Smyth is Chicago’s greatest restaurant—perhaps ever—and you have remained resolute in that declaration since first dining there in September of 2017.

Just over three years following that fateful first visit, sitting out on Smyth’s patio, you found yourself face-to-face with a far different world. Yet the restaurant, ragged from the pandemic’s toll and reeling from the looming rollback of restrictions, never seemed more beautiful.

That evening, the final dinner of Smyth’s “Farm Series” concept (a sequence of three meals scheduled throughout the year so as to celebrate the peaks of the season’s produce) had been disfigured due to the ravages of the virus. What should have been a trio of menus set in May, July, and September was altered to encompass July, September, and November instead. As luck would have it, unseasonably warm weather (and a rather effective heater placed under the table) allowed for the last of the meals to still take place.

That evening—perched between two concrete planters on the sidewalk along Ada Street, seated in the shadow of the residential building which replaced the parking lot that once sat across from the building—you were served one of the finest meals of your life. Despite shedding scores of talented staff, of twisting and turning to meet the challenges of the black swan consuming the hospitality industry, Smyth put out a menu that was stupefying in its creativity (you had just eaten there one month before) and faultless in its finesse.

On that brisk evening, you celebrated your fiftieth meal at Smyth. Fifty visits is an incomparable, inconceivable number for any “fine dining” or “special occasion” restaurant. You do not, for the sake of both anonymity and propriety, typically like to reveal (or revel in) such benchmarks. But, in some sense, the number stands as a shorthand, a testament to how unerring Smyth’s hospitality and exploration of Illinoisan terroir have been during the course of time it has been open. Smyth, as best as you can put it, is the “real deal.” It forms a fitting model for the “American restaurant” of the future. And, more than that, it is filled to the brim with heart and soul.

Dining at Smyth, on any and every given night, has presented you with the rarest, most transcendent of all hospitality experiences. It is a place that makes the phrase “restaurant family” ring hollow when applied to any other establishment. Smyth’s dining room is one where the guest cannot help but engross themselves in the rhythm of service, of forming—through true encounters with kindred spirits—yet another strand in the tapestry of the restaurant’s living history. You will not obscure the fact that Smyth inspires you—that it may have, more than nearly any other restaurant, inspired the very substance of this website. But trust, dear reader, you are not being dramatic when you declare that fiftieth meal at Smyth to be one of the greatest of your life. For diamonds are made under pressure, and the restaurant—pandemic or not—shows no signs of slowing down.

John Shields is something like the “beloved uncle” of Chicago hospitality—the sort of uncle whose absolute mastery of his craft never gets in the way of his earnest, easygoing manner. Starting his career in St. Louis, Shields cut his teeth through coveted positions at two of the Windy City’s most legendary restaurants. He served as sous chef at Charlie Trotter’s for two years before spending another two years as the opening sous chef of Alinea, a set of experiences at the nexus of culinary history that anyone would be hard-pressed to surpass. Meanwhile, Karen Urie (later to become Karen Urie Shields) was enjoying her own climb to the pinnacle of the pastry world. Moving to Chicago from Rhode Island, she worked for two years as sous pastry chef under James Beard Award winner Gale Gand at TRU before spending six years at Charlie Trotter’s, rising to the role of head pastry chef.

The couple’s command of both sweet and savory drew the renewed attention of Charlie Trotter himself, who tapped the Shieldses to open a Las Vegas location of his namesake restaurant. Though running a luxe offshoot of the renowned establishment where the two had worked seemed like “the obvious next step,” John and Karen—in a move as wise as it was risky—chose to forge their own path. They relocated to Chilhowie—a town of 1,827 at the crossroads of Virginia, North Carolina, Tennessee, West Virginia, and Kentucky—in response to an ad placed on Chicago’s Craigslist site:

The owners of Chilhowie’s Town House Grill were looking to transform their steak and seafood joint into a proper destination restaurant, and—after ensuring the couple was prepared to work in the “middle of nowhere”—they gave the Shieldses complete creative control to make it so.

Rather than do their best rendition of Charlie Trotter’s cuisine under the shining lights of Sin City, John and Karen—having both just turned 30—devoted their halcyon days to self-expression. They channeled their estimable technical knowledge towards developing their own voice on their own terms, approaching Appalachia’s natural bounty with unseen skill. Early dishes—like foie gras cotton candy or liquid nitrogen-frozen marshmallow “moss”—seem straight out of Alinea’s playbook. Others—such as a chilled “minestrone” made from nine different vegetables or marinated oysters served simply with peas and dashi—speak to Charlie Trotter’s worship of local ingredients. However, neither of the Shieldses stylistic influences are determinative. Then, as they do now, the two knew just what elements to take inspiration from and those which are best to discard. Thus, Alinea’s technical wizardry is showcased in a playful (rather than polarizing and needlessly abstract) style while Charlie Trotter’s precise preparations of produce, fish, and flesh are freed from any pretentiousness.

The end result, of course, was a style unto their own (one which, you think, has always proven to be a kindred spirit with the “New Nordic” movement). Opening in 2008, the twenty-six seat restaurant (later growing to thirty-five) served a four-course tasting menu for $48 and a nine-course menu for $90, eye-popping prices today. By 2009 (when its chefs earned a glowing feature in the New York Times), Town House had succeeded in seducing gastronomes from around the Mid-Atlantic to take the trek to Chilhowie. 2010 brought John the honor of being named one of Food & Wine’s “Best New Chefs” in the country. Then, in 2011, he was named a semi-finalist for the James Beard Foundation’s Best Chef: Mid-Atlantic award. Without question, the Shieldses decision to take their destiny into their own hands had paid off.

By the time Town House closed in 2012, John and Karen had developed a firm culinary philosophy of their own that would later find a home at Smyth. Looking back at their “Town House Blog” (now defunct, but available through internet archiving), one notes the genesis of a style that applies Alinea’s advanced techniques towards refining flavors and constructing novel assemblages of ingredients while, at the same time, making sure never to deny the classic, comforting essence of a dish’s central component. In this sense, Charlie Trotter’s philosophy comes into focus. However, instead of filtering native ingredients through the lens of fine French cookery, the Shieldses embrace the local bounty as Americans through and through who feel no need to embellish nature’s own designs for the sake of pleasing cosmopolitan palates. Like John and Karen themselves, nothing about the plates is put on. They are tranquil, at peace, yet infinitely complex under the surface. Any ostentation—when it does appear—is altogether playful. Such dishes greet the guest with a wink and a nod—with generous, nostalgic flavors—and no sense of cold, craven “luxury.”

Dishes from that era include ocean trout (dressed in a broth of mussel juice, oyster juice, pork stock, butter whey, and dill oil), a lardo-lined “empanada” (filled with crispy pork tail, fried corn, and goat cheese cream), lamb cooked in smoked butter (served with beets and caramelized yogurt), lobster (with coral cream, lobster consommé, and lobster oil), beef cheek cooked in hay (garnished with corn sprout, milk skin, oats, and toasted grains), and barbequed asparagus (plated with candied lovage, cured egg yolk, Meyer lemon, and shad roe). You wish you could write out all the ingredients listed for each of those dishes but, for the sake of space, had to settle for the most interesting few. Immediately, one notes how Shields—even back then—marked his cuisine through a layering of complementary flavors. The “lobster” dish tastes even more like lobster through the incorporation of consommé and oil into the sauce. The “ocean trout” dish benefits from the juice of two shellfish—and even from pork stock and butter whey, which lend the fish a richness it might never otherwise have. Thus, any interesting “twists” (like the coral cream or dill oil) stand on a foundation of the principle ingredient’s signature flavor. They provide just enough novelty to tantalize the palate and play off of the intensity of flavor constructed via layering.

Tellingly, a dish like the “barbequed asparagus” receives the same treatment. It is not only given center stage in the same manner a piece of animal protein or seafood would, but it is dressed up in the same fashion: cured egg yolk and shad (herring) roe amplify the vegetable’s richness while the candied lovage and cured Meyer lemon elements take the asparagus in a sweet and sour direction that works to offset its impressive char. That being said, the lamb and beef cheek preparations are no slackers either. The latter, in particular, looks like it makes masterful use of an assortment textured grains and sprouts to accentuate the tenderness of the so-called butcher’s cut. At the same time, milk skin—an ingredient you have only ever seen at Smyth—adds an ethereal sort of dairy richness to the beef. This is superlative savory cooking accomplished with no tricks, merely an aim of putting diverse ingredients, in distinct forms, to work with a focus on conjuring pleasure from the dish’s central component.

Looking at the sweeter side of things, Karen’s creations at Town House included a cocoa and black sesame “chewy meringue” (with wasabi and lime), a “broken” vanilla marshmallow (with preserved green strawberries, frozen lemon, and cucumber), a “liquid” chocolate bar (with an ice cream of burnt embers, sour yogurt, and muscovado), crabapple (with caramelized pudding, caraway seed tempura, and oats), and “fallen leaves” (made of painted white chocolate and served alongside Hubbard squash, Indian curry, chocolate “textures,” and granola).

