ($16). For $22, you could get a set of five “Salatim” (“Labneh,” “Pickles,” “Ezme,” “Brussels Sprouts,” and “Cipollini Onions”) served with pita. The final category, “(mostly) Over Coal,” features dishes like the “Mydani Family Kubaneh” ($10), “Iraqi Kubbeh Halab” ($12), “Falafel” ($11), “Foie Torchon” ($17), “Shakshukah” ($16), “Chicken Thigh” ($18), “Fried Fish Tunisian Style” ($22), “Steak (definitely over coals)” ($25), and “Balkan Stuffed Cabbage” ($23).

Over the course of the year, the “Salatim” selection would be augmented by items like “Wood-Roasted Turnips,” “Wood-Roasted Summer Beans,” and “Pumpkin Tershi.” Likewise, the “(Mostly) Over Coal” category would welcome additions like “Halloumi” ($14), “Wood-Roasted Broccoli” ($12), “Smoked Lake Trout” ($13), “Heirloom Tomato” ($12), “Kale Tabouli” ($12), “Wood-Roasted Asparagus” ($12), and “Lamb Chop” ($32). But many of the restaurant’s opening preparations would prove to be mainstays (particularly the various hummuses and the larger plates of shakshuka, chicken, fish, steak, and stuffed cabbage).

(Galit, it is also worth noting, offered “The Other Menu,” a family-style offering featuring one hummus, all the “Salatim,” your choice of three “Mezze,” three shared entrées, tea/coffee, and dessert for $65 per person exclusive of tax or gratuity.)

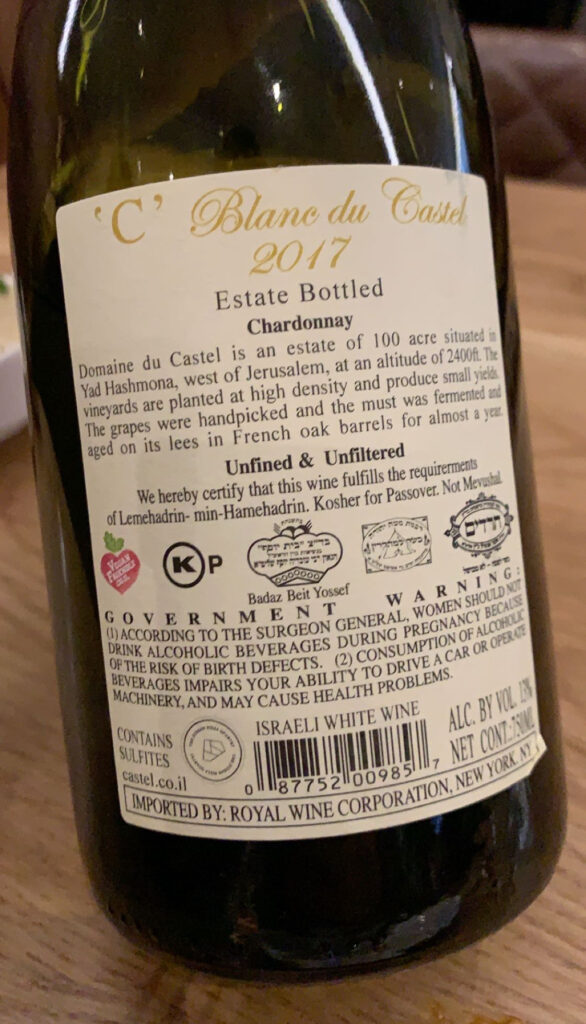

The restaurant’s wine selection, back in those early days, featured by-the-glass options from Spain, the Loire, Armenia, Slovenia, Chile, Austria, Bulgaria, Lebanon, Greece, Piedmont, Sonoma, Arizona, Paso Robles, and Israel—each annotated in the playful (if sometimes non-sequitur style) you recently engaged with in a separate article. The bottle list (a little under half of its selection being drawn from the Middle East) featured producers like Alain Graillot, Chateau Musar, Cruse Wine Company, Domaine du Castel, Evening Land, Failla, Matanzas Creek, Patricia Green Cellars, Ridge, Roger Pouillon, Schramsberg, Smockshop Band, Sylvain Pataille, and Von Hovel spanning regions like Argentina, Australia, Georgia, Germany, Oregon, Morocco, Palestine, the Rhône, and South Africa too.

Overall, during the course of that first year, you found the Galit experience to be polished if a bit “underwhelming” (to draw on the precise term you utilized in a piece of correspondence from October of 2019). The restaurant’s space was nicely designed and buzzed with eager diners. The open kitchen—defined by the hearth and the oven—bustled with activity. The staff was warm and welcoming. And menu items like the various hummuses, the assorted salatim, and the fresh-baked pita (generously replenished as necessary) impressed you.

But the wine list, despite offering a wide range of bottles from a diverse array of regions, felt middling. The “Middle East,” “(mainly) Sonoma,” and “Pretty Much Everywhere Else” categories used to organize the selection seemed unique on the surface but ultimately worked to distract from a dearth of producers who offer top quality and value. (For your taste, you would only count Cruse Wine Company, Evening Land, Ridge, and Sylvain Pataille as satisfying those criteria.) This feels a bit unfair to the “Middle East” wines, which suffer somewhat from obscurity and whose representation—insofar as they reveal the breadth of world vinous culture and reflect the same terroir that has inspired Engel’s cuisine—is valuable. Yet many of these selections are made from robust varieties like Barbera, Cabernet Franc, Cabernet Sauvignon, Carignan, Cinsault, Grenache, Merlot, Mourvèdre, Petit Verdot, and Syrah that mainly suit those who like more powerful expressions of red.

More principally, these full-bodied wines were juxtaposed by relatively small portion sizes throughout the “(mostly) Over Coal” section. This was not unforgivable when you consider that the menu’s most expensive item—“Steak (definitely over coals)”—still cost only $27. Engel and Clavero clearly had a low check average in mind when opening their restaurant, and maintaining more modest serving sizes (or at least erring on that side) surely suits that goal. Eventually, you learned how to adequately bolster your meal with multiple orders of the same dishes (mainly with regard to protein), but that did not quite lead to the kind of joyous, flowing shared meal you sought. Beyond the hummus, salatim, and pita, the dishes seemed a bit fussy and self-contained: cohesive when approached by an individual diner but less rewarding when forked from the other side of a loaded table. Further, your appreciation of the smoky, spicy, herbaceous, and tangy flavors that distinguished much of the food would fade with repeat exposure. Eventually, they could no longer overcome a more general sense of sparseness. Or was it self-doubt? The wine and cuisine were intelligently conceived but just fell short of being fully satisfying and, thus, memorable. Were you missing something?

This all amounted to a concept that you felt was strong within its particular genre. It was beautifully packaged with a lot of novelty appeal. However, Galit’s wine list was not the sort that had you rushing back to pick off more bottles (finding an adequate one was hard enough), and its cuisine was not exactly craveable to the degree that you would place it in your upper echelon of local establishments. Still, the restaurant was a worthy addition to Chicago’s dining scene and possessed the kind of foundation (in terms of space, service, branding, and the quality of the hummus/salatim starters) that offered plenty of room for growth.

As is usually the case, your opinion was in the minority relative to the city’s critical luminaries. Michael Nagrant was first, rebutting Yelpers who were complaining about Galit’s price and portion sizing and arguing that Galit “is charging the right number for a level of food that is almost peerless.” Phil Vettel followed with that “Middle Eastern masterpiece” line and three stars (“excellent”) from the Tribune. Then came Maggie Hennessy, awarding the restaurant four out of five stars from Time Out while criticizing a small service miscue and praising “sublime eating.” Next up was the disgraced Ariel Cheung, who—before she was caught leveraging her editorial power at the Tribune to secure free food—praised Engel as “the kind of chef who…will make sure each dish is the best version you’ve ever tried” in CS. Jeff Ruby, writing for Chicago, awarded the restaurant two stars (“very good”) and said the city “is lucky to have Galit to welcome us in.” Mike Sula, in the Chicago Reader, termed Galit a “singular outpost for one of the world’s most exciting—and developing—cuisines” that, here, is “finally done right.”

In November, Galit would clock in at rank #15 on Phil Vettel’s list of the city’s “50 best restaurants,” with the former critic highlighting “heavenly pita,” a “joy-of-discovery wine list,” and “pun-filled cocktail menu.” Eater Chicago would name Engel’s concept a finalist for “Restaurant of the Year” (it would lose to Virtue) as well as one of the best openings and one of the five most beautiful spaces of 2019. The Jean Banchet Awards, likewise, would nominate Galit for its “Best New Restaurant” prize (yet it would ultimately lose out to Kyōten). Nonetheless, the concept fared better on Chicago’s “Best New Restaurants” list. Galit would claim the fifth spot behind Jeong, Kikkō, Wherewithall, and Tzuco but ahead of spots like Moody Tongue, CLAUDIA and Mako.

