After enduring six meals at Feld during its first two months of operation (along with a trailing, seventh visit in September of 2024), I needed a break.

During that time, I witnessed the restaurant transform from detestable (in those first couple weeks) to respectable (by the time it reached the eight-week mark that is customarily considered fair game for professional criticism). I observed how the toxic narrative surrounding the concept—shaped by the worst of the kitchen’s work and fueled by the defensiveness of its chef—survived long after the team had actually righted the ship.

Feld had been flattened, memeified, and more or less dehumanized by “the crowd.” It was scapegoated, well beyond Chicago or any target demographic, as the representation of everything everyone hates about fine dining and (more specifically) a class of aspirant, “nepo baby” chefs said to have not adequately paid their dues.

Certainly, many of chef Jake Potashnick’s wounds were self-inflicted. He even took aim at me personally in the leadup to Feld’s opening. However, in practice, Potashnick was always a consummate host, and his commitment to process and a particular philosophy (whatever one thinks of the “relationship to table” moniker) was real. The esprit de corps he had built at the restaurant, even during those early days, was just as genuine.

Within two months, Feld had established the kind of foundation (with regard to signature recipes, seasoning, and the basic flow of the meal) that it maybe should have had from the start. Yet, better late than never, the concept was finally poised to prove the merits of an ever-changing, hyperseasonal menu. At last, it cleared the bar of competence and could actually begin to impress Chicagoans with how intimate and mind-expanding its cuisine was.

I left Feld as a fan: not just of Potashnick’s own personal redemption but of what the restaurant, over the long haul, would do to drag our dining scene into the future. The chef’s chosen style (kindred with the experimentation shown at places like Cellar Door Provisions and Smyth) was presented so effectively and approachably that he naturally formed the vanguard of a movement to appreciate ingredient sourcing—as well as the more challenging, intellectual side of that process—more than sheer deliciousness at every turn. Potashnick would open the door for a generation of chefs to take bigger risks, in pursuit of novel ideas, rather than playing it safe in an effort to suit the caprices of the market.

Ultimately, I was a believer, but the restaurant would have to get there on its own. My loyalties would remain with the places I already frequented, and my attention would be devoted to a new set of openings. In the meantime (and for my own personal calculus), liking Feld became a barometer for who was really thinking and tasting for themselves in the dining scene.

I finally returned to Feld a year later—in September of 2025—with a couple of skeptics in tow. Across more than two dozen dishes, they honed in on a couple glaring flaws while I, in turn, appreciated just how big a few of the hits were. The menu wasn’t drastically better than those I encountered around the two-month mark, yet the team was certainly moving in the right direction by continuing to experiment, refine their work, and fulfill the potential that such a process (iterated countless times) inevitably carries.

A television appearance and a boatload of awards would shortly follow—with Bibendum’s honors (as impenetrable as the Guide’s thinking can sometimes be) feeling well-deserved given the fortitude and forward-thinking on display.

Suddenly, reservations at Feld became highly coveted, and that’s where I reenter the picture: evaluating a concept that has (by some measure) come of age while exploring what others, unburdened by those early growing pains, now see.

Let us begin.

It’s Saturday night—the only night that Feld (having scaled back its seatings a while ago) conducts two services—and I am a few minutes early for my reservation. Approaching the restaurant’s front door, I find that it swings open in anticipation of my arrival. Just inside, a guard of honor awaits: offering the warmest of welcomes.

Potashnick leads this effort alongside general manager/sommelier Nathan Ducker, and it’s hard to think of any other fine dining concept that is as direct or deferential in how it wields its headlining talent. Even at Chicago’s finest omakases, there’s usually at least one layer of hospitality (e.g., a door, a host stand, a bonafide lounge) separating guests from the man behind the counter. And, at those temples touting two or three Michelin stars, one is regularly left questioning when (let alone if) the starring chef will make an appearance.

Potashnick, whether one subscribes to the narrative that dogged his debut or comes here with an open mind, humbly puts himself at diners’ disposal from the first moment of interaction. There’s not a whiff of ego about the gesture either. The chef-owner, in dress and demeanor, gives the impression that he’s working alongside peers. He leads by example at a time (every night) when he could be worrying about something in the kitchen. He strikes an emotional chord that only grows in force during the course of the meal.

For me, it’s nice to share a friendly greeting and my congratulations in the wake of Feld’s Michelin star. Potashnick has never been anything but magnanimous following his critical redemption, and I get the sense that all the awards (which are really flowing now) have empowered him to dive even more deeply into his work. Yes, armed with the affirmation that diners near and far appreciate what the restaurant is all about, the chef can certainly dream of what the next years (or maybe even decades) have in store. The boundaries of “relationship to table” may be hard to pin down, but, at the very least, it implies some degree of perpetual growth.

Upon being led the short distance to my table, I take a moment to scan the dining room. Punctuality aside, all the other parties (save for one) have already been seated. They form a serious crowd: the white, middle-aged, well-dressed cadre that one frequently finds chasing the hottest new openings. Feld is not that, but it has come of age. The guests here are pleasant, wholly engaged, and clearly eager to get a taste of what the kitchen has in store.