From the start, one notes how each of these dishes revolve around showcasing an interesting textural expression of a familiar form: the meringue is “chewy,” the marshmallow is “broken,” the chocolate bar is “liquified,” the pudding is “caramelized,” and the chocolate in the latter dish is reduced to “textures” altogether. Accompanying ingredients—like the duo of wasabi and lime or the trio of burnt embers, sour yogurt, and muscovado—accentuate the dish from a variety of angles: heat and sour in the former; smoke, sour, and deep brown sugar flavors in the latter. And yet, the principle flavor could not be more familiar: cocoa/black sesame, vanilla, chocolate, apple, squash. Yes, the presentations—as in the case of the “fallen leaves”—may be arresting, but the essence of each dish is altogether pleasing. These are fundamentally comforting, nostalgic desserts that are deconstructed and put back together in such a way as to amplify flavor like never before. They assert that textural and visual abstraction need not come at the cost of satisfaction. Alinea, you think, should take notes.

When the Shieldses left Town House in 2012, the chefs made for Philadelphia. There, the couple would be among relatives who could care for their 9-month-old daughter as they ironed out plans for a restaurant of their own. First, rumors swirled that the in-demand duo was set for Washington D.C.. Then, later in the year, it seemed that they had decided on Philly—and were set to open a concept there similar to Town House in 2013. However, having “gotten virtually no interest from financial bakers” there, the Shieldses set sights back towards the nation’s capital. In February of 2013, the decision to open their new restaurant in D.C. was “100%,” and things were “all coming together.” Yet, little more than a year later, the Shieldses’ plans for a Georgetown restaurant had fallen through.

John and Karen, on the heels of this disheartening merry-go-round, headed back to where they had made their name. They installed themselves in a renovated farmhouse called Riverstead, which once served as an inn for guests who had made the long trek to Chilhowie for a meal at Town House. Rather than the thirty-five seats that comprised Town House, Riverstead only sat sixteen. The menu—twelve courses priced at $200—was only served one weekend per month. John and Karen would commute seven hours from Philadelphia for each limited engagement—until the couple welcomed their second daughter. Then, John would take to Twitter to shore up his team of two (Ryan Santos and Neal Wavra) with a few additional hired guns. The cooks would prepare most of the meal in the former Town House space before applying the finishing touches at Riverstead.

The menus at Riverstead—despite a few quixotic years out of action—express a further refinement of the Shieldses culinary style. One sees, you think, an even firmer connection to the work they would ultimately do at Smyth. Dishes from one exemplative menu dated August 2014 includes a Cope’s corn “sandy” (with pickled roses) and a sunchoke “cannoli” to start the meal. These are followed by dishes of beef tongue (with fresh cheese), tomato “seawater” (with trout roe), and mackerel (with Malabar spinach). The first bread course—a vegetable sourdough—precedes dishes of lightly smoked lobster (with grilled onion and pickled blueberry) and Dungeness crab (with roasted squid stock). The second bread course—a sprouted wheat biscuit (with boudin noir)—precedes a dish of lamb shoulder (with caramelized yogurt) and an intermezzo of duck heart, egg yolk, and licorice. A palate cleanser titled “embers of wintergreen branch & mint” leads to desserts of preserved carrot, sweet and dried corn (with elderflower and olive oil), and a kouign-amann to finish.

The ingredients listed for these dishes—retrieved off of a sample tasting menu rather than the more exhaustive Town House blog—are fewer. However, you think it is safe to assume that many of the same principles reside under the surface. The “lightly smoked lobster” likely benefitted by way of adjacent elements such as the aforementioned “lobster consommé” and “lobster oil.” As before, these components intensify the dish’s principal flavor while allowing for a more powerful contrast to emerge from accompanying notes like the “grilled onion” or “pickled blueberry.” Sure enough, the Dungeness crab sees itself paired with a “roasted squid stock,” which, you think, extends and expands the essence of seafood in the dish beyond the domain of the crustacean alone. Of course, an ingredient like “tomato seawater” embraces this idea even more: blurring the lines between the essence of the sea and that of the field. Paired with trout roe, such a creation takes the static idea of a “caviar course” into an entirely new domain, grounding it in a sense of place that transcends the coast.

While lamb shoulder paired with caramelized yogurt surely seems familiar (why mess with perfection), the duck heart dish is altogether new. The combination with egg yolk and licorice—while not quite clear (perhaps it functions as a transition into dessert)—foreshadows one of Smyth’s most classic desserts. Curing the egg yolk in a licorice syrup imbues it with chewy, then runny texture that blankets its bedfellows with a rich, wonderfully sweet “sauce.” By presenting the “yolk” in a familiar fashion (to be burst by the customer), the dish actually works to celebrate the way in which a mere egg may surpass its status as raw ingredient and become a major player in the character of a savory-sweet composition.

The preserved carrot, too, represents a new chapter in the Shieldses worship of “humble” produce. Listed without any accompanying flavors—and paired with a local Virginian late-harvest wine—the carrot (which has also appeared in a similar form at Smyth) testifies to a latent flavor that need only be unleashed. Often resigned to the role of mirepoix, the carrot—when nurtured—reveals a depth of sweetness, a candied character that can act as a pleasing dessert in its own right. The idea of preserving and serving something so simple—yet unleashing, in it, and unexpected power—strikes right at the core of how the chefs marry their technical know-how with the generous, loving eyes of forager and farmer.

When it comes to Karen’s pastry work, Riverstead’s menu reflects a greater creative presence throughout the course of the meal. The “corn sandy” and “sunchoke cannoli” showcase a bit of her talent at the very start of the meal, channeling cookie forms as a means of featuring natural ingredients. The vegetable sourdough and sprouted wheat biscuit, too, make for a dual sequence of traditional bread services with a slight twist in the composition of each dough. (The boudin noir paired with the latter, you think, lends the flaky biscuit an even greater opportunity to shine). Finally, rounding the corner into dessert, “embers of wintergreen branch & mint” allows for some of Karen’s whimsy to come to the fore, with the dish’s title alone striking more closely to a visual (rather than gustatory) scene. The kouign-amann, of course, returns guests to the playful start of the meal: the classic pastry is unquestionably nostalgic, highly comforting, and made the restaurant’s own via a garnish of foraged microgreens.

By April of 2015, the monthly dinners at Riverstead had come to an end. After more than half a decade plying their trade out east—and several years of jostling to make a place of their own in D.C.—the Shieldses, now with two daughters in tow, returned to Chicago. “We just kind of gave Chicago a chance, and, lo and behold, within one day of trying, we found a space,” John admitted to The Washington Post. “We gave it [opening in the Capital] a valiant effort,” he made clear, but reporter Becky Krystal said it best: “Sorry, Washington. Our loss is Chicago’s gain.”

According to Phil Vettel, the Tribune’s former dining critic, John and Karen had gotten a hot tip from fellow Charlie Trotter’s alumnus Bill Kim—whose BellyQ and Urbanbelly restaurants formed a longstanding presence at the western end of Randolph Restaurant Row. Kim pointed the couple towards a potential opening around the corner from him on Ada Street, a sprawling 5,600-square-foot space that belonged to chef Ryan Hutmacher. Hutmacher had been running the Centered Chef—a wellness and culinary consulting business—out of there, with the bulk of the area devoted to hosting catered private events. But now he wanted out, and, in the space (which comprised two separate floors), the Shieldses saw opportunity.

From the start, the couple viewed the “upstairs restaurant” as a continuation of their work at Town House and Riverstead in Chilhowie. The chefs imagined serving both an eight-course menu and a fourteen-course extended tasting in the space, a dichotomy that would up the ante from the four-course / nine-course options served during their time in Virginia. (The sample menu from Riverstead you cited topped out at fifteen courses, but those monthly affairs must be judged differently from a regularly-operating restaurant).

Downstairs, in contrast, was described as “a casual place, food and cocktails, very lounge-y atmosphere, at a price point that you’re going to want to come back more often than not.” The Shieldses aimed to have some connection between the two dining rooms—“we’re still working that out a little bit”—but embraced the chance at distinguishing them: “it’ll be fun to have them separate, to have one feeling downstairs, a different feeling upstairs.” John and Karen’s hope was for the pair of restaurants to open late in the fall of 2015.

In January of 2016, they unveiled the concepts’ names—Smyth, for the upstairs space, and The Loyalist, for downstairs—and they pinpointed a late-spring launch for both. Now deeper into Smyth’s design phase, Karen shared how they “really want to step away from the cliched fine-dining restaurant service that, to a lot of average folks, is nerve-wracking.” Rather, the two hoped guests would feel as though they were dining in the chefs’ home, striking a “genuine” “happy medium” between formal precision and casual comfort. At forty seats, the space would number just five more than Town House, a sign that the intimacy and charm the team built their reputation on would be well-preserved.

“Smyth,” itself, refers to Smyth County, Virginia—home to Chilhowie and the larger terrain from which the Shieldses foraged and sought inspiration for their menus at Town House and Riverstead. Rather than capturing a sense of place, you think, the reference to Smyth County underlines the preservation of the culinary philosophy which the chefs had honed out east. The name, in that sense, forms a thread through which Chicago becomes another chapter of their growth as artisans, rather than a venue for the prodigal son and daughter to settle down and “play the hits.” Similarly, the cuisine does not intend to transport diners to Virginia so much as it embraces a similar rhythm of life in Illinois. To that point, Karen revealed they’d be working with a “20-acre Illinois farm for much of their produce” who would “be growing exactly what we want.”

