Indienne is one of few Michelin-starred restaurants in Chicago I have yet to write about. Given that it’s one of the newest concepts to earn that honor (alongside Atelier in the 2023 Guide, before Cariño in the 2024 Guide), this absence feels even more strange.

In truth, I was there: in January of 2023 (following a fall 2022 opening) and in June of the same year (for a collaboration with Raj Parr). I dined twice more in 2024 (July and September), and this meal, coming up on three years since Indienne’s opening, marks my fifth.

Clearly, there’s something about the restaurant that has kept me coming back. It’s not quite in that category of place I patronize by the tens (or even hundreds) of visits. However, just the same, it lands—if barely—on the right side of the scale: being distinctive and enjoyable enough to shine among scores of forgettable meals, to overcome my apathy, and to make an occasional appearance when I venture outside the dozen or so spots that actually define my eating habits.

Why write about Indienne now?

Well, my earliest impressions were more or less okay. The concept’s potential was apparent, and its ownership had clearly invested in the kind of space, design, and staffing that could win awards. The tasting menu extended the aesthetic through bells and whistles and other finery that, indeed, felt fancy. Yet, at the level of texture and flavor, I generally thought the food was just okay. It did not transcend the novelty of its genre (Indian cuisine being underrepresented in fine dining) to be strikingly, overarchingly delicious. However, there weren’t really clear flaws to note: just my usual search for a greater concentration of savory (or sweet) notes on which supporting elements of spice, citrus, or herbaceousness could reach a more extreme, memorable expression.

It’s not much fun to write such a piece (where everything is good—not great—and improvements really depend on altering the chef’s approach to seasoning or the kitchen’s core conceptions of pleasure and balance). Certainly, coming from outside the culture (but already familiar with at least a few other expressions of Indian fine dining), I did not feel it was my place to nitpick particularities of the menu or question the chosen interpretation of recipes.

The core vision behind what Bibendum himself proudly declared “Chicago’s First One MICHELIN Starred Indian Restaurant” was sound. It didn’t excite me too much beyond that, but it could change the city’s dining landscape and, perhaps, lead to even bolder work. Until then, I would watch and wait: counting Indienne as a place I could gently recommend to those looking for a refined experience within a particular genre (yet not one that necessarily goes toe to toe with the best concepts more broadly).

When I returned to the restaurant in 2024 (more than half a year after it had earned its star), the effect was startling. Indienne had not leveraged the award to slow down or begin to cash out. Rather, ownership had reinforced the staff, further refined the space, and tuned its cuisine (in terms of pacing and presentation) like clockwork. Objectively, I thought the food tasted better too—even if the dishes still did not quite reach that memorable, “best in the city” (irrespective of genre) caliber.

I was compelled to write about Indienne back then but, at the time, was in the thick of evaluating Valhalla “2.0” and Feld. Confirming (or undermining) the quality of a concept that has already earned its reputation did not seem nearly as fun as making sense of something entirely new.

Now, in 2025, I am certainly not the first to say that Indienne (coming up on three years since opening and two years since that Michelin star) has continued to grow in quality. However, the present format allows me to grapple with specifics—and maybe pinpoint areas that can be improved even further—without having to commit to a rating or value judgment that, maybe, it’s still not my place to make.

But, to be clear, there’s always been a lot for me to like here, and, with chef Sujan Sarkar representing Chicago at the highest levels of the industry (as a successive nominee and semifinalist for the Best Chef: Great Lakes title at the James Beard Awards), his work merits careful consideration. In fact, it has even led to something of a mini-empire at this point, with concepts like Sifr and Nadu having also entered the fray.

Nonetheless, the present focus remains on Indienne: the mothership (and, I think, one of the city’s few clear post-pandemic bright spots at this rarefied level of dining).

Let us begin.

Indienne stands in the quieter northwestern quadrant of River North. It feels removed from the Bally’s Casino, the Starbucks Reserve Roastery, and the Eataly that can be found (approaching Michigan Avenue) in the northeast, as well as the litany of restaurants (the RPMs, the Bayless properties, and plenty more) scattered to the southeast. Even relative to the southwest, with its colony of Hogsalt concepts and density of residential towers, the area feels bare.

Yet, joined by neighbors like Asador Bastian and Obélix (all separated, in a sense, by highway ramps and the massive McDonald’s parking lot), Indienne highlights a smaller neighborhood that draws on River North’s broader popularity while offering room to breathe. Indeed, while places like the Green Door Tavern, Club Lago, Mr. Beef, Wildfire, and Cocoro have anchored these blocks for decades, the streets can now claim a few proper gastronomic destinations. And one can actually park here with some ease, walking uncluttered sidewalks (past salons, townhomes, showrooms, and mixed office space) to their destination.

The stretch of Huron Street that Indienne calls home is a fairly subdued one. Other than Avli—the Greek concept (with whitewashed walls and sprawling patio) that sits on the corner at Wells—the restaurant’s neighbors are quotidian if not entirely obscure. The loft-style condo and office buildings that line both sides of the block tout architectural firms, interior designers, realtors, and even a day care as tenants. But Graham Elliot, with its two Michelin stars, once stood here, and, after a couple stints serving more casual fare (Oak + Char, Bar Lupo), the space at 217 W Huron once again plays host to fine, destination dining.

Prominent signage—with a lotus flower logo and the concept’s name (in stylized front) set against a cyan background—leads to a stairwell. There, a half-flight of steps (also used to access a hair salon) leads to a handsome set of double doors, and, once one passes through this final portal, Indienne unfurls. Wooden beams, exposed brick, extensive ductwork, and sweeping sightlines speak to the space’s history as a “19th-century printing warehouse.” Yet white tablecloths, walls ribbed with molding, frosted glass, intricate screening, plush banquettes, weighty armchairs, and accents of polished metal anchor a sense of curation and refinement.

