Just when you thought you were out—of Italian and Italian-American restaurants to talk about—they pull you back in!

Nearly half a year ago, Adalina and Alla Vita appeared as forthcoming restaurants in your article orienting Chicago’s next-gen “Italian-Italian” and Italian-American restaurants with regard to how they approach tradition. Both establishments have now been open for some time—five months in the case of the former and two months for the latter. But, by the time Alla Vita finally debuted, BRG’s cash grab had gained yet another competitor within its crowded genre.

Elina’s quietly opened a couple blocks west of D’Amato’s Bakery in early September, touting two chef-owners with mouthwatering credentials. Ian Rusnak cooked at Blackbird, NoMI, Restaurant Marc Forgione, Carbone, and ZZ’s Clam Bar before going on to open 4 Charles Prime Rib and Bavette’s (presumably the more recent Las Vegas location) as Culinary Director of Hogsalt. Eric Safin worked as a saucier at Jean-Georges, retained a Michelin star as chef of ZZ’s Clam Bar, and opened The Grill with Mario Carbone and Rich Torrisi before becoming the chef de cuisine of Stephen Starr’s Verōnika.

When it comes to contemporary Italian-American cooking, Carbone and Torrisi’s names loom large. But Forgione is no slouch either, and the experience gained crafting sauces for one of NYC’s finest French restaurants can only shine when applied to pasta. (Heck, you’re certainly a fan of Hogsalt too even though you wish Ciccio Mio would develop its menu).

That is to say, Rusnak and Safin’s experience is formidable. Combining their powers to open an understated little eatery serving “fine Italian cooking” immediately set your tongue wagging. Elina’s, clearly, was not a contrived marketing creation. Rather, it promised to serve as a vehicle for two chefs with a remarkable wealth of experience to draw on in redefining Chicago’s relationship with Italian-American cuisine. There were no promises made—no avalanche of hype—only the potential and freedom to cook beloved dishes their way.

If the forethought required in order to secure a table is any sign, Elina’s has succeeded in capturing the city’s imagination. But, then again, Alla Vita demands would-be guests pounce two months in advance to book a reservation, and Adalina, too, commands quite a long wait list for diners looking to visit during the prime of the weekend.

Placing those venues alongside Monteverde, Rose Mary, and Gibsons Italia—which boast some of the most coveted seats in town to this day—it becomes clear that Chicagoans remain enamored with Italian food. They, perhaps, crave the food more fervently than ever. But is the city close to reaching a critical mass of cucine? Can there ever be enough housemade pasta, parmigiana, and bistecca to sate the palates of a public for whom the red checkered tablecloth forms the bellwether of comfort food?

You, certainly, love Italian cuisine in all of its manifestations and will always be the first to champion Italian-American cookery as deserving of a respect that transcends hackneyed notions of “authenticity.” For both traditions—“Italian-Italian” and Italian-American—evoke their own nostalgias, and the two categories—though they make use of similar ingredients and forms—deserve a chance to express their singular visions without suiting any mistaken guest expectations.

Just as the beauty of China’s regional cuisines remains shrouded by that pernicious, pervasive menu of “Chinese-American” favorites, the shadow cast by Italian-American stalwarts—perfectly engineered to please native palates—stymie any greater appreciation of the cuisine.

However, “appreciation” does not mean saying goodbye to vodka sauce, but understanding where it belongs and demanding that it be made to the same standard as a hallowed ragù modeled after the “old country.” It does not entail a rejection of the familiar dishes one holds dear for want of being “authentic.” Rather, “appreciation” entails the recognition that both genres—“Italian-Italian” and Italian-American—exist, that both have value, and that both can be raised to some superlative expression.

“Appreciation” really means engagement: a knowing embrace of a particular cuisine that empowers a given chef to work within a defined philosophy and, potentially, create something new. The “Italian-Italian” chef, thus, can put their effort towards redefining one set of dishes while the Italian-American addresses their own. Neither of the two, ideally, should need to cater to customers who wish—for reasons of flavor profile or portion size—they were at the opposite establishment. Instead, both should pursue their respective genres with a reckless abandon (rooted, nonetheless, in a deep understanding of its dividing lines). Only then can the essential process of experimentation and repetition be fruitfully pursued to advance new forms of pleasure

Of course, the lines between “Italian-Italian” and Italian-American cannot be so neatly defined. While the former term comprises a range of rich regional cuisines, the latter—as the product of diaspora—must contend with a variety of permutations drawn from the range of cities that laid home to 20th century immigrants. “New York,” “New Jersey,” “Boston,” “Rhode Island,” “Chicago,” and “San Francisco” (to name a few) Italian-American cuisines each have their distinctions. And, while they might not be the kind that define the highest expressions of culinary art, such factors form granules of nostalgia that chefs approaching the “red sauce” canon must contend with.

Thus, while Adalina, Elina’s, and Alla Vita must each be judged against the usual markers of quality, you find an added dimension of “vision” to be quite salient. Each restaurant—however “Italian-Italian” or Italian-American, however traditional or non-traditional (relative to such genres)—must also offer some degree of depth.

For Chicago is drowning in a sea of spaghetti, and it is not enough for any new restaurant to adopt some fancy branding and simply regurgitate what has already been served here for generations. Mind you, this is not an attack on simplicity—on letting the classics speak for themselves—but of big budget concepts playing things safe while cannibalizing the mom and pop eateries that possess a greater claim to such a heritage.

The question is not one of “authenticity,” but of thoughtful engagement with a cuisine whose earliest manifestations—within Chicago—still survive. Do the chefs of Adalina, Elina’s, and Alla Vita take inspiration from the work that has come before them? Do they engage, wholeheartedly, in a creative process that enriches the appreciation of Italian food and its derivations? Do they channel a feeling of love for the nostalgia that anchors the public’s appreciation for such fare even if they deconstruct and reconstruct it beyond recognition?

Or is “Italian food” just an easy vehicle for a contrived, commercial success that dilutes the spirit of “slow food” (or, alternatively, abbondanza) that attracts customers to begin with? Do they treat the food as a fashionable prop, an embalmed array of money-makers in service of mindless consumption? Do they glorify “Italian-Italian” and Italian-American cuisines as living expressions—processes—of culture or mere means to a craven financial end?

In lieu of writing isolated pieces on Adalina, Elina’s, and Alla Vita, you think a comparative piece—given the restaurants’ contemporaneous openings—might better serve to address these questions which underlie the opening of any Italian restaurant in the present era. Though each establishment is specialized enough to avoid being labelled a direct competitor, all three tread the ground of other existing (and sometimes longstanding) concepts. Each, moreover, wages battle within an attention economy that can only abide by so many “hot new restaurants” at a given time.

You cannot expect most consumers to note or care for the factors that distinguish one branch of Italian cooking from the other. But it may be instructive to separate caricatured expressions of the cuisine from those that sincerely mine its history in a bid to do something new. For only the latter works to shape some gastronomic future for the beloved fare by stoking the fire of a philosophy that—by very nature of its entropy—resists the race to the bottom that debates over “authenticity” entail.

Thus, in this series of articles, you will engage Adalina, Elina’s, and Alla Vita sequentially with a particular emphasis on how each approaches the murky concept of “Italian cuisine.” While all three restaurants have enjoyed an early dose of success, earning a place in the pantheon of Chicago’s greatest “red sauce joints” demands more than just playing the hits. Which chefs, if any, have found a way to show diners something new within a genre they know so intimately well? And whose servers, more than any two-bit renovation could ever convey, really live and breath la dolce vita through their manner of hospitality?

Only a dastardly restaurateur could fail to comfort their patrons with recourse to all the riches of Italian fare. The task, as always, is to delight, enthrall, and inspire as only the art of dining—in its most transcendent expressions—can do.

Let us begin.

Adalina

Adalina opened in June, having renovated a space that once belonged to Walton Street Kitchen + Bar. Located at the southern threshold to Chicago’s Gold Coast district, the restaurant is undoubtedly the most luxe of the three new openings discussed herein. It counts an OVO store as its next-door neighbor, the Waldorf Astoria sits across the street, and a collection of the city’s classic upscale haunts just a couple blocks north surrounding Mariano Park (i.e. “The Viagra Triangle”).

In fact, while Adalina might ostensibly compete with Elina’s and Alla Vita within the attention economy (how many “new and exciting” Italian restaurants can one city sustain at a given time?), its real competition includes Gibsons Rush Street, Tavern On Rush, Rosebud Steakhouse, and Maple & Ash alongside out-and-out Italian concepts like Carmine’s and Nico Osteria. Looking further afield (beyond stalwarts like RPM Italian and Formento’s), the restaurant’s fiercest rival would seemingly be Gibsons Italia. However, for good reason, Adalina is not exactly trying to knock Wolf Point’s crown jewel off its perch.

The restaurant is owned and operated by a former Gibsons corporate general manager in partnership with two members of BDG Hospitality. While Adalina does not fall under BDG’s umbrella, that group’s properties—nightlife spots like Bounce Sporting Club and LiqrBox—hint at the blend of perspectives brought to the table by management.

On the culinary side, Adalina is anchored by executive chef Soo Ahn, a Michelin star winner at Band of Bohemia who also touts past experience at Grace, EL Ideas, and Torali—the Chicago Ritz-Carlton’s Italian steakhouse concept.