Despite this widespread local acclaim, Galit did not quite attract the attention of national food publications. Food & Wine had named it one of spring’s “most anticipated” openings, and Saveur (via chef Isaac Toups) recommended the restaurant as one of 14 spots in its May 2019 “How to Eat Your Way Through Chicago Like a Chef” article. Yet Galit was absent from Bon Appétit’s “Best New Restaurants 2019” list (Bungalow by Middlebrow, Jeong, and Kumiko/Kikkō represented Chicago among the 50 nominees). And the same held true for the list of the James Beard Foundation’s 2020 Restaurant and Chef Award semifinalists (though Engel’s pedigree might have, in part, precluded that).

Of course, you firmly believe that Chicago should define its dining culture without any reference to what outsiders think. Galit’s dining room was perpetually packed (perhaps stymying roving journalists’ efforts to snag a table), and the local tastemakers liked it. Maybe, when you consider the popularity of Shaya and Zahav in their respective (comparably minor) food cities, the Windy City was just beginning to catch up in expressing this particular cuisine?

Putting the lack of national attention (and your own misgivings) aside, Galit’s first year of operation was a general success. Chicagoans turned out to taste Engel’s food and liked it enough to keep the dining room full and reservations scarce. The chef, pushing onward into 2020, was well poised to expand on his work and, perhaps, start thinking about the other concepts he might eventually wish to bring to the city. However, just short of the restaurant’s first anniversary, everything changed.

The pandemic’s first wave would spur the closure of indoor dining on March 15th, and Galit would pivot just two days later. The restaurant began offering both lunch and dinner to go via curbside pickup (with specials like “Matzo Ball Soup,” a “Cubano,” a “Lamb Burger,” a “Steak Sandwich,” “Saffron Rice,” “Shawarma Spiced Fries,” “Baklava,” and “Challah Bread Pudding” on offer). Concurrently, Engel raised money for his team via GoFundMe (offering branded hats and t-shirts in exchange for certain minimum donations) and offered free meals to other workers in the industry too.

The establishment, meanwhile, kept an upbeat tone on social media. It used the lull in normal operation to look behind the scenes at the concept’s development: things like the materials that make up the dining room, the creation of the “whimsical” logo, and the photo of a storefront in Jaffo that (now hanging in the back dining room) inspired the restaurant’s design. It also showcased some of the kitchen’s ingredient sourcing (like lamb from Catalpa Grove Farm) and the chef’s favorite bottles of wine. However, after the death of George Floyd, Galit was quick to show its support for “values like equality, accountability, community, empowerment and respect” through fundraisers for My Block, My Hood, My City; Surge Institute; Marwen; Movement for Black Lives; and Brave Space Alliance.

In July of 2020, as part of Feast on Lincoln, Engel would launch Galit on the Street, an outdoor brunch and dinner experience “inspired by the street food of the Middle East.” The menus would combine some of the restaurant’s old standbys (like hummuses, salatim, and falafel) with new creations like the “Big Boy Boreka,” “Fried Bulgarian Pepper,” “Wood Roasted Corn,” “Sabich Sandwich,” “Lamb Kebab Plate,” “Chicken Shishlik Pita Sammy,” and “Striped Bass (definitely over coals).” In September of 2020, the Galit on the Street experience would make way for a “full service” menu that, for $55 per person, offered guests the choice of one “Hummus” for the table, a serving of all the “Salatim,” individually chosen dishes from the “Mezze” and “(mostly) Over Coal” sections, and one “Dessert” for the table. This would preface the restaurant’s return to indoor dining—drawing on the same prix-fixe format—on October 6th.

That would prove to be short-lived as Chicago halted indoor dining once more on October 30th. Galit transitioned back to outdoor service for a couple weeks then, as the pandemic hit another peak in mid-November, returned to only offering takeout and delivery. The restaurant would weather the winter with special Hanukkah dishes like “Latkes” and “Sufganiyot” (Israeli donuts filled with pear butter and strawberry Aleppo jam). Through the holiday season, items like “Chocolate and Tahini Babka,” a “Corned Beef Pita Sammy,” and a pastrami set for two (with supplemental foie gras, caviar, and challah rolls) also appeared.

At the start of 2021, Engel launched the Galit “Shuk” (a Hebrew word that roughly translates to “market”), through which the restaurant could sell goods like harissa, za’atar, tahini, beer, wine, and other “house made goods” to customers via pickup and delivery. The chef also got in on meal kits (particularly a “Shakshuka” and a touching rendition of “Kibbeh bil Sanieh”) as a way to engage those stuck at home further. In March of 2021, Engel partnered with Jonathon Sawyer for a three-day collaboration menu in support of the Chicago chapter of Asian Americans Advancing Justice. Then, in April, Galit would raise funds for the organization once more (with its borekas) as part of Beverly Kim’s Dough Something campaign.

After once more spending the second anniversary of its opening with indoor dining closed, the restaurant could finally announce the reopening of its dining room on May 14th, 2021. (Steve Dolinksky, the eternal pimple on the face of Chicago dining, would proudly declare “Galit Re-Opens Dining Room, Still Serving Chicago’s Best Modern Food From the Levant.”) In doing so, Engel would be sticking with the “choose your own adventure” four-course menu he had first debuted in late 2020. At $65, the prix-fixe would match the price of “The Other Menu” that had been offered as a family-style experience back when Galit originally opened.

The rest of 2021 would (thankfully) pass quietly enough, and the start of 2022 would see the concept undergo some minor construction, repairs, and maintenance as it embraced, at long last, some kind of normalcy. Most consequentially, Galit “built a real wine cellar” (in Engel’s own words). The chef, in the same post, described that he’s “always been proud of” the program given the energy spent “meeting with reps,” explaining his vision for the list, “tasting,” and “learning.” Beyond the “obvious” focus on the Middle East, he was “proud to be supporting” winemakers engaging in low-intervention, sustainable farming and winemaking practices who create bottles “that just simply drink well with our food.” Thus, though Galit did not originally budget the money to give the program “a space in the restaurant to really breathe or grow,” the new cellar could finally “match the pride” the chef felt for his selection. In Engel’s words, “the restaurant feels a little more whole…a little more grown up” now.

With these improvements and the new prix-fixe menu under its belt, Galit sailed into 2022 and toward its third birthday. For the first time, the restaurant would be able to celebrate the occasion with its dining room open. No doubt, the anniversary felt particularly sweet after the past couple years. However, on April 5th (three years and two days to the date it all started), Engel, Clavero, and their team would have even greater cause to celebrate. Galit was named—alongside CLAUDIA, Esmé, and Kasama—as one of Chicago’s new Michelin-starred restaurants.

Bibendum would term the place a “rustic-chic hot spot” with a “lively vibe, warm hospitality and seductive aromas.” “Sharing is key to cover the most ground,” said the bulbous mascot, in enjoying Engel’s “personal brand of modern Middle Eastern cuisine.” That includes “familiar dishes” with “surprising depth, like creamy hummus or crackling-crisp falafel with mango labneh.” Michelin even declared that the restaurant’s dessert “manages to be just as tantalizing as the savory fare,” particularly an “updated spin on baklava” they termed “a wonderfully elegant finale.”

Engel, at the time of the announcement, was “interviewing a candidate for an open cook position” and felt “pretty astounded actually” by the award. He added, perhaps somewhat cheekily, “I never thought hummus would win a Michelin star, you know?” The chef “credited changes” like “a turn toward larger plates, experimenting with more unique ingredients and launching a tasting menu” as factors that “likely appealed to Michelin inspectors.” Put another way, he characterized these decisions as “wanting to shake off the cobwebs and trying things that were more fun to cook and challenging.” He “just wanted to give the cooks something to look forward to and to work on that wasn’t putting falafel in a compostable (to-go) box.”

In a separate interview with Engel and Clavero’s alma mater, the duo said the star was “well deserved for the team who’s been around and dealt with the last three years of ups and downs,” and “it just shows that if you work very, very hard, and you try to make food that’s delicious and consistently so as much as possible, and you are creative enough, things like the Michelin Guide will come knocking on your door.” Looking back over the year in November of 2022, they called the award’s impact on the restaurant “immediate.” Though the dining room was already full on the weekends, “Galit is now booked solid every night, which represents a 20% to 25% increase in reservations during the week.” The waiting list, on some nights, can even “grow to four times the restaurant’s capacity.” They’ve even “had to hire additional people” to keep up with the demand of increasing event bookings. Nonetheless, Engel and Clavero had “no plans to expand or open another restaurant” at the time, remaining committed to “continuing Galit at the same high level of quality and enjoying the restaurant’s success as it becomes more of a household name in Chicago.”

To that end, the restaurant would end the year with yet another distinction of national (or maybe even international) import. In December, William Reed featured Galit as part of its “50 Best Discovery” list—drawn from establishments that “receive a significant number of votes in the most recent round of polling for The World’s 50 Best Restaurants” or feature on one of their “annual regional rankings” but fall short of the “elite establishments” that compose the top flight ranking. The concept was lauded for its “cosy-cool dining room” and “mid-century styling” that “evokes warmth from the get-go” and even makes it seem as though “you could easily be in Tel Aviv, Beirut, or perhaps Istanbul.” With regard to food, the “origins of the region’s cuisine are lifted with clever twists along the way.” In particular, the “pillowy puffed pitta” and “iconic smoked turkey shawarma” received special attention—along with “Zach Engel’s warm hospitality.”

