To the uninitiated, Otto Phan is an enigma at best—and an arrogantblowhard at worst. As the story goes, he sauntered in from Austin some two yearsago and threw down the gastronomic gauntlet: he would not only be the SecondCity’s first Michelin-starred sushi restaurant, but he would earn two of thecoveted stars on his first go-round to boot.

By the time Kyōten, ofwhich Phan is the chef/proprietor, opened in late August of 2018, Chicago hadbeen experiencing something of an omakase renaissance. While sushi conceptslike Juno, Naoki, Arami, Kai Zan, Katana, and Momotaro had succeeded over theyears by offering some version of an omakase among a larger menu ofcrowd-pleasing options, the dedicated omakase restaurant—the proper, standalone“sushi bar” concept—had yet to take root. The failure of Masaharu Morimoto’sJaponais and Gene Kato’s Sumi Robata Bar—more traditional Japanese conceptsfrom bonafide Japanese chefs—hardly showed that Chicagoans were hankering forincreasingly luxurious expressions of Nippon.

As is often the case in this town, Lettuce Entertain You led the wayforward. The group opened Sushi-san at the tail end of 2017, bringing somethingakin to Momotaro’s Izakaya concept to the heart of River North. While therestaurant—which offers sake bombs, tempura, and matcha butter pancakes on itsexpansive Japanese menu—can hardly be called an “ode to omakase,” it did wellto showcase the form. A small section of bar seats within the humming space wasreserved for chef Kaze Chan’s “oma-KAZE,” a 14-course flight of nigiri thatcost only $88. While surely not the most intimate or performative sushiexperience in town, the quality-price ratio was impressive. Kaze did not shyaway from building nigiri with some personality, and he did well to interactwith guests and offer new items over repeated visits.

Despite Sushi-san’s role in laying the foundation for a more matureappreciation of sushi, Chicago’s omakase renaissance started in earnest duringthe summer of 2018. In July of that year, Omakase Yume opened in the West Loop,offering a 15-17 course menu for $125 (and, today, a 17-course menu for $150).Chef Sangtae Park worked for Mirai and Japonais as a sous chef before openinghis own izakaya in suburban Niles. There, over a span of seven years, Parkcultivated a loyal customer base that enabled him to offer, in addition to his à la carte menu, anomakase of edomae-style nigiri (that is, nigiri in which the raw fish is curedin some manner). The success of the suburban omakase inspired Park and his wifeto move to Chicago and open Omakase Yume, which received one Michelin star inthe city’s 2019 Guide. In July of 2020, nearly two years after Omakase Yume’sopening, Park opened TenGoku Aburiya in an adjacent space. There, he offers theizakaya fare he left behind in Niles, completing the circle of his bold (butundeniably successful) transplant.

Just as Sushi-san came on the heels of LEYE’s successful Ramen-sanproperties, Omakase Takeya—the third horseman of Chicago’s omakapocalypse—cameinto being in August of 2018 as an offshoot of Fulton Market’s Ramen Takeya. Infact, it is located in the latter’s basement: a seven-seat space likened to a“speakeasy” by co-owner Satoko Takeyama. Chef Hiromichi Sasaki—who is nearly 70years-old—offers a 16 course menu of edomae-style sushi and small plates for$130. As far as you know, Sasaki is the only Japanese chef in Chicago activelymaking sushi for customers. The scope of his training—either in the UnitedStates or Japan—is unknown, but he is referred to as “one of Chicago’s veteransushi chefs” who formerly helmed Wasabi (also owned by Takeyama).

Kyōtenopened a mere two days after Omakase Takeya, bursting onto a Chicago sushiscene that—in the blink of an eye—was starting to seem a bit crowded. But Phan,despite his rivals’ timing, was not following in anyone else’s footsteps. Hehad laid the groundwork for a move to the Midwest in May of 2018, yearning toenter a “Michelin-starred marketplace” in pursuit of becoming “the best sushichef in the world.” Grand dreams for a chef out of Austin moving to the “bigcity,” but Phan is no phony: he worked at both Nobu and Masa in New York City.You would venture to say that Chicago has never housed a sushi chef of suchpedigree. And you do not mean to insult the venerable, old masters who humblyply their trade here.

Rather, Nobu and Masa both represent a generational benchmark forsushi in the United States. Today, they may not be “the best” in rigid,technical terms, but they have fought and earned a place in the Americancultural consciousness. Not merely for themselves as “celebrity chefs,” but forsushi as a worthwhile luxury, a craft rooted in tradition yet still living, acuisine with a new chapter to be written on this continent. Standing on Nobuand Masa’s shoulders, thus, means taking the craft of sushi beyond replicationor importation of a foreign cuisine. It means applying a Japanese philosophy witheyes wide open to the unique American bounty. Surely, any chef can engage insuch an act (with varying levels of respect and success), but how many havestudied the American sushi canon with the craft’s forefathers? Such was thepromise of Phan’s proclamation: aspiring to be the best while being intimatelyaware of the summit that was scaled before him. It’s the kind of intimateknowledge that transforms such an outrageous declaration—made seemingly of “hotair”—into the bellowing of the very brightest inner fire. Kyōten opened serving an omakase of around 20edomae-style sushi bites for $220 and, since the pandemic, has launched privatebuy-outs for $500-$600 per person.

Whereas Phan is very much the “interloper” when it comes to Chicago’s sushi renaissance, Mako, the last omakase to join the party, stands as the hometown favorite. The restaurant, which you have written extensively about before, is the “passion project” of B.K. Park and the “culmination of his years of expertise seeking out and serving the most pristine fish in the world.” Born in South Korea, Park learned the craft of sushi upon moving to Chicago, where he worked as head chef of Tsunami and Mirai Sushi before opening Arami and, later, Juno as co-owner and chef. The latter, which opened in 2013 and still operates today, has long ranked among the city’s best. Juno has been titled both one of the “Hottest Japanese Restaurants across the US” and “21 Best Sushi Restaurants in America” by Eater. It also earned three stars from the Chicago Tribune’s Phil Vettel. There, with 48 hours notice, Park served an omakase featuring 16 items for $100-$150 per person. Such an omakase must have been unheard of in Chicago seven years ago, and it is no surprise—from his perch in Lincoln Park—that Park became the city’s premiere sushi chef.

Alas, Lincoln Park is no longer a relevant neighborhood for Chicago dining. It houses static concepts for a geriatric crowd that, like mothership Alinea itself (which, laughably, conscripted Park to advise the sushi preparation for their Next: Tokyo menu), has deluded itself into thinking their austere sense of taste still holds any relevance. Though you only ate at Juno once, it did little to distinguish itself from Momotaro (which opened one year later). Other than Park’s prodigious use of smoke-filled cloches, the restaurant felt only a step above strip mall sushi. Still, Park was likely the first to teach this city’s diners what such an omakase looked like. You do not fault him, in 2013, for nesting that menu within a more pedestrian concept. Rather, you wonder why it took the chef until March of 2019 to open Mako. Why, as the de facto sushi shogun of Chicago, would Park be the last—rather than the first—chef to elevate the dining scene with a dedicated omakase concept? And what, with so many more years of experience in this market, could he hope to offer that others haven’t? These questions are better addressed in your full review of Mako, which, it remains to be said, serves around 25 bites of food for $175.

Once the dust settled and the full breadth of restaurants encompassedby Chicago’s sushi renaissance hit their stride, some manner of ranking theestablishments became clear. Phil Vettel, the Tribune’s restaurantcritic, awarded four stars to Mako, three stars to Kyōten, two stars to Omakase Yume, and one star toOmakase Takeya. Just as B.K. Park, due to nothing more than longevity, hasattained a reputation as the city’s premiere sushi chef, Vettel—a buoy (or,perhaps, an anchor) on the sinking ship of print journalism—has sleptwalkedinto the job of representing Chicago’s dining scene to the world.

Truth be told, he’s more of a pimp than a critic. Vettel feelscomfortable awarding stars to restaurants after only a single visit—an ethicallapse that transforms his ostensibly “serious” journalism into something merelyanecdotal. Rather than educate his readership on the art of cuisine, he iseasily cowed by superficial aesthetics and, you think, altogether lacks thecritical faculty required to judge food. For example, Vettel fails to note thequality or composition of Mako’s rice in his review (an absolute fundamental inany omakase) but praises “perfectly-grilled squab” as his “favorite dish.” Thecritic clearly holds a soft spot for “sushi artist” Park, whom he says “hasbeen delighting Chicago palates for 20 years.” However, his review of Makosidesteps any analysis of the quality of his friend’s sashimi and, shockingly,fails to mention nigiri at all. He spends more time describing “a tippedceramic bowl with river rocks” than the texture of even one piece of fish!

