During the summer of 2020, out from the depths of the pandemic, sprang the most consequential restaurant opening of the year. And it happened in Chicago of all places.

The Windy City rarely commands the attention of the national food media complex. Those overgrown influencers might invoke Alinea’s name from time to time—perpetuating the restaurant’s undeserved status as the sine qua non of Chicago’s dining scene—but, otherwise, they pay little mind to the tastes of “flyover country.”

The best press the city might see from those dying publications is a championing of this or that flavor of the month “diversity” success story. This privileging of a superficial, implicitly politicized sort of “representation” by monolithic coastal elites impedes the cultivation of consumer knowledge and the celebration of establishments that resist easy categorization into prefabricated racial narratives.

The national food media feels ashamed of Chicago and clings desperately onto any new restaurant that might reveal its population’s tastes are not as backwards as once feared. They beat the drum for anyone who subverts expectations—all the better if they consciously engage in some pointed activism—while the nuances of Chicago and the Midwest’s own traditions are obscured. You do not refer only to the city’s European heritage, but to any business owner who—keeping their head down—focuses only on the mastery of their chosen techniques and the delivery of their customers’ satisfaction. (Mind you, not because such operators are unstirred by social injustice. They simply understand that one’s virtue must be expressed through the many, quiet moments of daily life rather than consciously performed in exchange for a pat on the head).

Clickbait-addicted, advertiser-betrothed “critics” and “journalists” deign to make martyrs of certain chefs while cheerleading for others who—failing in their own business pursuits—situate themselves as grand marshals of the social media lynch mob. Those who court (or contrive) controversy provide the publications with easy fodder—and are granted untold rewards for toeing the line. Such chefs choose the easy, politicized path towards national “prominence.” They leverage rumors and insinuations against their perceived enemies rather than walk the hard road of personal development and artistic fulfillment.

Bereft of talent, they work to construct an alternate reality that prizes chefs’ race and sexuality more than the quality of their cooking. In doing so, they allow issues of identity to taint any chance at forming a class-based coalition that might stand against bonafide abuses of power in the kitchen. They fall for the same distraction that kneecapped Occupy Wall Street nearly a decade ago, amounting to nothing more than the same old useful idiots (with but a few more scars and burns on their arms).

These activists in toques undermine food’s fundamental power to connect humanity. In an era where America desperately lacks unifying cultural touchstones, they seek to twist life’s purest pleasure into yet another weapon wielded against their neighbor. They enrich themselves and a media paradigm that thrives on anger, fear, and division at the cost of mutual understanding, tolerance, and harmony. They dilute the meritocratic appreciation of culinary technique by constructing sacred cows, by transforming chefs from masters of their craft into craven figureheads for their favored ideology. And Chicago’s dining scene grows poorer as consumers are led towards establishments that feed the media more than they do their communities.

But Curtis Duffy and Michael Muser—despite being two utterly unfashionable figures in the minds of a rampantly politicized food press—could not be ignored. The golden children of Chicago’s dining scene—who ran what still ranks as only the third three Michelin star restaurant ever awarded in the Windy City—had come home to roost. They had the nerve to open a luxurious tasting menu restaurant in a city where such concepts had slowly gone extinct. And, when the pandemic threw the entire industry onto its back foot, Duffy and Muser held firm. They charged forward, and the intrepid duo proved impossible to ignore.

Now, you don’t pay much mind to documentaries about fine dining. Yes, they make for good marketing fodder, but their high production value lends chosen restaurants a mythos that is better earned via a slow drip. For customers come to lust for a recreation of the “televised experience” rather than take a leap in the dark and face a meal that is utterly unfamiliar and singular.

All the contrived drama of the documentary form obscures any chance that guests can form their own connection to a given establishment. They’ve been sold on a chef’s story—their personal brand—and that now-famous figure need only show their face, must only meet expectations, to succeed in satisfying them. Media narratives are necessarily reductive—if not downright manipulative—and they impede a sense of mystery and subtlety that prove essential in delivering a truly transcendent meal.

Those who know Duffy have likely gotten to know the chef thanks to For Grace, which reached a wide audience thanks to its Netflix debut in 2016. The Chef’s Table series had only premiered there in 2015, meaning that the documentary tapped into a budding market for gastronomic content on the platform. Of course, the streaming service—and American popular culture writ large—is now positively saturated with glimpses into the “rarefied world” of fine dining. But, half a decade ago, molecular gastronomy retained its sense of mystery, and For Grace—as far as you can know—spun a story that sublimated the usual characterization of luxury restaurants as a prodigal pursuit. Spending money at Grace meant supporting the dream of a chef one intimately came to know through the television screen. It meant decadence with an added emotional undercurrent that diffused any feelings of guilt. In effect, it was a prototypical example—within the food world—of the kind of conscientious consumption drawn upon to lend wanton luxury a new lease on life.

Grace opened in 2012, earned two Michelin stars in 2013, and went on to clinch its third in 2014. But the journey came to a sudden end in 2017, and Duffy barely got to harvest the fruits of the documentary’s wide-ranging viewership. With three stars to its name and the perfect vehicle to prime would-be customers year after year, the restaurant might have fashioned itself into a longstanding temple of gastronomy. It might have formed the lynchpin for a new era of Chicago dining that retained some essence of Charlie Trotter’s, some of Alinea, but combined with greater coolness and restraint.

After five years, Grace fell apart due to tension between Duffy/Muser and partner Michael Olszewski. The latter owned the building, resisted the duo’s attempt to buy out his interest, and made the pair sign a non-compete clause that kept them out of action for at least eighteen months. The restaurant’s fate was sealed by a staff walk out in solidarity with the chef and general manager when relations with Olszewski finally collapsed. You still remember receiving the tragic news that your late-December 2017 reservation would be cancelled.

Olszewski tapped Mari Katsumura—who had worked at Grace for three years—to fill the former restaurant’s space in 2018. Yūgen, as the new venture was called, earned a Michelin star in 2019. The restaurant’s contemporary Japanese cuisine—juxtaposed with the remnants of Duffy/Muser’s expansive wine list—was, in your opinion, knocking on the door of being awarded a second. However, Katsumura’s partnership with Olszewski came to an “amicable” end in 2021 despite her skillful navigation of the pandemic. Yūgen, thus, ceased to exist. And, as he plans for yet another concept in the space, Olszewski’s status as a Mephistophelian stepping stone for talented chefs seems to be confirmed.

Looking back now, the “rise and fall” of Grace was but another perfect piece of marketing fodder. Though Chicago’s dining scene surely suffered in the interim, the kitchen had trained its share of staff in three-star excellence during that half decade. Duffy and Muser had cemented their names, and the misfortune ultimately served as a gripping twist in the personal story told by For Grace. Though seemingly representing the peak of the chef’s lifelong struggle, there appeared yet another summit to climb. The documentary about a defunct restaurant now served primarily to boost Duffy’s personal brand. It channeled all the attention towards what was next and cleared the ground for a triumphant return to the kitchen.

Duffy said as much in an interview shortly after Grace’s closure: “we’re going to build another restaurant that makes Grace look amateurish. You know, because it was our first restaurant, we know we can build a bigger and better and even greater restaurant.” The chef—who had also earned two Michelin stars at Avenues before the restaurant closed concurrently with his departure—also made his devotion to the Windy City clear. “Chicago deserves another great restaurant. We lost [this] one, now it’s time to give one back to them in a bigger and better way.” This time, according to Duffy, he would “control…[his] own destiny.”

In October of 2018—a bit less than a year after Grace’s closure—Duffy and Muser made their first move, securing a 6,000-square-foot ground floor space in Sterling Bay’s Fulton West development at 1330 West Fulton. The nine-story building—completed in 2017 and home to Dyson, among other tenants—lies at the far west end of the “Fulton Market Innovation District” formed by the City of Chicago in 2014. Though Smyth and The Loyalist are located only a block south, the corridor—at present—is positively sparse. With the hubbub of Ogden Avenue close by (including a gas station and McDonald’s drive-thru), this stretch of Fulton stands worlds apart from the street’s eastern promenade (home to, among many establishments, Rose Mary). But Duffy and Muser were clearly eyeing long-term potential. Diners, no doubt, would come to them, and Fulton Street—in due time—would extend its curb appeal right to the restaurant’s doorstep.

In June of 2019—right around the eighteen-month mark stipulated by their non-compete clause—Duffy and Muser’s new venture came into greater focus. Owing to the chef’s national status, the announcement came via The New York Times. Ever, whose name was then revealed, would seat 75 people and serve two distinct 12-15 course tasting menus in the “Flora” (vegetable-focused) and “Fauna” (seafood- and “light” protein-focused) styles formerly seen at Grace. Elsewhere, Duffy would label the cuisine “light, green, herbaceous, fun, whimsical, but still respectable with the ingredients.” The cost of the dinner would clock in between $300 and $500—billed then as “Chicago’s Most Expensive Restaurant”—with the added whimsical touch of opening bites hanging from the ceiling upon guests’ entrance into the space.

The design of Ever’s space was left to Lawton Stanley Architects, whose most notable credit up until that point—other than some Umami Burger and Giordano’s franchises—was Grace. (However, the duo was initially chosen because they had worked for the firm which designed L2O—“the prettiest restaurant in the world” according to Muser). Lawson and Stanley described Duffy’s aesthetic at Grace as taking “an approach towards material and construction” inspired by the chef’s “approach to cuisine.” In LSA’s words, that is one where “exotic culinary technique is secondary to the honest expression of each ingredient’s natural flavor.” Thus, “brown ash, honed stone, undyed wool & leather, oil-rubbed bronze, and patinaed steel” formed a natural match for the food given how they “present their individual character in a natural, minimally finished state.”

