When you last left Joe Flamm—a little more than a year ago—the broad-shouldered chef had successfully shepherded his new restaurant through its first few months of opening. There were, you noted at the time, a few kinks to be ironed out. However, the dynamism of Rose Mary’s menu, the depth of its opening wine list, and the buoyant mood that marked the dining room made a positive impression.

To you, the concept clearly possessed all of the ingredients—not least of which its hands-on leadership and warmth of hospitality—to become one of Chicago’s finest “casual” (that is, not fine dining) eating establishments. And that potential, looking at the restaurant’s growth since the last time you analyzed it, has largely been fulfilled.

Notably, Rose Mary’s pastry department has been reinvigorated with an improved lepinja recipe that—thanks to the flatbread’s warm and crusty character—has taken dishes like the “Stracciatella” to new heights. Dessert, also, has expanded beyond mere sorbet, gelati, and fritters to include the kind of substantial cakes (like a “Chocolate and Honey Mađarica” and a “Toffee Zelten”) that more adequately draw such a rollicking, tavern-style meal to a close.

Throughout this period, Flamm has reliably introduced new savory dishes to the menu while, at the same time, tweaking old ones to make use of the best seasonal fruits and vegetables. You have had to bid farewell to certain favorite items—like the chef’s beautifully charred chicken wings—but a core of classic preparations, like the “Zucchini Fritters,” “Pork Ribs Pampanella,” and pastas such as the “Radiatore ‘Cacio e Pepe,’” remain.

The restaurant’s wine program, under the care of Leigh Ervine, has gone from strength to strength. While maintaining the low markups that distinguished the list from the beginning, she has expanded the array of bottles to include a wider assortment of Champagne, some large-format offerings, and a range of new producers like Brovia, Sylvain Pataille, Domaine Tempier, Frank Cornelissen, Ornellaia, Gaja, and Salicutti. Ervine’s efforts have earned Rose Mary an “Award of Excellence” from Wine Spectator—but that is only a small testament to a selection that puts the city’s other “trendy” restaurants (including some with Michelin stars) to shame.

Meanwhile, Sancerre Hospitality has tapped Flamm to “take the reins” at nearby BLVD Steakhouse—an underperforming venue (by your measure) that can now be better aligned with the group’s crown jewel Croatian property. You are unsure what this move will mean for the rate of Rose Mary’s menu development moving forward, but the idea of creating a “common identity” and synergy between the two properties seems smart. The concepts are located only a few blocks away from each other, and providing the chef with a second creative outlet should empower greater distinction between the “meat and potatoes” fare at BLVD and more decidedly Croatian-Italian comestibles back on Fulton Street.

With so many positive developments to speak of, Rose Mary remains a runaway popular success—boasting a 4.5 average on Yelp (348 reviews), a 4.5 average on Google (562 reviews), and a 4.8 average on OpenTable (1,611 reviews)—but something of a black sheep for “professional” critics and influencers.

No doubt, the restaurant proved impossible to get into for many months after opening. That tends to upset people who derive social status from being seen at the hottest venues at the most opportune time. Rose Mary, apart from conducting a standard “friends and family” rehearsal, did not—as far as you know—kiss the rings of the influencer class so that they may get there first and coronate it. The city’s social media “elite” was forced to scrum for a seat at the bar or book a table 60 days in advance like everybody else. By the time these ghouls arrived—a day late and a dollar short—their self-importance predisposed them to negativity. Their only winning move, so late in the game, was to go against the hype: ordering a couple dishes to nitpick and gleefully declaring they would never return.

Fellow sycophants—desperately seeking an excuse not to brave the same wait, the same galling (to them) lack of favoritism—ate these superficial appraisals up and echoed them. Despite being a hometown hero, Flamm’s Top Chef stardom seemed like a double-edged sword. Critics shackled the chef to hackneyed notions of “authenticity,” ignoring the larger value of delivering a singular Croatian-Italian hybrid to the mainstream. They seemed eager to brand the restaurant as little more than a tourist trap for tasteless television viewers. (These same people, mind you, ate up the atrocious Alla Vita—a cynical BRG cash grab disguised, rather poorly if you might add, by Kehoe’s drabby decor).

Personally, you had no issue making Rose Mary reservations from the very beginning. Yes, you staked out the restaurant’s OpenTable page and had your pick of the litter before it was formally announced that the books were open. But this kind of sleuthing (that is, keeping tabs on the various websites an establishment may use to offer tables) seems like the very least someone who butters their bread by dining out should learn to do. Otherwise, the constant churn of content creation quickly spurs desperation, the lowering of critical standards, and the descent into total hackery.

Nonetheless, you suppose you can sympathize with those critics who, dining at Rose Mary, were expecting something closer to Spiaggia. (Of course, none of the press surrounding Flamm’s new venture signaled that those expectations were justified). Seeing a chef of such virtuosity aim more squarely at pleasing the mainstream when Chicago suffers a dearth of refined Italian cuisine could, to some, seem like a cop out. When he applies a Croatian twist without prostrating himself before “how it’s supposed to be done,” it might seem like little more than a gimmick.

Your experience of the restaurant—that is, a kind of joyous group dining that encompasses the full breadth of menu on any given evening—would dispel those preconceived notions. Yet that demands good faith engagement with the actualized concept (“Adriatic drinking food” in a friendly setting) rather than clutching onto some thought of what the chef should be doing. And you understand the extent to which content creators will contort themselves to disparage anything judged too popular—and not fashionable enough—for their rootless, tasteless lemmings.

But Flamm, being the amiable man that he is, answered his doubters’ prayers. On April 26th, Rose Mary announced the launch of its Chef’s Counter: “an intimate and interactive way to experience” the kitchen’s “expression of micro-seasonality” through “a regularly rotating tasting menu that changes along with the Midwest’s freshest ingredients.” Officially, the menu was billed as a collaboration between Flamm and his chef de cuisine: formerly Brian Motyka—who left to become Longman & Eagle’s executive chef in late July—and, currently, Trevor Brossart.

These dinners would comprise only six seats ($195 per head), offered for just two seatings (6:00 PM and 8:30 PM), on Fridays and Saturdays from May through October. (Out of season, the stools along the counter would revert to their usual role: offering front-row seating for special guests who, nonetheless, would be ordering à la carte like everyone else).

Choosing to only offer Rose Mary’s highest expression of dining throughout half the year first struck you as strange. You expected the Chef’s Counter to be a perpetual booking—a fuller realization of the concept that had finally taken shape—and hearing it would shut down at the end of the month almost sounded like a failure to launch. But Flamm, during your latest meal in the tasting menu format, seemed content to reflect on the work he had done and think about how 2023’s rendition might look.

The November cutoff, in effect, ensures that the tasting menu actually remains rooted in “the Midwest’s freshest ingredients” and evokes a sense of place—rather than cobbling together totemic luxury ingredients sourced from malevolent purveyors for a contrived “premium” experience. It also streamlines the restaurant’s operation heading into Chicago’s slower winter months, a blessing once you learn the level of care that goes into developing each weekend’s dishes.

As the first year of the Chef’s Counter at Rose Mary draws to a close, you think it is well worth sharing your thoughts on Flamm’s new, ultimate offering. Despite escaping any broader media attention, these menus add a dimension to the restaurant that—at least in their aspiration—knock on the door of “proper” fine dining. At the same time, the workings of the meal—situated at the very nexus of one of the city’s busiest dining rooms—are totally unique. There is nothing in Chicago quite like it, and the chef could not have found a better way to both satisfy—and subvert—the expectations of those who callously counted him out from the start.

You have eaten at Rose Mary’s Chef’s Counter three times this year, spanning a period from mid-July to mid-September. As is standard, you will condense the sum of your experiences into one cohesive narrative.

With that being said, let us begin.

On those Friday and Saturday evenings spanning late spring, prime summer, and early fall, Fulton Market absolutely buzzes. With Time Out Market and LÝRA to the east—and a trio of Alinea Group properties to the west—Rose Mary is perfectly situated among the crowd of revelers that flows from one end of the district to the other.

But, with construction yet to begin on the new 11-story development located kitty-corner to his restaurant, Flamm’s block feels abnormally tranquil. That empty lot—and the Vital Proteins office (complete with gaudy street-level advertising) located across the street—make Rose Mary the undisputed star of the intersection. The restaurant’s patio may not eclipse those of its neighbors when it comes to size, but it sets the tone for this small slice of the city.

Already before 5 PM, a dozen would-be diners line the sidewalk running north up Sangamon. They’ll try their best to secure barstools or tables outside, and some lucky proportion will succeed—sneaking themselves in where those lacking reservations fear to tread. By 6 PM, however, the crowd has been quelled. The earliest of the walk-ins are snugly seated, and those who booked in advance have taken their spots at various chairs and banquettes throughout the dining room.

The restaurant hums along: drinks have been poured and the kitchen has sent its first waves of food. Aproned servers attentively patrol their sections—occasionally lunging up and over an open window to access their patrons on the patio. Meanwhile, back at the bar, any overflow is kept at bay by the host stand. They don’t let you breathe down other guests’ necks as you wait to relieve them of their coveted spots. Rather, the area is kept clear so that noise levels are moderated and the flow of people within the space is maintained.

Nonetheless, Rose Mary’s tavern energy can be felt from the street. The restaurant does not ring with the raucous chorus of aimless imbibers, but of clinking plates and glasses as guests enjoy a hearty meal. Nobody strains to command the staff’s attention or flash the priciest bottle of wine. Customers simply share smiles and laughs punctuated by the occasional plate of pasta. The place still gets loud—but not obnoxiously so.

Meanwhile, the dining room’s lighting remains brighter than many of its neighbors. This becomes increasingly apparent as the sun goes down, and the customers—viewed from the street—seem preserved in amber. Smartly dressed and mechanically proficient, their presence suggests this is a serious restaurant that privileges the perception of its food rather than consciously reaching for any “nightlife” chops (and the easy money that entails).

