Over the past few years, you have observed several of Chicago’s notable wine lists undergo a striking change. Rather than merely recording each bottle’s essential details—name, appellation, producer, vintage, and price—or tacking on a few edifying specifics—the grape varieties implied by the appellation, the exact composition of that year’s particular blend—these menus have gone so far as to annotate their selections. That could mean a few evocative words or, perhaps, an entire phrase that serve to contextualize (and, in effect, sell) the wine in the absence of a living, breathing, wheezing sommelier.

These annotations transform the wine list from a staid, sometimes cryptic document—an imposing tome whose accent marks and umlauts stymie all but the most seasoned of oenophiles—into a legible, dare you say engaging survey of the restaurant’s cellar offerings. At the very least, these accompanying notes communicate—implicitly—that it is normal not to understand what distinguishes this bottle from that one. They form a friendly editorial voice that cuts through all the jargon and offers a direct route to guest pleasure. They ensure the wines meet each reader on their own terms, speaking a common tongue that transcends (but does not denigrate) cultivated expertise.

The establishments you have seen indulge in this practice are not quite in the “high luxury,” multi-Michelin star extended tasting menu genre. (Restaurants therein often privilege wine service and promote direct customer interaction with talented sommeliers who manage their cellars with the same care and vision that the chef applies to their cuisine). Rather, you have regarded these annotated, expository wine lists at critically acclaimed eateries—possessing a Bib Gourmand or single Michelin star—offering more varied beverage programs. Thus, the bottles they offer—while often notable—are balanced by robust sales of beer and cocktails. Staffing problems, especially post-pandemic, might privilege a more flexible beverage/floor manager role than a dedicated sommelier. Philosophically, the concept might simply view wine as an interchangeable accessory embedded within a more distinguished culinary experience.

Such a restaurant does not consciously court oenophiles or try very hard to convince the unwashed masses to join their ilk. Instead, its wine list lies in wait—on the back of a beverage menu or in its own clickable PDF—for those diners who show some curiosity towards fermented grape juice. Yet there is no sommelier on the floor, and the servers—while mechanically competent and proficient at offering recommendations—cannot quite keep up with all the minutiae relating to each new addition. (That is, unless they already happen to be a budding wine geek in their own right).

When the diner turns their attention towards the list, they must often juggle making conversation with their guests or directing the first moments of service. Casting your eyes across the page, they find their first anchor in some broad category: sparkling, white, red. Desperately decoding the document’s formatting, you reach for one of countless totemic words that form the crutch that guides the growth of fledgling taste. That could be a favored variety like Chardonnay, Pinot Grigio, or Sauvignon Blanc. It could be a trusted combination of grape and place like “Napa Cab” or “Willamette Pinot.” Or it might signal a stylistic preference such as rosé, skin-contact, or “natural” (low-intervention) wines.

If a given wine list lacks the two or three most prominent buckets that a prospective buyer—possessing a beginner’s knowledge—might defer to, it is easy for panic to set in. In such a situation, the menu’s plurality of languages and arcane geographical indicators give nothing away. You are placed on the back foot, feeling the seconds tick by as the other guests sit ignored. You draw on some sorry heuristic like picking the third- or fourth-most expensive bottle within a category that seems vaguely familiar. All the while, you dread having to reveal your ignorance, the ineptitude of any ventured pronunciation, to a roving sommelier. Luckily, there isn’t one—but you are left gambling on the server’s halfhearted promise that you made the right choice.

On some nights, things go your way: the wine list is so well-curated that it’s impossible to choose wrong (which is to say, a wine may not be to your taste but does, otherwise, comport itself well). On other occasions, the dosage on your Champagne is too low, the oak on your Chardonnay is too high, and that fresh and fruity red you were after turns out to be a tannic monster. All the time wasted browsing the selection (while guests waited to be amused) makes you now seem that much more foolish. Wine thus affirms it impenetrable status, parrying your curiosity and promoting still-safer, less imaginative means of choosing a bottle in the future.

This lamentable situation—in which imperfect consumer knowledge yields a subpar drinking experience—forms one of wine appreciation’s growing pains. However, at that crucial moment in which you search for something recognizable amidst a sea of unfamiliar options, an annotated wine list may serve to break the spell. Instead of reaching for a haphazard heuristic—and not having the expertise of a sommelier to draw on—you trust the calming voice that presides over the page. Opposite the names of aziende agricole, lieux-dits, and prädikate, you find plain English that promises this wine is like this and that wine is like that. It helps you find security in any choice—at any price—you might make while, at the same time, sounding the alarm bell regarding any stylistic disconnect.

This expository and descriptive practice of annotation can offer consumers the perfect nudge—towards following, but also confirming their better judgment—when engaging a wine list on their own. It can even serve as an effective tool in demystifying the beverage more broadly by allowing the reader to “reverse engineer” the document and understand how each of the pieces within each of the categories relate to each other.

Yet, just as easily, the wrong annotation can make a wine program—especially if its offerings are already fairly anonymous—seem consciously dumbed down. If the pricing is far from generous, the operation may seem positively predatory. And, at what point does the exposition totally preclude a sense of discovery or an opportunity to share sincerely in wine appreciation with a member of the restaurant’s staff?

You largely like what you have seen of the practice thus far in Chicago. Still, it may be fruitful to dig into a handful of the examples you have found and meditate on their distinct approaches to exposition and description. For, when executed with the right gusto, these annotations help deliver a finer caliber of wine to a wider array of willing customers who, by their patronage, then work to enrich (and expand) the programs of those restaurants prescient enough to provide that helping hand. If the dyed in the wool snobs can stand seeing a smidgen of their esoteric knowledge devalued, all drinkers may benefit from the more robust, responsibly directed demand. And those preeminent producers who benefit more from marketing magic than quality or value may finally see their hegemony threatened as a smaller share of the public need lean on their brand names.

But you get ahead of yourself.

You first recall seeing some form of annotation on Galit’s wine list back at the time of its April 2019 opening. The practice persists to this day, spanning a period that has seen the restaurant—in April of 2022—pick up a Michelin star. Bibendum, then, clearly does not view the expository notes as disqualifying when it comes to awarding his honors. Rather, in Galit’s case, the wine list works to engage and educate consumers for whom tasting Zach Engel’s modern, multicultural Middle Eastern cuisine already presents an entirely novel experience.

Looking at a version of the wine list from December of 2019, you note 27 annotations across four distinct categories and relative to a total of 66 bottle offerings. This means that more than 40% of the restaurant’s selection, at this time, featured some additional information to help guide guests’ decisions. Nonetheless, the nature of these notes can vary widely in tone and content from entry to entry.

In the “Fizzy, Zippy, Peppy, Bubbles” category, a Scribe “Pétillant Naturel” ($78) is labeled “this could be your new desert island wine.” Meanwhile, a “Solera” premier cru Champagne from R. Pouillon ($140) is described as “super bubbles & kinda like sesame oil.”

The “(white / rosé / orange)” section of the list’s “Middle East” category comprises five different annotations:

- A 2017 Cremisan “Star of Bethlehem” blend ($58) is distinguished by “native grapes from where wine started.”

- A 2017 Tishbi “Emerald” Riesling ($48) exclaims “emerald? more like diamond!”

- A 2015 Somek Chardonnay ($76) attests “I can’t believe it’s not butter!”

- A 2017 Domaine Du Castel Chardonnay ($130) asks “we’re not in California anymore, or are we?”

- And a 2017 Kontozisis Roditis ($74) is termed “funky orange wine for your weirdo needs.”

The “(red)” section of this same category yields eight more examples:

- A 2016 Weninger “Balf” Kékfrankos ($60) offers “pomegranate, paprika, white pepper” before asking “… are you Hungary yet?”

- A 2016 Alain Graillot “Syroco” Syrah ($72) gushes “yeah, wine from Morocco is excellent. it will MorROCco your world.”

- A 2014 Ramot Naftaly “Primo” blend ($132) promises “it has the name ‘Primo’ for a reason!”

- A 2008 Assaf “Reserve” Cabernet Sauvignon ($84) declares “when in Rome…I mean Israel.”

- A 2004 Domaine Tatsis “Goumenissa” ($110) is titled “the Barolo of Greece.”

- A 2017 Matar “Stratus” Shiraz ($86) is called “cloudy with a chance of spice.”

- A 2011 Margalit Cabernet Franc ($155) has the honor of being “so good chef named his daughter after it.”

- And a 2016 Domaine du Castel blend is termed—quite simply—“the ‘Caymus’ of Israel.”

Moving on to the “(mainly) Sonoma” category, you find three more examples in the “(white / rosé / orange)” section: a 2017 Martha Stoumen “Honeymoon” Colombard-based blend ($84) enthuses “’always the bridesmaid’ NO more!”; a 2018 Folk Machine rosé ($48) represents “the definition of rosé patio pounder”; and a 2018 Raeburn rosé ($60) exemplifies “if ‘ladies who lunch’ was a wine.”

The “(red)” section of this same category contains five more annotations:

- A 2017 Broc Cellars “Love Red” blend ($56) is highlighted as a “food-friendly wine.”

- A 2018 Martha Stoumen “Post Flirtation Red” blend ($68) is called “badass red juice.”

- A 2017 Donkey & Goat “The Bear” blend ($86) invites you to “’taste the rainbow.’”

- A 2015 Emeritus Pinot Noir ($125) “tastes so good make a grown man cry. sweet cherry pie.”

- And a 2016 Ridge “Lytton Springs” ($120) is celebrated as “picturesque from vineyard to bottle.”

The final category—“Pretty Much Everywhere Else”—offers four additional expository notes across both of its sections:

- A 2017 von Hövel Scharzhofberger Kabinett ($68) is labeled “not your mom’s riesling, but she would adore it.”

- A N.V. Silwervis “Smiley” Chenin Blanc ($54) boasts a “cool picture of a sheep head on the front label.”

- A 2016 Clos de Fous “Subsollum” blend ($58) is reminiscent of “toasted marshmallows on a campfire. grab the grahams.”

- And a 2017 Division “Lutte” ($90) asks “who needs pinot when ya got gamay, am I right?”

