By and large, I enjoyed what I tasted at Oriole back in September. Certainly, there were dishes that could be improved (I recall the sickly sweetness of some bites, the stale texture of another, and a dessert sequence that ended all too abruptly). But I found, at core, a kitchen that was meaningfully evolving its offerings without totally abandoning its signature recipes (or, more importantly, the crowd-pleasing decadence its cuisine has long privileged).

After many months away, I felt the restaurant remained worthy of its place at the very pinnacle of Chicago dining. At the same time, Oriole was still not consistent or distinctive enough to rank alongside the best national or international expressions of gastronomy. Setting, service, and beverage program aside, its work was not yet equipped to transcend its status as a safe, approachable choice in a city whose two- and three-Michelin-star concepts can be polarizing. In short, what makes Oriole so appealing to first-timers and locals (i.e., a roll call of luxury ingredients attuned to conventional pleasure) is exactly what stymies it in the eyes of repeat (or otherwise more worldly) patrons.

Nonetheless, chef-owner Noah Sandoval seemed to be taking those first steps toward defining a more novel, legible, and singular identity. With the benefit of the remodel now long behind them, the team—itself centered on a new nexus of talent—can only hope to invigorate the space with ingredients, techniques, and courses that guests have never seen before.

The early fruits of this process have suggested that the restaurant, more than nine years later, is up to the task. Yet, with Oriole’s 10-year anniversary looming in March, I’m not sure total reinvention would or should be the goal. Indeed, Sandoval’s former collaborators have just earned two Michelin stars of their own, suggesting that the concept’s heritage and style of cookery (even when refracted through a Filipino lens) remains relevant as ever.

So, maybe what we are looking for is not a rejection of what’s made Oriole great but, rather, a distillation and reinterpretation of the kitchen’s favorite sensations. The team, by that measure, should not totally kill off its signature recipes and rob new customers of the joy they continue to yield. However, I would like to see the restaurant make the leap from being a place diners are content to visit once per year to one that really entices patrons to taste the changes each new season or month or week brings to the table.

Put another way, the goal is not to make Oriole more like Smyth. It’s to make Oriole a better version of itself: with a louder voice, an elaborated culinary language, and the kind of dynamism (moderated by an ironclad focus on guest pleasure) that yields new hit dishes visit after visit.

Ultimately, it’s not for me to define what path the chef will take. Yet, I like what I’ve seen so far, and the journey is one worth embarking on—and sharing in—whatever direction it takes.

Two months later, where do things stand?

Let us begin.

At this late stage of the year (and continuing through the winter), even the very earliest of Oriole’s seatings are treated to a dusky—if not altogether dark—walk through the alley-like confines of Walnut Street.

I won’t bother dwelling (yet again) on the weathered brick and oversized windows that characterize the restaurant’s surrounding structures: a callback to the neighborhood’s industrial origins that have, elsewhere, all but disappeared.

It is enough only to say that the transition here—from cold and snow, the leer of streetlights, and the uncertainty of just where to go, to a warm greeting, a hot cup of tea, and a Disneyfied “ride” in the elevator—remains Chicago’s most poignant. And the wider ambiance, once one weaves a path through the lounge and the kitchen into the dining room, does a skillful job of blending what is worn, original, and a little grungy with the kind of sleekness and spaciousness that smacks of luxury.

Still, the devil is in the details, and it is in those innumerable nods to pop culture (predominantly musical) that Oriole takes flight: as an undeniable expression of the chef-owner’s personality even when his manner of engaging guests remains cool and sheepish relative to the more boisterous toques in town. Album covers and tour posters and the occasional baseball artifact also serve to orient the practice of hospitality more broadly.

Yes, they speak to a common artistry—the mastery of technique through repetition, the pressure of performance, the high of success—that resonates for anyone who shares the same passions. But they also juxtapose high- and lowbrow in a way that consciously subverts the minimalist, molecular temples of gastronomy that have defined fine dining in this city.

Smyth, in its own way, has transcended such a model with an intimate, wood- and brick-lined room that trades any seriousness (of ambiance) for cuisine of a singular, mind-bendingly creative style. However, Oriole works more in the realm of expectation—welcoming guests into a space that feels special, plying them with every one of those luxury ingredients they’ve dreamt of tasting—while defusing that same expectation of any suffocating pretension.

The kitchen ceiling serves as a reminder, to servers and served alike, that this experience looks to draw out who you really are and honor your true proclivities (like dressing down, drinking beer) rather than compel obedience or posturing under the specter of that $325 ticket price.

As a consequence, interaction with the staff (despite a continued flow of new faces) retains an essential naturalness and good humor that never feels uncanny. Instead, captains embrace a sense of curiosity and are granted the time and space to linger, engage further, and strike the kind of deeper connection (extending well beyond the rudiments of the meal itself) that colors hospitality as something more than a mere commercial exchange.

Tonight, I enjoy observing the team cater to a single diner: fielding their questions and even sharing a recipe for the pickled Sungolds that appear in one of the evening’s dishes. Otherwise, when it comes to my own table, I admire how conscientiously some of the newer figures in the dining room solicit and accept feedback—a rapport that can be challenging to establish yet proves highly rewarding for both the customer and the kitchen in the long run.