Head pastry chef Nicole Guini graduated from La Escuela Patagónica de Gastrónomica in Argentina before running the pastry program at Michelin-starred Spiaggia (under chef Sarah Grueneberg). Following that, Guini became the pastry chef of Michelin-starred Blackbird and its sister restaurant Avec, earning the 2019 Jean Banchet Award for Pastry Chef of the Year in recognition for her work.

Rounding things out, chef de cuisine Sam Rosales worked under Sarah Grueneberg at Monteverde, rising to the position of sous chef. Meanwhile, head sommelier Alexandra Thomas brings experience at RPM Italian and Spiaggia to the table.

With such an estimable collection of talent, Adalina could define itself in whatever terms it saw fit. Would it carry the torch for the dearly departed Spiaggia (which, as it happened, permanently closed just a couple weeks after Adalina opened) or aim more principally at its rivals up the street?

The restaurant would ultimately promise “a modern and engaging Italian menu in a timeless yet alluring setting” that strikes “a balance between Northern and Southern cuisine” through “expertly staged shared plates” along with “strong statement items that satisfy a table.” It painted itself as “the ideal venue for a romantic evening, business dinner, or special occasion,” confirming its intentions to compete with the luxurious steakhouses a stone’s throw away.

Philosophically, Ahn shared that he would try to put his “own fun spin” on the menu of “housemade extruded and stuffed pastas, imported meats and cheeses, and hand-selected beef and seafood selections” without straying “too far from the heart of Italian cuisine.”

The dining room would showcase “antique mirrors,” “plush velvets,” and a “custom Italian chandelier made of 150,000 crystals” while the beverage program could claim “400 different bottles of wine at any given time” housed in “an astonishing floor-to-ceiling wine cellar” containing “3,000 bottles of wine and a decanting station.”

Public relations hyperbole aside, Adalina’s intention of joining Chicago’s upper stratum of Italian dining was clear. The restaurant might not be crafting tasting menus, but “various tableside services” would reflect a high expression of hospitality meant to go toe-to-toe with Gibsons Italia and RPM Italian.

At the same time, however, Adalina could rule the roost as far as the Gold Coast was concerned. It would offer a clear step up from Carmine’s and Nico Osteria while focusing more intently on Italian food than Gibsons Rush Street, Tavern On Rush, or Maple & Ash. The restaurant could fulfill the same role that RPM does in River North and that Gibsons Italia does in West Loop—its bar benefitting from a natural flow of neighborhood walk-ins and would-be regulars searching for a refined experience. At the same time, it would only compete directly with those other venues in attracting roving special occasion diners (for whom preference of menu and ambiance might be a purely personal decision).

Do Adalina’s cuisine and service measure up—let alone distinguish themselves—relative to those popular peers? That, perhaps, is another question to consider before orienting the restaurant relative to Elina’s and Alla Vita.

You have visited Adalina five times since its opening. As usual, you will condense the sum of your experiences into one cohesive narrative.

Adalina occupies a stretch of State Street with hardly a restaurant or boutique in sight. Spying the Walgreen’s franchise and elementary school just up the road, you’d be forgiven for thinking the Uber driver let you out on the wrong block. But, looking eastward, you note the side profile of the Waldorf’s imposing façade. And, now that you think of it, the owl logo on the shop next door seems strangely familiar. A half dozen people wait for their turn to enter, and, noting the scene, you realize that Yves, Gianni, Giorgio, and Miuccia’s boutiques lay just one street over.

Yes, Oak Street historically forms the southern boundary of what might be considered the “Gold Coast.” But Adalina—with its second story balcony wrapped along the northern and eastern sides of the luxury condo building it occupies—aspires to be one of the cool kids. Its sights are trained on the nexus of old money and young women that has made this part of the city infamous. Can it tempt that well-heeled, stilettoed crowd to venture just a bit further? Will it redefine the neighborhood boundary and become a bonafide bedfellow to Gibsons (rather than the Dunkin’, McDonald’s, Taco Bell, Chick-fil-A quadrumvirate that sits only a bit further south).

Adalina’s stylized “A” signage juts out from the wall, ensuring guests who exit further down State do not miss the restaurant’s slightly recessed entrance. There, the underlit awning that once read “Walton Street” (quite a confusing choice in retrospect) now displays the name of the building’s new tenant. The revolving door—another carryover from before—seems fitting. It lends Adalina the gravitas its promotional materials were going for, signaling some sense of the establishment’s scope and scale. This is not a mom and pop Italian endeavor, but a sweeping space pursuing some element of curb appeal.

Pushing inside, you find yourself face to face with the host stand in what is best described as an antechamber. Though the restaurant has announced plans to open a speakeasy on the first floor—its entrance, no doubt, hidden somewhere in plain sight—the entry process, as it stands, feels a bit comical. You provide your reservation name to the host, climb a flight of stairs, and provide it once more at another stand less than a minute later.

Maple & Ash and Gibsons Italia maintain the same sort of system—though the trek to the dining room at those establishments involves waiting on a solitary elevator. Seemingly, this dual check-in process works to better manage the flow of walk-ins and barflies so that guests toting reservations need not battle throngs to reach their table. But you would expect the second host stand to be ready to receive you—preferably with a greeting by name—and whisk your party to its seats posthaste. Gibsons Italia has mastered this process while Adalina—like Maple & Ash—has sometimes required that you wait around awkwardly in an upstairs no man’s land for several minutes despite the trouble of having already signaled your arrival once.

However, if it’s any concession, passing time at the precipice of Adalina’s bar area is not so bad. The gray, black, and dark blue tones that define the space—offset by marble tile, velvet curtains, and polished wood—succeed in establishing a swanky feel. Even the stairway itself, accented with floral light fixtures and a matching mural, works to immediately set the tone.

Climbing those steps, you catch your first peek of Adalina’s cellar. The temperature and humidity controlled room lays adjacent to the upstairs host stand. Free-standing, floor-to-ceiling racks advertise some of the collection’s more eye-catching labels—as do an array of wooden cases and magnums positioned artfully along the floor. But the more traditional set of inlaid wooden racks on the back wall, array of well-stocked mini fridges, and dedicated wine service station speak to the cellar’s practical use. The room does not seek solely to shock and awe but to facilitate Thomas’s work by providing the space and privacy to honor the bottles being sold.

At last, a hostess approaches and leads you on your way. Reaching the dining room means passing by Adalina’s bar—whose patrons, during peak hours, all but block traffic to and fro. High-top seating lines the windows abutting State Street while about a dozen chairs—made from the same plush upholstery—wrap their way around the three-sided counter. Bartenders dressed in white shirts and black vests hold court, their movements framed by two triple-tiered shelves of spirits and a solitary widescreen television. But the best view of the bar comes from afar, where you can appreciate the subtle curvature of the ceiling.

Between the counter seating and the high-tops, a pair of shimmering pillars bedecked with silver and gold paint divide the room. The attached sconces cast their glow throughout the room while a small amount of surface area allows customers lacking any seating to set their drinks down. But what really tickle your fancy are the two back-to-back banquettes fitted into the gap between the pillars. They sit at the very middle of all the action while—by virtue of sitting low to the ground—not stymying the room’s sense of energy.

Moving onward, a more subdued looking pillar marks the threshold of the dining room. From it, a half wall extends parallel to the side of the bar. This feature, too, provides the area with more banquette seating and a couple additional high-tops. It allows Adalina to maximize the potential of attracting a nightlife crowd that might only incidentally end up eating. You have noted that these patrons can make maneuvering to your table difficult, the lend the restaurant an attractive sense of excitement. For diners remain insulated from the sounds and sights of the drinking crowd while, on occasion, getting a glimpse of the spectacle. Such a dynamic makes their well-appointed table feel even more luxurious, the reservation they made in advance even more coveted. This emotional dimension to the experience succeeds primarily at a spatial level.

At last, the hostess deposits your party at its particular table—in this case, a lovely half banquette at the very center of the dining room. White tablecloths abound while that 150,000 crystal centerpiece glitters overhead. The curling shapes of its dangling strands replicate the petals of the floral mural painted onto the ceiling behind it. The backlit painting that dominates the room’s rear wall displays more of an abstract, shattered composition—as do the plush, speckle-patterned chairs. But their bluish tones, offset by dark wooden flooring, complement the crystal-floral showpiece without competing for attention. (Smartly, they resist overdoing the botanic theme).

Glowing archways located behind that prominent abstract painting lend the work an added element of scale. In fact, with candles on the table and additional sconces placed throughout the dining room, you must admit that Adalina’s makes masterful use of lighting. The restaurant bathes its patrons in the kind of soft, indirect lighting that makes even the ugliest of ducklings look positively glamorous. Meanwhile, careful management of shadows and sightlines help prevent any undue amount of people-watching. The space does get dark enough to complement the adjacent bar scene; however, one never struggles to see what is placed on the table or to move about the room.

Further, while the best seats in the house undoubtedly enjoy the view (along with the natural lighting) drawn from the windows facing out onto State or Walton, each and every table will be pleased by the dining room’s jewel box design. The space feels centered and teeming with life. It feels like somewhere without approaching such a scale as to feel corporate or concocted. Aesthetically, you think Adalina fulfills its “special occasion” moniker at least as well as Maple & Ash. Both restaurants may lack the natural advantage of Gibsons Italia’s showstopping view, but the former benefits by avoiding the latter’s composite design. For it feels nice to sit in Maple & Ash’s atrium but a bit anonymous to be placed at one of the majority of tables that span its perimeter. Adalina offers only one, grand room that ensures each party feels they’ve been given pride of place.