Galit would end the year with one last burst of promotion from the Tribune, making sure Chicagoans knew that “Galit nabbed a Michelin star ‘for hummus, falafel and pita’ — and it’s just getting started.” The piece formed the sixth entry in an eight-part series on local Jewish restaurants “honoring tradition while forging new paths.” It offered some tasty tidbits regarding the concept’s cookery: like that “the hummus is prepared over multiple days” (the chef tasting “every batch”), “the falafel involves dozens of steps,” and “the foie gras blintz had countless predecessors.” Engel noted that while people call Galit’s cuisine “Israeli food,” he’s “not Israeli,” his business partner is “part Palestinian,” and the restaurant embodies “an approach to Middle Eastern cuisine from a personal perspective, utilizing as much of the bounty the Midwest has to offer.” The wine program, with “its mix of Lebanese, Palestinian and Israeli grapes,” was termed “one of Chicago’s most unique.” But, most strikingly, the chef revealed he no longer worried about the “external validation” of awards after winning his Michelin star—and despite people saying “all the time” that his restaurant is “not as good as everyone else makes it out to be.” His concern now, rather, is to “settle in for good” and run a restaurant that is “iconic” in Chicago. “What are you in this for if you’re not trying to do that?”

This seems like the perfect place to make your entrance—or is it a return? You had generally enjoyed dining at Galit during its first year of operation, finding some aspects of the experience “underwhelming” but conceding that Engel and Clavero had built a fine foundation to expand upon. 2020 and 2021 would offer their share of tribulations, but 2022 was, by all accounts, a banner year. The restaurant has entered 2023 with wind in its sails and the kind of trophy cabinet that reflects its maturity as a concept. Thus, after nearly three years away, the time seems ripe for you to engage with Galit again and see if the establishment has fulfilled all its early potential. Bibendum and the promotional powers that be have had their say, but just what does it take to be “iconic”?

You have dined at Galit three times throughout January and February of 2023. As is usual, you will condense the sum of these experiences into one cohesive narrative. However, unless otherwise specified, you will avoid referencing the multitude of meals you enjoyed at the restaurant during 2019 and 2020. These earlier visits may provide you with some valuable context with which to perceive the concept’s growth, but, likewise, they reflect a style of dining at a particular price point that no longer exists in the same form. You are more concerned with where Galit is today—and where it hopes to go—than where it has been. So, for the sake of effectively guiding consumers at this moment in time, you will limit your narrative to the experience at hand with more overarching comments, vis-à-vis the restaurant’s development, being reserved for the final analysis.

With that said, let us begin.

The 2400 block of North Lincoln Avenue hardly seems home to a Michelin-starred destination. Engel took over a former pizza parlor (Pizano’s) after all, and the street on which Galit sits still seems more defined by DePaul (a block south) and Lincoln Hall (just across the street) than any “rustic-chic hot spot” offering “high quality cooking, worth a stop!” Yes, this particular stretch suits the needs of students and late-night revelers just fine, with shops slinging bagels, bubble tea, burgers, coffee, cookies, donuts, fried chicken, green juice, gyros, hot dogs, ice cream, Italian beef, pizza (even with Pizano’s demise), sushi, and tacos to all and sundry.

Yet, following Lincoln Avenue just one block southeast leads you to Lincoln Common: “over 100,000 square feet of vibrant dining, retail and fitness experiences, elegant condominiums…boutique office space, and a central plaza offering year-round events for all to enjoy.” The development, which first welcomed residents in April of 2019, sits on the site of the former Children’s Memorial Hospital that was demolished in 2016. “Unhappy neighbors” fought the project for years but lost. They can now enjoy a host of businesses offering services like addiction treatment, fitness classes, laser hair removal, therapeutic massages, and veterinary care at their very doorstep. Lincoln Common can even tout the third national location of Verve Wine: the bottle shop (from Master Sommelier Dustin Wilson) that has greatly expanded Chicagoans’ access to cult regions and producers.

Galit opened concurrently with the arrival of Lincoln Common’s first residents, and it is fair to say that the restaurant forms a liminal place that stands somewhere between these old and new expressions of the neighborhood. Hummus, pita, and falafel—humble foods that, nonetheless, take a lifetime to master—do not seem that out of place among the beef, pizza, and taco joints. They are all accessible, beloved, and positively eternal forms that appeal widely across demographics. And it is not hard to imagine, at least back in the day when Engel offered an à la carte menu, that a student (okay, maybe a graduate student) might post up at the bar for a few bites.

Just the same (and the chef’s humility aside), Galit is hardly so nondescript or one-note. The building, clad in clean, bright white stone, stands in stark contrast to its neighbors. The red brick of the Victory Gardens Biograph Theater (where Dillinger caught a flick before catching a hail of gunfire in the alley adjacent to the restaurant), for example, seems positively drabby by comparison (though you appreciate how Galit’s dark door and window fixtures match those of the movie house). Lincoln Hall, originally opened as a nickelodeon in 1912, looks a bit more stately across the street. Galit’s stonework roughly matches that of the music venue, yet the latter’s faded color betrays its age. Will Engel’s restaurant, one day in the distant future, be distinguished by its matching patina?

For now, however, the restaurant stands apart. The structure looks sleek and its signage is pleasantly understated when compared to Takito Street, Wake-N-Bakery, and the theatre’s marquee located on either side. There’s a closed Pita Pit, ironically enough, that can be found across the street too—not to mention the massive apartment building going up on what was once a small park space (located between Lincoln and Halsted) that you used to enjoy sitting in before your reservations.

Another touch, positioned at the corner of the building closest to the alley, renders Galit’s address in the Israeli style, with the street name written in Hebrew, Arabic, then Latin script followed by a separate plaque for the number. These bright blue panels, set against the white stone, are absolutely striking. Yet they are also small enough to escape attention, to make you feel—when they finally catch your eye—like an “Easter egg” waiting to be discovered. Ultimately, this signage winks at the notion of “authenticity” by actualizing it through the kind of small, quotidian detail that actually reads as a faithful representation of “place.” It coyly speaks to a kind of sophistication and underline’s the concept’s worldly, multicultural quality.

This fresh yet considered façade and subtle layering of meaning allows Galit to gel with its surroundings while simultaneously satisfying the refined tastes of the Lincoln Common crowd and those from further afield. Of course, the restaurant’s current $84 (per person) entry price might now prove particularly insurmountable for those who once thought that $9 hummus and $12 falafel were too expensive. But, aesthetically, Galit fits the bill for those now paying $2,000 – $7,500 a month to live down the street. It’s nice without seeming gaudy and delectably diverse without veering off into anything too strange. The well-heeled can eat there often without feeling overly indulgent or bored while the neighborhood’s ordinary denizens might still conceivably make it through the door for a (somewhat more) special occasion.

For you, visiting Galit means trekking to a part of the city that you hardly find appetizing. Armitage Alehouse, Esmé, and North Pond bring you there from time to time—as did Verve, though the wine shop has had to pause its “Provisions” dining concept. Yet the area’s establishments largely suit the everyday eating patterns of its locals. And Lincoln Park, in an era without Charlie Trotter’s or L2O (and with a totally Flanderized, zombified Alinea), simply lacks its former gastronomic supremacy. The neighborhood has been usurped, both in total Michelin stars and overall glitz, by West Loop. To some, no doubt, that is blessing.

Engel deserves credit for bringing Chicagoans from other areas, as well as tourists of all stripes, back into the fold. Pulling up to 2429 N Lincoln Avenue ahead of your reservation, Galit’s popularity is immediately apparent. In the minutes before the restaurant is set to open, a steady stream of patrons tries the door, sees that it’s unlocked, and gleefully scurries inside to secure spots at the bar or a walk-in table. By a bit after 5, the space bustles like nowhere else on the block (save for when Lincoln Hall hosts a show), yet the warmth of the hearth and the assembled guests remain coolly contained behind the front-facing windows (that also, jutting out a bit past the door, form the wall for a set of banquettes).

Stepping through the entrance, you find yourself in the tiniest of vestibules (that, nonetheless, shields diners from any cutting winter drafts). Passing through one additional door, you come face to face with the host stand: smartly situated in front of two structural beams that have been outfitted with a wooden screen between them. This reception area is rather small too—the restaurant having just about maximized its seating—but warmly operated. Two or three members of the team, almost always including a manager, stand ready to greet you and whisk each party away to its table in record time. However, even in that brief moment you stand by the entrance, it is hard not to admire the workings of the kitchen.

Depending on where your table is located this particular evening, this interlude may present the best opportunity to watch Engel and his cooks work. For Galit’s dining room is astutely segmented to offer guests a range of ambient experiences throughout the meal. The first of these, you have already mentioned, comprises two zones located closest to the windows on either side of the front doors. Each features a wraparound banquette (accented by bright blue upholstery and brown leather cushions) that is lined with two-tops, four-tops, and a trapezoidal five-top placed right in the corner. There is also, on each side, a freestanding four-top placed near the middle of the floor. The furniture here is rendered in sturdy, comfortable wood with plenty of room between the various parties. Small ceramic planters are set into both of the corners as a wicker lampshade hangs overhead. While the western wall displays some exposed brick, the eastern one benefits from an additional bank of windows looking out on the Dillinger alley. Both areas, nonetheless, benefit from the natural light and activity drawn from the street. They allow you to appreciate the restaurant’s energy while remaining a bit secluded from all of the action.