The overall effect feels clean and minimalistic without (thanks to the preservation of those core elements) descending into coldness. Indeed, one feels equally comfortable wearing jeans or formal attire in a space such as this—a reflexive quality that stands ready to meet divergent expectations regarding the cuisine, the price point, and the meaning of that Michelin star. Even the restaurant’s wider theme (“Indian flavors and French technique”) is carefully managed without caricature or exoticism. Rather, the dining room’s most notable details—bulbous light fixtures hanging over the bar, other lamps shaded with wicker, a plant arrangement in a marble urn, the pinkish tone of the banquettes, a few abstract canvases streaked with pastel colors—remain elegant and understated.

Ultimately, a feeling of luxury is conjured structurally through the spacing of the tables, the comfort of the furniture, and the glow of the lighting (which amply illuminates surfaces while preserving the kind of moodier shadows that lend one’s evening a private, romantic tinge). Yes, Indienne does not trade in flash or gimmicks to get its point across. While, on some level, that means almost any genre of cookery could be staged in this atmosphere, a certain anonymity is likely intended. For, at the end of the day, it signals how the restaurant, confidently, resists the tyranny of any neat, tidy label. The concept, instead, seeks to shine on its own terms: as a personal, contemporary expression of craft (worthy of being judged alongside such peers) rather than only exceling, conditionally, within the narrow confines of “ethnic cuisine.”

Nothing proves this point more than the caliber of service on display here. From the moment one checks in with the hostesses, carrying through to the interactions with the captains and bussers, and even punctuated (on occasion) by the engagement of the managers and wine director, hospitality at Indienne epitomizes forethought and precision.

Structurally, the restaurant has clearly been equipped to succeed: I count more than a dozen team members working the floor in a dining room that seats 85 (along with another ten at the bar) but does not reach peak capacity during the course of my meal. Roughly, there’s at least one employee capable of keeping eyes on every set of one or two tables at any given time. Factor in the natural flow of these cleanly shirted and aproned figures throughout the space, and one gets the impression that a veritable army stands ready, at any moment, to step in. It’s the kind of feeling one associates with concepts boasting multiple Michelin stars in markets (whether for reasons of heritage or sheer density) more glamorous than Chicago’s.

At a technical level, this show of force is most clearly perceived through the timely refilling of water or wine, the clearing of plates, the folding of napkins, and the ironing of tablecloths in preparation for the next seating of guests. Each dish is described (both by the captains and, impressively, the bussers) with total fluidity and detail. They do not fumble over pronunciation or miss a single point. At the same time, the spiels remain succinct enough so as not to seem belabored in front of hungry diners. Pacing, on the same note, is executed to perfection. Larger courses consistently land with tight 15-minute gaps between them while smaller bites, in turn, are delivered in an even shorter, synergistic timeframe that ensures the meal starts and ends with a sense of dynamism.

Really, the operation here—so clockwork-like—is hardly equaled and probably not surpassed in Chicago. Some teams may be tasked with doing more mechanically. Others, commensurate with the higher sum being paid for their hospitality, may view it more as part of their core duties to linger and connect with the guests. However, relative to expectations (at this price and in contrast, say, with à la carte concepts where one can spend much more), Indienne’s front of house absolutely excels.

Perhaps most importantly, the attentiveness of the staff is tempered by a sense of ease and warmth that cloaks all the nuts and bolts of service in the guise of a nice, fun night out. Thus, there’s nothing overbearing or intimidating about the number of people who stand ready to help. Rather, I think they seem rather naturally friendly, and the resulting mood—one of shared comfort—undoubtedly adds to the experience.

This proves key when considering how some of the clientele (predominantly white and Indian yet fairly broad in age range) might be taking a leap on the style of cuisine or dining format, more generally, being offered here. From beginning to end, the team ensures that the chef’s food is given the best chance to please patrons no matter which point of appreciation they approach it from. I have even found that special requests (the doubling up on supplements or ordering of additional dishes from the bar menu) are received with total graciousness.

Ultimately, Indienne’s practice of hospitality more than justifies the “mandatory 20% pre-tax service charge” (“to support equitable wages & benefits for our front-of-house & back-of-house team”) it adds to the bill. The “optional 4% pre-tax surcharge…to help offset rising operating costs and health benefits” is maybe a bit more controversial. Nonetheless, the service offered would merit a gratuity of 25% or more under normal circumstances, and I appreciate that option to leave an “additional tip” is clearly designated as such.

Lastly, with regard to atmosphere, I will note one fly in the ointment: the number of gnats that happened to be buzzing around the restaurant tonight. Yes, at one point, I counted three of them on my table at once. This is an old building, so I can understand if these kinds of unwanted visitors are a fact of life. Certainly, I will also not pretend that other restaurants in this city (charging much greater sums) do not occasionally suffer from the same problem. That being said, given how well this restaurant cares for its diners, one hates to be pulled out of the moment due to the fear a bug might nosedive into a glass or plate. Could more not be done to proactively prevent this problem?

Having now taken my seat, the first choice to make is what to drink.

Cocktails at Indienne are ingredient-focused and matched with illustrations of their respective central flavors. The “Buttermilk” ($20)—made with vodka, yogurt, cumin, carom seed, and “fizz”—is bright and tingly on entry with a sharp, savory finish marked by warmth, earth, and anise. The “Coconut” ($21), by comparison, combines gin, yuzu sake, Campari, and Punt e Mes in a tangy, tropical take on the negroni. While I slightly preferred the former recipe, both came together nicely: matching creativity with depth and a good (if not truly memorable) sense of enjoyment.