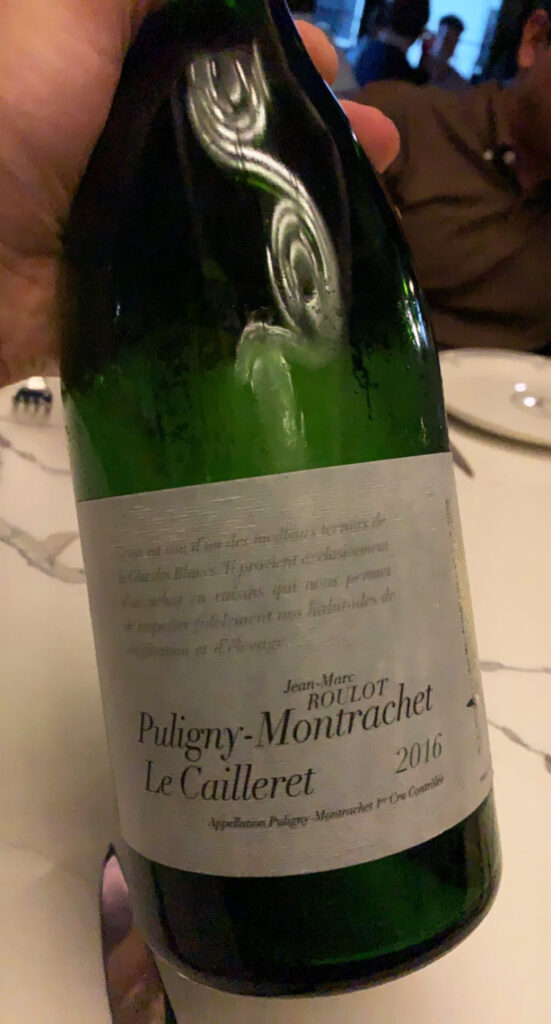

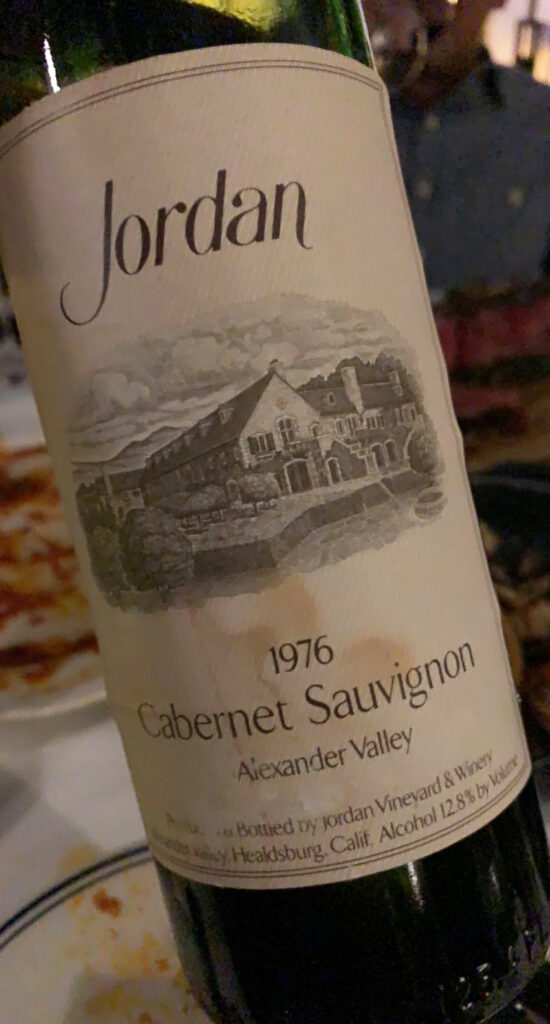

Taking your seat, you immediately turn your attention to Thomas’s wine list. Walking past Adalina’s cellar piqued your interest—all the more because the selection cannot be browsed online. New openings such as Esmé—where mass market wines from Rombauer and The Prisoner formed the top end of their offerings—have somewhat killed your faith in Chicago’s capacity for wine appreciation. Establishments have come to view vinous delights as little more than a prop with which to conjure a shallow sense of luxury. They show no shame peddling anonymous, current release wines at a two- or three-times markup—bottles that even the most clueless Binny’s customer could select for themself.

Yes, the premium paid for wine in restaurants is meant to reward the practice of proper service. But the question must be asked: why bother going through all the song and dance just to receive the same swill you guzzle at home in your underwear? Past the point of offering reliable by-the-glass or so-called “house wine” options, a restaurant’s program becomes less about peddling beverages and more an expression of its distinct personality. The customer, in addition to glassware, decanting, and pouring, is paying for thoughtful curation and careful cellaring. They trade away the greater value of drinking at home for the sake of appreciating a bottle that honors the establishment’s fare and fulfills that eternal bond between vintner and chef. For, on those rare magical evenings, food and drink combine transcendently to honor nature.

Steakhouses, certainly, have remained a haven for wine appreciation. Gibsons Italia, Maple & Ash, and the RPMs boast some of the city’s deepest selections. They might extract a pretty penny from undiscerning cult Cab drinkers, but the restaurants’ lists—due to their scope—allow for some largesse (provided the customer knows how to recognize the bottles whose prices have not kept pace with wine’s skyrocketing secondary market). As it happens, you can actually enjoy many bottles that—even allowing for their original markup—are cheaper than the going rate on wine-searcher. That feeling, when the occasion strikes, is a lot like unearthing buried treasure.

Of course, such an occurrence is unique to restaurants that have collected bottles long enough to see their prices appreciate. Or, at the very least, it demands that an establishment have access to coveted allocations for wines whose limited nature ensures their pricing explodes by the time they reach the wider public. In this manner, restaurants’ wholesale purchasing—even if they take a healthy premium on the price passed onto the consumer—may still reward oenophiles. Wine directors who are particularly adept may build collections that solidify their restaurants’ reputations as drinking destinations well into the future (such is the case with Andrew Algren’s work at Cherry Circle Room and Arthur Hon’s at Sepia). With a well-managed program, everyone is made whole—save for would-be speculators.

A new restaurant—particularly facing today’s conditions—might not want to saddle themselves with case after case of expensive vino. Surely, you can understand Esmé’s interest in simply opening their doors and securing some reputation based upon the artistry of their cuisine. But Adalina, slinging slabs of red meat within a more traditional genre of cookery and proclaiming its suitability as a “special occasion” restaurant, needs the kind of bottle list that will impress. However, faced with building a list from scratch, what can they do to compete with the established steakhouse players?

One of Adalina’s partners went to auction, ensuring his selection could boast at least some small selection of well-aged offerings. He also used longstanding contacts from his time with Gibsons to bring an array of library releases from popular domestic wineries onto the list.

Thus, while Thomas’s list remains nascent in many respects (for how could it not?), there is indeed value and immediate pleasure to be had. You have enjoyed a 2018 Guiberteau Brézé for just $76 (the 2016 vintage costs $180 at Boka), the 2020 Domaine Tempier rosé for $95, 1990s Barolo from Oddero and early 2000s Cabernet from Dalla Valle in the $300 range, and a superlative bottle of 1976 Jordan (the winery’s inaugural vintage) for a little over $400.

Certain sections of the list—like white and red Burgundy—will need more time to develop. Likewise, some of the usual steakhouse suspects—like Dana Estates and Hundred Acre—demand their typical premium. But the restaurant’s list boasts impressive breadth for a newcomer, and there are pockets of value awaiting those willing to venture away from the most hallowed names. Personally, the prospect of drinking any kind of moderately aged red wine at only a one and a half to two-times markup makes your mouth water. The fact that you can actually get Barolo and Napa Cab at such a value is laudable. Such offerings are sure to go quickly; however, Adalina’s wine program—even in this early stage—has demonstrated an aptitude at sourcing attractive bottles and offering them at a fair price.

This feather in the restaurant’s cap reflects an engagement with wine sourcing that looks beyond the standard, most convenient distribution channels. Likewise, it speaks to a business model that does not depend on squeezing oenophiles for revenue. Adalina deserves credit for debuting a list that drinkers can get excited about ordering from. All the more, Thomas’s tableside manner and service technique have been faultless. She is well-positioned to immediately deliver an exciting array of bottles to her patrons while building a program that, over time, could very well rival those of her more established peers.

By the time you finish picking out a couple bottles, one of Adalina’s bussers has already filled your waters and brought the table a snack. In a booming voice—sprinkled with a soupçon of self-aware charm—he welcomes you all to the restaurant and punctuates the establishment’s gracious embrace of the party by serving small individual plates each containing a crust of bread, a chunk of parmigiano, and a dollop of housemade tomato jam.

You dislike the limp texture of the bread and find the overall serving size to be a bit paltry. The presentation pales in comparison to the version done at Ciccio Mio—where servers ceremoniously offer diners an entire loaf of warm, crusty bread along with freshly-sliced salami, olive oil, and grated cheese. But the tomato jam, you must admit, tastes good, and it is hard to find fault with the gesture. For Ciccio Mio’s dining room feels like a movie set, and the establishment operates on the sort of small scale that allows for a more extravagant opening flourish.

