When I dined at Smyth back in October following an unusually long absence, it was easy to see why this restaurant—despite the affirmation provided by that third Michelin star—continues to make such an uneven impression. That night, some 33% of the dishes I tried landed in that “would love to have again” category, but only 76% were judged as successful overall. Put another way: recipes that hit did so in a big (and totally distinctive) way. However, a notable portion floundered, and the majority landed somewhere in between.

Despite countless meals here, I’ve tried to never be an apologist for the team’s work. Indeed, I think some of the most thoughtful (as well as pointed) criticism that Smyth receives actually comes from loyal diners. Some customers still dearly miss the restaurant’s pre-pandemic era—when creativity, approachability, and decadence (tempered by the same charming hospitality that survives today) seemed to go hand in hand. Certainly, those were the menus (with their fish ribs, licorice eggs, and the original run of beef-fat brioche doughnuts) that made me fall in love with the place too. Yet, maybe it’s exactly because I was visiting so often that I welcomed what would come next.

By that point, I had already eaten several lifetimes’ worth of tasting menus (spanning all kinds of concepts), and my preferences aligned more with dynamism and the desire to encounter something new rather than simply tasting caviar or truffle or wagyu for the umpteenth time in any kind of conventionally pleasing construction.

Smyth has always evolved—hence why it rewarded repeat patronage. Nonetheless, after the pandemic (and with the collaboration of a new, outside chef), the restaurant completely transformed itself. It adopted a new language, rooted in an obsession with strange ingredients (e.g., seaweeds, nut oils), and said goodbye to a whole fleet of signature preparations without ever really replacing them. The kitchen closed the door on a beloved chapter that many Chicagoans never had a chance to try and one which those who did may still pine for.

In pursuing a cuisine that could stand alongside the work of the world’s most renowned gastronomic temples, Smyth necessarily rejected anything easy. The team transcended what had made them a cult favorite within Chicago and shaped a new way cooking that had real global import. Of course, we should not forget that the pandemic ruptured the central, orienting relationship the chefs had with The Farm and all its purpose-grown produce. But the result, I think, skewed the appreciation of the restaurant’s food more toward an experienced, cosmopolitan crowd than the native audience that had so enjoyed it during those opening years.

I do not mean to say that Chicagoans lack the intelligence or worldliness required to appreciate what Smyth is doing. Plenty of locals go in—completely cold—and have an incredible time. However, in this democratized era of fine dining, an ever-greater population now splurges on meals of this caliber. Buoyed by the lack of pretension that has long distinguished this city, they enter rarefied dining rooms with high expectations regarding the kind of luxury, wanton deliciousness, and performative flourish that waits in store.

Smyth meets them with quiet confidence, with zero ostentation, with weird natural wines, and wish dish after dish that—beyond not even photographing well—practically demands a dictionary to parse. A given diner (on the hook for more than $500 per person) may violently chafe against this encounter or totally surrender to it: letting their palate approach the cuisine on its own terms and maybe, just maybe, rethinking what these ingredients (or the tasting menu format altogether) have to say.

Alternatively, I know plenty of experienced diners—people whose palates I respect and whose admiration for John and Karen Shields is clear—who simply find that the current set of textures and flavors and signature recipes has run its course.

In short, like all great art, Smyth is not afraid to alienate some part of its audience by maintaining such a firm commitment to a profound, personal, and at times even inscrutable vision. It’s just not in the team’s nature to pull their punches for the sake of broadening appeal—to slow the process, so self-driven, that has brought them to the pinnacle of their craft. More importantly, it’s a process that continues to connect—and connect deeply—with a certain demographic of patrons each night: the singular voice finding harmony, time and again, with the rare listener who really understands.

But Smyth—driven by larger circumstances—has taken a new direction before, and it seems poised to do so again. The pandemic cleared the way for Luke Feltz to make his influence felt, producing the paradigm shift I just described (and that won the restaurant its highest honors). Over the past years, Brian Barker has continued Feltz’s work: maintaining that three-star standard throughout the transition and pushing the same processes to newer, greater heights. Now, Barker leaves on a high note after more than seven years of service, and Shields has cast a wide net for the “national or international chef” who might step into the role.

The prospect of collaborating with an outside force—unshaped by the restaurant’s current practices, in possession of their own vision, willing to challenge and transmute the singular style that has earned Smyth such esteem—strikes me as a paradigm shift of all the same consequence as Feltz’s own arrival. Though, in truth, it remains to be seen just who will fill the role of head chef and how their influence will be felt.

