I’ve eaten at Smyth a handful of times in 2025, an amount (however vague) that falls clearly short of the dozens of visits that have characterized some previous, particularly fruitful years of patronage.

This disparity has nothing to do with performance, which has remained true to the “challenging but rewarding” (and, from time to time, unforgettably delicious) ethos that has guided the restaurant’s post-pandemic work. It is also no indictment of the concept’s pricing, which has always been rarefied yet (with the awarding of that third Michelin star) now sits at the very summit of what is charged in Chicago and alongside the most expensive tasting menus in the entire country.

The real reasoning is strictly personal, wholly positive in its nature, and—ultimately—only presents a temporary barrier to business as usual. The silver lining here is that, at least for the moment, I can begin to approach Smyth as something more like an average consumer.

Admittedly, I cannot rid myself of all the past perceptions (that core familiarity with the “house style”) that induce me to appreciate—rather than chafe against—what the chefs are doing. Likewise, I’m not sure I’d ever want to lose the capability to compare the restaurant I know today to the one I fell in love with back in 2017.

However, armed with a bit more distance than has long been the case, I hope to evaluate Smyth’s cuisine with something of a fresh perspective. That means, instead of being acclimated to the menu’s latest creations (and, consequently, focused more on how they have granularly changed), I’ll encounter these dishes with no preconceived notions: no three chances to get things right. I’ll be forced judge them—not just the underlying ideas, but the execution—as any first-time customer, splurging on what should be a life-changing meal, might do.

My goal here is to break from what my longer-form writing on the restaurant has entailed: sweeping surveys, tackled a couple years at a time, that necessarily obscure those moments when all the kitchen’s experimentation proves to be too much. My intention is not to dwell on the growing pains that transform a perplexing or provocative recipe into one that yields singular pleasure. Indeed, nobody has more faith in the fact that Smyth’s process, over a long enough timeline, delivers results that are unlike what anyone else, anywhere in the world, is serving.

But, by tangling with the restaurant in this new, infrequent, comparably bite-sized format, I hope to speak to a starker reality: one that better acknowledges imperfections (and their capacity for disappointment) on the path toward iterative excellence.

Doing so, I hope to engage more constructively with the kind of expectations that a concept at this level and price point carries, to call attention to the gastronomic highs and lows that define any given night, and to place Smyth in closer conversation with some of the other places (like Elske, Feld, Kyōten, Oriole, Valhalla, Warlord, and even Cellar Door Provisions) I have been eating at lately and that have, in their respective ways, come to define the upper echelon of Chicago dining.

The result, if all goes to plan, should be a renewed respect for how and why the team chooses to operate in its inimitable way—along with the kind of admiration that only grows and deepens when one is granted the chance to see their beloved from a novel vantage point.

Let us begin.

Ada Street, more particularly the segment that lies north of Randolph and south of Lake, remains one of West Loop’s most quietly consequential little nooks: the place where, in the shadow of a 14-story apartment building, a world-ranked dining destination plies its trade behind ivy-framed windows.

Smyth’s seeming accessibility—the fact that the kitchen and the dining room can be plainly observed from the sidewalk—has long been its strength. What makes the experience special has never been shrouded in mystery or a sense of exclusivity. No metaphorical velvet rope separates passersby from a world of smoke, mirrors, and luxurious appointments they could not even imagine.

The concept still looks a lot like it did when it could only claim one Michelin star. There’s little—save for the dress of the patrons and the staff-to-guest ratio more broadly (if you are perceptive enough to note them)—that would clue an onlooker in that they are observing one of the city’s finest establishments.

Put another way, anything and everything that makes Smyth great is restricted to the plate, the glass, and the manner of interaction: to those basic constituents of hospitality (the kind that may resist being photographed or broadcast virally) done superlatively well. You won’t ever know them until you’ve tasted and felt them for yourself, so there’s nothing to spoil and nothing to hide.

It matters little that one looks out at that apartment building (which, to be fair, used to be the site of a parking lot) or the passing gymgoers or the canine companions (some of whom have chosen this block as their bathroom) and they look back. It is of no consequence that Small Cheval and McDonald’s form two of the concept’s closest neighbors just up the street.

Smyth, as ever, is at peace with its place in this city and its essential integration into the fabric of daily life. Certainly, there’s a price barrier to speak of, but this meal is no escape. It’s no fantasy that starts and ends when one steps through the curtain. Rather, the team invites the world to view its work nakedly. Earnestly, it asks the audience to free themselves of expectations and open their minds to a gastronomy that brims with complexity yet rejects any artifice.

The risk in doing so—with no focal point of design, no tableside spectacle, no “slam dunk” signature dish to rely on—has never been higher. Nonetheless, by shouldering this burden (which is really just an obstinate dedication to its creative process), the restaurant preserves the spirit of a neighborhood that was rooted in the bloody, unpretentious practice of craft, then reinvented by avant-garde eateries, but now buckles under the weight of tacky chains.

Almost on cue, Smyth’s stretch of Ada has just been transformed into a one-way street flowing north: a sign of persistent westward development that looks to remedy the disfunction and gridlock that has so long characterized the traffic there. (I’ll always recall the cacophony of horns that accompanied one dreadful jam, where two oversized vehicles had squeezed together in such a way that they could hardly avoid scratching each other.)

This part of city made no longer feel like the culinary frontier it once was, but, so long as Smyth and Elske stick to their guns (and so long as places like Creepies and Maxwells Trading can successfully carve out their own niches), it will always form an outpost for the kind of uncompromising, chef-driven concepts that distinguish Chicago from markets where investment (and a kind of grandeur untethered to quality) more readily flows.

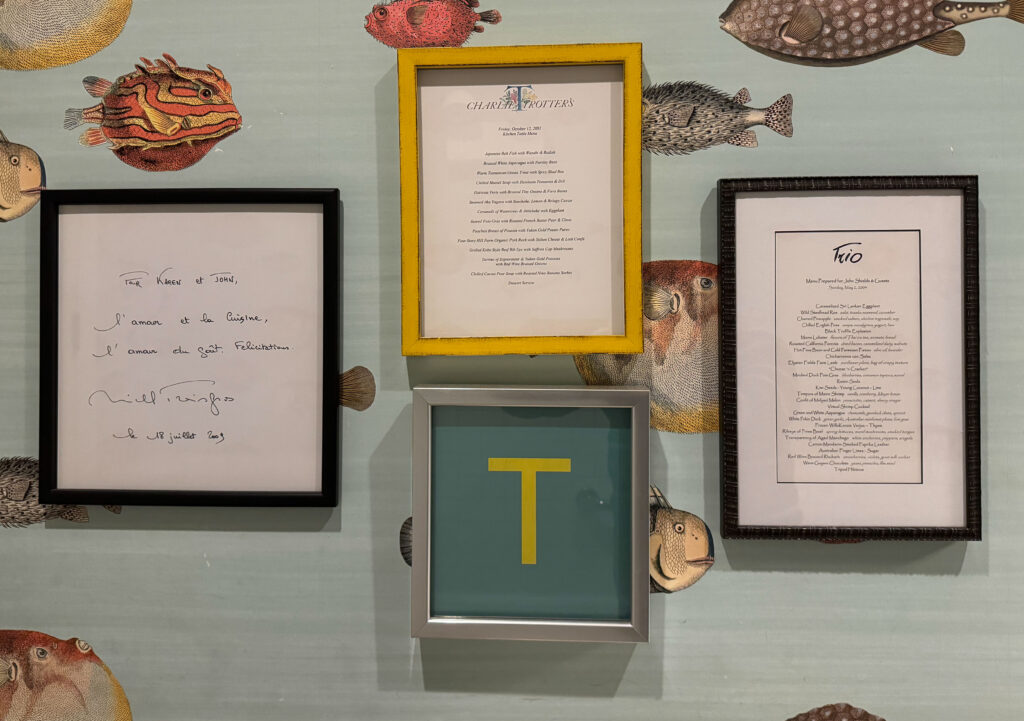

Stepping through the door just a few minutes after opening, I am treated to a set of familiar sights: the wood- and brick-clad dining room, the white-tiled kitchen, the swarm of aproned cooks, a half-dozen vested backwaiters, their dark-suited counterparts, a couple hanging legs of ham, the glow of the hearth, a battalion of glassware, the blank stare of a vintage Bibendum statuette.

