Valhalla “2.0” certainly formed one of 2024’s success stories: representing the relocation and refinement of a concept that had already carved out a niche at Time Out Market.

I tried hard not to upgrade the restaurant’s rating (from two to three pineapples) solely on the basis of structural change. After all, “2.0” implies more features, more power, and the kind of improvement that is worth clearly demarcating. Valhalla had certainly solved some of the hang-ups I had about the original food hall environment—like grating noise, seats with sightlines of the lavatories, and a general lack of exclusivity (or luxury) corresponding to a venue that put forth an over-commercialized, caricaturized representation of Chicago’s food scene. Plus, it’s not like I blamed the chef for seizing the opportunity to debut and fine-tune this idea with minimal investment or risk.

Transplanting Valhalla to Division Street meant finally building a dedicated world in which to showcase the chef’s ideas. The result was a shadowy, minimalist space defined by a single, winding chef’s counter, a curtained lounge, an open kitchen, and a moody trance soundtrack. It played host to an experience driven not by needless finery but by coordination, precision, detail in the right places, and streamlining of the rest. The restaurant represented conscious deconstruction and reconstruction of fine dining that only left what was felt to be most essential behind. Namely, paying just shy of $200 per person, guests would be cared for firsthand by four of Chicago’s finest craftspeople: Stephen Gillanders, Tatum Sinclair, Jelena Prodan, and Sammy Faze.

The cuisine had taken some clear steps forward, but many dishes also remained from the earlier location. More change and more growth would come in time, I was told, as the team settled in. Plus, the caliber of the cocktails, wine, and hospitality on offer certainly impressed me.

Having made my three visits over the course of the concept’s first two months, I bet that “2.0” deserved the upgraded rating its nickname suggested. The food hadn’t hit the kind of highs I expected, but it was reliably good. All the other foundations that were now in place (most importantly at the level of human capital) seemed to ensure that the menu would yield new peaks of pleasure in due time.

I did come to question this decision—rating for potential rather than actualized, totally convincing quality—when looking back. But I was also heartened by the wider response to the new Valhalla’s work.

Just because the cuisine (after a half-dozen encounters in various forms) didn’t absolutely blow me away, didn’t—in turn—preclude the fact that it would impress the majority of diners with a degree of intimacy and breadth of stylistic influence that was wholly unique. Indeed, the response to the restaurant from Chicagoans and those visiting the city alike seemed to be overwhelmingly positive.

Now, more than a year after my last visit to Valhalla (and subsequent awarding of three pineapples), I get to see for myself. Was I right to have faith, or did I jump the gun?

Let us begin.

Valhalla’s tiled storefront—carefully curtained, framed only by a black vestibule—remains foreboding despite the concept’s soaring reputation. Situated on a stretch characterized by row after row of patio dining (spanning cafés, taverns, and eateries working across a wide range of genres), the restaurant, by comparison, almost seems like it doesn’t want to be found.

Walking in, certainly, is not encouraged, and there’s no doubt that diners who have shelled out the $50 deposit will find their way. Yet the change in tone from the openness of Time Out Market to this cloistered corner of Wicker Park is palpable. The food hall was a friendly introduction. 2020 W Division is a spaceship: ready to whisk patrons away from its quotidian neighbors and beyond even the rudiments of expectation.

When Qing Xiang Yuan opens next door, it remains to be seen how well Valhalla can continue to escape attention. The Chinatown institution (which, ironically, also opened a branch in Time Out Market last year) is looking to explore wine pairings with its dumplings at this new location. Given that Gillanders made his name (in part) with S.K.Y.’s “Maine Lobster Dumplings,” this development seems doubly ironic. But, in truth, I think it will actually form a nice synergy: a kind of traditional anchor to the kinds of pan-Asian techniques the chef has so successfully adapted to a fine dining context. And, for anyone who might leave hungry, what better way to chase a tasting menu built upon complementary flavors?

Stepping through Valhalla’s front door, the familiar scene unfolds: the shine of stainless steel, the targeted rays of track lighting, those elliptical shadows along the walls, the zigzag of the counter (clad in wood and a marbled quartz), a perimeter of drapes, and the dreamy beats of the ambient house soundtrack.

On Fridays and Saturdays, the restaurant now opens at 4 PM. That means, by the time I enter, the dining room is already more than half full. Four cooks are busying themselves at various stations behind the counter (where wisps of liquid nitrogen may, in a moment of theatricality, overflow from a bowl). They’re joined there by two captains, a sommelier, and a bartender. Three servers work the other side of the open kitchen, refilling water and facilitating the transfer of dishes down from their pedestal (in front of the guest) along with their eventual clearing.

Opposite the sparse interior design, the clockwork precision of the team—with their spiels and choreographed touches—shines brightly. It proves the point (and this was clearly Gillanders’s intention) that staff-guest ratio, training, and the actualized craft of service mean infinitely more than any superficial markers of “luxury.” (Indeed, while chartered super and megayachts may stretch to longer lengths and tout even finer appointments, it is at the level of staffing—due to maritime regulations limiting the number of passengers—that they really distinguish themselves experientially.)

I cannot fault the warmth and good nature of my captain. The sommelier, too, is both knowledgeable and charismatic. The cooks, when called upon, hit their marks too (I even observe one sharing a print list of recommendations—which include S.K.Y., Apolonia, and QXY among its restaurants—with a couple of professed tourists.)

However, neither Gillanders nor Sinclair nor Prodan are here (and Faze, I already know, has returned to Kumiko). This isn’t the end of the world—it’s only been about a month since S.K.Y.’s reopening in Lincoln Park, and the team still has other projects on the horizon. What percentage of patrons (I overhear that another couple at the counter is also visiting Chicago) would actually recognize these principals or really care about their presence so long as the food and service deliver? After all, I can think of at least a few Chicago restaurants charging more than double tonight’s menu price with no guarantee that one will see—let alone interact with—the head chef.