In deciding what to drink, I continue to be impressed by the growth of the wine list from visit to visit. Truth be told, the vast majority of patrons opt for one of the pairings when dining here, so anyone ordering bottles benefits from a selection that, while fairly dynamic, does a good job of holding onto its inventory.

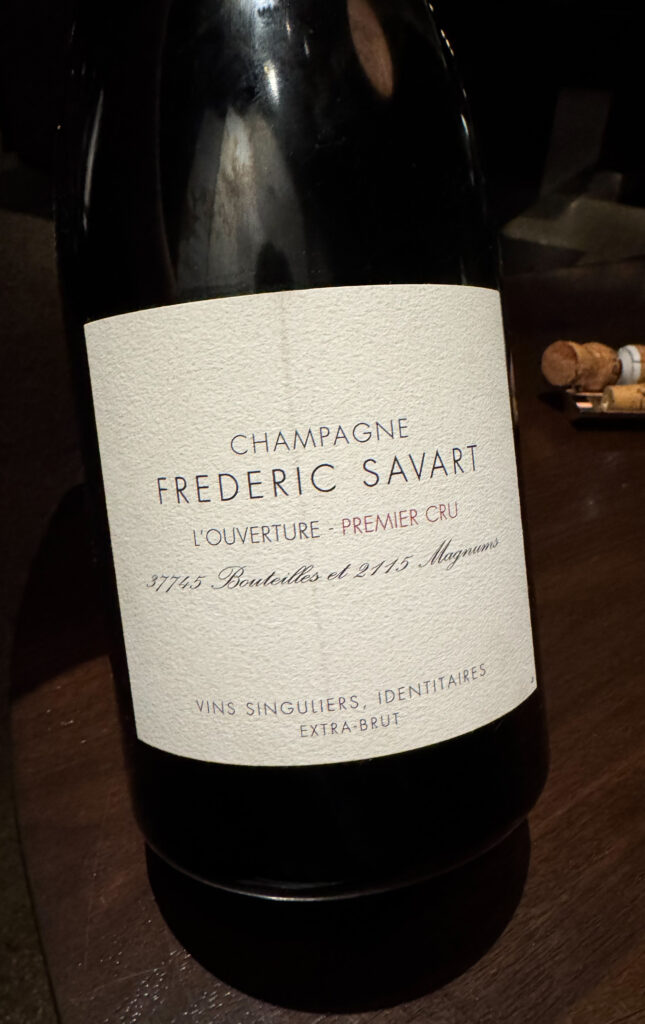

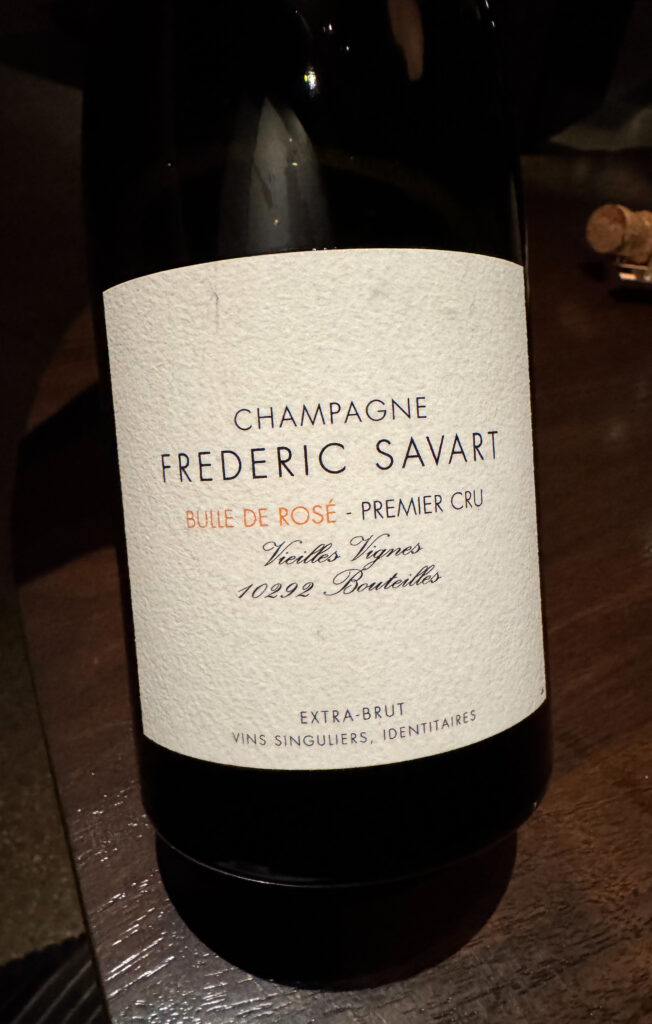

On this occasion, I opt for a magnum of Frédéric Savart’s “L’Ouverture” ($260 on the list, $195 at local retail) alongside a bottle of the same producer’s “Bulle de Rosé” ($151 on the list, $120 at national retail). Not only are these markups minimal (premiums of just 33% and 26% respectively), but beverage director Emily Rosenfeld’s curation of the chosen wines (which included two Burgundies brought as corkage) was excellent.

