As I said last time, writing these pieces about Kyōten—month after month—has become an increasingly complicated task: for this is not a restaurant that is characterized by sweeping new preparations, easily translated through a visual domain, with textures and flavors of such unique character that they stand apart from everything served before.

Writing about this (or really any) omakase with some regularity demands that one perceive the small changes that may distinguish the same fish served on different nights (not to mention a whole fleet of closely related species whose biological minutiae complicate any attempt to compare what are otherwise kindred bites). One must keep track of the rice’s quality—its consistency and seasoning—along with how well the chef’s signature dishes hold up. Over time, old recipes come back into season, and one must try to recall what they were all about. Entirely new creations might eventually appear, and one must judge them on their intention, execution, and what they might have replaced.

It all makes for a decidedly technical, granular approach to food writing. How many different ways can you really describe the texture of raw fish? How about trying to delineate the quality and caliber of umami for the umpteenth time? Of course, it’s incredibly rewarding trying to parse a cuisine that others cannot and will not tangle with to the same degree. That said, this task forces me to face the limits of my own sense memory. Save for taking notes (where, again, I must try to devise some kind of accurate scale to help direct my evaluations within and across visits), the whole operation ends up feeling instinctual and emotional rather than rational or (assuming it’s possible) scientific.

This is just the nature of appraising luxury experiences: one fleeting feeling contrasted to another, contextualized by a given diner’s lifestyle and expertise. Rather than name drop other omakases in other cities as a means of establishing my credentials, I’ve always felt satisfied in simply affirming that Kyōten offers value—especially repeat value—within Chicago. If anything, the concept only demands that would-be customers accept some of its quirks.

Here, in September, I can finally say that Kyōten has undergone a major change. It is not one that has all that much to do with the food—which, given chef Otto Phan’s unwavering place behind the counter, is largely protected against significant lapses in quality. Instead, it cuts straight to the core of the restaurant’s hospitality.

After six-and-a-half years of service, Jose Tejada has amicably left his place at Phan’s side: a role (spanning the duties of host, waiter, wine steward, and even cook) through which he had become almost synonymous with the concept. Undoubtedly, he played a tremendous part in shaping the guest experience—not just by mechanically facilitating the meal but by contributing to the mood of the space and establishing a warm, welcoming manner of interaction.

Given the kind of money Kyōten charges (a sum that corresponds with entire teams of captains and food runners at the city’s multi-Michelin-star spots), Tejada’s work was hugely consequential. Certainly, I think most diners came to understand that the price being paid went primarily toward sourcing the best ingredients possible, and the skeleton crew was a way of pushing the value proposition—vis-à-vis texture and flavor—to the furthest extreme. After all, establishments of this kind (often husband-and-wife run) are not uncommon in Japan.

Yet Tejada faced the pressure of solely upholding the restaurant’s standards in the face of the highest expectations (even downright skepticism given the lack of official honors). Even for the most charitable of patrons, there was never much room for error at this level of expenditure. Nevertheless, he formed a dependable partner through which Phan could put forth his own best efforts.

I cannot think of any other restaurant in Chicago where the stakes are so high—where a solitary figure (in a quasi-front of house, back of house role) is entrusted with actualizing the vision of a chef promising an ultimate expression of gastronomy. Phan, no doubt, has run the business by himself before (going all the way back to the original Kyōten sushi trailer). But maybe that kind of self-determination and confidence to go it alone makes the presence of a trusted collaborator even more special.

With no intention of changing how the restaurant functions (during a golden period that has seen Phan named “Chef of the Year” by his peers), Kyōten must forge onward—as it has done before—with a new multi-hyphenate hospitality figure.

I cannot think of a more meaningful development in the concept’s history without going back to the renovation—and accompanying rise in ticket price—itself. How does an experience like this change (or even survive) when faced with replacing one of its enduring personalities? The danger, at both a mechanical and emotional level, seems obvious.

Let us begin.

Armitage Avenue, by the time Kyōten’s 6:30 PM seating comes around, has reached a state of relative calm. It remains a major thoroughfare (especially at this point near its intersection with Milwaukee and Western). But the gridlock has softened, parking is easy (it has been ever since the spots in front of the restaurant changed to paid), and the flow of foot traffic (toward the residential building or nearby Redhot Ranch) lends the block a spark of energy.