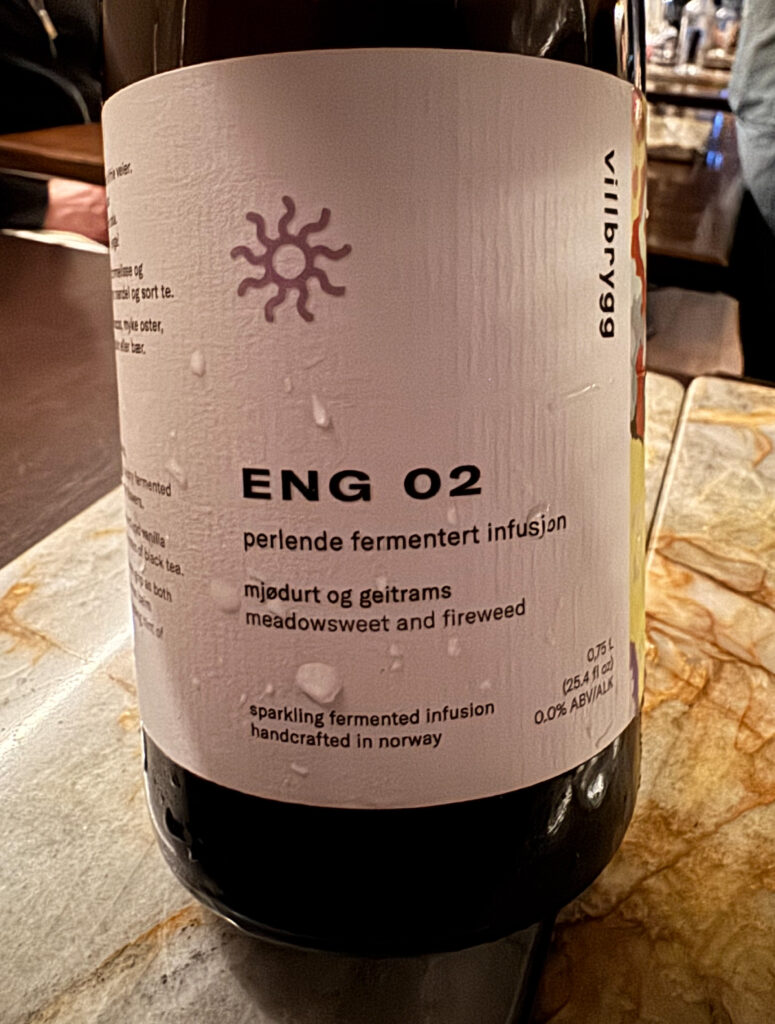

Tonight, I note that quite a few customers have opted for the “Low ABV Pairing” ($110), which comprises a sparkling juice, a kombucha, fermented infusions, non-alcoholic wine, and non-alcoholic sake. Despite the reliance on readymade products, the selection is fairly unique and enjoyable for the price. In terms of quality, I place the pairing just behind Smyth’s—whose sourcing is a bit better (though they eventually aim to produce 40% of offerings in-house)—and well ahead of Oriole’s—which, no longer featuring the work of Julia Momosé, has so far struggled to craft its own appealing brews.

Ducker’s enthusiasm and wealth of knowledge—raising these products to the same heights as actual wine—does much to gild the lily. Despite bearing so much responsibility at the restaurant, the sommelier performs passionately for his audience. The rest of the team, when stepping in to fill a glass, might struggle to match the same energy; however, tasked with delivering the requisite information, they hit all their marks. Considering the level of detail demanded when presenting the food (not to mention the duties of preparing and plating the menu that many here juggle), I think everyone operates at a fairly high level.

Technical demands of the job aside, the team does a brilliant job of extending the feeling of warmth and intimacy one feels from the moment of entry. That could mean riffing off of a joke told by one of the guests at the table or, more intentionally, seizing on a lapse in conversation to ask someone’s thoughts or (for repeat visitors) catch up. I was particularly impressed when one of the new employees made a point to introduce themself and establish a baseline of familiarity. Such a gesture drove home the sense that this is a tight-knit crew—yet one, in turn, that looks to welcome patrons into the same kind of connection they share.

The key element here is a certain effortlessness and naturalness to interaction. One never catches any trace of a script or a playbook that has been contrived to please the majority of tables. The team’s tendency, rather, is to put forth a legitimate piece of themselves, sense what patrons are giving back, and, when possible, build a rapport that transcends the division between server and served. Of course, this process demands a bit of vulnerability, which, in turn, speaks to how well the staff itself is treated.

Indeed, when one observes Potashnick’s own propensity to linger and regale his customers on any number of topics, it becomes clear that this admirable, inimitable culture flows down from the top. When one hears the chef, stationed at the pass, greet each and every guest when they return from the bathroom, it is also apparent how countless small courtesies—and an ironclad sense of focus—underlie the more distinctive, memorable examples of service. For that reason, even when things go wrong (such as spilling a carafe of water), the mood in the room remains playful and calm.