Nonetheless, this marks the dissolution (at least temporarily) of what I found to be one of Valhalla’s clear strengths: a sense of intimacy and engagement with an all-star team of the city’s top craftspeople. Even if the rest of the staff has been perfectly trained to substitute for these figures mechanically, they cannot bring the same sense of ownership, firsthand storytelling, or depth of expertise (regarding spirits or wine) to the table.

It’s a fine distinction (and, again, in no way disqualifying). The presence of these headlining artisans is more like the fairy dust—the cherry on top—that romanticizes what’s good and (even if irrationally) helps to excuse what may be lacking. Thus, I cannot objectively fault their absence, but it does undoubtedly put more pressure on the rest of the experience to deliver.

Taking my seat at the counter—somewhere toward the middle, a new vantage point for me—I am met by Valhalla’s slender menu. It is sealed with a silver circle of wax stamped “[925]” (the restaurant’s favorite motif, which itself references the hallmark used to denote the purity and authenticity of sterling silver). Guests are invited to wield an accompanying letter opener and slash through the fold, revealing the evening’s courses (arranged along uncertain hot/cold, soft/crunchy axes) alongside cocktail and pairing options.

Though I’m always one to opt for the bottle list, I recall that wine offered à la carte is sold by hand here (rather than being written out). Such a system can be exciting in its own way, but I figure that sampling a couple of the pairings will provide a better sense of how the program, at present, looks to please the vast majority of diners.

Tonight, the “Premier Wine Pairing” ($198) comprises the following bottles:

- NV Vazart-Coquart Champagne “Brut Réserve” Grand Cru [$55 at local retail]

- 2022 Thibaud Boudignon Anjou Blanc [$41.99 at local retail]

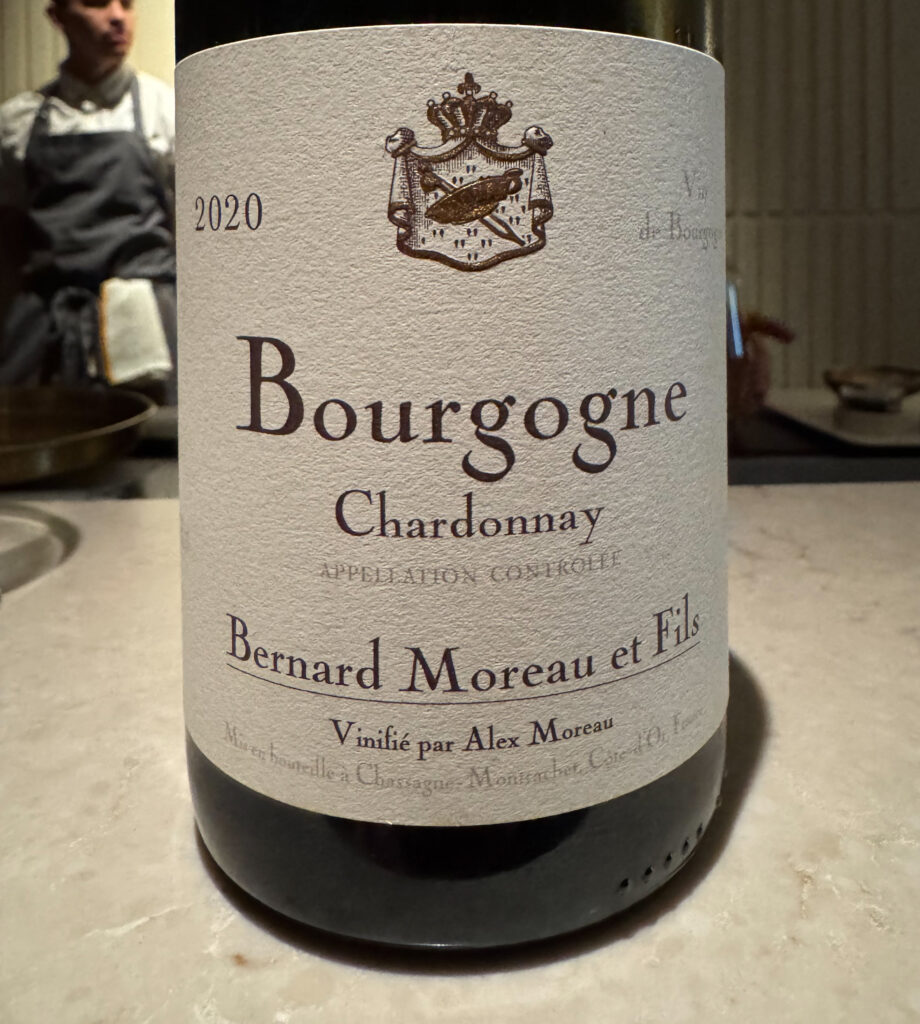

- 2020 Bernard Moreau Bourgogne Blanc [$59.96 at local retail]

