You loathe chain restaurants. So, despite finding D.C.’s minibar to be one of the finest “molecular gastronomy” restaurants in the country, you viewed José Andrés’s Midwestern expansion with a bit of disdain.

The chef, no doubt, has redefined his profession—demonstrating, over the past decade, the key role it can play in tactically responding to sudden incidences of food insecurity. World Central Kitchen has transformed America’s goofy ambassador of Spanish cuisine into a sage humanitarian who has utterly transcended his association with the cloistered world of fine dining.

But ThinkFoodGroup, certainly, is not a charity, and any moves that Andrés makes as a restaurateur must be subjected to the same cold analysis you apply towards Chicago’s homegrown “talent.”

Axiomatically, you believe that the Windy City benefits little from interloping concepts that made their names pleasing a different set of patrons in a different place. Outside restaurants might help occupy pricey real estate and provide employment. Residents and tourists alike may, at first, be drawn to some transplanted novelty. But these shiny openings rarely lay down deep roots.

They divert attention away from local competitors within the same genres and flex their corporate muscle to capture a lowest common denominator customer whose patronage, like it or not, pays the bills.

In a city where even the most talented chefs, save for a select handful, are unequipped to cook with complete devotion to the rhythm of the season, diners cannot afford to have their local foodways further obscured, forever unfulfilled, by a steady stream of slick expansions ready to penetrate the “flyover” market.

Talented restaurateurs may look to manage such an impression. When Midwestern native Danny Meyer opened his first Shake Shack location here in 2014, he larded the chain’s usual menu with Publican pork sausage and pie from Bang Bang. (The restaurant he subsequently opened in 2015, GreenRiver, was a totally unique concept relative to his other USHG holdings and even earned a Michelin star before closing in early 2018). But chefs who possess a robust personal brand—like Gordon Ramsay and Nobu—often feel no need to cater to the city beyond posing for occasional photo ops.

That strategy may work out fine when addressing one of the native dining scene’s more underrepresented genres. However, when celebrity chefs leverage their promotional talent alone to siphon business from worthy local establishments, they should be treated with contempt.

For outside franchises that are lazily grafted onto the local market often spurn developing relationships with small farms. They often build anonymous wine lists in partnership with large national distributors. And they institute bland, cosmopolitan service standards that suppress regional character. Such restaurants are invasive species that flatten the organic development of diverse, distinct cultural forms for the sake of feeding perpetual corporate expansion.

When a far-flung chef looks to enter the Chicago market, you hold them to the standard set by Gastón Acurio. The renowned Peruvian chef opened Tanta in 2013, and the restaurant remains totally different from his La Mar concepts in San Francisco and Miami. (While there are other Tanta and La Mar franchises throughout South America, those in the United States feel singular).

Likewise, when it comes to offering more approachable fare within a crowded genre, Gabriele Bonci, too, has set a high standard. His Roman-style pizza al taglio does not only represent a distinct product (relative to the city’s many other crusts), but the chef chose Chicago as the very first location for global expansion. In a highly saturated market with sharp loyalties, the chef made locals feel special. He honored the dining scene with something totally unique rather than simply sapping it.

Thus, when José Andrés announced in 2019 that the Windy City would be home to Jaleo’s sixth location (after D.C., Bethesda, Arlington, Las Vegas, and Disney Springs but before Dubai), you were hardly enthused. Spanish tapas may not form the largest genre here, but there are a handful of examples scattered throughout the city (most of which maintain higher ratings than Jaleo on review aggregate sites). Tacking on a basement speakeasy, Pigtail, would not be enough to frame the franchise as something tailormade for Chicago.

Bazaar Meat, announced in 2021, sounded a bit better. The concept, at that time, only existed in Las Vegas (though a Los Angeles location has subsequently been announced). Its namesake, Andrés’s original pair of “The Bazaar” properties, had only operated in Los Angeles and Miami (though a New York location has also subsequently been announced). Relative to Jaleo, Bazaar Meat would offer Chicagoans something a bit more special. And Bar Mar, the restaurant’s downstairs seafood counterpart, was both entirely unique to the city and much more elaborate than Pigtail.

Andrés, nonetheless, had resolved to sell meat to a steakhouse city. What could he hope to offer that BRG, DineAmic, Gibsons, Hogsalt, LEYE, Morton’s, and What If Syndicate had missed? (To say nothing of BLVD, Boeufhaus, El Che, Cherry Circle Room, and the like). Did the Spanish chef really want to join the ranks of other lackluster imports such as Barton G., The Capital Grille, Del Frisco’s, Mastro’s, McCormick & Schmick’s, Ocean Prime, Ruth’s Chris, Shula’s, Smith & Wollensky, Steak 48, and STK?

Chicago is a mature market when it comes to beef. It has seen all manner of American, Australian, and Japanese wagyu slung. It has seen wet-aging, dry-aging, and rooms filled with Himalayan salt bricks. It has saddled its steaks with seafood, pasta, and asado fare. Yet you have still never seen anyone beat the humble USDA Prime served at Bavette’s, and every new iteration of the genre seems to lean on this or that gimmick. Would Bazaar Meat be nothing more than Jaleo + steak, or would it envelop itself with a sense of Las Vegas, L.A., and Miami “luxury” that would only serve as a precursor to Salt Bae’s eventual arrival?

Luckily, there was a ray of hope. ThinkFoodGroup was not going it alone but, rather, subscribing to that old chestnut: “if you can’t beat them, join them.”

While Andrés typically partners with hotels when opening his sprawling Bazaar properties, aligning with a restaurant group in the target market is rather unheard of. Tethering two hospitality brands to each other—that must then cede control of certain processes and creative decisions they are used to determining wholly—seems like a recipe for disaster. How do they retain the look and feel of their respective identities without stepping on toes or clumsily cobbling them together?

Though that challenge loomed large, the partnership held plenty of promise. With Gibsons Restaurant Group, ThinkFood could lay down a foundation rooted firmly in Chicago history. In them, Andrés held a golden key to the city’s steakhouse genre that would buttress his innovation with an ironclad assurance (built by Gibsons over three decades of operation) of quality and value. Together, they would promise “an unmatched level of hospitality and an authentic culinary experience” rooted in TFG’s “culinary ingenuity” and GRG’s “operational expertise.”

Due to the pandemic, Jaleo would not open in Chicago until the summer of 2021. However, the delay allowed for a staggered set of openings (followed by Pigtail and Café by the River) in the build up to Bar Mar and Bazaar Meat’s debut at the very end of the year.

The restaurant would be located in the new 55-story Bank of America Tower at 110 N. Wacker. Though only a stone’s throw away from the crown jewel of the Gibsons empire, Italia, the collaboration would seemingly not cannibalize any business from the existing property.

Beyond featuring some of the same Prime Angus beef, the two restaurants would comprise entirely different offerings while appealing to their respective populations of office dwellers located within and surrounding their buildings. Italia would continue to boast a postcard view at the mouth of the river while Bazaar, positioned down the south branch, would be well situated to take advantage of that particular segment’s future growth.

Bar Mar and Bazaar Meat would ultimately open on December 15th. Andrés held court during a media preview the night before then left his trusted staff and partners to take the reigns. They would make a slow, methodical start—limiting the number of seatings during the first weeks and ensuring Gibsons’s vast array of regulars got a chance to put the place through its paces before embracing the wider public.

You dined at Bazaar Meat for the first time in early December. That was followed by a subsequent visit in mid-February. However, in March, the restaurant suffered a “mechanical issue in the kitchen that requires immediate attention” and that has hampered its ability to serve much of the original menu.

Though such a blow might have crippled most concepts, Andrés had a trick up his sleeve. Prevented from offering the full assortment of grilled steaks and seafood that define the “Bazaar Meat” concept, the chef leaned on his classic “The Bazaar” offerings from the original Beverly Hills flagship. He offered guests “a menu of the most popular, beloved dishes” across the sister restaurant’s 14 years of operation alongside whatever elements of the original menu that could still be executed. This move did not only ensure that the property could stay open throughout its repairs, but offered Chicagoans something like a “greatest hits” pop-up of Andrés’s previous work. (And no, you do not mean Next’s abortive effort).

You sampled this “temporary dining experience” reflecting “the beginning of Bazaar” in late April. Though the majority of the dishes you sampled then will disappear and have little bearing on what guests find once Bazaar Meat returns in earnest, you found this last meal to be consistent with past visits.

Thus, on the basis of two “Bazaar Meat” and one “beginning of Bazaar” experiences, you feel comfortable speaking to the atmosphere, beverages, service, and cuisine that define the ThinkFood and Gibsons Group collaboration. Though the menu’s schism means that some of the fare you describe will no longer be relevant down the line, you will still condense the totality of your impressions into one, cohesive narrative.

Lastly, in the interest of full disclosure, it bears mentioning your close relationship with Gibsons Group’s beverage director. Though, in their role, this individual manages the programs across multiple establishments, Bar Mar and Bazaar Meat operate outside of that direct influence. Andrés’s wine program, which you go on to describe in detail, is instead the brainchild of the talented Christian Shaum. Any opinion offered on his work—as well as on Bar Mar and Bazaar Meat in general—is strictly your own.

With that covered, let us begin.

Randolph Street, home to West Loop’s “restaurant row,” has long been a gastronomic thoroughfare. The real action, of course, begins west of the highway. Yet Grace, Yūgen, Blackbird, avec, Embeya, Bellemore, Alla Vita, Sepia, and Proxi have certainly done their part to define the corridor between I-90 and the French Market. And now it is fair to say that Randolph’s sprawl of superlative dining actually begins east of the river at its intersection with Upper Wacker.

The Bank of America Tower stands on a block that surely feels like “downtown.” The triple-wide lanes and lines of skyscrapers impart a feeling largely lost to time: having a grand meal staged within Chicago’s metropolitan bustle. Yet Andrés has not cloistered his establishments too deeply within the Loop, an area known to become a veritable dead zone after hours.

Bar Mar and Bazaar Meat occupy an attractive corner of the urban landscape with trees, shrubs, and planters a plenty set within a courtyard space—now operating as a gorgeous patio area—that abuts the bridge and the river. Though a couple other towers (100 and 150 North Riverside) bookend the view facing westward, the sky that lies beyond them is relatively uneffaced (for now).

In fact, if you look towards the restaurants from Randolph, it becomes apparent that their windows tilt a few degrees off center from the rest of 110 N. Wacker. This trains guests’ eyes directly over the bridge and down the river towards Wolf Point, the home of Chicago’s very first tavern and eating house. Truth be told, the view does not come anywhere close to that of Gibsons Italia or even RPM Seafood. Yet the ripple of the water, the occasional creaking train, and the diamond-pointed edifice that frames them do make for one of the city’s more attractive mealtime tableaus.

Ultimately, though entering the Bank of America Tower feels very much “big city,” the orientation of Andrés’s restaurants transforms them into a liminal space. Though you approach from the street and enter through the monolithic front façade, Bar Mar turns your posture northwest. While the staid elevator that takes you up to Bazaar Meat underscores the building’s commercial utility, the elevated position it provides doubles down on the effect.

Relative to Jaleo and Pigtail, which jockey for foot traffic from River North’s transitory denizens, Andrés’s Loop properties are positive outposts. They presage a resurgent downtown that draws the energy of Wolf Point, Gibsons Italia, and West Loop further south. Yet, until that time comes, they form a threshold through which Chicago’s business district fades and a fashionable haven of hospitality begins.