Ultimately, hospitality has formed one of Feld’s strengths from the very start. However, now that the restaurant has found its footing, gained in confidence, and grown around a core of people who have been there since opening, the service experience really does feel superlative. They may not be slick or suited, but the team here is strikingly sincere. They make diners feel comfortable and cared for in a manner I can only compare to Chicago’s finest establishments.

Thematically, tonight’s meal is distinguished by Feld’s emergent relationship with a California citrus farm that, the chef notes, is really helping the team get through the winter by providing fresh produce that aligns with the “relationship to table” ethos. Potashnick also excitedly shares that the restaurant is utilizing some of their fruit preserves for the very first time (a cycle of conservation that, if managed correctly, will ensure the restaurant is never short on ingredients that accord with its philosophy).

On a more personal note, I’m pleased to see a familiar face now working behind the stove after a three-year stint at Smyth. Certainly, the flow of talent from one concept to another is a fact of life. However, I really cannot think of a better place—fueled by collaboration and so ceaseless in its recipe development—for someone of this experience and talent to land. It’s a great testament to the kind of opportunity Potashnick has created for his fellow cooks, and the move also allows for a synergy of two culinary styles that I have always felt to be kindred.

Shortly after guests are seated, a simple cup of “Mushroom Tea” arrives. Think of it like Oriole’s own tea (or Smyth’s amazake): an opening flavor impression that may also help you warm up from the cold. While it’s easy to imagine this kind of earthy broth going wrong, each sip is beautifully salted and replete with savory depth. Yes, as the mushroom imparts its long, pleasing finish, one is left with no doubt that Feld has dialed in its seasoning.

The menu properly kicks off with what the team terms “The Drop”—some 11 different bites, delivered in a flurry then enjoyed as one pleases, celebrating the ingredients of the moment (as well as a few that are stalwarts here). Nine visits in, I am still left awestruck by what seems like a never-ending flow of comestibles. These are not trifles either: I’m talking fully composed ideas or, alternatively, products that can only be formed through care and patience.

The only point of comparison I can draw is to SingleThread (where a similar arrangement of awaits you upon arrival at the table) or Blue Hill at Stone Barns (where a snapshot of the farm’s bounty is served in quick succession). In short, there’s nothing like this being done elsewhere in Chicago, and the emotional effect of this presentation alone is almost enough to justify the ticket price. Of course, much depends on how the items actually taste.