This was not limited to simply introducing the right bottle at the right time (something always handled with precision at the restaurant). Rather, she made the bold choice of reserving the sparkling rosé for dessert, where it paired brilliantly with flavors of citrus, ginger, and squash across a range of preparations.

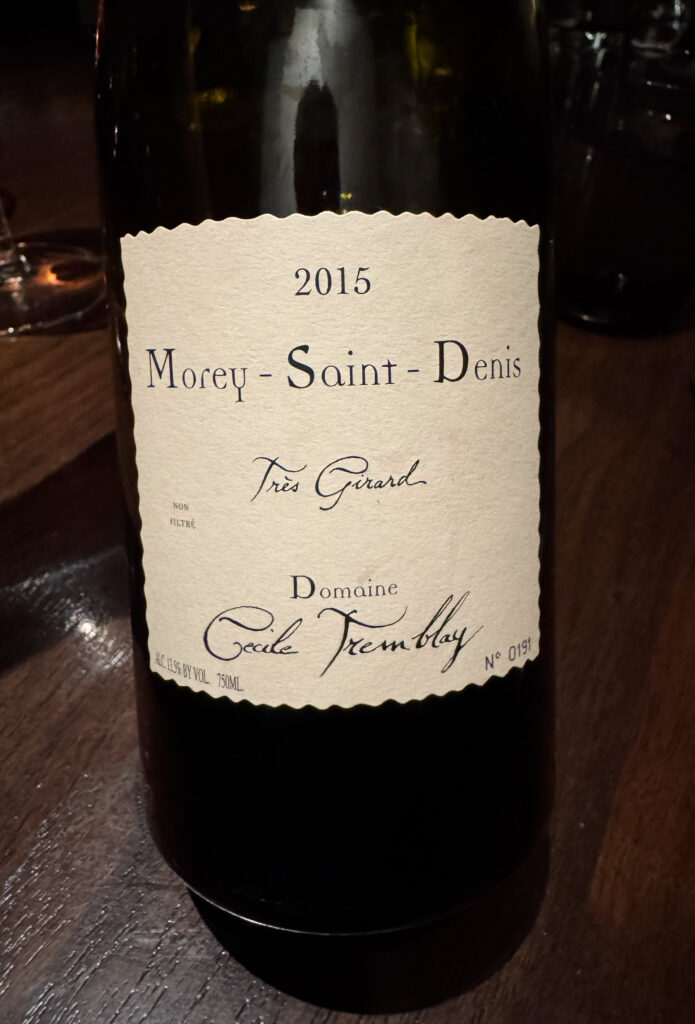

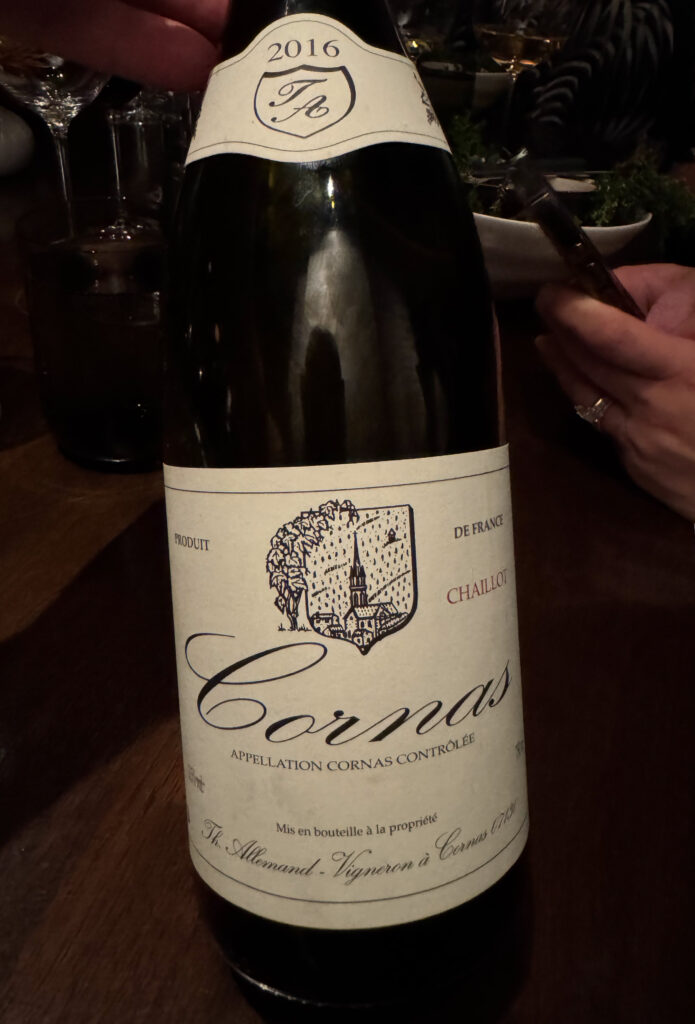

Pours of Cecile Tremblay’s 2015 Morey-Saint-Denis “Trés Girard” and Thierry Allemand’s 2016 Cornas “Chaillot” (each taken from the “Reserve” pairing) were also kindly shared, providing the table with more options to explore as we enjoyed the menu’s principal servings of protein. Of course, these selections also confirmed the quality of producer and degree of age that features as part of the lineup. Tasting both of these wines (which retail north of $300) on top of whatever else is offered feels like a great value at $350.