The interior exudes warmth and ease with a wink at tradition. Furniture feels sturdy—the arrangement of seating spacious—and any sense of exclusivity only comes by way of a larger popularity. Everyone, to that effect, is made to feel welcome. And everyone receives service of charm and precision—flavors of comfort and concentration—once they secure a place in Flamm’s sanctum.

Getting that foot in the door, you have already noted, forms the hardest part of the equation. Which makes strolling into the packed restaurant at 6 PM feel so particularly appealing. You meet the hostess’s eye and give her your name. She asks you to wait for a moment while they check that the place settings have been arranged. Not thirty seconds later, another host approaches and whisks your party away.

He guides you through the packed house, tracing a path through the heart of the dining room. The other guests, enjoying their meals, wonder just where this large party might be deposited. You approach the kitchen’s pass, turn, and follow it down to the corner. It looks like the host might be heading towards the back room. But he stops, turns, and ushers your group into the six awaiting chairs. The onlookers’ curiosity hardens into jealous stares. Nobody likes the feeling—when at long last savoring a coveted reservation—of playing second fiddle to some other, more superior experience. Yet, with Alinea’s kitchen table, Oriole’s kitchen table, and Smyth’s chef table all now offered at a higher ticket price, the feeling is becoming more familiar. Nesting a super-premium product within the “standard” luxury environment ensures that gnawing feeling of status insecurity—for those so afflicted—never really goes away!

Nonetheless, once you take your place at the counter, any sense of the other customers recedes. Three of the six chairs face forward, providing a close look at the staging area for the restaurant’s desserts, as well as the station that fries the chef’s popular “Zucchini Fritters” (more on those later). The remaining three seats look back across the front pass and out the window onto Sangamon. They enjoy a fine view of the kitchen’s charcoal grill, as well as the steady stream of bussers that come to transport its finished plates.

Flamm, on each of your three visits to the Chef’s Counter, has occupied the L-shaped corner where the two banks of chairs meet. Whether sharing the space with other patrons (four of you, two of them on one occasion) or buying out all six seats (as you were lucky to do the other times), you are treated to one of Chicago’s most intimate dining experiences. Guests are not sequestered behind glass or situated many paces away at a “kitchen table” that, quite literally, offers little more than a peek at the action from somewhere only technically inside the room. Rather, the chef remains within touching distance for most of the evening. He warmly hosts you in an almost uninterrupted fashion—only leaving here and there to rub shoulders with his other tables—as if your party had stepped into his home.

By your measure, Rose Mary’s Chef’s Counter seems more akin to the city’s omakases than the premium seats offered by its fine dining mavens. At the same time, it feels more warm and cozy than somewhere like Mako: a soulless, expansive bar where you are lucky to ever interact with the chef (and not his apprentice or apprentice’s apprentice) despite the ticket price. No, Flamm’s counter can be more easily compared to Yume or Kyōten—in terms of total size and the degree of interaction. But you also are reminded of Blanca, the two-Michelin-star tasting menu spot ensconced within Roberta’s sprawling Bushwick compound. Few places capture the same juxtaposition of widely pleasing, approachable food with thoughtful, refined fare. And few stage such a singular, personal experience within a concept that is already massively popular in its own right.

This is all to say that taking your seat at Flamm’s counter feels special. It may even border on being intoxicating. For those six seats do not offer a compartmentalized, voyeuristic perch from which to sneer at the suits, dresses, and shoes of other well-heeled (though not quite well enough) patrons. Instead, you are woven into the restaurant’s very nerve center and looked after like a regular at a neighborhood haunt—whom, on this occasion, has their menu taken away to be invited into the back and fêted in accordance with the chef’s whims. You feel like a friend of the house more than you do a cloistered “VIP,” and you appreciate the easy discourse that flows—free of any pomp or circumstance—with one of the city’s most famous culinary figures.

When Flamm is not engaging you—as craftsman, comedian, oenophile, raconteur, or celebratory shot-pourer (depending on the particular moment in the evening)—it pays to be a fly on the wall. You may spy how those patrons seated at the tables closest to the kitchen giddily ogle the Top Chef, how the unhurried walks he takes through the dining room spur ripples of starstruck smiles (and the occasional request for a picture). You also get some sense of the back of house’s team spirit and the playful banter that presides over their perpetually packed stoves. Flamm may have the stardom, but his whole team brims with a cheery attitude that, when they are not keeping pace with an avalanche of orders, adds a whole other layer of charm to your evening.

Truth be told, all of the action does sometimes get a little too loud to hear what the chef is saying. But those moments only make up a tiny fragment of your total interaction, and you would not trade away the visceral nature of the experience for a few more morsels of legible description. As far as a sense of occasion goes, the Chef’s Counter is enlivened not by the hushed tones and synchronization of the stereotypical fine dining setting, but by all of Fulton Market’s flowing weekend energy. As far as luxury goes, Rose Mary delivers the only kind that counts: intimate attention from a master of his craft who, for all the media hoopla, treats you like more of a friend than a fan.

However, taking one of those half dozen seats for yourself, the meal begins innocuously enough.

While, on some occasions, the chef waits in the front of the pass to greet you as you walk over to the Chef’s Counter, Flamm may otherwise offer your party a formal greeting once it gets situated. The server for the evening, likewise, comes by and offers a choice of still or sparkling. They sing the praises of the tasting menu’s optional wine pairing but, otherwise, leave you to scan the QR code “coaster” that lies before you.

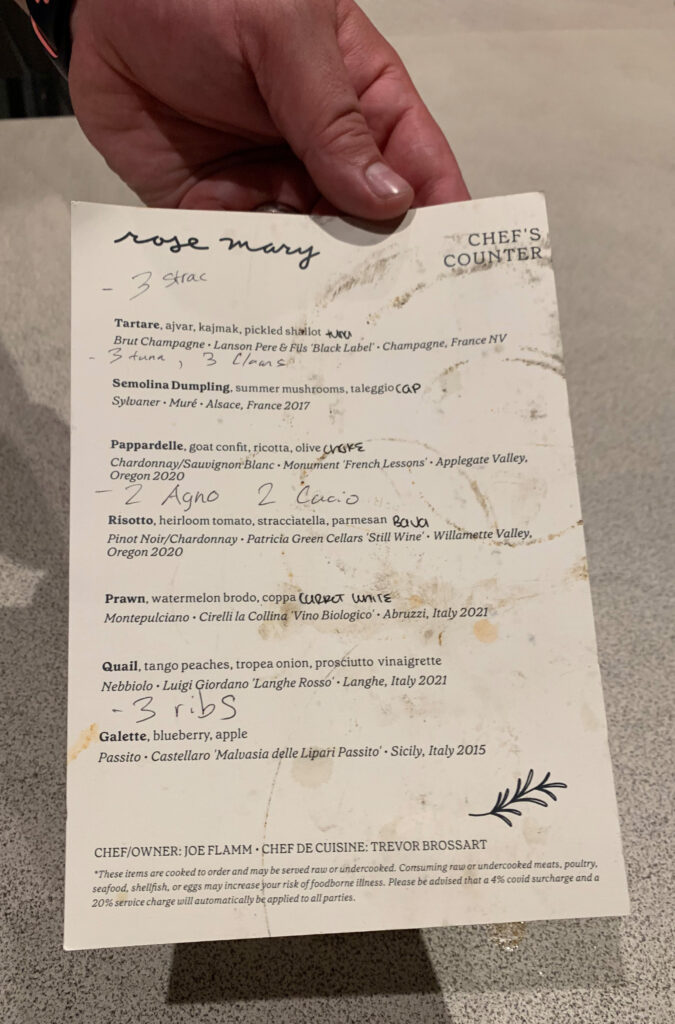

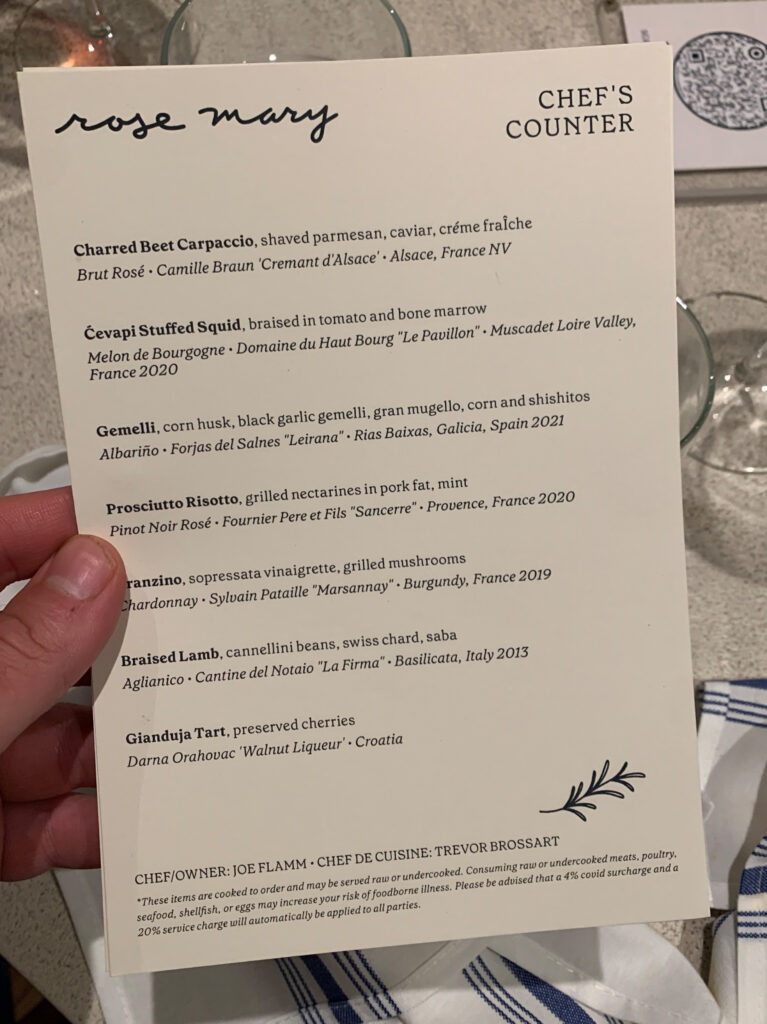

You have already pointed out some of the notable additions to Rose Mary’s bottle list over the past year, so you will direct your attention solely to the pairing. As best as you can recall, it costs a little under $100 (relative to the $195 menu price) and comprises seven pours to go along with seven courses. Though you only sampled the pairing on one occasion, your menus from all three meals list the chosen wines. Thus, you will transcribe them all in turn.