In some sense, Vettel must be said to be complicit in stagingsomething of a farce: his review of Mako enables Park to play pretend atoffering a middling “omakase” while the experience, ultimately, is onlyredeemed by cooked dishes crafted (at the time) by Tim Flores, former Oriolechef de cuisine now running Kasama, whom received no credit for hiscontribution. Can the Tribune critic really be called a custodian ofChicago’s restaurant scene when he so willingly misses the point? The focus ofan omakase is fish and rice. Other dishes are welcome, but any review thatfails to engage in an analysis of a sushi chef’s core skills is deeply flawed.Mako, by Vettel’s warped standards, would be better compared to Kikko or Yūgen than Yume or Kyōten. The former, like Mako, benefit from a fullkitchen working behind the scenes whereas only the latter fulfill the elementof the “one man show” that lends beauty and logic to the omakase form. It isabsolutely insulting to compare the restaurants without acknowledging theirstructural differences. Perhaps it is asking too much for Vettel to considersuch things. Perhaps he exists only as a food whisperer for aged urbanites whoalso just don’t know any better. But there is no question that Vettel, inwriting shallow “criticism” for philistines, stunts the growth of the diningscene he (you think) aims to nurture.

Moving on from Chicago’s most estimable critic, Michelin’s 2019 Guidefurther complicates proceedings. While Vettel (on the basis of a single visit)asserted a ranking of Mako, Kyōten,then Yume, Michelin (whose methodology demands multiple visits) chose to awardone star to both Mako and Yume, snubbing Kyōten. It was no oversight, as Michelin’s chiefinspector confirmed: “B.K. and Sangtae [Park] have been in Chicago a longtime,” they noted, while also admitting “we had meals that didn’t quite impressupon us that (Kyōten)was at the one-star level.”

Ouch. For an organization as secretive as Michelin, being singled out for failure to meet their standards is a perverse sort of honor. Clearly, Phan’s prognostication of not one, but two stars had piqued the inspectors’ interest—its brazenness demanded a response. In the end, the Austin transplant seemed to be all hat and no cattle. And, surely, some level of schadenfreude was indulged in by Chicagoans, who might have felt that the Second City was not simply ripe for conquest by out-of-towners slinging expensive raw fish. However, you would wager than any diner—local or alien—who visited Kyōten and compared it to the other omakases would feel an injustice had been done. Even Phil Vettel—as clueless as he is—had to acknowledge the quality of Phan’s food. Just what did Michelin take issue with? And how does a restaurant move forward after falling flat on its face?

You have visited Kyōtenmultiple times—starting only a couple weeks after its opening, proceedingthrough the release of the 2019 Michelin Guide, and continuing during thepresent pandemic. The restaurant, as well as Phan’s cooking, has transformedduring that course of time. (Truth be told, this Texan might be the boldest andmost dynamic chef in all of Chicago). As usual, you will condense the sum ofyour past experiences into one cohesive narrative, paying special attention tothe elements of growth that would escape the attention of first-time patrons.You will also aim to contextualize Kyōtenwith regards to Chicago’s larger sushi renaissance, finishing a job that PhilVettel regrettably fumbled in his own article. Then, with that all settled, letus begin:

You disembark your Uber at the corner of Armitage & Campbell,sandwiched somewhere between Margie’s Candies to the east and 90 Miles CubanCafé to the west. Table, Donkey and Stick does not lie far away—nor doesBungalow by Middle Brow—but, otherwise, this quiet stretch of restaurants inLogan Square’s “Palmer Square” pocket neighborhood hardly seems home to one ofChicago’s most expensive dining experience. (During the pandemic, with aprivate buy-out price tag of $500-$600 per person, Kyōten enters a rarefied list of the most expensivedinners in the entire country—think of that, our own little Time Warner Centeramidst thrift stores and tattoo parlors!)

But you have long since learned that a restaurant’s setting is ofteninversely proportional to the quality of its food. Anyone who has been ensnaredby a “tourist trap” knows that to be the case, yet it holds true for finedining as well. The level of investment required to secure prime foottraffic—let alone anything approaching a “view”—often works to inhibit any fullexpression of the chef’s vision. And Kyōten, aswill be revealed during the course of this review, eschews many of thetrappings of the traditional “fine dining” meal in favor of offering a purer(dare you say postmodern?) omakase. Phan’s unflinching focus is on deliveringflavor, and, as both proprietor and chef, he has marshalled his resourcestowards refining what goes on at the sushi bar itself.

Thus, youare not disturbed to discover Kyōten hasno signage, no awning, no valet or any praise from the “Hungry Hound” hangingon the window. You are no longer even bothered by the screeching of the nearbyBlue Line (though the visible shudder it inspires simply cannot be helped).It’s all penance, you think, in deference to the decadence a chef like Phanpromises each evening. Is Schwa (one of the sushi chef’s favorites sincecalling Chicago home) not much the same way? Or Willy Wonka’s factory for thatmatter? Only those who take the leap are privy to the riches which lay insidesuch an unassuming space. For, to be too concerned with the appearance of“luxury” is to admit a certain insecurity: that the customer might notcomprehend the cuisine, and, rather than educate and advocate for anappreciation of one’s vision, it is safer for the chef to serve them a “photoop” instead.

That “photo op” begins with a slick webpage, a shiny social mediapresence, and a sleek façade in a fashionable part of town. It begins, that is,with “shock and awe.” Customers, through all the content they consume beforethe meal itself, are primed to be pleased. Few, if any, out of the scores of“special occasion” diners sure to rear their ugly heads over an establishment’slifetime, possess palates capable of discerning anything more than “I likethis” and “I don’t like this.” For this customer, the aim of fine dining is notart appreciation. Rather, it is all an exercise in self-pleasure andaggrandizement. The restaurant exists to dote, not to challenge, and they hadbetter measure up to whatever twisted vision of a “good” [read: expensive] mealis rattling around their empty heads.

Chefs who cater to these customers inevitably clip their own wings,stifling free-flowing creativity—risk taking—in favor of crowd-pleasing,picture-worthy fare. They soon find that their job is less about exploringfrontiers of flavor and texture than staging fancy “dinner parties” forwell-heeled patrons who are more concerned with being seen at this or that place(which you can be sure of in the age of social media) than engaging the chef inhis or her creative process. This is all to say, Kyōten is unassuming. It is more or less anonymouswhen viewed from the street and a good bit mysterious when researched online.Kyōten isPhan, and Phan is his own man. A lack of expression, or a prioritization ofcertain senses (like taste) over others (like touch or sight) in theexperience, may communicate more than the most expensive design firm could everdream of.

Authenticity. You think that’s theword. Kyōten,from the outside, does not play to anyone’s expectations of what a $200, $300,$400, $500, or $600 meal “should” look and feel like. Kyōten simply is. It provoke, it demands, it daresthat you raise or lower your expectations in line with your own biases, forit is more than confident in its power to charm you. Kyōten is a restaurant in that eternal sense. A“base,” a “point,” or a “position” (as your online translator would have youbelieve). “The edge of the sky,” if you take the restaurant’s word for it. Itstands outside of trends and time, playing the only sort of game that is everworth playing: Phan’s own.

In many ways, then, it makes sense for Kyōten to stand, inconspicuously, right where itdoes. It is “worth a stop,” “worth a detour,” and “worth a special journey.” Itis too good to care about foot traffic, too confident to worry about itsneighborhood or its neighbors (as estimable as some really are). Kyōten is a world unto its own, and it actually seemsfitting that a liminal space just west of Bucktown’s ancestral goat prairieswould become the home of Chicago’s own sushi “GOAT.”

You step through the door marked “2507,” and it closes with the jingleof bells. The vestibule is sparse (and it used to be even sparser) butaltogether satisfactory. Opposite the door hangs a gilt-framed abstractpainting. A couple chairs and a bench line the walls to either side of it. Therest of the room is empty, save for a few plaques (including Kyōten’s 2020 Jean Banchet Award for “Best NewRestaurant”) and a floor-length curtain that covers the entrance into the sushibar proper. The curtain is buttressed by a chair which holds a placard thatwarns against entering prematurely. You sit for a minute or two, time creepingjust past the punctual reservation time, and start to wonder if your presenceis known.

But the jingling bells never escape the staff’s attention. They areonly working to dot their i’s and cross their t’s before the show begins. As itstands today, Kyōtenserves bento boxes (for customer pickup) from 5 PM — 7 PM preceding the 7:30 PMbuy-out of the restaurant for the remainder of the evening. Before thepandemic, Phan hosted two seatings each evening—at 6PM and 8:45 PM—with asimilar thirty-minute gap in-between. That does not leave much time backstagefor what, behind the bar, is essentially a one-man show. This is particularlysalient, you think, because Phan operates with so little scripting. He’s neverdisengaged, never just “going through the motions,” and—whether having justbuilt twenty bento boxes or served a full omakase before your arrival—alwaysfresh as a daisy and focused.

So you savor those few extra moments of anticipation, confident that,when the curtain finally opens, the evening will flow effortlessly until youfind yourself back on Armitage: ears ringing, palate sated, soul stirred. Andopen the curtain soon does. In steps Kyōten’s jill-of-all-trades:a hostess, captain, and sommelier all in one. She is the newest member of therestaurant’s team, which has grown from two to three (including Phan) overtime. Jill greets you warmly, reads your temperature, and deposits a dollop ofhand sanitizer on your waiting palm. She then disappears, just for a moment,back behind the curtain. Once the “all clear” is given (and thechair-cum-barrier removed), the curtain is held ajar and you are beckoned toenter the dining room.