Before analyzing the prominent themes found across these 27 examples, it may be instructive to supplement them—as well as track any stylistic growth—by looking at an updated selection. A current version of Galit’s wine list (from September of 2022) shows some 25 annotations across the four same categories (and relative to a total of 50 bottle offerings). Even though, in the wake of the pandemic, the scope of the restaurant’s program has slightly contracted, the proportion of the restaurant’s bottle selection boasting expository notes has actually expanded to half.

In the “Fizzy, Zippy, Peppy, Bubbles” category, a Dalton “Pétillant Naturel” ($72) is described as “Israel’s first Kosher pet nat” and a Mersel “LebNat” rosé ($75) reveals that “these organic grapes replaced old hashish fields.”

The “(white / rosé / orange)” section of the updated list’s “Middle East” category comprises one old (“emerald? more like diamond!”) and two new expository notes:

- The 2018 Cremisan “Star of Bethlehem” blend ($56) now “supports a school & orphanage in Bethlehem.”

- And a 2021 Agur “Blanc” blend ($100) is simply termed “elegant as sh*t.”

The “(red)” section of this same category, once more, contains the most annotations. Some—like “are you Hungary yet?,” “’when in Rome’ … I mean Israel,” and “so good Chef Zach named his daughter after it”—have remained consistent yet been applied to different vintages or blends from the same producers. Meanwhile, a couple of the notes for familiar wines have changed:

- The Domaine Tatsis “Goumenissa” is no longer “the Barolo of Greece” but “the OG Greek natty winery.”

- The Domaine du Castel is no longer “the ‘Caymus’ of Israel” but described as “idk. this one slaps.”

Nonetheless, there are a couple new entries:

- A 2019 Dalton “Majestic” Carignan ($78) is labelled “glou glou from Galilee.”

- And a 2018 Dar Richi “Hanan” blend ($75) is branded “a love letter from a Syrian refugee.”

Galit’s updated “(mainly) Sonoma” category shows seven new examples across both of its sections:

- A 2021 Banyan Gewürztraminer ($42) is defined by “stone fruit and fresh cut flowers.”

- A 2020 Anthill Farms “Helluva Vineyard” blend ($75) is dubbed “your server’s fave.”

- A 2016 Iconic Wines “Heroine” Chardonnay ($120) is notable for having “just two barrels produced, treat yo’ self!”

- A 2015 Varner “Los Alamos Vineyard” Pinot Noir ($64) tastes “silky, savory, sultry.”

- A 2018 Hobo Cabernet Sauvignon ($64) is labelled “cabernet but made like pinot, the best of both.”

- A N.V. Sean Thackrey “Pleiades” XXVIII blend ($75) is termed “cool way before it was cool.”

- And a 2018 Martha Stoumen “Venturi Vineyard” ($98) is not “badass red juice” but—now—“badass funky red juice.”

Finally, the restaurant’s “Pretty Much Everywhere Else” category offers another half dozen new annotations. This comprises:

- A 2020 Nortico Alvarinho ($45) that offers “vinho verde like you’ve never had before” and prompts guests to “ask us about the tiles.”

- A 2021 Meinklang “Weisser Mulatschak” ($60) that embodies “peaches and cream.”

- A González Bastías “Naranjo” ($80) that forms “falafel’s BFF.”

- A 2019 González Bastías “Matorral” ($60) made from “200-year old vines…two hundred!”

- A 2015 Gönc Gamay ($54) titled “Beaujolais for punk rockers.”

- And a N.V. non-alcoholic Acid League “Proxies” ($45) described as a “fantastic rosé wine alternative.”

Surveying these roughly fifty unique examples of annotated wine selections, it is easiest to first group those entries that are purely expository. That includes notes like “native grapes from where wine started,” “Israel’s first Kosher pet nat,” “these organic grapes replaced old hashish fields,” and “supports a school & orphanage in Bethlehem.” It may also include, to a lesser extent, annotations like “the OG Greek natty winery”; “a love letter from a Syrian refugee”; “just two barrels produced, treat yo’ self!”; and “200-year old vines…two hundred!” that contain a factual core but embellish it just a bit.

Opposite these fairly straightforward, factual annotations, you would place those that are more interpretative and descriptive. This would include examples like “super bubbles & kinda like sesame oil”; “I can’t believe it’s not butter!”; “pomegranate, paprika, white pepper … are you Hungary yet?”; “cloudy with a chance of spice”; “tastes so good make a grown man cry. sweet cherry pie”; “toasted marshmallows on a campfire. grab the grahams”; “stone fruit and fresh cut flowers”; “silky, savory, sultry”; and “peaches and cream.” While some of these notes are cloaked in a layer of humor, they each communicate one or more distinct flavors that can be found in the wine.

By comparison, annotations like “funky orange wine for your weirdo needs”; “the Barolo of Greece”; “the ‘Caymus’ of Israel”; “the definition of rosé patio pounder”; “food-friendly wine”; “not your mom’s riesling, but she would adore it”; “elegant as sh*t”; “glou glou from Galilee”; “vinho verde like you’ve never had before. ask us about the tiles”; “falafel’s BFF”; “Beaujolais for punk rockers”; “fantastic rosé wine alternative”; and “cabernet but made like pinot, the best of both” are somewhat descriptive but largely less useful. This is because they draw on rather general terms—“funky orange,” “food-friendly,” “elegant,” “glou glou”—or, otherwise, make comparisons to wine styles and regions that demand some greater vinous knowledge to be legible.

Lastly, somewhere in-between the expository and descriptive poles lands a set of annotations that you can best term non-sequiturs. These examples do not provide factual information on the wines, nor do they engage in any valuable interpretation of their characteristics. Rather, the notes comprise the most general sort of praise, indulge in wordplay, or venture forth an unrelated fun fact. They are kind of like filler—or a clever form of salesmanship—that engages guests on certain bottles even if there is nothing much to say. Tellingly, this style of annotation is the most numerous across Galit’s list.

Examples include “this could be your new desert island wine”; “emerald? more like diamond!”; “we’re not in California anymore, or are we?”; “yeah, wine from Morocco is excellent. it will MorROCco your world”; “it has the name ‘Primo’ for a reason!”; “when in Rome…I mean Israel”; “so good chef named his daughter after it”; “’always the bridesmaid’ NO more!”; “if ‘ladies who lunch’ was a wine”; “badass red juice”; “picturesque from vineyard to bottle”; “cool picture of a sheep head on the front label”; “who needs pinot when ya got gamay, am I right?”; “idk. this one slaps”; “your server’s fave”; “cool way before it was cool”; and “badass funky red juice.”

Some of these, you must admit, are not quite meaningless. Knowing Zach Engel named his daughter after the Margalit wines is the kind of detail that a diner, enthused about visiting the chef’s restaurant but lacking any particular comprehension of the wine list, is likely to seize on. Likewise, describing a Colombard-based white blend as “’always the bridesmaid’ NO more!” is actually a rather clever way of referencing the grape’s historically diminutive role in Cognac production. Also, “ask us about the tiles” certainly deserves credit for prompting a deeper conversation with the staff. (Hell, you even think comparing a rosé of Zinfandel to Sondheim’s wry send up of society women from Company might be genius).

However, more broadly, this “middle category” of non-sequiturs is mostly an exercise in playfulness. It works to make the wine list seem like less of an intimidating tome. This style of annotation may not educate guests and aid them in making an intelligent decision. But, for a selection of Galit’s size, you trust that each bottle has already been curated with care. Thus, a totally silly note appended to this or that wine only provides a gentle nudge—if the customer is game—towards making one good choice over another.

Are these notes—which are neither expository nor descriptive—better than nothing? Well, it depends on the tone and tenor of the experience which the restaurant endeavors to construct. Working within a distinctive genre and offering Middle Eastern wines that are almost entirely unknown to the mainstream, you think Galit’s annotations—even the non-sequiturs—affirm the “shalom y’all” attitude that forms a key part of the concept’s identity. Any notion that the wines are dumbed down by such frippery must be measured against the reality that many of the more esoteric selections would, otherwise, simply be ignored.

While Galit’s annotated wine list has formed a part of the restaurant’s identity since the beginning, Monteverde—which opened in 2015—has only started the practice over the past couple years. That may seem like something of a curious choice for a pastificio that has remained wildly popular since its opening—and whose wine program, over the years, has featured illustrious names such as Selosse, Keller, Mascarello (Giuseppe), and Soldera. However, as cult producers have increasingly become unaffordable (or even unobtainable) in Chicago, Monteverde has pivoted towards offering drinkers greater value via obscure Italian varieties from oft-ignored regions.

It follows that these wines—lacking the easy appeal of Prosecco or Pinot Grigio and the cachet of Barolo or Brunello—can polarize consumers. A certain sect may jump at the chance to try something totally new, soliciting the opinion of the staff and selecting a bottle that matches their stylistic preference. But you believe the bulk of diners, having worked quite hard to secure a reservation at Grueneberg’s restaurant, simply want to sit back and enjoy the food. They might be willing to splurge on a wine of commensurate fineness, yet they do not expect to work too hard to decipher what that might be. The great names from the most legendary appellations, as well as internationally-styled “Super Tuscans,” provide the path of least resistance. Yet Monteverde has largely forsaken offering these (often perpetually too-young) cult wines even if a certain demographic, taste be damned, would snatch them up.

The restaurant’s program has, instead, privileged the harder work of exploration and education. It uses the pulpit its popularity provides to advance the appreciation of Italian wine well beyond the point they can most effectively profit from it. Thus, while many of the list’s selections may prompt a moment of pause, its annotations—delivered in a concise, confident voice—ensure expert guidance is always close at hand. They subvert any desire to turn tail at sight of the strange bottles and, instead, invite readers to engage further and take a leap.

As with Galit’s annotations, the accompanying notes affixed to Monteverde’s wine list strike a balance between expository and descriptive interpretations of a given bottle. Some selections comprise solely the former, others solely the latter, and still others an elegant blend of the two.

What’s missing, in this case, are the “non-sequiturs” that injected Galit’s list with a dose of humor. However, while that restaurant only annotated about half of its items, Monteverde appends notes to each and every option—numbering somewhere between 70 and 80 bottles in total at any given time. Thus, while Galit’s non-sequiturs can be termed a form of “filler” used to flesh out the document’s sense of personality, Grueneberg’s list maintains a professional, focused tone. Moreover, its annotations are exhaustive—meaning that readers are not any more likely to be steered towards a certain wine on account of its extra information (or lack thereof). With this in mind, you will survey a recent copy of Monteverde’s list (also accessible here) without transcribing each and every entry (as done with the prior example).