Meal 1 (mid-July):

- NV Lanson “Black Label” Brut Champagne (50% Pinot Noir, 35% Chardonnay, 15% Meunier)

- 2020 Forjas del Salnés “Leirana” Rías Baixas (100% Albariño)

- 2020 Château la Rame Bordeaux Blanc (100% Sauvignon Blanc)

- 2020 Château de Trinquevedel Tavel Rosé (60% Grenache, 13% Clairette, 13% Syrah, 10% Cinsault, 3% Mourvèdre, 1% Bourboulenc)

- 2020 Cantina di Montagna “Cembra” (100% Schiava)

- 2016 Château de Lescours Saint-Émilion Grand Cru (80% Merlot, 10% Cabernet Franc, 10% Cabernet Sauvignon)

- Darna “Orahovac” (Croatian walnut liqueur)

Meal 2 (early September):

- NV Lanson “Black Label” Brut Champagne (50% Pinot Noir, 35% Chardonnay, 15% Meunier)

- 2017 René Muré Sylvaner

- 2020 Monument “French Lessons” (60% Chardonnay, 40% Sauvignon Blanc)

- 2020 Patricia Green Cellars “Still Wine” (55% Chardonnay, 45% Pinot Noir)

- 2021 Cirelli la Collina Biologica “Vino Biologico” (90% Montepulciano d’Abruzzo, 10% local varieties)

- 2021 Luigi Giordano Langhe Rosso (90% Nebbiolo, 10% Arneis)

- 2015 Tenuta di Castellaro Malvasia delle Lipari Passito (95% Malvasia delle Lipari, 5% Corinto)

Meal 3 (mid-September):

- NV Camille Braun Crémant d’Alsace Brut Rosé (100% Pinot Noir)

- 2020 Domaine du Haut Bourg “Le Pavillon” (100% Melon de Bourgogne)

- 2021 Forjas del Salnés “Leirana” Rías Baixas (100% Albariño)

- 2020 Fournier Sancerre Rosé (100% Pinot Noir)

- 2019 Sylvain Pataille Marsannay (100% Chardonnay)

- 2013 Cantine del Notaio “La Firma” Aglianico del Vulture

- Darna “Orahovac” (Croatian walnut liqueur)

Considering that purchasing the Chef’s Counter’s wine pairing is completely optional (unlike premium experiences at Smyth and Alinea that demand customers commit to “reserve” or higher flights), Rose Mary’s wine director needs to work within a certain range of value. Serving half-glass pours to 24 guests across four seatings on two sequential evenings roughly amounts to opening two of each chosen bottle. When a larger party like yours decides to order its own selections from the list, the restaurant may come out ahead in the aggregate but be saddled with some amount of leftover wine intended for the pairing. Topping off other guests’ glasses is certainly an option (and a nice gesture of goodwill). However, any wastage works to undermine the counter’s overall value proposition, and the bottles offered—thus—must help mitigate this risk.

That being said, you think the pairings are savvily chosen and speak to the bespoke nature of each weekend’s menu. Further, the restaurant avoids serving any of those ubiquitous producers that other establishments thoughtlessly draw upon to offer value. Yes, there are a couple repeats—the Lanson, considered one of the best Champagnes at its price; the Albariño, though offered in separate vintages; and the Croatian walnut liqueur, a thematic choice you think is worth preserving—but the active collaboration between chef and wine director is clear. (Flamm, to his credit, tries every selection that hits the list—something you otherwise have only heard of Otto Phan doing).

Looking across the three menus, you find the transition from sparkling wines into aromatic white varieties (like Albariño, Sauvignon Blanc, or Melon de Bourgogne), white blends, rosés, and non-aromatic white varieties (like Chardonnay) to be well executed. This ensures that the meal’s first few dishes are accompanied by soft, expressive grapes that smoothly yield to bottles of more driving acidity and tannin. Likewise, there is typically a nice transition from lighter reds (such as the Schiava or biodynamic Montepulciano) into more robust wines (made from Merlot or Nebbiolo).

Still, this hardly reflects a paint-by-numbers approach: consider a branzino (from Meal 1) paired with the cotton candy-like Schiava versus another branzino (from Meal 3) paired with Pataille’s opulent Marsannay blanc. Or, perhaps, consider the transition from Meal 3’s Sancerre rosé into Chardonnay and then back into a weighty Aglianico. On this basis, you have found the Chef’s Counter pairings to be not only a good value, but technically sound and distinctive too. Few Chicago restaurant experiences enable such a dynamic interplay between wine and food—a union that honors the craft of hospitality by transcending any temptation to reduce the beverage into a mere money-making product.

In practice, you think the pairing is a good option for larger parties or wine philistines who do not want to get bogged down browsing the full list. Personally, you often choose to supplement the restaurant’s pours with a couple additional bottles of bubbly, white Burg, or rosé. This ensures that your guests have something to sip on at their leisure that is unattached to any particular plate of food. It also allows you to share a toast with your host and chef—a gesture he willingly receives and that helps cement the sense that you are being cared for as if seated in someone’s home.

Nonetheless, those with the time or temperament to engage with Rose Mary’s bottle list in advance will find themselves rewarded. The online document is frequently updated—a rarity in Chicago. And the cost of several pairings can easily be put towards purchasing three or four pleasing wines that suit your particular tastes. (Likewise, the list’s finer offerings will find no better occasion to be enjoyed than when placed alongside one of Flamm’s tasting menus).

With the drinks settled, the meal seems set to begin. However, you have found that the Chef’s Counter experience allows (and, once you got in the habit, even encourages) the addition of à la carte dishes should you so choose. And this calm before the storm proves to be the most opportune moment to make those selections.

For the majority of patrons, this will likely prove unnecessary (and, thus, is no indictment of the portion sizes). It may even seem shocking—judging by the (playful) reaction of the other parties that have joined you for the dinner—that a tasting menu need be supplemented. But this opportunity to taste some of your favorite fare (or, for the first-time visitor, get a sense of what the normal offerings are like) represents a huge bonus for those who, though desiring the chef’s best expression, feel constrained by strictly set coursing.

Flamm simply demands that the kitchen have enough forewarning to meld the additional items with the rest of the meal. It accomplishes this in such a way that—even if you are joined by strangers at the counter—they will never be left waiting around for the next course of the tasting menu while watching you eat your extras. Rose Mary deserves high praise for this degree of flexibility. It affirms that the Chef’s Counter represents the restaurant’s ultimate expression of hospitality, and that no holds are barred when it comes to delivering anything and everything its guests desire.

Now, at last, the tasting menu begins, and each meal begins in roughly the same way.

Flamm fills a few ramekins from a large container of olive oil. He cracks a bit of pepper therein and deposits them in front of his eager patrons. To go along with the oil, the chef presents a couple thick slices of housemade focaccia that have been assertively charred on the outside. Guests are invited to dip the bread into the accompanying ramekin as an opening nibble.

But, just as you start to tear into the focaccia, Flamm returns bearing a wooden board containing a couple more opening bites. The first—prosciutto wrapped around a piece of cheese, melon, or both with a drizzle of balsamic—forms a classic antipasto. The second—a miniature rendition of Rose Mary’s hallmark “Zucchini Fritters”—represents something of a concession. The chef noted how the first guests to indulge in the Chef’s Counter menu spent the whole evening drooling at the station devoted to frying this signature item. Thus, he thought it would be a nice gesture to satisfy this craving at the start.

This selection of finger food forms the opening sequence of the evening; however, it does not count towards the menu’s seven courses. Rather, the bread and oil cement—once more—that feeling of being hosted at home. They are offered up in a casual, utterly captivating way that in no way discounts their quality. The focaccia balances a soft, airy crumb with a crispy crust and a subtle bitter note from the outer layer of char. This carbonized dimension melds beautifully with the oil, which is not only invigorated by the black pepper but, itself, possesses a powerfully fruity flavor enlivened by its own vein of bitterness (a mark of high quality).

Offering prosciutto with cheese and/or melon is certainly totemic for Italian culture, but this delight extends to Croatia too. Originally, the bite only comprised ham wrapped around a sliver of Pecorino. Then, on the second occasion, the prosciutto was wrapped around a cube of cantaloupe. Finally, the third time, it combined cheese, fruit, and a leaf of basil to make a complete package. The balsamic (present throughout all three versions) serves well to bridge the tanginess of the Pecorino with the sweetness of the melon. Yet that eternal interplay—of salty prosciutto and gushing cantaloupe—forms the core attraction. The cheese and basil, in the third and best rendition, adds a nice layer of complexity to this essential combination. And you think the bite, despite its relative simplicity, deserves credit for being so nicely concentrated and arranged.