The team, as they always do, keep an eye out for anyone coming up the stairs, so that door is actually held open for you with a cheery greeting. The host—and maybe one of the captains or managers—anticipates your arrival, and, after relieving the party of its belongings, they escort you to the table with only a moment’s pause.

Snugly seated, I survey the crowd: finding two groups of two situated at opposite ends of the space. Their kind of punctuality can run the risk of feeling awkward at more intimidating, cavernous venues. But, here, they get to observe Smyth slowly come to life—diner by diner, station by station, and pour by pour all to the beat of ‘80s pop-rock. By my observation, it takes until 7:30 P.M. for the restaurant to reach capacity. This system of staggered seating sees some of the earlier tables turn by 8 or 8:30 P.M., but many (including those choicest “Chef’s Menu” slots) are occupied only once—enabling the kind of flexibility and variable pacing that, however threatening to efficiency, forms a kind of forgotten luxury.

The audience tonight is made up of the white and Asian, middle-aged clientele that one grows accustomed to seeing at temples of fine dining. Many of them are couples: some grouped into double dates and generally (I can tell by the handwritten cards awaiting them) celebrating one of those life milestones that justifies an indulgence of this type. However, I am heartened to see a mother and daughter holding down one of the corner booths. A mixed four-top of business associates sparks jealousy when I spy the bottles of aged Mouton they bring as corkage. A single diner—conspicuously tattooed, her fur draped over the opposite chairs—also makes for a striking sight as she wistfully gazes toward the kitchen holding her glass of wine.

I recall occasions after the awarding of Smyth’s third Michelin star in which the patronage skewed more toward cosmopolitan snobbery and/or content creation than I am used to. Whether these were chance encounters or indicative of a larger trend I cannot say for sure (though it stands to reason that this demographic, nearly two years later, has simply moved on to the next shiny object). This leaves behind a base of customers—some returning, others local (now finally making their first visit), still more traveling to the city (presenting an opportunity to serendipitously take the plunge)—that is unfussy and enthusiastic. No television series or “floating food” is compelling anyone to visit. The promise of excellence, distilled onto the plate, gathers people here, and the corresponding mood—buoyed by the room’s unimposing trappings—feels gracious and warm.

By the time the captain appears to confirm one’s choice of water, the most consequential choice of the evening has already been made. When booking their reservation, guests must choose between the “Smyth” ($420) and “Chef’s Menu” ($550) experiences. The latter promises a “prime time” table, “additional courses,” and the opportunity to meet the “talented chefs”—all in exchange for a ticket price that puts Kyōten ($440-$490, inclusive of service) and Alinea’s upper-tier seatings ($435-$495) to shame. Thankfully, the demise of Smyth’s service charge—controversial because some customers felt pressured to leave gratuity on top of it—means that these values better reflect what you are expected to pay (though not accounting for any conventional, self-directed tip).

Given that the “Chef’s Menu” is only offered twice a night, securing one of these tickets proved rather difficult in the wake of the restaurant’s elevation. Now, save for Fridays and Saturdays (which also are wholly attainable with a bit of planning), the coveted seats can easily be secured.

Personally, it’s hard for me to imagine dining at Smyth and not tasting the fullest, most experimental expression of the kitchen’s work. However, for other consumers, that $130 premium represents a stratum of expenditure with no precedence in Chicago: one that pushes an already expensive meal into the realm (if only in relative, emotional terms) of eye-popping extravagance. Factor in the “Chef’s Menu’s” compulsory wine pairing ($245 or $475), and the total spend balloons to somewhere between $880 and $1,135 per person before gratuity.

This is rarefied air, and I hesitate to tell anyone to commit so fully to a restaurant whose culinary style—at times so polarizing—they may only just be getting to know. Certainly, if someone chooses to plan their reservation far in advance or opt for a midweek (rather than weekend) timeslot in pursuit of this experience, the subsequent expectations would be deafening.

The best thing I can do to guide the public is to present the “Smyth” and “Chef’s Menu” courses from this particular date side by side. Likewise, I will try to determine whether the unique dishes (some of them variants, others additional) provided by the latter (i.e., the “Toasted Corn & Black Truffle,” “Trout Belly Donut,” “Trout Tartare & Roe,” “Smoked Unagi & Matsutake,” “Lamb Sweetbreads & Malted Milk Bread,” and “Vermont Quail & White Truffle”) rank among the meal’s best.

Otherwise, the only real decision of note is what to drink.

The restaurant continues to offer cocktails, beer, and by-the-glass options which, alongside more than a dozen alcohol-free pours, help allay any fear the guests are expected to spend hundreds of dollars on wine. That said, I firmly believe a meal of this caliber and singular style demands that one fully embrace the pleasures of the vine.

This proves to be the case because Louis Fabbrini’s work, as wine director, so effectively and reflexively matches what the chefs do in the kitchen: coming out of left field at times, winking at tradition at others, but weaving diverse producers together by highlighting the shared dedication to craft and iconoclastic commitment to self-expression that connect bottles made by different people in different places in different styles across generations.

I could dwell on the full breadth of Fabbrini’s list, which is now regularly updated online and spans names that are legendary (e.g., Dagueneau, Dujac, Lafleur, Lafon, Méo-Camuzet, Mugneret-Gibourg, Rayas, Rinaldi, Roulot, Roumier, Selosse, Soldera, Romanée-Conti, Vega Sicilia, d’ Yquem), of-the-moment (e.g., Bernard-Bonin, Stella di Campalto, Chanterêves, Ulysse Collin, Ente, Prévost, Roagna, Savart, Stein, Suenen), and downright culty (Cossard, Labet, Maenad, l’Octavin, Robinot, Skyaasen, Steen, Wasenhaus) alike.

Markups range from as much as 145% over retail price to as little as 6% under retail (with a mean of 74% and a median of 86% for my chosen sample of 20 bottles). This means that Smyth, despite holding leverage to hard sell patrons having a “once-in-a-lifetime” dining experience, charges some lowest premiums you’ll see in Chicago fine dining. Of course, a sense of generosity—of celebrating wine’s place alongside cuisine—has always been the norm here. But, in the wake of the restaurant’s third Michelin star, the list has grown to a scale I have never seen without losing its essential spirit. If anything, the selection has been empowered to grow even weirder while never shying away from rewarding traditionalists for whom finding a rare, well-priced Burgundy forms an occasion in itself.

(It’s almost a shame that diners choosing the “Chef’s Menu” are locked into pairings when directing that money toward the list could secure one or two or three superlative bottles. However, fear not, I’ve never found the team to have any problem when guests ask if they can go that route instead.)

Overall, Fabbrini’s work matches the sheer breadth of a peer like Alinea while also discounting its chosen products (or really just refusing to be greedy) in a way that reminds me of what I like so much about Oriole. But the real beauty of the program comes in its depth: in that latter category of producers I associate more with venues like Cellar Door Provisions, Elske, and Obélix than I do the city’s glitziest tasting menus. By prizing “natural” methods across regions old and new—by making space for expressions of craft that are a little esoteric while never tolerating flaws—Fabbrini is effectively dragging Chicago’s wine culture into the future while occupying a position, at the very top of the gastronomic pyramid, in which his efforts can hardly be ignored.

To be clear, it’s not about forcing anyone with well-formed tastes to drink natural wine. Pay the corkage ($100, one bottle limit per two guests) and drink your Mouton or, otherwise, choose from the ample, affordable options that express typicity.

No, by wielding these stranger selections with a steady hand, Fabbrini widens the conversation surrounding what wine, from a particular places and grape, should evoke. He fosters a kind of enjoyment (untethered to convention or expectation) that, again, perfectly echoes what’s coming out of Smyth’s kitchen. He’s clearing the way for a new demographic to perceive and appreciate wine on their own terms—something, no matter how anchored one’s taste is to the legends of the past, must form an essential part of this industry’s survival.