Moving past the host stand, you immediately find yourself in the heart of the operation. To your left, wrapping around the full length of the kitchen, is an L-shaped counter that Galit—to its credit—books separately from the rest of the tables. These seats can accommodate a maximum party size of three and tend to be the last to book up. They also are used (rather ingeniously now that Engel has his Michelin star) to host single diners, who are treated to an excellent view of the chef’s James Beard Award that hangs on one wall. The chairs here are a bit smaller but still comfortable enough. Depending on one’s height, they allow you to peer over the turquoise subway tile that forms the kitchen’s outer barrier and watch the cooks work. This is not a “chef’s counter” per se, but Engel can almost always be seen watching over the grill or his custom-made smoke box when not putting the finishing touches on particular plates. Likewise, watching the rest of the team maneuver around the two central ranges while also making fresh pita in the wood-fired oven is highly enjoyable. The counter benefits from an additional raised platform that holds what is essentially a sneeze guard but also serves as an additional surface on which to stage your dishes and drinks. Thus, while this seating area may initially seem a bit cramped, you have found the eating experience—mechanically—to be quite similar to being seated at a table.

Opposite the kitchen counter, in the very center of the restaurant, you find a single row of alternating two-top and four-top tables that stretches toward a back room. Galit’s six-seat bar is located right on the other side of them, meaning that this section is effectively sandwiched between two high-traffic areas. Still, the spacing between and around the tables remains wide enough to avoid any feelings of claustrophobia. Sitting here feels like being at the restaurant’s nucleus, totally awash in the concept’s brimming patronage. For more boisterous parties, this may prove perfect; however, you personally prefer the relative tranquility of the dining room’s other areas.

Moving over to the bar, you find a sleek assortment of perpetually packed—though generously spaced—stools from which patrons perch over an expansive surface. The white, black, and wood tones that define this counter and its corresponding shelving meld well with the rest of the space. You can comfortably enjoy a meal here, as many do, without having to contend with an avalanche of imbibers. But the best part, undoubtedly, is found just beyond the bartop in the restaurant’s northeast corner. There, a twelve-seat high-top table glistens under a trio of wicker lampshades and glows in the reflection of a worn mirror. This zone, which can accommodate larger walk-in parties or a mix of smaller groups, is also one of the dining room’s most intimate. It allows you to peek at the bar (and, depending on your exact seat, the kitchen) while enjoying your experience in relative seclusion.

Finally, adjacent to this high-top (on the other side of the wall) and toward the end of the central bank of seating, you find Galit’s private dining room. Closed off, as necessary, by a pair of striking barn doors accented with frosted blue, black, and white glass, this area offers the restaurant’s most subdued experience. It comprises a banquette along the back wall—over which hangs the photo of the storefront in Jaffo that inspired Galit’s aesthetic—that houses a couple two-tops and four-tops. Meanwhile, a free-standing four-top and a five-top make up the rest of the floor. Sitting in this zone means sacrificing any view of the action, but the more moderate noise level and overall isolation may appeal to some parties. Overall, while you have your own seating preference, Galit’s degree of flexibility across the various spaces and the overall cohesiveness of its interior design is impressive. Engel and Clavero have built a restaurant that is streamlined and highly practical without sacrificing any bit of comfort or style.

Taking your seat, the server stops by to offer their greeting and ask your preference of water. Anticipating their return, you direct your attention to the beverage menu (located on the opposite side of the prix-fixe) and the bottle list (a separate document that has already been laid on the table).

To start, Galit offers a half dozen cocktails of which five are priced at $15 and one is priced at $18. This selection seems a bit abbreviated when compared to the ten listed at Andros Taverna or the thirteen sold at Aba (just to name two restaurants within a broader “contemporary Mediterranean” category), but Engel’s preference for wine has been clearly stated since the concept’s genesis. Plus, the pricing seems fair when compared to the former ($15-$17) and latter ($14-$28) properties.

Galit’s drinks, crafted by bar director Scott Stroemer, presently include the “Flowering Fox” (vodka, hibiscus, mezcal, sumac honey, rose), the “Goin’ Goin’ Gan” (mezcal, cilantro, cumin, [spicy] zhoug bitters), the “Saz Arak” (rye, medjool date, bitters, arak), the “Za’atar Martini” (Lebanese gin, quinquina, hyssop, olive), the “Clarified Milk Punch” (apple brandy, cachaça, genmaicha chai, lemon), and the “Zafaran View” (cognac, saffron, amaro, cardamom). These creations span a representative range of spirits (with mezcal and cachaça serving to snare tequila and rum drinkers respectively) while also referencing some of the myriad Middle Eastern cultures that influence the restaurant’s cuisine. This is accomplished through ingredients like sumac, cumin, zhoug (a Yemeni hot sauce), arak (a Levantine anise spirit), za’atar, Lebanese gin, hyssop, saffron, and cardamom. While this list seems relatively spice-forward (a pleasant counterpoint to cold weather), cocktails like the “Flowering Fox” and “Clarified Milk Punch” show the kind of restraint that can still achieve a feeling of refreshment. Despite not typically ordering martinis, you enjoyed the depth of flavor of Galit’s za’atar, quinine, and hyssop rendition. Nonetheless, the “Clarified Milk Punch” tasted a bit too boozy and not nearly as creamy as the kind you can get at Kumiko or The Loyalist.

In the spirit-free category, you find two “Gazoz” (described as “fizzy, fruity, herby sodas”) each priced at $9. These were originally introduced as part of the the Galit on the Street menu in 2020 and served to replace the restaurant’s earlier assortment of non-alcoholic cocktails. This was a clever choice, for gazoz first found popularity in Israel in the “early 20th century” and have, thanks to Benny Briga of Tel Aviv’s Café Levinsky, recently undergone a resurgence using “fresh flavors made from local and seasonal ingredients.” Previous soda offerings included “Apricot” (orange blossom + verjus + cilantro) and “Strawberry” (rhubarb + cardamon + dill) but now comprise “Pomegranate” (hibiscus, cardamom, rose) and “Apricot” (shrub, urfa, anise). Of these, you have sampled the “Pomegranate,” which you found to be tasty if a touch diluted. Nonetheless, the serving size really impressed you, and the restaurant deserves credit for wholeheartedly embracing an existing cultural tradition rather than centering the spirit-free program on aggressively marketed products like Seedlip or Lyre’s.

Galit’s wine by the glass selection is made up of 12 different options split, three a piece, into four categories: “Bubbles,” “White,” “Rosé / Orange,” and “Red.” Prices range from $12-$18 with an average price of $14.67. This compares favorably to Andros Taverna (with a range of $13-$19 and average of $15.50) as well as Aba (with a range of $11-$25 and average of $15.70) while being only a bit more expensive than Avec West Loop (with a range of $11-$17 and an average of $13.36). The chosen bottles—affixed, in most cases, with the chef’s own annotations—also represent the most public-facing expression of Engel’s vision for pairing wine with his cuisine.

In the “Bubbles” section, that comprises Keush’s “Origins” ($16), an Armenian sparkling wine; Mersel’s 2020 “Leb Nat” rosé ($18), a Lebanese petillant naturel whose “organic grapes replaced old hashish fields”; and Proxies’s “Bulle” ($12), a non-alcoholic sparkler made in Ontario. The decision to forego Champagne is, of course, bold. But it demonstrates the chef’s commitment to having his guests try something entirely new (even in such a popular category) and smartly sidesteps the premium consumers have to pay for sparkling from the famous French AOC. The “White” section, at present, is made up of Meinklang’s 2021 Grüner Veltliner ($15), which asks “have you ever had Grüner and hummus?”; Laberinto’s 2021 “Cenizas” ($16), a Chilean Sauvignon Blanc termed “pretty much a Sancerre, but cooler”; and Camp’s 2021 Chardonnay from Sonoma County ($13), described as “movie theater popcorn but kind of Cracker Jacks.” Here, you think Engel’s deference to popular varieties like Sauvignon Blanc and Chardonnay demonstrates an admirable respect for mainstream tastes. At the same time, Grüner Veltliner represents a sommelier favorite, and its juxtaposition with the restaurant’s famous hummus forms a great lure to get the grape into people’s glasses.

On the “Rosé / Orange” side of things, you find Massaya’s 2020 rosé of Cinsault ($14) from Lebanon; Iconic’s 2021 “Shapeshifter” ($16), an orange wine made from Pinot Gris in Mendocino County; and Proxies’s “Zephur” ($12), a “fantastic rosé wine alternative” also (like the aforementioned “Bulle”) made in Ontario. The annotations offered for the first two bottles (“on Wednesdays we wear pink” and “looks best in orange”) are not particularly informative, but rosé is popular enough to sell itself and merely offering any kind of orange wine by the glass is impressive. The latter offers servers the chance to enlighten guests on an entire category they might not have known existed. Finally, in the “Red” section, are listed Chateau Musar’s 2020 “Jeune Rouge” ($15), a blend of Cinsault/Syrah/Cabernet from Lebanon; Mersel’s 2020 “Lebnani Ahmar” ($13), a varietal Cinsault from Lebanon; and IXSIR’s 2017 “Altitudes” ($16), a blend of Cabernet Sauvignon/Caladoc/Syrah/Tempranillo also from Lebanon. The annotations here do not, once more, provide much help; however, Galit has the distinction of pouring its Musar “Jeune Rouge” for one dollar less than Aba.

