Alinea, as long as you’ve known it, has never really been a “wine restaurant.” Though, you suspect, it once was. Speaking to Wine Spectator’s Laurie Woolever in 2007, Grant Achatz recalls a year spent as the assistant winemaker at La Jota in Howell Mountain while on leave from the French Laundry: “It was a fabulous experience, and really opened my eyes to not only making wine…but really just developing the palate.” Returning to Thomas Keller’s restaurant, he was frustrated by how “at that time, everybody wanted bottles or half-bottles with their meal.” The thought was, “when you have a menu that’s anywhere from seven to 20 courses long, one bottle of wine simply just doesn’t work with every course.”

When it came time for Achatz to cut his teeth at Trio, he happened tomeet Joe Catterson—who would go on to become Alinea’s opening wine director andgeneral manager. Catterson, by the chef’s own measure, “loves the great classicwines, but he’s more interested in the synergy between wine and food.” Trioallowed the pair to “commit to a wine-pairing program….[that] plays to thenature of [Achatz’s] cooking”—which is to say “foods that, in the scope of anexperience, are intended to jar, and in some cases are sweet and savory at thesame time.” This interplay of contrasts ensures “it’s impossible to select abottle or a half-bottle and walk your way through an entire tasting menu” atAlinea; thus, the restaurant has—from its inception—favored the flexibility awide range of paired pours imparts on the experience.

Still, that does not mean Alinea’s wine list at the time was anyslouch: “our wine list has over 650 selections, so you can certainly purchasethat trophy wine if you want it,” Achatz continues. Customers “will selectsomething from the list and we’ll incorporate it into their pairing program.”Sometimes, the restaurant will even “modify the food slightly” to accommodate thewine (a humble bit of back-of-house hospitality taken straight out of theCharlie Trotter playbook). As to the pairing, selections “run the gamut” asCatterson likes to “look for that obscure varietal or producer or country toshow people something that they’ve never had, or that they can’t go to theirlocal wine shop and pick off the shelf.” Such a pairing is “in constant flux,because the menu changes on a monthly or bimonthly basis.”

Looking at that Wine Spectator interview today, you only wish you could have dined at Alinea during those first few years. It seems like a much more dynamic and generous restaurant—eager to please and assuage guests’ experience of such novel food, rather than simply set a “showtime,” put the guardrails up, and whisk chumps in and out with a song and dance two times per night. It is unclear what became of Joe Catterson, but a cloying Chicago magazine article on Nick Kokonas from 2019 makes clear that he left the group in 2012 and that he felt “uncomfortable” with Tock’s paradigmatic refusal to accommodate guests’ last-minute changes.

December of 2011 marked your first visit to Alinea, and it suffices tosay that nearly all of your experiences with the restaurant have come in thepost-Catterson era. His departure seems to have been an inflection point forthe group. No wine director since has taken real ownership of the program—orachieved any level of prominence—at Alinea. Gary Obligacion was brought on as “Directorof Service Operations” (a decidedly corporate-sounding, unhospitable title)in 2012, but he always struck you as a glad-hander. Since Obligacion departedin 2018, it is hard to tell if the group’s hospitality has gotten better orworse. It has simply been “meh” for so long that nothing short of radicalchange—a “new line of thought,” if you will—is demanded.

You do not know enough about Catterson to feel comfortable naming himthe lynchpin of Alinea’s one-time, aborted effort to offer superlative service(wine or otherwise). However, you cannot help but notice the restaurant’s shiftfrom a people-focused enterprise to a cold, monolithic “entity” that doesn’t daresign their communications with anybody’s actual name. You cannot help noticethe ascendancy of “Grant and Nick” as a duo—which is to say, a chef and astuffed shirt who brags about how rarely he eats at his own restaurants—relativeto partnerships like Daniel Humm and Will Guidara that imply the equal footing thatcuisine and hospitality most certainly share. You also have certainly noticedhow the technological and financial conveniences Tock offered restaurants quicklybecame bulwarks against accommodating customer requests. Not everywhere, butcertainly within the Alinea Group, where—over the course of a few years—serviceinteractions became a series of stilted “variations on a theme” more concernedwith keeping “the show on the road” than conjuring peak experiences.

In short, soulless business interest supplanted any chance Alinea had of becoming an institution like the French Laundry (under longtime general manager Michael Minnillo) or Le Bernardin (under longtime directeur de salle Ben Chekroun). It is also no surprise that Grace so threatened Alinea’s fine dining hegemony before its untimely demise, given Curtis Duffy’s manner of sharing the spotlight with general manager Michael Muser. Such a partnership is not strictly necessary to imbue a restaurant with soul—Brooklyn Fare’s César Ramirez (or any great omakase, really) comes to mind. However, when one privileges good business as much, if not more, than “art”—when one denies hospitality its rightful seat at the table—the end result can only be cookie-cutter experiences designed for conspicuous consumers’ social media feeds. Superficially fancy-looking food devoid of substance, story, or soul. That is to say, Alinea 2.0 is a nutshell.

In a sense, The Alinea Group Wine Series is the endpoint of the darkesttimeline where Kokonas, a derivatives trader, does wine events while Catterson,a career hospitality professional and the man who perhaps knows how to pairAchatz’s food best, is cast off never to be heard from again. Looking back atyour Alinea pairings from the post-Catterson era, there just isn’t much to getexcited about: Beaucastel Blanc, Bollinger, Dr. Bürklin-Wolf, F.X. Pichler, Guigal,Keller (RR), Knoll, Krug (Grande Cuvée), Pierre Péters, Quilceda Creek,Quintarelli, Ridge, Robert Weil, Smith Haut Lafitte (Blanc), Torbreck, Zind-Humbrecht.There is no doubt that this list includes great producers (including a coupleof your personal favorites), but, at some point, Alinea’s wine program becamemore about up-selling customers on the next “tier” of wine (non-alcoholicoptions are only offered upon request) and reflecting “bigger” names and “better”value. Offering compelling wines (let alone “one” pairing) that truly completedAchatz’s food fell by the wayside, as servers memorize and reprise three setsof wines in broad strokes that become just a bit more fine as one doles outmore money.