Alternatively, wine pairings at the “Indienne” ($80) and “Reserve” ($120) levels are listed, pour for pour, on a provided menu. This friendly gesture allows guests to make an informed decision about whether to pay the premium for the nicer selection (or to opt for one or the other at all). At present, the former draws on Chablis, Vouvray, domestic rosé, a Rioja Reserva, and Pineau des Charentes while the latter features Bourgogne blanc (from a premium producer), Nahe Riesling, Marsannay rosé, a Rioja Grand Reserva, and Madeira. With the chosen bottles priced around $20-$40 and $40-$80 at retail (respectively) across the two pairings, I think the two options do a nice job of marrying quality and value.

That said, there is no question that the work of lead sommelier Tia Polite shines most brightly when one flips open “The Bottle List.”

Here are some representative selections:

- 2023 Lady of the Sunshine “Chevey” [Sauvignon Blanc/Chardonnay] ($65 on the list, $39 at national retail)

- 2022 Peter Lauer “Ayler No. 25” Riesling ($65 on the list, $31.99 at national retail)

- 2022 Brij Wines Grenache Rosé ($70 on the list, $36 at local retail)

- 2022 Saalwächter Silvaner Alte Reben ($75 on the list, $37 at national retail)

- 2023 Eva Fricke “Rheingau” Riesling ($90 on the list, $38 at national retail)

- 2023 Marcel Lapierre Morgon “N” ($90 on the list, $39.99 at national retail)

- 2021 Philip Lardot “Der Graf” Riesling ($90 on the list, $50 at national retail)

- 2022 Scar of the Sea “Bassi Vineyard” Pinot Noir ($90 on the list, $45.99 at national retail)

- 2022 Saalwächter Weißer Burgunder ($95 on the list, $45 at national retail)

- 2023 Weiser-Küntsler “Enkircher Ellergrub” Riesling Kabinett ($100 on the list, $47.95 at national retail)

- 2020 Overnoy-Crinquand Arbois-Pupillin Trousseau ($105 on the list, $48.99 at national retail)

- 2022 Sylvain Pataille Bourgogne Rouge ($120 on the list, $37.99 at local retail)

- NV Pierre Gerbais Champagne “Grains de Celles” Extra Brut ($135 on the list, $49.99 at national retail)

- 2022 Keller “Westhofen” Sylvaner ($150 on the list, $69.96 at local retail)

- 2019 Ar.Pe.Pe Valtellina Superiore Grumello “Rocca de Piro” ($160 on the list, $60.99 at local retail)

- 2022 Pattes Loup Chablis “Vent d’Ange Mise Tardive” ($160 on the list, $59.95 at national retail)

- NV Bérèche et Fils Champagne “Réserve” Brut [DG: 06/24] ($165 on the list, $79.99 at local retail)

- 2022 Walter Scott “Freedom Hill” Pinot Noir ($170 on the list, $79.95 at local retail)

- 2022 Moreau-Naudet Chablis Premier Cru “Montée de Tonnerre” ($180 on the list, $80 at national retail)

- 2022 Thibaud Boudignon Savennières “La Vigne Cendrée” ($195 on the list, $110 at national retail)

- NV Egly-Ouriet Champagne Grand Cru Brut [DG: 12/22] ($215 on the list, $119.99 at national retail)

- 2022 Hofgut Falkenstein “Krettnacher Euchariusberg” Riesling Kabinett Alte Reben #8 ($215 on the list, $44.99 at local retail)

- NV Savart Champagne “Bulle de Rosé” Premier Cru Brut Rosé ($225 on the list, $105 at national retail)

- NV Dhondt-Grellet Champagne Premier Cru “Les Terres Fines” Extra Brut ($230 on the list, $94.95 at national retail)

- NV Bérèche et Fils Champagne “Campania Remensis” Extra Brut Rosé ($250 on the list, $125 at local retail)

- 2019 Valentini Trebbiano d’Abruzzo ($280 on the list, $149.95 at national retail)

- 2021 Jean-Claude Ramonet Chassagne-Montrachet Premier Cru “Boudriotte” ($315 on the list, $219.95 at national retail)

- 2022 Domaine Roulot Meursault “Luchets” ($360 on the list, $319.95 at national retail)

- 2018 Case Basse di Soldera Sangiovese ($650 on the list, $699.95 at local retail)

- 2022 Keller “G-Max” Riesling ($2,100 on the list, $1,750 at local retail)

From the get-go, Polite deserves praise for what might be the cleverest, most creative framework for categorizing the list’s styles of wine. In collaboration with Rayna Bartling, the sommelier has coded her selections using categories like “Pop Art” (zippy, energetic, refreshing), “Impressionism” (elegant, aromatic, soft), “Baroque” (bold, rich, structured), and “Craft” (unique, artful, hands-off).

If I recall correctly, these actually used to form different sections of the book (which somewhat shuffled the selections across its pages). At present, the varying styles of art are rendered via a column that extends down the margin and subtly brackets groupings of bottles. In this manner, the list retains its conventional structure (color to color, country to country, region to region) for the average drinker while offering added insight to those who process the colorful border over to the side. In the age of increasing annotation of individual bottles (done with varying degrees of success), this is an elegant solution: one that, fundamentally, separates acid-driven (from softer) and structured (from more “natural”) wines in a way that cuts right through to some of consumers’ key preferences.