Overall, Engel’s by-the-glass offerings are rather distinctive and pretty well balanced in their approach to popular tastes. Selling Champagne, you have already noted, would likely be an expensive pitfall, but the presence of a Sauvignon Blanc (compared, no less, to Sancerre), an oaked domestic Chardonnay, and a rosé ensure many of the pickiest drinkers can quickly find a suitable option. These are balanced by bolder choices like the Grüner, the orange wine, and the trio of Lebanese reds. But, in truth, Cabernet Sauvignon drinkers (whom you might also describe as a bit particular) will see their favorite grape represented in two blends. Yes, rather, it is the Pinot Noir devotees who stand to be put out by the selection. However, the 100% Cinsault that is poured should suit their needs if the stylistic similarity (medium-light body, medium acidity, fruity/floral notes) is explained. Given that the menu’s annotations cannot be relied upon to be particularly enlightening, that burden falls on the staff and tests Engel’s own ability to be a wine educator for the wider establishment.

Turning toward the bottle list, you first come across the “Fizzy, Sippy, Peppy, Bubbles” category that, at present, contains five bottles:

- 2021 Dalton, “Pét Nat” (Galilee, Israel) [$90]

- 2018 Grover Zampa, “Soirée” Brut (Nandi Hills, India) [$65]

- NV Piollot Père & Fils, “Cuvée de Réserve” Brut (Champagne) [$130]

- NV Cruse Wine Co., “Tradition” Rosé (California) [$150]

- NV Hobo Wine Company, Sparkling Apple Cider (Sonoma County) [$64]

These options, while few, are well balanced. For you have “Israel’s first Kosher pet nat” (as the annotation attests) to match Engel’s cuisine and an Indian sparkling Chenin Blanc (in place of Crémant or Prosecco) to offer value. While you have never heard of Piollot’s Champagnes, the bottle appears to offer a good drinking experience for the price and, in its relative modesty, resists the temptation many restaurants feel to stock Cristal, Dom Pérignon, or Veuve Clicquot in order to snare those celebrating a special occasion. By comparison, it may seem strange that the domestic sparkling costs more. However, Michael Cruse is undoubtedly America’s master of the craft, and his wines often drink better than their French counterparts. Finally, Hobo Wine Company’s sparkling apple cider—“Kenny’s first cider (and first sparkling anything)”—offers a fun, slightly different option that hints at the chef’s friendship with the winemaker.

Moving on, you come to the “Middle East” category and its opening “White / Rosé / Orange” section, which comprises:

- 2020 Tishbi, Emerald Riesling (Galilee, Israel) [$45]

- 2017 Királyudvar, Tokaji Sec [Furmint] (Tokaj-Hegyalja, Hungary) [$60]

- 2018 Cremisan, “Star of Bethlehem” [Hamdani/Jandali] (West Bank, Palestine) [$56]

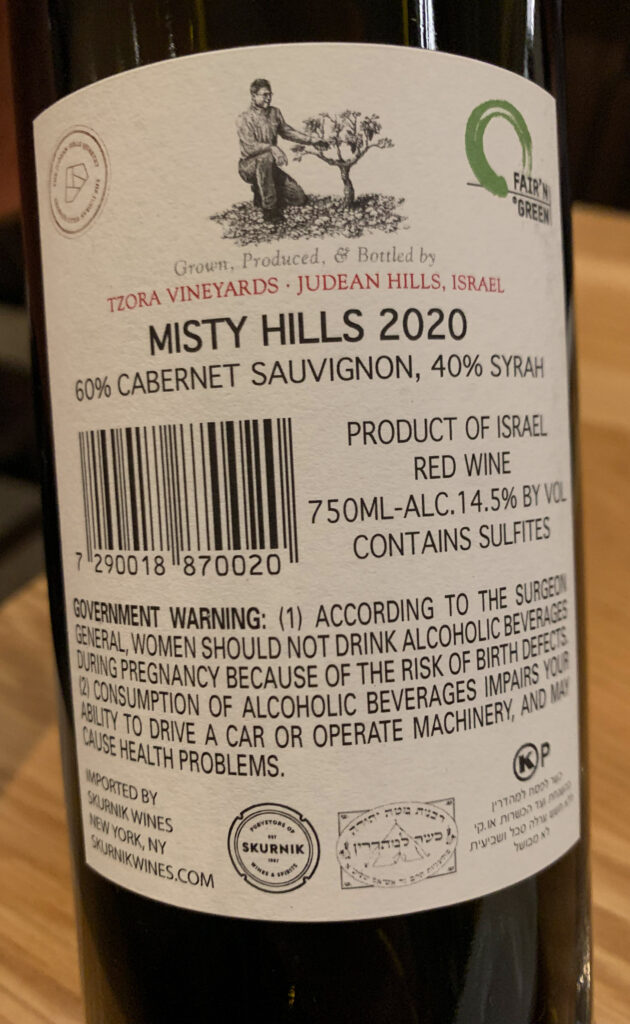

- 2021 Tzora, “Judean Hills” [Chardonnay/Sauvignon Blanc] (Judean Hills, Israel) [$120]

- 2020 Tzora, “Shoresh” [Sauvignon Blanc/Chardonnay] (Judean Hills, Israel) [$140]

- 2012 Chateau Musar, “Gaston Hochar” [Obaideh/Merwah] (Bekaa Valley, Lebanon) [$225]

- 2021 Agur, Rosé [Cabernet Franc/Grenache/Mourvèdre] (Judean Hills, Israel) [$100]

- 2021 Mersel, “Phoenix” [Merwah] (Wadi Qannoubine, Lebanon) [$65]

Here, you find the expression of Riesling you might have wished to see on the by-the-glass list (though Grüner, especially when sold as a pairing for hummus, certainly fits the bill). However, Emerald Riesling—incorrectly stylized as “Emerald” (as if it were the wine’s title and not its variety) on Galit’s list—is actually a cross of Riesling with Muscadelle that shows a slightly grapier character. Still, at $45, it represents a bargain—as do the Furmint and especially the Palestinian blend (the latter of which also affirms the restaurant’s multicultural grounding). The two Tzora wines represent alternating takes on a pair of the most popular white grapes, with the Chardonnay-dominant blend being billed as “elegant as sh*t.” At $120 and $140, they represent more premium options while the 2012 Chateau Musar offers an even more expensive, aged expression (though perhaps of dubious value). Lastly, the Israeli rosé benefits from its use of Provençal varieties (at a price that far surpasses the bulk wine category) while the lone orange (Mersel, “Phoenix”) can boast being a “cool kid wine from 150-year old [sic] indigenous vines” at just $65.

Next, the “Red” section of the “Middle East” category includes:

- 2020 Dalton, “Magestic” [Carignan] (Galilee, Israel) [$78]

- 2018 Weninger, “Balf” [Kékfrankos] (Transdanubia, Hungary) [$60]

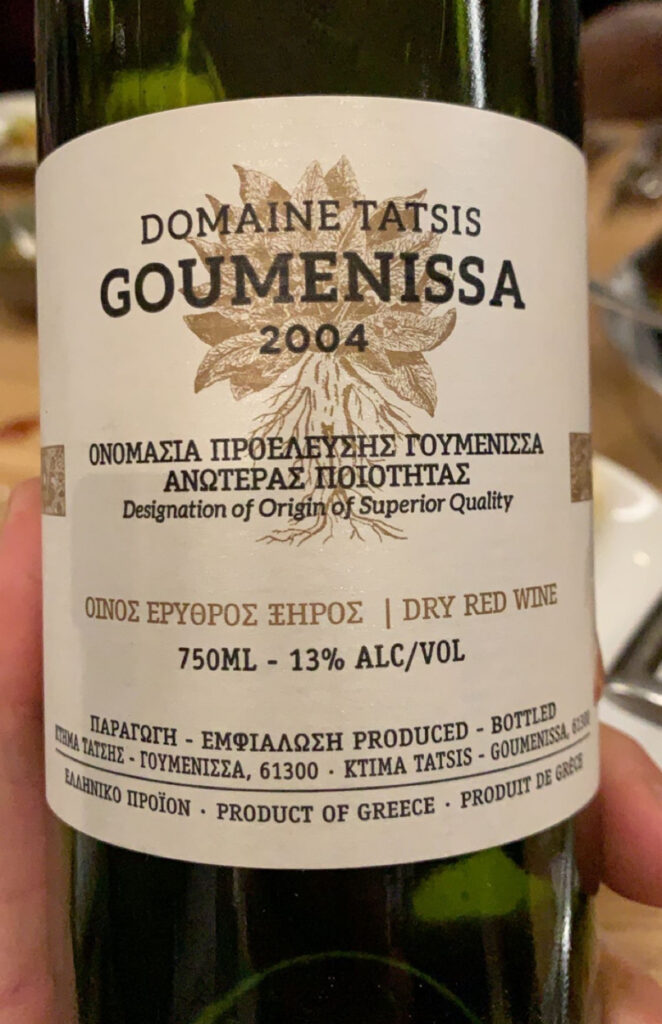

- 2007 Domaine Tatsis, Goumenissa Estate [Xinomavro/Negoska] (Goumenissa, Greece) [$110]