Ultimately, the restaurant has settled on fulfilling guests’expectations with representative wine pairings rather than challenging theirpalates and engaging in the hard, rewarding work of cultivating wineappreciation. The offerings are not clearly better than those at Smyth orOriole, and the hurried service certainly pales in comparison. Fifteen years ofsavvy buying and cellaring could have made Alinea a national destination forboundary-breaking food and wine pairing. Yet that sort of savvy buying requiresexpertise, which can only come about from fostering talent. Wine service—andservice in general—was sacrificed for the sake of better “efficiency” andincreased profit. The magic was stripped away, and the pairings devolved into apantheon of “recognizable” names (a value proposition) rather than anexpression of artistry equal to Achatz’s food. They are a frill, plain andsimple. They are “coach, business, and first class” tickets as far as therestaurant is concerned—superficial differences separated by a supremeupcharge, and yet everyone feels similarly cramped, cranky, and hungry uponlanding.

Roister’s wine list was an absolute wasteland for the first few yearsof its existence and has only, recently, put together a selection that can becalled competent (and maybe even charming should they restock on those wonderfulmagnums of Dönnhoff). It must be said that the restaurant, under Andrew Brochu,had little need for fine wine. In fact, you remember being absolutely delightedby the cooler of humble beverages offered along with his “High Brow, LowCountry Boil” menu. Yet that was a different Roister—one with a soul. As therestaurant has become less Southern-inflected and more of a “rustic” Alinea(or, perhaps, a place to house their overflow), the quality of wine hasclimbed. The range of affordable magnums offered helps set the mood in thedining room, while a small selection of bottles by coveted producers like PYCM,Arnoux-Lachoux, Quintarelli, and Giacosa are actually offered at reasonableprices.

Next’s wine pairings have tended to be stronger than Alinea’s, but—thenagain—you would say the same about the food itself. The group tends to performbetter when forced to color “inside the lines” of a set theme rather than floatoff, as is their tendency, into rootless abstraction. It is for this reasonthat you felt the Wine Series displayed such promise: the concept of a “winedinner” evokes certain expectations (positive or negative), yet there is ampleroom to surpass or subvert them. Next is still guilty of perpetuating a three-tieredsystem of pricing; however, the tiers of wine actually take on distinct themes—forexample, an ultra pairing may offer only wine and sake while the reserveincorporates distilled beverages. Next’s non-alcoholic option is not obscured(as it is at Alinea), but you must fault the restaurant on insisting sostrongly they do not have a bottle list when other favored guests have made clear(on sites like Cellartracker) that they were allowed to order from one.

This is all to say, you were excited to see the Alinea Group get theirfeet wet hosting dedicated wine events. Excited, you say, as someone investedin the growth of Chicago’s (and the nation’s) wine appreciation (particularlyamong the yuppies that form the restaurant’s target audience). You were alsorather skeptical of the events, owing to Alinea’s underwhelming track recordwith wine service over your many visits. However, you will always be the firstto applaud a step in the right direction, and so you attended four of the group’s“wine series” events in 2019 and 2020. They were, in order, focused onJean-Louis Chave, Hundred Acre, Louis Jadot, and Larkmead. While the inaugural dinnershowed some promise, each subsequent one grew more disappointing. As is usual,you will condense the entirety of your experiences into one cohesive narrative,preserving as many interesting details and as much comparative potential aspossible. So, let us begin.

While you rue the fact that St. Clair Supper Club—formerly Roister’s “prepkitchen”—no longer dishes out Brochu’s whimsical set menus, you must admit that,on a night like tonight, the subterranean space truly does feel like a privateclub. Entering the building, you approach Roister’s hostess, are recognized,greeted warmly, and guided over to the restaurant’s upstairs bar for a briefpause. The bartender doesn’t miss a beat in offering two drink menus, but youmust refuse any hard liquor in a bid to preserve the palate for the tasting tocome. There’s just enough time to take a few sips of water before the hostessreappears to lead the way. Down the stairs, past the bathrooms, and through thetufted leather door—where a menu board confronts you with that evening’sspecial: the wines of this or that treasured producer. To your left, the fullspan of bottles stretch across St. Clair’s kitchen counter. You peruse for onlya moment before being greeted by a member of Alinea’s wine team, Champagne intow.

After a bit of chatter, you work your way to the end of the counterinto the dining room “proper.” Anybody who has dined at St. Clair Supper Clubknows that it is an intimate space, seating somewhere between 20 and 30 guestsat two- and four-top banquettes alongside a lone horseshoe booth. Bar seatingis offered at the counter, but it isn’t typically used for these events. Thoughthe Alinea Group’s inaugural events made use of place cards, later dinnersembraced a “free for all” style of seating. The former, you have found, is moretraditional for higher-end wine dinners. It implies a curation of theexperience and ensures, should the winemaker or another representative bepresent, that they are able to engage the assembled parties in a cohesive way. Atthe minimum, seating should guarantee the guest of honor’s comments can easilybe discerned (more on that later). At its best, planned seating forms theconversational backbone of the evening, allowing the assembled experts to guideguests towards a richer experience with the featured wines across the myriadfacets of wine appreciation. This is to say, place cards imply being “hosted”with some intention; whereas, seating oneself and one’s party at a communaltable outsources the generation of social inertia to the guests.