For their second collaboration with Duffy and Muser, LSA drew on the “winding path, hopes, obstacles, failures,” and “momentous successes” that lined the road from Grace to Ever. They sought to tap into “a sense of journey and discovery,” to “prepare a visitor’s mind for the nuance, grandeur, and intimacy of the experience.” The designers made sure to clarify that the space “is not a stage set,” but works as a path to “shape a transcendent experience.” Thus, the aesthetic draws on “wrapping” passageways whose destinations are “revealed slowly, intriguingly.” Materials are “ancient and accretive,” “hand-scribed,” “machined precisely when they need to perform,” and “supple and inviting when we touch and sit.” Rather than speaking specifically to Duffy’s culinary style, the aesthetic aims to instill a “respect for craft” and “care for each and every mundane task of operations.”

Muser himself defined the environment more succinctly: “if the Starship Enterprise had an awesome restaurant in it, this would be it.” And entering the dining room would be like “walking into one of those sound-deafening headphones.”

In early 2020, just before the gravity of the pandemic had begun to sink in, Ever’s honchos continued to build expectations. There was talk of custom chairs from German firm Rolf Benz (meant to surpass Grace’s signature “$1,000” Dutch-designed seating) and a “custom-built French stove” shipped “across the Atlantic.” Decisions were being made regarding “envelopes, menu paper,” and “whether to hang artwork on the restaurant’s currently bare walls.”

The restaurant’s name, too, was given some grounding by Muser: “We’re calling it Ever because all [Curtis] kept saying was, ‘It’s going to be the best ever.’ It just kept happening, and kept happening, and it became painfully obvious that this [restaurant] is the box where he’s just going to stick all of his evers. These are all Curtis’s evers, all his best evers, all the top evers, all those rock star moments that we’ve had and shared —- we packed them into the design of this thing.” And Muser was not simply throwing around the term “best” relative to a weakened Chicago market: “I want people in New York to talk about Chicago as a dining destination, I want people in San Francisco to be jealous of Chicago as a dining institution.”

Duffy conceded “the pressure is enormous” but that he and his partner had “unfinished business” and “the confidence that we can do it again.” Muser admitted that words could not quite capture the experience they were working to build: “You’re definitely going to have to buy the ticket to take the ride. You’ll see it when you sit down. You’ll see it when the stuff starts coming to the table. That we’ve gone above, and we pulled no punches on this thing.”

However, Duffy’s partner was later better able to articulate the exact standard to which their new restaurant would aspire: “This is a place you come to when you don’t want to question any of the ‘what ifs?’ Will we have a great dinner tonight? What will service be like tonight? Will we enjoy ourselves tonight? Will we be coveted and cared for? When we walk into that restaurant, will every single member of that team want to break their heads open to take [care] of me tonight? The answer in this room is ‘fucking yes all day, dude.’”

Ahead of a planned spring 2020 opening, some of Ever’s last pieces fell into place. “People enjoy working for Michael and me,” Duffy said while Muser voiced his desire for a “small army” of staff “equally dedicated to excellence.” By all accounts, they assembled a crack team: Amy Cordell, formerly of Charlie Trotter’s, Avenues, and Grace, would be the general manager; Justin Selk, formerly of Grace and Atelier Crenn, would be the chef de cuisine; and Richie Farina, former executive chef of Moto, would be Duffy’s sous chef.

The trio possesses a good blend of familiarity and notable outside experience. On the hospitality front, Cordell shares the same lineage as Duffy and Muser themselves. While the latter has now stepped into the role of director of operations, his successor in the general manager role can count the same firsthand experience when it comes to excellence. She has walked the walk in three of Chicago’s legendary dining rooms and intimately knows the standard of service Ever aspires to.

Selk’s time as executive sous chef at three Michelin star Atelier Crenn—and Farina’s seven years in the cockpit of one of Chicago’s legendary molecular gastronomy restaurants—are also consequential. But Duffy, it should be noted, is “an advocate” of “the traditional French brigade de cuisine hierarchy.” So, while his lieutenants possess plenty of technical and creative acuity, the head chef expects “a single voice for the kitchen” that will be echoed even in his absence. While George Kovach—formerly of Band of Bohemia and Acadia—was Ever’s opening pastry chef, he would leave after a few months. Lucas Trahan—who spent two years at Grace before working at Entente and Pacific Standard Time—has helmed the program since then.

Little more than a week after unveiling those key members of Ever’s team, Duffy and Muser were struck by the “two week” indoor dining shutdown that would last from March 16th to June 24th. The spring opening was delayed indefinitely—the restaurant’s luxurious space and its newly-hired staff left dormant. Such a twist of fate might have proven disastrous, but the team soldiered on. Duffy’s dream restaurant would unavoidably be moderated by the harsh reality of the pandemic, but it would come to fruition. Yet you must wonder—in the same way you ruminate over how Chicago’s dining scene might have developed had Grace survived—the degree to which the chef’s “best ever” expression had been deflated.

Ever would ultimately open their books on June 11th ahead of a July 28th debut—and reservations sold out in mere hours. Though Chicago had not, at that time, signaled the resumption of indoor dining, Duffy and Muser were clearly champing at the bit. Ultimately, their chosen date would prove conservative—service would start about a month after the city’s restaurants began seating inside. Some consumers had gotten their feet wet with dining’s “new normal” by the time of Ever’s opening. But individual comfort levels varied. Alinea’s rooftop residence offered some representation of “best practices” at a three-star level, but the mixed indoor/outdoor space reflected quite a different proposition than a dining room proper.

Ever was not returning to action or developing a new revenue stream on the back of an existing reputation (not yet at least). Its partners were deciding to birth a new expression of luxury—to shape dining experience of the finest quality—out from the throes of worldwide tragedy. On the surface, the opening was a tremendous statement. Duffy and Muser stood as beacons of hope for the future of a ravaged industry. They, once more, graced The New York Times in an article titled “How to Open a Top-Tier Restaurant in a Pandemic? Rethink Everything.” Therein, Mark Caro captured how “lofty visions have met hard reality” as Ever worked to finally realize its chef’s grand dreams.

But the key bit of context came from Nick Kokonas, who explained that Ever’s partners “probably don’t have much of a choice as to whether or not to open. They started raising money and building this out before the crisis hit. At some point if they don’t attempt to open, the financial obligations will be weighty enough that they cannot open.” The Times added, parenthetically, that “Muser agreed with that assessment.” Ever’s opening was a symbol of hope, but the writing was also on the wall: it was now or never, do or die.

Before the pandemic, the restaurant embraced the highest of expectations. Its reason for being was to surpass the standard set at Grace, to showcase the best of Duffy and Muser’s creativity without the slightest restraint. Now, Ever could only be judged in relative terms. It represented the salvaging of something deferred, a triumph of the spirit to offer superlative hospitality under the harshest circumstances. At $285 per person—excluding tax, tip, and beverages—the venture still had to satisfy some sense of value. (Though, notably, that figure falls conspicuously below the original $300 – $500 range touted). But luxury experiences play in the realm of illusion, and guests’ perceptions would undoubtedly be shaped by the events of the past year.

The restaurant designed to offer the “best ever” expression of Duffy’s cuisine now, necessarily, would be judged by its stewardship of public health. Ever’s world-building would inevitably be punctured by the concerns of the outside world. The artifice by which mere consumption becomes something magical would be that much harder to sustain. For luxury consumers, in accordance with a higher ticket price, typically take their safety for granted. That fundamental concern is so well assured that it recedes from the mind altogether. One expects to be safe, comfortable, and pleasantly catered to as a bare minimum. Only upon these foundations can the delicacy of a refined meal—however it measures up to one’s expectations—begin to be enjoyed.

But paranoia—if not downright fear—had grown into an essential mental state. Impressing consumers through the establishment’s devotion to their safety then lulling them to some baseline of comfort now proved Ever’s essential tasks. The finer details that distinguish the best restaurants from the rest would become more like accessories. Because enjoying a meal in a dining room was a luxury in itself. Experiencing a tasting menu had transformed into a tremendous novelty. And just even going through the motions of top level service—irrespective of the cuisine’s objective excellence—would assuredly satisfy diners who had been stripped of their usual reference points.

This is all to say: the extravagance to which Ever aspired was hobbled from the very beginning, and the restaurant has only—thus far—existed as a shadow of what its branding promised. The most conspicuous, colorful element of its design—the panoply of hanging ingredients guests would get to nibble on before entering the dining room—was excised. That nod to the “Willy Wonka tradition” would have set a playful tone for the evening (“this place is already fucking bananas —- let’s go,” as Muser describes it). It would have formed the thematic core of the entire experience, showcasing the constituent parts of the menu in a stripped-down form juxtaposed against Duffy’s refined compositions.

Such a contrast would strike right at the core of molecular gastronomy’s key tension: how does one worship ingredients’ essence at the same time one totally reconceives their form? How important is the legibility or purity of a chosen gustatory substance when it comes to offering pleasure? Can the novel shine without some sense of the nostalgic? Ever’s liminal space of hanging delights would have bridged that aesthetic gap in a cohesive, emotional way. It would have stood as a signature element—a totem—of the highest order. And it would have been the rare sort in fine dining that draws on spatial proxemics for dramatic foreshadowing.

But, without any opportunity for interaction, the device offers little more than a passing photo-op—“a glimpse of what you’ll be consuming.” The dangling delectables—now inedible—becoming nothing more than a gastronomic baby’s mobile. Duffy defined the space as “about feeling young” and hopes its role as an imaginative introduction to the meal can be resurrected. Nonetheless, the pandemic stripped Ever of—perhaps—its most inspired idea as the restaurant, instead, put its creative energy towards a $10 supplemental “personal safety kit” (featuring “a mask, hand sanitizer, and latex-free gloves”).

That, too, would be excised once Muser figured diners would struggle to “get lost in a world of food and wine” if they were greeted with something to the effect of “Here’s your first-aid survival kit. Don’t die. Enjoy your dinner!” The ultimate solution to the P.P.E. problem was a “$6,000 problem solver” in the form of a custom table built by Lawton Stanley Architects to match their interior. No doubt, there is something luxurious about commissioning what is, in effect, a four-figure sculpture for the sole purpose of holding masks and hand sanitizer. But the table, as much as anything, stands as a symbol of the resources that were necessarily diverted from the pure pursuit of gastronomic achievement.