On the more expository side, you are struck by the following annotations:

- A note under the 2014 Geoffroy “Empreinte” ($183) describes how “the Geoffroy family have been winemakers in Cumières since the 17th C. Jean-Baptiste & father Rene Geoffroy tend to 14 hectares of vines, 11 of which lie in Cumières. 75% oak aging adds hints of baked apple and toasted brioche with an elegant & brilliant acidity.”

- A 2020 Prevostini “Monrose” ($60) tells the story of its producer: “the Prevostini family has been making wines on the terraced slopes of Valtellina, in Lombardy since the mid 1940s. this rosé is joyous with beautiful notes of bright cherry, fresh raspberries & subtle rose.”

- Paolo Bea’s 2014 “Arboreus” ($171) is distinguished by its farming: “these vines are up to 130 years old & wrap themselves around trunks & limbs of trees in the vineyards—this is old school winemaking at its best. this richly spiced wine is woven with hints of orange rind, deep apricot & crushed flower petals.”

- A 2020 Caruso & Minini “Naturalmente” Catarratto ($56) references the firm’s past: “Caruso & Minini’s history harks back to the late 1800s when they grew grapes for the nearby Marsala factories. tropical fruit, white flowers & bright citrus.”

- The 2019 “Montmains” Chablis from Gérard Duplessis ($157) looks toward the wine’s terroir: “the vineyards of Duplessis are all planted on Kimmeridgian soil & mostly situated on Grand Cru sites! minerality sings with a highly textured palate that is harmonious with its weight and power.”

- A 2020 G.D. Vajra Dolcetto ($64) tells the story of the domain’s founding: “Aldo Vajra’s father sent him to the countryside of Barolo in 1968 to keep him from protesting in the streets, and hence this great estate was born.”

- San Giorgio’s 2017 “Ugolforte” Brunello di Montalcino ($180) is “named after a local ‘Robin Hood’ who led the people of Montalcino against the occupying forces in the 12th century. a dark beauty, impressing with its youthful poise.”

- Lastly, Grattamacco’s 2017 “L’Alberello” ($300) is contextualized as “Italy’s second Super Tuscan in Bolgheri, after Sassicaia. this is all class–everything you are looking for in a Super Tuscan.”

By comparison, on the more descriptive side, you are struck by these entries:

- The 2017 Le Marchesine Franciacorta ($105) is called “Italy’s answer to Champagne. Buttery brioche & ripe pears.”

- A 2020 Villa Sparina rosé ($50) is reminiscent of “red cherry & pink flowers.”

- Villa Sparina’s 2021 Gavi di Gavi ($52) tastes “peachy & mineral, clean & crisp.”

- The 2021 Marine Dubard “Coeur du Mont” ($52) is “citrusy & delightful.”

- A 2021 Cantina Barbera “Tivitti” ($52) is “salty like the Sicilian breeze. Tropical fruit & peach blossoms.”

- Capolino Perlingieri’s 2020 “Nembo” ($60) is characterized by “stone fruit, nutty tones, bright & lively.”

- La Kíuva’s 2020 “Rouge de Vallée” ($56) is labelled an “alpine red redolent of candied cherry & fresh violets.”

- Montaribaldi’s 2019 “Gambarin” ($76) “boasts bright floral aromas, tart raspberry fruit & elegant tannins.”

- A 2011 “Il Motto” from La Torretta ($120) is described as “open and giving now at 10 years of age. strawberry & black cherry with a typical, grippy finish.”

- The 2018 Barolo del Comune di La Morra by Trediberri ($175) is defined by “sweet red cherry, orange peel & baking spice all wrapped up in a nuanced package.”

- A 2021 Calabrese/Nocera blend from Nesci ($72) is “robust & round with brightly layered plum & cherry fruit backed by interwoven tannins.”

- Dei’s 2015 “Bossona” Vino Nobile Riserva di Montepulciano ($163) displays “dark plum, anise, and pipe tobacco, set across a finely knit tannic backbone.”

- Ciacci’s 2020 “Piccolomini” Rosso di Montalcino ($97) is “bright & full of beautiful wild berry fruit with mineral & herbal tones.”

- Lastly, the 2019 Ruché-based “L’Accento” from Montalbera ($65) is “bursting with rose & violet aromas, sweet & candied black cherry.”

Nonetheless, the most effective annotations, by your measure, fluidly combine both expository and descriptive properties into a single package. Examples include:

- A 2016 Ferrari “Perlé” ($115) described as “100% Chardonnay. like Franciacorta, made in the same way as Champagne. elegant & lithe.”

- The 2018 Scammacca del Murgo sparkling rosé ($101) made from “100% Nerello Mascalese grown on the slopes of an active volcano. strawberry, cherry, pomegranate.”

- Cosimo Maria Masini’s 2018 “Daphné” ($88) benefits from “extended skin-contact [which] lends a golden hue. headily floral, textured, herbal & oxidatively nutty.”

- The 2017 Ronco Severo ($84) asks, “expecting your average pinot grigio? this ain’t it. curious about orange wine? give this a try. blood orange, guava, and dried mandarins.”

- A 2020 Ghiomo “Inprimis” ($60) reveals that “Ghiomo takes its name from a tool used in the production of wine barrels. this Arneis boasts fresh floral notes with stonefruit and lean tropical fruit tones.”

- Benanti’s 2019 “Contrada Cavaliere” ($155) recounts how “the Benanti family were one of the first to belive [sic] in serious viticulture on mount etna. stone fruit, dark minerality, coupled with waxy herbal tones.”

- The 2019 La Rivolta “I Vigneti di Bruma” ($56) features “a grape indigenous to Campania, just inland from Naples. sweet almonds & pears.”

- Cantina Terlan’s 2021 “Cuvée Terlaner” ($90) is simply “one of Italy’s top wines. Pinot Bianco blended with Chardonnay and Sauvignon Blanc. elegant with mineral, citrus & yellow apple note[s].”

- The 2019 Arnot-Roberts “Watson Ranch” ($121) goes back to the beginning: “Arnot-Roberts was started by two childhood friends with one barrel of wine made in their Healdsburg basement. this Chardonnay is airy with layers of stone fruit, exotic spices & herbal tones. highly textured & energetic, light on oak.”

- The 2018 Fossil Point ($64) justifies its value placement on the list: “out of 30+ Pinot Noirs we tasted this hit the spot for us with vibrant red plum and blackberry.”

- A 2020 Pasquale Pelissero “La Ferma” promises, “if you love the wines of Piedmont & haven’t tried Fresia, buckle up. super lively strawberry & raspberry tones with just the right amount of grip.”

- Rainoldi’s 2016 “Inferno” Valtellina Superiore ($72) paints a captivating picture: “the Inferno vineyards are staggeringly steep–grapes at Rainoldi are hand-harvested, then flown out by helicopter! Valtellina, in Lombardy, is Nebbiolo’s birthplace. layers of red fruit, herbs & pipe tobacco.”

- The 2018 Cascina delle Rose “Rio Sordo” Barbaresco ($197) offers a concise depiction of the appellation: “Barbaresco is the softer counterpart to Barolo. an elegant wine that shows grace & ethereal aromatics with a firm backbone.”

- Emidio Pepe’s 2010 Montepulciano ($501) enthuses, “perhaps the oldest and most genuine ‘natural wines’ in Italy, and not a hipster in sight! super small organic production, 15 hectares in total. the wine is finely knitted with aromas of ripe red berries, dark plum & violet with hints of cumin & caraway.”

- A 2017 Beconcini Chianti Riserva ($68) is made from “60 year old Sangiovese vines [that] produce beautiful fruit that is woven with bright cherry tones & just the right amount of tannin.”

- The 2019 Poggerino “(N)uovo” Chianti Classico ($93) is “aged in large cement eggs, 100% Sangiovese that shows the grape’s complexity & elegance.”

- Salicutti’s 2016 “Piaggione” Brunello di Montalcino ($290) comes from “the first winery in Montalcino to be certified organic, now using biodynamic practices. crushed raspberry & tart cherry with dark spice overtones.”

- Ronchi di Cialla’s 2018 “Rinera” ($80) recalls how “the Rapuzzi family prevented Frulian varietals such as Schioppettino from going extinct. tart cherry & cranberry with a peppery edge.”

- Lastly, a 2018 Luigi Maffini “Klèos” ($68) affirms that “Aglianico is the ‘King’ of southern Italian wine. dark black fruit & mineral with just the right amount of muscle.”

Despite broadly being well executed, Monteverde’s annotations do comprise a handful of weaker examples whose highlighting may be instructive. These include:

- A N.V. Victorine de Chastenay ($64): “who doesn’t love sparkling rosé?!?”

- A 2021 Sinskey “Vin Gris” ($99): “provence-esque from a cult california producer.”

- A 2021 Vajra “Rosabella” ($60): “this wine is FUN! summer cherry & wild strawberry, a treat to be had.”

- A 2020 Bisson “U Pastine” ($72): “Bisson rescued this rare grape from obscurity. pair with pesto.”

- A 2021 Elena Walch ($58): “5th generation female-owned winery. taste true pinot grigio.”

- A 2019 Chalone Monterey ($68): “OG Cali Chard…just the right amount of oak.”

- A 2016 Weingut Gottardi ($150): “there’s a decent amount of Pinot in Italy, but not all of it’s great. try this one.”

- A 2017 Luigi Scavino “Azelia” ($125): “Galloni calls this estate an ‘undiscovered gem,’ and we couldn’t agree more–we’ve followed them for a number of years. dark & brooding this vintage, this is a great Barolo.”

- A 2017 Bruno Giacosa “Rabajà” Barbaresco ($537): “Giacosa needs no introduction—without a doubt, one of Piedmont’s most sought after producers. Today, Bruna follows in her father’s footsteps. dark fruit with spice and licorice. young, but enticing.”

- A 2018 Buglioni “Il Bugiardo” Ripasso Valpolicella ($85): “il bugiardo means ‘the liar.’ tastes so good it must be Amarone, not “just” Ripasso!”