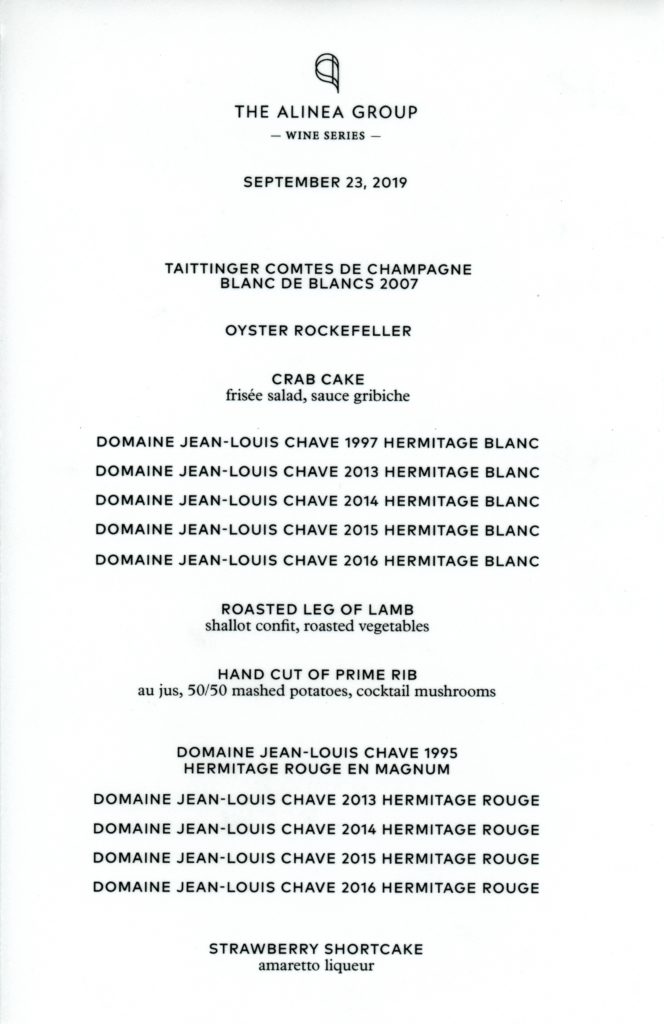

The first of the wine dinners you attended—the “Hermitage of Jean-LouisChave”—seemed to handle seating best. You were a party of two, and, afterreceiving that welcome gulp of bubbly, you walked into the dining room and foundyour name appended to a favorable two-top towards the front of the dining room.While certain guests chose to remain standing and socialize until the formalcall to be seated, you took your spot at the table and, thus, avoided the constanttwisting and turning required to stay out of the way in the cloistered supperclub space. There were no special guests from Domaine Chave present for thedinner, but, from your spot, it was easy to hear the announcements and other remarksmade throughout the evening by the members of the Alinea team. Moreimportantly, you were able to direct your attention solely towards the winesand your dining companion without the distraction of making “polite”conversation with strangers. The seclusion of the two-top (in truth, you couldhave conversed with the adjacent table as your date did) secured the purity ofthe experience: great wine and great company undiluted by any demand toentertain “other” people. At $735 per person (excluding service and tax) forthat particular dinner, the two-top ensured—at least—you could enjoy theevening at your own level of energy.

The second of the four dinners—titled “Hundred Acres [sic] Dinner atthe St. Clair Supper Club”—revealed one of the pitfalls of pre-arrangedseating. It also marked a change in title from “The St. Clair Supper Club WineCollector Series” (that which was used for the Chave event) to “The AlineaGroup Wine Series” (a moniker that has graced a range of dinners at Roister andNext as well). The change would seem, naturally, to reflect the expansion ofthe series to the group’s other restaurants. However, you think there issomething more sinister at play—something that will become clear as your analysisproceeds. In contrast to the first dinner (for two), you booked the HundredAcre dinner as a group of three. At $805 per person, the second dinner wasslightly more expensive too. That is to say, you came expecting an experience thatwas as good, if not better. You three gentlemen lumbered downstairs in the samemanner, received the welcome glass of champagne, found the place cards, andseated yourselves at a four-top towards the back wall of the dining room. Now,a party of three guests at a private event always spells trouble. You knowthat. Yet you hoped the dinner’s sticker price might work to insulate you fromany unwanted “additions” to your party. What sort of person would pay such aprice to drink and dine alone?

Nobody, truth be told, but that doesn’t mean the seat laid empty. Oneof Hundred Acre’s sales representatives—no, not Jayson Woodbridge—graced youwith his company. The man was pleasant enough and—alongside one of the winery’sregional distributors—acted as the evening’s “master of ceremonies.” That is tosay, your companion spent most of the dinner on his feet and schmoozing withthe well-heeled patrons who might like to purchase a few thousand dollars worthof the cult Cab. Your party had little to offer other than liking the wine andenjoying the irreverence of his sales pitch (relative to Napa Valley’s moreaustere estates). He was savvy enough not to disturb the three of you muchfurther—and, truth be told, he spent so little time at the table as to misseating some courses entirely. All in all, you did obtain the privacy youdesired. However, the arrangement left you feeling like somewhat of a voyeur,as the attention paid to other tables by the interloper only underscored thatthe evening was less a celebratory “wine event” and more a cynical marketingopportunity. Truth be told, Hundred Acre just does not have much of a “history”to draw on. As tasty as it is, the wine is inextricably linked to the winery’seccentric owner, without whom it becomes yet another expensive California winenearly indistinguishable, at times, from the other 100-point Parkerized bottlesin the same price category.

The third of the “Alinea Group Wine Series” events you attended revolvedaround Maison Louis Jadot, the Burgundian négociant and domaine with widespreadtendrils throughout the region. The winemaker, Frédéric Barnier, was in attendance,yet you did not find him—or any other unexpected guest—sequestered at yourtable. Rather, you and your date traversed the stairs down from Roister andinto St. Clair Supper Club to find… a free for all. Your welcome glass ofchampagne came with the admission that seating was “first come, first served.”At only $295 a head, the event clearly occupied a different price category thanthe previous dinners. However, you could not help feel that the Alinea team hadabdicated its duty to properly host the event.