Ever would, indeed, open on July 28th of 2020 and fulfill its status as a national beacon for the hospitality industry (and beyond). You were there on that first night, and it seems unfair to label it anything but a success. For the stakes were not that Duffy must deliver the very best cuisine Chicago had ever seen, but that he deliver a refined, pleasing meal in which guests felt unquestionably safe and, more so, comfortable. Muser, too, when working the floor as an omnipotent director of operation, was positively charming and charismatic. The would-be posterchildren for wanton luxury had transformed into wizards of gastronomy’s new, post-pandemic “normal.” They took it upon themselves to define and enact best practices for rarefied dining rooms and pulled it off without a hitch.

The restaurant’s books were filled throughout that exuberant reopening period in 2020. You, yourself, ate at Ever four times in total that year. But the restaurant had only barely reached the three-month mark—the bare minimum upon which a critic could, in good faith, offer a review—before Illinois halted indoor dining once more on October 30th. Service would not resume until January 23rd.

With the rug pulled out from under them once more, Duffy and Muser responded with a to-go menu in November and—even more boldly—a ghost kitchen slinging burgers in early December. “Duffy’s take on a well-executed fast-food sandwich” was titled Rêve Burger, and the concept survives to this day in a space kitty-corner from Ever itself. The double-quarter-pounders with American cheese, secret sauce, and BBQ-seasoned (frozen) fries are tasty but not life-changing. However, they served to “keep some staff busy and employed through the pandemic” while ensuring the chef’s mothership—in one form or another—stayed on diners’ minds despite the second shutdown. Rêve Burger’s sudden unveiling on social media certainly caused a sensation—and posting one’s “three-Michelin-star” burger (despite the superior, “two-star” example just down the street) became something of a “foodie” status symbol for a time.

By February of 2021, Duffy and his team were back to crafting tasting menus for diners. However, the stop-and-start nature to proceedings could not have been good for staffing—let alone creative flow. Three months of operation certainly taught the restaurant something, but momentum—especially after such a deflating regression—would need to be built back from zero. The hope surrounding Ever’s initial opening was now colored by an undercurrent of frustration, a sinking feeling that even the best laid plans would still leave establishments utterly vulnerable to pervasive, perpetual public health concerns. However, once more, Duffy and Muser could only charge forward.

You ate at Ever four times in 2021—comprising the months of February, April, June, and August—and feel that the restaurant can now be appropriately judged. Duffy and his team have regained some momentum and possess a year’s worth (give or take those three months slinging burgers) of culinary development to analyze. However, their work still must be qualified against the conditions the team has endured. Thus, while your meals from 2020 provide a valuable reference point when considering Ever’s development, you will focus primarily on your most recent experiences in an attempt to capture the spirit of the meals that guests, moving forward, will be served.

Though Ever’s sticker price demands it live up to a certain value, the restaurant has clearly not hit its absolute stride. (You wonder whether the establishment will one day embrace pricing in line with the higher range it originally touted). Duffy has had to sacrifice the dual “Flora” and “Fauna” menus he hoped to transfer over from Grace while the hanging amuse-bouches remain mere food for the eyes. Most diners, inevitably, are first-timers who benefit fully from the meal’s novel elements. And many, likely, remain highly sensitive to issues of safety and comfort that obscure a pure appreciation of gustatory merit. This is all to say: Duffy and Muser continue to defer their dreams of a “best ever” concept due to the business reality they continue to be faced with. The hype surrounding the restaurant certainly grew to epic proportions before the pandemic—and it stands as a marketing bubble that should be burst—but thoughtful criticism must retain a certain sense of understanding. For it would be all too easy for Chicago to lose Grace’s dynamic duo all over again.

As is standard, you will condense the sum of your experiences into one cohesive narrative (with a particular emphasis, as previously stated, on your most recent meals). However, for the sake of parsing Duffy’s culinary style as accurately as possible, you will be exhaustive in describing the full range of dishes served across all of your visits. Because, while elements like staffing and world-building necessarily suffered due to the pandemic, the chef was still “graced” with top talent, top ingredients, and top equipment. Creativity often thrives under pressure, and fine dining—perhaps now more than ever—must justify its indulgence. Why shoulder the risk for anything but transcendence? (Or, perhaps, consumers are so starved for the appearance of “luxury” that they forget how to perceive its substance—or lack thereof).

The stage now set, let us begin.

With so much of Fulton Market’s prime sprawl closed to vehicular traffic (in order to accommodate ample patio seating), the ride towards Ever takes on a different character. Whether you travel westward down Lake Street or choose the positively tiny Carroll Avenue to make your detour, the scenery confronts you with some fleeting vision of an old neighborhood now going extinct. No, it’s not the usual sob story of “gentrification,” but of old industry yielding to new.

Jutting this or that direction off from the West Loop’s recreational hub—from the towering offices, hotels, and residential buildings that have finally judged the area habitable—you are reminded of what once was. Truck rental lots, metal recyclers, waste transfer stations, and industrial food processing plants line dilapidated streets and signal a heavier, nastier sort of commerce that had made its home on what once was, unquestionably, the city’s outskirts. Of course, there are the ubiquitous meat packers, sausage makers, and seafood importers whose bunkerlike facades leave more than a little doubt that they’ve been open in the past decade. At least, as mere window dressing, their signage strikes you as altogether more appetizing than the former category. And, as real estate, Fulton Market’s former food purveyors are just goldmine waiting to be tapped for the next glitzy, gargantuan development.

Ever sits across from the former location of the Wichita Packing Co., one of the country’s foremost suppliers of pork ribs. The site is now an empty lot, and—with a parking lot filling the rest of the block opposite the restaurant—you get the impression that Duffy occupies an outpost on the far end of town. But Grace, once upon a time, stood at the cusp of a Randolph Restaurant Row that, at the time, could only boast a Bar Louie and a Check Casher where it intersects with Halsted. Smyth, too, sat across from a parking lot—now a residential tower—in its time. Such restaurants form the reference point for the future of the block. The world they build on the inside—and that the first flush of guests travel to—reflects the outer world to come. Soon enough, the outpost becomes more like the nexus of a new neighborhood: one where the prospect of spending a thousand dollars on dinner no longer seems out of place.

But a space such as Ever’s must feel eternally—not relatively—luxurious. It can never be outdone by the upstarts that eventually arrive on their block if it hopes to occupy that highest stratum of experience. It must shine as brightly against the future as it does against the rubble. Its design must achieve something truly timeless to justify that $5 million price tag, to strike guests from the first moment as being “worth a special journey.”

You arrive at 1340 W. Fulton a few minutes before your reservation time. That offers a moment to linger at Ever’s imposing doors and appreciate the logo etched into the ground below. (During one meal—in the depths of Chicago’s winter—you were greeted by a shimmering ice block into which the logo had been framed). On other occasions, you’ve run a few minutes behind and found a suited figure waiting to usher you into the restaurant. But the façade, whatever the occasion, gives very little away.

While Smyth’s ample, street-facing windows welcome guests with some vision of the energy contained in its dining room, Ever—like Grace, like Alinea and Oriole—invites diners to enter an unknown world. Thus, the charm of an exceptional experience “hiding in plain sight” (one, perhaps, rooted more strongly in the urban bustle) is substituted for a wonder that stands distinctly apart from any outside influence.

You enter through Ever’s portal and cross a short vestibule whose door deposits guests face to face with the monolithic host stand. Two women, suited in black, roll your name off their lips and bid you welcome. One stays behind, manning the post, while another leads you off to the left to begin your journey. It is but a short distance to the table, but Lawton Stanley’s curved walls have their intended effect. The path winds without ever giving away its destination, but the glowing stone surfaces and dark flooring soon give way to the restaurant’s “party piece.”

That being, of course, the fabled Willy Wonka room: a jewel box of hanging ingredients that would have shattered the restaurant’s somber mood with the delightful invitation to sample the many representations of the season’s bounty. As previously discussed, the pandemic scuttled what might have been a keynote experiential element. The space—though particularly striking due to its stark tones of white—now stands as a cursory bit of scenery. For, while the hostess invariably introduces the room as a testament to Duffy’s embrace of nature, she is usually all too ready to whisk you into the dining room proper. (Perhaps, in that manner, the staff works to avoid guests errantly accessing the hanging ephemera as originally intended). But, knowing the history behind the design, you make a point to linger for at least a moment. And the hostess, to her credit, notices and allows you to comfortably pause for pictures and further inspection.

At its best, the room has regaled you with the feeling of abundance. In the fall of 2020, that meant a veritable cornucopia of squash as the centerpiece. Such an assemblage made for a familiar seasonal tableau—but done with aplomb. The principle pumpkins were picture-perfect while others proudly touted multicolored boils and gnarled stems. The juxtaposition placed conventional beauty and ripeness opposite expressions of nature’s biodiversity that subvert the standard symbology of desire.

Another setup, from the winter of 2021, was made all from twisted branches and pinecones enveloped on and around each other. But it, too, possessed an engrossingly rustic quality that bordered on being ugly. Perhaps it simply smacked of death. Whatever the reading, the winter piece also succeeded as a sculpture. Both it and the pumpkins benefitted from a shadow of foliage that was backlit onto the glass along the back wall. That additional element, however slight, hammers home the notion of mise-en-scène. It’s a thematic totem that—like L2O’s own golden coral sculpture back in the day—grounds the aesthetic experience to come. (And, when the rest of the meal’s staging has more to do with sensory denial, such priming pays dividends).

But Ever’s “Wonka room” offers more than just a centerpiece: items like radish, apple, pepper, carrot, fish bones, old bread, flowers, mushrooms, and citrus hang above guests’ heads in a petrified state. And, truth be told, many of the ingredients chosen for the installation resist your attempts to identify them. That’s how successfully they’ve been transformed into something more aesthetic than edible—a notion that haunts molecular gastronomy in its own way. For those who think such techniques amount to nothing more than a torturing of nature’s bounty will find in the hanging objects an eerie quality. Being inaccessible to the guest, the ingredients might be read as proverbial “heads on pikes.” In their lifelessness, they form an altar to Duffy’s virtuosity and perpetuate the promise of the mind-bending flavors and textures to come.