Given that browsing the list is, in itself, a signifier of one’s familiarity with wine, Fabbrini’s work is best judged at the level of the pairings: those turnkey solutions that allow diners to sit back and enjoy a curated, harmonizing experience without the risk of choosing wrong.

I’m loathe to order a pairing just about anywhere (relinquishing funds that I could direct toward my particular tastes), but I always get one here. I cannot really speak to what the entry-level “Smyth Pairing” ($245) offers—and, indeed, this must be the one that the majority of customers find themselves drinking. Nonetheless, in breaking down the “Super Mega” ($475) selection, I hope to provide a window into what is comfortably the city’s most expensive offering of its kind: coming in ahead of Ever’s “Cellar Wine Pairing” ($345), Oriole’s “Reserve” ($350), and Alinea’s “The Alinea Pairing” ($395). Plus, I think the philosophy guiding the restaurant’s two levels of vinous indulgence remains consistent.

Tonight’s lineup is as follows:

- 2011 Roses de Jeanne Champagne “Côte de Béchalin”

- 2013 Weiser-Künstler “Enkircher Ellergrub” Riesling Spätlese

- 2013 Les Cailloux du Paradis “Evidence”

- 2018 Clos de la Bruyère “Autochtone”

- 2021 Hiyu “Falcon Box”

- 2021 L’Anglore “Sels d’argent” / 2023 L’Anglore Tavel “Prima”

- 2011 Antica Terra “Ceras” / 2015 Comte Georges de Vogüé Musigny

- 2016 Lorenzo Accomasso Barolo “Annunziata” Riserva

- 2023 La Stoppa “Vino del Volta”

- NV Le Citron du Roulot, Nikolaihof Höllerblutensirup, Black Mint

At first glance, some of these producers (especially those that do not fit neatly into popular appellations) may seem scary. That is to say, one always wonders for a pour or two if they’ve been tricked into spending a higher sum without receiving and corresponding increase in the quality or value of what is being served. Nonetheless, Fabbrini has always demonstrated his genius by using “lesser” (though unique, characterful) bottles to balance more traditional selections that shoot for the stars.

Tonight, the middle section of the pairing is undoubtedly the most adventurous. The “Evidence” (a botrytised, oxidative Menu Pineau) is matched with caviar and followed by the “Autochtone” (a riper—but still nutty—Romorantin made by the previous vintner’s son), which is poured alongside the latest preparation of avocado. These are challenging wines even for me but not totally beyond the pale. They also benefit from aging, a certain internal logic (the family resemblance), and a storytelling dimension that are anything but rote.

The ”Falcon Box” (from Oregon-based Hiyu) is faced with the unenviable task of substituting for pricey Chardonnay. Fabbrini frequently favors this producer, but this particular cuvée might be the best: a field blend of Burgundian varietals that mimic the texture and tang of the region’s cultier biodynamic estates. Opposite trout, the wine shows quite well. So, too, do a pair of pours from L’Anglore (the former a Grenache Blanc, the latter a Rhône rosé) with a presentation of smoked eel and mushroom. The wine director has gone to great lengths to source these latter wines (engaging as many as four different purveyors in the process), and, whatever one thinks of their chosen style, it’s a privilege to taste them.

It is on this foundation of more natural, challenging offerings that Fabbrini can absolutely blow his customers away with items like a mature Cédric Bouchard Champagne, a side-by-side of Willamette and grand cru Pinot Noir, and a top vintage of Barolo from a dearly departed master. These are bottles that cost $300, $400, or even $800 at retail, and the pairing is able to sprinkle them in—offset by those obscure producers—in a way that is sure to impress lovers of sparkling and red wine whose tastes lean more conventional. They impress me too, for the age and rarity of these selections (none of which are available on the full list) transcend any “natural” vs. “traditional” dichotomy.

Even the Spätlese (touting more than a decade of cellaring in its own right), the “Vino del Volta” (a freshly sweet, appassimento-style Malvasia di Candia), and the quasi-cocktail made from Roulot’s lemon liqueur are all but certain to please.

Like Smyth’s cuisine (at its best), Fabbrini knows just when to provoke and just when to reward. Frequently, one is left feeling amazed when faced with either side of this equation. Once one realizes how fleeting—how filled with one-off bottles and tuned to the rhythm of the chefs’ own dynamism—each of these parings is, that sense of amazement only grows.

I don’t know of any wine director in Chicago who works as hard, in such relative obscurity, with the same burning devotion to an aesthetic, gustatory experience that is already so misunderstood in its own right. (There is someone working down the street who comes close.)

Ultimately, Fabbrini is the kind of partner in taste that any three-star property would be lucky to have. Now a couple years into the job, he has shown no sense of slowing down either. Rather, his program only gets better: deeper in its convictions, more dizzying in its breadth, but never out-of-touch with what a mainstream audience needs to leave happy. In that sense, the wine director has come to emblematize and, in turn, define Smyth more than anyone who has held the role before. Whatever one thinks of the restaurant’s cuisine in this post-pandemic era, there’s no question that the list and the pairings have become world class.

Service, whether centered on wine or food, proceeds in the same fashion that has always characterized Smyth: delivering an exhaustive (almost comically exasperating for some) level of detail in a canny, self-aware manner.

It’s hard for me to step into the shoes of someone, whether they are new to fine dining or just to this restaurant’s peculiarities, who might view these spiels as something close to an alien language. (Even some of those natural wines go well beyond the limits of my knowledge.) But I crave the performances (whose terms and techniques, by now, are surprisingly legible even if novel ingredients continue to pop up from time to time), for they so clearly demonstrate how well the cooks, captains, sommeliers, and managers alike have internalized the full complexity of the cuisine. Their fluency, frankly, is unerring (I’m probably one of the rare people who could recognize a flub), and it’s only by connecting their descriptions to my visual processing of a given dish that I can hope to say anything of note about how it eats.

There’s also something pleasingly holistic—even inspiring—about the fact that the kitchen’s work, however arcane, is treated with a kind of shared ownership by the entire staff. These recipes are not precious science projects that have been kept under wraps in some faraway sanctum. They’re presented as a natural extension of the open, hybrid space the team occupies and the flow from nature to cultivator to chef, server, and customer that seasonal cooking is centered on. (Back during Smyth’s pre-pandemic collaboration with The Farm, the farmer himself might even be eating at the table next to you.)

I’ve been the guinea pig on more than one occasion when a backwaiter, unexpectedly, is thrown into the lion’s den and asked to describe a course as their captain walks away. These most junior members of the front of house never shrink before the pressure, tackling their surprise assignment with a bit of uncertainty but otherwise nailing all the essential points. This a testament to how well even those on the floor who have no expectation of reciting such information are retaining it—how an understanding of and appreciation for the cooking being done extends even to those who are left clearing empty plates.

More generally, the backwaiters remain highly conscientious about their work (placing utensils, refilling water, escorting guests to the bathroom, folding napkins in anticipation of their return). However, these efforts—the building blocks of any excellent restaurant experience—do not preclude moments of candor or curiosity. These figures, with beaming smiles, appreciate your appreciation whenever it is verbalized. They also take the time to solicit feedback about the food: not in a way that feels wary or robotic but, rather, one that reveals their obvious pride.

Moving up the chain of command, the captains and sommeliers are understandably granted greater opportunity to joke around, make small talk, and search for that thread of conversation that transform an otherwise transactional, explanatory relationship into something more emotionally grounded and even profound. Yet it goes without saying that anyone in any role here, should some kind of genuine connection or spirited conversation arise, is supported by their coworkers in a way that allows them to remain engaged with the given party.

This kind of “lingering” has long formed a core part of Smyth’s hospitality. Time after time, it proves the point that the restaurant, however bravely it conceives of its menu, exists at guests’ disposal. All its resources are channeled toward shaping an experience that is precise but comfortable, ever-flexible, and capable of transcendence when all the constituent elements (diners included) come together in the right fashion.