Groups of two, such as yours, were left to pick their poison among anarray of half-filled tables which just as easily could have been split to suitthe tickets as they were sold. Some quick-thinking patrons opted to sit on thetall stools facing the counter (and shielding themselves from unwanted contactacross a shared table). You chose the empty horseshoe booth by the door, waitingon tenterhooks to see who might occupy the remaining two place settings.Another young couple answered the call—and, clearly, had similar designs, asyou avoided saying anything more than a passing greeting to them throughout theevening. You got what you wanted, so why complain? Because, while the boothserved as a bulwark against unwanted socializing, it altogether obscured theability to hear the winemaker speak. Thus, despite the supper club’s constrictedspace, the Alinea Group shirked the responsibility of arranging guests in anorderly fashion while also failing to ensure all the accessible seats couldmeaningfully participate in proceedings. It sounds, you think, almost like atotal abdication of the restaurant’s responsibility as host. At a price pointthat is, nonetheless, not far off a meal at the flagship itself, you had a hardtime seeing the connection to Alinea “hospitality” at all.

The fourth of the wine events you attended took you out of thesubterranean space below Roister and called you over, next door, to Next. “Nowwe’re talking,” you thought, “a real Alinea Group restaurant” (and onethat long deserved a Michelin Star before Roister gained and lost its own). Youstepped through the awning, through the vestibule, and into the dining roomwith your date. At $375 per person, the dinner—centered on Napa Valley wineryLarkmead—measured closer to the Jadot event in price than Chave or HundredAcre. Thus, your expectations were tempered, and for good reason. That welcomeglass of champagne came with the same sheepish instruction that seating wasself-serve. Though Next’s dining room is more spacious than St. Clair’s, youfound yourself squeezed at the end of a table for six along with two oldercouples from Indiana who knew each other. They were charming, as was winemakerDan Petroski (who, thankfully, was within earshot of all the guests).You cannot remember if all the two-tops were full or if they were offered atall. But, with every painful conversational probe throughout the evening, youagain felt cheated from what may easily have been a more intimate, personalexperience.

While, at an organizational level, the Alinea Group Wine Series fallsshort, the move away from name cards merely presaged the deeper problems thatpervade the events. Perhaps it is best to proceed thematically. Whether youwere seated in isolation or forced to mingle with strangers, the wines at eachof the dinners should have—ostensibly—provided the raison d’être to endure anymanner of proceedings. Chave, to wit, is a great estate, and any opportunity totaste a range of his Hermitage should be coveted, right? Personally, you lookedforward to that first dinner given your lack of exposure to the great wines ofthe Northern Rhône. Five vintages of Hermitage Blanc alongside another five ofHermitage Rouge sounds unspeakably decadent—yet it is the quality anddistinctiveness of different vintages, rather than the quantity of wine served,that really matters.

You cannot claim that 2013, 2014, 2015, and 2016 were poor vintages inthe Rhône by any stretch of the imagination. 2015 is “potentially monumental”according to a respected critic while the years on either side of it are both goodand geared towards early drinking. Paradoxically, 2013 is the most backwards ofthe bunch and is said to benefit from additional time in bottle. The wines (Blancand Rouge) from these four years formed the core of the Chave event. They wereaccessible (if not giving), they could be contrasted (in broad strokes), and theywere by no means disappointing. However, there is no doubt they were drankyoung—generally three or four years before the most generous drinking windowascribed to them. The wines provided a glimpse of the glory to come later downthe road; they made a superficially pleasing impression as many great bottlingsare apt to do when drank so close to their genesis. Given that the event wasbilled as “a vertical examination of the last four vintages of Chave Hermitage,”you knew what you were signing up for.

But should a “Wine Collector Series” really be concerned with curatinga range of more or less current release wines that are still available atretail? Do “wine collectors” really drink verticals of successive recentvintages for pleasure? Such a passing glimpse at the greatness Chave’s winesmay attain in ten, twenty, or thirty more years’ time only serves aficionadoswilling to dole out the dollars for a case (or two) to track over the course ofthose decades. That being said, there were two reference point vintages ondisplay: the 1997 Hermitage Blanc and the 1995 Hermitage Rouge, both of which—whilenot quite legendary—you must admit come from great years and displayed the peakof their maturity. Thus, guests were teased with an even smaller glimpse of therespective wines at their absolute prime. The older vintages formed the “spoonfulsof sugar” that salved the experience of the younger ones. They transformed the eveningfrom an extended sales pitch for vintages still on the market in Chicago intosomething vaguely resembling a wine event.

That is to say, the guiding light at such an event should be the appreciation—no, the celebration—of a great domaine. That means selecting representative—if not rare—wines rather than relying on what happens to be gathering dust on the shelves at the moment. Take, for example, the vertical Antonio Galloni describes in this article—a trek through mature vintages of Chave strutting all their stuff. Drinking coiled, nascent wines just isn’t much fun. It doesn’t encourage wine appreciation but, rather, investment. Anybody could make the same guess as to the wines’ development based on vintage conditions and critics’ scores. The end result is the same: they need time to display their promised pleasure. The 1997 and 1995 could have been emotional wines for some parties present—you will not deny them that experience—but the event, overall, had the pervading sense of being a vehicle for New York Vintners wine sales. And is it really a good idea for Alinea to leverage its brand in such a cynical way? Mind you, the Chave dinner was not only the inaugural event in the wine series but, you think, the best.