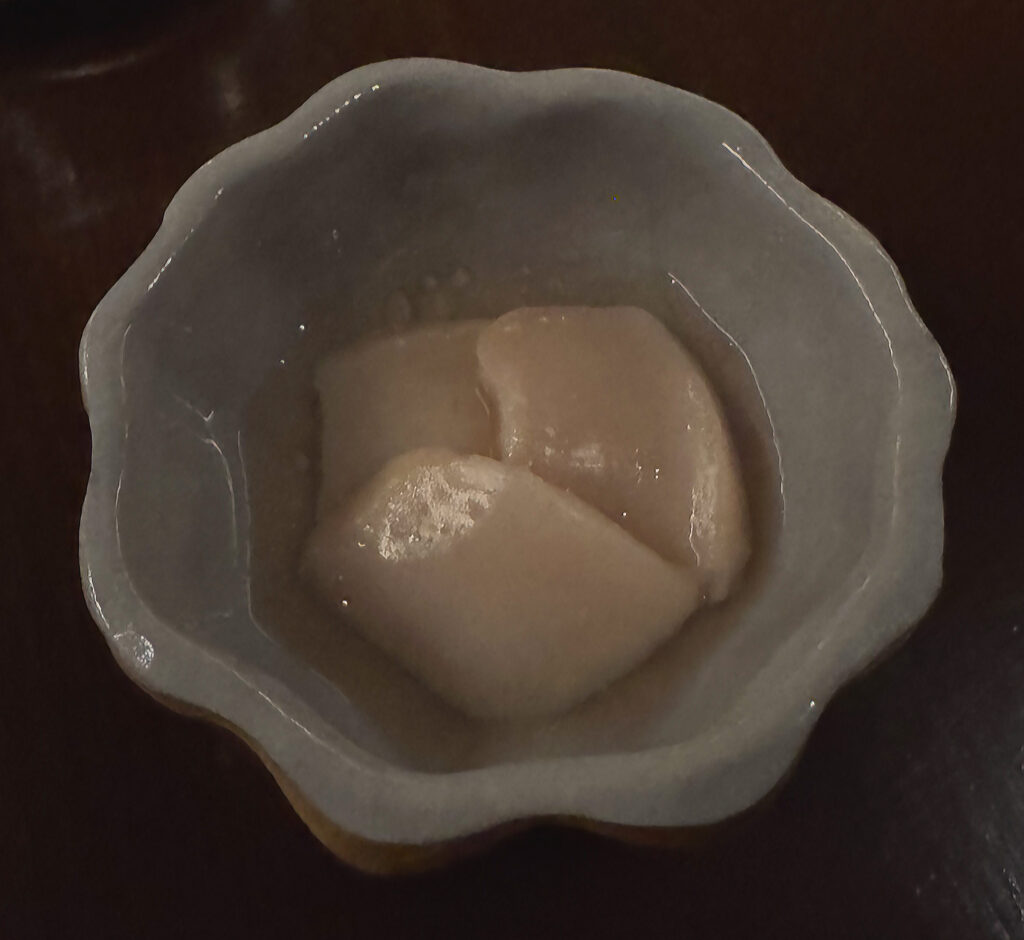

A serving of “Cured Scallop” (that is, cured using Benton’s ham) is paired with green pear vinaigrette and horseradish oil. On the palate, it combines a beautifully soft mouthfeel with uplifting tang, attractive sweetness, and just enough salt. This makes for one of the highlights of the sequence.

The “Preserved Strawberry” (topped with a dollop of something I failed to record) is also delicious: striking the tongue with a concentration of sugar and supporting acid that feels as though the fruit has been supercharged. Served at this point in the year (and opposite so much meat and seafood), this is a real treat.

Situated alongside the preceding bite, a “Lobster Tail Pancake” combines the plump chew of the crustacean with its subtly crisp, yeasted vessel. There, too, is a pleasing sweetness to the sensation here—one that is complicated by a kind of sourdough note. However, while good, this pancake just lacks the intensity and (expected) decadence to really be memorable.

A “Lobster Knuckle Salad,” served in a crusty vessel (kind of like a fluffier pie tee), is simultaneously crunchier and more soft, moist, and melty than its compatriot. The flavor here also shows some enjoyable heat on the finish. Nonetheless, it ranks at about the same level: tasty but not quite memorable.

The “Tempura Acorn Squash,” dusted in preserved fig leaf powder, reminds me of just how far Feld has come. Formerly, the restaurant served its fried delights without any paper to soak up the oil, and that led to a soggy mess. Tonight, I find the texture to be competently executed (combining a fleeting crunch and a firm, crisp interior), yet, when it comes to flavor, the tempura could use a touch more salt. Also, admittedly, I likely made a mistake by not consuming this bite sooner (so, perhaps, the team should consider labeling this one as time sensitive).

The ”Nasturtium & Quail Egg” centers on a soft-boiled, “deviled” preparation of the latter ingredient that has been brushed with ham fat and filled with an filled with an emulsification made form the titular herb. The resulting mouthful is plump and rich but marked by a strange greenness on the finish. Still, there’s enjoyment to be had.

Turning toward the penultimate plate, one finds a “Duck Leg Terrine” that is rendered as the filling of a savory pie topped with a gelatinous orange and chili glaze. On the palate, the pastry is appropriately crumbly; however, the components ultimately feel dry when they come together. Flavor, in turn, skews jarringly toward the acid of the citrus and, thus, robs the preparation of its savory power. The end result is a little disappointing, but I appreciate the core idea here and just think the recipe needs to be rebalanced.

A slice of “Duck Prosciutto,” thankfully, proves more successful. The meat here is cured in-house and comes topped with a charred leek salt. It possesses a clean, smooth consistency (complete with melty cap of fat) and accompanying smoky, sweet, and savory flavor. In sum, this is nice.

The “Parsnip Tart” also stands among the most appealing items: combining a potato base filled with a parsnip/squash cream and topped with a slice of confited parsnip. Whereas the earlier duck pie was plodding in its execution, the present example juxtaposes a delicate, brittle exterior with a soothing, effectively moistening interior. The resulting sensation—marrying sweetness, brightness, and a tinge of earthy, nutty complexity—is quite impressive for an oft-overlooked root vegetable.

On the final plate, one finds a curl of “18-Month Benton’s Ham” that, while totemic to the restaurant, flounders in comparison to the housemade duck prosciutto. Yes, while this is a product I typically enjoy, the meat tonight is marked by an abrasive bitter note that detracts from its usual fatty, salty expression. Ultimately, it’s hard to know whether this flaw comes from a problem with production or (perhaps more likely) with storage. However, the bitterness results in a bite to forget on this occasion.

Last of all, one finds the “Foie Panisse”—a chickpea flour fry that is cooked in foie gras fat and finished (on one end) with a dab of allium. Though simple enough, this offering is executed to perfection: delivering a satisfying crunch, a perfect dose of salt, and a surprisingly savory finish. I probably (like the tempura) should have eaten this one earlier, yet its consistency held up nicely all things considered.

Taken as a whole, this iteration of “The Drop” ranks as the best I have yet encountered at Feld. Indeed, while there were two or three weaker items, they remained wholly approachable (and maybe even mildly enjoyable). Moreover, the majority of bites were clearly good, and another two or three reached the level of being great.

Considering the dynamism shown within this section of the menu, I think this hit-rate is admirable. One could still argue it would be better to serve fewer, better offerings at the end of the day, but I would also contend that the overflowing generosity of this course is such a big part of the fun. It’s also not hard to imagine the kitchen raising the baseline quality of the various components even higher over time.