Chris Gerber built this culture over the course of his eight years at Smyth. The real test, following his departure in September, will be if that legacy survives. However, I’ve already seen it propagate through successive generations of staff. I’ve already felt it burn just as brightly in the general manager’s absence. And, with the spearheading of the restaurant’s hospitality now entrusted to Cara Sandoval (perhaps the only person in contemporary Chicago dining who has done work of the same caliber), I have every expectation that the restaurant will safeguard the warmth, charm, and devotion (above and beyond the guardrails that define old, staid fine dining) that have always made Smyth a standard-bearer of modern, enlightened service.

At last, the meal begins.

And it does so on a familiar note: with a tableside pour of “Amazake,” ever-changing in its composition, that immediately anchors guests’ palates in the flavors and feeling of the moment. (This is accomplished, in part, by the presentation of the drink’s constituent ingredients—including the otherworldly kōji mold used for its fermentation—on an accompanying tray.)

Tonight, the amazake is infused with quince and honey then blended with French mead and junmai daiginjō sake. This eclectic combination sounds it could veer toward sickly or boozy excess. However, the pour (served over a sphere of ice in an attractive ceramic cup) delivers engaging freshness on entry with milky weight and nuttiness on the midpalate and a pleasing semi-sweetness on the finish. Overall, this makes for a beautiful, crowd-pleasing tipple—one I think ranks among the best of its type Smyth has yet served.

With diners now mildly lubricated, the segue into actual food is accomplished via a trio of opening bites that are presented in a staggered sequence with one- or two-minute delays between them.

First up is the “Dungeness Crab & Kakai Pumpkin,” which might best be understood as the latest iteration of the kitchen’s longstanding work with tartelettes (both savory and sweet). The current rendition lands somewhere in the middle: combining a shell made from the titular gourd (a small, Austrian variety) with a filling made from the seeds, some finger lime, red ribbon kelp, and shreds of meat drawn from the headlining crustacean.

Texturally, the tartelette blends a gossamer (but appropriately brittle) base layer with moist, melting crab and subtle pops of seed and citrus. The sum effect feels totally cohesive, and the resulting flavor—sweet, nutty, faintly earthy/briny, and enlivening in its tanginess—aims straight at pleasure. It also matches the notes of the “Amazake” beautifully, making for a seamless transition that also cleanses the tongue for what comes next.

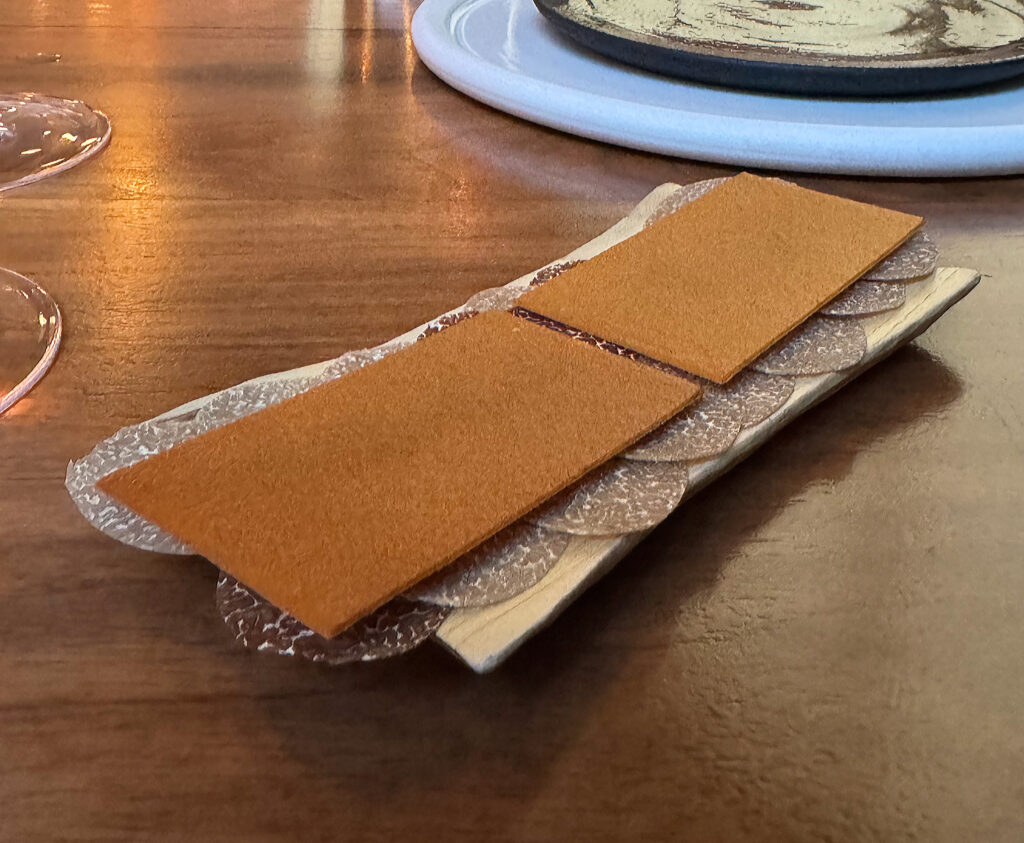

The ”Toasted Corn & Black Truffle” is also immediately recognizable to me, for it falls within a series of slender, wafer-like preparations the chefs have been playing around with for years. Technically, the desired sensation is something like the total flattening and homogenization of the bite’s mouthfeel. At the same time, the kitchen looks to match this corresponding meagerness with an absolutely explosive intensity of flavor.

Visually, it’s hard not to marvel at how eye-catching those Italian truffles (actually a blend of black and white)—cut into perfect coins and gently arranged in a four-by-four grid—look when tucked between the two rectangular layers. Merely holding the morsel in one’s fingers and admiring its daintiness from different angles provides an immense thrill. Yet, upon reaching the palate, this wafer affirms it is more than good enough to eat. Indeed, the snap of the toasted corn cracker and its truffle filling is impeccably clean and delicate. Moreover, a hidden layer of fava bean miso ensures that the hauntingly earthy, nutty tones of the starring ingredients are matched by a sweet and richly savory notes that drive the preparation toward staggering decadence.

Yes, the chefs are not shy about giving their headlining ingredient (so often treated with kid gloves) a much-needed boost. Overall, this makes for one of the best items of the night: a doubly indulgent expression of truffle that transcends its luxurious appearance and reminds you why, exactly, the totem is prized in the first place.

A ”Trout Belly Donut” serves to complete the sequence, building on past examples of the form (which have featured smoked eel as of late) going all the way back to the original, hallowed “Brioche Donut” served during Smyth’s pre-pandemic era. The present version centers on a Munchkin-style orb that has been filled with a squash purée. A leaf of radicchio, streaked with yellow, orange, and red hues, comes draped over the top while the titular cut of fish—hanging perpendicularly in the other direction—benefits from a period of curing in sake lees.

As the scale and ingenuity of these donuts continue to grow, the baked good transforms into more of a vessel than the main event. Tonight, it offers a vaguely flaky, then fluffy mouthfeel with a gooey, creamy interior that emphasizes the earthy, nutty side of the gourd rather than its sweetness. To that point, I’m not sure the donut would impress if served on its own (though, if that were the case, it would probably benefit from some sticky glaze that would bring it into balance). Instead, it offers a foundation of warmth and richness upon which the crunch of the radicchio and the slick, yielding texture of the trout belly can come together.

Despite being comparably raw, the two ingredients meld in a manner that is rich and soothing, with the fish’s latent fat and umami beautifully contrasted by the chicory’s bitterness and tang. Ultimately, it’s a little hard for me to sense what exactly the donut provides that some other vessel (or a simplified, plated presentation) could not offer. However, these disparate elements still somehow work together (I think in part due to the sweetness imbue by the sake lees) even if I still dream about tasting the original “Brioche Donut” again.