- 2017 Rikars, “Arag Amphora” [Areni Noir] (Vayots Dzor, Armenia) [$80]

- 2014 Ramot Naftaly, “Primo” [Barbera/Merlot] (Galilee, Israel) [$125]

- 2020 Chateau Musar, “Levantine de Musar” [Cinsault/Tempranillo/Cabernet Sauvignon] (Bekaa Valley, Lebanon) [$100]

- 2016 Chateau Musar, “Gaston Hochar” [Cabernet Sauvignon/Carignan/Cinsault] (Bekaa Valley, Lebanon) [$170]

- 2000 Chateau Musar, “Gaston Hochar” [Cabernet Sauvignon/Carignan/Cinsault] (Bekaa Valley, Lebanon) [$225]

- 1996 Chateau Musar, “Gaston Hochar” [Cabernet Sauvignon/Carignan/Cinsault] (Bekaa Valley, Lebanon) [$225] [375mL]

- 2018 Dar Richi, “Hanan” [Cabernet Sauvignon/Malbec/Sangiovese] (Bekaa Valley, Lebanon) [$75]

- 2017 Massaya, “Cap Est” [Grenache/Mourvèdre] (Bekaa Valley, Lebanon) [$98]

- 2013 IXSIR, “Grande Reserve” [Syrah/Cabernet Sauvignon] (Batroun, Lebanon) [$86]

- 2019 Pelter Matar, “Stratus” [Shiraz] (Galilee, Israel) [$110]

- 2020 Sclavos, “Orgion” [Mavrodaphne] (Cephalonia, Greece) [$66]

- 2018 Margalit, Cabernet Franc (Shomron, Israel) [$200]

- 2012 Margalit, Cabernet Franc (Shomron, Israel) [$275]

- 2018 Margalit, “Enigma” [Cabernet Sauvignon/Merlot/Cabernet Franc/Petit Verdot] (Shomron, Israel) [$225]

- 2020 Tzora, “Misty Hills” [Cabernet Sauvignon/Syrah] (Judean Hills, Israel) [$300]

- 2014 Somek, Carignan (Shomron, Israel) [$160]

- 2019 Domaine du Castel, “Petit Castel” [Merlot/Cabernet Sauvignon/Petit Verdot] (Judean Hills, Israel) [$135]

- 2019 Domaine du Castel, “Grand Vin” [Cabernet Sauvignon/Merlot/Petit Verdot] (Judean Hills, Israel) [$210]

This assortment, which is organized (as is the entire list) from lighter to heavier styles, is clearly weighted toward more robust varieties. After the Dalton “Majestic” Carignan (“glou glou from Galilee”), Weninger “Balf” Kékfrankos (“pomegranate. paprika. white pepper … are you Hungary yet?”), Domaine Tatsis Xinomavro/Negoska blend (“the OG Greek natty winery”), and Rikars “Arag Amphora” Areni Noir, you immediately jump to a wider array of wines made from Cabernet Franc, Cabernet Sauvignon, Grenache, Malbec, Merlot, Petit Verdot, and Shiraz/Syrah. As a Burgundy drinker, this presents a problem (though you understand that Pinot Noir is likely too fickle to produce quality wine in the Middle East). But you would probably opt for the nicely aged, minimal intervention Domaine Tatsis, whose Xinomavro grape is often compared to Nebbiolo.

Otherwise, it is worth noting the range of options under and around $100 (a positive) as well as the focus on Israeli wines at the very top end of the selection. Apart from Chateau Musar, “the most important wine made in Lebanon” (and probably the most well-known across this category), bottles from Margalit, Tzora, Somek, and Domaine du Castel—sourced from the Shomron and Judean Hills regions—command the highest prices across the entire list. They are accented by annotations like “so good Chef Zach named his daughter after it,” “ask Andrés about this one,” and “idk. this one slaps” that act as personal testimonials and affirm (perhaps tacitly) that these wines offer the ultimate drinking experience alongside Engel’s cuisine.

The ”(mainly) Sonoma” category, at present, comprises four whites and five reds:

- 2021 Banyan, Gewurztraminer (Monterey) [$42]

- 2021 Populis, “Wabi-Sabi” [Chardonnay/Sauvignon Blanc/French Colombard/Others] (Mendocino County) [$60]

- 2020 Antihill Farms, Helluva Vineyard [Pinot Gris/Pinot Noir/Gewurztraminer] (Anderson Valley) [$75]

- 2016 Iconic Wines, “Heroine,” Michael Mara Vineyard [Chardonnay] (Sonoma County) [$120]

- 2020 Hirsch Vineyards, “The Bohan-Dillon” [Pinot Noir] (Sonoma Coast) [$115]

- NV Thackrey & Co., “Pleiades XXVIII” [Sangiovese/Pinot Noir/Viognier/Others] (California) [$75]

- 2017 Leo Steen, Provisor Vineyard [Grenache] (Dry Creek Valley) [$100]

- 2008 Jonata, “Tierra” [Sangiovese] (Santa Ynez Valley) [$125]

- 2019 Anthill Farms, Peugh Vineyard [Zinfandel/Others] (Russian River Valley) [$110]

Meanwhile, the “Pretty Much Everywhere Else” category contains one white, three orange wines, one rosé, and four reds:

- 2021 Gen del Alma, “Jijiji” [Chenin Blanc] (Tunuyán, Mendoza) [$50]

- 2021 Meinklang, “Mulatschak” [Welschriesling/Pinot Gris/Traminer] (Austria) [$60]

- 2021 Day Wines, “Vin de Days l’Orange” [Müller-Thurgau/Riesling/Others] (Willamette Valley) [$75]

- 2020 González Bastías, “Naranjo” [Moscatel/Torontel/País] (Maule Valley, Chile) [$80]

- 2021 Frank Cornelissen, “Susucaru” Rosato [Malvasia/Nerello Mascalese/Others] (Etna, Sicily) [$80]

- 2020 Clos des Fous, “Pour Ma Gueule” [Pinot Noir] (Itata Valley, Chile) [$48]

- 2019 González Bastías, “Matorral” [País] (Maule Valley, Chile) [$60]

- 2021 Stranger Wine Company, Cabernet Franc (Lake Michigan Shore) [$80]

- 2018 Tikveš, “Barovo” [Kratosija/Vranec] (Tikveš, North Macedonia) [$75]

Relative to the “Middle East” selection, you always assumed that Galit’s “(mainly) Sonoma” and “Pretty Much Everywhere Else” categories would offer guests a more orthodox route to choosing a bottle of wine. In practice (at least at present), you only note a few options that fit the bill: the 2016 Iconic Wines “Heroine” Chardonnay, the 2020 Hirsch “The Bohan-Dillon” Pinot Noir, and Thackrey’s “Pleiades XXVIII.” The first two, of course, benefit from offering renditions of mainstream grape varieties grown in the well-known region of Sonoma. The third, though comprising a rather eclectic (and ultimately unknown) blend of Sangiovese, Pinot Noir, Viognier, Mourvèdre, and more, comes from a producer with a loyal following and a high degree of brand recognition. This latter bottle’s presence in retail channels and overall affordability might make it seem particularly familiar and, thus, a safe choice.

The rest of the options include varietal wines made from Chenin Blanc, Gewurztraminer, Cabernet Franc, Grenache, and Sangiovese. There’s even another Pinot Noir on offer made in Chile’s Itata Valley. However, separated from the appellations in which they have asserted their quality, these grape varieties run the risk of seeming obscure. Does the “mainstream” Anjou, Saumur, Alsace, Chinon, Châteauneuf-du-Pape, Brunello, or Chianti drinker (if you are to go out on a limb and assume that each of these distinct preferences actually exist) know enough to recognize their favorite wine in different trappings? Would they be able to stomach it, stylistically, when grown on different soil in a different climate?

More principally, the “(mainly) Sonoma” and “Pretty Much Everywhere Else” categories are dominated by blends that you can only term singular. Some make use of recognizable grapes like Chardonnay, Pinot Gris, Riesling, Sauvignon Blanc, Pinot Noir, and Zinfandel but pair them with each other (atypical in its own right) or with strangers like French Colombard, Moscatel, Müller-Thurgau, Torontel, Traminer, Vrances, Welschriesling or minor amounts of unnamed varieties. While these blends are certainly characteristic of natural winemaking—offering kaleidoscopic aromas and flavors meant for early drinking—they do not read well on paper. Of these producers, only Frank Cornelissen’s name carries the kind of “street cred” that might induce someone who enjoys more traditional styles to take a leap. Otherwise, the annotations provided—like “your server’s fave,” “co-fermented field blend from historic vines,” “peaches and cream,” and “an iron fist in a velvet glove”—hardly offer much help.