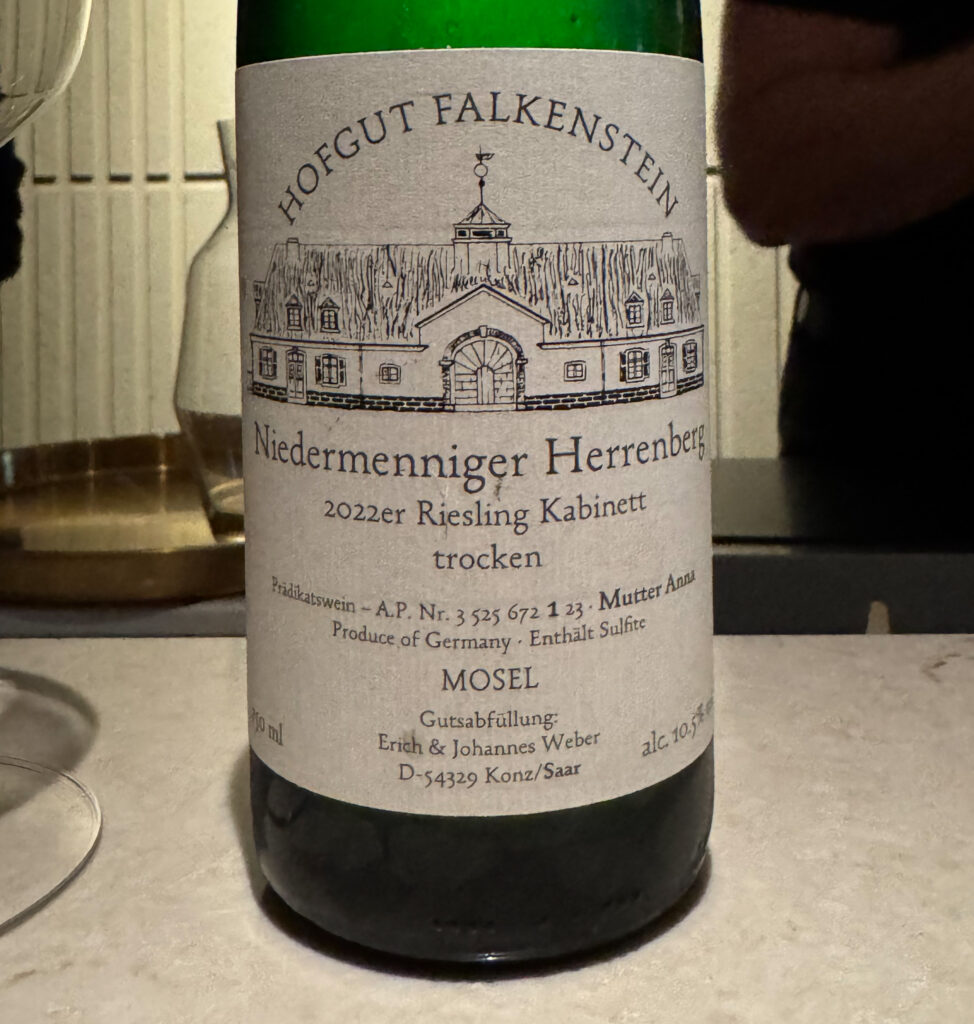

- 2022 Hofgut Falkenstein “Niedermenniger Herrenberg” Riesling Kabinett Trocken #1 [$41.99 at national retail]

- 2015 Paolo Bea “Arboreus” [$65 at national retail]

- 2020 Cave Caloz “La Mourzière” Pinot Noir [$44 at national retail]

- NV Vilmart & Cie Ratafia de Champagne [$55.99 at national retail]

The “Champagne Pairing” ($298), in turn, is made up of this selection:

- NV Vazart-Coquart Champagne “Brut Réserve” Grand Cru [$55 at local retail]

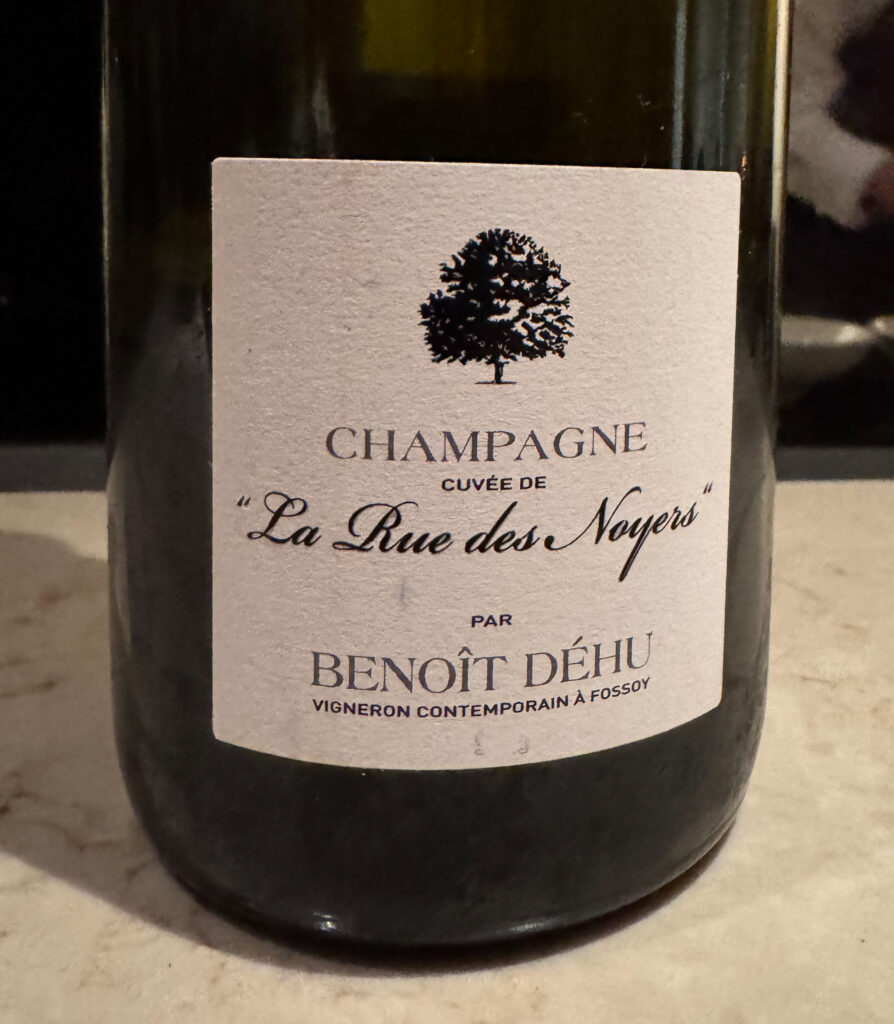

- NV Benoît Déhu Champagne “La Rue des Noyers” [$99.99 at local retail]