Upon making your way inside, it is impossible to ignore the sushibar—that is, the heart and soul of the omakase experience. Kyōten’s is made from cypress and finished in asubdued, sandy color. Of course, it is smooth to the touch, but it is notostentatious. It evokes the air of a workshop, of meticulous maintenance (and,thus, durability) rather than a dainty, contrived “luxury” lumber. Atop thebar, aligned with each seat, sit small slabs of blue stone streaked with gold.These accents enliven the wood tones and act as pads for the placement of eachpiece of sushi as it travels from Phan’s hands to your mouth.

The shorter, side-facing stretch of the sushi bar meets the longer,front-facing segment at the corner closest to the entrance. At that cornerstands Phan—already in constant motion—his cutting board and his knives. Behindhim hangs another painting matching that in the foyer. It is larger yet just asabstract, featuring a tangle of black billows with mesmerizing accents ofrusted yellow and brown that bear a passing resemblance to the restaurant’saged fish. The back counter beneath the painting holds a few knickknacks: aporcelain cat, a porcelain cow, a flower pot, and some plateware. The lightingis warm and centers the action on what goes on (and what “goes on” behind) thebar. Yet not to the extent that it quiets customer interaction. Tall curtainscover the windows facing Armitage Ave., ensuring a consistent mood throughoutthe meal.

Those seated at the shorter end of the sushi bar (usually up to twoguests) look across all the action, making for a particularly alluring viewwhen Phan slices fish. Those located on the longer side of the bar (typicallysix guests) undergo a bit more variation. The two closest to the corner havewhat you call “front row seats.” They are positioned to see, among otherthings, the formation of each bite of nigiri (that is, the bread and butter ofthe sushi master’s craft). They also, naturally, are face-to-face with Phan formost of the meal, a luxury that facilitates questions, exposition, andfree-wheeling conversation on any number of topics. However, those further downthe bar are never left out: they have an intimate view of some of the meal’smore eye-catching moments, like Phan’s use of a Searzall blowtorch. They alsowill be privy to any explanations or diatribes offered by the chef, and thereis surely nothing stopping them from engaging him themselves.

Opposite the curtain from which you entered, at the far side of theroom, is a hallway that leads to two gendered bathrooms. Adjacent to thehallway—and still in the dining room itself—a service station holds glasswareand fridges for beverage service. The station also serves as a natural dividerin the corner of the room, allowing Jill to observe what any given diner mightrequire without any obtrusiveness. Across the face of the hallway—and somewhatparallel to the service station—is the curtained entrance to the kitchen. Phan,from behind his bar, has his own curtain leading back into the space. Inside,his jack-of-all-trades manages tasks like retrieving tools or ingredients.Jack’s own culinary bonafides are well-established, but he’s not quite anapprentice. Rather, he’s a “fixer,” an extension of Phan’s own hand that helpsensure he can put on the omakase, uninterrupted, without worrying about settingin motion some of the menial (but essential) elements.

Lastly, on the wall adjacent to the dining room’s entrance, there hangcoat hooks and two consequential photographs. The first, which has stood sinceKyōten’sopening, depicts the original Kyōten: afood trailer that Phan opened six years ago in Austin. That humble location ledto a brick-and-mortar restaurant that opened in 2016 titled “Kyōten Sushiko.” And it is that establishment thatis memorialized in the other picture hanging from the wall: a depiction ofPhan’s apprentice, Sarah Cook, who now crafts her own omakase there back inTexas. That Phan could trust someone to carry the torch down south without himspeaks volumes. It asserts the existence of a certain “Kyōten style” of sushi that transcends what the headhoncho himself is making on any given night. It also speaks to Phan’spersonality: that behind the big mouth stands a more humble, patient mentor.Both photos, though easy to miss, do much to imbue the restaurant’s minimalistdesign with an undercurrent of soul.

After placing your bag on the coat hook adjacent to the curtain, youtake your seat face to face with Phan. He greets you cheerily then continues togo about his work. For, even though the guests are seated, the momentsimmediately preceding the start of the meal entail a flurry of finishingtouches. These motions—which may include slicing and curing fish or simplyarranging the mise en place—strike you as seeming much like a generalmarshalling their forces in preparation for battle. It might be the only periodduring the course of the dinner that guests can get a peek at just how hardPhan pushes himself. (For it is a bit hard to get the chef’s attention—andsolicit his characteristically acerbic wit—as he flies through his mentalchecklist). But there is plenty else to keep you occupied during those final,pregnant moments.

For example, Kyōten’sbeverage list—a leather-bound tome that replaced what was once a two-sidedpiece of paper—leans alluringly against the wall of the sushi bar before you.While super-luxe omakases like Masa place rather obnoxious markups on wine andsake (bleeding dry those “once in a lifetime” customers who dare not spoil thespecial occasion with subpar libations), Phan has wisely resisted turning hisrestaurant into a haven for label whores. Whereas Mako and Omakase Yume, forexample, sell sakes at the $150, $200, $300, and even $400+ level, Kyōten’slist is more focused on bottles less than $100 (with only one or two thatexceed the amount). Each features a short description—“highly refined, supple,and clean” or “strong round tones, lively, and expansive”—to gently guidecustomers, something sorely missing at the other establishments (though, youthink, Yume has since attempted the same). You say that as someone who enjoyshigh-end sake too, merely recognizing that American consumers are not preparedto pay a two or three times mark-up on a beverage they cannot properly conceiveof. Nonetheless, they might take the plunge to impress a date or cap off whatthey expect to be “that one time they tried raw fish.”

The same idea, generally, holds true for wine. At Mako and Yume, thevinous offerings are recent vintage and fairly anonymous: a $100 champagne;lone bottles of Chardonnay, Sauvignon Blanc, and Riesling in the $60-$90 range;and a couple token red wines around the same price. You would term such aselection “representative” but not “interesting.” The wines are, in a sense,anonymous. They tread softly. They are there to secure the lucre of thosecustomers avoiding sake, and the wines just don’t have much to say otherwise.Fair enough, you cannot expect every establishment to curate and eye-catchingwine selection (though, in truth, you believe fervently that sushi offers themost sublime pairing opportunities of nearly any cuisine). At Mako and Yume,the wine is merely an option to ensure no money is left “on the table.”

Kyōten,instead, offers wine much in the way it does sake. Not in the sense of anyconvenient descriptors (which, with wine, strikes you as more patronizing), butrather in the sense that the assembled options are approachable and fair.Champagne, Cava, Riesling, and a token (though, in terms of tannin, wellselected) red wine range in price from $50-$70. While Mako offers a beveragepairing for $85, Kyōten’slands just shy of that at $76. When it comes to corkage, Mako, Yume, and Kyōten each charge $40 per bottle. It’s not aninsignificant amount, but it meets the industry standard in ensuring seriouswine drinkers can bring what they like while dissuading cheapskates who woulddeny a restaurant their margin on alcohol.

What ultimately distinguishes Kyōten’sbeverage offerings from the other omakases is a matter, you think, ofphilosophy. Mako and Yume are run more institutionally, with a dividing line betweenthe “action” of the sushi chef and the hospitality offered on the other side ofthe bar. Chicagoans enter the respective spaces unsure of what to expect, theyare handed a beverage list with a range of sakes they cannot begin tocomprehends, and it is all too easy to be steered towards something expensive(“special occasion”), something easy (“the pairing”), or, more conservatively,towards the one grape they recognize (“that will be $100 please”). In any case,the restaurant wins a bit of breathing room to subsidize the cost of theoverall “experience.”

At Kyōten,the beverage selection is a natural extension of Phan’s indomitablepersonality. He has tasted everything he serves and offers the bottles to theguest as an extension of his hospitality as chef and proprietor. The mostexpensive item sold on the list, a $220 Daiginjo Genshu sake, is labelled as“chef’s favorite sake.” This pricing is not only a far cry from the eye-popping$360 and $490 bottles offered at Mako and Yume respectively (without a word ofreasoning as to why such sakes are desirable), but Kyōten actually connects its most coveted item tothe chef’s personal taste. Ordering such a bottle offers an easy means ofconnecting with Phan, but he would be just as happy selling you a $70 bottle, a$14 glass of wine, or a $2 Topo Chico. Kyōten’sbeverage selection, thus, is not simply one further method of squeezing theguest on top of the price of the omakase. It, in good faith, looks toaccentuate the food and make diners feel at ease. For the food, ultimately, andnot the “experience” or the “occasion” or even Phan himself, is the star of Kyōten. Fine beverages are an accessory, a pleasantcompanion, not a necessity. And, don’t forget, Jiro himself drinks hot tea withhis sushi!