As Ubers arrive and their passengers exit in different levels of dress, I like to try and guess where they’re going. A jacket or an expensive bag would seem to suggest Kyōten, but such diners also find their way Next Door (a concept whose mainstream appeal and difficulty in acquiring reservations may actually trump the mothership’s advantage when it comes to sheer luxury or price). Younger patrons in T-shirts would seem to signal the inverse, but they, too, often end up taking a seat in front of Phan—comfortably outfitted despite the extravagance of menu. Given the perpetual confusion surrounding which door to enter, parties that seem set for one restaurant may, after a few moments, be sent down the street in the other direction. By now, my instincts are pretty good, but I always like to see my expectations subverted.

I typically try to enter Kyōten after all the other guests have arrived. It saves me from the close contact that waiting in the vestibule entails, and it also gives everyone a chance to step through the sliding door, take that first glimpse of the counter, and greet the chef on their own terms. Plus, the meal doesn’t start until a little while after the stated time. It’s nice to slip into an experience that the other customers have already made their own—to observe (rather than steer) the evening.

Tonight, the audience is composed of couples in their 30s and 40s: a mix of repeat visitors and tourists. The enthusiasm on both sides of this equation (one anchored in a sense of familiarity, the other in a sense of discovery) sets the tone for the hospitality provided. Phan draws on the existing rapport and showcases his irreverent side from the start. With that established, all the explanations, stories, strong opinions, and good humor naturally flow. By commanding attention, the chef makes room for his new helper to shine: allowing him to focus on the mechanical duties of the meal while more slowly acclimating to its emotional timbre.

Though it’s only been a couple weeks, the assistant hits all the marks of food and wine service with confidence and precision. Greater self-expression—that is, making the evening memorable through the kinds of connections Tejada could form—will take more time. However, both his replacement’s conscientiousness and motivation to succeed are readily apparent. He meets the pace and responsibility that working on this two-man team demands (clearing plates, refilling glasses, and cycling through pairings without ever missing cues in the kitchen). And, so long as Phan makes that extra effort to engage meaningfully with his guests, the partnership feels capable of maintaining the same technical standard while slowly finding its own conversational, interactive dynamic.

When the omakase, at last, begins, it does so on a familiar note. Tomatoes have featured at Kyōten since the start of summer, and, as the season draws to a close, Phan favors what has proven to be his most winning interpretation of the produce. Here, the ingredient is sourced from Froggy Meadow Farm of Beloit, Wisconsin (a purveyor prominently featured at Feld).

The resulting “Sungold Tomatoes” are peeled, served in their own “broth,” and paired (as they were in August) with mozuku—an Okinawan seaweed. The chef invites diners to indulge in this “bowl of summer” much like they would a serving of ramen: crunching on the slimy strands then lapping up the liquid when all is said and done. Of course, the Sungolds remain the star, bursting cleanly on one’s palate and smacking of sweet, tangy concentration. The effect is deepened by the caressing, subtly umami seaweed and the fruity length of the broth, making for a fresh, satisfying start to the menu. Further, by introducing guests to a texture (the mozuku) that might feel a little strange, the dish even works to prepare them for what’s to come: items that may, in certain ways, challenge the palate yet always seek to reward it too. Overall, this recipe represents the very peak expression of tomato Kyōten has served this year.

A preparation of “Aka Ebi” (a variety of red prawn sourced from Hawaii) has also formed a longstanding presence over the past few meals. Originally, the crustacean featured opposite cherry tomatoes. However, the ingredient only hit its stride upon being treated even more simply: that is, served a few pieces at a time in a simple “ceviche-style” dressing of lemon juice and dashi.

On this occasion, the prawns are clearly smaller in size and a good deal less red than they have been in the past. Each piece, plump and juicy, leads with a puckering note of citrus that fades to reveal a lingering sweetness. I might like to see a little more influence from the dashi here. Nonetheless, this course feels clean and enticing: expanding on the same notes shown by the Sungolds while grounding them more firmly in the realm of seafood. As a sequence, the two dishes work well (even if I think this example of the latter recipe lands just a hair behind the one served last month).