Finally, some four years after Town House formally closed, the Shieldses opened The Loyalist in late July of 2016. Smyth followed one month later, the culmination of a dream that took the chefs from Chicago to Virginia and back again. While the two concepts are indeed connected, this piece will concern itself solely with Smyth. (The Loyalist, you think, ranks as one of Chicago’s best restaurants in its own right and deserves careful consideration in its own article). Herein, however, it is worth considering that John and Karen built their fine dining program on the foundation of a community eatery with the express goal of cultivating a flow of weekly “regulars.” Such a nesting of concepts not only makes business sense, but it speaks to something essential about the couple. The Loyalist is not Roister—that is to say, a ham-fisted attempt at comfort food from a group concerned only with monetization. Rather, the Shieldses simply love to cook for people, to care for them, and the space below Smyth ensures the widest segment of society can experience some taste of their generous, soulful cuisine.

In recounting your experiences at Smyth, you will—as is typical—condense the sum of your dinners into one cohesive narrative that looks to capture the restaurant in a comprehensive fashion. Given the establishment’s uncommon connection to seasonality (on a micro, rather than a macro “four season” scale), you think this format will prove particularly rewarding. Further, while Smyth has hosted exceptional collaborative meals with SingleThread, the Willows Inn, and Somni over the years (the best that Chicago, in your opinion, has ever seen), you will defer discussing these events in the interest of painting a picture of the restaurant in its normal operation. With that settled, let us begin!

Ada Street—now that its aforementioned parking lot has been replaced with “The Mason” (a fourteen-story apartment building)—stands as one of Randolph Restaurant Row’s more congested offshoots. On the best days, motor traffic can just about proceed in both directions while keeping decapitated mirrors to a minimum. Most of the time, however, the “sardine can” parallel parking stretching down each side squeezes passing cars uncomfortably close together. This all amounts to a rather neighborly scene where the street operates with the patience of a shared driveway—rather than a city road. Drivers inch their way out, forward, and around with eagle eyes and delicate ears, ever-alert to the dreaded sound of metal scraping metal. Pedestrians disembark and weave their away around vehicles—the luckiest among them heading to the building marked 177.

During the pandemic, Ada Street has never been more dysfunctional. Northbound traffic is a sea of hazard signals as brown bags are shuffled into trunks and passenger seats with gleeful, knowing looks. The prospect of bypassing the stopped cars and reaching Lake Street is improbable. At peak hours, it is all but impossible. Yet patient motorists refrain from their horns and heckles. Yes, a sense of goodwill reigns on this block of Ada Street. It may be a ways away from the bright lights of the dining district’s dense, eastern outcrop (home to the Goats, to Au Cheval, the Alinea Group, and all manner of other delights). But, whereas those restaurants speak to the present, this block of Ada Street embodies the future of American gastronomy.

It is no coincidence that Elske set up shop around the corner, that Curtis Duffy chose to stage his comeback only one further block north. For this block of Ada Street is home to Chicago’s greatest (ever) restaurant, and the sense of reverence shown for the work that goes on there is obvious even through all the congestion the journey entails. You see, nobody just stumbles upon Smyth (though you have no doubt the staff would find room for such a traveler, upstairs or down). Sure, it’s not Chilhowie, but visiting the restaurant—where the Shieldses have, at last, set up shop—is a proper pilgrimage. Because Smyth resists the flash of fine dining public relations 101. The chefs do not debase their cuisine so as to make it more camera-friendly. The restaurant need not jostle with the business across the street for a few breadcrumbs of patronage. It merely is.

That is to say, Smyth is at home on its block: a workaday street in an industrial section of a broad-shouldered city still defined (though decreasingly so) by the meat-packing plants that once turned readers’ stomachs. (To wit, Peoria Packing still draws lines in a building located somewhere between Smyth and Ever). Yet, unlike Ever, entering Smyth does not entail entering a different world. Rather, one steps into a more perfect world, a particular expression of a familiar place rooted indelibly in the native soil. Yes, Smyth is Chicago. It is also Illinois, the Great Lakes, the Midwest, and America, itself, at its most sublime. Concurrent with this macroscopic “sense of place,” Smyth also comprises every individual soul to have ever donned an apron in its kitchen or dining room. In that microscopic sense, the restaurant is a pantheon of hospitality where discrete figures—no matter how major or minor the role played in one’s meal—take on a salience and emotional resonance one but rarely experiences in so-called “service encounters.” Smyth stands not simply as a “restaurant family” (to use a dangerously trite expression), but a living tapestry in which staff past, present, and future are joined in a spirit of collective excellence and singular, actualized self-expression. It immediately strikes the diner as something worlds away from what a “corporate culture” could ever formulate.

You exit your Uber and dash across the street to the curb, marveling at those ivy-covered walls which mark 177 N. Ada Street. The sign says Smyth | The Loyalist, but the butterflies in your stomach foretell that you will be making a trip to the former. You enter the building’s vestibule and note the staircase, on the left, the descends to The Loyalist. A smaller staircase—rising just above ground level—brings you face-to-face with the building’s residential entrance (oh, what lucky souls occupy those units!). But to the right of that, behind a heavy wooden door, the din of Smyth’s dining room is unmistakable. No, not in the sense that the restaurant is noisy. Rather, it bustles with the sounds of the staff’s dynamism, as well as the clinking glasses and cackling laughs that denote the good time being had by all and sundry.

You enter the dining room and imbibe the palpable energy of proceedings: cooks engaged in careful toil; tables, booths, and banquettes filled with well-dressed and rosy-cheeked patrons; aproned and suited front of house staff scurrying about—and always ensuring each dish, each drink arrives two-at-a-time in perfect synchronization. There’s a plush little lounge situated immediately to your right. A butler’s pantry featuring glassware, that evening’s wine pairings, and other tools of the trade curls around the corner to your left and extends—with a small gap—into the pass. That counter, the crown jewel of one of the most truly “open” kitchens you have ever witnessed, frames the entirety of the space. Its intimacy and accessibility—to say nothing of the faultless organization and flow of the back-of-house team within its confines—are something special. One gets none of that foreboding feeling the “great” kitchens of the world can inspire. Instead, you are struck with the sense of being in someone’s home, a family home where onlookers’ peering and probing form a natural part of the process—and might even be rewarded by generous cooks. (You think Town House and Riverstead must have been similar: establishments where boundaries between the “cooking” and the “hospitality” dissolved completely in a manner one only commonly experiences in private residences).

While there is nothing particularly “showy” about what goes on in Smyth’s kitchen—though, you must say, the crackling wood fire festooned with hanging squab carcasses is rather pleasing to watch—it is no surprise that every seat in the house is ensured some view of the action. Nothing screams for the guest’s attention, nothing demands they take note (or take pictures). Yes, there’s a richness to be gained from watching the cooks work, but you can just as easily simply taste the fruits of their labor and savor a meal defined more by your companions’ conversation or the nature of the wine being served. Remember, Smyth simply is. The restaurant contains untold magic, endless detail of the sort that never imposes but, rather, stands ready for just the right moment one cares to pay it mind. This, truly, is the essence of hospitality: an embracing and displaying of what is genuine at every given moment, opening the doors to guests’ fullest enjoyment of the experience without the least bit of prodding in one direction or another. Smyth does not try to impress but, instead, is fully absorbed in being. In that, it invites you to grapple with the environment on your own terms and find a place that is truly comfortable, truly yours in the annals of its seasonal storytelling.

Down the pass, after a small gap, stands the pastry kitchen, which occupies one of the room’s corners in much the same way as the butler’s pantry immediately to your side. Everything opposite these three zones (butler’s pantry, kitchen, pastry kitchen) is the dining room, with the closest tables situated only a few feet from the action. There are two-tops, four-tops, six-tops and two corner booths that can accommodate five comfortably. Each is made from a medium brown wood—no white tablecloth here—and matched with sturdy armchairs featuring the same wood and dark leather cushions.

You would call the style of the room “country minimalism,” for it does not indulge in any of the tacky accents that have come to define “industrial” chic. Rather, wood is paired with wood—with tannish-brown beams and matching, exposed ceiling playing off the tones of the furniture. Those beams, of course, are original to the building (and some of the only artifacts that remain from what was the Centered Chef space). Same goes for the brick walls. The kitchen counters are finished in a darker shade of wood, with a bit of textural variation to add intrigue. Metal finishes are kept where they belong: appliances, countertops, hanging lamps, and window settings. They add character without stealing the show (or devolving into that dreaded aforementioned industrialism).

Smyth’s principal accents come from an assortment of glass throughout the room—not just water glasses on tables or wine glasses neatly arranged on shelves, but glass lamps, hanging light fixtures, and decanters (which add character to the tabletop that separates the lounge space from the dining room proper). That tabletop is also home to a record player, which staff members will take turns manning throughout the evening. They pick from an assortment of eclectic, donated vinyls that are piped through the restaurant’s speaker system with aplomb. (On other occasions, the speaker system will emit a digital playlist, making the record player’s operation a particular treat when one sees it).