With your beverage order settled, the last details fall into place.Jane places a hot towel before you, which you use to wipe face and hands. Thedirty towel is absconded, and a fresh one is deposited on the same tray. Itwill sit in front of you for the rest of the meal, offering a means to wipe thetips of your fingers after picking up each piece of nigiri. A small, shallowbowl also sits before you and is used as a vessel for a mound of thinly-slicedginger that has been pickled by Phan. Though the nature of the ginger’s brinevaries with each sushi chef, Kyōten’srendition balances zesty, tart, and sour flavors with only the slightestelement of “crunch.” It is tasty enough to snack on (and generously replenishedby Jane as needed) but subtle enough so as never to interfere with the delicacyof the sushi. In that sense, the ginger serves its purpose perfectly as apalate cleanser between bites. It may be the very best in Chicago, where youoften encounter variants that are too crunchy, too pungent, or too subdued.

The last touch before the start of the meal makes for a nice bit ofcustomization. Jane moves from guest to guest with a small platter filled withmulticolored chopstick holders to choose from. Kyōten, surely, is not the first restaurant toembrace this form of personalization; however, the range of playful animals andanthropomorphic comestibles bandied about can only be called charming. They,like the manner of hospitality offered at the restaurant in general, seem tosay: an omakase need not seem stuffy, a high price point need not be indicativeof a “serious” meal. The flavors may be serious, yes, but nature does notdemand you prostrate yourself to reap the fruits of her bounty. One can smile, laugh,and—dare you say—dress and act comfortably when indulging in fine cuisine. Andthe chopstick holders, by their mere presence, evoke such ruminations withoutbeating you over the head with any sense of conscious quirkiness. They makeclear that excellence and self-expression—even whimsy—walk hand in hand. It’s atightrope walk that must never feel contrived, and, when it comes off as itdoes here, it smacks of an authenticity that lies at the core of any greatexperience.

Finally, with a flash, comes the call: “rice!” Once it arrives, theskirmish begins, and you will command Phan’s undivided attention until heleaves you—hours later—happy and full. Describing the cuisine at Kyōten in any overarching way is a daunting task. Aswith any sushi of this caliber, describing your pleasure involves an intricateanalysis of “texture,” “umami,” and—ultimately—“balance.” One must consider thefreshness and quality of the fish, if and how it has been treated (that is,aged, cured, or marinated in the edomae style), how it is sliced,whether it is served as sashimi or nigiri, and how rice, wasabi, soy sauce, orany other ingredients work to build a cohesive bite of food that accentuates agiven fish’s distinct qualities.

Most diners interested in Kyōten’somakase have read or heard about inochi-no-ichi, a particular grain ofrice that measures one and a half times the size of typical sushi rice. Phan isthe first and only restaurant in the country to import and use this strain(which, he’ll admit, is also used by a three Michelin star omakase in Japan).He typically seasons the rice with “the intense taste of aged red vinegar” butsubstitutes a darker blend to pair with richer fish during the later portion ofthe meal. The goal, in Phan’s words, is “unity and togetherness between fishand rice…. The two should be like lovers with a sense of deep belonging to eachother.” It is easy to chortle at such sensuously-described grains, but you mustadmit that Kyōten’srice is a real distinguishing factor.

At Yume and at Mako (especially), the clumps of rice that hold thenigiri together border on being lifeless. They act as platforms for the cutfish—points of contrast—rather than bonafide partners. There is no doubt thatstandard-sized sushi rice can yield top-tier nigiri; however, neither Park [ofYume] nor Park [of Mako] possess the requisite technical skill. The focus atboth their establishments is more decidedly on the fish and the creative waysthey choose to dress it—that is to say, they choose the “style” of noveltyflavor combinations over the “substance” of superbly seasoned and formed rice.(You think it is odd for Michelin to reward the former while spurning thelatter but can only assume that the Chicago inspectors figure the majority ofguests in this city, trying an omakase for the first time, prefer “easy”pleasure).

While Sukiyabashi Jiro, for example, uses standard size sushi rice(albeit, sourced from a special dealer), it is assertively flavored withvinegar, expertly shaped, and placed opposite fish of the utmost quality. Muchof the beauty of the omakase format—and a theme that rings clearly throughout JiroDreams of Sushi—comes from an appreciation of mastery. The traditionalelements at play—fish, rice, vinegar, soy, wasabi—are deceivingly simple butdemand a lifetime of work to refine them into their most superlative form. Itseems to you, then, that Yume and Mako have chosen to embrace gimmicks likepotato chips, jellies, and smoke effects in lieu of study and technicalmastery. Surely, Chicago certainly isn’t a city that demands stilted, static,“traditional” omakases (NYC is overflowing with those, for better or worse).However, critics should not heap praise on bastardized, caricaturizedexpressions of the omakase form that deny its most essential and rewardingelements. What you call “gimmicks” are certainly allowed, but they must bebuilt on the traditional foundations. Otherwise, they add up to a meredistraction from the chef’s lack of skill, and one is left to question whatreally distinguishes Yume and Mako from Sushi-San’s omakase other than pricepoint and setting.

This is all to say: Kyōten’suse of inochi-no-ichi makes for remarkable sushi—not just in Chicago,but at a national and international level. One could claim that choosing anatypical rice is “gimmicky” in its own way, yet Phan has clearly done so inpursuit of his own sense of “balance,” his own distinct style that breaks withtradition thoughtfully. For the American and Chicagoan palate, the larger grainsize (which the chef sometimes compares to risotto) makes for a fuller, moreenveloping mouthfeel. It enables Phan to form larger slices of fish into hisnigiri, which, in turn, means customers are more powerfully struck by eachbite’s distinct flavor and texture. The rice brings a pronounced vinegar flavorto the table (one of the easiest tweaks to rice preparation that few sushichefs indulge in), but, more tellingly, each piece of nigiri arrives fromPhan’s hand as if it were about to break apart. This is what reallydistinguishes the “men” from the “boys” in Chicago’s sushi scene.

While other establishments embrace an “assembly line” model of sushimaking in which the chef makes and serves several bites of nigiri to severalguests, Kyōten’smodel is unmistakably artisanal. Phan makes one bite and hands it to one guestto be eaten as soon as possible. Rinse and repeat. This level of craftsmanshipallows the inochi-no-ichi to really strut its stuff: it reaches yourmouth ready to collapse into a warm mound of soft rice that yields expertly towhatever fish sits atop it. Such is the peak sushi experience, a transfer ofimpeccable texture and flavor from the chef’s hands to your mouth. This directform of service begs the format of the “sushi bar,” and you would not hesitateto argue that any omakase that refuses to shape the rice for each individualbite given to each individual customer is engaged in something close to a scam.Thus, the reality regarding the rice being offered at Chicago omakases becomesclear: Phan invests in excellent rice because he engineers each bite for eachcustomer to be optimal, and his format allows for the quick delivery of themost intricate kind of rice texture. Other establishments lean into offeringgimmicky flavor combinations and toppings because they choose to mass-producetheir sushi and are forced to use gummy clumps of rice that can stand anextended wait time before being served. No manner of novelty, in your opinion,can ever surpass a devotion to perfecting the fundamentals. Phan’s use of inochi-no-ichiproves why.

When it comes to analyzing the quality of Kyōten’s fish relative to other restaurants inChicago, the story is much the same. Phan works with a monger at Fukuoka’sNagahama Fish Market, a venue with less name recognition than Tokyo’s Tsukiji(now Toyosu) Market but, nonetheless, awash with excellent finfish and seafoodlike mackerel, sardine, yellowtail, and tuna. The monger is entrusted withunilateral power to purchase what he sees as the best of the catch—a duty thatoften demands bidding against other restaurants at auction for the mostprecious ingredients. Phan receives the fruits of his labor once a week andshapes the menu around this selection. In this manner, every bite served at Kyōten is built on the back of a local Japaneseartisan, a man of the sea, who exercises his own expertise in service both ofnature and the guest. It is up to the monger to choose the best of the aquaticbounty before him, enabling Phan to apply his range of edomae techniquestowards creating the optimal expression of each fish.

Such a division of labor moves beyond shallow descriptors like “fresh”or “from the source.” Rather, it connects the raw materials which go intoPhan’s omakase—a form that offers a pure expression of his talents as a chef—toanother individual, equally as passionate, expressing their own life’s workdiscerning what “seasonal,” in its most transcendent form, represents. Kyōten doesn’t just have a “fish guy,” but a “meatguy,” an “uni guy,” and a dedicated “tuna guy” too. Certain ingredients, likeblack and white truffles or king crab from Korea, come by way of largerpurveyors. Phan is open to any and all sources in his quest to serve the verybest. However, it is best to view Kyōten’somakase as a tapestry woven by a range of skilled people with a deep reverencefor nature. These connections, which grow richer and more rewarding over time,yield a quality that cannot merely be bought. These artisans connect thenatural to the human, and they assert the sushi chef’s unique role—through hisor her place in a chain of “true believers”—as a custodian of the sea.