Beatnik on the River and GoodFunk, Bonhomme’s natural wine bar concept, might help contribute just a bit to that feeling. There’s also a Beatrix (LEYE’s invasive, offensively bland all-day concept) set to open across the street soon. But ThinkFood and Gibsons have created a magnet destination of great import for the neighborhood. Their collaboration helps drive Chicago dining towards a new frontier, slowly recentering it at the city’s neglected nexus.

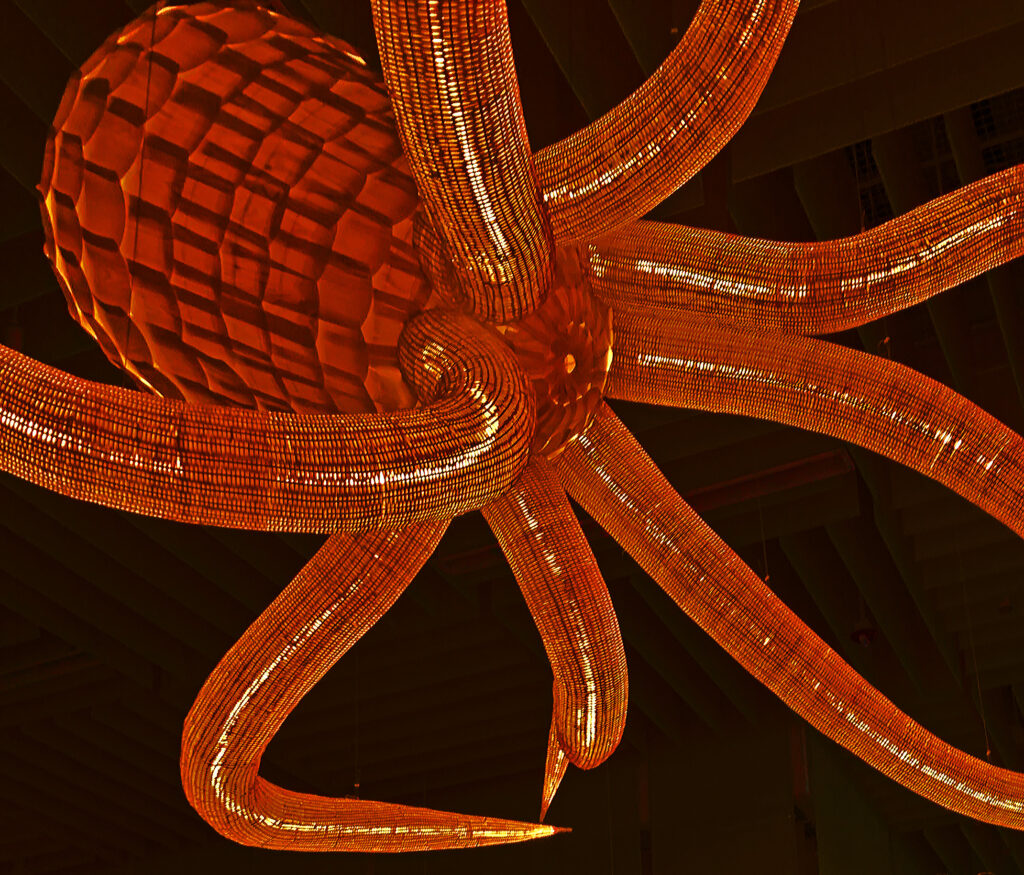

Nonetheless, this larger context is not readily apparent once you step inside Bar Mar. The space absolutely brims with energy, and it is hard to look away from the hanging octopus sculpture (“a TKMATERIAL glittering TKSIZE octopus” to be exact) that forms its centerpiece. Though the present piece will not engage the downstairs restaurant thoroughly, a short overview is order.

Relative to Bazaar Meat, Bar Mar is Andrés’s more approachable concept. While the former is open only for dinner, the latter welcomes guests for lunch starting at 11 AM (Monday through Friday). That essentially makes Bar Mar an all-day enterprise suited to host business lunches, pre-meal cocktails, more casual dinners, and late-night imbibing. Given that Bazaar Meat only allows complete parties to go up the elevator into the restaurant, guests will likely find themselves whittling a bit of time away downstairs.

The space comprises a gorgeous perimeter of three-tiered windows that flood the space with natural light and, later, the city’s twilight glow. Set along the glass are high-top, two-top, and four-top tables (along with some rather distinguished large party seating set in the corners closest to the outer courtyard). The middle of the restaurant is characterized by more rows of high-tops and some smart, free-standing, back-to-back banquettes that anchor as many as four two-tops. Two bars—one raw and the other wet—serve as natural focal points for all the action.

The former operates out of the corner of the dining room closest to the host stand and can seat eight or nine guests across two of three sides (one being reserved to facilitate service). The raised counter, which boasts an attractive seashell textured base, a grey quartz surface, and an elevated section trimmed with naval sketches, allows its diners to observe some of the kitchen’s work.

The latter bar is freestanding and fills the portion of the space closest to the corner of Randolph and Wacker, lending the restaurant a high degree of curb appeal. It seats something close to thirty people across all four of its sides and serves as a natural conduit for the tide of energy that flows in from the street. Sitting at this bar, which is rendered in burnished orange with a quartz countertop and brass accents, you can better marvel at the octopus sculpture. Above it hangs a ceiling of ribboned orange fabric with segments of varying height that fade into floor-to-ceiling curtains than run along select windows. The sum effect, accented by potted trees and hanging planters, is effortlessly breezy. It’s just the kind of trick that Kehoe Designs dreams of pulling off.

The room’s lighting is drawn from countless LED fixtures embedded in the ceiling alongside hanging lanterns and underlit surfaces. They impart soft, soothing rays that illuminate the tables while allowing for a moodier ambiance as the sun goes down. The flooring comprises a mix of rugs and tiling set onto a smooth stone base. Tabletops are rendered in wood while most of the seating features leather or fabric cushioning set on a wooden construction. The finishing touches come from an assortment of ceramics (placed atop empty surfaces), the odd chandelier, and glowing fish silhouettes set onto some of the walls.

While Gibsons Italia, Maple & Ash, and RPM Seafood each host a thriving bar scene, Bar Mar’s setting makes these establishments seem rather congested by comparison. For, while the counter seating underneath the octopus can grow crowded, the room’s other zones remain spacious. Guests may try their luck waiting for a spot at the bar, but the high-tops are just as appealing. They allow parties of a wide range of sizes to secure room for themselves without committing fully to a seated meal. By managing this overflow, the restaurant preserves the bar scene’s excitement while safeguarding the experience of those who came primarily to dine.

When it comes to menu offerings, Bar Mar delivers an experience that is almost entirely distinct from Bazaar Meat upstairs. The two properties share certain cocktails in common—contemporary versions of classics like the “Salt Air Margarita,” “Ultimate G&T,” and “Nitro-Caipirinha”—yet half of the selection remains totally unique. The drinks comprise categories like “Refreshing & Easy,” “Aperitifs & Spirit-Forward,” and “Adventurous Drinkers,” yet each offering you have sampled has struck you with its brightness and sense of overall balance.

Many feature the kind of molecular gastronomic flourishes you might find at barmini (Andrés’s D.C. “cocktail lab”) or, locally, at The Aviary. You’re talking things like an “hibiscus-rose-orange blossom aromatic cloud,” a “rosemary & cocoa aromatic cloud,” the aforementioned “salt air,” a “warm espuma,” and drinks that are “citric-enhanced” or “frozen tableside with liquid nitrogen.” Witnessing Bar Mar’s bartenders craft such a ceaseless stream of intricate drinks is a real pleasure. So, too, is having them (or your server) apply the finishing touches before your eyes.

Unlike The Aviary, where efficiency and profit have been prized above all else, Andrés’s concept retains all the charm of a conventional bar. Advanced techniques are not ensconced behind some cage in a corner of the room, but woven fluidly into the motions of the friendly faces that man the counter. “Smoke and mirrors” are not wielded in an effort to obscure bitter, boozy beverages with limited broad appeal. Instead, Andrés makes a great cocktail even better with a measured dash of whimsy. Imbibing at Bar Mar feels social and uplifting. The drinks are made to please and never come off as trying too hard. And the bartenders conjure them without any trace of pretension.

After a couple double “Nitro-Caipirinhas,” you start to wonder why you ever flocked to The Aviary in the first place. With Andrés’s entry into the market, the Alinea offshoot’s technical advantage starts to lose its luster, and the essential cynicism of the concept grows starker. Compared to Bar Mara, it’s a dark, cramped, and noisy space that has ignominiously severed the connection between the craft of bartending and its perceiver. It serves unpalatable, overpriced fare to conspicuous consumers and tourists that missed their chance at visiting Achatz’s “mothership.” It uses molecular gastronomy to flatter in place of possessing an actual personality—instead of touching on a shared nostalgia—which forms the very lifeblood of effectively harnessing Ferran Adrià’s techniques to begin with.

Andrés, through Bar Mar, offers Chicagoans a richer, fuller vision of how inventive cocktails can make for a memorable, but still distinctly human and soulful, evening. The drinks, perhaps, lack the particular level of interactivity that truly distinguishes The Aviary at its best. However, there’s no question of which space offers better views, value, flavors, and service. Bar Mar is a sneaky sort of “Aviary killer” for those who have long sworn off the sadistic Fulton Market establishment. Under the Spanish chef’s care, mind-bending mixology only forms the entry point for something much more.

That, of course, includes the food menu. Relative to the cocktails (and save for the “Croquetas de Pollo” and “Sloppy Joe”), there’s absolutely no crossover with Bazaar Meat here. Rather, Bar Mar takes inspiration from the categories of dishes offered upstairs and present a range of options grounded both in seafood and the lunch crowd it draws.

Downstairs, guests will find “Little Snacks” comprising ingredients like hamachi, tuna, smoked salmon, mussels, and caviar. They’ll find “Raw & Simple” plates like abalone with shiitake, a tiradito, and ceviches. The menu offers three kinds of dressed oysters (the bivalves being unavailable upstairs) along with salads, sandwiches, and a whole fried fish. The only meats offered, apart from ibérico ham, are a lone American wagyu skirt steak and a dish of “José’s Pulled Chicken.” It’s a bold move considering how well a steak sandwich or burger would probably sell, yet it affirms the downstairs restaurant’s distinct, thoughtfully restrained identity.

Based on one solitary but comprehensive meal, you have found that the quality of the fare at Bar Mar aligns with the standard set upstairs (just how high or low that standard is will have to wait for later). More importantly, relative to Pigtail, Bazaar Meat’s sister restaurant deserves respect. It represents a true expansion of Andrés’s brand into new territory, honoring Chicago with something more than other cities’ leftovers. Also, as an all-day concept, Bar Mar provides an accessible entry point to the pricier “Bazaar” experience while serving as an anchor for the neighborhood. Overall, this multidimensional character makes for one of the city’s most consequential openings in its own right.

After checking in with the hostess at Bar Mar and assembling your full party, the go-ahead is finally given to travel upstairs. That means sliding left of the host stand and entering a private bank of elevators inaccessible from the street. There, Andrés’s theming lapses, and you feel more like one of the Tower’s many lawyers reporting for work. Standing on the social distancing marker affixed to the ground, awash in sterile tones of metal and grey, the brief ride to the second floor feels like something of a reset. The buzz of the downstairs bar fades, and excitement builds for what José’s inner sanctum holds.