Rosenfeld also showcased what is meant to be the meal’s final pairing: a glass rinsed with Jean-François Ganevat’s “Vieux Macvin du Jura” then filled with Krug’s “Grande Cuvée 173ème Édition.” I’ve never seen this kind of technique (which borders on sacrilegious depending on how highly one thinks of the latter Champagne) featured before. Nonetheless, it worked beautifully: bolstering the bubbly with added texture, oxidation, and honeyed fruit from the fortified wine.

Overall, Oriole is still not quite looking to push boundaries with the kind of limited, natural offerings one finds at Smyth, Elske, or Cellar Door Provisions. Yet the restaurant excels—and continues to forge new ground—in its established niche: classic wines, offered at a generous price, attuned to food that surprises and delights guests in a manner that really does match the excesses that more polarizing winemakers (as much as I love their work) sometimes pursue.

In short, the program here, when one also considers the cocktails, non-alcoholic options, and that $50 corkage, remains a perfect fit for the style of dining on offer.

Tonight’s menu kicks off (as it always does) with a trio of bites served in the lounge.

First to arrive is a “Lamb Tartare” made using meat from the animal’s loin. The small chunks are tucked into a tart shell made with the ruminant’s fat and dressed with sherry vinegar and a fennel pollen aioli. A tangle of squash noodles forms the finishing touch: lending the presentation some curves and color while also doubling its crunching textural effect.

Once the tart shell shatters, the lusciousness of the lamb comes to the fore. The pieces glide across the palate, moisten one’s tongue, and then seem to melt away. However, they leave behind a rich, carnal quality that, enlivened by the tang of vinegar and a hint of anise, is almost reminiscent (as one server suggests) of “sausage pizza.” Of course, the sensation here is quite more refined, yet the degree of satisfaction delivered by this morsel is worthy of the comparison. Overall, this tartare is tied for my favorite of the opening bites, and it represents a marked improvement from the saccharine recipes I encountered in September.

The ”Carabineros Prawn” that arrives next takes a familiar form, being stuffed inside the kind of pie tee (colored on this occasion with activated charcoal) that characterized the lounge sequence in the early days of Oriole “2.0.” On the back of the lamb fat tart, this thinner, crisper shell feels a touch redundant. That said, the vessel is used to develop a unique flavor expression: one that balances a more conventional Malay influence (provided by Buddha’s hand jam) with Japanese notes of sudachi and yuzu koshō.

For my palate, the combination—which, in theory, should charge the shellfish with sweet, tart, tangy, and spicy intensity—falls flat. Structurally, it might just be difficult for the Carabinero (however prized for its own savory depth) to measure up to the preceding lamb and not seem comparably muted. Nonetheless, the texture of the prawn (so beautifully plump) opposite the brittle pie shell is certainly attractive. And, in sum, I find this bite likable even if it does not reach the level of being memorable.

Thankfully, the “Bluefin Tuna” (tying the “Lamb Tartare” for my favorite of the bunch) seals the quality of the opening sequence. I actually tasted this preparation last time, and the core elements—white miso, coriander, and Sungold tomatoes (sourced from Michigan) rendered three ways—remain the same. Yet the introduction of some habanada pepper (that is, a heatless habanero) now helps the recipe achieve greater balance.

Texturally, the Atlantic-sourced tuna displays a soft, yielding mouthfeel that coats the tongue in a layer of melty fat. Miso helps to amplify the belly cut’s latent umami just as the bursting Sungolds provide the perfect counterpoint: washing over the richness with citrus-tinged (from the coriander) acidity and a fruity, subtly sweet finish. In fact, I think the floral and tropical tones of the habanada actually help to soften the tomatoes’ natural sugars, ensuring that this bite lands firmly on the savory side despite the assembled ingredients. Ultimately, this makes for a clear improvement on September’s example (that erred on the side of over-sweetness) and one of the meal’s early highlights.

Upon leaving the lounge and taking a routine stop at the kitchen’s counter, I am met by the “Hudson Valley Foie Gras.” This recipe, now close to five years since Oriole’s renovation (and its introduction), might rank as the restaurant’s most totemic. At its best, the combination of a brioche base (cooked in yeasted butter), liver parfait, seasonal fruit, pink peppercorn, oxalis, crème fraîche Dippin’ Dots, and gold dust (for visual effect) stands among the finest bites being served anywhere in Chicago on any given night.