Glancing at Phan’s social media posts throughout the week, it becomesclear that he does not serve “fish” in any anonymous, idealized form. He isserving this fish that came in this week and that possessescertain qualities (like size or fattiness) that deserve a unique appraisal andpreparation. This, you think, must be much of the beauty of being a sushi chef:eyeing your product as a painter does a canvas, conscious of your power to pickout the best piece of the best portion and prepare it the perfect way. Thebeauty of the omakase form—being imbued with customer trust—enables thisprocess. From ocean, to market, to the chef’s hands, and to your mouth: anundiluted expression of nature at this moment in time. A moment that cannot,must not ever be the same.

As you discussed in your review of Mako, Park’s restaurant does littleto change their menu. They claim to serve a “seasonal selection of sashimi” andseveral “seasonal selection[s] of nigiri” but allow the finer details to golost among distracting interludes of cooked fare. Yume claims that the “omakasechanges daily based on the chef,” but, from what you remember, the restaurantsticks to a core range of traditional fish a couple interesting seasonalselections thrown in. This makes sense, given the meal is dedicated far more tonigiri than Mako is. Abstaining from using cooked food as a crutch means thatPark (of Yume) is better served by “checking all the boxes” a sushi aficionadomight expect.

Such a decision ensures both full stomachs and the widest range ofreference points to compare different pieces of fish and seafood. However, itinevitably demands serving product that, while good, is not at its absolutepeak of season. Quality (at the very highest level) takes a backseat torepresentativeness, but the comprehensive nature of the menu has made Yume arespectable stepping stone towards higher sushi appreciation. Additionally,while Yume’s à la cartemenu allows guests to try nigiri otherwise not included in the omakase, thesepieces often lack a bit of artistry. Their cost, too, sends the (comparably)affordable menu price careening closer to Kyōten’slevel and begs—given the cost of beverage and poor quality of the rice—a morecritical appraisal of Yume’s overall value.

Phan approaches his menus with none of the preconceived cooked dishesof Mako or nigiri benchmarks of Yume. In truth, he often does not finalize themenu in his head at all. Rather, the chef considers the product sent that weekfrom his mongers, the product he has been aging or curing for periods of time(ranging from days to weeks), and the produce—sourced both near and far—thatmight add a seasonal accent. Of course, there’s the rice, the vinegar, the soysauce, and wasabi: familiar bedfellows who always have a role to play. However,Phan’s process is particularly intuitive. He is driven by maximizing the flavorof the ingredients on hand rather than retrofitting them to what customersconsider a “proper” or “traditional” omakase form. This is not to say that Phanturns his nose up at tradition (for, in truth, his experiences at the absolutepinnacle of the American sushi craft ensure nobody in this city knows itbetter). Rather, in a way indicative of true mastery, he understands and adaptsthe essential philosophy of omakase rather than get caught in the weedsof its rigidity. That is to say, at Kyōten,omakase means a chef’s celebration of the purity and splendor of fish andseafood. It means structuring dishes with a general flow from “light” to“heavy” flavors. It means drawing on “traditional” technique and combinationswhen they get the job done best, and its means not being afraid to transformtradition—to move the craft forward—by thoughtfully incorporating the range ofinfluences only now possible in this time and place.

While Yume deserves respect for its dedication to nigiri and nothingbut nigiri, Phan is not afraid to look beyond the “fish on rice” form. Heincorporates small plate into the flow of the meal—no, not fully-composeddishes of arctic char and duck breast as seen at Mako. Rather, Kyōten’s small plates are very much the equivalentof a bite of nigiri or a few pieces of sashimi. They seem to say, “this fishcould express itself better if taken beyond the traditional limitations of thecraft.” Sea bream, for example, is paired with pickled watermelon. Thick chunksof tuna are glazed with a sauce made from rhubarb. Santa Barbara spot prawn isplaced opposite an arugula salad (dressed with prawn “brain sauce”). And fattypieces of snapper, flounder, and pompano all, in turn, have been served on abed of saffron rice in lieu of the usual nigiri preparation.

On the surface, such dishes strike one as unrelated to “sushi” as itis conceived in the popular imagination. In truth, they merely choose to take adifferent route in pursuit of the same ultimate goal: that is, transcendentflavor. These small plates do not surge forth from some cloistered back kitchen(à la Mako),but they are constructed by Phan with the same care he devotes towards theshaping of rice and seaweed. Thus, you get the pleasure of observing the chefengage in all manner of techniques and manipulations throughout the course ofthe meal. It transforms the “one man show” of the stoic sushi chef intosomething more reminiscent of Carrot Top (in the sense of an eclectic blend ofevocative tools). The perfection of the craft takes precedence, and the craftitself, it should be asserted, is concerned more closely with respectingingredients (helping them fulfill their latent potential) and pleasingcustomers than walking a tightrope that demands the chef only draw on a paltryselection of ingredients.

All this being said, you feel comfortable describing a meal at Kyōten as “sushi-focused,” featuring a variety offish that take the form of nigiri or maki (a roll with seaweed on the outside).As decided by the chef, certain fish will feature in small plates (eitherdressed or accompanied by a couple pristine complements) sliced raw as sashimior simply cooked via searing, boiling, frying, or sous-vide. In this way, it isbest to think of the small plates as actually offering guests a purerexpression of the given ingredients than the traditional forms would allow.They are conceptual tools that help the meal escape a sense of monotony withoutclashing with the chef’s mission to offer the “best of the best” ingredientsserved in the best possible way. This full range of preparations andpresentations is brought forth to meet a given week’s product. And each ofthose distinct pieces—fresh fish, cured fish, fresh produce, the nigiri form,the maki form, the small plate form (with various means of manipulation)—fitinto place differently on any given day.

To escape some of this abstraction, you think it would be good tohighlight some of Phan’s specific dishes. However, the hyper-seasonal nature ofthe restaurant complicates such a task. (All but Kyōten’s most signature dishes are unlikely toreappear in exactly the same form again). The best route, you think, is toelucidate how different preparations over the course of distinct visits work toachieve the same goals and build an experience that, ultimately, pleases guestswith the same net force. Such an exposition offers a testament to Phan’screativity and will be of more service to first time guests who might like toknow where their experience fits into the larger Kyōten canon.

Typically, the meal starts with a flurry of nigiri. Norwegian oceantrout leads the line, along with salmon, yellowtail, and striped jack (alsoknown as shima-aji). Tuna makes its first appearance among the nigirinot long after. It has taken the form of “bluefin tuna,” “bigeye tuna,” “pacifictuna,” “striped skipjack tuna” (with ramp paste), and “lean tuna” eithermarinated in soy or cured and smoke. All the many variations of this mostquintessential sushi fish have regaled you with their depth and intensity offlavor. These, Phan’s leanest, “entry-level” expressions of tuna, surpass manyof the fattier pieces put out by Chicago’s other chefs. At this point, itquickly becomes apparent that Kyōten’slarger grains of rice—so loosely packed together—and correspondingly largerslices of fish simply deliver more pleasure.

Following the tuna, comes mackerel: either “horse mackerel” (known as aji)or “Spanish mackerel,” which Phan has aged for up to two weeks before. Hearingthat the fish has been treated in such a way never fails to make you salivate.Such extensive aging is even something of a rarity in Japan (where Koji Kimura,at his two Michelin star restaurant in Futako-Tamagawa, has earned anincomparable status as the “father of aged sushi”). These pieces, when theyappear at Kyōten providea peek into the future of the craft. Like dry-aging steak—something Chicagoanscertainly have plenty of experience with—the process of aging fish entailscontrolling its degradation. Outer layers rot and are cut away, yielding afinal product of reduced weight but concentrated flavor. Those flavors, itshould be said, are not pungent or sharp so much as layered, resonant umami.The process also leaves the fish with an altogether unique mouthfeel thattreads the line between structure and softness. Phan deserves special creditfor experimenting with his product in such a way.

After the mackerel, appears gizzard shad (known as kohada), afish prized for its silvery scales. Historically, as Phan recounts to guests,Tokyo sushi chefs would be judged on the quality of their kohada alone.Customers would saunter up to the bar and ask to try a piece before decidingwhether to stay or go. Needless to say, Kyōten’smakes the grade, offering a more intensely “fishy” flavor than other piecesthat is still well balanced thanks to the vinegar content of the rice. The bitof sushi history, too, makes for an engaging anecdote no matter a guest’s priorexperience with the craft. Sardine and blood clam round out the opening salvoof nigiri, which closes with a couple of the chef’s signature offerings.

One of these is wild caught Ruby Red shrimp sourced from Alabama. Anabsolute fixture on the menu (when in season), these crustaceans possess aplump, sweet, and buttery profile that puts many preparations of crab and lobsterto shame. Phan does not hesitate to term them the “best shrimp in the world,” amoniker that not only speaks to the chef’s promotion of native foodways but,without fail, makes believers out of guests. Uni, most often sourced fromHokkaido, also makes its appearance during this portion of the meal. The chefis honest about the varying quality and flavor of sea urchin from tray to tray,and he has maintained an endless hunt since opening to secure the very best(evidence of which could once be seen by the tall stacks of empty trays withall manner of labels that laid on the counter behind him). The uni isclassically served on a mound of rice wrapped in a layer of seaweed, apreparation that accentuates both the texture of the roe and its pristineflavors of the sea. More recent renditions combine the fresh uni with brineduni (also from Japan), making for a one-two punch of flavor that surpasses anyother sea urchin served in Chicago.