The ”Zucchini Fritters,” meanwhile, require no introduction. These crispy morsels—laced with parmigiano and pine nuts then topped with a pesto aioli—taste as great as ever. However, their smaller size (and the added care you think goes into getting the frying just right) makes for a superlative example of the form. The fritters are brought to that deep, dark golden-brown tone that borders on black, making for an astounding degree of crunch that reminds you just why this recipe is so special.

As the opening bites are finished and cleared, Flamm sets about plating the first course of the meal proper. During your original visit, that comprised “Scallops” served with grilled blueberries, pickled turnips, and tarragon.

The dish arrives in a small bowl with the fruit on the bottom, two of the bivalves on top, and a scattering of turnip pieces and tarragon leaves as a garnish. The scallops boast a nice outer crust, but are also of a smaller circumference and larger width than are typically seen in so-called “entrée” preparations. This ensures they retain a soft, gushing quality that you have come to prefer—and that plays well off of the crunching turnip and bursting blueberries.

With regard to flavor, the dish marries the natural sweetness of the shellfish with an impressive range of smoky-sweet, tangy-peppery, and anisey notes. It all sounds like a bit much, but the scallops are so pristine and texturally pleasing that they form a fitting canvas. That is in part because grilling the blueberries helps moderate their freshness and bring them towards the more savory side. Thus, the fruit transforms into globules of concentrated “sauce” while the pickled turnips bring a bit of that “squeeze of lemon” sensation to the table. The tarragon, of course, makes for a more familiar seafood accompaniment—but the character it adds to the dish’s finish ties the preparation up in a bow. For the middle of July, this was both a bold and elegant way to start the dinner off.

During your second visit, the meal began with a “Tartare” that Flamm cleverly terms a “deconstructed ćevapi.” Given that the chef’s more conventional “Cevapi” has featured on Rose Mary’s menu since opening, this description, you think, really highlights the contrast between the restaurant’s more rustic à la carte offerings and the kind of work done at the Chef’s Counter. It demonstrates, for those who think the Top Chef winner has no claim to serve Croatian cuisine as such, that he can playfully reinterpret and reimagine its dishes. And that, perhaps, will placate some of the “critics” whose wayward expectations—rooted in hackneyed notions of “authenticity”—poisoned any appreciation of the concept.

But how did it taste? The “Tartare” combined glistening chunks of hand-cut beef with a runny sauce made from kajmak (a fresh cheese also called “the clotted cream of the Balkans”) and a smaller dollop of ajvar (a condiment made from red bell pepper and eggplant). The dish is garnished with pickled shallot and flat-leaf parsley then served with a toasted heel of the aforementioned focaccia.

Texturally, the beef feels smooth and rich when it hits the palate. Much of this has to do with the kajmak, which offers the meat a creamy, milky coating that enhances its succulence. Of course, the pickled shallots and toasted bread offer a relieving crunch. But the ajvar, with regard to flavor, really carries the dish. The pepper condiment brings sweet and smoky notes to the table that help ground the sour, tangy character of the cheese and the pickles. The balance this combination forms—along with slight peppery tones from the parsley—makes the beef taste bold and lip-smacking. This is quite a nice tartare that honors the restaurant’s overarching theme while refining some of its signature flavors.

Lastly, on your third visit, the meal’s first course comprised a “Charred Beet Carpaccio.” With regard to presentation, this dish may be the prettiest of the bunch. It comprises six thin slices of the root vegetable arranged around the center of a plate. They are drizzled with wild streaks of crème fraîche and a couple dots of olive oil. The carpaccio is then garnished with some grated parmesan, sprigs of dill, and a nice dollop of caviar.

Diving in, you find this dish to be more texturally nuanced than either the “Scallops” or “Tartare.” The thin slices of beet, glazed with cream and oil, form a delicate cushion for the orbs of roe. That caviar—though of uncertain origin and ordinary quality—colors the dish with a pronounced briny quality that works well against the supporting flavors. That includes the earthy, sweet, and slightly bitter carpaccio—as well as the tangy-nutty parmesan. The sour crème fraîche and grassy dill, meanwhile, form a familiar pairing. So, the preparation amounts to something like a soft, cheesy beet “chip” dressed with caviar that, in turn, “salts” the root vegetable to help reveal its depth of sweetness. Achieving that balance, despite beets’ ubiquity in fine dining, is harder than it sounds. The chef utilizes the ingredient artfully to craft a plate of fine detail and restraint.

The second course of the evening, going back to your first Chef’s Counter meal, centered on “Grilled Peach.” The fruit is cut into a few large chunks and tossed, along with a tangle of purslane, in olive oil. This resulting salad is placed at the bottom of a plate and topped with freshly pulled strands of stracciatella (the same cheese that features in the titular à la carte dish). The preparation is then finished with a garnish of toasted pine nuts and a dusting of fennel pollen.

While beautiful in its simplicity (fresh fruit, greens, and cheese), this dish offers surprising depth. Texturally, the pieces of peach are plump and juicy. The stracciatella coats them like a kind of “cream” while the stemmy purslane and bits of pine nut offer a contrasting crunch. With regard to flavor, the peaches display a caramelly concentration of sweetness by way of their grilling. This joins with the sour notes of the purslane, soft nuttiness of the pine bits, and anisey, citrusy character of the fennel pollen. The stracciatella, while mildly sweet in its own right, helps meld the other ingredients. It sops up the juiciness of the fruit, extending its presence on the palate and allowing the supporting flavors to shine through the finish. This dish stands as a testament to Flamm’s light, prototypically “Italian” touch and his reverence when featuring products at the peak of their season.

The second course of your second Chef’s Counter experience stands as one of your favorites across all three meals. It comprises a neat, rectangular “Semolina Dumpling” that sits at the bottom of a shallow bowl. This soft, smooth canvas is topped with a hearty scoop of “summer mushrooms” (what look like chanterelles, trumpets, and/or oysters) that have been sautéed in butter. Then, at last, the chef tops the dish with a sauce made from Taleggio cheese.

Given that the dish revolves around such a large serving of what is, in effect, flavorless starch, the other components must be perfect. Flamm’s mushrooms do not only display an appealing crunch, but they resonate with a rich umami flavor that only freshly foraged product can provide. The earthy, meaty character of the fungi melds beautifully with the subtly tangy and fruity Taleggio. Nonetheless, the cheese carries quite a lasting finish. This ensures, after the smooth, nutty semolina and crisp mushrooms mingle on the palate, that some overarching flavor accompanies the last traces of the dumpling.

Overall, the “Semolina Dumpling” is perfectly constructed and pleasingly decadent. The dish is the brainchild of chef de cuisine Trevor Brossart, who—despite never working at Spiaggia—has created something Flamm thinks shares the restaurant’s signature. You could not agree more: the preparation seems straight off one of Mantuano’s tasting menus. And it reflects the kind of freedom this format offers the chef and his team. Bravo!

The second course of your third Chef’s Counter menu might have been just as strong. At the very least, in terms of construction, it is one of Flamm’s most brilliant creations. The dish is titled “Ćevapi Stuffed Squid” and represents yet another reinterpretation of the beloved Balkan street food. Rather than deconstructing the recipe into a tartare, the chef packs the body of the cephalopod with a beef and pork sausage. The squid is braised in tomato and bone marrow before being served with a drizzle of the remaining juices and some stewed red peppers—meant to replicate the ajvar condiment from before.

Diving in, you find it remarkable how snugly the squid wraps around the sausage. Cutting into the cephalopod even feels smoother than your average natural casing, a huge testament to how expertly it has been prepared. Taking a bite, the subtle double chew of the squid and its ćevapi filling is highly enjoyable. With further mastication, both components reveal their juiciness and impart a succulent sweetness. While the bone marrow adds an extra layer of richness to this equation, the tomato and red pepper elements enhance those sweet flavors with uplifting fruity and grassy notes. Flamm’s “Ćevapi Stuffed Squid” measures up to its creative presentation by offering some of the Chef’s Counter’s most refined flavors and textures.

The menu’s third course—across each of your three meals—has reliably indulged in one of the Top Chef’s specialties: handmade pasta. On the first occasion, that comprised “Goat Cheese Agnolotti” paired with slices of summer squash and zucchini in a sauce made from butter and spicy honey. While the dish’s portion size cannot compare to the heaping bowls of pasta served à la carte, the tasting menu format allows Flamm to craft preparations of particular freshness and finesse.

Each of the half dozen agnolotti are formed into neat rectangular pouches crimped with triangular “teeth.” Upon meeting the palate, the pasta displays a soft exterior that yields to a subtle chew once struck by your teeth. As molten goat cheese oozes from the interior, it encapsulates the dough and joins with it to form a pillowy mouthfeel supported by just enough glutinous structure. The coins of summer squash and shards of zucchini that join the agnolotti in its bowl offer a crunchy, gushing counterpoint to the dish’s principal component. They also deliver a mildly sweet, slightly grassy flavor that works well with the tangy goat cheese.

But it’s the sauce’s spicy honey component that brings everything together. The mix of heat and sweetness underscores the natural sugars of the squash while serving to accent its more watery character. Likewise, the honey tames the goat cheese’s sharpness and constructs a balance of flavors that is spicy, tangy, and earthy in turn. Ultimately, the dish’s sweetness wins out and establishes an overarching sense of decadence that keeps you coming back for another bite. This enhances your perception of the agnolotti’s texture even more, making for an elegant vegetarian pasta that—in your opinion—surpasses the “Tortellini Djuvec” Rose Mary has served on its menu since opening.

The third course of your second Chef’s Counter experience took quite a different tack. Rather than offering stuffed pockets of agnolotti, the dish comprised fresh ribbons of “Pappardelle.” Rather than presenting a vegetarian ode to summer squash and zucchini, the preparation gave pride of place to confit goat. Flamm explained to patrons that he had brought the whole animal into the restaurant as a teaching opportunity for his team. The chef demonstrated how to break down the carcass’s various cuts and, in a subtle nod to his time cooking for Stephanie Izard at Girl & the Goat, would then incorporate them on the tasting menu from week to week. In this case, that meant a pasta studded with strands of meat and some olives, whipped ricotta, and grated parmigiano.