With the arrival of individual dishes, the meal starts to feel more serious. Of these, “Citrus—Fig Leaf” leads the charge: combining chunks of mandarin and pomelo with a drizzle of fig leaf oil and a crowning granita made from beetroot, horseradish, and housemade koji.

On the palate, the fruit feels beautifully plump and juicy. They meld well with the ice, which feels particularly smooth, and take on an almost creamy finish with the incorporation of the oil. The resulting flavor here is expectedly tart and sweet with tropical undertones from the fig leaf. However, what really impresses me is how well these notes harmonize with the sharper, savory character found in the granita—a punch-counterpunch feeling that leaves me licking my lips in pleasure. Overall, this makes for a bright, invigorating transition from the parade of bites into the heart of Feld’s creative expression.

Next comes a preparation titled “Golden Beets—Rosemary,” which centers on whole pieces of the starring root vegetable that have been steamed, peeled, grilled, and then thinly sliced. The resulting segments come dressed with a gelée made from the juice of grilled Cara Cara and Navel oranges and a blackcurrant balsamic (which, though unstated, I assume has been infused with the titular herb).

Texturally, this dish does a nice job of juxtaposing the crisp slices of beet with the soft, creamy gelée. I also appreciate the fact that the root vegetable (often maligned for its earthiness) tastes so clean. That said, the flavor expression here is totally dominated by acid and a pithy bitterness. There’s absolutely no sweetness at hand (from either the beets or the oranges), and I am left wondering why the balsamic feels so muted as well. Ultimately, it’s easy to imagine how this combination might work. Execution simply needs to be improved.

Thankfully, the “Winter Spinach—Goat’s Butter” that arrives next represents an immediate turnaround. Beyond that, there’s really little to add in terms of detail when it comes to the recipe. The spinach here has been over-wintered and simply thrown on the grill. The goat’s butter, in turn, is used to make a classic beurre blanc. This yields mouthfuls that are crunchy, creamy, and building in their sweetness. The overall effect is so satisfying, and this dish epitomizes the kind of minimalist (but memorably pleasing) vegetable cookery Feld is perfectly positioned to present given its format.

A course titled “Gilfeather Rutabega—Chestnut” continues this trend. The heirloom variety named here (technically a cross between the titular vegetable and a turnip) dates back to the early 19th century. Here, it comes butter roasted and portioned into four small slices. They come served in a broth made from dashi, Benton’s bacon, toasted rice, and the starring chestnut: lending roasted, earthy, and savory depth to an otherwise sweet, subtly crunchy expression of rutabaga. The combined sensation is deeply comforting, and I am again left charmed by the kitchen’s way of elevating overlooked produce.

The ”Grilled Scallop—Smoked Garlic” helps to break up the flow of spinach and rutabaga with a preparation of shellfish that is more unabashedly decadent. Cleverly, the bivalve is only cooked (over cherrywood) on one side: making for a natural textural and thermal contrast. It is then paired with almond butter, a Savagnin-infused beurre monté, a black garlic vinaigrette, and what the team terms a “Magna Carta” (that is, a mussel-inflected bagna càuda).

On the palate, the scallop elegantly blends crispness and firmness with a gooier, gummier consistency I’ve come to love from hotate sashimi. While the starring ingredient is intelligently salted, it is the arsenal of nutty and umami ingredients I am most interested in. On paper, this rogue’s gallery seems like it could be too redundant, too much, and (thus) too mouth-aching in its intensity. However, once these creamy layers combine, they impart a supremely savory, caramelized sensation that—cut with just the right amount of acidity—never feels ham-fisted. Indeed, the sum effect is almost reminiscent of Maggi (which was favored by Escoffier after all), but I think that goes to show just how fully and convincingly Potashnick (for all his work with lighter fare) can conjure a profound feeling of satisfaction when he so chooses.

When the “Smoked Celeriac—Pleasant Ridge” arrives, I prepare for a sudden downturn in quality. After all, how’s a serving of celery root ever going to keep pace with an umami-laden scallop? But Feld has worked with Uplands Cheese from the very beginning (remember the tasting of three consecutive days’ milk?), and the team knows just how to weave magic using its products. On this occasion, the Pleasant Ridge Reserve is grated over celeriac that has been smoked, dressed with a celeriac cream, and finished with a bit of duck fat emulsion.

Paired with the crisp (yet ultimately tender) piece of root vegetable, the cheese draws out—and expands upon—the ingredient’s latent nuttiness: striking with a burst of salt and caramelized undertones that imbue this rich, creamy recipe with tremendous depth and balance. Yes, it’s hard to believe the kitchen has upped the ante on what was already an excellent, decadent preceding dish. This ranks as one of the highlights of the evening.

So, too, does the “Turnip Velouté—Apple”—a time-sensitive creation that, on the surface, looks and sounds like it should be served with dessert. The preparation centers on a quenelle of cold apple sorbet that, along with slivers of the caramelized fruit and an oat crumble, sits within a warm sauce flavored with the titular turnip and cauliflower.