While nothing could be quite so memorable as the interactive amuse-bouche the space was designed to provide, you appreciate the restaurant’s devotion towards curating an artistic emblem for the meal. The most recent rendition—staged during the summer—was comparably sparse. There was no centerpiece, and the hanging items were dominated solely by plants and flowers. Perhaps that scene—characterized more by vibrant forms and natural light—was felt to best express the season. But you felt it to be a bit more detached from the ingredients that would appear on the plate, and such a disconnect would transform the space from a connective totem into something—all the more—only befitting a brief, forgettable, glance on the way to the table.

You turn another winding corner and find yourself at the threshold of the dining room. It is subdued, foreboding, and Muser’s reference to the Starship Enterprise starts to make sense. This is not the realm of traditional “luxury” in the European tradition, but something undefined and alien. Yes, Ever’s space is pleasing to the eye. It feels, for lack of much to latch onto, “special.” (“Cold”—some might say—or “cryptic.”) Yet the restaurant deserves some credit for spurning the usual signifiers of a top class meal in a rarefied setting. There are no gleaming metals, no plush velvet, no polished accents of fine leather or wood.

The restaurant is not desperate to justify its ticket price at the aesthetic level. Rather than “show,” it invites you to “feel.” Such was the effect of Alinea’s old illusory hallway and—to a lesser extent—the maladapted tone they have carried through 2.0 and 3.0. It’s a dramatic construction that puts immense pressure on the rest of the experience, as it works to delay satisfaction in its entirety until the very moment the first morsel of Duffy’s food reaches your lips. Rather than revel in the charm of being “somewhere,” guests sit in a room that relates to “nowhere.” The dining room stands wholly apart from place and time; it is the blank canvas onto which the genius looks to paint hues that shimmer all the more brightly in the ether.

You are guided to your table—a sleek, slate number that carries an impressive weight and matches the curved design of the passageways and partitions—and settle into one of those $1,000 Dutch-designed chairs. Yes, they’re comfortable. But not shockingly so. The chairs’ construction is admirable due to its combination of solidity and weightlessness (the latter, surely, is a boon for a front of house team that never misses an opportunity to pull out a guest’s seat upon their return to the table). The design also ensures you maintain the right posture relative to the table—a feature that, like so many other aesthetic aspects, ensures that attention is drawn effortlessly and fully to the food.

Three other elements of the dining room’s design are worth noting. First, the space features sound-dampening ceilings from Turf Design that Muser likens “to slipping on a pair of noise-cancelling headphones.” With that element in place—alongside ample spacing and management of sight lines between parties to begin with—the guest experience is nicely compartmentalized. You cannot ever remember hearing or seeing other diners to any notable degree. Each group is shrouded in its own experiential bubble without the slightest chance of interference—even if an adjacent table should burst into laughter. This, like so many other elements, heightens one’s potential enjoyment by filtering out distractions and emphasizing the people and drama at one’s own table. (The “museum quality lighting” from multi-pronged fixtures surely helps too).

Second, the room—as best as it can be defined by anything—gravitates around a tiny window with “opaque stripes” that obscure a direct view of the kitchen. Duffy, further, maintains a “gridded screen” that can slide to totally block out the window when desired. But guests, at best, are barely able to make out the hustle of bodies working to craft their meal. The window, which matches the same material used for the “screen” behind the centerpiece in the “Wonka room,” glows faintly with white light. All the while, it remains inaccessible: it teases but a modicum of the activity that lays behind it. The kitchen’s bustle never forms a distraction—even when you are seated directly in front of it. Yet a sense of energy and mystery remains when you train your focus upon it from any corner of the room. It’s the “promised land,” the “chamber of secrets,” the “bright light at the end of the tunnel.” Thus, subdued, luxurious experience at the table retains some slight hint of the effort being outlaid to conjure the chef’s creations. However, a feeling of effortlessness largely reigns.

Third, the dining room’s fanned partitions—which curve around tables and match flat portions of the wall—incorporate pedestals that are used as serving stations for wine. Those guests indulging in the pairings will find that the various selections are staged throughout the room, with each bottle displayed next to one of several eye-catching Riedel decanters. (Though these marvels of crystal—particularly those with obnoxiously elongated necks—are a scourge to use in the home, they are a pleasure to see wielded skillfully by the staff). Diners who elect to order a bottle off of Ever’s list will also see them placed on the pedestals so that they may be admired throughout the meal. Once more, the thoughtful management of sight lines balances the beholding of distant pleasures while empowering the action that occurs before you.

Speaking of wine, taking your seat at the table signifies that it is time to choose the evening’s beverages. (Though, if you are being honest, you always ask to be sent the wine list ahead of time. For programs of the caliber to which Ever aspires often tout a dizzying array of options, and it can be hard to parse where the real value lies when the rest of your party is waiting. Preselecting bottles has the added benefit of facilitating better wine service—like decanting ahead of time—or merely signaling to all and sundry that you are a discriminating drinker).

Ever’s opening wine list comprised the categories of Champagne/Other Sparkling, Alsace, Austria, Germany, the Loire, the Rhône, Beaujolais, Spain, and the United States. One year later, the list’s featured regions are exactly the same—with the addition of a Dessert Wine section. But that does not mean the selections haven’t changed.

The inaugural Champagne list most notably featured N.V. wines from Agrapart, Bérêche, Gaston-Chiquet, Larmandier-Bernier, Egly-Ouriet, and Pierre Peters alongside vintage releases from Agrapart, Billecart-Salmon, Pierre Paillard, Pierre Gimonnet, and Vouette. The most expensive bottle at the time was a N.V. Paul Bara Grand Cru “Réserve” priced at $1,320. That wine, which is sold in Chicago for as little as $47, clearly had an extra decimal place mistakenly added to it. The error persisted until you pointed it out to the sommelier upon the restaurant’s reopening in 2021—and you sure hope no customer ordered what they mistakenly thought was one of the list’s superlative offerings.

In its present state, Ever’s Champagne selection has seen its Bérêche, Egly-Ouriet, Pierre Peters, and Vouette bottles picked off. Some Agrapart remains—the N.V. “7 Crus” at $151 standing as a good option—alongside the Larmandier-Bernier “Longitude” at $155. But the most notable additions—rather than restoring the stock of those cult favorites—have been a 2010 Dom Pérignon ($615), N.V. Krug Rosé ($950), and 2012 “Cristal” Rosé ($1,800). (For reference, the 2010 Dom Pérignon is priced by Gibsons Italia at $350 and the 2009 “Cristal” Rosé at $974. Maple & Ash prices their 2010 Dom Pérignon at $575 and their Krug Rosé at $780). The Sparkling Wine section is characterized by some Schramsberg and a unique 2007 Raventos “Mas del Serral” from Spain (priced at $385 and available at Leña Brava for $296).

Ever’s Alsatian whites have provided great value and continue to do so. Rieslings from the “usual suspects” such as Beyer, Boxler, Hugel, Ostertag, Trimbach, and Weinbach tout 5-6 years of age with many landing under $100. Meanwhile, Trimbach’s “Cuvée Frédéric Emile” and Zind Humbrecht’s “Brand” (both priced at $230) reflect the region’s top offerings. The Pinot Gris selection is quite a bit shorter; however, it offers a similar sense of value around and under $100.

The selection of white wines from the Loire Valley has been quite extensive from the start. There are 16 different Sancerres under $100, but a 2019 Vacheron village ($105) and a 2018 Vacheron “Le Paradis” ($210) stand as the only top-tier examples from the appellation. Saumur is a real strong point thanks to wines from Guiberteau, Stater-West, and Thierry Germain under $100. These expressions of Chenin Blanc might fit the bill for those ruing the restaurant’s lack of white Burgundy. The Savennières section features a bottle of Nicolas Joly’s “Clos de la Coulée de Serrant” ($270) and a couple from Domaine des Baumard with back vintages (including Joly’s more affordable “Les Vieux Clos”) of both producers having been picked off since opening. Lastly, while the Vouvray section once leaned heavily on Domaine Champalou (with various wines from 2003-2019 spanning $60-$183) it now counts a set of 2019 Huet lieu-dits for $100-$120. While the section has long been headlined by a $770 Huet “Clos du Bourg,” the Vouvray—like the Saumur section—offers some of the list’s best QPR bottles.

Ever’s German Riesling selection is an embarrassment of riches. Comprising 84 different wines (priced from $44-$262) at opening, the section now stands at 60 bottles (priced from $40-$262). The vast majority of wines are priced below $80 with some in that range even boasting up to 12 years of age on them. While an affordable trio of Kellers—“Von der Fels” ($90), “RR” ($126), and “Limestone” ($70)—quickly sold out, the selection still touts a range of cult names largely unseen (and certainly unmatched) throughout Chicago. This includes Julian Haart, Peter Lauer, Stein, A.J. Adam, Carl Loewen, J.B. Becker, Gunderloch, and Koehler-Ruprecht alongside household names like Robert Weil, Willi Schaefer, J.J. Prüm, Fritz Haag, and Dönnhoff. Though you think the more expensive GG offerings are not quite so impressive, the selection stands as a Riesling wonderland of unparalleled accessibility and easy pleasure. It’s a part of the list that the restaurant should really be proud of.

The Austrian section—relative to the German wines—has aimed more at the high end. Though a beautiful aged selection (going back to 2009) of Riesling and Grüner Veltliner from F.X. Pichler has sold out, Ever still offers serious wines from Veyder-Malberg, Nikolaihof, Prager, Alzinger, Hirsch, Loimer, Schloss Gobelsburg, Bründlmayer, and Nigl alongside a smattering of lesser-known producers. Though the pricing generally lands in the $100-$150 range (with quite a few above $150), the Austrian section is just as thoughtful as the German. Those looking for “GG” level dry whites should embrace the former while the latter excels in delivering an endless array of easy-drinking options (though not altogether without character).