- And, lastly, a 2016 Arnaldo Caprai “Collepiano” ($149): “usually drink Napa Cab, but up for an adventure? Sagrantino could be your new love.”

This final set of examples features a couple annotations that—on account of their enthusiasm—remind you of Galit. However, while “who doesn’t love sparkling rosé?!?” and “pair with pesto” and are not quite so descriptive, “this wine is FUN! summer cherry & wild strawberry, a treat to be had” manages to balance excitement with some clarity as to the character of the wine’s fruit.

Other notes—like “provence-esque from a cult california producer,” “5th generation female-owned winery. taste true pinot grigio,” “OG Cali Chard…just the right amount of oak,” “there’s a decent amount of Pinot in Italy, but not all of it’s great. try this one,” “il bugiardo means ‘the liar.’ tastes so good it must be Amarone, not “just” Ripasso,” and “usually drink Napa Cab, but up for an adventure? Sagrantino could be your new love”—seem to speak directly to the reader. They nudge the diner towards this or that bottle on the basis of a comparison to another kind of wine—Provence rosé, “fake” Pinot Grigio, “OG Cali Chard,” “not great” Pinot, Amarone, Napa Cab—without offering up any descriptive notes to guide those who know nothing about what is being referenced.

Thus, even if some of the expository elements are enticing, these annotations demand that the consumer rely on the restaurant’s general recommendation rather than equipping them to evaluate each option’s characteristics—like nearly all others across the list—in plain English.

Finally, you single out “Galloni calls this estate an ‘undiscovered gem’” and “Giacosa needs no introduction—without a doubt, one of Piedmont’s most sought after producers” because they defer to critical authority and market conditions as a means of constructing the wines’ reputations. Neither Antonio Galloni’s opinion nor any degree of perceived collectability would mean a thing to an aspirational drinker looking to splurge on one of the bottles and wondering what actually makes them (in a nontautological sense) great. Nonetheless, both of these annotations still offer a descriptive element: “dark & brooding” and “dark fruit with spice and licorice. young, but enticing” respectively.

These descriptions, you think, form the key to Monteverde’s entire annotation practice. They guarantee—in all but eight cases outlined above—that even the most colorful exposition is given practical grounding. For all the most expository entries, save for two, are capped off with a descriptive sentence: something like “layers of red fruit, herbs & pipe tobacco” or “grace & ethereal aromatics with a firm backbone.”

In fact, the two purest expressions of exposition—“Aldo Vajra’s father sent him to the countryside of Barolo in 1968 to keep him from protesting in the streets, and hence this great estate was born” and “Italy’s second Super Tuscan in Bolgheri, after Sassicaia. this is all class–everything you are looking for in a Super Tuscan”—actually seem deficient.

They tell a story that seems largely pointless to those who are not already sold on the sterling quality of the wine. They lack any identifying characteristics for those who might like to take a punt on something new. So, ultimately, these annotations must be placed in the same class as those eight non-descriptive examples. (And “everything you are looking for in a Super Tuscan” certainly echoes the archetypal comparison made with “OG Cali Chard” or “Napa Cab”).

Overall, while Monteverde’s annotated wine list is less frivolous and fun than Galit’s (two factors that should not be discounted in appealing to a certain entry-level class of drinker), the former’s entries—in their comprehensiveness—help to elucidate the best practices when it comes to writing such notes.

Pure exposition offers an objective historical, cultural, or technical context through which the customer can better appreciate a wine. At the same time, it avoids trekking into the murky area of tasting and interpretation—a task fraught with peril unless the writer of the resulting notes possesses a robust, confident palate. While pure exposition proves itself superior (in practical terms) to the kind of non-sequitur salesmanship that forms the Galit list’s filler, it can prove equally mind-numbing. For one sort of customer may roll their eyes at a reverential screed just as another does so at some flippant attempt at humor.

No, exposition should ideally be leavened by a dose of description if it is to achieve its full impact. Galit, surely, has its descriptive annotations—like “stone fruit and fresh cut flowers”; “silky, savory, sultry”; and “peaches and cream.” And Monteverde’s list contains a bevy of them, too, like “red cherry & pink flowers”; “peachy & mineral, clean & crisp”; and “citrusy & delightful.” However, in Galit’s case, these descriptive phrases are appended only to a handful of the restaurant’s selections. In Monteverde’s case, they feature in all but the aforementioned ten (out of 70 to 80 total bottles) entries.

Thus, it is fair to say that descriptive phrases form the foundation of Monteverde’s annotation practice and the basis from which additional exposition flows. Any guest, reading about almost any wine, is sure to find a few evocative words that describe the bottle’s aroma, fruit character, texture, acidity, and/or finish. Comparing these notes—and placing them relative to the customer’s desired price point—allows would-be imbibers to quickly determine the right intersection of style and value.

When confronted by multiple wines that—being made from the same grape or appellation—share stylistic elements and come in at a similar price, guests will find that exposition then forms the distinguishing factor.

Rather than the 2017 “Azelia” ($125)—Galloni’s “undiscovered gem” of an estate—customers may opt for the 2011 “Il Motto” ($120) after reading it is “open and giving now at 10 years of age.” Likewise, while the 2018 Trediberri Barolo ($175) offers appealing notes of “sweet red cherry, orange peel & baking spice all wrapped up in a nuanced package,” the 2018 Cascina delle Rose Barbaresco ($197) may win out because the appellation offers a “softer counterpart to Barolo.”

Ultimately, the best annotations tell a singular story—of “two childhood friends” who started “with one barrel of wine,” “hand-harvested” grapes that are “flown out by helicopter,” or of a family that “prevented Frulian varietals such as Schioppettino from going extinct”—and balance that with concise description: “airy with layers of stone fruit, exotic spices & herbal tones. highly textured & energetic, light on oak”; “layers of red fruit, herbs & pipe tobacco”; or “tart cherry & cranberry with a peppery edge” (respectively).

Based on your analysis of Monteverde’s annotated wine list, you are led to create the following hierarchy of the entries (relative to their effectiveness at guiding consumer purchasing decisions): expository + descriptive (best), purely descriptive, descriptive via comparison, purely expository, non-sequitur (worst).

This model may prove useful as you turn to your next two examples of the practice.

Roister, like Monteverde, has only recently transitioned its wine list into an annotated form. The shift, by your measure, has only occurred some time over the past year. It reflects, at the very least, a sign of intention from The Alinea Group to bolster what has always seemed to be a desperately underwhelming program. (Oh, the nerve of hosting those deeply flawed “Collector Series” dinners downstairs with nary a drop to drink upstairs!)

Nonetheless, you have given credit to mothership Alinea—after its “3.0” renovation—for reconfiguring its own bottle tome to encompass the full splendor of its cellar. And, thus, you viewed this change at Roister favorably—even taking it as an occasion to break your tacit boycott of the group’s properties and pay the restaurant a visit.

Brunch that day was merely fine, but you appreciated the chance to engage with the updated bottle list in person. It offers, relative to Galit and Monteverde’s more thematic constructions, a blank canvas for Roister to affirm—beyond the live fire (and Brochu’s fried chicken recipe)—just what its identity is. Plus, relative to the group’s other establishments (that privilege pairings), the selection could provide a chance for the group to assert its credentials and buying power when it comes to securing the allocated, crushable, high-quality-to-price-ratio wines every savvy sommelier yearns to stock.

Truth be told, Roister’s wine list is still hardly inspiring given its group’s reputation. Yet it offers some rather interesting grist for your mill when it comes to analyzing annotations. The current selection can be accessed from this page (while a partial, archived version consistent with the time of this article’s publication can be found here).

Though Roister cannot claim the same comprehensive as Monteverde when it comes to annotations, the restaurant clearly surpasses Galit by offering notes on 74 of 83 bottles (nearly 90% of the offerings). Due to the number of entries this entails, you will approach your analysis as you did the previous example, grouping wines by their purely expository, purely descriptive, hybrid, flawed, or non-sequitur content.

In the purely expository realm, you find the following examples:

- Gloria Ferrer’s Blanc de Blancs ($66) is celebrated as “the first sparkling winery in Carneros.”

- Bollinger’s “Special Cuvée” ($155) has the honor of being “007’s favorite in most of the books and movies.”

- Domaine Carneros’s 2016 “Le Rêve” ($190) comes from “the American branch of Taittinger.”

- The Brut rosé from Roederer Estate ($99) reflects “Roederer’s Anderson Valley outpost.”

- The rosé from Billecart-Salmon ($170) is an expression of “one of the oldest and greatest houses in Champagne.”

- Shafer’s 2019 “Red Shoulder Ranch” ($146) reveals that “the 1st vintage of this hit Wine Spectaor’s [sic] Top 10” and “they haven’t slowed down since.”

- Littorai’s 2018 “Charles Heintz Vineyard” ($150) explains how “Ted Lemon was the first American to head a winery in Burgundy” and that “Littorai is his.”

- The 2019 Grgich Hills “Paris Tasting” ($160) affirms that “Mike Grgich is a legend” before noting that “this is usually only available to their wine club.”

- A 2019 “La Genelotte” Meursault-Blagny from Comtesse de Chérisey ($200) is a “monopole wine from an historic corner of Burgundy.”

- The 2021 Gundlach-Bundschu Gewürztraminer ($56) reflects “six generations of family winemaking” (which “is no big deal in Europe” but “in the US it’s amazing”).

- Tablas Creek’s 2018 “Esprit Blanc” ($79) is made up of “Rhône varietals from vine cuttings from Château de Beaucastel.”

- Michael Lavelle’s 2021 “Iris” rosé ($49) is called “an absolutely delicious offering” that comes “from one of the few black-owned wineries in the US.”

- The 2018 J. Christopher “Basalte” ($65) is labelled “Ernst Loosen’s (Dr. Loosen) Oregon Pinot passion project.”

- Eyrie Vineyards’ 2017 “Sisters Vineyard” ($105) comes from “a pioneer in Oregon wine” that “remains one of the best.”

- The 2019 “Ama” from Peay ($140) offers “organic, cool-climate Cali Pinot from winemaker Vanessa Wong.”

- Reeve’s 2019 “Special Reserve” ($154) is the product of “only six barrels made.”

- The 2020 Occidental “Freestone-Occidental” ($160) is “from Steve Kistler’s (yeah, that one) new project.”