Those who have visited Maple & Ash or Gibsons Italia will be no strangers to such elevator rides. However, rather than packing multiple parties into the same car, Bazaar Meat makes use of three shafts to offer greater speed and privacy.

Nonetheless, both Andrés’s upstairs and downstairs properties demand that guests ride down to the lower level (home to Café by the River) in order to reach the bathrooms. It feels like quite a trek from your table, but the set of three elevators makes the process slightly more convenient. You need not climb a set of stairs or wait for a solitary car to arrive (as at Maple & Ash or RPM Seafood). The overall theming of the experience, once more, suffers. But sending people into the bowels of the Bank of America Tower helps maximize dining room space while totally shielding any congestion or other spillover from view. (You think of the lines that perpetually form for Bavette’s handful of single occupancy bathrooms).

However, when the elevator doors finally open on Bazaar Meat, a feeling of wonder quickly returns. First, you come face to face with another host stand that has been adorned with a woven tapestry set within its base. Its surface contains a lamp made of light red glass with an oversized shade, as well as a couple wagyu-related knickknacks (that serve as “proof” of the beef’s sourcing). Behind the stand, most strikingly, sits dozens of red-toned china plates set within individual compartments along a wall of white cabinetry. Being nearly (but not quite) identical, their effect is dizzying. The perfectly arranged plateware prefaces a meal that blurs the line between the familiar and the totally novel.

Before you can dwell too much on that symbolism, the hostesses greet your party and whisk you down the narrow corridor that leads into the dining room proper. Along the way, you pass several rows of wine fridges, stacks of Andrés’s cookbooks, and a comprehensive selection of dry-aging beef set within its own array of glowing refrigeration.

Upon reaching the threshold of Bazaar Meat’s sole, sprawling space, you are flanked by the kitchen. To your left stands a cold station (also known as the “Meat Bar”) that is distinguished by hanging hunks of ibérico ham alongside various other meats and cheese. To your right stretches a longer pass that plays home to all of the restaurant’s hot cooking. That kitchen, primarily, is distinguished by its custom IPSOR oven built in Barcelona. The hulking piece of equipment runs alongside the adjustable grills used to sear guests’ steaks. Meanwhile, a refrigerated case set into the corner of the kitchen counter (closest to the entrance) showcases an additional selection of meat.

Venturing forward, you find a front seating area split into two zones. Opposite the cold station stands a mixture of two-tops, four-tops, and the odd six-top beneath a shimmering light fixture made from strands of circular red glass. The corollary of this space, located across from the hot kitchen, is a bit larger and more plush. It features two-tops and four-tops with extensive banquette seating and a sprawling rug patterned after traditional kilim motifs. There’s a similar light fixture overhead, as well some metal fixtures that dangle lampshades over the banquette.

This latter area does not only abut the hot kitchen, but is framed by Bazaar Meat’s upstairs bar too. That surface, which seats seven, is set against windows that look out onto Wacker. An upper deck of bookshelves lines the ceiling above it, lending the bar—which you understand does not accept walk-ins—a sophisticated feel.

A narrow pathway bisects the two front seating areas and leads to a single, rear stretch of tables best positioned to appreciate views looking across Randolph and down the river. The most luxurious of these are the three floral-patterned horseshoe booths oriented directly towards the windows. However, a corner table (located at the far end of the bar and behind the wine station), offers comfort and seclusion for larger parties. It might be the most exclusive table of its kind in the entire city. The banquettes and four-tops closest to the windows, too, are rather nice. Not every guest at such tables will get to enjoy the view, yet the privacy (relative to the front seating areas) is worth it.

Other aesthetic elements of note include ceilings rendered in a pattern of pebbled stone and set within a coffered black frame with brass accents. These panels, which subtly glow thanks to LED strips, define the bulk of the overhead space (apart from the two aforementioned light fixtures made of red glass).

The restaurant’s tabletops are largely done in a dark tone of wood with brassy metallic strips running along their perimeter. However, just a couple, closest to the cold station, feature quartz countertops with a wooden trim. (White tablecloths, interestingly enough, were placed over tables during Bazaar Meat’s December debut but were eventually—and smartly—excised). The chairs set within the dining room, as well as the banquettes, largely feature red tones with a velvety texture. However, a set of four-tops closest to the bar display a plaid pattern, and a set of six-tops near the cold station are given chairs made from simple black leather.

The room’s accents are derived from black columns (each with a riveted brass base), red velvet pillows (set within booths and banquettes), a couple chandeliers (placed at the corner tables), a couple small trees (set in large planters), a few shrubs (set in small planters on top of counters), and a large brass lantern (positioned towards the end of the path that leads to the rear dining area). Lastly, above and along the kitchen areas hangs cabinetry illuminated in a yellow tone and filled alternatingly with glassware or stacked wood. The cabinets of the cold station feature books (like the bar) and a series of six vintage Spanish advertisements for food products.

Overall, Bazaar Meat’s dining room sounds like a hodgepodge: glass, wood, stone, ceramic, metal, leather, velvet, and woven materials in tones of red, brass, and black with an assortment of patterns and greenery woven throughout. But the mass of aesthetic elements are, in fact, beautifully composed. No one aspect of the design screams for attention; rather, they work together to build an environment brimming with pleasing details. While there are too many to effectively bound during all the excitement of the actual meal, that seems to be the point.

Bazaar Meat constructs an ambiance filled with evocative, mixed influences that reflect the menu’s endless possibilities. They reflect, at core, the ephemeral and mysterious association one draws from its namesake marketplaces. There’s certainly a “wow factor” when you enter, yet the restaurant, nonetheless, feels intimate. Noise levels are well managed, and each guest’s vision is naturally drawn towards the windows that span the room’s three sides (rather than at each other). Thus, the space actually surpasses the Las Vegas original by combining its distinct style with a sense of the city. You get the sense that you are dining in an eclectic, exclusive jewel box floating over the river. Compared to the relatively austere décor at Gibsons Italia and RPM Seafood, it seems positively more luxurious.

Upon nestling into its seats, your party is quickly greeted by a busser, who asks your choice of water. The server arrives not long after, depositing weighty, tri-fold menus and noting your request for the wine list. In short order, the sommelier swings by a places the finely bound book before you.

The beverage program at Bazaar Meat begins with what is listed on the food menu. That includes a range of cocktails that are unique from Bar Mar’s selection below, most notably two $32 numbers made from Del Maguey’s ibérico mezcal and another, priced at $23, made with Torres brandy and Old Forester rye that has been “rested in goat leather.” While the “Refreshing & Easy” libations remain, including a “Plantain Scotch Highball” made from whiskies “sous-vided with coconut and plantains,” the spirit-forward options are well-suited to the upstairs restaurant’s beefier fare.

Of the half dozen beers listed on menu, all—notably—are made in Illinois. The selection comprises draft options from Metropolitan Brewing and Casa Humilde alongside bottles from Whiner Beer Company, Conrad Seipp Brewing Company, Off Color Brewing, and Half Acre Beer Company. It goes without saying that Andrés’s support of a diverse array of local artisans (within such a luxurious, globetrotting concept) is a great way to endear himself to the native population.

Bazaar Meat’s wines by the glass selection is where things start to get interesting. For any concept that deals so concertedly in steak is sure to attract customers looking to indulge in vinous delights at every price point. To that end, BTG forms the tip of the spear for the overall program. It signals, immediately, if diners should expect to be squeezed on account of their interest in drinking wine or if their oenophilia, in fact, will be celebrated.

The first of six categories comprises three kinds of Sherry: a Manzanilla ($10), a Fino ($18), and an Amontillado ($17) each offered in a 2.5 oz. pour. Though these fortified wines are often alien to American palates, they are important expressions of Andrés’s culture and pair wonderfully with the chef’s eclectic fare. The Manzanilla, for instance, goes well with all manner of fish and seafood. The Fino forms a fitting pairing with traditional tapas, fried foods, charcuterie, and cheese. Meanwhile, the Amontillado can stand up to mushrooms, poultry, and even lighter expressions of red meat.

The ”Sparkling” category offers guests a more familiar pleasure, and it does so while delivering value too. At the more affordable end of the spectrum, the restaurant offers a pair of Xarel-lo-based sparkling wines from legendary Spanish producer Raventós i Blanc. One, the 2016 “Cuvée José Andrés” ($16) is blended particularly for the chef’s restaurants. The other, a 2018 “Nit” Rosé ($15), is well-suited to those who desire some of the color and weight of red wine (Monastrell in this case) in their bubbly.

Diners who decidedly crave Champagne will find two multi-vintage options priced a bit higher than the Spanish sparklers: Vincent Couche’s “Eclipsia” ($25) and Louis Nicaise’s Premier Cru Brut Rosé ($29). These selections, in a sense, mirror the two Raventós offerings. They are joined by a super-premium pour: Henri Goutorbe’s “Special Club” Grand Cru Brut ($50) from the excellent 2008 vintage. All three of these Champagnes are Pinot Noir-based, which seems excessive until you remember that Bazaar Meat lacks the same raw seafood options (like oysters) as Bar Mar. This stylistic decision also means that the wines (especially the Goutorbe) are more approachable too.

The “White” category is patterned in a similar manner. There are two Spanish whites: a crisp, salty Albariño from Rias Baixas ($20) and a richer, bolder Godello ($16) characterized by flavors of granite. And they are joined by a balanced, medium-bodied, and attractively priced Grillo from Sicily ($15).

But more traditionally beloved varieties are in no way ignored. There’s Riesling from Schloss Gobelsburg ($15), “Estate Fumé Blanc” (Sauvignon Blanc) from Grgich Hills ($16), and Chardonnays from France—Paquet’s 2019 Saint-Véran ($17)—as well as Napa Valley’s Heitz Cellar ($25).

The “Still Rosé” section of Bazaar Meat’s BTG selection is a rather simple one. It comprises a single Garnacha-based wine from Navarra in Spain’s Basque Country: Itxas Harri’s 2020 “Ŕoxa” ($14). Though unfamiliar to you, this old-vine rosé from “well-drained gravelly limestone soils” offers a “dry,” “refreshing,” and “bright” drinking experience that aims at just what a broad base of consumers have come to expect from this category. The wine’s pricing and adaptability across the menu make it an appealing option.

Red wines, understandably, make up the bulk of the restaurant’s BTG selection. From Spain, guests will find Mencía from Raúl Pérez ($14), Rioja from López de Heredia ($18), and Priorat (a blend predominantly made of Garnacha, Syrah, and Merlot) from Vall Llach ($17). The sole Italian selection is a Nebbiolo d’Alba from De Forville ($18) that, sourced from a hilltop located between Barbaresco and Barolo, offers the class of those famous appellations at a more accessible price.

When it comes to France, the array of options leaves no stone unturned. There’s a Chinon from Charles Joguet ($18), Bourgogne from Robert Groffier ($40), Bordeaux from Château Peybonhomme ($16) and Duc des Nauves ($19), and Syrah from Vincent Paris ($17). Of this rather representative collection, the two Bordeaux are particularly interesting due to the fact that the former is made only from Malbec and Cabernet Franc and the latter predominantly from Merlot. Both, importantly, are unoaked: offering an approachable drinking experience in a forbidding genre.