The pride of place given to Galit’s wine program, from the concept’s inception through the early-2022 renovation and expansion of its cellar, is clear. And Engel expanded on the philosophy guiding his selection as recently as last August in an article titled “These Superb Middle Eastern Wines Are Pretty Much Exclusive to This Michelin-Starred Chicago Restaurant.” Therein, the restaurant is said to boast “a bold panoply of bottles hailing chiefly from Sonoma” (where the chef moved “literally to learn more about wine”) and “the Middle East, home, notably, to the vintage first quaffed in his early 20s.” With only two glass pours and 11 bottles on offer from the “(mainly) Sonoma” category, it does not quite “chiefly” make up Galit’s offerings in the way that the Middle Eastern wines (five glass pours and 32 bottles) do. Nonetheless, it may be charitable to assume that, since August (and through the holiday season), some the former region’s options have been depleted and not yet replaced.

Moving on, Engel admits in the article that he has a “rule” in the restaurant: “We do not sell French or Italian wines at Galit. We do not sell Napa wines, either.” The intention behind this is to “gently educate” the “sort of consumers” who might say “I only drink Italian reds,” the goal being to get guests to “appreciate Middle Eastern wine and not think that all of it is bad, just because of a prejudice or a preconceived notion.” This is accomplished, the chef says, by “showing them a very well-executed wine that’s interesting and tells a story and goes with the food to kind of round out the experience.” However, he is also the first to admit that the “Kosher-specific” examples for which the region’s bottles may most be known are “not very good, sort of your very straightforward, grocery-store level wine.”

Despite that, Engel views “choosing wines from the Middle East” as “better maintaining the identity of the restaurant.” It emphasizes how the “rules have changed quite a bit” over the past 20 years of American dining, where “loud music” and “tapas-style small plates” were once “not OK” and “having anything but French or Napa wines on the list was looked at as low-brow.” In this context, the Middle Eastern selection demonstrates that the chef has not forgotten his “humble origins” and that he will continue to highlight “these specific regions that tell…[his] story” because they embody what makes the restaurant “so unique.”

In the rest of the article, Engel and Clavero share their thoughts on five particular producers: four from Israel and one from Lebanon. Beyond the specific names mentioned, it is enlightening to see how the duo articulates their wine knowledge. The chef describes himself as a “big cab franc guy” who likes it “by itself, not just as a supporting varietal” and thinks the “pyrazine [a compound that can lend flavors of green pepper…to certain wines] really plays well with a lot of our food at Galit.” Another bottle, a “50/50 blend of syrah and mourvèdre” is said to have a “floral quality” that “makes it the perfect pair for the restaurant’s more heavily spiced dishes, redolent with baharat or ras el hanout.” In particular, it is a “very easy sell” with a lot of lamb dishes, making a “complementary opposition” of “floral and spicy and salty” wine with “umami and fresh and yeasty” meat plus veg.

Of the Lebanese wine, Engel shares his “good personal relationship” with the producer, whom he met after buying the bottles for years. The label’s “natural, low-intervention methods and native grapes” represent “the new wave of winemaking from a country where people really only know about Chateau Musar, if they know anything about it.” Lastly, an Israeli take on Barbera is termed the chef’s “go-to to change the minds of clients who claim Italian reds are their be-all and end-all.” It’s “grown not that far from where you would [typically] get” the variety and offers “a unique exploration of a grape that’s familiar to many, revealing a whole different side of its personality.”

Engel and Clavero, to their credit, demonstrate an admirable degree of wine knowledge as expressed both through the broad stylistic underpinnings of their chosen pairings and the technical or sensory qualities that define particular bottles. They care about how the vines are grown and the stories of those who cultivate them. They care to challenge how Chicagoans—and, with Galit’s national acclaim, even Americans—perceive fermented grape juice sourced from outside the most commercialized “major” regions. And, in doing so, they are helping to restore the reputation of the Middle East’s ancient winemaking traditions and connect these diverse expressions of terroir to their own personal stories and the essence of the restaurant’s cuisine. This is as beautiful a vision as any wine program can claim, and Galit—in truth—remains as committed as ever to executing it.

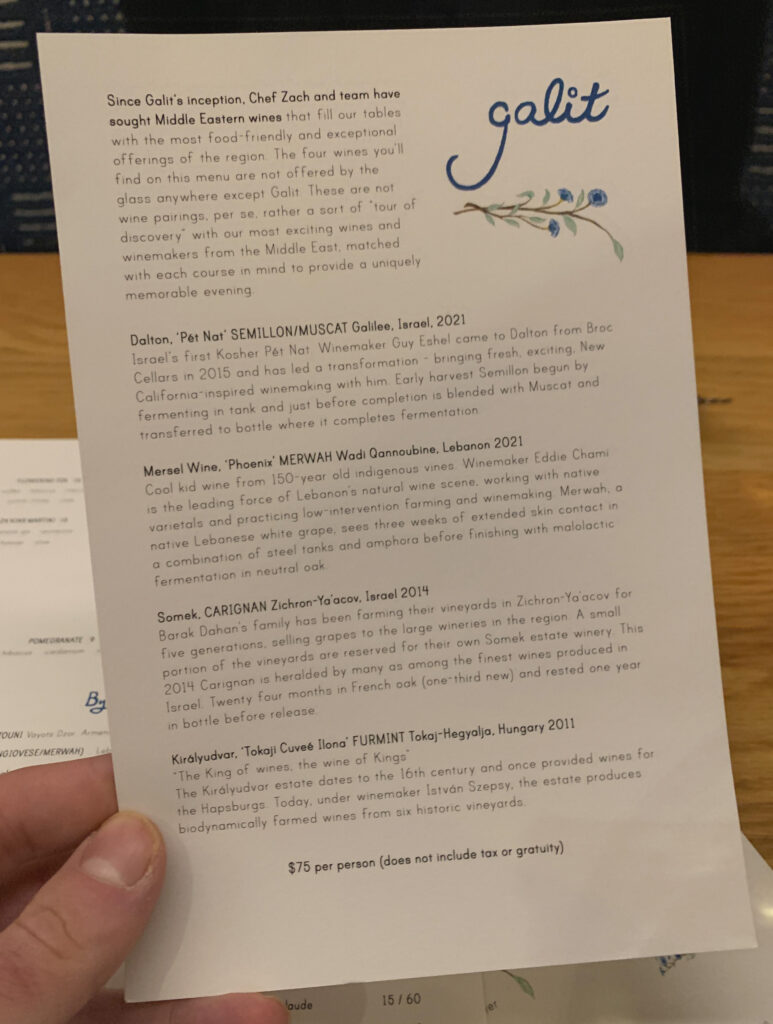

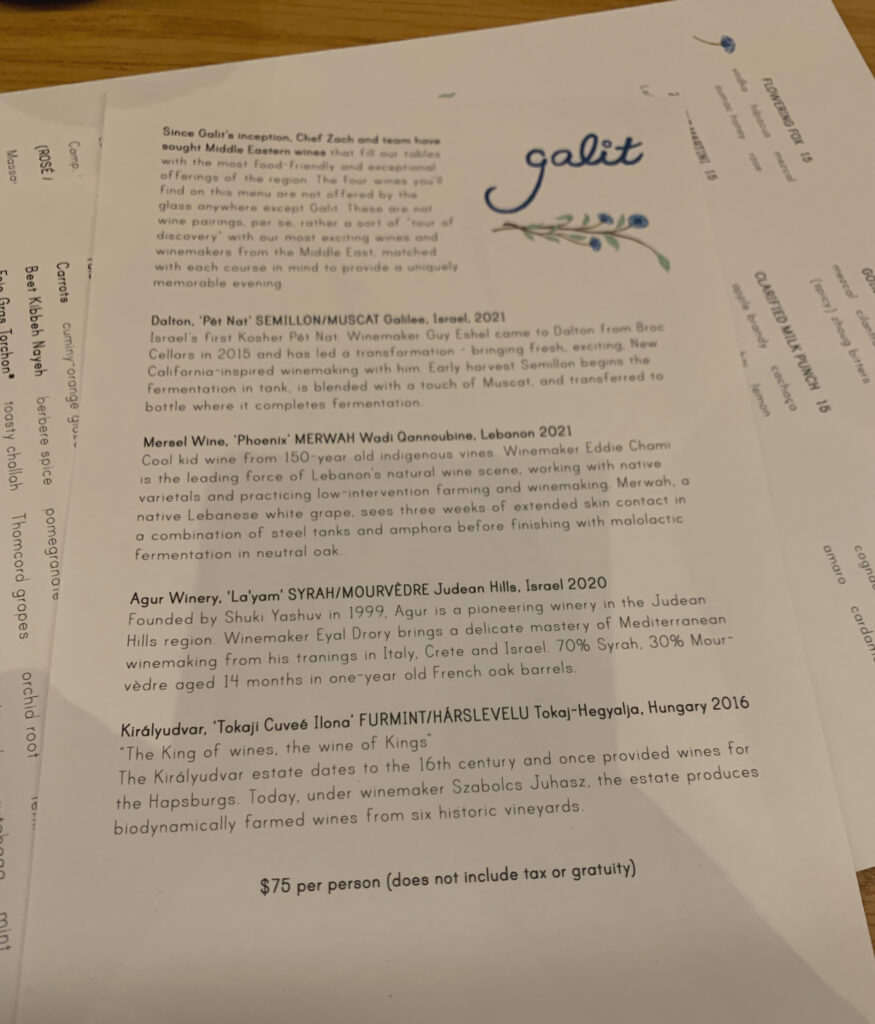

In mid-January, the restaurant launched its newest initiative: a “Middle Eastern wine menu” meant to “take your Galit experience to the next level.” Guests arriving at the table will now find that a small additional piece of paper awaits them alongside the usual prix fixe and bottle list. The document stresses how the restaurant has “sought” the most “food-friendly and exceptional offerings of the region” since opening and, for $75, features a selection of four wines that are “not offered by the glass anywhere except Galit.” Nonetheless, these are not billed as “wine pairings, per se, [but] rather a sort of ‘tour of discovery’” centered on the concept’s “most exciting wines and winemakers from the Middle East, matched with each course in mind to provide a uniquely memorable evening.”