On the palate, the temperature contrast here is expectedly striking and, I’d go so far as to say, even soothing. There’s plenty of sweetness at hand—pure notes of apple, its more concentrated, buttery counterpart, and a nostalgic toastiness tying it all together—but what’s really exceptional is how well the vegetables are integrated. The velouté possesses just enough sweetness not to clash with the fruit, as well as just enough nuttiness to harmonize with the oats. The sauce’s richness provides staying power, which enables the turnip-cauliflower combination to assert its earthier, peppery character and steer the recipe back towards the savory side. Overall, I’d still say this course feels like a dessert, but it’s beautifully composed and does a phenomenal job of reinvigorating the palate after a couple luxurious bites.

Approaching the savory peak of the menu, I am met by a course titled “Butternut Squash—Chestnut” that echoes a few of the ingredients featured during “The Drop.” Here, the starring gourd (rendered as a roasted chunk) is joined by a whole lobster claw (the only section I wasn’t served earlier) dressed with lobster bisque and lobster butter. An onion jus, a chestnut purée, and some crispy chestnut complete the presentation, which again seems to be swinging for the fences of decadence.

On the palate, the delicacy of the crustacean’s claw blends effortlessly with the smooth, creamy butternut squash. The resulting flavor is a little sweet and a little nutty but just seems to lack the kind of fireworks that so many kindred ingredients, concentrated into complementary forms, would hope to offer. To be clear, the dish wholly enjoyable. It just lacks that cohesiveness and intensity to really deliver something more than the sum of its parts.

At this point in the meal, Potashnick goes from table to table with a carcass in tow: one of only 380 ducks that Au Bon Canard (operating out of Minnesota) raises each year. As I salivate at the sight of the bird’s crisp, mahogany-toned skin, the chef-owner describes how the ingredient will feature across the next two courses. He also proudly shares that the farmers themselves are dining at the restaurant tonight during its second seating.

Au Bon Canard is known principally for its production of liver (which, indeed, has featured on Feld’s menu before), and that is what arrives first. The “ABC Foie Gras—Sunchoke—Apricot” sees the starring offal cooked, en papillote,over coals. The resulting portion is then paired with a brown butter purée, crispy chunks of sunchoke, and a triple expression of apricot (pickle, jam, and vinegar).

On the palate, the duck liver itself is expectedly rich and creamy with only a trace of intervening sinew. The sunchokes, in turn, provide a hearty contrast. However, while the root vegetable forms the only component on the plate that is actually hot. The remainder land more on the lukewarm side: a divergence that is not disqualifying but, likewise, probably makes the mouthfeel of foie gras more challenging for most people. I expect the apricot, with its concentration of sweetness and tartness, to cut through all the decadence and carry this recipe. The fruit, in its myriad forms, is not unpleasant, yet its acidity (due to the pickles and vinegar overshadowing the jam) feels disjointed. As a consequence, the overall dish just fails to click. I’d like to see the kitchen take another crack at balancing it though.

The “34-Day Au Bon Canard Muscovy Duck” that arrives next is undoubtedly the main event: one that not only showcases a relatively precious product but that represents a rare departure from the aged pork preparations the restaurant has long favored. Visually, the meat marries its attractive, craggy exterior (noted earlier) with a subcutaneous layer of rendered fat and a pinkish (almost tending toward red) base of blushing flesh. Finished with a sprinkle of salt, the sizable portion is paired with a sourdough rye jus as well as reductions of pomegranate and passion fruit.

Texturally, the bird itself—boasting cleanly crisp skin, melty fat, a subtle (pleasing) chew, and pronounced juiciness—is beautifully rendered. The application of salt, too, is nicely judged so that even bites lacking much of the accompanying sauce yield an enjoyable, savory flavor. Should one incorporate the jus or supporting elements of fruit, the resulting sensation delivers harmonizing tang and sweetness. Ultimately, the recipe deserves credit for its utter simplicity and confidence in the kitchen’s ability to cook the duck. Personally, I’d like to see the crispness of the skin taken to an even higher extreme and for the chosen dressings to do more to reinforce the meat’s own essence. Nonetheless, this stands as a skillfully executed dish that ranks favorably compared to the city’s other headlining presentations of duck.

The turn toward dessert strikes a familiar note, and it does so in a twofold manner. “Rush Creek Reserve,” as the item is titled, references another—particularly fleeting—product from Uplands Cheese (one of Feld’s emblematic collaborators). Potashnick works with this once-a-year release whenever it comes to market, and, here, the pasty, spruce-wrapped variety serves, along with some caramelized apple, as the filling of a savory donut. However, when I see the glaze (termed a blackcurrant-duck fat fudge), only one restaurant comes to mind. This second sense of familiarity is only driven home when the ex-Smyth cook jokes, “does it look familiar?”