- A 2018 Reeve “Kiser Vineyard, Suitcase Block” ($182) is named “Suitcase” because “they clipped DRC vines and brought them back coach.”

- Tablas Creek’s 2018 Grenache ($85) is “from the Perrin family who owns Ch. De Beaucastel (see below).”

- The 2019 Château de Beaucastel Châteauneuf-du-Pape ($265) comes from an “Iconic producer for the region.”

- Seghesio’s 2019 “Rockpile Road Vineyard” ($115) is sourced from an estate that has “been making Zin since 1895….”

- A 2015 “Imperial” Rioja by CVNE ($160) is called “the flagship of a classic OG Rioja winery.”

- The 2016 “Ranch No. 1 Maestro Reserve” by Beaulieu Vineyard ($66) is “a Napa valley stalwart — one of the originals.”

- Reeve’s “Libertine #6” ($90) offers a “Super Tuscan by way of CA: Cab, Cab Franc, Sangiovese, Merlot.”

- Heitz’s 2017 Cabernet Sauvignon ($147) is distinguished as being from “one of the few wineries in Napa to still offer a free tasting, pure class.”

- The 2018 Château Grand-Puy-Lacoste ($220) is produced by a “5th growth estate that more than deserves a promotion.”

- The 2018 Château Leoville Barton ($230) is made by a “2nd growth that also deserves a promotion.”

- Meanwhile the 2018 Pavillon Rouge du Château Margaux ($379) is a “2nd Label from the iconic 1st Growth Château.”

- Shafer’s 2017 “Hillside Select” ($395) is termed “John Shafer’s magnum opus.”

- Produttori del Barbaresco’s 2018 Barbaresco ($90) comes from “the cooperative that put Barbaresco on the world stage.”

- The 2017 Brunello di Montalcino by Altesino ($125) is noted to be from “the first Brunello producer to use new oak barriques.”

- Borgogno’s 2017 Barolo ($160) is labeled an “iconic producer of old-school style Barolo.”

- Quintarelli’s 2014 Valpolicella Classico ($198) is a wine from “the godfather of the Veneto and perhaps the best producer of the style.”

- Allegrini’s 2013 “La Poja” ($281), by comparison, comes from “the ‘rebel’ of Valpolicella.”

- And, lastly, Ceretto’s 2016 “Bricco Rocche” ($385) represents “the vanguard of the modern style Barolo.”

Looking at this mass of expository examples, you must first praise Roister’s wine list for the conciseness of its annotations, which in almost every case are limited to one singular phrase. This, in some ways, prevents the restaurant from adopting the storytelling or hybrid styles of notes seen at Monteverde. Nonetheless, it makes for a document that is easy on the eyes and less likely to flummox consumers for whom wine already presents an impenetrable subject.

Of these entries, there are a handful that you find particularly alluring: “007’s favorite in most of the books and movies”; “Ted Lemon was the first American to head a winery in Burgundy. Littorai is his,” “Six generations of family winemaking is no big deal in Europe, in the US it’s amazing,” “Rhône varietals from vine cuttings from Château de Beaucastel,” “‘Suitcase’ because they clipped DRC vines and brought them back coach,” and “one of the few wineries in Napa to still offer a free tasting, pure class.”

Nonetheless, some of these expository annotations amount to little more than fun facts—“the first sparkling winery in Carneros,” “the American branch of Taittinger,” “Roederer’s Anderson Valley outpost,” “the 1st vintage of this hit Wine Spectaor’s [sic] Top 10,”—or trite references—“one of the oldest and greatest houses,” “iconic producer for the region,” “from Steve Kistler’s (yeah, that one) new project,” “John Shafer’s magnum opus,”—that ultimately communicate little about the wine’s terroir or manner of production.

Some of the Italian display notes that reference particular styles: “iconic producer of old-school style Barolo,” “the godfather of the Veneto and perhaps the best producer of the style,” “the ‘rebel’ of Valpolicella,” or “the vanguard of the modern style Barolo.” However, to the uninitiated drinker, these distinctions—old-school and modern, godfather and rebel—mean nothing. Likewise, those who do understand these paradigms are not the sort who need to rely on annotations that lack any further contextual or descriptive information.

Still, you think the list displays a wide array of fairly ordinary expository notes that should be commended for plainly stating some relevant detail about the wine: “this is usually only available to their wine club,” “monopole wine from an historic corner of Burgundy,” “six generations of family winemaking,” “organic, cool-climate Cali Pinot from winemaker Vanessa Wong,” “only six barrels made,” “they’ve been making Zin since 1895…,” “Super Tuscan by way of CA: Cab, Cab Franc, Sangiovese, Merlot,” “2nd Label from the iconic 1st Growth Château,” and “the first Brunello producer to use new oak barriques.”

When it comes to purely descriptive annotations, Roister offers about the same amount as Monteverde but constructs them with far greater restraint. Examples include:

- Livio Felluga’s 2019 Pinot Grigio ($70): “most pinot grigio is boring, Felluga’s style sees aging on the lees for complexity.”

- Albert Boxler’s 2018 “Sommberg” ($150): “a full-bodied pinot gris from the master of the style.”

- J.J. Prüm’s 2020 “Wehlener Sonnenuhr” Kabinett ($95): “German wine labels are tough – this is a light style, delicious and only a little sweet Lush and crisp.”

- Dr. Loosen’s 2017 “Ürziger Würzgarten” ($135): “Riesling can be dry, here’s the proof.”

- Groth’s 2021 Sauvignon Blanc ($68): “gotta love a wine called ‘lush’ and ‘succulent’!”

- Domaine Vacheron’s 2020 Sancerre ($105): “no silex in the name, but the flint is prominent in this classic producer.”

- Domaine Huet’s 2019 “Le Haut-Lieu” ($86): “peak Chenin Blanc.”

- Saintsbury’s 2019 “Sangiacomo Vineyard” ($75): “when Chardonnay is done with just the right amount of oak, it’s a beautiful thing….”

- Rhys’s 2018 “Alesia” ($80): “elegant Chardonnay from only mountain vineyards.”

- William Fèvre’s 2019 “Vaillons” ($150): “no new oak anywhere near this; the perfect oyster wine.”

- Do Ferreiro’s 2020 Rias Baixas ($66): “the iconic example of the Albariño grape: apricot, peach, and mouthwatering acidity.”

- Jermann’s 2019 “Vintage Tunina” ($120): “honey and flowers and white peach…oh my!”

- Hirsch’s 2019 “The Bohan-Dillon” ($85): “Jasmine Hirsch makes some of the most light and elegant Pinot in California.”

- Radio-Coteau’s 2018 “Las Colinas” ($117): “cool climate California syrah capturing the essence of the Sonoma Coast.”

- Numanthia’s 2013 “Termanthia” ($299): “big, lush, point-chasing (and scoring) wine made from 100% Tempranillo.”

- Caymus’s 2020 Cabernet Sauvignon ($160): “Concord grape juice and vodka, you know what this is.”

- Volpaia’s 2019 Chianti Classico ($65): “this wine has no right to be so good for so cheap.”

- And, lastly, Tommasi’s 2017 Amarone della Valpolicella Classico ($130): “full-bodied, juicy, complex, delicious.”

Relative to Monteverde, few of Roister’s more descriptive entries actually offer at least three distinct adjectives. (You count the J.J. Prüm, Do Ferreiro, Jermann, Numanthia, and Tommasi as the only examples).

Instead, they fixate on more general terms such as “full-bodied,” “dry,” “lush,” “succulent,” “right amount of oak,” “elegant,” “no new oak” (technically an expository note), “oyster wine,” “light and elegant,” “essence of the Sonoma Coast,” and “so good” alongside certain consequential growing or technical aspects like “aging on the lees,” “flint,” “mountain vineyards,” and “cool climate” (that also may be labeled expository but are imbued with certain descriptive properties). Surely, this information is better than nothing. However, it only really proves useful when a customer is choosing between wines in the same category (light vs. full-bodied Pinot Gris, dry vs. off-dry Riesling, oaked vs. unoaked Chardonnay).

You find that “point-chasing (and scoring)” to be an amusing and surprisingly evocative descriptive phrase (referencing the Michel Rolland-style formulation of certain critically lauded—or “Parkerized”—wines). But a few of these entries actually gall you.

First, the note appended to Groth’s 2021 Sauvignon Blanc—“gotta love a wine called ‘lush’ and ‘succulent’!”—seems to be rooted in secondhand information. Whoever “called” the wine those things—a critic? the producer? the distributor?—is unclear, and it seems unethical for a restaurant to use marketing copy (rather than their own interpretation and attestation) to hawk a bottle to its guests. If Roister is unable to taste the wine (and describe it) or provide some meaningful exposition as a substitute, providing no note at all would be better.

Second, describing Domaine Huet’s 2019 “Le Haut-Lieu” as “peak Chenin Blanc,” in a section already devoted to the grape, seems vapid. The annotation neither glorifies the estate nor describes the wine in any way. It may charm those who already recognize the wine and plan to order it, but—if those who are versed in vinous matters form the target audience—why debase the wine list with such notes to begin with? Describing something as “peak” (or the “greatest,” in essence) is empty praise considering that all the bottles offered should tacitly be endorsed—like the list’s other Chenin Blanc that costs only $20 less.

Third, and most egregiously, you take umbrage with the description of Caymus’s 2020 Cabernet Sauvignon as “Concord grape juice and vodka, you know what this is.” Certainly, this producer’s extracted style is not for everyone. It is, among oenophiles, fair game to make fun of a wine that proudly subverts the sense of restraint and terroir expression than many come to prize. However, a restaurant selling a bottle for $160 should not, at the same time, disparage it. Comparing the Caymus to a grape juice-spiked grain spirit may seem cheeky to insiders, but it is degrading to customers who, in good faith, want to order it. Roister should pay those guests more respect or—if it does look down on the wine to such a degree—cease to offer it and forgo the lucre its sale brings.

Just as Galit and Monteverde’s annotation practices reflect some sense of the restaurants’ identity, you think this Caymus note encapsulates the inescapable smarminess that taints everything The Alinea Group does. They would rather insult you (while taking your money) than stand on any sort of principle or act on their disdain by finding something better (and equally appealing) for this class of drinker.