Adalina’s plate of antipasti must instead be compared to RPM—where items like the whole wheat focaccia with whipped ricotta ($14) and truffle garlic bread ($12) demand payment—and Gibsons Italia—where free baskets of rather forgettable pane have recently been substituted for a $9 focaccia (that is also, as it happens, paired with whipped ricotta). Gibsons Rush Street, of course, reliably offers a rather classic, crumbly assortment of raisin, harvest wheat, and Vienna round loaves—gratis. Maple & Ash, meanwhile, only serves bread as an addition to dishes like the steak tartare (grilled sourdough), beef carpaccio (warm brown butter brioche), and meatball (garlic bread).

Yes, the days of unsolicited loaves are indeed waning, but—with notable exceptions such as Aba and Bavette’s—such a change is probably for the best. Wastage is better minimized (especially in the era of “gluten allergies”) while the quality of baking—now being forced to anchor appetizer dishes that can cost nearly $15—must necessarily rise. Further, with restaurants continuing to charge additional service fees on account of the pandemic, it seems fair to limit the prospect of customers gorging themselves on something offered free of charge. (However, you think guests should be entitled to receive additional batches of bread at no charge should there remain some unfinished amount of its accompanying element).

With that in mind, Adalina’s ration of bread, jam, and cheese shines a bit more brightly. The outlay, however meager, becomes magnified considering how many of the restaurant’s peers have abandoned such a nicety. Even if you find the leaven component to be anonymous, the combination of parmigiano and tomato alone is enough to whet appetites. They plant the seed that a heaping portion of veal chop parmigiana—served later in the meal—will ultimately cause to blossom. And—being brandished during the staff’s very first interaction with the table—these little bites work to set the tone.

Bussers in the steakhouse genre (and its Italianate offshoots) have long thrived on being neither seen nor heard. They form the workhorses and tactically deployed support staff that allow the captains, sommeliers, and managerial schmoozers to shine. Every dining experience is built upon the foundation their labor provides, yet their personalities rarely come to the fore. Theirs is usually a mechanical—more than a human—presence, yet Adalina turns this dynamic on its head.

By tasking its bussers with delivering this opening salvo—in contrast to Ciccio Mio’s use of the customer’s actual server—the restaurant makes a powerful statement. Adalina asserts that its hospitality is built from the ground up. Conjuring magical moments is not the sole domaine of the establishment’s best dressed, perfectly coiffured staff. Rather, diners get the sense that the entire organization is empowered to provide excellent service. This conviction flows naturally from the inspired manner in which Adalina’s managing partners happily engage in menial work like clearing tables and refilling drinks. Such leadership by example yields immense rewards at an interpersonal level.

For Adalina’s service culture does not excel simply because employees are comfortable transcending their usual roles at a mechanical level. That equal sense of ownership paves the way for each staff member to infuse every service encounter with an added dimension of soul. The well-dressed servers take the lead, guiding guests through the menu’s format and warmly receiving any and every request. The team strikes you as noticeably younger than those working the floors at the city’s other steakhouses, but they bring an ease and confidence to their interactions that inspires faith even as the restaurant’s dining room reaches its maximum capacity. You never feel besieged by the flurry of activity, remaining transfixed instead by the kind of gentle, deferential mannerisms that undoubtedly signal “luxury.”

But it is the bussers, once more, who impress you most. With the restaurant’s servers—necessarily—predisposed to conduct the formalities of the ordering process, their helpers become familiar touchstones. Beyond their usual duties pouring refills and clearing plates, the bussers can field additional orders, perform tableside preparations, and portion particularly large orders out amongst guests. They not only do so adeptly, but with an added tinge of banter that cultivates a sense of familiarity and amounts to a real sense of charm. The bussers at Adalina are not interchangeable robots. Instead, by displaying genuine presence and enjoyment of their work, these oft-forgotten figures help to define Adalina’s identity. They mark the restaurant with an ingrained, “old school” patina that resists the hollow, if inoffensive, encounters of the corporate hospitality playbook.

With a wink, the busser leaves you to devour the bit of bread, jam, and cheese he deposited. Your stomach grumbles greedily—“was that all?”—and decides it is time to broach the menu.

Compared to the conceptual menu Adalina shared with the media in May of 2021, the restaurant’s opening menu—you must admit—struck you as particularly scarce. Ahn’s entire section of “Crostacei”—which touted items like oysters, jumbo prawns, red king crab, and Maine lobster—was missing. Hot seafood dishes like lobster fritta, mussels au gratin, and dover sole also hadn’t made the cut. Even more concerningly, the nine different pastas that the restaurant advertised had shrunk to four.

Of course, the problems sourcing seafood throughout the pandemic have now—thanks to skyrocketing prices—become abundantly clear. What restaurant—looking to start strongly—would want to tether its fate to so much expensive, perishable product? And, while a variety of pastas might have helped bridge the gap that remained on the menu, you suppose the kitchen thought it wise to master a reduced menu rather than risk sinking in pursuit of needless scope. Whatever the reasoning, Adalina—in its opening months—leaned heavily on an array of about 20 dishes. A couple months later—more or less concurrent with the start of the restaurant’s brunch service—the menu expanded to around 30 dishes. While that number still stands a bit shy of the amount listed on the conceptual version originally shared in May, it can be assumed that Ahn’s kitchen is now operating at close to full capacity.

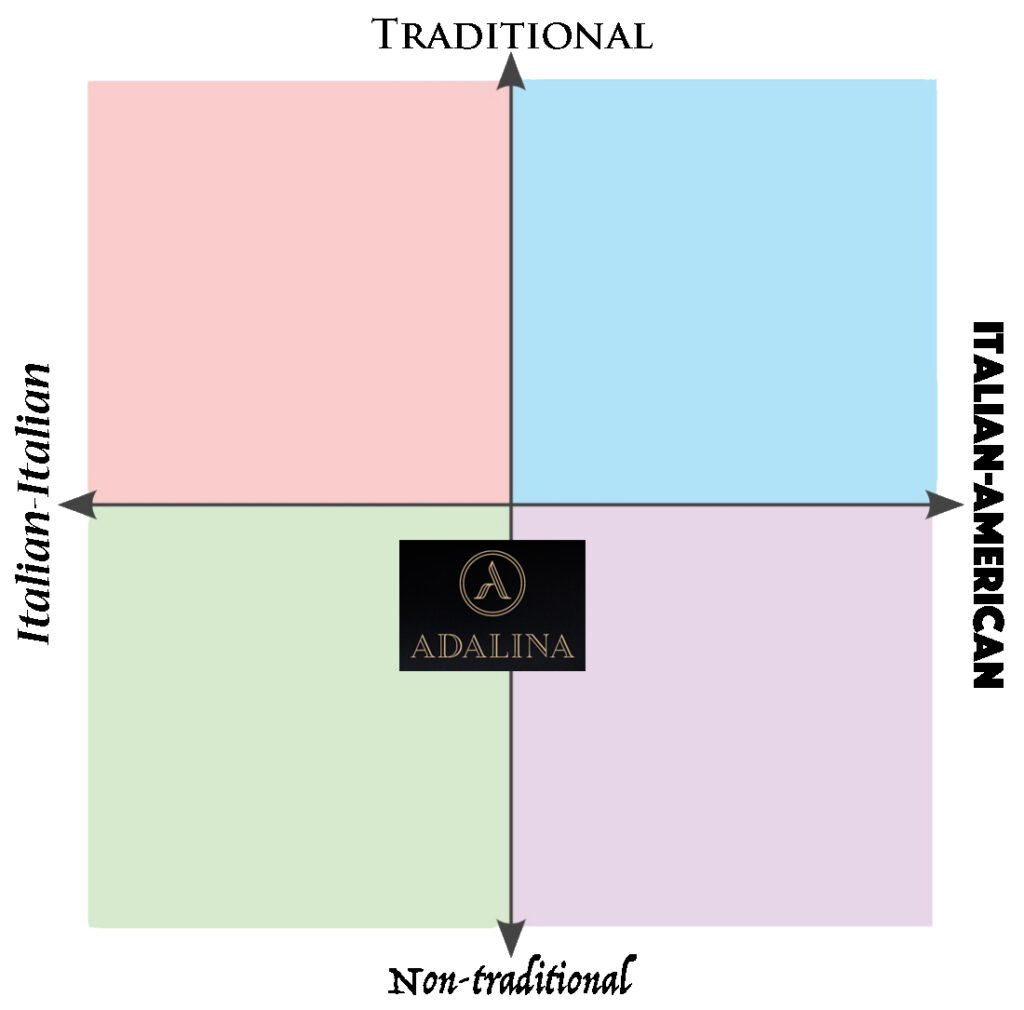

When previewing Adalina for your prior article, you oriented its cuisine on the “non-traditional” end of the spectrum while characterizing as just slightly more “Italian-Italian” than Italian-American in its composition. In truth, such a central placement signals that the menu will indulge both categories to some degree. It may even dip into one or two “traditional” preparations. But you think the restaurant’s position on the graph has held true: diners can expect a slightly greater emphasis on lighter, European-style Italian fare that is unafraid to draw on wider influences.

Though you would typically begin by analyzing the “Crostacei” section—later retitled to “Frutti di Mare” once it finally appeared on the menu—its absence across your earliest couple visits marks “Piattini” as the proper starting point.