Tonight, the Michigan blueberries that featured back in September have been replaced by California figs. Personally, I am partial to the latter fruit’s richer, more caramelized character for this kind of sweet/savory preparation, so I expect the present example to be among the strongest I have tasted. On the palate, the figs’ faint chewiness is to be expected. However, the foie gras itself feels a touch frozen and, thus, lacks its usual effusive (and highly enjoyable) creaminess. When it comes to flavor, the contrast of tang, honeyed sugars, and subtle sharpness against the liver’s concentrated savory notes is effectively managed. But, at the end of the day, the textural problem I noted prevents this toast from fulfilling its full potential.

Making my way to the table, I encounter the team’s latest showcase of “Golden Kaluga Caviar.” During my last visit, the roe (paired with peas, green garlic, and lobster) formed a dish I liked but did not absolutely love. On this occasion, a base of smoked crème fraîche, some slivers of razor clam, and dots of green apple gel promise a completely different experience.

At face value, I appreciate that the kitchen has completely retooled its vision for this coveted ingredient (so synonymous with luxury). Unfortunately, with the present set, I believe they have taken a step backwards. Texturally, the tenderness displayed by the pieces of mollusk is actually impressive, and there’s nothing wrong about pairing the pop of caviar with a creamy base. That said, any butteriness, nuttiness, or brine the golden Kaluga might offer is obscured by the smoky, tangy, and tart-sweet notes that dominate the dish. Truly—other than visual appeal—it’s hard to sense the roe’s presence at all.

The end result tastes like something that would be served at Ever (minus any of the fancy plating). More specifically, there’s an overriding brightness and greenness that robs the starring ingredients (both the razor clam and the caviar) of their essential pleasure. Ultimately, this effect runs contrary to what Oriole is known for, but I will admit (if the proportions and power of the accompanying elements were dialed back) the chosen combination could be more successful with further tinkering.

Arriving next, a preparation of “Badger Flame Beets” (a variety in which the ingredient’s polarizing earthiness has been almost entirely bred out) is largely unchanged from last time. Only the presentation of the dish (its concentric curls of peach and the root vegetable now being arranged more loosely, like a flower) has seemingly been altered. Otherwise, the supporting notes—drawn from a sake lees sorbet and some chamomile—remain the same.

I actually enjoyed this recipe last time, and my only hang-up had to do with the fact that its ripe, fruity character tasted monotonous after so many jarringly sweet seafood preparations (the very kind, as mentioned earlier, the kitchen has remedied). Though I appreciated the prestidigitation involved in making beet eat like peach, I also thought the combination would have made more sense as an early dessert.

But tonight, structurally, the team has kept its use of sugar in check, so the sweetness and juiciness of the peach (balanced by the cheesy, almost tropical qualities of the sorbet) actually lands successfully. Each bite feels bracing on entry but yields to a more soothing finish—one in which the carrot-like character of the Badger Flame and clean, floral tones of the chamomile add complexity. Overall, this makes for a course that is both cohesive and pleasurable. Further, by contrasting the savory fare so clearly, it reinvigorates one’s palate for what else is to come.

I also encountered the “Uni Infladita” during my meal in September, appreciating its ingenuity yet finding that the bite was undone by a certain staleness in its puffed tortilla base. Tonight, the kitchen has been granted another chance to impress: one that blends chunks of Australian tiger prawn, fermented watermelon radish, and morita chili (as before) with the shio koji-glazed sea urchin.

Texturally, the “Infladita” combines a crunchy (not at all stale) outer shell with hints of plump shellfish, crisp vegetable, and the encompassing creaminess of the starring uni. So far so good. The resulting flavor starts on a note of corny sweetness that finds a kindred quality in the prawn and reaches its peak with the briny, umami-tinged sea urchin. In the background, one finds a mild, smoky, but impressively persistent heat whose fruity tones meld well with the other ingredients. Ultimately, while I think this bite could be even more explosive (though surely this is dependent on the vagaries of sourcing), it is beautifully packaged and generally pleasing in this instance. Good improvement.

The “Matsutake Custard” has formed one of Oriole’s staples since the remodel, placing the dish in the same hallowed category as the “Hudson Valley Foie Gras” and maybe even the “Capellini.” Conceptually, I find that honoring this prized mushroom (one that the Japanese themselves adore) is an admirable choice relative to all those conventional luxury ingredients that feature on the menu. At the same time, this is a dish I’ve broadly liked over the course of many encounters but never absolutely loved.

Here, the matsutake is sliced into thin curls (which serves to moderate its often-chewy texture), and paired with ingredients like ginger, tarragon, chicken consommé, white truffle, and tarragon that are meant to incorporate the mushroom’s unique, piney flavor into a more decadent construction. On the palate, the richer deposits of custard and liver play well with the warm broth and the crisp, gossamer toppings. Typically, the resulting sensation is savory and earthy in a manner that feels somewhat muddled but, overall, delivers a pleasant enough richness. However, in this case, the consommé is marked by an overriding astringency (akin to oversteeped tea) that obscures each of the other elements.