Nonetheless, this imminent change (with Barker’s departure being planned for late March) can only be judged in relation to the cooking being done today—what might, in retrospect, be termed the last expression of its own distinct and bygone era.

For this reason, I think it is well worth exploring the end of a chapter in Smyth’s culinary history that has, love it or hate it, defined Chicago gastronomy during the 2020s.

Let us begin.

Tonight’s meal begins in a familiar fashion: a pour of “Amazake” made by executive sous chef Matt Orlowski (who, once the new head chef arrives, will form a living link to all the kitchen’s work with preservation and fermentation in the recent past).

The present brew centers on quince that has been cooked overnight with two kinds of rice kōji, causing an enzymatic reaction (the transformation of carbohydrates into sugars) whose resulting liquid is then strained out. It is combined with a quince and honey kombucha, mead, junmai sake, and roasted buckwheat to complete the beverage (containing only a negligible degree of alcohol). On the palate, the amazake combines a subtle tingle of acidity with comforting sweetness, milky weight, and a beautiful honeyed note that carries through the finish. While this example does not rank among the very best Orlowski has made (which can taste positively electric), it still makes for a pleasant start to the evening.

The first proper serving of food to arrive tonight—titled “Dungeness Crab & Kakai Squash”—showcases one of Smyth’s most enduring forms: the tart. Here, a gossamer shell (made from the latter gourd) is stacked high with shreds of the shellfish, kombu chips, squash seeds, Red Ogo seaweed, and finger lime that have all been lightly dressed in brown butter.

I know to expect total delicacy when I take a bite, for the tart (however structurally sound and flawlessly crisp) leaves behind almost no trace. Instead, texturally, I am met by a generous mouthful of crab punctuated by the odd crunch or pop from one of those other elements. With help from the brown butter, the overall effect here is moist and pleasing. Likewise, the flavor—marrying rich seafood depth with notes of citrus, brine, nuttiness, and closing sweet—is just sublime. In my experience, these tarts don’t always hit, yet this one stands as a perfect encapsulation of the restaurant’s culinary style.

A subsequent serving of ”Toasted Corn & Black Truffle” (the latest in a long line of “wafer” preparations that have migrated from the sweet to the savory side of the menu) absolutely stunned me when I encountered it in October. On this occasion, it largely takes the same form (that is, sandwiching the starring ingredient between corn tuiles) while playing with the filling a bit: substituting the previous iteration’s fava bean miso for quail liver and its mix of white and black truffles for Périgords alone.

Upon reaching my tongue, the bite continues to impress me with its seamless, crisp-and-creamy mouthfeel. Yes, the structure here is so dainty, yet the resulting package is so polished that it’s hard not to think of something precisely fabricated (like a candy bar). Of course, the accompanying flavor here is totally singular: spanning notes of earthy, roasted corn, concentrated umami, musky depth, and the enlivening tropical tones of fig leaf. For my taste, the white truffle version was more pristinely sweet and haunting. It will always be hard for even the cherished Périgords to compete. Nonetheless, I think the black truffles are well matched to the liver and that this recipe, overall, holds up well (despite not exactly reaching the same heights) with these changes.

The opening sequence of bites concludes with a “Smoked Eel & Sesame Donut” that replaces the previous menu’s “Trout Belly Donut” (but, in truth, follows in a long line of savory preparations pairing this form with increasingly inventive ingredients). More familiarly, the fried pastry comes stuffed with a foie gras mousse—a creamy, sweet-savory core that plays well off the crisp exterior and fluffy crumb while helping to anchor the bolder components. Here, those toppings include the titular eel (sourced, as always, from American Unagi), a pig ear terrine, and an apple tuile alongside accompanying touches of sesame, ginger, and chili oil.

Such a varied combination seems hard to manage (indeed, even the prospect of popping the whole thing in your mouth feels a little scary), yet it works in large part due to how soft and yielding both the starring fish and the terrine are opposite the donut. Yes, the word “seamless” comes to mind once more, and I think it is the fundamental elegance of the construction that makes its strange constituents more approachable for a broad audience. However, the impression they leave is one of fairly straightforward richness and sweetness (with much of the bolder heat or pungency or nuttiness being kept to the background). Ultimately, while I do admire the cohesiveness of this recipe, I’m not sure it hits the peak of pleasure that this pastry form promises. Put another way: the donut is technically impressive more than it is memorably decadent.