The ”Octopus” that arrives next is a bonafide Kyōten classic—albeit one that has suffered a bit from inconsistency over the past handful of encounters. Speaking of his method for tenderizing the cephalopod, Phan jests that “you just have to massage it forever.” The chef typically nails that part of the equation, and it’s somewhere in the process of boiling and frying (in a karaage style) the wild-caught specimen that things can go wrong. Alternatively, the accompanying coating of avocado ponzu (a dressing that dates to the earliest versions of the recipe) can also falter.

Thankfully, the present example of this signature offering fulfills the ingredient’s full potential. It marries a slight chew on entry with rich, buttery flesh framed by traces of flaky (thoroughly moistened) breading. The resulting flavor avoids the kind of jarring acidity that has spoiled prior iterations. Instead, the octopus tastes full, soothing, and savory through the finish—delivering a kind of dense, pure expression (unbeholden to salt or char) one so rarely finds from this ingredient. In sum, this is a beautiful representation of one of Phan’s cherished dishes: an affirmation of why (so long as the cephalopod is executed faithfully) it has carved out a consistent place on the menu.

“Beltfish” last appeared back in July, when the chef introduced it as his “favorite” seafood for use in tempura. From time to time, he’ll have to opt for something like “Sheepshead” (as I encountered in August) to bridge the gap. Yet, tonight, beltfish is back—being battered and fried then paired with a condiment made from grated daikon soaked in ponzu.

Visually, the resulting pieces (generously sized and crowned by a wirework of crispy threads) are rather inviting, and, when they reach the palate, I think they just might represent the pinnacle of the restaurant’s work with this form. Texturally, the beltfish combines the expected brittle exterior with a lovely fluffiness and gentle flakiness throughout the inner flesh. The daikon, in turn, does well to invigorate the tempura with notes that are alternatingly spicy, tangy, and savory. However, the condiment remains understated enough that one never loses track of the mild, somewhat briny, fleetingly sweet essence of the starring fish. Yes, at the end of the day, this is not just a course that centers on frying. It is a study of an ingredient whose consistency and flavor—so well matched to the chosen technique—really shine. It ranks as one of the highlights of the evening.

The last course to appear before the start of the nigiri sequence is, for me, entirely new. “Cobia” (known as sugi in Japan) is simply roasted and paired with a ginger- and green onion-studded ponzu. The milky morsel of flesh that arrives—glistening—on the plate certainly looks appealing. However, the fish’s firm, meaty consistency is not matched by any accompanying butteriness. Instead, the flesh feels a little overcooked and, despite the sharpness of the accompanying condiment, any latent sweetness from the cobia is overshadowed by the resulting dryness. Ultimately, this makes for a clear disappointment (and probably the weakest bite of the night), but it is also one that can easily be remedied in the future.

Having grated his fresh wasabi, presented his seasoned rice, and equipped each guest with their requisite hand towel and pickled ginger, Phan kicks off the progression of sushi that—for all the highs and lows of the opening fare—anchors the quality of any Kyōten experience.

Tonight, for the first time since my meal in May, the chef opens with a series of not two but three expressions of wild-caught tuna from the Atlantic. The “Chū-toro” (a medium-fatty cut from the fish) leads things off, displaying a kind of ombré color that suggests this particular portion was taken from near the bloodline. Nonetheless, the flesh is characterized by a fine web of fat across its surface framed by alternating horizontal and vertical scoring.

On the palate, this piece feels remarkably soft: collapsing on itself in a rush of richness without melting altogether. Indeed, there’s just a trace of structure here—serving to delineate the fish—that is actually rather nice. The resulting flavor here is characterized by sharp acidity (from vinegar) on the attack and moderate pungency (from wasabi) through the middle. However, the fat outlasts the both of these sensations, steering the bite toward delectably sweet notes on the finish. In short, this is excellent.

The “Ōtoro” (signifying the fattiest and, typically, the most prized cut of tuna) arrives next and, naturally, promises to up the ante. Visually, the streaks of fat here are noticeably larger, amounting to something more like pockets (even a cap) at the most intensely marbled end. The knifework here, correspondingly, renders the surface in more of a tight, checkerboard pattern.

Texturally, this piece of the fish offers more of a fleeting, melty effect. That said, the less heavily streaked segment of the flesh still provides a semblance of structure, and I think it helps to have an extra means of contrasting such a torrent of fat. Flavor, on this occasion, is marked more by soy sauce than the vinegar. When this note joins with that wasabi on the finish, the effect is similarly sweet. But there’s also a deeply savory character, which charges this impossibly rich mouthful with an extra degree of satisfaction. Tonight (though it’s still a close call), I think the “Ōtoro” ranks as the best bite Phan serves.