All that glass is enlivened by the towering windows that face Ada Street. The natural light—which is expertly managed by the staff through sundown using shades—later yields to candlelight, which works just as well to accent the accents. The one other accent of note extends out from the bottom of the pass. It’s a faded, reddish rug that melds into the range of browns featured in the space and further serves to frame the kitchen (relative to the dining room). Guests venturing to the bathrooms located just behind the kitchen are treated to two different sets of “accent” wallpaper, along with a selection of John and Karen’s most treasured menus from meals at Trio, Charlie Trotter’s, La Maison Troisgrois, and El Bulli, to name a few. These are playful touches that prompt pause, perhaps even a smile, when guests excuse themselves. And they also serve to highlight the restraint shown elsewhere.

For Smyth’s interior design—like every part of the experience—is imbued with some piece of the Shieldses’ soul. Eminently warm and welcoming, the dining conjures feelings of luxury without bowing before any of its tropes. The chairs are sturdy and comfortable without having to compete with Grace’s $1,000 price tag. The kitchen—despite the chefs’ mastery of molecular gastronomy techniques—operates in a familiar fashion without clouds of liquid nitrogen or other fancy contraptions begging for attention. The materials throughout the space are humble, which is to say genuine. They do not intimidate, but rather envelop the patron with their timelessness. None of the individual elements may be auspicious, yet the myriad details lend the sensation of a curated space meant to be discovered, in due time, over the course of countless visits. Smyth’s space is characterized less by any anchoring element than how it makes one feel—which is to say, “at home.”

Immediately upon entering the restaurant, Smyth’s hostess swoops besides you, bids you welcome, and offers to collect coats and other luggage. The table, she says, is ready—though on other occasions you have enjoyed a welcome drink in the lounge with great relish. Following the hostess, your party walks across the rug which underlines the pass and steals a quick greeting from the chefs (executive and de cuisine) that are hard at work. She leads you to the booth in the far corner of the restaurant—diagonal from the entrance and opposite the pastry kitchen. Three members of the group scoot themselves into position around the cushion while the two remaining—yourself included—hesitate but a moment. With perfect synchronization, the two armchairs facing the booth are pulled back and pushed forward as you both take your seats. The hostess wishes the table a pleasant dinner and, moments later, white wine glasses hit the table.

Smyth’s sommelier is as sharp as they come and, all the more, the most personable in Chicago fine dining. When he fails to greet you himself at the door, you can be entirely sure he’ll stand ready to pounce the moment you are seated. Of course, he always comes bearing gifts: a welcome glass of Champagne from Bruno Paillard, Charles Heidsieck, Paul Bara, or Dom Ruinart. On many a magical evening, the first sip that whet your whistle was even Krug “Grande Cuvée”—not a bad welcome tipple! After a warm exchange of pleasantries, the sommelier gets down to brass tacks: what will you be drinking this evening?

This conversational style of wine service works wonders, as Smyth’s sommelier possesses none of the imposing bearing that characterizes the profession, particularly in rarefied dining rooms boasting Michelin stars and Wine Spectator awards. In fact, the word “lovable scamp” comes to mind. But this is not to say that the man isn’t a total wine geek—he has the “GG” (a designation for exceptional wines etched onto bottles in Germany) tattoo to prove it! While Smyth does offer three tiers of wine pairings, there is not the slightest effort made to shoehorn guests into one of those boxes (à la Alinea or, especially, Next). For a typical meal at the restaurant (that is to say, for the middle-priced menu that is neither an abbreviated nor extended tasting), a “Traditional” pairing is offered at $90, a “Reserve” at $165, and a “Super Mega” at $255. Such a sliding scale is not only generous, but it avoids manipulative language like “standard” (instead of “traditional”) or “ultra” (instead of “super mega”) which serve to turn the emotional screws on guests already indulging in a special experience.

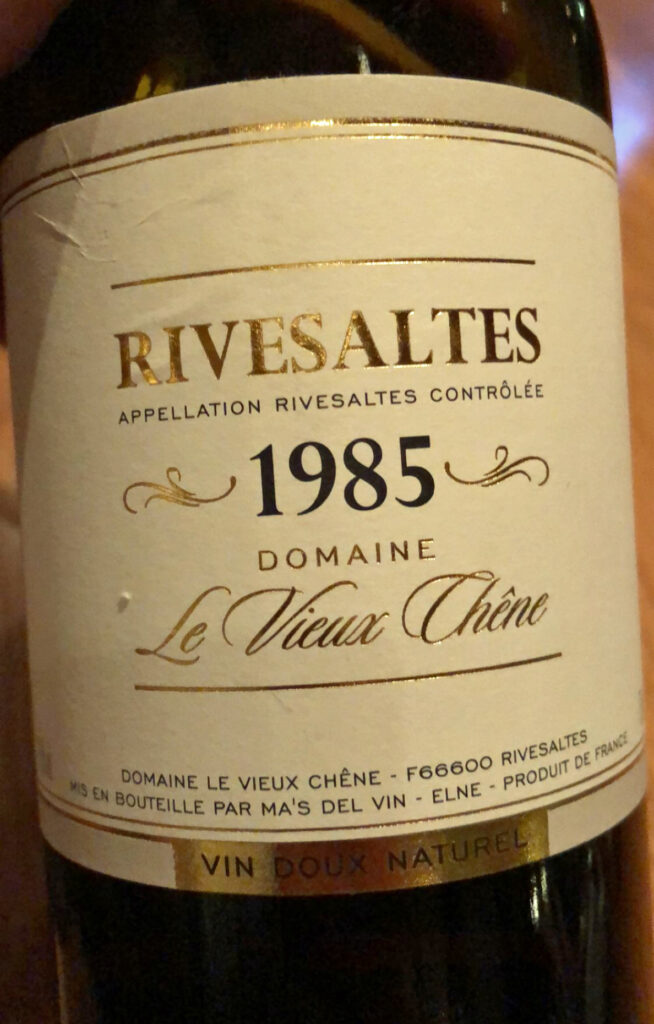

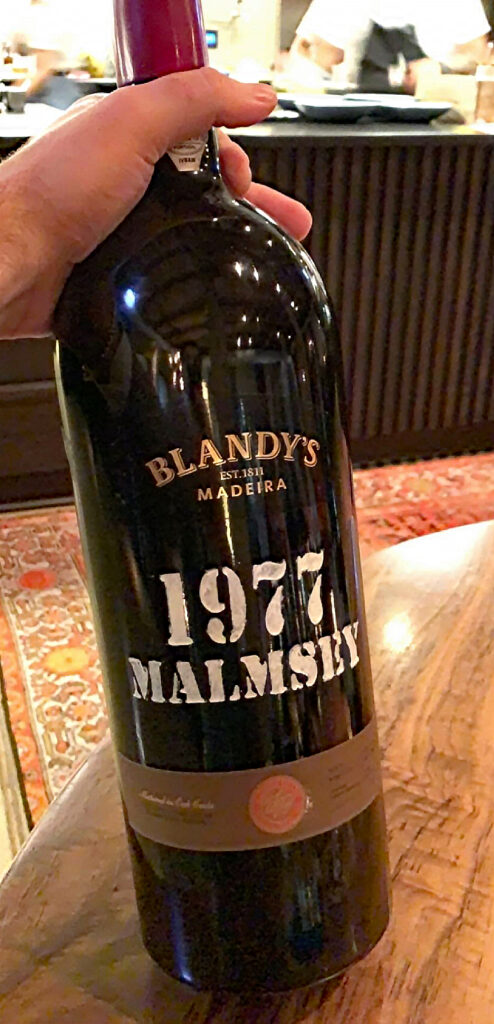

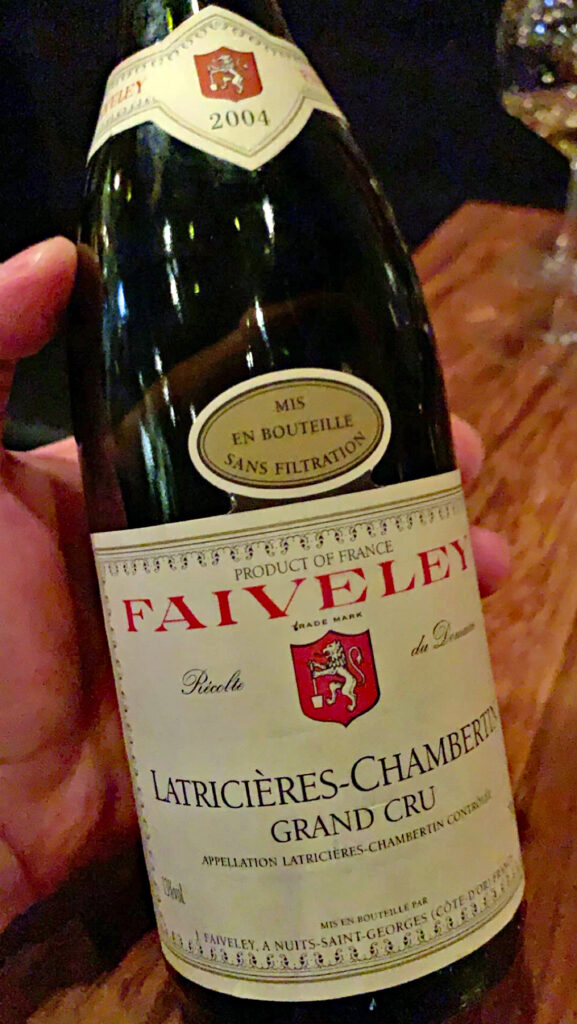

These pairings—which may include beer and sake with certain courses—are principally devoted to wine. However, in line with a hyper-seasonal menu which may change from week to week, the offerings are anything but cookie-cutter. The number of pairings sold, either in advance or on the spot throughout the evening, empower Smyth’s sommelier to open wines of greater age and pedigree. Thus, on evenings when other patrons are particularly thirsty for top-tier wine, the “Reserve” and “Super Mega” pairings may include Clos des Goisses, Keller Riesling, Premier Cru Ramonet, Jamet Côte Rôtie, or Sandrone Barolo with a decade or two of age. Dessert is almost certain to feature Port, Madeira, or Rivesaltes with many decades of age. In this manner, customers’ enjoyment of wine during the meal has a cumulative effect, increasing pleasure for all parties involved (rather than serving merely to pad the establishment’s pockets). The pairings have always struck you with their generosity and the singular nature of their curation. Yes, some wines and some dishes form longstanding companions; however, the overall sensation is one of celebrating wine, in the moment, with none of the parsimony that, at other fine dining restaurants, reduces it to mere “beverage.”