At this point in the meal, I am met by something entirely new: a presentation of whole rainbow trout, along with its egg sac, over ice. This show-and-tell represents the introduction of a fish (sustainably sourced from Virginia’s Smoke in Chimneys hatchery) that will feature across the menu. Past meals have seen the kitchen dive right into a two-part course centered on this ingredient; however, the present conceit allows the team to focus more on storytelling and a slower, more intentional introduction of the seafood’s different sections.

The ”Trout Tail Tartare,” as the name suggests, utilizes flesh found at the rear of the fish that, in a fine dining context, is typically less prized than a neat fillet. Still, this part of the fish yields perfectly enjoyable meat that, here (in raw form), is layered with tomato water gelée, fresh horseradish, wasabi oil, and citrus- and miso-cured roe to form a composed, parfait-like preparation.

True to type, the dish impresses me with its creamy, homogenous texture—one in which the textures of the trout’s buttery flesh and crowning eggs are nearly imperceptible. The accompanying flavor is equally soft-spoken: leading with acid and turning toward subtle, fruity notes of tomato without really delivering the degree of miso-tinged umami or horseradish/wasabi-charged pungency that would really have an impact. This is likely a conscious stylistic choice (it being so early in the meal and all). Nonetheless, it means that this recipe represents more of a teaser and a visual, conceptual thrill than anything memorable.

New to the menu (though not totally beyond Smyth’s usual bag of tricks) is a “Maine Uni Parfait.” However, given that the preceding dish was also likened to a parfait, I much prefer the “uni cloud” title favored by my server. The core element is a frozen meringue (referencing the original French dessert rather than the American offshoot) made from sea urchin that is still alive when it arrives at the restaurant. Cooks extricate the “roe” (technically gonads) from the creature’s spiny shell and use it to flavor a puffed, honeycomb-like structure that comes drizzled with sea lettuce sauce. Beneath the cloud, one finds an oyster emulsion dressed with Szechuan peppercorn and bergamot, building a layered effect that circles back to the alternate meaning of that term “parfait.”

On the palate, the preparation leads with a refined, ephemeral texture that, as the impossibly airy cloud melts, highlights the comparable weight and richness of the accompanying emulsion. The flavor of uni here is resoundingly pure (i.e., free any jarring irony character) and surprisingly persistent: stopping just short of sweetness but imparting a pleasing oceanic note that is reminiscent of crab or lobster. Opposite the sea urchin, one finds a range of tangy, floral, numbing, briny, and vegetal tones that—though they sound jarring—are beautifully softened by the cloud’s frozen temperature. This allows those accompanying elements to build background complexity without obscuring the fundamental flavor of the uni. Rather, these supporting ingredients, via the contrast they provide, actually tease out a degree of depth one rarely finds in sea urchin. Overall, this makes for a course that is both highly inventive and convincingly delicious.

Arriving next, the “Maine Lobster & Uni” looks to double the fun. I actually encountered this recipe back in October, when (presented in a shallow bowl) it seemed to reference some of the caviar and almond constructions served during meals past. Tonight, the preparation is served in the sea urchin’s actual shell (a nice advantage of sourcing the ingredient live), combining familiar accompaniments—like smoked lobster meat, lobster custard, squash purée, Virginia peanut milk, and walnut oil—with a new addition of papaya.

Texturally, whereas the “Maine Uni Parfait” was all about fleeting enjoyment, the present dish (at least by Smyth standards) lets the diner really sink their teeth into the starring ingredients. One revels in the plumpness of the lobster and savors the triple dose of creaminess as sea urchin (brined to a slightly firmer finish), custard, and peanut milk combine. The flavor here, too, is more unabashedly sweet than that found in the preceding course: spanning oceanic (from the seafood), earthy (from the squash), and tropical (from the papaya) expressions that, nonetheless, are countered by the concentrated nuttiness of the walnut oil. The end result is not exactly boisterous. Nonetheless, both the lobster and uni are beautifully showcased: unwinding in a long, meditative manner that resists comparison.