- 2021 Antoine Chevalier Coteaux Champenois “Les Crochots” [$39.99 at local retail]

- NV Krug Champagne “Grande Cuvée 171ème Édition” [$245 at local retail]

- NV Pertois-Lebrun Champagne “L’extravertie” Grand Cru [$71 at local retail]

- NV Drappier Champagne “Rosé de Saignée” [$54.99 at local retail]

- NV Vilmart & Cie Ratafia de Champagne [$55.99 at national retail]

On the surface (and this is also how I felt when seeing these producers arrive, one by one, during the meal), I do not quite find that sort of killer offering that makes me feel justified in spending $198 or $298 on a series pours rather than a single, superlative bottle. Indeed, while the “Champagne Pairing” has yielded a glass of Cédric Bouchard in the past, seeing Krug “Grande Cuvée” now occupy the headlining spot (in terms of retail price) is decidedly less enthusing. To be clear, there’s nothing wrong with the latter wine. It can be quite good. But it’s also produced in mass quantities and rather frequently seen (whether offered by the glass or on pairings) at other fine dining concepts.

However, putting aside what might personally excite me, it’s hard to fault Prodan’s work from a structural perspective. The bottles on the “Premier Wine Pairing” have an average retail price of $51.99, and being able to try seven different pours (of offerings that might be priced from $100 to $150 on a restaurant list) strikes me as providing good value. When one considers the quality of producers like Thibaud Boudignon, Bernard Moreau, Hofgut Falkenstein, and Paolo Bea (alongside the small degree of age on several of the selections), the pairing displays a real capacity to please experienced drinkers while also introducing neophytes to some of contemporary wine’s most engaging styles.

Looking at the “Champagne Pairing,” the same logic holds true. For $298, one gets to sample seven pours at an average retail price of $88.85 (and costing anywhere from $180 to $270 on a restaurant list). I’ve made my feelings about the Krug known, but it will be seen as a special bottle by a large portion of the audience. Plus, I think the Benoît Déhu and Pertois-Lebrun successfully speak to cultier tastes (while the Coteaux Champenois, rosé, and ratafia display the surprising breadth that appellation—“Champagne”—can actually offer). This pairing will always win points for being so singular. It’s just the kind of splurge that many guests, who might be interested in wine but fear a pricier flight might be lost on their palate, would actually go for. The education (in blends, styles) one receives along with a sense of luxury is a brilliant bonus, and even an oenophile would have to acknowledge that the producers here are thoughtfully chosen and (again save for the Krug) less commonly seen.

Ultimately, I would probably press forward with ordering a bottle à la carte next time I visit Valhalla. Yet that takes nothing away from a program whose pairings remain some of the city’s most exciting: ones that (despite the premium one must now pay to access the finest regions) remind me of the kinds of pairings that first broadened my horizons and inspired me to take wine more seriously.

When one also considers the accessibility of the “Valhalla Beverage Pairing” ($98), the adaptability offered by the “Spirit Free Pairing” ($78), and the sheer creativity of the “Anything But Wine” ($118) option, it’s hard to think of a restaurant that does more to meet its patrons tastes wherever they lie.

The tasting menu, still priced at a competitive $198, starts on a familiar note. The “Surf” sequence is a construction that Gillanders debuted with the opening of Valhalla’s new space, and it empowers the chef to dazzle his guests with a trio of introductory bites each centered on seafood.

Of these, the “Ceviche” is the most reminiscent of what I was served last year; however, it has been reconfigured to include bits of octopus, clam, prawn, avocado, and trout roe dressed in the enduring elderflower-habanero aguachile. For a bit of added flair, the latter sauce is poured tableside out from the nozzle of a large conch shell.

Here, the textures of the constituent elements—the rich flesh of the cephalopod, the plumper mouthfeel of the shellfish, the buttery ball of avocado, the pop of the roe—are beautifully rendered. The aguachile, by combining ample tang on entry with fruity and moderate heat on the finish, charges the ingredients: drawing out their latent sweetness and brine while also forming them into a cohesive expression of flavor. Overall, the dish feels pleasantly dainty but packs a real punch. For my palate, it ranks as the strongest part of the sequence.

The ”Nigiri” is entirely new, comprising a slice of kanpachi (a kind of yellowtail) flavored with ginger and served, skewered, on a base of shredded lettuce lined with rice. The resulting bite is clean and crunchy but lacks the fatty imprint of fish or concentrated umami I expect from this form.

Certainly, I’m judging this sushi against a pretty high standard (and can appreciate the fact that the kitchen is not trying to compete in a like for like fashion with what one finds at an actual omakase). If they take the kanpachi’s flavor to some further extreme, this could be an interesting idea to work with. Otherwise, it stands as the weakest of the sequence.

Lastly, the “Martini” (also new to me) lands somewhere in between. This bite centers on a Kusshi oyster that has been dressed in the style of a Gibson. That entails a dose of Galician gin, some pickling liquid (taken from a batch of onions), and a dash of olive oil.

On the palate, the bivalve feels clean and juicy. Its brine joins nicely with the brightness and tang of the accompanying dressing. However, a note of astringency overshadows any sweetness that might be lurking in the background. Ultimately, this is a fun idea but not one that necessarily highlights the oyster as best as it could.

The preparation of “White Curry Noodles” that arrives next marks a shift from cold, fleeting bites of seafood to a more composed, soothing construction that draws on yet another kind of shellfish that has yet to appear. A bowl of oblong shells hints at this ingredient’s identity before being covered—and used as a base—by the headlining serving. The resulting dish is crowned with two roasted Honey Mussels (a trademarked, selectively bred variety) in a broth made from coconut milk, red curry paste, fish sauce, and lime. The titular noodles, handmade and extruded, peek out from the bottom while the dots of two oils (one from lobster heads, the other from a blend of makrut lime and Thai basil) float over the top for a psychedelic finishing touch.