With that in mind, Smyth’s sommelier is always sure to alert you to a particularly good wine pairing which has taken shape that evening. On other occasions, ordering a round of “Super Mega” pairings for the table will prompt him to put something together—in line with your tastes—on the spot.

Those opting to order beverages à la carte will find themselves spoilt for choice. To start, the leather book features a range of libations made from the bar cart situated at the front of the restaurant’s lounge. Offerings like the “Smyth Manhattan” (with black trumpet bitters) and “Smyth Milk Punch” (with sweet corn) incorporate a taste of The Farm into their classic recipes. Likewise, Smyth’s non-alcoholic offerings—which can be expanded into a pairing that extends over the course of the meal—draw on the same pantry of fresh and preserved seasonal ingredients. (Not to mention, these non-alcoholic selections are actually designed by the restaurant’s head chef, which would seem to make them a kindred expression of the tasting menu and not a mere afterthought).

Three local beers (from Indiana, Illinois, and Michigan) are offered at seven dollars each. Two fancy brews (from France and Japan) will both run you thirteen. And, while the cocktails and beer are more carefully curated on Smyth’s menu, the staff hasn’t the slightest problem sneaking downstairs to The Loyalist and delivering any number of more standard brands and mixed creations from the full bar below. The ultimate goal being, of course, pleasing the customer any way they can (while also being sure to display the more unique wares that distinguish the fine dining space from its subterranean “brother”).

As well-attuned as the wine pairings are to the tasting menu, one can hardly go wrong ordering from the bottle list. You would urge guests to peruse the selections one way or another, as Smyth’s cellar has—over the course of but a few years—become one of Chicago’s most estimable (outshining Alinea, Boka, and Oriole in its selections while competing with Maple & Ash, if not in breadth than in pricing). By the glass selections have included non-vintage sparkling wines (priced from $15 to $30), white wines like Keller’s “Von der Fels” and Lafon’s Macon (priced around $20), and red wines made from Gamay, Nebbiolo, Pinot Noir, and Cabernet Sauvignon (priced from $17 to $27). You applaud the restaurant for ignoring Coravin offerings in favor of accessible, representative wines from great regions that possess at least a few years of age. Those ordering a mere glass or two of wine will, no doubt, miss out on some of the list’s riches, but they can hardly be disappointed with what they get for the price.

Those turning the page to look at the bottles will quickly find their tongues wagging. Most Champagne (including non-vintage and millésimes like 2011, 2009, 2007, and 2004) falls in the $100-$200 range. Smyth is partial to larger houses like Billecart-Salmon, Ruinart, and Laurent-Perrier alongside grower-producers such as Bruno Paillard, Paul Bara, J.L. Vergnon, and José Dhondt. The Chardonnay section is marked by premier cru and grand cru Burgundy from producers like Robin, Gagnard, Pernot, and Fichet. The list, over the past year, has also seen a greater influx of Lafon’s top cuvées (rarely seen anywhere in the city). Domestic offerings of the grape—from Lingua Franca, Rhys, and Hudson, among others—offers even greater value. But, apart from the very best selections, customers can get any number of great Chardonnays (with a healthy bit of aging) for less than $200. And oddballs like Emmanuel Rouget’s 2014 Hautes-Côtes de Beaune Blanc, priced at $100, are an absolute steal.

Keller’s Rieslings—particularly the full range of GG sites and even the G-Max itself—have been mainstays of the wine list’s section on the grape. Buying allocations since opening has enabled Smyth to offer more competitive pricing on the coveted bottles than seen elsewhere. Other great German producers such as Reichsgraf von Kesselstatt, Alfred Merkelbach, and Schäfer-Fröhlich are featured at a comparatively cut-rate price, as are Austrian Rieslings by Weingut Knoll and F.X. Pichler. Sauvignon Blanc, it must be said, suffers by being one of the less exciting sections of the list. The half dozen bottles offered at under $100 are laudable (including a 2014 Cos d’Estournel Blanc) if not exactly distinguished. Legendary Loire producers like Dagueneau and Vatan have indeed featured on the restaurant’s set pairings, so perhaps their absence on the list is a matter of limited allocations (which should, you agree, be directed towards usage on those pairings).

Chenin Blanc, however, is another of the list’s bright spots. Like Keller, Domaine Guiberteau has been collected by the restaurant since opening, meaning that the producer’s selection of superb Saumur Blanc is available for a song. (The same is true for Guiberteau’s Saumur Rouge wines made from Cabernet Franc). Speaking of red wine, Smyth’s Pinot Noir section is structured in much the same way as its Chardonnay. There are village bottles of Burgundy (from producers like Dujac and Dugat) at sub-$200 prices with premier and grand cru bottles (also from Dujac, as well as Denis Mortet) climbing up the scale. Opposite these, domestic expressions of the grape from Peay and Littorai (the latter from five different vineyards) provide plenty of options at $150-$200 along with the odd Spätburgunder from Germany.

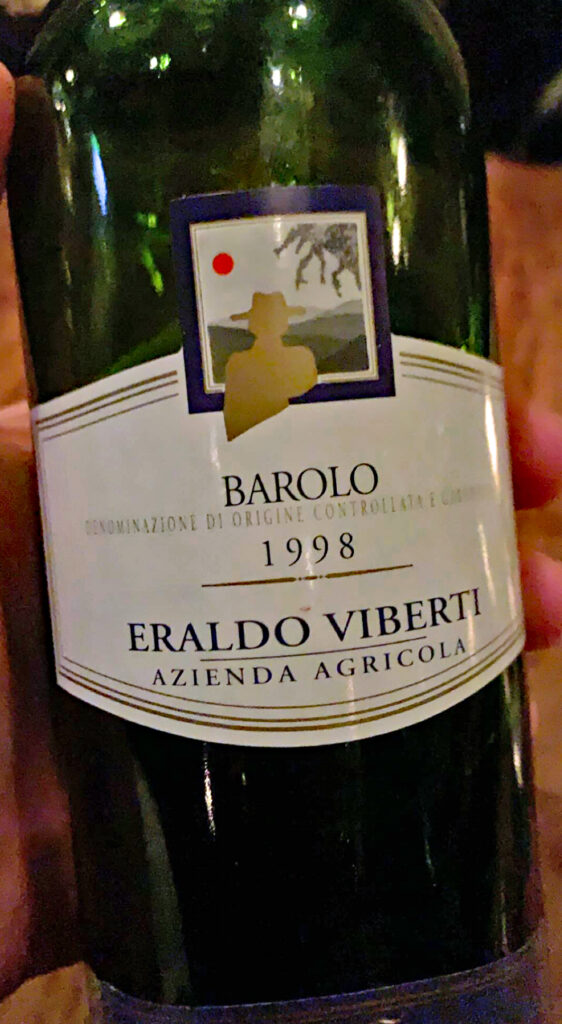

Gamay, Grenache, Syrah, Merlot, and Tempranillo (including several vintages of Vega-Sicilia’s “Unico”) are all represented on the list, in turn, with a handful of bottles. “Cabernet Sauvignon + Bordeaux” forms one of the lengthier sections, offering hallowed names such as Ornellaia, Château Palmer, and Abreu (among plenty of reliable options under $200). The Nebbiolo section is a bit shorter, yet significant, with wines by G.D. Vajra, Eraldo Viberti, Sandrone, and back-vintage Borgogno leading the charge. Dessert wines, offered by the bottle or by the glass, include white Bordeaux blends, late-harvest Chenin Blanc, Rivesaltes, Tokaji, and Port. (The restaurant has always been especially generous with these pours, which allow Urie Shields to craft desserts that offer a meaningful interplay with certain pairings).

While any attempt to represent Smyth’s wine list in this manner amounts to a snapshot, you must say that you have been impressed most of all by the program’s growth over the course of time you have patronized the establishment. What was always an exciting list—replete with hidden gems and untold value—has, under the stewardship of a new wine director brought on from Alinea, transformed into one of Chicago’s most compelling selections. The restaurant’s list does not only sustain First Growth Bordeaux, Harlan, Rayas, Rousseau, and the like—all with age—but it offers those premium wines at an attainable price. Though bottles in the $100-$200 range have long been a strong suit, each section of the list has been fleshed out (both above and below that pricing). Such development signals that Smyth is interested in the “long haul,” and, given the restaurant’s prescience with regards to producers, wine lovers will have more and more to look forward to in the years ahead. Further, given the manner in which wine pairings are constructed night to night, even amateur winos can expect to benefit from the great work being done.