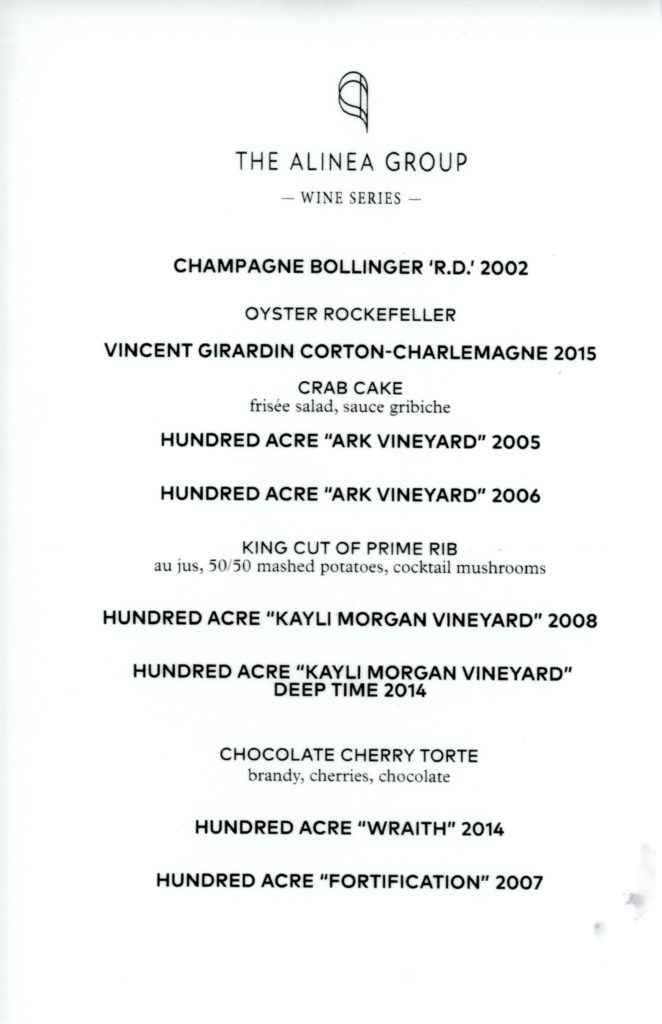

The selection of wines put forth at the Hundred Acre dinner followedmuch of the same pattern—that is, a few younger vintages (also, of course,offered for sale that evening) were offset by a couple well-aged ringers whichsought to increase the value proposition. The evening began well enough withBollinger’s 2002 “R.D.” Champagne, a blend of 60% Pinot Noir and 40% Chardonnayfrom 71% Grand Cru sites. This was followed by Vincent Girardin’s 2015Corton-Charlemagne, a befuddling bottle both in its age and style. You canunderstand the need to serve a “proper” white wine with a certain portion ofthe meal (actually, you do not, given you have attended several excellentevents devoted entirely to red wine). However, the relative mediocrity of theproducer and youth of the wine did the evening no favors. It was pleasant, yes,but out of place, and it indicated an unwillingness to craft either a coherentprogression of wine or an appropriate menu that featured, principally, thestars of the show (but more on that later).

Whereas the best wines from the Chave dinner were split between the “white”and “red” flights, the Hundred Acre dinner cut right to the chase. The youthfulCorton-Charlemagne was immediately followed by the 2005 and 2006 vintages ofHundred Ace’s “Ark” vineyard. Those wines were then followed by a flight of the2008 “Kayli Morgan Vineyard” as well as the “Deep Time” release of that samevineyard’s 2014 vintage. The evening ended with Hundred Acre’s 2014 “Wraith”and the 2007 release of “Fortification,” a Port. Placing the mature, mellowwines early on was probably the right choice, allowing the younger vintages ofsuch a “juiced-up” Napa cult Cab the benefit of richer fare. In truth, the 2005and 2006 Ark wines were the first releases from that site and carried with thema certain sense of that history. However, tasting them towards the beginning ofthe meal ensured the night reached an early crescendo. With the sales representativeby your side, you tasted history. Yes, and then you proceeded through the restof his portfolio before ignoring the order sheet appended to your event bookletand scurrying out the door.

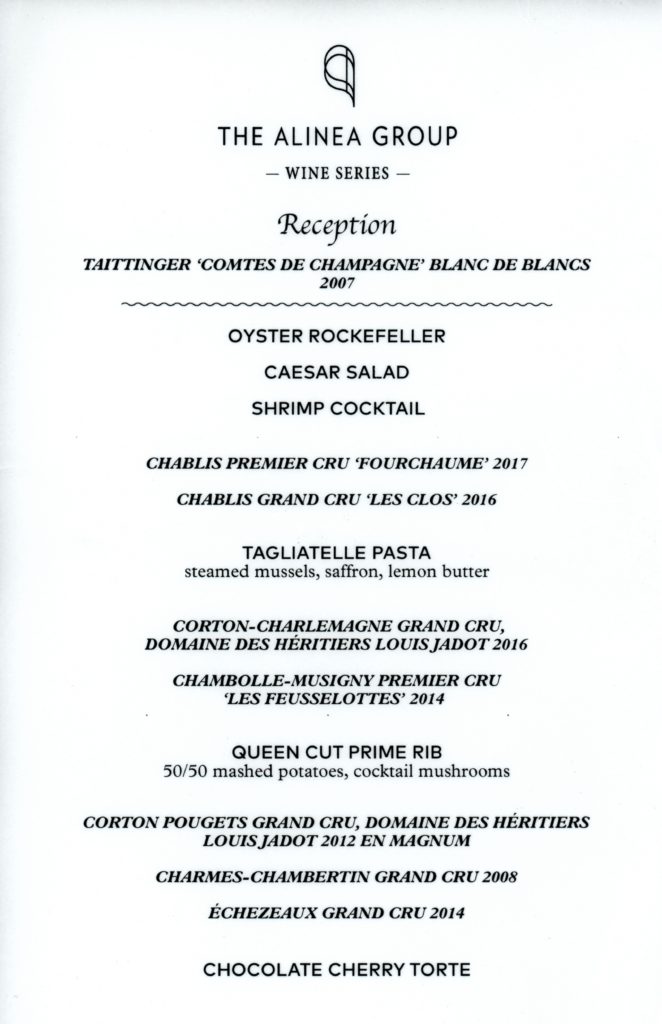

The Maison Louis Jadot dinner, perhaps owing to the house’s breadth ofholdings, put forth the most diverse array of wines. Hidden away in theacoustically-isolated horseshoe booth (and, thank heavens, undisturbed by theother party who parked themselves there), you worked your way through whatwinemaker Frédéric Barnier termed a terroir-driven tasting. After a welcomeglass of 2007 Comtes de Champagne (the same served at the Chave event) came thewhite wines: a 2017 premier cru Chablis, a 2016 grand cru Chablis, and a 2016Corton-Charlemagne. While these wines, even in the context of Burgundy, wereyoung, they made for an engaging comparison of crus, appellations, andvintages. The same can be said for the evening’s red wines: a 2014 premier cruChambolle-Musigny, a 2012 Corton Pougets en magnum, a 2008Charmes-Chambertin, and a 2014 Échezeaux (altered from the 2014 Grands-Échezeauxlisted on the event page). Again, the lineup—while young—offered a niceinterplay between sites of different status in different vintages.