Next comes the showstopper, the “mic drop” as the chef himself callsit. It’s not quite a piece of nigiri—there’s no rice—but Phan still hands itpiece by piece to each guest. The bite comprises a succulent morsel of tilefishthat has been cooked to flaky perfection and fried so that its skin cracklescrisply. That same skin provides the perfect vessel for a generous dollop ofgolden osetra caviar, which sits atop the tilefish along with a dab ofhorseradish crème fraiche. Though pleasantly shocking when it first appearsbefore you, the bite has been carefully conceived: the fish skin, osetra, andcrème fraiche make for the ultimate riff on the “caviar-potato chip” combinationwhile the warm, buttery texture of the rest of the fish makes for a temperaturecontrast that amplifies the dish’s richness. In some sense, the piece offerstwo caviar courses in one—two that become one as the sturgeon roemingles together with the fish juices, flesh, and remaining shards of skin inyour mouth by the second or third bite. As of late, Phan has put the tilefishat the very beginning of the meal as a sort of challenge to himself. (The logicbeing that guests will struggle to see how the chef, during the course of themeal to come, could ever top something so straightforwardly delicious). Noworries there! The bite is decadent and delicate and a perfect introduction toPhan’s culinary style, which only grows in stature as one sees him wrangle evenbigger flavors together.

This point in the omakase usually marks the transition into the smallplates that precede the final torrent of nigiri. It allows the guest, youthink, to acknowledge Phan’s mastery of the more traditional sushi form before indulgingthe chef more fully in his own creations. You have already mentioned the seabream (with pickled watermelon) and tuna (with rhubarb sauce) sashimi. But howabout king crab? Kyōten’scomes from Norway and has typically been served over rice with a sauce of itsroe or its brains, lending a concentration of crab flavor and fat not unlike acrustacean brown butter. However, Phan did not stop there. Last fall, he beganintroducing Midwestern sweet corn into the mix, drawing out the product’slatent sweetness like a deconstructed chowder. This dish reached its absolutepinnacle this fall, combining fresh (not flash frozen, but actually arrivinglive) Korean king crab with warm corn kernels and a smooth, sweet corn sorbet.

As with the tilefish, Phan cooks in four dimensions, combiningsweet/savory, hot/cold, and crunchy/smooth to deliver a bite that—when all issaid and done—transcends the constituent parts. The sum experience is somethinglike a hypothetical crab and corn pudding—or perhaps it’s a savory sundae?Whatever the label, the dish leaves little question as to what the small plateform offers that sushi does not. It combines ingredients at their freshestusing as little manipulation as possible, and it achieves a superb balance offlavors while forging a deeper, purer expression of the pleasure each partgives. The sushi chef “philosophy” is certainly at work here. Phan simply seesno need to hide his genius under the trappings of Japanese tradition(trappings, mind you, which may appeal to the superficial diner but wouldaltogether stifle a chef with so much more to say).

Yet another of Kyōten’ssmall plates is prepared even more simply, and it has become the sort ofsignature preparation that might even begin to rival Phan’s tilefish “mic drop.”Fresh Japanese octopus is given a lengthy massage and briefly boiled. Smallchunks of the tendrils are then sliced and coated in a sauce of olive oil andavocado. The resulting plate looks deceptively simple, but it strikes you (andmany guests) as the most tender, strikingly unctuous octopus they have evertasted. Phan has played with the preparation from time to time, including partsof the octopus head or pairing the pieces of tentacle with a preparation ofbite-sized firefly squid. He has also tinkered with the sauce, serving theoctopus once with red chili and another time with ponzu aioli. But nothing canbeat the mouthfeel lent by the avocado, and the dish has earned its familiarplace on the menu.

Other small plates served during this segment of the meal are moreausterely Japanese. They have included sous-vide spiny lobster in a monkfishliver sauce, abalone coated in abalone liver, scallop served with jellyfish,skipjack tuna with pureed daikon and ponzu, and beltfish dressed with miso-foiegras sauce. That same beltfish, after it is served as sashimi, is used by Phanto make a bite of oshizushi, a style of “pressed sushi” made by placingthe fish and rice into a plastic mold and compacting them. You must say, it isone of the wackier techniques that you have seen displayed at Kyōten. Yet it is enjoyable to watch and yields anend product that is both aesthetically and texturally pleasing.

Marking the transition back towards nigiri, Phan’s small plates delveinto preparations of cooked fish. However, it should be noted that the majorityof the “action” still occurs in the guests’ line of sight. At most, the chefwill disappear behind the curtain for just a moment to retrieve something fromthe hot kitchen. However, the performance is a far cry from the mysteriousgoings-on in Mako’s back-of-house. Also, compared to Mako’s cooked arctic char(and now halibut) dishes, Kyōten’scooked fish is far less fussy. It, like every bite, fits firmly into Phan’slarger sushi philosophy. That is to say, the chef judges that certain prizedpieces of fish like amberjack collar and tuna rib would benefit from beingcooked. They are not pieces that have been brought in particularly to throwomakase amateurs a “bone,” but part of a larger, delicious dissection and disseminationof every part of a particular fish throughout the lifecycle of the restaurant.It is no surprise then that the amberjack collar and tuna rib can be simplygrilled, then glazed, and served without further adornment. In terms ofelegance and intensity of flavor, only the shima aji ribs served atSmyth can compare.

When these cooked fish dishes demand a bit more heft, Phan draws on aspecial batch of his inochi-no-ichi rice cooked with saffron. The morerobust preparation has played a part in two variants of a fatty snapperdish—one with black truffle and the other with “clam parts” and wine sauce. Thesaffron rice has also partnered sharkskin flounder (both the side and the fillet)as well as pompano. In each case, the rice provides much of the samepleasurable mouthfeel to go along with these fattier fish while the saffronworks well to cut through the richness. Once again, these dishes demonstratehow Phan is able to color outside the lines of “tradition” while stillultimately realizing a philosophy that puts the purity of fish flavor first.

But that is not to say these small plates signal the end of the“traditional” omakase—they were but an intermission. The chef bellows “darkrice!” and, just moments later, Jack hands over a steaming bowl of inochi-no-ichifrom behind the kitchen curtain. This batch, as is customary in Japan’sfinest restaurants, is treated with a darker blend of vinegars to balance thericher bites of nigiri to come. Such a move is not simply a testament to theimportant role rice plays at Kyōten,but it seems to underline the schism between nigiri sequences. By the logic ofthe meal, there are lighter fish to be served opposite the morelightly-vinegared rice, medium-intensity fish and seafood that benefit from theblank canvas of the small plate, and decadent, fatty fish that shine brightestagainst rice texturally but demand it possess a more complementary flavorprofile. From this vantage point, “Phan the craftsman” comes into full view:he’s a man among his fish and his tools, building the menu “brick by brick”based on an intuitive understanding of what should fit where. It is this senseof structure and harmony that strikes at the very core of what an omakaseshould embody. To wit, an omakase is not an invitation to applaud mimicry, butrather an occasion of submission. “Tradition” itself makes no demands of thechef; it is only customer expectations that can clip his wings.

Yet, free as he is in this format, Phan knows when to shut up andsimply make great sushi. The latter section of nigiri includes a laundry listof the sushi world’s most coveted pieces, along with some curveballs. Wildyellowtail (called buri) is sure to appear—sometimes as a special bellycut, other times with weeks’ worth of aging that lends the fish a transfixingpale tawny hue. Tuna, which appeared at the start of the omakase in its leanest(and also, perhaps, its most flavorful) form, returns ready to strut its stuff.Chūtoro—knownas “medium fatty tuna”—marks a perfect middle ground between “fish” flavor andfattiness. Phan, from what you recall, serves it rather traditionally, a choicethat highlights its moderate characteristics relative to the other tuna pieces.

Otoro, “fatty tuna,” is often thought of as the crown jewel of a sushimeal. Whether its fetishization stems from a sincere, but misguided, love offat (see: all the subpar wagyu slung in this country) or has been primedthrough repeated placement at the pinnacle of the meal (along with the pricingto prove it) is unclear. Otoro is a joy to eat—you must admit that—but a greatpiece of nigiri should aspire to express more than pure umami. Phan, as he doesso well throughout the meal, does not feel pressured to treat his mostluxurious ingredients in an overly precious way. While some chefs opt toexpress uni or caviar or fatty tuna as purely as possible—inviting guests tobow down before the altar of Bacchus and thank the heavens for their meagerration of manna— Kyōten’schef displays a familiarity and comfort with the most coveted arrows in hisquiver. Just as the uni nigiri blended both fresh and brined sea urchin tocreate a more vivid, fuller expression of the ingredients, Phan is unafraid ofoffering his otoro a bit of help in expressing its true depth of character.