While the Groffier, despite being a “mere” Bourgogne, ranks as the second highest priced BTG, its grapes are actually sourced from Flagey-Échézeaux and Morey-Saint-Denis. This means it sneakily offers a taste of top-tier Burgundy from a renowned producer and great vintage (2018) for a nice price. The premium it commands must also be weighed against the rather affordable Presqu’ile Pinot Noir ($16) from Santa Barbara. It is one of two domestic reds alongside a 2016 Long Meadow Ranch Cabernet Sauvignon ($26) sourced from Mayacamas and Rutherford fruit that offers a “friendly,” “accessible,” and “modern” expression of the steakhouse diner’s favorite grape.

The final category, “Non-Alcoholic,” is defined solely by Eric Bordelet’s “Perlant” Jus de Pommes a Sydre ($12). The producer’s alcoholic pear cider has featured on Oriole “2.0’s” beverage pairing, and you find his products to be rather tasty from the perspective of a wine drinker. The non-alcoholic, lightly sparkling apple juice—sourced from “6 varieties of organic bitter-sharp, bitter-sweet, and sour heritage cider apples”—promises a precise, refreshing experience presented with the same class as the alcoholic BTG offerings. It’s the kind of savvy selection that demonstrates the category was not treated as an afterthought.

Overall, you like the restaurant’s BTG list for it blend of popular varieties, well-known producers, and just a couple oddballs. The overarching focus on the Old World, alongside four notable selections from California, feels both focused and luxurious. Offering approachable, top-value wines from France (and even Spain or Italy) always presents a challenge, but Bazaar Meat’s wine director, Christian Shaum, has risen to the challenge. And he has demonstrated the fortitude to replace wines that have sold out—like a 2019 Raúl Pérez Albariño and a 2016 Hanzell Chardonnay—with comparable options. It makes the Australian, Argentinian, and New Zealandic wines that litter Maple & Ash and RPM Seafood’s lists seem like cop outs.

That being said, Bazaar Meat’s bottle list is where things get really interesting. Over the past few years, pricing for blue chip wines (particularly from Burgundy and Champagne) has skyrocketed. That, plus a general dearth of back vintages within the Chicago market, has made launching a program that offers either top producers or the kind of accessibility that comes with age a tall order. Until a new restaurant has had a few years to settle in, they tend to remain shackled to current release products from mid-range producers (the very same seen all across town). Though you have long celebrated establishments that look to auction houses and sellers like Ventoux Fine Wine to backfill their lists, few of the city’s wine professionals are empowered—or motivated—to do so.

However, you are pleased to say that Bazaar Meat opened with one of the most impressive bottle lists you have seen in Chicago to date. The selection—though continually changing as wines come on and off the features best in class values, back vintages, top producers, esoteric offerings, large formats, and veritable treasures galore.

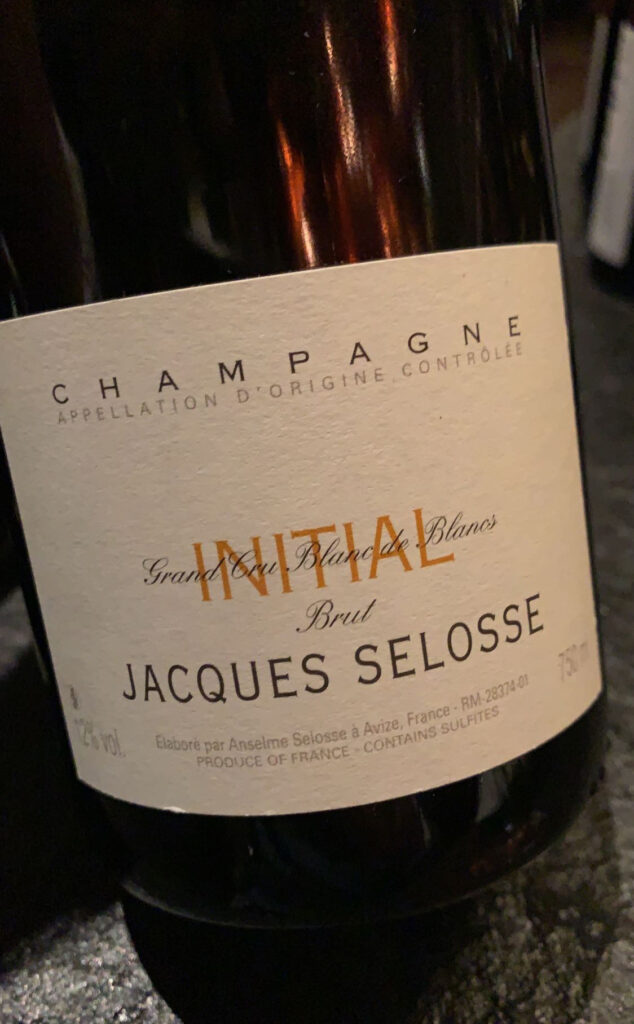

These have included Champagnes from Bérêche (“Reserve”), Bollinger (2002 “La Grande Année), Dom Pérignon (2010 and 1975 “Oenothèque Commande Especiale” millésimes), Egly-Ouriet (2012 millésime), Jacques Selosse (“Initial” and 2008 “Millésime”), Krug (1988 and 1995 “Collection” releases), Philipponnat (2004, 2006, and 2007 “Clos des Goisses”), Pierre Peters (2014 “Chétellions”), and Roger Coulon (2012 Blanc de Noirs “Millésime”).