When one digs into the substance of the selection, things only get better: one finds all the popular varieties (Chardonnay, Riesling, Sauvignon Blanc, Gamay, Pinot Noir, Nebbiolo, Sangiovese, Tempranillo, Cabernet Sauvignon, Grenache, Syrah) represented in their familiar homes (Burgundy, Germany, Sancerre, Beaujolais, Sonoma/Oregon, Piedmont, Montalcino, Rioja, Bordeaux, Napa, the Rhône). One also finds geekier grapes like Albariño, Friulano, Trebbiano, Scheurebe, Silvaner, Grüner Veltliner, Chenin Blanc, Viognier, Gewürztraminer, Trousseau, Cabernet Franc, Nerello Mascalese, and Zinfandel hailing from their traditional regions. Of course, there’s plenty of Champagne on offer (even marked with disgorgement dates when applicable) along with plenty of skin-contact options and oddballs like an apple co-ferment or an Indian sparkling rosé.

As nice as it is to see such a comprehensive range of styles offered, it is really at the level of producer that this list amazes. Polite stocks a roll call esteemed names (like Ausone, Boxler, Chave, Clape, Egly-Ouriet, Guiberteau, Jamet, Keller, Krug, Lapierre, Mayacamas, Montrose, Egon Müller, Pichler, Ramonet, Ridge, Roulot, and Soldera) alongside cultier favorites (like Boudignon, Cornelissen, Dhondt-Grellet, Falkenstein, Peter Lauer, Pataille, Pattes Loup, Saalwächter, Savart, Walter Scott, and Valentini), with many of the latter estates hardly being found anywhere else in the city.

With such an estimable selection on hand, Indienne impresses the most with its low markups. The premiums charged for the bottles in my sample range from 378% on top of to 8% below retail price (with a mean of 112% and a median of 107%). However, when one removes the three outliers, the mean drops to 103% and the median to 106%.

Simply put, this an astounding degree of restraint for a Michelin-starred concept that has little problem filling its seats, and it’s the kind that multiplies the effect of Polite’s expertise by marrying it with a sense of generosity. Add in a fair corkage policy ($35 per bottle with a limit of two 750mL bottles per party), and it is clear that Indienne wants customers (whether still learning or seasoned oenophiles) to celebrate fine wine alongside its food.

Indeed, there is no greater honor for a chef—and no warmer way to introduce a such a distinctive cuisine (which may be unfamiliar in its essence for some, unfamiliar in its refinement for others) to the public. Ultimately, Polite’s wine program is a remarkable feather in the restaurant’s cap: the kind that has deservedly won awards but also, in practice, does so much to make me want to return here in its own right. There is no question the sommelier’s work ranks among the very best in Chicago.

With that, I turn toward the food: province of chef-owner Sujan Sarkar, a native of Kolkata who cut his teeth at the Michelin-starred Galvin at Windows (in London), Olive Bar & Kitchen (in New Delhi), and Trèsind (in Dubai) before opening the original San Francisco location of ROOH in 2017.

He would lead the latter concept’s expansion throughout the United States—including a Chicago branch (that, now titled ROOP, has subsequently broken with the rest of the group). Sarkar felt the city was “lagging behind New York and the Bay area” in terms of its Indian food scene and resolved to open a “progressive Indian fine dining restaurant” that could offer a fresh perspective on the cuisine while educating and “break[ing] stereotypes.”

Though some of the chef’s “well-wishers” thought he was crazy for pursuing a “full-fledged tasting menu in this style,” Indienne—its name inspired by a type of textile design popularized in Europe (which doubles as the word for “Indian” in French—would draw on his “decades of…modern European training.” Using “traditional stories and flavors” as a foundation, the restaurant sought to thoughtfully blend techniques in a way that was “affordable” and “accessible” relative to other fine dining concepts.

Today, the Michelin star and James Beard Awards nominations certainly suggest that Sarkar’s equation is a winning one—even as he looks to “innovate over and over again” to “showcase the beauty of Indian cuisine.”

At present, Indienne serves four distinct menus that ring true to the chef’s commitment toward approachability and value: “Vegan” ($135), “Vegetarian” ($135), “Pescatarian” ($145), and “Non-Vegetarian” ($145). Supplements are offered for each of these options alongside an à la carte listing of bar bites.

My experience centers on the “Non-Vegetarian” menu in combination with both supplements and a couple items from the bar menu (all of which will be designated when they appear).

The meal starts with an opening bite, served over ice, titled “Dhokla Aero”—a play on the steamed, savory cake referenced by the first word. This Gujarati recipe typically draws on a fermented batter typically made from chickpea flour (with the possible addition or substitution of other grains) that is generously spiced.

Here, the term “aero” references the dhokla’s rendering as an airy, honeycombed structure that calls freeze-dried molecular gastronomy constructions to mind. On the palate, the bite displays a fleeting structure that moistens and melts with a couple of chews. The resulting flavor is pleasantly sweet on entry yet quickly yields to earthier, savory notes, then a burst of pungency, and rousing finish characterized by more than 20 seconds tongue-awakening heat. Overall, this makes for a fun flash of technique that is backed unique intensity of spice: a nice introduction to the kind of cooking Sarkar elaborates on throughout the menu.

The next course comprises a set of two additional finger foods. First, there’s the “Pani Puri”—one of Indienne’s longstanding constructions that adapts the titular form (typically a fried shell of puffed bread that is stuffed with a potato-chickpea filling then dipped in flavored water) as a kind of tart.

Yes, the chef uses a buckwheat shell as a base for a dollop of passion fruit jelly laced with green apple and tamarind. A crown of flower petals completes the effect, which is beautifully delicate. Texturally, the bite more than lives up to its appearance: offering a brittle snap matched by rich, mouthcoating fruit. Though sweet and tangy at first blush, this panipuri impresses with its own depth of warming spice and appreciable (yet well-judged) heat through the 30-second finish. It ranks as another precise, delightfully provocative opening morsel.