The Spanish whites—save for a Pepe Raventos Xarel-Lo—are not all that exciting. Sadly, the selection of the domestic whites is the same. While 2016 Sandhi ($113), 2014 Dumol ($140), 2017 Peay ($142), 2019 Kistler ($150), and 2015 Hanzell ($164) Chardonnays stand as good options, the 2018 Paul Hobbs ($192) and 2015 Merry Edwards ($310) that make up the high end of the range are less so. While Ever has featured Littorai before (and is set to add more to its list), they are missing names like Evening Land, Lingua Franca, Racines, Rivers-Marie, Rhys, Aubert, Williams Selyem, and Kongsgaard (though you are fine with them avoiding expensive bottles of Peter Michael). A $95 2020 Massican Sauvignon Blanc in the Other White Varietals section is attractive, but the overall section is also undistinguished.

Moving on to the red wines, Ever’s selection of Cabernet Franc from the Loire offers—like its Chenin Blanc counterparts—some of the list’s top values. While the most coveted offerings—like Guiberteau’s lieu-dits, Domaine du Collier’s “La Charpentrie,” and Clos Rougeard—have been picked off, some bottles from Guiberteau ($77-$175) and a smattering of Thierry Germain ($112-$182) remain. There are beautifully aged examples of Bourgueil from Catherine & Pierre Breton alongside Chinon from Baudry, Grosbois, Joguet, and Raffault. The average wine drinker might not have much exposure to these appellations, but such wines are destined to age well over the restaurant’s lifetime and can offer pleasure at a more accessible price point than those seen in the domestic section.

Beaujolais tells something of the same story, with its Gamay-based wines landing almost entirely between $60-$100. Though aged expressions from 2010 and 2011 have long since been exhausted, the selection still touts wines from the region’s luminaries such as Breton, Lapierre, Thivin, and Thévenet. All ten Crus are—impressively—represented with bottles from up-and-comers like Bouland, Cotton, and Sunier rounding out the category. Ever’s list might not feature quite as much Beaujolais as it does Riesling, but the former works to offer the same outward pleasure at an appealing price. Though, as with the Loire, guests may need a bit of guidance to pinpoint which Cru best caters to their respective palate.

Whereas the Beaujolais section compares to Riesling in value, the Rhône Valley does so in breadth. An opening assortment of 84 different bottles—spanning Côte-Rôtie, Saint-Joseph, Hermitage, Crozes-Hermitage, Cornas, Gigondas, Vacqueyras, and Châteauneuf-du-Pape—has now grown to 90. And that is not counting the wines that have sold out! The range of producers comprises all the top talent: Beaucastel, Chave, Chapoutier, Clos de Papes, Colombo, Guigal, Ogier, Saouma, and Vieux Télégraphe. Certainly, there are a couple dozen bottles in the $50-$100 range. But Ever’s Rhône offerings can tout six of Ogier’s 2015 lieu-dits ($330-$490), magnums of Vieux Télégraphe ($750-$1,145), and the 2010, 2012, and 2016 vintages of Beaucastel’s “Hommage à Jacques Perrin” ($1,312-$1,900). The latter bottles long stood as the list’s most expensive, and it’s interesting to see the level of investment placed into the category despite how foreboding many of the wines—in their youth—are. Nevertheless, if the restaurant is planning for the long haul, they will be sitting on a goldmine—and there are some good options that are approachable today.

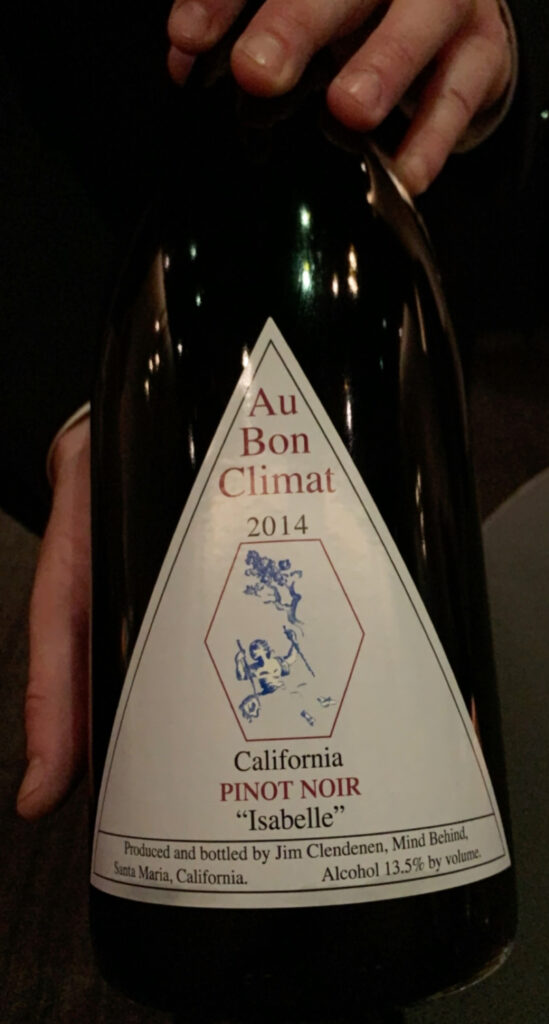

Lastly, the selection of domestic reds strikes you in much the same manner as the white wines. The Pinot Noirs—from Oregon and California—are distinguished by names such as Antica Terra ($270), Au Bon Climat ($255), Eyrie ($215), Hirsch ($230), Joseph Swan ($165), Kistler ($175), and Littorai ($205). And, in all due fairness, a wider selection of Littorai’s single-vineyards offerings along with bottles from Radio-Coteau ($145), Hanzell ($154), Peay ($168), Rhys ($319), and Merry Edwards ($210) have long sold out. But you are, once more, left wanting for names such as Aubert, Domaine de la Côte, Evening Land, Lingua Franca, Rivers-Marie, and Williams Selyem to make an appearance.

The Cabernet and Proprietary Reds sections have grown from a pittance (Philip Togni at $189 and Paul Hobbs “Nathan Coombs Estate” at $1,022 being the most distinguished of 18 names at the start) to include Silver Oak ($420), Dunn ($455), Kapcsándy ($525), Cardinale ($620-$900), Staglin ($750), Phelps “Insignia” ($760-$875), Diamond Creek ($785), Colgin ($940), Bond ($975-$1,100), Lokoya ($1,020-$1,185), Opus One ($1,155-$1,255), Vérité ($1,170-$1,230), Abreu ($1,175), Scarecrow ($1,615-$1,680), Levy & McClellan ($1,815), Hundred Acre ($2,000), Harlan ($2,250-$3,000), “Second Flight” ($3,600), and Screaming Eagle ($6,800-$8,400) itself. There is even a magnum of 2017 Screaming Eagle on offer for $14,000!

While, indeed, there are three Cabernets and one Proprietary Red under $200, the selection stands as the sort of trophy list that could rival those at Chicago’s finest steakhouses. And, to their credit, many of the selections show 6-14 years of age on them. That means they can continue to age gracefully or, in good faith, offer pleasure to customers whose fancy they catch.

The list comes to a close with a selection of aged and vintage Port (from Dows and Warre’s most notably), some Sherry, a D’Oliveira Madeira, and a few TBAs from Kracher. There are also, of course, a range of Spätlesen back in the German section (though no offerings of a higher Prädikat level). Apart from a few of the cheaper Ports ($80-$120), a half bottle of Sherry ($35), and one of the Kracher ($135), the Dessert Wine category presents an additional splurge that would only apply to certain tables. That being said, curating a list of vintage Port/Sherry/Madeira and preserving the art of their appreciation is a mark of honor for a fine restaurant.

Ever’s wine pairings launched at a price of $165 per person but, at some point, increased to $185. While there was at some point a plan to transition towards an all Riesling and Pinot Noir gimmick (an idea that can be read as either educational or reductionist), the selections you have tried have been eclectic.