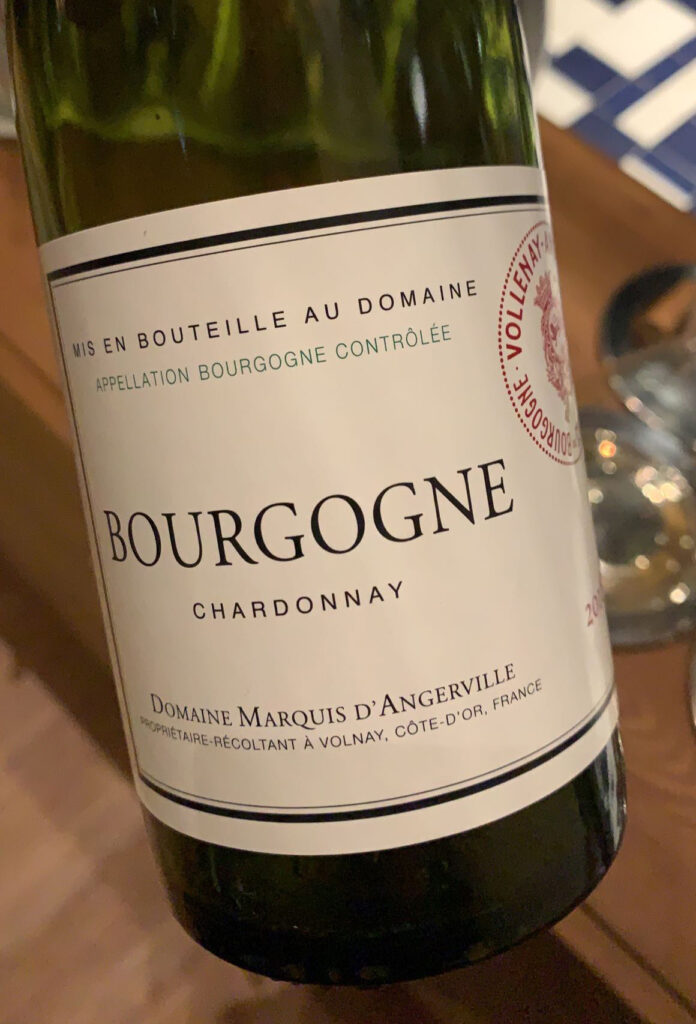

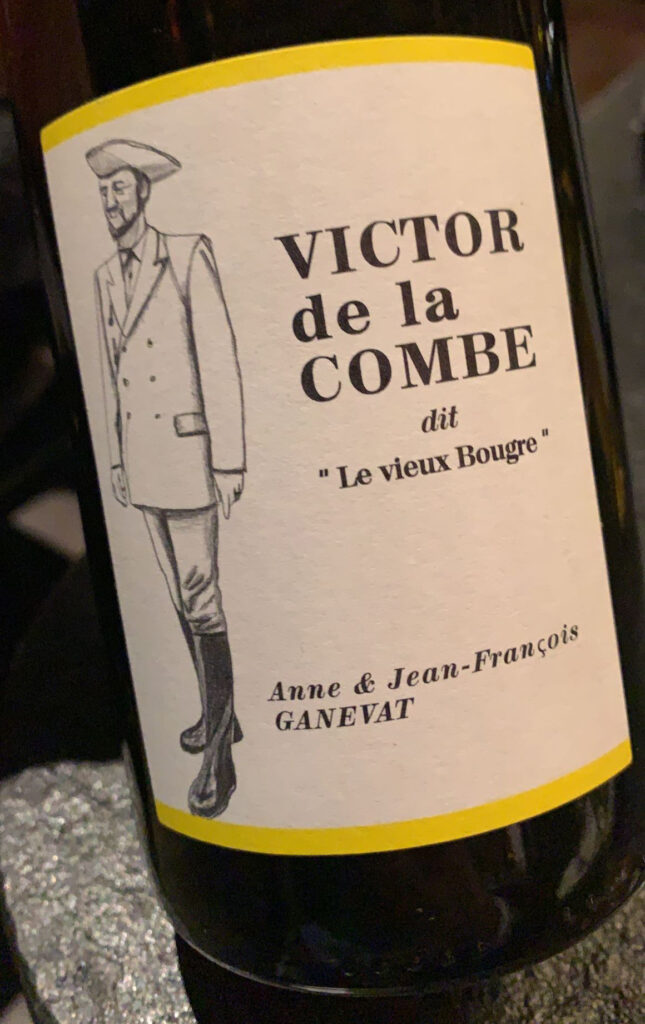

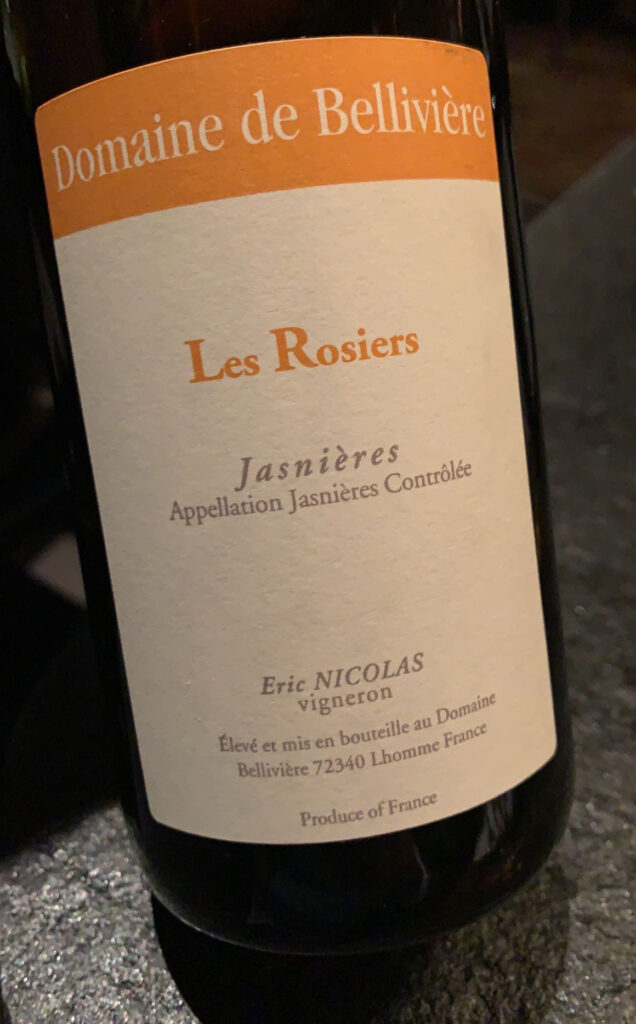

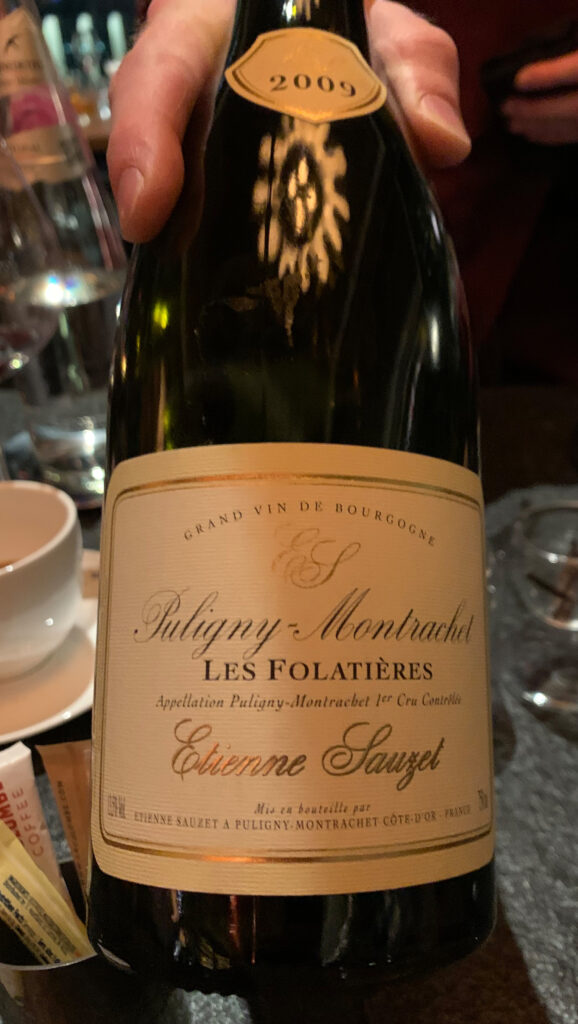

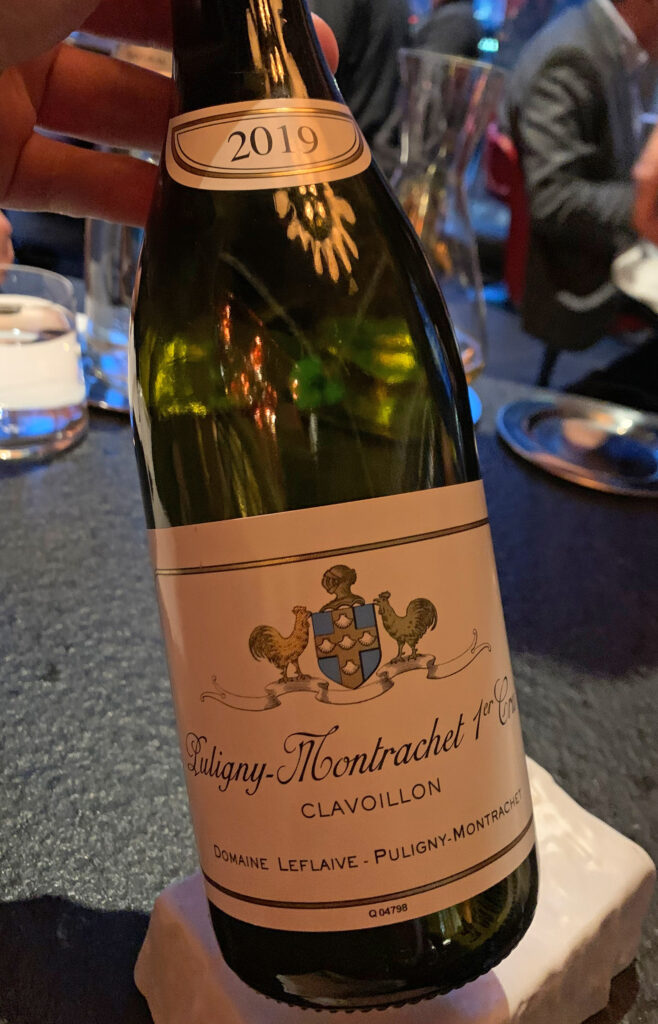

Notable white wine producers have included Emilio Rojo, López de Heredia (the 2001 and 2010 “Viña Tondonias”), Raúl Pérez (“Sketch”), and Terroir Al Límit from Spain; Coche-Dury (2018 Meursault), Darviot-Perrin (2016 “Les Perrières”) De Moor, Jobard, Lamy, Ramonet (2016 “Les Chaumees”), Raveneau (2019 “Montée de Tonnerre” and 2016 “Valmur”), Roulot (2015 Meursault), and Sauzet (2009 “Les Folatières”) from Burgundy; Domaine de Bellivière, Domaine du Pelican, Cotat (François and Pascal), Ganevat (“Victor de la Combe”), Guiberteau (2015 and 2018 Brézé), Huet, Joly (2017 “Coulée de Serrant”), and Vacheron from the rest of France; Benanti, Miani, and Paolo Bea from Italy; Dönnhoff, Emrich-Schönleber, Karthäuserhof, Keller, Maximin Grünhaüser, Peter Lauer, and Weiser-Kuenstler from Germany; Alzinger, Hirsch, Knoll, Nikolaihof, Pichler (F.X. and Rudi), Prager, and Veyder-Malberg from Austria; and Evening Land, Kistler, Kongsgaard, Littorai, and Sandhi from the United States.

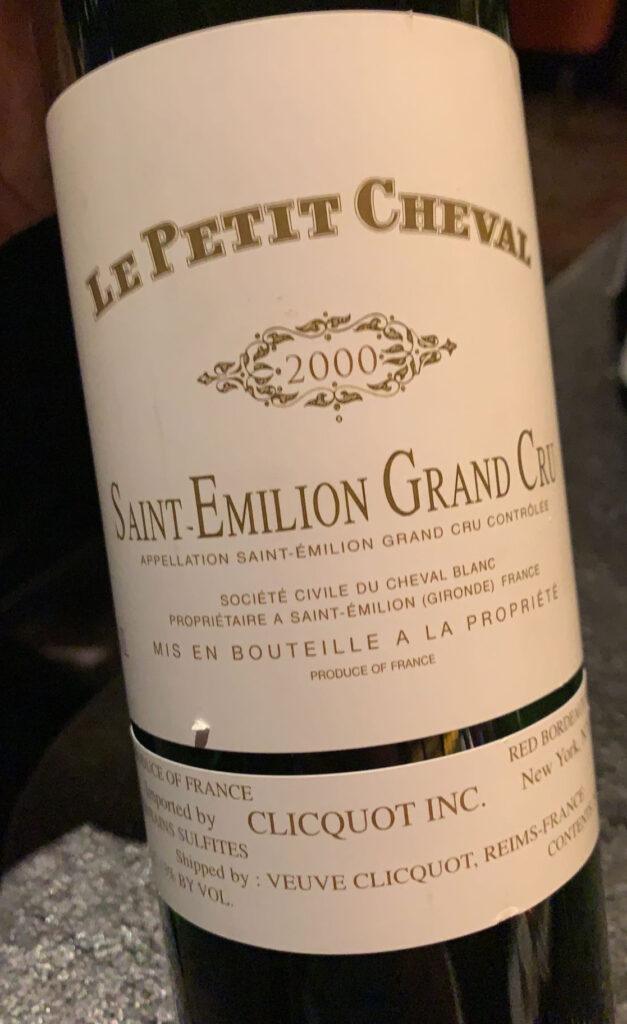

Notable red wine producers have included Clos Erasmus, CVNE, Descendientes de J. Palacios, Faustino, López de Heredia, Marqués de Murrieta, Pingus, and Vega Sicilia from Spain; Cecile Tremblay (2015 “La Fontaine”), d’Angerville, Dominique Lafon, Dugat-Py, Génot-Boulanger (2002 “Les Combes”), Hubert Lignier, Jean Grivot (2009 “Les Roncières”), Joseph Roty, Le Moine (2013 Griotte-Chambertin), Pierre Girardin, Robert Chevillon, and Taupenot-Merme from Burgundy; Bertrand, Breton, Foillard, and Lapierre (“Sans Souf”) from Beaujolais; Clos Rougeard, Thierry Germain, and Guiberteau from the Loire; Allemand, Beaucastel (2001 and 2004), Clape, Guigal, Jaboulet (1999 and 2006 “La Chapelle”), Jamet, Ogier, Pegau (2006), Rayas (2009 and 2010), and Rostaing from the Rhône; Calon-Ségur (1989), Cheval Blanc (2000 “Le Petit Cheval”), Cos d’Estournel (1998 and 2004), Figeac (2009), Haut-Brion (1986), Lafite (2000), La Fleur-Petrus (2008), Léoville Barton (1990), Montrose, Pape Clement (1995), Pontet-Canet (2005), Rauzan-Ségla (1995 and 2005), and Troplong-Mondot (1998 and 2009) from Bordeaux; Ar.Pe.Pe, Bartolo Mascarello, Biondi-Santi, Dal Forno Romano, Emidio Pepe, Gaja (1997 and 2005), Giacomo Conterno, Giuseppe Mascarello (1971), Montevertine, Ornellaia (2007), Poggio di Sotto, Vietti, and Quintarelli from Italy; and Araujo, Bond (2011 “Melbury”), Bryant Family, Château Montelena (2007 and 2013), Corison, Dominus (2011), Diamond Creek, Domaine de la Côte, Dunn, Evening Land, Eyrie Vineyards, Heitz, Hundred Acre, Joseph Phelps (1996 “Bacchus” and 1999 “Insignia”), Larkmead, Littorai, Mayacamas (2005), Philip Togni, Ridge, Shafer, and Silver Oak (1992 and 1993) from the United States.

Bazaar Meat’s “Large Format” section is a pleasant surprise given how limited such selections are throughout most of the city. Notable bottles of champagne have included magnums of Bérêche (“Reflet d’Antan”), Billecart-Salmon (Rosé), Georges Laval (“Cumières”), Laurent-Perrier (Rosé), and Pierre Péters (2011 “Les Chétillons”) alongside a double magnum of Pierre Péters “Cuvée de Réserve.” Magnums of white have included Dönnhoff (2019 “Estate” and “Schlossböckelheimer Felsenberg”), F.X. Pichler (2018 “Dürnsteiner Kellerberg” Grüner Veltliner), J.J. Prüm (2019 Wehlener Sonnenuhr Kabinett), Rollin (2016 Corton-Charlemagne), and Roulot (2015 “Le Cailleret”). Meanwhile, magnums of red have included Alex Foillard, Bruno Giacosa (1999 “Le Rocche del Falletto”), Cavalotto, Cayuse, Château Simone, d’Angerville (2006 “Champans”), de Vogüé (1990 “Bonnes Mares”), Guy Breton, Heitz (2001 “Bella Oaks”), López de Heredia (2004, 2005, and 2006 “Viña Tondonia”), Montevertine (1996 “Le Pergole Torte”), Ornellaia, Pierre Girardin (2018 Volnay), Haut-Bailly (2010), and Pontet-Canet (1995).