Diving in, you find the pappardelle themselves to be utterly captivating. The noodles possess a width, weight, and glossiness that belies their absolute delicacy. With each bite, the pasta dances across your tongue—offering a wee bit of resistance—until it melts and melds with the other components. The tender bits of goat, smooth ricotta, and accompanying butter sauce match the pappardelle’s slick exterior. However, the grains of grated parmigiano, halved segments of olive, and stalks of chive interlaced throughout the dish work to accentuate these smoother textures by their contrast.

When it comes to flavor, the goat’s gamey quality is subsumed by the bitterness of the olives and the richness of the ricotta. This makes for a combination that is boldly meaty and cheesy but altogether pristine. Thus, you may appreciate the noodles’ texture—offset by plenty of butter and parmesan—without contending with any forceful accompanying notes. Rather, the confit goat, olives, and ricotta offer a layered, lasting, and balanced flavor profile that counterbalances the dish’s richness and holds your palate’s attention through the last bite. While you are a fan of the mafaldine and spaghetti offered on Flamm’s normal menu, these pappardelle are particularly special—offering the same degree of indulgence as the chef’s famous gnocchi in an even more nuanced noodle form. Do you dare dream of the day they may be offered, in some form, à la carte?

As great as the “Pappardelle” were, the third course of your third tasting menu experience gave it a real run for its money. Rather than wide noodles, the dish comprised the twisted pasta shape known as “Gemelli” (or “twins”). The dough they were made from, in this case, was flavored with black garlic (which also lent it a dark tone). The gemelli were then paired with shredded Gran Mugello cheese, sliced shishito peppers, and bits of corn at the very peak of its season.

Attacking the dish, any piece of pasta you prick is sure to bring a mound of the Gran Mugello with it. The Tuscan cow’s milk cheese is “massaged each day with local extra virgin olive oil,” yielding a flavor profile that is mildly buttery with lasting fruity and nutty tones. But, in practice, the gemelli bounce against your teeth and take on a coating of the shredded, melting cheese that displays, at first, little intensity. The Gran Mugello sits in the background as the crunchier bits of corn and shishito strike with their freshly sweet and peppery notes. Over time, the sweet and tangy character of the black garlic-infused dough shows itself. Then, finally, the cheese asserts its personality through the finish.

Ultimately, you would describe the “Gemelli” as something of a delayed fuse. That is to say, the dish seemed extroverted on the surface but was sneakily all about depth. You expected the preparation to burst with notes of corn and offer an enrapturing sweetness from beginning to end. Instead, it was only after a few bites that the pasta’s pleasing textures and comparably muted flavors made sense.

The corn and shishito pepper form the dish’s entry point, and their core of sweetness gets expanded upon over time. The black garlic, with its concentrated umami, imbues the vegetables with a darker, roasted character. Likewise, the Gran Mugello rounds the other ingredients out with a pronouncedly buttery, transfixingly ripe quality. But these elements only harmonize as the aftertaste of a few bites finally grips you. Then, sensing how the fresh corn is “grilled” and “buttered” by the accompanying black garlic and cheese, you dive back in for another round. The finish of the previous bite alters your perception of the next, and each dimension grows more and more in intensity until you are left with nothing but their remembrance. This is quite an intelligent dish that speaks to just how creative the Chef’s Counter menu can be. And it ranks as one of the most singular pastas you have ever seen Flamm prepare.

Just as the third course of the Chef’s Counter experience is devoted to pasta, the fourth course has reliably showcased risotto. That makes sense given the dedicated section that the rice dish, offered three different ways, has occupied on Rose Mary’s menu since opening. However, as with the aforementioned agnolotti, pappardelle, and gemelli, the tasting format empowers the chef to craft preparations of particular depth and creativity when compared to the à la carte offerings.

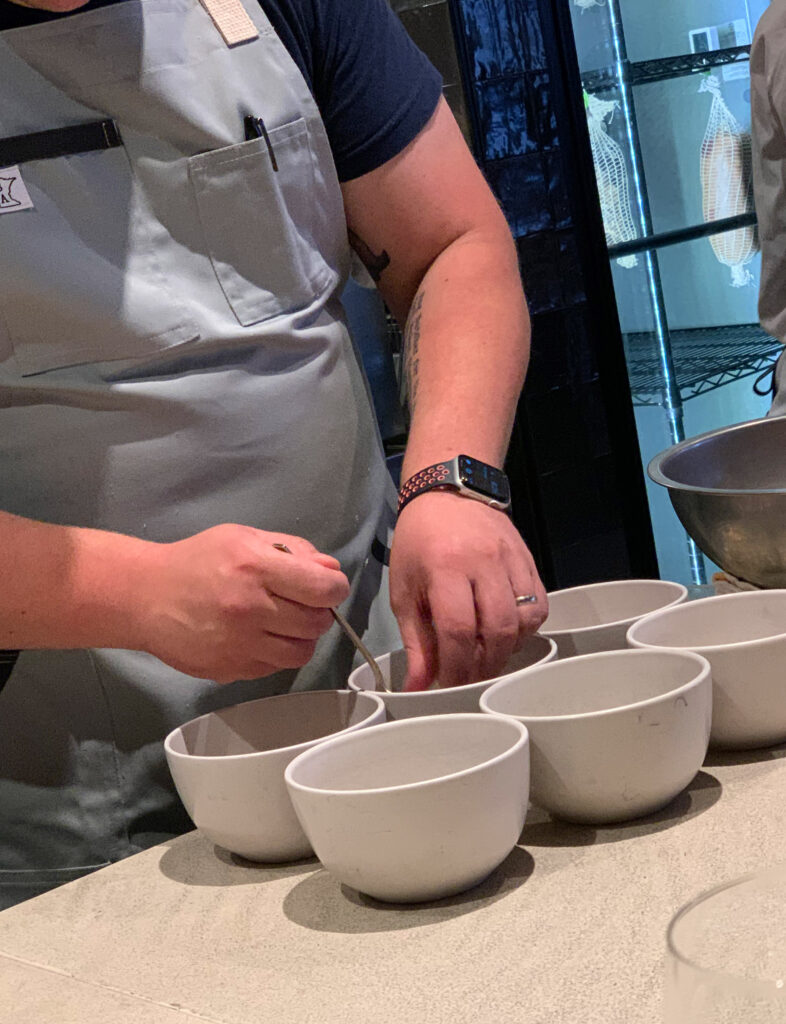

This began, on the occasion of your first meal, with a “Lamb Risotto” that was paired with fava beans, pickled Tropea onions, and nasturtium. Structurally, the favas were incorporated in with the rice at the bottom of the bowl—hiding among the grains and lending them a faint green hue. Then, tender shreds of slow-cooked lamb were spooned on top, bringing a reservoir of pan juices along with them. Finally, a few circular segments of the onion and leaves of the nasturtium complete the presentation.

Tucking into the dish, you are first struck by the risotto’s texture. Its grains feel smooth and creamy on the tongue—representing the height of Rose Mary’s technical prowess—while blending in effortlessly with the buttery fava beans. The lamb, too, displays an appealing softness, meaning that the strongest contrast is drawn from the faint crunch of the pickled onion and nasturtium. With regard to flavor, the preparation revolves around that classic combination of nutty, earthy favas with grassy, gamey lamb. The rice, soaked in the meat’s juices, resonates with an added layer of carnal depth. Meanwhile, the sweet-sour Tropea onions and peppery nasturtium leaves do their part to relieve you from the richness. This is a classy, well-executed dish that ranks above the restaurant’s more familiar risottos but lacks, perhaps, just a bit more inventiveness to really shine.

The fourth course of your second meal comprised a simply titled “Risotto” distinguished by strands of stracciatella, halved segments of heirloom tomato, a leaf of basil, and parmesan. Most interestingly—as with the lamb’s pan juices in the previous dish—the rice was flavored using the cheese’s milky runoff. That joined with some dots of olive oil and cracked black pepper to provide the dish’s grounding. In effect, the preparation reminded you of Rose Mary’s actual “Stracciatella” appetizer—only deconstructed and reconstructed in much the same way Flamm has treated his “Cevapi.” Nonetheless, it must be said that combining a cold salad with a warm risotto is quite bold.

Diving in, the rice grains in this dish display a nice tenderness; however, they are held together much more loosely and lack the creaminess of the previous example. That seems intentional, for the stracciatella strands melt into the risotto and imbue it with a greater degree of body. When the cheese joins with the rice and the milky discharge at the bottom of the bowl, the sum effect comes closer to the smooth, full texture you are used to. From this foundation, the heirloom tomatoes strike: bursting on the palate and releasing their juices. The resulting acid and sweetness join with the latent sour flavor drawn from the stracciatella to flavor the rice. Notes of olive oil, black pepper, and parmesan—meanwhile—provide some savory backing. Overall, the preparation is remarkably reminiscent of the stracciatella appetizer, offering a refreshing interplay of tomato and cheese set upon a more substantial base (rice rather than lepinja in this case).

This is a clever dish that, nonetheless, would have possibly made more sense if served in mid-July (and the “Lamb Risotto,” likewise, later in September). Perhaps, within the flow of your second meal, it would have also been better served before the “Pappardelle.” But you cannot fault the chef’s desire to showcase the tomatoes in this manner, and this particular inspiration (“Stracciatella” as “Risotto”) may have only taken shape after several months of serving the tasting menu. While less straightforwardly delicious than the lamb and fava bean combination, this preparation certainly impresses with its creativity.