The first proper, composed course of the evening embraces a winning combination of “Maine Lobster & Uni.” However, Smyth is never content to let seafood like this—however cherished—stand on its own. Indeed, by sourcing the sea urchin from Maine (rather than splurging on a tray from Hokkaido that may or may not deliver), the kitchen gets to put a much stronger imprint on the coveted gonads. To do so, they draw on fermented pineapple, a lobster custard, Virginia peanut milk, walnut oil, and squash purée (the latter, by now, having established itself as one of the recurring themes of the meal).

Texturally, the starring crustacean (arriving “barely cooked”) displays a soft, almost gelatinous consistency I find superior to all but the best butter-poached examples. The pieces of lobster, opposite the custard made from the same ingredient, melt into the uni and take on the flavors of the surrounding condiments. Surprisingly, it’s the milkier, more vegetal notes that take the lead. For whatever reason, the fermented pineapple, despite my high hopes, is hard to pick out, and the sea urchin itself seems lost in the shuffle too (though at least that means any jarring irony quality has been avoided).

When the elements combine, only the barest sweetness comes to the fore. Yet, with a sip of Fabbrini’s pairing of aged Spätlese, the recipe explodes: the intensity of the walnut oil finding itself beautifully delineated and the long, buttery, subtly sweet character of the lobster being finally revealed. Even the tangy and fruity tones of the pineapple, so well echoed by the Riesling, are finally discernible. Overall, the uni could still probably be expressed more clearly here, but I find—largely thanks to the wine—plenty of intellectual and hedonistic appeal just below the surface.

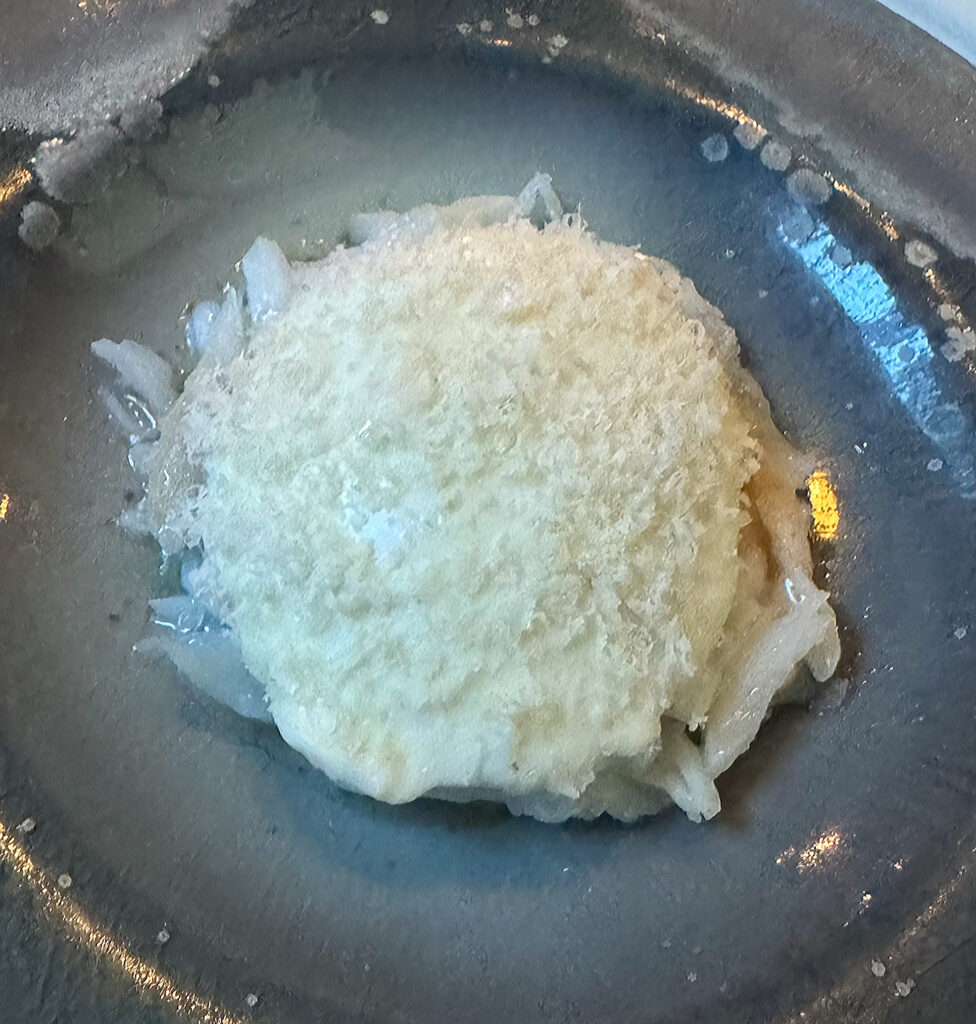

Arriving next, the “Caviar & Pumpkin Seed” represents the latest version of what has, throughout 2025, established itself as Smyth’s latest and greatest method of serving the prized sturgeon roe. The recipe presents something of a clean break from the “Hot & Cold Kaluga Caviar” and “Caviar & Almond” compositions that have predominantly featured during the period from 2021 to 2024. Those preparations favored sticking a healthy scoop of the eggs to the side of a bowl featuring the same kind of nut oils and nut milk (along with preserved nuts, fudge butter, and housemade nocino) just seen in the “Lobster & Uni.”

By comparison, the “Caviar & Pumpkin Seed” centers on an equally generous serving of roe (Kaluga now sourced from N25) juxtaposed by alternating pockets of blade kelp and cured sea lettuce that have been stuffed with pumpkin seed butter and pumpkin purée respectively. A sabayon of blue banana squash and some parsley oil (both applied tableside) complete the presentation: one that brightens its palette of green tones with a burst of creamy orange.

On the palate, the caviar itself feels smooth and somewhat clumped together but strikes with a faint, tongue-tingling pop. The resulting sensation blends well with the lusciousness of the sabayon and holds its own against the seaweed pouches, which (despite their rich fillings) display a degree of chew and gelatinousness that contrasts the other textures at hand. To be honest, I’m not sure the mouthfeel of the roe is really being safeguarded here. Rather, its naturally nutty, buttery flavor is both amplified (through the expressions of gourd) and accentuated (via the brinier, umami notes of the kelp) in a manner that feels fuller and more layered than any conventional caviar preparation. Indeed, I most enjoy tasting the subtle variations on a theme that are revealed as one engages with the different squash/pumpkin components. The result feels intellectual without being challenging, but I’m not sure the experience of the dish (at least at this stage) is quite as seamless or soothing as those that preceded it.

The ”Avocado & Turnip” tells a similar story, entering into a long sequence of courses (starting with the “Chilled Avocado” and spanning versions like the ”Avocado & Habanada Slushie,” “Avocado & Garden Curry,” “Avocado & Fig Leaf,” “Avocado & Eucalyptus,” and “Avocado & Pistachio”) that have defined the team’s work in the post-pandemic era. It might even be fair to say that this seeded, savory fruit has formed the totemic ingredient of the restaurant since 2021—so distinctively and consistently has it featured on the menu.

The present interpretation of avocado sees it sourced from San Gabriel and buried (somewhat uniquely) under a layer of salted cream. Shreds of the titular turnip, some almond, and more of that Dungeness crab meat from earlier complete the presentation, whose white-on-white effect stands as a complete departure from the verdant bowls of the past.

Texturally, the avocado comes across as a touch firm but ultimately turns rich and melty with further mastication. The overall coldness of the dish, which serves to preserve the consistency of the seafood and the salted cream topper, seems to play a part in the fruit’s hardness too. However, I think this serving temperature actually works to mute the recipe’s flavors, for, other than a whisper of sweetness, I am left tasting nothing but a pronounced note of salt. Certainly, I can imagine how these various components (peppery, nutty, and backed by luscious crab) might come together to enliven the avocado. But, tonight, it’s hard to sense any depth or nuance here.