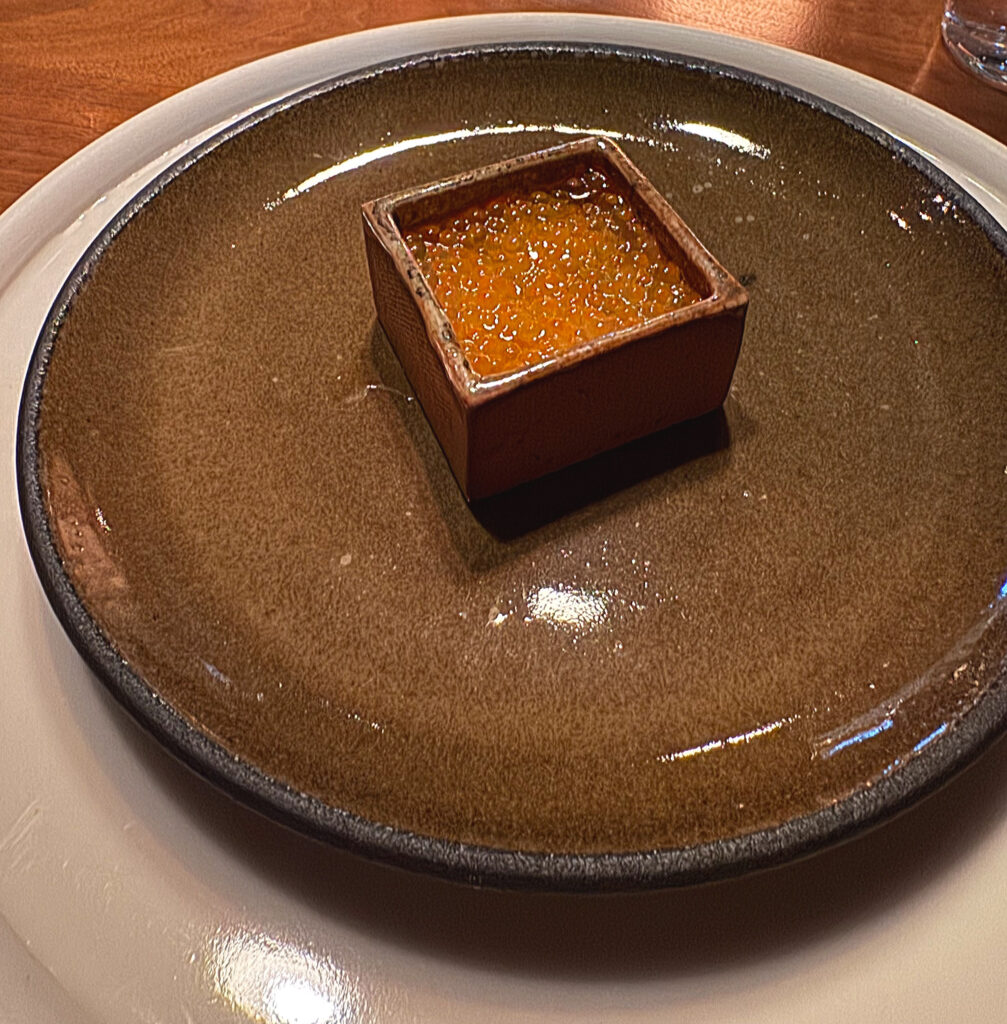

“Caviar & Pumpkin Seed” represents one of the clearest evolutions from the Feltz era (when signatures like “Hot & Cold Kaluga Caviar” and “Caviar & Almond” were standard-bearers of the broader house style). The present recipe hasn’t totally broken from the palette of textures and flavors that have come to distinguish the restaurant. However, it has gently reduced the influence of nut oils while allowing other totems (i.e., black walnut, egg yolk, seaweed) to take the lead in combination with seasonal produce. To be honest, I cannot say that this dish has totally convinced me up until this point. Yet, tonight, the components come together beautifully.

The plate centers on a sizable scoop of Kaluga caviar sourced from N25 (a German company whose expertise is extolled during the accompanying spiel). This roe comes surrounded by four blade kelp and sea lettuce ravioli—two stuffed with pumpkin seed butter, two with pumpkin praline—with a dab of black walnut-cured egg yolk “fudge” set to one side and a tableside pour of kabocha squash juice serving to complete the presentation.