Perhaps you felt that way because, at $295 (the cheapest of all theWine Series events you attended), the Jadot dinner was not burdened with theexpectation of offering any bottles that were particularly rare. Likewise, thedriving force for the event was to feature a range of different wines ratherthan conduct a “vertical examination” of recent vintages for the sake of salesor simply choose an arbitrary assortment of bottles to accompany a brand ambassador’ssong and dance. Perhaps, most of all, it mattered that Louis Jadot’s winemakerwas in attendance (even if you strained to hear him). For as highly as theAlinea Group thinks of itself, these events should always endeavor to championthe artistic process involved in creating great wine rather than treatingguests as a captive audience for the company’s friends who sell wine. Thepresence of the winemaker—like Grant’s own presence at Alinea—papers over anynumber of missteps made in the name of experimentation. That doesn’t reallyring true for Jadot’s classic expressions of terroir, but it surely does forthe wine events themselves. If the wines are not superlative in their ownright, it is only the presence of the vigneron that lends the occasionsome gravitas. Why else bother paying for an event that only exists as a meansto sell—not celebrate—“art”?

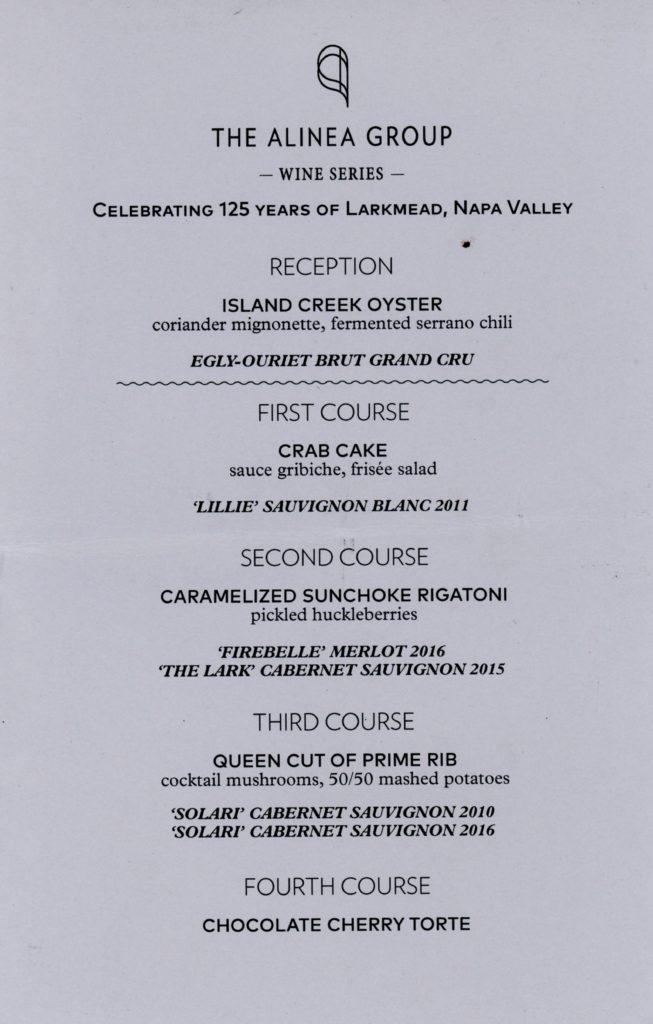

All that being said, the Larkmead dinner—priced at $375 perperson—seemed poised to be the most balanced of all the wine events. The costof admission was not too high or too low and the winemaker (Dan Petroski) waspresent for an evening of “storytelling and imbibing” in the more dignifiedsetting of Next’s dining room. While the event was billed as celebratingLarkmead’s “125th Anniversary,” the winery’s contemporary historybegan with the second generation of ownership and replanting of its vineyardsin 1992. Thus, Larkmead’s history is very much being consciously constructed(or reconstructed) from a branding perspective (though it was, admittedly, founded in 1895).For that reason, the dinner lacked the enchantment that a multi-generationalfamily estate preserving a unique piece of terroir evokes. Likewise, the changeof ownership and recent replanting ensured there would be no extraordinarily-agedwines on display. Still, Petroski’s presence was, itself, enchanting, and thenature of Larkmead’s revival means that his role in expressing the diversity ofsoil types on the estate is unusually essential (and engaging to hear about).

The evening began with a glass of Egly-Ouriet Grand Cru Brut thenproceeded to the 2011 vintage of Larkmead’s “Lillie” Sauvignon Blanc. The estate’swhite wine was a winner, presenting a nice change of pace from the 2015Girardin Corton-Charlemagne at the Hundred Acre dinner and the young JadotChablis and Corton-Charlemagne wines. Still, you do not think it would havebeen much to ask for them to serve a vintage of their Tocai Friulano just forfun. The red wines offered a representative assortment: two vintages (2010 and2016) of “Solari,” the winery’s most “complete” Cabernet Sauvignon; the 2016 “Firebelle,”a Merlot-dominated blend; and the 2015 “The Lark,” which is Larkmead’ssignature, more terroir-driven Cabernet Sauvignon. Though actually offering thefewest wines of all the Wine Series events, this selection felt satisfying.Perhaps it was Petroski’s charm, expertise, and generosity in refilling glassafter glass that struck you. While Jadot’s winemaker also spoke of “terroir,”he and the wines—perhaps due to their austere, traditional nature—were a bitmore inaccessible. Larkmead’s wines try to distinguish themselves from theirNapa brethren, and, thus, the event carried the thread of “terroir” in anengaging way. It really showed how much the Chave and Hundred Acre events werehandicapped by both the unglamorous setting and presence of salespeople. Inretrospect, they seem closer to timeshare seminars than wine events incomparison.