Now, as far as I’m concerned, there’s enough room in Chicago for every fine dining restaurant to serve some kind of donut. Further, if I think of the renditions John Shields is now serving (stacked high with eel or trout belly), they hardly resemble what I see here (something more reminiscent, at least visually, of what Smyth served a couple years ago). On the palate, Feld’s donut is crisp and hot but lacks a little of the creamy, oozing consistency I’d like to feel from its filling. The flavor, likewise, skews more toward the mild, savory side rather than melding richness and sweetness in a way that really bridges the gap between these sections of the meal. That said, I think the dish is packaged with a fair amount of skill, and, expanding on this foundation, the kitchen should be capable of crafting something special in time.

Arriving next, the restaurant’s play on a “Carrot Cake” promises all of the indulgence the preceding pastry failed to deliver. Indeed, upon hearing the dish’s constituents, there’s nothing all that weird to get worried about. You have a carrot-pecan cake, a quenelle of malted barley ice cream, a drizzle of fig leaf oil and a sauce made from white chocolate, crème anglaise, orange, and brown butter.

Texturally, the crumb of the starring element is remarkably moist and smooth. It grows richer and softer as it soaks up the accompanying liquid (including the well-tempered ice cream), revealing a flavor that spans deep, earthy, toasty, and roasted root vegetable notes before settling on a nutty, fruit-kissed concentration of sweetness that displays shocking length. Yes, the ingredients here achieve total cohesiveness and deliver a degree of pleasure that stands, perhaps, as the kitchen’s biggest hit of the night.

For what it’s worth, the “Sweet Potato—Pecan” comes quite close in its own right. This recipe centers on a cream made from the titular tuber (a Japanese variety) in concert with almond milk, meringue, and a praline made from the starring nut. Texturally, this dish juxtaposes smooth and brittle sensations in a fairly conventional manner. However, the harmony displayed by the earthier sweet potato and more caramelized expression of pecan (with the two ingredients combining to form a supreme note of nuttiness) is flawlessly conceived.

Again, nothing about this preparation is all that strange or adventurous (though the cream, certainly, demonstrates a degree of technical mastery). The bowl merely aims at sheer enjoyment and hits the bullseye—reminding guests how ably the restaurant, for all its experimentation, can reward palates when it chooses to.

Tonight, the “Svenska Kakaobolaget” represents the only real carryover from my inaugural Feld meals in 2024. Of course, the 74% dark chocolate mousse (from a purveyor Potashnick visited while working at Daniel Berlin) is dressed a bit differently on this occasion: trading the rosemary and pecan accents that have featured previously for a touch of lemon leaf oil.

These brighter citrus notes—appended to the frothy dollop of chocolate—help to soften the cocoa’s bitterness and emphasize its deeper, fruitier tones. This makes for a smart, simple presentation with a story: one that only suffers on the back of two incredible desserts. Nonetheless, if one thinks of the lemon leaf oil as providing a cleansing, transitional sensation, the course might actual serve a greater practical purpose.

As the menu reaches its conclusion, Ducker and the team bring forth an assortment of after-dinner drinks that has seemingly doubled in size since I’ve last eaten here. Observing the curiosity of the surrounding diners then witnessing how the staff walks them through the countless options makes for another peak point of hospitality this evening.

Feld’s penultimate offering is the “Fresh Fruit on Ice”—a presentation (however charming) whose actual quality has been murky in the past. On this occasion, the selected cranberries, slices of Korean pear, and apple segments each deliver crisp, freshly sweet sensations that reconnect one’s palate (at this late stage) to simple, natural flavors.

This sets the stage for the very final serving: a “Malört Canelé” that combines classic pastry technique with a touch of local flair. Personally, I find the titular liqueur’s cult status in Chicago to be overplayed and a touch demeaning. Yet I cannot fault the canelé itself, which marries a crisp exterior, an appropriately airy (if not custardy) crumb, and a nice degree of sweetness that benefits from a (wholly approachable) hint of bitter grapefruit depth. Ultimately, this makes for a fun bite with added novelty for anyone visiting the city.

With that, the meal reaches its conclusion. Checks are deposited (with removable 20% service charge “for distribution amongst the entire staff”), guest books are shared for signing, personalized menus are presented, and everyone—even in this cold weather—is invited outside to mingle and enjoy some s’mores.

Despite the looming 8:45 PM seating, there’s plenty of time to chat with the chef. In fact, Feld has served some 28 different dishes (11 of them being the bites that made up “The Drop”) in right around two hours and fifteen minutes. If I count distinct courses (that is, combining items that arrive together), this makes for an average of eight minutes between servings: an absolutely blistering pace that helps to smooth over any of miscues that are bound to inhibit such an experimental cuisine.

Though, to be honest, I think this might be the first time I can look back at a Feld menu and not remember any grave error or glaring flaw that confirms this is still an uneven, polarizing place. Certainly, there were highs and lows tonight—but many more of the former. Further, the quality of the weakest dishes (as well as the standard achieved on average) was notably than I’ve encountered in the past.

This is to say: Feld remains something of a rollercoaster, yet it’s a ride whose biggest thrills and overall entertainment value have become unimpeachable. Of course, personal taste and stylistic preferences may determine whether this tasting menu, among all others in Chicago, will meet expectations. Nonetheless, the team here has clearly settled into their role at the city’s vanguard of gastronomy, and anyone with an open mind can only find a concept worth cheering for.