On the palate, the Kaluga delivers a delicate mouthfeel with individual orbs (each wholly perceptible) that rupture with total smoothness. Though the ravioli are comparably chewy, the sensation is easily managed. More importantly, their hidden fillings—alongside that egg yolk fudge—coat the tongue with a richness and weight that further enhances one’s perception of the caviar. Flavor here begins with conventional notes of nuttiness and brine, but they build toward an earthy sweetness and a beautiful, caramelized finish. Ultimately, it is the kabocha juice (substituting for a squash sabayon and drizzle of parsley oil utilized in October) that really makes the preparation sing: enlivening (and balancing) the assembled ingredients with its fresh acidity and echo of sugar. The sum effect, true to the kitchen’s aims, is totally unique while not at all sacrificing decadence. Yes, based on this experience, I think the “Caviar & Pumpkin Seed” is finally worthy of replacing the cherished recipes that came before it.

A preparation of “Avocado & Turnip” also represents something of a reimagination for one of the restaurant’s post-pandemic signatures. Honestly, the recipe really didn’t work for me when I first encountered it last year. However, I could sense what it was aiming at, and, having benefitted from a bit of tweaking, the dish actually lives up to its potential on this occasion.

Sourced from San Gabriel, the starring fruit comes blanketed with grated horseradish and sits atop a medley of Dungeness crab, geoduck, Marcona almond, and green almond all coated in a turnip cream. The result, texturally, is built on the rich, buttery mouthfeel of the avocado, and I am impressed at just how seamlessly both shellfish—especially the later mollusk (so known for its crunch)—are incorporated. Indeed, while the seafood adds a sense of weight and meatiness to mix, this course is really driven the horseradish. Its sharpness cuts through the denser, milder flavor of the avocado and teases out the sweetness that the turnip, crab, and geoduck all have lurking within. For my palate, the almond elements are too subtle, but I still found myself enjoying this item—even after tasting many years’ worth of variants.

The “Rainbow Trout & Pineapple,” while technically a carryover from October, benefits from the show-and-tell that occurred when the “Trout Tail Tartare” was presented. Also, more generally, the fish is granted a greater opportunity to shine without the kind of distraction that a sidecar (affixed to this course) can sometimes provide. Last time, this dish was undone by a jolt of bitterness injected by some nasturtium flowers. Yet, tonight, that element has been excised, and the recipe (like so many others on the present menu) finally has a chance to really strut its stuff.

At the center of the bowl, one finds a three- or four-bite portion of trout fillet that has been glazed with Maine uni and topped with a shard of crispy, caramelized skin. The fish swims in a nage made from cultured cream and whose depths obscure a piece of seared roe, a dab of rhubarb butter, a pineapple-habanada dressing, and some fermented chili condiment. On the palate, the trout displays the kind of supreme butteriness—offset by the clean crunch of its skin and the surprisingly firm (then liquid) segment of the egg sac—the kitchen has always done well to achieve. Flavor, in turn, tends to be where these preparations struggle. Nonetheless, the marriage of tang, sweetness, floral depth, and fleeting heat here is perfectly judged. I even sense a touch of bitterness, but it’s skillfully incorporated. Yes, the combination of nage and dressing and all the other condiments is so delicious that I find myself tilting the bowl to lap up every drop. In short, I cannot remember ever tasting a better iteration of rainbow trout (or maybe even cooked fish more broadly) at Smyth.

Moving into still more substantial fare, I come to a course comprised of a “Black Walnut Cured Quail Egg” alongside a presentation of “Quail & Malted Milk Bread.” The first and the last elements named here are pretty familiar by now. However, the bird itself has really gone in a new direction—diverging from the white truffle, sprouted grains, boudin noir set I saw back in October. Instead, the breast of the quail (sourced from Vermont) is stuffed with duck and squab and laced with Périgord truffle. It then comes served with an additional portion of shaved truffle, a polenta made from fermented amaranth, some grain porridge, and a sauce made from quail stock.

Texturally, the meat from the bird’s breast is remarkably tender, and its essential savory flavor is wonderfully deepened with the supporting notes of the duck, squab, and truffle. Nonetheless, while I have high hopes for the amaranth polenta, what I find at the center of the plate veers toward tangy, fruity, and surprisingly sweet tones that seem to counter (rather than harmonize or subtly contrast) the satisfying umami of the quail. For whatever reason, these two opposing forces actually resolve on the finish. Still, I am left feeling that the core components fight each other on the midpalate: the kind of miscue that saps enjoyment.