“Akami” (referencing lean tuna) is a cut that hardly ever competes with the preceding pieces, yet Kyōten has always looked to turn this traditional hierarchy on its head. Boasting a deep, glowing red tone (with none of the same streaks of marbling) and some uneven (both horizontal and vertical) scoring, one wonders what this portion of the fish can do to compete.

When it reaches the tongue, the leaner flesh strikes with a firmness and meatiness that feels rewarding on the back of such comparably elusive mouthfeels. The accompanying flavor here is strongly marked by both soy sauce and vinegar too. Ultimately, the akami might not match the elegance of its fattier brethren, but it clearly outdoes them in terms of power. The result is an expression of tuna that (for those who love red wine or just dream of beef) revels in the ingredient’s carnal glory. This could easily rank as many a diner’s favorite item of the night (for me, it’s certainly in the running), and, more broadly, I appreciate the fact that Phan teaches his patrons to appreciate the distinct qualities shown by different sections of the fish rather than bowing to what might conventionally be prized. The chef’s tuna sequences, in this manner, go beyond mere expectation to actually engage a sense of discovery and self-definition of preferences.

Kyōten has long looked to “Buri” (a kind of wild mature yellowtail) to carry the torch after a series of bites that seems impossible to beat. The fish has always done an admirable job of holding diners’ attention, but it is not always available. Phan has replaced it in this crucial role with varying degrees of success. However, the “Tsumu-Buri”—a species called rainbow runner (as well as rainbow yellowtail, Spanish jack, and Hawaiian salmon when the mood strikes)—looks to tap into the same magic.

Phan characterizes the rainbow runner as “softer” and “more irony” than its family member, choosing to cure the ingredient using seaweed. The resulting piece displays a gently ruffled pattern across its surface and a darker tone (in part due to the application of soy sauce) to its flesh. Texturally, “Tsumu-Buri” is beautifully buttery and probably comes closest to matching the quality of actual “Buri.” That being said, the fish’s accompanying flavor is naturally a bit funkier, and I actually find myself wanting even more seasoning to help shift that character toward greater satisfaction. Still, this was an enjoyable bite that also introduced me to an entirely new member of the chef’s arsenal.

“Madai” (or Japanese red bream) was served following the tuna back in August, marking its first appearance of the year. The fish performed well in that role and, tonight, it harmonizes well with the rainbow runner too. This time, it is paired with a touch of lemon zest.

On the palate, the madai displays less firmness than it did last time. It is soft (though not quite as soft as the tsumu-buri), retaining a degree of structure that teases one’s teeth. The accompanying flavor, helped along by the citrus, is bright, fresh, and cleansing. At the same time, there’s enough soy sauce here to ensure the bite, which goes down easy, leaves behind some sense of weight and umami. In sum, I yet again enjoyed this fish. Being lighter, it breaks from what was served before without devolving into blandness.

When it comes to “Uni” (that is, sea urchin), Phan has been on a roll: delivering the kind of consistent pleasure that this prized ingredient, being so fickle, usually struggles to achieve. Indeed, the chef’s worst examples this year have still been good by any standard. His best have been transcendent, and tonight’s might just rank as the best of the best.

Kyōten has continued to get its hands on ensui (or preservative-free) uni, and the “dry-packed” version (i.e., without saltwater solution) is even better. The resulting lobes are layered atop a ball of rice wrapped in nori before receiving a final drizzle of soy sauce. The sea urchin, texturally, is oozing before it even reaches one’s mouth. Nonetheless, the perfect brittleness of the seaweed works to hold everything together: allowing for a marriage of warm grains and wet roe that caresses the tongue with a haunting sweetness. Yes, there might be a kiss of oceanic brine here—but no distracting iron. Ultimately, this is uni of a purity and intensity that I sometimes forget can even exist.

With so many of the omakase’s finest items having already appeared, the introduction of another sequence—one I’ve never witnessed before—helps provide structure and a sense of thematic resonance to this later stage of the meal.