The “little plates” are headlined by Adalina’s bread service—an altogether different proposition from the crumbs passed out by the bussers. $10 gets you a skillet overflowing with the cragged texture of a puffed garlic bread. Cut into quarters, each piece reveals a molten quattro formaggi (typically mozzarella, gorgonzola, fontina, and parmigiano) stuffing that oozes out from between the two ends of the crust. Relative to the garlic bread served at RPM Italian, Adalina’s is a bit less hard and crunchy. Its outer shell does retain a sense of crispness; however, the dish is defined principally by its filling. The blend of cheeses—studded with garlic—is absolutely decadent, and the whole package ultimately starts to resemble a stromboli. In that respect, it may not satisfy purists but will form a crowd-pleaser for most palates.

The polpettine—or meatballs—cost $16 for three pieces. Given that Adalina’s use of pork is limited to cured cuts like prosciutto and finocchiona, you assume the blend is entirely beef—perhaps featuring some veal—and sourced from the scraps of the restaurant’s popular steaks. To that point, the balls’ consistency is toothsome and tender without achieving the perfect smoothness of a pork-beef-veal blend. Nonetheless, the slightly heartier texture blends nicely with the coating of smoked Scamorza that blankets the three pieces of meat. The sharpness of the cheese provides the beef with a sense of intrigue while its melting quality provides some of the additional smoothness you were missing. A classic pomodoro adds ample balancing acidity to the equation in what ranks as a good—perhaps very good—but not superlative example of the form.

With Ahn’s take on arancini, you begin to taste some of the chef’s eclectic approach towards Italian cuisine. Of course, interpreting the dish in a “cacio e pepe” style is not altogether new—one need look no further than Gibsons Italia’s version using aged Acquerello rice, cheese fonduta, Tellicherry black pepper, and parmigiano. But Adalina’s rendition cannot be called derivative. For Ahn uses Forbidden Rice as his base and Manchego for his cheese. He fries the balls to an attractive golden brown and juxtaposes them with curls of crispy prosciutto.

Relative to Italian rice types like Carnaroli (of which Acquerello is a premium example), the black rice possesses a slightly larger grain and an undercurrent of sweet, nutty flavor. Relative to a typical melting cheese like mozzarella, Spanish Manchego—also favored by Sarah Grueneberg at Monteverde—displays a far sharper, fuller flavor that is both tangy and caramelly. And crispy prosciutto, of course, would improve just about anything. Adalina’s arancini eats in a familiar fashion but achieves its balance in an unfamiliar way. Moreover, Ahn’s chosen ingredients surpass mere novelty by lending the dish an added intensity. It ranks as a good twist on a recipe that has resisted innovation (apart from creative dipping sauces).

Rounding out the “Piattini” is a dish that has become something of a signature appetizer for Adalina. (At the very least, you have found it to be the one offered most willingly by management as a welcoming gesture). Its form is not exactly revolutionary as far as cheese and charcuterie setups go. However, in a manner reminiscent of the tigelle that accompany Monteverde’s hallowed burrata e ham, Ahn’s preparation makes use of a doughy vessel largely unknown in Chicago. His gnocco fritto are an Emilia-Romagnan specialty frequently served in local salumeria. The puffed, pillowy fried bread—which once inspired an Alinea amuse-bouche—forms an ethereal receptacle for thin slices of meat and a schmear of cheese.

For $22, guests receive three of the gnocchi fritti, a few spools of 24-month-aged San Daniele prosciutto, and a dollop of whipped ricotta dressed with Miel Thun honey. Though the portion might seem small for the price, it is roughly equivalent to Monteverde’s (at $28 before add-ons). The aged San Daniele and Miel Thun are well-sourced, quality products worth paying a premium for, and—together—they deliver a pleasing depth of sweet, porkygoodness. The whipped ricotta, other than acting as a “glue,” imparts a cleansing tangy quality that moderates any overload of pleasure. There’s also a pleasing bit of hot/cold contrast between the cheese and the gnocco.

If you had one suggestion, it would be to slice the prosciutto more thinly to better match its pillowy vessel (a move that, perhaps, would also give the impression of a larger portion). However, the dish forms a less indulgent counterpoint to the restaurant’s bread service that is just as sure to please. It marks one of the kitchen’s most traditional compositions but—due to patrons’ unfamiliarity with the form—one that needs no innovation to shine.

Moving on to the “Frutti di Mare” (formerly “Crostacei”) section, you will subsume Adalina’s individual shrimp cocktail and oyster offerings into your consideration of the restaurant’s entire “Shellfish Tower.” That item—one of the very hallmarks of the steakhouse genre—is rather close to your heart. For, while slabs of beef offer a succulent foil for Bordeaux varietals, these shimmering obelisks of seafood allow you to kick off the meal with the refreshing, driving acidity of Chardonnay, Riesling, or Chenin Blanc. Such a titillating dichotomy ensures that these establishments are not simply places to fill up on heavier fare; rather, one can weave a graceful path from sea to field to pasture over the course of the evening.

In your articles on RPM Steak and RPM Seafood, you contrasted the quality of LEYE’s “Seafood Towers” ($115 for “Petite,” $225 for “Grand”) with the “Chilled Seafood Plateaux” (priced at $130, $210, or $275) served at Bavette’s. Of course, you must also consider the “Fire-Roasted Seafood Tower” served up the street at Maple & Ash ($179 for “Pro,” $239 for “Baller”), as well as the “Mini” ($84) and “Gran Royal Platter Cotto & Crudo” ($168) touted at Gibsons Italia. Even Tavern On Rush gets in on the act with its “Seafood Tower for Two” priced at $99.95.

As much as you enjoy the tower form, its status as a steakhouse trope means it can sometimes embody little more than a dissatisfying money pit. Presentational flourish aside, you always ask yourself if a given restaurant has the sourcing relationships and turnover required to consistently put out top quality product. Despite efforts to brand components like the “Colossal Tiger Prawn,” “Wild Blue Prawn,” and “Colossal U-12 Prawn” on menus, big ticket items like Alaskan king crab and Maine lobster offer little clue as to their freshness and flavor. These crown jewels of the tower lean on their longstanding luxury totemic status to merit their price and must be trusted—as is—to truly satisfy.

Tavern On Rush ditches Alaskan king crab in favor of a Maryland crab and avocado cocktail, as well as seared Hawaiian tuna, on its competitively-priced tower. Maple & Ash opts to add scallops and Manilla clams to its selection of uniquely fire-roasted seafood. But, while both these restaurants share common elements with the usual steakhouse suspects, Adalina’s rendition competes principally with those of RPM, Gibsons Italia, and Bavette’s.

The towers at all four establishments share the same essential components: oysters, shrimp/prawns, Alaskan king crab, and Maine lobster. At $165, Adalina’s example lands at an equivalent price to Gibsons Italia’s “Gran Royal” while occupying something of a middle ground between RPM and Bavette’s small and large offerings. (The latter’s “Maude’s Tower,” priced at $275, maintains a singularly indulgent status. Its scale, despite the premium price, makes the other “towers” seem altogether puny).

Therein lies the difficult: how does a restaurant channel a sense of abundance while offering its seafood at a tempting price? Given the rising prices for crab and lobster in particular, any tower served today must impress with the pristine flavor of its items rather than rely on the pleasantly imposing image an overflowing collection of shellfish could previously offer.

Given Adalina delayed the launch of its shellfish tower until a couple months after opening, you expected big things from its arrival. The shrimp, which are branded as the “Sea of Cortez” varietal, are appropriately sized with a pleasant firmness and sweetness. However, they are let down by a tomatillo-based cocktail sauce that, while inventive, lacks the pungency you desire. The “market oysters” (a moniker that allows for nimble sourcing from various locations) were fine considering the price per piece ($2.67) comes in below RPM ($3.33), Bavette’s ($4.00), and Gibsons Italia ($4.00). However, given RPM’s “Prestige” and “Pearl” varieties are cultivated especially for the restaurants, you do not see any reason to skimp on paying for the bivalves should one really wish to enjoy them.

The crab—actually labelled as “Red King Crab”—refers to the same species as Alaskan but allows, seemingly, for a wider scope of sourcing. Knowing this item had grown particularly expensive, you paid for an additional serving (in the same manner you typically do at Bavette’s). Yet, even accounting for the extra meat, the portion struck the table as totally paltry—barely enough for three of you to split. Again, much of this is simply a reality of price increases. But the quality of the crab—while totally fine—did not impress you as being delicious enough to justify the premium. The Maine lobster—an element of seafood towers that is rarely exceptional—felt the same way. It just about matches the quality of Bavette’s and Gibsons Italia—though you must distinguish RPM Seafood as exceling in this category.

Overall, Adalina’s seafood tower did not leave you feeling gipped; however, you would opt not to order it in the future given the cost could be better put towards the establishment’s bonafide specialties. The restaurant’s oysters, perhaps, could present some form of value for those seeking a kiss of the sea. However, you would place Adalina’s seafood just behind Gibsons Italia’s (on account, somewhat, of the latter’s superior accompanying sauces). The RPMs’ towers are noticeably better than both while Bavette’s—oh, beloved Bavette’s—still reigns supreme within the category (in line with its price leadership).