At the very least, these three examples are nominally descriptive. Nonetheless, you count a baker’s dozen of notes that amount to little more than filler (and not Galit’s playful kind):

- Schramsberg’s 2018 Blanc de Noirs ($98): “classic American bubbles that never disappoint.”

- Egly-Ouriet’s Brut Tradition ($195): “grower champy that we really love.”

- Krug’s Grande Cuvée ($295): “when TAG throws a party we tend to pour Krug.”

- Le Monde’s 2020 Pinot Grigio ($45): “a killer glass of wine for the price.”

- Brooks’s 2019 Riesling ($65): “nobody loves Riesling in Oregon as much as Brooks.”

- Vincent Carême’s 2019 “Spring” Vouvray ($65): “‘Chenin is his gift to the world’ —Jancis Robinson, MW.”

- Kistler’s 2019 “Les Noisetiers” ($125): “the cult Chard that deserves its reputation.”

- Benjamin Leroux’s 2018 Meursault ‘Les Vireuils’ ($148): “‘one of, if not the, most gifted young winemakers in all of Burgundy’ —Allen Meadows”

- Château Miraval’s 2021 rosé ($60): “if you primarily buy wine by the look of the bottle & label you can do no better.”

- Sinskey’s 2021 “Vin Gris” ($78): “one of the most beautiful rosés to come from California each year.” (Recall Monteverde’s annotation for the same wine: “provence-esque from a cult california producer”).

- Anthill Farms’s 2018 “Peters Vineyard” ($110): “one of the best US small single vineyard producers, in our opinion.”

- Sinegal’s 2019 Cabernet Sauvignon ($90): “classic Napa style, Alinea pours this by the glass.”

- Renato Ratti’s 2016 “Rocche dell’Annunziata” ($232): “good enough for James Suckling, good enough for me.”

- Dal Forno Romano’s 2010 Amarone della Valpolicella ($465): “this wine needs no introduction.”

Starting off, terms and phrases like “classic,” “never disappoint,” “we really love,” “killer for the price,” “cult,” “deserves its reputation,” “one of the most beautiful,” and “one of the best” communicate nothing. These entries serve to assure readers that the respective wines are, essentially, “good.” However, as you have previously stated, a good wine program should operate in such a way that you can take for granted that every bottle has been thoughtfully curated (and is, in effect, “good”).

Next, while you appreciate the restraint shown by not associating Château Miraval with its celebrity owners, referencing those consumers who “primarily buy wine by the look of the bottle & label” almost seems cut from the same cloth as the Caymus comment. Given that “the reality is that big box grocery stores and supermarkets make up the largest share of wine sales in the U.S.,” it is safe to say that some sizable percentage shoppers decide on a bottle by way of its aesthetic properties. They come to restaurants—hopefully—to transcend their usual habits and discover something new. Those who favor Miraval are already sure to buy it, so why reduce the wine to its look and label (which, in your opinion, are not particularly noteworthy) when, descriptively, the list could offer a teaching moment? Considering none of the three rosés Roister offers are adequately described, you feel like the entire section is a bit of a failure.

Other statements—like “nobody loves Riesling in Oregon as much as Brooks” and “‘Chenin is his gift to the world’ —Jancis Robinson, MW”—are similarly devoid of meaning. The latter note joins “‘one of, if not the, most gifted young winemakers in all of Burgundy’ —Allen Meadows” in featuring a quote from a popular wine critic. While you respect Jancis Robison quite a bit (Meadows less so), deferring to their judgment represents something of an abdication of the restaurant’s duty to stand behind its own selections. These mouthpieces, though valuable as consumer resources, make the wine list feel impersonal.

(And “good enough for James Suckling, good enough for me,” quite frankly, is insulting given the critic is viewed as a laughingstock in the wine world on account of his prolific score inflation).

While appealing to critical authority is certainly tacky, “when TAG throws a party we tend to pour Krug” and “classic Napa style, Alinea pours this by the glass” seem just as bad. Invoking the name of the mothership—or drawing on the “taste” of wider group—amounts to little more than a fancy way of saying “trust us.” Yet, given the company’s consistent privileging of style over substance (not to mention that abortive wine dinner series), you are not sure they have earned that trust. These notes come across as smug and a bit silly when selling a $300 Champagne. Why not explain that the 169th of Grande Cuvée is made up 146 wines spanning 11 vintages between 2013 and 2000?

Lastly, “this wine needs no introduction” strikes you as simply lazy. Dal Forno Romano’s Amarones are typically foreboding wines, and customers being asked to pay $465 surely deserve some clearer picture of what they’re drinking and why it’s special. (Of course, you do not think anyone would whimsically drop that kind of money on an unknown wine). But, given how hard the producer is pushed by importer Wilson Daniels, the entry reads like an invocation of a lofty reputation that—in your opinion—has not quite been earned. The appassimento technique (used to dry the grapes for the wine) is more interesting in its own right and helps explain Amarone’s concentration of flavor.

Ultimately, in terms of sheer scope, Roister’s annotations seem superior to Galit’s. More of the list is covered with more exposition and more description. Nonetheless, plenty of Roister’s entries are garbage, offering shallow “filler” information, hackneyed adjectives, and appeals to outside authorities that amount to cynical salesmanship. None of these are quite non-sequiturs in Galit’s style. But they feel soulless and at least one of them is insulting.

Relative to Monteverde’s wine list, Roister’s can be commended for its conciseness. That’s about it. While the former privileges purely descriptive notes, it also tells intriguing stories and offers a range of highly effective expository + descriptive hybrids that contain the best of both worlds. Roister, by comparison, appends bland information or a couple generic adjectives to most of their wines. There are a few bright spots, but none measure up to the flowing expository and descriptive notes seen at Monteverde. Few, in truth, can even muster up the three adjectives that Grueneberg’s restaurant delivers across quite a bit of its list.

It is still probably a good thing that Roister has adopted the annotation practice. Yet the uninspired results—and noxious attitude that oozes from certain entries—reinforces that The Alinea Group does not measure up to its lofty opinion of itself (and even falls short of its peers despite the perpetual plaudits). (Well, not exactly perpetual—kudos to Mr. Kessler).

Based on your analysis of Roister’s annotated wine list, you feel the hierarchy of the entries you have constructed generally holds true: expository + descriptive (best), purely descriptive, descriptive via comparison, purely expository, non-sequitur (worst). However, you would probably introduce a category for vaguely descriptive notes (“killer,” “cult,” “one of the best”) that are less useful than description via comparison but probably equal to purely expository notes that confound the uninitiated reader. You may also introduce a category for annotations that tacitly insult certain kinds of imbibers, but it doesn’t take a sommelier pin to know that’s even worse than a non-sequitur.

For your last set of examples, you turn to a restaurant group that has won you over with the sense of romance and nostalgia they are able to conjure across their properties. This kind of character, perhaps, makes the presence of an annotated wine list—something you have never associated with archetypically “classic” expressions of dining—seem anachronistic. But, in practice, this group has found a way to gently guide consumers towards the right wine without spilling too much ink.

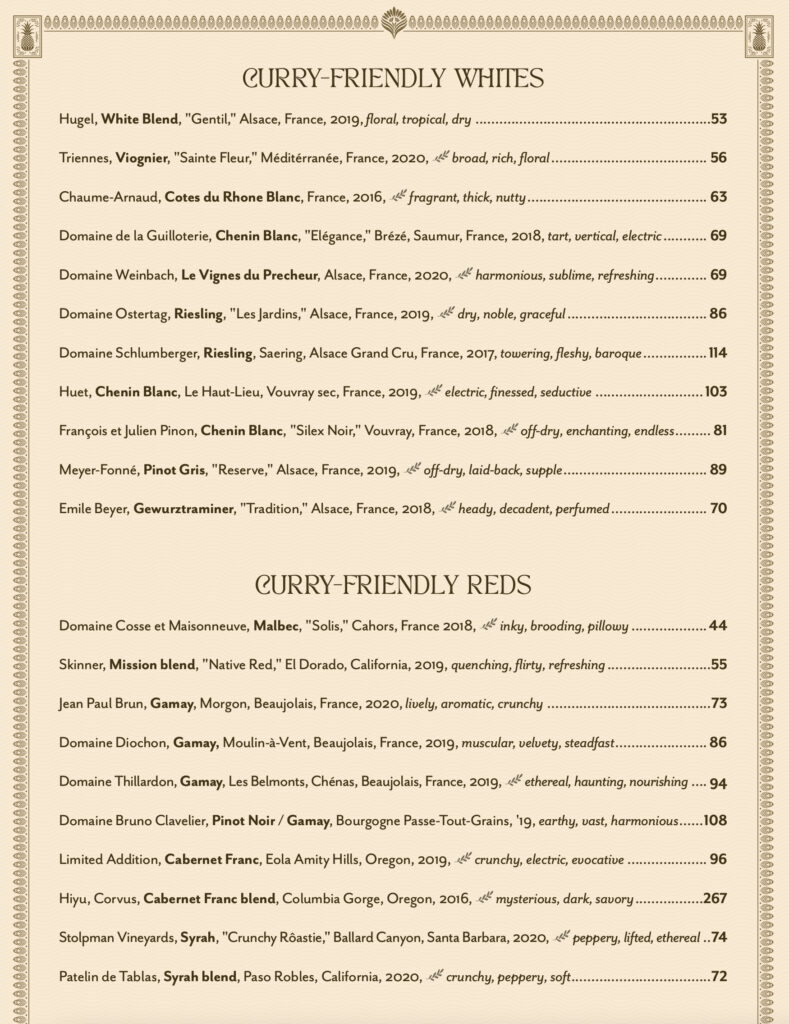

Hogsalt, as best as you can tell, starting annotating its wine lists some time over the past few years. Galit, you think, might have done so first, but Sodikoff’s group adopted the practice before it spread to Monteverde and Roister. Today, it can be seen across the lists at Bavette’s, Gilt Bar, Ciccio Mio, Trivoli Tavern, Armitage Alehouse, and Leña Brava (where it forms one of few telltales regarding Hogsalt’s post-Bayless partnership in the concept). It even features across Hogsalt’s NYC properties like 4 Charles Prime Rib and the newly opened Monkey Bar.