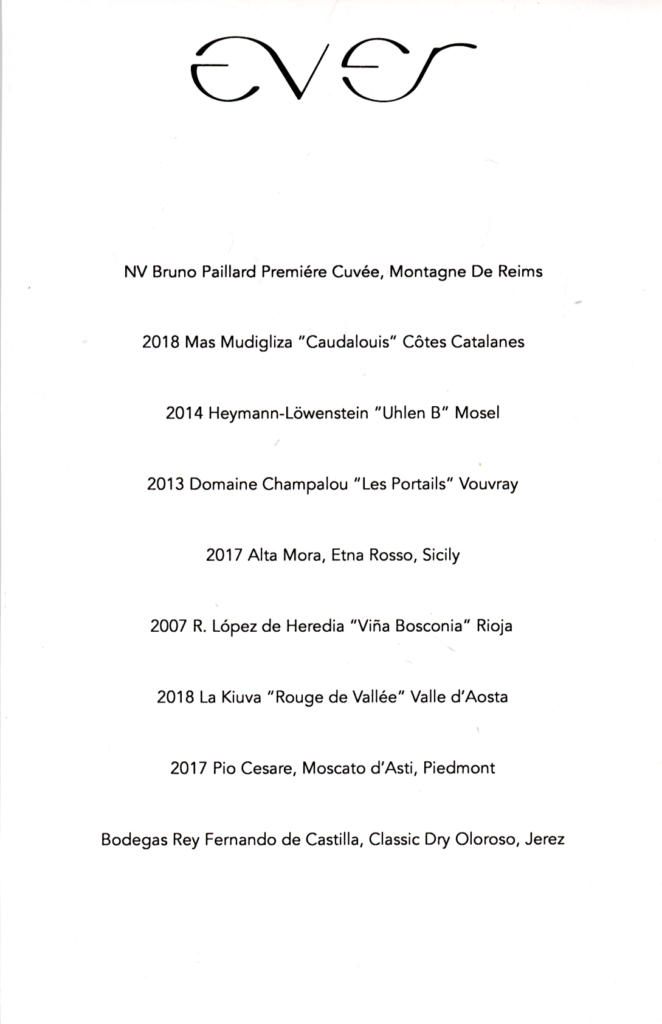

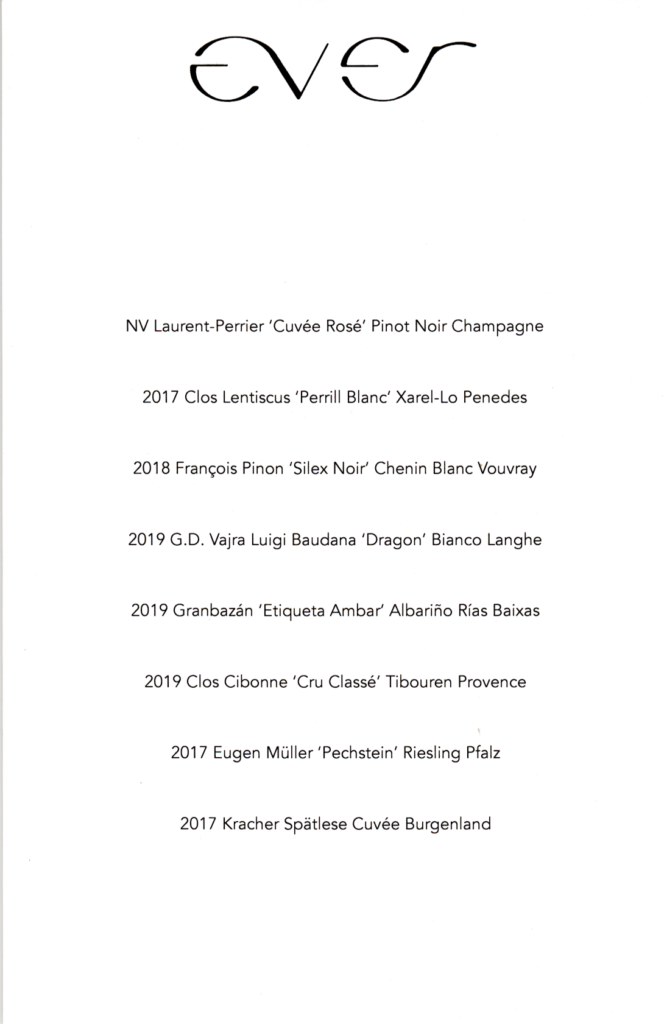

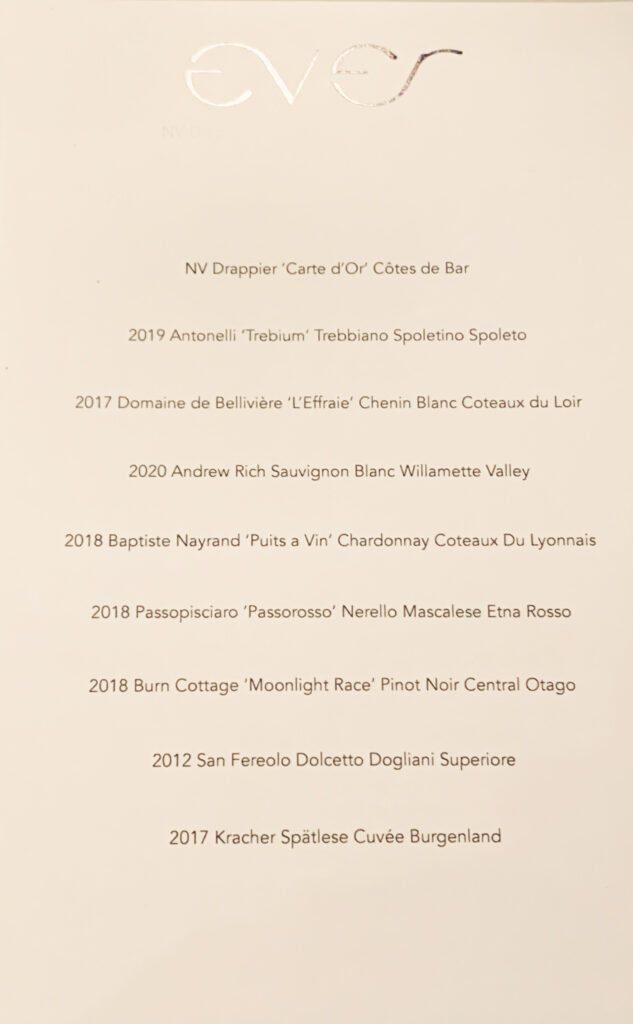

The pairing on opening night included Champagne from Bruno Paillard, Riesling from Heymann-Löwenstein, Vouvray from Champalou, Rioja from López de Heredia, and Moscato d’Asti from Pio Cesare. A pairing from June of 2021 featured Laurent-Perrier rosé, a G.D. Vajra white field blend, Clos Cibonne’s “Tibouren,” a “Pechstein” Riesling from Eugen Müller, and a Spätlese from Kracher. And the most recent pairing you tried—from August of 2021—comprised Drappier “Carte d’Or,” Antonelli Trebbiano, Passopisciaro Nerello Mascalese, Burn Cottage Pinot Noir (from New Zealand), and a Dolcetto from San Fereolo. You have found the pairings enjoyable in the context of the meal (more on that later) and appreciate Ever’s resistance, thus far, to adding “reserve” or “ultra” tiers to the equation. Faced with only one, moderately-priced option, guests can be sure that they are receiving the best possible pairing for Duffy’s food without dreaming of a more luxurious array of pours that lies beyond their reach.

Those opting for Ever’s by-the-glass selection should find themselves pleased, as the restaurant’s assortment exhibits wines of character and value rather than gouging guests with conceits like the dread Coravin pour. A 2014 Ferrari ($22), N.V. Laurent-Perrier ($24), and the same Drappier from the pairing ($28) form the sparkling options. Whites include a Chardonnay by Les Héritiers du Comte Lafon ($22), Languedoc Sauvignon Blanc ($24), Slovenian Sauvignon Blanc ($28), 2015 Robert Weil Riesling ($32), and an interesting Cassis Blanc from Clos Sainte Magdeleine in the top spot at $40 per glass. Reds comprise an Arnaud Lambert Cabernet Franc ($18), a Sicilian Frappato ($19), Gamay from Château Thivin ($23), Saint-Joseph from Chave ($24), a 2015 Napa Cabernet from St. Supéry ($32), a 2014 Nerello Mascalese ($40), and a 2017 Savigny-lès-Beaune by Château de Meursault ($48). While the restaurant’s dessert wines are less accessible by the bottle, the glass selection offers four options in the $14-$22 range alongside a set of four nicer Ports from $35-$65.

In an overarching sense, Ever’s wine program has come a long way in the year since the restaurant’s opening. The selection continues to prize accessibility and pleasure at the low end—be that through the varied by-the-glass-section, the litany of bottles (particularly Alsatian/German Riesling, Loire Cabernet Franc, Beaujolais, and Rhône) priced under $100, or the singular, comprehensive pairing priced at $185. It is heartening to see the restaurant continue to invest large sums of money in the expansion of its list; however, you must question the manner they have chosen to allocate their resources. For the most exciting bottles for an oenophile willing to splurge in the $100-$300 range (Bérêche, Egly-Ouriet, Pierre Peters, Vouette, Keller, F.X. Pichler, Guiberteau, Domaine du Collier, Littorai) have dried up. And Ever has put its money principally towards stocking additional Rhône and domestic wines in the $500+, $1,000+, and $2,000+ range.

Rather than stock every cult Cabernet producer, why not devote some of those tens of thousands of dollars towards replenishing some stock that is attractive for “wine geeks”? The sort of diner willing to pay such a premium to drink Bond at the restaurant would surely be just as happy (or happier) with Lokoya, Abreu, Scarecrow, or Hundred Acre. For they are all excellent, robust wines of a style that—in your opinion—overshadows Duffy’s intricate manner of cooking anyway. The thought of spending $14,000 on a magnum of Screaming Eagle that—at best—would pair with three or four bites of food throughout the menu makes you laugh. Tying the restaurant’s money up in that sort of inventory reflects a catering towards an obscene sort of prestige diner at a cost to the sort of customer whose enjoyment is stoked far more, relatively speaking, by being able to enjoy a great bottle of wine a more “normal” luxury price point.

You will not dwell on the extent of Ever’s mark-ups, for it is simply a premium they have decided will help make the restaurant whole. Rather, you contend that the restaurant’s list is both bottom-heavy (offering great introductory value for the first-time, only-time guest) and top-heavy (offering stratospheric indulgences for the rarefied diner) while abdicating its duty to reward wine-loving patrons who stand in the middle ground. At present, you are better served ordering two wine pairings at $185 than selecting two bottles at $200, $300, or even $400 each. In terms of age (drinkability) and producer, attractive selections simply do not exist. And, should one be dying to splurge on a superlative bottle, the list pushes such a patron solely towards prestige cuvée Champagne, young Rhône, or cult domestic Cabernet.

Ever’s wine list has aimed for a “shock and awe” sort of superficial breadth that—now that the best QPR bottles have largely disappeared—begins to fall flat. You spend time searching category after category looking for that sweet spot of vintage, varietal, producer, and price but nothing jumps out. Rather than something refined, mysterious, and exciting—something singular and emotional—you stitch together a good Alsatian/German/Austrian Riesling, a good Loire Chenin Blanc, a good cru Beaujolais, and a good Loire Cabernet Franc. Other times, you will opt for the wine pairing and supplement it with just one or two bottles from the list. You have always enjoyed your drinking experiences at the restaurant, but they inevitably feel like you’re settling on “good enough” rather than being blown away by a range of exciting options (as at Smyth and Oriole). Ever might be building the foundations for a Grand Award, but they are missing the dynamism and diversity that attract passionate wine consumers.

And much of that problem, if it wasn’t obvious, stems from the list’s spurning of proper Burgundian and Italian categories. No doubt, whites and reds from the regions appear on both Ever’s wine pairings and their by-the-glass list—a tacit admission that they are well-suited to the restaurant’s cuisine. However, those seeking Chardonnay or Pinot Noir must default to a faulty domestic selection that—as you have pointed out—is absent some of the country’s best (and most Burgundian) producers.