Beverages being settled, the welcome toast of Champagne having frothed refreshingly against your lips, the meal may, at last, begin. The opening interlude of bites, which has featured as few as two and as many as four or five amuse-bouches throughout your visits, reliably contains two of Smyth’s signature creations. The first, a few pale white slivers of black walnut, sit atop a bowl of the discarded shells. They taste, it must be said, like you would expect. Yet they also tell a story: black walnuts were the first ingredient the Shieldses sourced from The Farm, and the presentation (which once upon a time arrived at the table with a small book filled with pictures of the purveyor’s holdings) serves to underline the cuisine’s connection to that land. Indeed, black walnuts have been used more creatively in other dishes throughout the menu, but, here, the form a fitting foundation, centering the experience to come.

Another classic opening bite, served even more invariably than the walnuts, is Smyth’s so-called “sea lettuce cookie.” Each rendition of the cookie starts with the same base: a super crumbly biscuit strewn with powdered seaweed. Atop this thin cookie sits a dollop of cream. Sometimes the cream is milky white. On other occasions, it has taken on a green hue that matches the shades seen in the biscuit. No matter the color, the cream serves to moisten the tongue as it contends with the drying effect from the crumbly base of the bite, lending it a slightly sour—yet still vegetal—note.

Crowning each cookie is the titular “sea lettuce” (a catchall term for the seaweed and edible algae that lines the coasts of the world’s oceans). On any given evening, the exact species of lettuce topping your cookie could be different: members of the genus might taste the same, but they take on myriad shapes and sizes. Added to this bouquet are all sorts of edible flowers and fresh herbs from The Farm, an ever-rotating assemblage in and of itself (that makes for a lovely “land meets sea” effect). On one occasion, the cookie arrived topped with a thin twirl of salmon sashimi. On another, the term “cookie” was replaced by “voulevant,” a reference to Carême’s vol-au-vent puff pastries (and a term that surely was in use at TRU or Charlie Trotter’s). You have even seen the cookie discarded altogether from the bite before, the result being something akin to a seaweed “taco” set inside a giant leaf.

Whatever the exact form it takes, the “sea lettuce cookie” stands as one of the ultimate testaments to Smyth’s ethos. Yes, the bite is easy to overlook at first. It’s tasty—combining the umami of the crumbly seaweed cracker with the sourness of the cream, the freshness of the greens, and the essence of the ocean—and it’s extraordinary when paired with Champagne. But it’s also gone in an instant and quickly overshadowed by the many dishes to come.

However, over the course of repeat visits to the restaurant, that cookie becomes something of a totem. It’s always there and, yet, slightly different. The parts are tinkered with, the form changes here or there, but the essence is the same. The effect is the same, titillating the palate with the algae’s gentle caress. Though its place in the meal is relatively minor, the restaurant builds each “sea lettuce cookie” fancifully, organically as if it were the very first time it was served. The bite is perpetually changing, just as all of Smyth’s cuisine is, but never loses sight of its unwavering goal: excellence.

Every time a diner comes face to face with that familiar morsel, they are reminded that, here, the details really do matter. Nature does not allow her treasures to be frozen in time forever. One can never hope to perpetually hold her bounty in a set “form,” no matter how exacting. Rather, the bite reminds us that Smyth is a living, breathing restaurant wherein one tastes not only the season, but the moment. This moment, expressed through this “sea lettuce cookie,” that will never be the same again. Not a bad bit of romance for a bite that amounts to “bycatch.”

Other amuse-bouches, served alongside (or in place of) the walnuts and the seaweed cookie, have embraced this hyper-seasonal perspective all the more. They have included a small bowl of pitted cherries with sliced olives in olive oil, halved black mission figs glazed with a blue cheese “syrup,” raw asparagus paired with raw oyster, and a “fruit platter” filled with two types of cherries and some picturesque green almond slices (all poked and eaten with skewers). As seen throughout the Shieldses’ time at Town House, the name of the game with these bites is the worship of raw ingredients.

Whereas other restaurants imbue their opening morsels with a high demonstration of technique—so as to impart as much flavor as possible into a diminutive form—Smyth’s amuse-bouches are all about subtlety. This is no place where buzzwords like “truffle,” “foie gras,” or “caviar” are trotted out at the start to shock and awe skeptical customers. Rather, the restaurant offers guests a humble selection from the natural bounty that forms the lifeblood of the entire enterprise. A piece of fruit, a nut, a stalk of asparagus—these are hardly the harbingers of a two Michelin star “luxury” meal. Yet they speak to the foundation that good sourcing forms at Smyth.

The bites assert the quality of that evening’s ingredients with supreme confidence, making clear that most of what the kitchen serves demands little transformation or ornamentation to taste good. Instead, a chef sometimes needs to know when to move “out of the way” and merely play the part of the wingman for whatever nature has, herself, designed. Surely, the subsequent dishes will be a great deal more complex. But patrons start dinner by being primed to appreciate “less” instead of “more.” Not “less” flavor, mind you, but the sort of deep flavor that finds its expression more in field and ferment than fancy presentation. It’s the sort of flavor that, shirking the trappings and expectations that have come to define high gastronomy, begs to be discovered and inevitably blows you away.

The opening sequence having passed, dinner proper typically begins with a couple preparations of seafood. Of these, oysters have formed one of the cornerstones. They are served raw, usually on the half shell, and have been dressed with garnishes such as green gooseberries & dulse; tomato & fish roe; dulse, apple, & spruce; radish & strawberry; and salted plum. The oysters also often find themselves festooned with the same sort of seaweed used in the amuse-bouche cookie, a minor accompanying note that, nonetheless, forms a nice linkage between courses.

Smyth has been partial to serving Beausoleil oysters from New Brunswick, Canada—a small variety known for its mild brine and bright, clean flavor characterized by cucumber and green melon. When served within its own shell, the restaurant reduces the aforementioned garnishes into syrups and slivers that can be easily slurped in one fell swoop. On other occasions, the oyster is removed from shell—its brine carefully retained—and placed at the bottom of a bowl. It may even be gently smoked before reaching this resting place. In either case, the accompanying fruit garnishes take on the form of cold broths or, better yet, frozen slush. More textural components like the dulse or fish roe are given greater room to dot the plate.

No matter the exact form (which perpetually changes), Smyth’s oyster preparations have long succeeded in using the bivalve as a canvas for produce both preserved and fresh. A good mignonette is, of course, a marvel, and The Loyalist has appended a fine example to the seafood towers served downstairs. But the range of garnishes used upstairs move beyond mere acidity and the tang of sourness. The gooseberries, strawberries, apples, and even the tomato and plum, in turn, provide genuine sweetness (to say nothing of their own tartness) that partners wonderfully with the Beausoleil’s latent melon notes. Opposite this, ingredients like radish may provide a contrasting sharpness while those such as fish roe and dulse amplify flavors of the sea. But the textures, processed down into sauce or slush so as not to overshadow the delicate oyster, are totally unerring. One savors those few seconds in which the bivalve dances on the tongue before diving back into the bowl to drain every drop of its dressing. In this fashion, the “raw oyster” comes close to a highly refined ceviche with a leche de tigre that looks beyond citrus to embrace a pleasing range of other fruit flavors.

Also typically served at the start of the meal, sea urchin roe (or uni) has proven to be yet another pristine ingredient from which Smyth has coaxed out almost an unparalleled depth and intensity of flavor. On some occasions, it forms a fitting bedfellow for the oyster preparation, adding yet another delicate texture to discover within the slush of salted radish, apple, and tomato that coats the bowl.

Yet the sea urchin—typically sourced from Maine—really shines when given its own starring role—like being placed upon a puff of fried sourdough and glazed with The Farm’s own maple sap. This creation, which Shields referred to colloquially as an “uni funnel cake,” formed one of the restaurant’s most playful and creative bites over the course of several visits in 2018.

First, the warm sourdough would melt on the tongue, coating the palate in such a way that the sea urchin itself transformed into a custard with the chews that followed. Both textures would mingle, releasing the full breadth of the uni’s smooth, supple consistency and infusing it into the sourdough so as to amplify its mouthfeel. The subtle sour flavor of the dough would work to accent the sea urchin’s latent notes of sweetness and sea. Then, as a final flourish, the glaze of maple sap would extend and underline that sweetness. The end result unmistakably reminded you of “funnel cake” without compromising in its showcasing of the uni (an ingredient that may easily be overshadowed by a heavy hand). Such a dish, undoubtedly, speaks to the chef’s ability to bring luxury totems down to earth in a way that charms amateurs and aficionados alike.

As time went on, however, Smyth transitioned its sea urchin preparation into something simpler and more pristine. Ditching the sourdough, as well as the maple glaze, the restaurant took to serving the uni—just as the oyster before it—at the bottom of a shallow bowl. There, it would receive a more restrained glaze—made solely from egg yolk—and served as is.