Forming the second piece of this course is the “Avocado Bhel” (the latter term referring to a puffed rice “beach snack” tossed with herbs, onions, and chutneys). Here, Sarkar imagines those crispy grains as a set of crackers made from black rice. They hold, in a manner reminiscent (at least visually) of a Mint Oreo, a thick filling of avocado.

Seemingly creamy, the avocado is actually frozen. It waits on the other side of the crackers’ crunch, being too cold (somewhat painfully so) on entry but slowly unfurling. Once that occurs, the filling offers a long, robust sweetness that, toward the end, is marked by a sharp zestiness without veering toward heat. In this respect, the bite forms a beautiful, refreshing counterpoint to the other two bites: matching some of the notes of their spice while settling on a more soothing finish. My only regret is that I ate this item before the “Pani Puri” (in the order articulated by one of the bussers rather than written on the menu), detracting a bit from the kitchen’s desired synergy.

The first proper, composed dish of the night is titled “Yogurt Chaat.” The latter term (literally “to lick”) refers to a wide range of savory snacks served as street food in Indian. Within this context, yogurt (also called dahi, which refers to a homemade type of curd) is widely used as a topping for potatoes, chickpeas, fried dough, lentil fritters, and the like. The present recipe inverts that relationship, using a dollop of the fermented dairy as a base for a trio of chutneys and a crowning, ruffled sweet potato chip.

Texturally, the interplay between this brittle topper and the rich, creamy yogurt is nicely composed. There’s also enough of the chip to ensure that each bite is marked by this essential contrast. When it comes to flavor, the curd displays a subtle tang on entry. However, just when its mouthcoating density might seem to signal blandness, veins of sweet stone fruit, chili spice, and cooling mint come to the fore. These notes push and pull at each other, enlivening every spoonful of the yogurt and even helping to distinguish some of the earthy, nutty character of the sweet potato. Heading toward the finish, the dish feels cohesive and seemingly kaleidoscopic. A trace of heat remains when all is said and done. Yet, moreso, this preparation leaves me with surprising degree of satisfaction: its humble constituents—so intense (and vegetarian no less)—forming one of the highlights of the night.

With the arrival of the next course, one’s choice of the “Pescatarian” or “Non-Vegetarian” menu begins to bear its fruits. The “Scallop Xec Xec,” attractively served in a purplish shell, feels more like an archetypal expression of “fine dining” than it does any single genre or tradition. Indeed, joined by a perfect quenelle of golden Kaluga caviar and a creamy corn dressing, the bivalve (seared to a craggily golden brown) seems worthy of any amorphous “contemporary American” concept. Nonetheless, the term “xec xec” refers to a spiced, coconut-based Goan curry (typically served with crab), and the corn itself is meant to reference a popular Rajasthani soup (or “raab”).

Despite this depth of influence, the dish eats as expected. The plump, buttery scallop (sliced into four pieces for convenience) sees its texture enriched by the accompanying sauce and framed by the subtle pop of the roe (when incorporated). It’s at the level of flavor that things get more interesting: as the notes of corn here lack any real sweetness, and an application of “Goan spice” (warming but not too hot) drives the recipe further toward the savory side. Yes, while undertones of miso help lend the starring shellfish a sense of weight and meatiness, I almost find this preparation to be one-note. It lacks the fresh, sweet character through which scallop-corn combinations typically shine, and, as a consequence, the nuttier nuances of the caviar get lost in the shuffle too.

To be clear, this is by no means a bad dish (in fact, I think it will be heartily welcomed by those diners, perhaps a more skeptical sort, who looking for something legible and substantial at this early point it the meal). Instead, I just do not think the ingredients—so luxurious on paper—live up to their full potential.

Thankfully, I cannot say the same for the “Lobster Ghee Roast” ($28): a supplemental course that allows customers to trade up to a superlative expression of shellfish. For this preparation, a whole segment of the crustacean’s tail (albeit a smaller specimen) is brushed with clarified butter and cooked over embers. It is paired with a sauce made from sunchoke and a thicker gel made of mango. Off to the side, an “ela ada” (or steamed rice parcel, traditionally filled with sugar and coconut) stuffed with prawn forms a creative accompanying bite.

On the palate, the lobster displays the kind of firmness and structure for which it is known (qualities, in truth, that lead many to think its totemic luxury status is somewhat overrated). However, I can in no way fault the execution here, for the crustacean feels full and tender as can be. Further, the meat is marked beautifully by a buttery sweetness that only sees itself amplified via the nutty notes of sunchoke and concentrated, almost caramelized sugar tones of the mango. Yes, the word “textbook” comes to mind here, and I must praise the sidecar too. Smacking of its own plump, sweet prawn interior, the rice pocket forms a yielding, dumpling-like counterpoint whose succulence adds to the fun. Ultimately, this added course amply achieves the kind of pleasure that the “Scallop Xec Xec” left me wanting. It has to rank as one of the most reliable, rewarding supplements offered on any tasting menu in Chicago.

Speaking of add-ons, I now come to the first of two dishes ordered off of the bar menu. The “Octopus (Xec Xec)” ($18), on paper, sounds like it risks repeating the mistakes of that same scallop dish. However, while the recipe draws on some of the familiar “Goan spice,” the overall composition is much more successful.

On the palate, the small chunks of cephalopod strike with that intoxicating combination of chew (on entry) and dense, rich, tender flesh (with further mastication). Truly, I can only compare the texture achieved to what is served at Kyōten! Building on this base, one finds crunching coins of pickled kohlrabi and traces of creamy sunchoke mousseline. Yet it’s the combination of these sour and nutty notes with the sweet tang of fermented gooseberries and potent umami of black garlic that really makes the preparation sing. Here, like so many of Indienne’s greatest creations, one’s tongue is taken in innumerable directions without feeling overwhelmed. Rather, accented by the warmth of those titular “xec xec” spices, the octopus runs the gamut only to come back tasting cohesively, convincingly seasoned and staggering in its length. This is a highlight of the night that I cannot—will not—resist ordering again.