Though it is hard to find value in Burgundy—and the top Italian producers, likewise, have started to become priced out of reach—delivering a discerning selection within complex, popular categories should be the joy of any wine director of sommelier. When well-chosen, those coveted bottles appreciate in such a manner that the restaurant’s mark-up naturally deflates and might begin to seem like a deal. They grow alongside the restaurant—perhaps as Ever’s Riesling selection will do—offering far more potential for wide enjoyment than expensive trophy bottles whose prices largely remain stable. (Hell, why not curate a bit of Bordeaux if you are going to devote so much money to the cult Cabs? Would those “Parker palates” drawn to them and the Rhône selections not enjoy First Growths just as much?)

To your palate, Grower Champagne and Burgundy stand as the best companions to food such as Duffy’s. Other than Agrapart, Ever’s selection of the former is now lacking. And, while G.G. dry Riesling and Chenin Blanc could substitute for Burgundian Chardonnay, the bottles that can measure up to such quality are scarce. Pinot Noir, which could conceivably partner more of the menu than the tannic varietals given preference, is only represented by subpar domestic producers. And Italian wines, through Nebbiolo, Sangiovese, and Super Tuscan blends (among so many other interesting varietals) could bridge the gap between New World and Old World palates, are similarly snubbed.

What you are looking for from Ever’s list, at the end of the day, is a feeling of generosity. You crave the excitement of having too many appealing options to choose from. And, while on the surface the restaurant bombards you with the number of bottles in certain categories, many of those offerings are simply filler. For any given region only contains so many vintners producing wines of quality and character. The rest simply achieve a standard expression of their varietals in their terroir. Having neglected to replenish their stock of coveted growers, Ever is left with an assemblage of mediocrity in their chosen categories. Sure, well-aged wines—even from a modest producer—can help spur excitement in the restaurant’s chosen areas of focus. But can such bottles be attained and offered at a reasonable price?

Versus, perhaps, Ever using the weight of its reputation to secure allocations of village-level Burgundy from top producers or affordable expressions of premier cru sites that consumers struggle to attain due to their scarcity. Smyth and Oriole have gone such a route, and their wine list rewards customers with some of the most supreme drinking experiences money can buy (even allowing for the restaurant’s mark-up). Barring that, Ever could simply plunge more deeply into stocking the stuff that sells. There’s certainly enough Pierre Peters and Bérêche to go around. There’s no reason why Keller’s most modest cuvées should not always be represented on the list—or a broader selection of Stein. The list’s obsession with perceived scope falls apart upon closer inspection. Oenophiles will ultimately notice the game being played, and they will rue having had to scan through so much flotsam and jetsam to do so.

Rather than a list of treasures, Ever’s is filled with tripe. And it’s a shame because they have the fancy decanters, the glassware, the intricate cuisine, and—must importantly—the staff to do wine service justice. You have now met three different sommeliers who have worked the floor at the restaurant, and each was a credit to their profession. Ever’s culture does not indulge any intimidation or snobbery. Rather, expert knowledge is combined with an essential friendliness and graciousness that enables guests at all levels of discernment to enjoy their drinking experience. As mentioned before, those gorgeous Riedel decanters are handled with aplomb. But the bottles you have ordered off the list have also been handled proactively (you think, in particular, of a recent occasion where a young magnum of domestic Pinot Noir was astutely double decanted before your arrival). And the wine pairings themselves are nimbly described in a telescopic manner that conveys essential information to newcomers or ravishes the geeks with niche bits of trivia as required.

You only recall one occasion where Ever’s wine service perturbed you. In early 2021, on the occasion of your fifth visit and in celebration of a birthday, you asked the sommelier if you may bring in two standard-sized birth-year bottles (Burgundy, of course). Though the restaurant expressly forbids “outside beverages,” the request was kindly granted with the additional courtesy that no corkage would be charged for the party of two. Nonetheless, you ordered two bottles of Champagne from Ever’s list in a show of good faith—and also to balance the lineup relative to the food. However, shortly before dinner, you were notified by the sommelier that word came from above that corkage must be charged. And, even in light of you ordering the same amount of wine from the restaurant, the fee would not be waived in the customary manner.

Given the stated policy against allowing outside wine at all, you still appreciate that you were able to bring the bottles in the first place. And, though certainly poor form, Ever need not be beholden to the typical nicety of waiving the fee relative to number of bottles one orders off of the list. Charging corkage is—ostensibly—meant to maintain the subsidization beverage sales provide to overall costs. For a restaurant that does not allow it at all in normal circumstances, perhaps the fee asserts that the favor being granted is not one the guest should become accustomed to asking for. However, you have seen Ever repost photos from a wine group’s private dinner that contained some amount of outside wine (whatever deal was struck in that case, the restaurant felt no need to hide that the practice indeed occurs). And it strikes you as dysfunctional to force the sommelier to go back on his word over a $100 sum that represents a mere pittance relative to five prior dinners with above-average wine spend in each case.

Your guest of honor that evening was so embarrassed by the saga that they took it upon themself to covertly pay the corkage while you were up from the table—leaving you, at least for a time, thinking that the restaurant had ultimately done the right thing. While not that grievous a gesture, the back and forth was graceless. And the experience was made all the more bitter by the fact that you are still otherwise unable to enjoy Burgundy alongside Ever’s food! But an easy solution presents itself: in the future, you will simply celebrate birthdays at establishments where birth-year bottles are better welcomed.

The beverages being ordered, dinner commences.

Ever’s menu—after the server double checks for allergies or aversions—is introduced simply as Duffy’s interpretation of the season’s bounty. There’s not much else in the way of song and dance: guests’ minds and palates are left primed for the surprises to come. However, starting in 2021, diners have been asked to choose one of two options—milk chocolate or dark chocolate—before the menu commences. The “choose your own adventure” element, as it is sometimes coyly described, comes into play later on.

Before embarking on your analysis of the cuisine, you will indulge in just a bit more grounding. The “Ever Experience” is priced at $285 per person (before tax and 20% service charge) and comprises between nine and eleven courses. Stylistically, Duffy’s food is hard to pin down. Knowing the chef’s history at Charlie Trotter’s and Alinea, of course, is instructive. And Grace, no doubt, reflected his singular vision.

In the lead up to Ever’s opening, Duffy’s “creative process” was defined relative to the difficulties the chef faced sourcing ingredients during the pandemic: “to fully conceptualize a dish, he needs to have the item, say, a carrot, in hand before he can start to see it in a different, creative way that lends itself to his fine dining style.” That style, as best as the article describes it, is characterized by a “delicate touch and whimsical plating” alongside a commitment to education. Duffy’s new restaurant would “introduce patrons to ingredients they may not have previously encountered…and combinations diners haven’t seen before” while elevating “pedestrian items like butter.”

The most revealing snippet noted how the chef “sees himself and Ever as objects in perpetual motion, drawing on the power of memory to lay a foundation for his vision, yet refusing to wallow in nostalgia or misgivings about the past.” “Each seemingly minute tweak or edit” to the intricate food would be framed as a coming one step closer to the “ultimate objective — a more perfect restaurant.” Such an attitude, seemingly, prizes experimentation and the risk-taking that comes with it—“it’s too easy to do the same thing over and over….I don’t want to be a chef with a signature dish.” However, Duffy also acknowledged that some balance would be struck: “We don’t need to change just to change, but we’ve got to be moving forward constantly.”

While short on substantive details, Eater’s promotional piece made clear that Duffy is invested in a process of growth and discovery rather than merely looking to offer pleasure. As is typical of the “molecular gastronomy” style, advanced techniques are used to probe and provoke. Ingredients are not engineered to offer maximum satisfaction, but to spur a sense of intrigue—to titillate rather than straightforwardly delight. Thus, the “best ever” experience would not be shaped by the chef’s “greatest hits.” It would not be defined by luxury ingredients or preparations as they are traditionally wrought. Instead, diners would be entering into a creative process that sought further refinement, greater perfection each evening by daring. They would be stepping into a dynamic expression of Duffy’s artistic sensibility that would necessarily need to excise some of its most successful recipes for the sake of keeping “that fire and intensity, the passion” burning.

It all sounds very appealing to those who already worship Duffy as a master craftsman. But does the chef’s “best ever” realization of his creative process actually yield dishes that strike guests as offering the “best ever” flavor? Do the “best ever” ambiance, service, and wine work to enhance the pleasure offered on the plate or simply act as a buffer against what might otherwise be perceived more as artistic than gustatory fare?

You will look to untangle the style from the substance without holding Ever up to the standard of its marketing material all too harshly. For “best ever” is essentially subjective—primarily as it relates to Duffy and Muser’s past work. And “an experience of a lifetime” (another favorite phrase) does not necessarily carry the promise of clasically pleasing food. The deeper question—of course—is how does the restaurant manage customer expectations to ensure they leave happy? And, to what degree does the restaurant harness novelty for the sake of charming a mass of first-time, one-time guests who are generally unequipped to critique the meal? As always, penetrating gastronomic mystique demands careful study across multiple experiences.