Lastly, the restaurant’s “Dessert Wines” have included Sauternes from Caillou (2005), d’Yquem (2007) and Rieussec (2011); Barsac from Coutet (1998 and 2010); Alsatian stickies from Huet (2002 and 2020) and Trimbach (1994 Gewurtztraminer “Sélection de Grains Nobles” and 1997 “Clos Ste. Hune” Vendanges Tardives); Port from Niepoorte (2004 “Colheita Tawny”) and Quinta do Infantado (2013); Madeira from Broadbent (1997 “Malmsey”) and D’Oliveiras (1988 “Frasqueira”); and an eclectic “Around the World” assortment featuring Keller, Kracher, Maculan, Royal Tokaji, and Schäfer-Frölich.

While this dizzying array of producers, vineyards, and vintages might seem overwhelming, it stands as a laundry list of quality and affirms Chicago’s capacity to appreciate the world’s finest wines. If anything, you would like to see the range of rosé options expanded beyond the current five (four from Provence, one from Spain). But Bazaar Meat’s bottle list is clearly a product of both passion and discernment. It does not present a mausoleum of impressive names that the wider public will never drink, but invites imbibers across all spending categories to enjoy themselves.

That, of course, is enabled by rather modest markups—a laudable policy that Gibsons Restaurant Group has maintained across all of its properties. (For it would be all too easy to squeeze customers at Gibsons Italia and Bazaar Meat on account of the view alone).

For example, the restaurant’s Jacques Selosse “Initial” ($365) is competitively priced relative to Cherry Circle Room ($330), Kyōten ($429), RPM Seafood ($444), and Maple & Ash ($525). The 2010 Dom Pérignon ($425) undercuts RPM Seafood ($565). The 2019 Raúl Pérez “Sketch” ($121) is significantly less than the bottles at Joe’s ($195) and Maple & Ash ($250). The 2015 Domaine Roulot Meursault ($490) costs significantly less than the same vintage at RPM Seafood ($650). And the 1986 Château Haut-Brion ($1430) is priced far lower than the bottles at RPM Steak ($1746) and Maple & Ash ($2300)

However, in some cases, this doesn’t hold true. The 2017 Domaine Raveneau “Valmur” ($1,400), for example, costs more than the bottles at Maple & Ash ($1,025) and RPM Seafood ($1,111). And the 2019 “Flor de Pingus” ($235) is priced a bit over the same wine at Maple & Ash ($230).

Nonetheless, you enjoy seeing such strong downward pressure applied towards the city’s wine pricing. Bazaar Meat’s program, even if it does not offer the absolute best value on every bottle, clearly makes an effort to do so. This philosophy, if maintained over the long hall, will quickly establish the restaurant as one of Chicago’s best havens for wine appreciation. Conceptually, Andrés’s wide array of small plates naturally enrich the enjoyment of a broad range of styles. At the same time, the restaurant’s emphasis on beef ensures that the finest reds can truly shine. Meanwhile, a $50 corkage fee (with a limit of two 750 mL bottles) is fairly priced relative to competing establishments and the generous pricing seen across the list.

Finally, while you find the standard set by the RPM restaurants, Hogsalt properties, Gibsons Italia, and Maple & Ash to be laudable, you think Bazaar Meat really distinguishes itself when it comes to wine service. Perhaps it has something to do with the intimacy of Andrés’s space and the cohesion of the team of three sommeliers that conducts things upstairs and down. But there is a flair and confidence to the vinous stewardship that you find highly charming. It makes the experience of selecting a bottle from the excellent list feel even more rewarding, and it’s buttressed by a wealth of knowledge indicative of real ownership over the selection.

The wine team demonstrates a clear vision—via slow-oxygenation, decanting, or double decanting—of how to bring each bottle to its apotheosis. Thus, you do not simply pay for the wine, but for expertise that will engineer a superlative drinking experience. This high standard of service is rarely seen outside of fine dining, and it is a credit to the seriousness with which the restaurant approaches its program. Most importantly, this enthusiasm exists without the slightest trace of snobbery. Bacchus would be proud.

With the beverage order settled, you can finally turn your attention towards Bazaar Meat’s rather expansive menu. While certain dishes—like fish, lobster, suckling pig, and steak—are large-format endeavors designed to feed several people, most selections fit into the tapas mold. Each of these small plates delivers a couple perfect bites per person for a standard party size of four. Thus, the sky is really the limit when appending such items to your order.

Discounting dishes that come with sides of bread, you can sample almost as many options as you want from the introductory categories without spoiling the main event. However, given the prevalence of certain totemic luxury ingredients across the preparations, price and propriety may form the limiting factors—and time too. You have found that a full-fledged, no holds barred Bazaar Meat experience clocks in somewhere between three and a half to four hours. That not only equals, but exceeds the commitment at most of Chicago’s fine dining establishments (Alinea’s “most intimate, immersive, and cutting edge” kitchen table, for example, seats parties at 5 PM and 8:45 PM).

Yet time spent in Andrés’s care, under the auspices of a Gibsons-inflected staff, flows by effortlessly. Save for certain niceties of synchronization and elaboration, the service equals the standard set in the city’s Michelin-starred dining rooms. The captains are well-versed in describing the menu’s more exotic ingredients and offering their general suggestions as to the size and scope that make for a representative order. (Of course, when you double or triple that number of dishes, they record the entirety without even missing a beat).

The overall mood among the staff, meanwhile, is cheery and energetic. Yes, the cadre lacks some of the gravitas of the jacketed servers that work Italia or Rush Street, but their duties are different. Rather than staging three or four distinct courses of seafood, salad, pasta, and steak, Bazaar Meat’s crew might drop twenty different dishes on the table during the length of an evening. Staggering each of these items and describing them to just the right level of detail—as patrons, no doubt, continue to enjoy what has already been put before them—demands a high degree of sensitivity and an unerring focus.

Upon placing your order, you have witnessed how each server has walked over to the sommelier station to consult with their beverage counterparts on how to best structure the meal. For, while the menu’s categories display a certain progression, all but the steaks are broadly interchangeable. Thus, the wines that Shaum has ensured are showing at their peak can, with your server’s intervention, be served with the fare they are most particularly suited to. This kind of orchestration is both rewarding (as an oenophile) and engaging (as a diner). Such an advanced practice of pairing amounts to something like a bespoke tasting menu that draws totally unique connections, forged in wine, between parts of the menu that might not naturally be mixed and matched.

Once that plan is set and the meal actually begins, you need do no more than sit back and enjoy the show. Your captain, as well as the sommeliers, remain attentive throughout the duration of dinner. However, the delegation of essential tasks to a whole range of bussers, food runners, and even managers is where Bazaar Meat shines. The restaurant operates with an overarching team spirit—a sense of cohesion and shared ownership—that ensures no plate or drink ever lays empty for long. The full range of the staff, from top to bottom, is empowered to deliver anything and everything a customer could ask for. That, you think, is the “Gibsons touch,” and you can see why Andrés found the partnership so appealing.

In practice, the collaboration ensures that the Spanish chef’s imaginative food is intelligently described, expertly prepared, artfully presented, and perfectly paced to ensure an evening of ultimate comfort and unparalleled decadence without a single rough edge. In this manner—where every want is fulfilled before you can even think of it—service ensures that guests can enjoy each other’s company, the ambiance, and the view as a superlative gastronomic experience unfolds effortlessly before them. Such a feeling, you think, transcends even the highest expressions of the classic “steakhouse” form.

But such a case is best made by evaluating the comestibles themselves.

Bazaar Meat’s menu begins with a category titled “Little Snacks” that correlates with the “Snacks” section of the temporary “The Bazaar Experience.” Since there is significant overlap between the two sets, you will combine them for the purposes of this article while also demarcating the four items that are unique to the latter selection.

Starting off, the “Bagels & Lox Cone” ($6 per each) is reminiscent of Thomas Keller’s famous salmon tartare cornets from The French Laundry. However, while that preparation combines salmon tartare and red onion crème fraîche in a black sesame seed-studded twirl, Andrés’s iteration is filled with dill cream cheese then topped with salmon roe and a few of the same seeds (which, of course, feature in a classic “everything bagel” seasoning).

Though perhaps lacking the delicacy of Keller’s three-Michelin-starred amuse-bouche, Bazaar Meat’s cone makes for an ethereal, enjoyable start to the meal. The bites arrive neatly tucked into a wooden holder that facilitates their grasping while preserving their brittle structure. On entry, the orbs of roe caress the palate before popping alongside the crunch of the sesame seeds. The briny, nutty combination is cushioned by the sour, anisey-sweet cheese and punctuated by the crackle of the cone’s shell. Everything combines on the tongue for an instant before disappearing and leaving you with a lingering finish reminiscent (though only slightly) of the titular bagel.

Whether or not the snack truly mimics its namesake, it is technically sound and appealingly playful. The cone, which is always among the first items to arrive at the table, forms a dream pairing with any sparkling or white wine.

The “Cotton Candy Foie Gras” ($8 per each) taps into a similar kind of nostalgia and succeeds to an even greater degree. The bite arrives attached to a wooden stick set into the same kind of tabletop holder. The cloud of spun sugar is immediately recognizable, yet it hides a small morsel of chilled foie gras mousse that has been coated in crispy amaranth.

With one bite, the cotton candy evaporates and your tongue strikes the duck liver. The layer of sugar combines with the crunch of the amaranth and envelops the cold mousse. As it melts on the palate, the foie gras unleashes a rich, buttery texture with a refined meaty flavor that becomes absolutely transfixing via the sweet-nutty supporting notes. The whole morsel disappears in a flash but leaves a finish of impressive length and purity. The bite ranks among the very finest preparations of foie gras you have ever tasted—and it’s just the kind to make a believer out of the luxurious liver’s skeptics. Within Chicago, you think only Oriole “2.0’s” delectable version can compare.

Bazaar Meat’s “Marinated ‘Ferran Adrià’ Liquid Olive” ($15) is a classic totem of molecular gastronomy that Andrés describes in glowing terms: “this will change your life!” The Spanish chef, of course, worked at elBulli for three years and is well-equipped to present his take on one of the master’s most legendary recipes.

Whereas the original technique, in a fine dining setting, demanded a delicate tableside plating of the fragile spherified olives, Andrés has concocted a version that preserves the dish’s textural novelty with a lot less fuss. Bazaar Meat’s “modern and traditional” iteration arrives neatly set on an assortment of spoons. Upon reaching your palate, what seems to be a firm orb of green olive gives way immediately and turns to liquid. It imparts a pristine, nutty flavor accented with a tangy-sweet bite of piparra pepper. While the visual trick is not rendered as well as Adrià’s original, the overall sensation remains sound. The dish stands as an accessible representation of the specification technique and a reverent tip of the cap to Andrés’s old boss.