This recipe is said to be inspired by tom kha gai (a Thai coconut chicken soup known for its sour, spicy character), and, despite ditching the poultry, Gillanders’s rendition is quite successful. Texturally, it combines the tender, meaty bivalves with weighty (but yielding) noodles and a creamy, encompassing broth in a way that feels warm, rich, and satisfying. The resulting flavor, in turn, balances tang and sweetness with enough underlying umami to avoid feeling thin or sickly. However, the soup’s subtle, persistent heat and uplifting florality are what really make the dish sing, modulating its base notes in a way that reveals greater and greater depth with each spoonful. Overall, this ranks as one of the meal’s highlights.

The ”Turf” sequence that arrives next serves to mirror the “Surf” one that opened the meal: shifting the menu’s focus (at least temporarily) away from seafood and toward the pleasures of the animal kingdom.

“Katsu” references the breaded, deep-fried cutlets (whether chicken, pork, or beef) that are emblematic of Japanese comfort food. Here, Valhalla opts to use a piece of spare rib (whose bone acts as a natural kind of handle among the other two finger foods).

Texturally, the meat combines a brittle, crunching crust with tender (though not quite fall-apart) interior flesh. The chef’s take on the traditional, thickened tonkatsu sauce adds a nice sense of sweetness to the mix. The mound of shredded horseradish, for whatever reason, is rather muted. Its pungency might have provided an extra thrill, but I still enjoyed this item quite a bit.

The ”Tartare” comprises a generous slab of raw, marbled beef with a fairly thick grain, a thorough application of salt and pepper, and a crowning dab of mayonnaise. However, the key element is found beneath the meat: a rectangle of crispy potato.

This tater tot-like delivery system forms a hot/cold contrast with the tartare, tempering its fat while also amplifying the beef’s lusciousness by way of its brittle edges. While flavor one is left with feels adequately seasoned, the bite fails to transcend that simple “meat and potato” sensation. Ultimately, I like this dish a lot (certainly more than the “Nigiri” and “Martini” elements of the “Surf” trio), but it lacks an extra dimension—whether sheer intensity or stylistic flair—to really shine.

Last, there’s the “Speck”—a reference to the smoked ham that stars atop (and within) this play on the Spanish croqueta de jamón. Filled with béchamel and laced with cured egg yolk, the croquette offers a beautifully rigid exterior with a warm, oozing interior that cushions layers of salty, hammy goodness with well-judged richness. This bite is so satisfying and so well executed. It ranks as one of the best items of the night.

Having so thoroughly explored land and sea, the meal now looks to celebrate seasonal produce. A preparation titled “Local Tomato3” draws on the bounty of Nichols Farm (located in Marengo, IL), with the titular ingredient being hand-selected by the kitchen three times per week to ensure quality. The resulting trio of slices are placed atop a tomato water and lemongrass gelée (drizzled with olive oil) before being topped in three different ways.

The first of these draws on Kaluga caviar that has been cold-smoked over the staves of old Pappy Van Winkle barrels. As appealing as this double dose of luxury sounds, I only sense a faint note of salt. The second is inspired by a Filipino ceviche called kinilaw and comprises chunks of vinegar-cured tuna. Due to the robust texture of the fish and accompanying tang, I like this better. The third makes use of shio kombu—simmered, dried kelp that delivers more of the sweetness and umami I am looking for.

While, on paper, I admire how this course looks to showcase seasonal produce using several different lenses, the tomatoes are just fundamentally bland. They do not possess enough of their own character (whether sweetness or even acidity) to actually play off of the various toppings, and, even with the benefit of the tomato water gelée, this means the other elements more or less fall flat. Still, it’s easy to see how good this dish could be if the starring ingredients were to deliver what is expected of them.

The ”Lobster Tsukune” that follows also represents a low point for the evening. The course is meant to reference the kind of hand-formed meatballs that are skewered and cooked over charcoal in Japanese yakitori cuisine. Here, as the title suggests, Maine lobster meat is bound with shrimp paste to achieve the same effect. The resulting sausage-like substance is topped with seaweed then served alongside a smoked pimentón butter and some dollops of lemon gel.

Visually, the orange-hued preparation just begs guests to grab the twine-wrapped stick, drag the tsukuneround the plate, and deposit it in one’s mouth. However, upon reaching the palate, the lobster meatball feels almost mealy and (lacking the kind of plumpness one desires from this crustacean) proves undistinguished. The dish’s resulting flavor, too, is so dominated by citrus that I sense none of the sweetness (or smoke, or spice) I might otherwise prize. Yes, while I can appreciate the creativity involved in adapting lobster to this nostalgic form, I’d much rather be served a simple piece of tail or claw. Nothing, in terms of texture of flavor, is actually gained by this transformation.

On the back of a couple disappointments, the “Banana Leaf Baked Sablefish” represents a welcome return to form. Inspired by Goan fish curry and ikan bakar (an Indonesian grilled fish dish), this course draws on a two-part cooking method. First, the sablefish is coated in a combination of shrimp paste, chili, and lemon grass then backed (inside the titular banana leaf) at a low temperature. Next, the fillet is lightly charred and served over its wrapper with some crispy curry leaves and a Kashmiri chili “gravy.” A sprinkling of asín tibúok—the Filipino “dinosaur egg” sea salt the team proudly displays on the counter (and invites diners to take in their hands)—forms the finishing touch.