One night, that might mean searing the fatty tuna with his torch andtopping it with yuzu zest, a sweet (caramelized) and sour accent that playsnicely off of the fish’s latent richness. On another occasion, you might seethe chef stack not one, but two slices of otoro on his rice—making for ablanketing effect that plays the firm and fatty constituents of each slice offish against each other. Sometimes, Phan will go through the laborious work ofremoving the otoro’s sinew. This removes any remaining sense of “chew” orstructure from the fish; the result being something akin to spreadable “tunabutter.” If those options are not enough, otoro also provides the chef with theperfect vehicle to showcase edomae aging technique. One-month- and35-day-aged fatty tuna have both made an appearance, displaying a wonderfulconcentration of their natural flavor along with a slightly firmer mouthfeelthat, just the same, yields ever so easily to the gushing pockets of fat.

Otoro, for many, represents the very summit of an omakase meal, yet Kyōten charges full steam ahead. Mackerel, with itsoily texture and pronounced fish flavor, forms a fitting follow-up to theephemeral fatty tuna. It appears, at times, as a traditional piece of nigiri;however, Phan has also once shaped the sliced fish around the top of a piece ofuramaki (a sushi roll with the rice facing outside) before. There, themackerel’s intensity had plenty of rice and “roll filling” to contend with,making for a rewarding, improvised combination that achieved a surprisingbalance. And Phan is not shy about serving classic sushi rolls either: theywere his bread and butter when working out of the trailer in Austin. Hisminimalist avocado roll—as pure a celebration of texture as any maki canattain—has occasionally featured on the omakase from the very beginning. Othercreations—like a “real” California roll made with Kyōten’s excellent king crab—may be offered uponrequest. Even the dreaded Philadelphia roll (smoked salmon, cream cheese, andcucumber) has made an appearance before, standing as a testament to both Phan’sirreverent streak and—when done so well—to the merit of such aseemingly-sacrilegious combination.

For those diners less inclined to worship the fattiest of Phan’s fish,the chef’s meat might do more to delight them. Wagyu, that much-abused monikerfor “really really good” beef, is given the respect it is owed at Kyōten. (The cow sculpture on the bar behind thechef would also seem to indicate so). The meat is typically sourced fromMiyazaki or Hokkaido and always holds the highest “A5” (superior yield quality“A” and superior marbling “5” on two five-point scales) rating. Phan is partialto the tenderloin portion of the cow, which is well-suited to showcasing thefull benefit of beef with such high fat content. As with the fish, he ages thecut to concentrate its savory, umami flavors. Chicagoans are certainly nostranger to dry-aging, but the size of the bite the chef will ultimately serveallows for the technique’s application to a piece of meat that would otherwiseshrink too much to be served in a steakhouse.

Phan’s inaugural preparation of wagyu took the form of 2-week-agedHokkaido wagyu tenderloin served as nigiri in a “prime rib style” (with gratedhorseradish). Though fresh, hand-grated wasabi from Japan finds its way intomost every course of Kyōten’somakase, large swaths of the American public have been misled by the green-dyedhorseradish masquerading as wasabi at many mid-range sushi restaurants. Phan’sdecision to embrace domestic horseradish (albeit, in its natural tone) ratherthan the more expensive Japanese variety for this one dish demonstrates hiscommitment to pleasure. Wagyu in Japan really will be served dressed with wasabi—thenative variety adding a mild, cleansing counterpoint to the rich beef. Americanhorseradish is more shocking, more pungent, but unmistakably nostalgic foranyone who has indulged in a classic shrimp cocktail or prime rib dinner at aplace such as Lawry’s. Americans (and Chicagoans as the cosmopolitanambassadors of the “heartland”) like big flavors. So, rather than serve adelicate slice of fatty beef on a sizzling stone with a schmear of wasabi enla mode Japonais, Phan torches a hearty slice of his dry-aged tenderloinand serves it on his large grains of rice with horseradish instead. The endresult is wagyu nigiri for a “steak and potatoes” city; that is, it strikes thepalate as a complete, pleasurable bite of beef rather than encouraging some austerestudy of the cow’s fat content.

But Phan is no one-trick pony, and he could never hitch his wagon to asolitary beef preparation no matter how playful the combination. He has served30-day dry-aged wagyu tenderloin—an “experiment”—as nigiri in the traditionalJapanese style. He has sourced Hokkaido snow beef tenderloin—an extra fattybreed due to their icy living conditions—for one preparation, being the onlyrestaurant in the country to use that particular cut. Sometimes, the beef willbe served atop a small bowl of rice and then drizzled with its rendered fat,allowing for greater control of each bite’s composition. Wagyu has evenappeared inside of beef broth, with a paste made of black truffle blended in tomake for a superlative “stew.” These many shapes and sizes of beef dishes—arange also seen in Phan’s treatment of the king crab and tuna—underline that Kyōten is a restaurant in flux. The chef never feelshe has discovered the “perfect” preparation for any one ingredient—bending eachweek’s provision into an established form. Rather, Phan’s process is anunending quest for greater ingredients treated with ever-increasing carein pursuit of the unattainable, ultimate flavor they may give. Thus, it is hardto know what sort of wagyu will be served on a given evening or how the dishmay be put together. But it is safe to say that guests with receive the bestbite of beef Kyōten hasever served, and that the same will ring true the following day.

Following the wagyu, the meal’s denouement proper begins. Eel, thatbarbecued blight that seems to taste the same at every omakase, is preparedwith far more care at Kyōten.(Phan will be the first to tell guests that most other establishments receivethe very same packages of precooked product). The chef serves unagi (freshwatereel) rather than anago, the saltwater eel which typically predominatesat sushi restaurants. The former is richer and fattier and typically consideredtoo decadent to be made into sushi (rather than simply served over rice).Phan’s butchery of the fresh eel has caught many an eye on social media, andthe end result has made you question whether you can stomach subpar anago everagain. Often, the unagi is cooked then torched and served in the samemanner as all the other nigiri—that is to say, it benefits from little morethan the vinegared rice, wasabi, and a bit of soy sauce. Yet you are struck bythe freshwater eel’s natural sweetness, one that demands no heavy-handed use ofthe stereotypical “eel sauce.”

Such sweetness makes a strong case for eel’s status as a luxury fish,but that does not mean Phan cannot have fun with it. One recent preparation sawthe tender slices of anago take the place of braised pork in a bowl ofMexican-style mole with crema. Not only was the mole’s depth of flavorcommendable (for a sushi chef of all people), but the sweetness of the eelproved so powerful, its texture so stunningly unctuous, that the end resulttasted a lot like Texas barbecue burnt ends. You cannot imagine that eel hasever been treated in this way before, and it clearly benefits from theapplication of such a nuanced sauce that moves, again, beyond the one-notesweetness for which the fish’s traditional preparation is known. This kind ofdish—which resists any shallow claim of “fusion” or “appropriation” by means ofits boldness—reveals Phan’s mind at its most uninhibited. It imbues the mealwith a powerful sense of singularity—that nobody else in the world, at thisvery moment, is eating any eel preparation that’s so off-the-wall (and, yet,rooted in authentic cultural exchange).

As exemplified by the dual eel preparations just mentioned, this pointin the omakase typically turns from nigiri back towards small plates. Smallplate—singular—that is. Phan closes out the savory portion of the meal with asense of elegance and, more importantly, restraint. He no longer seeks toimpress—having already scaled the heights of decadence and luxury throughoutthe evening—but, rather, leaves the guest rubbing their belly with a contentedsmile. These closing dishes have included, over time, matsutake mushroom withwhite truffle in a mushroom broth, white truffle shaved over rice, whitetruffle shaved over wagyu-fat-infused congee, and a simple miso soup made fromspiny lobster stock. While these final, truffled bites of inochi-no-ichi serveto underline its superlative texture throughout the meal, Phan’s broths alsodeserve special praise. They rank, you must say, as the best soups served atany omakase in Chicago and some of the very best in the city overall (rivaledonly by soup specialists like Chris Nugent of Goosefoot).

Phan’s aforementioned fondness for Philadelphia rolls—a humanizingguilty pleasure for a top-tier itamae—is not merely a quirk. The chefclearly sees nothing sacrilegious about combining cheese and sushi, and, fromtime to time, he proves the point by looking far beyond lowly cream cheese. Asa transitional course between savory and sweet, Phan puts forth a nigiri ofCamembert cheese that has been kissed with the torch until it bubbles andclenches the top layer of rice with its milky tendrils. Relative to thePhiladelphia roll, no fish were harmed in the making of this bite. Rather, it’san undiluted celebration of an excellent cheese. Phan surely isn’t the first tocraft such a treat, but—as is often the case at Kyōten—his larger grains of rice lend the Camembertan incomparable canvas to ooze in between and rest against the tongue. On otheroccasions, Green Hill—an American double cream cow’s milk cheese made in thesame style—has substituted for its French counterpart. It melts in the samemanner, but, in contrast with the Camembert, the domestic variety is servedwrapped around a piece of seaweed with rice at the bottom and a drizzle ofsweet soy sauce on top. The Green Hill may lack the subtlety of its Frenchinspiration, but it makes up for that with the purity of its grassy milkflavor. These lactic notes form a fitting partner with the seaweed and sweetsoy, which, in structural terms, bring the “cheese course” even closer to resemblinga “proper” piece of sushi.