By comparison, “José’s Taco” ($16 for 2) is an indulgence in just what the Spanish chef—himself—loves. As far as luxury totemic ingredients go, the dish represents just the kind of hodgepodge that hack chefs use to charm the conspicuous consumption crowd. But Andrés, as far as you know, has been serving the item for at least a decade, and you think that fact servers to grandfather the preparation as more of a “classic” than a cynical, more contemporary ploy.

“José’s Taco” comprises jamón ibérico de bellota (produced from pigs whose diet, in the period before processing, consists entirely of acorns), Osetra caviar, and a few flakes of gold leaf. However, on “The Bazaar Experience” menu, the bite features an additional layer of nori (or dried seaweed).

Both versions are defined by the interplay of rich, deeply nutty ham with the buttery, also quite nutty flavor of the roe. And, texturally, the slick sheen of the thinly-sliced ibérico does a good job of cushioning—then melding with—the delicate caviar. The seaweed component, when present, makes the bite a bit easier to grasp. It helps absorb the ham’s melting fat and adds a salty, briny character that matches the Osetra.

“José’s Taco” is a fun, frivolous bite priced well enough to appeal to diners who might not indulge in the restaurant’s full-fledged caviar service or order an extensive amount of the prized jamón. The dish does not offer a particularly intense, persistence, or life-altering expression of its luxury totems. Yet it imbues them with a sense of playfulness and value that effectively demystifies them for a wider audience. That, really, is what Andrés’s cooking is all about.

The ”Super-Giant Pork-Skin Chicharrón” ($12) immediately calls The Aviary’s “Giant Crispy Pork Skin” ($17) to mind. However, while the latter dish is deposited at tables in its towering glory (leading to an obnoxious amount of salt and vinegar spice coating the table), the former benefits from a bit of tableside preparation. Diners witness the oversized pork skin—peeking out of a paper wrapping—being wheeled over. The server places a metal bowl before you on the table then goes about smacking the chicharrón with a mallet to yield more manageable (but still plenty large) pieces. They cleanly slide it all into the bowl then leave you with a Greek yogurt-based sauce for dipping.

Texturally, Bazaar Meat’s crispy pork skin equals that seen at The Aviary. It breaks apart cleanly and offers a puffed, crisped consistency that shatters nicely between your teeth. With regard to seasoning, you prefer the savory depth of Andrés’s chosen za’atar spice blend to the all-too-aggressive salt and vinegar used by the birdcage. (But, hey, how else are they going to match the over-the-top booziness of their drinks?) The Greek yogurt dipping sauce, topped with olive oil and a bit more of the za’atar, provides a perfect foil. It makes for a complete bite that is crunchy, nutty, faintly herbaceous, and tangy in turn. Though the portion seems sizeable, the chicharrón disappears quickly. It’s an engaging shared snack and a significantly greater value than the version Alinea Group offers.

Andrés’s “Croquetas de Pollo” ($12) represent one of the chef’s most direct engagements with a classic dish of Spanish cuisine. Traditionally, the “miniature fried savory patties” (likened to arancini and salt cod fritters) are bound with a béchamel-like sauce before being coated in breadcrumbs and dropped into hot olive oil. Bazaar Meat’s version, described as “chicken-béchamel fritters,” seems to be a rather faithful take on the recipe.

The dish arrives in a custom glass vessel styled after a chicken (complete with red-tinted comb accents). The croquetas themselves are of a medium size and sit—about a half dozen per order—stacked within a paper wrapper. Impressively, they do not scald your tongue when you dive in right away. Rather, the crisp crumb coating yields to a warm, pleasantly creamy interior laced with shreds of chicken.

Overall, the croquette does a nice job of holding its structure across several bites. Its flavor is rich, though not overly so, and unblemished by any interloping ingredients. The sensation, thus, is straightforward in its meaty, comforting, stick-to-your-ribs quality. This reflects Andrés’s intention to respect the traditional recipe while mastering its execution and offering it to American diners in an attractive way. The dish is also one of just a few that are offered downstairs at Bar Mar, where you think it forms a superlative drinking snack alongside so many seafood options.

“Patatas Bravas” ($10) represent another canonical Spanish recipe that Andrés has embraced for Bazaar Meat’s menu. Traditionally, the dish comprises chunks of potato that are fried in olive oil then served with a salsa brava (made from tomato paste, sherry vinegar, and pimentón) and an aioli. And the chef, once more, seems to respect the classic recipe by offering a preparation described as “fried potatoes, spicy tomato sauce, [and] alioli.”

Yet, once the plate arrives, it becomes clear that Andrés had a little fun with the presentation. Rather than an assortment of potato chunks, guests receive one singular fried potato in the shape of a bull’s head (or, should you say, the Bulls’ logo). (The version of the dish served at Bazaar Meat in Las Vegas, it should be noted, is characterized by many rectangular pieces. That served at Bar Mar—and titled “Tater Tots”—takes the shape of three fish).

Inspiration aside, the bull-shaped serving is like the crispiest hash brown patty you have ever experienced. It outdoes McDonald’s—and even Kasama’s excellent iteration—by way of a finer, more deeply browned crust that reveals a clean, fluffy interior. The “Patatas Bravas” break apart cleanly and, dragged through the concentric layers of the spicy tomato sauce and aioli that coat the bottom of the plate, offer a nostalgic “ketchup and mayo” sensation with perfectly moderated heat. This visually striking presentation does not fall short when it comes to technique!

The last of Andrés’s riffs on the Spanish canon comes from “The Bazaar Experience” menu. It is titled “Tortilla de Patatas ‘New Way’” ($9 per each) and references a style of omelet considered “essential” to the cuisine. Traditionally, potatoes are cut into small pieces (with onions sometimes added), sautéed in olive oil until softened, drained, mixed with eggs, and slowly cooked on both sides to yield a robust outer crust.

Unlike the reverence with which the chef treats the “Croquetas” and “Patatas Bravas,” Andrés breaks all the rules when restructuring the recipe in his “new way.” Guests receive a small glass that has been filled with frothy potato espuma. Within it lie a 63° egg (“the point at which the egg white is just cooked, but the yolk is still delicious creamy and runny”) and some caramelized onions. Finally, the presentation is topped with tiny cubes of crisped potato and a scattering of chives that float on the surface of the espuma.

Digging in with the provided wooden spoon, you are struck by just how light and ethereal the whole preparation is. The potato element disappears instantly on your palate until you penetrate deeper into the dish and infuse it with some of the luscious egg yolk. The onions provide a fleeting touch of sweetness—and the cubed potatoes a dash of crunch—but the composition is really an exercise in deconstruction. Rather than cooking the tubers, draining them, then encasing them in whisked eggs, guests are drawn to combine the two ingredients during the process of eating the dish. (In this case, it’s the egg that is embedded in the potato rather than the opposite).

The flavors, overall, are pleasing, yet their lack of intensity seems strange when married with such fleeting textures too. The preparation feels like something Andrés would serve as an amuse-bouche at minibar, and perhaps that’s a good thing. It offers an impressive demonstration of molecular gastronomic techniques at an affordable price that allows each member of the party to indulge. It won’t go a very long way towards filling your stomach but, rather, teases the mind.

Bazaar Meat’s “Shrimp Cocktail in Grapefruit, Irma Rombauer Classic” ($14) stands as one of only a few seafood dishes on the menu (relative to the wider selection at Bar Mar). Its title references the author of Joy of Cooking (a St. Louis native), whose recipe for “Shrimp in Grapefruit” appears in the 1931 first edition. Andrés’s respect for Rombauer is apparent in his shout-out, and the chef goes so far as to assert the fresh salad “is more American and more important than the more famous shrimp cocktail.”

The dish comprises pieces of Florida Sun Shrimp—a sustainable and ethical purveyor founded in 2013—that have been poached, dressed in a mustard seed vinaigrette, then garnished with grapefruit segments, radish slices, and a few sprigs of parsley. While the combination of citrus and shellfish is certainly timeless, you are struck by how the gushing texture of the grapefruit matches the plumpness of the shrimp. The extra burst of tartness—relative to the usual squeeze of lemon—is well moderated by the heat of the mustard and tang of the vinegar.

Personally, you find that the shrimps’ natural sweetness, compared to a classic “cocktail” preparation, is a bit masked by the grapefruit. But Rombauer’s recipe, as an opening “snack,” is invigorating and palate cleansing. Plus, you admire that Andrés has taken an opportunity to demonstrate his reverence towards the history of American gastronomy and one of its most consequential works.

Bazaar Meat’s “Boneless Buffalo Chicken Wings” ($13) represent yet another classic form in which the chef has chosen to indulge. The price gets you five choice morsels of meat—seemingly taken from the bird’s “flat” (or wingette)—neatly arranged on skewers. They are lightly dressed in a buffalo-style sauce then topped with very finely diced celery and a solitary cube of blue cheese.

While decidedly dainty, the wings are true to type. The meat is juicy with a nice touch of fried crust. The buffalo flavor is subtle yet long-lasting. It blends with the cleansing celery and funky blue cheese on the finish to make for one of the most elegant chicken wing experiences imaginable. You would kill to serve these at a cocktail party. Moreover, the dish epitomizes how the restaurant draws on its technical prowess to deliver guests a quintessential bite of something beloved and nostalgic without spoiling the rest of the meal.

Next up are two airbreads: the “Kobe Airbread” ($12 per each) from Bazaar Meat and the “Philly Cheesesteak” ($12 per each) from “The Bazaar Experience” menu. Each preparation centers on a crisp, puffed roll that looks something like a small baguette. Both airbreads come topped with thin slices of “Kobe beef,” yet the former features onion jam and parmesan espuma stuffed within it while the latter is filled with cheddar.

Because Bazaar Meat serves actual Kobe “eye of the rib” sourced from Hyōgo Prefecture, you must assume that they would not misuse the designation when referring to the airbreads. That being said, the experience is more about the filling than the topping. As you take a bite, the tender beef yields to the bread’s fragile crust, which cracks and releases a torrent of filling. Undoubtedly, it’s best to eat these bites while positioned over the table. However, both the parmesan espuma and cheddar cheese are impressively light in body and deep in flavor when they touch the palate.

Overall, it is impressive to see the sizable airbread collapse into something that eats more like half its size. In doing so, like the buffalo wings, it delivers the essence of a sandwich without so much substance. The Kobe does not quite display the kind of marbling for which the meat is known, but it forms a tasty (if flashy) foil for the dough and filling. Between the two versions, it’s hard to pick a favorite, but you hope that Bazaar Meat is able to roll out its “’Italian Beef’ Airbread” (which has appeared on the online menu but is unavailable in person) soon. That version—featuring giardiniera and an “au jus espuma”—would be a clever use of the form and an unabashed love letter to the Windy City.

Andrés also serves a more substantial sandwich, the “Sloppy Joe” ($12), using the same brioche buns Bar Mar utilizes for lobster, tuna tartare, and calamari rolls downstairs. The creation of the sloppy Joe is dated to 1930, when a cook named Joe started serving a “loose meat sandwich” at a café in Sioux City, Iowa. The dish was popularized throughout subsequent decades but reached a capstone with the release of Hunt’s “Manwich” sauce in 1969 (“an easy one-pan meal for the whole family” that only required the addition of cooked ground beef). Classic recipes simmer the meat in a mixture of ingredients like condensed tomato soup, ketchup, brown sugar, cider vinegar, mustard, and onion powder.