Engaging with the course’s other elements, I find that the “Black Walnut Cured Quail Egg” is more or less how I remember it from last time. The cured and smoked bite gushes nicely when it meets one’s teeth, yet the accompanying flavors of preserved truffle and caramelized shallot consommé strike the same savory—but too-sweet—note I struggled with on the main plate. Ultimately, this is not an offensive item, yet it’s one that falls flat for me given the wider context.

Given my struggles with sweetness, you’d also think the “Malted Milk Bread” would be a loser tonight. Ironically, the present version (featuring a pecan-toffee glaze) is actually one of the strongest I can remember tasting: balancing a sticky, crusty exterior with a fluffy crumb and an only mildly sweet flavor that is nicely tempered by supporting nuttiness and caramelization. For what is perhaps the first time, I actually wouldn’t mind another helping.

Whereas lamb has frequently been served before the quail (leaving the bird to anchor the savory side of the menu), tonight’s meal closes on a preparation of “Venison Royale” that pushes richness and meatiness to a final crescendo. Given my hang-ups regarding the preceding course, this additional serving represents a real lifeline. This dish centers on deer (sustainably sourced from over-populated herds by Broken Arrow Ranch) that has been dry-aged for a month.

The loin is roasted and paired with a piece of its poached heart, then the two are situated atop a sliced of boudin noir. Roasted beets, some smoked tomato, and a sauce made from foie gras complete the presentation, which marries the venison’s subtle chew with the smooth, encompassing blood sausage. Upon this foundation, a robust savory flavor—powerful, yes, but not stereotypically “gamey”—builds: one whose sweet, earthy, and even sharp (almost irony) accents work to round out the intensity. Yes, the length on display here (a dream match for any aged Burgundy or Rhône) is just immense, and, ultimately, I think this recipe represents one of the stronger entrées I’ve seen Smyth serve over the past couple years. That said, while the composition smartly avoids any weirder accompaniments that might distract from the meat, the sum effect also falls short of being truly memorable.

Arriving next, the “Venison Bouillon” follows in a long line of broths and teas that, playing off the main course, look to elegantly transition toward the sweeter side of the menu. Here, the starring consommé arrives chock full of sliced maitakes and floating enoki caps. Some yuzu zest and a drizzle of blackcurrant wood oil served as the complicating elements, charging the concentration of earthy (though not particularly umami or salty) notes with a clean, woodsy, and intriguingly fruity (though only faintly sweet) flavor that freshens one’s tongue even as it echoes the character of the “Royale.” Overall, I’d term this brew intriguing more than I would decidedly good, yet I appreciate its role in the meal’s larger flow.

The ”Rice Pudding & White Truffle” shifts us into the realm of pastry chef Jenna Pegg (whose long tenure at Smyth—now pushing five years—will form a clear source of strength for any new head chef). In fact, I think the team’s work on the dessert side has actually become one of the restaurant’s biggest guarantors of pleasure, combining creativity and sheer deliciousness in a manner the savory fare can sometimes struggle with.

The present dish—made from Koshihikari rice (cooked in a donabe) in combination with a buttermilk whey nage, foie gras ganache, a wine reduction gel, and flavors of coffee and cardamom—is a great example. It marries smooth, soothing textures (delicate enough so that those slices of white truffle remain perceptible) with a kaleidoscope of toasty, salty, nutty, earthy, and deeply sweet notes that—cohering effortlessly—are just sublime. This fails to even capture the supporting acidity, fatty richness, and hints of florality the work in the background. The final expression here is maddening in its complexity but so convincing in its pleasure. Yes, this recipe has to rank as one of the finest (of any type) in Smyth’s history, and it actually helps to rationalize the flavors found in the “Venison Bouillon” too.

The “Cadbury™ Quail Egg” that comes next is nothing new, but, filled with citrus blossom curd and an egg caramel, the bite (painted and staged in such a naturalistic manner to boot) remains one of the kitchen’s most playful. On the palate, the brittle shell gives way to creamy—then sticky—sensation with an accompanying flavor that is more reminiscent of SweeTarts than any chocolate. Still, the egg makes for a fun diversion that helps to counter the richer items served on either side of it.