This seems like a clear technical flaw, and those are bound to happen during the long lifetime this recipe has been granted. Nonetheless, I think it offers a good opportunity to ask what this dish (even at its best) hopes to offer, and if it is really worth drawing on foie gras and truffle (which appear elsewhere on the menu) just to make the matsutake, in this form, palatable.

Thankfully, with the arrival of the “Norwegian Fjord Trout,” the meal takes a new and exciting direction. At core, the preparation is meant to replace the “Turbot” and “Pumpkin, Turbot, and Squash Doughnut” course I encountered last time that, while quite enjoyable, still retained traces of the older “Sablefish” constructions. With the present fish, the kitchen turns over a new leaf: pairing a pristine fillet with segments of crispy skin, bourbon barrel smoked roe, Thai basil, and a broth made from preserved habanada peppers.

The resulting dish marries the supreme butteriness of the trout’s flesh with delicate textural contrasts (a subtle pop and an airily crisp crunch) formed from the same ingredient. However, it is the resulting flavor that really shines. First, the fish’s latent sweetness is teased out by the smoky, briny roe. Then, the warm broth takes hold: charging the luscious fillet with tangy, fruity notes that take flight when infused with the anisey depth of the Thai basil. The sum effect drives the trout’s sweet character to a level of lip-smacking intensity without (thanks to the supporting elements) feeling confected. It also manages to do so without invoking the kind of richer, dairy-based sauces utilized with the sablefish and turbot.

While no doughnut or milk bread is served alongside the plate, I actually (for once) do not miss them—so confident and satisfying is this new creation. Well done!

Back in September, Sandoval’s signature “Capellini” made way for a highly pleasurable “Risotto” that captured all the essence of the original dish. I found this change to be a sensible one given that it subverted the classic item’s form (something exciting for repeat patrons) without abandoning the core flavor combination that has, for so long, satisfied the restaurant’s guests.

Tonight, the “Capellini” returns in all its glory: yeasted butter, caraway, puffed wheat berries, parmigiano, and a generous shaving of white truffle. I hesitate to see the chef revert to a recipe he has served countless times (right when it seemed he was on the precipice of making some kind of permanent evolution). However, given the fact that the kitchen has successfully debuted more than few new preparations tonight, I do not fault it for holding onto a couple stalwarts (namely this pasta and the foie gras).

All it takes is one bite—so fragrant, so creamy, and loaded with roasted, toasted, nutty complexity that perfectly frames that haunting garlic musk of truffle—to convince me. The “Capellini,” indeed, outdoes the “Risotto” by a degree or two, and it totally trounces the “White Truffle Tajarin” I happened to sample at Monteverde earlier this morning. My only regret is that Oriole does not serve any bread to sop up the accompanying sauce. Still, this remains a triumph.

At this point in the evening, I expect the meal to veer toward wagyu beef and for the savory section of menu to reach its conclusion. I’ve often found this sequence to be a bit abrupt (which surely has something to do with how tight the kitchen’s pacing is). Per a recent interview, it’s also intentional: an expression of Sandoval’s desire for patrons not to “roll out of here” or be “lethargic” but to incorporate their Oriole experience into a larger night where (for example) they can “feel good, go out, get drunk, [and] order a pizza” to cap things off later. Maybe even a Pizza Friendly Pizza?

I can respect the chef’s thought process, for it fits the restaurant’s overall identity as an approachable, reliably enjoyable expression of fine dining that avoids polarizing extremes. However, taking satiation out of the equation, I do still think the transition from fish to truffle pasta to beef leaves anyone ordering a nice bottle of red wine with only a few mouthfuls that actually pair well. Also, with the bread and the doughnuts and the ham sandwiches all excised over the past couple years, I do think a returning guest might feel they are getting “less” of Oriole despite (if one goes back to 2023) an increase in price.

Whatever the subtext, I find the introduction of the “Rocky Mountain Lamb Belly” to be a rousing success. The slab of meat—prepared in a pressé (or pressed) style—sits atop a potato purée with accompanying flavors of figwood-smoked beet, lingonberry, and juniper (the latter of which also perfumes the dish).

Texturally, the belly feels beautifully tender, with layers of juicy flesh offset by seamless streaks of rendered fat. Though the lamb seems to melt away, it leaves behind a hint of earthy, savory depth (what some may call gaminess) that melds nicely with the bright sweetness of the accompanying beets and berries. For my palate, the combination comes off just a little too tart. However, with the incorporation of the potato, the recipe remains rich, smooth, and satisfying. Overall, this is a great addition to the menu: one that extends and enhances the closing savory sequence while (importantly) not treading any the same ground as the forthcoming beef. The dish also empowers Rosenfeld to make a textbook pairing—the aforementioned 2016 Cornas “Chaillot” that, wielded with this kind of recipe, is simply magical.

The “A5 Miyazaki Wagyu Ribeye” that arrives next retains the same form I encountered back in September. The steak itself is dressed in a mustard seed-studded veal jus and comes surrounded by servings of horseradish cream, togarashi-dusted spinalis, stewed eggplant, pickled turnip, and mustard greens. Given the generous serving of meat (a rare virtue when working with this kind of luxury ingredient), diners are free to mix and match the various components to form a series of distinctive bites.