The effect of the egg, in this case, is threefold. Visually, its glistening yellow color lends the sea urchin an attractive finish, doing well to frame the ingredient’s own unmistakable orange hue. Thematically, the egg yolk grounds the uni within the world of The Farm and the Shieldses own style (eggs being, both at Town House and at Smyth, something of a signature). Further, given that sea urchin is often reserved for sashimi or nigiri preparations, the light touch of the egg yolk aligns with (and plays off of) a certain minimalist Japanese sensibility regarding the ingredient. Finally, the egg yolk possess a perfect neutral sort of richness that furthers the uni’s unctuous texture and custardy, slightly sweet flavor. (Later renditions of this dish have received a garnish of habanada peppers—a natural mutation of the habanero that lacks heat—lending additional, enjoyable melon notes to the equation while incorporating more of The Farm’s crop).

More recently, you have even seen sea urchin feature towards the midpoint of the menu—right on the precipice of the transition from seafood to meat. The dish in question, one of the most striking you have seen at the restaurant, features three picture perfect lobes uni placed around the plate. Each is paired with a slice of “soured” oyster mushroom and neatly cut circle of braised kelp. The end result is something like a surrealist painting (note how the stalk of one mushroom invites the illusion that the uni forms its “cap”). And it is, perhaps, Smyth’s most elegant of all sea urchin preparations to date. The oyster mushrooms imparting that rare combination of sour and umami while the braised kelp lends both more umami and a sea-vegetal note.

Following the oyster and the uni, Smyth’s menu might take one of several turns. The kitchen may interrupt the array of seafood with a pure expression of produce, such as fava beans (with buttermilk whey, spring onions, and chamomile), caramelized eggplant sorbet (with tomato and spices), squash (with sunflower and togarashi), a chilled soup (of tomatoes, eggplant, and peppers), a salad of late summer fruit (“nature’s skittles”), a solitary stalk of barbecued white asparagus, a turnip “ceviche,” or a carrot “aguachile.”

Relative to the delicacy which defines the meal’s opening courses, these vegetable- and fruit-forward creations excel in offering robust, layered expressions of complementary flavors. Some—like the fava beans, squash, and white asparagus—express rich, buttery notes. Others—like the eggplant, soup, ceviche, and aguachile—marry acid, tang, and sweetness into a jolting medley. Whatever the case, these dishes reorient guests’ attention—having, by now, enjoyed some luxury shellfish—towards the produce’s role as the “main player” in the proceedings to come. They also, by way of their intensity of flavor, make clear that balancing other ingredients (like seafood) actually serves to reign in the extraordinary flavors The Farm’s cultivars can offer alone.

But that is not to say that guests have seen the last of seafood on the menu. Instead of fruit or vegetables, the oyster and uni might be followed by a preparation of spot prawn. As best as you can tell, the spot prawn is removed from its shell and served raw—a testament to the freshness and quality of the shellfish. Rather than the plump, juicy texture for which cooked shrimp are known, this “sashimi”-style serving displays a softer, slightly gelatinous mouthfeel. Whereas the bivalves served before it (comprising just one or two bites each) are also characterized by softness of texture, the shrimp still offers patrons a greater sense of “flesh” and chew as they slice it into three or four separate morsels.

Moreover, the presentation of the spot prawn dish is utterly genius. Marinated (in fish sauce, you think) roses line the shrimp from the carapace down to its abdominal segments, forming a sort of faux shell. The prawn’s legs—which have been removed and discarded—are replicated by strands of green almond jutting out from its side. Meanwhile, the whole dish sits in a puddle of one of Shields’s signature sour/lactic sauces. In that familiar manner (which, across so many seafood dishes, can only be called masterful), the sauce amplifies the shrimp’s sweetness through contrasting notes that avoid overshadowing any sense of its pristine, raw qualities.

This same light touch with regards to raw seafood—be it oyster, sea urchin, or spot prawn—reaches its pinnacle when Shields works with caviar. It’s no surprise, given that few ingredients epitomize delicacy like those briny, nutty orbs of sturgeon roe. And yet, as you have described before, few ingredients are also wielded as wastefully. Caviar, being a hyperreal symbol of “fine dining,” a totemic luxury item par excellence, seduces chefs into thinking they need not really do anything with it. Just give guests their prized ration of roe and something to smear it on, the thought process goes, then sit back and lap up the praise. Shields, it is no surprise, sees things otherwise. Despite Smyth’s relative youth as a restaurant, his vision is clear, and no ingredient is so precious as to escape his stylistic stamp.

One signature caviar preparation has seen the ingredient—typically Kaluga (a sustainable “River Beluga”) caviar—paired with cantaloupe and almond milk. The fruit, depending on the iteration, is either sliced to an almost transparent thinness or shaved into a glistening, pulpy mound. Both transformations serve to soften the melon, removing any need to chew and, instead, allowing the ingredient to nestle the roe without obscuring its bursting on the tongue. The fruit’s sweetness, of course, plays off of the caviar’s saline quality and enables its nutty notes to shine. Likewise, the almond milk—in the style of those “lactic sauces”—undergirds the dish with additional sweetness, nuttiness, and a hint of sour. Married together, the components reveal in the caviar a greater depth of flavor through a layered shading of complementary flavors.

Another caviar preparation has seen the Kaluga placed atop a drizzle of chicken fat jus and nestled against a quenelle of crème fraîche. The dish is served with a pancake made from kōji—a mold that naturally grows on rice grains, forming sugars that play an essential role in fermenting both sake and miso. The kōji-coated grains can also be processed into a rice flour, with the mold displaying sweet aromas that have reminded some chefs of fresh scallops. For the purposes of this dish, the kōji lends the pancake a tinge of sweetness and umami that matches the chicken fat jus it inevitably soaks up. Both elements, of course, serve to enrich the caviar’s mouthfeel and buttery notes—with the crème fraîche coming through to provide the palate with a bit of reprieve.

The third (and most recent) example of Smyth’s caviar expertise combines elements from the prior two dishes. The Kaluga, instead of chicken fat jus, is paired with a jus made from guinea hen. Instead of a pancake made from kōji, guests are served one made from plain brioche. However, rather than cantaloupe, the caviar is strewn with thin slices of marinated beets and a hint of horseradish. Thus, rather than just sweet and sour, the Kaluga’s accompanying flavors are earthy and even a little “hot” to boot. The end result is more multifaceted than the caviar course’s other iterations but still characterized by restraint. With fat, earth, sweet, sour, and “heat” all in play, the roe is given ample room to express itself fully.

Though each service of seafood at Smyth seems to outdo the last, you have not yet reached the sequence of fish dishes upon which the restaurant has really built its reputation. This sequence is not so much about storytelling or referencing The Farm but, rather, presents an exploration of a singular fish in all its glory. Shima-aji, also known as striped jack, is the name of the game. The fish is found in warm waters throughout the Atlantic, Mediterranean, and Pacific Oceans but is extensively farmed in the waters to the south of Japan, where it commands a high price at local markets. Shima-aji is characterized by bluish green scales, light-colored flesh, and a fatty, oily texture with mild flavor that is reminiscent of fatty tuna. The ingredient, unsurprisingly, is a mainstay within sushi restaurants (where it is regarded, you think, in a high stratum of offerings alongside hamachi but bellow tuna).

Smyth’s embrace of the fish’s Japanese name implies a sourcing from those waters and an embrace of the cuisine’s sensibility. Over the course of a couple years, you have seen the restaurant’s shima-aji sequence grow from two titillating dishes, to three, and then finally four. In whatever form, patrons reliably single out at least one of the preparations as among their favorites from the entire meal.

Typically, the sequence begins with something akin to sashimi. The shima-aji is cured in nuka, also known as rice bran. The bran is a byproduct of the process in which brown rice is milled into white rice, with that remaining exodermis forming an excellent “pickling bed” once mixed with salt and water and allowed to ferment. This technique, of course, reminds you of Shields’s use of kōji in the earlier pancake preparations. Here, however, curing the shima-aji in nuka imparts the same added complexity and softness edomae sushi chefs aim for when aging the fish for one or two days before serving it. (As mentioned before, farmed shima-aji’s graces are largely textural, with younger Japanese finding the rare, traditional wild-caught variety to be too mild-tasting to be worth the price).

After being cured, Shields slices the fish into slivers and places two of them, per guest, in a shallow bowl. Then, they are garnished with pine cones (pulverized into a powder) and served. On occasion, the dish will see a few drops of fish sauce, some edible flowers, or even those familiar sea lettuces added as a further accent. Yet there is no question that the shima-aji is the star. The fish maintains the slightest bit of “chew” before yielding onto the tongue and coating it with an oily, all-encompassing texture. Its flavor is slightly sweet, slightly sour (due to the curing), and complicated by the dusting of pine cones that adds a sharp, green note. The end result ensures that the shima-aji’s fattiness stands front and center before disappearing with a lip-smacking twang.

Recent renditions of this dish have seen portions cut from the cured fish’s belly and served without any sort of garnish. Titled “shima on steroids,” these prime pieces are an even purer expression of the shima-aji’s fatty texture, flavored only with the sour and umami notes of the nuka. Surely, Chicago’s sushi chefs could learn a thing or two from Shields’s sashimi preparations (and they have even admitted as much!)