The fourth course of your third Chef’s Counter experience—and the final rice dish you sampled as part of Flamm’s tasting menu—was undoubtedly the best. It walked the line between the “Lamb Risotto’s” decadence and the “Risotto’s” inventiveness while also featuring a delectable surprise “sidecar.” The dish was titled “Prosciutto Risotto” and, apart from the titular cured meat, featured nectarines grilled in pork fat with a bit of mint. As an accompaniment—and just because the chef needed to show his cook how to break down a whole pig—Flamm served a rack of pork that had been Frenched and roasted. Though this item was not listed on the written menu, each patron received a neat bone to gnaw on alongside the principal dish.

Like the aforementioned lamb variant, the “Prosciutto Risotto” displays a luscious, creamy character that testifies to the chef’s technical mastery. Small shreds of the cured ham (even smaller than the grains themselves) and interlaced throughout the rice. They offer a bit of chew and a burst of salt to go along with each bite and break up the homogenous texture at hand. The chunks of nectarine, though larger than the grains, are soft and juicy. They break apart easily and—their natural tartness being moderated by the grilling—add a subtle sweetness to the equation. This helps underscore the prosciutto’s own sweet character and adds to your perception of the pork fat.

Flamm’s Frenched pork rack “sidecar,” meanwhile, is essentially a more glamorous doppelgänger of the “Pork Ribs Pampanella” the chef serves on his à la carte menu. While that dish is surely fun to nibble on (and is a must-order as far as you are concerned), these particular chops offer more meat along the bone as well as a tender medallion of pristine porcine flavor. Served with a drizzle of the same Calabrian chili agrodolce that features in the “Pampanella,” this pork rack is an absolute treat and a great reflection of the kind of generosity that reigns at the counter. Moving from the salty-sweet “Prosciutto Risotto” to the substantial, sweet-spicy “sidecar” makes for a blissful synergy. And the total naturalness with which Flamm offered such a substantial addition to the menu—just for the hell of it—made for a beautiful memory. This moment, which (for the record) you shared with several strangers at the counter, stands as a shining peak of Rose Mary’s deliciousness and hospitality.

With the two-part pasta and risotto sequence savored, you now move on to the first of two entrées. On the occasion of your first Chef’s Counter experienced, that entailed a “Branzino and Broccolini” flavored with chilis and garlic. While many of the tasting menu’s items are served in flights that facilitate a feeling of sharing, this course was the first instance in which your party actually cut apart and divided a singular serving of something. The fish, perfectly bisected and assertively charred, played its part perfectly. You found it easy to cut portions off of the fillet and deposit them, along with their topping of broccolini, onto your plates.

Relative to the “Half Branzino” (served with paprikas sauce, fennel, and charred lemon) when previously offered on the restaurant’s à la carte menu, the Chef’s Counter rendition is more simply composed. The preparation centers more decidedly on the juxtaposition between the crispness of the fish’s skin and the light, moist flake of its flesh. While the broccolini offers a crunch and bitterness that plays well with of the branzino’s outer char, the garlic and (sweet, smoky) chili components fortify the fillet’s milder flavor.

Truth be told, you find this course—though executed admirably—to be one of the tasting menu’s less distinguished offerings (at least when it comes to transcending the restaurant’s more familiar fare). Yet there is a certain rustic charm to the idea of a chef throwing a whole fish onto the grill and serving it up for his guests, as well as the act of passing the plate around and tearing at its flesh. Connecting to the open fire that blazes on the other side of the counter and picking out those prime morsels of the branzino’s cheek amounts to a valuable moment in the evening. The fish dish, as such, may not be quite as memorable, but it takes nothing away from (and maybe even benefits) the larger flow and feeling of the meal.

The fifth course of your second Chef’s Counter experience, by comparison, was so bold and distinctive that it polarized the members of your party. The dish comprised a double helping of “Prawn” draped in coppa and dunked in a watermelon brodo. The crustaceans have been grilled on the open fire and are served head-on—offering a bonus “bragging rights” bite for those who can brave sucking out the juices.

Diving in, this dish is defined by the interplay between the plump, sweet abdomen of the prawn and the salty, spicy coppa. The cold cut’s fatty, faintly chewy texture serves to extend and enhance the crustacean’s presence on the palate while the watermelon brodo, when you take a sip, offers smoky-sweet undertones that amp up its accompanying flavors. Sucking the prawns’ heads, on that note, sends the dish’s intensity up into the stratosphere. But this is a powerful, take no prisoners expression of savory flavor that could prove too intense for more delicate palates.

Personally, you love the “Prawn” preparation as a counterpoint to the more mild-mannered branzino. The sweet, salty, smoky, and spicy notes that swirl within drive the perception of each component ever higher until they attain a dizzying degree of concentration. This amounts to something like the most intensely umami flavor you can remember tasting in quite some time. That being said, you possess a rather high threshold for such full-throttle cooking, and this dish certainly pushed your palate to the limit. So, while you respect the chef for crafting something of such unabashed savory intensity, it undoubtedly carries with it a risk. (Though maybe one that only stands to overwhelm those customers who already find the cooking at Rose Mary to be on the salty side).

The fifth course of your third tasting menu saw Flamm revisit the “Branzino” with a new preparation. Instead of broccolini, the fish was joined by grilled mushrooms and dressed with a soppressata vinaigrette. Small chunks of the cured meat, as well as a tangle fresh dill, completed the presentation.

As with its previous iteration, the branzino boasts an aggressively charred skin that makes for a crisp outer texture. That gives way to the same light, flaky interior. However, while the broccolini added but one extra dimension of crunch, the grilled mushrooms and soppressata chunks provide a double layer that is soft, faintly crunchy, then chewy. This makes the mouthfeel of the fish a bit more intriguing. Likewise, the mushrooms and soppressata go beyond the previous dish’s notes of garlic and chili to offer flavors that are more substantially earthy and meaty while retaining a bit of spice. The dill, in this case, plays an important role in moderating the influence of the cured meat. But the mild branzino clearly benefits from being paired with more forceful accompaniments.

Overall, you find that the reimagined “Branzino” surpasses the “Branzino and Broccolini” from your inaugural menu—the one trade-off being that the fish now arrives without its head (and accompanying cheeks). Nonetheless, this decision probably ensures that guests can more easily divvy up the actual fillet without accidentally saddling someone with the inedible flesh around the nape. As it so happens, the “Branzino” preparation would be ported over to the à la carte menu, where it appears as a “Half Branzino” with the addition of fennel. Fennel, indeed, might have formed a better garnish than dill, yet it is worth appreciating how the Chef’s Counter dishes function as R&D for the larger restaurant. It stands as another testament to how holistically Flamm views the two concepts (while still ensuring the tasting menu feels special).

The final savory course of your first meal comprised a “Milk Braised Pork Shoulder” flavored with Dijon mustard and topped with slices of fennel and apricot. Despite your association of this slow cooking method with uniformly soft, tender flesh, the meat actually displays an admirably crisp, golden-brown crust. It crackles, crunches, and gives way to an interior that is, indeed, totally luscious. Meanwhile, the crunch of the fennel and slight firmness of the apricots provide a pair of intermediary textures that help to meld the mouthfeel of the pork with its skin.

With regard to flavor, the milk braising imbues the subtly sweet pork with an added roundness and richness that joins well with the caramelized notes of the shoulder’s crisped skin. The Dijon mustard element, being subsumed by some of the meat’s drippings, does not display much pungency. Rather, its tangy character joins with the tartness of the apricot to invigorate the dish’s porcine intensity. An undercurrent of more pronounced sweetness (drawn from the fruit) and the licorice notes of the fennel offer a bewitching finish that draws you in to take another bite. The sum effect of the meat’s accompaniments is far more nuanced than a traditional barbecue sauce, allowing the flavor of the pork itself to take center stage. This is both nicely executed and generously portioned.

For your second Chef’s Counter experience, Flamm substituted the heaping pork shoulder for a rather diminutive “Quail.” He paired the game bird with TangOs peaches—a variety known for its “100 percent yellow skin color”—as well as Tropea onion and a prosciutto vinaigrette (sound familiar?). Each guest received an entire, spatchcocked portion of the meat that sat, splayed out, in the center of a plate.

Though lacking the heft and easy charm of the pork, the chef’s quail is an ode to finesse. Its skin displays some patches of char that are so characteristic of the restaurant, yet its inner flesh maintains a softness and juiciness indicative of an expert cook. The body of the bird, thanks to the spatchcocking, is easily sliced, but so much of the enjoyment comes from gnawing on its legs. While the Tropea onions are cooked down to a degree of smoothness that matches the meat, the TangOs peach slices offer a clean, contrasting crunch.

When it comes to flavor, the prosciutto vinaigrette provides a salty, tangy, hammy dressing that plays well with the darker, slightly gamey flesh of the quail. This serves, despite the small portion size, to amplify a feeling of richness. Nonetheless, the deeply sweet onions and tangy-sweet peaches help bring this meaty character into balance. (You almost, in a way, get duck à l’orange vibes from the recipe!) This is a beautiful preparation that represents a real peak of elegance for the tasting menu.