While you think the Alinea Group Wine Series events are improving invinous terms—eschewing eye-catching labels and an undercurrent of being “sold”the wine by the sponsoring distributor—there is a reason you have saved adiscussion of the food for last. With regards to the menus served during thecourse of the four events, you have never been more disappointed—nay,insulted—by the group’s efforts. Strangely enough, it was the inaugural Chaveevent that approached the comestibles most honestly, touting “a menu of primerib and classic faire paired to showcase the wines.” Underneath the listed wineswas posted the bill of fare: “crab cake with frisée salad and sauce gribiche,” “roastedleg of lamb with shallot confit and root vegetables,” “hand cut of prime ribwith 50/50 mashed potatoes and cocktail mushrooms,” and “strawberry shortcakewith amaretto liqueur” for dessert. Fair enough, you thought. That’s pretty muchthe normal St. Clair Supper Club menu with the addition of a simple lamb dish(which, nonetheless, would go very well with Syrah).

The Hundred Acre Dinner—the most expensive of the lot—stated the wineswould, likewise, be “accompanied by a menu of prime rib and classic fare pairedto showcase the wines.” Okay, you can understand drawing on the prime rib yetagain to go alongside such big, bold New World wines. The specifics of themenu, unlike before, went unlisted on the event page. You might have gottenyour hopes up for something special. Instead, you were served “oyster [yes,singular] Rockefeller,” “crab cake with frisée salad and sauce gribiche,” thepromised cut of prime rib, and a “chocolate cherry torte” for dessert.

The more affordable Louis Jadot dinner changed up the language a bit,promising “a special menu to showcase these singular wines” (which, again, wentunlisted). The oyster (singular) Rockefeller returned while the crab cake didn’t.It was replaced by a paltry cocktail of a couple shrimp and a Caesar salad. Therewas one dish, you must admit, that was especially made for the menu: atagliatelle with steamed mussels, saffron, and lemon butter that marked thetransition from the Corton-Charlemagne into the red wines. Then, of course, yourold friends—the prime rib, mashed potatoes, and cocktail mushrooms—reared theirheads again. You cannot remember what the dessert was, but it was surely one ofSt. Clair’s creations that—even on a “normal” evening—fall far short of whatthey could and should be.

By the time you reached that final Larkmead dinner, you had just aboutabandoned any hope of gastronomic delight. Nonetheless, the staging of theevent at Next—rather than Roister’s basement—was an interesting choice. Couldit be that their kitchen—then engaged in its “Tokyo” menu—was required to crafta meal of more consequence? Or was the decision made for the sake of utilizinga more becoming (or simply larger) dining room? It’s the Alinea Group, so theanswer should have been obvious. You were served the same ol’ crab cake andprime rib. To the best of your recollection, there was one special—a pasta dishyou believe (it was actually a sunchoke rigatoni)—but by that point you had ceaseddocumenting the wine dinners in any sense.

To summarize, four events at two different venues over the course of five months—costing a total of $2,210 per person—yielded a grand total of three unique dishes from a restaurant group that holds four Michelin stars (in total) and who specializes in “molecular gastronomy.” The train of new thought, for some reason, has gone completely off the rails. What they did create—lamb and two pasta dishes in a classical style—was competent and little more. Is this criticism fair? You would be more forgiving had the wine series retained its original moniker: the St. Clair Supper Club Wine Collector series. It’s a name, you think, that implies the fare served will be drawn from the supper club’s normal menu. (Even the “wine collector” portion does a better job articulating the sort of comparative flights and purchasing opportunities that are actually being offered, rather than robust wine education or a “piece of history”).

“The Alinea Group Wine Series” (though, technically, correct since thedinners have spanned three different dining rooms) conjures images of Alineaitself. At the very least, the name carries a certain with it a certain sort ofprecision, an irreverent attitude, a subversion of expectations. These winedinners were not “Alinea” in any way, shape, or form. To the letter, none ofthe marketing materials for these events ever claimed the food would be anything“more” (or anything at all). You don’t have the slightest problem seeingrestaurants like St. Clair and Roister lead the way with their own creations. Theyactually offer the group a rare opportunity to simply please customers ratherthan provoke them. The menus served at the wine events, however, can only becalled thoughtless. They aimed for and achieved the bare minimum of what wasrequired, showing no particular interest in tailoring the offerings to go withwines that cost many more hundreds of dollars than the price of the food. That,even though the FAQ for the Wine Series page states that “food pairings [are]curated for each experience.” The result was a cynical assemblage of the samestandard dishes—as if someone asked how they can turn a bigger profit at St.Clair without having to put in any extra work. It can only be called an abjectfailure of hospitality, a pantomime of what a wine dinner can be.

Then it dawned on you: commercial events like the Hundred Acre dinnerwould otherwise be hosted at an anonymous steakhouse somewhere in the city. Themenu would feature some seafood, a salad, a steak, some sides, and a tokendessert. Because “serious,” “wine collectors” have the palates of adultchildren, and all the Chicago chefs who appreciate the full beauty of wine’srelationship to food died out a generation ago. The Alinea Group, as it sooften does, rather than taking risks for the advancement of the city’shospitality industry, has chosen—instead—to cynically cash in. They have chosento put together their knockoff version of the “steakhouse wine dinner meal,”drawing on average, existing dishes that could be thoughtlessly cranked out bya skeleton “special” events team.