The group’s approach to annotation is rather simple: the practice is comprehensively applied to every bottle (including by-the-glass selections) on the list, and it comprises no more than five words divided among three descriptors. As a bonus, a tiny leaf symbol denotes “organic, biodynamic, or low sulfites.” But that’s it.

Given that Hogsalt’s annotation practice is consistently applied across the mentioned restaurants, you will pull the most interesting examples from across their range of Chicago locations. Likewise, given that these particular notes are nothing more than combinations of adjectives, there is little need to archivally capture the data as you would for more singular expository content. Truth be told, the formatting of Hogsalt’s websites stymies your ability to do so even if you wanted to. (Nonetheless, current copies of the wine lists for Bavette’s, Gilt Bar, Ciccio Mio, Trivoli Tavern, Armitage Alehouse, and Leña Brava can be accessed by clicking on their respective links).

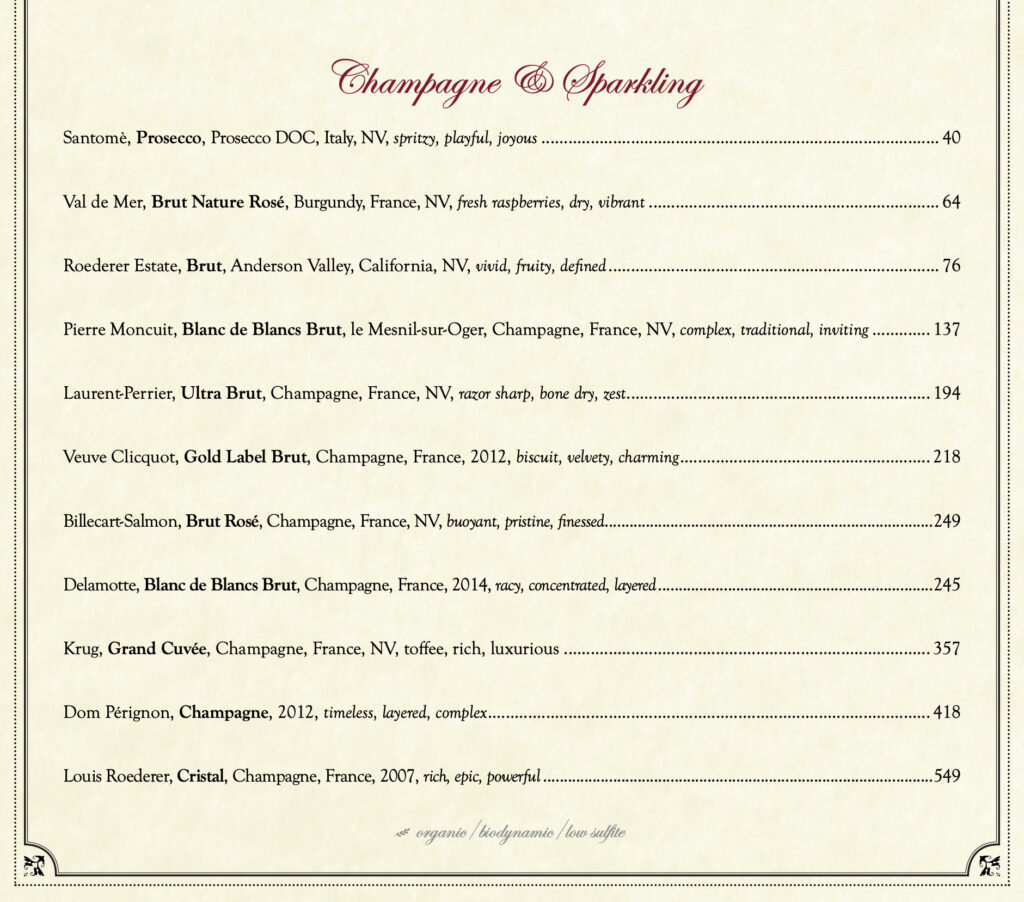

Starting off, you will look at a tranche of sparkles:

- A Santomè Prosecco ($40) is “spritzy, playful, joyous.”

- Casa de Piedra’s “Espuma de Piedra” Blanc de Blancs ($61) is “brioche, green apple, juicy.”

- While Casa de Piedra’s “Espuma de Piedra” Blanc de Noirs ($61) is “tropical, balanced, bubbly.”

- Jean-Paul Brun’s “FRV100” ($62) is “semi-sweet, joyous, natural.”

- Raventós i Blanc’s “De Nit” rosé ($64) is “voluminous, textured, matte.”

- Illinois Sparkling Wine Co.’s rosé ($81) is “dry, cloudy, peach-rings.”

- Ca’ del Bosco’s Franciacorta ($122) is “champagne-esque, traditional sparkler.”

- Vouette et Sorbée’s “Blanc d’Argile” ($182) is “massive, oystery, Chablisienne.”

- Laurent-Perrier’s “Ultra Brut” ($194) is “razor sharp, bone dry, zest.”

- Krug’s Grand Cuvée ($357) is “toffee, rich, luxurious.”

- Dom Pérignon’s 2012 ($418) is “timeless, layered, complex.”

- Lastly, both the 2007 ($497) and 2008 ($549) Cristal are described as “rich, epic, powerful.” (And, just for fun, the magnums of 1996 Cristal offered at 4 Charles and Monkey Bar are also termed—you guessed it—“rich, epic, powerful”).

Right off the bat, you quite like how evocative so many of the adjectives used in these purely descriptive annotations are. Words like “playful,” “joyous,” “luxurious,” “timeless,” and even “epic” penetrate beyond the realm of aroma and palate, putting forth a characterization that conjures the kind of emotions that even a wine acolyte can share in. These terms are balanced by more conventional flavor descriptors like “brioche,” “green apple,” “tropical,” “peach-rings” (a particular favorite), “oystery,” “zest,” and “toffee” that can be more plainly interpreted.

Other words, like “spritzy,” “juicy,” “balanced,” “bubbly,” “semi-sweet,” “natural,” “voluminous,” “textured,” “dry,” “massive,” “razor sharp,” “bone dry,” “rich,” “layered,” and “complex” paint a more overarching picture of the wine’s technical properties or overall sensation. (Though you would note that the term “natural” need not be written if the leaf icon for biodynamic, organic, and low-sulfite bottles is utilized). Meanwhile, terms like “matte” (another favorite of yours) and “cloudy” encompass the bottles’ visual (and, in the latter’s case, textural) aspects.

Describing the Franciacorta as “champagne-esque, traditional sparkler” technically qualifies as description by comparison. It is reminiscent of Monteverde’s annotation of “Italy’s answer to Champagne. buttery brioche & ripe pears” for their own Franciacorta. And it lacks, surprisingly, any more useful adjectives (instead opting for the relatively meaningless “traditional”). However, given that you have only found one other incidence of description by comparison across the Hogsalt lists, it is a fair conceit to term a more affordable bottle of sparkling as “champagne-esque” given that mainstream consumers are likely looking for just that.

Similarly, you think “Chablisienne,” while an astute and multifaceted term, is a bit jargony when considering the annotations are meant to principally guide less experienced customers. Nonetheless, you like seeing it applied to something like Champagne and think words like “massive” and “oystery” help paint a broader, more legible picture.

Of course, labeling several different vintages of Cristal in the same exact way smacks of formulation, yet only people who happen upon several Hogsalt lists will ever note the parallel. It may be fair to consistently term the wine “rich, epic, powerful” when compared to peers like Krug and Dom Pérignon. But those three adjectives, in truth, do not do much heavy lifting in actually defining the wine. Paying more respective to vintage variation could yield more interesting and specific notes. However, you understand that popping one of each bottle for the mere sake of writing a unique annotation is likely cost prohibitive.

Shifting towards the white wines, you encounter more examples that tickle your fancy:

- Weinbach’s 2020 “Le Vignes du Precheur” ($69) is “harmonious, sublime, refreshing.”

- Chéreau Carré’s 2016 “Comte Leloup du Chasseloir” ($72) is “oystery, evocative, dramatic.”

- The 2019 Sinegal Estate Sauvignon Blanc ($75) is “bordelaise, stylish, intense.”

- LVNAE’s 2020 “Etichetta Grigia” ($84) is “aromatic, salty basil, amalfi lemon.”

- The 2021 Cloudy Bay Sauvignon Blanc ($86) is “crunchy, tart, herbal.”

- Garofoli’s 2019 “Podium” ($89) is “fruity, herbal, rollercoaster.”

- Huet’s 2019 “Le Haut-Lieu” sec ($103) is “electric, finessed, seductive.”

- The 2019 Henri Boillot Bourgogne Blanc ($103) is “taut, flinty, zen.”

- Massican’s 2020 “Annia” ($105) is “weightless, pearlescent, pristine.”

- Hiyu’s “Atavus V” ($116) is “solera, perpetual, dynamic.”

- The 2020 Rombauer Chardonnay ($123) is “creamy, oaky, decadent.”

- Keller’s 2020 “Von der Fels” ($135) is “powerful, dry, scintillating.”

- Defaix’s 2005 “Côte de Léchet” ($174) is “broad, chalky, mushroom.”

- The 2012 “Nychteri” from Domaine Sigalas ($198) is “heady, towering, baroque.”

- Vocoret’s 2019 “Les Forêts” ($146) is “enticing, subtle, savory.”

- Ramonet’s 2015 “Champs-Canet” ($396) is “elegant, expressive, regal.”

- Lastly, Leflaive’s 2019 “Clavoillon” ($689) is “imploded, shimmering, introspective.”

Once more, you are immediately struck by the more expressive terms: “sublime,” “evocative,” “dramatic,” “stylish,” “rollercoaster,” “electric,” “seductive,” “pearlescent,” “decadent,” “scintillating,” “towering,” “enticing,” “regal,” and “shimmering.”

But there are straightforward, practical descriptors paired with them, like “refreshing,” intense,” “aromatic,” “tart,” “herbal,” “fruity,” “flinty,” “taut,” “weightless,” “creamy,” “oaky,” “powerful,” “dry,” “broad,” “chalky,” “heady,” and “savory.” This includes some more specific notes—like “oystery,” “salty basil,” “amalfi lemon,” and “mushroom”—alongside wine jargon like “harmonious,” “bordelaise,” “crunchy,” “finessed,” “pristine,” and “solera.” Terms like Bordelaise or solera, which might be unfamiliar to some readers, are balanced by companion words like “intense” and “perpetual” respectively. “Crunchy,” however—which often refers to a spritzy or carbonic character in certain wines—could prove confusing (though will not likely stand in the way of Cloudy Bay’s many fans).