Foundationally, the combination of jus and mustard seed ensures that the ribeye—marrying pleasing weight with bursting veins of fat when it meets one’s teeth—smacks of deeply savory flavor while benefiting from gentle, contrasting sharpness. The steak would already be superlative if the kitchen left it at that. However, the introduction of the smoky-sweet eggplant drives the wagyu toward a shocking degree of decadence. I like the horseradish cream and the mustard greens (for their cleansing effects) too. The spinalis (charred and chewy) is good (but not great), and the pickled turnip, for my palate, gets totally lost in the shuffle. Despite this (and considering the quality of the starring ingredient), I still love tasting my way through the plate. The core concentration provided by the veal jus, mustard seed, and eggplant is just that memorable.

Yes, though I roll my eyes whenever I’m served A5 wagyu (such is the degree to which it has oversaturated fine dining over the past decade), I cannot deny the variety and deep enjoyment conjured by this presentation. On this occasion, it ranks as the very best of several excellent dishes on offer.

Tonight, the turn toward dessert sees the restaurant welcome Kyra Farkas back into the fold as executive pastry chef. Touting experience at Tartine, Elske, and Ever, she first joined the Oriole team in 2023 and, now, returns after a sojourn at The Redlock Farm (in The Netherlands) and three-Michelin-star Restaurant Jordnær (outside of Copenhagen).

Farkas affirms her talent from the very first bite: in this case, a “Rosemary Ice” said to be inspired by the rosemary bushes and lemon trees she grew up alongside in Florida. The dish combines a granita and infused olive oil made from the former herb with a base layer of custard and some pâtes de fruits flavored with the latter fruit.

At face value, this recipe seems to be one of those icy palate cleansers that shocks one’s tongue far more than it actually pleases. This is to say, the course is practical rather than memorable. Nonetheless, upon plunging my spoon into the bowl, I am met by a series of refined textures (brittle, creamy, oily, chewy) and a flavor that is not only refreshing but actually comforting in its expression of sweet citrus. Yes, there’s not a bland or watery mouthful to be had—just the kind of deep, layered pleasure that testifies to the pastry chef’s comprehensive vision.

Arriving at the principal dessert, I am left wondering if the kitchen might finally shake a series of tepid performances. Yes, in a manner not unlike my earlier critique of the fish, pasta, and wagyu sequence (remedied by the debut of the lamb), I have often found that the sweet side of Oriole’s menu also ends abruptly. It has (following the retirement of the “Délice de Bourgogne Soufflé”) failed to tap into the same convincing decadence, and, while I respect the effort to move past one of the restaurant’s signatures, such a recipe needs to be adequately replaced. Indeed, while I liked the “Carrot Cake” I sampled back in September, I was left feeling that the dish (subverting the form’s usual richness) would have worked better as an opener than a closer.

The “Golden Milk,” at long last, reverses this trend: anchoring the meal without in any way sacrificing creativity. The preparation centers on a cardamom-, cinnamon-, ginger-, and turmeric-spiced ice cream paired with pistachio praline, a dark chocolate baba (brushed with Nikka Coffey Grain whisky), and a nest made from strands of the same chocolate.

Texturally, the dish centers on a conventional contrast between the smooth ice cream, crunching nuts, and spongey cake (in short, the kind of nostalgic construction that screams “dessert”). However, the burst of warming, earthy notes that lands on the palate feels unique and unexpected. One wonders, for a moment, if the spices will work to overshadow the desired decadence. But then the caramelized pistachio comes in, then the baba, and the whole bowl takes on a flavor of rich, spiced, almost figgy dark fruit with a profound, cocoa-tinged finish. In short, the “Golden Milk” scratches every itch (including some I didn’t know I have) and marks a real high point for the pastry program here.

On the back of two strong courses, Farkas feels no need to ply patrons with an extensive array of petit fours (the five of which, last time, were good but not inspiring). Instead, with total confidence, the pastry chef closes out the menu with a solitary bite: a “Squash and Miso Caramel Bon Bon” that (made using the same chocolate used in the dish prior and flavored with vanilla) ends the evening on a supremely enjoyable “pumpkin pie” note.

With that, the tasting menu reaches its conclusion: a tight two-and-a-half-hour experience from the arrival of the first dish to that of the last. This is the kind of pacing, in alignment with the meal’s number of courses and serving sizes, that is meant to empower (as Sandoval intends) ending the night elsewhere. Kumiko, certainly, is a good option, yet, whatever each customer chooses, there’s no question that the kitchen plays its part in optimizing one’s time here.

When the check arrives, it already comprises the full payment (including tax and 20% service charge) for the food and any preselected pairings—a wonderful way of avoiding sticker shock or any kind of possible negative emotion (vis-à-vis the peak-end rule) at this final stage.