Texturally, the fish displays a gentle flake and a wonderfully melty consistency framed by the slightest exterior crunch. The accompanying flavor is built upon a remarkable degree of umami (the very kind I’ve been searching for in other preparations) but unwinds with layers of fruity, smoky, and subtly sweet notes that join with a mild, elegant heat on the finish. There’s a lot going on here, but the various ingredients are beautifully woven together via the weight and richness of the sablefish. Ultimately (and this stands in stark contrast to the tsukune), all the technique on display here is attuned solely toward the creation of pleasure. This recipe stands as another highlight tonight.

The “Arroz Caldo” dates back to the very earliest days of Valhalla—and to an embrace of Gillanders’s Filipino heritage and his grandmother’s cooking the chef has long postponed. The recipe has never (across something like a half-dozen encounters) really wowed me. Not that it was bad by any means. Rather, this play on a traditional breakfast porridge always landed more on the bright, light side instead of delivering the kind of deep, savory enjoyment I’d expect from a headlining preparation of rice. In all fairness, I’ve never thought it was really my place to pass too harsh of judgment on the proprietor’s personal nostalgia.

As far as I can tell, the dish has not meaningfully changed. It comprises rice cooked in an herbaceous broth, studded with chunks of queen crab, dressed in a butter emulsion, and topped with a combination of toasted black pepper, crispy garlic, and calamansi juice. On the palate, the grains and flesh of the crustacean strike with a luscious, melty consistency. The resulting balance of flavor retains its tangy foundation by displays a more pronounced crabbiness with some sharp, savory backing. While still not coming in among the menu’s highlights, this course made a welcome appearance tonight.

The ”Slowly Cooked Beef Breast” has quickly become one of Valhalla’s signatures. However, given that it joined the menu a few months after my first three visits to “2.0,” I have yet to taste it. Inspired by leng saeb (a Thai pork bone soup driven by spice and citrus), this cut of meat (what might typically be called brisket) is topped with a “relish” of garlic, green chili, scallions, and cilantro oil. Off to the side, a pile of grilled enoki mushrooms is meant to replicate noodles: helping to soak up a broth made from fish sauce, lime juice, and cilantro oil.

Texturally, the beef is a revelation: tender, yes, but with an accompanying juiciness and structure that really feels like you’re sinking your teeth into something. Indeed, the breast seems like Gillanders’s answer to the hackneyed “A5 wagyu”—a product that ticks the boxes of totemic luxury but whose oozing fat and general paucity of flavor often fail to fulfill what one actually desires from steak. Here, the meat offers an unmistakably carnal depth of flavor that serves as a canvas for harmonizing notes of tang, allium sweetness, and concentrated umami. The mushrooms, so delicately crisp, bring their own hints of fruit and earth to the fore while mainly serving to elongate and enhance the core flavors. Ultimately, the breadth and power of expression on display here is simply immense, yet all the ingredients are channeled toward lip-smacking, beefy satisfaction. This recipe has certainly earned it longstanding place on the menu and, tonight, ranks as the best of the savory dishes.

The turn toward dessert is elegantly managed with the arrival of a “French Onion Latte.” This brew—made from six different alliums, a dash of aged sherry, a foam of Wisconsin parmesan, and a sprinkle of sea ash—arrives piping hot (almost dangerously so). But the latte’s place on the menu (at the hottest part of the hot/cold axis) confirms this is the intention, and there’s something thoroughly cleansing about the temperature (once one is able to avoid burning their tongue).

The resulting flavor, so marked by caramelization, is richly sweet but balanced by enough salt and smoke to avoid feeling confected. In this manner, the latte encourages diners to begin thinking about the sugary treats to come without throwing them, headlong, into the deep end. Given the quality of the “Slowly Cooked Beef Breast,” it’s also quite nice to meditate on some echo of savory flavor for a little longer. Overall, this makes for a clever idea executed with real finesse.