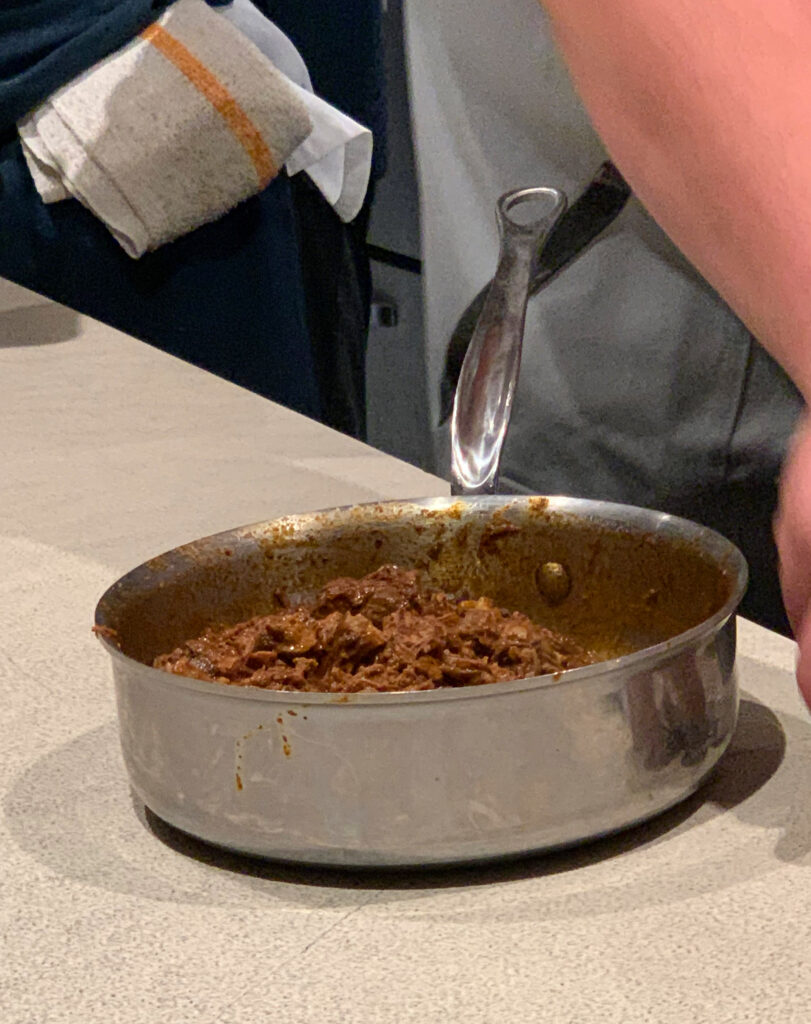

The last of the entrées you sampled at the counter, on the occasion of your third meal, sort of split the difference between the pork shoulder’s size and the quail’s concentration of flavor. It comprised a “Braised Lamb” served with cannellini beans, Swiss chard, and saba—a grape must syrup termed a “poor man’s balsamic” but that, in effect, replicates the flavors of the finest aged vinegars.

Watching Flamm carry the shank of lamb out of the oven is positively pornographic. The meat displays a deep, dark golden-brown color that is lacquered with the glossy black saba. The chef sprinkles flaky salt atop the hunk of flesh then effortlessly tears it into chunks. Meanwhile, the beans and chard, which have been sautéed in their own pan, are spooned onto the bottom of a plate. Finally, the lamb is placed atop them and given a final drizzle of the grape must syrup and just a bit more salt.

While the pork and quail dishes each drew on textural contrasts (like the apricots and peaches), the “Braised Lamb” offers a pure expression of indulgence. The cannellini beans and Swiss chard are slick, smooth, and a little creamy. The meat itself is fork-tender, and its juiciness is further supported by the syrupy saba. Thus, each of the components meld gently together and strike the palate as a unit. The gamey lamb smacks of the caramelized, fruity, and slightly acidic grape must. This hedonistic combination (that, in its own way, is not all that different from a barbecue sauce) is grounded by the earthy, bitter chard and mildly nutty beans. The latter components round out the lamb’s flavor and make for a dish that feels substantial without ever seeming heavy or cloying.

This “Braised Lamb” even improves upon the “Lamb Shoulder” (with chard and lamb fig jus) that has long featured on Rose Mary’s à la carte menu. Is it any surprise then that the preparation—in another glimpse at Flamm’s R&D process—has now replaced it?

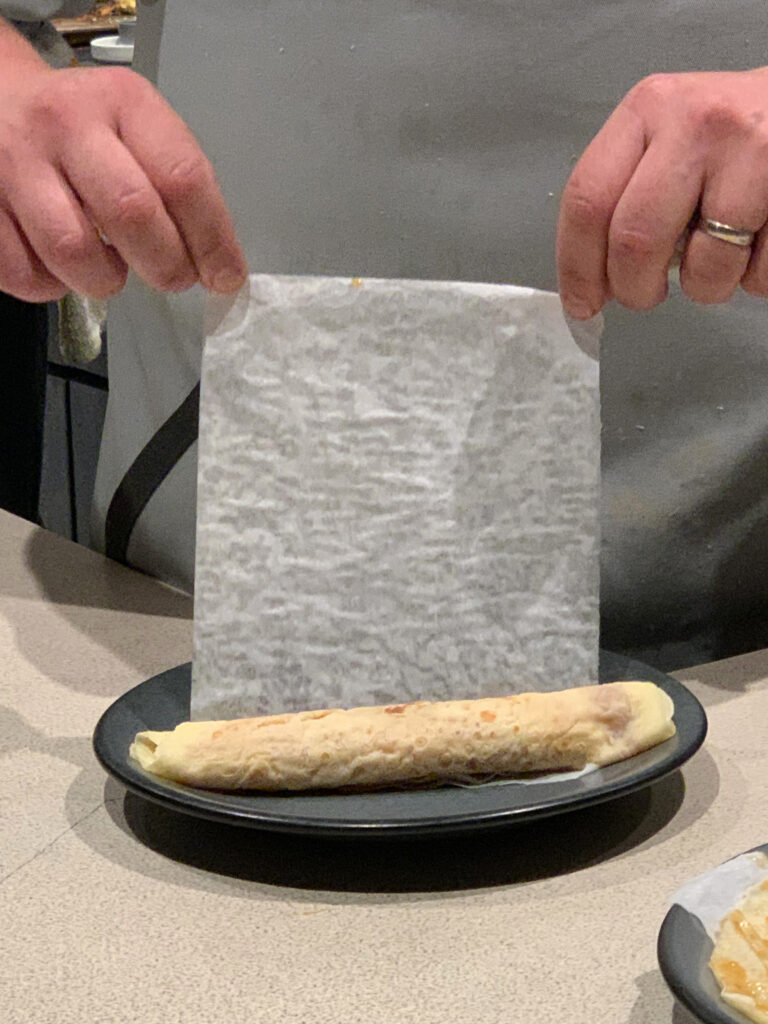

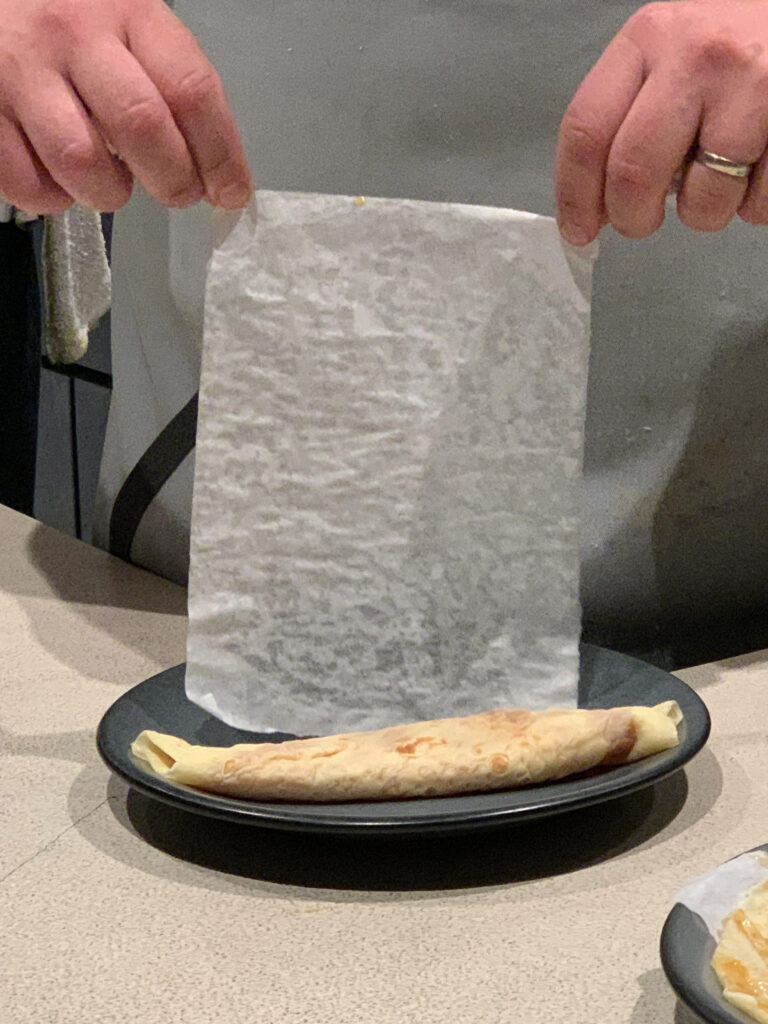

With six savory courses (and a few extra bites) under your belt, the Chef’s Counter experience turns towards dessert. During your first meal, that comprised a “Palačinke,” or crêpe-like pancake common to a wide range of Slavic cuisines. However, the recipe can actually be dated to both ancient Greece (circa 350 BC) and ancient Rome (circa 160 BC), where it was known as a “placenta cake” (and consisted of “many dough layers interspersed with a mixture of cheese and honey and flavored with bay leaves, baked, and then covered in [more] honey.”) Few dishes can claim such a rich heritage—not to mention one that binds such a breadth Central and Eastern European cooking traditions together.

For his version of “Palačinke,” Flamm starts with a half dozen crêpes that have been freshly made, just on the other side of the counter, by his pastry chef. Each of the thin pancakes rests on a layer of parchment paper, which, in turn, rests on top of an individual plate. Flamm spreads a coating of caramel across the interior of the crêpe then, grasping the paper, rolls it into a tight cylinder. Finally, the dessert is crowned with a scoop of pistachio gelato and given a topping of the same (ground) nut.