You are most intrigued by the words “zen,” “baroque,” “imploded,” and “introspective” since they seem particularly dense with meaning. The first word, applied to a Bourgogne Blanc, seems to signal an ease, sureness, and sense of balance. The second, appended to an Assyrtiko, would seem to communicate a certain degree of ornateness whose fine details contrast the wine’s “heady,” “towering” characteristics.

The third and fourth terms are both used to describe a young wine from one of Leflaive’s premier cru vineyards in Puligny-Montrachet. While “introspective” would seem to imply a brooding quality, “imploded” points to a certain degree of inward collapse. When considering the third word of the bunch, “shimmering,” the annotation amounts to describing an immediately (if somewhat superficially) appealing white that, nonetheless, contains a massive inner core of complexity that is not yet ready to express itself. This note gently warns readers that the $689 bottle may not show its best without steering those who may be interested away.

You would also, before moving on, like to praise the description of the Rombauer Chardonnay as “creamy, oaky, decadent.” Though this producer may be maligned just as much as Caymus, Hogsalt resists casting it with any sort of disrespect. Rather, you think the annotation faithfully captures what the brand’s fans like about it. At the same time, readers who may not like this style are clearly forewarned.

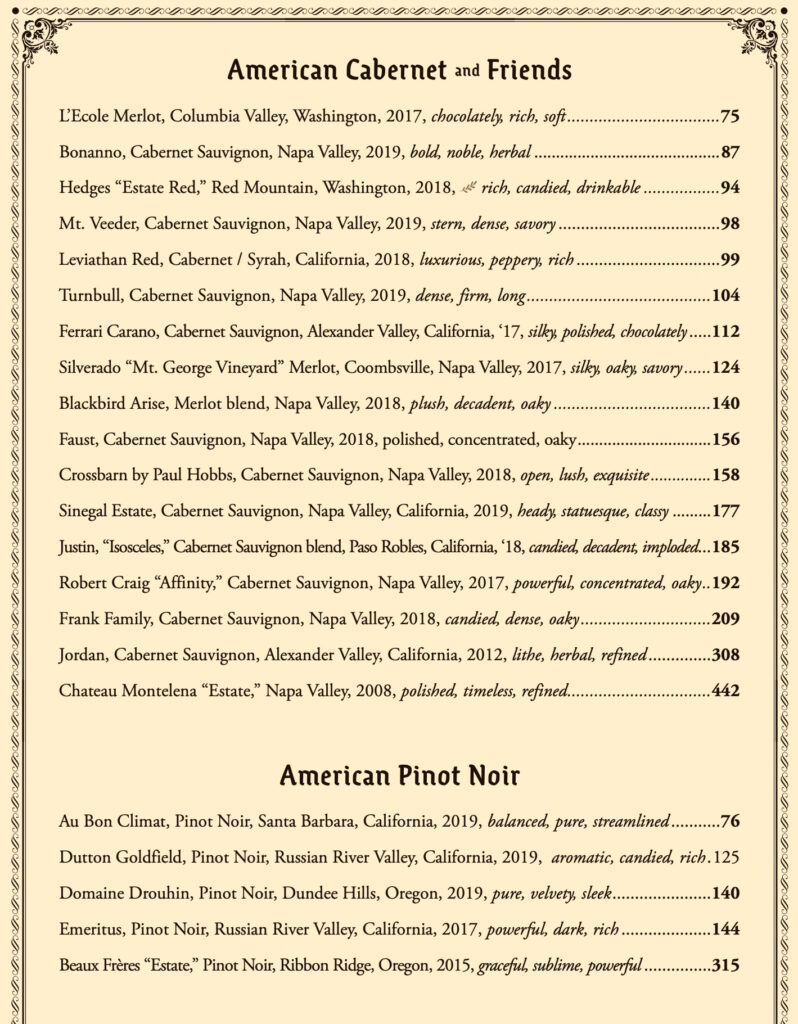

Drawing things to a close, your last set of examples comes from Hogsalt’s selection of red wines:

- The 2021 Pala “i Fiori” ($56) is termed the “châteauneuf of sardegna.”

- Milziade Antano’s 2016 Sangiovese/Sagrantino blend ($72) is “massive, imploded, hulking.”

- The 2018 Châteauneuf-du-Pape from Jean Royer ($118) is “traditional, elegant, twizzlers.”

- A 2018 Clos du Caillou “Tradition” Châteauneuf-du-Pape ($122) is “beguiling, suave, pinot-esque.”

- Alessandria’s 2017 Barolo ($123) is “graceful, ethereal, accessible.”

- Tommaso Bussola’s 2016 Corvina blend ($173) is “boozy, candied, flashy.”

- The 2018 Justin “Isosceles” ($185) is “candied, decadent, imploded.”

- White Rock’s 2018 Cabernet Sauvignon ($190) is “plump, masculine, dark cherry.”

- The 2017 Humbert Frères Gevrey-Chambertin ($223) is “open, pliant, seductive.”

- Cakebread’s 2019 Cabernet Sauvignon ($238) is “mocha, graphite, sweet tobacco.”

- Kosta Browne’s 2017 “Gap’s Crown” ($345) is “expansive, charming, silky.”

- Quilceda Creek’s 2015 Cabernet Sauvignon ($489) is “kaleidoscopic, heady, seamless.”

- Sine Qua Non’s 2012 “Stein” Grenache ($499) is “flamboyant, carnal, ostentatious.”

- Sine Qua Non’s 2013 Syrah ($519) is “flamboyant, carnal, ostentatious.”

- The 2001 Château Rauzan-Ségla ($569) is “vigorous, mentholated, sublime.”

- Château de La Tour’s 2013 Clos Vougeot Vieilles Vignes ($598) is “transcendent, ethereal, seductive.”

- The 2009 Château Cos d’Estournel ($674) is “imploded, decadent, massive.”

- The 2003 Jaboulet “La Chapelle” ($756) is “feral, peppery, brothy.”

- Dujac’s 2011 Vosne-Romanée “Aux Malconsorts” ($1258) is “savory, mysterious, beguiling.”

- Finally, Bond’s 2012 “St. Eden” ($1298) is “statuesque, graceful, compelling.”

Yet again, there is a panoply of personifying words leading the charge: “hulking,” “suave,” “flashy,” “decadent,” “pliant,” “seductive,” “charming,” “flamboyant,” “ostentatious,” “sublime,” “transcendent,” “mysterious,” “beguiling,” “statuesque,” and “compelling.” There is also, once more, an assortment of more familiar (if still slightly affected) wine descriptors such as “massive,” “boozy,” “candied,” “plump,” “expansive,” “silky,” “kaleidoscopic,” “seamless,” “heady,” “vigorous,” “ethereal,” “feral,” and “savory.”

Added to that, you have ordinary flavors like “dark cherry,” “mocha,” “graphite,” “sweet tobacco,” “mentholated,” “peppery,” and “brothy.” Of these, the association of a Châteauneuf-du-Pape with “twizzlers” strikes you as the most playful (and reminiscent of the “peach-rings” note applied to one of the lists’ sparkling wines). While decidedly lowbrow, these references to popular candies negate the need to write both “candied” and the name of the evoked fruit. On top of that, they naturally tap into a shared nostalgia that—because these references are not overdone—helps to bring guests’ perception of the selection (with all its expensive bottles) back down to earth without trivializing it.

When it comes to red wines, you find terms like “accessible” and “open” to be key in ensuring that guests do not end up with something tannic to the point of inhibiting pleasure. Likewise, you may add words like “graceful,” “ethereal,” “flashy,” “pliant,” “expansive,” “charming,” “silky,” “carnal,” “seamless,” and “flamboyant” to this category; however, these terms may relate more to the relative textural quality of a wine rather than its suitability for immediate drinking.

Also, you must admit that bottles described as “graceful, ethereal, accessible,” “open, pliant, seductive,” or “transcendent, ethereal, seductive” feel redundant and almost tautological. Some guests may know to expect cherry notes from Nebbiolo and Pinot Noir—some may very well privilege that a wine feels “light” above all else—but the repetition of near-synonyms that do little to enrich meaning is one of the few places where these Hogsalt annotations border on pretension. You do not see why some aspect of these selections’ fruit, earth, or mineral qualities could not be remarked upon.

Opposite “accessible” and “open” you find that unique term “imploded” being applied to blends made from Sangiovese/Sagrantino (the Milziade Antano) and traditional Bordeaux varieties (the Justin and Cos d’Estournel). In two of these cases, the descriptor is joined by the word “massive.” In two others, “decadent” is added to the mix. (“Hulking” and “candied” are the adjectives left over). Thus, while “imploded” seems to signal a wine that is turned in upon itself, such a bottle can still deliver a lot of pleasure (or “decadence”) even if it does so in a “massive” style that lacks the “graceful” or “elegant” dimension of other offerings. You appreciate how this unique word is elucidated across the various lists, revealing a nuance that goes beyond what might be called “tight” or “closed” otherwise.

Two of the above examples engage in what you have labelled “description by comparison.” The Pala “i Fiori” is termed the “châteauneuf of sardegna” while the Clos du Caillou “Tradition” Châteauneuf-du-Pape is called “pinot-esque.” The former is made from Cannonau—the Sardinian name for Grenache—making the Châteauneuf comparison apt. Additionally, this wine is offered by-the-glass, meaning that servers should be adept at describing what qualities cause the resemblance. Nonetheless, given that the other glass pours benefit from more familiar sets of adjectives, it seems right to question if “châteauneuf of sardegna” goes over some readers’ heads and sends them scurrying towards one of the other seven, more legible options.

The “pinot-esque” Clos du Caillou, by comparison, is also called “beguiling” and “suave.” These other words seem to echo Pinot Noir’s characteristic elegance—especially relative to Châteauneuf-du-Pape—without adding much by way of specifics. Still, given Pinot’s domestic popularity—relative to Rhône—you think the comparison may be successful in leading novice drinkers towards something new. Nonetheless, one (or both) of “beguiling” and “suave” would be better exchanged for some alternate, divergent description.