The second dish added on from the bar menu, titled “Pork Belly (BBQ)” ($15), meets and maybe even exceeds the octopus. Here, a generous slab of the meat has been braised with a pomegranate glaze and sliced into individual segments. They then come topped with bits of compressed apple, thin sheets of apricot gel, dabs of apricot jelly, and mustard—with more of the pomegranate used to make a barbecue sauce.

Texturally, the pork epitomizes what this cut can offer: a cap of luscious fat framing juicy flesh that retains enough structure to scratch the most carnivorous of itches. With the belly so skillfully executed, the assembly of tart-sweet fruit, pungent mustard, and a sneaky hint of heat is just sublime. Each bite builds on—and unlocks—the meat’s porcine character, driving toward a finish filled with lip-smacking ecstasy, Once the plate lies empty, I am already dreaming of another order. For now, the item stands as confirmation of what the kitchen can achieve when it aims squarely at decadence. Bravo!

Moving back to the tasting menu, it is the final two savory courses that really fulfill the “Non-Vegetarian” selection’s name (at least relative to the “Pescatarian” offering). Of these, the “Chicken Katli” comes first: a coy reference to an Indian dessert made from a paste of cashews and sugar solution cut into a diamond shape. Not to worry, the bird is not actually rendered in a sickly-sweet fashion. Rather (in what has become a signature of Indienne), Sarkar forms chicken carpaccio, a malai chicken mousse (inspired by the spiced, yogurt-marinated dish of the same name), and black truffle together into a kind of terrine. The chef slices the end product into the titular, eye-catching shape and pairs it with an emulsion made from Amul: a processed, cheddar-style cheese that forms a cult favorite in Indian cooking.

Approaching the dish, I find that the chicken proves impressively spoon-tender. The terrine, likewise, feels moist on the palate, but the resulting flavor displays only the most subdued notes of spice and heat without much noticeable truffle. In the same manner, while I appreciate the choice to utilize the Amul (an unapologetic expression of the country’s everyday food culture), the creamy cheese’s subtle tang and salt also doesn’t quite do enough to carry the recipe. Technically and thematically, there is no question that the “Chicken Katli” will prove memorable for much of the restaurant’s audience. I wouldn’t even say it suffers from any clear flaw. However, if the texture of the bird is going to be homogenized to such an extent, it needs to be matched with a corresponding concentration of poultry (or truffle) flavor that justifies the trick. Otherwise, this dish may have simply suffered by arriving on the back of such a strong “Pork Belly” preparation.

That said, the “Chili Cheese Kulcha” ($6) offered as a supplemental bread with the preceding dish was quite enjoyable: being beautifully puffed, speckled, crisp on entry, and infused with mild notes of the titular cheese. I particularly enjoyed the kulcha’s interplay with the Amul emulsion (both flavors building in a way that didn’t occur with the chicken) and was quite happy to have asked for two orders of this delightful add-on.

The last savory course of the night is titled “Lamb Nihari,” and one need not worry about any mind-boggling reimagining of dessert here. Rather, the titular recipe refers to a classic stew made from the animal’s shanks (which are seared, spiced, and slow-cooked in a kind of thickened gravy). And the rendition here simply dresses up the form: pairing a prime cut of Australian lamb loin (ember-grilled, crusted in pistachio) with the rib meat (rendered as a roulade), a twirl of crispy potato, some celeriac purée, and a pour of nihari-inspired braising liquid. A serving of garlic naan and a cup of black dairy dal (a creamy lentil curry) complete the presentation.

Texturally, I find that the meat itself is well-executed, with the loin offering a slight chew (yielding to tenderness) and the rib meat being more fall-apart (though perhaps not as exceptional as the pork belly). The potato looks like it will be crispy, and it is actually rather soft. Nonetheless, the naan—delicate and flaky—builds on the quality shown by the kulcha while the dal, in turn, possesses a soothing consistency once incorporated.

As promising as these varied components sound, I am left searching when it comes to flavor. The nihari gravy should undoubtedly carry the dish, yet it fails to offer the depth of savory flavor I demand. There are traces of spice and heat at hand, yet the lamb itself tastes undistinguished and in need of salt. The mild sweetness of the celeriac and the more robust warmth of the dal (quietly the best thing on the table) do their best to rescue the situation. However, as I felt with the “Scallop Xec Xec” and “Chicken Katli,” this dish falls short of the pleasure its ingredients promise. It also has a hard time matching the intensity found from items on the bar menu and even the meal’s opening vegetarian bites. But, to be clear, the “Lamb Nihari” is by no means bad. It’s just a little underwhelming.

The turn toward dessert comes swiftly courtesy of the “Bal Mithai.” The name refers to a Kumaoni confection (chocolate-like but not technically so) made from evaporated milk solids, cane sugar, and roasted poppy seeds. Here, the dish is rendered in a bowl using milk ice cream, Dulcey (a kind of blond chocolate) crémeux, bits of preserved orange, crispy rice balls, and pearls of coconut created using dry ice.

Layered and complex, the dish strikes with chewy, brittle, creamy, and melting textures that leave behind a deep, deep flavor of caramel. Toward the end, some uplifting acid and tropical fruit notes also come through. I struggle to adequately describe how the ingredients come together, but the sum effect is stunning: a return to the kind of concentrated, wide-ranging compositions that have characterized this meal at its best.