While decidedly simple, the “Palačinke” comes together beautifully. Rolling the crêpe serves to warm the caramel and form the multilayered texture the recipe is known for. The pistachio gelato has been on Rose Mary’s menu since the beginning; however, you have long thought it to be the restaurant’s best flavor. It balances its subtle sweetness with a pronounced nuttiness while forming a beautiful temperature contrast with the pockets of buttery dough and caramel. The bits of ground pistachio, meanwhile, underscore the gelato’s flavor and provide an essential crunch to contrast the preparation’s smooth, rich mouthfeel. Relative to the restaurant’s usual dessert selection (that, while having improved, has still underperformed relative to the savory fare), the “Palačinke” is a winner. The dish embodies the simple elegance that characterizes so many of the chef’s best creations, and seeing him make it before your eyes forms the cherry on top.

The dessert served as part of your second tasting menu lacked the same sense of heritage or presentational flourish as the “Palačinke.” However, it was hedonistic to the extreme. The dish comprised a “Galette” of blueberry and apple topped with vanilla gelato—that’s it. While Croatian culinary tradition does indeed feature sweet and savory cheese galettes known as prisnac, they are typically baked in the bell-shaped peka pan referenced in Rose Mary’s longstanding “Baby Octopus ‘Peka Style’” dish. Flamm’s galette, instead, seems influenced by the free-form fruit pie (or crostata) recipes that are found in French and Italian cooking.

Watching the pastry chef collect the whole galette from the oven and walk it—with its shimmering blueberry topping—past the counter stops you dead in your tracks. As the pie gets put down and portioned onto six plates, you breathe a sigh of relief knowing without any doubt for whom it is destined. Yet, by the time the vanilla gelato is scooped and placed right between the crust and the filling, you can barely take the anticipation anymore.

Upon finally attacking the dish, you are impressed by the crisp, flaky character of the galette’s crust. It breaks apart cleanly, allowing you to separate a cohesive bite containing a bottom layer of apple and a top layer of blueberry. Texturally, this structure ensures that the larger components (the crust and the apple) cushion the smaller one (the blueberries). When the vanilla gelato or crimped end segment of crust strike from above, they effectively seal the galette with an added top layer that is smooth and/or crisp. In terms of flavor, the combination of baked fruit, buttery dough, and cooling vanilla is as classic as can be. But, here, they are executed to a T, spurring powerful feelings of nostalgia. Though something of a thematic curveball, the “Galette” was immensely satisfying at both an emotional and gustatory level.

The last dessert you sampled, as part of your third Chef’s Counter experience, was perhaps the most technical. It comprised a “Gianduja Tart” topped with preserved cherries, pastry cream, and a bit of Italian parsley. While, at face value, there once more seemed to be little thematic connection to Croatia, gianduja’s 30% proportion of hazelnut paste may reference the fact that the country provides Italy with thousands of tons of the product (at a “first-class” quality level). Not to mention, the infamous neon maraschinos took their original inspiration from the prized marasca cherries used to make liqueurs in Dalmatia.

Each guest receives one of the small tarts, which displays a smooth shell with only a small bit of cracking at its base. The chocolate filling sits flush against the crust, making for a smooth canvas on which the cherries, pastry cream, and herbs sit. The tart breaks cleanly when attacked with your fork. The resulting bite is crisp, crumbly, and luscious with a finishing burst of fruit and a snappy touch of stem. The flavors smack of butter, roasted nuts, medium-bitter chocolate, and stewed dark cherry with a clean, peppery finish. Overall, this a nicely balanced, crowd-pleasing dessert that may lack a bit of distinction—but still draws the meal to a nice close.

With that, the tasting menu draws to a close, but the Chef’s Counter experience is not yet over. To gild the lily—especially when the assembled guests are celebrating a special occasion—Flamm asks the crowd to name their favorite spirit. (Personally, you enjoy imbibing Rose Mary’s bottle of Żubrówka—a Polish vodka flavored with bison grass said to take on the appley character of the animal’s urine). The chef returns bearing a tray of shot glasses and shares a toast with the party.

Menus are handed out, which Flamm is more than happy to sign. And you’re sure the Top Chef wouldn’t mind posing for a picture at this time either (though that is not the kind of keepsake you indulge in). Once the check is paid, the evening winds down rather naturally. You are not rushed, nor do you get any sense that another seating is imminent (even though there is often little more than a fifteen-minute gap between the parties). Rather, like a guest in someone’s home, you can sense when your host has given his all and has earned some respite.

You leave your spot at the counter and retrace your steps through a restaurant that—at just past 8 PM on a Friday or Saturday—buckles with energy. As you walk through the sea of other diners, those who are enthused just to have a table, you treasure the intimate connection you shared. The chef that everyone has come to see, the kind of larger-than-life figure that is unavoidably warped by the power of TV stardom, has cared for you as if you were kin. He bids one last farewell as you step back out onto Fulton, where Rose Mary stands as an oasis of genuine hospitality in a neighborhood that is slowly becoming a cynical, commercial wasteland.

Looking back across three Chef’s Counter tasting menus you can count shining instances of creativity (“Tartare,” “Risotto,” “Ćevapi Stuffed Squid”), finesse (“Charred Beet Carpaccio,” “Pappardelle,” “Prosciutto Risotto,” “Quail”), and pure deliciousness (“Semolina Dumpling,” “Gemelli,” “Milk Braised Pork Shoulder,” “Braised Lamb”). Of those dishes that remain, “Prawn” was enjoyably bold (but polarizing) and the rest—“Scallops,” “Grilled Peach,” “Goat Cheese Agnolotti,” “Lamb Risotto,” and the two branzino preparations—were good but perhaps not as memorable. (It is interesting to note that all but one of these relatively “weaker” preparations were served during your first menu, indicating just how much the offerings have grown over time). The desserts, likewise, ranged from good (“Gianduja Tart”) to great (“Palačinke”) to stunning (“Galette”) without ever losing sight of the pure enjoyment (see: the peak-end rule) they should aspire to.

Nonetheless, coldly analyzing the food only tells part of the story. It misses the dynamism involved in crafting a totally new menu every weekend, and the natural showmanship that accents each and every preparation served at the counter. It discounts the storytelling, the shared laughter, and the “inside-baseball” insights that enrich those moments you do not spend eating. It denies the fact that Flamm is really there, from beginning to end, conducting his kitchen but, principally, devoting his time and attention to you.

Just what dining experiences in Chicago—outside the realm of omakase—can promise such a degree of interaction with their master craftsman? Grant Achatz, Noah Sandoval, and John Shields may spend a moment at your table. Curtis Duffy will say hello to you inside his kitchen. But, as thrilling as these encounters are to those who bow before the altar of celebrity chefdom, they preclude the kind of life-affirming connections that endear you to the humble neighborhood haunts that could never be mistaken for “fine dining.”

While Flamm, from the perspective of a typical Rose Mary diner, offers up the same fleeting memories as he tours the dining room, his Chef’s Counter forms the anchor for a richer expression of the chef’s personality. Through this menu, he does not only put himself out there—more than half the battle in a city where even Michelin-starred craftsmen have a bad habit of cloistering themselves completely. But he offers a genuine, unscripted expression of self that surpasses anything seen in the implicitly intimate realm of Chicago omakase save for enfant terrible Otto Phan.

Flamm, of course, maintains a natural charm and that reflects his Midwestern roots. There is a poise and ebullience to the way he works that assures you there is nowhere—other than among his wife and children—he would rather be. (You have not, admittedly, watched a second of Flamm’s Top Chef-winningseason, but you bet he more than meets every expectation that fans of show might bring to the table too).

Thus, in an era of increasingly contrived, larger-than-life food media muppets, Rose Mary’s chef offers something true. He fulfills the fantasy—so often imagined when purchasing tickets but so rarely fulfilled in the restaurant itself—of the chef-craftsman who feeds the body and the soul. He joins just a handful of other culinary figures throughout the city—at Goosefoot, Hermosa, Kumiko, and other aforementioned establishments—who can be counted on to really give themselves to you when you pay them a visit. And Flamm’s cuisine—capturing every bit of the refinement of his Spiaggia days—pleases with an even greater impact on account of the emotional connection that forms.

The Chef’s Counter at Rose Mary is one of Chicago’s finest examples of “new luxury.” The experience remains accessible for fine dining neophytes while offering the kind of depth—like an ever-changing seasonal menu and well-curated wine list—to please certified snobs. Sitting in a busy restaurant’s very best seats does, indeed, add to the enjoyment. But it is Flamm, from beginning to end, who cements the feeling that you are celebrating a totally singular meal. Not in a way that touts “exclusivity”—the secluded kitchen table that allows you to sneer at the poor slobs seated next door—but reveals how superfluous many of fine dining’s favorite niceties really are.

In truth, a superlative meal demands nothing more than eager diners and a willing chef. The more those two parties see eye to eye—the more they interact—the less evening centers on mere food. The need to eat might make the moment, but human connection transcends such a base desire. Hospitality, in its most glorious sense, reigns and satisfies a much deeper need: to feel a sense of belonging with each other and with nature itself.

You have already expressed that Rose Mary’s Chef’s Counter feels like eating in the chef’s home. (Or maybe even your own home—something well-heeled gastronomes pay Flamm quite a pretty penny for). There is really no greater compliment you can give, for it strikes right at the heart of what your rating system prizes. Flamm, in this inaugural year, has already shaped one of Chicago’s most memorable dining experiences. And, when the city’s $200+ tasting menus do nothing to guarantee chef interaction, his Chef’s Counter positively turns other restaurants’ value propositions on their head. You hope more diners, from near or far, can see what you mean—next year, at least!