The “Rainbow Trout & Pineapple” that arrives next also references a series of recipes from the past: namely, the “Rainbow Trout & Koji Rice,” “Rainbow Trout & Blade Kelp,” “Steamed Brook Trout,” “Brook Trout & Truffle Porridge,” and “Brook Trout & Horseradish” preparations that featured during 2023 and 2024. The kitchen’s preference for the fish becomes clearer once one hears that it’s being sourced from Virginia (that very namesake and crucible of “Smyth”). Nonetheless, it’s good eating too, and accompanying notes of sea urchin (used to form a crust over the fillet’s exterior), fermented pineapple, rhubarb-stuffed nasturtium flowers, calamansi, and a serving of the roe sac totally reinterpret how the ingredient has been treated before.

While the preceding dish was characterized by being a little too cold, this serving of rainbow trout actually opts for a temperature that is surprisingly lukewarm. This choice actually helps to amplify the profound butteriness of the fish (which, quite literally, is eaten with a spoon). However, when it comes to flavor, this tepid condition seems to emphasize a certain astringency (likely drawn from the flowers) that competes with all the sweetness, tang, and complicating funk I actually find quite appealing. Yes, unlike the earlier “Maine Lobster & Uni,” the sea urchin and fermented pineapple are actually rendered quite clearly here. They’re just obscured by that jarring bitterness, and the trout itself—so wonderfully gooey—falls short of its full potential.

A sidecar of “Trout Tartare & Roe,” the latter cured with melon and paired with a melon custard, suffers from a similar fate. The textures here, marrying melty flesh and a pleasing pop, are totally sound. Yet, other than a hint of cucumber, the resulting flavor is marked by a resounding bitterness that robs this cute ramekin of any pleasure. Could all the astringency actually have something to do with the roe that appears in both components of this course?

The ”Smoked Unagi & Matsutake” promises an immediate redemption. After all, this fatty freshwater eel (sourced from American Unagi) has long formed a winning presence around this midpoint of the meal. Preparations like “Maine Unagi, Lima Beans, & Ham,” “Maine Unagi & Blade Kelp,” and “Eel Doughnut” (served during 2023 and 2024) have reliably set the stage for the actual animal protein to come. And the present iteration—incorporating Carolina rice porridge, geoduck, muscadine grapes, and Malabar spinach—pairs the fish with a more varied, comprehensive range of ingredients than I have ever seen.

On the palate, the eel displays an even more effusive, succulent mouthfeel than the excellent rainbow trout, and the service temperature here—firmly on the warm side—adds to a feeling of sustenance. Opposite the fish, one finds the tongue-coating porridge, the plump pieces of fruit, and the fleeting snap of both the matsutake and geoduck (the latter being sliced to an expert degree of thinness). Texturally, these ingredients harmonize, but it’s hard to see how the flavors—veering from florality to tang to a kind of Pine-Sol herbaceousness without much leavening sweet or savory structure—fit together. Maybe it’s fair to say I do not find the kind of convincing satisfaction here that I typically associate with unagi (no doubt subconsciously influenced by what I’m served Kyōten). Nonetheless, others at the table enjoyed this more, and I think the recipe (boasting such an enjoyable mouthfeel) consciously aims at the more challenging end of intellectual appeal. I certainly would not mind sampling it again.

On cue, a preparation of “Lamb Sweetbreads & Malted Milk Bread” looks to tilt the meal even further toward carnivorous delight. Yet it does so rather gently, with the trout, the eel, and now this serving of offal (cultivated from the thymus and pancreas glands) successively increasing in weight and richness without losing the essential delicacy that binds these diverse proteins together. Truth be told, sweetbreads might be my favorite ingredient, so seeing them embraced by the kitchen (as done irregularly throughout 2023 and 2024) is a particular treat. Relative to the “Elysian Fields Lamb & Malted Milk Bread” served as part of the regular “Smyth” tasting, this course represents an instance in which the pricier “Chef’s Menu” opts for a smaller, more unique cut from the same animal.

Presented opposite a surrounding thicket of leaves, the offal (draped in a piece of puntarella) forms the centerpiece of a transfixing autumn tableau. The other condiments at hand—marmite and a velvet horn (seaweed) jus—keep things simple, allowing the supreme tenderness and clean, sinew-free texture of the sweetbreads to shine. Of course, they maintain a trace of structure (which, compared to the preceding servings of seafood, makes the ingredient discernible as meat). And the resulting flavor, balancing the bitterness and sharpness of the chicory with an immense degree of brine-washed umami, is just superb. In short, this diminutive piece of thymus provides all the satisfaction I was searching for from the last few plates. It ranks as one of the highlights of the night.

The accompanying “Malted Milk Bread” has become a familiar presence by this point, and it was always going to (and will continue to) suffer in comparison to that original “Brioche Donut.” The team has continually tinkered with the baked good’s toppings over the years, and I’ve increasingly been left feeling that it’s too sticky, too sweet, and almost acts to counteract all the carnal indulgence it is served alongside.

Tonight, however, I think that the bread’s glaze is perfectly judged: imbuing the fluffy crumb with only a hint of sugar that actually drives the nutty, toasty undertones of the recipe toward a maddening, liminal sweet-savory balance. Yes, on this occasion, I treasure every bite—thinking that maybe I can get over the retirement of the “Brioche Donut” after all.

Whether one enjoys the lamb’s loin or its sweetbreads for the preceding course, everyone finishes this segment of the tasting in the same way (well, almost). Vermont quail forms the starring ingredient: having featured in a range of preparations (like “Hearth Roasted Quail Leg,” “Whole Roasted Quail & Chestnuts,” “Vermont Quail & Malted Milk Bread,” and “Vermont Quail & Boudin Noir”) going back to 2021. Here and now, it goes by two names: “Vermont Quail & Sprouted Grains” (for those choosing the “Smyth” experience”) or “Vermont Quail & White Truffle” (for those enjoying the “Chef’s Menu”).

The core idea remains the same, and, honestly, it’s quite like the “Vermont Quail & Boudin Noir.” Meat from the bird’s breast is stuffed with guinea hen and paired with a slice of blood sausage, the titular sprouted grains, some oregano flowers, and a sauce of quail and plum. First-of-the-season white truffles, for those lucky enough to encounter them, are then shaved over the top.

Texturally, this yields individual bites of the meat that are firm on entry yet turn tender and juicy with further chewing. The boudin noir (rich, plump, but unerringly homogenous) and explosively crisp grains gently contrast the breast in either direction. The truffles, in turn, are almost hard to sense at such a gossamer thinness. Yet their pungent fragrance (surely a sign of quality) enlivens the latent umami of the hen-larded quail, charging the sweet, nutty, and more darkly earthy notes found on the plate with that mushroomy, garlicky X-factor that helps the bird—a wee portion brought to the height decadence—sing. What a beautiful expression of game and a benchmark, gloves-off utilization of white truffle to boot. I certainly appreciate Smyth’s work with wagyu when it shows up, but I don’t ever see why the kitchen would favor beef when they can source fowl of this quality.

A ”Tempura Quail Leg” served on the side (having debuted toward the end of 2024) is nothing new. However, coated in an accompanying foie gras dip, the bite brings a flaky, crumbly mouthfeel and some salty, semisweet flavors to the fore that all harmonize nicely with the main event.

The “Black Walnut Cured Quail Egg” that also joins this final savory course is more controversial. This ingredient has featured countless times over the past few years (often appearing at the very beginning of the tasting). In truth, whether tucked into a tart shell or topped with caviar, it’s always been a bit challenging too. The present version, crowned with a truffle slice (in this case black) of its own, is served fairly simply but strikes my palate as too cold, gelatinous, and sweet. It actually leaves me feeling queasy, which maybe signals it’s not a good match for the two warmer presentations it joins on the table.

The turn toward dessert feels a bit like déjà vu—given the fact that an opening “Cadbury™ Quail Egg” so directly references the bite I just struggled to stomach. Still, plucking this piece (painted for a truly lifelike effect) from its grassy perch is charming, and the resulting sensation—the brittle shell revealing tangy citrus blossom curd and richly sweet egg yolk caramel—makes for an effective palate cleanser. On reflection, the candy egg almost tastes like a lemon bar. Yes, items like this demonstrate Smyth’s playfulness (especially when it comes to naturalistic motifs) at its best.