The menu’s final bites—termed “Treats”—arrive shortly after. The trio kicks off with a play on “Filter Coffee” that is rendered, atop a cup of beans, as a bonbon. The resulting orb is nicely formed, with a glossy exterior that shatters to reveal a liquid center tinged with bitter notes of chicory. The confection, nonetheless, ends on a pleasant roasted chocolate flavor. This is a good start.

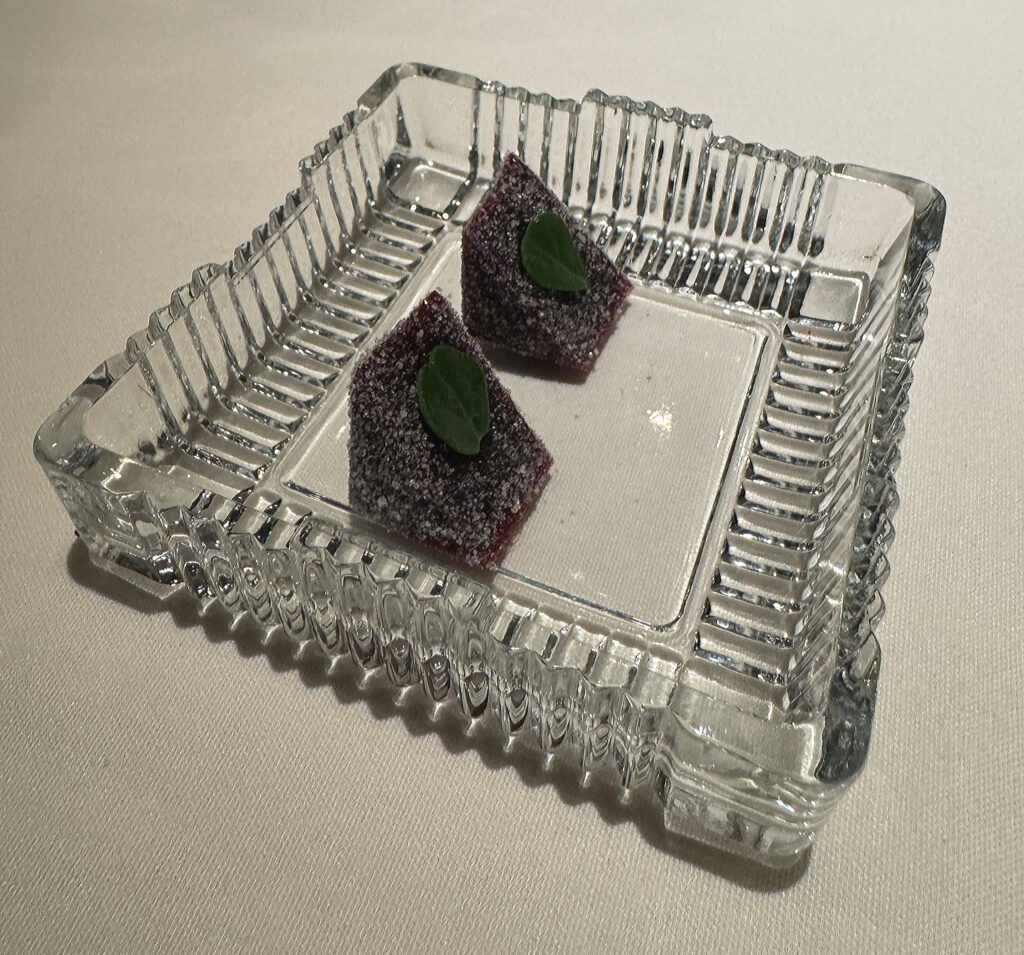

“Huckleberry,” in turn, takes the form of a pâte de fruit—in seeming reference to the Solanum scabrum (or garden huckleberry) cultivated in India that is biologically distinct from the berry known here in America.That said, the jelly delivers a pronounced tang and notes of ripe dark fruit that do, indeed, taste familiar. This is also good.

Lastly, there’s the “Bhapa Doi,” which references a traditional Bengali dessert (made from a steamed mixture of yogurt and condensed milk) likened to cheesecake. I must agree, for the resulting tart (its crisp shell crowned with gold leaf) possesses a filling of wonderful density and rich, custardy flavor marked by hints of tang and spice. This is great—and a perfect way to close out the evening.

Two-and-a-half hours after sitting down, my meal at Indienne comes to its conclusion. That’s a serious amount of time for a serious experience: one that, despite landing at the most affordable end of the Michelin-starred tasting menu spectrum (behind Elske, ahead of Galit), feels complete.

Of course, it helps to have a killer wine list, and supplements, and even more add-ons (from the bar menu) to dress dinner up as one desires. However, I can think of many fine dining restaurants that offer far less while charging far more. Even with the mandatory 20% and the optional 4% added to the bill, I walk out of here tonight feeling thoroughly satisfied.

The restaurant, at its humble base price, stood ready to push itself to that next level when called upon to do so: an inversion of the high expectations—and low returns—that can characterize other concepts across all genres of dining.

Yes, in reflection, I think the most inspiring thing about Indienne (as well as the thing that allows me to sidestep deeper questions about how, more particularly, Indian cuisine is being imagined here) is how well it transcends its genre altogether.

This is not a backhanded compliment. Rather, it marks the difference in saying “this is a very good Indian (with French accents) restaurant” and “this is a very good restaurant—full stop.” It declares, wholeheartedly, that Sarkar is not competing at the level of novelty but, instead, alongside innumerable “contemporary” concepts that need not put themselves in neat and tidy stylistic boxes to succeed.

For a chef whose stated goal is to attract “an audience that may not be familiar with Indian cuisine,” to “surprise them with delicious food and unmatched hospitality,” but also “to educate them and allow them to appreciate Indian cuisine in a new light,” the results are totally convincing. By all means, there’s reason to believe that guests coming here from a place within the culture will also find something pleasantly “different from what they’ve seen or known.”