A serving of “Yogurt Mousse & Quail” also featured in October, when it made a good impression without totally blowing me away. Tonight, it pretty much maintains that standard: combining a barley-buckwheat mousse, quail stock gelée, butterscotch caramel, roasted buckwheat, and a sprouted grain-wheatgrass milk. Upon cracking through the cacao-studded black malt tuile, one is met by a resounding creaminess whose meaty, tangy, and herbaceous notes lend depth to an otherwise approachable expression of earthy dark chocolate and milky sugar. In a way, this dish almost feels a bit like showing off (that is, how far can the kitchen push the flavors of grains and game they typically favor?). However, it’s hard to argue with the balance achieved here.

Arriving next, the “Pomelo Gold & Meringue” reminds me a bit of the “Satsuma Mandarin & Ginger” that so impressed me last time. Indeed, both dishes center on a half-portion of citrus that comes a little dressed up. The captain actually identifies the present fruit as a tangelo (that is, a cross between a mandarin/tangerine and a pomelo/grapefruit). However, it comes stuffed with actual pomelo—as well as guava, Buddha’s hand, candied habanada, and a jasmine-infused, meringue-like sauce. This exotic mélange spans crisp, creamy, juicy textures and a whole range of tart, bitter, floral flavors. Yet, somehow, the preparation ends on a supremely fresh, invigorating sweetness that plants its balance firmly on the side of decadence. Overall, I do think this course could come earlier in the dessert sequence, but it still ranks as one of the meal’s highlights.

When I lay eyes on the ”Birch Ice Cream,” I am immediately transported to a short period—many years ago—when Smyth last served this kind of frozen novelty. Buried in ice and affixed to a slender branch, the bar combines a roasted birch base with a birch caramel center and a glaze of housemade white chocolate. Texturally, the ice cream is wonderfully smooth and tempered once one gets past its crisp exterior. Further, while I expect the treat to be marked with uplifting notes of mint (and, indeed, they are there in the background), the dominant flavor combines milky sweetness with just the kind of deep, dark toffee tones one desires at this closing stage of the menu. In short, this is a beautiful, nostalgic offering that stands among the best items of the night.

Last but not least, one finds the same trio of petit fours served back in October.

Of these, the “Pumpkin Pie” (a tart filled with pumpkin seed sable and spiced milk foam) is a tad chewy but true to type: delivering a deep, roasted sweetness that also calls the menu’s excellent caviar course to mind.

The “Preserved Kombu Tart” retains the reservoir of pistachio praline that stunned me when I last tasted it. And, placed opposite the concentrated umami of that starring seaweed, these nutty notes achieve a peak expression (all in a pleasantly crumbly, sticky package) that continues to rank as possibly the best petit four I have ever encountered.

Finally, there’s the “Bittersweet Chocolate & Maitake”—a wafer base lined with chanterelle ganache and a crowning layer made from the titular (in this case candied) mushroom. Here, I think the kitchen intends to leave guests with a flavor that is somewhat challenging. To that point, the intense earthiness does indeed harmonize well with the darker character of the cocoa. However, it’s hard to end the night with a combination that is somewhat strange when the kombu tart—right there—can be relied upon to make such a nakedly pleasurable impression.

The same goes for the parting “Seaweed Caramels,” which (despite forming a longstanding offering) always seem to stick to their wrapper and only serve to reinforce a flavor profile that some might find more intriguing than enjoyable.

In ranking the evening’s dishes:

I would place the ”Rice Pudding & White Truffle,” ”Birch Ice Cream,” and “Preserved Kombu Tart” in the highest category: superlative items that stand among the best things I will be served in any restaurant this year.

The “Dungeness Crab & Kakai Squash,” “Caviar & Pumpkin Seed,” “Rainbow Trout & Pineapple,” “Malted Milk Bread,” “Pomelo Gold & Meringue,” and “Pumpkin Pie” land in the following stratum: great recipes that achieved a truly memorable degree of pleasure. I would love to encounter any of these again.

Next come the “Amazake,” ”Toasted Corn & Black Truffle,” “Smoked Eel & Sesame Donut,” “Maine Uni Parfait,” “Maine Lobster & Uni,” “Avocado & Turnip,” “Venison Royale,” “Cadbury™ Quail Egg,” and “Yogurt Mousse & Quail”—good—even very good—preparations I would always be happy to sample again (but that just failed to elicit an extra degree of emotion).

Finally, there’s the “Trout Tail Tartare,” “Black Walnut Cured Quail Egg,” “Quail,” “Venison Bouillon,” and “Bittersweet Chocolate & Maitake”—merely good (or maybe just intriguing) items that fell short when it came to texture and/or flavor. That said, the underlying ideas shaping these dishes were sound, and they could easily be improved with a little more fine-tuning.