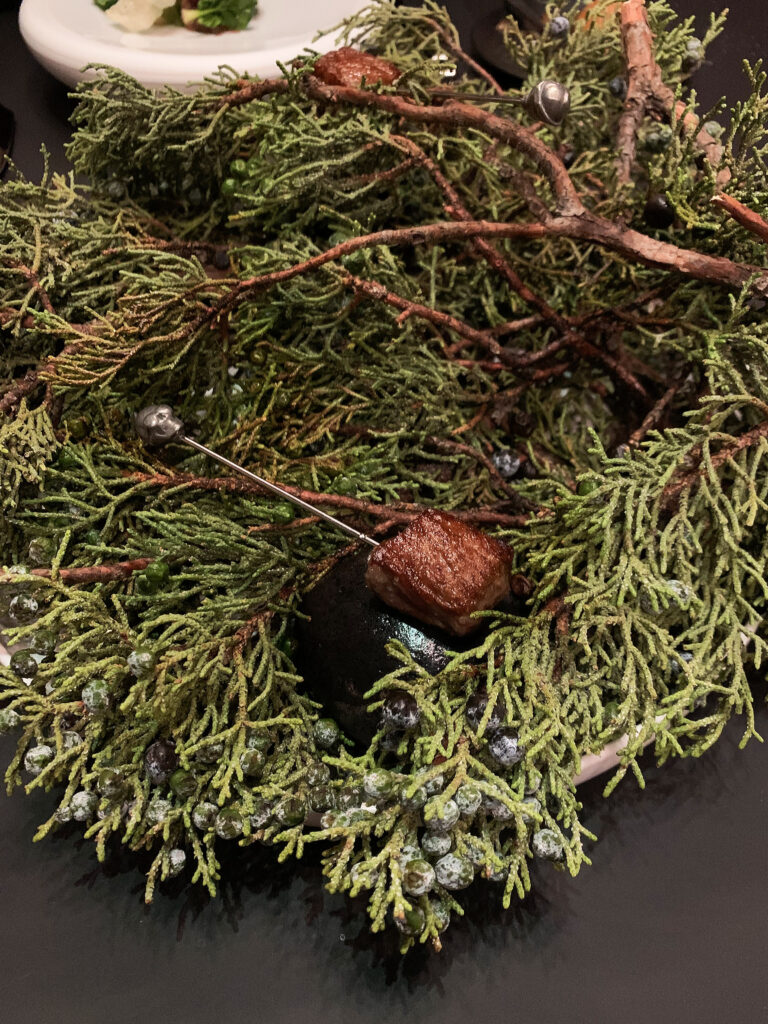

Ever’s menus from 2020 and early 2021 began with canapés. On one occasion, a ceramic sculpture was set before you then pulled apart to reveal three different serving vessels. Another presentation made use of an altogether abstract material that looked like burnt plastic—and, into which, were stuck three skewered bites and a small bowl. Yet one more—in a more familiar molecular fashion—staged the bites and two shot glasses on the rim of a clear bowl from whose center rose an encompassing fog. Finally, an April tableau showcased a more naturalistic style in which the ridges of a giant pinecone (itself nestled in a cradle of branches) held the variety of bites.

Truth be told, you can only recall the constituents of that last set of canapés. (Of course, that has something to do with the fact that it was the only occasion those bites made it onto the printed menu). The pinecone contained a small orb of Charentais melon—hollowed and filled with a sort of cream—a topped cracker, a delicate savory cone (reminiscent of Thomas Keller), and something that looked like a Chinese sesame ball. The stated flavors on the menu—despite you not being able to match them with their representation—were “charentais, truffle, pine nut, sunchoke.” And you can certainly appreciate the juxtaposition of the pine’s nut relative to its cone—alongside kindred “root” elements like the sunchoke and truffle.

These charming canapés—once upon a time—set the stage for the meal to come. The modular nature of the presentations meant that the kitchen could more easily swap ideas in and out without having to develop an entire plating. Thus, the bites could strike closer to the very moment of the season than a full-fledged dish that might stay on the menu—in some form—for much longer. The canapés, in some sense, replaced the hanging ingredients that were originally intended as an interactive introduction to the restaurant. You think they were the most successful when grounded in the natural world rather than attached to the abstraction pervades the rest of the experience. But, at the same time, you cannot remember a single one of those canapés that really struck you and stuck in your memory. They were pleasant and engaging without ever exactly dazzling. So you can understand why this element of the meal was ultimately cut in favor of simply delving straight into more composed creations.

The first plated dish of Ever’s menu—throughout the four meals you experienced in 2020—possessed a great deal of visual flair. Originally titled “Osetra Caviar,” the preparation comprised a nugget of king crab topped with the titular roe sitting in a pond of green cucumber gel. The chunk of crustacean was joined by spiral twirls of the vegetable, dollops of cream, some citrus lace, a solitary cashew, and a couple powdered substances. Ever’s logo was set into the very middle of the cucumber gel in a lighter tone of green. And, surely, the plate’s photogenic quality could not be ignored. Captured and posted onto social media countless times, the jewel of crab and caviar reflected a double delight of luxury. The miniature accompanying elements—each offering but a singular, dainty bite—showed the fine level of detail to which the kitchen aspired. And the branded cucumber gel—alien in its color and texture—ensured that any beholder would know exactly where the dish was served.

Ultimately, “Osetra Caviar” would become “King Crab” as the roe—now sourced from trout—was relegated to secondary status. The rest of the dish would remain the same, perhaps with an extra cashew or another attractive microgreen added to the mix. But the experience of eating it was the same: you’d puncture the cucumber gel and savor its pristine, sweetened flavor. The roe-topped crab would go down in one bite, then more gel, the nut, the cream and herbs and those crunchy spirals of the raw cucumber.

Really, the “money shot” would come right at the beginning and then you’d be left with a shallow bowl of Jell-O. Neither crab nor caviar resonated—in that sole bite—deeply enough to carry through the rest of the dish. And, while it felt fun to deconstruct such an intricate staging of bits and bobs, it was the headlining luxury ingredients that actually held the least presence. As an obscene bite staged for promotional purposes, the crab and caviar would certainly raise eyebrows. But the dish would have been more successful had the crustacean and roe elements been more amply spread throughout the base of gel. (Of course, that would run the risk of detracting from the Ever logo’s framing).

In the final analysis, the king crab and osetra in the dish acted as little more than luxury totems. Perhaps that’s why, wisely, the osetra was ultimately substituted for something more cost-effective. For Duffy did not demonstrate an ability to derive any particularly intense flavor from the ingredients. Rather, they were bit part players in an attractive presentation that could catch the eye and concisely tell the restaurant’s story on social media. While the dish fed a digital audience some vision of luxury, it did not succeed in delivering any kind of outrageous flavor or texture to the palates actually tasting it. “Osetra Caviar / King Crab” stood as a superficially—rather than substantively—pleasing start to the meal when it was served. A pairing of Champagne, as you might imagine, completed the illusion.

Starting in 2021, “Osetra Caviar / King Crab” would be replaced by a different dish titled “King Crab” that was used to begin the meal. The crustacean was again paired with cucumber; however, sudachi (a mutated variety of yuzu) and lemon balm now formed the accompanying elements. And the presentation, too, was something altogether different. Rather than emblazon Ever’s logo in green gel, Duffy dug up one of his signature preparations from Grace. (In fact, you have learned that the dish can be dated all the way back to the chef’s time at The Peninsula).

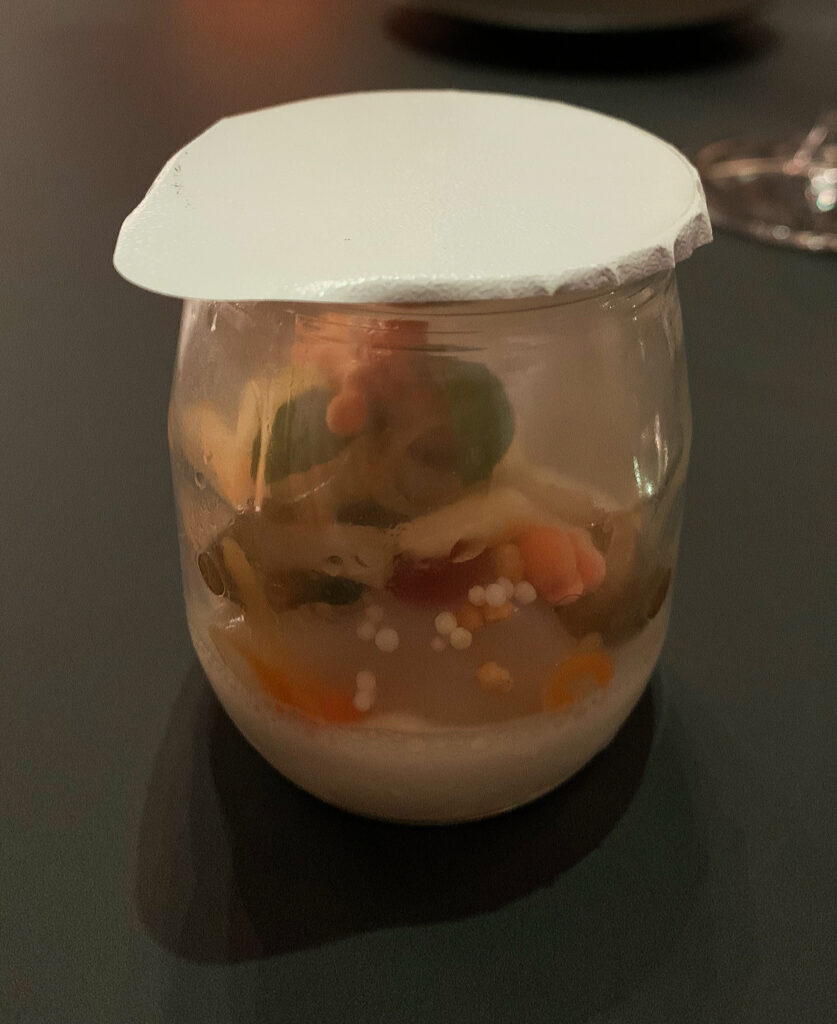

Guests are met with a conical crystal bowl that narrows at the bottom. A cap of sugar glass stretches just beneath the vessel’s rim. Impressively, it holds the weight of some trout roe, a gel made from the sudachi, sprigs of the lemon balm, and a couple dollops of unidentified cream. You are instructed to use your spoon to shatter the “glass,” sending its contents for a swim in the cold broth made of cucumber that sits below. Therein, one finds the titular “king crab”—rendered here as a healthy few chunks of meat with far greater presence on the palate.

There can be no doubt that this is one of Duffy’s legendary constructions. The dawning realization that one must break through such an intricately staged layer of “glass” to complete the dish is hard to recapture. But you find the process just as pleasing each and every time you are met with the preparation. The “shatter” texture of the broken shards is almost entirely unrepresented in any other composition. They impart a crunchy sweetness that plays off the pop of the roe, the sourness of the sudachi, the moist chunks of crab, and the all-enveloping refreshment of the cucumber broth. All the elements work to showcase the crustacean’s own latent sweetness, and—without any need of buttery or nutty notes—the dish still feels substantial.