“Sawara” (or Spanish mackerel) has not featured since March. Here, Phan is proud to serve a belly cut of the fish marked with ribbon-like scoring and a touch of ginger. On the palate, the piece displays a yielding, gently flaky consistency that turns creamy with further chewing. Despite this attractive foundation, the bite falls short when it comes to flavor. Yes, while I can faintly sense the ginger, its hallmark spice and tang seem to be missing. Beyond that, the sawara just tastes muted—no notable umami, no contrasting umami, just a textural thrill in need of some staying power.

“Sanma” (or pike mackerel) is said by the chef to be “symbolic of autumn” (and the season, he notes, gets earlier every year). Scored in a gridlike pattern, the fish—with its darkened flesh and remnants of skin—suggests the kind of pungent, greasy piece that can prove quite polarizing.

I can’t lie: this mackerel (technically a saury) is full-flavored, even fishy. It’s oily too—feeling, when it reaches the palate, as if its flesh is coated in mayonnaise. However, these extreme expressions of flavor and texture are packaged with a remarkable smoothness. And it’s rare to find a bite of such density, yet also a melting consistency, and such concentrated character to boot. Overall, this ranks as one of the surprise highlights of the night and one of the best examples of this kind of fish I have ever encountered at the restaurant.

Closing out this sequence, the “Seki-saba” (a premium variety of chub mackerel) takes a familiar form. I sometimes call it the “Mackerel Roll.” Other times it’s introduced as plain, old “Saba.” But Phan insists that you can identify seki-saba by the white tone to its flesh, and the prospect of enjoying this piece—stuffed with shiso-laced rice and folded (“like a taco”) around a strip of nori—with a different class of ingredient excites me.

Framed by the brittle crunch of the seaweed, the chub mackerel’s flesh is firm on entry but bursts with fat after a couple more chews. This makes for by far the most substantial serving of the night, and I think the textures are rendered in a way that one doesn’t mind chomping down on such a thick cross section of fish. That said, I must repeat my criticism of the “Sawara” here. Yes, while I sense some undertones of citrus from the rice, each bite is just too mild (bordering on bland). Relative to the seki-saba, there’s just too much dense flesh on display here to justify a soft touch. I’d really love to see how this roll eats with more savory power backing it.

Given the fact that Phan rarely features caviar on his menu, the return of the “Ikura” (wild Alaskan king salmon roe) is most welcome. Said to be in just the second week of their season, these orangish orbs are typically served before the nigiri. Tonight, situated atop rice with an accompanying splash of “strong” soy sauce (fortified with dashi and lemon zest), they make a case for their late placement.

On the palate, each pearl of roe provides a slick, caressing mouthfeel matched (when one provides the slightest bit of pressure) with a clean pop. The ikura’s accompanying flavor combines brine and sweetness with a surprising depth of umami drawn from the dressing. It’s that latter quality, buffered by the rice, that helps situate this dish at the end of the meal. Some may find the influence of this soy sauce to be a bit too heavy—and it’s certainly borderline for me—but this serving was a welcome surprise: one that changes the pace of the menu following so many pieces of fish.

Of course, there is one final piece of nigiri to contend with: the “Akamutsu” (or blackthroat seaperch) that the chef celebrates as the “most prized fish with fins and scales” that he serves. He also likens its character to being something “like a snapper” but “also like fatty tuna.”

The example Phan serves tonight meets the quality of what I tasted in August. That is to say, it ranks among the better preparations of this ingredient (its coveted status reflecting Japanese taste more than anything) I have encountered. Yes, on the palate, the akamutsu feels warm and rich with a gooey, mouthcoating length. Its corresponding flavor is fairly mild; however, unlike some other bites tonight, the vinegar and soy sauce provide enough support to win the day. Ultimately, I’m not sure this fish will ever form one of my own highlights. Nonetheless, I respect the part it plays at the end of the menu.

Closing out the savory portion of the omakase, the “Tuna Handroll” does not always live up to the kind of decadence that this fish, rendered in such a snackable form, would seem to promise. But here’s the thing: Phan always puts the best portions of his best sections into the nigiri (which are already oversized relative to the norm).

Tonight, the chef draws on scraps of fattier tuna for his handroll, and the effect is correspondingly explosive. Yes, on this occasion, the brittle crunch of the seaweed (always impeccably rendered) houses melty flesh matched by a stronger application of wasabi. Though one bite is blemished by a bit of sinew, the overall flavor here is stronger and more satisfying than what I typically find. In short, this is a real treat.