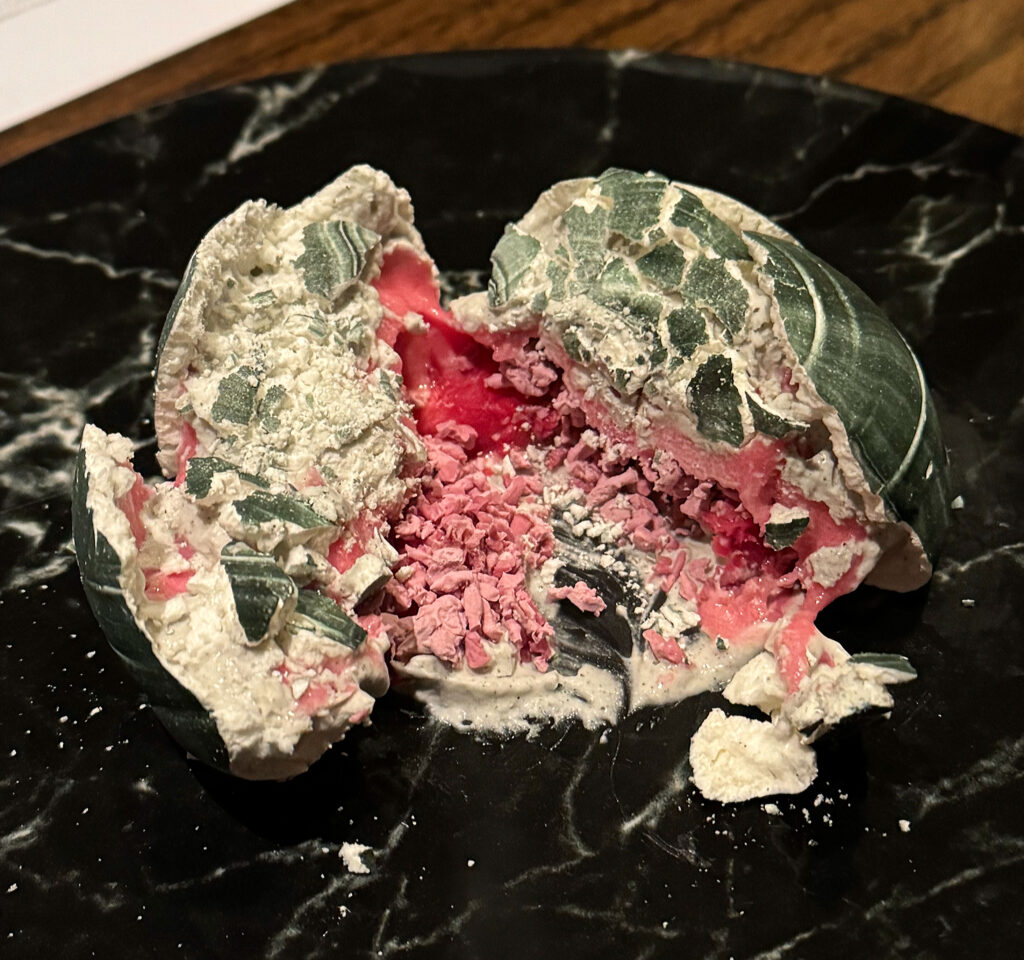

The ”Marbled Pavlova” dates back to the days of Valhalla “1.0,” but the dish did not originally feature when the restaurant made its move. For a time, “The Whole Lemon” seemed to take its spot (rather successfully). Yet, at some point, the team rightfully thought the recipe was worthy of an encore.

For this creation, pastry chef Tatum Sinclair fills a hollow meringue shell (hand painted to achieve the titular effect) with black sesame cream, chunks of lychee, and a play on Dippin’ Dots (flavored with hibiscus). In something of a new touch, guests are invited to pick out their own antique silver spoon from a felted box featuring the Valhalla[925] branding. Though this gesture is a fairly simple one, it helps to heighten the pleasure once trains their utensil on the pavlova. Upon doing so, the resulting crunch—and accompanying explosion of the inner cavity—is pleasing in a way that calls Alinea’s “Paint” to mind.

And the flavor here, for better or worse, is also quite similar: favoring tangy and tropical fruit notes that tantalize the palate without ever quite veering toward decadence. Still, given how engaging the presentation is (as well as the fact that this is only the first—rather than the headlining—dessert), I do not think this bias toward brightness is a problem. At a visual and textural level, the “Marbled Pavlova” remains quite charming. It’s a recipe the concept is right to lean on in pursuit of that long-awaited Michelin star.

Sinclair’s newest offering is titled “Torrijas,” a Spanish recipe for caramelized bread that is likened to French toast but also borders on a kind of bread pudding. For her take, the pastry chef soaks a piece of brioche in custard and cooks it to a crispy (yet also somewhat puffed) consistency reminiscent of a roasted marshmallow. A white chocolate crème anglaise, dotted with olive oil, forms a dipping sauce at the center of the plate. Some shavings of black truffle then form the finishing touch.

On the palate, the brioche marries a brittle, crunching exterior with a hot, oozing interior that retains the slightest weight and structure of the crumb. Soaked in the crème anglaise (which also forms a natural temperature contrast), the bread takes on an extra dimension of flavor: its concentration of deep, dark caramelized notes being buttressed by the creamy, milky sweetness of the white chocolate. The degree of richness here is hard to believe, and I have trouble understanding how the combination works so well without feeling overdone. Yet, with hints of char, of fruity olive oil, and the haunting earthiness of the truffle working in the background, this preparation delivers a degree of decadence and full-throated pleasure I so rarely encounter. Just how has Sinclair achieved this intensity and balance? It’s hard to think of a better dessert in Chicago.

The meal ends with a seasonal selection of “Lyneá Chocolates” (the pastry chef’s own proprietary blend of cacao). Guests are free to select as many of the half-dozen flavors on offer as they desire, with the resulting combinations being listed on an accompanying menu. As before, a paragraph classily offers thanks to the Flores, Juarez, and Alto Sol families whose “commitment to their craft” allows for the production of the chocolate blend.

Of the pieces served tonight, the “Sea Salt-Caramel” impressed me the most—being so straightforwardly pleasurable and astutely seasoned. The “Passion Fruit & White Chocolate,” “Earl Grey Tea,” and “Chocolate & Sea Salt” came in behind it, offering a little more intrigue (or, in the latter case, simplicity) while remaining centered on enjoyment. The “Sakura Cherry Blossom” and “Bajadera” (referencing a kind of nougat praline) landed more on the intellectual side but were in no way objectionable. Rather, it may be worth mentioning that the rolled truffle and madeleine-shaped bites performed better, for my taste, relative to the more traditional, square confections.

On this note of thorough and self-guided satisfaction, the menu draws to a close.

When the bill arrives, it is free of surcharges or service fees—an appropriate (dare I say essential) concession from a concept that has made such a point of stripping away fine dining’s more needless features. Instead, with the deduction of the deposit (and any other prepayments) denoted, guests are free to reward the team as they see fit.

I only count 90 minutes from the arrival of the “Surf” sequence to the selection of my “Lyneá Chocolates.” That makes for an average wait time of well under 10 minutes for each of the 12 courses served tonight, as well as an overall experience that (when one accounts for introductions and the arrangement of one’s beverage selection) spans less than two hours.

This is a blistering pace: one that speaks, again, to the clockwork precision of the entire team. I cannot complain about it either, for the kitchen’s efficiency was clearly driven by the speed with which I actually ate the food (as well as the intimacy of a space that allows for immediate signaling once a dish is finished). Honestly, for anyone with a show to catch (or, otherwise, who finds quick waves of deliciousness to be all the more appealing), it’s nice to know what Valhalla is capable of.

But, lacking the presence of Gillanders, Sinclair, or Prodan (as I have already discussed), the experience—even if it does not feel rushed per se—comes off as fleeting. The understudies entrusted to steer the concept in their absence do nothing wrong. It’s just that, lacking the same latent star power and expertise, they fade into the sleek, minimalist environment Valhalla has curated rather than effortlessly blazing against it.