Overall, this makes for hit-rate of 78%—if one chooses to label those latter dishes (which were strange but not totally unappealing) failures—with some 39% of offerings landing in that “would love to have again” category or higher. The present numbers represent a clear increase from those I reported in October (76% and 33% respectively), as well as ones that more or less accord with an average meal at restaurants like Kyōten and Oriole that form Smyth’s (at least when it comes to the prices being charged) competition.

I say “an average meal” because Kyōten achieved a hit-rate of 94% (with 56% of items reaching that “best-of-the-year” standard) and Oriole achieved a hit-rate of 87% (with 60% of items reaching that “would love to have again” standard) back in November. Yes, these concepts (so much more narrowly focused on tailoring the finest luxury ingredients in a manner that yields total decadence) can routinely put up better numbers than what Smyth, for all its accolades, delivers. However, pursuing this train of thought (though certainly useful when guiding newcomers) ultimately cheapens gastronomy, for it ignores the wider context.

Kyōten and Oriole combine ingredients in a manner that is much more familiar and preserve their signature dishes as a means to ensure just about every guest will experience a high baseline of quality. This is why we love them, and, while I am always an advocate for more reinvention, why kill a golden goose when nobody else in Chicago seems capable of competing in the same niche?

I’ve come to feel that Smyth’s peer group is instead comprised of places like Cellar Door Provisions, Elske, and Feld: concepts that (though they do maintain one or two cherished recipes) largely surrender to the flux of seasons. These kitchens are even willing to suffer—and make their guests suffer—in their resolution to be shaped by nature (rather than exerting dominion over it). But, by relinquishing control and committing fully to a process (rather than chasing results), these teams frequently deliver a kind of pleasure that is totally unfamiliar, unexpected, and altogether more meaningful than the best tuna nigiri or truffle pasta. It’s no coincidence that these places can claim much more singular (and for some tastes better) wine programs too.

Smyth is undoubtedly the elder statesman of this little group, and, correspondingly, it draws on that status to push the envelope the furthest. Shields and Feltz and now Barker just weren’t ever going to let go of their obsessions for the sake of placating the occasional one-star review. When every day has been spent in joyful pursuit of undiscovered textures and flavors, you don’t just suddenly turn off the faucet—even if a menu spanning all of diners’ favorite dishes, from the time of the restaurant’s opening through the present day, would rank among the best ever served in Chicago. Most of the food, I think, will still seem ahead of its time too. Yet the Shieldses haven’t gotten here by ever looking backwards, and that is what has earned them a place alongside the world’s greatest chefs.

Looking back at tonight’s meal, I really must acknowledge how close it was to excellence. If the supporting flavors of the “Quail” were just a little less sweet, we’d be looking at a hit-rate of 83% from which only a few of the smaller, fleeting items diverged. Further, if dishes like the ”Toasted Corn & Black Truffle,” “Smoked Eel & Sesame Donut,” and “Maine Uni Parfait” delivered just a bit more pleasure (which I know they are fully capable of), the proportion of “would love to have again” items would have cleared 50%.

Certainly, diners don’t drop this kind of money for “almost.” Nonetheless, the point remains that Smyth largely succeeds—and sometimes even reaches the superlative heights of its less ambitious counterparts—despite challenging itself like no other kitchen does in this city. The polarization that sometimes results from this process is self-inflicted, yet it also cuts right to the heart of what continues to make this concept exciting.

The chefs are more willing than ever to take big swings, and they are still capable of exploring culinary hinterlands that confuse even the most experienced of their guests. Any new blood—any new head chef who’s introduced—will not be tasked with the preservation of what was. Their mind and tongue will form a new instrument: one granted absolute power to drive ingredients and practices and obsessions in an entirely new direction.

The foundation they will be building on, however ephemeral (or at times uneven), forms exactly the reason to get excited. Nothing is sacred here. Change is inevitable. And, when that entropy (and Smyth’s larger philosophy) is channeled through a new perspective, it will almost be as if Chicago has been blessed with an entirely new three-Michelin-star restaurant overnight.

Until then, the team shows no sign of slowing down as they reach the end of what has been a wildly successful era. Quite the opposite: they are continuing to put out recipes, crafted in their inimitable style, that rank among the finest expressions of their chosen ingredients.