Focusing more intently on the food, I cannot ignore that I tended to prefer the opening bites (common to the “Vegetarian” and even “Vegan” tasting menus) to the composed seafood and meat preparations that distinguish the “Pescatarian” and “Non-Vegetarian” selections. In fact, it felt as though dishes like the “Dhokla Aero,” “Pani Puri,” “Avocado Bhel,” and “Yogurt Chaat” really pushed my palate while the “Scallop Xec Xec,” “Chicken Katli,” and “Lamb Nihari” almost played things too safe (with regard to umami, heat, and spice).

Thanks to the quality of supplements and add-ons like the “Lobster Ghee Roast,” “Octopus (Xec Xec),” “Pork Belly (BBQ),” and “Chili Cheese Kulcha,” I was insulated from the disappointment these later savory courses might have spelled if enjoyed on their own. Nonetheless, I should reiterate that the scallop, chicken, and lamb dishes were not even really flawed. Their textures, in fact, were almost uniformly impressive. It’s just that the balance of flavor they each pursued was too soft and undistinguished compared to what else the kitchen offered.

This leads me to ask, “did I make a mistake?” Is the “Non-Vegetarian” menu, at core, the one intended to snare skeptics with more crowd-pleasing fare? Is it at those “Vegan,” “Vegetarian,” and “Pescatarian” levels (not to mention the supplements and bar menu) that the kitchen’s better, bolder work can actually be found? Is this a bad thing?

One can argue that any “fine dining” rendition of an underrepresented cuisine risks (if it prizes approachability and, thus, mainstream taste) selling out. Such a critic might view the half-step toward acceptance that such a restaurant embodies as a kind of Disneyfication: a cowardly refusal to take the unapologetic leap toward the kind of boundary-pushing work that drags the practice of craft forward. It doesn’t matter if the latter kind of cooking might only be legible to a smaller audience. A chef should forthrightly pursue excellence, on their own terms, and force the dining scene to keep pace rather than pull punches, grovel, and settle for a bastardized kind of success.

Really, we’re talking about the assimilation of “ethnic” cuisines (either via explicit fusion or implicit restructuring) toward a Western mode of appreciation, and I see the allure of such an argument: one that thinks of what is sacrificed—or altogether lost—through this process of translation. At the same time, footholds are important too—think of how long it has taken for omakase to take root here and the adaptations that have proven most successful.

If Indienne errs on the side of approachability, it does so with a degree of technical precision (on both the Indian and French sides of its cuisine) that is a credit to its influences. If the restaurant does not push its patrons, across each of the menus, as hard as it could, it offers the kind of depth (in catering to dietary restrictions, featuring additional food, mixing memorable cocktails, and supporting one of the best wine programs in Chicago) that any concepts—beyond questions of genre—should be jealous of.

If anyone is going to someday take that next step, toward the no-holds-barred interpretation of modern Indian cuisine that the city may or may not be ready for, why shouldn’t it be Sarkar? He has laid the groundwork, set the standard, and built the well of support that can sustain (if he so chooses) a more adventurous, challenging vision. Yet, for now, there are still battles to be fought—and won—at the all-important first step of cultural appreciation and understanding.

In ranking the evening’s dishes:

I would place the “Octopus (Xec Xec)” and “Pork Belly (BBQ)” in the highest category: superlative items (so tender, so intense, so incredible in their length) that stand among the best things I will be served in any restaurant this year.

The “Lobster Ghee Roast,” “Chili Cheese Kulcha,” and “Bal Mithai” would follow, representing great dishes—texturally refined with (perhaps save for the kulcha) notable concentrations of flavor—that land among the best preparations I will eat this month. I would love to encounter this again.

The “Dhokla Aero,” “Pani Puri,” “Avocado Bhel,” “Yogurt Chaat,” and “Bhapa Doi” come in one step lower: good—even very good—recipes that delivered ample enjoyment without quite rising to the level of being memorable.

Finally, the “Scallop Xec Xec,” “Chicken Katli,” “Lamb Nihari,” “Filter Coffee,” and “Huckleberry” come in last: dishes that were merely good or average (some suffering from muted flavors) and, thus, disappointing given the standard set by everything else. By no means are these recipes flawed (indeed, the latter two treats were perfectly fine). Rather, given that the core textures supporting the scallop, chicken, and lamb preparations are sound, they could easily be improved with a different approach to balance or seasoning.

Overall, this makes for a hit-rate of 75% to 100% depending on how harshly one chooses to judge the items in the latter category. Given that the closing “Treats” generally worked as a sequence, I might even say that the hit-rate is more like 80% to 100% (not to mention that many diners, without a doubt, will find the scallop, chicken, and lamb dishes to be perfectly satisfying).

Ultimately, this is a stellar average for any restaurant carrying the weight of expectations that come with a Michelin star—and one whose import only grows (even if my favorite dishes cost extra) with some consideration of the value being offered within that category.

Yes, in the final analysis, Indienne forms an estimable blueprint for how chefs may transplant novel or underrepresented cuisines into a fine dining context. That said, it’s not a path that can just easily be replicated with a turn of French technique and some tableside flourish.

The restaurant I encountered today, in 2025, has certainly grown in the three years since its opening. However, it has also reaped the rewards of the right foundation: a chef (like Sarkar) who got to know his market before going premium, a sommelier (like Polite) who is at the top of her field, a staff-guest ratio that makes the hospitality purr, and ownership willing to invest in it all while preserving the concept’s affordability.

Again, with Indienne, I am not speaking of a place that excels on the basis of any qualification. It is simply a great restaurant: one that has earned its place in the firmament of the city’s fine dining elite.