At only $54.95 per person, the “Alinea’s Steakhouse” menu beingoffered during the pandemic for carry out was far, far better than anythingserved at the $800+ “wine events.” And you have a hard time getting over it.You wouldn’t begrudge the group for choosing whatever wines (or winemakers)they have access to. You could even come to understand that Hundred Acre wouldonly host its “first” event in Chicago unless its marketing operative wasallowed free reign. Perhaps you’d even forgive having him at your table (not tomention the other strangers you were forced to sit with). But, as far as youknow, the Alinea Group operates restaurants. The Alinea Group has cultivated areputation for experimental cuisine. The food at these events did not need tobe “Alinea food.” It could have been crafted in the Roister or even the St.Clair Supper Club styles of more “honest” American cooking. You just wish themenu was crafted at all by someone who worked with the wines and with freshingredients to see how the two might best interact. You wish someone gave adamn, or you wish they would have simply presented you with the usual St. Clairmenu.

You have had several better meals at the supper club ordering your ownfood and ordering your own wine without sharing a table, without being sold to,and without being spoon-fed the illusion that there was anything approaching “wineappreciation” going on. The value proposition of these wine dinners needs to bemuch more clear, for there is nothing markedly “Alinea” about them at all. Theyare an extension of the Group’s brand into the wine world—not for the sake of enrichingcustomers experiences, but simply to grab a piece of the pie. It would beeasier if Alinea could put together tastings of appropriately-aged wines fromtheir cellar. However, their cellar has been mismanaged for quite some time andoffers little of note. Looking at the producers the events have featured, itbecomes clear that nobody of value in the wine world really cares about Alinea,because Alinea doesn’t really care about wine. They might be able to leveragetheir “good name” to trick customers into spending twice the cost of theirnicest tasting menu to go to these events, but they do not care about wine.

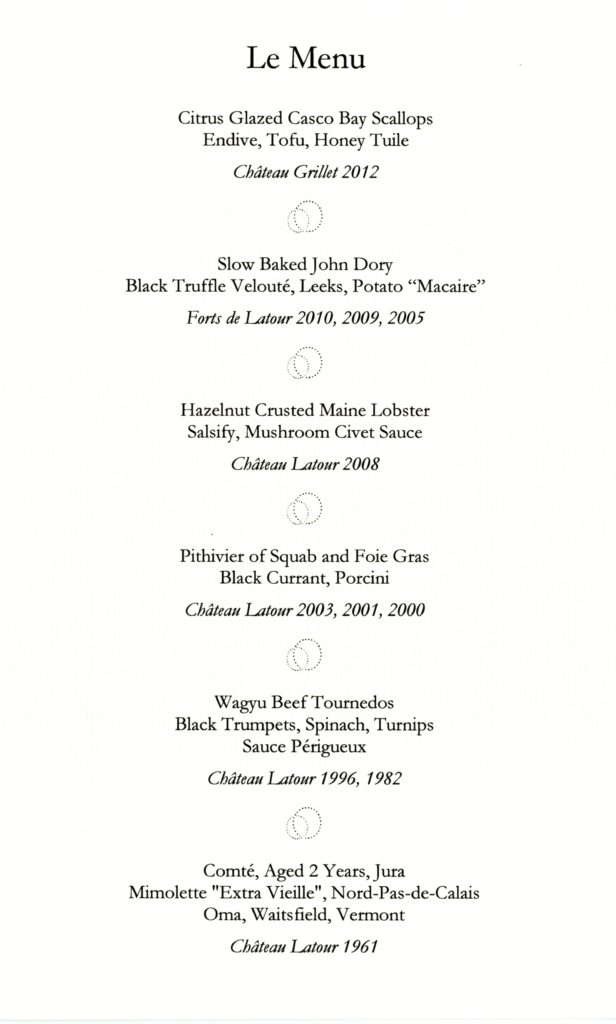

In the final analysis, it is hard not to look back at all four events youattended as a mere cash grab. The wine dinners you have attended in New YorkCity—at restaurants like Daniel, Bouley, Ai Fiori, Del Posto, and NoMad—wereengaging and emotional. The events cultivated a lifelong love of wine, and thechefs present on those evenings made clear how humbly they sought to raisetheir cuisine to the level of the bottles being imbibed. In contrast, yearsfrom now, you would be surprised if you ever remember even attending theseAlinea Wine Series events. They were not only forgettable, but bitterly so too.

For a renowned restaurant group to dip their toe in the water ofhosting wine events after 15 years of operation is commendable. You are morethan willing to forgive any missteps with regards to the space, the seating,the rarity of wines served, and the level of education offered. The latter isparticularly true because Alinea itself has failed to nurture a long-term winedirector, let alone one with the requisite reputation and authority to leadthese events. Having Nick Kokonas go table to table and offer an awkward greetingdoes nothing to demonstrate the group cares about these dinners (particularlywhen he noticeably skips over some parties, like yours). It only serves,instead, to drive home the point that this is all business. It is all branding.It is about being the “sort of group” that puts on “wine dinners” in a weakmarket where they, as usual, will escape any meaningful criticism.

You cannot forgive the fact that a restaurant group holding fourMichelin stars shrunk to the challenge of crafting a truly custom menu forcustomers spending many more times the amount of money of a meal at theflagship. Not only that, they leaned on the most pedestrian offerings out of alltheir concepts, as if the guiding force was “how can we move more of these crabcakes and prime rib?” rather than “how can we accentuate (and pay respect to)these wines?” The Alinea Group did nobody any favors by putting these winestogether—anyone could find and purchase 95% of the bottles that were poured atthe events—instead, the expectation was that they add value onto each evening’sselection. Given they are restaurant group, you would think the food servedprovides an easy opportunity to do so.

For whatever reason, it was just too much for the Alinea Group to handle. You would have preferred a faltering, yet unique, menu to the same St. Clair crap over and over again. It would have shown intention. It would have made the evening special. But Alinea only does what’s best for business, and the end result: a few sad, stuffy evenings at the supper club.