At long last, the omakase reaches dessert. And, for once, Phanattaches himself fully to tradition. Tamago is the name of the game—the(slightly) sweet folded egg omelette forming the quintessential ending to anyomakase. Those who have viewed Jiro Dreams of Sushi are familiar withjust how demanding creating this deceptively plain, unspeakably nuanced dessertcan be. Should the texture be more like a cake or a custard? Should the flavorsmack of egg (with a touch of sugar) or something more like caramel (with a touchof egg)? For a chef used to coloring outside the lines with his most prizedingredients, the humble tamago demands Phan’s supplication. While it is fair toask how a prime piece of fish might best be utilized, running the gamut oftechniques from any particular culture that may lend themselves to the task,something so beguilingly simple leaves no room to hide. The technique andexecution must simply be perfect, as any sign of a twist or gimmick all buts admitsa certain failure at the task at hand.

For this reason, Phan shied away from serving tamago for a time. Ithad appeared on the omakase during the first few months following Kyōten’s opening but later receded as the chef feltit was not quite good enough to form one of the menu’s mainstays. (Such are hisstandards!) That original rendition—served during your early visits to therestaurant in 2018—already ranked as the very best in Chicago. It featuredsomewhat of a “wet,” custardy sheen, a flan-like texture, and a rich, tresleches-style flavor. In short, it was an egg omelette for dessert lovers(but one that, nonetheless, resolutely featured the “egg” flavor front andcenter). You were sorry to see it disappear for much of the following year butfelt heartened by the dynamism shown by Phan’s other dishes.

Finally, after some prodding by guests, the tamago returned to themenu in 2020—and it’s better than ever. The present rendition is firmer anddrier to the touch (which is to say that the texture is more traditional) whilesacrificing none of the lip-smacking flavor that first distinguished it. Phanhas even, as of late, toyed with utilizing duck eggs for the batter, whichimpart still-greater richness to the tamago. But the beauty of the bite, whateverits form, comes from its delicate sweetness and a mouthfeel that caresses thepalate confidently, soothingly as a coda to the countless inochi-no-ichi creationsthat comprise the omakase.

Now, for the closer. Not a bang, not a whimper, but something serene.Something poised, self-possessed, and pure as the many pristine fish whichformed the meal. While Mako and Yume embrace manipulated desserts like matchapanna cotta (with red bean and pistachio), Japanese “soufflé” (with saskatoonberry), or warm Japanese sweet potato (with whiskey caramel and crème diplomate),Phan carries his philosophy towards sourcing the very best ingredients down tothe very last bites. In fact, during the period where the chef’s tamago did notfeature on the menu, this one dish would anchor the entire “sweet” portion ofthe meal. Phan deserves some special credit for not outsourcing the duty ofdessert to the underlings hidden away in a back kitchen (à la Mako) or simply strikingupon a singular, unchanging offering (àla Yume).

The last piece of plateware arrives at the bar, and you look down tofind a few succulent pieces of Michigan cantaloupe drizzled in local honey. Ormaybe, this week, you’ll find strawberries in syrup or persimmons in plum wineor, perhaps, sliced pears soaked in jasmine tea. Maybe it’s mango season. MaybePhan has some extraordinary whole strawberries from Japan, or Frenchcantaloupe, or Fuji apples (in spiced plum wine). From time to time, thestrawberries might even be white (and come served with a decadent miso cream).Whatever the case, the name of the game is fruit: fruit in a form thatapproaches perfection.

For, an omakase formed through careful manipulation of the sea’sbounty should not be capped off with the contrived creations of a pastry chef.Rather, the chef’s mind should be allowed to roam towards the sweeter side ofnature. Seasonality and the chef’s own discerning standards do the rest of thework. Each piece of fruit shines as the very finest exemplar of its respectiveflavor and texture; that is to say, the same precision which characterizes Phan’sfish preparations finds its way into dessert. Such magnificent morsels demandnothing more than the lightest of dressings. Honey, sugar syrup, plum wine,tea, and cream, in turn, form fitting partners. Just as the chef balancesvinegar, wasabi, and soy, he delicately accents his fruit in fulfillment of itsmost superlative flavor. Diners may think, “is that all?” at first, but these closingdishes can only speak to Phan’s confidence (regarding the satisfaction his mealimparts) and commitment (to a philosophy that prizes an elegance that onlyquality ingredients, served simply, can entail).

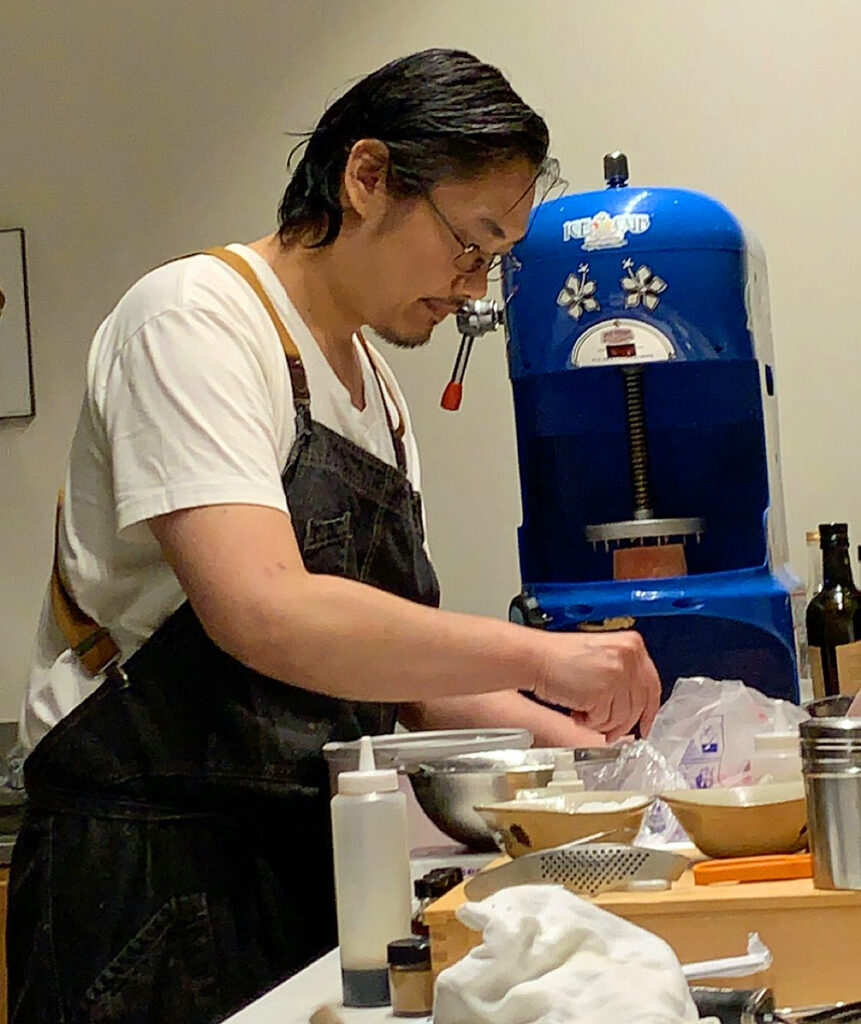

Phan’s move to private dining, it must be said, has empowered him tomake Kyōten’sdessert a bit more involved of a process. Still, it does not sway from itsfocus on the purity of fruit flavor. Now, when the time comes, the chef lugs a brightblue contraption onto the counter that looks something like a stand mixer onsteroids. It’s actually an electric ice shaver, which Phan uses for the productionof his own kakigōri. Now, those who have read your Gaijin review mayrecall that the variant of kakigōriserved there, while visually appealing, suffered for a lack of adequateflavoring syrup. Kyōtensolves this problem through the creation of their own “super frozen strawberryice” which ensures that each an every shaving smacks of fruit flavor. The blockof ice is put through the machine, with the pulverized shards forming a pillowymound over a reservoir of miso cream. A bit of gold leaf is strewn on top forvisual effect, but the dessert remains one of pure flavors and carefully-controlledtexture. It forms a fitting, fun final act for a sushi chef extraordinaire.

In the afterglow of Kyōten’somakase, your mind does not quite know which dishes to latch onto. In somesense, the task is a lot like choosing one’s favorite segment of arollercoaster ride: of course, the steepest drops (e.g. tilefish and caviar,crab and corn) regale you with their intensity, but are they anything without theanticipation, the bobs and furrows that ensure you never quite know when the “bigone” is coming? And should one really reduce the sensation of a rollercoasterride down only to its peaks? Does the thrill not come, in part, from ridingalong a carefully constructed track where every dip and turn tickles you with adifferent sensation? Part of the pleasure, it seems, arrives simply from thefeeling of the lap bar against you—its promise that you must only submit (andkeep your arms and legs inside the vehicle) to be whisked off on a tour ofwonder, an experience that amounts to more than the sum of its parts.