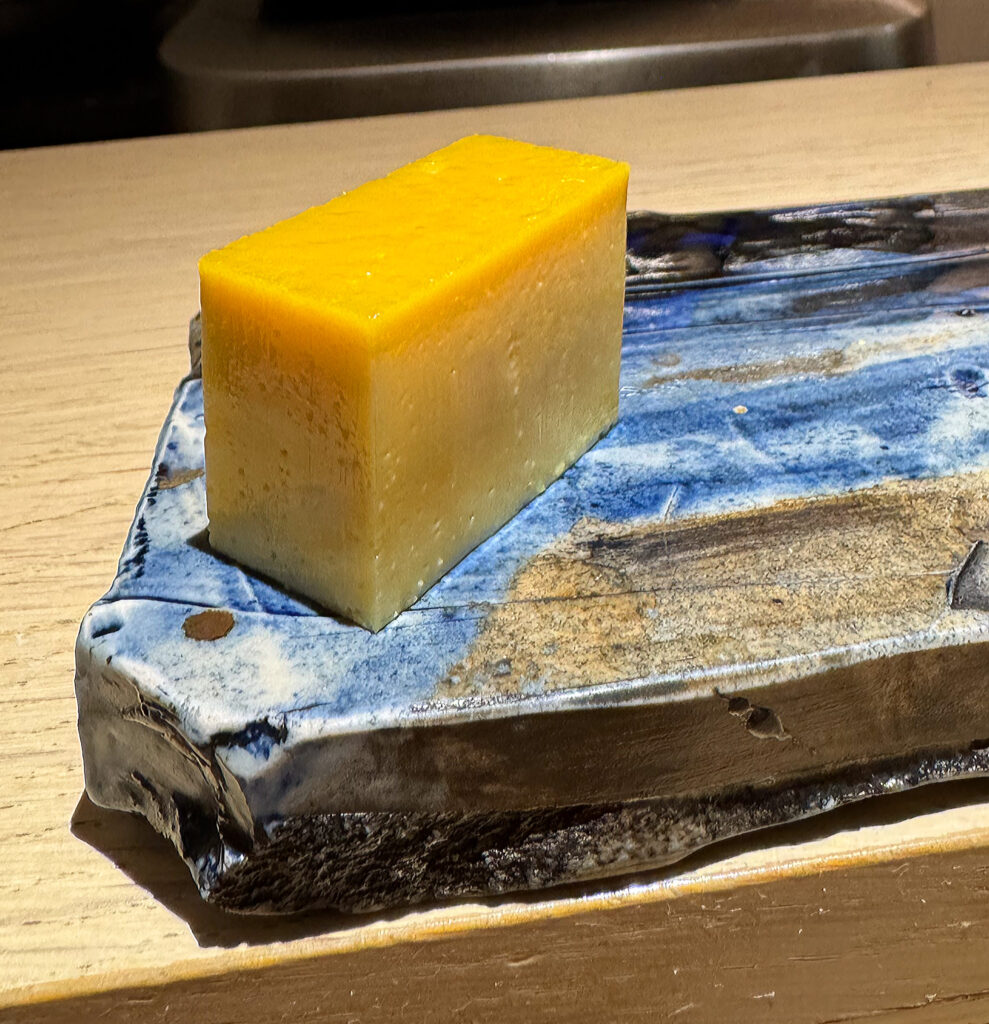

Kyōten’s signature “Tamago,” rendered as a corn- and maple-infused custard, can fall victim to a certain amount of variation. That being: the bite is sometimes served too cold (which serves to mute its full expression of flavor).

Tonight, the eggy delight is served just right. It holds its structure for just a second on one’s tongue before collapsing and forming a slick, creamy coating. The resulting sensation—rich like egg, tinged with caramelized sugar, but brimming with the fresh sweetness of the Midwest’s favorite crop—still makes for one of the best examples of the form I have ever encountered. Few dishes so effectively communicate how Phan has tailored tradition to the place and the tastes he has chosen to call his own.

The evening’s central dessert takes the form of a “Coconut-Basil Sorbet” that the chef has been playing with (along with various macerated or stewed fruits) for the past few months. Tonight, he pairs a scoop—perfectly judged in its sweetness with transfixing nutty, herbaceous undertones—with a few pieces of watermelon.