The result is a menu with some real gastronomic highs rendered in a singular, globe-trotting style. When it comes to the nuts and bolts of service, the meal is clinical—almost textbook. And the restaurant should, unquestionably, be judged by what’s in the glass or on the plate (and how the staff hits its marks) rather than who happens to be behind the counter.

Nonetheless, having eaten here before and knowing what’s missing, I am faced with a certain emptiness. I feel tinges of anonymity and coldness even though they’re not intended nor maybe even perceptible to the rest of the audience.

Tonight, I feel like I have encountered a concept that excels at its price point—showcasing the kind of technical quality one need normally pay a hundred dollars more for—and that occupies a unique culinary niche. However, in exchange, it sacrifices the connection to craft (and to the hearts and souls enlivening it) that really makes this caliber of dining—particularly in a counter format—memorable.

By the time I step back onto Division Street, little impression of the time I’ve just spent remains. I can still savor the taste of the “Slowly Cooked Beef Breast” and the “Torrijas,” but there’s no spark of personality, no embodiment of taste with which to anchor them.

It’s just food—excellent, inspired food stewarded with care in truth—and is that not enough? Does stripping away fine dining’s frills not also justify the destruction of a flawed truism? That being the assumption that an executive chef or pastry chef or wine director’s presence, besides appealing to sentiment, actually improves the performance of the entire operation.

Indeed, Valhalla has doubtlessly proven that it can excel without any senior staff keeping an eye on the team’s work. The absence of the former (and their corresponding magic touch) may keep the restaurant, on any given night, from competing with Chicago’s very best. However, with the concept already coming in at a fraction of the price, its performance in these conditions remains a huge accomplishment.

Even if I am inclined to see what may be emotionally lacking at this moment in Valhalla’s lifespan, the restaurant’s foundations remain strong.

As much as this follow-up visit did leave me feeling some sense of disappointment, my objective measure of the meal—in reflection—was hard to argue with.

The beverage program, even if my pairings lacked the one killer bottle that really gets me excited, demonstrated its enduring quality, and the hospitality, exemplified by staff interaction as well as mechanical precision, could not be faulted. Given the conditions I outlined, the cuisine carried the heaviest burden and, despite a couple misses, continued to impress.

In ranking the evening’s dishes:

I would place the “Torrijas” in the highest category: a superlative item that stands among the best things I will be served in any restaurant this year.

The “White Curry Noodles,” “Speck,” “Banana Leaf Baked Sablefish,” and “Slow Cooked Beef Breast” land in the next stratum: great recipes that achieved a truly memorable degree of pleasure. I would love to encounter any of these again.

Next come the “Ceviche,” “Katsu,” “Tartare,” “Arroz Caldo,” “French Onion Latte,” “Marbled Pavlova,” and “Lyneá Chocolates”—good—even very good—preparations I would always be happy to sample again (but that just failed to elicit an extra degree of emotion).

Finally, there’s the “Nigiri,” “Martini,” “Local Tomato3,” and “Lobster Tsukune”—merely good (or maybe just average) items that fell short when it came to texture and/or flavor. That said, the underlying ideas shaping these dishes were sound, and they could easily be improved with a little more fine-tuning.

Overall, this makes for a hit-rate of 75%, which may seem low but should be understood relative to the overarching success of the “Surf” and “Turf” sequences (despite some constituents not impressing) and the number of items (25%) ranking in those first two categories of truly memorable pleasure. Yes, it might be right to label the “Local Tomato3” and “Lobster Tsukune” as the only real disappointments of the night (yielding a corresponding hit-rate of 88% that certainly accords with the lofty reputation I have assigned to this restaurant).

In the final analysis, I still do not really feel that Valhalla is a “three-pineapple” concept. It strikes me more as a strong “two” that is capable (when wine and food and the presence of Gillanders and his A-team all align) of climbing to that higher level.

However, approaching my experience more rationally, I remain comfortable with having awarded the restaurant that highest honor. Yes, if the audience accepts the deconstructive approach the team has embraced (extending to the absence of the chef-patron altogether), they can only admire the continued value, the consistent growth, and the undeniable quality Valhalla attains. I certainly respect it, and I don’t really fault the group’s talent for channeling all their energy toward the new S.K.Y. (and associated projects, like Le Mistral, that have yet to open). Neither should Michelin, who—since 2022—have contended their stars are “awarded for the food on the plate—nothing else.”

When Bibendum describes Gillanders as “ever affable and welcoming…[and] right at home in his new location,” one almost thinks the Guide will finally relent and award a star. However, I cannot help but note how Michelin describes the tasting menu as “ambitious in its attempt to trot the culinary globe” [emphasis mine] in contrast to the “highlight[s]” that dessert and the “equally thoughtful” beverage program entail. The inspectors do seem to have some lingering problem with the savory food—either, philosophically, that is tries to do too much or, maybe, that the worldly techniques being drawn upon aren’t actually represented at a high enough standard.

Certainly, I have to agree that the “Nigiri” and “Lobster Tsukune” wouldn’t be worthy of a Japanese concept touting a star. So maybe it is right to wonder if there could be a need for a chef-owner behind the counter after all: whether that means upholding standards, executing the most difficult preparations, or simply observing customers in a way that helps to suss out the menu’s weakest links.

At the end of the day, it’s not really about winning Michelin’s favor so much as it is realizing Valhalla’s full potential: one that was hinted at in the early days of “2.0” and that feels ever more within reach now.

In the meantime, the restaurant remains of Chicago’s surest tickets to creativity, pleasure, and value without any suffocating pomp. At this rate of growth—and maybe once all hands, yet again, are on deck—the concept’s place among the very best seems certain.