It’s scary to think what Potashnick will achieve with more years and decades under his belt—with the help of a loyal crew, forged by those first weeks of tribulation, that has grown by his side. However, tonight, I already feel he is operating at a level close to Chicago’s finest restaurants. His cooking increasingly aligns (in thought and refinement) with what I love about Cellar Door Provisions, Elske, or Smyth. The sense of warmth he has built matches the intimacy that makes Kyōten and Oriole so special. He has packaged it all in a format that is totally singular. He is no pretender but, now, a true peer.

In not so many words, I express this sentiment to the chef as I leave: hands sticky with marshmallow, heart full from the kind of redemption that makes everything Feld has always stood for suddenly important, respected, and real. Potashnick’s appreciation is genuine, and my enthusiasm doubles. Little more than a year in, this is an absolutely essential restaurant and one that will reward repeat visits like few other I know.

In ranking the evening’s dishes:

I would place the “Turnip Velouté—Apple,” “Carrot Cake,” and “Sweet Potato—Pecan” in the highest category: superlative items that stand among the best things I will be served in any restaurant this year.

The “Preserved Strawberry,” “Foie Panisse,” “Cured Scallop,” “Winter Spinach—Goat’s Butter,” “Gilfeather Rutabega—Chestnut,” and “Smoked Celeriac—Pleasant Ridge” land in the following stratum: great recipes that achieved a truly memorable degree of pleasure. I would love to encounter any of these again.

Next come the “Mushroom Tea,” “Lobster Tail Pancake,” “Lobster Knuckle Salad,” “Duck Prosciutto,” “Parsnip Tart,” “Citrus—Fig Leaf,” ”Grilled Scallop—Smoked Garlic,” “Butternut Squash—Chestnut,” “34-Day Au Bon Canard Muscovy Duck,” “Rush Creek Reserve,” “Svenska Kakaobolaget,” “Fresh Fruit on Ice,” and “Malört Canelé”—good—even very good—preparations I would always be happy to sample again (but that just failed to elicit an extra degree of emotion).

Finally, there’s the “Tempura Acorn Squash,” “Nasturtium & Quail Egg,” “Duck Leg Terrine,” “18-Month Benton’s Ham,” “Golden Beets—Rosemary,” and “ABC Foie Gras—Sunchoke—Apricot”—merely good (or maybe just intriguing) items that fell short when it came to texture and/or flavor. That said, the underlying ideas shaping these dishes were sound, and they could easily be improved with a little more fine-tuning.

Overall, this makes for a hit-rate of 79% (if one counts each component of “The Drop” separately) that could climb as high as 88% (if one counts “The Drop” as a single, successful course). Likewise, some 32% or 35% of dishes (depending on the chosen method of tallying) reach that “would love to have again” level of quality.

To avoid restating what I just wrote above, these are numbers that measure right up to my recent meals at Smyth, Kyōten, and Oriole. At their best (and commensurate with the premium they each charge), these restaurants can still probably outperform Feld. At a basic technical level, their cuisines are certainly more intricately fashioned and built upon a wider range of thoughtfully sourced ingredients. Chefs likes Shields, Phan, and Sandoval have pushed their craft to the point that they can legitimately create something their audience has never tasted.

Potashnick is note quite there, but he’s awfully close: weaving together his personal influences and relationships in a way, more than a year later, that is beginning to yield a singular style and—from time to time—a superlative degree of deliciousness. Even his worst efforts (that is, when certain products fail him or experimentation gets a little too weird) now reach the standard of being inoffensive or maybe even intellectually appealing.

Feld’s biggest accomplishment, through all its early tribulations, has really been the establishment of a space where its hyperseasonal cooking might be expected, accepted, and understood. “Relationship to table” is really just a kind of self-inflicted wound—or, I should say, an arbitrary framework that can be used to justify cooking that at times is repetitive or altogether sparse. Given that the concept is now sourcing more and more from the full breadth of this continent, one wonders if that slogan amounts to anything but a storytelling device.

Yet, in practice, the “relationship to table” ethos fuels real education and passion from the staff. It empowers the kitchen to serve deceptively simple, worshipful constructions that memorably showcase their chosen ingredients. It brands Feld in a manner that makes its deeper philosophical goals (for example, a vision of fine dining that not betrothed to usual suspects like caviar, wagyu, or truffle) digestible to the public.

Ultimately, I admire Potashnick’s vision. It represents the exact kind of reorientation (in expectation, imagination, and taste) that our dining scene has desperately needed. Even if Feld only starts the conversation and diffuses its ideas (however indirectly, imperfectly, or controversially) the sum effect will be monumental.

But, here and now, the restaurant already offers one of Chicago’s most engaging, enriching culinary experiences. It is, perhaps (and for anyone not inclined to regularly pay Smyth or Kyōten prices), the most repeatable tasting menu in town to boot.

After this meal, I struggle to think of many other places I’d rather return to. Yes, Feld is so close to the summit, and it’s really only the first of innumerable peaks this team—pursuing this process—will surely reach.