Guests need only pay for any beverages that are ordered on-site—in my case, about $460 (after tax) for the two Champagnes. Tonight, the captain tries to assure me that everything has been taken care of. I press them to please charge me for the wine, upon which they bring me a bill for one bottle. I ask them again to please charge me for both, and I pay and tip and think all is well. However, in the days that follow, I notice that Oriole has voided the payment.

This is pretty unheard of in my experience (I only recall Alinea comping pairings—but not bottles of wine—during my visits there in late 2024 and early 2025), and never occurs at places like Kyōten or Smyth where I am a bonafide regular. Considering the glasses of wine that Rosenfeld already shared with the table during the meal (a tolerable yet already borderline too-generous gesture), the offer—and ultimate forced acceptance—of this charity struck me as overkill.

Alinea was clearly trying to buy favor (or mercy) from an ex-regular who is totally and pointedly immune to any of the group’s charms. Yet my relationship with Oriole is much more friendly and healthy.

The best explanation I can give is that the table’s criticism of the “Matsutake Custard” was pretty resounding (with several guests testifying to the “oversteeped tea” note). The feedback, in turn, may have been conveyed to the kitchen more harshly than intended by the captain (with whom my rapport is only starting to form). Our testimonial was also probably not buffered by any notable praise for the other fare. Thus, the team may have concluded we were not having a good time, and the comping of the wine might have represented an attempt to express remorse with regard to a recipe they maybe (upon tasting the broth) agreed was flawed.

Any other rationale eludes me, for I do not want to think that a restaurant of this caliber needs to buy goodwill. Plus, the real irony is that I actually consider this to be one of the best menus Oriole has put out in recent memory.

Indeed, in ranking the evening’s dishes:

I would place the “Capellini,” “Rocky Mountain Lamb Belly,” “A5 Miyazaki Wagyu Ribeye,” and “Golden Milk” in the highest category: superlative items that stand among the best things I will be served in any restaurant this year.

The “Lamb Tartare,” “Bluefin Tuna,” “Norwegian Fjord Trout,” “Rosemary Ice,” and “Squash and Miso Caramel Bon Bon” land in the next stratum: great recipes that achieved a truly memorable degree of pleasure. I would love to encounter any of these again.

Next come the “Carabineros Prawn,” “Hudson Valley Foie Gras,” “Badger Flame Beets,” and “Uni Infladita”—good—even very good—preparations I would always be happy to sample again (but that just failed to elicit an extra degree of emotion).

Finally, there’s the “Golden Kaluga Caviar” and “Matsutake Custard” merely good (or maybe just average) items that fell short when it came to texture and/or flavor. That said, the underlying ideas shaping these dishes were sound, and they could easily be improved with a little more fine-tuning.

Overall, this makes for a hit-rate of 87%—a clear improvement on the 85% figure (75% if I chose to count each component of each course) from September. More importantly, 27% of the dishes tonight landed in the “best of the year” category, and 60% (up from 40% last visit) were of that “would love to have again” caliber.

This is a massive performance (the kind I’ve only seen from two or three other restaurants in 2025) that totally affirms Oriole’s crowd-pleasing, decadent style of cookery. On any other night, I would expect the “Foie Gras” to land in a higher stratum (pushing the restaurant’s stats even higher). Plus, it’s not hard to see the “Prawn,” “Beets,” or “Uni” making that jump under the right circumstances.

Yes, only two courses can really be viewed as disappointments here: the “Caviar” (because the flavor of its starring element was obscured) and the “Matsutake Custard” (which would usually land in the third category if not for a technical lapse in the preparation of its broth). At this point, I’d probably like to see the latter recipe retired altogether. However, neither of the two really dragged down the menu dramatically. If the kitchen continues to play around with the caviar preparation, “perfection” (or something close to it) may very well be within reach.

That said, I think it is most heartening to see Oriole continue to execute some of its signatures (i.e., the “Capellini” and “Wagyu”) at such a high level while retiring others and unveiling new creations (e.g., the “Lamb Tartare,” “Bluefin Tuna,” “Trout,” and “Lamb Belly”) that deliver the same degree of pleasure.

Farkas’s work on the pastry side has been an instant revelation: one that (beyond any occasional missteps on the savory side) remedies a dessert sequence that I kind of felt formed the restaurant’s glaring flaw. Factor in the steadfast quality of the concept’s hospitality, the natural advantage provided by its interior design, and the supreme value (as well as some real creativity) shown by Rosenfeld on the beverage side, and I do not think it is wrong to say that Oriole is at its best right now.

Certainly, I still miss some of the faces and frills that defined the period immediately following the “2.0” renovation. However, in the interim, no other place has come close to challenging Oriole in the realm of pure satisfaction, and the team has grown ever more assured—all the more worldly in its techniques—in pursuing its goals.

While it is not controversial (let alone insightful) to say that this restaurant stands among Chicago’s best, I am happy to report that its quality—so ironclad for first-timers and fine dining newbies—shines for jaded gastronomes too.

This experience yielded some of the most excitement I’ve felt at Oriole in years, and I look forward to tasting what else the kitchen, if they remain committed to the same process, has in store.