The “Frutti di Mare” section also features a bold preparation of octopus that, before the rest of the seafood came online, found its home among the menu’s “Piattini.” Ahn charrs the cephalopod on a hot grill and cuts its arms into segments about an inch thick. (The curly tendrils at the end of the arm, meanwhile, are left a bit longer as to form a pleasantly crunchy “noodle”). The octopus is intermingled with slightly smaller wedges of crispy sunchoke, and both are placed atop a base of horseradish goat cheese that has been dusted with finely ground Sicilian pistachios. Slivers of fennel—as well as the odd cherry pepper—serve as the finishing garnish.

Though you have read complaints from some customers who have found their pieces of octopus to be tough—always a risk when going the grill route—you have found the dish to be well-prepared. The segments of arm possess a pleasing bit of chew that yields to an interior that is ultimately tender. Despite being on the thicker side, the pieces benefit from the textural contrast lent by the charr. This is particularly true of the suckers, whose tight, grid-like structure transforms into an intricate, crispy layer that plays off of the rest of meat beautifully. The golden brown sunchokes and finely-ground pistachios amplify this crunchy-chewy sensation, but the goat cheese—by your measure—is really the star.

You had never thought to pair octopus with cheese in such a manner, yet the goat variety’s tangy nature imparts that all-essential burst of acidity one traditionally attains through citrus. By thickly coating each of the components as one drags them through the plate, it adds yet one more contrasting texture to the party. Moreover, the horseradish dimension to cheese’s flavor provides the added pungency you felt was missing from the seafood tower’s cocktail sauce. Thus, while the charred, crispy, nutty flavors of the octopus-sunchoke-pistachio combination could threaten to overwhelm, the goat cheese—along with a hint of anise from the fennel and slight burn from the cherry pepper—provides a cleansing counterpoint. So many of the ingredients are recognizably Italian, yet Ahn wields them in an intelligent manner to balance the dish’s unique base. Bravo!

Of the “Foglie”—or “leaves”—section of Adalina’s menu, the “Truffled Caesar” commands special attention. Beyond pairing the omnipresent salad with a totemic luxury ingredient, the restaurant billed this dish—as far back as its earliest press releases—as a signature tableside presentation. However, while you did enjoy the show on the occasion of your first visit, this element was eventually phased out. You are not exactly sure as to the reason, but, based on observation, you think maneuvering the cart used for that purpose probably proved to be too much when the dining room was at its most crowded. Surely, the busser (in yet another moment that showcased their warmth of personality) did a good job making the dressing from scratch and shaving the various elements onto the greens. However, the presentation was not a showstopper, and it was likely worth sacrificing for the sake of a smoother overall guest experience.

The “Truffled Caesar” itself, absent that element, is respectable. Ahn utilizes yuzu in place of lemon, pink peppercorn in place of black, and black garlic in place of the fresh variety. These ingredients provide the salad with a more floral, fruity quality that remains balanced by an undercurrent of umami. Instead of traditional croutons, the dish features delicate crackers studded with crispy air bubbles that impart a pleasing texture. Grated parmigiano joins the truffle—along with a few brightly colored micro flowers—atop it all. But you have found the dressing to be a bit too watery. It does not cling well to the romaine, and, thus, the lettuce relies too much on the cheese for that all-essential savory flavor. The truffle itself—which you believe to be the black Burgundian variety—plays a purely ornamental role, yet you will admit the tubers featured on other menus around Chicago rarely show any better quality. The “Truffled Caesar” showcases an interesting approach to a classic dish, but—lacking the original presentational flourish—falls short of being a worthy signature item.

Ahn’s take on a caprese, nevertheless, has struck you as more successful. The salad, in its timeless simplicity, may actually be more challenging to contend with than the Caesar. For a strictly traditional recipe comes across as lazy while taking too many liberties threatens the dish’s legibility as a caprese at all. But Ahn has an ace up his sleeve and, like so many of the other items featured, it allows him to turn the recipe on its head without losing sight of its essential balance.

The chef substitutes standard tomatoes for a Southern favorite: the fried green variety. He also swaps mozzarella for crescenza, a fresh Alpine cheese that is tart, mild, and creamy. The basil, however, remains as the one tie to a traditional caprese. Ahn layers five or six golden-crusted pieces of green tomato on top of halved cherry tomatoes, dollops of crescenza, and a scattering of Calabrian chiles. The plate is topped off with a generous grating of parmigiano—something of a deus ex machina for Adalina’s cuisine (but one, when paired with other strong flavors, almost certainly enhances any dish).

Ahn’s innovative caprese could not succeed without the superlative execution of its main component, and the fried green tomatoes deliver. Their perfectly crisp exterior ensures you can secure a clean bite of the crunchy interior without it separating from the breading. The tomatoes’ sour, tangy flavor melds perfectly with the tart crescenza and bright, sweet character of the cherry tomatoes. While the basil and parmigiano provide familiar accompanying notes, it is the Calabrian chiles that pack the biggest punch. They enliven the salad with a sensation that is spicy, smoky, and fruity all in one. This intensity of flavors ensures every bite is amply seasoned while the creamy cheese component works to cool things down as necessary. The dish is not only a technical achievement, but it demonstrates the playfulness and personality you hoped Ahn would bring to the table in his approach to Italian cuisine. Well done.

For whatever reason, Adalina ditches the Italian translation of its next section—“Pasta a Mano”—and simply labels it “Handmade Pasta.” The decision to break with the titling format used for every other category of the menu struck you, at first, as schizophrenic. But, upon reflection, you think the mismatch speaks to the liminal culinary space the restaurant occupies.

Despite appearing under banners that the average customer may be unable to translate, “Bread Service,” “Shellfish Tower,” “Truffled Caesar,” and “Fried Green Tomato Caprese” remain legible as Americanized conventions within an Italian format. Meanwhile, pasta names like “Lumache,” “Campanelle,” “Mafaldine,” and “Cannelloni” might very well be as confusing as “Piattini,” “Frutti di Mare,” or “Foglie” would be if the latter terms did not benefit from the context clues provided by their constituent offerings (largely labelled in English). Yes, you do think that nearly any guest should be able to see the word “gnocchi” and deduce the section’s contents. But the “Handmade Pasta” moniker allows Ahn to title his dishes solely on the basis of the pastas’ shapes while composing the plates with full creative freedom. He need not defer to the usual suspects like spaghetti, linguini, or rigatoni made alla vodka, carbonara, or puttanesca to remain identifiable. Instead, diners are invited to take a chance on some unknown form paired with a unique sauce, and, thus, the stage is set to transcend tradition.

All that being said, Ahn would be a fool not to tip his toque towards at least one, undeniably classic preparation of pasta. And it is no surprise that the “Gnocchidella Nonna” (or, grandma’s gnocchi) leads Adalina’s line of offerings. For all the creativity the chef showcases across other parts of the menu, his take on the beloved potato dumplings demonstrates incredible restraint.

The gnocchi are formed into rectangles just over an inch long and just less than half an inch thick. They are tossed in a pomodoro sauce that features a few blistered chunks of tomato and garnished only with black pepper, parmigiano, and micro basil. At $19, the ten bites of potato dumpling coated in red sauce arrive looking fairly unassuming. “Is this the sort of plate a swanky new Gold Coast eatery puts out?” some might wonder. “Where are those luxury totemic touches and far-flung fusion elements that were supposed to prevent Adalina from becoming just one of countless Chicago Italian steakhouses?”

But it takes only one or two bites to change your tune. Texturally, the gnocchi melt masterfully—but not before offering one or two blissful chews of resistance. As they coat the palate, the dumplings capture and transmit the sum flavor of the pomodoro, black pepper, basil, and parm. There’s a spike of acidity and depth of sweetness to the tomatoes that—even lacking any stewed meat component (as with a traditional ragù)—satisfy some primal urge. You find it amazing that so few components can combine to create such an outsize effect. It means that Ahn has wielded his ingredients with a perfect sense of balance—the leaves of basil and blistered chunks of tomato providing an additional bit of textural contrast that underscores the gnocchi’s delicacy. No matter what the chef does across the rest of Adalina’s menu, the “Gnocchidella Nonna” testify that he can cook traditional Italian food at a very high standard. The dumplings affirm that Ahn experiments with the cuisine on the basis of deep understanding and technical proficiency—that he can please in the simplest possible way when the occasion calls for it.

Adalina’s “Campanelle”—a ruffled, conic shape reminiscent of “handbells”—take a different a tack. Rather than lean on tradition, the dish—whose only further description is written as “Pesto Not Pesto”—places its subversion of the familiar basil, nut, and garlic sauce front and center. The dish arrives blanketed by a layer of fresh basil leaves. The bells glisten underneath, having been coated in a richly colored olive oil that has been infused with garlic and pine nuts. A familiar dusting of grated parmigiano clings to the pasta, but the plate is otherwise unadorned.

Once more, you instinctually find the presentation to be a bit naked. You have been burned so many times by chefs who lack the finesse to craft flavorful pasta dishes while displaying a light touch. And you have come to suspect any recipe that fetishizes this degree of simplicity as merely reflecting a caricaturized interpretation of la dolce vita. (Oh, it would be wonderful to cook as they do in the old country if there existed equivalent access to the same quality of raw ingredients). Adapting such heritage recipes demands thoughtful interpretation, not merely replication within the context of drastically different foodways. A handful of raw basil does not a “pesto” make.