Another nibble titled “Yogurt Mousse & Quail” looks to extend the effect (while looking a bit like a chocolate cookie). This black malt tuile actually obscures a quail jelly, some sweet quail mousse (blended with the aforementioned dairy), and a reduction of toasted buckwheat and barley. It hardly sounds appetizing, but the combination of crunchy and creamy textures with a backing of tangy, roasted, nutty, and sweet flavors (tinged with an echo of the bird’s intense umami) cannot be denied. In short, this is another great transitional bite.

A preparation of “Satsuma Mandarin & Ginger” forms this menu’s principal dessert, and it comes presented (alongside that Le Citron du Roulot cocktail I mentioned earlier) on a neat wooden tray.

The recipe centers on a halved segment of the titular citrus that is filled with a ginger sorbet and further dressed with the mandarin’s flesh, juice, and zest. A sugar tuile layered over the top provides some contrasting crunch, one that frames a creamy, chunky set of textures that strikes with pronounced acidity and spice. Though undeniably bright, the dish takes on a wonderful depth of sweetness and florality with the introduction of the accompanying liqueur. I’m always one to want chocolate or caramel in this headlining position, yet the recipe actually anchors the meal nicely.

Indeed, when the closing trio of petit fours arrives next, my first thought is that dessert proceeded too quickly with too little decadence. Thankfully, these closing bites are anything but afterthoughts.

A “Preserved Kombu Tart” enters into a longer tradition of offerings (like the “Kombu & Dark Chocolate Tartlet” and the “Jasmine & Kombu Tartlet”) while blowing them totally out of the water. The key here is the addition of a pistachio praline that, in combination with some chamomile custard, bursts through the crumbly shell and supercharges the sticky, savory-sweet seaweed with a profound nuttiness. (I’m talking Obélix “Pistachio Croissant” levels of concentration!) Though I’ll acknowledge I have a weakness for the chosen nut, it is so boldly, effectively utilized here: making for what might be the best petit four I have ever encountered.

The ”Pumpkin Pie” served alongside it (also taking the form of a tart) is not far off from the same level of quality. Though its predecessor is relatively direct and crumbly in its expression, this bite aims at a creamier, airier effect courtesy of some spiced milk foam. Nonetheless, the pumpkin seed sablé tucked inside the shell delivers a kindred intensity of flavor—one that marries its striking nuttiness with warmer, autumnal tones that cannot help but stir nostalgia. Taken as a pair, these tarts represent some of the pastry department’s finest work in recent memory.

Lastly (and served separately), one finds the “Bittersweet Chocolate & Maitake Mushroom.” On paper, this seems set to be the most challenging of the bites—marrying a chocolate wafer, a gooey chanterelle ganache, and a crowning layer of that candied maitake. However, on the back of so much nuttiness and citrus (throughout not just dessert but the entire menu), it’s nice to end on a robust note of cocoa. Surprisingly, that element takes the lead here: caressing the tongue and carrying through to the finish, where the pair of mushrooms do nothing more than provide some fruity, earthy depth that harmonizes effortlessly with the dark chocolate. Overall, this may be the weakest bite of the trio, but it’s also one that remains impressively approachable despite its novelty.

Three hours, 12 courses, and 21 dishes later, the “Chef’s Menu” draws to a close.

When I consider that similar experiences have easily broached three-and-a-half or four hours in the past, I leave this meal feeling stimulated—maybe even inspired—rather than bogged down by the heaviness that comes when one is left taking too many sips of wine between servings.

If I count the time between the arrival of the “Amazake” and the final presentation of petit fours, the menu clocks in at something closer to two-and-a-half hours: what I can only term expert pacing (the equivalent of a course every 13 minutes and a dish every seven)—an efficiency that is no doubt influenced by my own rate of eating.

I have no fear that any party needing an hour longer (or more) to dine will ever be rushed here. Rather, in an era when even the most trifling tasting menus (hell, even a proportion of trendy à la carte spots) run closer to three hours than two, it’s refreshing to see a team operating so precisely. They may be crafting a cuisine that feels exponentially more layered and complex (at a corresponding premium price) than any other kitchen in Chicago, but the chefs, cooks, captains, and backwaiters do not allow the intellectual heights of their work to overshadow the essential rhythm of eating.

Food comes hot (or cold, or lukewarm) and fast. Words and ideas swirl. Some mouthfuls delight. Others confound. Yet there’s no time to stew on any miscue. (One even struggles, when offering feedback, to recall those bites they did love). The next pour of wine has appeared in the glass. The next perception awaits.

Smyth is Chicago’s leading laboratory of taste. It’s one of precious few places in the country or even the world that an experienced diner can say is forging new ground in the purest terms of texture and flavor. Without recourse to any glamorous setting or presentational tricks, the restaurant speaks with conviction—and a clear vision—solely on the plate.

In fact, it is the essential comfort of the space, the warmth of the service, and the surprising value of the beverage program that allow each dish to strike with such clarity. For better or worse, they have no place to hide.

The ups and downs that any given menu, at any single moment in the year, might entail does not accord with conventional expectations of “three-Michelin-star dining.” But I can tell you that this push-pull process of challenge and reward will never get stale. It will never feel dated. It will go on for as long as it has creative souls to sustain it, and the resulting fruits—however polarizing, however seemingly unconcerned with a rote kind of pleasure—will from time to time include some of the greatest things you’ve never eaten.

When you pay the bill (which, again, I should mention is now free of any service charge) and prepare to walk out the door, I suggest you save those parting “Seaweed Caramels” (themselves a totemic offering by this point) for later.

Consumed in the immediate aftermath of the meal, the sticky, briny, umami-charged confections feel like overkill—the hammering home of a sensation (pleasurable, though only strangely so) that has been all but exhausted by the evening’s courses.

Yet, enjoyed in the afterglow of the tasting menu (whether later that night or the next day), the caramels’ meaning becomes clear: a final whisper from a singular voice whose quality may only be totally understood with repetition and reflection.

Sentiment aside (for, no matter how much I might wax poetic, I must also be Smyth’s most honest critic), this was very much an archetypal meal: one that did little to soothe diners who, dispositionally, disagree with the path the kitchen has taken after the pandemic but, for anyone receptive to their work, delivered notable growth and a few new favorites.

That said, I cannot easily step into the shoes of a Chicago diner who carries the expectation that the restaurant will equal their three-star experiences at Alinea, Grace, or L2O and leaves disappointed. Admittedly, I’m also not quite sure if I can convince someone who totally adores Oriole that spending 30% more to get through the door here will yield a corresponding increase in pleasure.

It’s almost from a global standpoint that Smyth makes sense—as an island, an outpost, an uncompromising expression of two chefs’ proclivities that is taken to an extreme through the collaboration and mentorship they foster. The experienced international diner, because they have sampled so many tasting menus in so many places and immediately recognize the common tropes, is prone to appreciate what makes this concept unique.

After all, is it not better to be strangely captivating than it is to please, however reliably, at a level that is more or less anonymous when viewed from a wider perspective? Or do well-traveled patrons tell themselves, “Smyth is surprisingly good for Chicago, perhaps even hard to compare to any other concept, but why shouldn’t I fly to Copenhagen or Tokyo or San Sebastián in pursuit of cuisine that is just as singular yet even more elaborately, romantically rendered?”

This game—of trying to put Smyth’s polarizing work in the right context—is really not worth playing. It does a disservice to what is essentially a personal, artistic culinary expression that, even if it’s idealistic to say so, should resist comparison. The cooking either resonates or it doesn’t, and, if not for the hefty sum involved, there would be no hard feelings involved in trying it. Expectations, as always, are the enemy of pleasure, and trying to explain Michelin’s machinations or bowing before the authority of any interloping list remains a fool’s errand.

Any restaurant should be judged primarily on what it brings to its local ecosystem. And what Barker, Fabbrini, Pegg, Sandoval, and the Shieldses offer this city is a jolt of relevance that almost singlehandedly revives a dining scene that (at least from the uncharitable perspective of a globe-trotting gastronome) would otherwise be known as the place where molecular gastronomy went to die. They have woven a tapestry of ingredients, techniques, and philosophy that drags Chicago forward. Whether you like the chosen style or not, their cuisine stands as a monument to the kind of intricacy and perpetual evolution that defines excellence in craft.