Bazaar Meat’s version, by comparison, is a bit more upmarket. The ground beef—likely sourced from the restaurant’s steak trimmings—is prepared in the same manner as a Bolognese. (That, really, just substitutes the American recipe’s processed ingredients for higher quality tomatoes and fresh vegetables). The end result is stuffed into the brioche bun and topped with thin, crispy “straw” potatoes (that also appear as one of the menu’s side dishes).

Attacking the sandwich, you are first impressed by the texture of the bun. It displays an eggy, buttery density that does well to hold the meat while lending it a delectable accompanying flavor. The Bolognese itself is well executed, being tender and runny in just the right amount while still seeming more like a gourmet sloppy Joe filling than a repurposed pasta sauce. The beef and onions take the lead while being buttressed by a nice bit of tomatoey sweetness. Those “straw” potatoes provide a good textural contrast and burst of salt, but they’re bound to fall off the sandwich as its eaten. In truth, you think they are there in part to make the “loose meat” look more appealing.

Overall, you think Andrés has crafted a delicious take on gloriously lowbrow recipe—one that has subsequently made its way onto Bar Mar’s lunch menu too. It is also worth noting, relative to some of the other opening bites, that this dish is more substantial and would probably best be split into two or three portions (though you certainly enjoyed one all to yourself).

The last of the “Little Snacks” comes from “The Bazaar Experience” menu, but, in fact, this dish has also featured as one of Bazaar Meat’s desserts. The “Payoyo Cheese Tart” takes its name from a type of cheese made from the milk of endangered Payoya goats and Merino sheep in Andalusia. The resulting product is described as “soft, creamy, and slightly tangy, with an aroma of herbs and a balanced saltiness.”

To make the dish, the firm Payoyo is processed into a soft, thick cream that lines the inside of tart shell. A pine nut praline hides beneath it while thin shreds of the cheese, as well as black truffle, provide the finishing touches. Diving in, you find the crust of the shell to be well-formed and robust but perhaps just a little too thick. (Note the difference in flakiness between the two pictures). The creamy Payoyo, nonetheless, does a good job of clinging to the palate with a deeply flavored, salty-sweet sensation that ends on a tangy note. The shreds of cheese echo those notes while providing some textural intrigue. The same goes for the truffle, which imparts a hint of earthiness.

At its flakiest, the “Payoyo Cheese Tart” could perhaps feature as a “Little Snack.” However, especially if the shell runs the risk of coming out too thick, it should remain as one of the desserts. The flavors, relative to the other, lighter bites, are simply too rich to endure at the very beginning of the meal. But the overall package is appealing and works to introduce a more obscure product to the restaurant’s audience.

The next section of Bazaar Meat’s menu is titled “’Say When’ Caviar Service.” It comprises three types of the roe—”Russian Ossetra, Black Diamond Caviar” ($7 per gram), “Siberian de Luxe, Bjork Caviar” ($10 per gram), and “Oscietra Royal, Bjork Caviar” ($13 per gram)—starting at 10 grams. The “Say When” part of the presentation, you must say, strikes you as funny. The caption reads “we keep scooping until you say ‘When!’” yet the caviar is portioned out of guests’ sight. So it really only means that you can continue to order more of it, which is how any menu normally works.

That curious bit of pomp aside, you find the brands Andrés has partnered with to be unique. Both Black Diamond Caviar and Bjork Caviar (whose corporate office is located in Las Vegas) are new to you. But, given the premium that names like Petrossian, Caviar Russe, Regiis Ova, and Regalis can fetch, obscurity can sometimes be a virtue. While Maple & Ash offers one ounce portions (approximately 28 grams) of Kaluga ($100), Siberian ($160), and Osetra ($220) on its menu, Bazaar Meat provides a lower entry point at $70, $100, and $130. Of course, Andrés’s roe ultimately proves more expensive, but this accessibility is important for customers who might not usually splurge on such an item.

Also, whereas Maple & Ash sells pre-portioned containers of its caviar, Bazaar Meat scoops its own out of a larger tin. Your roe arrives on an attractive wooden tray containing individual plates for each variety alongside a colorful porcelain spoon. The accompaniments—pizzelle (a traditional Italian waffle cookie) and a squeeze tube of crème fraîche—lay under a folded napkin to the side.

With regard to quality, there is a noticeable climb between each of the three types of roe. Black Diamond Caviar’s “Russian Ossetra” is rather dark green with a slight clumpiness to the pearls and a more pronounced saline quality alongside hints of nuttiness. Bjork’s “Siberian de Luxe” (sourced from Belgium) displays a lighter tone of green similar to what might be called a “golden” Kaluga or Osetra. The pearls display greater firmness relative to each other and impart a more pure nutty quality with hints of salt. Lastly, Bjork’s “Oscietra Royal” (also sourced from Belgium) possesses a striking greyish tone (sometimes called “platinum”) with very fine definition between the pearls and a purely nutty flavor.

While each of the caviars—alone and in relation to each other—offer a fine representation of the totemic luxury ingredient, you think that the accoutrements fall short. Placing the crème fraîche into a squeeze tube is a playful and functional choice that allows for precision application. However, the pizzelle—as much as you want to love them—add little to the roe. Ideally, the cookies would form a flaky, slightly sweet canvas upon which the nutty notes of the caviars would shine. Yet, in practice, the feel like ordinary crackers that fall well short of what even the most traditional blini would offer. As always, you admire Andrés’s inventiveness. But, in this case, the pizzelle sound better on paper and actually work to detract from what should be a truly decadent experience. (As best as you can tell, this kind of caviar service is unique to the Chicago location, and that might explain why the cookies were not thoroughly tested).

Within the “Soups & Salads” category of Bazaar Meat’s menu, you have sampled “Lucía’s Salad” ($12) and the “Not your Everyday Caprese Salad” ($12). The former, in truth, is kind of a play on a Caesar. Thus, both preparations, in essence, reflect Andrés’s reinterpretation of two of the form’s classic recipes.

“Lucía’s Salad” comprises five “cups” of gem lettuce (each taken from the top of head) that have been filled with smaller, lightly dressed leaves, slices of anchovy, “air croutons,” and a heap of grated parmesan cheese. The dressing, to your palate, tastes every bit like a traditional Caesar. So, when you grasp one of the cups and eat it like a taco, it is kind of like experiencing a perfectly composed Caesar salad bite.

The outer layer of lettuce provides the crunch, the inner leaves deliver the dressing, the anchovy offers a fishy burst of umami, the “air crouton” adds a fleeting doughy note, and the grated cheese covers it all with a fluffy layer of nuttiness. There’s nothing groundbreaking about it, but the dish succeeds in concentrating the essence of a Caesar and packaging it into a tapas form. Given how hard it is to share salads in such a setting, you think the idea is both clever and sure to please those who desire only a bite or two of something “green.”

The ”Not your Everyday Caprese Salad,” by comparison, demands that you use your utensils. However, you think the dish succeeds in much the same way. Its shallow bowl contains plump cherry tomatoes, “liquid mozzarella,” and “air croutons” tossed in pesto. Compared to a standard caprese (or even, say, a caprese skewer), this bottom layer of sauce ensures a more comprehensive dressing than the standard basil, olive oil, and salt.

You scoop up a tomato, a ball of cheese, and a crouton then drag it all through the pesto. When the combination hits your palate, the membrane of the mozzarella bursts and coats everything in a thick cream. That joins with the juice of the tomato and the pronounced fruity-basil note of the pesto to create a dead ringer for the best possible bite of a traditional caprese. The “air crouton,” once more provides a faintly bready note that helps anchor the more aggressive flavors. While more involved than the “Lucía’s Salad,” Andrés’s take on a caprese offers five cohesive, concentrated bites of a classic salad that can easily be enjoy among all his other finger foods.

The menu’s next section, “From the Meat Bar,” features dishes drawn from that separate counter opposite the hot kitchen. Understandably, those hanging legs of jamón ibérico de bellota are put to good use—both by the ounce and as part of an “Embutidos” assortment of Spanish and domestic cured meats. Yet, since these particular products are produced outside of the restaurant, you will reserve any extended commentary. That is, except to say that the meats are expertly sliced and served with an excellent “Pà Amb Tomàquet” (bread with tomato) that is perfectly crispy and robustly seasoned.

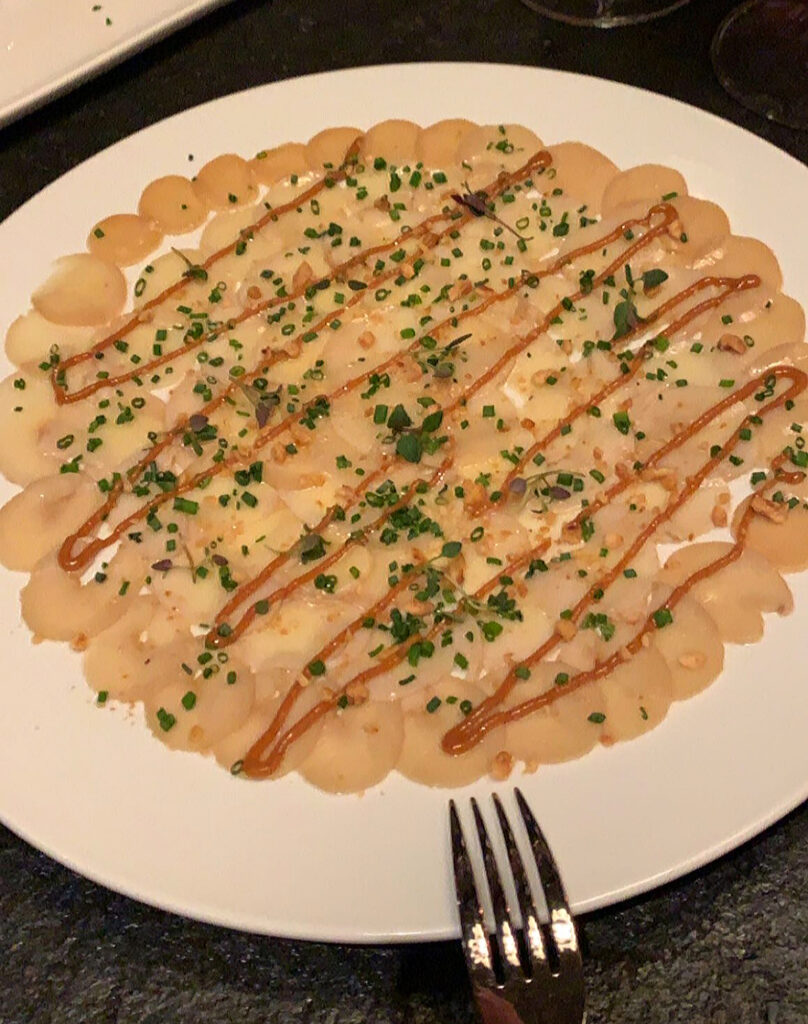

The real areas of interest within this category are, instead, the “Tartares” and “Carpaccios.” Andrés kicks off the former selection with a bit of a history lesson, describing how “tartare first appeared in Escoffier’s culinary guide in 1921” and was named after the tartar sauce with which the French chef’s “Beefsteak à l’Americaine” was served. Bazaar Meat offers three distinct takes on the form: “The Classic,” ($28) “Salmon,” ($24) and “’Beefsteak’ Tomato” ($26) tartares.