But, once more, Ahn excels. The campanelle are a perfect al dente and possess an engaging shape whose uneven ridges lend the dish a surprising heartiness. Their simple dressing in olive oil and grated cheese, surprisingly, succeeds. For the oil is powerfully fruity, deeply nutty, and appropriately pungent (from the garlic). Accented by the parmigiano, you could eat the pasta as is. Yet the avalanche of fresh basil imparts a transfixing sweetness that moderates the savory flavors brings you back for bite after bite. The crunch of the tiny stems and leaves, additionally, provides the dish with its principal textural contrast. When all is said and done, the “not pesto” really does remind you of “pesto” while delivering an added dimension of “bite” that goes beyond traditional, finely-ground examples of the sauce. The “Campanelle” has earned its place as one of the restaurant’s signature pastas since opening.

Adalina’s “Lumache”—a shape thought to imitate “snail” shells—also stand as one of the restaurant’s longstanding pasta preparations. In the period prior to the launch of the full “Frutti di Mare” section of the menu, guests could still find hallmarks like Maine lobster and “red” king crab situated within the dish. Unsurprisingly, at $38, the pasta ranks as the restaurant’s most expensive—being twice the price of the “Gnocchi della Nonna” and “Campanelle.” But “Lumache” has not always been made with lumache, and Ahn’s decision to change the pasta’s shape—the kind of retooling you praised Joe Flamm for at Rose Mary—speaks to the chef’s pursuit of perfection (even when it comes to headlining—and usually static—luxury fare).

The dish has always retained the same essential elements: Calabrian chile, scallions, and the aforementioned crustaceans tossed in a spicy tomato sauce. But, at opening, Adalina opted to utilize mezzi rigatoni—wide, ridged noodles of about half the size of the standard rigatoni. Now, to your eye, the restaurant’s “Mezze [sic] Rigatoni” actually look to be full-sized, and you are not sure why it chose the more complicated moniker. For doubling the size of that noodle would lend something closer to a cannelloini, and—at that point—one enters an altogether different world of stuffed pasta.

Mezzi or not, the rigatoni dwarfed the chunks of lobster and crab that comprised the original dish. While $38 is a high price relative to the menu’s other pasta preparations, that amount—thinking back to the pricing of the seafood section—ultimately secures only a fairly modest helping of shellfish. Juxtaposing the toothsome chunks with noodles twice or thrice their size makes them feel small. It makes what should feel decadent seem paltry—the long, cylindrical shape only serving to accentuate, in the wrong way, each of the few coveted, crustaceous bites one actually receives.

In switching the pasta’s shape to lumache, Ahn fulfilled the dish’s original promise. The “snail shell” noodles—here rendered more like a bent rigatoni—deliver the kind of compact bite the mezzi might have offered. Really, it almost looks as though the kitchen actually did simply fold the prior form into itself, effectively halving its length while doubling is thickness. Rather than gnawing along one layer of noodle, you now experience two-layered chew that naturally matches the mouthfeel of the lobster and crab. The chunks of crustacean get lost within the oversized elbows of pasta, lending the preparation a greater heartiness and perceived sense of luxury (even if the portion of shellfish is exactly the same). The lumache shape also better matches the curled strands of scallion, which introduce yet one more dimension of texture.

All things considered, it’s a good—not great—pasta that, nonetheless, was rescued from mediocrity by the savvy change in shape. The lumache probably does present a better value for those craving shellfish than anything in the “Frutti di Mare” category. Likewise, its sauce touches upon that “Fra Diavolo” spicy tomato character that is so nostalgic. But, as with Adalina’s “Shellfish Tower,” the feeling of abundance so essential to creating satisfying big ticket items is missing. That, of course, is a condition of the marketplace, and you give Ahn credit for making the most of those circumstances while putting out a seafood pasta that will, at least, scratch the itch for those customers who crave it.

Mafaldine—wide, flat ribbons of pasta with scalloped edges—form the centerpiece of yet another of Ahn’s pasta dishes. The shape, which may be alternatively titled “reginette” (or “little queens”), was first created in Naples and named after Mafalda of Savoy (the second daughter of King Victor Emmanuel III). It has become something of a trendy offering lately, appearing as part of Rose Mary’s excellent Abruzzese lamb ragù and as the basis for a seafood pasta at Alla Vita (more on that later).

However, while Flamm pairs the mafaldine with meat and Wolen pairs them with seafood, Ahn draws on the ribbons to craft a highly textural vegetarian dish that ranks as one of Adalina’s most exciting offerings. The chef studs the plate with halved cherry tomatoes, quartered artichoke hearts, sprigs of dill, and leaves of mint. They—and the mafaldine—are dressed lightly in olive oil that has been infused with red chile (a manner of saucing reminiscent of the “Pesto Not Pesto”). But the dish’s defining touch comes by way of almonds, ground so finely as to resemble breadcrumbs and strewn generously across the top of the plate. Once more, the logic reminds you of the basil leaves that blanketed the “Campanelle,” but Ahn steers this preparation in a far heartier direction.

While the “Pesto Not Pesto” shone due to the simple interplay of pasta, infused oil, and fresh herbs, Adalina’s “Mafaldine” is an ode to heterogeneity. You burst the glistening tomatoes against your tongue, crunch on the multilayered segments of artichoke, and chew on the long, ridged ribbons. The fine grain of the ground almonds coats every nook and cranny in between, accentuating the other textures at hand all the more. The dill and mint each bring a leafy consistency to the mix, but they really shine as flavoring agents. The former serves to enhance the nutty artichoke and sweet tomato while the latter balances the oil’s red chile component.

Despite nominally being vegetarian, Ahn’s “Mafaldine” is not nearly as green as the “Campanelle.” By intricately blending a variety of textures and flavors, the chef achieves something more than the some of their parts. Bite by bite, the dish is ever-changing and, thus, engaging. Moreover, the thick ribbons, wedges of artichoke, and all-encompassing ground almond amount to something pleasingly hearty. The combination, on paper, left you skeptical, but the composition succeeds both in its balance and the sense of satisfaction yielded. It demonstrates, once more, Ahn’s virtuosity with the pasta form.

That being said, the chef is not infallible in his experimentation. Adalina’s “Cannelloni”—or “large reeds”—showcases a neglected, rather niche shape of pasta suited towards stuffing. For $20, guests receive three of the cylinders—each cannellono boasting about an inch’s circumference and three inches in length—in a shallow skillet. The “reeds” are stuffed with a lemon-tinged blend of spinach and ricotta, sauced with a green tomato pomodoro, and covered with melted mozzarella cheese. The dish is garnished with oregano and a couple of the same crisp crackers that appeared atop the “Truffled Caesar.”

Cannelloni are typically categorized in the “lasagna” category, and Ahn’s preparation speaks to the reason why. The soft spinach-ricotta filling, delicate double layer of noodle, melted cheese, and crisp cracker—a doppelgänger for the crunchy top layer of an oven-baked pasta—combine to great effect. However, while these textures are impressive, you find that the flavors of the green tomato and lemon detract from the sense of richness you desire when it comes to a stuffed noodle. Rather than finishing on a savory note—something that could be accomplished through the introduction of mushrooms—the dish leaves you with a lingering tangy sensation. Yes, it’s cleansing—and perhaps even essentially balancing for some—but it relies on the mozzarella to ground it. And, in your opinion, any dish that relies so much upon melted cheese should at least indulge the ingredient to its fullest. Nonetheless, the “Cannelloni” is hardly a bad dish and might very well undergo a seasonal change in flavor profile that better suits your taste.

Overall, Ahn deserves real credit for building a pasta section that is entirely free of animal protein. Hell, discounting the “Lumache,” the category is positively vegetarian. But, far from being a gimmick, the decision allows the chef to offer a greater number of preparations to the widest demographic possible. For those who love meat will not be left wanting. Dishes like the “Gnocchi della Nonna” deliver the deep flavor of tomato you associate with a stewed ragù. Meanwhile, the polpettine, prosciutto,and a selection of steaks ensure customers with a carnivorous bent leave more than satisfied.

Ahn embraces the challenge of creating pastas without any recourse to the usual porcine and bovine suspects and, largely, succeeds. He demonstrates how the careful composition of diverse vegetable textures can amount to something just as satisfying as those beloved, canonical Italian recipes. In doing so, the chef distinguishes Adalina’s “Handmade Pasta” program as something more than a mere derivation. He showcases an understanding of the genre’s essential form without being wedded to any particulars. That is to say, Ahn’s work exhibits a bona fide Italian philosophy being applied in novel ways and fulfills the lofty expectations you had for this section of the menu given his unique background. You look forward to seeing how his pasta offerings develop further over time.

Adalina’s closing section—“Terra & Mare”—is tasked with fulfilling the restaurant’s aspiration to join the ranks of Chicago’s premium steakhouses. Though that latter category—“Sea”—can often seem like an afterthought, Ahn has gone beyond the delicate preparations of fish tacked onto menus as little more than chum for pescatarians. Compared to restaurant’s disappointing “Shellfish Tower,” which sought to deliver a purity of flavor that the sourcing could not quite deliver, the branzino and salmon dishes that appear on the menu offer the chef a greater canvas on which to express himself.