As appealing as this idea (one of the simplest compositions I can remember the sorbet featuring in) is, the watermelon is bland. It detracts from—rather than amplifying—the notes of coconut and basil. Certainly, it does not rob the preparation of all its pleasure. However, it seems clear that this was just a bad fruit, and, thus, the intended flavor combination falls flat.

After expressing gratitude for his audience’s patronage, Phan retreats to the lobby, where each party will be granted a chance to converse, pose for pictures, or simply express their own thanks before departing. The check arrives around the same time, with gratuity neither being solicited nor accepted.

By now, three hours have passed—intimately, indulgently—since I walked through the door. A different Kyōten made itself known tonight, but isn’t that always the case? The concept embraces change, and the guests are bound to feel it. Still, the effect remains the same: sushi of a singular style, served with an incomparable attitude, at a counter (no matter how regal it looks today) imbued with the chef’s earnest devotion to craft.

This is the spirit that has survived—that will survive—no matter how the conditions, the actors, and the ingredients are fated to fluctuate.

Yes, for all the worry about how the restaurant’s two-man team would fare following a shake up, there’s little that a chef-proprietor, when engaged in their work and driven to succeed, cannot overcome. For someone like Phan who built his business on doing things by himself, just having an extra set of hands and feet to direct must feel like the greatest luxury: a tool he can deploy, as needed, to help prioritize his own most important work.

However, to say this is to detract from the chef’s own growth as a leader: one who has collaborated with several waves of staff at his flagship then, subsequently, built a team that can stand on its own—delivering work worthy of the Kyōten name—Next Door. To say it is also to discount the fact that Phan has honed his ability to sense and shape talent. By every indication, his latest hire—conscientious, observant, oh-so-eager to jump in on either side of the operation—has the character to succeed. The technical side, after all, can easily be taught.

This is not to say that what Tejada brought to the concept, on an emotional level, can easily be transmitted. It would certainly be a mistake to try and contrive it. Yet the conditions seem ripe for the development of that same kind of ownership—for the emergence of a new voice whose personality might just infuse the experience with its own kind of magic. Connection cannot be forced. All one can do is trust the process. However, tonight, it seemed like this process was well underway.

In ranking the evening’s dishes:

I would place the “Chū-toro,” “Ōtoro,” “Akami,” and “Uni” in the highest category: superlative items that stand among the best things I will be served in any restaurant this year.

Next come the “Sungold Tomatoes,” “Aka Ebi,” “Octopus,” “Beltfish,” “Tsumu-buri,” “Madai,” “Sanma,” “Ikura,” “Akamutsu,” “Tuna Handroll,” “Tamago,” and “Coconut-Basil Sorbet”— very good—even great—preparations I would always be happy to sample again (but that just failed to elicit an extra degree of emotion). Of these, the “Beltfish,” “Sanma,” and “Ikura” came closest to reaching that higher level.

Finally, there’s the “Cobia,” “Sawara,” and “Seki-saba,”—merely good (maybe just average) items that fell short when it came to texture or flavor. None of these bites faltered in more than one dimension, so there was still pleasure to be had (and, indeed, they could all easily be fixed with a little more tweaking).

Overall, this makes for a hit-rate of 84% (and, really, the overcooked “Cobia” was the only clear disappointment of the night). If I were to say that the “Sawara” and “Seki-saba” are ultimately a matter of taste, the number could climb as high as 95%. Just the same, I’m also excusing the blandness of the watermelon I encountered because the “Coconut-Basil Sorbet,” itself, was so good.

The real story here is that, while the “Ōtoro” did not reach the “once-in-a-lifetime” status I am always chasing, all three tunas (and the sea urchin to boot) were of that superlative, best-of-the-year caliber. With these headliners as a foundation (the kind that would please almost anyone choosing to shell out big bucks for omakase), a full 80% of the rest of the menu met that “good,” “great,” “would like to taste again” (if not slightly higher) standard.

What do a few misses—or a couple things that just don’t make a big impression—matter when the bulk of this nearly twenty-course meal, spanning such a diversity of techniques and textures, surprises and delights its guests (even veterans like me)?

In the final analysis, that question lies at the heart of Kyōten’s value proposition: one that persists through the changes of the season (and, from time to time, changes in the very people that actually make the experience happen) but that always finds its center in a broad array of bites that stand among Chicago’s best.