This kind of turnkey solution effectively allows the restaurant to steer guests (who might otherwise order a couple glasses of wine or cocktails) toward a more cohesive drinking experience without asking them to make sense of the exotic varieties on the bottle list. It also allows Engel and Clavero to share their passion for the four chosen bottles via the blurbs written on the separate menu. So far, the selection has included the 2021 Dalton “Pet-Nat” ($90) and 2021 Mersel “Phoenix” ($65) for the first two courses. The main course has been paired with the 2014 Somek Carignan ($160) that, later, was substituted for the 2020 Agur “Layam” ($115). Dessert, finally, has been served with 2011 (and, later, 2016) vintages of Királyudvar’s “Cuvée Ilona” Tokaji. Though it is interesting to see the bottle price of this pairing’s “main” red wine vary to such a degree, $75 still seems like a good value for four diverse glass pours from wines that generally cost a good bit more than the pairing itself. Best of all, it induces patrons to sample wines the chef is excited about by nesting them within a perfectly curated, ”next level” Galit experience (rather than trying to make such a conversion once someone has already gotten confused by what they read on the wider list).

Ultimately, Engel has put together a program that, from the by-the-glass pours, through the bottle list, and now including the “Middle Eastern wine menu,” almost seems impenetrable from a critical perspective. How can you take aim at a selection that tells the story of the chef’s own vinous appreciation? What flaws can you find with an assortment of wines that are so finely woven into the restaurant’s identity—so singularly expressive of the same “place” (or “places”) the cuisine aims to invoke?

Well, first, you noted your expectation that the “(mainly) Sonoma” and “Pretty Much Everywhere” categories would offer a more approachable counterpoint to the “Middle East” section. Galit once stocked producers like Evening Land, Failla, Matanzas Creek, Patricia Green Cellars, Ridge, Roger Pouillon, Schramsberg, Smockshop Band, Sylvain Pataille, and Von Hovel, but these bottles are now missing. Instead, you now only find Cruse Wine Co., Frank Cornelissen, Hirsch Vineyards, and Thackrey as recognizable names among a sea of orange wines, co-fermented blends, and robust reds that serve to replicate the varieties already represented across the “Middle East” category. Where are producers like Domaine de la Côte, Lingua Franca, Littorai, Liquid Farm, Phelan Farm, Sandhi, Sandlands, and Under the Wire? Where are the other biodynamic expressions of Chardonnay or Pinot Noir? Imbibers like yourself who favor these varieties—grapes that stand at the very forefront of the luxury wine market and the “natural” wine movement alike—are left scrounging for even one good option. Is it so much to ask for a couple restrained, Burgundian-styled bottles (the very sort that, if oak use is effectively managed, could pair Engel’s cuisine without any problem)?

Next, with the dilapidation of the “(mainly) Sonoma” and “Pretty Much Everywhere” categories in mind, why does the restaurant continue to abide by its silly rule: “We do not sell French or Italian wines at Galit. We do not sell Napa wines, either”? The presence of French Champagne and Frank Cornelissen’s Sicilian rosato on the list would seem to signal that this restriction is not as serious as Engel claims. So why not resolve to simply curate the best “natural” wines from around the world as the counterpoint to the “Middle East” section? This would still ensure the restaurant could challenge palates, for your garden-variety Cabernet Sauvignon, Chardonnay, Merlot, Nebbiolo, Pinot Noir, or Sauvignon Blanc would not quite fit the bill. Rather, these recognizable varieties would serve as lures to help guide guests toward trying a wine that seems ordinary and approachable on the surface but reflects the kind of agricultural practices the chef values. This seems like a slightly more subtle and effective route toward extolling the virtues of biodynamics without drawing a more stereotypical association between “natural” winemaking and all manner of funky grapes and styles.

Most importantly, ditching the “we do not sell French or Italian wines” rule would allow the restaurant to stock wines from the Jura, Loire, and Savoie regions—each famous for minimal intervention winemaking of indigenous grapes. Beaujolais, Burgundy, Champagne, Friuli, Piedmont, and Tuscany have plenty of up-and-coming biodynamic producers worth supporting too. This is all to say: evangelizing “natural” wine is hard enough as it is. Trying to do so with one hand tied behind your back—denying your program access to the regions that have mastered the craft of regenerative agriculture—seems destined to fail. It also seems counterproductive to paint “natural” wine, as the “(mainly) Sonoma” and “Pretty Much Everywhere” categories do, with more of an ostentatious, quaffable brush rather than stocking producers of the highest quality. Doing so does not—mind you—mean demanding a higher price. For “natural” wines present some of the finest bargains on the lists at places like Boeufhaus, Elske, Kyōten, and even Le Select, with producers like Anders Frederik Steen, Buronfosse, Claire Naudin, Domaine des Ardoisières, Domaine du Collier, Domaine du Pélican, Fabio Gea, Ganevat, Giovanni Canonica, Guiberteau, Jean-Yves Péron, Maison Valette, Marc Soyard, Radikon, Salicutti, Stein, Tissot, and Vocoret represented throughout the city.

This all leads to your final and most consequential point. The “(mainly) Sonoma” and “Pretty Much Everywhere” categories seem intentionally devalued (via a lack of broadly appealing options) in order to shift attention toward the “Middle East” category. There, wines are marked up close to three times the retail price (that, when you consider the restaurant’s wholesale pricing, might come out to four or five times what Galit actually paid). Consider, at the low end, the 2020 Tishbi “Emerald” Riesling that is sold for $45 and maintains a Wine-Searcher average of $15 or, at the high end, the 2018 Margalit Cabernet Franc that is sold for $200 and maintains a Wine-Searcher average of $75. You may also cite the 2000 Chateau Musar rouge that is sold for $225, maintains an $81 Wine-Searcher average, and is also offered at Aba for only $200.

Viewed from this perspective, Galit’s wine list seems content to confuse customers and drive them into the arms of the “Middle East” section. With the promise that these bottles make for a fitting match with the restaurant’s cuisine, patrons—still rather unfamiliar with what they are buying (save for a few recognizable grape names)—will happily overpay. They’ll end up with something palatable but hardly impressive in terms of quality-to-price-ratio. The experience will feel cohesive—a fun novelty beverage attached to their meal—but hardly transcendent.

(There is, perhaps, something to be said about placing spiced and roasted meats alongside the robust grape varieties grown in the Middle East, but tailoring so much of the list to fit this purpose is overly prescriptive. In your experience, Engel’s food is balanced enough to match with more delicate wines, and doing so would honor the dynamism of the chef’s cuisine more than such a restrictive and formulaic approach to pairing. Is it wrong to say that Galit’s fare is, itself, more interesting than anything being bottled in the Middle East anyway?)

You do not fault Galit for trying to support producers and winemaking cultures that the chef feels a connection to. Yet, it is also clear that Engel does not have much respect for wine professionals—“the wine industry doesn’t do a good job of making people feel comfortable,” and “I want to eliminate the disconnect between a wine professional and the person looking at the menu” he said in 2019. The annotations, as you have covered extensively, do not really do that. They can be clever at times (and cringeworthy at others) but remain nothing more than a band-aid.

Restricting consumer choice to a couple pet regions and styles of wine does not “make people feel comfortable” or “eliminate the disconnect” either. It is easy to throw everything at the wall within a couple categories (you are reminded of Ever’s list) and see what sticks. It is much, much harder to simply curate the best possible wines from the entirety of the vinous world and organize this wide range of options in some legible way. You think Galit has chosen the easier path knowing that they have something of a captive audience along with enough nascent wine knowledge to shock and awe diners who otherwise care little for the pleasures of the vine. You also think the restaurant views wine more as a beverage—a profit center—than a part of the experience meant to surprise and delight its patrons.

You obviously cannot sample all of Galit’s Israeli and Lebanese wines—let alone under blind conditions—in order to make an even partially valid claim about the regions’ overall quality. Yet you do not think you are fueled by any “prejudice” or “preconceived notion” that leads you discount what the restaurant is selling. Rather, if you have learned anything about wine, it is that something like only 1% of producers in any given region are truly exceling in their craft and offering consumers a distinctive, consistent style that also offers some degree of value. This has little to with the actual price being charged (insofar as one is willing to spend more than $20-$30) and more to do with how hard it is to master one’s art and understand one’s terroir. It also has to do, like cookery, with the dues one must pay in order to learn from those precious few luminaries that stand like giants over each generation of winemakers.