The former of the two fish, something of an ever-present item across Mediterranean and seafood-focused concepts, is roasted and served with frisée, thinly-sliced radish, and an eggplant mostarda. That latter component—of which Monteverde’s stone fruit rendition has long played a starring role in its burrata e ham platter—is something like an Italian chutney or relish. Chunks of fruit or vegetables are fermented in wine, honey, and mustard (in its volatile oil or whole seed form), yielding a resulting product with a softened texture and deep sweetness balanced by ample acidity. The sweet-and-sour condiment contrasts and amplifies the flavor of cheese and proteins with ease. And, by fermenting eggplant in such a way, Ahn introduces an undercurrent of bitterness into the equation that compounds the mostarda’s effect.

For the branzino itself is flaky, mild, and slightly sweet as is typical. Most restaurants might dress the fish in lemon and leave it at that. The frisée and radish would provide a crunchy, refreshing counterpoint. But the dish—unless it showcased the freshest and most flavorful branzino in the sea—would tread dangerously close to blandness. But, paired with the mostarda, the fish positively sings. Its firm flesh melds smoothly into the sappy fermented eggplant and crunchy greens, yielding a composite bite that is tangy, a bit puckering, and resonant with a honeyed character that extends the branzino’s natural sweetness into an impressive, lasting finish. The dish might not appeal to purists, but its fullness of flavor truly distinguishes the preparation from the boatload of other examples around the city.

Ahn’s salmon preparation, too, tells the same story. The fish—in its pristine Ora King form—appears on the menu at both RPM Italian and Gibsons Italia. The former restaurant roasts the salmon and pairs it with a Sicilian pistachio pesto while the latter chooses a Sicilian eggplant caponata as its accompaniment. (Oh, how interesting it is to note that Gibsons, unlike Adalina, pairs its branzino with a lighter lemon-caper sauce while reserving the more flavorful caponata—whose agrodolce sauce makes it quite like the mostarda—for the salmon). While these nut and nightshade components each respectively work to dress the fish with bold flavors, Ahn takes his preparation one step further.

In shaping the salmon’s flavor profile, the chef finds inspiration from one of Chicago’s own canonical Italian-American recipes: Chicken Vesuvio. While the dish’s history is murky—it being dated either to the 1930s restaurant The Vesuvio (located at 15 E. Wacker) or, more broadly, to a range of longstanding Southern Italian chicken preparations that were subsumed under the title—the combination of potatoes, peas, white wine, lemon, and plenty of oregano is highly nostalgic for those who have cut their teeth at local red sauce joints over the past century. Adapting a roast poultry recipe to a preparation of fish might seem heavy-handed, but Ahn displays both virtuosity and reverence for the recipe in how he executes the idea.

His salmon boasts a crispy, golden brown crust that is freckled with capers and adorned by leaves of micro oregano. The fish’s interior is rich and gently flaky. Such flesh—even when perfectly cooked—often runs the risk of being too mildly flavored. But a dozen bites of black pepper-studded potato gnocchi, intermingled with segmented snap peas, join the salmon in its bowl. The whole dish sits in a shallow sauce made from white wine, lemon, olive oil, garlic, and more oregano. In this manner, the familiar flavors of the Vesuvio receive a savvy facelift.

Gone are the titanic wedges of potato and sea of frozen peas that typically serve to bulk up the roast chicken preparation. In their place, the soft chew of the gnocchi and crunch of the podded pea segments serve to accentuate melting quality of the salmon’s interior. The fish, too, benefits from the texture of its crispy top crust. There, the additional layer of capers infuses each bite with an essential burst of salt. But it is the presence of the Vesuvio-style sauce at the bottom of the bowl that really ensures each bite of salmon is fully flavored. It soaks into the succulent flesh located beneath the fish’s crispy skin and enhances its mild flavor with that golden combination of lemon, wine, and garlic.

As you cut through the fillet, dip the chunks into the liquid, and intersperse them with bites of the potato gnocchi and peas, the sensation really does call to mind a proper Chicken Vesuvio. Yet the fish remains front and center, and Ahn succeeds in channeling nostalgia while retaining a light touch. Adalina’s “Salmon Vesuvio,” like the branzino, tends towards an intensity of flavor that might put off customers who desire simpler preparations. However, the dish is in no way heavy. It merely embraces a full array of accompanying notes appropriate to the Italian-American genre (and to the “Vesuvio” moniker itself). In doing so, Ahn’s composition forms a new chapter for one of the city’s signature recipes—and speaks to the chef’s understanding of (and appreciation for) the form.

With the turn towards the “Terra”—“Earth” or “Land”—section of the menu, Adalina stakes its claim as one of Chicago’s premium steakhouses. At the same time, the restaurant distinguishes itself by offering a decidedly Italian approach to meat entrées. Can it compete with dedicated beef specialists like Bavette’s, Maple & Ash, RPM Steak, and Gibsons Rush Street? Or does it aim only to excel in the specialty category occupied by RPM Italian, Gibsons Italia, and other establishments like Formento’s and Ciccio Mio?

Adalina’s “Veal Chop Parmigiana”—an item that has appeared on the menu since opening—affirms the restaurant’s commitment to refined Italian fare. It stands, alongside the “Salmon Vesuvio,” as perhaps the most expressly Italian-American of all the entrées. But, whereas the fish reflects a playful adaptation of a familiar recipe, the chop is altogether classic in its preparation.

At $60, Ahn’s veal parm outprices Ciccio Mio’s chicken parm ($24.95), Gibsons Italia’s chicken parm ($32), RPM Italian’s chicken parm ($32), and Formento’s chicken parm ($37). The closest comparison can only be made with the veal parm ($33.95) and veal chop ($58.95) offered at Carmine’s or the “Veal Milanese” ($49) also done at Gibsons Italia. Largely, however, Chicago has come to favor chicken over veal for the parmigiana form, and it is right to say that Adalina’s example is the only of its kind within the premium Italian steakhouse genre.

The size of the chop is nearly twice that of Italia’s Milanese (even though they are both bone-in and share the same thickness). So it is right to say that Adalina’s veal—perhaps due to the fact that they sell more of it proportionally—offers greater value in terms of portion size. Both recipes begin by coating the chop in Italian breadcrumbs pan frying it to a dark brown hue, and both executions yield a crispy exterior that frames lean, firm, but flavorful flesh. (Compared to chicken, the veal is a bit less juicy but offers greater structure and a cleaner bite. Cooked well, it occupies a perfect middle ground between the delicacy of poultry and the depth of beef).

But the comparison ends there. Italia’s Milanese is garnished with baby arugula and served simply on top of a tarragon-mustard sauce so as to accentuate its crust. Adalina’s parmigiana, in the traditional manner, is finished in the oven with layers of tomato sauce, grated parm, and fresh mozzarella. A few large, crisped leaves of basil complete the presentation, which arrives at the table looking attractively molten (yet not to the point of making the form of the chop itself anonymous).

Diving into the dish, you are pleased by the fact that the veal has already been cut into four sections. Anybody who has tried to slice a parmigiana preparation with a dull knife knows that they run the risk of sliding the melted cheese off of the meat altogether, transforming the picturesque chop into a goopy mess. Anticipating such a tragedy, Ahn ensures that each guest can cleanly transfer a cutlet to their plate.

There, thanks to the crispness retained by its breading, the veal is easily portioned into bite-sized pieces. You chew through its crisp bottom, which gives way to the tomato sauce, the grated parm, the melted mozzarella, and an added sprinkle of that titular parmigiano. The meat, though pounded thin, feels rich and substantial. The tomato sauce strikes with a spicy tang, lending the dish some added intrigue and imbuing the melted cheese with a practical, cooling effect. The crispy basil—should one be astute enough to maneuver it atop the cutlet as a sort of additional layer—breaks apart cleanly and adds a trace of sweetness. The bone of the chop, should you be lucky enough to get a hold of it, provides a few highly pleasing nibbles.

Ahn might not have done much to reinvent veal parm, but his is a clean, well-executed preparation that indulges the dish’s Platonic ideal. Using such a large, premium chop as his canvas speaks to the chef’s respect for the recipe. Each morsel tickles the nostalgia you feel for the item and, somehow, fulfills the impossible standard set by your gilded memories. Though it lacks any real competition in Chicago, Adalina’s “Veal Chop Parmigiana” measures up to the standard set by Carbone in New York City (and for twelve dollars less too!). It will form the city’s benchmark for a dish that, in its superlative form, deserves to be preserved. Ahn does justice to the Italian-American canon.

Though you have placed Adalina opposite Rush Street stalwarts like Maple & Ash, the restaurant’s selection of steak is rather more focused. Moreover, while Gibsons Italia boasts twelve different steaks, Formento’s offers five, and RPM Italian lists only four, Ahn’s menu contains but three cuts of beef. (And Ciccio Mio, for the record, only offers one). More specifically, Adalina hangs its hat on a $50 “Filet Tagliata,” a $91 “Carrara 640” wagyu strip steak, and a $165 “Bistecca alla Fiorentina.”

Though the filet’s accompanying flavors of parmigiano and eight-year-aged balsamic vinegar have piqued your interest, you have thus far neglected to sample the dish. Likewise, the “Carrara 640” has yet to grace your table. The term denotes a particular brand of wagyu beef with “certified genetics” cultivated in Australia by Kilcoy Global Foods. Relative to Adalina’s 12 oz. strip steak, Gibsons Italia serves 14 oz. of the same cut from the same source for the same price. Perhaps that added value is simply a consequence of the latter establishment’s volume, but, however you slice it, wagyu simply bores you.