So, as much as I try not to put my finger on the scale for a place I clearly love, I cannot help but admire Smyth’s continued dedication toward being dynamic and different and polarizing at the very height of its fame. It’s the same courtesy I extend to places like Elske (or Creepies), Cellar Door Provisions, and even Feld—places that may not always represent Chicago’s safest bet for satisfaction yet, in turn, are a few of the only places one really feels creativity brimming and maybe, just maybe, finds that unprecedented, transcendent bite. If anything, honest feedback is an essential part of the overall process.

In ranking the evening’s dishes:

I would place the “Preserved Kombu Tart” in the highest category: a superlative item that stands among the best things I will be served in any restaurant this year.

The “Toasted Corn & Black Truffle,” “Lamb Sweetbreads,” “Malted Milk Bread,” “Vermont Quail & White Truffle,” “Satsuma Mandarin & Ginger,” and “Pumpkin Pie” land in the following stratum: great recipes that achieved a truly memorable degree of pleasure. I would love to encounter any of these again.

Next come the “Amazake,” “Dungeness Crab & Kakai Pumpkin,” “Trout Belly Donut,” “Maine Lobster & Uni,” “Caviar & Pumpkin Seed,” “Tempura Quail Leg,” “Cadbury™ Quail Egg,” “Yogurt Mousse & Quail,” and “Bittersweet Chocolate & Maitake Mushroom”—good—even very good—preparations I would always be happy to sample again (but that just failed to elicit an extra degree of emotion).

After that, there’s the “Avocado & Turnip,” “Rainbow Trout & Pineapple,” “Trout Tartare & Roe,” and “Smoked Unagi & Matsutake”—merely good (or maybe just intriguing) items that fell short when it came to texture and/or flavor. That said, the underlying ideas shaping these dishes were sound, and they could easily be improved with a little more fine-tuning.

Finally, one finds the “Black Walnut Cured Quail Egg.” This is an ingredient that I know the kitchen can prepare in a delicious manner. However, the present composition, served at its particular point in the meal, was hard to stomach. It stands as the only bite of the night that went beyond “challenging” or “interesting” as to actually be unpleasant.

Overall, this makes for a hit-rate of 76% if one counts on the basis of individual dishes and a hit-rate of 75% if one judges the success of each of the listed courses. (The latter process helps to soften the influence of the opening and closing trios of bites, which—I agree—really shouldn’t weigh three times as heavily as the menu’s actual plated fare. That said, I do judge the larger “Vermont Quail” course as a success even though the egg portion was disappointing.)

(It may be worth noting that four of the stronger items—the “Toasted Corn & Black Truffle,” “Trout Belly Donut,” “Lamb Sweetbreads,” and “Vermont Quail & White Truffle”—as well as only two of the weaker items—the “Trout Tartare & Roe” and “Smoked Unagi & Matsutake”—were unique to the “Chef’s Menu.” This does not amount to that much extra food in terms of portion size; however, when one accounts for the price of truffle supplements alone at other fine dining restaurants, I think paying the $130 premium for a few unique, largely delicious recipes is worth it.)

On its face, 75% or 76% seems like a low number for a restaurant that stands at the pinnacle of price and reputation within Chicago’s dining scene. But it perfectly matches the lower end of the range I gave after my recent experience at Oriole (and it goes without saying that my meals at Alinea or Ever over the past year would be lucky to reach half that hit-rate). Moreover, the number of dishes landing in that “great,” “would love to have again” category (33%) is not far off from the number I reported for Oriole (40%) either.

Now, saying a three-Michelin-star concept just about keeps pace with one that only has two is not exactly a compliment. When accounting for the nearly $100 difference in price, it almost becomes an insult. And I hate putting these places head to head because, stylistically, they actually diverge (and, thus, complement one another). But the dichotomy persists because consumers are obsessed with identifying “the best” and diverting their limited resources toward the one tasting menu that guarantees the most pleasure.

For the majority of diners—those who haven’t consumed enough totemic luxury ingredients in their lives to find them boring (or, likewise, have not been jaded by the quality found in glitzier cities)—Oriole is the place. I don’t mean that backhandedly either. Nobody else is taking foie gras, truffle, or wagyu to the same heights of reliable pleasure in Chicago or doing so in such a sleek, sexy, warmly stewarded space. Nobody accepts the expectations of fine dining (for better or worse) so charitably and absolutely satisfies them, for such a wide swath of the population, so convincingly.

Oriole, from what I’ve seen, is meaningfully growing too (ironically enough with some help from ex-Smyth cooks). But they’re the modern master—the legible connection to the gastronomy (structurally coherent, richly pleasing) of the past. The restaurant is by no means a dinosaur, yet, among those who seek the avant-garde as a matter of sport, their willingness to meet the public where they are seems a lot like standing still.

Smyth, before the pandemic, was very much a modern master of the same type: fish ribs, funnel cake, brioche donuts, licorice egg yolk, and an array of The Farm’s produce paired with extravagant sauces. Even back then, you could say there was always something a little offbeat about how the Shieldses liked to flavor things. They had returned to Chicago with the building blocks of a singular style, and strange new avenues for further development just seemed to open up.

After the pandemic, buoyed by the addition of Luke Feltz, the restaurant’s rate of growth was supercharged. Smyth shifted from modern (if always irreverent and comforting in a way that lightly subverted the fine dining of yesteryear) to decidedly postmodern: obsessive in its embrace of certain ingredients and techniques and not at all shy about pushing them to a prickly extreme.

All those nut oils and savory fudges and seaweeds (as well as all the avocado, eel, and lamb) largely survive today—being offset by the seasonal bounty (including a rotating selection of seafood) but unbending in their influence. They form the core of a novel culinary language: one that, despite these chosen pillars, remains ever-evolving.

Indeed, the team could have drawn a line at any point over the past few years (especially in the wake of that third star) and said: “these are the perfected forms of these ideas, that we will play as our hits, and experimentation will otherwise be left to the fringes.” I don’t fault anyone for thinking not doing so is an error: that perpetually tinkering with the finer details while also never abandoning certain fundamental forms (which may be polarizing in their own right) is something like a lose-lose proposition.

Yet, the thing about Smyth’s cuisine is that there’s no real reference point (other than the kitchen’s own work) and no diminishing returns to speak of. There’s no distraction (from any trappings of luxury or special effects) from what is wholly a gustatory journey.

The team’s creative expression, from wine to food, remains at the bleeding edge. It continues to provoke as much as it pleases, but it also stands alone: as the only taste experience in Chicago (and one of a select few in the country) capable of pushing even the most privileged palates into uncharted territory.

Is this a rare virtue? Sure, but its allure is not restricted to serial fine diners. Rather, the cuisine is capable of charming anyone willing to look beyond expectations of pure pleasure and appreciate broader aesthetic principles: the idea (and again I think of Elske, Cellar Door Provisions, or Feld) that achieving reliable satisfaction is not as important as exceling within the boundaries of one’s particular belief system and style. When those certain dishes (and there were at least a few of them tonight) hit the bullseye, one knows they have connected with the very soul of the craftsperson. Matching one’s personal taste to that of a chef—whomever, wherever, acclaim be damned—and embarking on a shared journey of discovery remains gastronomy’s highest thrill.

Smyth, to this day, represents the triumph of a singular voice in a climate—gastronomic or even more broadly artistic—increasingly defined by what’s trite, safe, cynical, and downright demeaning.

I know this particular meal (a fleeting, squash-filled moment in time) doesn’t rank among the restaurant’s best, and I know that the restaurant’s best is still bound to alienate a demographic of patrons with an ironclad sense of what dining at this price and caliber should entail.

Nonetheless, I am heartened by the path Smyth continues to forge and confident that its time-tested process will yield even greater fruits: unforeseen and, for those with open hearts and minds, unforgettable.