The second dish in the shima-aji sequence—which, originally, formed a longstanding duo with the “sashimi”—presents a masterful utilization of a part of the fish that is typically discarded. And, while the Shieldses take on barbecue beef brisket has been all the rage throughout the pandemic, it must be said that John first made his name grilling these fish ribs.

The portion served at Smyth is taken from the many thin bones that jut out along the shima-aji’s vertebrae. Between each of those bones, which are about the size of toothpicks, sits a deposit of succulent flesh. However, due to their relatively small size, the ribs would typically be overlooked in favor of preparing the fillet for customers. They’re not exactly big enough to make a meal out of (but, upon tasting Smyth’s expression, you sure would like to try!)

The chef grills the shima-aji ribs over juniper. This not only allows them to develop an attractive black char, but the smoke from the conifer imparts notes of balsamic and fresh wood. The ribs reach the table glistening atop squares of butcher paper. Guests are instructed to hold the ends of two of the bones as they drag the flesh cleanly onto their tongues. The end result begins with the sweet, caramelized notes of the shima-aji’s crust before advancing into subtle flavors of smoked fish. The fish’s texture, other than that crust’s slight resistance, is altogether luscious. It combines the natural fattiness found in the shima-aji’s sashimi preparation with a juiciness developed from grilling it “on the bone.”

With such a supreme mouthfeel on display, is it any surprise that—for the longest time—Smyth’s Kaluga caviar found its way on top of the shima-aji ribs as a garnish? Yes, seeing a dollop of sturgeon roe resting on top of something already so unexpected and decadent would send your heart fluttering. Yes, in some ways it was a bit too much. But, in its era, it represented a veritable “mic drop” for the restaurant—a use of caviar both bold and indulgent. Today, however, you are happy to see the Kaluga given center stage in its own creations. Both it and the fish ribs shine brightly enough to command attention on their own.

Over time, the aforementioned duo of shima-aji dishes has come to include two more preparations. First, following the pickled sashimi, was placed a preparation of shima-aji head. It is smoked and its flesh (including those coveted bits of cheek) processed into the filling for a crisp sourdough tart. The tart is then topped with a mound of glistening orange trout roe and a lone, tiny pine cone. The crunch of that cone, atop, and the crispness of the tart shell, below, serve to bookend the smooth shima-aji “meat” placed inside. And the trout roe, of course, lends each bite a delicate “pop” of saline, fishy goodness to help moisten the palate. Ultimately, it’s an artful addition to the sequence that impresses not only in its usage of yet another part of the fish, but in the flawless construction of the tart shell itself.

In its superlative, full-fledged form, the shima-aji saw itself used in still one more dish on the menu. And, relative to the other three, this piece of the fish—taken from the loin—is treated far more traditionally. As best as you can tell, it is pan-seared and finished with plenty of butter—likely tinged with something else—arriving at the table dressed in a puddle of froth. The shima-aji’s texture, in this case, transcends even those luscious ribs. With no bones to deal with, nor any charred crust, the loin is a dead ringer for a slab of butter. It possesses all the fattiness you love from the sashimi with all the juiciness of the ribs and then some. Simple? Perhaps, but the dish forms a welcome, classic reference point against which patrons can further appreciate the fish’s other, more creative applications.

Just as soon as Smyth’s shima-aji sequence reached its ultimate expression, Shields tore everything down and started over again. The fish had been a mainstay on the menu, in some form, for more than four years. And, while the chef’s overflowing creativity ensured that no two preparations were ever the same, such a sequence (which had, as previously mentioned, even absorbed the restaurant’s caviar course) begins to cast a shadow over the rest of the meal. The shima-aji was a sure thing, yet its cult appeal could ultimately stand in the way of bigger, better changes at a structural level. Thus, during your last visit to Smyth, the striped jack rode off into the sunset to enjoy a well-earned retirement. In its place, a new sequence dawned: the king crab sequence.

The foundation for a trio of preparations utilizing the crab had been set one meal prior. In many ways, the development of the sequence can be ascribed to Shields’s inspired creation of one particular dish: “king crab in beeswax.” Therein, plump, prime pieces of Norwegian king crab legs are steamed, dipped in the titular beeswax, and chilled. The legs arrive at guests’ tables displaying all the grooves and dimples of “shell-on” crab, yet the beeswax breaks so much more cleanly. Rather than wrestle with seafood crackers to rescue the meat, patrons are empowered to remove perfect, glistening whole pieces of the crustacean out from the faux shell before dipping them in an accompanying sauce. On most occasions, that means a butter made from crab tomalley (the prized fat taken from its hepatopancreas).

In the same manner Shields’s shima-aji “sashimi” preparations sought to express the ingredient’s purity, “king crab in beeswax” offers guests a total refinement of the seafood tower or crab shack experience. Eating king crab is typically characterized by the engrossing nature by which the crustacean’s flesh is retrieved. Be it a half, a full, or even several pounds of product, the customer becomes accustomed to grabbing a shell, carefully removing its meat, and enjoying the fruits of their labor with a squeeze of lemon, some butter, or a Dijonnaise. Rinse and repeat. The labor involved—which may include its share of nicks and cuts—is offset by occasional bursts of crabby goodness. Like so many beloved comfort foods, this effortful manner of eating, you think, lends itself to a greater sense of enjoyment and satisfaction.

Classy seafood establishments may work hard to prepare their king crab for customers. They’ll split the shell, providing easy access to the meat, but neglecting to pull it from the feather-like internal bones that connect it to the body. On other occasions, the primest portions of flesh from the thickest legs of the crab may be cut into chunks and left in the shell. This facilitates their skewering and dipping with a cocktail fork but removes any tactile charm from the process.

“King crab in beeswax” is such a stunning dish due to the way it embraces and enhances the classic crab-eating experience. The beeswax coating, while it sadly does not impart any noticeable honeyed flavor, faithfully embodies the feel of a real shell. Guests can indulge in the nostalgia of cracking into the crab with absolutely no fuss, and they are rewarded with the cleanest, biggest solitary portion of the crustacean—completely ready to eat—they have likely ever seen.

Rather than simply preparing the ingredient, Smyth preserves and refines the entire experience. One shell, yielding one perfect leg of steamed crab, dipped into the most flavorful crab butter imaginable, condenses (and, perhaps, surpasses) the thrill of tucking into pounds of the stuff. The end result demonstrates how Shields is able to embrace novel techniques while never denying an ingredient’s heritage. In fact, he is one of the rare fine dining chefs who consciously channels such high technical expertise towards elegant, sometimes irreverent reimagining of classic forms. He thinks not only in terms of two-dimensional flavor or texture, but the three-dimensional hospitality experience—with all its physicality—his restaurant so expertly offers.

Is it any surprise that this king crab preparation formed a new lynchpin on the restaurant’s menu? The beeswax bite featured on Smyth’s menus but a few times before, ultimately, two other crab dishes were developed to go alongside it. The first—“king crab & almonds”—forms the beginning of the sequence and references those same “lactic” sauces Shields uses to dress seafood elsewhere. The crab arrives thinly shredded, studded with slivers of almond, and lightly dressed in a froth formed with almond milk. While this particular portion might be small, the twofold use of the nut (which, in truth, is actually a seed) works to reveal a lighter side of the crustacean.

The slivers of almond, which you believe to be blanched, impart light notes of nuttiness and sweetness alongside a tinge of tart, green flavor. Texturally, their typical crunch is a bit subdued, preventing any jarring clash with the soft shreds of crab. The sauce made from almond milk, on the other hand, coats and thickens the crustacean. It lends the dish some of the mouthfeel of a crab salad, bringing additional sweet and tangy notes to the party in a way that rounds out the almond slivers. Yes, in some sense, “king crab & almonds” scratches your itch for crab dressed in mayonnaise. The dish’s delicate blend of sweet and nutty notes is, of course, a bit more complex than a New England crab roll, but its refreshing sour finish serves the same purpose: to make you reach for that glass of Ramonet (the restaurant’s typical pairing) and ready your palate for richer expressions to come.

The third and final dish in the king crab sequence—following “almond” and “beeswax”—must, thus, be the most decadent. Shields, of course, does not disappoint. “King crab & marmite,” as this last member of the triumvirate is called, does indeed make use of the world’s “favorite” vegan food spread. (Marmite, of course, is a salty, umami-rich paste formed from yeast extract that is a byproduct of beer brewing. It was popularized in England while Vegemite, an equivalent product, was developed in Australia to cope with Marmite shortages following WWI).

Guests, having been served that delectable morsel of crab leg, are now greeted by the claw of the crab served on the half shell. The discarded portion of the shell shrewdly forms a holder for the chopsticks one uses to grab onto the nuggets of flesh, which have been divided into a few chunks and dressed with furikake (a Japanese seasoning made from toasted sesame seeds and seaweed). Alongside the claw is presented a small dish containing a dollop of Marmite enveloped over a slightly larger dollop of so-called “crab fudge butter.” The exact identity of this latter substance is hard to discern. However, whereas the butter made from crab tomalley (served with the leg) offered notes of both butter and crab, the “crab fudge butter” is much more like the concentrated essence of the tomalley. In that respect, it forms a perfect partner with the Marmite: both substances are as savory as you can imagine, and they close the king crab sequence with a supercharged flavor replete with notes of brown butter and concentrated crab fat.